Vijayanagara was one of the most dazzling of the capitals of mediaeval India. The ruins of the city have awed travellers and scholars alike. But a historian, a woman who lives in Paris, says an empire by the name Vijayanagara never existed. She has created an uproar but insists the correct name is Karnataka empire.

Vasundhara Filliozat has been working on the history of Karnataka since the early 1960s. She was born in Haveri in Dharwad district as the fifth child of Sanskrit and Kannada scholar Pandit Chennabasavappa Kavali. She studied history, Indian epigraphy and French at Karnataka University, Dharwad before she got a scholarship to study theatre in France. After two years of studying theatre, she returned to history and did her PhD from Sorbonne University in Paris. There, she studied the first two kings of Vijayanagara under Prof. Jean Filliozat, the celebrated Indologist of that era.

Her approach to history is simple: Read what is written at the site. She studies inscriptions and icons to dig out stories from the past. While studying Hampi, she translated more than 150 Kannada inscriptions into French.

She has worked on several temple sites in Karnataka including Hampi, Badami, Pattadakal and Muktesvara (at Caudadanapura) and Kalamukha temples. Her books on the temples in Karnataka are co-authored with her husband Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat, son of her mentor. While Vasundhara writes on history, epigraphy and iconography, chapters on architecture are authored by Pierre-Sylvain. Her books include: Vijayanagar, Alidulida Hampe, Hampi-Vijayanagar: The Temple of Vithala. She is currently working on two books—a book on Vijayanagara for the National Book Trust and another on legends of Hampi for the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts.

Now, she divides her time between Paris and Mysuru. At her house in Mysuru, sitting amid paintings by her husband, she talks to us about the “Hinduness” of the kings who unified the south to fight Islamic invasion, the role of the temple in everyday life, the current phenomenon of politics over history, and more.

Edited excerpts from an interview.

What was your childhood in Dharwad in 1940s like?

Though I come from a poor family, my background was very rich. We belong to the Nekara (weaver) community. My father, Pandit Chennabasavappa Kavali studied old Kannada and Sanskrit in the 1920s. Father would bring up various topics during regular conversations and stories or his own experiences. He would discuss novels and dramas with us.

During my BA final examinations, AIR was airing a Mallikarjun Mansur concert on a Saturday. I had my paper on Monday. He said:‘Oh! The examination can come next year as well but not Mansur’s programme.’ My mother didn’t object to it either whereas neighbours did. This is the kind of upbringing I had.

I did my high school in Dharwad and my higher studies at Karnataka University. I was a Gandhi class student. The distinction students stop at getting a good job. But for mediocrities like me, our brains continue to work since it has not exhausted itself in those initial years (laughs). Being mediocre is what pushed me to do better later in life.

How did you get interested in studying history?

I considered history and philosophy. But, history is like a story. I found it more interesting than philosophy, which is more abstract.

In Paris, I met Prof Jean Filliozat. He was just back after visiting temples of Aihole (Hindu, Jain and Buddhist monuments built between the 4th century and the 12th century in Badami Chalukya, Rashtrakuta and Kalyani Chalukya periods) and Pattadakal (Badami Chalukya era, 7th and 8th century) and happy to have a student from Karnataka. He asked me questions about Karnataka: have you seen these sites; do you speak Kanara or Canari? I said boldly, no, sir, I speak Kannada. He corrected himself calling it Kannada. At that time, I had no idea how great a scholar he was and what a great institution Collège de France was. Under his guidance, I started my PhD on the first two kings of Vijayanagara.

How did you discover your love for Vijayanagara?

That was my first love! It started as early as in 1962-63 when I was an MA student and taken on a study tour to Hampi. When I saw Hampi, I said to myself that I must take photos of every inch and every nook and corner of this place and I must study this site. That was the day! At that time, Hampi was so beautiful. All the ruins were there—all the broken structures and pillars, and mutilated images. And there was not so much of vegetation on the monuments. We spent three days there and I immediately decided to study Hampi for my PhD.

What initiated you into epigraphy?

I was working on the beginning of the dynasties—whether they were Kannadigas or Telugus, whether Desapattana was Vijayanagara, etc. I was studying a lot of published material. My guide Dr Filliozat—by then I had become his daughter-in-law—said: ‘Stop this nonsense! Go to the inscriptions; translate them and write about that. That is going to be your original contribution to the history of Vijayanagara.’ I wasn’t happy.

Today, I am thankful to him. This is the path I have taken not just for that PhD work, but in all my works, be it Hampi, Pattadakal or Kalamukha temples (Lakulashaiva temples in North Karnataka built in 11th-13th century, Kalyani Chalukya period). I go only through the inscriptions and give my own impressions about them. And that’s what makes my work original.

Which language were these inscriptions in?

The art of writing inscriptions starts from Ashoka in the 3rd century BC and his inscriptions are many in that area— Muski, Sanganakallu, Koppal in Bellary district. They are in Brahmi script and the language is Prakrit; it is neither Sanskrit nor Kannada. It’s like that all over India. Later, each region developed its own script, taking Brahmi as the base. Karnataka wasn’t an exception; they developed Kannada from Brahmi. We have Hale (old) Kannada, Nadu (medieval) Kannada, and Hosa (new) Kannada.

