--Indus Script hieroglyphs of wealth & prosperity in Samudramanthanam

-- in long-distance caravan trade and iron-steel in kṣattra, state formation, sovereignty, authority

--eight legs of Śarabha are a reinforcement signifiers of the double-humped camel caravans of Meluhha merchants moving cargo for Ancient Maritime trade across long distances

--signifiers of fish, boar, markhor, one-horned young bull, standing person with spread legs on anthropomorphs are rebus signifiers of alloy metal, wood and iron work, iron smelting work, lapidary work of encasing stones in jewellery, helmsman, supercargo, scribe, accountan

This is an addendum to: Kentum-Satem Proto-Indo-European languages traceable to Uttarakuru Indus Script hieroglyphs Gaṇḍa-Bheruṇḍa, Karabha > Śarabha https://tinyurl.com/yxvqlvah

Of the ten avatara, there are Indus Script hieroglyphic representations related to four avatara: Matsya ‘fish’; kurma ‘tortoise’; Varāha ‘boar’ and Narasimha ‘lion’. This list of four is followed by representations of Gaṇḍa-Bheruṇḍa, Karabha > Śarabha, not as Avatara but as evolutionary signifiers of iron-smelting and crucible steel work and double-humped camel caravans of merchants and artisans engaged in explorations and trade across long distances. Thus, the evolution of four avatara related to alloy metals, bell-metal, working in wood and iron are complemented by transition to the Iron-Steel age coterminous with the Tin-Bronze Revolution, accumulation of wealth by maritime trade navigating Himalayan riverine waterways and Indian Ocean.

Thus, I submit that the ten avatara are a story of civilization are a celebration of technological brilliance of artisans and seafaring merchants (in a Samudra manthanam), evolving from working with alloy metals, to production of bell-metal, working in iron and wood, working in fine gold and ornament gold resulting the Gold Standard differentiating 24-carat purity of gold from 18-carat ornament gold, engaging in long-distance trade on catamarans and double-humped camel caravans across snow-clad mountains of Himalayan ranges and deserts, and emphasizing the sharing of wealth with people.

The Bactrian camel is thought to have been domesticated (independent of the dromedary) sometime before 2500 BC in Northeast Afghanistanor southwestern Turkestan…They can carry loads of 170 kg at more than 17,000 feet which is much more than the ponies that are being used as of now. They can survive without water for at least 72 hours. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bactrian_camel

Riding a double-humped camel in Nubra valley, Ladakh

Riding a double-humped camel in Nubra valley, Ladakh

Double-humped camel. Nubra valley. The Bactrian camel is the largest mammal in its native range and rivals the Dromedary as the largest living camel. Shoulder height is from 180 to 230 cm (5.9 to 7.5 ft), head-and-body length is 225–350 cm (7.38–11.5 ft) and the tail length is 35–55 cm (14–22 in). At the top of the humps, the average height is 213 cm (6.99 ft). Body mass can range from 300 to 1,000 kg (660 to 2,200 lb), with males often being much larger and heavier than females. Its long, wooly coat varies in colour from dark brown to sandy beige. There is a mane and beard of long hair on the neck and throat, with hairs measuring up to 25 cm (9.8 in) long.

Double-humped camel. Nubra valley. The Bactrian camel is the largest mammal in its native range and rivals the Dromedary as the largest living camel. Shoulder height is from 180 to 230 cm (5.9 to 7.5 ft), head-and-body length is 225–350 cm (7.38–11.5 ft) and the tail length is 35–55 cm (14–22 in). At the top of the humps, the average height is 213 cm (6.99 ft). Body mass can range from 300 to 1,000 kg (660 to 2,200 lb), with males often being much larger and heavier than females. Its long, wooly coat varies in colour from dark brown to sandy beige. There is a mane and beard of long hair on the neck and throat, with hairs measuring up to 25 cm (9.8 in) long.

Double-humped Camel caravans in the dunes.

Double-humped Camel caravans in the dunes.

Double-humped camel. Shanghai zoo

Double-humped camel. Shanghai zoo

Ceramic figurine. Sogdian on a camel, Chinese Tang Dynasty (618-907) Shanghai Museum

Ceramic figurine. Sogdian on a camel, Chinese Tang Dynasty (618-907) Shanghai Museum

Ceramic camel. Saint Louis Art Museum. Object Number 181:1942 Tang Dynasty 618-907 ‘This ceramic two-humped Bactrian camel was likely part of a set of objects placed in the tomb of an important person to signify wealth and position in society.’ https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/35735/

Ceramic camel. Saint Louis Art Museum. Object Number 181:1942 Tang Dynasty 618-907 ‘This ceramic two-humped Bactrian camel was likely part of a set of objects placed in the tomb of an important person to signify wealth and position in society.’ https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/35735/

Camel. Philadelphia Art Museum. Made in Chang’an, Shaanxi Province, China. Early to mid-8th cent. Earthenware with three-color (sancai) glaze. Dimensions 32x10x25 inches Acc. No. 1964-9-1 “This sculpture of a Bactrian, or two-humped, camel was probably made as a burial object for a tomb of a wealthy person from the Tang dynasty.With his neck proudly reared, his mouth open, and teeth bared, this fine camel would have been expensive, probably only affordable to someone with means, like an aristocrat, a highranking officer, or a prosperous merchant. Other objects commonly found in tombs include fierce guardian figures, soldiers, and entertainers, representing what one might find useful in the afterlife as well as displaying the affluence and status of the family of the deceased.

Camel. Philadelphia Art Museum. Made in Chang’an, Shaanxi Province, China. Early to mid-8th cent. Earthenware with three-color (sancai) glaze. Dimensions 32x10x25 inches Acc. No. 1964-9-1 “This sculpture of a Bactrian, or two-humped, camel was probably made as a burial object for a tomb of a wealthy person from the Tang dynasty.With his neck proudly reared, his mouth open, and teeth bared, this fine camel would have been expensive, probably only affordable to someone with means, like an aristocrat, a highranking officer, or a prosperous merchant. Other objects commonly found in tombs include fierce guardian figures, soldiers, and entertainers, representing what one might find useful in the afterlife as well as displaying the affluence and status of the family of the deceased.

This camel was decorated with a tricolor (sancai) glaze of cream, green, and amber. The glaze was allowed to run after it was splashed on, creating a free-form effect typical of such objects. The rough texture of some areas, such as the thick neck fur, the upper front legs, and the tips of the camel’s humps, has been carefully highlighted and left unglazed.

Camels symbolized the prosperity of the Silk Route—trade routes between China, Europe, and the Middle East—because they were the main form of transportation in the caravans. This one carries a variety of goods on its packsaddle boards: saddlebags with fanged guardian faces, a twist of wool, an object resembling a large leaf that may be a ladle, and a flask with a shape commonly associated with the Sasanian Empire, which ruled the area of present-day Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Indeed, camel sculptures were trade goods themselves and have even been found as far away as Japan and Egypt.” https://www.philamuseum.org/booklets/3_18_29_0.html

Tarim Basin southern boundary is the Kunlun Mountains on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau.. The Taklamakan Desert dominates much of the basin.

Kunlun Mountains north of Kashmir

Kunlun Mountains north of Kashmir

Śarabha the two-humped camel constituted a vital resource of the caravans of merchants across mountain-ranges, desert and in extreme temperatures ranging from -40 degrees centigrade. Thus, Śarabha symbolised an advancement in the accumulation of wealth of nations beyond the work with metals and gems exemplified by the Narasimha Avatara: simha ‘lion’ rebus: சிங்கச்சுவணம் ciṅka-c-cuvaṇam , n. prob. siṃhala + svarṇa. A kind of superior gold; ஒருவகைஉயர்தரப்பொன். தீதுதீர்சிறப்பிற்சிங்கச்சுவணமென்றோசைபோகியவொண்பொன் (பெருங். வத்தவ. 11, 23). The Avatara which means ‘descent’ is a metaphor to signify an evolution of technologies; Avatara is a term used to signify a material manifestation of divine dispensation. Rigveda describes Indra as endowed with a mysterious power of assuming any form at will. [(3.53.8 (Maghavan); 6.47.18 (Indra)] Dashavatara is listed in the Garuda Purana Five different lists (of Avatara) are included in the Bhagavata Purana, where the difference is in the sequence of the names. I agree with Freda Matchett states that “this re-sequencing by the composers may be intentional, so as to avoid implying priority or placing something definitive and limited to the abstract.”(Matchett, Freda (2001). Krishna, Lord or Avatara?: The Relationship Between Krishna and Vishnu. Routledge.)

Why Avatara? Gitacharya explains it in Bhagavadgita.

Whenever righteousness wanes and unrighteousness increases I send myself forth.

For the protection of the good and for the destruction of evil,

and for the establishment of righteousness,

I come into being age after age.

— Bhagavad Gita 4.7–8

Ten Avatara are:

Matsya--Half fish/half man avatar. He saves the world from a cosmic deluge, with the help of a boat made of the Vedas (knowledge), on which he also rescues Manu (progenitor of man) and all living beings. Demon, Hegriv steals and tries to destroy the Book, but Matsya finds the demon, kills him, and returns the Vedas.

Kurma--Tortoise avatar. He supports the cosmos, while the gods and demons churn the cosmic ocean with the help of serpent Vasuki to produce the nectar of immortality (just like churning milk to produce butter). The churning produces both the good and the bad, including poison and immortality nectar. Nobody wants the poison, everyone wants the immortality nectar.

Varāha -- Boar avatar. He rescues goddess earth when the demon Hiranyaksha kidnaps her and hides her in the depths of cosmic ocean. The boar finds her and kills the demon, and the goddess holds onto the tusk of the boar as he lifts her back to the surface.

Narasimha-- Half lion-half man avatar. Demon king Hiranyakashipu becomes enormously powerful, gains special powers by which no man or animal could kill him, then bullies and persecutes people who disagree with him, including his own son. The Man-Lion avatar creatively defeats those special powers, kills Hiranyakashipu, and rescues demon's son Prahlada who opposes his own father. The legend is a part of the Hindu festival Holi folklore.

Note: It is significant that the subject narratives of the two avatara include people named Kamsa, Hiranyaksha and Hiranyakashipu, all semantically suggestive of metalwork repertoire and metal technology advances. Narasimha avatar is followed by the narratives of Gaṇḍa-Bheruṇḍa, Karabha > Śarabha on Indus Script hieroglyphs on sculptures and also on Indus Script seals. (e.g. Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Bogazkhoy seals and sculpture of double-eagle and hares at Alaca Huyuk, Turkey.)

Vamana-- Demon king Mahabali fought against the Devas and won heaven, and thus became the ruler of heaven, earth, and the underworlds. Though he was a benevolent king, he was a demon, and the devas led by Indra went to Lord Vishnu to help them get heaven back. Lord Vishnu, although didn't want to punish Bali because he was a good king, instead decided to test him. While the king was distributing alms amongst his people, Vishnu in his Vamana avatar approaches Bali in the form of a monk who offers him food, land, money, jewels, and all the riches. However, the monk refuses and asks only for three steps of land. Bali grants it to him. The dwarf grows, in his first step takes the earth and the netherworld, and in the second all of the heavens. Bali, now understanding who it is in front of him, offers his head to the Lord to put his foot on as the third pace. Lord Vishnu gave him the boon of immortality and allowed him to return to his people every year on the occasion of Onam.

Parashurama-- Sage with an axe avatar. The warrior class gets too powerful, and seizes other people's property for their own pleasure. The avatar appears as a sage with an axe, kills all the adharmi kings and all his warrior companions.

