-- Writing ink of iron oxide liquid in kernoi rings and gold metallic stylus to inscribe free-hand Indus Script inscription on metal

-- Decipherment of Nindowari seal khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻsquirrelʼ rebus šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ 'guild master'; Kernoi rings karã̄ 'wristlets, bangles' rebus khār 1 खार् 'blacksmith, iron worker'

This is an addendum to:

1. ḍ̠āṛhū̃ 'pomegranate' is an Indus Script Hypertext, signifies, metalwork catalogue rūpaka, 'metaphor' ḍhālako 'a large metal ingot' https://tinyurl.com/ybu636zy

2. Hieroglyphs on Kernoi rings are metalwork catalogues, with Meluhha roots in Sarasvati Civilization sprachbund (speech union) https://tinyurl.com/y8g8443w

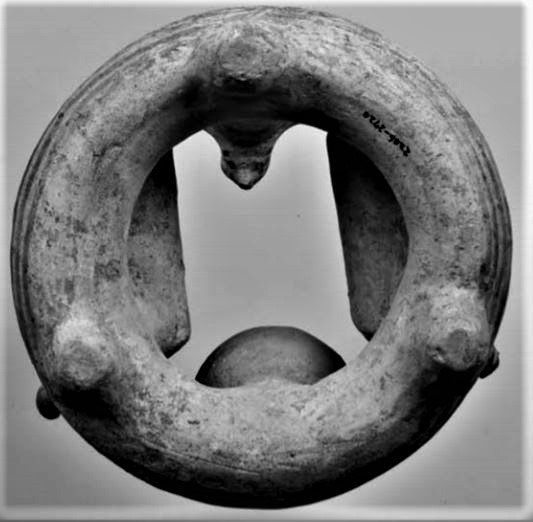

Indus Script writing instruments included kernos, ring of pots as a set of ink-pots containing iron oxide pigment to inscribe inscriptions on metal objects Iron oxide liquid held in such kernos may have been used to write on metal, as demonstrated on the Mohenjo-daro gold pendant. I suggest that the kernos ring of vessels is like an ink-pot containing iron oxide liquid used as a writing ink, to write on metal objects, like copper tablets or gold pendants. The gold-pendants with sharp nibs might have been used as writing instruments.See: https://tinyurl.com/y8xqexl6

The monograph is presented in the following sections:

Section 1: Stylus with nib for free-hand writing using ink (iron-oxide liquid pigment)

Section 2. kernoi rings are Indus Script Hypertexts and are 'ink-stands' to hold iron oxide liquid to write on metal

Section 3. Indus Script hypertexts/artifacts of Nindowari, Kulli, Nal cultures of Balochistan related to metalwork competence

Section 4. Nindowari-damb seal 01,Harappa,Mohenjo-daro inscriptions show

'squirrel 'šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻflying squirrelʼ,'guild master'.

Section 5. Terracotta Ring-shaped Object with Animal Figurines and a Miniature Pot of the Balochistan Tradition in the Okayama Orient Museum by Akinori Uesugi (2013)

Section 6. Kernoi rings identify metal workers and Kernunnos rings are writing

instruments, ink-stands

Section 7. पोळ pōḷa, 'zebu, bos indicus' signifies pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide Fe3O4',Hieroglyph: పోలడు pōlaḍu 'black drongo' rebus: पोलाद [ pōlāda ]

n ( or P) Steel. पोलादी a Of steel.

Section 1: Stylus with nib for free-hand writing using ink (iron-oxide liquid pigment)

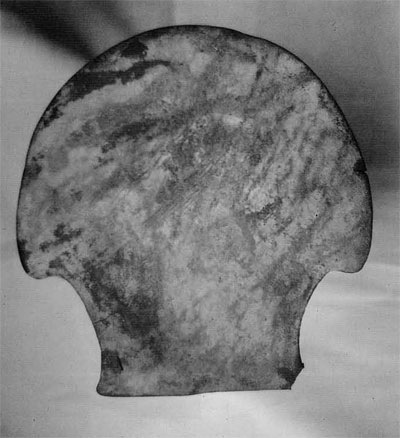

I suggest that the Kernoi rings were 'ink-stands' containing iron oxide liquid for free-hand wrigting to inscribe on metal. A superb example is provided by the Mohenjo-daro gold pectoral with an Indus Script inscription. This gold pectoral is a writing instruiment, a metallic stylus with a nib.

![]() The inscription reads

The inscription reads![]() Meluhha rupaka, 'metaphor' rebus translation: kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'; sal

Meluhha rupaka, 'metaphor' rebus translation: kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'; sal

'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop'; dhatu 'cross road' Rebus: dhatu 'mineral'; gaNDa 'four' Rebus: khanda 'implements'; kolom 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'; Vikalpa: ?ea ‘seven’ (Santali); rebus: ?eh-ku ‘steel’ (Telugu)

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron'(Gujarati) ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

Thus, the inscription is: kancu sal (bronze workshop), dhatu aya kaṇḍ kolami mineral, metal, furnace/fire-altar smithy.

The inscription is a professional calling card -- describing professional competence and ownership of specified items of property -- of the wearer of the pendant.

This is an extraordinary evidence of the Indus writing system written down, with hieroglyphs inscribed using a coloured paint, on an object.

Writing on metal objects has been demonstrated in a gold fillet discovered in Mohenjo-daro with an Indus Script Inscription.

![Image result for inscribed gold pendant bharatkalyan97]() 3 Gold pendants: Jewelry Marshall 1931: 521, pl. CLI, B3

3 Gold pendants: Jewelry Marshall 1931: 521, pl. CLI, B3

Three gold pendants are shown on the bottom right-corner of the image. An enlargement of one of the pendants reveals an Indus Script inscription from Mohenjodaro, written in ink (perhaps, iron oxide pigment).

The comments made by John Marshall on three curious objects at bottom right-hand corner of Pl. CLI, B3: “Personal ornaments…Jewellery and Necklaces…Netting needles (?) Three very curious objects found with the studs and the necklace appear to be netting needles of gold. They are shown just above the ear-studs and also in the lower right-hand corner of Pl. CLI, B, 3-5 and 12-14. The largest of these needles (E 2044a) is 2.5 inches long. The handle is hollow and cylindrical and tapers slightly, being 0.2 inch in diameter at the needle-end. The needle point is 0.5 inch long and has a roughly shaped oval eye at its base. The medium sized needle (E 2044b) is 2.5 inches long and of the same pattern: but the cap that closed the end of the handle is now missing. The point which has an oval eye at its base is 0.3 inch long. The third needle (E 2044c) is only 1.7 inches long with the point 0.3 inch in length. Its handle, which is otherwise similar to those of the other two needles, is badly dented. The exact use of these three objects is open to question, for they could have been used for either sewing or netting. The handles seem to have been drawn, as there is no sign of a soldered line, but the caps at either end were soldered on with an alloy that is very little lighter in colour than the gold itself. The two smaller needles have evidently been held between the teeth on more than one occasion.” (p.521)."

I surmise that all the three gold objects could be pendants tagged to other jewellery such as necklaces. The pendants were perhaps worn with a thread of fibre passing through the eye of the needle-like ending of the pendants.

Why needle-like endings? Maybe, the pendants were used as 'writing' devices 1) either to engrave hieroglyphs into objects; 2)or to use the needle-ending like a metal nib to dip into a colored ink or liquid or zinc-oxide paste or cinnabar-paste. This possibility is suggested by the use of cinnabar in ancient China to paint into lacquer plates or bowls. Cinnabar or powdered mercury sulphide was the primary colorant lof lacquer vessels. "Known in China during the late Neolithic period (ca. 5000–ca. 2000 B.C.), lacquer was an important artistic medium from the sixth century B.C. to the second century A.D. and was often colored with minerals such as carbon (black), orpiment (yellow), and cinnabar (red) and used to paint the surfaces of sculptures and vessels...a red lacquer background is carved with thin lines that are filled with gold, gold powder, or lacquer that has been tinted black, green, or yellow." http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2009/cinnabar

Functions served be kernoi in ancient times have to be re-evaluated. The arguments advanced by many scholars point to 'cult' practices or 'ritual' mysteries. An alternative, practical function can now been posited thanks to the investigation done on the contents of a pomegranate-shaped Motya vase by Labs of Sapienza University.

What could the three objects which are gold pendants, be? Sewing needles? Netting needles? No, metallic writing styluses.

Section 2. kernoi rings are Indus Script Hypertexts and are 'ink-stands'

to hold iron oxide liquid to write on metal

Scores of kernoi rings found in the Sarasvati civilization contact area have now been shown to be 'ink-stands' containing iron exide liquids used as 'ink' to write on metal objects.

I suggest that the kernoi contained iron oxide liquid which was used to write on metal objects.

This monograph posits that the kernoi rings and the Motya vase were ink-pots containing iron oxide pigment to write Indus Script inscriptions on metal objects such as copper plates.

"The (pomegranate-shaped) vase content was sampled twice and analysed in the Labs of Sapienza University. Data collected suggest that inside the vase there was an organic fluid, leaving traces of iron oxide."(Lorenzo Nigro, 2018, Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) from Motya and its deepest oriental roots in: Vicino Oriente XXII (2018), pp. 63-64).

https://www.academia.edu/37111300/POMEGRANATE_PUNICA_GRANATUM_L._FROM_MOTYA_AND_ITS_DEEPEST_ORIENTAL_ROOTS

I suggest that the pomegranate-shaped vase served as an ink-pot containing iron oxide pigment (liquid).

The discovery of iron oxide in liquid form is significant and consistent with the functions of hypertexts on kernoi which are descriptions of wealth accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues in the Indus Script Cipher tradition.

Kernosis a Mycenaean ceramic piece, usually in the form of a ring, to which were attached a number of cups or vases, used in the mystic ceremonies to holdsmall quantities of viands (foods).

https://www.dictionary.com/browse/kernos

"Ochre (rarely spelled ocher and often referred to as yellow ochre) is one of a variety of forms of iron oxide which are described as earth-based pigments. These pigments, used by ancient and modern artists, are made of iron oxyhydroxide, which is to say they are natural minerals and compounds composed of varying proportions of iron (Fe3 or Fe2), oxygen (O) and hydrogen (H)." (Hirst, Kris (15 April 2017). "Ochre - The Oldest Known Natural Pigment in the World") https://www.thoughtco.com/ochre-the-oldest-known-natural-pigment-172032

"Ochre (British English) ( OH-kər; from Greek: ὤχρα, from ὠχρός, ōkhrós, pale) or ocher (American English) is a natural clay earth pigmentwhich is a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand.It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced by this pigment, especially a light brownish-yellow. A variant of ochre containing a large amount of hematite, or dehydrated iron oxide, has a reddish tint known as "red ochre" (or, in some dialects, ruddle)."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ochre

"The use of red ochre in the prehistoric architecture of Central Anatolia has long been recognized. Scholars have often argued that its use in architecture has a symbolic role, and that it has been used in sacred parts of ritual buildings. This paper examines red‐painted buildings in the prehistoric settlements of Central Anatolia. Recently, a building with red‐coloured plastered walls and floors was found in Chalcolithic Çatalhöyük West. The technique of Raman Spectroscopy has been applied to identify the red pigment and results show that it is red ochre, which contains predominantly hematite, Fe2O3." (Erdogu B, and Ulubey A. 2011. Colour symbolism in the prehistoric architecture of central Anatolia and Raman Spectroscopic Investigation of red ochre in Chalcolithic Çatalhöyük. Oxford Journal Of Archaeology 30(1):1-11.) https://www.scribd.com/document/93900374/Erdogu-ulubey-Colour-Symbolism-in-the-Prehistoric-Architecture

![]()

![]()

Top and front views of the terracotta ring object with Indus Script Hypertexts (zebu, bird, pot), in Okayama Orient Museum.

