https://tinyurl.com/yxe5rkeo

-- Coper production and trade evidenced in Indus Script Corpora is traced back to Rgveda tradition of yajna

-- Mlecchita vikalpa hieroglyphs and Meluhha rebus readings traced to Rgveda times

-- sha-da-ya on the Anthropomorph may be a reading of साध्य m. (pl.) ‘they that are to be propitiated’, N. of a class of celestial beings (belonging to the गण-देवता q.v., sometimes mentioned in the Veda [see, RV. x, 90, 16 ]; in the ŚBr. their world is said to be above the sphere of the gods; according to Yāska [Nir. xii, 41 ] their locality is the Bhuvarloka or middle region between the earth and sun; in Mn. i, 22 , the Sādhyas are described as created after the gods with natures exquisitely refined, and in iii, 195 , as children of the Soma-sads, sons of Virāj; in the Purāṇas they are sons of Sādhyā, and their number is variously twelve or seventeen; in the later mythology they seem to be superseded by the Siddhas See सिद्ध; and their names are Manas, Mantṛ, Prâṇa, Nara, Pāna, Vinirbhaya, Naya, Daṉśa, Nārāyaṇa, Vṛṣa, Prabhu), RV. &c. &c. (Monier-Wiliams)

![]()

![]()

-- The expression 'mlecchita vikalpa' explains why the entire Indus Script Corpora is a wealth-accounting ledger of metal-work, lapidary-work (with gems, jewels, jewellery) documented by karṇaka 'scribe, engraver, accountant, supercargo, helmsman' Sign 342.

![]()

-- Mlecchita vikalpa, Indus Script writing system, lit. means 'alternative signifiers of Mleccha, meluhha, milakkhu, 'copper-bronze artisans'. Mleccha, Meluhha mispronounced words of Indian sprachbund, 'language union' resulting in various dialects/language forms of Bhāratam Janam (RV 3.53.12). Bharata, baran means 'alloy of 5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Marathi. Punjabi).

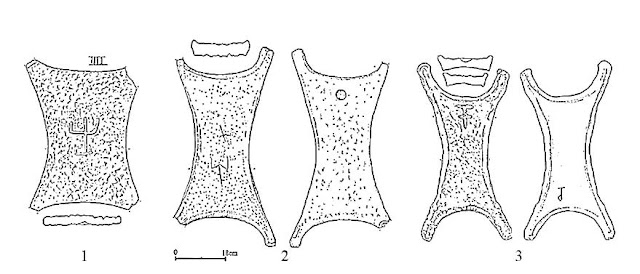

Naturally occurring arsenical bronze (copper + arsenic) artifacts. Nahal Mishmar 5th m. BCE. Tin-bronze revolution was unleashed when tin was alloyed with copper to create bell-metal; and when zinc was alloyed with coper to create brass.![]()

కండె [ kaṇḍe ] kaṇḍe. [Tel.] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. జొన్నకంకి. Mth. kã̄ṛ ʻstack of stalks of large milletʼ(CDIAL 3023). Rebus: kaṇḍ‘ furnace, fire-altar, consecrated fire’. Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. By shaping the tablets in fish-shapes, the intent is to convey the definitive message that the khāṇḍā 'implements' are made of metal (ayo 'fish' rebus: ayas 'metal').

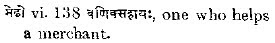

![]() h337, h338 Texts 4417, 4426 with two glyphs each on leaf-shaped, miniature Harappa tablets.

h337, h338 Texts 4417, 4426 with two glyphs each on leaf-shaped, miniature Harappa tablets.

A miniature, incised tablet from Harappa h329A has a fish-shaped tablet with two signs: fish + arrow (which combination was also pronounced as ayaskāṇḍa on a bos indicus seal Kalibangan032). aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'

अयस् ayas a. [इ-गतौ-असुन्] Going, moving; nimble. n. (-यः) 1 Iron (एति चलति अयस्कान्तसंनिकर्षं इति तथात्वम्; नायसोल्लिख्यते रत्नम् Śukra 4.169. अभितप्तमयोऽपि मार्दवं भजते कैव कथा शरीरिषु R.8.43. -2 Steel. -3 Gold. -4 A metal in general. अयस्मय ayasmaya, अयोमय ayomaya a. (-यी f.) Ved. Made of iron or of any metal. -यी N. of one of the three habitations of Asuras.अयस ayasa (At the end of comp.) See कार्ष्णायस, कालायस &c.अयोच्छिष्टम् ayocchiṣṭam Rust of iron.कार्ष्णायस kārṣṇāyasa a. (-सा f.) [कृष्णायस-अण्] Made of black iron; कार्ष्णायसोऽयं रथः U.3.43. -सम् Iron; एकेन नख- निकृन्तनेन सर्वं कार्ष्णायसं विज्ञातं भवति Ch. Up.6.1.6. ताम्रं कार्ष्णायसं चैव तैक्ष्ण्यादेवाभिजायते Rām.1.37.19. कार्ष्णायसमलङ्कार Ms.10.52.काल kāla a. (-ली f.) 1 Black, of a dark or dark-blue colour; Rām.5.17.9. Mb.8.49.48. -आयसम् iron. -a. made of iron; ततः कालायसं शूलं कण्टकैर्बहुभिश्च तम् Rām.7.8.15.

| अयस्—कंस m. an iron goblet, Pāṇ. 8-3, 46 Sch. अयस्—काण्ड m. n. ‘a quantity of iron’ or ‘excellent iron’, (g. कस्कादि q.v.) अयस् n. iron, metal, RV. &c. |

| an iron weapon (as an axe, &c.), RV. vi, 3,5 and 47, 10 |

| gold, Naigh. |

| steel. (Monier-Williams) |

| अयस् [cf. Lat. aes, aer-is for as-is; Goth. ais, Thema aisa; Old Germ. êr, iron; Goth. eisarn; Mod. Germ. Eisen.] [ID=14769.1] |

![]() The 'dotted circle' hieroglyph signifying the fish-eye may be dhA 'strand' rebus: dhAu 'mineral'.

The 'dotted circle' hieroglyph signifying the fish-eye may be dhA 'strand' rebus: dhAu 'mineral'.

Combination of ‘fish’ glyph and ‘four-short-linear-strokes’ circumgraph also pronounced the same text ayaskāṇḍa on another bos indicus seal m1118. This seal uses circumgraph of four short linear strokes which included a morpheme which was pronounced variantly as gaṇḍa ‘four’ (Santali).

Thus, the circumgraph of four linear strokes used on m1118 Mohenjo-daro seal was an allograph for ‘arrow’ glyph used on h329A Harappa tablet. poḷa 'zebu' rebus: poḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' See: bolad 'steel' (Russian) folad 'steel' (Old Persian).

"Chalcolithic Age in India is the first metal age, which indicates the first use of copper. This age extended from Chhota Nagpur plateau to the copper Gangetic basin. Some sites are found at Brahmagiri near Mysore and Navada Toli on the Narmada; among them Indus Valley is one of the important sites of this age. The Chalcolithic culture of Central, Eastern and Southern regions of India show altogether different features. The Chalcolithic culture ...Four cultural trends have been identified- Kayatha, Ahar or Banas, Malwa and Jorwe."

https://www.indianetzone.com/55/chalcolithic_age_india.htm

"The Chalcolithic (),[1] a name derived from the Greek: χαλκός khalkós, "copper" and from λίθος líthos, "stone" or Copper Age, also known as the Eneolithic or Aeneolithic (from Latin aeneus "of copper") is an archaeological period which researchers usually regard as part of the broader Neolithic (although scholars originally defined it as a transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age). In the context of Eastern Europe, archaeologists often prefer the term "Eneolithic" to "Chalcolithic" or other alternatives.In the Chalcolithic period, copper predominated in metalworking technology. Hence it was the period before it was discovered that by adding tin to copper one could create bronze, a metal alloy harder and stronger than either component.The archaeological site of Belovode, on Rudnik mountain in Serbia, has the worldwide oldest securely-dated evidence of copper smelting at high temperature, from c. 5000 BC (7000 BP ).The transition from Copper Age to Bronze Age in Europe occurs between the late 5th and the late 3rd millennia BC. In the Ancient Near East the Copper Age covered about the same period, beginning in the late 5th millennium BC and lasting for about a millennium before it gave rise to the Early Bronze Age." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chalcolithic

The Timna Valley (תִּמְנָע) is located in southern Israel in the southwestern Arava/Arabah, approximately 30 kilometres (19 mi) north of the Gulf of Aqaba and the city of Eilat. The area is rich in copper ore and has been mined since the 5th millennium BCE.

Mining tools. Chalcolithic copper mine in Timna Valley"The emergence of metallurgy may have occurred first in the Fertile Crescent. The earliest use of lead is documented here from the late Neolithic settlement of Yarim Tepe in Iraq,"The earliest lead (Pb) finds in the ancient Near East are a 6th millennium BC bangle from Yarim Tepe in northern Iraq and a slightly later conical lead piece from Halaf period Arpachiyah, near Mosul.[7] As native lead is extremely rare, such artifacts raise the possibility that lead smelting may have begun even before copper smelting."Copper smelting is also documented at this site at about the same time period (soon after 6000 BC), although the use of lead seems to precede copper smelting. Early metallurgy is also documented at the nearby site of Tell Maghzaliyah, which seems to be dated even earlier, and completely lacks pottery.The Timna Valley contains evidence of copper mining in 7000–5000 BC. The process of transition from Neolithic to Chalcolithic in the Middle East is characterized in archaeological stone tool assemblages by a decline in high quality raw material procurement and use. This dramatic shift is seen throughout the region, including the Tehran Plain, Iran. Here, analysis of six archaeological sites determined a marked downward trend in not only material quality, but also in aesthetic variation in the lithic artefacts. Fazeli et al. use these results as evidence of the loss of craft specialisation caused by increased use of copper tools. The Tehran Plain findings illustrate the effects of the introduction of copper working technologies on the in-place systems of lithic craft specialists and raw materials. Networks of exchange and specialized processing and production that had evolved during the Neolithic seem to have collapsed by the Middle Chalcolithic (c. 4500–3500 BC) and been replaced by the use of local materials by a primarily household-based production of stone tools...According to Parpola (2005), ceramic similarities between the Indus Civilization, southern Turkmenistan, and northern Iran during 4300–3300 BC of the Chalcolithic period suggest considerable mobility and trade. The term "Chalcolithic" has also been used in the context of the South Asian Stone Age. In Bhirrana, the earliest Indus civilization site, copper bangles and arrowheads were found. The inhabitants of Mehrgarh in present-day Pakistan fashioned tools with local copper ore between 7000–3300 BC. At the Nausharo site dated to 4500 years ago, a pottery workshop in province of Balochistan, Pakistan, were unearthed 12 blades or blade fragments. These blades are 12–18 cm (5–7 in) long and 1.2–2.0 cm (0.5–0.8 in) and relatively thin. Archaeological experiments show that these blades were made with a copper indenter and functioned as a potter's tool to trim and shape unfired pottery. Petrographic analysis indicates local pottery manufacturing, but also reveals the existence of a few exotic black-slipped pottery items from the Indus Valley." (Vasant Shinde and Shweta Sinha Deshpande, "Crafts and Technologies of the Chalcolithic People of South Asia: An Overview" Indian Journal of History of Science, 50.1 (2015) 42-54; Potts, Daniel T., ed. (2012-08-15). "Northern Mesopotamia". A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. 1. John Wiley & Sons, 2012. p. 302; Fazeli, H.; Donahue, R.E.; Coningham, R.A.E. (2002). "Stone Tool Production, Distribution and Use during the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic on the Tehran Plain, Iran". Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 40: 1–14. doi:10.2307/4300616. JSTOR 4300616; Méry, S; Anderson, P; Inizan, M.L.; Lechavallier, M; Pelegrin, J (2007). "A pottery workshop with flint tools on blades knapper with copper at Nausharo (Indus civilisation ca. 2500 BC)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (7): 1098–1116. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.10.002)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chalcolithic

आयसी, स्त्री, (अयसा निर्म्मिता । अयस् + अण् +ङीप् ।) लौहमयकवचः । तत्पर्य्यायः । अङ्गरक्षिणी२ जालिका ३ जालप्राया ४ । इति हेमचन्द्रः ॥--शब्दकल्पद्रुमः आयस āyasa a. (सी f.) [अयसो विकारः अण्] 1 Made of iron, iron, metallic; शतं मा पुर आयसीररक्षन् Ait. Up.4.5. आयसं दण्डमेव वा Ms.8.315; सखि मा जल्प तवायसी रसज्ञा Bv.2.59. -2 Armed with an iron weapon. -सी A coat of mail, an armour for the body. -सम् 1 Iron; मूढं वुद्धमिवात्मानं हैमीभूतमिवायसम् Ku.6.55; स चकर्ष परस्मात्तदयस्कान्त इवायसम् R.17.63. -3 Anything made of iron. -3 A weapon. -4 A wind instrument.(Apte)

आयस्कारि m. a descendant of Ayas-kāra

आयसीयःअयस्मन्निकृष्टदेशादौत्रि०स्त्रियांङीप्।एतियज्ञस्थानम्इणअसुन्।३वह्नौपु०।“अयाश्चाग्नेऽस्यनभिशस्त्ययाश्चसत्वमित्त्वमयाअसि।अयानोयज्ञंवहास्ययानोऽवेहिभेषजम्” यजु०।४हिरण्येनिरु०“रक्षोहाविचर्षणिरमियोनि-मयोहतम्अभ्यनूषतायोहतम्ऋ०९, १, २, ८०,“अयइतिहिरण्यनामेतिभा०“हिरण्यपाणिःप्रति-दोषमास्थात्अयोहनुर्यजतेइतिऋ०६, ७१, १,अयोहनुर्हिरण्मयहनुः” भा०।अयस्कंसा पु०न०।अयोविकारःकंसंपात्रंसत्वम्।लौहनिर्म्मितेपानपात्रे। --शब्दकल्पद्रुमः

