https://tinyurl.com/y4f8v2yc

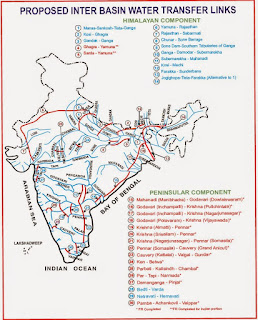

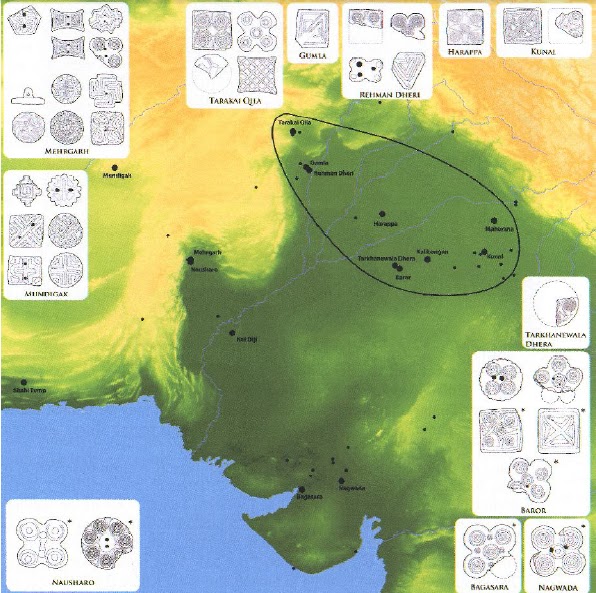

-- Ancient Maritime Tin Route linking Hanoi and Haifa posited.

-- Why Was Rakhigarhi capital of the Civilization?

-- Location on the water-divide, linking Brahmaputra-Ganga-Yamuna-Sarasvati Navigable Waterways and Persian Gulf, Indian Ocean Ancient Maritime Tin-Copper Route of the Bronze Age Revolution

![]()

Discovering 'buried' channels of the Palaeo-Yamuna river in NW India-- Imran Khan, Rajiv Sinha (2019) https://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2019/05/discovering-buried-channels-of-palaeo.html … --Or, how Rakhigarhi, capital of the civilization linked Ganga-Yamuna-Sarasvati waterways

![a-general-view-of-khetri-copper-complex-in-rajasthan]()

![Khetri, Shekhawati]()

-- Ancient Maritime Tin Route linking Hanoi and Haifa posited.

-- Why Was Rakhigarhi capital of the Civilization?

-- Location on the water-divide, linking Brahmaputra-Ganga-Yamuna-Sarasvati Navigable Waterways and Persian Gulf, Indian Ocean Ancient Maritime Tin-Copper Route of the Bronze Age Revolution

Discovering 'buried' channels of the Palaeo-Yamuna river in NW India-- Imran Khan, Rajiv Sinha (2019) https://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2019/05/discovering-buried-channels-of-palaeo.html … --Or, how Rakhigarhi, capital of the civilization linked Ganga-Yamuna-Sarasvati waterways

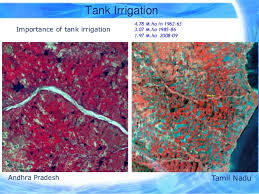

Khetri.

1975 - THE $152 MILLION KHETRI COMPLEX INCLUDES TWO MINES, ONE AT KHETRI AND ANOTHER AT KOLIHAN, A CONCENTRATOR, A SMELTER AND AN ELECTROLYTIC REFINERY. ORE RESERVES ARE EST- IMATED AT 47 MILLION METRIC TONS AT 0.72% COPPER AT KHETRI AND 29 METRIC TONS/YEAR OF 1.56% COPPER AT KOLIHAN. PRO- DUCTION FOR 1974-1975 SHOULD BE ABOUT 3600 METRIC TONS OF REFINED COPPER WITH AN INCREASE TO 8000 METRIC TONS/YEAR OF REFINED COPPER BY 1978-1979. THE FACILITY WILL HAVE AN EX- PECTED CAPACITY OF 31,000 METRIC TONS/YEAR OF REFINED COP- PER. 1974 - THE SITE IS SERVED BY ROAD FORM DELHI AND JAIPUR AND BY RAIL WITH THE DELHI-AHMEDABAD LINE. ELECTRIC POWER IS SUPPLIED BY THE RAJASTHAN STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD. NINE MILLION GALLONS OF WATER/DAY ARE SUPPLIED VIA 30 TUBE WELLS 30 MILES AWAY. THE COMPLEX EMPLOYS 7000 PERSONS. https://thediggings.com/mines/usgs10231314

Khetri Shekhawati

![Image result for khetri mines]()

![Related image]()

![Image result for khetri mines]()

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10230-018-00582-1

![Image result for khetri mines]()

![]()

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10230-018-00582-1

https://tinyurl.com/yyeyfkxu

This is an addendum to:

Trade contacts with Meluhha artisans in Mari for tin-bronze production in Mesopotamia proven by provenance studies and cuneiform texts http://tinyurl.com/yxhfgnll whch included the following Abstract from Iranica Antiqua, 2009:

I am grateful to Prof. Nilesh Oak for identifying a brilliant piece of archaeometallurgical provenance study which links Khetri copper mines --through Dholavira/Lothal and Persian Gulf -- with Mesopotamia.

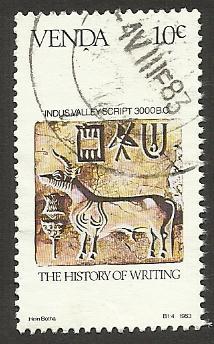

The jury is still out on the source of tin for the tin-bronze revolution. It appears that Ancient Indian artisans/merchants mediated in transferring tin ingots to ANE evidenced by four pure tin ingots found in a Haifa shipwreck, with Indus Script inscriptions which read: ranku dhātu mũh 'tin mineral ingot'.