The hieroglyphs zebu, bird and circular pot (ring) are read rebus:

I suggest that this terracotta ring objects kernoi rings are Indus Script Hypertexts with the following hieroglyph components:

1.. Zebu, bos indicus: पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'zebu, bos indicus taurus' Rupaka, 'metaphor' or rebus (similar sounding homonym): पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'magnetite, ferrite ore: Fe3O4'.

pōḷa 'zebu' Rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite ore'. पोळ (p. 534) [ pōḷa ]

m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus,

and set at large.पोळा (p. 534) [ pōḷā ] m (पोळ) A festive day for cattle,--

the day of new moon of श्रावण or of भाद्रपद. Bullocks are exempted from labor;

variously daubed and decorated; and paraded about in worship.पोळींव (p. 534)

[ pōḷīṃva ] p of पोळणें Burned, scorched, singed, seared. (Marathi)

2.Bird, black drongo: pōlaḍu 'black drongo bird' (Telugu) Rupaka, 'metaphor'

or rebus: पोलाद pōlāda n ( or P) Steel. पोलादी a Of steel. (Marathi) bulad

'steel, flint and steel for making fire' (Amharic); fUlAd 'steel' (Arabic)

pōlāda 'steel', pwlad (Russian), fuladh (Persian) folādī (Pashto)

![]()

![Image result for black drongo zebu]() Zebu, bos indicus PLUS black drongo bird (perched on the back of the bull) This bird is called పసులపోలిగాడు pasula-pōli-gāḍu 'friend of cattle'.

Zebu, bos indicus PLUS black drongo bird (perched on the back of the bull) This bird is called పసులపోలిగాడు pasula-pōli-gāḍu 'friend of cattle'.

3. Ring or circle:

karã̄ 'wristlets, bangles' rebus khār खार् 'blacksmith, iron worker'

4. Pot: kuṇḍá1 n. (RV. in cmpd.) ʻ bowl, waterpot ʼ KātyŚr., ʻ basin of water, pit ʼ MBh. (semant. cf. kumbhá -- 1), °ḍaka -- m.n. ʻ pot ʼ Kathās., °ḍī -- f. Pāṇ., °ḍikā -- f. Up. 2. *gōṇḍa -- . [← Drav., e.g. Tam. kuṭam, Kan. guṇḍi, EWA i 226 with other ʻ pot ʼ words s.v. kuṭa -- 1]1. Pa. kuṇḍi -- , °ḍikā -- f. ʻ pot ʼ; Pk. kuṁḍa -- , koṁ° n. ʻ pot, pool ʼ, kuṁḍī -- , °ḍiyā -- f. ʻ pot ʼ; Kt. kuṇi ʻ pot ʼ, Wg. kuṇḍäˊi; Pr. künǰúdotdot; ʻ water jar ʼ; Paš. weg. kuṛã̄ ʻ clay pot ʼ < *kũṛā IIFL iii 3, 98 (or poss. < kuṭa -- 1), lauṛ. kuṇḍalīˊ ʻ bucket ʼ; Gaw. kuṇḍuṛīˊ ʻ milk bowl, bucket ʼ; Kal. kuṇḍṓk ʻ wooden milk bowl ʼ; Kho. kúṇḍuk, °ug ʻ milk bowl ʼ, (Lor.) ʻ a kind of platter ʼ; Bshk. kūnḗċ ʻ jar ʼ (+?); K. kŏnḍ m. ʻ metal or earthenware vessel, deep still spring ʼ, kọ̆nḍu m. ʻ large cooking pot ʼ, kunāla m. ʻ earthenware vessel with wide top and narrow base ʼ; S. kunu m. ʻ whirlpool ʼ, °no m. ʻ earthen churning pot ʼ, °nī f. ʻ earthen cooking pot ʼ, °niṛo m.; L. kunnã̄ m. ʻ tub, well ʼ, °nī f. ʻ wide -- mouthed earthen cooking pot ʼ, kunāl m. ʻ large shallow earthen vessel ʼ; P. kū̃ḍā m. ʻ cooking pot ʼ (←H.), kunāl, °lā m., °lī f., kuṇḍālā m. ʻ dish ʼ; WPah. cam. kuṇḍ ʻ pool ʼ, bhal. kunnu n. ʻ cistern for washing clothes in ʼ; Ku. kuno ʻ cooking pot ʼ, kuni, °nelo ʻ copper vessel ʼ; B. kũṛ ʻ small morass, low plot of riceland ʼ, kũṛi ʻ earthen pot, pipe -- bowl ʼ; Or. kuṇḍa ʻ earthen vessel ʼ, °ḍā ʻ large do. ʼ, °ḍi ʻ stone pot ʼ; Bi. kū̃ṛ ʻ iron or earthen vessel, cavity in sugar mill ʼ, kū̃ṛā ʻ earthen vessel for grain ʼ; Mth. kũṛ ʻ pot ʼ, kū̃ṛā ʻ churn ʼ; Bhoj. kũṛī ʻ vessel to draw water in ʼ; H. kū̃ḍ f. ʻ tub ʼ, kū̃ṛā m. ʻ small tub ʼ, kū̃ḍā m. ʻ earthen vessel to knead bread in ʼ, kū̃ṛī f. ʻ stone cup ʼ; G. kũḍ m. ʻ basin ʼ, kũḍī f. ʻ water jar ʼ; M. kũḍ n. ʻ pool, well ʼ, kũḍā m. ʻ large openmouthed jar ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; Si. ken̆ḍiya, keḍ° ʻ pot, drinking vessel ʼ.2. N. gũṛ ʻ nest ʼ (or ← Drav. Kan. gūḍu ʻ nest ʼ, &c.: see kulāˊya -- ); H. gõṛā m. ʻ reservoir used in irrigation ʼ.Addenda: kuṇḍa -- 1: S.kcch. kūṇḍho m. ʻ flower -- pot ʼ, kūnnī f. ʻ small earthen pot ʼ; WPah.kṭg. kv́ṇḍh m. ʻ pit or vessel used for an oblation with fire into which barley etc. is thrown ʼ; J. kũḍ m. ʻ pool, deep hole in a stream ʼ; Brj. kū̃ṛo m., °ṛī f. ʻ pot ʼ.(CDIAL 3264) Rupaka, 'metaphor' or Rebus: kō̃da -कोँद 'kiln'; furnace' (Kashmiri)

Vikalpa: Circle:*varta2 ʻ circular object ʼ or more prob. ʻ something made of metal ʼ, cf. vartaka -- 2 n. ʻ bell -- metal, brass ʼ lex. and vartalōha -- . [√vr̥t?] Pk. vaṭṭa -- m.n., °aya -- m. ʻ cup ʼ; Ash. waṭāˊk ʻ cup, plate ʼ; K. waṭukh, dat. °ṭakas m. ʻ cup, bowl ʼ; S. vaṭo m. ʻ metal drinking cup ʼ; N. bāṭā, ʻ round copper or brass vessel ʼ; A. bāṭi ʻ cup ʼ; B. bāṭā ʻ box for betel ʼ; Or. baṭā ʻ metal pot for betel ʼ, bāṭi ʻ cup, saucer ʼ; Mth. baṭṭā ʻ large metal cup ʼ, bāṭī ʻ small do. ʼ, H. baṭṛī f.; G. M. vāṭī f. ʻ vessel ʼ.(CDIAL 11347)

dāẽ 'tied' rebus dhā̆vaḍ 'iron smelter.' Rupaka, 'metaphor' or Rebus: bhaṭa, 'furnace'' baṭa 'iron'(Gujarati).

Section 3. Indus Script hypertexts/artifacts of Nindowari, Kulli, Nal cultures of Balochistan related to metalwork competence

Thanks to Asko Parpola for the brilliant identification of 'squirrel' hieroglyph in Nindowari and other seal inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora. (www.harappa.com/script/indus-writing.pdf page 128)

"Nindowari is an important settlement of the Kulli culture. The Kulli culture was a prehistoric culture in southern Balochistan(Gedrosia) in Pakistan

ca. 2500 - 2000 BCE....A popular motif is the zebu-bull."https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kulli_culture

Kulli people were trading partners of Sarasvati (Indus Valley) Civilization.

https://web.archive.org/web/20060619010132/http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Article/593757

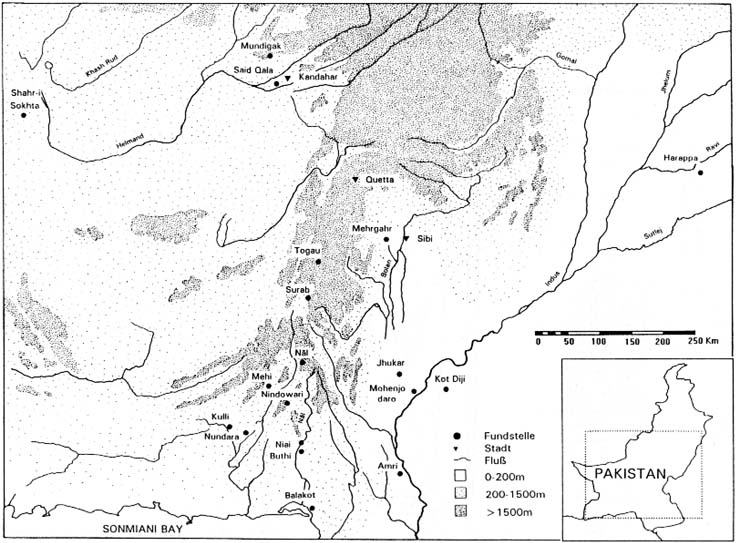

![Fig. 3 Findspots mentioned]()

(After Fig. 3 in Paul Yule, 2013) Nindowari, Kulli, Nal Buthi in Balochistan

![]() Rhyton (drinking vessel), zebushaped. Painted terracotta. Pakistan,

Rhyton (drinking vessel), zebushaped. Painted terracotta. Pakistan,

Nindowari site, 2300-2000 BCE, Kulli culture, the time of the Indus civilization.

Guimet Museum, Paris.

Map showing the main sites of Middle Asia in the third millennium BCE.

