-- This monograph is a prelude to the start of the Bhāratiya National Water Mission to ensure 24x7 water to every farm and every home.

-- The monograph recollects the tradition of sacredness of apām 'waters' as a divine gift, treasure and of Rāṣṭrram राष्ट्रं associated with the waters. The nation has over 8000 kms. of coastline and presently-available technologies can be harnessed to ensure that desalinated seawater reaches the tap of every home along the coastline. The nation is endowed with the Greatest Water Reservoir of the Globe, the Himalayan glaciers; these waters can reach every farm by sheer gravity flows. Flood waters of Brahmaputra can reach Kanyakumari by gravity flows.

-- निधि a place for deposits or storing up , a receptacle (esp. अपां निधि , र्° of waters , the ocean , sea , also N. of a सामन् MBh. Ka1v. &c (Monier-Williams)

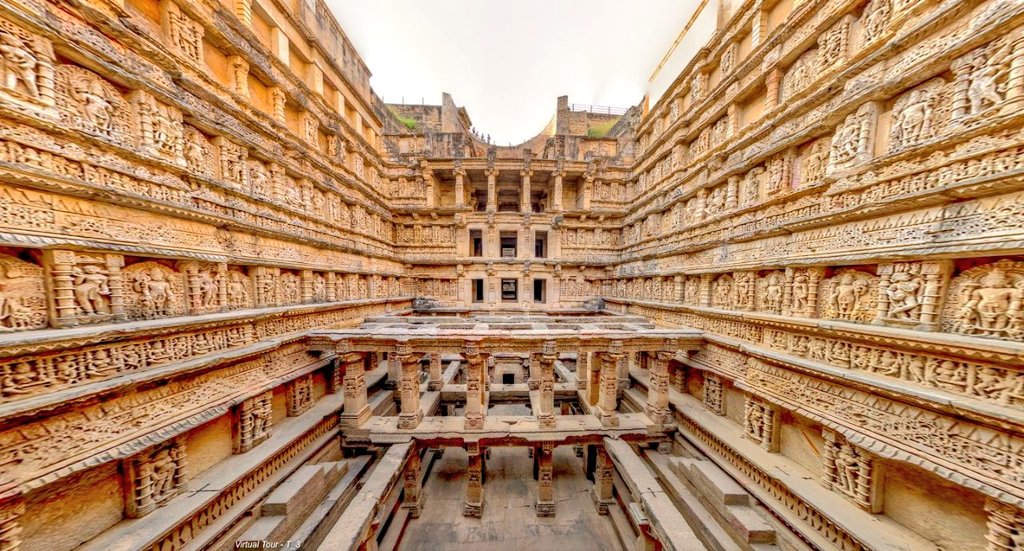

-- The breath-taking splendour of step wells of Bharat == vāpī, bāwlī, 'well with steps' -- are traceable to the reservoirs of Dholavira of Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization, from ca. 2500 BCE.

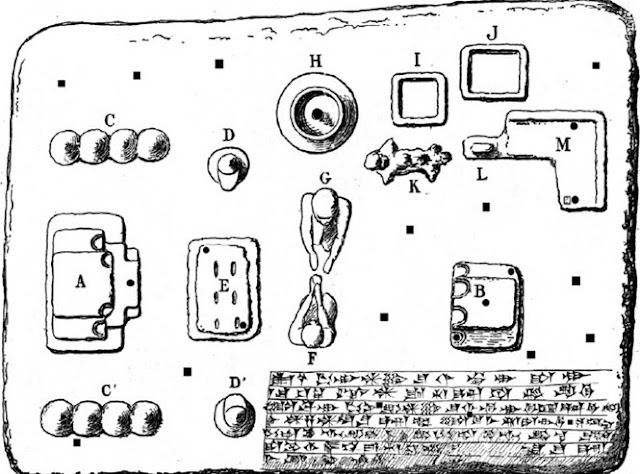

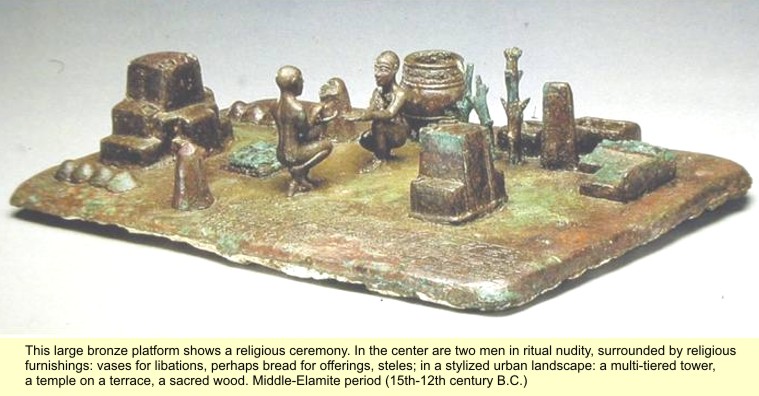

-- Sit Shamshi bronze, morning libations to Sun divinity, as Meluhha metalwork with Indus writing hieroglyphs transmitted along the Tin Road of Antiquity.https://tinyurl.com/y433q98k

Discovery location: Ninhursag or Nintud (Earth, Mountain and Mother Goddess)Temple, Acropole, Shūsh (Khuzestan, Iran); Repository: Musée du Louvre (Paris, France) ID: Sb 2743 width: 40 cm (15.75 inches); length: 60 cm (23.62 inches)

The stele (L) next to 3 stakes (or tree trunks, K) may denote a linga. Hieroglyph: numeral 3: kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy' PLUS meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻ post, forked stake ʼ.(Marathi)(CDIAL 10317) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) Thus, together, the three stakes or stalks + linga connote rebus representations of 'iron smithy' meḍ kolami. Another rebus reading may connote: mḗdha m. ʻ sacrificial oblation ʼ RV.Pa. mēdha -- m. ʻ sacrifice ʼ; Si. mehe, mē sb. ʻ eating ʼ mḗdhya -- ʻ full of vigour ʼ AV., ʻ fit for sacrifice ʼ Br. [mḗdha -- m. or mēdhāˊ -- f. ʻ mental vigour ʼ RV.] Pa. mejjha -- ʻ pure ʼ, Pk. mejjha -- , mijjha -- ; A. mezi ʻ a stack of straw for ceremonial burning ʼ.(CDIAL 10327). The semant. of 'pure' may also evoke the later-day reference to gangga sudhi 'purification of river water' in an inscription on Candi Sukuh 1.82m tall linga ligatured with a kris sword blade, flanked by sun and moon and a Javanese inscription referring to consecration and manliness as the metaphor for cosmic essence. The semant. link with Ahura Mazda is also instructive, denoting the evolution of the gestalt relating knowledge, consciousness and cosmic effulgence/energy. That the metaphor related to metalwork is valid is indicated by a Meluhha gloss: kole.l 'smithy' Rebus: kole.l 'temple.