This is an addendum to:

Trade contacts with Meluhha artisans in Mari for tin-bronze production in Mesopotamia proven by provenance studies and cuneiform texts http://tinyurl.com/yxhfgnll whch included the following Abstract from Iranica Antiqua, 2009:

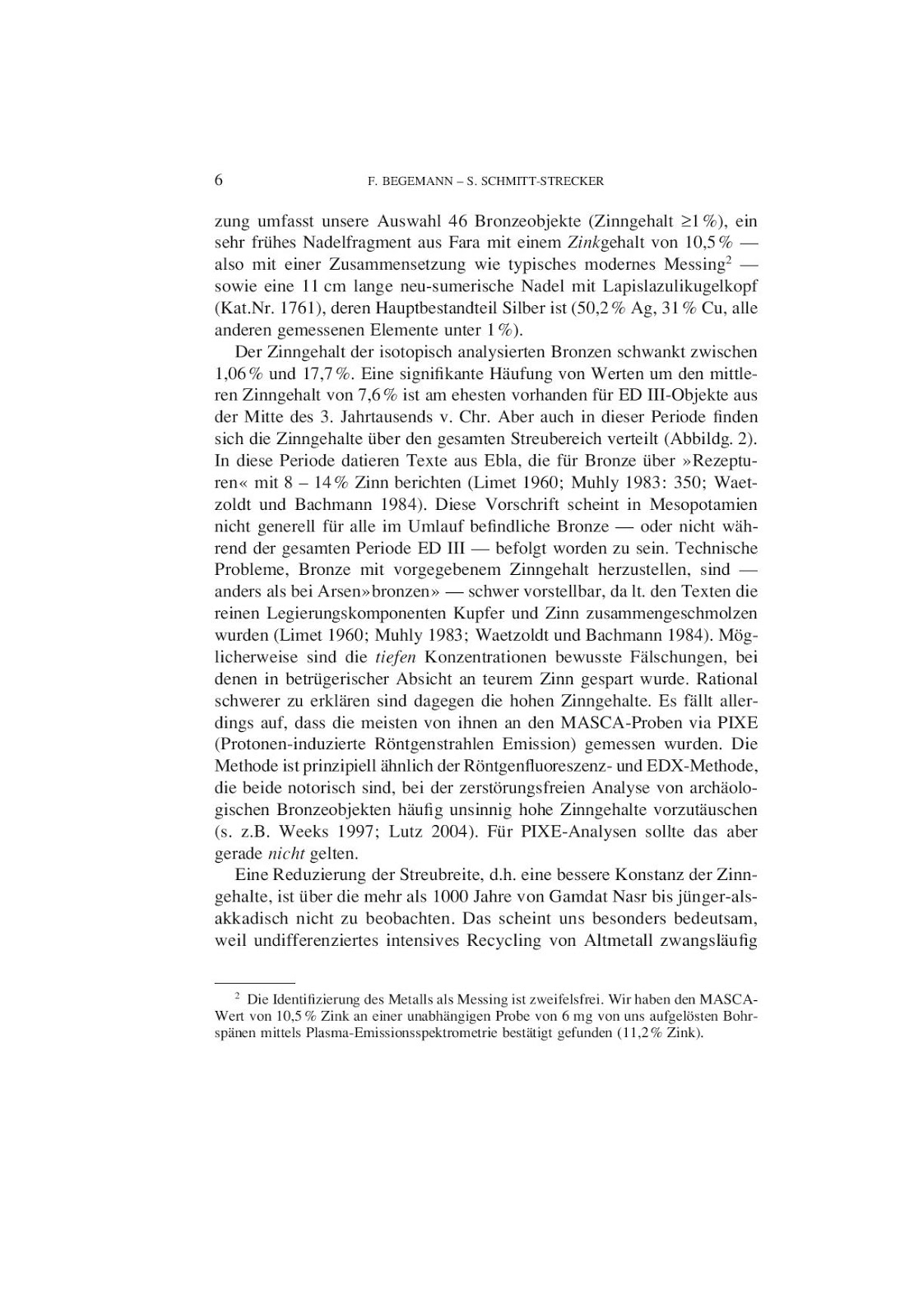

Copper from Gujarat used in Mesopotmia, 3rd millennium BCE, evidenced by lead isotope analyses of tin-bronze objects; report by Begemann F. et al.

- Author(s): BEGEMANN, F. , SCHMITT-STRECKER, S.

Journal: Iranica Antiqua

Volume: 44 Date: 2009

Pages: 1-45

DOI: 10.2143/IA.44.0.2034374 - Abstract :

