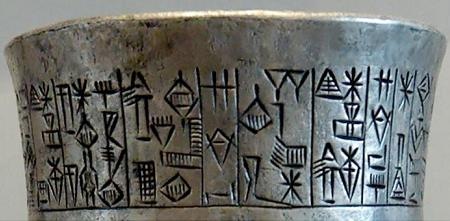

Three tokens were discovered in Kanmer with Indus Script inscriptions on both sides of the tokens. This monograph deciphers the inscriptionsand finds documentation of metalwork processes in furnace, alloying and smithy-forge. It is surmised that the three token set strung together may have resulted in the preparation on a seal of a bill of lading authenticating the products entrusted to the supercargo.

Location of Kanmer. Rann of Kuttch

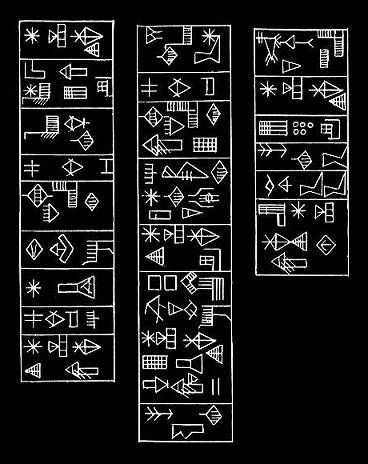

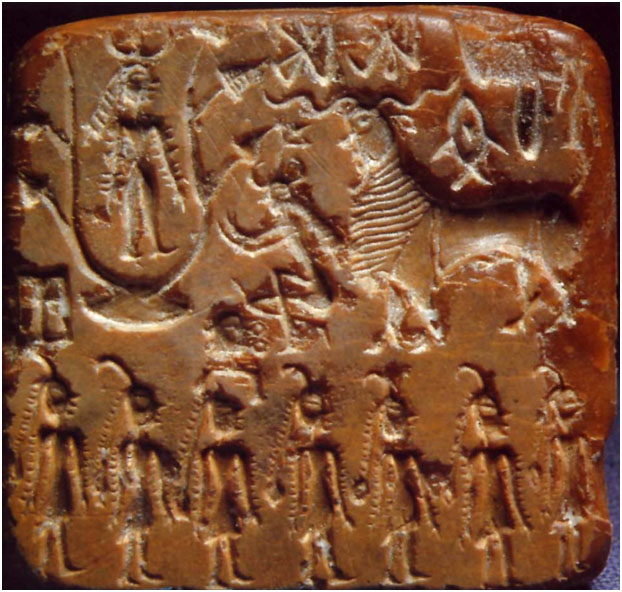

Three seal impressions of Kanmer are used on a string to constitute a set. The seal impressions are composed of the inscription:

Pictorial motif: khoṇḍ, kõda 'young bull-calf' खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) ‘Pannier’ glyph: खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’. कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) The pictorial motif is read rebus as: - کار کنده kār-kunda 'adroit, clever, experienced, director, manager' (Pashto)

Three such seal impressions on three tokens of Kanmer constitute the consolidated cargo to be compiled on a seal message.

khareḍo 'a currycomb' (G.) Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) Rebus: kharada

खरडें daybook

खरडें daybook PLUS kanahār 'helmsman'. Thus, helmsman's daybook.

कर्णक m. du. the two legs spread out AV. xx , 133 'spread legs'; (semantic determinant) Rebus: kanahār'helmsman', karNI 'scribe, account''supercargo'. कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: 'helmsman', karNi 'supercargo'; meṛed 'iron' rebus: meḍh 'merchant' ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; 2. कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: 'helmsman', karṇi 'supercargo' Indicative that the merchant is seafaring metalsmith. karṇadhāra m. ʻ helmsman ʼ Suśr. [

Kanmer seal with elephant pictorial motif PLUS

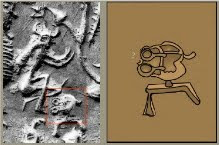

Kanmer seal with elephant pictorial motif PLUS  Sign 38 is a hypertext: khareḍo 'a currycomb' rebus kharada खरडें daybook PLUS karṇaka कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus kanahār 'helmsman'. Pictorial motif: karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron'. Thus, daybook of irnoworker, turner helmsman