A large stepped structure/altar/ziggurat (A) and small stepped structure/altar or temple (B) may be denoted by the gloss: kole.l. The large stepped structure (A) may be dagoba, lit. dhatu garbha 'womb of minerals' evoking the smelter which transmutes earth and stones into metal and yields alloyed metal castings with working in fire-altars of smithy/forge: kolami. It is imperative that the stupa in Mohenjo-daro should be re-investigated to determine the possibility of it being a ziggurat of the bronze age, comparable to the stepped ziggurat of Chogha Zambil (and NOT a later-day Bauddham caitya as surmised by the excavator, John Marshall).

Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy. Ka. kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë

blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go. (SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge.(DEDR 2133).

The pair of lingas (D and D') have indentations at the tip of the stone pillars. These indentations might have held lighted earthen lamps (deepam) to connote the lingas as pillars of light. The four hemi-spheres (C and C') linked to each stone pillar (D and D') have been explained as Meluhha hieroglyphs read rebus:

lo 'penis' Rebus: loh 'copper, metal'

Hieroglyphs: gaṇḍa 'swelling' gaṇḍa 'four' gaṇḍa 'sword' Hieroglyph: Ta. kaṇṭu ball of thread. ? To. koḍy string of cane. Ka. kaṇḍu, kaṇḍike, kaṇṭike ball of thread. Te. kaṇḍe, kaṇḍiya ball or roll of thread. (DEDR 1177)

Rebus: kanda 'fire-trench' used by metalcasters

Rebus: gaṇḍu 'manliness' (Kannada); 'bravery, strength' (Telugu)

Rebus: kāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’ (Marathi)

Together, hieroglyphs: lo + gaṇḍa. Rebus: लोखंड [ lōkhaṇḍa ] 'metalwork'

Metaphor: Sh. K.ḍoḍ. lō m. ʻ light, dawn ʼ; L. awāṇ. lō ʻ light ʼ; P. lo f. ʻ light, dawn, power of seeing, consideration ʼ; WPah. bhal. lo f. ʻ light (e.g. of moon) ʼ.(CDIAL 11120). + kaṇṭa 'manliness'.

Tabulation explaining the model & transcribed Elamite cuneiform inscription sourced from: Gian Pietro Basello, 2011, The 3D model from Susa called Sit-shamshi: an essay of interpretation, Rome, 2011 November 28-30 https://www.academia.edu/1706512/The_3D_Model_from_Susa_called_Sit-shamshi_An_essay_of_interpretation

The Sit Shamshi bronze model parallels the libations practised from ancient times by Hindus, Meluhha speakers who called themselves, bharatiyo 'metal casters' (Gujarati). The prayers are called sandhya vandanam which is perhaps the oldest practice among world religions. [quote]Sandhyavandanam consists of excerpts from the Vedas that are to be performed thrice daily at morning (prātaḥsaṃdhyā), at noon (mādhyānika), and in the evening (sāyaṃsaṃdhyā)...Sandhyavandanam literally means salutation to Sandhya. Sandhya literally means transition moments of the day namely the twotwilights : dawn and dusk and the solar noon. Thus Sandhyavandanam means salutation to twilight or solar noon. The term saṃdhyā is also used by itself in the sense of "daily practice" to refer to the performance of these devotions at the opening and closing of the day. For saṃdhyā as juncture of the two divisions of the day (morning and evening) and also defined as "the religious acts performed by Brahmans and twice-born men at the above three divisions of the day" see Monier-Williams, p. 1145, middle column.[unquote]

Mohenjo-daro stupa mound signifies a ziggurat temple and co-existed with the early phases of the civilization at the archaeological site.

Stepwells of the world are evidences of the spread of Sarasvati civilization culture of veneration of water as sacred. This monograph presents evidences of over 2200 stepwells of regions from AFE to ANE -- areas with which the artisans/seafaring Meluhha merchants of the civilization had cultural contacts. Sign 244 of Indus Script may signify a temple pond with steps.

I suggest that Sarasvati Civilization heritage of a unique water management system continues as stepwells in many parts of the world which has been influenced by the Meluhha artisans/seafaring merchants of the civilization who created the 'Great Bath' of Mohenjo-daro, ca. 2500 BCE.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Bath,_Mohenjo-daro#/media/File:Mohenjo-daro.jpg The puṣkariṇī, 'water tank' is in front of the temple, the ziggurat of Mohenjo-daro. It ain't a Bauddham stupa, but a ziggurat structure which was coterminum with the Great bath and other structures of the city. The 'stupa'mound compares structurally with the Ur ziggurat dated to 21st cent.BCE.