Sri Rama-- Subject of Ramayana

Sri Krishna -- Subject of Mahabarata, Krishna Purana and the Bhagavad Gita

Gautama, the Buddha -- Gautam Buddha is considered to be an avatar of Vishnu.

Kalki -- Predicted by All Honourable Traditions Like The First Avatara of Firsts Avataras, and followings, Brightly Holy Avataras. The Whole Avatar of The Lord of any Lords and lords , WHO will tell and Tell the definitive end of The Kali yugas , resolving each and all the illusional illusions , also those generating The Needing of The Wheel of Dharma , and in the very same time , Rightly & Spiritually & Honourably & Peacefully & Lovably & Diligently & Justnessly & MercifulWisdomly & Divinely & 10 Times Holyly , Brightly Holy Start The Eternal Full Revelation of Brightly Holy Divine Potentialities for Human Divines , and for any other Truly Desiring & Augurly & Wishing & Wanting & Willing Brightly Holy Beings

Indus Script hieroglyph: aya ‘fish’ rebus; aya ‘iron’ ayas ‘alloy metal’

Pictorial motif 69 (Mahadevan concordance). Kachchhapa "tortoise" Tortoise/turtle of Indus Script Corpora. कमठ m. ( Un2. i , 102) a tortoise BhP. Pan5cat. &c कमठी f. a female tortoise , a small one (शान्तिशतक) kamaṭhamu kamaṭhamu. [Skt.] n. A tortoise. కమఠి a female tortoise, a small tortoise. కమఠేంద్రుడుkamaṭhēndruḍu. n. The father of tortoises, or king of turtles. (Telugu) Rebus: kãsā kammaṭa'bell-metal coiner, mint, portable furnace'. कमठ m. ( Un2. i , 102) a tortoise kãsā kammaṭa'bell-metal coiner, mint, portable furnace'. See: ‘Turtle’ hieroglyphs on Indus Script signify wealth, metalwork https://tinyurl.com/y8ufpgyw

Pictorial motif 69 (Mahadevan concordance). Kachchhapa "tortoise" Tortoise/turtle of Indus Script Corpora. कमठ m. ( Un2. i , 102) a tortoise BhP. Pan5cat. &c कमठी f. a female tortoise , a small one (शान्तिशतक) kamaṭhamu kamaṭhamu. [Skt.] n. A tortoise. కమఠి a female tortoise, a small tortoise. కమఠేంద్రుడుkamaṭhēndruḍu. n. The father of tortoises, or king of turtles. (Telugu) Rebus: kãsā kammaṭa'bell-metal coiner, mint, portable furnace'. कमठ m. ( Un2. i , 102) a tortoise kãsā kammaṭa'bell-metal coiner, mint, portable furnace'. See: ‘Turtle’ hieroglyphs on Indus Script signify wealth, metalwork https://tinyurl.com/y8ufpgyw

https://frontiers-of-anthropology.blogspot.in/2011/11/giant-turtle-that-bears-world-on-its.html?m=1

A giant turtle (of what was thought to be an extinct species) has been found on Pacific island in 2010 CE !!

"Front view of Meiolania platyceps fossil

"Front view of Meiolania platyceps fossil

Meiolania ("small roamer") is an extinct genus of cryptodire

turtle from the Oligocene to Holocene, with the last relict populations at New Caledonia which survived until 2,000 years ago.

m1528Act

m1529Act2920

m1529Bct

m1532Act

m1532Bct

m1534Act

m1534Bct

1703 Composition:

Two horned heads one at either end of the body. Note the dottings on the thighs which is a unique artistic feature of depicting a turtles (the legs are like those of an elephant?). The body apparently is a combination of two turtles with heads of turtles emerging out of the shell and attached on either end of the composite body.

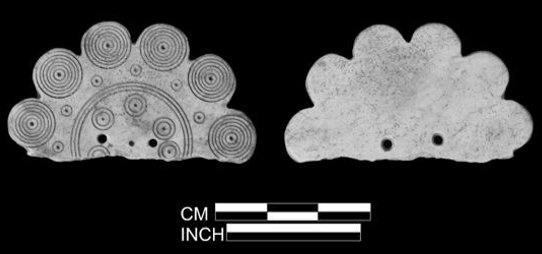

Copper tablet type B18, B17b. Tortoise with mirror duplicaes.

Hieroglyph: two large turtles joined back to back. Thus, signifying meta casting using cire perdue (lost-wax) technique of creating mirror image metal castings from wax casts.

The hieroglyph multiplex on m1534b is now read rebus as: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS kassa 'turtle' rebus: kãsā 'bell-metal' kamaṭha 'turtle' rebus: kãsā kammaṭa'bell-metal coiner, mint, portable furnace'.

kamaṭha crab, tortoise (Gujarati); ‘frog’ (Skt.); rebus: kammaṭa ‘mint’ (Kannada)kampaṭṭam ‘coiner, mint’ (Tamil).கமடம், [ *kamaṭam, ] s. A turtle, a tortoise, ஆமை(Winslow Tamil lexicon) కమఠము [ kamaṭhamu ] kamaṭhamu. [Skt.] n. A tortoise.

Rebus: కమటము [ kamaṭamu ] kamaṭamu. [Tel.] n. A portable furnace for melting the precious metals. అగసాలెవానికుంపటి. Allograph: कमटा or ठा [ kamaṭā or ṭhā ] m (कमठ S) A bow (esp. of bamboo or horn) (Marathi). Allograph 2: kamaḍha ‘penance’ (Pkt.) Rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236)

m1532b On another copper tablet, the emphasis is clearly on the turtle's shell like that of Meiolania's shell.

On copper tablet m1543, the correct identification of the animal heads will be turtle species comparable to Meiolania, a horned large turtle of New Guinea.

Hieroglyph: kassa ‘turtle’: kacchapa m. ʻ turtle, tortoise ʼ MBh. 2. *kacchabha -- . [By pop. etym. through kaccha -- for kaśyápa -- VS. J. Charpentier MO xxvi 110 suggested equivalence in MIA. of kassa -- = kaccha -- to explain creation of kacchapa -- ~ kassapa -- . But K. kochuwu, unless a loan from Ind., points to *kakṣapa -- , which would make the formation earlier.] 1. Pa. kacchapa -- m. ʻ tortoise, turtle, °pinī -- f., Pk. kacchava -- m., °vī -- f., K. kochuwu m. (see above), S. kachãũ, °chū̃ m., L. kachū̃ m., P. kacchū, kacchūkummã̄ m. (< kūrmá -- 1), N. kachuwā, A. kācha, B. kāchim, Or. kechu, °cho, kẽchu, kaï˜cha, °ca, kachima, °cima, Mth. kāchu, Bhoj. Aw. lakh. kachuā; H. kachuā, °chwā m., °uī, °wī f. ʻ tortoise, turtle ʼ, kach -- mach m. ʻ dwellers in the water ʼ (< mátsya -- ) whence kacch, kach m. ʻ turtle, tortoise ʼ, M. kāsav, kã̄s° m., Ko. kāsavu. 2. Pk. amg. kacchabha -- , °aha -- m., °bhī -- f.; Si. käsum̆bu, °ubu H. Smith JA 1950, 188; -- G. kācbɔ m., °bī f. with unexpl. retention of -- b -- and loss of aspiration in c. Addenda: kacchapa -- . 1. A. kācha (phonet. -- s -- ) ʻ tortoise ʼ AFD 217. 2. *kacchabha -- (with -- pa -- replaced by animal suffix -- bha -- ): Md. kahan̆bu ʻ tortoise -- shell ʼ.(CDIAL 2619)

Rebus: OMarw. kāso (= kã̄ -- ?) m. ʻ bell -- metal tray for food, food.

kaṁsá1 m. ʻ metal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metal ʼ Pat. as in S., but would in Pa. Pk. and most NIA. lggs. collide with kāˊṁsya -- to which L. P. testify and under which the remaining forms for the metal are listed. 2. *kaṁsikā -- . 1. Pa. kaṁsa -- m. ʻ bronze dish ʼ; S. kañjho m. ʻ bellmetal ʼ; A. kã̄h ʻ gong ʼ; Or. kãsā ʻ big pot of bell -- metal ʼ; OMarw. kāso (= kã̄ -- ?) m. ʻ bell -- metal tray for food, food ʼ; G. kã̄sā m. pl. ʻ cymbals ʼ; -- perh. Woṭ. kasṓṭ m. ʻ metal pot ʼ Buddruss Woṭ 109. 2. Pk. kaṁsiā -- f. ʻ a kind of musical instrument ʼ; K. kanzü f. ʻ clay or copper pot ʼ; A. kã̄hi ʻ bell -- metal dish ʼ; G. kã̄śī f. ʻ bell -- metal cymbal ʼ, kã̄śiyɔ m. ʻ open bellmetal pan ʼ. kāˊṁsya -- ; -- *kaṁsāvatī -- ? Addenda: kaṁsá -- 1: A. kã̄h also ʻ gong ʼ or < kāˊṁsya -- . (CDIAL 2576) It is possible that the word in Tamil for ‘gold, money’ is cognate with these etyma of Indian sprachbund: காசு³ kācu , n. prob. kāš. cf. kāca. [M. kāšu.] 1. Gold; பொன். (ஆ. நி.) 2. Necklace of gold coins; அச்சுத்தாலி.

காசும் பிறப்புங் கலகலப்ப (திவ். திருப்பா. 7). 3. An ancient gold coin = 28 gr. troy; ஒரு பழைய பொன்னாணயம். (Insc.) 4. A small copper coin;சிறுசெப்புக்

காசு. நெஞ்சே யுனையோர் காசா மதியேன் (தாயு. உடல்பொய். 72). 5. Coin, cash, money; ரொக்கம். எப்பேர்ப்பட்ட பல காசா யங்களும்(S.I.I. i, 89). 6. Gem, crystal bead; மணி.நாண்வழிக்காசுபோலவும் (இறை. 2, உரை, பக். 29). 7. Girdle strung with gems; மேகலாபர ணம்.பட்டுடை சூழ்ந்த காசு (சீவக. 468). 8. (Pros.) A formula of a foot of two nēracaiveṇpā; வெண்பாவின்இறுதிச்

சீர்வாய்பாட்டுள் ஒன்று. (காரிகை, செய். 7.) 9. The hollow in the centre of each rowof pallāṅkuḻi; பல்லாங்குழி யாட்டத்திற் காய்கள் சேர்தற்குரிய நடுக்குழிகள்.

1) కంచరవాడు (p. 224) kañcaravāḍu kanṭsu. n. Bell metal. కంచుకుండ a bowl or vessel or bell metal.కంచువాద్యము a cymbal made of bell metal. కంచుతీసినట్లు as...

2) కంచము (p. 223) kañcamu kanṭsamu. [Tel.] n. A metal plate or dish. కంచుకంచము a dish made of bell metal. మా కంచములో రాయి వేసినాడు he threw a stone into our place, i.e., took away our bread, he disturbed us. మందకంచము a dish which as a rim. ఆకుకంచము a dish which has none.

2) ) కంసర (p. 227) kaṃsara or కంసలల kamsara. [Tel.] n. Smithery; working in gold: adj. Of the goldsmith caste. కంసలది a woman of that caste. కంసలపని the business of a gold-smith.

3) కంసము (p. 227) kaṃsamu kamsamu. [Skt.] n. Bell metal.కంచు.

4) కాంస్యము (p. 265) kāṃsyamu kāmsyamu. [Skt.] n. Bell metal. కంచు.

4) కంసాలి (p. 227) kaṃsāli or కంసాలవాడు kamsāli. [Tel.] n. A goldsmith or silversmith.