Sign 38 is a hypertext: khareḍo 'a currycomb' rebus kharada खरडें daybook PLUS karṇaka कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus kanahār 'helmsman'. Pictorial motif: karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron'. Thus, daybook of irnoworker, turner helmsman

Source:Kharakwal, JS, YS Rawat and Toshiki Osada, Excavations at Kanmer: A Harappan site in Kachchh, Gujarat, Puratattva, Number 39, 2009

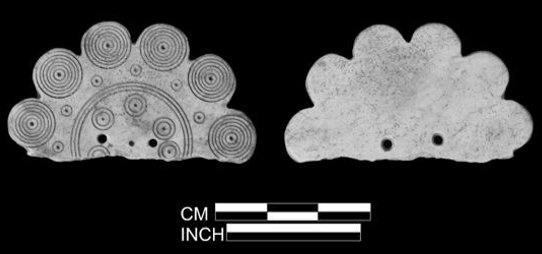

Obverse and reverse of Kanmer tokens. Reverse has three different inscriptions. Courtesy: Toshiki Osada

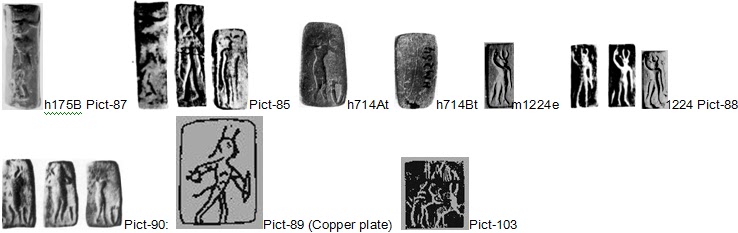

Token 1 of Kanmer

ayo, hako 'fish'; a~s = scales of fish (Santali); rebus: aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.)

Sign 343 kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman' PLUS खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'. Thus, khāṇḍā karṇī 'metalware supercargo'.

Thus, this token has the message that the cargo alloy metal product has been endorsed by the supercargo at the fire trench account stage of processing.

Token 2 of Kanmer

Alternative reading:

Reverse side of a clay "token" from Kanmer, Kutch, with incised signs depicting (from right to left) 'wild ass' and 'ladder' (photo by Indus Project of RIHN).

khara 'equus hemionus' rebus:khār 'blacksmith

śrēṣṭrī 'ladder' Rebus: seṭh ʻ head of a guild, Members of the guild (working with a furnace). Thus, guild-master of the guild of blacksmiths.

Kanmer seal impression as a token has two signs on the obverse which are repeated as a two-sign sequence on Khirsara tablet.

Khirsara tablet two-sign sequence. The sequence is read rebus: khara 'equus hemionus' rebus:khār 'blacksmith'

PLUS kuttuvā 'herring bone' rebus: kōḍa 'workshop'. Thus, together, blacksmith workshop. The same reading may relate to the obverse of Kanmer seal impression 'token'. (Many dialectical variant phonetic forms of kuttuvā 'herring bone' include: kuṭṭa, kuṭṭai 'knotty log, handcuffs', khoḍ ʻ trunk or stump of a tree ʼ, ˚ḍā m. ʻ stocks for criminals ʼ. Hence, the rebus reading kōḍa'workshop, place of work of artisans' is realised.

Three identical seal impressions of Kanmer are used on a string to constitute a set.

Token 3 of Kanmer

sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' ganda 'four' rebus: kanda 'equipment'

baṭa = a kind of iron (G .) baṭa = rimless pot (Kannada)

S. baṭhu m. ‘large pot in which grain is parched, large cooking fire’, baṭhī f. ‘distilling furnace’; L. bhaṭṭh m. ‘grain—parcher's oven’, bhaṭṭhī f. ‘kiln, distillery’, awāṇ. bhaṭh; P. bhaṭṭh m., °ṭhī f. ‘furnace’, bhaṭṭhā m. ‘kiln’; S. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ‘distil (spirits)’. (CDIAL 9656)

Thus, one of the three tokens signifies with an inscription on the reverse of the token, that the cargo of equipment has been subjected to furnace processes..

