https://tinyurl.com/yymotso8

-- Decipherment of Shu-ilishu cylinder seal & Trade interactions between Meluhha & Mesopotamia

How did the brahma 'hymn' R̥gveda r̥ca RV 3.53.12 of viśvāmitra protect bhārataṃ janam?I submit that this is a metaphor for the enquiry into knowledge systems which made bhārataṃ janam, the Meluhha people of Meluhha nation (Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization Area) the richest nation on the globe, from the days of the Neolithic Revolution, 9000 to 6500 BCE and the Tin-Bronze Revolution from 7th m. BCE?

R̥gveda r̥ca RV 3.53.12 is rendered in पद--पाठ which is a method of arranging each word of a Vedic text separately in its original form [cf. पद] without regard to the rules of संधि ; cf. क्रम and संहिता-पाठ.

| दे. इन्द्रः, १ इन्द्रापर्वतौ, १५, १६ वाक् (ससर्परी), १७-२० रथाङ्गानि, २१-२४ अभिशापः। |

This monograph is organized in two sections to signify Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization Trade Centres:

Section 1. Decipherment of Shu-ilishu cylinder seal in Indus Script with Cuneiform text

Section 2. Evidence for & significance of trade transactions between Meluhha and Mesopotamia

Meluhha was the Akkadian name for Indus Sarasvati Valleys. Early texts (c. 2200 BCE) seem to indicate that Meluhha is to the east, suggesting either the Indus valley or India. However, much later texts documenting the exploits of King Assurbanipal of Assyria (668–627 BCE), long after the Indus Valley civilization had ceased to exist, seem to imply that Meluhha is to be found either in south India or in Africa, somewhere near Egypt.(Hansman, John (1973). "A "Periplus" of Magan and Meluhha". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 36 (3): 554–587.)

Section 1. Decipherment of Shu-ilishu cylinder seal in Indus Script with Cuneiform text

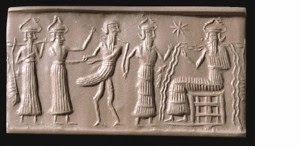

--Indus Script & cuneiform text on cylinder seal of Shu-ilishu, interpreter of the language of Meluhha country (Sarasvati Sindhu Civilization)

-- Shu-ilishu cylinder seal is in bilingual cuneiform and Meluhha (Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization) Indus Script

1. cuneiform script is a syllabic text which details the owner of the seal who is an interpreter of Meluhha language of Meluhha country;

2. Indus Script hieroglyphs are pictorial motifs of the two Meluhha traders who are Meluhha speakers.

Richelieu

Rez-de-chaussée

Mésopotamie, 2350 à 2000 avant J.-C. environ

Salle 228 Vitrine 1 : Glyptique de l'époque d'Akkad, 2340 - 2200 avant J.-C.

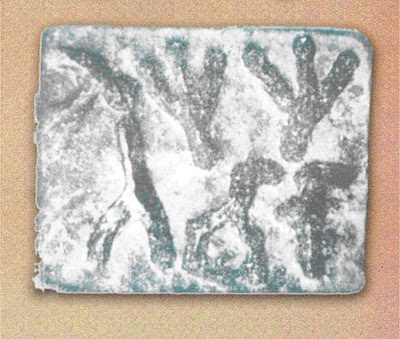

The Shu-ilishu cylinder seal is a clear evidence of the Meluhha merchants trading in copper and tin, signified by the field symbols vividly portrayed on the cylinder seal.

The Meluhha merchant/artificer carries melh, mr̤eka 'goat or antelope' rebus: milakkhu 'copper'; his right hand is raised: eraka 'upraised arm' rebus: eraka 'metal infusion'

The accompanying lady is also a Meluhha trader/artificer; she carries a ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin'. Thus, the pictorial motifs of the two traders signify that they are traders in copper and tin and work with 'metal infusion' (i.e., make cire perdue, lost-wax casting method bronze metal statues, pots and pans, metalware, metal equipment).

On the field is shown a crucbile:

kuṭhāru 'crucible' rebus: kuṭhāru 'armourer'. The seated person of high rank may be such a kuṭhāru 'armourer' signified by the hieroglyph kuṭhāru

'crucible' on the top register of the cylinder seal.

Thus, the cylinder seal signifies a trade transaction between a Mesopotamian armourer (Akkadian speaker) and Meluhhans settling a trade contract for their copper and tin. The transaction is mediated by Shu-ilishu, the Akkadian interpreter of Meluhha language.

Why bi-lingual seal? In the Akkadian court, Meluhhan language needed interpreters of the Meluhhan language; such interpreters resided in Mesopotamia.

The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris.

A Mesopotamian cylinder seal referring to the personal translator of the ancient Indus or Meluhan language, Shu-ilishu, who lived around 2020 BCE during the late Akkadian period. The late Dr. Gregory L. Possehl, a leading Indus scholar, tells the story of getting a fresh rollout of the seal during its visit to the Ancient Cities Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2004.

kuṭi 'tree' Rebus: kuṭhī 'smelter, warehouse, factory'

ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin ore'

Sumerian cylinder seal with two long-horned antelopes with a tree or bush in front, excavated in Kish, Mesopotamia.

Mackay, Ernest John Henry; Langdon, Stephen; Laufer, Berthold (1925). Report on the excavation of the "A" cemetery at Kish, Mesopotamia. Chicago : Field Museum of Natural History. p. 61 Nb.3.

[quote] Evidence for imports from the Indus to Ur can be found from around 2350 BCE. Various objects made with shell species that are characteristic of the Indus coast, particularly Trubinella Pyrum and Fasciolaria Trapezium, have been found in the archaeological sites of Mesopotamia dating from around 2500-2000 BCE. Carnelian beads from the Indus were found in Ur tombs dating to 2600–2450 BCE. In particular, carnelian beads with an etched design in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley, and made according to a technique of acid-etching developed by the Harappans. Lapis Lazuli was imported in great quantity by Egypt, and already used in many tombs of the Naqada II period (circa 3200 BCE). Lapis Lazuli probably originated in northern Afghanistan, as no other sources are known, and had to be transported across the Iranian plateau to Mesopotamia, and then Egypt.

Several Indus seals with Harappan script have also been found in Mesopotamia, particularly in Ur, Babylon, and Kish. (For a full list of discoveries of Indus seals in Mesopotamia, see Reade, Julian (2013). Indian Ocean In Antiquity. Routledge. pp. 148–152. For another list of Mesopotamian finds of Indus seals: Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 221."Indus stamp-seal found in Ur BM 122187". British Museum.

"Indus stamp-seal discovered in Ur BM 123208". British Museum.

"Indus stamp-seal discovered in Ur BM 120228". British Museum. Gadd, G. J. (1958). Seals of Ancient Indian style found at UrPodany, Amanda H. (2012). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press. p. 49. Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1. “

Square-shaped Indus seals of fired steatite have been found at a few sites in Mesopotamia”.)

The water buffalos which appears on the Akkadian cylinder seals from the time of Naram-Sin (circa 2250 BCE), may have been imported to Mesopotamia from the Indus as a result of trade"Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum". Louvre Museum. Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 187.

Akkadian Empire records mention timber, carnelian and ivory as being imported from Meluhha by Meluhhan ships, Meluhha being generally considered as the Mesopotamian name for the Indus Valley.

‘The ships from Meluhha, the ships from Magan, the ships from Dilmun, he made tie-up alongside the quay of Akkad’

— Inscription by Sargon of Akkad (ca.2270-2215 BCE)

After the collapse of the Akkadian Empire, Gudea, the ruler of Lagash, is recorded as having imported "translucent carnelian" from Meluhha. Various inscriptions also mention the presence of Meluhha traders and interpreters in Mesopotamia. About twenty seals have been found from the Akkadian and Ur III sites, that have connections with Harappa and often use Harappan symbols or writing.[unquote]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus%E2%80%93Mesopotamia_relations

“Sea levels have been rising about 100 meters over the last 15,000 years until modern times, with the effect that coast lines have been receding vastly. This is especially the case of the coast lines of the Indus and Mesopotamia, which were originally only separated by a distance of about 1000 kilometers, compared to 2000 kilometers today.[1] For the ancestors of the Sumerians, the distance between the coasts of the Mesopotamian area and the Indus area would have been much shorter than it is today. In particular the Persian Gulf, which is only about 30 meters deep today, would have been at least partially dry, and would have formed an extension of the Mesopotamian basin. The westernmost Harappan city was located on the Makran coast at Sutkagan Dor, near the tip of the Arabian peninsula, and is considered as an ancient maritime trading station, probably between India and the Persian Gulf.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus%E2%80%93Mesopotamia_relations

Global sea levels and vegetation during the Last Ice Age. The coastline was still roughly similar in about 10,000 BCE. It shouldbe noted that during the Last Ice Age, Greater India was a cultivable arable land area since 24 ft. ice cover was signifficant only on Europe. This ice cover would have prevented agricultural activities in Europe during the Last Ice Age c. 115,000 – c. 11,700 Before Present.

There are some seals with clear Indus themes among Dept. of Near Eastern Antiquities collections at the Louvre in Paris, France, among them the Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum, described as "one of the most striking examples of the perfection attained by carvers in the Agade period [2350–2170 BCE].

There are some seals with clear Indus themes among Dept. of Near Eastern Antiquities collections at the Louvre in Paris, France, among them the Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum, described as "one of the most striking examples of the perfection attained by carvers in the Agade period [2350–2170 BCE].

https://www.harappa.com/category/blog-subject/seals

Impression of a cylinder seal of the Akkadian Empire, with label: "The Divine Sharkalisharri Prince of Akkad, Ibni-Sharrum the Scribe his servant". The long-horned water buffalo depicted in the seal is thought to have come from the Indus Valley, and testifies to exchanges with Meluhha, the Indus Valley civilization. Circa 2217–2193 BCE. Louvre Museum, reference AO 22303.(Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 187.)

See: Ibni-Sharrum cylinder seal ca. 2200 BCE deciphered, Indus Script hypertext signifies artificer of zinc alloy furnace, metal implements https://tinyurl.com/y9l5hkn8

Ibni-Sharrum cylinder seal shows a kneeling person with six curls of hair.Cylinder seal of Ibni-sharrum, a scribe of Shar-kali-sharri (left) and impression (right), ca. 2183–2159 B.C.; Akkadian, reign of Shar-kali-sharri. Lower register signifies flow of water.

Numeral bhaṭa 'six' is an Indus Script cipher, rebus bhaṭa ‘furnace’; baṭa 'iron'. Rebus: bhaḍa -- m. ʻ soldier ʼ, bhuaga 'worshipper in a temple' (Note the worshipful pose of the person offering the overflowing pot).

bhr̥ta ʻ carried, brought ʼ MBh. 2. ʻ hired, paid ʼ Mn., m. ʻ hireling, mercenary ʼ Yājñ.com., bhr̥taka -- m. ʻ hired servant ʼ Mn.: > MIA. bhaṭa -- m. ʻ hired soldier, servant ʼ MBh. [√

- a solder or other alloy in which zinc is the main constituent.)