5) కంచరవాడు (p. 224) kañcaravāḍu or కంచరి kanṭsara-vaḍu. [Tel.] n. A brazier, a coppersmith. కంచుపనిచేయువాడు. కంచరది a woman of that caste. కంచరిపురుగు kanṭsari-purugu. n. A kind of beetle called the death watch. కంచు kanṭsu. n. Bell metal. కంచుకుండ a bowl or vessel or bell metal. కంచువాద్యము a cymbal made of bell metal. కంచుతీసినట్లు as bright or dazzling as the glitter of polished metal. Sunbright.ఆమె కంచుగీచినట్లు పలికె she spoke shrilly or with a voice as clear as a bell.

కాంచనము (p. 265) kāñcanamu kānchanamu. [Skt.] n. Gold. కాంచనవల్లి a piece of gold wire.కాంచనాంబరము tissue, gold cloth. Kāñcana काञ्चन a. (-नी f.) [काञ्च्-ल्युट्] Golden, made of gold; तन्मध्ये च स्फटिकफलका काञ्चनी वासयष्टिः Me.81; काञ्चनंवलयम् Ś.6.8; Ms.5.112. -नम् 1 Gold; समलोष्टाश्मकाञ्चनः Bg. 14.24. (ग्राह्यम्) अमेध्यादपि काञ्चनम् Ms.2.239. -2 Lustre, brilliancy. -3 Property, wealth, money. (Apte). kāñcaná ʻ golden ʼ MBh., n. ʻ gold ʼ Mn.Pa. kañcana -- n. ʻ gold ʼ, °aka -- ʻ golden ʼ; Pk. kaṁcaṇa<-> n. ʻ gold ʼ; Si. kasuna ʻ gold ʼ, kasun -- ʻ golden ʼ. (CDIAL 3013)காஞ்சனம்¹ kāñcaṉam , n. < kāñcana. Gold; பொன். (திவா.) కాంచనము (p. 265) kāñcanamu kānchanamu. [Skt.] n. Gold. కాంచనవల్లి a piece of gold wire. కాంచనాంబరము tissue, gold cloth.

The hieroglyph multiplex on m1534b is now read rebus as: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS kassa 'turtle' rebus: kãsā 'bell-metal' kamaṭha 'turtle' rebus: kãsā kammaṭa 'bell-metal coiner, mint, portable furnace'.

कंस[p= 241,1] mn. ( √कम् Un2. iii , 62), a vessel made of metal , drinking vessel , cup , goblet AV. x , 10 , 5 AitBr. S3Br. &c; a metal , tutanag or white copper , brass , bell-metal

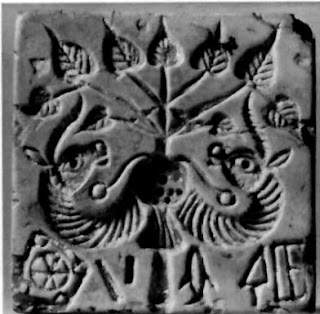

Kīr̤aḍi carnelian boar Indus Script hieroglyph signifies artificer, merchant and carnelian is from Gujarat

Orange carnelian stone with wild boar engraved on it; it is a stamp, balanced on top of a glass holder; a seal

Orange carnelian stone with wild boar engraved on it; it is a stamp, balanced on top of a glass holder; a seal

The carnelian ring seal of Kīr̤aḍi(கீழடி) signifies an artificer of the civilization. barāh, baḍhi 'boar' vāḍhī, bari, barea 'merchant' bārakaśa 'seafaring vessel', ಬಡಿಗ'artificer', बढई baḍhī 'worker in wood and iron', వడ్లబత్తుడు'carpenter'.

barāh or varāha 'divine boar' is thus an artificer of both Sarasvati Civilization and Vaigai Civilization.barāh, varāha unifies Sarasvati and Vaigai rivers, affirming the essential cultural unity of the nation of Bhāratam.

varāha 'divine boar' is the yajna purusha, as evidenced on the Khajuraho Chitragupta temple of varāha 'divine boar'.

This boar Indus Script hieroglyph on carnelian ring links Kīr̤aḍi (கீழடி) with Sarasvati Civilization which had an anthropomorph with boar as the signature tune of the civilization.

This anthropomorph is the signifier of an artificer of the civilization because the anthropomorph shows on the chest a 'unicorn' or spiny-horned young bull which is the most frequently used hieroglyph in Indus Script Corpora.

Importance of the boar hieroglyph may be seen from the fact that an anthropomorph has a boar atop the ram hieroglyph with spread legs and a 'unicorn' on the chest. See decipherment at https://tinyurl.com/yxopm7u5 Mirror: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2019/03/indus-script-hypertexts-are-meluhha.html

On one anthropomorph, an over-written Brahmi inscription is found and deciphered. Summary: barāh, baḍhi 'boar' vāḍhī, bari, barea 'merchant' bārakaśa 'seafaring vessel'. manji 'dhow, seafaring vessel'eka-shingi 'one-masted' koḍiya ‘young bull’, koṭiya 'dhow', kũdār 'turner, brass-worker'.

kundar 'young bull' rebus: kunda 'wealth', kundaṇa 'fine gold' khonda 'young bull' rebus: khoTa 'wedge, alloy metal' PLUS konda 'furnace'. singhin 'spiny-horned' rebus; singi 'ornament gold' PLUS kunda 'fine gold'. Thus, the young single-horned bull calf signifies kundar, 'turner' of fine and ornament gold.

Brāhmī inscription on Indus Script anthropomorph reads: symbol of मांझीथा Majhīthā sadya 'member of mã̄jhī boatpeople assembly (community)' https://tinyurl.com/y85lflto

This is an addendum to:

Anthropomorphs as Indus Script hypertexts, professional calling cards and Copper Hoard Cultures of Ancient India https://tinyurl.com/y7qc7t73

Like the Dholavira sign board, the anthropormorph if displayed on the gateway of workers' quarters or locality is a proclamation symbol of मांझीथाMajhīthā sadya 'member of mã̄jhīboatpeople assembly (community)'. The pictrographs of young bull, ram's horns, spread legs, boar signify:

goldsmith, iron metalworker, merchant, steersman.

[Details: कोंद kōnda ‘engraver' (one-horned young bull hieroglyph); kundana 'fine gold' (Kannada) PLUS bāṛaï 'carpenter' bari barea 'merchant' (boar hieroglyph) PLUS karṇaka कर्णकsteersman ('spread legs'); meḍho 'ram' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ'iron']

Brāhmī inscription on Indus Script anthropomorph reads (on the assumption that Line 3 is an inscription with Indus Script hypertexts):

śam ña ga kī ma jhi tha mū̃h baṭa baran khāṇḍā

samjñā 'symbol, sign'

kī ma jhi tha 'of Majhitha'

Sha (?) Da Ya शद sad-a 'produce (of a country)'.-shad-ya, m. one who takes part in an assembly, spectator

Meaning:

Line 1 (Brāhmī syllables): samjñā 'symbol, sign' (of)

Line 2 (Brāhmī syllables): kī ma jhi tha 'of Majhitha locality or mã̄jhī boatpeople community or workers in textile dyeing: majīṭh 'madder'. The reference may also be to mañjāḍi (Kannada) 'Adenanthera seed weighing two kuṉṟi-mani, used by goldsmiths as a weight'.

Line 3 (Indus Script hieroglyphs): baṭa 'iron' bharat 'mixed alloys' (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) mū̃h 'ingots' khāṇḍā 'equipments'.

Alternative reading of Line 3 (if read as Brāhmī syllables): Sha (?) Da Ya शद sad-a signifies: 'produce (of a country' or -shad-ya, m. one who takes part in an assembly, spectator.

Thus,an alternative reading is that the threelines may signify symbol of मांझीथा Majhīthā sadya 'assembly participant' or member of mã̄jhī boatpeople assembly (community).

Thus, this is a proclamation, a hoarding which signifies the Majitha locality (working in) iron, mixed alloys (bharat) ingots and equipments. Alternative reding is: symbol (of) produce of Majhitha locality or community

Alternatives:

A cognate word signifies boatman: *majjhika ʻ boatman ʼ. [Cf. maṅga -- ?] N. mājhi, mã̄jhi ʻ boatman ʼ; A. māzi ʻ steersman ʼ, B. māji; Or. mājhi ʻ steersman ʼ, majhiā ʻ boatman ʼ, Bi. Mth. H. mã̄jhī m.(CDIAL 9714).மஞ்சி2 mañci, n. 1. cf. mañca. [M. mañji.] Cargo boat with a raised platform; படகு. Thus, a majhitha artisan is also a boatman.

A cognate word is: mañjiṣṭhā f. ʻ the Indian madder (Rubia cordifolia and its dye) ʼ Kauś. [mañjiṣṭha -- ] Pa. mañjeṭṭhī -- f. ʻ madder ʼ, Pk. maṁjiṭṭhā -- f.; K. mazēṭh, dat. ˚ṭhi f. ʻ madder plant and dye (R. cordifolia or its substitute Geranium nepalense) ʼ; S. mañuṭha, maĩṭha f. ʻ madder ʼ; P. majīṭ(h), mãj˚ f. ʻ root of R. cordifolia ʼ; N. majiṭho ʻ R. cordifolia ʼ, A. mezāṭhi, maz˚, OAw. maṁjīṭha f.; H. mãjīṭ(h), maj˚ f. ʻ madder ʼ, G. majīṭh f., Ko. mañjūṭi; -- Si. madaṭa ʻ a small red berry ʼ, madaṭiya ʻ the tree with red wood Adenanthera pavonina (Leguminosae) ʼ; Md. madoři ʻ a weight ʼ.māñjiṣṭha -- .Addenda: mañjiṣṭhā -- [Cf. Drav. Kan. mañcaṭige, mañjāḍi, mañjeṭṭi S. M. Katre]: S.kcch. majīṭh f. ʻ madder ʼ.(CDIAL 9718) மஞ்சிட்டி mañciṭṭi, n. < mañjiṣṭhā. 1. Munjeet, Indian madder, Rubia cordifolia; நீர்ப்பூடுவகை. (I. P.) 2. Arnotto. See சாப்பிரா. (L.) 3. Chayroot for dyeing; சாயவேர். (L.) மஞ்சாடி mañcāṭi, n. [T. manḍzādi, K. mañjāḍi.] 1. Red-wood, m. tr., Adenanthera paronina; மரவகை. 2. Adenanthera seed weighing two kuṉṟi-mani, used by goldsmiths as a weight; இரண்டுகுன்றிமணிகளின்எடைகொண்டமஞ்சாடிவித்து. (S. I. I. i, 114, 116.)

The wor manjhitha may be derived from the root: मञ्ज् mañj मञ्ज्1 U. (मञ्जयति-ते) 1 To clean, purify, wipe off. Thus, the reference is to a locality of artisans engaged in purifying metals and alloys. Such purifiers or assayers of metal are also referred to as पोतदार pōtadāra m ( P) An officer under the native governments. His business was to assay all money paid into the treasury. He was also the village-silversmith. (Marathi)

Subhash Kak has suggested alternate readings, see: https://medium.com/@subhashkak1/a-reading-of-the-br%C4%81hm%C4%AB-letters-on-an-anthropomorphic-figure-2a3c505a9acd

The reading of the Munjals is reproduced below:

Sa Thi Ga

Ki Ma Jhi Tha

Sha (?) Da Ya

Subhash Kak reads the letters as:

śam ña ga

kī ma jhi tha

ta ḍa ya

that is

शंञग

कीमझिथ

तडय

शंझग śam ña ga

कीमझीथ kī ma jhi tha

Figure 1. The copper object and the text together with the reading in Munjal, S.K. and Munjal, A. (2007). Composite anthropomorphic figure from Haryana: a solitary example of copper hoard. Prāgdhārā (Number 17).