Dholavira. Water tank with steps See: http://vigyanprasar.gov.in/isw/harappans_knowledge_hydraulic_engineering_dholavira_reveals_story.htm

kuṇḍá1 n. (RV. in cmpd.) ʻ bowl, waterpot ʼ KātyŚr., ʻ basin of water, pit ʼ MBh. (semant. cf. kumbhá -- 1 ), ˚ḍaka -- m.n. ʻ pot ʼ Kathās., ˚ḍī -- f. Pāṇ., ˚ḍikā -- f. Up. 2. *gōṇḍa -- . [← Drav., e.g. Tam. kuṭam, Kan. guṇḍi, EWA i 226 with other ʻ pot ʼ words s.v. kuṭa -- 1 ]1. Pa. kuṇḍi -- , ˚ḍikā -- f. ʻ pot ʼ; Pk. kuṁḍa -- , koṁ˚ n. ʻ pot, pool ʼ, kuṁḍī -- , ˚ḍiyā -- f. ʻ pot ʼ; Kt. kuṇi ʻ pot ʼ, Wg. kuṇḍäˊi; Pr. künǰǘ ʻ water jar ʼ; Paš. weg. kuṛã̄ ʻ clay pot ʼ < *kũṛā IIFL iii 3, 98 (or poss. < kuṭa -- 1 ), lauṛ. kuṇḍalīˊ ʻ bucket ʼ; Gaw. kuṇḍuṛīˊ ʻ milk bowl, bucket ʼ; Kal. kuṇḍṓk ʻ wooden milk bowl ʼ; Kho. kúṇḍuk, ˚ug ʻ milk bowl ʼ, (Lor.) ʻ a kind of platter ʼ; Bshk. kūnḗċ ʻ jar ʼ (+?); K. kŏnḍ m. ʻ metal or earthenware vessel, deep still spring ʼ, kọ̆nḍu m. ʻ large cooking pot ʼ, kunāla m. ʻ earthenware vessel with wide top and narrow base ʼ; S. kunu m. ʻ whirlpool ʼ, ˚no m. ʻ earthen churning pot ʼ, ˚nī f. ʻ earthen cooking pot ʼ, ˚niṛo m.; L. kunnã̄ m. ʻ tub, well ʼ, ˚nī f. ʻ wide -- mouthed earthen cooking pot ʼ, kunāl m. ʻ large shallow earthen vessel ʼ; P. kū̃ḍā m. ʻ cooking pot ʼ (← .), kunāl, ˚lā m., ˚lī f., kuṇḍālā m. ʻ dish ʼ; WPah. cam. kuṇḍ ʻ pool ʼ, bhal. kunnu n. ʻ cistern for washing clothes in ʼ; Ku. kuno ʻ cooking pot ʼ, kuni, ˚nelo ʻ copper vessel ʼ; B. kũṛ ʻ small morass, low plot of riceland ʼ, kũṛi ʻ earthen pot, pipe -- bowl ʼ; Or. kuṇḍa ʻ earthen vessel ʼ, ˚ḍā ʻ large do. ʼ, ˚ḍi ʻ stone pot ʼ; Bi. kū̃ṛ ʻ iron or earthen vessel, cavity in sugar mill ʼ, kū̃ṛā ʻ earthen vessel for grain ʼ; Mth. kũṛ ʻ pot ʼ, kū̃ṛā ʻ churn ʼ; Bhoj. kũṛī ʻ vessel to draw water in ʼ; H. kū̃ḍ f. ʻ tub ʼ, kū̃ṛā m. ʻ small tub ʼ, kū̃ḍā m. ʻ earthen vessel to knead bread in ʼ, kū̃ṛī f. ʻ stone cup ʼ; G. kũḍ m. ʻ basin ʼ, kũḍī f. ʻ water jar ʼ; M. kũḍ n. ʻ pool, well ʼ, kũḍā m. ʻ large openmouthed jar ʼ, ˚ḍī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; Si. ken̆ḍiya, keḍ˚ ʻ pot, drinking vessel ʼ.2. N. gũṛ ʻ nest ʼ (or ← Drav. Kan. gūḍu ʻ nest ʼ, &c.: see kulāˊya -- ); H. gõṛā m. ʻ reservoir used in irrigation ʼ.*gōkuṇḍikā -- , taílakuṇḍa -- , *madhukuṇḍikā -- , *rakṣākuṇḍaka -- ; -- kuṇḍa -- 2 ?Addenda: kuṇḍa -- 1 : S.kcch. kūṇḍho m. ʻ flower -- pot ʼ, kūnnī f. ʻ small earthen pot ʼ; WPah.kṭg. kv́ṇḍh m. ʻ pit or vessel used for an oblation with fire into which barley etc. is thrown ʼ; J. kũḍ m. ʻ pool, deep hole in a stream ʼ; Brj. kū̃ṛo m., ˚ṛī f. ʻ pot ʼ.(CDIAL 3264)

vāpīˊ f. ʻ pond, tank ʼ Mn. [√vap 2 ]Pa. vāpi -- f. ʻ pond ʼ, Pk. vāvī -- f.; S. vāĭ̄ f. ʻ well ʼ; P. vã̄, bã̄ f. ʻ reservoir with steps down to water ʼ; WPah.roh. bae, bā f. ʻ pond, spring ʼ, kc. bau f. ʻ spring ʼ; H. bāwī, bāī˜ f. ʻ large well ʼ; G. vāv f. ʻ large well with steps ʼ; OSi. (Brāhmī) vapi, vavi, (6th cent.) veva, (10th cent.) ãdotdot; Si. väv -- a ʻ pond ʼ, Md. veu; -- ext. -- ḍ -- : H. bāuṛī f. ʻ well with steps ʼ (→ M. bāvḍī f.), G. vāvṛī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; <-> with -- l -- : Ku. bāwalī f. ʻ covered well, reservoir ʼ; Bi. bāwlī ʻ large well ʼ, OAw. bāvarī, H. bāulī, bāurī f.Addenda: vāpīˊ -- : WPah.kṭg. bā f. (obl. -- i ), bai f. ʻ tank, stonebuilt reservoir fed by a spring, spring ʼ, kc. bau f. (obl. babi), bauṛe f., poet. be e f.; Md. veu veyo, vevu, vevek ʻ tank ʼ.(CDIAL 11529)

Kalyani(Temple tank) at Hulikere near Halebidu(Karnataka) Dated: ~12th century CE

Kalyani(Temple tank) at Hulikere near Halebidu(Karnataka) Dated: ~12th century CE - Chand Baori stepwell, Abhaneri ,Rajasthan Dated: ~9th Century CE The four sided 13 storied stepwell is over 100feet deep and lined with over 3500steps with an amazing geometrical precision. This stepwell is one of the largest stepwells, a magnificent device to store water.