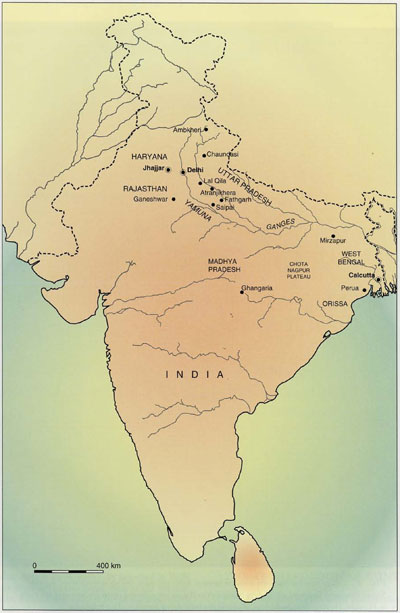

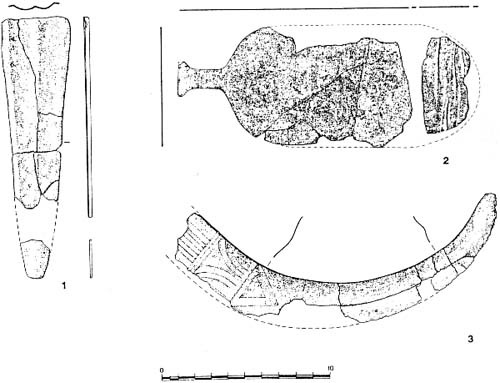

Excerpts from Paul Yule's article (2013):

[quote] A silver dagger-like blade (Fig. 1.1) and in the same material an unusual implement (Fig. 1.2), both which I examined and recorded in 1985, are on permanent exhibition in the National Museum in Delhi. Hargreaves also mentions the silver "unidentified object, No. 20" on p. 33 which is probably the "cult object" (quotation marks mine) in our

![Fig. 1.1 Dagger blade NM 2622.- 1.2 Cult object NM 2620.- 1.3 Harvesting knife NM 2619. Figs. 1.1-1.3 Sohr Damb]() |

Fig. 1.1 Dagger blade NM 2622.- 1.2 Cult object NM 2620.- 1.3 Harvesting knife NM 2619. Figs. 1.1-1.3 Sohr Damb

|

Fig. 1.2, since the other two objects are readily identifiable. In addition, inquiries in the Museum yielded a repousé silver harvesting knife or hand sickle (Fig. 1.3), which, like the other two objects, is registered in the accessions record (38). The source given is the "DGA" (Director General of Archaeology). The number "26" in the inventory number attests to the accessioning of the three pieces in 1926, doubtless from Hargreaves's excavation, and not those of his predecessors. The three pieces are sequentially numbered and no further silver objects appear to belong to this lot. Confirmation of the find circumstances lies in Hargreaves's description "...one fragment shows small parallel flutings in repousé", evidently a reference to our dagger blade. The dagger blade by no means measures 20 cm in length, but the harvesting knife is approximately this size. The hand sickel is fragmentary and reconstructed from 21 fragments. Fresh breaks are evident. Little imagination is required to explain their multiplication over the years from eight to 21. Fresh breaks are visible.

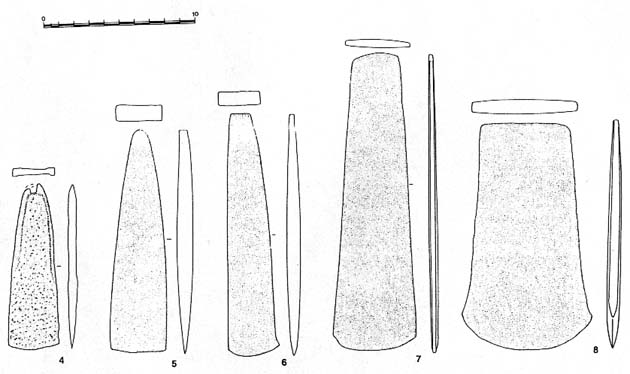

![Fig. 2.4-6. From Sohr Damb. 2.7-8 from Mohenjo daro. - 2.4 Palstaves A 9782.- 2.5 NM 2614.- 2.6 NM 2616.- 2.7 & 2.8 Mohenjo daro Museum, no inv. nos.]() |

Fig. 2.4-6. From Sohr Damb. 2.7-8 from Mohenjo daro. - 2.4 Palstaves A 9782.- 2.5 NM 2614.- 2.6 NM 2616.- 2.7 & 2.8 Mohenjo daro Museum, no inv. nos.[unquote]

|

"Nindowari (Urdu: نندارہ) , also known as Nindo Damb, is a Kulli archaeological site, dating back to chalcolithicperiod, in Kalat District of Balochistan, Pakistan. Archaeological investigation of the site suggests that the Nindowari complex was occupied by the Harappans before the Kulli civilization arrived and that the Kulli culture was related to or possibly derived from the Harappan culture...Nindowari is located some 240 kilometres (150 mi) northwest of Karachi, in Ornach Valley in Tehsil Wadh of the Kalat District. It is located on the right bank of the Kud River, a tributary of the Porali River...The site, spread over an area of 124 acres and 75 feet (23 m) high, is the largest Kulli complex site discovered so far...The central mound near the platform rose to a height of 82 feet (25 m) and consisted of large stones and boulders. The summit of the mound was accessed via a staricase from the platform showing this mound was considered a monument. Another mound, called Kulliki-an Damb (Mound of Potteries), was located 590 feet (180 m) south of the main mound...The site was discovered by Beatrice De Cardi in 1957.[1] French Archaeological Mission, led by Jean-Marie Casal, and Department of Archaeology, Pakistan later carried out the Nindowari excavations from 1962 till 1965, uncovering traces of a Kulli settlement dating back to the third millennium BC.[1] These excavations unearthed Kulli-Harappan pottery and vases with animal figures, mostly bulls and birds. Terracotta figurines of women adorned with jewelry with elaborate details were also discovered. Nal ware (old pottery from Indus Civilization) excavated from the site suggested a pre-Kulli occupation and that the Harrapans were settled in the area in early periods (3200 - 2500 BC)."(McIntosh, Jane R. (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 87; Neil Asher Silberman, ed. (2012). The Oxford Companion To Archaeology (2 ed.). Oxford University Press.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nindowari![]()

Section 4. Nindowari-damb seal 01,Harappa,Mohenjo-daro

inscriptions show'squirrel 'šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻflying squirrelʼ,'guild master'.

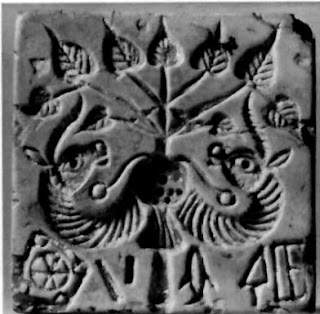

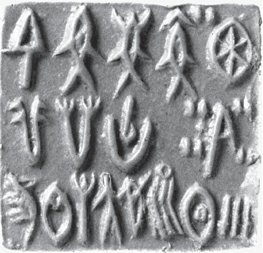

![]() Nd-1 Nindowari0-damb seal 01 shows 'squirrel'šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻflying squirrelʼ,'guild master'.

Nd-1 Nindowari0-damb seal 01 shows 'squirrel'šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻflying squirrelʼ,'guild master'.

kanac 'corner' rebus: kañcu 'bronze'

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेढा [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) The circumscript is composed of four 'splinters': gaNDa 'four' rebus: kaNDa 'implements', kanda 'fire-altar'

खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] 'A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon)' Rebus: kaNDa 'implements' (Santali).

kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge'

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metalcasting'. Thus, metalcasting smithy/forge.

kanka, karṇaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo', 'engraver, scribe, account'

Hieroglyph: 8 short strokes: gaṇḍa 'four' rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, this hieroglyph-multiplex or hypertext signifies: iron implements workshop.

![]() Indian palm squirrel, Funambulus Palmarum There are also other seals with signify the 'squirrel' hieroglyph.

Indian palm squirrel, Funambulus Palmarum There are also other seals with signify the 'squirrel' hieroglyph. ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Nindowari-damb seal Nd0-1; Mohenjo-daro seal m-1202; Harappa tablet h-771; Harappa tablet h-419

Nindowari-damb seal Nd0-1; Mohenjo-daro seal m-1202; Harappa tablet h-771; Harappa tablet h-419 ![]() m1634 ceramic stoneware bangle (badge)

m1634 ceramic stoneware bangle (badge)

![]() Read from r. to l.:

Read from r. to l.:

Vikalpa: The prefix![]() Sign 403: Hieroglyph: bārī , 'small ear-ring': H. bālā m. ʻbraceletʼ (→ S. ḇālo m. ʻbracelet worn by Hindusʼ), bālī, bārī f. ʻsmall ear -- ringʼ, OMārw. bālī f.; G. vāḷɔ m. ʻ wire ʼ, pl. ʻ ear ornament made of gold wire ʼ; M. vāḷā m. ʻ ring ʼ, vāḷī f. ʻ nose -- ring ʼ.(CDIAL 11573) Rebus: bārī 'merchant' vāḍhī, bari, barea 'merchant' bārakaśa 'seafaring vessel'. If the duplication of the 'bangle' on Sign 403 signifies a plural, the reading could be: karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus: khār 'blacksmith, iron worker'.

Sign 403: Hieroglyph: bārī , 'small ear-ring': H. bālā m. ʻbraceletʼ (→ S. ḇālo m. ʻbracelet worn by Hindusʼ), bālī, bārī f. ʻsmall ear -- ringʼ, OMārw. bālī f.; G. vāḷɔ m. ʻ wire ʼ, pl. ʻ ear ornament made of gold wire ʼ; M. vāḷā m. ʻ ring ʼ, vāḷī f. ʻ nose -- ring ʼ.(CDIAL 11573) Rebus: bārī 'merchant' vāḍhī, bari, barea 'merchant' bārakaśa 'seafaring vessel'. If the duplication of the 'bangle' on Sign 403 signifies a plural, the reading could be: karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus: khār 'blacksmith, iron worker'.

![]()

Sign 403 is a duplication of

![]()

bun-ingot shape. This shape is signified on a zebu terracotta pratimā found at Harappa and is consistent with

mūhā mẽṛhẽt process of making unique bun-shaped ingots (See Santali expression and meaning described below):

![]()

I suggest that

![]()

Sign 403 is read:

dul mūhā mẽṛhẽt 'cast iron ingot'.

Thus, the hypertext ![]()

may read:

1. dul mūhā mẽṛhẽt uṟukku 'cast iron ingot,steel' or 2. khār uṟukku 'blacksmith, steel'.

If he squirrel is read as šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻflying squirrel' rebus: śrēṣṭhin 'guild master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa), the reading of the hypertext ![]() is:

is:

1. dul mūhā mẽṛhẽt śrēṣṭhin 'cast iron ingot, guild-master' or 2. khār śrēṣṭhin 'blacksmith, guild-master'.

![]() Slide 33. Early Harappan zebu figurine with incised spots magnetite, citizen.