A lIranica Antiqua

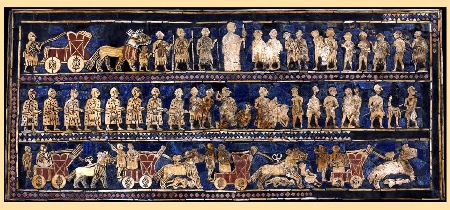

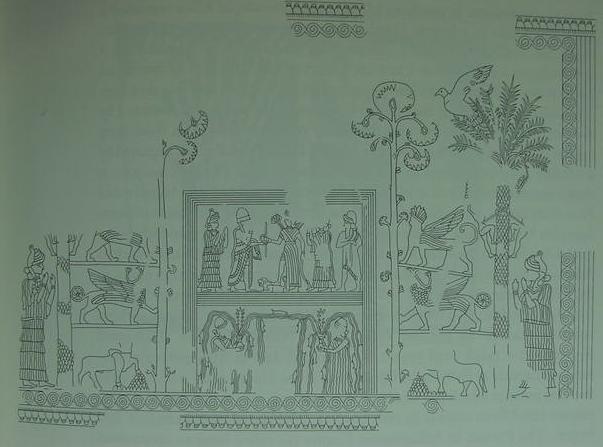

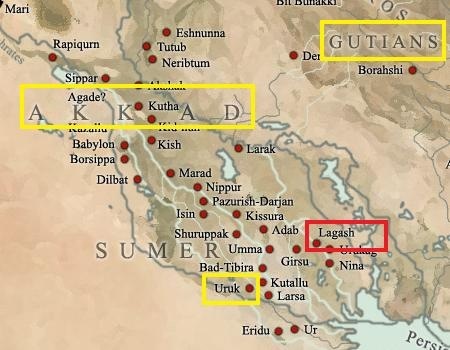

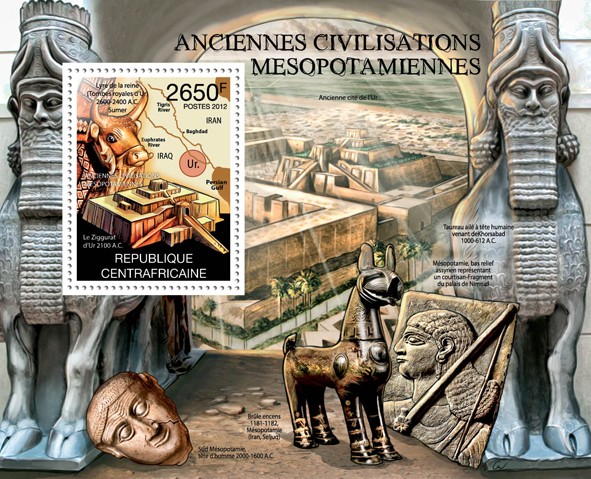

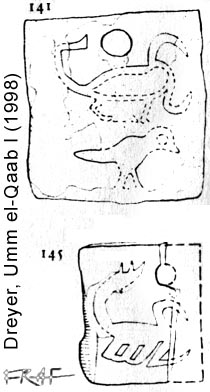

- Geographical locations of sites of Mesopotamia from which artifacts were analyzed in this work (After Fig. 1 in Begemann, F. et al, 2009 loc.cit.) The conclusion is: "Unsere bleiisotopische evidenz legt nahe, das in Mesopotamien fur legierung mit zinn verwendete kupfer urudu-luh-ha stamme aus Indien, was ebenfalls vertraglich ist mit einem import via dilmun." (Trans. Our lead isotope evidence suggests that the urudu-luh-ha copper used in Mesopotamia for tin alloying is from India, which is also contracted with an import via Dilmun.)" (opcit., p.28)

- A lead isotope study »On the Early copper of Mesopotamia« reports on copper-base artefacts ranging in age from the 4th millennium BC (Uruk period) to the Akkadian at the end of the 3rd millennium BC. Arguments are presented that, in the (tin)bronzes, the lead associated with the tin used for alloying did not contribute to the total in any detectable way. Hence, the lead isotopy traces the copper and cannot address the problem of the provenance of tin. The data suggest as possible source region of the copper a variety of ore occurrences in Anatolia, Iran, Oman, Palestine and, rather unexpectedly (by us), from India. During the earliest period the isotopic signature of ores from Central and North Anatolia is dominant; during the next millennium this region loses its importance and is hardly present any more at all. Instead, southeast Anatolia, central Iran, Oman, Feinan-Timna in the rift valley between Dead Sea and Red Sea, and sources in the Caucasus are now potential suppliers of the copper. Generally, an unambiguous assignment of an artefact to any of the ores is not possible because the isotopic fingerprints of ore occurrences are not unique. In our suite of samples bronze objects become important during ED III (middle of the 3rd millennium BC) but they never make up more than 50 % of the total. They are distinguished in their lead isotopy by very high 206Pb-normalized abundance ratios. As source of such copper we suggest Gujarat/Southern Rajasthan which, on general grounds, has been proposed before to have been the most important supplier of copper in Ancient India. We propose this Indian copper to have been arsenic-poor and to be the urudu-luh-ha variety which is one of the two sorts of purified copper mentioned in contemporaneous written texts from Mesopotamia to have been in circulation there concurrently.

- Author(s): BEGEMANN, F. , SCHMITT-STRECKER, S.

Journal: Iranica Antiqua

Volume: 44 Date: 2009

Pages: 1-45

DOI: 10.2143/IA.44.0.2034374 - Abstract :

A lIranica Antiqua

Geographical locations of sites of Mesopotamia from which artifacts were analyzed in this work (After Fig. 1 in Begemann, F. et al, 2009 loc.cit.) The conclusion is: "Unsere bleiisotopische evidenz legt nahe, das in Mesopotamien fur legierung mit zinn verwendete kupfer urudu-luh-ha stamme aus Indien, was ebenfalls vertraglich ist mit einem import via dilmun." (Trans. Our lead isotope evidence suggests that the urudu-luh-ha copper used in Mesopotamia for tin alloying is from India, which is also contracted with an import via Dilmun.)" (opcit., p.28)

A lead isotope study »On the Early copper of Mesopotamia« reports on copper-base artefacts ranging in age from the 4th millennium BC (Uruk period) to the Akkadian at the end of the 3rd millennium BC. Arguments are presented that, in the (tin)bronzes, the lead associated with the tin used for alloying did not contribute to the total in any detectable way. Hence, the lead isotopy traces the copper and cannot address the problem of the provenance of tin. The data suggest as possible source region of the copper a variety of ore occurrences in Anatolia, Iran, Oman, Palestine and, rather unexpectedly (by us), from India. During the earliest period the isotopic signature of ores from Central and North Anatolia is dominant; during the next millennium this region loses its importance and is hardly present any more at all. Instead, southeast Anatolia, central Iran, Oman, Feinan-Timna in the rift valley between Dead Sea and Red Sea, and sources in the Caucasus are now potential suppliers of the copper. Generally, an unambiguous assignment of an artefact to any of the ores is not possible because the isotopic fingerprints of ore occurrences are not unique. In our suite of samples bronze objects become important during ED III (middle of the 3rd millennium BC) but they never make up more than 50 % of the total. They are distinguished in their lead isotopy by very high 206Pb-normalized abundance ratios. As source of such copper we suggest Gujarat/Southern Rajasthan which, on general grounds, has been proposed before to have been the most important supplier of copper in Ancient India. We propose this Indian copper to have been arsenic-poor and to be the urudu-luh-ha variety which is one of the two sorts of purified copper mentioned in contemporaneous written texts from Mesopotamia to have been in circulation there concurrently.