Third line of Brāhmī inscription: Line 3

तडय ta ḍa ya (This third line has to be read as Indus Script hieroglyphs/hypertexts and NOT as Brami syllables). Subhash Kak suggests that this third line taḍaya may signify"punishment to inimical forces."

Third line read as Indus Script hieroglyphs/hypertexts is deciphered as:

mū̃h baṭa 'iron ingot',

baran, bharat 'mixed copper, zinc, tin alloy metal' and

khāṇḍā metalware.

Anthropomorph found in a foundation of a house in a village called Kheri Gujar in Sonepat District in Haryana. The house itself rests on an ancient mound that has been variously dated to Late Harappan. The object is about 2 kg. and has dimensions of 30×28.5 cm.

It is possible that Line 3 is a composition of Indus Script Hieroglyphs (and NOT Brāhmī syllables). Framed on this hypothesis, the message of Line 3 signifies:

mū̃h baṭa 'iron ingot',

baran, bharat 'mixed copper, zinc, tin alloy metal' and

khāṇḍā metalware.

Hypertext of Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUSSign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron'

Sign 48 is a 'backbone, spine' hieroglyph: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat 'mixed alloys' (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin)

Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻa caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023). ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) Thus ciphertext kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ is rebus hypertext kāṇḍa 'excellent iron', khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

saṁjñāˊ f. ʻagreement, understanding ʼŚBr., ʻsign ʼMBh. [√jñā]Pa. saññā -- f. ʻ sense, sign ʼ, Pk. saṁṇā -- f.; S. sañaṇu ʻto point out ʼ; WPah.jaun. sān ʻsign ʼ, Ku. sān f., N. sān; B. sān ʻ understanding, feeling, gesture ʼ; H. sān f. ʻsign, token, trace ʼ; G. sān f. ʻsense, understanding, sign, hint ʼ; M. sã̄j̈ f. ʻ rule to make an offering to the spirits out of the new corn before eating it, faithfulness of the ground to yield its usual crop ʼ, sã̄jẽ n. ʻvow, promise ʼ; Si. sana, ha˚ ʻsign ʼ; -- P. H. sain f. ʻsign, gesture ʼ (in mng. ʻ signature ʼ← Eng. sign), G. sen f. are obscure. Addenda: saṁjñā -- : WPah.J. sā'n f. ʻsymbol, sign ʼ; kṭg. sánku m. ʻhint, wink, coquetry ʼ, H. sankī f. ʻwink ʼ, sankārnā ʻto hint, nod, wink ʼ Him.I 209.(CDIAL 12874)

meḍ 'body', meḍho 'ram' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ'iron' (ram hieroglyph, (human) body hieroglyph)

कर्णक m. du. the two legs spread out AV. xx , 133 , 3 rebus: कर्णिक having a helm; a steersman (Monier-Williams)

ayas 'alloy metal' (fish hieroglyph)

कोंद kōnda ‘engraver' (one-horned young bull hieroglyph); kundana 'fine gold' (Kannada).

bāṛaï 'carpenter' (boar hieroglyph)

bari barea 'merchant' (boar hieroglyph)

The anthropomorphs are dharma samjña, signifiers of responsibilities of the metalsmith-carpenter-merchant. Signs 389, 387 signify mũhã̄kuṭhi 'ingot smelter', mũhã̄kolami 'ingot smithy, forge'.

Anthropomorphs of Sarasvati Civilization are Indus Script hypertexts which signify metalwork.

Sign 389, bun-ingot shape (oval) + 'twig', i.e. ingots produced from a smelter. This indicates that copper plates on which this hypertext occurs with high frequency are accounting ledgers of products produced from a smelter.

Sign 387, bun-ingot shape (oval) + 'riceplant', i.e. ingots worked on in a smithy/forge. This hypertext DOES NOT occur on copper plates. This indicates that Sign 387 signifies ingots processed in a smithy/forge, i.e. to forge ingots into metalware, tools, implements, weapons.

The two distinctly orthographed Indus Script hypertexts signify 1. mũhã̄kuṭhi 'ingot smelter', 2. mũhã̄kolami 'ingot smithy, forge'.

Brāhmī syllables on Lines 1 and 2:

शंझग śam ña ga saṁjñā -- : WPah.J. sā'n f. ʻsymbol, signʼ(CDIAL 12874)

कीमझीथ kī ma jhi tha

mū̃h baṭa 'iron ingot',

baran, bharat 'mixed copper, zinc, tin alloy metal' and

khāṇḍā metalware.

Majhitha on Line 2 signifies the name of the locality of the metals workshop.

There are a number of localities in many parts of India with the name Majhitha:

1. Locality Name : Majhitha ( मांझीथा ) Block Name : Singhpur District : Rae Bareli State : Uttar Pradesh Division : Lucknow

2. Majhitha Location: Chhattisgarh, Eastern India, Latitude: 21° 26' 8.2" (21.4356°) northLongitude: 82° 0' 48.3" (82.0134°) east Elevation: 276 metres (906 feet)

3. Village : Majitha Block : Shahpura District : Jabalpur State : Madhya Pradesh Pincode Number : 482053

4.

Majitha | |

city | |

Majitha Location in Punjab, India | |

Coordinates: | |

Country | |

Government | |

• Type | state government |

Population (2011) | |

• Total | 14,503 |

Languages | |

• Official | |

Majitha is a town and a municipal council in Amritsar district in the Indian state of Punjab. Majhitha Road, Amritsar-143001, Punjab

The Majithia Sirdars are a family of Shergill Jat sardars (chiefs) that came from the area of Majitha in the Punjab.

"Majitha located at is a city and a municipal council in Amritsar district in the Indian state of Punjab. Majitha holds a distinguished place in the history of Punjab as the well-known Majithia Sirdars (chiefs) came from this region. These were several generals in Maharaja Ranjit Singh's army of the Sikh Empire in the first half of the 19th century.

No less than ten generals from Majitha can be counted in the Maharaja's army during the period of 1800-1849. Chief amongst the Majithia generals during the Sikh Empire were General Lehna Singh, General (aka Raja) Surat Singh, and General Amar Singh. Sons of General Lehna Singh (Sirdar Dyal Singh) and of General Surat Singh (Sirdar Sundar Singh Majithia) had great impact on the affairs of Punjab during the British rule through the latter 1800s and the first half of the 20th century.

Hari Singh Nalwa was the most celebrated general of the Sikh Kingdom. His family was known to have migrated to Gujranwala (now in Pakistan) from Majitha sometime in the eighteenth century." http://www.sikhiwiki.org/index.php/Majitha

Majithia Sirdars term refers to a set of three related families of Sikh sardars (chiefs) that came from the area of Majitha - a town 10 miles north of the Punjab city of Amritsar and rose to prominence in the early 19th century.

The Majithia clans threw in with the rising star of the Sikh misls - Ranjit Singh - during the latter 19th century. As Ranjit Singhestablished the Sikh Empire around the turn of the 19th century, the Majithia sardars gained prominence and became very influential in the Maharaja's army. Ten different Majithia generals can be counted amongst the Sikh army during the period of 1800-1849.

According to the English historians, the Majithia family was one of the three most powerful families in Punjab under the Maharaja. Best known of the Majithia generals were General Desa Singh, General Lehna Singh, General Ranjodh Singh, General Surat Singh and General Amar Singh. In all there were 16 Majithia generals in the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The son of General Lehna Singh, Sardar Dyal Singh, was perhaps the most significant Punjabi of the late 19th century in the British Punjab. He was the main force behind the founding of Punjab University; was the founder and the owner of The Tribune newspaper - the most respected English-language newspaper in north-western India to this day; and the founder and owner of the Punjab National Bank - also the most powerful bank in north-western India until nationalized by Indira Gandhi in the early 1970s. He was also one of the charter members of the Indian National Congress party - which later became the main Indian nationalist political party and the party of Nehru and Gandhi.

The son of General Surat Singh, Sardar Sundar Singh Majithia, also had tremendous impact on the early 20th century Punjab. He was a main force in the Sikh revivalist movement and was one of the founders of the "Chief Khalsa Diwan Society". Amongst his accomplishments can be counted the establishment of the Khalsa College, Amritsar and the founding of the Punjab and Sind Bank. He was knighted by the British - thus often referred to as Sir Sundar Singh Majithia.

Sardar Sundar Singh's brother, Sardar Umrao Singh, was the father of Amrita Sher-Gil - considered by many to be first great female artist of the Indian subcontinent.

The Majithia family, although referred to by the name of their village Majitha - which is common in Punjab, in actuality belong to the "Shergill" clan of the Jat Sikhs - itself a subset of the "Gill" clan.

Other famous members of the Majithia family are:

Sardar Parkash Singh Majithia, who was one of the most prominent of the Akali leaders of the 70s, 80s and 90s, and was popularly known as 'Majhe da jarnail'. He remained cabinet minister in many Akali governments holding important portfolios like Transport, Agriculture, and Revenue and Rehabilitation. He was elected MLA five times from Majitha constituency. He also played the stellar role during the Anti-Emergency Morcha and the Dharam Yudh Morcha. In the aftermath of Operation Blue Star, he served as the acting President of Akali Dal. Being the senior most Akali leader in the 1990s, he was unanimously appointed the patron of Shiromani Akali Dal, an honour he retained till his last breath.

Sardar Parkash Singh Majitha was also one of the longest serving elected Presidents of the Governing Council of Khalsa College Amritsar. His grandsons Sardar Jagteshwar Singh Majitha (Member, Punjab Public Service Commission), Sardar Ajay Singh Majitha and Sardar Gurteshwar Singh Majitha (senior leader Youth Congress) have also been serving the people of Majitha and have carried the legacy of the family forward. Sardar Parkash Singh Majitha's son late Sardar Simarjit Singh Majithia (Ex. Chairman PUNSEED Punjab) and his nephew Sardar Rajmohinder Singh Majithia (MP and MLA) are also well-known Akali leaders.

Bikram Singh Majithia (Minister and MLA) is another famous Majithia, who is Son of Satyajit Singh Majithia and Grandson of Surjit Singh Majithia and also belongs to the family of the Majithia Sardars. Bikram Singh Majithia was a prominent figure in the Shiromani Akali Dal campaign for the 2007 and 2012 Assembly elections. While in 2007, the party fought a formidable Congress Government, in 2012 Shiromani Akali Dal returned to power consecutively for the second term. Majithia became the president of Youth Akali Dal in 2011.

Bikram Singh Majithia took over as New and Renewable Energy Minister, Punjab, he invited entrepreneurs from across the country and the NRIs to invest in solar power sector. The result was that in a short span Punjab was able to attract investment worth Rs 4,000 crore in this sector and the solar power generation tipped to go up from a meagre 9 megawatt to 541 megawatt by 2016.

Harsimrat Kaur Badal (M.P,President women Shiromani Akali Dal) who is wife of Deputy Chief Minister of Punjab Sukhbir Singh Badal. She also belongs to family of Majithia Sirdars. She is daughter of Satyajit Singh Majithia and Granddaughter of Surjit Singh Majithia as well as daughter-in-law Parkash Singh Badal.

Sardar Nirranjan Singh Majithia(Beriwale) also belongs to Majithia Sardars families.