Slide 33. Early Harappan zebu figurine with incised spots magnetite, citizen.

mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends (Santali) खोट (p. 212) [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge. (Marathi)

An alternative reading for 'squirrel' hieroglyph is also suggested:

The sequence of hieroglyphs![]() Squirrel + Sign 403 signifies two professional responsibilities/functions 1. khār 'blacksmith'; 2. seṭhi ʻwholesale merchant' (Sindhi).

Squirrel + Sign 403 signifies two professional responsibilities/functions 1. khār 'blacksmith'; 2. seṭhi ʻwholesale merchant' (Sindhi).

Alternatively, 1. dul mūhā mẽṛhẽt 'cast iron ingot'; 2. khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri) or seṭhi ʻwholesale merchant' (Sindhi) or śrēṣṭhin 'guild master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa).

Thus, two readings are possible for the 'squirrel' hieroglyph: khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri) and/or seṭhi ʻwholesale merchant' (Sindhi) orśrēṣṭhin 'guild master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa)

Hieroglyph: squirrel (phonetic determinant): खार [ khāra ] A squirrel, Sciurus palmarum. खारी [ khārī ] f (Usually खार) A squirrel. (Marathi)

A homonymous hieroglyph or allograph: arms with bangles: karã̄ n. pl. ʻwristlets, banglesʼ.(Gujarati)(CDIAL 2779) Rebus: khār खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन्, which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b,l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-basta 'bellows of blacksmith'.with inscription.

*śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ1]Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ?(CDIAL 12723) Rebus: guild master:*śrēṣṭrī2 ʻ line, ladder ʼ. [For mng. ʻ line ʼ conn. with √śriṣ2 cf. śrḗṇi -- ~ √śri. -- See śrití -- . -- √śriṣ2]Pk. sēḍhĭ̄ -- f. ʻ line, row ʼ (cf. pasēḍhi -- f. ʻ id. ʼ. -- < EMIA. *sēṭhī -- sanskritized as śrēḍhī -- , śrēṭī -- , śrēḍī<-> (Col.), śrēdhī -- (W.) f. ʻ a partic. progression of arithmetical figures ʼ); K. hēr, dat. °ri f. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 12724) Rebus: śrḗṣṭha ʻ most splendid, best ʼ RV. [śrīˊ -- ]Pa. seṭṭha -- ʻ best ʼ, Aś.shah. man. sreṭha -- , gir. sesṭa -- , kāl. seṭha -- , Dhp. śeṭha -- , Pk. seṭṭha -- , siṭṭha -- ; N. seṭh ʻ great, noble, superior ʼ; Or. seṭha ʻ chief, principal ʼ; Si. seṭa, °ṭu ʻ noble, excellent ʼ. śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ]Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ, seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M. śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2?)(CDIAL 12725, 12726)

![]()

m1202

From r. to l.:

barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: bharat 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' (Marathi) pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'goldsmith guild'

muhA 'ingot'; dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' muhA 'ingot' (Together, dul muhA 'cast iron ingot');

Squirrel 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Indus Script hypertext is khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa) Vikalpa: tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy';

kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe';

aduru 'harrow' Rebus: aduru 'native unsmelted metal';bhaTa 'warrior' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace';

kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe'; muhA 'ingot,

quantity of iron ore smelted out of the smelter'.

![]() h771

h771dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' muhA 'ingot' (Together, dul muhA 'cast iron ingot');

Squirrel 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Indus Script hypertext is khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa) Vikalpa: tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy';

dula 'two' Rebus: dul 'cast metal or casting'.

Thus, the epigraph with three hieroglyph-multiplexes read rebus: metal castings, cast metal ingot, guild-master (pewter-zinc alloy.)

![]() h419

h419Squirrel 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Indus Script hypertext is khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa) Vikalpa: tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy';

maṇḍā 'warehouse, workshop' (Konkani).

Thus, guild-master's warehouse.

Longest inscription m0314 of Indus Script Corpora is catalogue of a guild-master. The guild master is signified by Indus Script hypertext 'squirrel' hieroglyph 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Rebus: plaintext: khār 'blacksmith'

śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa).

![]() The guild-master signs off on the inscription by affixing his hieroglyph:

The guild-master signs off on the inscription by affixing his hieroglyph:

![]()

![]() m0314 Seal impression, Text 1400 Dimension: 1.4 sq. in. (3.6 cm) Marshall 1931 (Vol. II, p. 402).

m0314 Seal impression, Text 1400 Dimension: 1.4 sq. in. (3.6 cm) Marshall 1931 (Vol. II, p. 402).

This is perhaps the longest inscriptionof Indus Script Corpora.

m0314 The indus script inscription is a detailed account of the metal work engaged in by the Indus artisans. It is a professional calling card of the metalsmiths' guild of Mohenjodaro used to affix a sealing on packages of metal artefacts traded by Meluhha (mleccha)speakers.

![]() The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is

The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is ![]() Squirrel as shown on Seal impression

Squirrel as shown on Seal impression![]() Flipped vertically is likey to signify 'squirrel' as on Nindowari-damb seal 01

Flipped vertically is likey to signify 'squirrel' as on Nindowari-damb seal 01

All hieroglyphs are read from r. to l.

Line 1:

![]() eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop.

eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop.

Fish + lid: aya dhakka,Rebus: aya dhakka 'bright iron/alloy metal'.

Fish + fin: aya khambhaṛā rebus: aya kammaṭa 'alloy metal mint, coiner, coinage'

Fish + sloping stroke, aya dhāḷ ‘metal ingot’ (Vikalpa: ḍhāḷ = a slope; the inclination of a plane (G.) Rebus: : ḍhāḷako = a large metal ingot (G.)

khaṇḍa 'arrow' rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'

Thus, line 1 reads: bright iron/alloy metal, alloy metal mint, large metal ingot (ox-hide)

Line 2:

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेढा [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) The circumscript is composed of four 'splinters': gaNDa 'four' rebus: kaNDa 'implements', kanda 'fire-altar' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, this hieroglyph-multiplex or hypertext signifies: iron implements workshop.

S. baṭhu m. ‘large pot in which grain is parched, Rebus; bhaṭṭhā m. ‘kiln’ (P.) baṭa = a kind of iron (G.) Vikalpa: meṛgo = rimless vessels (Santali) bhaṭa ‘furnace’ (G.) baṭa = kiln (Santali); baṭa = a kind of iron (G.) bhaṭṭha -- m.n. ʻ gridiron (Pkt.) baṭhu large cooking fire’ baṭhī f. ‘distilling furnace’; L. bhaṭṭh m. ‘grain—parcher's oven’, bhaṭṭhī f. ‘kiln, distillery’, awāṇ. bhaṭh; P. bhaṭṭh m., ṭhī f. ‘furnace’, bhaṭṭhā m. ‘kiln’; S. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ‘distil (spirits)’. (CDIAL 9656) Rebus: meḍ iron (Ho.) PLUS muka 'ladle' rebus; mū̃h 'ingot', quantity of metal got out of a smelter furnace (Santali).Thus, this hieroglyph-multiplex (hypertext) signifies: iron ingot.

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metalcasting'. Thus, metalcasting smithy/forge.

kanka, karṇaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo', 'engraver, scribe, account'

Thus line 2 signifies metal products -- iron ingots, metalcastings (of smithy/forge iron metals workshop) handed over to Supercargo, (a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale).

Line 3:

kolmo ‘three’ (Mu.); rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Telugu)

A. goṭ ‘a fruit, whole piece’, °ṭā ‘globular, solid’, guṭi ‘small ball, seed, kernel’; B. goṭā ‘seed, bean, whole’; Or. goṭā ‘whole, undivided’, goṭi ‘small ball, cocoon’, goṭāli ‘small round piece of chalk’; Bi. goṭā ‘seed’; Mth. goṭa ‘numerative particle’ (CDIAL 4271) Rebus: koṭe ‘forging (metal)(Mu.) Rebus: goṭī f. ʻlump of silver' (G.) PLUS infix of sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, the hieroglyph-multiplex or hypertext signifies: forged silver workshop.

![]() m009

m009

Hieroglyph is a loop of threads formed on a loom or loose fringes of a garment. This may be seen from the seal M-9 which contains the sign:

धातु [p= 513,3] m. layer , stratum Ka1tyS3r. Kaus3. constituent part , ingredient (esp. [ and in RV. only] ifc. , where often = " fold " e.g. त्रि-ध्/आतु , threefold &c ; cf.त्रिविष्टि- , सप्त- , सु-) RV. TS. S3Br. &c (Monier-Williams) dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.).; S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)

Rebus: M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; (CDIAL 6773) धातु primary element of the earth i.e. metal , mineral, ore (esp. a mineral of a red colour) Mn. MBh. &c element of words i.e. grammatical or verbal root or stem Nir. Pra1t. MBh. &c (with the southern Buddhists धातु means either the 6 elements [see above] Dharmas. xxv ; or the 18 elementary spheres [धातु-लोक] ib. lviii ; or the ashes of the body , relics L. [cf. -गर्भ]) (Monier-Williams. Samskritam)

Thus, this hieroglyph signifies three types of ferrite ore: magnetite, hematite and laterite (poLa, bicha, goTa). Vikalpa: Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271) Rebus: goṭī f. ʻlump of silver' (G.)

Hieroglyph: Archer with bow and arrow on one hand: kamāṭhiyo = archer; kāmaṭhum = a bow; kāmaḍ, kāmaḍum = a chip of bamboo (G.) kāmaṭhiyo a bowman; an archer (Skt.lex.) Rebus: kammaṭi a coiner (Ka.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Ta.) kammaṭa = mint, gold furnace (Te.)

kolom 'rice plant' rebus:kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

kanac 'corner' rebus: kañcu 'bronze' Vikalpa: (A.) kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner's lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295).

Hieroglyph: squirrel: *śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ1]Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ?(CDIAL 12723) Rebus: guild master khāra, 'squirrel', rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri). *śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ1] Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ? (CDIAL 12723) Rebus: śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ] Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ,seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M. śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2?) (CDIAL 12726) I suggest that the šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ? is read rebus: śeṭhī, śeṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ (Marathi) or eṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ(Prakrtam)

Thus, line 3 signifies: bronze guild master of smithy/forge, mint for three types of ferrite mineral (magnetite, hematite, laterite)

The three lines together, the engtire inscription of m0314 is a metalwork cagtalogue of a guild-master of workshops working in:

(1) native unsmelted metal, metal mint, large metal ingot (oxhide)

(2) metal products -- iron ingots, metalcastings (of smithy/forge iron metals workshop) handed over to Supercargo, (a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale)

(3)smithy/forge, mint for three types of ferrite mineral (magnetite, hematite, laterite)

![]() Nal ware and terracotta figurines with drawings of bulls (similar to the seals above) showed that Nindowari was once occupied by the Harappans.

Nal ware and terracotta figurines with drawings of bulls (similar to the seals above) showed that Nindowari was once occupied by the Harappans.