Cylinder seal impression of Ibni-sharrum, a scribe of Shar-kalisharri ca. 2183–2159 BCE The inscription reads “O divine Shar-kali-sharri, Ibni-sharrum the scribe is your servant.” Cylinder seal. Serpentine/Chlorite. AO 22303 H. 3.9 cm. Dia. 2.6 cm.

<lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. @B24310. #20851. Re<lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) Glyph of flowing water in the second register: காண்டம் kāṇṭam , n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர்; kāṇṭam ‘ewer, pot’ கமண்டலம். (Tamil) Thus the combined rebus reading: Ku. lokhaṛ ʻiron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ(CDIAL 11171). The kneeling person’s hairstyle has six curls. bhaṭa ‘six’; rebus: bhaṭa‘furnace’. मेढा mēḍhā A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl. (Marathi) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) Thus, the orthography denotes meḍ bhaṭa ‘iron furnace’.

Akkadian Cylinder Seal (c. 2200 B.C. showing Gilgamesh slaying the bull of heaven, with Enkidu? Also from Dury; both in British Museum)

Gilgamesh and Enkidu struggle of the celestial bull and the lion (cylinder seal-print Approx. 2,400 BC, Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore)

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1999.325.4 (Bos gaurus shown with greater clarity) http://art.thewalters.org/viewwoa.aspx?id=33263 In the two scenes on this cylinder seal, a heroic figure with heavy beard and long curls holds off two roaring lions, and another hero struggles with a water buffalo. The inscription in the panel identifies the owner of this seal as "Ur-Inanna, the farmer."

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1999.325.4 (Bos gaurus shown with greater clarity) http://art.thewalters.org/viewwoa.aspx?id=33263 In the two scenes on this cylinder seal, a heroic figure with heavy beard and long curls holds off two roaring lions, and another hero struggles with a water buffalo. The inscription in the panel identifies the owner of this seal as "Ur-Inanna, the farmer." Clay sealing from private collection with water buffalo, crescent-star, apparently Akkadian period.

Clay sealing from private collection with water buffalo, crescent-star, apparently Akkadian period.मेढ [ mēḍha ]The polar star. (Marathi) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Munda.Ho.)

मेंढसर [mēṇḍhasara] m A bracelet of gold thread. (Marathi)

Santali glosses

Santali glossesA lexicon suggests the semantics of Panini's compound अयस्--काण्ड [p= 85,1] m. n. " a quantity of iron " or " excellent iron " , (g. कस्का*दि q.v.)( Pa1n2. 8-3 , 48)(Monier-Williams).

From the example of a compound gloss in Santali, I suggest that the suffix -kANDa in Samskritam should have referred to 'implements'. Indus Script hieroglyphs as hypertext components to signify kANDa 'implements' are: kANTa, 'overflowing water' kANDa, 'arrow' gaNDa, 'four short circumscript strokes'.

A good example of the ‘overflowing’ Indus Script hieroglyph is the Mohenjo-daro pectoral.

kāṇḍam காண்டம்² kāṇṭam, n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர். துருத்திவா யதுக்கிய குங்குமக் காண் டமும் (கல்லா. 49, 16). Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘metal tools, pots and pans’ (Marathi)

who is readily identifiable by his two faces looking in opposite directions (duality).

The following semantic cluster indicates that the early compound: loha + kāṇḍa referred to copper articles, tools, pot and pans. The early semantics of 'copper' got expanded to cover 'iron and other metals'. It is suggested that the hieroglyph of an overflowing vase refers to this compound: lohakāṇḍā.

Loha (nt.) [Cp. Vedic loha, of Idg. *(e)reudh "red"; see also rohita & lohita] metal, esp. copper, brass or bronze. It is often used as a general term & the individual application is not always sharply defined. Its comprehensiveness is evident from the classification of loha at VbhA 63, where it is said lohan ti jātilohaŋ, vijāti˚, kittima˚, pisāca˚ or natural metal, produced metal, artificial (i. e. alloys), & metal from the Pisāca district. Each is subdivided as follows: jāti˚=ayo, sajjhaŋ, suvaṇṇaŋ, tipu, sīsaŋ, tambalohaŋ, vekantakalohaŋ; vijāti˚=nāga -- nāsika˚; kittima˚=kaŋsalohaŋ, vaṭṭa˚, ārakūṭaŋ; pisāca˚=morakkhakaŋ, puthukaŋ, malinakaŋ, capalakaŋ, selakaŋ, āṭakaŋ, bhallakaŋ, dūsilohaŋ. The description ends "Tesu pañca jātilohāni pāḷiyaŋ visuŋ vuttān' eva (i. e. the first category are severally spoken of in the Canon). Tambalohaŋ vekantakan ti imehi pana dvīhi jātilohehi saddhiŋ sesaŋ sabbam pi idha lohan ti veditabbaŋ." -- On loha in similes see J.P.T.S. 1907, 131. Cp. A

professional names such as simug 'blacksmith' and tibira 'copper smith', 'metal-manufacturer' are not in origin Sumerian words.

Agricultural terms, like engar 'farmer', apin 'plow' and absin 'furrow', are neither of Sumerian origin.

Craftsman like nangar 'carpenter', agab 'leather worker'

Religious terms like sanga 'priest'

Some of the most ancient cities, like Kish, have names that are not Sumerian in origin.

These words must have been loan words from a substrate language. The words show how far the division in labor had progressed even before the Sumerians arrived."

(http://www.wsu.edu:8080/~dee/meso/meso.htm - No longer available)

కాండము [ kāṇḍamu ] kānḍamu. [Skt.] n. Water. నీళ్లు (Telugu) kaṇṭhá -- : (b) ʻ water -- channel ʼ: Paš. kaṭāˊ ʻ irrigation channel ʼ, Shum. xãṭṭä. (CDIAL 14349). kāṇḍa ‘flowing water’ Rebus: kāṇḍā ‘metalware, tools, pots and pans’. lokhaṇḍ (overflowing pot) ‘metal tools, pots and pans, metalware’ lokhãḍ ‘overflowing pot’ Rebus: ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ (Gujarati) Rebus: लोखंड lokhaṇḍ Iron tools, vessels, or articles in general. lo ‘pot to overflow’. Gu<loRa>(D) {} ``^flowing strongly''.

கொட்டம்¹ koṭṭam Flowing, pouring; நீர் முதலியன ஒழுகுகை. கொடுங்காற் குண்டிகைக் கொட்ட மேய்ப்ப (பெருங். உஞ்சைக். 43, 130) கொட்டம் koṭṭam < gōṣṭha. Cattle- shed (Tamil)

Gudea’s link with Meluhha is clear from the elaborate texts on the two cylinders describing the construction of the Ninĝirsu temple in Lagash. An excerpt: 1143-1154. Along with copper, tin, slabs of lapis lazuli, refined silver and pure Meluḫa cornelian, he set up (?) huge copper cauldrons, huge …… of copper, shining copper goblets and shining copper jars worthy of An, for laying (?) a holy table in the open air …… at the place of regular offerings (?). Ninĝirsu gave his city, Lagaš

Impression of seal on tablets from Kanesh (After Larsen, Mogens Trolle and Moller Eva, Five old Assyrian texts, in: D. Charpin - Joannès F. (ed.), Marchands, Diplomates et Empereurs. Études sur la civilization Mésopotamienne offertes à Paul Garelli (Éditions research sur les Civilisations), Paris, 1991, pp. 214-245: figs. 5,6 and 10.)

Impression of seal on tablets from Kanesh (After Larsen, Mogens Trolle and Moller Eva, Five old Assyrian texts, in: D. Charpin - Joannès F. (ed.), Marchands, Diplomates et Empereurs. Études sur la civilization Mésopotamienne offertes à Paul Garelli (Éditions research sur les Civilisations), Paris, 1991, pp. 214-245: figs. 5,6 and 10.) Workers from Elam, Susa, Magan and Meluhha were deployed by Gudea, the ruler of Lagaṣ, to build The Eninnu, the main temple of Girsu, c. 2125 BCE. We are dealing with Indian sprachbundwhen we refer to Meluhha. This sprachbund has a remarkable lexeme which is used to signify a smithy, as also a temple: Kota. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. Toda. kwala·l Kota smithy Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer; Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133).

Workers from Elam, Susa, Magan and Meluhha were deployed by Gudea, the ruler of Lagaṣ, to build The Eninnu, the main temple of Girsu, c. 2125 BCE. We are dealing with Indian sprachbundwhen we refer to Meluhha. This sprachbund has a remarkable lexeme which is used to signify a smithy, as also a temple: Kota. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. Toda. kwala·l Kota smithy Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer; Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133).  Location.Current Repository Location.Current Repository | |||

Musee du Louvre. Inventory No. AO 22126 ca. 2120 BCE Neo-Sumerian from the city-state of Lagash. http://contentdm.unl.edu/ah_copyright.html Inscription on base of skirt- God commands him to build house. Gudea is holding plans. Gudea depicted as strong, peaceful ruler. Vessel flowing with life-giving water w/ fish. Text on garment dedicates himself, the statue, and its temple to the goddess Geshtinanna. According to the inscription this statue was made by Gudea, ruler of Lagash (c. 2100 BCE) for the temple of the goddess Geshtinanna. Gudea refurbished the temples of Girsu and 11 statues of him have been found in excavations at the site. Nine others including this one were sold on the art market. It has been suggested that this statue is a forgery. Unlike the hard diorite of the excavated statues, it is made of soft calcite, and shows a ruler with a flowing vase which elsewhere in Mesopotamian art is only held by gods. It also differs stylistically from the excavated statues. On the other hand, the Sumerian inscription appears to be genuine and would be very difficult to fake. Statues of Gudea show him standing or sitting. Ine one, he rests on his knee a plan of the temple he is building. On some statues Gudea has a shaven head, while on others like this one he wears a headdress covered with spirals, probably indicating that it was made out of fur. Height 61 cm. The overflowing water from the vase is a hieroglyph comparable to the pectoral of Mohenjo-daro showing an overflowing pot together with a one-horned young bull and standard device in front. The diorite from Magan (Oman), and timber from Dilmun (Bahrain) obtained by Gudea could have come from Meluhha. "The goddess Geshtinanna was known as “chief scribe” (Lambert 1990, 298– 299) and probably was a patron of scribes, as was Nidaba/Nisaba (Micha-lowski 2002). " http://www.academia.edu/2360254/Temple_Sacred_Prostitution_in_Ancient_Mesopotamia_Revisited That the hieroglyph of pot/vase overflowing with water is a recurring theme can be seen from other cylinder seals, including Ibni-Sharrum cylinder seal. Such an imagery also occurs on a fragment of a stele, showing part of a lion and vases. |

Ancient Near East evidence for meluhha language and bronze-age metalware

Neolithic expansion (9000–6500 BCE)

[quote] A first period of indirect contacts seems to have occurred as a consequence of the Neolithic Revolution and the diffusion of agriculture after 9000 BCE. The prehistoric agriculture of South Asia is thought to have combined local resources, such as humped cattle, with agricultural resources from the Near East as a first step in the 8th–7th millennium BCE, to which were later added resources from Africa and East Asia from the 3rd millennium BCE. Mehrgarh is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in South Asia. At Mehrgarh, around 7000 BCE, the full set of Near Eastern incipient agricultural products can be found: wheat, barley, as well as goats, sheep and cattle. The rectangular houses of Merghah as well as the female figurines are essentially identical with those of the Near East.