Trade contacts with Meluhha artisans in Mari for tin-bronze production in Mesopotamia proven by provenance studies and cuneiform texts http://tinyurl.com/yxhfgnll

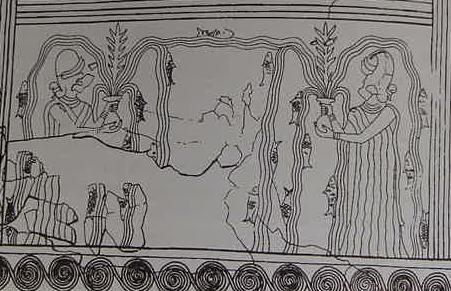

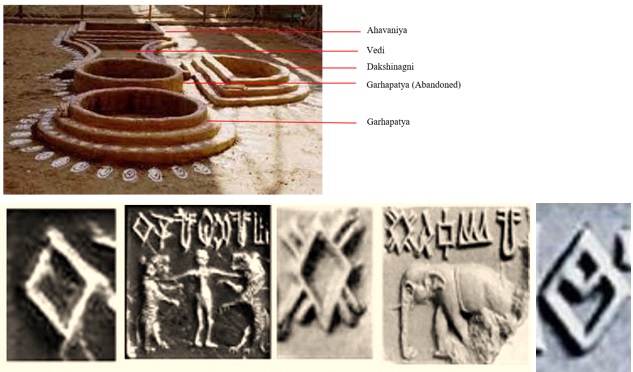

I posit that, as argued in the above-cited monograph that the largest tin belt of the globe was in the river basins of Himalayan rivers Mekong, Irrawaddy and Salween which powered the Tin-Bronze Revolution of 3rd millennium BCE, evidenced in Mesopotamia. These rivers ground down granite rocks to accumulate placer deposits of cassiterite (tin ore) in these river basins thus facilitating an Ancient Maritime Tin Route which linked AFEwith ANE.

![]()

Map showing the location of known tin deposits exploited during ancient times

The jury is still out on the source of tin for the tin-bronze revolution. It appears that Ancient Indian artisans/merchants mediated in transferring tin ingots to ANE evidenced by four pure tin ingots found in a Haifa shipwreck, with Indus Script inscriptions which read: ranku dhātu mũh 'tin mineral ingot'.

It is likely that the tin used in Mesopotamia tin bronzes were also the tin routed from the largest tin belt of the globe (Mekong,Irrawaddy-Salween river basins) of Ancient Far East mediated by Indian merchant guilds. Our archaeometallurgists should launch a project to prove the source of tin which powered the First Tin-Bronze AgeIndustrial Revolution.

Sources:The ingots are in the Haifa Museum. 1. Madden R., Wheeler, I. and Muhly JD, 1977, Tin in the ancient near east: old questions and new finds, Expedition 19, pp. 45-47.

2. Michal Artzy, 1983, Arethusa of the Tin ingot, in Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 250 (Spring, 1983), pp. 51-55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1356605 (embedded in this monograph for ready reference).

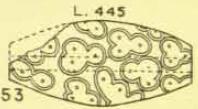

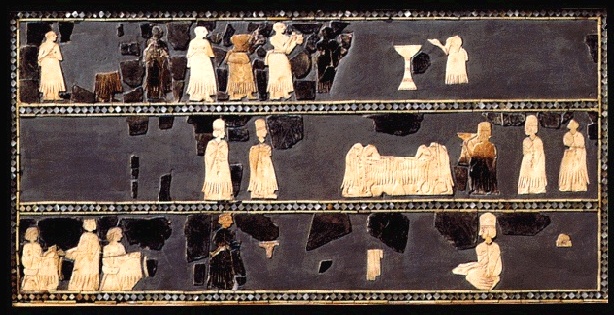

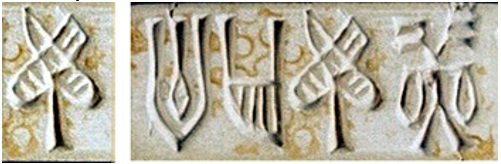

After the publication in 1977, of the two pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck at Haifa, Artzy published in 1983 (p.52), two more ingots found in a car workshop in Haifa which wasusing the ingots for soldering broken radiators. Artzy's finds were identical in size and shape with the previous two; both were also engraved with two marks. In one of the ingots, at the time of casting, a moulded head was shown in addition to the two marks. Artzy compares this head to Arethusa. (Artzy, M., 1983, Arethusa of the Tin Ingot, Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research, 250, p. 51-55). Artzy went on to suggest the ingots may have been produced in Iberia and disagreed with the suggestion that the ingot marks were Cypro-Minoan script.

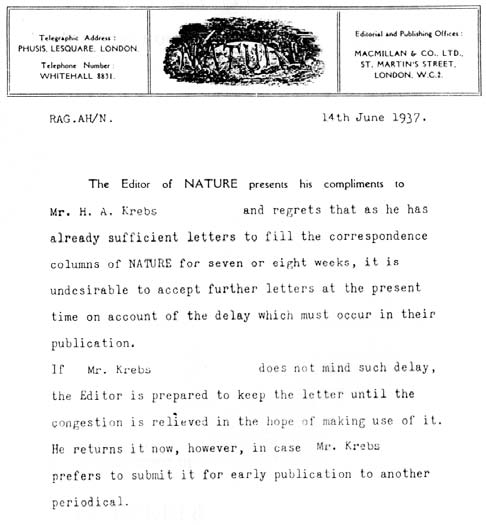

My decipherment appeared in Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies.

My monograph on this conclusion has been published in Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies, Vol. 1, Number 11 (2010), pp.47-74 — The Bronze Age Writing System of Sarasvati Hieroglyphics as Evidenced by Two “Rosetta Stones” By S. Kalyanaraman (Editor of JIJS: Prof. Nathan Katz)http://www.indojudaic.com/index.php?option=com_contact&view=contact&id=1&Itemid=8

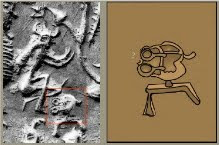

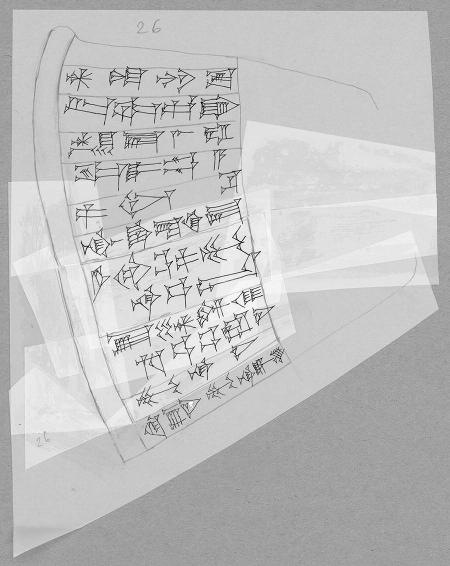

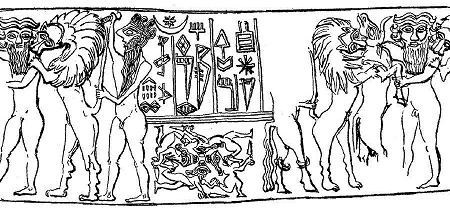

The author Michal Artzy (opcit., p. 55) who showed these four signs on the four tin ingots to E. Masson who is the author of Cypro-Minoan Syllabary. Masson’s views are recorded in Foot Note 3: “E. Masson, who was shown all four ingots for the first time by the author, has suggested privately that the sign ‘d’ looks Cypro-Minoan, but not the otherthree signs.”

If all the signs are NOT Cypro-Minoan Syllabary, what did these four signs, together, incised on the tin ingots signify?

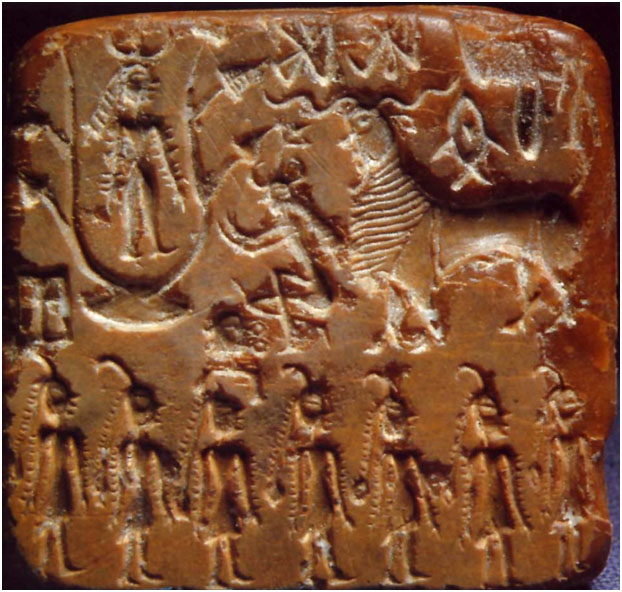

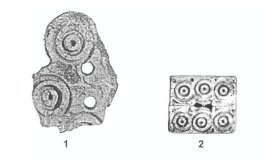

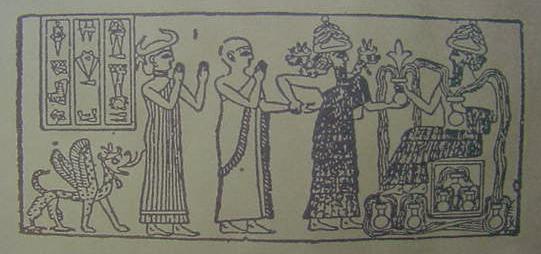

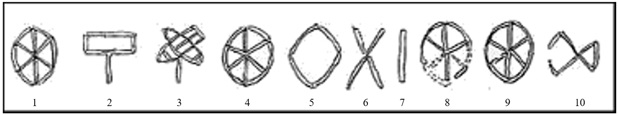

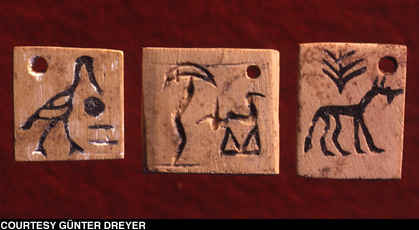

All these hieroglyphs on the three tin ingots of Haifa are read rebus in Meluhha:

Hieroglyph: ranku = liquid measure (Santali)

Hieroglyph: raṅku m. ʻa species of deerʼ Vās., rankuka id., Śrīkaṇṭh. (Samskrtam)(CDIAL 10559). raṅku m. ʻ a species of deer ʼ Vās., °uka -- m. Śrīkaṇṭh.Ku. N. rã̄go ʻ buffalo bull ʼ? -- more prob. < raṅká-<-> s.v. *rakka -- .*raṅkha -- ʻ defective ʼ see *rakka -- .RAṄG ʻ move to and fro ʼ: ráṅgati. -- Cf. √riṅg, √rikh2, √*righ.(CDIAL 10559)

Rebus: ranku ‘tin’ (Santali) raṅga3 n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. Pk. raṁga -- n. ʻ tin ʼ; P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m.ʻpewter, tinʼ (← H.); Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼ, gng. rã̄k; N. rāṅ, rāṅo ʻ tin, solder ʼ, A. B. rāṅ; Or. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; Si. ran̆ga ʻ tin ʼ. (CDIAL 10562)

Hieroglyph: dāṭu = cross (Telugu)

Rebus: dhatu = mineral ore (Santali) Rebus: dhāṭnā ‘to send out, pour out, cast (metal)’ (Hindi)(CDIAL 6771).

Hieroglyph: mũh 'a face' Rebus: mũh, 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time from the furnace’ (Santali)

Indus Script hypertexts thus read: Hieroglyphs: ranku 'liquid measure' or raṅku ʻa species of deerʼ PLUS dāṭu = cross rebus: plain text: ranku 'tin' PLUS dhatu 'cast mineral' Thus, together, the plain text reads: tin mineral casting. The fourth ingot with the hieroglyph of a moulded head reads: mũh 'a face' Rebus: mũh, 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time from the furnace’ (Santali).

Thus, together, the message on the tin ingots discovered in the Haifa shipwreck is: ranku dhatu mũh 'tin mineral ingot'.

I ave posited an Ancient Maritime PLUS Himalayan Waterway Maritime Tin Route from Hanoi to Haifa, a trade route which predated the Silk Road by 2 millennia and be able to explain the Angus Madison bar chart which showed India accounting for 33% of Global GDP in 1 CE,mediated by ancient guilds of India.

See:

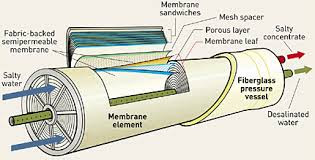

The full text of the article from ranica Antiqua Volume: 44 Date: 2009

Pages: 1-45 is appended only for purposes of ready reference to buttress the arguments of this note related to 'Early copper of Mesopotamia' which seems to have arrived from Khetri Mines of India through Dholavira/Lothal ports and the Persian Gulf. Unfortunately, the archaeometallurgical provenance study could not advance on the source of tin in the Tin-Bronzes of Mesopotamia.

See:

Challenge of matching Indus Script hypertexts & identifying tin isotope fingerprints of Ancient Maritime Tin Route from Hanoi to Haifa https://tinyurl.com/ybg3auhg

Pages: 1-45 is appended only for purposes of ready reference to buttress the arguments of this note related to 'Early copper of Mesopotamia' which seems to have arrived from Khetri Mines of India through Dholavira/Lothal ports and the Persian Gulf. Unfortunately, the archaeometallurgical provenance study could not advance on the source of tin in the Tin-Bronzes of Mesopotamia.

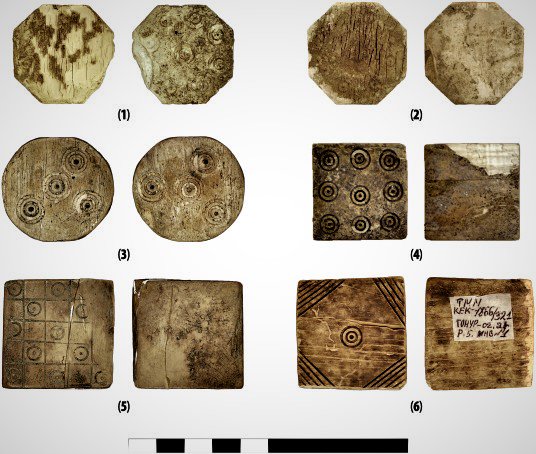

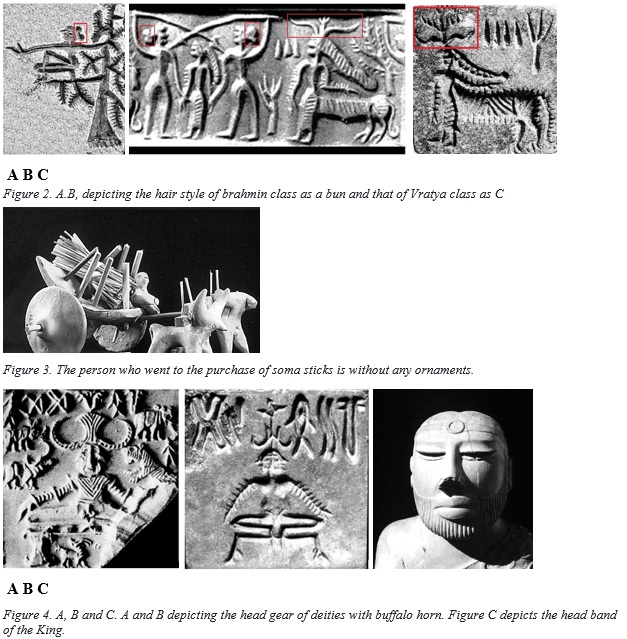

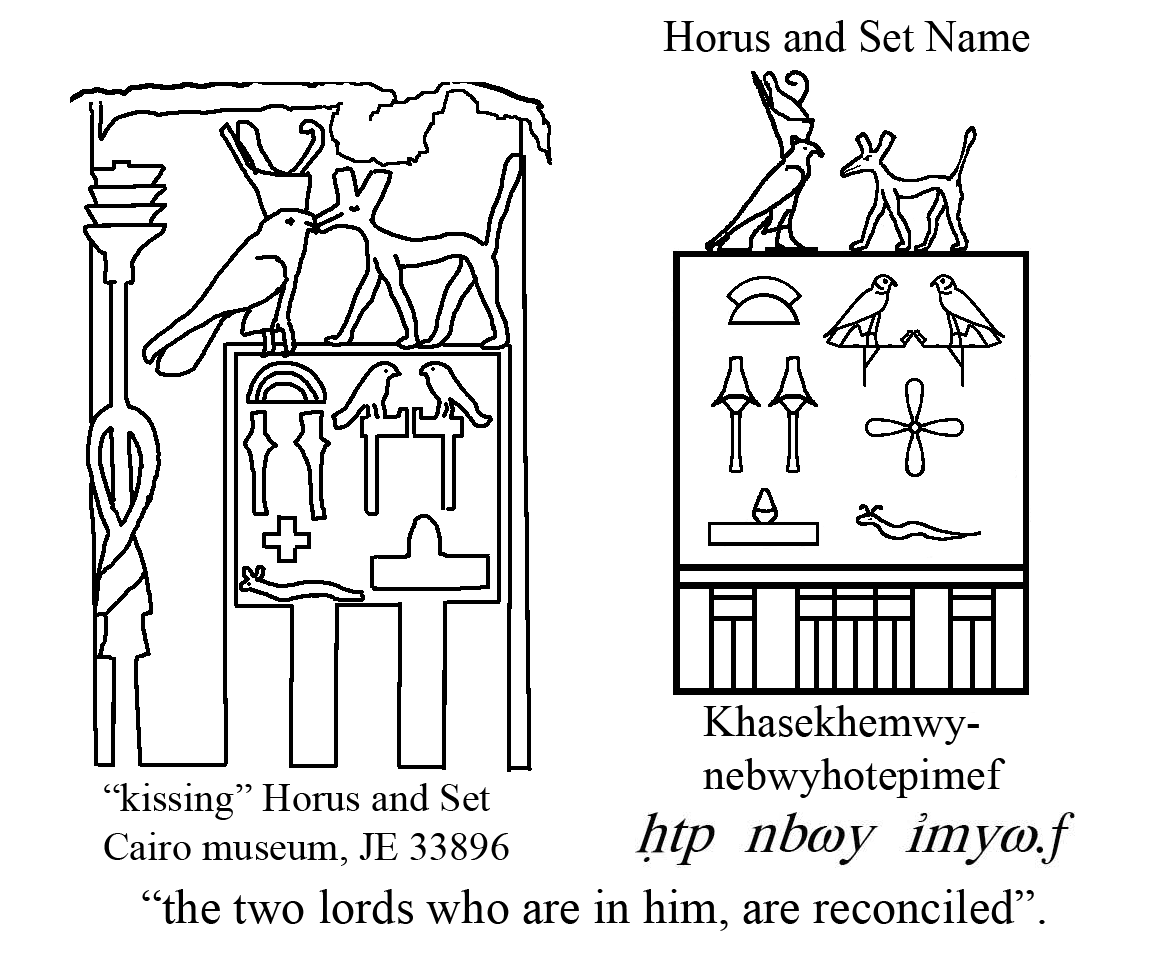

m1186

m1186

![clip_image062[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0624-thumb.jpg?w=99&h=45)

Buffalo. Mohenjo-daro.

Buffalo. Mohenjo-daro.

![clip_image025[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0254-thumb.jpg?w=86&h=80)

![clip_image054[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0544-thumb.jpg?w=104&h=32)

![clip_image055[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0554-thumb.jpg?w=104&h=32)

![clip_image057[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0574-thumb.jpg?w=80&h=68)

Santali glosses

Santali glosses

![clip_image033[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0334-thumb.jpg?w=71&h=44)

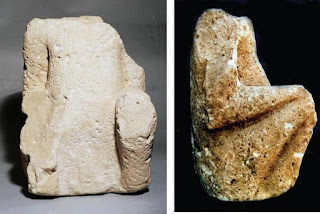

Mohenjo-daro Seated person (Head missing)

Mohenjo-daro Seated person (Head missing)

Gold f

Gold f

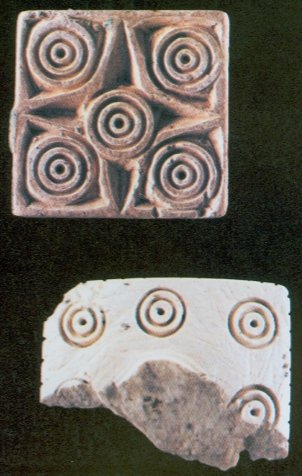

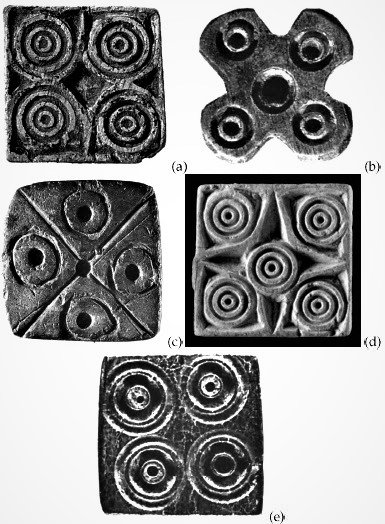

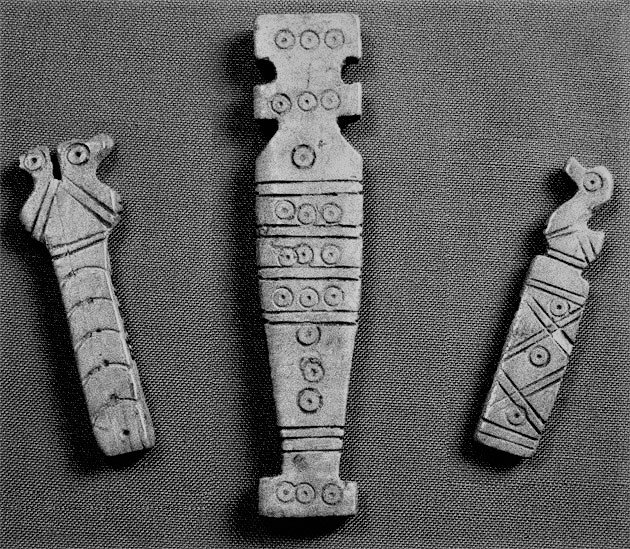

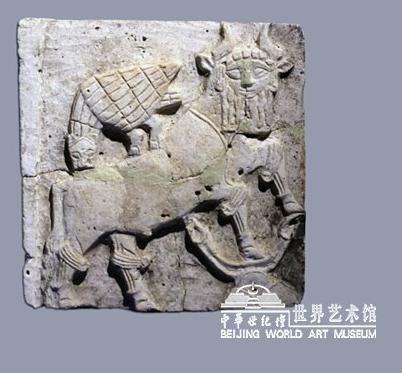

Artifacts from Jiroft.

Artifacts from Jiroft.

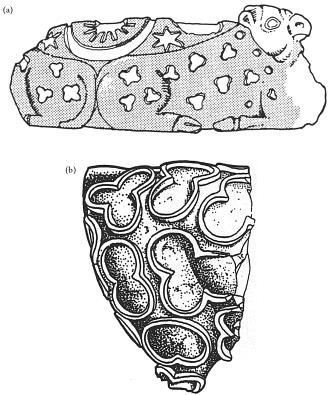

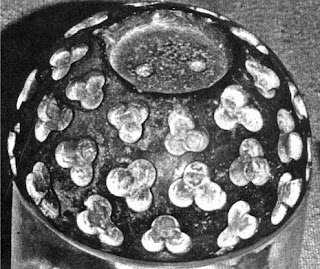

Crete. Cow-head rhython with trefoil decor.

Crete. Cow-head rhython with trefoil decor. Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit

Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit

Notes:

Notes:

Mohenjo-daro. m1656. Pectoral. Together with the hieroglyphs of a young bull, one-horned with pannier in front of a standard device, the expression signified is a pot overflowing with water.

Mohenjo-daro. m1656. Pectoral. Together with the hieroglyphs of a young bull, one-horned with pannier in front of a standard device, the expression signified is a pot overflowing with water.

Ziziphus (jujube) is called

Ziziphus (jujube) is called

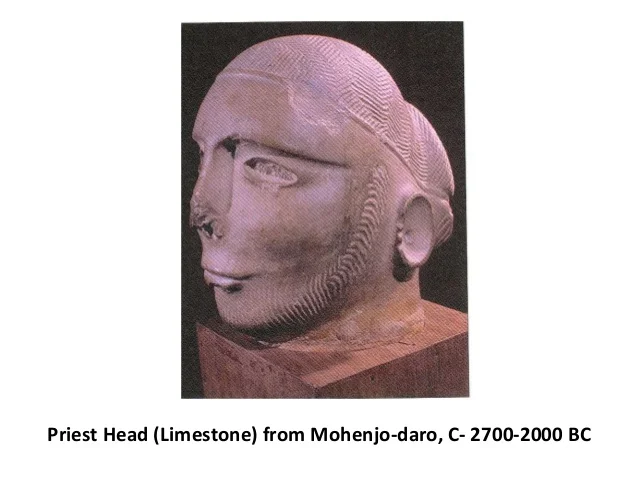

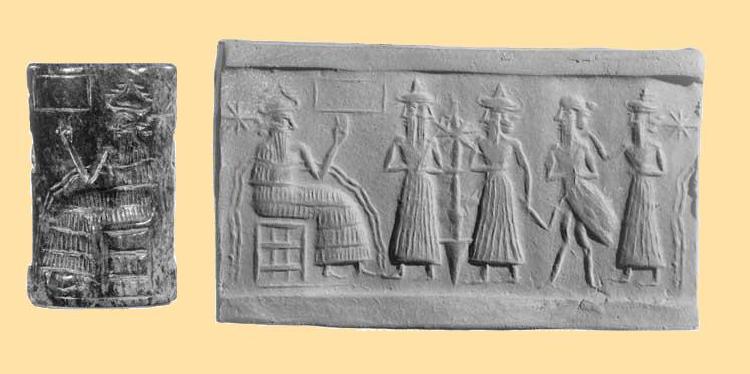

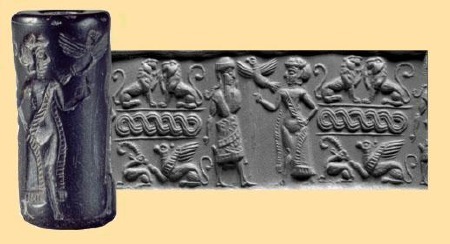

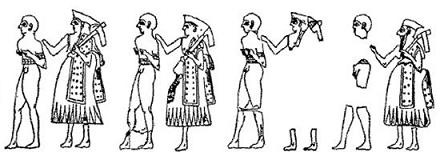

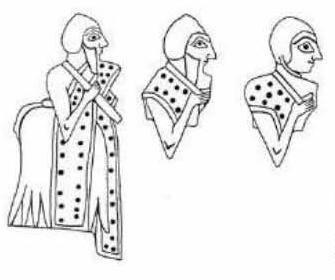

Scribe or priest, alabaster

Scribe or priest, alabaster Priest, Ishtar Temple. Musee du Louvre

Priest, Ishtar Temple. Musee du Louvre

Figure 6: Daśāpavitra

Figure 6: Daśāpavitra

[]quote]

[]quote]

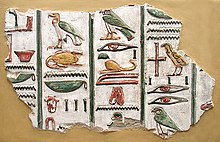

![O34 [z] z](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_O34.png?63e15)

![G1 [A] A](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_G1.png?4d556)

![D46 [d] d](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_D46.png?1dee4)

![G43 [w] w](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_G43.png?6eb40)

![Aa1 [x] x](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_Aa1.png?3a810)

![Q3 [p] p](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_Q3.png?42130)

![L1 [xpr] xpr](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_L1.png?8b41f)

![D21 [r] r](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_D21.png?9bfb9)

![M17 [i] i](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_M17.png?2e70b)

![F35 [nfr] nfr](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_F35.png?9f378)

Late Harappan Period large burial urn with ledged rim for holding a bowl-shaped lid. The painted panel around the shoulder of the vessel depicts flying peacocks with sun or star motifs and wavy lines that may represent water. Cemetery H period, after 1900 BCE. These new pottery styles seem to have been introduced at the very end of the Harappan Period. The transitional phase (Period 4) at Harappa has begun to yield richly diverse material remains suggesting a period of considerable dynamism as socio-cultural traditions became realigned.

Late Harappan Period large burial urn with ledged rim for holding a bowl-shaped lid. The painted panel around the shoulder of the vessel depicts flying peacocks with sun or star motifs and wavy lines that may represent water. Cemetery H period, after 1900 BCE. These new pottery styles seem to have been introduced at the very end of the Harappan Period. The transitional phase (Period 4) at Harappa has begun to yield richly diverse material remains suggesting a period of considerable dynamism as socio-cultural traditions became realigned.

Bronze Peacock in Hadrian museum, Vatican. See:

Bronze Peacock in Hadrian museum, Vatican. See:

Raja Ravi Varma's painting shows Devi Sarasvati with four hands and a peacock vāhana. mayūˊra m. ʻ peacock ʼ VS., in cmpds. RV., mayūrīˊ -- f. ʻ peahen ʼ RV. 2. *mōra -- . 3. *majjūra -- (< *mayyūra<-> with early eastern change -- yy -- > -- jj -- ?). [mayūka -- , marūka --

Raja Ravi Varma's painting shows Devi Sarasvati with four hands and a peacock vāhana. mayūˊra m. ʻ peacock ʼ VS., in cmpds. RV., mayūrīˊ -- f. ʻ peahen ʼ RV. 2. *mōra -- . 3. *majjūra -- (< *mayyūra<-> with early eastern change -- yy -- > -- jj -- ?). [mayūka -- , marūka --