![]()

- A large stepwell and temples, Bundi(Rajasthan) Anda(dome) surmounted by Kalasha forms the Shikhara of temple. It is known as Dabhai Kund. Currently filled with dogshit and garbage. It is maintained by ASI.etweet

![]()

- Aqueducts of SahasraLinga Talao, Gujrat Dated: ~11th century CE It was functional till some point in 17th century CE. Mesmerizing combination of art and hydrolic engineering!

![]()

- Towards the western end there is a rudra kupa in which water from the river Saraswati was collected and then allowed to pass into the inlet channel of the Sahastralinga Tank. This cistern is about forty meters in diameter.

![]()

- Remains of pavilion and aqueducts, SahasraLinga Talao Near the middle of the eastern embankment are the remains of the old Siva temple, comprising the basements of the pavilions together with a colonnade of forty eight pillars; it was in good condition till 16th century.

![]()

- Stepped pond of Sun temple, Modhera Dated: ~11th century CE This huge pond measures 53.6*36.6m². This pond is geometrically more complex for it utilized fractal pattern. Note ornately carved Shikhara. Imagine the beauty of sight with exquisite temples reflected in Kunda!

![Image result for step well india]()

![]()

- Perspective! Surya Kunda, Sun Temple, Modhera(Gujrat) Dated: ~11th century CE Just note the scale of construction! Tropic of cancer pass through this temple complex.

![]()

- One more from same SuryaKunda, Sun Temple, Modhera(Gujrat) Dated: ~11th century CE Note the scale of construction! This temple is result of perfection in geometry and astronomy. Sun rays illuminate the sanctum on the days of equinoxes.

![]()

- Kalyani(Temple pond) of ancient BhogaNandishwara Temple, Nandi Hills, Karnataka Note amazing symmetry! Cloister lined with elaborate Makara Arch niche runs around this Kalyani. History of stepped ponds can be traced back to Sindhu-Saraswati valley civilization.

![]()

- Raniji ki Baodi(Queen's Stepwell), Bundi Dated: 17th century CE The stepwell also served as temple for miniature shrines are carved depicting Dashavatara and Trimurti. The stepwell is almost 46m in length. Torana(s)are exquisitely carved. Bundi is home to more than 387 stepwells.

![Image result for step well india]()

![Image result for step well india]()

![Image result for step well india]()

![]()

- Swastika well, also known as Marpidugu Perunkinaru, was dug by King Kamban Araiyan. One inscription found in this well is in poetical form and describe the immortal life of man. ~8th century CE. It is located behind the Pundarikakshan Perumal Temple in Thiruvellarai(Tamilnadu).

![]()

- A magnificent old stepwell from Dholpur(Rajasthan) Stepwell is probably 3tierred and lined with magnificent corridors. Unfortunately, it is filled with garbage and not maintained. Govt. should wake up and restore all these historical stepwells. See more: https://youtu.be/jDjEmZbiSTA

![]()

- Correction, I'm told that this huge stepwell is actually 7 storeyed. Here is clipping published in some local news paper telling about its sorry state. This stepwell is an engineering marvel adorned with exquisite 'Torana'(arches). Sent by: Jitendra Sharma

![]()

- Kund(stepped pond) at RamNagar fort, Varanasi. People of all class can be seen here. Elaborate corridors surrounds the pond in a similar manner as we see in temple ponds of South Indian Temples. As seen by Thomas Daniell in 1790s

![]()

- Spectacular view of Vidyadhar Stepwell, Baroda Note Kirtimukha, bell&chain and lotus pattern. In construction this stepwell is similar to other Gujrati Stepwell like Adalaj, Dada Harir Vav etc.

![]()

- Similar structure is there at Amriteshwar Temple, Ratanwadi, Nagar district, Maharashtra 422604

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-855153046-5c6b810ec9e77c000119fbff.jpg)

Panna Meena Ka Kund step well, (baori), Amer (near Jaipur)

India's Forgotten Stepwells

- 00:00 - 28 June, 2013

- by Victoria Lautman

Agrasen ki Baoli, Delhi. Image © Victoria S. Lautman It’s hard to imagine an entire category of architecture slipping off history’s grid, and yet that seems to be the case with India’s incomparable stepwells. Never heard of ‘em? Don’t fret, you’re not alone: millions of tourists – and any number of locals - lured to the subcontinent’s palaces, forts, tombs, and temples are oblivious to these centuries-old water-structures that can even be found hiding-in-plain-sight close to thronged destinations like Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi or Agra’s Taj Mahal. Learn more about these stepwells' curious histories, after the break...

.jpg?1372284136)

Rudimentary stepwells first appeared in India between the 2nd and 4th centuries A.D., born of necessity in a capricious climate zone bone-dry for much of the year followed by torrential monsoon rains for many weeks. It was essential to guarantee a year-round water-supply for drinking, bathing, irrigation and washing, particularly in the arid states of Gujarat (where they’re called vavs) and Rajasthan (where they’re baoli, baori, or bawdi) where the water table could be inconveniently buried ten-stories or more underground. Over the centuries, stepwell construction evolved so that by the 11th century they were astoundingly complex feats of engineering, architecture, and art.

.jpg?1372284455)

Construction of stepwells involved not just the sinking of a typical deep cylinder from which water could be hauled, but the careful placement of an adjacent, stone-lined “trench” that, once a long staircase and side ledges were embedded, allowed access to the ever-fluctuating water level which flowed through an opening in the well cylinder. In dry seasons, every step – which could number over a hundred - had to be negotiated to reach the bottom story. But during rainy seasons, a parallel function kicked in and the trench transformed into a large cistern, filling to capacity and submerging the steps sometimes to the surface. This ingenious system for water preservation continued for a millennium.