आयसीय त्रि०अयसःसन्निकृष्टदेशादि०कुशा०छण्।लौहसन्निकृष्टदेशादौ।आयस्कार पु०अयस्कारएवस्वार्थेअण्।लौहकारेत्रिका०--वाचस्पत्यम्

आयसीय mfn. (fr. अयस्), belonging to or made of iron, (g. कृशाश्वादि, Pāṇ. 4-2, 80. )

| आयस mf(ई)n. (fr. अयस्), of iron, made of iron or metal, metallic, RV. ; ŚBr. ; KātyŚr. ; MBh. ; Yājñ. &c. [ID=25831] |

| iron-coloured, MBh. v, 1709 |

| armed with an iron weapon, L. |

| आयसी f. armour for the body, a breastplate, coat of mail, L. |

| (also) an iron vessel, Viṣṇ. |

| आयस n. iron |

| anything made of iron, Ragh. ; Kum. &c. |

| a wind-instrument, KātyŚr. xxi, 3, 7. |

I submit that the expression कल्पन्ताम् in Yajurveda 18.13 read with कल्पेषु in R̥gveda 9.9.7 (interpreted by सायण as कल्पनीयेष्वहःसु) is a reference to the purification of metals in the rites, the process of yajna.In the context of Ayurveda, Caraka explains कल्प -उपनिषद् as pharmacology (Caraka 1.4.). Thus, I submit that kalpa in R̥gveda is a reference to metallurgy or material science or lapidary working with fire and materials such as the following mantra-s: stone, clay, rock, mountain, sand, herb, gold, pyrite (alloy), iron, coper, lead, tin -- all to be processed (and purified) in Yajna:

अश्मा च मे मृत्तिका च मे गिरयश् च मे पर्वताश् च मे सिकताश् च मे वनस्पतयश् च मेहिरण्यं च मे अयस् च मे श्यामं च मे लोहं च मे सीसं च मे त्रपु च मे यज्ञेन कल्पन्ताम् ॥-- शुक्लयजुर्वेदः/अध्यायः १८ वसोर्धारादि मन्त्राः १३

In dialects of Bharatiya sprachbund (speech union), the Meluhha word gains the following meaning expansions of 'skill', 'preparing, clipping', for e.g. cutting a nib, clipping from a metal sheet:

Tu. kalpuni to learn, study; kalpāvuni to teach, instigate; (B-K.) kalpādi a learned man, sophist; hypocrite. Te. kaṟacu to learn, study; kaṟapu to teach; n. instigation, incitement; kaṟapincu to cause to teach; kaṟudu ability, skill, cleverness; kala an art, a science. Kol. karp- (karapt-) to learn, teach; (SR.) karāp- to learn; karīl- to understand. Nk. karap- to learn.(DEDR 1297)

kálpa ʻ capable ʼ ŚBr., m. ʻ rule, practice ʼ RV., ʻ an age ʼ MBh. 2. *karpa -- . [√kI̊p]1. Pa. Pk. kappa -- m. ʻ rule, rite, age ʼ; Paš. kapaya ʻ in the middle of ʼ IIFL iii 3, 95; S. kapu m. ʻ knife ʼ; L. kapp m. ʻ cut, breach ʼ (→ Brah. kap ʻ half ʼ); N. kāp ʻ interstice between fingers ʼ; B. kāp ʻ cutting a nib, pen nib ʼ; Or. kāpa ʻ mask, false appearance ʼ; H. kāp m. ʻ cutting, slice ʼ; G. kāp m. ʻ cut, wound ʼ, kāpɔ m. ʻ cutting, slit, streak, line ʼ, kāplɔ m. ʻ a cutting of cloth ʼ, ˚lī f. ʻ clippings ʼ; M. kāp m. ʻ slice of fruit ʼ; Si. kapa ʻ an age ʼ.2. K. kraph, dat. ˚pas m. ʻ chopping, cutting ʼ.kalpana n. ʻ cutting ʼ VarBr̥S., ˚nā -- f. ʻ arranging ʼ Mn., ʻ making ʼ Suśr., ˚nī -- f. ʻ scissors ʼ lex., karpaṇa -- n. ʻ weapon ʼ Daś. [√kI̊p] kalpaka m. ʻ barber ʼ Kauṭ. [√kI̊p]Si. kapuvā ʻ barber ʼ.Pa. kappana -- n. ʻ arranging, preparing ʼ, ˚nā -- f. ʻ fixing a horse's harness ʼ; Pk. kappaṇa -- n. ʻ cutting ʼ, ˚ṇā<-> ʻ arranging ʼ, ˚ṇī f. ʻ shears ʼ; G. kāpṇī f. ʻ reaping a field, goldsmith's clip ʼ; M. kāpaṇ f. ʻ shaving ʼ, kāpṇī f. ʻ reaping ʼ. kalpáyati ʻ sets in order ʼ RV., ʻ trims, cuts ʼ VarBr̥S. [Cf. kr̥pāṇa -- m. ʻ knife ʼ Pāṇ.: √kI̊p]Pa. kappēti ʻ causes to fit, prepares, trims ʼ; Pk. kappēi ʻ makes, arranges ʼ; S. kapaṇu ʻ to cut ʼ; L. kappaṇ ʻ to cut, reap ʼ, awāṇ. kappuṇ; P. kappṇā ʻ to cut, kill ʼ; N. kapnu ʻ to carve, chisel ʼ; G. kāpvũ ʻ to cut ʼ; M. kāpṇẽ ʻ to cut, shave ʼ; Ko. kāppūka ʻ to cut ʼ; Si. kapanavā ʻ to cut, cut off, reap ʼ.Addenda: kalpáyati: S.kcch. kapṇū ʻ to cut ʼ; Md. kafanī ʻ stabs ʼ.*kalpiya ʻ suitable ʼ, kalpya -- VarBr̥S. [√kI̊p]Pa. Pk. kappiya -- ʻ suitable ʼ; Si. käpa ʻ suitable (esp. for offering to god or demon), an offering ʼ.(CDIAL 2941-2945)

कल्पः, पुं, (कल्प्यते विधीयते असौ । कृप् +कर्म्मणि घञ् ।) विधिः । (यथा मनुः ३ । १४७ ।“एष वै प्रथमः कल्पः प्रदाने हव्यकव्ययोः ।अनुकल्पस्त्वयं ज्ञेयः सदा सद्भिरनुष्ठितः” ॥(कल्पयति सृष्टिं नाशं वा अत्र । कृप् + णिच् +अधिकरणे अप् ।) ...कल्पनं, क्ली, (कृप् + भावे ल्युट् ।) कॢप्तिः । छेदनम् ।इति त्रिकाण्डशेषः ॥...कल्पनी, स्त्री, (कल्पयति केशानीन् छिनत्ति अनया ।कृप् छेदने + करणे ल्युट् । ततो ङीप् ।)कर्त्तनी । इति हेमचन्द्रः ॥ काँचि इति भाषा ॥--शब्दकल्पद्रुमः

कल्प पु० कल्पते समर्थो भवति स्वक्रियायै विरुद्धलक्षणया असमर्थो-भवति वाऽत्र, कृपू सामर्थ्ये विरुद्धलक्षणया असामर्थ्ये वाआधारे घञ् कल्पयति सृष्टिं विनाशं वात्र कृप-णिच्-आधारे अच् । ...कल्पनी स्त्री कृप--छेदने करणे ल्युट् ङीप् । कर्त्तर्य्याम् ।(काञ्चि) हेमच० ।--वाचस्पत्यम्

सायणभाष्यम्

ऋग्वेदः - मण्डल ९सूक्तं ९.९कश्यपोऽसितो देवलो वा।

दे. पवमानः सोमः। गायत्री। RV 9.9.7 अवा कल्पेषु नः पुमस्तमांसि सोम योध्या ।

तानि पुनान जङ्घनः ॥७॥

अव । कल्पेषु । नः । पुमः । तमांसि । सोम । योध्या । तानि । पुनान । जङ्घनः ॥७ हे "पुमः पुमन् सोम "कल्पेषु कल्पनीयेष्वहःसु "नः अस्मान् "अव रक्ष । अपि च "पुनान हे पवमान "सोम त्वं "योध्या योधनीयानि “तमांसि रक्षांसि यानि "तानि जङ्घनः नाशय ॥ Translation (Griffith) RV 9.9.7: Aid us in holy rites, O Man: O Pavamana, drive away Dark shades that must be met in fight.

Translation (Wilson) RV 9.9.7: Protect us, manly Soma, in the days of sacrifice purifier, destroy those powers of darkness against which we must contend. [In the days of sacrifice: kalpes.u = kalpaniyes.vahahsu, in the days which have to be reckoned; another interpretation: 'in our rites']. |

कल्पित kalpita a. Arranged, made, fashioned, formed; उत्सृज्य कुसुमशयनं नलिनीदलकल्पितस्तनावरणम् Ś.3.21; see क्लृप् caus. -तः An elephant armed or caparisoned for war.कल्पनम् kalpanam [क्लृप्-ल्युट्] 1 Forming, fashioning, arranging. -2 Performing, doing, effecting. -3 Clipping, cutting. -4 Fixing. -5 Anything placed upon another for decoration. -ना 1 Fixing, settlement; अनेकपितृकाणां तु पितृतो भागकल्पना Y.2.120;247; Ms.9.116. -2 Making, performing, doing. -3 Forming, arranging; विषमासु च कल्पनासु Mk.3.14; केश˚ Mk.4. -4 Decorating, ornamenting. -5 Composition. -6 Invention. -7 Imagination, thought; कल्पनापोढः Sk. P.II.1.38 = कल्पनाया अपोढःकल्प mf(आ)n. (√कॢप्), practicable, feasible, possible, ŚBr. ii, 4, 3, 3; One of the six Vedāṅgas, i. e. that which lays down the ritual and prescribes rules for ceremonial and sacrificial acts; शिक्षा कल्पो व्याकरणम् Muṇḍ 1.1.5 (Apte)

कल्प m. a sacred precept, law, rule, ordinance (= विधि, न्याय), manner of acting, proceeding, practice (esp. that prescribed by the Vedas), RV. ix, 9, 7 ; AV. viii, 9, 10; xx, 128, 6-11 ; MBh. ; investigation, research Comm. on Sāṃkhyak. the art of preparing medicine, pharmacy; -उपनिषद् pharmacology (Caraka 1.4.)

शब्दकल्पद्रुमः śabdakalpadruma -- excerpts for selected etyma embedded --validates the Indus Script cipher as mlecchita vikalpa, 'writing system of mleccha ,'copper artisans'. Mlecchita vikalpa means Meluhha cipher and is related to documentation of artisan work using caṣāla on Yupa, gōdhūma, and engaged in āyasamutpati, 'production of metal alloys'.

म्लेच्छास्यं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छे म्लेच्छदेशे आस्यमुत्पत्ति-रस्य ।) ताम्रम् । इति हारावली ॥ This is a text which lists synonyms. I suggest that the explanatory expression should be read as आयसमुत्पत्ति, i.e. the country in which ayas 'alloy metals' are produced and yielding a specific reference to mining of copper ताम्रम् which is a synonym of म्लेच्छास्यं।.

अयस्कार, पुं, (अयोविकारं करोति, क्त + अण्उपपदसमासः ।) प्रजङ्घाग्रः । जङ्घाग्रभागः ।इति त्रिकाण्डशेषः ॥ लौहकारः । अयस्करोतीतिव्युत्पत्त्या ॥ ...अयस्कान्तः, पुं, (अयस्सु कान्तः रमणीयः ।) लौह-विशेषः । कान्तलोह इति ख्यातः । तत्प-र्य्यायः । कान्तलोहं २ कान्तं ३ लौहकान्तकं४ कान्तायसं ५ कृष्णलोहं ६ महालोहं ७ ।अस्य गुणाः । तीक्ष्णत्वं । उष्णत्वं । रूक्षत्वं ।पाण्डुशोथकफपित्तहरत्वं । रसायनत्वं । अनु-त्तमत्वञ्च । स चतुर्व्विधः । भ्रामकः १ चुम्बकः२ रोमकः ३ स्वेदकः ४ । एते रसायने उत्तरोत्तरगुणिनः ।आयसं, क्ली, (अयस् + अण् ।) लौहं । इतिभरतः राजनिर्घण्टश्च ॥ अयोनिर्मितादौ, त्रि ॥(यथा महाभारते, --“आयसं हृदयं मन्ये तस्य दुष्कृतकर्म्मणः” ।यथा मनुः, ८ । ३१५ ।“शक्तिं चोभयतस्तीक्ष्णामायसं दण्डमेव वा” ।रघुवंशे, १७ । ६३ ।“स चकर्ष परस्मात् तदयस्कान्त इवायसम्” ।(अयोजनितार्थे यथा, --“विपाके कटु शीतञ्च सर्व्वश्रेष्ठं तदायसम्” ॥इति वैद्यकचक्रपाणिसंग्रहे ॥) आयसी, स्त्री, (अयसा निर्म्मिता । अयस् + अण् +ङीप् ।) लौहमयकवचः । तत्पर्य्यायः । अङ्गरक्षिणी२ जालिका ३ जालप्राया ४ । इति हेमचन्द्रः ॥--शब्दकल्पद्रुमः