References

1. Punjab to generate 4,200 MW solar power by 2022: Bikram Singh Majithia HT Correspondent, Hindustan Times 5 May 2015|

2. Provide easy credit for solar power projects: Bikram Singh Majithia Hindustan Times 24 June 2015.

3. Majithia Family.

https://ipfs.io/ipfs/QmXoypizjW3WknFiJnKLwHCnL72vedxjQkDDP1mXWo6uco/wiki/Majithia_Sirdars.html

Pictorial motifs of anthropomorph

Hieroglyph: mẽḍhā 'curved horn', miṇḍāl 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep; mē̃ḍh 'ram' Rebus: Медь [Med'] (Russian, Slavic) 'copper'. meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.)

Rebus: मृदु, मृदा--कर'iron, thunderbolt' मृदु mṛdu 'a kind of iron' मृदु-कार्ष्णायसम्,-कृष्णायसम् soft-iron, lead.

Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.

Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'.

~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).

Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.

Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.

KW <i>mENhEd</i>

@(V168,M080)

http://www.ling.hawaii.edu/austroasiatic/AA/Munda/ETYM/Pinnow&Munda

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

http://www.vanderkrogt.net/elements/element.php?sym=Cu

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

मेढ mēḍha f A forked stake. Used as a post. Hence a short post generally whether forked or not. Pr. हातींलागलीचेडआणिधरमांडवाचीमेढ. मेढा mēḍhā m A stake, esp. as forked. 2 A dense arrangement of stakes, a palisade, a paling. 3 fig. A supporter or backer. मेढेकरी mēḍhēkarī m The pillar, prop, stay of See मेढ्या. मेढेकोट mēḍhēkōṭa m (मेढा& कोट) A dense paling; a palisade or stoccade; any defence of stakes. मेढेजोशी mēḍhējōśī m A stake-जोशी; a जोशीwho keeps account of the तिथि&c., by driving stakes into the ground: also a class, or an individual of it, of fortune-tellers, diviners, presagers, seasonannouncers, almanack-makers &c. They are Shúdras and followers of the मेढेमत q. v. 2 Jocosely. The hereditary or settled (quasi fixed as a stake) जोशी of a village. मेढेदाई or मेढेदाईक mēḍhēdāī or mēḍhēdāīka c (मेढा& दाय) The owner of the hedge or fence dividing his enclosure from that of his neighbor. मेढेमत mēḍhēmata n (मेढ Polar star, मत Dogma or sect.) A persuasion or an order or a set of tenets and notions amongst the Shúdra-people. Founded upon certain astrological calculations proceeding upon the North star. Hence मेढेजोशी or डौरीजोशी. मेढ्या mēḍhyā a (मेढ Stake or post.) A term for a person considered as the pillar, prop, or support (of a household, army, or other body), the staff or stay. 2 Applied to a person acquainted with clandestine or knavish transactions. 3 See मेढे- जोशी.(Marathi)

मेढा mēḍhā A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl. (Marathi)

मेध m. the juice of meat , broth , nourishing or strengthening drink RV. S3Br. Ka1tyS3r.; a sacrificial animal , victim VS. Br. S3rS.; an animal-sacrifice , offering , oblation , any sacrifice (esp. ifc.) ib. MBh. &c

मेधा f. mental vigour or power , intelligence , prudence , wisdom (pl. products of intelligence , thoughts , opinions) RV. &c; = धन Naigh. ii , 10.

Pictograph: spread legs

Spread legs: कर्णक m. du. the two legs spread out AV. xx , 133 'spread legs'; (semantic determinant) Rebus: karNa 'helmsman', karNI 'scribe, account''supercargo'.

Pictograph: Ram

मेठ a ram भेड m. a ram L. (cf. एड , भेड्र and भेण्ड)

मेंढा mēṇḍhā m (मेषS through H) A male sheep, a ram or tup. 2 A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेंढी mēṇḍhī f (मेंढा or H) A female sheep, a newe मेंढें mēṇḍhēṃ n (मेंढा) A sheep. Without reference to sex. 9606 bhēḍra -- , bhēṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ lex. [← Austro -- as. J. Przyluski BSL xxx 200: perh. Austro -- as. *mēḍra ~ bhēḍra collides with Aryan mḗḍhra -- 1 in mēṇḍhra -- m. ʻ penis ʼ BhP., ʻ ram ʼ lex. -- See also bhēḍa -- 1, mēṣá -- , ēḍa -- . -- The similarity between bhēḍa -- 1, bhēḍra -- , bhēṇḍa -- ʻ ram ʼand *bhēḍa -- 2 ʻdefective ʼ is paralleled by that between mḗḍhra -- 1, mēṇḍha -- 1 ʻram ʼ and *mēṇḍa -- 1, *mēṇḍha -- 2 (s.v. *miḍḍa -- ) ʻ defective ʼ]

Ḍ. bēḍa f. ʻ sheep ʼ, K.ḍoḍ. bhĕḍă pl., L. bheḍ̠ f., awāṇ. bheḍ, bhiḍ, P. bheḍ, ˚ḍī f., ˚ḍā m.; WPah.bhal. (LSI) ḍhleḍḍ, (S. Varma) bheṛ, pl. ˚ṛã f. ʻ sheep and goats ʼ, bhad. bheḍḍ, cur. bhraḍḍ, bhēḍḍū, cam. bhēṛ, khaś. bhiḍṛu n. ʻ lamb ʼ; Ku. N. bheṛo ʻram ʼ, bheṛi ʻ ewe ʼ; A. bherā, bhẽrā ʻ sheep ʼ; B. bheṛ ʻ ram ʼ, ˚ṛā ʻ sheep ʼ, ˚ṛi ʻewe ʼ, Or. bheṛā, ˚ṛi, bhẽṛi; Bi. bhẽṛ ʻsheep ʼ, ˚ṛā ʻ ram ʼ; Mth. bhẽṛo, ˚ṛī; Bhoj. bheṛā ʻ ram ʼ; Aw.lakh. bhẽṛī ʻsheep ʼ; H. bheṛ, ˚ṛī f., ˚ṛā m., G. bheṛi f.; -- X mēṣá -- : Kho. beṣ ʻyoung ewe ʼ BelvalkarVol 88.*bhaiḍraka -- ; *bhēḍrakuṭikā -- , *bhēḍrapāla -- , *bhēḍravr̥ti -- .

Addenda: bhēḍra -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) bhèṛ m. ʻ sheep ʼ, bhèṛi f., J. bheḍ m.†*bhēḍravāṭa -- , †*bhēḍriya -- .

1) bhēḍa 9604 bhēḍa1 m. ʻ sheep ʼ, bhaiḍaka -- ʻ of sheep ʼ lex. [bhēḍra- X ēḍa -- ?]Ash. biar ʻ she -- goat ʼ, Pr. byär, Bshk. bür; Tor. birāṭh ʻhe -- goat ʼ, Phal. bhīṛo: all with AO viii 300 doubtful. 9607 *bhēḍrakuṭikā ʻ sheepfold ʼ. [bhēḍra -- , kuṭī -- ]WPah.cam. bhaṛōṛī or < *bhēḍravr̥ti -- .

9608 *bhēḍrapāla ʻshepherd ʼ. [bhēḍra -- , pālá -- ]G. bharvāṛ m. ʻ shepherd or goatherd ʼ, ˚ṛaṇi f. ʻhis wife ʼ (< *bhaḍvār).*bhēḍravr̥ti -- ʻsheepfold ʼ. [bhēḍra -- , vr̥ti -- ]See *bhēḍrakuṭikā -- .Addenda: *bhēḍrapāla -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) bəḍhàḷɔ m., bəṛaḷɔ m. ʻshepherd ʼ.9608a †*bhēḍravāṭa -- ʻsheepfold ʼ. [bhēḍra -- , vāṭa -- 1]WPah.kc. bərhaṛo n. ʻstorey in house where sheep and goats are kept ʼ, bəṛhε̄`ḷ m. id. (< *bhēḍrīvāṭa -- ?), bəṛhāˋḷ m. ʻ sheep shed ʼ Him.I 151, 152.9608b †*bhēḍriya -- ʻsheep -- killer ʼ. [bhēḍra -- semant. cf. *huḍahāra -- ]WPah.kc. bheṛio m. ʻjackal ʼ; H. bheṛiyā m. ʻwolf ʼ. 2512 ēḍa m. ʻa kind of sheep ʼ KātyŚr., ēḍī -- f., ēḍaka -- 1 m. ʻa sheep or goat ʼ, aiḍa -- ʻovine ʼMBh., aiḍaká m. ʻa kind of sheep ʼŚBr., iḍikka -- f. ʻwild goat ʼ lex. [← Drav. EWA i 126 with lit.]Pa. eḷaka -- m. ʻram, wild goat ʼ, ˚akā -- , ˚ikā -- , ˚ikī -- f.; Aś. eḍaka -- m. ʻram ʼ, ˚kā -- f. ʻewe ʼ, NiDoc. heḍ'i ʻsheep (?) ʼ Burrow KharDoc 10 (cf. h -- in Brahui hēṭ ʻshe -- goat ʼ); Pk. ēla -- , ˚aya -- m. ʻram ʼ, ēliyā -- f., ēḍayā -- f., ēḍakka -- m., Paš. weg. ēṛāˊ, kuṛ. e_ṛṓ, ar. yeṛó, že˚ m. ʻram ʼ, weg. ēṛī, kuṛ. e_˚, ar. ye˚ f. ʻ ewe ʼ; Shum. yēṛə, yeṛṓlik m. ʻsheep ʼ, yeṛélik f., Gaw. ēṛa, yē˚ m., ēṛī, yē˚ f., Bshk. īr f., Tor. öi f. (less likely < ávi -- ), Mai. "'ī" Barth NTS xviii 123, Sv. yeṛo m., ēṛia f., Phal. yīṛo m., ˚ṛi f., Sh. jij. ḗṛi; S. eli -- pavharu m. ʻgoatherd ʼ; Si. eḷuvā ʻgoat ʼ; <-> X bhēḍra -- q.v.*kaiḍikā -- . 5152 Ta. yāṭu, āṭu goat, sheep; āṭṭ-āḷ shepherd. Ma. āṭu goat, sheep; āṭṭukāran shepherd. Ko. a·ṛ (obl. a·ṭ-) goat. To. o·ḍ id. Ka. āḍu id. Koḍ. a·ḍï id. Tu. ēḍů id. Te. ēḍika, (B.) ēṭa ram. Go. (Tr. Ph. W.) yēṭī, (Mu. S.) ēṭi she-goat (Voc. 376). Pe. ōḍa goat. Manḍ. ūḍe id. Kui ōḍa id. Kuwi (Mah. p. 110) o'ḍā, (Ḍ.) ōḍa id. Kur. ēṛā she-goat. Malt. éṛeid. Br. hēṭ id. / Cf. Skt. eḍa-, eḍaka-, eḍī- a kind of sheep; Turner, CDIAL, no. 2512.

1) mēṇḍha (p. 596) 10310 mēṇḍha2 m. ʻram ʼ, ˚aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4, miṇḍha -- 2, ˚aka -- , mēṭha -- 2, mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2, ˚aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ]1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻram ʼ, ˚aka -- ʻmade of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (˚ḍhī -- f.), ˚ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (˚dhiā -- f.), ˚aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇKal.rumb. amŕn/aŕə ʻsheep ʼ(a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻmarkhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*ll ʻram ʼAO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻram ʼ, miṇḍṓl m. ʻyearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m., ˚ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho, meṛo ʻram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāg ʻram ʼ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., ˚ṛi f., Or. meṇḍhā, ˚ḍā m., ˚ḍhi f., H. meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M. mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā.2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻsheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻram ʼ.*mēṇḍharūpa -- , mēḍhraśr̥ṅgī -- .Addenda: mēṇḍha -- 2: A. also mer (phonet. mer) ʻram ʼAFD 235. 10311 *mēṇḍharūpa ʻlike a ram ʼ. [mēṇḍha -- 2, rūpá -- ] Bi. mẽṛhwā ʻa bullock with curved horns like a ram's ʼ; M. mẽḍhrū̃ n. ʻsheep ʼ. 10312 *mēṇḍhī ʻlock of hair, curl ʼ. [Cf. *mēṇḍha -- 1 s.v. *miḍḍa -- ]S. mī˜ḍhī f., ˚ḍho m. ʻbraid in a woman's hair ʼ, L. mē̃ḍhī f.; G. mĩḍlɔ, miḍ˚ m. ʻbraid of hair on a girl's forehead ʼ; M. meḍhā m. ʻcurl, snarl, twist or tangle in cord or thread ʼ.