However, in the inscriptions of this so-called Vijayanagara period, there is no Prakrit. Most are in Kannada except the first few words in Sanskrit. So the Hampi inscriptions were not very difficult for me to translate.

Badami Chalukya and Hoysala inscriptions are in Hale Kannada. To read and understand these, you should have a good knowledge of Kannada literature, Sanskrit literature and Prakrit, which most people don’t have. I can’t read Prakrit. I can understand Kannada and manage Sanskrit.

However, in the inscriptions of this so-called Vijayanagara period, there is no Prakrit. Most are in Kannada except the first few words in Sanskrit. So the Hampi inscriptions were not very difficult for me to translate.

How important is it for a historian to understand the local language and culture?

When the Europeans came to India, they said Indians didn’t have a historical sense. This is stupid. They did not know that in each and every temple, at every historical place, there are inscriptions and they are our authentic documents which tell our history. In most of the inscriptions, the first portion is eulogy of the king or the donor or the patron. Next, they mention the date— on such and such a date, the temple was built or such a donation was made. They go on to detail which rituals were performed in the temple, who were employed for which service and how much salary they were getting. If you study an inscription, every word tells you a good history.

The British did a very nasty thing. They thought Indians were fond of legends and mythology so they put legendary history in history textbooks.

Europeans have done some epigraphy work but most of it is superficial. A professor from Paris collected several inscriptions of Vithala (built in 1406, Sangama era) and Virupaksha temples (Badami Chalukya era, 7th century). The copies were in Kannada but some European historians called them Telugu inscriptions. Many inscriptions have been translated wrongly by Europeans. They read it correctly but interpreted it wrongly because they did not have a good knowledge of the language or culture. They took some assistance from good pandits but couldn’t find reference material. Not many books were published as now and material was not as abundantly available as today. Some translated inscriptions just give a resume of the inscription, not the details. For instance, they mention that the inscription has details of a grant but don’t translate the details of the grant. In fact, details of the grants are very important to understand life in that period.

A lot of your works have been published in French. While in Paris, you also hold public lectures. Who are your audiences?

Many, many people are interested in Vijayanagara the capital, the history of the empire, and history of Karnataka. Not much has been published. In France, I think, I am the only one working on Karnataka.

In Europe there is an epidemic; they all go to Tamil Nadu (laughs). When the British became rulers of India, Madras was one of the important places so many people went there. Then, Pondicherry became independent and the French Institute of Pondicherry was established in 1955. It was established by my father-in-law and unfortunately that is also in Tamil Nadu (laughs). Also scholars are well received by institutions like Madras University. In Karnataka, there is no infrastructure for receiving these scholars and help them with material. There was one American who wanted to study the Lakulisha Pashupata shaivism in Karnataka. He abandoned it for lack of support.

Making works available in various languages encourages future works.

Vasundhara Filliozat with her husband Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat. This and title photo: Sriram Vittalamurthy.

What discoveries from Hampi inscriptions surprise or interest you the most?

The most interesting bit for me was that the kings were Kannadigas. I can’t say if Telugu was their mother tongue but the official language was Kannada. They called it deshabhasha, roughly translated as national language. All inscriptions are in Kannada. Even the inscriptions in Tamil Nadu and Andhra start in Tamil or Telugu but switch to Kannada in the details of the grant.

The most interesting bit for me was that the kings were Kannadigas. I can’t say if Telugu was their mother tongue but the official language was Kannada. They called it deshabhasha, roughly translated as national language. All inscriptions are in Kannada.

There are many Sanskrit copper plates—grants were given on copper plates— where the first portion of the text is in Sanskrit and when they come to the date and the details of the grant, they say ‘deshabhashya kathyate’ (to be said in deshabhasha). And this is followed by text in Kannada. So, Kannada is the deshabhasha.

Did reading inscriptions help you find original material on Vijayanagara?

Yes. Most importantly, the foundational legend turned out to be untrue. The legend is—Harihara goes hunting and sees hounds being chased by a hare. Vidyaranya, a saint of Sringeri matha, considers it a blessed and protected place and advises him to build a city on that spot. Harihara builds an empire, with his capital on the hare-hounds spot. Goddess Bhuvaneshwari showers gold upon Vidyaranya.

The empire was founded in 1336. The inscriptions reveal that Vidyaranya didn’t exist at that time. A renowned scholar in 1336 was Vidyatirtha, the guru of Vidyaranya. This was also the time of Ballala III, the last great Hoysala ruler (1292-1342), the only surviving Hindu king in the south and fighting to eliminate Muslim rule in the south. Can you imagine saints like Vidyaranya or Vidyatirtha saying ‘let Ballala fight but instead of supporting him, let us build a new empire’? This is really stupid.

Also, Bhuvaneshwari wasn’t worshipped in Hampi. In fact, until the 18th century, there is no mention of Bhuvaneshwari but now she has become the goddess of Karnataka, the Mysore Dasara festival, etc. and people proudly shout Jai Bhuvaneshwari! Jai Karnataka Mate!