ऋग्वेदः - मण्डल ६ सूक्तं ६.७१ बार्हस्पत्यो भरद्वाजः

| दे. सविता। जगती, ४-६ त्रिष्टुप् । |

उदु ष्य देवः सविता हिरण्यया बाहू अयंस्त सवनाय सुक्रतुः ।

घृतेन पाणी अभि प्रुष्णुते मखो युवा सुदक्षो रजसो विधर्मणि ॥१॥

“देवः द्योतमान: "सुक्रतुः सुकर्मा “स्यः स प्रसिद्धः "सविता “हिरण्यया हिरण्मयौ आत्मीयौ “बाहू "सवनाय सुवनाय दानाय वा “उत् "अयंस्त उद्यच्छति । किंच “मखः मंहनीयः "युवा नित्यतरुणः "सुदक्षः सुप्रज्ञः "रजसः लोकस्योदकस्य वा "विधर्मणि विधारणे स्थितः “घृतेन उदकेन पूर्णौ स्वौ "पाणी "अभि “प्रुष्णुते अभिप्रेरयति ॥--सायणभाष्यम्

ऋग्वेदः - मण्डल १

सूक्तं १.५७

सव्य आङ्गिरसः

अस्मै भीमाय नमसा समध्वर उषो न शुभ्र आ भरा पनीयसे ।

यस्य धाम श्रवसे नामेन्द्रियं ज्योतिरकारि हरितो नायसे ॥३॥

हे "उषः उषोदेवते "शुभ्रे शोभने त्वं "भीमाय शत्रूणां भयंकराय "पनीयसे अतिशयेन स्तोतव्याय "अस्मै इन्द्राय "अध्वरे हिंसारहितेऽस्मिन्यागे । "न इति संप्रत्यर्थे । तथा च यास्कः - ‘ अस्त्युपमार्थस्य संप्रत्यर्थे प्रयोग इहेव निधेहि ' (निरु. ७. ३१) इति । संप्रतीदानीं "नमसा नमो हविर्लक्षणमन्नं "सम् "आ “भर सम्यक् संपादय । “धाम सर्वस्य धारकं "नाम स्तोतृषु नमनशीलं प्रसिद्धं वा "इन्द्रियम् इन्द्रत्वस्य परमैश्वर्यस्य लिङ्गं यस्य इन्द्रस्य एवंविधं "ज्योतिः “श्रवसे अन्नाय हविर्लक्षणान्नलाभार्थम् "अयसे इतस्ततो गमनाय "अकारि क्रियते । "हरितो "न । यथाश्वान्सादिनः स्वाभिलषितदेशं गमयन्ति तद्वदिन्द्रोऽपि स्वाभिमतहविर्लाभाय स्वकीयं तेजो गमयतीति भावः ॥ उषः । पादादित्वात् निघाताभावः । शुभ्रे । 'शुभ दीप्तौ'। स्फायितञ्चि° 'इत्यादिना रक् । भर ।'हृग्रहोर्भः'इति भत्वम् ।'द्व्यचोऽतस्तिङः'इति दीर्घः । पनीयसे । पनतेः स्तुत्यर्थात् बहुलवचनात् कर्मणि असुन् । तस्मात् आतिशायनिके ईयसुनि ‘टे: 'इति टिलोपः । अकारि । 'छन्दसि लुङ्लङ्लिटः'इति वर्तमाने कर्मणि लुङ् । यद्वृत्तयोगादनिघातः । अडागम उदात्तः । अयसे ।'अय गतौ'इत्यस्मात् भावे असुन् ॥--सायणभाष्यम्

ऋग्वेदः - मण्डल १

सूक्तं १.१६३

दीर्घतमा औचथ्यः

हिरण्यशृङ्गोऽयो अस्य पादा मनोजवा अवर इन्द्र आसीत् ।

देवा इदस्य हविरद्यमायन्यो अर्वन्तं प्रथमो अध्यतिष्ठत् ॥९॥

अयमश्वः “हिरण्यशृङ्गः हितरमणीयशृङ्गो वा उन्नतशिरस्को हृदयरमणशृङ्ग स्थानीयशिरोरुहो वा “अस्य “पादाः “अयः अयोमयाः अयःपिण्डसदृशा इत्यर्थः । तथा “मनोजवाः मनोवेगाः । अथवा एतदिन्द्रविशेषणम् । ईदृशस्याश्वस्य सामर्थ्यं प्रति मनोवेगः “इन्द्रः अपि "अवरः निकृष्टः “आसीत् । किंच “अस्य अश्वस्य हविरद्यं हविषः अदनं भक्षणम् ॥ स्वार्थिको यत् ॥ अदनयोग्यं हविर्वा अपेक्ष्य “देवा “इत् सर्वेऽपि देवाः "आयन् प्राप्ताः । “यः इन्द्रः "अर्वन्तं “प्रथमः प्रथमभावी सन् “अध्यतिष्ठत् अधिष्ठितवान् स्वहविष्ट्वेन'स्वकीयत्वेन वा आश्रितवानित्यर्थः । ‘इन्द्र एणं प्रथमो अध्यतिष्ठत्'इति ह्युक्तम् --सायणभाष्यम्

अयस् न० एति चलति अयस्कान्तसान्निध्यात् इण--असुन् ।लौहे धातुभेदे तस्य स्थिरत्वेऽपि अयस्कान्तसान्निध्याच्चण-नात्तथात्वम् । “सुहृदयोहृदयः प्रतिगर्ज्जताम्” “अभितप्त-मयोऽपि मार्द्दवं भजते कैव कथा शरीरिणाम्” इति च रघुः“ताम्रायःकांस्यरैत्यानां त्रिपुणः सीसकस्य च” अयः कांस्य-पलानाञ्च द्वादशाहमपान्नता” इति च मनुः । अयसः पाकादिअमृतसारशब्दे ३२६ पृष्ठे दृश्यम् । अधिकं लीहशब्देवक्ष्यते । उपचारात् २ अयोनिर्स्मिते शस्त्रादावपि । “तेजो-ऽयसो न धाराम् ऋ० ६, ३, ५, अयसः अयोमयस्यपरश्वादेर्धाराम्” भा० । हिरण्यशृङ्गोऽयो अस्यपादाः ऋ०१, १६३, ९ भावे असुन् । ३ गमने न० । ‘ज्योतिरकारि हरितीनाऽयसे ऋ० १, ५७, ३ “अयसे गमनाय” भा० अयसा-निर्म्मितम् अण् । आयसम् लौहमये कठाहादौ अयसो-विकारः अण् आयसः । लौहविकारे ‘अयस्कान्तैवायसम्’रघुः “आयसेन तु पात्रेणेत्यादि २७८ पृष्ठे दर्शितम् ।मयट् अयोमयः । वेदे तु अयस्मयादि० नि० अयस्सयः ।लोहविकारे त्रि० स्त्रियां ङीप् । चतुरर्थ्यां छण् ।आयसीयः अयस्मन्निकृष्टदेशादौ त्रि० स्त्रियां ङीप् ।एति यज्ञस्थानम् इण असुन् । ३ वह्नौ पु० ।“अयाश्चाग्नेऽस्यनभिशस्त्ययाश्च सत्वमित्त्वमया असि ।अयानो यज्ञं वहास्यया नोऽवेहि भेषजम्” यजु० ।४ हिरण्ये निरु० “रक्षोहा विचर्षणिरमियोनि-मयोहतम् अभ्यनूषतायोहतम् ऋ० ९, १, २, ८०,“अय इति हिरण्यनामेति भा० “हिरण्यपाणिः प्रति-दोषमास्थात् अयोहनुर्यजते इति ऋ० ६, ७१, १,अयोहनुर्हिरण्मयहनुः” भा० ।अयस्कंसा पु० न० । अयोविकारः कंसं पात्रंसत्वम् ।लौहनिर्म्मिते पानपात्रे ।अयस्कर्ण्णी स्त्री अय इव कर्ण्णावस्य गौ० ङीष् ।लौहतुल्यकठिनकर्ण्णयुक्तायां स्त्रियाम् ।अयस्कान्त पु० अयस्सु कान्तः रमणीयः कस्कादि-त्वात् सत्वम् । (कान्तिलौह) इति ख्याते १ लौहभेदे ।अयसां कान्तः इष्टः सन्निधिमात्रेणाकर्षकत्वात् । सन्निधि-मात्रेण लौहाकर्षके (चुम्वक) इति ख्याते २ प्रस्तरभेदे ।“शम्भोर्यतध्वमाक्रष्टुमयस्कान्तेन लौहवत्” कुमा० “स चकर्षपरस्मात्तदयस्कान्तमिवायसम्” रघुः । अयस्कान्तेनाकर्ष-णीयशल्यापनयनार्थे ३ व्रणचिकित्साभेदे यथोक्तं सुश्रुते“अनुलोममनवबद्वमकर्णमनल्पव्रणमुखमयस्कान्तेन” ।अयस्काम त्रि० अयः कामयते कम--अण् उप० स० सत्वम् ।लौहाभिलाषिणि ।अयस्कार त्रि० अयोविकारं करोति कृ--अण् उप० स० सत्वम् । लौहकारे (कामार) ।अयस्कुम्भ पु० अयोविकारः कुम्भः सत्वम् । लौहमये घटे ।अयस्कुशा स्त्री अयःसहिता कुशा शाक० त० सत्वम् ।लौहसहितकुशायाम् ।अयस्कृति स्त्री अयसा कृतिः चिकित्साप्रक्तिया सत्वम् । सुश्रु-तोक्तेमहाकुष्ठचिकित्साभेदे “अथ ऊर्द्ध्वमयस्कृतीर्वक्ष्यामः ।तीक्ष्णलोहपत्राणि तनूनि लवणवर्गप्रदिग्धानि गोमयाग्नि-प्रतप्रानि त्रिफलाशालसारादिकषायेण निर्वापयेत् षोड़श-वारांस्ततः स्वदिराङ्गारतप्तान्युपशान्ततापानि सूक्ष्म-चूर्णानि कारयेद्गाढतान्तवपरिस्नावितानि ततो यथाबलंमात्रां सर्पिर्मधुभ्यां संसृज्योपयुञ्जीत । जीर्णेयथाव्याध्य-नम्लमलवणमाहारं कुर्व्वीत । तुलामुपयुज्य कुष्ठमेहमेदःश्वयथुपाण्डुरोगोन्मादापस्मारानपहृत्य वर्षशतं जीवतितुलायां तुलायां वर्षशतगुणोत्कर्षः । एतेन सर्व्वलौहेष्वय-स्कृतयो व्याख्याताः ।अयस्थूण पु० अयोनिर्म्मितः स्थूणः वा विसर्गलोपः ।लोहमये १ गृहस्थूणे ६ ब० । थाविधगृहस्थूणयुक्ते २ गृहस्थे ।“अयस्थूणगृहपतीनां वै” शतव्रा० अयस्थूणा गृहपतय-स्तेपामिति तेषाम् हीनद्रव्यकत्वादाक्षेपः भा० । ७ त०३ अयोमयाक्षे रथादौ त्रि० । “व्युष्टावयस्थूणमुदितासूर्य्यस्य” ऋ० ५, ६२, ८, अयस्थूणमयोमयशङ्कुं गर्त्तंरथं वेति भा० । ४ऋषिभेदे पु० तस्य गोत्रम् अण्आयस्थूणः तस्य बहुषु लुक् । अयस्थूणाः । गौ०पाटात् ङीष् अयस्थूणी ।अयस्पात्र न० अयोमयं पात्रं सत्वस् । लौहमये पात्रे ।अयस्मय त्रि० अयोविकारः अयस् + मयट् वेदे नि० । भत्वम्स्त्रियां ङीप् । अयोमये लौहमये “असुरा एषु लोकेषुपुरश्चक्रिरेऽयस्मयोमेवास्मिँलोके रजतामन्तरीक्षे हरिणींदिवि” शतव्रा० । “भूम्या अयस्मयम् पातु” अथ० ५, २८, ९,शतमृष्टिरयस्मयीः अथ० ४, ३७, ८, छन्दसीति प्रायिकतेन लोकेऽपि “पंरिभ्रमन्तमनिशं तीक्ष्णधारमयस्मयम्”भा० आ० प० “ततः शक्तिं गृहीत्वा तु रुक्मदण्डमयस्मयीम्भा० द्रो० प० ।अयस्मयादि पु० ६ त० “अयस्मयादीनि छन्दसि” पा० उक्तेभत्वादिकार्य्यार्थे निपाताङ्गे अकृतिगणभेदे ।आयस त्रि० अयसो विकारः अण् स्त्रियां ङीप् । लौहमये ।“शक्तिञ्चोभयतस्तीक्ष्णामायसं दण्डमेव वा” “पुमांसंदाहयेत् पापं शयने तप्तआयसे” इति च मनुः । “स चकर्ष-परस्मात् तत् अयस्कान्त इवायसम्” रघुः । “मूढ़बुद्धिमिवा-त्मानं हैमीभूतमिवायसम्” कुमा० । २ लौहमयकवचे च३ अङ्गरक्षिण्यां जालिकायां स्त्री । अयएव स्वार्थेअण् ।४ लौहे । ततः विकारेमयट्लोहमये त्रि० स्त्रियां ङीप् ।आयसीय त्रि० अयसः सन्निकृष्टदेशादि० कुशा० छण् ।लौहसन्निकृष्टदेशादौ ।आयस्कार पु० अयस्कार एव स्वार्थे अण् । लौहकारे त्रिका०--वाचस्पत्यम्

- Ardhamagadhi Prakrit: 𑀫𑀺𑀮𑀓𑁆𑀔𑀼 (milakkhu), 𑀫𑁂𑀘𑁆𑀙 (meccha)

- → Classical Newar: म्लेछ

- → Old Javanese: [script needed] (mleccha), [script needed] (maleca)

- Maharastri Prakrit: 𑀫𑀺𑀮𑀺𑀘𑁆𑀙 (miliccha)

- Old Marathi: मलैस (malaisa)

- → Old Marathi: म्लेंछ (mleṃcha)

- Pali: milakkha, milakkhu (a borrowing from another Prakrit), milāca

- Sauraseni Prakrit: [Term?]