10323 mḗdas n. ʻfat, marrow ʼ RV., mēda -- m. ʻfat ʼR.Pa. mēda -- n. ʻfat ʼ, Pk. mēa -- m.n.; Wg. muī ʻmarrow ʼ; Shum. mīˊə̃ ʻfat of an animal ʼ; Kal.rumb. meh, urt. me_ sb. ʻfat ʼ; Bshk. ãdotdot; m. ʻ fat ʼ, muyū ʻbrain ʼ; Tor. (Biddulph) mih f. ʻfat ʼ, mīm f. ʻbrain ʼ(< *mẽ AO viii 306); Sv. mī m. ʻfat, marrow ʼ; Phal. mī m. ʻmarrow ʼ; Sh. mī˜ f. ʻfat ʼ, (Lor.) mī f. ʻfat ʼ, miyo ʻmarrow ʼ.

10327 mḗdha m. ʻsacrificial oblation ʼ RV.Pa. mēdha -- m. ʻsacrifice ʼ; Si. mehe, mē sb. ʻeating

10327a †mḗdhya -- ʻfull of vigour ʼ AV., ʻ fit for sacrifice ʼBr. [mḗdha -- m. or mēdhāˊ -- f. ʻmental vigour ʼ RV.]Pa. mejjha -- ʻpure ʼ, Pk. mejjha -- , mijjha -- ; A. mezi ʻ a stack of straw for ceremonial burning ʼ.

Pictograph boar: barāh, baḍhi 'boar' vāḍhī, bari, barea 'merchant' bārakaśa 'seafaring vessel'.

वाडकर vāḍakara m (वाडी &38; कर) The lord or proprietor of a वाडी or enclosed piece of ground. 2 also वाडकरी m An inhabitant of a वाडी, a hamleteer.; वाड vāḍa f Room, vacancy, free or unfilled space: also leisure, free or unengaged time.वाडकुलें vāḍakulēṃ n C (Dim. of वाडी) A small houseyard.वाडगें vāḍagēṃ n (Dim. of वाडी) A small yard or enclosure (esp. around a ruined house or where there is no house).वाडवडील vāḍavaḍīla m pl (वडीलby redup.) Ancestors, forefathers, elders, ancients.वाडा vāḍā m (वाटor वाटीS) A stately or large edifice, a mansion, a palace. Also in comp. as राज- वाडाA royal edifice; सरकारवाडा Any large and public building. 2 A division of a town, a quarter, a ward. Also in comp. as देऊळवाडा, ब्राह्मण- वाडा, गौळीवाडा, चांभारवाडा, कुंभारवाडा. 3 A division (separate portion) of a मौजा or village. The वाडा, as well as the कोंड, paid revenue formerly, not to the सरकारbut to the मौजेखोत. 4 An enclosed space; a yard, a compound. 5 A pen or fold; as गुरांचावाडा, गौळवाडा or गवळीवाडा, धन- गरवाडा. The pen is whether an uncovered enclosure in a field or a hovel sheltering both beastsवाडी vāḍī f (वाटी S) An enclosed piece of meaand keepers. dow-field or garden-ground; an enclosure, a close, a paddock, a pingle. 2 A cluster of huts of agriculturists, a hamlet. Hence (as the villages of the Konkan̤ are mostly composed of distinct clusters of houses) a distinct portion of a straggling village. 3 A division of the suburban portion of a city.वांडें vāṇḍēṃ n (वाणिज्यS) A stock of merchandise or goods; a quantity brought to market. वांड्याचेंवांडेंA whole investment. वाड्या vāḍyā m C (वाडी) A proprietor of hamlets, or enclosures, or tenements.वडील vaḍīla a (वृद्धS) An ancestor. 2 A senior or an elder; an elderly person. 3 A superior (in age, wisdom, dignity). 4 Applied, by way of eminence, to one's father. व0 उद्धरणेंg. of o. To curse or abuse the ancestors of.वडीलघराणें vaḍīlagharāṇēṃ n or -घराणाm An elder household; the house of the eldest or of an elder of the family. वडीलधारा vaḍīladhārā m वडीलधारेंn (Elder and younger.) A person of a family (male or female) of whom it is the business to punish, repress, and keep the children in order. वडीलपरंपरा vaḍīlaparamparā f The line of one's ancestors or elders. वडीलपरंपरागत vaḍīlaparamparāgata a Come by descent through a line of ancestors. वडीलमान vaḍīlamāna m A due of the elder; any ancestral right or privilege. Ex. होळीपोळीचाव0 मुकद्दमाकडेआहे. वढील vaḍhīla & compounds R Commonly वडील&c. (Marathi)

vāṭa1 m. ʻenclosure, fence ʼ MBh., vāṭī -- f. ʻenclosed land ʼ BhP., vāṭikā -- f. ʻenclosure, garden ʼ Kathās. [Early east MIA. < *vārtra -- . -- √vr̥1].Pa. vāṭa -- , ˚aka -- m. ʻenclosure, circle ʼ; Pk. vāḍa -- , ˚aga -- m. ʻfence ʼ, vāḍī -- , ˚ḍiā -- f. ʻfence, garden ʼ; Gy. eng. bor ʻhedge ʼ, germ. bār ʻgarden ʼ, gr. bári, hung. bar, pl. barya; Dm. byeŕ, byäˊŕu ʻcattle -- fold ʼ; Paš.weg. waṛ ʻwall ʼ; Phal. bāṛ ʻgoat -- pen ʼ (→ Gaw. bāḍ ʻfence, sheepfold ʼ; Paš.weg. bāṛ ʻcow -- pen ʼ); Sh. (Lor.) bā ʻsheep -- or goat -- pen ʼ; K. wār (Islāmābād wāḍ) m. ʻhedge round garden ʼ, wôru m. ʻenclosed space, garden, cattle -- yard ʼ, wörü f. ʻgarden ʼ, kash. wajī ʻfield ʼ; S. vāṛo m. ʻcattleenclosure ʼ, vāṛi f. ʻfence, hedge ʼ, vāṛī f. ʻfield of vegetables ʼ; L. vāṛ f. ʻfence ʼ, vāṛā m. ʻcattle -- or sheepfold ʼ, vāṛī f. ʻsheepfold, melon patch ʼ; P. vāṛ, bāṛ f. ʻfence ʼ, vāṛā, bā˚ m. ʻenclosure, sheepfold ʼ, vāṛī, bā˚ f. ʻgarden ʼ; WPah.bhal. bāṛi f. ʻwrestling match enclosure ʼ, cam. bāṛī ʻgarden ʼ; Ku. bāṛ ʻfence ʼ(whence bāṛṇo ʻto fence ʼ), bāṛo ʻfield near house ʼ, bāṛī ʻgarden ʼ; N. bār ʻhedge, boundary of field ʼ, bāri ʻgarden ʼ; A. bār ʻwall of house ʼ, bāri ʻgarden ʼ; B. bāṛ ʻedge, border, selvedge of cloth ʼ, bāṛi ʻgarden ʼ; Or. bāṛa ʻfence ʼ, bāṛā ʻfence, side wall ʼ, bāṛi ʻland adjoining house ʼ; Bi. bāṛī ʻgarden land ʼ; Mth. bāṛī ʻground round house ʼ, (SBhagalpur) bārī ʻfield ʼ; Bhoj. bārī ʻgarden ʼ; OAw. bāra m. ʻobstruction ʼ, bārī f. ʻgarden ʼ; H. bāṛ f. ʻfence, hedge, line ʼ, bāṛā m. ʻenclosure ʼ, bāṛī f. ʻenclosure, garden ʼ; Marw. bāṛī f. ʻgarden ʼ; G. vāṛ f. ʻfence ʼ, vāṛɔ m. ʻenclosure, courtyard ʼ, vāṛī f. ʻgarden ʼ; M. vāḍ f. ʻfence ʼ, vāḍā m. ʻquarter of a town ʼ ( -- vāḍẽ in names of places LM 405), vāḍī f. ʻgarden ʼ; Ko. vāḍo ʻhabitation ʼ; Si. vel -- a ʻfield ʼ(or < vēla -- ).*āvāṭa -- 2, *parivāṭa -- ; akṣavāṭa -- , *agravāṭa -- , *ajavāṭa -- , *avivāṭa -- , *ikṣuvāṭa -- , kāṣṭhavāṭa -- , *kṣapitavāṭa -- , *khalavāṭa -- , gr̥havāṭī -- , gōvāṭa -- , cakravāṭa -- , *jīvavāṭī -- , *dhēnuvāṭa -- , *parṇavāṭikā -- , *paścavāṭa -- , *prākāravāṭa -- , *phullavāṭikā -- , *bījadhānyavāṭī -- , *bījavāṭī -- , *bhājyavāṭa -- , *rasavāṭa -- , *rājyavāṭa -- , *vaṁśavāṭa -- .Addenda: vāṭa -- 1 [Perhaps < *vārta -- < IE. *worto -- rather than < *vārtra -- T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 68]WPah.kṭg. bāṛ m. ʻfence, pen for sheep, goats, calves in bottom storey ʼ, baṛɔ m. ʻpen for cattle, grain store, fence ʼ, baṛnõ ʻto fence in, build a nest ʼ, báṛhnõ ʻto become a bar, to force oneself in, be fenced ʼ; poet. baṛən f. ʻfence, railing ʼ, baṛne f.

†*paśuvāṭa -- , †*bhēḍravāṭa -- , †*vāsavāṭī -- .(CDIAL 11480) *bhēḍravāṭa -- ʻsheepfold ʼ. [bhēḍra -- , vāṭa -- 1]WPah.kc. bərhaṛo n. ʻstorey in house where sheep and goats are kept ʼ, kṭg. bəṛhε̄`ḷ m. id. (< *bhēḍrīvāṭa -- ?), bəṛhāˋḷ m. ʻ sheep shed ʼ Him.I 151, 152.(CDIAL 9608a).*bhēḍravr̥ti -- ʻsheepfold ʼ. [bhēḍra -- , vr̥ti -- ]*bhēḍrakuṭikā ʻsheepfold ʼ. [bhēḍra -- , kuṭī -- ]WPah.cam. bhaṛōṛī or < *bhēḍravr̥ti -- .(CDIAL 9607)

पारिणामिक pâri-nâm-ika digestible; subject to development: with -shada, m. member of an assembly or council, auditor, spectator: pl. retinue of a god; -shad-ya, m. one who takes part in an assembly, spectator

On the hieroglyph with 'fish' on the chest of Sheorajpur anthropomorph, focus on (Embedded with a 'fish' hieroglyph on the chest); spread legs -- कर्णक m. du. the two legs spread out AV. xx , 133 'spread legs'; (semantic determinant) Rebus: kanahār'helmsman', karNI 'scribe, account''supercargo'. कर्णक'spread legs' rebus: 'helmsman', karNi 'supercargo' PLUS aya 'fish' rebus: ayas 'alloy metal'. Thus, supercargo/helmsman engaged in alloy metal work.