Naushahdu Matka,

a jar made around (2700 - 1800 BCE) found in Nausharo. poḷa 'zebu' rebus: poḷa 'magnetite, ferrite

ore' meḍh 'tied rope' rebus: meḍ 'iron' med 'copper'(Slavic) medha 'yajna'

medhā 'dhanam' (Niruktam)

![]()

![]()

4.1a Ns-3A Nausharo 3.2 dia

4.2b Nd-3A Nindowari-damb 3.6 dia

4.2c H-243B Harappa 1.4 dia

4.2d H-349B Harappa 1.3x1.3

4.2e Pk-21A Pirak 2.3x1.5

4.2f

Section 5. Terracotta Ring-shaped Object with Animal Figurines and a Miniature Pot of the Balochistan Tradition in the Okayama Orient Museum by Akinori Uesugi (2013)

https://tinyurl.com/y7xxo7kp

Kulli terracotta ring (also called Kernos Ring) with pot, two zebu (bos indicus), black drongo is Indus Script hypertext to signify pōḷā magnetite ore, pwlad 'steel' dhā̆vaḍ, 'smelter' kō̃da,'furnace'

https://tinyurl.com/y9n3ppyt A Note on a Terracotta Ring-shaped Object with Animal Figurines and a Miniature Pot of the Balochistan Tradition in the Okayama Orient Museum by Akinori Uesugi (2013)

Abstract. In this paper, a terracotta ring-shaped object with animal figurines and a miniature pot in the collection of the Okayama Orient Museum is reported. Although its provenance is unknown, its uniqueness is important for understanding the nature of the Kulli culture in Balochistan during the late third millennium BCE. Similar objects that are known from the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean region may be related to this rare object of the Kulli culure.

Description of the Kulli terracotta object with Indus Script Hypertext, ca. 3rd millennium BCE

The object consists of a ring with three short legs, two humped bulls, one bird and a miniature pot (Figures above). A whitishslip (light grey 2.5Y 8/2) is executed over areddish orange clay (dull orange 7.5YR 7/3)and paintings are made in black (brownish black 10YR 3/1- yellowish grey

2.5Y 4/1).The measurements are shown in Table 1. The bird is placed on the rear side of thering with a tall cylindrical stand.

![]()

Terracotta ring objects (called 'Kernos Ring') are widely distributed in Kulli culture (After Fig. 8 in Akinori Uesugi's monograph)

Chronological distribution of ring-shapedobjects in Southwest Asia from 5000 BCE(After Fig. 9 in Akinori Uesugi's monograph)The ring object dated to 5000 BCE is from Tell Kosak Shamali in northern Syria. Similar objects continue upto the first millennium BCE.

Kulli style animal figures (zebu, bird) in Okayama Orient Museum

https://www.scribd.com/document/384387101/Harappan-Ring-Kernoi-A-Study-BM-Pandehttps://tinyurl.com/y9568l2x

Section 6. Kernoi rings identify metal workers and Kernunnos rings are writing

instruments, ink-stands

This is an addendum to: Kernos ring of Kulli with wealth accounting ledgers of khār, 'blacksmith' working with poḷa 'magnetite ore', poḷaḍ 'steel' https://tinyurl.com/ya744hnz 2. Kulli terracotta ring with pot Indus Script hypertexts signify pōḷāmagnetite ore, pwlad 'steel' dhā̆vaḍ, 'smelter' kō̃da,'furnace'

The objects shown atop the kernoi rings include narrow-necked jars and animals or birds. I suggest that all these objects are Indus Script Hypertexts signifying metalwork catalogues, wealth-accounting ledgers. This rebus reading explains the reason why the kernoi rings become sacred objects, yielding a messaging system to declare the contributions made by metalwork artisans and seafaring merchants to augmenting a nation's wealth.

Narrow-necked pots: Hieroglyph, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.'

ḍ̠āṛhū̃ 'pomegranate' (Sindhi) Rebus: ḍhālako 'a large metal ingot'.

पोळ [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods. pōḷī, ‘dewlap, honeycomb’. Rebus: pola ‘magnetite ore’ (Munda. Asuri)

pōlaḍu,'black drongo' rebus pōlaḍ 'steel' Hypertext: miṇḍā́l 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati) Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic languages)

The word mr̥du is shown on the grape vine held on the right hand of a Yavana (Greek) fighter on a Bharhut sculptural frieze. The word for a grapevine is mr̥dvi. The rebus signifiers are mr̥dh 'fight, battle', mr̥du 'iron'.

![]()

The soldier carries a broad sword on his left hand. The metaphor is that he signifies a mint-worker working with 'dotted circle' hypertext, dhā̆vaḍ 'iron smelter'. The fish-fins above this dotted circle signify

khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner,coinage'. Thus, he is a mint-worker, guard of the treasures created in the metals manufactories.

I suggest that the name K(C)ernunnos on the Pillar of Boatmen and on the Gundestrup Cauldron is related to the torcs which are distinct identifiers of the seated person as a blacksmith. The torc or the ring called in Meluhha (Indus Script Corpora) karã̄ n. pl.wristlets, bangles' rūpaka, 'metaphor'or rebus: khār 'blacksmith'. Thus, I suggest that the kernos ring is a signifier of a blacksmith's work. This etymological trace explains why the Kulli kernos ring has the added Indus Script hypertexts of two zebu, bos indicus, and black drongo, both signifying, respectively poḷa 'magnetite ore', poḷaḍ 'steel'. These hypertexts are added on the Kulli kernos ring to signify wealth accounting ledgers of metalwork catalogues.

khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन्, which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-basta खार-बस््त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith. -büṭhü । लोहकारभित्तिः f. the wall of a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -bāy -बाय् । लोहकारपत्नी f. a blacksmith's wife (Gr.Gr. 34). -dŏkuru । लोहकारायोघनः m. a blacksmith's hammer, a sledge-hammer. -gȧji -or -güjü । लोहकारचुल्लिः f. a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -hāl -हाल् । लोहकारकन्दुः f. (sg. dat. -höjü -हा&above;जू&below;), a blacksmith's smelting furnace; cf. hāl 5. -kūrü -कूरू&below; । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter. -koṭu -। लोहकारपुत्रः m. the son of a blacksmith, esp. a skilful son, who can work at the same profession. -küṭü -क&above;टू&below; । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter, esp. one who has the virtues and qualities properly belonging to her father's profession or caste. -më˘ʦü 1 - । लोहकारमृत्तिका f. (for 2, see [khāra 3] ), 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore. -nĕcyuwu -; लोहकारात्मजः m. a blacksmith's son. -nay -नय् । लोहकारनालिका f. (for khāranay 2, see [khārun] ), the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting. -ʦañĕ -। लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wān वान् । लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 3). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil. (Kashmiri) ![]()

Detail from the interior plate. Gundestrup Cauldron. Kernunnos holds a torc -- signifier of a kernos ring-- on his right hand. Indus Script Hypertexts signify metalwork catalogues: badhia 'rhinoceros' Rebus: badhi 'carpenter'; badhoe 'worker in wood and iron'. पंजा pañjā 'claw of a tiger' rebus: पंजा pañjā 'kiln, smelter.; फडा phaḍā f (फटा S) The hood of Coluber Nága Rebus:phaḍa फड ' metals manufactory, company, guild, public place'; kūdī 'twig' kuṭhi 'smelter'.

![]() C(K)ernunnos on the Pillar of the Boatmen, from the Musée national du Moyen Âge (Museum of the Middle Ages), in Paris, France"The theonym [C]ernunnos appears on the Pillar of the Boatmen, a Gallo-Roman monument dating to the early 1st century CE, to label a god depicted with stag's antlers in their early stage of annual growth. [Both antlers have torcs hanging from them...The name has been compared to a divine epithet Carnonos in a Celtic inscription written in Greek characters at Montagnac, Hérault (as καρνονου, karnonou, in the dative case).A Gallo-Latin adjective carnuātus, "horned," is also found." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cernunnos The torcs of Kernunnos are relatable to the kernos ring.

C(K)ernunnos on the Pillar of the Boatmen, from the Musée national du Moyen Âge (Museum of the Middle Ages), in Paris, France"The theonym [C]ernunnos appears on the Pillar of the Boatmen, a Gallo-Roman monument dating to the early 1st century CE, to label a god depicted with stag's antlers in their early stage of annual growth. [Both antlers have torcs hanging from them...The name has been compared to a divine epithet Carnonos in a Celtic inscription written in Greek characters at Montagnac, Hérault (as καρνονου, karnonou, in the dative case).A Gallo-Latin adjective carnuātus, "horned," is also found." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cernunnos The torcs of Kernunnos are relatable to the kernos ring.

"For more than one thousand years, people from every corner of the Greco-Roman world sought the hope for a blessed afterlife through initiation into the Mysteries of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis. In antiquity itself and in our memory of antiquity, the Eleusinian Mysteries stand out as the oldest and most venerable mystery cult. Despite the tremendous popularity of the Eleusinian Mysteries, their origins are unknown. Because they are lost in an era without written records, they can only be reconstructed with the help of archaeology. This book provides a much-needed synthesis of the archaeology of Eleusis during the Bronze Age and reconstructs the formation and early development of the Eleusinian Mysteries. The discussion of the origins of the Eleusinian Mysteries is complemented with discussions of the theology of Demeter and an update on the state of research in the archaeology of Eleusis from the Bronze Age to the end of antiquity." (Michael B. Cosmopoulos, 2015, Bronze Age Eleusis and the Origins of the Eleusinian Mysteries, Cambridge University Press.)