The legend was concocted in the 17th-18th century but people have taken it as historical fact. And our people are happy to repeat it.

For all your love for Vijayanagara, you state that an empire called Vijayanagara never existed.

What they refer to as Vijayanagara empire was actually called Karnataka Samrajya (empire). Vijayanagara was only the capital.

Robert Sewell (1845-1925, Keeper of the Madras Record Office) was the first to study Hampi and write a book on it, A Forgotten Empire Vijayanagar. Though he mentioned in the body of the text that the empire was called Karnataka, he chose Vijayanagar in the title because he knew Kannada and Telugu groups would fight if he called it Karnataka.

Most Indian historians, like B. A. Saletore, P. B. Desai and Ram Sharma, also knew it was called Karnataka. Still, Saletore titled his thesis ‘Social and political life in the Vijayanagara empire’. Desai titled his novel Vijayanagara Samrajya Sthapane. Suryanarain Rao titled his book Vijayanagar, The Never To Be Forgotten Empire.

In 1936, they celebrated the 6th centenary of the foundation of the empire. There were great scholars like Saletore, P. B. Desai and Aluru Venkata Rao but they did not have the courage to say it was Karnataka Empire.

The Indian Council for Historical Research requested Dr Shrinivas Ritti, who also called the empire Vijayanagara in his works, to bring out a compilation of all published inscriptions. In the introduction to the second volume, he says the empire was never called Vijayanagara; it was called Karnataka and that Mrs Filliozat was the first to point out, and that Sewell knew about it. He said historians chose the name Vijayanagara since it was better known but forthcoming scholars should think of using the correct nomenclature.

Could you independently verify the name of the empire?

Yes, I’m basing this on epigraphical evidence. It shouldn’t be called by a certain name because I’m saying so or because Sewell said so. In all official mentions, it was Karnataka. Dr Ritti has also quoted more than 30 inscriptions that show it was Karnataka empire, right from the beginning.

Karnataka or Kannada Nadu embraced some parts of Andhra and Maharashtra. In Amoghavarsha Nrupathunga’s time (ruler of the Rasthrakuta dynasty, 800-878 CE), the region between the Godavari river in the north and Kaveri river in the south was Kannada country. Pampa and Janna, two of the greatest Kannada poets come from today’s Andhra.

Kings didn’t call themselves Badami Chalukya or Kalyani Chalukya but rulers of Karnataka. The Maharaja of Mysore, in his inscriptions, used to say he was king of Karnataka. Even later, Thanjavur, Vellore, and Madurai were ruled by Nayaks who were vassals of Karnataka kings and called themselves Nayaks of Karnataka. The British called the two styles of music in India Hindustani and Carnatic because the northern Mughal Empire was Hindustan and the southern Karnataka. The wars between the British and the Nawab of Arcot were called Carnatic wars.

Today, when I say the empire should be referred to as Karnataka, the response is ‘no madam, if we say Karnataka, we’ll be limiting ourselves to Karnataka state’. They exhibit their idiocies because there is a difference between the empire and the state that exists today. It makes me feel very sorry.

How willing are historians to take a fresh look at ideas that are widely accepted?

It’s very difficult to change these ideas. A lot of history in India has been reduced to supporting or refuting what’s already been said. That’s what modern students do; whatever the former scholars have said, I should speak for or against it. And if he is a foreigner who has said something, they repeat it and they take it as gospel truth. I am not sure if it is a lack of original study or plain jealousy.

How important is it to call the empire Karnataka and not Vijayanagara? Do you expect it to provide a new context in the study of history?

It definitely will. If you are a good historian, you should say what is in the text and not conform to general perceptions. When you study the Hoysala empire, do you call it Dwarasamudra empire or Belur empire? Do you call the Chalukyas the Badami empire? You don’t do that. Why should you call Karnataka empire by a different name? You should call a thing by its original, correct name.

In this particular case, the correct name solves several problems. When you say Karanataka empire, the big question about the date of and story behind the foundation of the empire vanishes. The untrue legends of Vidyaranya and Bhuvaneshwari showering gold vanish too.

So, when and how did the Karnataka Empire come into existence?

In 1346. There was no foundation as such. It was decided that to face the northern invaders, there must be only one kingdom and one king for the whole of the south. The Hoysala ruler Ballala III started bringing the entire south together and it was fully realised in the time of Harihara I.

Probably it was Vidyatirtha’s (the guru of Vidyaranya) idea. Since Ballala III was the last surviving Hindu king, he started this. It was decided that the Hoysala Empire would continue but the king didn’t call it Hoysala to spare the feelings of other rulers who came together. Since Ballala III was from Karnataka he called the new empire Karnataka.

According to me, it starts in 1336-37 when Ballala III goes on a tour to supervise the northern frontiers— Badami, Koppal, Gadag, etc.— of his kingdom. He realises a stronghold in this area can stop invasions from the north. Hampi answers his problems because of its geographical situation—it is on the banks of the Tungabhadra, not far from his northern frontiers, and surrounded by rocky mountains that serve the purpose of fort walls. Hampi was in the hands of Kampila, a minor chieftain whose capital was at Kammatadurga, not far from Hampi. Ballala III got him killed and took control of Hampi.