The Near-Eastern origin of South Asian agriculture is generally accepted, and it has been the "virtual archaeological dogma for decades". Gregory Possehl however argues for a more nuanced model, in which the early domestication of plant and animal species may have occurred in a wide area from the Mediterranean to the Indus, in which new technology and ideas circulated fast and were widely shared. Today, the main objection to this model lies in the fact that wildwheat has never been found in South Asia, suggesting that either wheat was first domesticated in the Near-East from well-known domestic wild species and then brought to South Asia, or that wild wheat existed in the past in South Asia but somehow became extinct without leaving a trace.

Jean-François Jarrige argues for an independent origin of Mehrgarh. Jarrige notes "the assumption that farming economy was introduced full-fledged from Near-East to South Asia,"[28][c] and the similarities between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus valley, which are evidence of a "cultural continuum" between those sites. But given the originality of Mehrgarh, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an earlier local background," and is not a "'backwater' of the Neolithic culture of the Near East” [unquote] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus%E2%80%93Mesopotamia_relations

Various stamp seals are known from the Indus and the Persian Gulf area, with depictions of large ships pertaining to different shipbuilding traditions. Sargon of Akkad (c. 2334–2284 BCE) claimed in one of his inscriptions that "ships from Meluhha, Magan and Dilmun made fast at the docks of Akkad". (Potts, Daniel T. (1997). Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. Cornell University Press. pp. 134–135.)

Sea-going vessel with direction finding birds to find land. Mohenjo-Daro seal, 2500-1750 BCE. This seal shows oxhide shaped copper/tin ingots as cargo.

Slide 24. harappa.com Moulded tablet, Mohenjo-daro.Three sided molded tablet. One side shows a flat bottomed boat with a central hut that has leafy fronds at the top of two poles. Two birds sit on the deck and a large double rudder extends from the rear of the boat. On the second side is a snout nosed gharial with a fish in its mouth. The third side has eight symbols of the Indus script.

Material: terra cotta.Dimensions: 4.6 cm length, 1.2 x 1.5 cm width Mohenjo-daro, MD 602.Islamabad Museum, NMP 1384.Dales 1965a: 147, 1968: 39

See: Mohenjo-daro boat tablet is Rosetta stone for ḍhālako ox-hide-shape copper & tin ingots cargo of Meluhha merchants

https://tinyurl.com/yxcave2w

A characteristic feature of Tin-Bronze Age is the use of ox-hide-shaped large copper and tin metal ingots as cargo for transport by seafaring merchants.

Such cargo has been identified in shipwrecks of Gelidonya and Uluburn. The ox-hide-shape of ingots was evidenced for both copper and tin ingots. Such a pair of ingots was shown as cargo on a boat on a Mohenjo-daro tablet. m1429 Prism tablet with Indus inscriptions on 3 sides. Since Indus Script writing is most pronounced in the Mature phase of Sarasvati Civilization, the tablet can be dated to between ca. 2500 -1900 BCE. It is surmised that the ingots shown on the boat were produced by Meluhha merchants because the language used in the script is Meluhha rebur renderings of metalwork.

Hieroglyph: కారండవము [kāraṇḍavamu] n. A sort of duck. కారండవము [ kāraṇḍavamu ] kāraṇḍavamu. [Skt.] n. A sort of duck. कारंडव [kāraṇḍava ] m S A drake or sort of duck. कारंडवी f S The female. karandava [ kârandava ] m. kind of duck. कारण्ड a sort of duck R. vii , 31 , 21 கரண்டம் karaṇṭam, n. Rebus: karaḍā ‘hard alloy’ (Marathi) karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)A pair of birds కారండవము [kāraṇḍavamu] n. A sort of duck. కారండవము[ kāraṇḍavamu ] kāraṇḍavamu. [Skt.] n. A sort of duck. कारंडव [kāraṇḍava ] m S A drake or sort of duck. कारंडवी f S The female. karandava [ kârandava ] m. kind of duck. कारण्ड a sort of duck R. vii , 31 , 21 கரண்டம் karaṇṭam, n. Rebus: karaḍa 'hard alloy (metal)'. tamar ‘palm’ (Hebrew) Rebus: tam(b)ra ‘copper’ (Santali) dula ‘pair’ Rebus: dul ‘cast metal’ (Santali)

bagalo = an Arabian merchant vessel (Gujarati) bagala = an Arab boat of a particular description (Ka.); bagalā (M.); bagarige, bagarage = a kind of vessel (Kannada) Rebus: bangala = kumpaṭi = angāra śakaṭī = a chafing dish a portable stove a goldsmith’s portable furnace (Telugu) cf. bangāru bangāramu = gold (Telugu).

Ox-hide ingot is so-called because of its shape https://www.

The other two sides of the tablet also contain Indus Script inscriptions.

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS karA 'crocodile' rebus:

khAr 'blacksmith' Together,

Side 2: kāru ‘crocodile’ Rebus: kāru ‘artisan’. Thus, together read

rebus: ayakara ‘metalsmith’.

Side A: kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Telugu) ghariyal id. (Hindi)

kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) கராம் karām, n. prob. grāha. 1. A species of alligator; முதலைவகை. முதலையுமிடங்கருங்கராமும் (குறிஞ்சிப். 257). 2. Male alligator; ஆண்முதலை. (திவா.) కారుమొసలి a wild crocodile or alligator. (Telugu) Rebus: kāru ‘artisan’ (Marathi) kāruvu 'artisan' (Telugu) khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

[fish = aya (G.); crocodile = kāru (Telugu)] Rebus: ayakāra ‘ironsmith’ (Pali)

The shape of he boat on the moulded tablet is comparable to the Bronze Age Uluburn ship which had a shipwreck.I suggest that this boat was in charge of a supercargo (rebus: karNi  Most frequently-occurring hieroglyph on Indus writing corpora: 'rim-of-jar') of copper and tin ingots, based on a rebus reading of the hieroglyphs on three sides of the prism tablet, including a text in Indus writing, apart from the ligatured hieroglyph of a crocodile catching a fish in its jaws [which is read ayakara 'blacksmith'; cf. khar 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri);

Most frequently-occurring hieroglyph on Indus writing corpora: 'rim-of-jar') of copper and tin ingots, based on a rebus reading of the hieroglyphs on three sides of the prism tablet, including a text in Indus writing, apart from the ligatured hieroglyph of a crocodile catching a fish in its jaws [which is read ayakara 'blacksmith'; cf. khar 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri);

khār 1

karavu'crocodile' (Telugu); ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'metal (tin+ copper alloy)'. Text 3246 on the third side of the prism. kāḍ काड् ‘, the stature of a man’ Rebus: खडा [ khaḍā ] m A small stone, a pebble (Marathi) dula ‘pair’ Rebus: dul ‘cast (metal)’shapes objects on a lathe’ (Gujarati) kanka, karṇaka ‘rim of jar’ Rebus: karṇaka ‘account scribe’. kārṇī m. ʻsuper cargo of a ship ʼ(Marathi)

A pair of ingots with notches in-fixed as ligatures.

kolom ‘cob’; rebus: kolmo ‘seedling, rice (paddy) plant’ (Munda.) kolma hoṛo = a variety of the paddy plant (Desi)(Santali.) kolmo ‘rice plant’ (Mu.) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace,smithy’ (Telugu) Thus, the ligatured glyph reads: khaḍā ‘stone-ore nodule’kolami ‘furnace,smithy’. Alternatives: 1. koṛuŋ young shoot (Pa.) (DEDR 2149) Rebus: kol iron, working in iron, blacksmith (Tamil) kollan blacksmith, artificer (Malayalam) kolhali to forge.(DEDR 2133).2. kaṇḍe A head or ear of millet or maize (Telugu) Rebus: kaṇḍa ‘stone (ore)(Gadba)’ Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (DEDR 1298).

ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayas ‘metal’.

कारणीक [ kāraṇī or kāraṇīka ] a (कारण S) That causes, conducts, carries on, manages. Applied to the prime minister of a state, the supercargo of a ship &c. (Marathi) [

कर्णिक A knot, round protuberance

कारण a number of scribes or कायस्थs W. करण m. a man of a mixed class (the son of an outcast क्षत्रिय Mn. x , 22 ; or the son of a शूद्र woman by a वैश्य Ya1jn5. i , 92 ; or the son of a वैश्य woman by a क्षत्रिय MBh. i , 2446 ; 4521 ; the occupation of this class is writing , accounts &c )m. writer , scribe W.

karṇadhāra m. ʻ helmsman ʼ Suśr. [

कर्णिक a. Having a helm. -कः A steersman.

कर्णिन् karṇinकर्णिन् a. 1 Having ears; Av.1.1.2.-2 Long- eared.-3 Barbed (as an arrow). -m. 1 An ass.-2 A helmsman.-3 An arrow furnished with knots &c. (Apte)

kāraṇika m. ʻ teacher ʼ MBh., ʻ judge ʼ Pañcat. [

கருணீகம் karuṇīkam, n. < karaṇa. [T. karaṇikamu.] Office of village accountant or karṇam;கிராமக்கணக்குவேலை.

गांवकुळकरणी (p. 234) [ gāṃvakuḷakaraṇī ] m The hereditary village-accountant: in contrad. from

m An hereditary officer of a Mahál. He frames the general account from the

accounts of the several Khots and Kulkarn̤ís of the villages within the Mahál;

the district-accountant.

meḍ ‘body’, ‘dance’ (Santali) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.)

kāḍ काड् ‘, the stature of a man’ Rebus: खडा [ khaḍā ] m A small stone, a pebble (Marathi).

Thus, the indus script inscription of m1429 Mohenjo-daro seal is a bill of lading listing details of cargo loaded on the boat:read rebus:

alloy metal smith, ḍhālako ‘large ingots’, hard alloys

karaḍa 'hard alloy (metal)'. tamar ‘palm’ (Hebrew) Rebus: tam(b)ra ‘copper’ (Santali) dula ‘pair’ Rebus: dul ‘cast metal’

ingots (of smithy), alloy metal (of smithy), lapidary work of stones, minerals, gemstones, (metal) equipment, (authorised by) helmsman.

A rare etched carnelian bead found in Egypt, thought to have been imported from the Indus Valley Civilization through Mesopotamia. Late Middle Kingdom. London, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, ref. UC30334.

Sources: Grajetzki, Wolfram (2014). "Tomb 197 at Abydos, further evidence for long distance trade in the Middle Kingdom". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 24: 159–170.

Stevenson, Alice (2015). Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology: Characters and Collections. UCL Press. p. 54.

Etched carnelian beads excavated in the Royal Cemetery of Ur, tomb PG 1133, 2600-2500 BCE.

Hall, Harry Reginald; Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1934). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 133.

Journal: Iranica Antiqua

Volume: 44 Date: 2009

Pages: 1-45

DOI: 10.2143/IA.44.0.2034374

![Image result for tin belt bharatkalyan97]() The largest tin belt of the globe is in Ancient Far East

The largest tin belt of the globe is in Ancient Far East

The largest tin belt of the globe is in Ancient Far East

The largest tin belt of the globe is in Ancient Far EastCuneiform texts record long distance copper trade

"Cuneiform texts from the Late Uruk/Jemdet Nasr Period to the Old Babylonian Period (c. 3100-1750 B.C.) record the importation by sea of copper from Meluhha (probably northwest India), Magan (likely southeastern Arabia), and Dilmun (probably modern Bahrain) by Mesopotamian merchants, probably working either as agents for the city temple or rulers.(1) Some trade by private individuals took place as well, though on a smaller scale. (2) The archives of one merchant from Old Babylonian period Ur were excavated by Woolley; these record the importation of copper from Tilmun (probably in Iran) via the Persian Gulf, as well as various disputes with customers over the quality of his copper and the speed of his deliveries. (3) Production of finished copper and bronze products seems to have followed a similar pattern as Pylos, Alalakh, and Ugarit in Third Dynasty Ur (c. 2100 B.C.E.); at all of these sites, clay tablets record the allotment of copper to smiths for the production of weapons and other tems.(4)" (Michael Rice Jones, 2007, Oxhide ingots, coper production, and the mediterranean trade in copper and other metals in the Bronze Age, Thsesis submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University, 418 pages: p.62).

"Metal ores, particularly the ores of copper and tin that became so important in the Bronze Age, take an enormous amount of labor and technological expertise to extract from the natural environment and process into useful finished products. Metal ores also occur in geographically localized areas, which would have limited access of prehistoric communities to metals and encouraged long distance trade between them. By the second millennium B.C.,Mediterranean societies had developed complex trade networks to transport and exchange metals and other bulk goods over long distances. Copper, particularly as the main component of bronze, became one the most important materials for tools, weapons, and statusenhancing luxury goods during the Bronze Age." (5)(ibid., p.1)

Cuneiform texts record long distance trade in tin

"Texts from the palace of Zimri-lin (c.1780-1760 B.C.) of Mari in northern Syria attest to a thriving trade in tin operated by Assyrian merchants, who exported tin to Anatolia for twice the price at which they had purchased it.(6) These records indicate that copper and bronze were imported to Mari from Alashia, and that tin was imported to Mari from the Mesopotamian city of Esnunna; it was then transported to various cities in Syria and Palestine, ultimately reaching Ugarit.(7) The source of the tin from Mari is unknown, but it may have been transported overland from eastern Afghanistan.(8) One document records the purchase of tin by individuals called “the Caphtorite” (usually translated as ‘the Cretan’), who received 20 minas of tin “for the second time,” and “the Carian,” who received an unknown amount of tin.(9) The foreigners in Mari were likely agents for purchasing tin and other goods in the city.(10) Various objects from “Kaptara”, usually identified as Keftiu or Crete, are mentioned in the Mari texts as well; therefore, it seems likely that the tin route continued further west toCrete and Anatolia.(11) References to objects and materials connected with Caphtor or Keftiu are also known from several Bronze-Age texts from Mari. Since references to metal objects of ‘Keftian’ origin, workmanship, or style are the most prominent associations with the name, Keftiu seems to have been known especially for its metalwork.(12) Scattered references to the name Keftiu appear in New Kingdom Egyptian texts as well, dating from perhaps as early as c. 2300 B.C., through the second and first millennia B.C.E, to the most recent references in the Roman period.(13) Keftiu is most commonly identified with Crete, although locations such as Cyprus,Cilicia, and the Cyclades have also been proposed.(14) The sophisticated Minoan metallurgy industry would have required large amounts of imported tin and copper in order to function, since there are no tin and only insignificant copper deposits known on the island.(15)"(ibid., p.58)

Cuneiform texts record long distance trade in tin

Sources: http://nautarch.tamu.edu/Theses/pdf-files/JonesM-MA2007.pdf

Volume 48, Number 1, EXPEDITION, pp. 42, 43

Cylinder seal described as Akkadian circa 2334-2154 BCE, cf. figure 428, p. 30. "The Surena Collection of Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals." Christies Auction Catalogue. New York City. Sale of 11 June 2001). A person carrying an antelope may be a Meluhhan (as in the Shu-ilishu Meluhhan interpreter cylinder seal).

Cylinder seal described as Akkadian circa 2334-2154 BCE, cf. figure 428, p. 30. "The Surena Collection of Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals." Christies Auction Catalogue. New York City. Sale of 11 June 2001). A person carrying an antelope may be a Meluhhan (as in the Shu-ilishu Meluhhan interpreter cylinder seal). Cylinder seal of Shu-ilishu, interpreter for Meluhha. Cuneiform inscription in Old Akkadian. Serpentine. Mesopotamia ca 2220-2159 BCE H. 2.9 cm, Dia 1.8 cm Musee du Louvre, Departement des Antiquites, Orientales, Paris AO 22310 “Based on cuneiform documents from Mesopotamia we know that there was at least one Meluhhan village in Akkad at that time, with people called ‘Son of Meluhha‘ living there. The cuneiform inscription (ca. 2020 BCE) says that the cylinder seal belonged to Shu-ilishu, who was a translator of the Meluhhan language. “The presence in Akkad of a translator of the Meluhhan language suggests that he may have been literate and could read the undeciphered Indus script. This in turn suggests that there may be bilingual Akkadian/Meluhhan tablets somewhere in Mesopotamia. Although such documents may not exist, Shu-ilishu’s cylinder seal offers a glimmer of hope for the future in unraveling the mystery of the Indus script.”

Cylinder seal of Shu-ilishu, interpreter for Meluhha. Cuneiform inscription in Old Akkadian. Serpentine. Mesopotamia ca 2220-2159 BCE H. 2.9 cm, Dia 1.8 cm Musee du Louvre, Departement des Antiquites, Orientales, Paris AO 22310 “Based on cuneiform documents from Mesopotamia we know that there was at least one Meluhhan village in Akkad at that time, with people called ‘Son of Meluhha‘ living there. The cuneiform inscription (ca. 2020 BCE) says that the cylinder seal belonged to Shu-ilishu, who was a translator of the Meluhhan language. “The presence in Akkad of a translator of the Meluhhan language suggests that he may have been literate and could read the undeciphered Indus script. This in turn suggests that there may be bilingual Akkadian/Meluhhan tablets somewhere in Mesopotamia. Although such documents may not exist, Shu-ilishu’s cylinder seal offers a glimmer of hope for the future in unraveling the mystery of the Indus script.” 12th cent. BCE. An Elamite silver statuette showed a person (king?) carrying an antelope on his hands, the same way a Meluhhan carried an antelope on his hands (as shown on a cylinder seal). Antelope carried by the Meluhhan is a hieroglyph: mlekh ‘goat’ (Br.); mr̤eka (Te.); mēṭam (Ta.); meṣam (Skt.) Thus, the goat conveys the message that the carrier is a Meluhha speaker.

12th cent. BCE. An Elamite silver statuette showed a person (king?) carrying an antelope on his hands, the same way a Meluhhan carried an antelope on his hands (as shown on a cylinder seal). Antelope carried by the Meluhhan is a hieroglyph: mlekh ‘goat’ (Br.); mr̤eka (Te.); mēṭam (Ta.); meṣam (Skt.) Thus, the goat conveys the message that the carrier is a Meluhha speaker. Scorpion with a Plant Cylinder seal and impression Mesopotamia, Late Uruk period/Jamdat Nasr period (ca. 3500–2900 B.C.E.) Marble 36.5 x 21 mm Seal no. 31

Scorpion with a Plant Cylinder seal and impression Mesopotamia, Late Uruk period/Jamdat Nasr period (ca. 3500–2900 B.C.E.) Marble 36.5 x 21 mm Seal no. 31Evidence for economic history, Indus Script Corpora, Arthaśāstra, wealth of the nation of Bharat of R̥gveda times

Production of textiles of cotton, silk, jute, domestication of farming, metalwork constitute principal sources of wealth of Sarasvati Civilization

Gy. eur. sendo, sindo (usu. pl. °de) m. ʻ a Gypsy ʼ (GWZS 2916)?(CDIAL 14837) Cotton was called sindon in Greek. Just as a ukku steel sword was called a hallmark product hindwani, cotton from Sarasvati civilization was also named after the country: sindhu, indon named after Greek Indos (Ἰνδός).

There is a distinct possibility that the reference to Meluhha in ancient Cuneiform records (3rd millennium BCE, Ur III dynasty) may be a reference to the region aroud Straits of Malaka (Malacca).

Tracing ancient roots of Kirāta, Meluhha speakers of Shu-ilishu cylinder seal, links with आमलक fruit, malaka people, authors of Indus Script Cipherhttps://tinyurl.com/yde89yyl Perhaps, the seafaring merchants of Meluhha (Sarasvati Civiliazation) were intermediaries with the producers of tin ore from the largest belt of the globe on Himalayan river basins of Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween, resulting in the discovery of three pure tin ingots with Indus Script inscriptions describing the ingots in Meluhha, found in a shipwreck in Haifa, Israel port.![]() The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris. The cuneiform text reads: Shu-Ilishu EME.BAL.ME.LUH.HA.KI (interpreter of Meluhha language). Apparently, the Meluhhan is the person carrying the antelope on his arms.

The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris. The cuneiform text reads: Shu-Ilishu EME.BAL.ME.LUH.HA.KI (interpreter of Meluhha language). Apparently, the Meluhhan is the person carrying the antelope on his arms.

Source: The Bronze Age Writing System of Sarasvati Hieroglyphics as Evidenced by Two “Rosetta Stones” By S. Kalyanaraman in: Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies Volume 1: Number 11 (2010), pp. 47-74.)

This article of 2010 had present rebus readings of inscriptions on the following two tin ingots.

Tin ingots in the Museum of Ancient Art of the Municipality of Haifa, Israel (left #8251, right #8252). The ingots each bear two inscribed “Cypro-Minoan markings”. (Note: I have argued that the inscriptions were Meluhha hieroglyphs (Indus or Sarasvati writing) denoting ranku ‘antelope’ (on left ingot) ranku ‘liquid measure’ (on right ingot) datu ‘cross’ read rebus as: ranku 'tin' dhatu 'ore'.

Another tin ingot with comparable Indus writing has been reported by Artzy:

Fig. 4 Inscribed tin ingot with a moulded head, from Haifa (Artzy, 1983: 53). (Michal Artzy, 1983, Arethusa of the Tin Ingot, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, BASOR 250, pp. 51-55) https://www.academia.edu/5476188/Artzy-1983-Tin-Ignot This figure indicates the head of a woman as a hieroglyph. Some scholars have suggested that this signifies Arethusa.