Kernoi rings

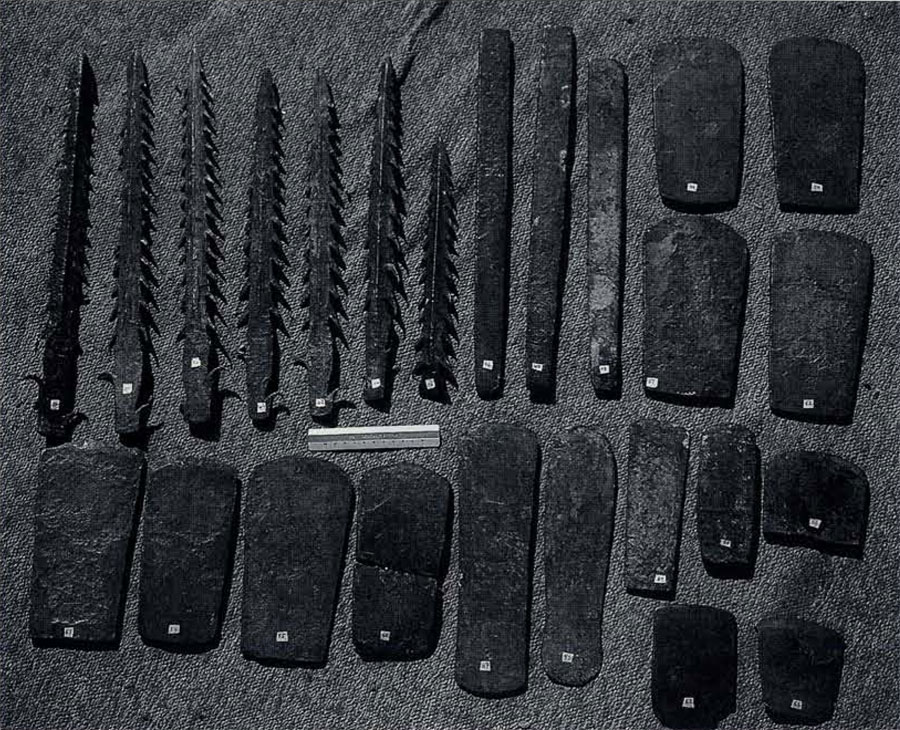

The pottery of Mohenjo-dara, one of the two major urban centers of the Indus Valley civilization (2500-2000 B.C.) is described and documented. The authors survey Harappan ceramic technology and style, and develop an important and unique approach to vessel form analysis and terminology. Included is Leslie Alcock's account of the pottery from the 1950 excavations by Sir Mortimer Wheeler.University Museum Monograph, 53

“Hollow pottery rings surmounted by small vessels are common ‘ritual’ objects at Mediterranean and Levantine sites where they are known by the Greek name kernos (pl.kernoi).More rarely they occur in Mesopotamian contexts…Two or more small pots attached to the top side of a hollow ring so that liquid poured into the pots would run down into the hollow ring connecting them…Only six certain and two possible fragmentary examples are recorded from the UM excavations…..Because these objects are so rare in South Asia, mention should be made of two other fragmentary examples found at Harappa. Both of these have also been discussed by BM Pande in his detailed study of ring-kernoi’. The first example was published in a photograph only by Vats (1940: Pl. LXXI:6) with no description in the text. The second example, almost half a hollow ring with scars where three small vessels were attached, was excavated by Wheeler in 1946 but remained unpublished until Pande’s study…Pande’s excellent study of these enigmatic objects cites examples from Mediterranean, Egyptian, Levantine, and Mesopotamian sites ranging in date from the mid-fourth millennium BCE to at least the early centuries.” [BM Pande, 1971, Harappan Ring-Kernoi: A study. East & West 21 (3-4), pp. 311-324); George Dales, Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Leslie Alcock, 1986, UPenn Museum of Archaeology, Excavations at Mohenjo Daro, Pakistan: The Pottery, with an Account of the Pottery from the 1950 Excavations of Sir Mortimer Wheeler, p.226).

In the typology of ancient Greek pottery, the kernos (Greek κέρνος or κέρχνος, plural kernoi) is a pottery ring or stone tray to which are attached several small vessels for holding offerings -- "a terracotta vessel with many little bowls stuck on to it. In them there is sage, white poppy heads, wheat, barley, peas (?), vetches (?), pulse, lentils, beans, spelt (?), oats, cakes of compressed fruit, honey, olive oil, wine, milk, and unwashed sheep's wool. When one has carried this vessel, like a liknophoros, he tastes of the contents"[Phillippe Borgeaud, Mother of the Gods: From Cybele to the Virgin Mary (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, English translation 2004)]. “KernosRings (Fig. 92:1-6). Hollow pottery rings surmounted by small vessels are common ‘ritual’ objects at Mediterranean and Levantine sites where they are known by the Greek name kernod (pl. kernoi). More rarely they occur in Mesopotamian contexts…Bases: attached to the top side of the hollow ring; usually piered through to connect vessel interior with hollow ring, but two examples (Fig. 92:2,6) are solid…Two or more small pots attached to the top side of a hollow ring so that liquid poured into the pots would run down into the hollow ring connecting them…Only six certain and two possible fragmentary examples are recorded from the UM excavations…Because these objects are so rare in South Asia, mention should be made of two other fragmentary examples found at Harappa. Both of these have also been discussed by B.M. Pande in his detailed study of ‘ring-kernoi’….Pande reports that one of his colleagues who was present during Wheeler’s excavations says the object was discovered near Cemetery R37, Burial 5, and belongs to the mid-levels of the Harappa culture…Pande’s excellent study of these enigmatic objects cites examples from Mediterranean, Egyptian, Levantine, and Mesopotamian sites ranging in date from the mid-fourth-millennium BCE to at least the early centuries CE. Reference should be made to his study for details of the elaborate ritual nature of many of these Western examples.” (George Dales, Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Leslie Alcock, 1986, Excavations at Mohenjo-daro, Pakistn: The pottery, with an account of the pottery from the 1950 excavations of Sir Mortimer Wheeler, UPenn Museum of Archaeology, p.226).

GF Dales reported the find of a kernos from Mohenjo-daro. (GF Dales, 1965, New investigations at Mohenjo-daro, Archaeology, XVIII, 2, pp. 145-50).

“A fragment of a pottery kernod – circular tube with small vases at intervals – associated with the mud brick embankment was found in the recent excavations at Mohenjo-daro, conducted by Dales. His view that the object had ‘not hitherto been reported from Harappan sites’ does not appear to be totally correct, for a few other like examples have been unearthed at Harappan sites. In the excavations at Harappa, a similar object was found in the Great Granary area. But for the variation with regard to the form of the vase, the object from Harappa belongs to the same class of objects as the latest Mohenjo-daro example.The fragmentary Harappa kernos has only extant vase resembling a cup with a splayed-out mouth and plain featureless rim, as against a miniature-sized globular jar with a narrow neck and externally-curved rim of the Mohenjo-daro specimen. In the same group of vessels may also be included two more examples – one each from Mohenjo-daro and Harappa – which are lodged in the Central Antiquities Collection Safdarjang Tomb Baradari, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi. The earlier Mohenjo-daro specimen, which is also fragmentary, has two intact vases, akin to the Harappa one. The other specimen, from Wheeler’s excavations at Harappa, has only the half segment of the tube surviving and the vases are broken and lost.That the four specimens – two each from Mohenjo-daro and Harappa – belong to the same class of objects known as kernos, is beyond doubt. This is obvious from their general shape and characteristic features comparable to the ones found in a vast area outside India and in large numbers.”(pp.311-312).

"The kernoi have a wide distribution both in space and time. The distribution in time ranges from about the middle of the 4th millennium BCE to the early centuries CE, and, in fact, to the modern times in certain parts of the world. The area of distribution includes Greece (and the islands), Crete, Cyprus, Israel, Egypt and modern Iraq (and the peripheral regions)...The main focus of distribution of the kernos is mainly Greece, Crete and the adjoining islands, where these occur for the first time in the Early Minoan (c. 2500-2100 BCE) and pre-Mycenaen (c. 2500-1800 BCE) to Late Minoan (c. 1550-1150 BCE) down to the late Greek and Roman times (c. 6th cent. BCE onwards). Thus a continuous tradition of use can be discerned for an interminable period of about three thousand years, the tradition surviving even in the modern times, with subsequent mofications and alterations, in the Greek Orthodox church…At Palaikastro site ‘was found a clay cover with a conical pierced top and a kind of door in the side, as covers for lamps…(which) were set on the kernoi, when they were decked for ritual use.’ (RM Dawkins, Excavations at Palaikastro III, Annual of the British School of Athens, X, 1903-1904, p.221)...At Kourtes site, (Nilsson,The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion, Lund, 1927, pp. 116-117, fig. 19.. This kernos consists of a ‘hollow ring (diameter 19 cm) upon which six small jugs with narrow necks and spreading mouths are placed alternately with three coarsely made human figurines, of which one holds his arms to his head, another to his breast, while the third graps the handles of the vases next to him. As Xanthoudides justly remarks, this very pecular feature connects the vessel with the group of dancing women fastened on a common ring-shaped base from Palaikastro’" (BM Pande, opcit, p.314)/A variant of the ring-kernos has a number of small vessels attached to the ring and communicating with the interior. Some of these have also attached to them plastic serpents, bulls’ heds and perchaing birds. (Nilsson, opcit., p. 117).

“That the object kernos – ring kernos or the other types – had ritualistic function in ancient Greece, or is a cult-object in the Megiddo cult, is beyond doubt. In Cyprus, more often than not, these are found in graves as a part of the funerary furniture. This is evident from their location in a site (whereever found from the excavations) connected with cult, rituals or as accompanying the dead. Even the shape of the ring-kernos – clearly the result of a complex evolution – and the variety of forms or objets represented on the ring-kernoi prove that they were ritualistic vessels. Ancient Greek and Roman literature attests to this fact. Harrison, while discussing the kernophoria, has described two types of kernos on the authority of Athenaeus and the scholiasts on Nikander etc. The first of these was a winnowing fan which in the beginning was a simple agricultural instrument, but was subsequently mysticized by the religion of Dionysus. But there was another kind of kernos, which according to Athenaeus, was ‘a vessel made of earthenware,having in it many little cups fastened to it’, in which while poppies, wheat, barley, pulse etc. were kept. It ws thereafter carried aloft and certain rites were performed and was distributed to those who had done so. Athenaeus also gives a long list of the contents of the kernos. From Eleusis, where such an objet had been found in the excavations, are also available accounts of the officials mentioning a vessel…which is identical to the kernos of Athenaeus…The kernos from Haghios Nikolaos, again an example of the composite variety, is important, for, ‘inside it was found a clay lamp with one wick and two holes in the cover’, which conforms to the description given by the scholiast on Nikander. According to Xanthoudides, ‘the kernos was a sacred vessel not used exclusively at the Eleusinian mysteries, but also in the worship of other gods, as is known from the cults of Rhea Cybele, Attis, and the Corybantes’.”(BM Pande, opcit., pp.320-321)

It is thus obvious that the kernos – the ring-kernos or the other types – was a vessel connected, in ancient Greece and Crete, with harvest and used in the related festivals. The ring kernoi from Israel, which might have ‘originated in the footed ring-vases of early Cyprus and Egypt’, have pomegranates, doves, gazelles on them. These are symbolic and mark ‘its function in the fertility cult’ and the miniature jars ‘contained wine, the fruit of the grape’. Thus, ‘the kernos ring was probably for libations: the liquid would be poured into the cups to circulate throughout the doves, pomegranates, and jars, symbolizing the fertility of the earth and the fructifying of its produce’. (BM Pande opcit, p. 321).

![]()

Fig. 92.1,3 Mohenjo-daro kernos ring with pots

Terracotta ring-kernos (offering vase)

- Period:

- Cypro-Geometric I

- Date:

- ca. 1050–950 B.C.

- Culture:

- Cypriot

- Medium:

- Terracotta

- Dimensions:

- H. 4 7/16 in. (11.3 cm)

- Classification:

- Vases

- Credit Line:

- The Cesnola Collection, Purchased by subscription, 1874–76

- Accession Number:

- 74.51.659

Kernos (and "souce-boat"), pottery. Early Cycladic II-III period, 2500 to 2000 BC. Vessel found in burial site in Rivari on Mlios, excavations in 1997. Archaeological Museum of Milos.