Ballala III was treacherously killed by the Madurai Sultan in 1342, after he was invited to go unarmed to sign a treaty. Ballala IV comes to the throne in 1342 but there are no inscriptions about him after that. He was in his 60s and must have died.

From 1346 onwards, we don’t get any Hoysala inscriptions but we do get inscriptions of Sangamas, Harihara I and Bukka I. To publicise his victory, the king makes a grant to the Sringeri Sharada Peetham in 1346. That marks the beginning. So there was no foundation as such. The study of inscriptions gives you this picture.

How was the south unified?

It was done over a long period. Madurai, the Yadavas of Devagiri were originally Hindu kingdoms but occupied by Muslims at that point. Most temples in these areas were closed and no rituals were performed. When Malik Kafur invaded (generalissimo of the Delhi Sultan Alauddin Khilji, he invaded the Yadava, Kakatiya, Hoysala and Pandya kingdoms between1308 and 1311), the whole of the south was a patchwork ruled by the Hoysalas, the Yadavas of Devagiri, the Kakatiyas of Warangal, the Cholas and Pandyas. They were fighting among themselves for further aggrandisement of territory. The Hoysalas had a lot of vassals holding small areas.

So Vidyatirtha must have advised that the south must be united. He sent his students, Madhavacharya and Sayanacharya, to campaign in this direction. It was executed so well that by the time of Harihara I, all the Hoysala vassals had come to their support. When Bukka I came to the throne, he sent his son Kampana II to various places to study them and establish peace and order. Kampana went to Madurai and succeeded in re-establishing the rituals in all the temples and order in the south.

So, at that time whole of south India was united under one banner and it was called Karnataka.

Is this the only time in history when the whole of south India is united as one kingdom?

Yes, yes! The entire area south of the Krishna was under the Karnataka Empire while the two oceans formed the boundaries in the east and the west. It existed for more than 200 years—from 1346 to 1565. It fell only in 1565 after the battle of Talikota (where its army was defeated by the Deccan Sultanates).

Was Vijayanagara a significant place for other empires?

It was known beyond the seas, both the eastern and the western. Many western chroniclers, including Portuguese and Italian travellers, have written about Vijayanagara, visited it. Many horse merchants visited it; they had a trade with Portugal. Before the Portuguese, they had contacts with Arabs. And on the eastern side, it had contacts— both trade and diplomatic—with China. An inscription mentions that Bukka sent his ambassador to the Ming ruler in China. It is recorded in the Ming annals. But Vijayanagara’s contacts on the eastern side have been neglected in studies.

Do you find inscriptions at Vijayanagara site on the empire’s relations with other kingdoms?

Unfortunately, there are none. We have to study foreign documents. The Chinese mention they had their traders in the western oceans. It is published in a journal called T’oung Pao. I feel I should study it in detail. There is Hikayat Hang Tuah from Malaysia, which mentions links with the kings of Karnataka and the writer gives a description of the capital Vijayanagara— there were heads of terrifying lions on the top of every gate so that miscreants who wanted to enter the capital would get scared.

Did the travellers call the empire Karnataka?

No, it was hard for them to pronounce Karnataka. The chroniclers and the horse merchants called the capital Bisnaga and the kingdom Narasanga, by the name of the king Saluva Narasimha, who was on the throne when they came. Abd-ur Razzaq (a Persian scholar) doesn’t speak about the empire but gives a beautiful description of the capital in the mid-15th century. He calls it Biznagalia;it was very difficult for them to say Vijayanagar. Diogo do Couto came in the 16th century after the downfall of the empire. He was an archivist and had documents. It is he who writes that we call the empire Narasanga and the capital Bisnaga but local people call it Biznagalia; it was difficult for him to pronounce Vijayanagara. He called the empire Canarine; he couldn’t pronounce Karnataka.

Does studying the Karnataka empire and Vijayanagara capital offer significant insights into Indian history?

It is after the downfall of Vijayanagara that the Keladis and the Maharaja of Mysore and other chieftains came. That is the continuation of the culture. The rulers of Mysore used to say they were Karnataka Simhasanadhishawara (lord of the throne of Karnataka). It was the British who compelled them to call themselves Mysore Samsthanikaru (Ruler of Mysore). It’s in their documents.

The greatest contribution of Karnataka kings to Indian architecture is the musical pillars of the Vithala temple. You have musical pillars in Madurai, Shuchindram and some other temples. To understand what it is, where it came from, you must go to Hampi. Musicians suggest that the quality of musicality in Hampi pillars is missing in other temples.

Do inscriptions talk about musical pillars at Hampi?

Unfortunately, no. These pillars were built in 1554 and the downfall of the empire occurred in 1565. The empire hardly survived 10-11 years after the pillars so we do not have any reference to this.

How was the musicality of pillars found out?