It is surmised that the three tokens with three distinct inscriptions signify stages of metalwork processes: 1. furnace work; 2. alloying work; 2. blacksmith workshop (smithy, forge). The three tokens strung together would have been consolidated as cargo with an inscription on a seal handed over to the supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.

3.. Conclusive proof from Kharaputta-Jātaka and Kanmer seal for khara as equus hemionus which draws a royal chariot; rebus khār 'blacksmith' https://tinyurl.com/y3xa9vmu

4. Design principles of pictographic Indus Script, gleaned from 'unicorn', 'rim-of-jar' https://tinyurl.com/yya6g9gf

![]() Khirsara1a tablet

Khirsara1a tablet

Decipherment:Hypertext of ![]() Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS

Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS![]() Sign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace'

Sign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace'

khara 'equus hemionus' rebus:khār 'blacksmith [Alternative: ranku ‘antelope’; rebus: ranku ‘tin’ (Santali)]

śrēṣṭrī 'ladder' Rebus: seṭh ʻ head of a guild, Members of the guild (working with a furnace). [Alternative: panǰā́r ‘ladder, stairs’ (Bshk.)(CDIAL 7760) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)]

Thus, guild-master of the guild of blacksmiths.

badhi ‘to ligature, to bandage, to splice, to join by successive rolls of a ligature’ (Santali) batā bamboo slips (Kur.); bate = thin slips of bamboo (Malt.)(DEDR 3917). Rebus: baḍhi = worker in wood and metal (Santali) baṛae = blacksmith (Ash.)

kolmo ‘three’ (Mu.); rebus: kolimi ‘smithy’ (Te.)

khaṇḍ ‘division’; rebus: kaṇḍ ‘furnace’ (Santali) khaḍā ‘circumscribe’ (M.); Rebs: khaḍā ‘nodule (ore), stone’ (M.)

bharna = the name given to the woof by weavers; otor bharna = warp and weft (Santali.lex.) bharna = the woof, cross-thread in weaving (Santali); bharni_ (H.) (Santali.Boding.lex.) Rebus: bhoron = a mixture of brass and bell metal (Santali.lex.) bharan = to spread or bring out from a kiln (P.lex.) bha_ran. = to bring out from a kiln (G.) ba_ran.iyo = one whose profession it is to sift ashes or dust in a goldsmith’s workshop (G.lex.) bharant (lit. bearing) is used in the plural in Pan~cavim.s’a Bra_hman.a (18.10.8). Sa_yan.a interprets this as ‘the warrior caste’ (bharata_m – bharan.am kurvata_m ks.atriya_n.a_m). *Weber notes this as a reference to the Bharata-s. (Indische Studien, 10.28.n.2)

kuṭi = a slice, a bit, a small piece (Santali.lex.Bodding) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘iron smelter furnace’ (Santali)

Hieroglyph ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article'

meḍhi 'plait' meḍ 'iron'; daürā 'rope' Rebus dhāvḍā 'smelter'