.jpg?1372284007)

In many wells – particularly those in Gujarat – covered “pavilions” punctuated each successive level, accessed by narrow ledges as the water level rose, and providing vital shade while also buttressing walls against the intense pressure. For this same reason, most stepwells gradually narrow from the surface to the lowest tier underground, where the temperature is refreshingly cool. By building down into the earth rather than the expected “up”, a sort of reverse architecture was created and, since many stepwells have little presence above the surface other than a low masonry wall, a sudden encounter with one of these vertiginous, man-made chasms generates both a sense of utter surprise and total dislocation. Once inside, the telescoping views, towering pavilions, and the powerful play of light and shadow are equally disorienting, while also making them devilishly difficult to photograph.

.jpg?1372284388)

.jpg?1372341296)

.jpg?1372284281)

By the 19th-century, several thousand stepwells in varying degrees of grandeur are estimated to have been built throughout India, in cities, villages, and eventually also in private gardens where they’re known as “retreat wells”. But stepwells also proliferated along crucial, remote trade routes where travelers and pilgrims could park their animals and take shelter in covered arcades. They were the ultimate public monuments, available to both genders, every religion, seemingly anyone at all but for the lowest-caste Hindu. It was considered extremely meritorious to commission a stepwell, an earthbound bastion against Eternity, and it’s believed that a quarter of these wealthy or powerful philanthropists were female. Considering that fetching water was (and is still) assigned to women, the stepwells would have provided a reprieve in otherwise regimented lives, and gathering down in the village vav was surely an important social activity.

.jpg?1372284183)

Stepwells fall into similar categories based on their scale, layout, materials, and shape: they can be rectangular, circular, or even L-shaped, can be built from masonry, rubble or brick, and have as many as four separate entrances. But no two are identical and - whether simple and utilitarian, or complex and ornamented - each has a unique character. Much depends on where, when, and by whom they were commissioned, with Hindu structures functioning as bona-fide subterranean temples, replete with carved images of the male and female deities to whom the stepwells were dedicated. These sculptures formed a spiritual backdrop for ritual bathing, prayers and offerings that played an important role in many Hindu stepwells and despite a lack of accessible ground water, a number continue today as active temples, for instance the 11th-century Mata Bhavani vav in Ahmedabad.

.jpg?1372284049)

.jpg?1372284091)

.jpg?1372284052)

Nowhere was a more elaborate backdrop for worship planned than at India’s best-known stepwell, the Rani ki vav (Queen’s Well) two hours away in Patan. Commissioned by Queen Udayamati around 1060 A.D. to commemorate her deceased spouse, the enormous scale – 210 feet long by 65 wide – probably contributed to disastrous flooding that buried the vav for nearly a thousand years under sand and mud close to its completion. The builders realized they were attempting something risky, adding extra buttressing and massive support walls, but to no avail. In the 1980’s, the excavation and restoration of Rani ki vav (which is hoped to achieve UNESCO World Heritage status soon) were completed but by then, long-exposed columns on the first tier had been hauled off to build the nearby 18th-century Bahadur Singh ki vav, now completely encroached by homes.

.jpg?1372284385)

.jpg?1372284439)

.jpg?1372283729)

.jpg?1372283735)

.jpg?1372283775)

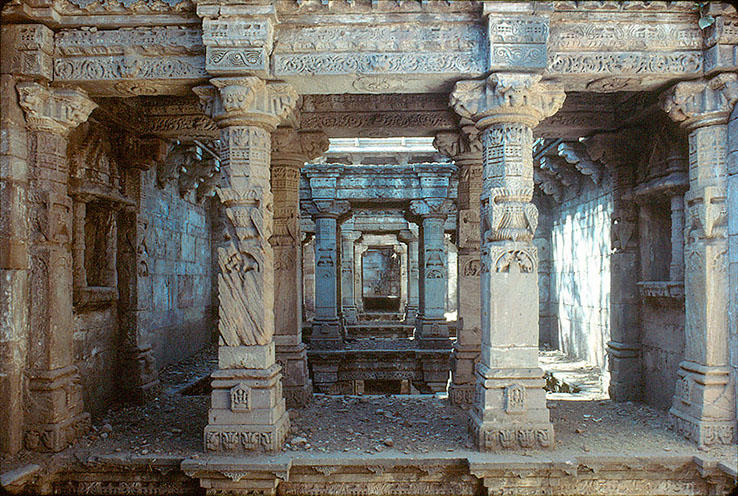

Once Muslim rulers began to dominate in India (dates differ depending on the area) stepwells shifted in their design both structurally and decoratively. Hindu builders used trabeate (or post and lintel) construction with corbel domes, Muslims introduced the arch and “true” dome. Hindu artists carved sculptures and friezes packed with deities, humans, and animals while Islam forbade depictions of any creatures at all. But when, for a brief period in Gujarat, the two traditions collided around 1500 A.D. a pair of brilliant offspring resulted close to the new capital of Ahmedabad, and worth a detour for anyone visiting the modernist masterworks of Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn, or B.V. Doshi.

.jpg?1372283609)

Both the Rudabai and Dada Harir vavs are five stories deep with octagonal subterranean pools, each commissioned by a female patroness and, although Rudabai boasts three separate entrances (a rarity), it and Dada Harir vav are conceptual cousins, built at virtually the same moment just twelve miles from one another, commissioned under Islamic authority using Hindu artisans. Each is elaborately decorated, but with a notable absence of deities and human figures, but compared to other, more somber Islamic-commissioned stepwells, these two are positively flamboyant.

.jpg?1372283611)

.jpg?1372283874)

As for the current state of stepwells, a hand-full are in relatively decent condition, particularly those few where tourists might materialize. But for most, the prevailing condition is simply deplorable due to a host of reasons. For one, under the British Raj, stepwells were deemed unhygienic breeding grounds for disease and parasites and were consequently barricaded, filled in, or otherwise destroyed. “Modern” substitutes like village taps, plumbing, and water tanks also eliminated the physical need for stepwells, if not the social and spiritual aspects. As obsolescence set in, stepwells were ignored by their communities, became garbage dumps and latrines, while others were repurposed as storage areas, mined for their stone, or just left to decay.

.jpg?1372283917)

.jpg?1372284093)

.jpg?1372284240)

.jpg?1372341437)

Depleted water-tables from unregulated pumping have caused many of the wells to dry up, and when water is present, it’s generally afloat with garbage or grown over with plant-life from lack of attention, even in currently-active temple wells.