It was believed that those pillars were musical. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) gave pieces of wood to monument attendants to beat the pillars with wood and show the tourists the pillars were musical. But it didn’t work well. In 1975, Vasant Kavali, my elder brother, discovered the way. He was a producer in AIR, Bangalore and a musician. He tried various ways and figured that you get musical notes only on tapping with fingers.

The capital was Vijayanagara. So, what was Hampi?

Hampi is the nucleus of Vijayanagara. Initially, it was called Virupaksha tirtha. After the marriage of Pampa and Virupaksha, she demanded that the place be called after her name. So, it became Pampa tirtha. And Pampa became Hampi in Kannada.

Which is your favourite Hampi legend? And, how do you know it is not a true story?

My favourite is the Radha legend. It talks about why all Vithala idols are naked. It is the most beautiful story, a very funny story.

Shachi, the wife of Indra, goes to see Vishnu and praises him. A happy Vishnu grants her a wish and she asks him to seat her on his lap. Vishnu declines but promises he will do it when he is born as Krishna and Shachi as Radha. So, when Radha meets Krishna, now the king of Dwaraka, he makes Radha sit on his lap, which infuriates his wife Rukmini. She leaves him and goes to the jungle. Krishna goes to get her back home.

He tells her in Marathi: ‘Aga vedhe chal (Hey, you mad girl, come on)’. This gets her angrier. Krishna stands in front of her and undresses. The poet doesn’t explain why. It is believed that all the Vithala temples since then have idols of a naked Krishna.

This story became popular in Karnataka but we do not have literary evidence for this. But in Marathi it is written. G. H. Khare has written a book on Pandharpur Vitthal. He says we do not know why he removed all his clothes but he stands naked in front of her and since then the Vithala temples are built with idols of naked Krishna.

In Hampi, there is no Vithala idol now. But we discovered a temple near Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu where the image is naked. Khare speaks about the image of Vitthal in Pandharpur; it is not the original image, which was replaced by the current one. He says he has examined it closely and the image is dressed but Krishna’s private parts are visible.

The cult of Vithala starts in Karnataka from the 7th or 8th century, before the Hoysalas. At that time the images of Vithala were fully clad. In the time of Krishnadevaraya, somebody concocted this legend about Vithala being naked.

Also, the Radha cult was not popular in Karnataka. Nobody accepted Radha as a goddess or the beloved of Krishna. She is not present even in Tamil Nadu. This story came up later and became popular in Maharashtra. In fact, it was concocted after the downfall of the kingdom since there is no mention of Radha in any of these inscriptions. There is no Radha mentioned in the compositions of Purandar Dasa, Kanaka Dasa, Vijayadasa or other saints. She is worshipped in the whole of north India (north of Krishna river); there are Meera bhajans about Radha and stories of her in Gita Govinda; but not in Karnataka.

Another favourite is the story that the Vithala temple was never completed and there never was an idol. You know this is not true if you study the inscriptions. Many donations were made to the temple. The dholotsava mantapa was built and the festival celebrated in the centre of the mantapa. If the temple had not been completed or the idol not installed, why did they celebrate so many days of festival and describe it in great detail in the inscriptions?

As late as in 1563, Nammalavaralu, a devotee of Vithala and a Telugu man with a Tamil name, makes donations to the temple, specifying that the prasada of the morning rituals should be brought to his house with a procession of musicians and dancers. That kind of pomp implies the temple was open.

So do we know why doesn’t the Vithala temple in Hampi have an idol today?

The Muslims who attacked the empire were not against temples or Hindus. But they wanted to efface the memory of Rama Raya, the defeated king, from history. They thought if they demolished the temples so dear to Rama Raya, he would be forgotten. So, first, they attacked the Vithala temple and wanted to raze it to the ground but it is built so solidly that they could not succeed. So they covered it with wooden logs and set fire to the sanctum. It burnt. That is why only the central part is open to the sky.

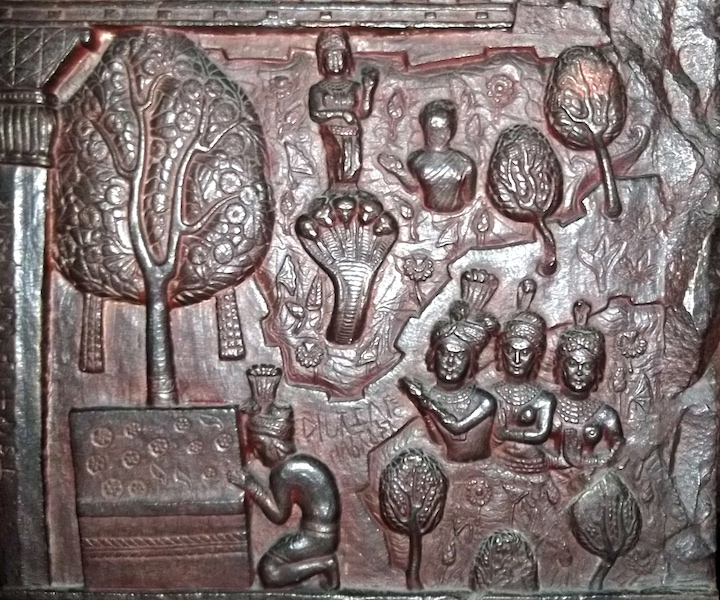

The temples in Hampi exhibit Aihole-Pattadakal style as well as influences of Indo-Islamic architecture. Didn’t this era witness a Hindu-Muslim divide as some historians have suggested?