Céramiques de tous les pays et de toutes les époques

Terracotta ring-kernos (offering vase) Cypriot

From the Cesnola Collection, Accession # 74.51.660 http://www.ipernity.com/doc/laurieannie/24387123Terracotta kernos (vase for multiple offerings)

- Period:

- Cypro-Archaic I

- Date:

- 750–600 B.C.

- Culture:

- Cypriot

- Medium:

- Terracotta

- Dimensions:

- H. 4 1/8 in. (10.5 cm); diameter 7 1/8 in. (18.1 cm)

- Classification:

- Vases

- Credit Line:

- The Cesnola Collection, Purchased by subscription, 1874–76

- Accession Number:

- 74.51.688

Terracotta. Kernos. 2300-2200 BCE

Fig.5 Ring kernoi from Cyprus “…an example of a ring-kernos of the White Painted II variety from Cyprus has, over an elaborately painted ring with a basket handle, bull’s and goat’s heads, pomegranates and miniature vases (fig.5).”(BM Pande, opcit., p.318)

Fig.6 Ring kernoi from Cyprus “Late Mycenaean (c. 1500-1100 BCE), Cyprus, comprises ‘a ring upon which three vessels, two with narrow mouths and one cup with a handle, and a bull’s head is fastened.” (BM Pande, opcit., p.318)

“The Palestinian examples, notably from Megiddo and Gezer, are again of an elaborate type The Megiddo specimen (fig 10) has, on a ring base, one gazelle head, two amphorae, two pomegranates, two doves and one cup which all communicate with the hollow base. The gazelle head is decorated with red lines, has pierced eyes and orifice through mouth; the other pots or birds are also painted or decorated likewise. The Gezer examples also have alternating figures of birds and pomegranates (fig. 11).” (BM Pande, opcit., pp. 318-319)

“The Palestinian examples, notably from Megiddo and Gezer, are again of an elaborate type The Megiddo specimen (fig 10) has, on a ring base, one gazelle head, two amphorae, two pomegranates, two doves and one cup which all communicate with the hollow base. The gazelle head is decorated with red lines, has pierced eyes and orifice through mouth; the other pots or birds are also painted or decorated likewise. The Gezer examples also have alternating figures of birds and pomegranates (fig. 11).” (BM Pande, opcit., pp. 318-319)

Fig. 13 Ring kernoi from Melos

![]() Kernos carried on her head. "The kernos was carried in procession at the Eleusinian Mysteries atop the head of a priestess, as can be found depicted in art. A lamp was sometimes placed in the middle of a stationary kernos. The verb kernophorein means "to bear the kernos"; the noun for this is kernophoria; Stephanos Xanthoudides, "Cretan Kernoi," Annual of the British School at Athens 12 (1906), p. 9."

Kernos carried on her head. "The kernos was carried in procession at the Eleusinian Mysteries atop the head of a priestess, as can be found depicted in art. A lamp was sometimes placed in the middle of a stationary kernos. The verb kernophorein means "to bear the kernos"; the noun for this is kernophoria; Stephanos Xanthoudides, "Cretan Kernoi," Annual of the British School at Athens 12 (1906), p. 9."See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kernos

The votive plaque known as the Ninnion Tablet depicting elements of the Eleusinian Mysteries, discovered in the sanctuary at Eleusis (mid-4th century BCE). In this votive plaque depicting elements of the Eleusinian Mysteries, a female figure (top center of rectangular portion) wears a kernos on her head

Kulli terracotta ring (also called Kernos Ring) with pot, two zebu (bos indicus), black drongo is Indus Script hypertext to signify pōḷā magnetite ore, pwlad 'steel' dhā̆vaḍ, 'smelter' kō̃da,'furnace'. ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

HTTPS://WWW.SCRIBD.COM/DOCUMENT/384387101/HARAPPAN-RING-KERNOI-A-STUDY-BM-PANDE

JOURNAL ARTICLE

Harappan Ring-Kernoi: A Study

B. M. Pande

East and West

Vol. 21, No. 3/4 (September-December 1971), pp. 311-323

https://tinyurl.com/yd3off2b

This is an addendum to:

Ta. kāṇ (kāṇp-, kaṇṭ-) to see, consider, investigate, appear, become visible; n. sight, beauty; kāṇkai knowledge; kāṇpu seeing, sight; kāṭci sight, vision of a deity, view, appearance; kāṇikkai voluntary offering, gift to a temple, church, guru or other great person; kāṭṭu (kāṭṭi-) to show; n. showing; kaṇṇu (kaṇṇi-) to purpose, think, consider; kaṇ-kāṭci gratifying spectacle, exhibition, object of curiosity. Ma. kāṇuka to see, observe, consider, seem; kāṇi visitor, spectator; kāṇikka to show, point out; n. offering, present; kāṭṭuka to show, exhibit; kār̤ca, kār̤ma eyesight, offering, show, spectacle. Ko. kaṇ-/ka·ṇ- (kaḍ-)to see; ka·ṭ- (ka·c-) to show; kaḍ aṯ- (ac-), kaḍ ayr- (arc-) to find out; ka·ṇky payment of vow to god; kaŋga·c wonderful sight such as never seen before. To.ko·ṇ- (koḍ-) to see; ko·ṭ- (ko·ṭy-) to show; ko·ṇky offering to Hindu temple or to Kurumba; koṇy act of foretelling or of telling the past. Ka. kāṇ (kaṇḍ-) to see, appear; n. seeing, appearing; kāṇike, kāṇke sight, vision, present, gift; kāṇuvike seeing, appearing; kāṇisu to show, show oneself, appear; kaṇi sight, spectacle, ominous sight, divination. Koḍ. ka·ṇ- (ka·mb-, kaṇḍ-) to see; seem, look (so-and-so); ka·ṭ- (ka·ṭi-) to show. Tu. kāṇůsāvuni, kāṇisāvuni to show, represent, mention; kāṇikè, kāṇigè present to a superior. Te. kanu (allomorph kān-), kāncu to see; kānupu seeing, sight; kānipincu to appear, seem; show; kānuka gift offered to a superior, present, tribute; kaṇṭãbaḍu to appear, be seen, come in view; kanukali seeing, sight. Kol. kanḍt, kanḍakt seen, visible. Nk. kank er- to appear (< *kanḍk or the like). Pa. kanḍp- (kanḍt-) to look for, seek. Ga. (Oll.) kanḍp- (kanḍt-) to search. Kur. xannāto be pleasant to the eye, be of good effect, suit well. Br. xaning to see. Cf. 1159 Ta. kaṇ; ? cf. 1172 Ta. kaṇṭavaṉ.(DEDR 1443) இரத்தக்காணிக்கை iratta-k-kāṇikkai, n. < id. +. `Blood-present,' an endowment in the form of a gift of land rent-free for the support of the heirs of warriors wounded or killed in battle; போரில்வீழ்ந்த வீரருடைய மைந்தர்க்குக் கொடுக்கும் மானியம். (M.M.) காணிக்கை kāṇikkai, n. < காண்-. [T. kā- nuka, K. Tu. kāṇike, M. kāṇikka.] Voluntary offering, commonly in money, gold, fruits; gift to a temple or church; present to a guru or other great person; கடவுளர்க்கேனும் பெரியோர் கட்கேனும் சமர்ப்பிக்கும் பொருள். வேதாளநாதன் மகி ழுங் காணிக்கையாகி (சேதுபு. வேதாள. 34).காணிக்கைத்தட்டு kāṇikkai-t-taṭṭu, n. < காணிக்கை +. Salver for receiving gifts; கா ணிக்கைவாங்குந் தாலம்.

कारणिक mfn. (g. काश्य्-ादि) " investigating , ascertaining the cause " , a judge Pan5cat.; a teacher MBh. ii , 167. (Monier-Williams) कारणी or कारणीक kāraṇī or kāraṇīka a (कारण S) That causes, conducts, carries on, manages. Applied to the prime minister of a state, the supercargo of a ship &c. 2 Useful, serviceable, answering calls or occasions. (Marathi) Supercargo = a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.![]()

![]()

![]()

This is an addendum to:

Kris Hirst re-opens a Farmer et al discovery of Harappan illiteracy. Zebu on Nausharo pottery signifiesपोळ pōḷa magnetite ferrite ore in Indus writing wealth-accounting ledgers https://tinyurl.com/yalshmuy

There is a possibility that the metaphor of Kernos' rings is echoed in Kernunno's Gundestrup cauldron. Both metaphors celebrate animal hieroglyphs which signify wealth-accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues.

Both the metaphors are celebration of wealth-creation by metalwork artisans. His name is written as kernunno. This is cognate: kārṇī m. ʻprime minister, supercargo of a ship'; kanahār m. ʻ 'helmsman, fishermanʼ. Since k(c)ernunno is also derivable from शृङ्गम् śṛṅgam 'horn', which adorns Kernunnos's head, the semantics of jangaḍ 'cargo invoiced on approval basis' are also echoed.

On the significance of Indus Script hypertexts in Gundestrup Cauldron, see:

Cernunnos/Kernunno of Gundestrup Cauldron/Pilier des Nautes, is Tvaṣṭṛ Triśiras r̥ṣi of R̥gveda on Indus Script seal m0304, evokes cognate kārṇī 'supercargo of a ship' https://tinyurl.com/y7gf3r8b

The seated, bearded person on the Pillar of Boatmen, wears a shawl wich echoes the cotton shawl worn by Mohenjo-daro priest with neatly trimmed beard.The person seated in penance on one register of the Pillar of Boatmen, wears three strands as shawl. tri-dhātu 'three strands' rebus: tri-dhātu 'three ferrite ores' PLUS two torcs on the stag-horns which constitute his hair-dress. dhāu 'strand (of rope or plait)' rebus: dhāū 'red stone minerals. panca 'shawl, dhoti' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace, smelter'.

It has been demonstrated in Epigraphia Indus Script -- Hypertexts and Meanings (3 vols.) that writing was used to document wealth accounting ledgers.

![]()

![]()

The hieroglyphs of the types assembled on kernoi rings are consistent with this hypertext tradition and translated as wealth accounting ledgers related to metalwork catalogues, consistent with the objective of the Indus Script writing system to document wealth-creation and trading activities of artisan guilds and seafaring merchant guilds.

![]()

![]() Terracotta kernos from the Cycladic period (ca.2000 BC), found at Melos. "The kernos was carried in procession at the Eleusinian Mysteries atop the head of a priestess, as can be found depicted in art. A lamp was sometimes placed in the middle of a stationary kernos" (The verb kernophorein means "to bear the kernos"; the noun for this is kernophoria; Stephanos Xanthoudides, "Cretan Kernoi," Annual of the British School at Athens 12 (1906), p. 9.)

Terracotta kernos from the Cycladic period (ca.2000 BC), found at Melos. "The kernos was carried in procession at the Eleusinian Mysteries atop the head of a priestess, as can be found depicted in art. A lamp was sometimes placed in the middle of a stationary kernos" (The verb kernophorein means "to bear the kernos"; the noun for this is kernophoria; Stephanos Xanthoudides, "Cretan Kernoi," Annual of the British School at Athens 12 (1906), p. 9.)