.jpg?1372283965)

.jpg?1372283933)

.jpg?1372284014)

.jpg?1372284177)

Stagnant water is the least of it: anyone with phobias for snakes, bats, bugs, heights, depths, darkness or filth will find many stepwells challenging. The unusual, 16th-century Bhamaria retreat well near Mehmedabad houses a colony of extremely vocal bats; the extraordinary 13th-century Vikia vav on a former caravan route near Ghumli is on the verge of total collapse. Stairs are unstable and treacherous. The list goes on.

.jpg?1372283838)

.jpg?1372284540)

Do these unique edifices have a future? Grim as it may seem, the growing urgency for water conservation has spearheaded a few recent efforts to de-silt and “reactivate” a few wells in Delhi and Gujarat in the hopes that they might once again collect and store water. Meanwhile, a number of contemporary architects have taken inspiration from vavs and baolis (along with other stepped water-structures like ponds,kunds, and tanks that are frequently mistaken for stepwells) which may help ignite more interest in – and appreciation for – these disappearing marvels.

.jpg?1372283975)

Certainly, more books, studies, and articles are needed to help spread the word and anyone interested in further reading can look for these four invaluable tomes: Jutta Jain-Neubauer’s seminal (but out-of-print) The Stepwells of Gujarat In Art-Historical Perspective from 1981; Julia Hegewald’s costly but essential Water Architecture in South Asia of 2002; Morna Livingston’s gorgeous and informative Steps to Water, also from 2002; and Kirit Mankodi’s The Queen’s Stepwell at Patan (out of print) from 1991. But most important, gather your friends, get on a plane, and go see them for yourself before they dissapear for all time.

Victoria S. Lautman is a freelance print and broadcast journalist specializing in architecture, art, and design. She holds an MA in art history, a BA in archeology, and during frequent travels throughout

https://www.archdaily.com/395363/india-s-forgotten-stepwells

Stepwell in front of Khedamata temple at Modi village. (Source: India Water Portal)

Jodhpur stepwell.

Stepwell #5, Nagar Kund Baori, Bundi, Rajasthan

.jpg?1372283874)

Dada Harir Vav, Ahmedabad

Abaneri

Neemrna Bawdi. Rajasthan.

Agrasen ki Bawdi. New Delhi.

Nagar Sagar Kund. Bundi. Rajasthan.

The Islamic Stepwells of Gujarat, India April 13, 2011 by Samir S. Patel

India's Underground Water Temples Archaeology, Volume 64 Number 3, May/June 2011 by Samir S. Patel

The stepwells of Gujarat are spiritual monuments to water and stark reminders of the increasing scarcity of this critical resource

http://www.archaeology.org/1105/features/images/india_gujarat_stepwells_ran_ki_vav.gif

Rani Ki Vav (Queen’s Stepwell), Patan, Gujarat

Rudabai's Vav, Adalaj, Gujarat

Dada Hari Vav, Ahmedabad, Gujarat

(Samir S. Patel)

Slideshow: The Islamic Stepwells of Gujarat, India

The stepwells of the state of Gujarat, India, are part of an architectural tradition that goes back over 1,000 years. The most grandly ornamented stepwells (known as baolis or vavs), including Rani Ki Vav ("India's Underground Water Temples," May/June 2011), were built in the eleventh century. Construction of them continued, even as control over the area shifted from Hindu dynasties to Muslim kingdoms. The form of the stepwell—a grand staircase leading to the bottom of a well cylinder, with ornamented colonnades and terraces on each level—remained the same, as did its function as a water source, cool gathering place, and site for rituals. In these later wells, Hindu statuary was replaced with geometric and floral flourishes and inscriptions characteristic of Islamic architecture. Rudabai's Vav, built in 1499, is now part of a public park in the quiet town of Adalaj, 11 miles north of the traditional Muslim capital at Ahmedabad. Dada Hari Vav was constructed just two years later and lies deep within Ahmedabad's old city. Both still serve as places to socialize, but neither regularly contains water—the water table in Gujarat has long since been drawn down to critically low levels.

Descend into any of Gujarat’s stepwells, and the first thing you might notice is the temperature change—though they are bone dry, it’s nonetheless like stepping into a pool of cool water. The second sensation is disorientation. They are marvels of proportion and symmetry, but they’re also recursive, Escher-esque, and vertiginous. The final impression, as you look up, down, and through the stepwell, is surprise that something as mundane as a well can be both monumental and intimate.

The stepwells of the western Indian state of Gujarat, known as vavs in Gujarati and baoris in Hindi, are part of an architectural tradition that goes back more than a thousand years. The typical vav consists of a long, straight staircase that leads to the bottom of a circular or octagonal well shaft, with landings and colonnades on each story along the way. The design is both a clever solution to the region’s boom-and-bust monsoon cycle and a place of social and spiritual significance. In a more typical well, a vessel is lowered by a rope to gather water, but in stepwells people could walk to the water level—near the top just after the monsoon, and six or more stories down just before it—to collect water, bathe, and socialize.

Stepwell, Hampi (Karnataka)

Stepwell, Hampi (Karnataka)

Stepwell, Nahargarh fort (Rajasthan)

Stepwell, Nahargarh fort (Rajasthan) Stepwell in Byblos, Lebanon, like the ones seen in India.

Stepwell in Byblos, Lebanon, like the ones seen in India."Rudimentary stepwells first appeared in India between the 2nd and 4th centuries A.D., born of necessity in a capricious climate zone bone-dry for much of the year followed by torrential monsoon rains for many weeks. It was essential to guarantee a year-round water-supply for drinking, bathing, irrigation and washing, particularly in the arid states of Gujarat (where they’re called vavs) and Rajasthan (where they’re baoli, baori, or bawdi) where the water table could be inconveniently buried ten-stories or more underground. Over the centuries, stepwell construction evolved so that by the 11th century they were astoundingly complex feats of engineering, architecture, and art." Most Stepwells are located in north and west India, whilst some stepwells have achieved broad visibility (such as the UNESCO World Heritage listed Rani ki Vav in Patan, Gujarat), many stepwells are sadly neglected and under threat of encroachment, damage or even complete collapse. |

Stepwell Atlas aims to be a community-driven resource to accurate map and collate information on stepwells, and through this to raise their profile and visibility and safeguard their future.

Please support Stepwell Atlas by registering on the site, and adding new stepwells, photos, links, information and accurate locations.

Stepwell Atlas is a forum where users can share news and information about stepwells and notable stepped water architecture, for cultural purpose. The managers of the website endeavour to address any reported mistakes or concerns in a timely manner: please contact

However the managers have no responsability or liability for the accuracy of for consequences of using any information that appears on the website.

We are keen to receive any

The site manager, Philip Earis http://stepwells.org/atlas.php?cmbm=1

Rani ki Vav(stepwell/temple), Gujrat Dated: ~11th century CE This magnificent subterranean monument was silted until its excavation in late 80s. This marvellous east facing step well measures approximately 64*20*30m³.

Stepped pond of Sun temple, Modhera Dated: ~11th century CE This huge pond measures 53.6*36.6m². This pond is geometrically more complex for it utilized fractal pattern. Note ornately carved Shikhara. Imagine the beauty of sight with exquisite temples reflected in Kunda!

Agrasen Ki Baoli, Delhi

Agrasen Ki Baoli, Delhi Adalaj Ni Wav, Adalaj

Adalaj Ni Wav, Adalaj Dada Harir Ni Wav, Ahmedabad

Dada Harir Ni Wav, Ahmedabad Bhamaria Wav, Mehmedabad

Bhamaria Wav, Mehmedabad Mata Bhawani Wav, Patan

Mata Bhawani Wav, Patan Mertani Baori, Jhunjhunu

Mertani Baori, Jhunjhunu Madhav Wav, Vadhwan, Kathiawar

Madhav Wav, Vadhwan, Kathiawar Ganga Wav, Brindavan

Ganga Wav, Brindavan Gandhak ki Baoli, Delhi

Gandhak ki Baoli, Delhi.jpg?1372283917) Baoli, Fatehpur

Baoli, Fatehpur Bahadur Singh ki Wav, Patan

Bahadur Singh ki Wav, Patan Mukundpura Baoli, Narnaul

Mukundpura Baoli, Narnaul.jpg?1372341437) Takht Baoli, Narnaul

Takht Baoli, Narnaul Neemrana Baoli, Rajasthan

Neemrana Baoli, Rajasthan.jpg?1372284540) Vikia Wav, Ghumli

Vikia Wav, GhumliStepwells are wells or ponds in which the water is reached by descending a set of steps. They may be multi-storied with a bullock turning a water wheel to raise the well water to the first or second floor. They are most common in western India and are also found in the other more arid regions of the Indian subcontinent, extending into Pakistan. The construction of stepwells is mainly utilitarian, though they may include embellishments of architectural significance, and be temple tanks.

Stepwells are examples of the many types of storage and irrigation tanks that were developed in India, mainly to cope with seasonal fluctuations in water availability. A basic difference between stepwells on the one hand, and tanks and wells on the other, is to make it easier for people to reach the ground water and to maintain and manage the well.

The builders dug deep trenches into the earth for dependable, year-round groundwater. They lined the walls of these trenches with blocks of stone, without mortar, and created stairs leading down to the water.[1] The majority of surviving stepwells originally served a leisure purpose as well as providing water. This was because the base of the well provided relief from daytime heat, and this was increased if the well was covered. Stepwells also served as a place for social gatherings and religious ceremonies. Usually, women were more associated with these wells because they were the ones who collected the water. Also, it was they who prayed and offered gifts to the goddess of the well for her blessings.[1] This led to the building of some significant ornamental and architectural features, often associated with dwellings and in urban areas. It also ensured their survival as monuments.

Stepwells usually consist of two parts: a vertical shaft from which water is drawn and the surrounding inclined subterranean passageways, chambers and steps which provide access to the well. The galleries and chambers surrounding these wells were often carved profusely with elaborate detail and became cool, quiet retreats during the hot summers.[2]

Names

A number of distinct names, sometimes local, exist for stepwells. In Hindi-speaking regions, they include names based on baudi (including bawdi (Rajasthani: बावड़ी), bawri, baoli, bavadi, and bavdi). In Gujarati and Marwari language, they are usually called vav or vaav (Gujarati: વાવ). Other names include kalyani or pushkarani (Kannada), baoli (Hindi: बावली) and barav (Marathi: बारव).

History

See also: History of stepwells in Gujarat

The 18th-century Baoli Ghaus Ali Shah, in Farrukhnagar, Haryana

Agrasen Ki Baoli in New Delhi

The stepwell may have originated to ensure water during periods of drought. Steps to reach the water level in artificially constructed reservoirs can be found in the sites of Indus Valley Civilization such as Dholavira and Mohenjo-daro.[3] Mohenjo-daro has cylindrical brick lined wellswhich may be the predecessors of the stepwell.[4] The first rock-cut stepwells in India date from 200-400 AD.[5]

The earliest example of a bath-like pond reached by steps is found at Uperkot caves in Junagadh. These caves are dated to the 4th century. Navghan Kuvo, a well with circular staircase in the vicinity, is another example. It was possibly built in Western Satrap (200-400 AD) or Maitraka (600-700 AD) period, though some place it as late as the 11th century. The nearby Adi Kadi ni Vav was constructed either in the second half of the 10th century or the 15th century.[6]

The stepwells at Dhank in Rajkot district are dated to 550-625 AD. The stepped ponds at Bhinmal (850-950 AD) are followed by it.[5] The stepwells were constructed in the south western region of Gujarat around 600 AD; from there they spread north to Rajasthan and subsequently to north and west India. Initially used as an art form by Hindus, the construction of these stepwells hit its peak during Muslim rule from the 11th to 16th century.[2]

One of the earliest existing example of stepwells was built in the 11th century in Gujarat, the Mata Bhavani's Stepwell. A long flight of steps leads to the water below a sequence of multi-story open pavilions positioned along the east/west axis. The elaborate ornamentation of the columns, brackets and beams are a prime example of how stepwells were used as a form of art.[7]

The Mughal rulers did not disrupt the culture that was practiced in these stepwells and encouraged the building of stepwells. The authorities during the British Raj found the hygiene of the stepwells less than desirable and installed pipe and pump systems to replace their purpose.[7]

Significance

The stepwell ensures the availability of water during periods of drought. The stepwells had social, cultural and religious significance.[7] These stepwells were proven to be well-built sturdy structures, after withstanding earthquakes.[1]

Details

Many stepwells have ornamentation and details as elaborate as those of Hindu temples. Proportions in relationship to the human body were used in their design, as they were in many other structures in Indian architecture.[8]

In India

A number of surviving stepwells can be found across India, including in North Karnataka (Karnataka), Gujarat, Rajasthan, Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra. In 2016 a collaborative mapping project, Stepwell Atlas,[9] started to map GPS coordinates and collate information on stepwells. Over 2000 stepwells have so far been mapped.

Significant stepwells include:

The Rani ki vav, Patan, Gujarat

Rudabai stepwell, Adalaj

Toor Ji Ki Bawari, stepped well, Jodhpur

Stepped well, Hampi

Stepwells in Indonesia

· Rajon ki baoli, New Delhi

· ![]() Chand Baori in Abhaneri near Jaipur, Rajasthan Chand Baori, in the village of Abhaneri near Bandikui, Rajasthan

Chand Baori in Abhaneri near Jaipur, Rajasthan Chand Baori, in the village of Abhaneri near Bandikui, Rajasthan

Chand Baori in Abhaneri near Jaipur, Rajasthan Chand Baori, in the village of Abhaneri near Bandikui, Rajasthan

Chand Baori in Abhaneri near Jaipur, Rajasthan Chand Baori, in the village of Abhaneri near Bandikui, Rajasthan· Adalaj ni Vav at Adalaj, Gandhinagar, Gujarat

· Dada Harir Stepwell, Ahmedbad

· ![]() Birkha Bawari, Jodhpur

Birkha Bawari, Jodhpur

Birkha Bawari, Jodhpur

Birkha Bawari, Jodhpur· Raniji ki Baori in Bundi, Rajasthan; Bundi has over 60 baolis in and around the town.

View of a stepwell at Fatehpur, Shekhawati

View of a stepwell at Fatehpur, ShekhawatiIn Pakistan

Stepwells from Mughal periods still exist in Pakistan. Some are in preserved conditions while others are not.

· Rohtas Fort, near Jhelum

· Wan Bhachran, near Mianwali

· Losar Baoli, near Islamabad

· Losar Baoli, Sher Shah Park Wah Cantt

Stepped ponds

Shravanabelagola stepped pond, Karnataka

Stepped ponds are very similar to stepwells in terms of purpose but it is important to recognize the difference between these two types of structures. For example, stepped ponds were always built to accompany a nearby temple while stepwells were positioned away from noisy sites and future tourist attractions.[10] While stepwells are dark and barely visible from the surface, stepped ponds are illuminated by the light from the sun. Also, stepwells are quite linear in design compared to the rectangular shape of stepped ponds.[8]

Influence

Stepwells are certainly one of India's most unusual, but little-known, contributions to architecture. They influenced many other structures in Indian architecture, especially many that incorporate water into their design.[2] Ram Bagh in Agra was the first Mughal garden in India.[8] It was designed by the Mughal emperor Babur and reflected his notion of paradise not only through water and landscaping, but also through symmetry by including a reflecting pool in the design. Naturally, he was entranced by stepwells and felt that one would complement the garden of his palace. He built a baoli in Agra Fort. Many other Mughal gardens include reflecting pools to enhance the landscape or as an elegant entrance. Additional famous gardens that incorporate water into their design include:

· Mehtab Bagh, Agra

· Nishat Gardens, Jammu and Kashmir

Notes

1. Shekhawat, Abhilash. "Stepwells of Gujarat". India's Invitation. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

2. Davies, Philip (1989). The Penguin guide to the monuments of India. London: Viking. ISBN 0-14-008425-8.

3. Takezawa, Suichi. "Stepwells -Cosmology of Subterranean Architecture as seen in Adalaj" (pdf). The Diverse Architectural World of The Indian Sub-Continent. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

4. Livingston & Beach, page 19

5. Livingston & Beach, page xxiii

6. Jutta Jain-Neubauer (1981). The Stepwells of Gujarat: In Art-historical Perspective. Abhinav Publications. pp. 19–25. ISBN 978-0-391-02284-3.

7. Tadgell, Christopher (1990). The History of Architecture in India. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-2960-9.

8. Livingston, Morna (2002). Steps to Water: The Ancient Stepwells of India. New York: Princeton Architectural. ISBN 1-56898-324-7.

10. Jain-Neubauer, Jutta (1981). The Stepwells of Gujarat: In Art-historical Perspective. New Delhi: Abhinav. ISBN 0-391-02284-9.

References

· Rima Hooja: "Channeling Nature: Hydraulics, Traditional Knowledge Systems, And Water Resource Management in India – A Historical Perspective". At infinityfoundation.com

· Livingston, Morna & Beach, Milo (2002). Steps to Water: The Ancient Stepwells of India. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 1-56898-324-7.

· Jutta Jain Neubauer The Stepwells of Gujarat: An Art-historical Perspective (2001)

· Philip Davies, The Penguin guide to the monuments of India, Vol II (London: Viking, 1989)

· Christopher Tadgell, The History of Architecture in India (London: Phaidon Press, 1990)

· Abhilash Shekhawat, "Stepwells of Gujarat." India's Invitation. 2010. Web. 29 March 2012.<http://www.indiasinvitation.com/stepwells_of_gujarat/>.

· Stepwells in India at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

· "Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent - glossary". Indoarch.org. Retrieved 2006-12-18.

External links· Stepwell Atlas

· India's Forgotten Stepwells at ArchDaily

.jpg?1372283662)

.jpg?1372283651)

.jpg?1372283874)

.jpg?1372284281)

.jpg?1372284239)