The author Michal Artzy (opcit., p. 55) who showed these four signs on the four tin ingots to E. Masson who is the author of Cypro-Minoan Syllabary. Masson’s views are recorded in Foot Note 3: “E. Masson, who was shown all four ingots for the first time by the author, has suggested privately that the sign ‘d’ looks Cypro-Minoan, but not the otherthree signs.”

If all the signs are NOT Cypro-Minoan Syllabary, what did these four signs, together, incised on the tin ingots signify?

The two hieroglyphs incised which compare with the two pure tin ingots discovered from a shipwreck in Haifa, the moulded head can be explained also as a Meluhha hieroglyphs without assuming it to be the face of goddess Arethusa in Greek tradition: Hieroglyph: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) Rebus: mũh ‘ingot’ (Santali). The three hieroglyphs are: ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali) ranku 'liquid measure' Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali). dāṭu = cross (Te.); dhatu = mineral (Santali) Hindi. dhāṭnā ‘to send out, pour out, cast (metal)’ (CDIAL 6771). [The 'cross' or X hieroglyph is incised on both ingots.]

All these hieroglyphs on the three tin ingots of Haifa are read rebus in Meluhha:

A challenge for researchers and students of civilization studies is to narrate the economic history of Bharat of R̥gveda times because the nation was the richest among all nations of the globe ca.0 CE.

It is an emphatic fact that R̥gveda has been composed on the banks of River Sarasvati. Archaeological attestation comes from sites such as Bhirrana, Kunal which take the roote of Hindu civilization to ca. 8th millennium BCE and sites such as Binjor and Kalibangan which evidence performance of Soma Yajña; and Bhirrana/Kunal dated from ca. 8th millennium BCE with continuous, unbroken settlement history. A famous potsherd of Bhirrana shows the Indus Script hypertext of a dance step of a dancing girl shown on a cire perdue bronze image of Mohenjo-daro, establishing the essential unity of over 2000 sites on the basin of Vedic River Sarasvati.

meḍ 'dance step' rebus; meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.); med 'copper' (Slavic) kola 'woman' rebus:kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'

There are over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions which constitute the documentary evidence from ca. 4th millennium BCE (Earliest potsherd with writing is dated to ca. 3300 BCE from Harappa, HARP). For significance of akṣa, the spoked wheel hypertext of Bhirrana (ca. 2500 BCE), see: the key word akṣa 'wheel' rebus: akṣa 'gold' a measure of wealth. Hence, अक्ष--पटल means 'weight called कर्ष , equal to 16 माषs'; 'depository of legal document; court of law'. akṣaracaṇa 'scribe' (Kannada) signified by the Mehrgarh & Shahi Tump artifacts, cire perdue spoked wheel, leopard weight https://tinyurl.com/y86cbhdx

IRS P3 WiFS True Color Composite image: palaeo-drainage of Vedic Sarasvati river basin. 4 to 10 kms. wide channels. ISRO, Jodhpur

![]() The octagonal brick/pillar found in this fire-altar of Binjor (Anupgarh) on the banks of River Sarasvati is aṣṭāśri yupa ('octagonal pillar')which is an octagonal pillar, declared in R̥gveda as yajñasya ketu (RV 3.8.8), i.e., a proclamation emblem of performance of a Soma Samsthā yajña (elaborated in detail in a Veda text: Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa). Soma Samsthā yajña are detailed as caṣāla with dhumaketu (godhuma, wheat chaff is caṣāla ring atop the yupa, pillar -- to infuse carbon into the molten metal to harden and produce a strong alloy of ayas, 'iron'). Soma Samsthā yajña yield

The octagonal brick/pillar found in this fire-altar of Binjor (Anupgarh) on the banks of River Sarasvati is aṣṭāśri yupa ('octagonal pillar')which is an octagonal pillar, declared in R̥gveda as yajñasya ketu (RV 3.8.8), i.e., a proclamation emblem of performance of a Soma Samsthā yajña (elaborated in detail in a Veda text: Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa). Soma Samsthā yajña are detailed as caṣāla with dhumaketu (godhuma, wheat chaff is caṣāla ring atop the yupa, pillar -- to infuse carbon into the molten metal to harden and produce a strong alloy of ayas, 'iron'). Soma Samsthā yajña yield

A challenge for researchers and students of civilization studies is to narrate the economic history of Bharat of R̥gveda times because the nation was the richest among all nations of the globe ca.0 CE.

It is an emphatic fact that R̥gveda has been composed on the banks of River Sarasvati. Archaeological attestation comes from sites such as Bhirrana, Kunal which take the roote of Hindu civilization to ca. 8th millennium BCE and sites such as Binjor and Kalibangan which evidence performance of Soma Yajña; and Bhirrana/Kunal dated from ca. 8th millennium BCE with continuous, unbroken settlement history. A famous potsherd of Bhirrana shows the Indus Script hypertext of a dance step of a dancing girl shown on a cire perdue bronze image of Mohenjo-daro, establishing the essential unity of over 2000 sites on the basin of Vedic River Sarasvati.

meḍ 'dance step' rebus; meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.); med 'copper' (Slavic) kola 'woman' rebus:kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'

There are over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions which constitute the documentary evidence from ca. 4th millennium BCE (Earliest potsherd with writing is dated to ca. 3300 BCE from Harappa, HARP). For significance of akṣa, the spoked wheel hypertext of Bhirrana (ca. 2500 BCE), see: the key word akṣa 'wheel' rebus: akṣa 'gold' a measure of wealth. Hence, अक्ष--पटल means 'weight called कर्ष , equal to 16 माषs'; 'depository of legal document; court of law'. akṣaracaṇa 'scribe' (Kannada) signified by the Mehrgarh & Shahi Tump artifacts, cire perdue spoked wheel, leopard weight https://tinyurl.com/y86cbhdx

बहुसुवर्णक bahusuvarṇaka, many golden products of wealth as evidenced on a Mulavarman's yupa inscription of Borneo, Indonesia; the expression is repeated in the epic Rāmāyaṇa. 19 Yupa inscriptions have been found comparable to the Indus Script seal found in Binjor which is a metalwork wealth catalogue accounting ledger.The Binjor Yupa is अष्टा* श्रि [p= 117,1] mfn. having eight corners S'Br. The octagonal shape provides for श्री [p= 1098,2] (= √1. श्रि) , to burn , flame , diffuse light RV. i , 68 , 1; f. (prob. to be connected with √1. श्रि and also with √1. श्री in the sense of " diffusing light or radiance " ; nom. श्र्/ईस् accord. to some also श्री) light , lustre , radiance , splendour , glory , beauty , grace , loveliness (श्रिय्/ए and श्रिय्/ऐ , " for splendour or beauty " , " beauteously " , " gloriously " cf. श्रिय्/असे ; du. श्रियौ , " beauty and prosperity " ; श्रिय आत्मजाः , " sons of beauty "i.e. horses [cf. श्री-पुत्र] ; श्रियः पुत्राः , " goats with auspicious marks ") RV. &c; prosperity , welfare , good fortune , success , auspiciousness , wealth , treasure , riches (श्रिया , " according to fortune or wealth ") , high rank , power , might , majesty , royal dignity (or " Royal dignity " personified ; श्रियो भाजः , " possessors of dignity " , " people of high rank ") AV. &c; N. of लक्ष्मी (as goddess of prosperity or beauty and wife of विष्णु , produced at the churning of the ocean , also as daughter of भृगु and as mother of दर्प) S3Br. &c; mfn. diffusing light or radiance , splendid , radiant , beautifying , adorning (ifc. ; » अग्नि- , अध्वर- , क्षत्र- , गण- , जन-श्री &c ) RV. iv , 41 , 8. [The word श्री is frequently used as an honorific prefix (= " sacred " , " holy ") to the names of deities (e.g. श्री-दुर्गा , श्री-राम) , and may be repeated two , three , or even four times to express excessive veneration. (e.g. श्री-श्री-दुर्गा &c ) ; it is also used as a respectful title (like " Reverend ") to the names of eminent persons as well as of celebrated works and sacred objects (e.g. श्री-जयदेव , श्रीभागवत) , and is often placed at the beginning or back of letters , manuscripts , important documents &c ; also before the words चरण and पाद " feet " , and even the end of personal names.]

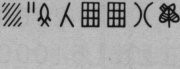

Decipherment:

Fish + scales, aya ã̄s (amśu) cognate ancu 'iron' (Tocharian) ‘metallic stalks of stone ore’. ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati) ayas 'metal alloy (Rgveda) Vikalpa 1: khambhaṛā 'fish fin' rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236) Vikalpa 2: badhoṛ ‘a species of fish with many bones’ (Santali) Rebus: baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali)

gaṇḍa 'four' Rebus: khaṇḍa 'metal implements' Together with cognate ancu 'iron' the message is: native metal implements. Thus, the hieroglyph multiplex reads: aya ancu khaṇḍa 'metallic iron alloy implements'.

koḍi ‘flag’ (Ta.)(DEDR 2049). Rebus 1: koḍ ‘workshop’ (Kuwi) Rebus 2: khŏḍ m. ‘pit’, khö̆ḍü f. ‘small pit’ (Kashmiri. CDIAL 3947)

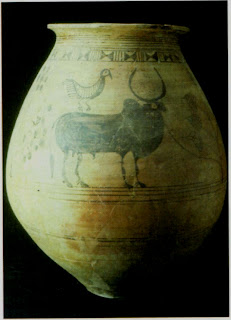

pōlaḍu 'black drongo' rebus: polad 'steel. See painted Nausharo pot with zebu + black drongo:Parallels from other examples of Indus Script Corpora![Image result for bird zebu fish bull indus seal]() A zebu bullA zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE.

A zebu bullA zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE.

A zebu bullA zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE.

A zebu bullA zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. An example of wealth accounting ledger, Indus Script signifiers of this wealth are: zebu and black drongo bird. Ancient Near East Indus Script hypertexts, pōḷa 'zebu', pōlaḍu 'black drongo' signify iron ore, steel https://tinyurl.com/y7aejs9o

![Image result for zebu drongo bharatkalyan97]() Nausharo pot. Indus Script hypertexts

Nausharo pot. Indus Script hypertexts

Jiroft Indus Script hypertexts evidence Meluhha interactions for metalwork trade & creation of wealth https://tinyurl.com/y9ta74um

pōḷa 'zebu' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore) pōladu 'black drongo bird' rebus: pōḷad 'steel' The semantics of bull (zebu) PLUS black drongo bird are the reason why the terracotta bird is shown with a bull's head as a phonetic determinative to signify 'steel/magnetite ferrite ore'.

See Susa pot with zebu + fish + black drongo:

Below the rim of the storage pot, the contents are described in Sarasvati Script hieroglyphs/hypertexts: 1. Flowing water; 2. fish with fin; 3. aquatic bird tied to a rope Rebus readings of these hieroglyphs/hypertexts signify metal implements from the Meluhha mint.