"In the typology of ancient Greek pottery, the kernos (Greek κέρνος or κέρχνος, plural kernoi) is a pottery ring or stone tray to which are attached several small vessels for holding offerings. Its unusual design is described in literary sources, which also list the ritual ingredients it might contain. The kernos was used primarily in the cults of Demeter and Kore, and of Cybele and Attis.The Greek term is sometimes applied to similar compound vessels from other cultures found in the Mediterranean, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and South Asia."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kernos

The presence of Meluhha settlements has been attested in cuneiform records. It is possible that like the Phoenician merchants, the seafaring Meluhha merchants had also trade contacts with many regions where kernos rings which carry signifiers of Indus Script Hypertexts proclaiming metalwork, have been found across Eurasia.

Examples can be cited from Mediterranean, Egyptian, Levantine and Mesopotamian sites from mid-fourth millennium BCE to early centuries of Common Era. These examples have been documented by BM Pande.

The thesis of this monograph is that:

1. the kernos ring was an ink-stand containing iron oxide pigment used by scribes; and

2. the kernos ring designed in Sarasvati Civilization (Mohenjo-daro artifacts presented by George Dales et al in 1986 and Kulli culture artifacts presented in Akinori Uesugi's monograph (2012), spread to entire Eurasia.

I suggest that the Greek word kernos has cognates in Indian sprachbund (speech union) with particular reference to a scribe, engraver, accountant, ledger-keeper (to record wealth-accounting ledgers of Indus Script metalwork catalogues): kāraṇika m. ʻ teacher ʼ MBh., ʻ judge ʼ Pañcat. [kā- raṇa -- ]Pa. usu -- kāraṇika -- m. ʻ arrow -- maker ʼ; Pk. kāraṇiya -- m. ʻ teacher of Nyāya ʼ; S. kāriṇī m. ʻ guardian, heir ʼ; N. kārani ʻ abettor in crime ʼ; M. kārṇī m. ʻ prime minister, supercargo of a ship ʼ, kul -- karṇī m. ʻ village accountant ʼ.(CDIAL 3058)கணக்குச்சுருணை kaṇakku-c-curuṇai, n. < id. +. Roll or file of accounts on palmyra leaves, kept by a village accountant; கணக் கோலைக்கற்றை.கணக்கப்பிள்ளை kaṇakka-p-piḷḷai, n. < gaṇaka +. 1. Village accountant, cashier, bursar, writer, agent, shipping clerk, bill collector; கணக்கன். 2. Man of the kaṇakkaṉ caste; ஒரு சாதியான். கணக்கன் kaṇakkaṉ, n. < gaṇaka. [M. kaṇakkaṉ.] 1. Accountant, book-keeper; கணக் கெழுதுவோன். (திருவாலவா. 30, 22.) 2. See கணக்கப்பிள்ளை, 1. 3. A certain caste; ஒரு சாதி. (இலக். வி. 52, உரை.) 4. Arithmetician; கணக்கில் வல்லவன். (W.) கருணீகம் karuṇīkam, n. < karaṇa. [T. karaṇikamu.] Office of village accountant or karṇam; கிராமக்கணக்குவேலை. கருணீகன் karuṇīkaṉ, n. < id. 1. Village accountant; கிராமக்கணக்கன். கடுகை யொருமலை யாகக் . . . காட்டுவோன் கருணீகனாம் (அறப். சத. 86). 2. A South Indian caste of accountants; கணக்குவேலை பார்க்கும் ஒருசாதி.

காரணிக்கன் kāraṇikkaṉ, n. < id. Accountant; கணக்கன்.(Insc.) కరణము karaṇamu. [Skt.] n. A village clerk, a writer, an accountant. వాడు కూత కరణముగాని వ్రాతకరణముకాడు he has talents for speaking but not

for writing. స్థలకరణము the registrar of a district. कारणी or कारणीक kāraṇī or kāraṇīka a (कारण S) That causes, conducts, carries on, manages. Applied to the prime minister of a state, the supercargo of a ship (Marathi).

The examples of kernoi rings cited from Mohenjo-daro may date to ca. 3rd millennium BCE.

The most significant design feature which links the roots of the kernoi rings to Sarasvati Civilization relates to Indus Script Cipher with hypertexts. I have demonstrated that the hypertexts contained in almost all kernoi rings discovered so far from Eurasia relate to wealth accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues.

That kernoi ring metaphors validate Indus Script Cipher with roots in Sarasvati Civilization is explained by the hypertexts on the kernos ring, Samian.

This Kernos ring has a central tube on which small vessels with spouts are arranged. The small vessels feeding into the kernos are: a pomegranate, a shell, a toad, monkey, lion, ram, bull’s head, horns of a warrior, a woman. A small snake surrounds the tube. I suggest that all these are Indus Script Hypertexts with hieroglyph components to document wealth accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues.

The rebus readings of hypertexts are:

Pomegranate, Metal ingot: ḍ̠āṛhū̃ 'pomegranate' rebus: ḍhālako 'a large metal ingot'

Toad/frog, Metal taken out of a furnace: Kur. mūxā frog. Malt. múqe id. / Cf. Skt. mūkaka- id. (DEDR 5023) Rebus: mū̃h 'ingot' muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native

Monkey, armourer: kuṭhāru = amonkey (Sanskrit) Rebus: kuṭhāru 'armourer

Lion, brass: arye 'lion' rebus: arā 'brass'

Ram, iron: Tor. miṇḍ 'ram', miṇḍā́l 'markhor' (CDIAL 10310) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet 'iron' (Munda.Ho.). med 'copper' (Slavic languages)

Zebu, iron: pōḷā पोळ 'zebu' rebus pōḷā 'magnetite, ferrite ore'

Warrior, mint: kamaḍha 'archer' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'; bhaṭa 'warrior' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'

Woman, moltencast: era 'woman' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper'

Cobrahood, metals manufactory: phaḍā 'cobra hood' rebus phaḍā 'metals manufactory' paṭṭaḍa workshop (Telugu)

Shell, Artificer: Ta. ippi pearl-oyster, shell; cippi shell, shellfish, coconut shell for measuring out curds. Ma. ippi, cippi oyster shell. Ka. cippu, sippu, cimpi, cimpe, simpi, simpu, simpe oyster shell, mussel, cockle, a portion of the shell of a coconut, skull, a pearl oyster; (Gowda) cippi coconut shell. Tu. cippi coconut shell, oyster shell, pearl; tippi, sippi coconut shell. Te. cippa a shell; (kobbari co) coconut shell; (mōkāli co) knee-pan, patella; (tala co) skull; (muttepu co) mother-of-pearl. Go. (Ma.) ipi shell, conch (Voc. 174). / Cf. Turner, CDIAL, no. 13417, *sippī-; Pali sippī- pearl oyster, Pkt. sippī- id., etc. (DEDR 2835) *sippī ʻ shell ʼ. [← Drav. Tam. cippi DED 2089] Pa. sippī -- , sippikā -- f. ʻ pearl oyster ʼ, Pk. sippī -- f., S. sipa f.; L. sipp ʻ shell ʼ, sippī f. ʻ shell, spathe of date palm ʼ, (Ju.) sip m., sippī f. ʻ bivalve shell ʼ; P. sipp m., sippīf. ʻ shell, conch ʼ; Ku. sīp, sīpi ʻ shell ʼ; N. sipi ʻ shell, snail shell ʼ; B. sip ʻ libation pot ʼ, chip ʻ a kind of swift canoe ʼ S. K. Chatterji CR 1936, 290 (or < kṣiprá -- ?); Or.sipa ʻ oyster shell, mother -- of -- pearl, shells burnt for lime ʼ; Bi. sīpī ʻ mussel shells for lime ʼ; OAw. sīpa f. ʻ bivalve shell ʼ, H. sīp f.; G. sīp f. ʻ half an oyster shell ʼ, chīpf. ʻ shell ʼ; M. śīp, śĩp f. ʻ a half shell ʼ, śĩpā m. ʻ oyster shell ʼ; -- Si. sippiya ʻ oyster shell ʼ ← Tam.(CIAL 13417) śilpin ʻ skilled in art ʼ, m. ʻ artificer ʼ Gaut., śilpika<-> ʻ skilled ʼ MBh. [śílpa -- ] Pa. sippika -- m. ʻ craftsman ʼ, NiDoc. śilpiǵa, Pk. sippi -- , °ia -- m.; A. xipini ʻ woman clever at spinning and weaving ʼ; OAw. sīpī m. ʻ artizan ʼ; M. śĩpī m. ʻ a caste of tailors ʼ; Si. sipi -- yā ʻ craftsman ʼ.(CDIAL 13471)

Cup/pot, furnace Pk. vaṭṭa -- m.n., ˚aya -- m. ʻ cup ʼ; Ash. waṭāˊk ʻ cup, plate ʼ; K. waṭukh, dat. ˚ṭakas m. ʻ cup, bowl ʼ; S. vaṭo m. ʻ metal drinking cup ʼ; N. bāṭā, ʻ round copper or brass vessel ʼ; A. bāṭi ʻ cup ʼ; B. bāṭā ʻ box for betel ʼ; Or. baṭā ʻ metal pot for betel ʼ, bāṭi ʻ cup, saucer ʼ; Mth. baṭṭā ʻ large metal cup ʼ, bāṭī ʻ small do. ʼ, H. baṭṛī f.; G. M. vāṭī f. ʻ vessel ʼ.(CDIAL 11347) Rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'.

Kernos ring, Samian, ca. 600 BCE. (After Vierneisel,K., 1961, 'Neue Tonfiguren aus dem Heraion von Samios Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaologischen Instituts 76:25-59 von Leutsch E.L. and F.W. Schneidewin edd 1951 Corpus Paroemiographorum Graeocorum 1839-51, app.25). Hera may have been the first deity to whom the Greeks dedicated an enclosed roofed temple sanctuary, at Samos about 800 BCE.Her name is attested in Mycenaean Greek written in the Linear B syllabic script as 𐀁𐀨, e-ra, appearing on tablets found in Pylos and Thebes.("The Linear B word e-ra". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of Ancient languages. Raymoure, K.A. "e-ra".) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hera(Santali)

The kernoi rings were essential writing instruments in furthering the documentation of accounting ledgers using Indus Script.

“Most ring kernoi come from Iron Age I levels and the majority are connected with Philistine sites or sites where Philistine cultural influence can be detected.”( Brad E. Kelle, Megan Bishop Moore, Israel's Prophets and Israel's Past: Essays on the Relationship of Prophetic Texts and Israelite History in Honor of John H. Hayes, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 01-Nov-2006, p.153).

Excerpt from: George Dales, Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Leslie Alcock, 1986, Excavations at Mohenjo Daro, Pakistan: The Pottery, with an Account of the Pottery from the 1950 Excavations of Sir Mortimer Wheeler, UPenn Museum of Archaeology, 1986, p.226 Fig. 92.1,3 Mohenjo-daro kernos ring with pots

![]() (cited in BM Pande 1971(embedded)

(cited in BM Pande 1971(embedded)