Who are mleccha and dasyu? -- Manu calls all mleccha speakers as dasyu.

In Aitareya Brahmana (vii.18), dasyu are recognized as descendants of Vis’vamitra; they are called दस्यूणाम् भूयिष्ठाः (शाङ्खायन-श्रौत-सूत्र XV,26,7)

In Manu, dasyu signify ‘uncivilized people’ (Manu v,131; x.32.45) Thus, mleccha and dasyu are attributes of Aryan people who have neglected the essential rites of pious people.

म्लेच्छवाचश्चार्यवाचः सर्वे ते दस्यवः स्मृताः (Manu smrti.10.45). mleccha speakers are dasya. दस्युः dasyuḥ [दस्-युच्] 1 N. of a class of evil beings or demons, enemies of gods and men, and slain by Indra, (mostly Vedic in this sense). -2 An outcast, a Hindu who has become an outcast by neglect of the essential rites; cf. Ms.5.131;10.45; दस्यूनां दीयतामेष साध्वद्य पुरुषा- धमः Mb.12.173.20. -3 A thief, robber, bandit; नीत्वोत्पथं विषयदस्युषु निक्षिपन्ति Bhāg.7.15.46; पात्रीकृतो दस्यु- रिवासि येन Ś.5.20; R.9.53; Ms.7 143. -4 A villain, miscreant; दस्योरस्य कृपाणपातविषयादाच्छिन्दतः प्रेयसीम् Māl.5.28. -5 A desperado, violator, oppressor (Apte) दस्यु m. ( √ दस्) enemy of the gods (e.g. श्/अम्बर , श्/उष्ण , च्/उमुरि , ध्/उनि ; all conquered by इन्द्र , अग्नि , &c ) , impious man (called अ-श्रद्ध्/अ , अ-यज्ञ्/अ , /अ-यज्यु , /अ-पृनत् , अ-व्रत्/अ , अन्य-व्रत , अ-कर्म्/अन्) , barbarian (called अ-न्/आस् , or अन्-/आस् " ugly-faced " , /अधर , " inferior " , /अ-मानुष , " inhuman ") , robber (called धन्/इन्) RV. AV. &c; any outcast or Hindu who has become so by neglect of the essential rites (Manu); Name of a man RV. viii , 51 ; 55 f ; द्/अस्यवे स्/अहस् n. violence to the दस्यु (N. of तुर्वीति) , i , 36 , 18)(Monier-Williams) Agni, bring Navavastva and Brhadratha, Turviti, to subdue the foe.

In my view, the detailed essay on Dasyu in the Vedic Index is the most comprehensive presentation of textual evidence related to an understanding the attributes of dasyu as a group of people.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

म्लेच्छ अपशब्दे वा चु० उभ० पक्षे भ्वा० पर० अक०सेट् । म्लेच्छयति ते म्लेच्छति अमम्लेच्छत् त अम्लेच्छीत्

म्लेच्छ पु० म्लेच्छ--घञ् । १ अपशब्दे “म्लेच्छोह वा नामयदप्रशब्द” इति श्रुतिः । कर्त्तरि अच् । २ पामरजातौ,३ नीचजातौ च पुंस्त्री० स्त्रियां ङीष् “गोमांसखादकोयस्तु विरुद्धं बहु भाषते । सर्चाचारविहीनश्च म्लेच्छइत्यभिधीयते” बौधायनः । ४ पापरते त्रि० मेदि० ।५ हिङ्गुले न० राजनि० ।म्लेच्छजाति स्त्री म्लेच्छाभिधा जातिः । मांसादिभक्षकेकिरातादिजातिभेदे अमरः ।म्लेच्छदेश पु० म्लेच्छाधारो देशः । चातुर्वर्ण्याचाररहितेदेशे अमरः । “चातुर्वर्ण्यव्यवस्थानं यस्मिन् देशे नविद्यते । म्लेच्छदेशः स विज्ञेय आर्य्यावर्त्तस्ततःपरम्” ।म्लेच्छभोजन न० म्लेच्छैर्भुज्यते भुज--कर्मणि ल्युट् ।१ यावके अन्नभेदे शब्दर० । २ गोधूमे पु० त्रिका० ।म्लेच्छमण्डल न० ६ त० । म्लेच्छदेशे हेमच० ।म्लेच्छमुख न० म्लेच्छानां मुखमिव रक्तत्वात् । ताम्रे अमरः ।म्लेच्छास्यमप्यत्र हारा० ।म्लेच्छित न० म्लेच्छ--क्त । अपशब्दे असंस्कृतशब्दे हारा० ।

https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/वाचस्पत्यम्/

म्लिष्टं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छ् + क्तः + “क्षुब्धस्वान्तध्वान्तलग्न-म्लिष्टविरिब्धेत्यादि ।” ७ । २ । १८ । इतिनिपातितम् ।) अस्पष्टवाक्यम् । तत्पर्य्यायः ।अविस्पष्टम् २ । इत्यमरः । १ । ६ । २१ ॥म्लिष्टः, त्रि, (म्लेच्छ + क्तः ।) अव्यक्तवाक् । म्लानः ।इति मेदिनी । टे, २५ ॥म्लुच, उ इर् गत्याम् । इति कविकल्पद्रुमः ॥(भ्वा०-पर०-सक०-सेट् ।) उ, म्लोचित्वा म्लुक्त्वा ।इर्, अम्लु चत् अम्लोचीत् । इति दुर्गादासः ॥म्लेच्छ, कि देश्योक्तौ । इति कविकल्पद्रुमः ॥ (चुरा०-वा भ्वा०-पर०-अक०-सक० च-सेट् ।) देश्याग्राम्या उक्तिर्देश्योक्तिरसंस्कृतकथनमित्यर्थः ।कि, म्लेच्छयति म्लेच्छति मूढः । अन्तर्विद्यामसौविद्बान्न म्लेच्छति धृतव्रत इति हलायुधः ॥अनेकार्थत्वादव्यक्तशब्देऽपि । तथा चामरः ।अथ म्लिष्टमविस्पष्टमिति । म्लेच्छ व्यक्तायां वाचिइति प्राञ्चः । तत्र रमानाथस्तु । म्लेच्छति वटु-र्व्यक्तं वदतीत्यर्थः । अव्यक्तायामिति पाठे कुत्-सितायां वाचीत्यर्थः ।‘तत्सादृश्यमभावश्च तदन्यत्वं तदल्पता ।अप्राशस्त्यं विरोधश्च नञर्थाः षट् प्रकीर्त्तिताः ॥’इति भाष्यवचनेन नञोऽप्राशस्त्यार्थत्वात् इतिव्याख्यानाय हलायुधोक्तमुदाहृतवान् । इतिदुर्गादासः ॥म्लेच्छं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छस्तद्देशः उत्पत्तिस्थानत्वेना-स्त्यस्य । अर्शआद्यच् ।) हिङ्गुलम् । इतिराजनिर्घण्टः ॥ (तथास्य पर्य्यायः ।“हिङ्गुलन्दरदं म्लेच्छमिङ्गुलञ्चूर्णपारदम् ॥”इति भावप्रकाशस्य पूर्ब्बखण्डे प्रथमे भागे ॥)म्लेच्छः, पुं, (म्लेच्छयति वा म्लेच्छति असंस्कृतंवदतीति । म्लेच्छ् + अच् ।) किरातशवरपुलि-न्दादिजातिः । इत्यमरः ॥ पामरमेदः । पाप-रक्तः । अपभाषणम् । इति मेदिनी । छे, ६ ॥म्लेच्छादीनां सर्व्वधर्म्मराहित्यमुक्तं यथा, हरि-वंशे । १४ । १५ -- १९ ।“सगरः स्वां प्रतिज्ञाञ्च गुरोर्व्वाक्यं निशम्य च ।धर्म्मं जघान तेषां वै वेशान्यत्वं चकार ह ॥अर्द्धं शकानां शिरसो मुण्डयित्वा व्यसर्जयत् ।जवनानां शिरः सर्व्वं काम्बोजानान्तथैव च ॥पारदा मुक्तकेशाश्च पह्नवाः श्मश्रुधारिणः ।निःस्वाध्यायवषट्काराः कृतास्तेन महात्मना ॥शका जवनकाम्बोजाः पारदाः पह्नवास्तथा ।कोलसप्याः समहिषा दार्व्वाश्चोलाः सकेरलाः ।सर्व्वे ते क्षत्त्रियास्तात धर्म्मस्तेषां निराकृतः ॥वशिष्ठवचनाद्राजन् सगरेण महात्मना ॥”शकानां शकदेशोद्भवानां क्षत्त्रियाणाम् । एवंजवनादीनामिति । अत्र जवनशब्दस्तद्देशोद्भव-वाची चवर्गतृतीयादिः । जवनो देशवेगिनो-रिति त्रिकाण्डशेषाभिधानदर्शनात् ॥ * ॥ तेषांम्लेच्छत्वमप्युक्तं विष्णुपुराणे । तथाकृतान् जवना-दीनुपक्रम्य ते चात्मधर्म्मपरित्यागात् म्लेच्छत्वंययुरिति । बौधायनः ।“गोमांसखादको यश्च विरुद्धं बहु भाषते ।सर्व्वाचारविहीनश्च म्लेच्छ इत्यभिधीयते ॥”इति प्रायश्चित्ततत्त्वम् ॥ * ॥अपिच । देवयान्यां ययातेर्द्वौ पुत्त्रौ यदुः तुर्चसुश्च ।शर्म्मिष्ठायां त्रयः पुत्त्राः द्रुह्युः अनुः पुरुश्च ।तत्र यदुप्रभृतयश्चत्वारः पितुराज्ञाहेलनं कृत-वन्तः पित्रा शप्ताः । ज्येष्ठपुत्त्रं यदुं शशाप तववंशे राजा चक्रवर्त्ती मा भूदिति । तुर्व्वसु-द्रुह्य्वनून् शशाप युष्माकं वंश्या वेदवाह्या म्लेच्छाभविष्यन्ति । इति श्रीभागवतमतम् ॥ * ॥(“असृजत् पह्नवान् पुच्छात् प्रस्रावाद्द्राविडान्शकान् ।योनिदेशाच्च यवनान् शकृतः शवरान् बहून् ॥मूत्रतश्चासृजत् काञ्चीञ्छरभांश्चैव पार्श्वतःपौण्ड्रान् किरातान् यवनान् सिंहलान् वर्व्वरान्खशान् ॥चियुकांश्च पुलिन्दांश्च चीनान् हूनान् सके-रलान् ।ससर्ज्ज फेनतः सा गौर्म्लेच्छान् बहुविधानपि ॥”सा वशिष्ठस्य धेनुः । इति महाभारते । १ । १७६ ।३५ -- ३७ ॥) अन्यच्च । “शकजवनकाम्बोज-पारदपह्नवा हन्यमानास्तत्कुलगुरुं वशिष्ठंशरणं ययुः । अथैतान् वशिष्ठो जीवन्मृतकान्कृत्वा सगरमाह । वत्स वत्सालमेभिर्जीवन्मृत-कैरनुसृतैः । एते च मयैव त्वत्प्रतिज्ञापालनायनिजधर्म्मद्बिजसङ्गपरित्यागं कारिताः । सतथेति तद्गुरुवचनमभिनन्द्य तेषां वेशान्य-त्वमकारयत् । जवनान्मुण्डितशिरसोऽर्द्धमुण्डान्शकान् प्रलम्बकेशान् पारदान् पह्नवांश्च श्मश्रु-धरान्निःस्वाध्यायवषट्कारानेतानन्यांश्च क्षत्त्रि-यांश्चकार । ते चात्मधर्म्मपरित्यागाद्ब्राह्मणैश्चपरित्यक्ता म्लेच्छतां ययुः ।” इति विष्णुपुराणे । ४ ।३ । १८ -- २१ ॥ * ॥ प्रकारान्तरेण तस्योत्-पत्तिर्यया, --सूत उवाच ।“वंशे स्वायम्भुवस्यासीदङ्गो नाम प्रजापतिः ।मृत्योस्तु दुहिता तेन परिणीतातिदुर्मुखी ॥सुतीर्था नाम तस्यास्तु वेनो नाम सुतःपुरा ।अधर्म्मंनिरतः कामी बलवान् वसुधाधिपः ।लोकेऽप्यधर्म्मकृज्जातः परभार्य्यापहारकः ॥धर्म्मचारप्रसिद्ध्यर्थं जगतोऽस्य महर्षिभिः ।अनुनीतोऽपि न ददावनुक्षां स यदा ततः ॥शापेन मारयित्वैनमराजकभयार्द्दिताः ।ममन्थुर्ब्राह्मणास्तस्य बलाद्देहमकल्भषाः ॥तत्कायान्मथ्यमानात्तु निपेतुर्म्लेच्छजातयः ।शरीरे मातुरंशेन कृष्णाञ्जनसमप्रभाः ॥”इति मत्स्यपुराणे । १० । ३ -- ८ ॥ * ॥म्लेच्छभाषाभ्यासनिषेधो यथा, --“न सातयेदिष्टकाभिः फलानि वै फलेन तु ।न म्लेच्छभाषां शिक्षेत नाकर्षेच्च पदासनम् ॥”इति कौर्म्म्ये उपविभागे १५ अध्यायः ॥ * ॥तस्य मध्यमा तामसी गतिर्यथा, मानवे ।१२ । ४३ ।“हस्तिनश्च तुरङ्गाश्च शूद्रा म्लेच्छाश्च गर्हिताः ।सिंहा व्याघ्रा वराहाश्च मध्यमा तामसीगतिः ॥”(मन्त्रणाकाले म्लेच्छापसारणमुक्तं यथा, मनु-संहितायाम् । ७ । १४९ ।“जडमूकान्धवधिरांस्तैर्य्यग्योनान् वयोऽति-गान् ।स्त्रीम्लेच्छव्याधितव्यङ्गान् मन्त्रकालेऽपसार-येत् ॥”“अथवा एवंविधा मन्त्रिणो न कर्त्तव्याः । बुद्धि-विभ्रमसम्भवात् ।” इति तद्भाष्ये मेधातिथिः ॥म्लेच्छानां पशुधर्म्मित्वम् । यथा, महाभारते । १ ।८४ । १५ ।“गुरुदारप्रसक्तेषु तिर्य्यग्योनिगतेषु च ।पशुधर्म्मिषु पापेषु म्लेच्छेषु त्वं भविष्यसि ॥”)

म्लेच्छकन्दः, पुं, (म्लेच्छप्रियः कन्द इति मध्यपदलोपी कर्म्मधारयः ।) लशुनम् । इति राज-निर्घण्टः ॥ (तस्य पर्य्यायो यथा, --“लशुनस्तु रसोनः स्यादुग्रगन्धो महौषधम् ।अरिष्टो म्लेच्छकन्दश्च पवनेष्टो रसोनकः ॥”इति भावप्रकाशस्य पूर्ब्बखण्डे प्रथमे भागे ॥)म्लेच्छजातिः, स्त्री, (म्लेच्छस्य जातिरिति षष्ठी-तत्पुरुषः म्लेच्छरूपा जातिरिति कर्म्मधारयोवा ।) गोमांसखादकबहुविरुद्धभाषकसर्व्वा-चारविहीनवर्णः । यथा, --“गोमांसखादको यस्तु विरुद्धं बहु भाषते ।सर्व्वाचारविहीनश्च म्लेच्छ इत्यभिधीयते ॥”इति प्रायश्चित्ततत्त्वधृतबौधायनवचनम् ॥अपि च ।“भेदाः किरातशवरपुलिन्दा म्लेच्छजातयः ॥”इत्यमरः । २ । ४० । २० ॥अन्यच्च ।“पौण्ड्रकाश्चौड्रद्रविडाः काम्बोजा शवनाःशकाः ।पारदाः पह्नवाश्चीनाः किराताः दरदाःखशाः ॥मुखबाहूरुपज्जानां या लोके जातयो बहिः ।म्लेच्छवाचश्चार्य्यवाचः सर्व्वे ते दस्यवः स्मृताः ॥”इति मानवे १० अध्यायः ॥म्लेच्छदेशः, पुं, (म्लेच्छानां देशः म्लेच्छप्रधानोदेशो वा ।) चातुर्व्वर्ण्यव्यवस्थादिरहित-स्थानम् । तत्पर्य्यायः । प्रत्यन्तः २ । इत्यमरः ।२ । १ । ७ ॥ भारतवर्षस्यान्तं प्रतिगःप्रत्यन्तः । म्लेच्छति शिष्टाचारहीनो भवत्यत्रम्लेच्छः अल् । स चासौ देशश्चेति म्लेच्छदेशः ।किंवा म्लेच्छयन्ति असंस्कृतं वदन्ति शिष्टा-चारहीना भवन्तीति वा पचाद्यचि म्लेच्छानीचजातयः तेषां देशो म्लेच्छदेशः । भारतवर्ष-स्यान्तः शिष्टाचाररहितः कामरूपवङ्गादिः ।उक्तञ्च ।चातुर्व्वर्ण्यव्यवस्थानं यस्मिन् देशे न विद्यते ।म्लेच्छदेशः स विज्ञेय आर्य्यावर्त्तस्ततः पर-मिति ॥”इति भरतः ॥(अपि च, मनुः । २ । २३ ।“कृष्णसारस्तु चरति मृगो यत्र स्वभावतः ।स ज्ञेयो यज्ञियो देशो म्लेच्छदेशस्ततःपरम् ॥”)म्लेच्छभोजनं, क्ली, (भुज्यते यदिति । भुज् + कर्म्मणिल्युट् । ततो म्लेच्छानां भोजनम् ।) यावकः ।इति शब्दरत्नावली ॥म्लेच्छभोजनः, पुं, (भुज्यतेऽसौ इति । भुज् +ल्युट् । म्लेच्छानां भोजनः । (गोधूमः । इतित्रिकाण्डशेषः ॥म्लेच्छमण्डलं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छानां मण्डलं समूहोऽत्र ।)म्लेच्छदेशः । इति हेमचन्द्रः ॥म्लेच्छमुखं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छे म्लेच्छदेशे मुखमुत्पत्ति-रस्य । इत्यमरटीकायां रघुनाथः ।) ताम्रम् ।इत्यमरः । २ । ९ । ९७ ॥ (तथास्य पर्य्यायः ।“ताम्रमौदुम्बरं शुल्वमुदुम्बरमपि स्मृतम् ।रविप्रियं म्लेच्छमुखं सूर्य्यपर्य्यायनामकम् ॥”इति भावप्रकाशस्य पूर्ब्बखण्डे प्रथमे भागे ॥“ताम्रमौडुम्बरं शूल्वं विद्यात् च्छमुख-न्तथा ॥”इति गारुडे २०८ अध्याये ॥)म्लेच्छाशः, पुं, (म्लेच्छैरश्यते इति । अश् + कर्म्मणि+ घञ् ।) म्लेच्छभोजनः । गोधूमः । इतिकेचित् ॥म्लेच्छास्यं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छे म्लेच्छदेशे आस्यमुत्पत्ति-रस्य ।) ताम्रम् । इति हारावली ॥म्लेच्छितं, क्ली, (म्लेछ् देश्योक्तौ + क्तः ।) म्लेच्छ-भाषा । अपशब्दः । तत्पर्य्यायः । परभाषा २ ।इति हारावली ॥म्लेट, ऋ उन्मादे । इति कविकल्वद्रुमः ॥ (भ्वा०-पर०-अक०-सेट् ।) ऋ, अमिम्लेटत् । म्लेटतिलोकः उन्माद्यतीत्यर्थः । इति दुर्गादासः ॥म्लेड, ऋ उन्मादे । इति कविकल्पद्रुमः ॥ (भ्वा०-पर०-अक०-सेट् ।) ऋ, अमिम्लेडत् । म्लेडति ।उन्माद्यतीत्यर्थः । इति दुर्गादासः ॥

https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/शब्दकल्पद्रुमः/

मुख 'copper'; 'the edge (of an axe) '

म्लेच्छ n. copper (Skt.) Milakkhu [the Prk. form (A -- Māgadhī, cp. Pischel, Prk. Gr. 105, 233) for P. milakkha] a non -- Aryan D iii.264; Th 1, 965 (˚rajana "of foreign dye" trsl.; Kern, Toev. s. v. translates "vermiljoen kleurig"). As milakkhuka at Vin iii.28, where Bdhgh expls by "Andha -- Damil'ādi." (Pali)

Milakkha [cp. Ved. Sk. mleccha barbarian, root mlecch, onomat. after the strange sounds of a foreign tongue, cp. babbhara & mammana] a barbarian, foreigner, outcaste, hillman S v.466; J vi.207; DA i.176; SnA 236 (˚mahātissa -- thera Np.), 397 (˚bhāsā foreign dialect). The word occurs also in form milakkhu (q. v.).

म्लेच्छ a person who lives by agriculture or by making weapons; m. a foreigner , barbarian , non-Aryan , man of an outcast race , any person who does not speak Sanskrit and does not conform to the usual Hindu institutions(शतपथ-ब्राह्मण); ignorance of Sanskrit , barbarism (न्यायमाला-विस्तर, Sayana) (Monier-Williams)

म्लेच्छः mlecchaḥ [म्लेच्छ्-घञ्] 1 A barbarian, a non-Āryan (one not speaking the Sanskṛit language, or not conforming to Hindu or Āryan institutions), a foreigner in general; ग्राह्या म्लेच्छप्रसिद्धिस्तु विरोधादर्शने सति J. N. V.; म्लेच्छान् मूर्छयते; or म्लेच्छनिवहनिधने कलयसि करवालम् Gīt.1. -2 An outcast, a very low man; (Baudhāyana thus defines the word:-- गोमांसखादको यस्तु विरुद्धं बहु भाषते । सर्वा- चारविहीनश्च म्लेच्छ इत्यभिधीयते ॥). -3 A sinner, wicked person. -4 Foreign or barbarous speech. -च्छम् 1 Copper. -2 Vermilion. -Comp. -आख्यम् copper. -आशः wheat. -आस्यम्, -मुखम् copper. -कन्दः garlic. -जातिः f. a savage or barbarian race, a mountaineer; पुलिन्दा नाहला निष्ट्याः शबरा वरुटा भटाः । माला भिल्लाः किराताश्च सर्वेऽपि म्लेच्छजातयः ॥ Abh. Chin.934. -देशः, -मण्डलम् a country inhabited by non-Āryans or barbarians, a foreign or barbarous country; कृष्णसारस्तु चरति मृगो यत्र स्वभावतः । स ज्ञेयो यज्ञियो देशो म्लेच्छदेशस्त्वतः परः ॥ Ms.2.23. -द्विष्टः bdellium. -भाषा a foreign language. -भोजनः wheat. (-नम्) barley. -वाच् a. speaking a barbarous or foreign language; म्लेच्छवाचश्चार्यवाचः सर्वे ते दस्यवः स्मृताः Ms.10.45.

म्लेच्छनम् mlecchanam 1 Speaking indistinctly or confusedly. -2 Speaking in a barbarous tongue.

म्लेच्छित mlecchita p. p. Spoken indistinctly or barbarously. -तम् 1 A foreign tongue. -2 An ungrammatical word or speech.

म्लेच्छितकम् mlecchitakam Foreign or barbarous speech. म्लेट् mleṭ, म्लेड् mleḍ (म्लेट-ड-ति) To be mad.

म्लिष्ट mliṣṭa a. 1 Spoken indistinctly (as by barbarians), indistinct; P.VII.2.18; म्लिष्टमस्फुटम् Abh. Chin.266. -2 Barbarous. -3 Withered, faded. -ष्टम् 1 An indistinct or barbarous speech. -2 A foreign language.

म्लुच् mluc, म्लुञ्च् mluñc 1 See म्रच्, म्रुञ्च्. -2 To set; म्लोचन्ति ह्यन्या देवता न वायुः Bṛi. Up.1.5.22.

म्लेच्छ् mlecch, म्लेछ् mlech 1 P., 10 U. (म्लेच्छति, म्लेच्छयति-ते, म्लिष्ट, म्लेच्छित) 1 To speak confusedly, indistinctly, or barbarously. -2 To speak distinctly (व्यक्तायां वाचि); L. D. B.(Apte)

अप-शब्द m. bad or vulgar speech; any form of language not Sanskrit; ungrammatical language; (अप-भ्रंश.); ungrammatical language (compared to a deer as grammar to a lion (Monier-Williams)

These ancient encyclopaedic texts शब्दकल्पद्रुमः, वाचस्पत्यम् also validate mleccha bhāṣā as the spoken language of Bhāratam janam. Mleccha is cognate Meluhha documented in cuneiform texts of Ancient Near East, see for example the Shu-ilishu cylinder seal.