Yes, there are monuments that have Indo-Islamic architecture because Islam was already there. There were many Muslims living in the capital. If you go towards Kadirampura, you will find Muslim tombs. And next to them, you will find an inscription of a temple. Towards the north from the core of the capital towards the Vithala temple in the ruins, you can’t see it from the road but if you have the courage to walk inside like we did in those days, you will find Muslim tombs with inscriptions and Hindu temples, next to each other.

Domingo Paes, a Portuguese horse merchant, who came in the time of Krishnadevaraya, says Hindus and Muslims had their houses next to each other. He says that to the north of the capital there are Muslim quarters where Hindus also live.

A Muslim bodyguard of Deva Raya II, Katige (one who holds a stick) Ahmad Khan, built a chhatra (umbrella) in Hampi for the good of the king. After Khan’s death, the king built his tomb next to that chhatra. The tomb and the chhatra with an inscription on the door still exist.

Hindus and Muslims lived in harmony there. These British historians have made a mess, concocting stories of Hindu-Muslim divide and our people want to repeat it.

How important were temples in this empire? Were they just for worship or did they serve a larger purpose?

Temples were, first of all, banks. People would deposit an amount in the temple and on the interest rituals were celebrated. Some revenues from villages were given to the temple. Right from the beginning, they became cultural as well as educational and financial centres.

In Hampi, there are several inscriptions detailing donations to temples, specifying which rituals they were meant for and how much was to be spent for which purpose. Donations were made for renovation and construction as well.

The temple was a religious centre but it served many other purposes. All the life in that area developed around the temple so it was the pivot of the agglomeration.

You have studied the Hampi, Pattadakal and Kalamukha temples. Do you study only temple sites?

The temple is an open book—you get mythology, history, social, cultural and religious lives. A student gets abundant material here. This is what makes me interested in studying them.

But I study the entire place, not just the temple site. Whichever site I choose, I want to study the history of that place. While studying Vijayanagara, I wanted to understand the whole empire.

Why have some historians complained that Basaveswara hampered temple building in Karnataka?

In Badami Chalukya and Kalyani Chalukya period (6th to 8th centuries and 10th to 12th centuries, respectively), Lakulashaivas(followers of Lakulisha, the founder of the Pashupata Shaivite school) in Karnataka advised people to build temples and make donations to them. People who made donations were not required to pay taxes to the king, making him weak. When Bijjala comes to power, he employs Basaveswara to find a via media. Basaveswara teaches that your body is god; if you perform your duty, god will be happy and you get moksha; going to temples isn’t necessary.

Some historians accuse Basaveswara of impeding temple-building. Yes, building a temple anywhere and everywhere stopped, but existing temples got enlarged. Because of his movement, Karnataka has some large and beautiful temples, instead of several small and insignificant ones.

There is a huge discussion about lingayatism being a separate religion but Basaveswara never said it was a religion. He said ‘do your duty and don’t think of anything else’. He talked about it as a way of life. In his days, lingayatism did not get recognition. It became prominent only in the 15th century.

There are demands to recognise Lingayatism as a separate religion. Can we find early references if we look through the inscriptions?

You will be wasting your time. There is a huge discussion about lingayatism being a separate religion but Basaveswara never said it was a religion. He said ‘do your duty and don’t think of anything else’. He talked about it as a way of life. In his days, lingayatism did not get recognition. It became prominent only in the 15th century.

In Basaveswara’s time, Lakulashaivas were prominent in Karnataka. They were treated as equal to Brahmins and held important posts as royal preceptors and advisors to ministers. They did not accept Basaveswara’s ideas. That led to revolution in the capital Kalyani. King Bijjala was assassinated and Basaveswara had to leave the place. His period was over by 1168 and the Chalukya empire ends in 1189. Seunas of Devagiri continued to rule and we have a number of Lakulashaiva inscriptions that suggest they were heads of the temples and continued to perform pooja, unlike what Basaveswara taught. He was not forgotten but we get his references only in some inscriptions, including one at Chaudadanapur near Ranebennur, where a saint says ‘I want to be like Sangana Basava’.

Basaveswara’s principles and lingayatism came to prominence only in the time of Deva Raya II, when all the vachanas were codified. This is in the first half of the 15th century.

The Karnataka Empire was founded to protect Hindu kingdoms from Muslim invasion. So, how Hindu was this empire?

The kings were not against Muslims. They were against Muslim rule over Hindu kingdoms. I must make this point very clear. There was no hatred. In fact, they just wanted to protect their kingdom from invaders, who happened to be Muslim. They saw it as alien invasion. In fact, they used a title Suratrana, derived from the title Sultan that Muslim rulers used. They called themselves Hindu Raya Suratrana meaning Hindu Sultan.