Hieroglyph: M. mẽḍhā m. ʻ crook or curved end (of a horn, stick, &c.) ʼ *miḍḍa ʻ defective ʼ. 2. *miṇḍa -- . 3. *miṇḍha -- 1. 4. *mēṭṭa -- 1. 5. *mēṇḍa -- 1. 6. *mēṇḍha -- 1. [Cf. *mitta -- and list s.v. *maṭṭa -- ; --mḗṭati, mḗḍati ʻ is mad ʼ Dhātup. -- Cf. *mēṭṭa -- 2 ʻ lump ʼ]1. G. miḍiyɔ ʻ having horns bent over forehead (of oxen and goats) ʼ.2. G. mī˜ḍũ ʻ having rims turned over ʼ.3. S. miṇḍhiṇo ʻ silent and stupid in appearance but really treacherous and cunning ʼ; G. miṇḍhũ ʻ having deep -- laid plans, crafty, conceited ʼ.4. A. meṭā ʻ slow in work, heavy -- bodied ʼ.5. Or. meṇḍa ʻ foolish ʼ; H. mẽṛā, mẽḍā m. ʻ ram with curling horns ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ she -- goat do. ʼ.6. Or. meṇḍha ʻ foolish ʼ, °ḍhā ʻ fool ʼ; M. mẽḍhā m. ʻ crook or curved end (of a horn, stick, &c.) ʼ.(CDIAL 10120) mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4, miṇḍha -- 2, °aka -- , mēṭha -- 2, mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2, °aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ] 1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (°ḍhī -- f.), °ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (°dhiā -- f.), °aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇ Kal.rumb. amŕn/aŕə ʻ sheep ʼ (a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻ ram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*ll ʻ ram ʼ AO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍṓl m. ʻ yearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m., °ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho, meṛo ʻ ram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāgʻ ram ʼ ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., °ṛi f., Or. meṇḍhā, °ḍā m., °ḍhi f., H. meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M. mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā. 2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ. 3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ. *mēṇḍharūpa -- , mēḍhraśr̥ṅgī -- . Addenda: mēṇḍha -- 2: A. also mer (phonet. mer) ʻ ram ʼ (CDIAL 10310)

Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati)

Thus, the anthropomorphs of Sarasvati Civilization are professional calling cards of artificers and merchants of metalwork.

The freestanding sandstone carving, 2.5m long is of the boar Varāha. All the sculptural friezes on the body of the boar are carvd out of a single piece of rock. There are over 674 miniature sculptural friezes of divinities and scholars, organized in 12 rows, depicting devatā-s from R̥gveda. Devi Sarasvati adorns the snout, cashAla. This cashAla signifies the wheat chaff ring atop the yupa which is set on fire and its godhuma fumes enter the molten metal to harden it, to convert iron into steel by infusion of carbon as an additional element. This is metallurgy par excellence of Sarasvati-Vaigai Civilization.

Hieroglyph: चषाल n. the snout of a boar or hog MaitrS. i , 6 , 3.

Hieroglyph: चषाल n. the snout of a boar or hog MaitrS. i , 6 , 3.

Rebus: चषाल mn. (g. अर्धर्चा*दि) a wooden ring on the top of a sacrificial post RV. i , 162 , 6 TS. vi Ka1t2h. xxvi , 4 (चशाल) S3Br. &c

Sarasvati on the चषाल'snout of varāha'.signifies a knowledge system to produce metalwork wealth.

Citragupta (चित्रगुप्त) is the name of a deity representing the secretary of the divinities, according to the Kathāsaritsāgara, chapter 72. Citragupta (Sanskrit: चित्रगुप्त, 'rich in secrets' or 'hidden picture') is a Hindu divinity assigned with the task of keeping complete records of actions of human beings on the earth.

That the varāha temple is called Citragupta temple is significant. Citragupta is the divine accountant who maintains wealth accounting ledgers of a nation.

Like the artificers of Sarasvati Civilization, Kīr̤aḍi artificers are workers with furnaces and with ivory objects.

Oslo Museum. Unprovenanced cylinder seal (from Afghanistan?)

baḍhoe‘a carpenter, worker in wood, iron’; badhoria‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar' Rebus: bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [ bārakaśa or bārakasa ] n ( P) A trading vessel, a merchantman.

kamaḍha'archer' Rebus: kammaṭa'mint, coiner, coinage'

kola'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'kolhe'smelter'kolle'blacksmith'

baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi 'a caste who work both in iron and wood' వడ్రంగి, వడ్లంగి, వడ్లవాడు (p. 1126) vaḍraṅgi, vaḍlaṅgi, vaḍlavāḍu or వడ్లబత్తుడు vaḍrangi. [Tel.] n. A carpenter. వడ్రంగము, వడ్లపని, వడ్రము or వడ్లంగితనము vaḍrangamu. n. The trade of a carpenter. వడ్లవానివృత్తి. వడ్రంగిపని. వడ్రంగిపిట్ట or వడ్లంగిపిట్ట vaḍrangi-piṭṭa. n. A woodpecker. దార్వాఘాటము. వడ్లకంకణము vaḍla-kankaṇamu. n. A curlew. ఉల్లంకులలోభేదము. వడ్లత or వడ్లది vaḍlata. n. A woman of the carpenter caste. vardhaki m. ʻ carpenter ʼ MBh. [√vardh] Pa. vaḍḍhaki -- m. ʻ carpenter, building mason ʼ; Pk. vaḍḍhaï -- m. ʻ carpenter ʼ, °aïa -- m. ʻ shoemaker ʼ; WPah. jaun. bāḍhōī ʻ carpenter ʼ, (Joshi) bāḍhi m., N. baṛhaï, baṛahi, A. bārai, B. bāṛaï, °ṛui, Or. baṛhaï, °ṛhāi, (Gaṛjād) bāṛhoi, Bi. baṛahī, Bhoj. H. baṛhaī m., M. vāḍhāyā m., Si. vaḍu -- vā.(CDIAL 11375)

baḍaga is a takṣa, divine tvaṣṭr̥ of R̥gveda, he is a yajña puruṣa as evidenced in Khajuraho monumental varāha sculpture.. He is the very embodiment of the Veda, Veda puruṣa. त्वष्टृ m. a carpenter , maker of carriages (= त्/अष्टृ) AV. xii , 3 , 33; " creator of living beings " , the heavenly builder , N. of a god (called सु-क्/ऋत् , -पाण्/इ , -ग्/अभस्ति , -ज्/अनिमन् , स्व्-/अपस् , अप्/असाम्अप्/अस्तम , विश्व्/अ-रूप &c RV. ; maker of divine implements , esp. of इन्द्र's thunderbolt and teacher of the ऋभुs i , iv-vi , x Hariv. 12146 f. R. ii , 91 , 12 ; former of the bodies of men and animals , hence called " firstborn " and invoked for the sake of offspring , esp. in the आप्री hymns RV. AV. &c MBh. iv , 1178 Hariv. 587 ff. Ragh. vi , 32 ; associated with the similar deities धातृ , सवितृ , प्रजा-पति , पूषन् , and surrounded by divine females [ग्न्/आस् , जन्/अयस् , देव्/आनाम्प्/अत्नीस् ; cf. त्व्/अष्टा-व्/अरूत्री] recipients of his generative energy RV. S3Br. i Ka1tyS3r. iii ; supposed author of RV. x , 184 with the epithet गर्भ-पति RAnukr. ; father of सरण्यू [सु-रेणु Hariv.; स्व-रेणु L. ] whose double twin-children by विवस्वत् [or वायु ? RV. viii , 26 , 21 f.] are यमयमी and the अश्विन्s x , 17 , 1 f. Nir. xii , 10 Br2ih. Hariv.545 ff. VP. ; also father of त्रि-शिरस् or विश्वरूप ib. ; overpowered by इन्द्र who recovers the सोम [ RV. iii f. ] concealed by him because इन्द्र had killed his son विश्व-रूप TS. ii S3Br. i , v , xii ; regent of the नक्षत्र चित्रा TBr. S3a1n3khGr2. S3a1ntik. VarBr2S. iic , 4 ; of the 5th cycle of Jupiter viii , 23 ; of an eclipse iii , 6 ; त्वष्टुर्आतिथ्य N. of a सामन् A1rshBr. ).

Text of inscription:

Sign 121 70 Read as a variant of Sign 112: Four count, three times: gaṇḍa 'four' rebus: kaṇḍa 'fire-altar' khaṇḍa 'implements, metalware' PLUS

||| Number three reads: kolom 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. Thus,the hypertext of Sign 104 reads: kolami khaṇḍa 'smithy/forge (for) implements.'

Duplicated 'bows', Variant of Sign 307

Sign 307 69 Arrow PLUS bow: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023). ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) Rebus: khaṇḍa, khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. kanda 'fire-altar' PLUS kamaṭha m. ʻ bamboo ʼ lex. 2. *kāmaṭha -- . 3. *kāmāṭṭha -- . 4. *kammaṭha -- . 5. *kammaṭṭha -- . 6. *kambāṭha -- . 7. *kambiṭṭha -- . [Cf. kambi -- ʻ shoot of bamboo ʼ, kārmuka -- 2 n. ʻ bow ʼ Mn., ʻ bamboo ʼ lex. which may therefore belong here rather than to kr̥múka -- . Certainly ← Austro -- as. PMWS 33 with lit. -- See kāca -- 3] 1. Pk. kamaḍha -- , °aya -- m. ʻ bamboo ʼ; Bhoj. kōro ʻ bamboo poles ʼ.2. N. kāmro ʻ bamboo, lath, piece of wood ʼ, OAw. kāṁvari ʻ bamboo pole with slings at each end for carrying things ʼ, H. kã̄waṛ, °ar, kāwaṛ, °ar f., G. kāvaṛ f., M. kāvaḍ f.; -- deriv. Pk. kāvaḍia -- , kavvāḍia -- m. ʻ one who carries a yoke ʼ, H. kã̄waṛī, °ṛiyā m., G. kāvaṛiyɔ m.3. S. kāvāṭhī f. ʻ carrying pole ʼ, kāvāṭhyo m. ʻ the man who carries it ʼ.4. Or. kāmaṛā, °muṛā ʻ rafters of a thatched house ʼ;G. kāmṛũ n., °ṛī f. ʻ chip of bamboo ʼ, kāmaṛ -- koṭiyũ n. ʻ bamboo hut ʼ. 5. B. kāmṭhā ʻ bow ʼ, G. kāmṭhũ n., °ṭhī f. ʻ bow ʼ; M. kamṭhā, °ṭā m. ʻ bow of bamboo or horn ʼ; -- deriv. G. kāmṭhiyɔ m. ʻ archer ʼ. 6. A. kabāri ʻ flat piece of bamboo used in smoothing an earthen image ʼ.7. M. kã̄bīṭ, °baṭ, °bṭī, kāmīṭ, °maṭ, °mṭī, kāmṭhī, kāmāṭhī f. ʻ split piece of bamboo &c., lath ʼ.(CDIAL 2760)This evokes another word: kamaḍha 'archer' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner' . Thus, Sign 307 is read as bow and arrow rebus: khaṇḍa kammaṭa 'equipment mint' (See Sign 281)Thus, kã̄bīṭ 'bow' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting', i.e. dul kammaṭa 'metalcasting mint'

This is a hypertext composed of 'body' (of standing person)

Sign 1 hieroglyph: meḍ 'body' rebus: meḍ,med'iron, copper'

'lid' hieroglyph: ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article'.