Clay storage pot discovered in Susa (Acropole mound), ca. 2500-2400 BCE (h. 20 ¼ in. or 51 cm). Musee du Louvre. Sb 2723 bis (vers 2450 avant J.C.)

kõda 'young bull, bull-calf' rebus: kõdā 'to turn in a lathe'; kōnda 'engraver, lapidary'; kundār 'turner'. kundana 'fine gold'. Ta. kuntaṉam interspace for setting gems in a jewel; fine gold (< Te.). Ka. kundaṇa setting a precious stone in fine gold; fine gold; kundana fine gold. Tu.kundaṇa pure gold. Te. kundanamu fine gold used in very thin foils in setting precious stones; setting precious stones with fine gold. (DEDR 1725)

Hieroglyph: sãghāṛɔ 'lathe'.(Gujarati) Rebus: sangara 'proclamation' sangara 'trade'.

Together, the message of the Binjor Seal with inscribed text is a proclamation, a metalwork catalogue (of) 'metallic iron alloy implements, hard alloy workshop'. Three characteristic hieroglyphs -- bos indicus (zebu), black drongo, and fish PLUS fish-fins' constitute a Hypertext expression to signify a mint working with cast iron and alloy metal. Three hieroglyph components of the expression are:

1. पोळ pōḷa, 'Zebu, bos indicus' pōlaḍu, 'black drongo' rebus: pōlaḍ 'steel'2 मेढा mēḍhā A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl rebus: med 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic) medhā 'dhana, yajna'. This is a semantic determinant of the hieroglyph पोळ pōḷa, 'Zebu, bos indicus' rebus: पोळ pōḷa, 'magnetite, ferrite ore'3. ayo 'fish' rebus: ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS khambhaṛā ʻfish-finʼ rebus: kammaṭi a coiner (Ka.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Ta.) kammaṭa = mint, gold furnace (Te.)The hypertext expression is demonstrated in a number of examples from Sindhu-Sarasvati (Indus) Script Corpora in this monograph.

पोळ pōḷa, 'Zebu, bos indicus' of Sarasvati Script corpora is rebus:pōlāda 'steel', pwlad (Russian), fuladh(Persian) folādī (Pashto)

pōḷa 'zebu' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore) pōladu 'black drongo bird' rebus: pōḷad 'steel' The semantics of bull (zebu) PLUS black drongo bird are the reason why the terracotta bird is shown with a bull's head as a phonetic determinative to signify 'steel/magnetite ferrite ore'.

పోలడు (p. 820) pōlaḍu , పోలిగాడు or దూడలపోలడు pōlaḍu. [Tel.] n. An eagle. పసులపోలిగాడు the bird called the Black Drongo. Dicrurus ater. (F.B.I.) rebus: pōlaḍu 'steel' (Russian. Persian) PLUS

1. पोळ pōḷa, 'Zebu, bos indicus' pōlaḍu, 'black drongo' rebus: pōlaḍ 'steel'

पोळ pōḷa, 'Zebu, bos indicus' of Sarasvati Script corpora is rebus:pōlāda 'steel', pwlad (Russian), fuladh(Persian) folādī (Pashto)

pōḷa 'zebu' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore) pōladu 'black drongo bird' rebus: pōḷad 'steel' The semantics of bull (zebu) PLUS black drongo bird are the reason why the terracotta bird is shown with a bull's head as a phonetic determinative to signify 'steel/magnetite ferrite ore'.

Three major sources of wealth of ancient Bharat which were harnessed by farming communities and smithy guilds were: 1. textiles; 2. woods from trees, farm products; and 3. metalwork. In metalwork which require an industrial scale of production, the guild organization with shared commonwealth was the key to explain the reality that Bharat of 1 CE contributed to 33% of World GDP in 1 CE (pace Angus Maddison).

Production of textiles of cotton, silk, jute, domestication of farming, metalwork constitute principal sources of wealth of Sarasvati Civilization. Of these sources, the metalwork wealth accounting ledgers and metalwork catalogues are available on over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions.

Today, India is the second largest producer of man-made fibres in the world, providing direct employment to over 35 million people. A major fibre produced is cotton which accounts for 60% of Indian textile industry. Other fibres produced in India include silk, jute, wool, and man-made fibers. India is first in global jute production and shares 63% of the global jute textile and garment market. Weaving and the spinning of cotton find mention in R̥gveda and evidence from the archaeological sites of Sarasvati Civilization. Sericulture and Silk Sector: India is the 2nd largest producer of silk in the world. India produces 18% of the world's total silk. Mulberry, Eri, Tasar, and Muga are the main types of silk produced in the country. A block printed and resist-dyed fabrics, whose origin is from Gujarat is found in tombs of Fostat, Fustat, also Fostat, Al Fustat, Misr al-Fustat and Fustat-Misr, iss the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, built by the Muslim general 'Amr ibn al-'As immediately after the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 641 CE. Large quantity of north Indian silk were traded through the silk route in China. http://www.textileasart.com/weaving.htm Woolen Sector: India is the 7th largest producer of the wool in the world.

![Image result for cotton pods india]()

![Image result for cotton pods india]()

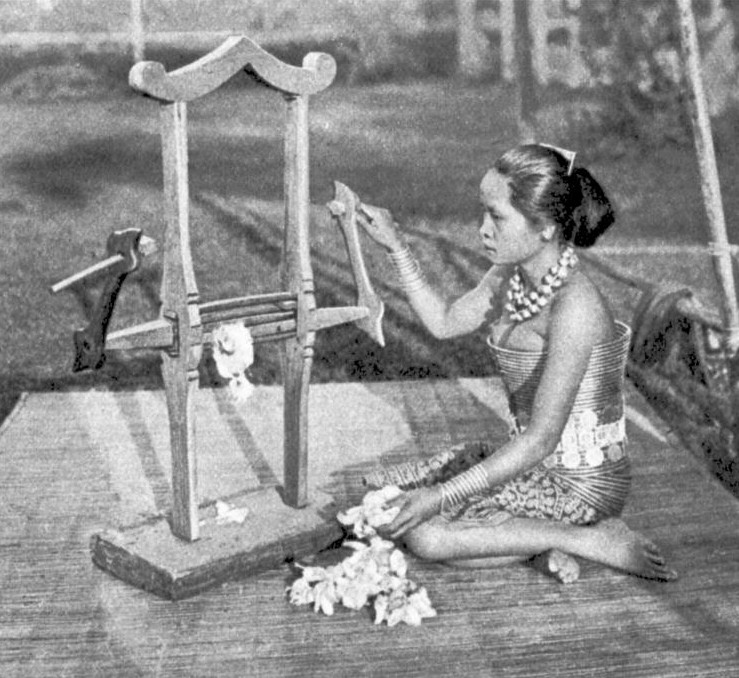

![Image result for spinner bharatkalyan97]() Cotton farming, processing, spinning. Spinner image source: Susa spinner bas-relief fragment, ca. 8th cent.BCE. Source: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Relief_spinner_Louvre_Sb2834.jpg http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/spinner H. 9 cm. W. 13 cm. Bituminous stone, a matte, black sedimentary rock. With her arms full of bracelets, the spinner holding a spindle is seated on a stool with tiger-paw legs. Elegantly coiffed, her hair is pulled back in a bun and held in place with a headscarf crossed around her head. Behind the spinner is an attendant holding a square wickerwork(?) fan. In front is a table with tiger-paw legs, a fish with six bun ingots. Susa. Neo-elamite period. 8th to 6th century BCE. The bas-relief was first cited in J, de Morgan's Memoires de la Delegation en Perse, 1900, vol. i. plate xi Ernest Leroux. Paris. Current location: Louvre Museum Sb2834 Near Eastern antiquities, Richelieu, ground floor, room 11.

Cotton farming, processing, spinning. Spinner image source: Susa spinner bas-relief fragment, ca. 8th cent.BCE. Source: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Relief_spinner_Louvre_Sb2834.jpg http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/spinner H. 9 cm. W. 13 cm. Bituminous stone, a matte, black sedimentary rock. With her arms full of bracelets, the spinner holding a spindle is seated on a stool with tiger-paw legs. Elegantly coiffed, her hair is pulled back in a bun and held in place with a headscarf crossed around her head. Behind the spinner is an attendant holding a square wickerwork(?) fan. In front is a table with tiger-paw legs, a fish with six bun ingots. Susa. Neo-elamite period. 8th to 6th century BCE. The bas-relief was first cited in J, de Morgan's Memoires de la Delegation en Perse, 1900, vol. i. plate xi Ernest Leroux. Paris. Current location: Louvre Museum Sb2834 Near Eastern antiquities, Richelieu, ground floor, room 11.

![Description: Iban Dayal pemigi]() Iban Dayak woman using a pemigi gin (Hose and McDougall 1912, pl. 118)

Iban Dayak woman using a pemigi gin (Hose and McDougall 1912, pl. 118)

![Description: Using a Bow East Sumba]() Fluffing ginned cotton with a bow, East Sumba

Fluffing ginned cotton with a bow, East Sumba

![Description: Drop-spinning Ile Api]()

![Description: Drop-spinning Savu]() Women drop-spinning at Ile Api, Lembata, and Ledatadu, Savu

Women drop-spinning at Ile Api, Lembata, and Ledatadu, Savu

http://www.asiantextilestudies.com/cotton.html

This is the clear indicator of links between people of Indonesia and of ancient Gujarat in production of cotton textiles, a contact which finds expression in the common Batik textiles created by the weavers of Gujarat and Indonesia.

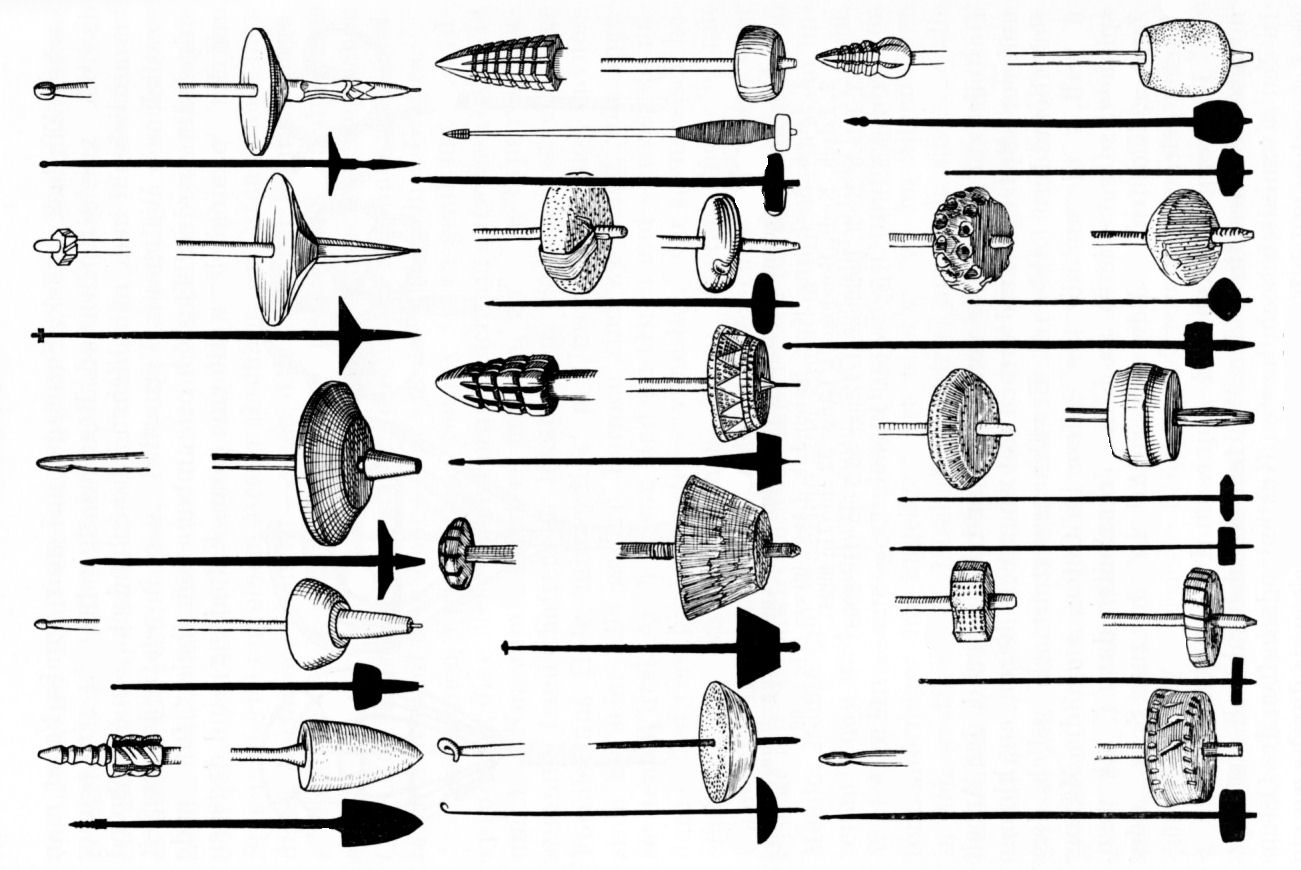

![Description: Drop-spindles Sumba]() Some of the drop spindles collected by Alfred Bühler during his 1949 Sumba expedition

Some of the drop spindles collected by Alfred Bühler during his 1949 Sumba expedition

The words sorka, cerka, serka are cognate carkha (Guajarati)

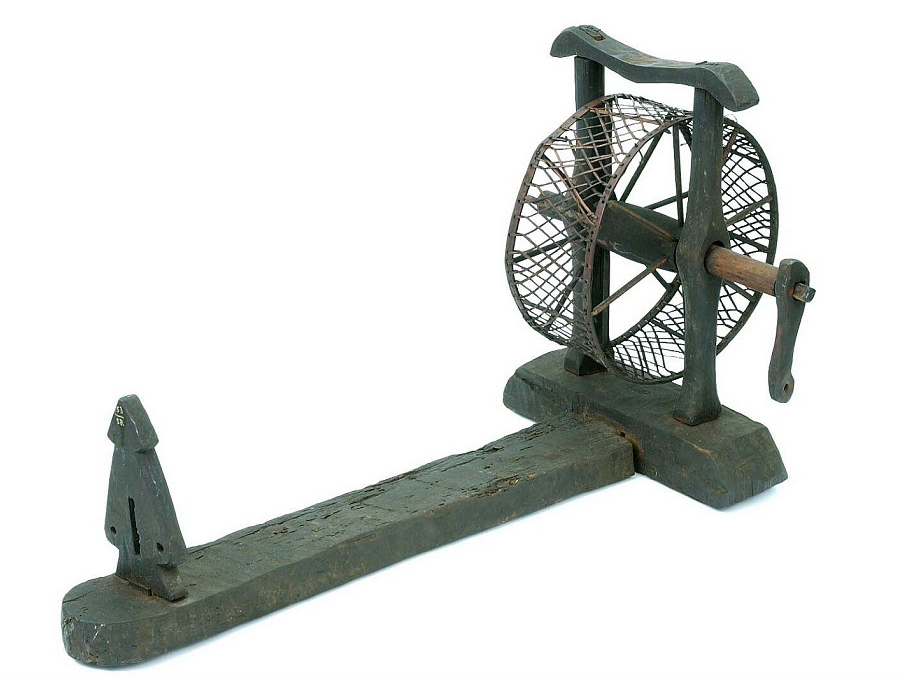

![Description: Toba Wheel]() Toba Batak sorka, Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam

Toba Batak sorka, Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam

![Description: Doka Wheel]() Spinning cotton on a simple spinning wheel, Doka, ‘Iwang Geté, Sikka Regency

Spinning cotton on a simple spinning wheel, Doka, ‘Iwang Geté, Sikka Regency

![Description: Niddy-Noddy Savu]() Winding spun threads on a niddy-noddy or lore on Savu Island

Winding spun threads on a niddy-noddy or lore on Savu Island

Indigo and brownish-purple dyes for cotton textiles

"Across Eastern Indonesia the two major natural dyes that have been traditionally used on cotton are indigo and morinda, especially with regard to making ikat. Because both dyes have a low substantivity on cotton, it is possible to produce a wide range of shades ranging from light to dark. These two major dyes have been supplemented by a huge range of minor dyes, including sappan, brazilwood, kayu kuning, tamarind, and turmeric."

http://www.asiantextilestudies.com/cotton.html

Moringa tinctoria plant known as aal or Indian mulberry is extensively cultivated in India in order to make the morindone dye sold under the trade name "Suranji". Morindone is used for the dyeing of cotton, silk and wool in shades of red, chocolate or purple. The colouring matter is found principally in the root bark and is collected when the plants reach three to four years of age...The active substance is extracted as the glucoside known as morindin that upon hydrolysis produces the dye. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morinda_tinctoria

![Noni fruit (Morinda citrifolia).jpg]() Morinda leaves and fruit. Morinda bark produces a brownish-purplish dye that may be used for making batik.

Morinda leaves and fruit. Morinda bark produces a brownish-purplish dye that may be used for making batik.

Local names for spinning wheels Adams 1969, 71; Barnes 1989, 25; Crawfurd 1829, 167; Jasper & Pirngadie 1912, 320; Maxwell 1990, 158; Nabholz-Kartaschoff 2008, 73; Niessen 2009, 543; Suzuki 2003, 170; Yeager 2002, 61. Sarawak gasing Lampung tingkiran Nage jata Borneo jintera Bugis tingkere Sikka jata/ola ojang Acheh djeureukha Makassar tingkere Lembata tenulé Gayo Sumatra cerka Sunda kinchir/jantra East Sumba ndataru Batak Toba sorka Madura kantain Timor bninis Batak Karo serka Java jantra/jontro Fordata putal Minangkabau kintjie Bali jantra

![Related image]() Incised spindle whorls. Sarasvati Civilization. Source: https://www.pinterest.se/pin/314829830177242802/

Incised spindle whorls. Sarasvati Civilization. Source: https://www.pinterest.se/pin/314829830177242802/

![Roman Bone Spindle Whorls]() Roman bone spindle whorls.

Roman bone spindle whorls.

Why is a dotted circle signified on a spindle whorl? The same hypertext appears on the apparel worn by Mohenjodaro priest.

The dotted circle signifies a wisp of fibre produced on the spindle: The word is Sindhi dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ; the word is read rebus to signify mineral ore as: M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ. See etyma: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā ] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

![Image result for spindle whorls bhirrana]() Old drop spindles.

Old drop spindles.

Ukraine. https://www.pinterest.com/missingspindle/spindle-sticks-on-etsy/

![Image result for spindle whorls mohenjodaro]()

![]()

![]() Bhirrana. Terracotta. Spoked wheels, spindles.ca. 2500 BCE

Bhirrana. Terracotta. Spoked wheels, spindles.ca. 2500 BCE

For significance of the spoked wheel hypertext of Bhirrana, see: the key word akṣa 'wheel' rebus: akṣa 'gold' a measure of wealth. Hence, अक्ष--पटल means 'weight called कर्ष , equal to 16 माषs'; 'depository of legal document; court of law'.akṣaracaṇa 'scribe' (Kannada) signified by the Mehrgarh & Shahi Tump artifacts, cire perdue spoked wheel, leopard weight https://tinyurl.com/y86cbhdx

The suffix -caṇa in akṣaracaṇa 'scribe' signifies the centre,middle; क्षण the centre , middle (Monier-Williams)![]()

![]() The spoked wheel made of copper alloy signifies akṣaracaṇa 'scribe'; and agasāle 'goldsmith, i.e. one who has a shop working with gold'.(Kannada)

The spoked wheel made of copper alloy signifies akṣaracaṇa 'scribe'; and agasāle 'goldsmith, i.e. one who has a shop working with gold'.(Kannada)

In many languages of the world, the word for coton is kapa. This comes from Samskrtam: कर्पास mf(ई)n. the cotton tree, cotton , Gossypium Herbaceum Sus3r.Lat. carbasus (Monier-Williams) कर्पास karpâsa cotton-shrub; cotton. कार्पासिक kârpâs-ika (î) made of cotton; -ikâ, f. *cotton shrub. कार्पासास्थि kârpâsa̮asthi seed of the cotton shrub. कार्पास kârpâsa cotton; cotton cloth; a. made of cotton: î, f. cotton shrub; -ka, a. made of cotton; -tântava, n. cotton cloth; -sautrika, n. id. Indus Script Hypertexts of Spinner plaque, Susa, 8th cent.BCE:The fish on a stool in front of the spinner with head-wrap can be read rebus for key hieroglyphs:

khuṭo ʻleg, footʼ. khũṭ ‘community, guild’ (Santali)kāti ‘spinner’ rebus: ‘wheelwright.’ vēṭha’head-wrap’. Rebus: veṭa , veṭha, veṇṭhe ‘a small territorial unit’. Rebus: bəḍhàri ʻmilitary guards in charge of treasure and stores of a templeʼ. bhāˊṇḍāgārika m. ʻ treasurer ʼ Kathās. [bhāṇḍāgāra -- ]Pa. bhaṇḍāgārika -- m. ʻ storekeeper ʼ, Pk. bhaṁḍāgāri(a) -- , bhaṁḍāri(a) -- m., P. WPah.cam. bhaṇḍārī; N. bhãṛāri ʻ treasurer, partic. class of Brahmans ʼ; A. bhãrāli ʻ storekeeper ʼ, B. bhã̄ṛāri, Or. bhaṇḍāri(ā), Bi. bhãṛārī m., Aw. H. G. bhãḍārī m., M. bhã̄ḍārī m.; OSi. inscr. baḍakarika, °iya ( -- k -- = -- y -- ), Si. baḍahära, ban̆ḍäri, badäriyā ʻ treasurer ʼ.Addenda: bhāṇḍāgārika -- : WPah.kṭg. bəḍhàri m. ʻ man in charge of treasure and stores of a temple ʼ, J. bhḍāri m.; Garh. bhãḍāri ʻ store -- keeper ʼ; Md. ban̆ḍēri ʻ treasurer ʼ.(CDIAL 9443)

sāi kol ayas kāṇḍa baṭa ‘friend+tiger+fish+stool+six’ rebus: association (of) iron-workers’ metal stone ore kiln.

Hieroglyphs and rebus readings using lexemes of Indian sprachbund

The Indian linguistic area (sprachbund) is evidenced in linguistic studies of Emeneau, Kuiper and Colin Masica with speakers of Indo-Aryan, Munda and Dravidian languages adopting language features from one another. (Emeneau, MB, 1956, India as a linguistic area, Language 32, 1956, 3-16; Kuiper, FBJ, 1948, Proto-Munda words in Sanskrit, Amsterdam, 1948; 1967, The genesis of a linguistic area, IIJ 10, 1967, 81-102; Masica, CP, 1971, Defining a Linguistic area. South Asia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.)

The Elamite lady spinner bas-relief is a composition of hieroglyphs depicting a guild of wheelwrights or ‘smithy of nations’ (harosheth hagoyim).

1. Six bun ingots. bhaṭa ‘six’ (Gujarati). Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’ (Gujarati.Santali) 2. ayo ‘fish’ (Munda). Rebus: ayas ‘metal’ (Sanskrit) aya ‘metal’ (Gujarati)3. kātī ‘spinner’ (G.) kātī ‘woman who spins thread’ (Hindi). Rebus: khātī ‘wheelwright’ (Hindi). kāṭi = fireplace in the form of a long ditch (Ta.Skt.Vedic) kāṭya = being in a hole (VS. XVI.37); kāṭ a hole, depth (RV. i. 106.6) khāḍ a ditch, a trench; khāḍ o khaiyo several pits and ditches (G.) khaṇḍrun: ‘pit (furnace)’ (Santali) kaḍaio ‘turner’ (Gujarati) 4. kola ‘woman’ (Nahali). Rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Te.) 5. Tiger’s paws. kola ‘tiger’ (Telugu); kola ‘tiger, jackal’ (Kon.). Rebus: kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil) Glyph: ‘hoof’: Kumaon. khuṭo ʻleg, footʼ, °ṭī ʻgoat's legʼ; Nepalese. khuṭo ʻleg, footʼ(CDIAL 3894). S. khuṛī f. ʻheelʼ; WPah. paṅ. khūṛ ʻfootʼ. (CDIAL 3906). Rebus: khũṭ ‘community, guild’ (Santali) 6. Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Malt. kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali) kāṇḍa ’stone ore’.7. meḍhi, miḍhī, meṇḍhī = a plait in a woman’s hair; a plaited or twisted strand of hair (P.) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) 8. ‘scarf’ glyph: dhaṭu m. (also dhaṭhu) m. ‘scarf’ (Wpah.) (CDIAL 6707) Rebus: dhatu ‘minerals’ (Santali)

Evidence for cotton, Sarasvati Civilization![]() 1. Marshall writes (Mohenjo-daro, p. 585): "This fragment of cloth was submitted to Mr. james Turner, Director of the Technological Research Laboratory, Bombay, for examination, who remarks in his preliminary report that 'The fibre was exceedingly tender and broke under very small stresses. However, some preparations were obtained revealing the convoluted structure characteristic of cotton. All the fibres examined were completely penetrated by fungal hyphae. The appearance of once of the convoluted fibres is shown in the accompanying photograph."

1. Marshall writes (Mohenjo-daro, p. 585): "This fragment of cloth was submitted to Mr. james Turner, Director of the Technological Research Laboratory, Bombay, for examination, who remarks in his preliminary report that 'The fibre was exceedingly tender and broke under very small stresses. However, some preparations were obtained revealing the convoluted structure characteristic of cotton. All the fibres examined were completely penetrated by fungal hyphae. The appearance of once of the convoluted fibres is shown in the accompanying photograph."![]() 2. Fragment with fabric impression, Harappa. A terracotta fragment with fabric impression from Trench 54 provides clues on the types of weaving carried out by the ancient Harappans.

2. Fragment with fabric impression, Harappa. A terracotta fragment with fabric impression from Trench 54 provides clues on the types of weaving carried out by the ancient Harappans.![]() 3. The earliest evidence of textiles at Harappa goes back to about 3300 BCE, and is another suggestion of how important this product must have been to the later Indus economy.

3. The earliest evidence of textiles at Harappa goes back to about 3300 BCE, and is another suggestion of how important this product must have been to the later Indus economy.![]()

4. Textile impressions on a toy bed made during the Harappan Phase (c. 2600-1900 BCE) show finely woven cloth made of uniformly spun threads. This example shows a fairly tightly woven normal weave.

"Farmers in the Indus valley were the first to spin and weave cotton. In 1929 archaeologists recovered fragments of cotton tetiles at Mohenjo-Daro, in what is now Pakistan, dating to between 3250 and 2750 BCE. Cottonseeds founds at nearby Mehrgarh have been dated to 5000 BCE. Literary references further point to the ancient nature of the subcontinent's cotton industry. The Vedic scriptures, composed between 1500 and 1200 BCE allude to cotton spinning and weaving . . .." So goes a remarkable new book, Empire of Cotton A Global History by Sven Beckert, which traces the development of the cotton industry in depth. Shown above are the fragments of cotton fibers so identified by Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, p. 585), and examples of weaves whose imprints have been found since at Harappa. Empire of Cotton goes on to show how the cotton industry, which India dominated in the early 18th century, was taken over by the British, how it spurred the slave trade with the Americas and the industrial revolution, its role a century in the independence movement and Gandhi's spinning wheel, and how it once again returned to Asia in a big way at the end of the 20th century. Though very little in the book has directly to do with the Indus civilization, it is a great example of how a single material and its exploitation can have such great impact on history; it is highly likely that the development of textile crafts were a key component of the Indus civilization's rise as well.

Captions

New evidence for silk, Sarasvati Civilization

![New Evidence for Early Silk in the Indus Civilization]() Coiled copper-alloy wire necklace discovered at Harappa in 2000 with traces of silk fibers preserved on the insidehttps://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Good%20Kenoyer%20and%20Meadow%202011%20Silk%20Response.pdf "First, we wish to clarify a major point. Our paper does not argue for a non-Chinese origin for the domestication of silkworms. We reported evidence that silk from wild indigenous forms of silkworm was known in the Indus Civilization at an early date, roughly contemporary with some of the earliest clear archaeological evidence for silk in China."

Coiled copper-alloy wire necklace discovered at Harappa in 2000 with traces of silk fibers preserved on the insidehttps://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Good%20Kenoyer%20and%20Meadow%202011%20Silk%20Response.pdf "First, we wish to clarify a major point. Our paper does not argue for a non-Chinese origin for the domestication of silkworms. We reported evidence that silk from wild indigenous forms of silkworm was known in the Indus Civilization at an early date, roughly contemporary with some of the earliest clear archaeological evidence for silk in China."

Crops in Middle Ganga Plain Region: Evidence for crop remains, Jhusi ca. 7000 BCECrop remains from Jhusi 7000-6000 BCE a, Oryza sativa (rice); b, Hordeum vulgare (hulled barley); c, Triticum aestivum (bread-wheat); d, Triticum sphaero- coccum (dwarf-wheat); e, Lens culinaris (lentil); f, Vigna radiata cotyledons (green-gram); g, Lathyrus sativus (grass-pea); h, Pisum arvense (field-pea); i, Vigna radiata (green-gram); j, Macrotyloma uniflorum (horse-gram); k, Sesamum indicum (sesame); l, Linum usitatissimum (linseed); m, Emblica officinalis (anwala); n, Vitis vinifera (grape) showing chalazal scar on dorsal side; o, Vitis vinifera (grape) showing two narrow and deep furrows on ventral side; p, Vicia sativa (common vetch); q, r, Coix lachryma-jobi (Job’s tear) (scale in mm) (after Pokharia et al. 2009: 564)Koldihwa (6500 BC)

Oryza sativa (Cultivated rice)

Lahuradeva (7000 BC)

Oryza rufipogon (Wild rice) and Oryza sativa (Cultivated rice)

Lahuradeva (5000-3000 BC)

Oryza sativa (rice); Triticum aestivum (bread-wheat); Triticum sphaero-coccum (dwarf-wheat); Hordeum vulgare (hulled barley); Lentil (Lens culinaris);

Jhusi (7000-6000 BC)

Oryza sativa (rice) Hordeum vulgare (hulled barley); Triticum aestivum (bread-wheat); Triticum sphaero-coccum (dwarf-wheat)

(1-2) Grains of domesticated rice, (3-4) husk surface of wild rice and (5) grains of wild rice, (6) Goosefoot (locally known as bathua in northern India, (7) grain of foxtail-millet, (8) seeds of catchfly, (9) grains of Mugwort, (10) Flatsedge, (11) Job’s-tear grain from Lahuradeva, 7000 BC (after Tewari et al. 2007-08).

Evidence for metalwork, Sarasvati Civilization

Over 8000 inscriptions of Indus Script deciphered in the following books:

![]()

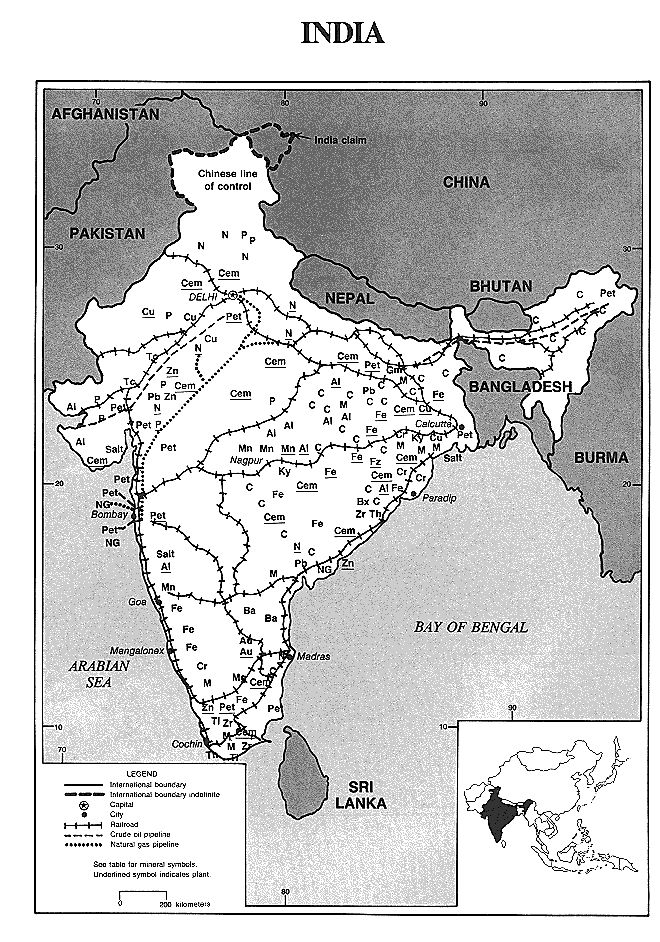

The distribution of minerals in India Jammu and Kashmir is part of India according to the United States Geological Survey

Magnetite ores of Sahyadri mountain ranges account for 47% of the country's reserves.