आयस त्रि० अयसो विकारः अण् स्त्रियां ङीप् । लौहमये ।“शक्तिञ्चोभयतस्तीक्ष्णामायसं दण्डमेव वा” “पुमांसंदाहयेत् पापं शयने तप्तआयसे” इति च मनुः । “स चकर्ष-परस्मात् तत् अयस्कान्त इवायसम्” रघुः । “मूढ़बुद्धिमिवा-त्मानं हैमीभूतमिवायसम्” कुमा० । २ लौहमयकवचे च३ अङ्गरक्षिण्यां जालिकायां स्त्री । अयएव स्वार्थेअण् ।४ लौहे । ततः विकारेमयट्लोहमये त्रि० स्त्रियां ङीप् ।

आयसीय त्रि० अयसः सन्निकृष्टदेशादि० कुशा० छण् ।लौहसन्निकृष्टदेशादौ । (वाचस्पत्यम्)

म्लेच्छ अपशब्दे वा चु० उभ० पक्षे भ्वा० पर० अक०सेट् । म्लेच्छयति ते म्लेच्छति अमम्लेच्छत् त अम्लेच्छीत्

म्लेच्छ पु० म्लेच्छ--घञ् । १ अपशब्दे “म्लेच्छोह वा नामयदप्रशब्द” इति श्रुतिः । कर्त्तरि अच् । २ पामरजातौ,३ नीचजातौ च पुंस्त्री० स्त्रियां ङीष् “गोमांसखादकोयस्तु विरुद्धं बहु भाषते । सर्चाचारविहीनश्च म्लेच्छइत्यभिधीयते” बौधायनः । ४ पापरते त्रि० मेदि० ।५ हिङ्गुले न० राजनि० ।

म्लेच्छकन्द पु० म्लेच्छप्रियः कन्दः शा० त० । लशुने राजनि०

म्लेच्छजाति स्त्री म्लेच्छाभिधा जातिः । गोमांसादिभक्षकेकिरातादिजातिभेदे अमरः ।

म्लेच्छदेश पु० म्लेच्छाधारो देशः । चातुर्वर्ण्याचाररहितेदेशे अमरः । “चातुर्वर्ण्यव्यवस्थानं यस्मिन् देशे नविद्यते । म्लेच्छदेशः स विज्ञेय आर्य्यावर्त्तस्ततःपरम्” ।

म्लेच्छभोजन न० म्लेच्छैर्भुज्यते भुज--कर्मणि ल्युट् ।१ यावके अन्नभेदे शब्दर० । २ गोधूमे पु० त्रिका० ।

म्लेच्छमण्डल न० ६ त० । म्लेच्छदेशे हेमच० ।

म्लेच्छमुख न० म्लेच्छानां मुखमिव रक्तत्वात् । ताम्रे अमरः ।म्लेच्छास्यमप्यत्र हारा० ।

म्लेच्छित न० म्लेच्छ--क्त । अपशब्दे असंस्कृतशब्दे हारा० ।

(वाचस्पत्यम्)

म्लेच्छित n. a foreign tongue म्लेच्छित mfn. = म्लिष्ट, Pāṇ. 7-2, 18 Sch. म्लिष्ट न० म्लेच्छ--क्त नि० ।

१ अविस्पष्टवाक्ये २ तद्वाक्ययुक्ते ३ म्लाने च त्रि० मेदि० (वाचस्पत्यम्) |

| म्लिष्ट mfn. spoken indistinctly or barbarously, Pāṇ. 7-2, 18 | | withered, faded, faint (= म्लान), L. | | म्लिष्ट n. indistinct speech, a foreign language, L. |

|

म्लेच्छन n. the act of speaking confusedly or barbarously, Dhātup. म्लेच्छ—वाच् mfn. speaking a barbarous language (i.e. not Sanskṛt ; opp. to आर्य-वाच्), Mn. x, 43

म्लेच्छ—मुख n. = म्लेच्छास्य n.‘foreigner-face’, copper (so named because the complexion of the Greek and Muhammedan invaders of India was supposed to be copper-coloured), म्लेच्छाख्य n. ‘called Mleccha’, copper,

म्लेच्छ—जाति m. a man belonging to the Mlecchas, a barbarian, savage, mountaineer (as a Kirāta, Śabara or Pulinda), MBh. म्लेच्छ—देश m. a foreign or barbarous country, Hariv.

म्लेच्छ—मण्डल n. the country of the Mlecchas or barbarians or robbers

| म्लेच्छाश m. = म्लेच्छ-भोजन n. ‘food of b°’, wheat, L. (also °ज्य) |

| म्लेच्छ—भोजन n. = यावक, half-ripe barley, L. |

Whitney Roots links: म्लेछ् & Westergaard Dhatupatha links: 7.25, 32.120

म्लेछ् (= √म्लिछ्) cl. 1. P. (Dhātup. vii, 25 ) म्लेच्छति (Gr. also pf. मिम्लेच्छ fut. म्लेच्छिता &c.; Ved. inf. म्लेच्छितवै, Pat. ),to speak indistinctly (like a foreigner or barbarian who does not speak Sanskṛt), ŚBr. ; MBh. :Caus. or cl. 10. P. म्लेच्छयति id., Dhātup. xxxii, 120. म्लेच्छ m. a foreigner, barbarian, non-Aryan, man of an outcast race, any person who does not speak Sanskṛt and does not conform to the usual Hindū institutions, ŚBr. &c. &c. (f(ई). ) [ID=168910] |

| a person who lives by agriculture or by making weapons, L. [ID=168911] |

| a wicked or bad man, sinner, L.; |

| ignorance of Sanskṛt, barbarism, Nyāyam. Sch. |

| म्लेच्छ n. copper, L. |

| vermilion, L. (Monier-Williams) |

म्लेच्छः mlecchaḥ [म्लेच्छ्-घञ्] 1 A barbarian, a non-Āryan (one not speaking the Sanskṛit language, or not conforming to Hindu or Āryan institutions), a foreigner in general; ग्राह्या म्लेच्छप्रसिद्धिस्तु विरोधादर्शने सति J. N. V.; म्लेच्छान् मूर्छयते; or म्लेच्छनिवहनिधने कलयसि करवालम् Gīt.1. -2 An outcast, a very low man; (Baudhāyana thus defines the word:-- गोमांसखादको यस्तु विरुद्धं बहु भाषते । सर्वा- चारविहीनश्च म्लेच्छ इत्यभिधीयते ॥). -3 A sinner, wicked person. -4 Foreign or barbarous speech. -च्छम् 1 Copper. -2 Vermilion. -Comp. -आख्यम् copper. -आशः wheat. -आस्यम्, -मुखम् copper. -कन्दः garlic. -जातिः f. a savage or barbarian race, a mountaineer; पुलिन्दा नाहला निष्ट्याः शबरा वरुटा भटाः । माला भिल्लाः किराताश्च सर्वेऽपि म्लेच्छजातयः ॥ Abh. Chin.934. -देशः, -मण्डलम् a country inhabited by non-Āryans or barbarians, a foreign or barbarous country; कृष्णसारस्तु चरति मृगो यत्र स्वभावतः । स ज्ञेयो यज्ञियो देशो म्लेच्छदेशस्त्वतः परः ॥ Ms.2.23. -द्विष्टः bdellium. -भाषा a foreign language. -भोजनः wheat. (-नम्) barley. -वाच् a. speaking a barbarous or foreign language; म्लेच्छवाचश्चार्यवाचः सर्वे ते दस्यवः स्मृताः Ms.10.45.

म्लेच्छनम् mlecchanam 1 Speaking indistinctly or confusedly. -2 Speaking in a barbarous tongue.

म्लेच्छित mlecchita p. p. Spoken indistinctly or barbarously. -तम् 1 A foreign tongue. -2 An ungrammatical word or speech.

म्लेच्छितकम् mlecchitakam Foreign or barbarous speech.(Apte)

mlecchāśya = production of āyasam or metal or copper (āyasamutpatirasya)

म्लेच्छमण्डलं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छानां मण्डलं समूहोऽत्र ।)म्लेच्छदेशः । इति हेमचन्द्रः ॥

म्लेच्छमुखं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छे म्लेच्छदेशे मुखमुत्पत्ति-रस्य । इत्यमरटीकायां रघुनाथः ।) ताम्रम् ।इत्यमरः । २ । ९ । ९७ ॥ (तथास्य पर्य्यायः ।“ताम्रमौदुम्बरं शुल्वमुदुम्बरमपि स्मृतम् ।रविप्रियं म्लेच्छमुखं सूर्य्यपर्य्यायनामकम् ॥”इति भावप्रकाशस्य पूर्ब्बखण्डे प्रथमे भागे ॥“ताम्रमौडुम्बरं शूल्वं विद्यात् म्लेच्छमुख-न्तथा ॥”इति गारुडे २०८ अध्याये ॥)

म्लेच्छाशः, पुं, (म्लेच्छैरश्यते इति । अश् + कर्म्मणि+ घञ् ।) म्लेच्छभोजनः । गोधूमः । इतिकेचित् ॥

म्लेच्छास्यं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छे म्लेच्छदेशे आस्यमुत्पत्ति-रस्य ।) ताम्रम् । इति हारावली ॥

म्लेच्छितं, क्ली, (म्लेछ् देश्योक्तौ + क्तः ।) म्लेच्छ-भाषा । अपशब्दः । तत्पर्य्यायः । परभाषा २ ।इति हारावली ॥

म्लेच्छभोजनः, पुं, (भुज्यतेऽसौ इति । भुज् +ल्युट् । म्लेच्छानां भोजनः । (गोधूमः । इतित्रिकाण्डशेषः ॥

चषालः, पुं, (चष्यते वध्यतेऽस्मिन् । चष + “सानसि-वर्णसीति ।” उणां । ४ । १०७ । इति आलप्रत्ययेन निपातनात् साधुः ।) यूपकटकः । इत्य-मरः । २ । ७ । १८ ॥ यज्ञसमाप्तिसूचकं पशु-बन्धनाद्यर्थं यज्ञभूमौ यत् काष्ठमारोप्यते स यूपःतस्य शिरसि वलयाकृतिर्डमरुकाकृतिर्व्वा यःकाष्ठविकारः सः । यूपमूलेविहितलोहवलयश्च ।इति केचित् । इति भरतः ॥ मधुस्थानम् । इतिसंक्षिप्तसारे उणादिवृत्तिः ॥

यूपकटकः, पुं, (यूपस्य कटक इव ।) यज्ञसमाप्ति-सूचकं पशुबन्धाद्यर्थं यज्ञभूमौ यत् काष्ठमारो-प्यते स यूपः तस्य शिरसि वलयाकृतिर्डमरुका-कृतिर्वा यः काष्ठविकारः सः । यूपमूले निहित-लोहबलय इति केचित् । इति भरतः ॥ तत्-पर्य्यायः । चषालः २ । इत्यमरः । २ । ७ । १८ ॥

- https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/शब्दकल्पद्रुमः

Vātsyāyana notes about himself after writing down Vidyāsamuddeśa:

| 'After reading and considering the works of Babhravya and other ancient authors, and thinking over the meaning of the rules given by them, this treatise was composed, according to the precepts of the Holy Writ, for the benefit of the world, by Vatsyayana, while leading the life of a religious student at Benares, and wholly engaged in the contemplation of the Deity. This work is not to be used merely as an instrument for satisfying our desires. A person acquainted with the true principles of this science, who preserves his Dharma (virtue or religious merit), his Artha (worldly wealth) and his Kama (pleasure or sensual gratification), and who has regard to the customs of the people, is sure to obtain the mastery over his senses. In short, an intelligent and knowing person attending to Dharma and Artha and also to Kama, without becoming the slave of his passions, will obtain success in everything that he may do.' |

Vidyāsamuddeśa includes three of the 64 arts related to language communication: dēśá bhāṣā jnānam, akṣára muṣṭíka kathanam, mlecchita vikalpa: expressions which can be translated as: language speech forms, messaging by hand/wrist gestures, mleccha (meluhha) cipher.

Mlecchita vikalpa may be interpreted as a 'contrivance' to alternatively signify speech, i.e. 'cipher'. Such a cipher or mlecchita vikalpa is employed in Indus Script Corpora. Mlecchita has three meanings: 1. indistinct or mispronunciations in speech; 2. made by copper workers: 3. metalwork e.g mlecchāśa = mlecchabhojanam. mlecchāśya = production of āyasam or metal or copper (āyasamutpatirasya); mlecchabhohjanam means 'gōdhūma' which is the caṣāla on Yupa which signifies a Soma Yaga. āyasam means 'loha', 'metal'.Thus, mlecchāsya means 'production of metal or metalwork.

शब्दकल्पद्रुमः notes in reference to the geographical spread of mleccha speakers that they constituted the Bhāratam Janam and were all over Bhāratam. The spoken form of the language is called mleccha bhāṣā. This language or Prakritam is signified by Indus Script hieroglyphs in the Corpora.

Tracing the language roots of Bhāratam Janam on the banks of River Sarasvati system speaking a form of Proto-Prakritam a metalwork lexis emerges. This is traceable in many languages of Indian sprachbund. A unique writing system was based on Proto-Prakritam. This was called Meluhha in cuneiform texts and mlecchita vikalpa (i.e. alternative representation of mleccha) in Vātsyāyana’s treatise on Vidyāsamuddeśa (ca 6th century BCE). The principal life-activity of artisan guilds of Bhāratam Janam was metalwork creating metalcastings, experimenting with creation of various forms of ores, metals, alloys, smelters, furnaces, braziers and other tools and making metal implements. The result was a veritable revolution transiting from chalcolithic phase to metals age in urban settings. This legacy finds expression in the famed, non-rusting Delhi iron pillar which was originally from Vidisha (Besanagara, Sanchi). Archaeologically-attested presence of Bhāratam Janam dates from ca. 8th millennium BCE. The use of a writing system dates from ca. 4th millennium BCE (HARP). Rigveda. In RV 3.53.12, Rishi Visvamitra states that this mantra (brahma) shall protect the people: visvamitrasya rakshati brahmedam Bhāratam Janam. The word Bharata in the expression is derived from the metalwork lexis of Prakritam: bharata ‘bhārata ‘a factitious alloy of copper, pewter, tin’; baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin)’. Thus, the expression Bhāratam Janam can be deciphered as ‘metalcaster folk’, thus firmly establishing the identity of the people of India, that is Bharat and the spoken form of their language ca. 3500 BCE.

Decipherment of Indus Script Corpora based on an Indo-European language may lead to redefining the Proto-Indo-European studies. Baudhāyana-Śrautasūtra provides indications of movements of Bhāratam Janam out of Sarasvati river valley eastwards towards Kashi and westwards towards Sumer/Mesopotamia.

ऋग्वेदः - मण्डल १०सूक्तं१०.९०नारायणः।दे. पुरुषः ।अनुष्टुप्, १६ त्रिष्टुप्

यज्ञेनयज्ञमयजन्तदेवास्तानिधर्माणिप्रथमान्यासन्।

तेहनाकंमहिमानःसचन्तयत्रपूर्वेसाध्याःसन्तिदेवाः॥१६॥

सायणभाष्यम् : पूर्वप्रपञ्चेनोक्तमर्थंसंक्षिप्यात्रदर्शयति।"देवाःप्रजापतिप्राणरूपाः"यज्ञेनयथोक्तेनमानसेनसंकल्पेनयज्ञंयथोक्तयज्ञस्वरूपंप्रजापतिम्"अयजन्तपूजितवन्तः।तस्मात्पूजनात“तानिप्रसिद्धानि“धर्माणिजगद्रूपविकाराणांधारकाणि"प्रथमानिमुख्यानिआसन्।एतावतासृष्टिप्रतिपादकसूक्तभागार्थःसंगृहीतः।अथोपासनतत्फलानुवादकभागार्थःसंगृह्यते।"यत्रयस्मिन्विराटप्राप्तिरूपेनाके"पूर्वे"साध्याःपुरातनाविराडुपास्तिसाधकाः“देवाः"सन्तितिष्ठन्तितत्"नाकंविराट्प्राप्तिरूपंस्वर्ग“ते“महिमानःतदुपासकामहात्मानः"सचन्तसमवयन्तिप्राप्नुवन्ति॥

David Kahn, 1996, The Code Breakers, Simon and Schuster

![]()

[quote]The magnificent, unrivaled history of codes and ciphers -- how they're made, how they're broken, and the many and fascinating roles they've played since the dawn of civilization in war, business, diplomacy, and espionage -- updated with a new chapter on computer cryptography and the Ultra secret.