kṣōḍa m. ʻ post to which an elephant is fastened ʼ lex. [Poss. conn. with *

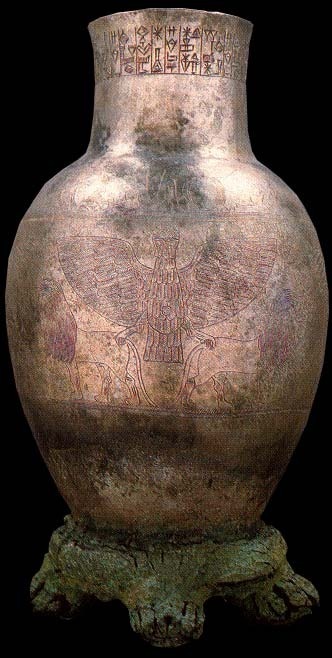

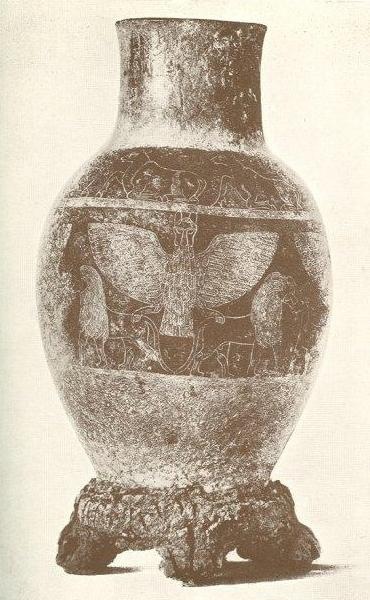

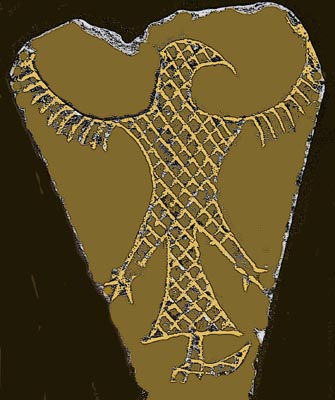

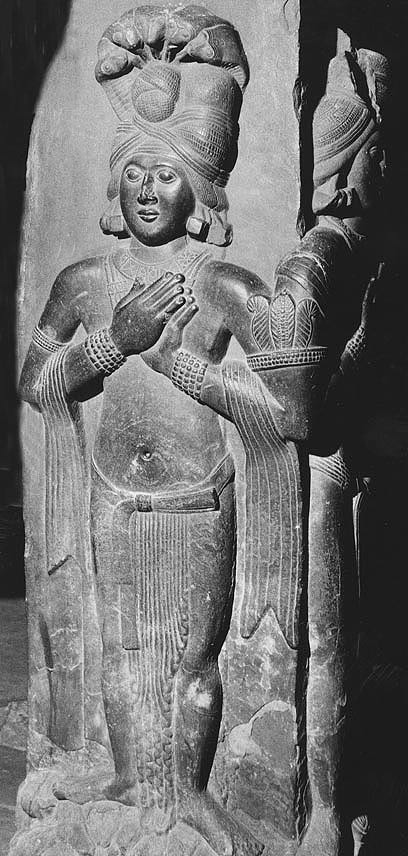

Hittite, seal, hare and two eagles, Boğazköy,, 1800 BC, Museum of Anatolian Civilisations, Ankara.

Hittite, seal, hare and two eagles, Boğazköy,, 1800 BC, Museum of Anatolian Civilisations, Ankara.

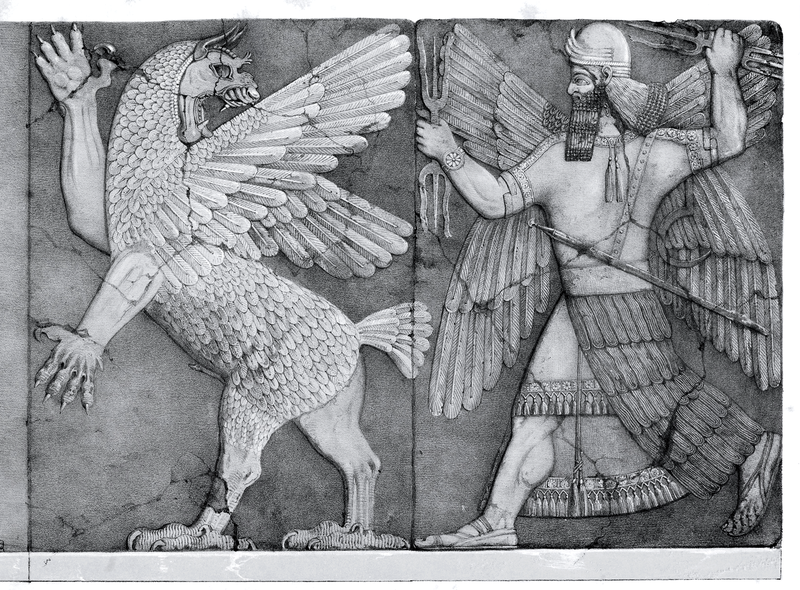

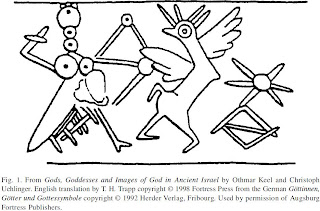

kambha'wing' rebus: kammaṭa'mint' PLUS kola'tiger' rebus; kol 'working in iron' PLUS baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi 'artisans who work both in iron and wood' PLUS śyena, 'eagle' rebus 1) śeṇvi 'general', 2) sena 'thunderbolt'. (i.e. gaṇḍa 'hero' PLUS भेरुण्ड 'formidable').

kambha'wing' rebus: kammaṭa'mint' PLUS kola'tiger' rebus; kol 'working in iron' PLUS baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi 'artisans who work both in iron and wood' PLUS śyena, 'eagle' rebus 1) śeṇvi 'general', 2) sena 'thunderbolt'. (i.e. gaṇḍa 'hero' PLUS भेरुण्ड 'formidable'). On this artifact, eagle,

On this artifact, eagle,

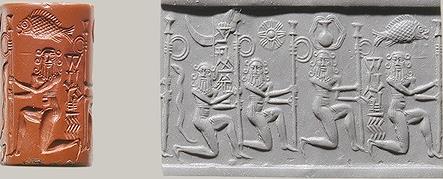

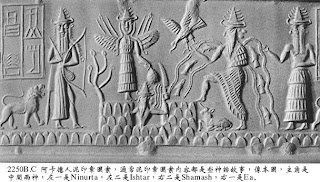

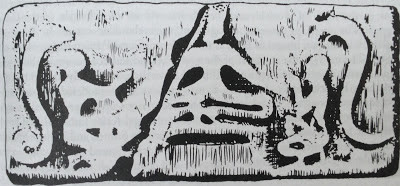

This etymon indicates the possible reading of the tall flagpost carried by kneeling persons with six locks of hair: baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'. Associated with nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

This etymon indicates the possible reading of the tall flagpost carried by kneeling persons with six locks of hair: baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'. Associated with nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead' Emblem in Mysuru palace.

Emblem in Mysuru palace.

A

A

British Museum.

British Museum.

Sumer. Sculptural friezes.

Sumer. Sculptural friezes.

Zu or Anzu (from An 'heaven' and Zu 'to know' in Sumerian language), as a lion-headed eagle, ca. 2550–2500 BCE,

Zu or Anzu (from An 'heaven' and Zu 'to know' in Sumerian language), as a lion-headed eagle, ca. 2550–2500 BCE,

Persepolis stone homa birds, double protome column capital See:

Persepolis stone homa birds, double protome column capital See:

Hettiter, seal, Acem Höyük (Kurt Bittel) (Erdinç Bakla archive)

Hettiter, seal, Acem Höyük (Kurt Bittel) (Erdinç Bakla archive) Hittite, two bird man, Kargamış, Museum of Anatolian Civilization, Ankara

Hittite, two bird man, Kargamış, Museum of Anatolian Civilization, Ankara

Water flowing from the shoulders of a person with a step on the mountain range also shows swimming fishes. The Meluhha words to signify the hypertexts are: aya'fish' PLUS काण्ड

Water flowing from the shoulders of a person with a step on the mountain range also shows swimming fishes. The Meluhha words to signify the hypertexts are: aya'fish' PLUS काण्ड

Santali glosses. Lexis.

Santali glosses. Lexis.

The two hieroglyphs show an identical palm frond with two hanging twigs or fronds as the centerpiece of an altar in front of both the male and female divinities. The male divinity is a builder holding a staff and bob plumb bob as perceptively noted by Jenny Vorys Canby whose painstaking researches resulted in a reasonable reconstruction of missing fragments of the stela. A major missing part unearthed by Canby is another hieroglyph: overflowing pots pouring into the center-piece altars with the palm fronds.

The two hieroglyphs show an identical palm frond with two hanging twigs or fronds as the centerpiece of an altar in front of both the male and female divinities. The male divinity is a builder holding a staff and bob plumb bob as perceptively noted by Jenny Vorys Canby whose painstaking researches resulted in a reasonable reconstruction of missing fragments of the stela. A major missing part unearthed by Canby is another hieroglyph: overflowing pots pouring into the center-piece altars with the palm fronds.

On this cylinder seal, the flagposts with rings are shown together with hieroglyphs of: a person carrying an antelope (like the hioeroglyph shown on Shu-ilishu Meluhha translator cylinder seal), overflowing water, fishes, crucible, mountain range, sun (Source:

On this cylinder seal, the flagposts with rings are shown together with hieroglyphs of: a person carrying an antelope (like the hioeroglyph shown on Shu-ilishu Meluhha translator cylinder seal), overflowing water, fishes, crucible, mountain range, sun (Source:

Patanjali

Patanjali

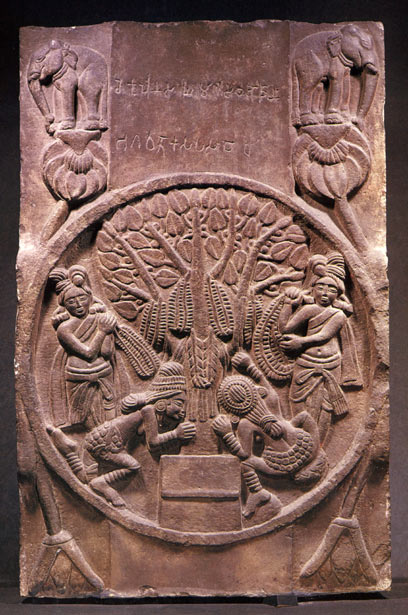

Amaravati. Sculptural frieze. A face (of an artisan) emrges ou of tree trunk within vedika, sacred railing. A worshipper carries three strands (of a rope):

Amaravati. Sculptural frieze. A face (of an artisan) emrges ou of tree trunk within vedika, sacred railing. A worshipper carries three strands (of a rope):

![clip_image057[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0574-thumb.jpg?w=80&h=68)

m1186

m1186

![clip_image062[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0624-thumb.jpg?w=99&h=45)

m290 tiger in front of a feeding trough

m290 tiger in front of a feeding trough

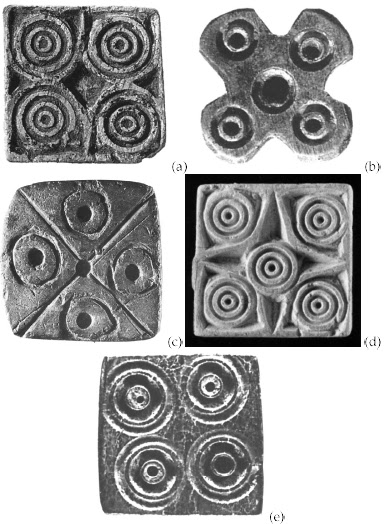

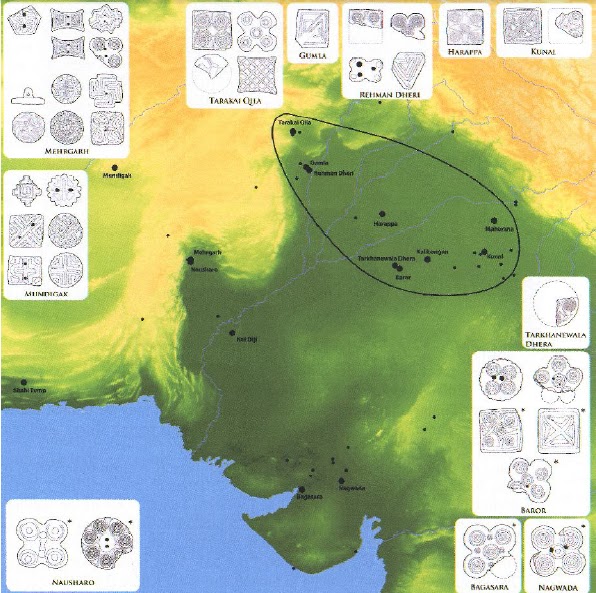

On this Kot Diji phase steatite button seal from Harappa (H2000-4495 / 9597-01), traces of blue-green glaze can be seen (upper center and left center). Similar seals have been found at other Kot Diji period sites and even in distant Central Asia.

On this Kot Diji phase steatite button seal from Harappa (H2000-4495 / 9597-01), traces of blue-green glaze can be seen (upper center and left center). Similar seals have been found at other Kot Diji period sites and even in distant Central Asia.