Sign 402 'flag' hieroglyph. Sign 402 'flag' hieroglyph. Ciphertext koḍi ‘flag’ (Ta.)(DEDR 2049). In the context of metalwork guilds, the flag is the compound expression: dhvajapaṭa ʻflagʼ PLUS dhvajapaṭa

m. ʻ flag ʼ Kāv. [dhvajá -- , paṭa -- ]Pk. dhayavaḍa -- m. ʻ flag ʼ, OG. dhayavaḍa m. Rebus: Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic (CDIAL 6773)

The hypertext reads: kolami khaṇḍa dhakka meḍ dhā̆vaḍ ' smithy/forge equipment, smelter producing blazing, bright iron'.

Sign 211 kaṇḍa ‘arrow’; Rebus: kaṇḍ = a furnace, altar (Santali) khaṇḍa 'implements' (Santali)

The inscription reads:

kol badhoe kammaṭa kolami khaṇḍa dhakka meḍ dhā̆vaḍ

'working in iron, wood, mint, smithy.forge equipment, smelter producing blazing iron implements.'

Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr seal; ca. 3200-3000 BCE; serpentine; cat.1; boar and bull in procession; terminal: plant; heavily pitted surface beyond plant. Indus Script hieroglyphs read rebus: baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi ‘a caste who work both in iron and wood’ Hieroglyph: dhangar 'bull' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar'Rebus: bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [ bārakaśa or bārakasa ] n ( P) A trading vessel, a merchantman (cargo boat).

Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr seal; ca. 3200-3000 BCE; serpentine; cat.1; boar and bull in procession; terminal: plant; heavily pitted surface beyond plant. Indus Script hieroglyphs read rebus: baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi ‘a caste who work both in iron and wood’ Hieroglyph: dhangar 'bull' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar'Rebus: bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [ bārakaśa or bārakasa ] n ( P) A trading vessel, a merchantman (cargo boat).

Indus Script Hieroglyph: barāh, baḍhi ‘boar’ Rebus: vāḍhī, bari, barea ‘merchant’

baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’ Together with an anthropomorph of copper/bronze with the curved horns of a ‘ram’, the hypertext signifies: meḍh ‘ram’ rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ PLUS baḍhi ‘boar’ rebus: baḍhoria, ‘expert in working in wood’PLUS khondar‘young bull’ rebus: konda ‘furnace’ kundaṇa ‘fine gold’ Thus, the anthropomorph is a professional calling card of a worker with furnace, worker in iron, fine gold and wood. It is not mere coincidence that Varāha signifies an ancient gold coin. Another anthropomorph rplaces the young bull frieze on the chest of the ram with a ‘fish’ hieroglyph. ayo ‘fish’ rebus: aya ‘iron’ ayas ‘alloy metal’.

Boar

oḍ m. ʻ a caste of Hindus who dig and carry earth and build mud houses ʼ(Gujarati)(CDIAL 2549).This etymon is relatable to baḍhi,bāṛaï 'carpenter', baṛea 'worker in wood and iron; merchant' signified by the hieroglyph: baḍhia,বরাহ barāha 'boar', In Telugu, the pronunciation variant is వడ్రంగి, వడ్లంగి, వడ్లవాడు (p. 1133) [ vaḍraṅgi, vaḍlaṅgi, vaḍlavāḍu ] or వడ్లబత్తుడు vaḍrangi. [Tel.] n. A carpenter. Cf. vardhaki ‘carpenter’ (Samskrtam) The semantics of 'digging' indicate the possibility that baḍhi,bāṛaï was also a miner digging out minerals from the earth and hence the association in the metaphors related to Bhudevi and her rescue from the ocean.

বরাহ barāha 'boar' Indus Script hieroglyph on Ancient Near East artifacts; significance of supercargo on a seafaring cargo boat

Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/gvxn2un

A boar as an artistic signifier of professional titles of the Bronze Age occurs on a Jemdet Nasr seal impression ca. 3200-3000 BCE. On this seal, kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' is followed by badhi 'boar' rebus: badhi 'carpenter, worker in iron' and dhangar 'bull' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'. baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar'Rebus: bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [ bārakaśa or bārakasa ] n ( P) A trading vessel, a merchantman.

.Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr seal; ca. 3200-3000 BCE; serpentine; cat.1; boar and bull in procession; terminal: plant; heavily pitted surface beyond plant. Indus Script hieroglyphs read rebus: baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi ‘a caste who work both in iron and wood’ Hieroglyph: dhangar 'bull' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar'Rebus: bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [ bārakaśa or bārakasa ] n ( P) A trading vessel, a merchantman (cargo boat).

Gold sheet and silver, Late 3rd/early 2nd millennium B.C.E.

L. 12.68 cm. Ceremonial Axe Bactria,Northern Afghanistan http://www.lessingimages.com/search.asp?a=L&lc=202020207EE6&ln=Collection+George+Ortiz%2C+Geneva%2C+Switzerland&p=1 "The whole cast by the lost wax process. The boar covered with a sheet of gold annealed and hammered on, some 3/10-6/10 mm in thickness, almost all the joins covered up with silver. At the base of the mane between the shoulders an oval motif with irregular indents. The lion and the boar hammered, elaborately chased and polished. A shaft opening - 22 holes around its edge laced with gold wire some 7/10-8/10 mm in diameter - centred under the lion's shoulder; between these a hole (diam: some 6.5 mm) front and back for insertion of a dowel to hold the shaft in place, both now missing.

Ceremonial axe (inscribed with name) of king Untash-Napirisha, from his capital Tchoga Zambil. Back of the axe adorned with an electrum boar; the blade issues from a lion's mouth. Silver and electrum, H: 5,9 cm Sb 3973 Louvre, Departement des Antiquites Orientales, Paris, France

Cast axe-head; tin bronze inlaid with silver; shows a boar attacking a tiger which is attacking an ibex.ca. 2500 -2000 BCE Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. Length: 17.8 cm (7 in). Weight: 675.5 g (23.82 oz). British Museum.ME 123628 (1913,0314.11913,0314.1) R. Maxwell-Hyslop, 'British Museum “axe” no. 123628: a Bactrian bronze', Bulletin of the Asia Institute, NS I (1987), pp. 17-26

Curator's comments: See RL file 6616 (29/6/1995); also Research Lab file 4992 of 12/09/1983 where XRF analysis of surface indicates composition as tin bronze with approx 10% tin and traces of arsenic, nickel, silver and lead. Dalton's inclusion in the 'Catalogue of the Oxus Treasure' among a small group of comparative items has unfortunately led to recurrent confusion over the date and provenance of this piece. It was first believed to be Achaemenid in date (Dalton, 'Catalogue of the Oxus Treasure', p. 48), labelled as such in 1975 in the former Iranian Room and thus suggested to be an Achaemenid scabbard chape (P R S Moorey CORRES 1975, based on an example said to have been excavated by P. Bernard at Ai Khanoum or seen by him in Kabul Bazaar, cf. P. Bernard CORRES 1976). It has also been assigned a 4th-5th century AD Sasanian date (P. Amiet, 1967, in 'Revue du Louvre' 17, pp. 281-82). However, its considerably earlier - late 3rd mill. BC Bronze Age - date has now been clearly demonstrated following the discovery of large numbers of objects of related form in south-east Iran and Bactria, and it has since been recognised and/or cited as such, for instance by H. Pittmann (hence archaeometallurgical analysis in 1983; R. Maxwell-Hyslop, 1988a, "British Museum axe no. 123628: a Bactrian bronze", 'Bulletin of the Asia Institute' 1 (NS), pp. 17-26; F. Hiebert & C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky 1992a, "Central Asia and the Indo-Iranian Borderlands",' Iran' 30, p. 5; B. Brentjes, 1991a, "Ein tierkampfszene in bronze", 'Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran' 24 (NS), p. 1, taf. 1).

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=367862&partId=1

Decipherment: There are three hieroglyphs: ram (markhor), tiger, boar. The rebus renderings are: coppersmith (merchant's helper), smelter, worker in wood and iron.

Tor. miṇḍ 'ram', miṇḍā́l 'markhor' (CDIAL 10310) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) Thus, coppersmith, helper of merchant.

kola 'tiger' rebus: kolle 'blacksmith', kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'. Thus, a smelter.

badhi 'boar' rebus: badhi 'carpenter, worker in iron' and dhangar 'bull' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'. baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar'Rebus: bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [ bārakaśa or bārakasa ] n ( P) A trading vessel, a merchantman.

![]() Shaft-hole axe head double-headed eagle anthropomorph, boar, and winged tiger ca. late 3rd–early 2nd millennium B.C.E Silver, gold foil L. 15 cm.

Shaft-hole axe head double-headed eagle anthropomorph, boar, and winged tiger ca. late 3rd–early 2nd millennium B.C.E Silver, gold foil L. 15 cm.

Anthropomorph (human body) is represented twice, once on each side of the axe, and consequently appears to have two heads. On one side, he grasps the boar by the belly and on the other, by the tusks.

The composite animal (feline, tiger body) has folded and staggered wings, and the talons of a bird of prey in the place of his front paws. Its single horn has been broken off and lost.

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/329076

Rebus readings are: eruvai 'kite' rebus: eruvai 'copper' PLUS kambha 'shoulder, wing' rebus: kammaTa 'mint'; thus, copper mint.

kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' PLUS kambha 'wing' rebus: kammaTa 'min'; thus, iron smelter's mint.

badhi 'boar' rebus: badhi 'carpenter, worker in iron' and dhangar 'bull' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'. baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar'Rebus: bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [ bārakaśa or bārakasa ] n ( P) A trading vessel, a merchantman.

The hieroglyph-multiplexes on Ancient Near East artifacts include hieroglyph components: tiger, rhinoceros, eagle, kid (goat), bull/ox. All are metalwork cipher texts. These are in addition to a boar: বরাহ barāha 'boar' Rebus: bāṛaï

'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [ bārakaśa or bārakasa ] n ( P) A trading vessel, a merchantman. The dominant role played by the merchantman vessel steered by a helmsman explains the presence of a pair of boars on one of the frames of hieroglyph-multiplexes on the Gundestrup Cauldron:

Vessel in the form of a boar

Period:

Proto-Elamite

Date:

ca. 3100–2900 B.C.

Geography:

Southwestern Iran

Culture:

Proto-Elamite

Medium:

Ceramic, paint

Dimensions:

5.71 in. (14.5 cm)

Classification:

Ceramics-Vessels

Credit Line:

Purchase, Rogers Fund and Anonymous Gift, 1979

Accession Number:

"Arjuna said, 'How did Agni and Soma, in days of yore, attain to uniformity in respect of their original nature? This doubt has arisen in my mind. Do thou dispel it, O slayer of Madhu!'...

Krishna tells Arjuna: "Assuming, in days of old, the form of a boar with a single tusk, O enhancer of the joys of others, I raised the submerged Earth from the bottom of the ocean. From this reason am I called by the name of Ekasringa. While I assumed the form of mighty boar for this purpose, I had three humps on my back. Indeed, in consequence of this peculiarity of my form at that time that I have come to be called by the name of Trikakud (three-humped)." (Section CCCXLIII Mahabharata, Rajadharmanusasana Parva in Santi Parva Part I, Kisari Mohan Ganguli tr. http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m12/m12c042.htm)

.com/

Tablet Sb04823: receipt of 5 workers(?) and their monthly(?) rations, with subscript and seal depicting animal in boat; excavated at Susa in the early 20th century; Louvre Museum, Paris (Image courtesy of Dr Jacob L. Dahl, University of Oxford) Cited in an article on Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) System. The animal in boat may be a boar and may signify supercargo of wood and iron products. baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi ‘a caste who work both in iron and wood’.