Man has created codes to keep secrets and has broken codes to learn those secrets since the time of the Pharaohs. For 4,000 years, fierce battles have been waged between codemakers and codebreakers, and the story of these battles is civilization's secret history, the hidden account of how wars were won and lost, diplomatic intrigues foiled, business secrets stolen, governments ruined, computers hacked. From the XYZ Affair to the Dreyfus Affair, from the Gallic War to the Persian Gulf, from Druidic runes and the kaballah to outer space, from the Zimmermann telegram to Enigma to the Manhattan Project, codebreaking has shaped the course of human events to an extent beyond any easy reckoning. Once a government monopoly, cryptology today touches everybody. It secures the Internet, keeps e-mail private, maintains the integrity of cash machine transactions, and scrambles TV signals on unpaid-for channels. David Kahn's The Codebreakers takes the measure of what codes and codebreaking have meant in human history in a single comprehensive account, astonishing in its scope and enthralling in its execution. Hailed upon first publication as a book likely to become the definitive work of its kind, The Codebreakers has more than lived up to that prediction: it remains unsurpassed. With a brilliant new chapter that makes use of previously classified documents to bring the book thoroughly up to date, and to explore the myriad ways computer codes and their hackers are changing all of our lives, The Codebreakers is the skeleton key to a thousand thrilling true stories of intrigue, mystery, and adventure. It is a masterpiece of the historian's art.[unquote]Richard Burton, Bhagavanlal Indrajit, Shivaram Parashuram Bhide, 2009, The Kama Sutra of Vātsyāyana Translated From The Sanscrit In Seven Parts With Preface,Introduction and Concluding Remarks, Reprint:Cosmopoli: MDCCCLXXXIII: for the Kama Shastra Society of London and Benares, and for private circulation only.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/27827/27827-h/27827-h.htm

Many versions of 64 arts listed by Vātsyāyana exist. One such version is excerpted below. In the list of arts mlecchita vikalpa is listed as Item 43. This signified Mleccha cipher writing, Indus Script.

CHAPTER III.

ON THE ARTS AND SCIENCES TO BE STUDIED.

The following are the arts to be studied:

1. Singing.

2. Playing on musical instruments.

3. Dancing.

4. Union of dancing, singing, and playing instrumental music.

5. Writing and drawing.

6. Tattooing.

7. Arraying and adorning an idol with rice and flowers.

8. Spreading and arraying beds or couches of flowers, or flowers upon the ground.

9. Colouring the teeth, garments, hair, nails, and bodies, i.e., staining, dyeing, colouring and painting the same.

10. Fixing stained glass into a floor.

11. The art of making beds, and spreading out carpets and cushions for reclining.

12. Playing on musical glasses filled with water.

13. Storing and accumulating water in aqueducts, cisterns and reservoirs.

14. Picture making, trimming and decorating.

15. Stringing of rosaries, necklaces, garlands and wreaths.

16. Binding of turbans and chaplets, and making crests and top-knots of flowers.

17. Scenic representations. Stage playing.

18. Art of making ear ornaments.

19. Art of preparing perfumes and odours.

20. Proper disposition of jewels and decorations, and adornment in dress.

21. Magic or sorcery.

22. Quickness of hand or manual skill.

23. Culinary art, i.e., cooking and cookery.

24. Making lemonades, sherbets, acidulated drinks, and spirituous extracts with proper flavour and colour.

25. Tailor's work and sewing.

26. Making parrots, flowers, tufts, tassels, bunches, bosses, knobs, &c., out of yarn or thread.

27. Solution of riddles, enigmas, covert speeches, verbal puzzles and enigmatical questions.

28. A game, which consisted in repeating verses, and as one person finished, another person had to commence at once, repeating another verse, beginning with the same letter with which the last speaker's verse ended, whoever failed to repeat was considered to have lost, and to be subject to pay a forfeit or stake of some kind.

29. The art of mimicry or imitation.

30. Reading, including chanting and intoning.

31. Study of sentences difficult to pronounce. It is played as a game chiefly by women and children, and consists of a difficult sentence being given, and when repeated quickly, the words are often transposed or badly pronounced.

32. Practice with sword, single stick, quarter staff, and bow and arrow.

33. Drawing inferences, reasoning or inferring.

34. Carpentry, or the work of a carpenter.

35. Architecture, or the art of building.

36. Knowledge about gold and silver coins, and jewels and gems.

37. Chemistry and mineralogy.

38. Colouring jewels, gems and beads.

39. Knowledge of mines and quarries.

40. Gardening; knowledge of treating the diseases of trees and plants, of nourishing them, and determining their ages.

41. Art of cock fighting, quail fighting and ram fighting.

42. Art of teaching parrots and starlings to speak.

43. Art of applying perfumed ointments to the body, and of dressing the hair with unguents and perfumes and braiding it.

44. The art of understanding writing in cypher, and the writing of words in a peculiar way.

45. The art of speaking by changing the forms of words. It is of various kinds. Some speak by changing the beginning and end of words, others by adding unnecessary letters between every syllable of a word, and so on.

46. Knowledge of language and of the vernacular dialects.

47. Art of making flower carriages.

48. Art of framing mystical diagrams, of addressing spells and charms, and binding armlets.

49. Mental exercises, such as completing stanzas or verses on receiving a part of them; or supplying one, two or three lines when the remaining lines are given indiscriminately from different verses, so as to make the whole an entire verse with regard to its meaning; or arranging the words of a verse written irregularly by separating the vowels from the consonants, or leaving them out altogether; or putting into verse or prose sentences represented by signs or symbols. There are many other such exercises.

50. Composing poems.

51. Knowledge of dictionaries and vocabularies.

52. Knowledge of ways of changing and disguising the appearance of persons.

53. Knowledge of the art of changing the appearance of things, such as making cotton to appear as silk, coarse and common things to appear as fine and good.

54. Various ways of gambling.

55. Art of obtaining possession of the property of others by means of muntras or incantations.

56. Skill in youthful sports.

57. Knowledge of the rules of society, and of how to pay respects and compliments to others.

58. Knowledge of the art of war, of arms, of armies, &c.

59. Knowledge of gymnastics.

60. Art of knowing the character of a man from his features.

61. Knowledge of scanning or constructing verses.

62. Arithmetical recreations.

63. Making artificial flowers.

64. Making figures and images in clay.

https://tinyurl.com/y85lflto

This is an addendum to:

Like the Dholavira sign board, the anthropormorph if displayed on the gateway of workers' quarters or locality is a proclamation symbol of मांझीथा Majhīthā sadya 'member of mã̄jhī boatpeople assembly (community)'. The pictrographs of young bull, ram's horns, spread legs, boar signify:

goldsmith, iron metalworker, merchant, steersman.

[Details: कोंद kōnda ‘engraver' (one-horned young bull hieroglyph); kundana 'fine gold' (Kannada) PLUS bāṛaï 'carpenter' bari barea 'merchant' (boar hieroglyph) PLUS karṇaka कर्णक steersman ('spread legs'); meḍho 'ram' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron'] Brāhmī inscription on Indus Script anthropomorph reads (on the assumption that Line 3 is an inscription with Indus Script hypertexts):

śam ña ga kī ma jhi tha mū̃h baṭa baran khāṇḍā

samjñā 'symbol, sign'

kī ma jhi tha 'of Majhitha'

Sha (?) Da Ya शद sad-a 'produce (of a country)'.-shad-ya, m. one who takes part in an assembly, spectator

Meaning:

Line 1 (Brāhmī syllables): samjñā 'symbol, sign' (of)

Line 2 (Brāhmī syllables): kī ma jhi tha 'of Majhitha locality or mã̄jhī boatpeople community or workers in textile dyeing: majīṭh 'madder'. The reference may also be to mañjāḍi (Kannada) 'Adenanthera seed weighing two kuṉṟi-mani, used by goldsmiths as a weight'.

Line 3 (Indus Script hieroglyphs): baṭa 'iron' bharat 'mixed alloys' (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) mū̃h 'ingots' khāṇḍā 'equipments'.

Alternative reading of Line 3 (if read as Brāhmī syllables): Sha (?) Da Ya शद sad-a signifies: 'produce (of a country' or -shad-ya, m. one who takes part in an assembly, spectator.

Thus,an alternative reading is that the threelines may signify symbol of मांझीथा Majhīthā sadya 'assembly participant' or member of mã̄jhī boatpeople assembly (community).

Thus, this is a proclamation, a hoarding which signifies the Majitha locality (working in) iron, mixed alloys (bharat) ingots and equipments. Alternative reding is: symbol (of) produce of Majhitha locality or community

Alternatives:

A cognate word signifies boatman: *majjhika ʻ boatman ʼ. [Cf. maṅga -- ?] N. mājhi, mã̄jhi ʻ boatman ʼ; A. māzi ʻ steersman ʼ, B. māji; Or. mājhi ʻ steersman ʼ, majhiā ʻ boatman ʼ, Bi. Mth. H. mã̄jhī m.(CDIAL 9714).மஞ்சி2 mañci, n. 1. cf. mañca. [M. mañji.] Cargo boat with a raised platform; படகு. Thus, a majhitha artisan is also a boatman.

A cognate word is: mañjiṣṭhā f. ʻ the Indian madder (Rubia cordifolia and its dye) ʼ Kauś. [mañjiṣṭha -- ] Pa. mañjeṭṭhī -- f. ʻ madder ʼ, Pk. maṁjiṭṭhā -- f.; K. mazēṭh, dat. ˚ṭhi f. ʻ madder plant and dye (R. cordifolia or its substitute Geranium nepalense) ʼ; S. mañuṭha, maĩṭha f. ʻ madder ʼ; P. majīṭ(h), mãj˚ f. ʻ root of R. cordifolia ʼ; N. majiṭho ʻ R. cordifolia ʼ, A. mezāṭhi, maz˚, OAw. maṁjīṭha f.; H. mãjīṭ(h), maj˚ f. ʻ madder ʼ, G. majīṭh f., Ko. mañjūṭi; -- Si. madaṭa ʻ a small red berry ʼ, madaṭiya ʻ the tree with red wood Adenanthera pavonina (Leguminosae) ʼ; Md. madoři ʻ a weight ʼ.māñjiṣṭha -- .Addenda: mañjiṣṭhā -- [Cf. Drav. Kan. mañcaṭige, mañjāḍi, mañjeṭṭi S. M. Katre]: S.kcch. majīṭh f. ʻ madder ʼ.(CDIAL 9718) மஞ்சிட்டி mañciṭṭi, n. < mañjiṣṭhā. 1. Munjeet, Indian madder, Rubia cordifolia; நீர்ப்பூடுவகை. (I. P.) 2. Arnotto. See சாப்பிரா. (L.) 3. Chayroot for dyeing; சாயவேர். (L.) மஞ்சாடி mañcāṭi, n. [T. manḍzādi, K. mañjāḍi.] 1. Red-wood, m. tr., Adenanthera paronina; மரவகை. 2. Adenanthera seed weighing two kuṉṟi-mani, used by goldsmiths as a weight; இரண்டு குன்றிமணிகளின் எடை கொண்ட மஞ்சாடிவித்து. (S. I. I. i, 114, 116.)

The wor manjhitha may be derived from the root: मञ्ज् mañj मञ्ज् 1 U. (मञ्जयति-ते) 1 To clean, purify, wipe off. Thus, the reference is to a locality of artisans engaged in purifying metals and alloys. Such purifiers or assayers of metal are also referred to as पोतदार pōtadāra m ( P) An officer under the native governments. His business was to assay all money paid into the treasury. He was also the village-silversmith. (Marathi)

The reading of the Munjals is reproduced below:

Sa Thi Ga

Ki Ma Jhi Tha

Sha (?) Da Ya

Subhash Kak reads the letters as:

śam ña ga

kī ma jhi tha

ta ḍa ya

that is

शं ञ ग

की म झि थ

त ड य

शं झ ग śam ña ga

की म झी थ kī ma jhi tha

Figure 1. The copper object and the text together with the reading in Munjal, S.K. and Munjal, A. (2007). Composite anthropomorphic figure from Haryana: a solitary example of copper hoard. Prāgdhārā (Number 17).

![]() Third line of Brāhmī inscription:

Third line of Brāhmī inscription: ![]() Line 3

Line 3

त ड य ta ḍa ya (This third line has to be read as Indus Script hieroglyphs/hypertexts and NOT as Brami syllables). Subhash Kak suggests that this third line taḍaya may signify"punishment to inimical forces."

Third line read as Indus Script hieroglyphs/hypertexts is deciphered as:

![]() mū̃h baṭa 'iron ingot',

mū̃h baṭa 'iron ingot',![]() baran, bharat 'mixed copper, zinc, tin alloy metal' and

baran, bharat 'mixed copper, zinc, tin alloy metal' and![]() khāṇḍā metalware.

khāṇḍā metalware.