Did they not want to build a fierce Hindu identity or promote Hindu nationalism?

No. They were just stopping alien invasion. Temples were built and rituals conducted but there wasn’t a state religion. When the Bhakti movement started, Purandara Dasa, Kanakadasa and other saints sang the praises of their gods. In a way, itwas maintaining Hinduism but the kings never asked people to do anything about religion. They accepted all religions. Buddhism had disappeared from this area by then; Jainism was there; and Madhava, Sri Vaishnava and Shaivism were there. Lingayatism started after the 15th century. The kings accommodated all of them. Some Jesuits in their documents have said the king—I think it was about a king of the Aravidu dynasty—was ready to become Christian. They must have exaggerated but it shows how accommodating the king was.

You mentioned in one of your lectures that Karnataka is celebrating Hampi Utsav (festival) without giving Tipu Sultan due credit. What’s Tipu’s Hampi connection?

When the British were organising the states, the Hyderabad Nizam had an eye on Hampi since Anegundi was already in his dominion. At the same time, the Marathas, who had Bombay-Karnataka (Dharwad, Bijapur, etc.) thought Hampi should come under their territory. But Tipu said Hampi was the capital of the Karnataka Empire and must remain in Karnataka. He fought for it. Also, he had a soft corner for the last descendant of the maharaja of Anegundi, who called himself the descendant of Aravidu Rama Raya, surviving on a meagre revenue and some help from Tipu who thought if Hampi stayed in Karnataka, he would have better means of survival.

In any case, it is because of Tipu that Hampi is in Karnataka today. If Karnataka is celebrating Hampi Utsav, they must give Tipu his due.They must remember him for what he did.

There has been a lot of political drama around celebrating Tipu’s birth anniversary with some political groups calling him anti-Hindu. Do you think he was anti-Hindu?

These are all stupid people. The BJP is backed by the VHP, who are fanatics. They don’t acknowledge Tipu’s contribution but this is a fact and written by the British in a published paper.

You celebrate Krishnadevaraya and all other rulers. Why not Tipu? He is part of our history. Whether you like Tipu or not is not the question. By celebrating his jayanti, you are remembering a historical figure and you’re reminding the people of our history. Doing this is not anti-Hindu. In fact, he was not anti-Hindu. He is being portrayed as one but he wasn’t. In fact, Tipu used to say he was a devotee of Ranganatha of Srirangapatna. He gave lots of donations to temples in Srirangapatna, Melkote, etc.

It was the British who started anti-Tipu propaganda to turn people against him. In the beginning, Tipu was a kind and gentle ruler. When the British attacked him continuously and he had a lot of difficulties, probably he became cruel. But, I don’t believe it when they say he massacred hundreds of Iyengars because he wanted to kill Hindus. His acts were more of suppression to save his state than anti-Hindu.

You seem to take your role as a historian as somebody who separates myth from facts very seriously.

That should be the primary objective.

Our current political dispensation is blurring the line between myth and history. There are attempts at rewriting history from one point of view and to erase parts that are not to one’s liking. How do you see that as a historian?

It makes me very sad. We have an expression in Kannada ‘Boregall mele neer suridhanthe’. On a rock, you pour water, it doesn’t sprout. Talking to politicians about these things is like that.

I’m not saying that myth is worthless and you should discard it. Some legends are based on certain facts. But, you need to verify. It is important to separate historical facts and myth.

In the original Ramayana, Hanuman is not a monkey but a great scholar and musician. The legend about him being a monkey appears much later. Recently, I attended a seminar where a professor from Hyderabad spoke about Aurangzeb’s atrocities as well as his good qualities. When he spoke about the good qualities, nobody wanted to accept it.

Our people are happy repeating legends.

![]()

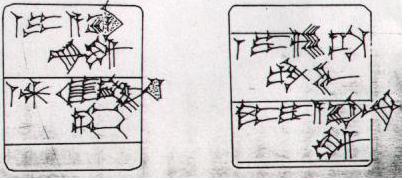

![]() It is remarkable that this hieroglyph constitutes the signature tune of one of the longest inscriptions of Indus Script.

It is remarkable that this hieroglyph constitutes the signature tune of one of the longest inscriptions of Indus Script.![]() Longest inscription m0314 of Indus Script Corpora is catalogue of a guild-master. The guild master is signified by Indus Script hypertext 'squirrel' hieroglyph 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Rebus: plaintext: khār 'blacksmith' śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa). The guild-master signs off on the inscription by affixing his hieroglyph: palm squirrel,Sciurus palmarum'

Longest inscription m0314 of Indus Script Corpora is catalogue of a guild-master. The guild master is signified by Indus Script hypertext 'squirrel' hieroglyph 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Rebus: plaintext: khār 'blacksmith' śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa). The guild-master signs off on the inscription by affixing his hieroglyph: palm squirrel,Sciurus palmarum' Longest inscription m0314 of Indus Script Corpora is catalogue of a guild-master. The guild master is signified by Indus Script hypertext 'squirrel' hieroglyph 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Rebus: plaintext: khār 'blacksmith'

Longest inscription m0314 of Indus Script Corpora is catalogue of a guild-master. The guild master is signified by Indus Script hypertext 'squirrel' hieroglyph 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Rebus: plaintext: khār 'blacksmith'

K

K

Cancho Roano

Cancho Roano  Side view showing the depth of the Burney relief.