Anthropomorph found in a foundation of a house in a village called Kheri Gujar in Sonepat District in Haryana. The house itself rests on an ancient mound that has been variously dated to Late Harappan. The object is about 2 kg. and has dimensions of 30×28.5 cm.![]()

It is possible that Line 3 is a composition of Indus Script Hieroglyphs (and NOT Brāhmī syllables). Framed on this hypothesis, the message of Line 3 signifies:

![]()

mū̃h baṭa 'iron ingot',

baran, bharat 'mixed copper, zinc, tin alloy metal' and

khāṇḍā metalware.

Hypertext of Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUSSign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron'

Sign 48 is a 'backbone, spine' hieroglyph: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat 'mixed alloys' (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin)

Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023). ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) Thus ciphertext kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ is rebus hypertext kāṇḍa 'excellent iron', khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

saṁjñāˊ f. ʻ agreement, understanding ʼ ŚBr., ʻ sign ʼ MBh. [√jñā]Pa. saññā -- f. ʻ sense, sign ʼ, Pk. saṁṇā -- f.; S. sañaṇu ʻ to point out ʼ; WPah.jaun. sān ʻ sign ʼ, Ku. sān f., N. sān; B. sān ʻ understanding, feeling, gesture ʼ; H. sān f. ʻ sign, token, trace ʼ; G. sān f. ʻ sense, understanding, sign, hint ʼ; M. sã̄j̈ f. ʻ rule to make an offering to the spirits out of the new corn before eating it, faithfulness of the ground to yield its usual crop ʼ, sã̄jẽ n. ʻ vow, promise ʼ; Si. sana, ha˚ ʻ sign ʼ; -- P. H. sain f. ʻ sign, gesture ʼ (in mng. ʻ signature ʼ ← Eng. sign), G. sen f. are obscure. Addenda: saṁjñā -- : WPah.J. sā'n f. ʻ symbol, sign ʼ; kṭg. sánku m. ʻ hint, wink, coquetry ʼ, H. sankī f. ʻ wink ʼ, sankārnā ʻ to hint, nod, wink ʼ Him.I 209.(CDIAL 12874)

meḍ 'body', meḍho 'ram' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (ram hieroglyph, (human) body hieroglyph)

कर्णक m. du. the two legs spread out AV. xx , 133 , 3 rebus: कर्णिक having a helm; a steersman (Monier-Williams) ayas 'alloy metal' (fish hieroglyph)

कोंद kōnda ‘engraver' (one-horned young bull hieroglyph); kundana 'fine gold' (Kannada).

bāṛaï 'carpenter' (boar hieroglyph)

bari barea 'merchant' (boar hieroglyph)

The anthropomorphs are dharma samjña, signifiers of responsibilities of the metalsmith-carpenter-merchant. Signs 389, 387 signify mũhã̄ kuṭhi 'ingot smelter', mũhã̄ kolami 'ingot smithy, forge'.

Anthropomorphs of Sarasvati Civilization are Indus Script hypertexts which signify metalwork.

1.. ![]() Sign 389, bun-ingot shape (oval) + 'twig', i.e. ingots produced from a smelter. This indicates that copper plates on which this hypertext occurs with high frequency are accounting ledgers of products produced from a smelter.

Sign 389, bun-ingot shape (oval) + 'twig', i.e. ingots produced from a smelter. This indicates that copper plates on which this hypertext occurs with high frequency are accounting ledgers of products produced from a smelter. 2. ![]() Sign 387, bun-ingot shape (oval) + 'riceplant', i.e. ingots worked on in a smithy/forge. This hypertext DOES NOT occur on copper plates. This indicates that Sign 387 signifies ingots processed in a smithy/forge, i.e. to forge ingots into metalware, tools, implements, weapons.

Sign 387, bun-ingot shape (oval) + 'riceplant', i.e. ingots worked on in a smithy/forge. This hypertext DOES NOT occur on copper plates. This indicates that Sign 387 signifies ingots processed in a smithy/forge, i.e. to forge ingots into metalware, tools, implements, weapons.

The two distinctly orthographed Indus Script hypertexts signify 1. mũhã̄ kuṭhi 'ingot smelter', 2. mũhã̄ kolami 'ingot smithy, forge'.

![]() Brāhmī syllables on Lines 1 and 2:

Brāhmī syllables on Lines 1 and 2:

शं झ ग śam ña ga saṁjñā -- : WPah.J. sā'n f. ʻsymbol, signʼ(CDIAL 12874)

की म झी थ kī ma jhi tha

![]()

mū̃h baṭa 'iron ingot',

baran, bharat 'mixed copper, zinc, tin alloy metal' and

khāṇḍā metalware.

Majhitha on Line 2 signifies the name of the locality of the metals workshop.

There are a number of localities in many parts of India with the name Majhitha:

1. Locality Name : Majhitha ( मांझीथा ) Block Name : Singhpur District : Rae Bareli State : Uttar Pradesh Division : Lucknow

2. Majhitha Location: Chhattisgarh, Eastern India, Latitude: 21° 26' 8.2" (21.4356°) northLongitude: 82° 0' 48.3" (82.0134°) east Elevation: 276 metres (906 feet)

3. Village : Majitha Block : Shahpura District : Jabalpur State : Madhya Pradesh Pincode Number : 482053

4.

"Majitha located at (31.76°N 74.95°E) is a city and a municipal council in Amritsar district in the Indian state of Punjab. Majitha holds a distinguished place in the history of Punjab as the well-known Majithia Sirdars (chiefs) came from this region. These were several generals in Maharaja Ranjit Singh's army of the Sikh Empire in the first half of the 19th century. No less than ten generals from Majitha can be counted in the Maharaja's army during the period of 1800-1849. Chief amongst the Majithia generals during the Sikh Empire were General Lehna Singh, General (aka Raja) Surat Singh, and General Amar Singh. Sons of General Lehna Singh (Sirdar Dyal Singh) and of General Surat Singh (Sirdar Sundar Singh Majithia) had great impact on the affairs of Punjab during the British rule through the latter 1800s and the first half of the 20th century.

Majithia Sirdars term refers to a set of three related families of Sikh sardars (chiefs) that came from the area of Majitha - a town 10 miles north of the Punjab city of Amritsar and rose to prominence in the early 19th century. The Majithia clans threw in with the rising star of the Sikh misls - Ranjit Singh - during the latter 19th century. As Ranjit Singhestablished the Sikh Empire around the turn of the 19th century, the Majithia sardars gained prominence and became very influential in the Maharaja's army. Ten different Majithia generals can be counted amongst the Sikh army during the period of 1800-1849. According to the English historians, the Majithia family was one of the three most powerful families in Punjab under the Maharaja. Best known of the Majithia generals were General Desa Singh, General Lehna Singh, General Ranjodh Singh, General Surat Singh and General Amar Singh. In all there were 16 Majithia generals in the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The son of General Lehna Singh, Sardar Dyal Singh, was perhaps the most significant Punjabi of the late 19th century in the British Punjab. He was the main force behind the founding of Punjab University; was the founder and the owner of The Tribune newspaper - the most respected English-language newspaper in north-western India to this day; and the founder and owner of the Punjab National Bank - also the most powerful bank in north-western India until nationalized by Indira Gandhi in the early 1970s. He was also one of the charter members of the Indian National Congress party - which later became the main Indian nationalist political party and the party of Nehru and Gandhi. The son of General Surat Singh, Sardar Sundar Singh Majithia, also had tremendous impact on the early 20th century Punjab. He was a main force in the Sikh revivalist movement and was one of the founders of the "Chief Khalsa Diwan Society". Amongst his accomplishments can be counted the establishment of the Khalsa College, Amritsar and the founding of the Punjab and Sind Bank. He was knighted by the British - thus often referred to as Sir Sundar Singh Majithia. Sardar Sundar Singh's brother, Sardar Umrao Singh, was the father of Amrita Sher-Gil - considered by many to be first great female artist of the Indian subcontinent. The Majithia family, although referred to by the name of their village Majitha - which is common in Punjab, in actuality belong to the "Shergill" clan of the Jat Sikhs - itself a subset of the "Gill" clan.

Other famous members of the Majithia family are:

Sardar Parkash Singh Majithia, who was one of the most prominent of the Akali leaders of the 70s, 80s and 90s, and was popularly known as 'Majhe da jarnail'. He remained cabinet minister in many Akali governments holding important portfolios like Transport, Agriculture, and Revenue and Rehabilitation. He was elected MLA five times from Majitha constituency. He also played the stellar role during the Anti-Emergency Morcha and the Dharam Yudh Morcha. In the aftermath of Operation Blue Star, he served as the acting President of Akali Dal. Being the senior most Akali leader in the 1990s, he was unanimously appointed the patron of Shiromani Akali Dal, an honour he retained till his last breath. Sardar Parkash Singh Majitha was also one of the longest serving elected Presidents of the Governing Council of Khalsa College Amritsar. His grandsons Sardar Jagteshwar Singh Majitha (Member, Punjab Public Service Commission), Sardar Ajay Singh Majitha and Sardar Gurteshwar Singh Majitha (senior leader Youth Congress) have also been serving the people of Majitha and have carried the legacy of the family forward. Sardar Parkash Singh Majitha's son late Sardar Simarjit Singh Majithia (Ex. Chairman PUNSEED Punjab) and his nephew Sardar Rajmohinder Singh Majithia (MP and MLA) are also well-known Akali leaders.

Bikram Singh Majithia (Minister and MLA) is another famous Majithia, who is Son of Satyajit Singh Majithia and Grandson of Surjit Singh Majithia and also belongs to the family of the Majithia Sardars. Bikram Singh Majithia was a prominent figure in the Shiromani Akali Dal campaign for the 2007 and 2012 Assembly elections. While in 2007, the party fought a formidable Congress Government, in 2012 Shiromani Akali Dal returned to power consecutively for the second term. Majithia became the president of Youth Akali Dal in 2011. Bikram Singh Majithia took over as New and Renewable Energy Minister, Punjab, he invited entrepreneurs from across the country and the NRIs to invest in solar power sector. The result was that in a short span Punjab was able to attract investment worth Rs 4,000 crore in this sector and the solar power generation tipped to go up from a meagre 9 megawatt to 541 megawatt by 2016.

Sardar Nirranjan Singh Majithia(Beriwale) also belongs to Majithia Sardars families.

References

1. Punjab to generate 4,200 MW solar power by 2022: Bikram Singh Majithia HT Correspondent, Hindustan Times 5 May 2015|

2. Provide easy credit for solar power projects: Bikram Singh Majithia Hindustan Times 24 June 2015.

3. Majithia Family.

Pictorial motifs of anthropomorph

Hieroglyph: mẽḍhā 'curved horn', miṇḍāl 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep; mē̃ḍh 'ram' Rebus: Медь [Med'] (Russian, Slavic) 'copper'. meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.)

Rebus: मृदु, मृदा--कर 'iron, thunderbolt' मृदु mṛdu 'a kind of iron' मृदु-कार्ष्णायसम्,-कृष्णायसम् soft-iron, lead.

![]() Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.

Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'.

~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).

Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.

Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.

KW <i>mENhEd</i>

@(V168,M080)

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

मेढ mēḍha f A forked stake. Used as a post. Hence a short post generally whether forked or not. Pr. हातीं लागली चेड आणि धर मांडवाची मेढ. मेढा mēḍhā m A stake, esp. as forked. 2 A dense arrangement of stakes, a palisade, a paling. 3 fig. A supporter or backer. मेढेकरी mēḍhēkarī m The pillar, prop, stay of See मेढ्या. मेढेकोट mēḍhēkōṭa m (मेढा & कोट) A dense paling; a palisade or stoccade; any defence of stakes. मेढेजोशी mēḍhējōśī m A stake-जोशी; a जोशी who keeps account of the तिथि &c., by driving stakes into the ground: also a class, or an individual of it, of fortune-tellers, diviners, presagers, seasonannouncers, almanack-makers &c. They are Shúdras and followers of the मेढेमत q. v. 2 Jocosely. The hereditary or settled (quasi fixed as a stake) जोशी of a village. मेढेदाई or मेढेदाईक mēḍhēdāī or mēḍhēdāīka c (मेढा & दाय) The owner of the hedge or fence dividing his enclosure from that of his neighbor. मेढेमत mēḍhēmata n (मेढ Polar star, मत Dogma or sect.) A persuasion or an order or a set of tenets and notions amongst the Shúdra-people. Founded upon certain astrological calculations proceeding upon the North star. Hence मेढेजोशी or डौरीजोशी. मेढ्या mēḍhyā a (मेढ Stake or post.) A term for a person considered as the pillar, prop, or support (of a household, army, or other body), the staff or stay. 2 Applied to a person acquainted with clandestine or knavish transactions. 3 See मेढे- जोशी.(Marathi)

मेढा mēḍhā A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl. (Marathi)

मेध m. the juice of meat , broth , nourishing or strengthening drink RV. S3Br. Ka1tyS3r.; a sacrificial animal , victim VS. Br. S3rS.; an animal-sacrifice , offering , oblation , any sacrifice (esp. ifc.) ib. MBh. &c

मेधा f. mental vigour or power , intelligence , prudence , wisdom (pl. products of intelligence , thoughts , opinions) RV. &c; = धन Naigh. ii , 10.

Pictograph: spread legs

Spread legs: कर्णक m. du. the two legs spread out AV. xx , 133 'spread legs'; (semantic determinant) Rebus: karNa 'helmsman', karNI 'scribe, account''supercargo'.

Pictograph: Ram

मेठ a ram भेड m. a ram L. (cf. एड , भेड्र and भेण्ड)