Side view showing the depth of the Burney relief.  Approximate red ochre colour scheme of the painted relief. Her necklace is composed of squares (like coins of Nishka). She wears bracelets with three rings. She has flight feathers. Lines on ankles and toes depict scules, with talons on visible toes. She stands atop two lions and flanked by two owls. The sculptural frieze is a hieroglyp-multiplex.

Approximate red ochre colour scheme of the painted relief. Her necklace is composed of squares (like coins of Nishka). She wears bracelets with three rings. She has flight feathers. Lines on ankles and toes depict scules, with talons on visible toes. She stands atop two lions and flanked by two owls. The sculptural frieze is a hieroglyp-multiplex.

Bet Dwaraka seal.

Bet Dwaraka seal.

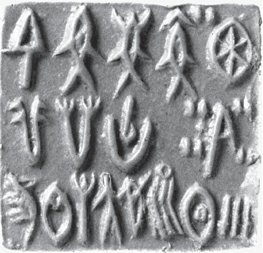

9351; Nippur; ca. 13th cent. BC; white stone; zebu bull and two pictograms. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'. goTa 'round object' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'; bartI 'partridge/quail' (Khotanese); bharati id. (Samskritam) Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, the message is: kuThi poLa khoTa bharata smelter for magnetite, alloy ingot (copper, pewter, tin alloy).

9351; Nippur; ca. 13th cent. BC; white stone; zebu bull and two pictograms. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'. goTa 'round object' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'; bartI 'partridge/quail' (Khotanese); bharati id. (Samskritam) Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, the message is: kuThi poLa khoTa bharata smelter for magnetite, alloy ingot (copper, pewter, tin alloy). 9851; Louvre Museum; Luristan; unglazed, gray steatite; short-horned bull and 4 pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; PLUS meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' thus, the pair of 'bodies' signify: iron cast metal.

9851; Louvre Museum; Luristan; unglazed, gray steatite; short-horned bull and 4 pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; PLUS meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' thus, the pair of 'bodies' signify: iron cast metal.

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription.

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription.  Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron'

Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron' 3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'. 9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'

9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze' 9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'.

9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim)

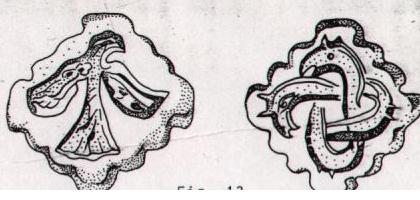

Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim) Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead' 9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'

9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. Image 2 below: Right: A single Seal from Falaika Bears an Inscription in the Unread Indus Script. Left: From one of the Falaika Seals. A Man Holds a Monkey at Arm's Length; Monkeys were Imported as Pets from Meluha. (Bibby, pp. 253, 211).

Image 2 below: Right: A single Seal from Falaika Bears an Inscription in the Unread Indus Script. Left: From one of the Falaika Seals. A Man Holds a Monkey at Arm's Length; Monkeys were Imported as Pets from Meluha. (Bibby, pp. 253, 211).

Bronze horned warrior.Enkomi.

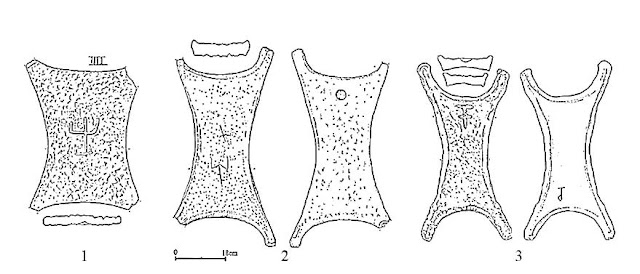

Bronze horned warrior.Enkomi. T symbol on ox-hide ingot (in the middle) from Cape Gelidonya shipwreck. Copper ox-hide ingots (Talents) After Fig. 5 on http://ina.tamu.edu/capegelidonya.htm

T symbol on ox-hide ingot (in the middle) from Cape Gelidonya shipwreck. Copper ox-hide ingots (Talents) After Fig. 5 on http://ina.tamu.edu/capegelidonya.htm T symbol on an ox-hide ingot

T symbol on an ox-hide ingot

Rehman Dehri pendant seal 1A, B.

Rehman Dehri pendant seal 1A, B. Two T symbols shown below the hieroglyphs of markhor and tiger on Warka vase. The T symbol on the vase also shows possibly fire on the altars superimposed by bun-ingots.

Two T symbols shown below the hieroglyphs of markhor and tiger on Warka vase. The T symbol on the vase also shows possibly fire on the altars superimposed by bun-ingots.

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' PLUS Hieroglyph:

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' PLUS Hieroglyph: