Text message A3b: ranku ‘liquid measure’ rebus: ranku‘tin’

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.+

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar'rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

goṭā ‘round pebble’ Rebus: goṭā 'gold-braid'khoṭa 'ingot, wedge' Rebus: गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe.

aḍar 'harrow' Rebus: aduru 'native metal' (Kannada)

ayo ‘fish’ rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda)

karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith'

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

![]()

![]()

![]()

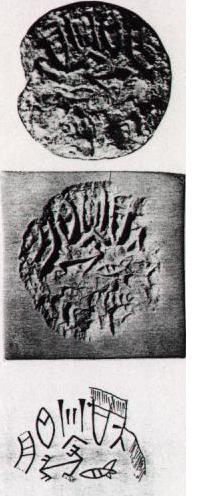

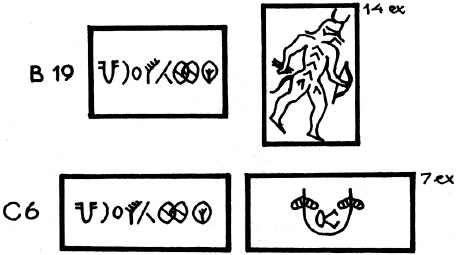

![]() Field symbol: Three hieroglyphs constitute the field symbol in obverse of tablets: goṭā ‘round pebble’ Rebus: goṭā 'gold-braid' khoṭa 'ingot, wedge' Rebus: गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe.

Field symbol: Three hieroglyphs constitute the field symbol in obverse of tablets: goṭā ‘round pebble’ Rebus: goṭā 'gold-braid' khoṭa 'ingot, wedge' Rebus: गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe. kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) cf. āra-kūṭa, 'brass' Old English ār 'brass, copper, bronze' Old Norse eir 'brass, copper', German ehern 'brassy, bronzen'. kastīra n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. 2. *kastilla -- .1. H. kathīr m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; G. kathīr n. ʻ pewter ʼ.2. H. (Bhoj.?) kathīl, °lā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; M. kathīl n. ʻ tin ʼ, kathlẽ n. ʻ large tin vessel ʼ.(CDIAL2984) कौटिलिकः kauṭilikḥ कौटिलिकः 1 A hunter.-2 A blacksmith.

mẽḍhā ʻcrook, hook' rebus: meD ‘iron’, med ‘copper’ (Slavic)

Text message of A4: meḍ 'body' rebus: meḍ 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic) PLUS koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ

'workshop'.

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'. Thus, ingots and implements

kolom‘three’ rebus:kolimi‘smithy, forge’

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'(Semantic determinative)

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Text message of A5: kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’ rebus: kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’; Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) kauṭilikḥ कौटिलिकः 1 A hunter.-2 A blacksmith PLUS kanac ‘corner’ rebus: kancu ‘bell-metal’

baraḍo 'spine, backbone' rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish-fin rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'.

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

Text message of A6: ayo ‘fish’ rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) PLUS dhāḷ 'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot'

kamaḍha 'crab' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. ḍato = claws of crab (Santali) Rebus: dhātu 'mineral ore' (Rigveda).

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Inscription A7: The field symbol has a variant of Field symbol A6 prefixed with two additional hieroglyph: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhata 'furnace'.

Text message of A7: koḍa 'sluice'; Rebus: koḍ 'artisan's workshop'

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda)

baraḍo 'spine, backbone' rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Field symbol: dotted circle? dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, haetite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'; dhāvḍā 'smelter'Text message of A8: kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'Field symbol: Two hieroglyphs constitute the field symbol in obverse of tablets:taṭṭal 'five' rebus: ṭhaṭṭha brass (i.e. alloy of copper + zinc) *ṭhaṭṭha1 ʻbrassʼ. [Onom. from noise of hammering brass?]N. ṭhaṭṭar ʻ an alloy of copper and bell metal ʼ. *ṭhaṭṭhakāra ʻ brass worker ʼ. 1.Pk. ṭhaṭṭhāra -- m., K. ṭhö̃ṭhur m., S. ṭhã̄ṭhāro m., P. ṭhaṭhiār, °rā m.2. P. ludh. ṭhaṭherā m., Ku. ṭhaṭhero m., N. ṭhaṭero, Bi. ṭhaṭherā, Mth. ṭhaṭheri, H. ṭhaṭherā m.(CDIAL 5491, 5493) PLUS Svastika shape: sattva 'svastika' glyph Rebus: sattu, satavu, satuvu 'pewter' (Kannada) సత్తుతపెల a vessel made of pewter त्रपुधातुविशेषनिर्मितम् jasth जस्थ । त्रपु m. (sg. dat. jastas जस्तस्), zinc, spelter; pewter

baṭa 'rimless, wide-mouthed pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS ḍabu 'an iron spoon' (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo 'lump (ingot?).

Text messageA9: ayo ‘fish’ rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) PLUS dhāḷ 'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot'

koḍa 'sluice'; Rebus: koḍ 'artisan's workshop'

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

Field symbol: Five slanted strokes constitute the field symbol in obverse of tablets:taṭṭal 'five' rebus: ṭhaṭṭha brass (i.e. alloy of copper + zinc) *ṭhaṭṭha1 ʻbrassʼ. [Onom. from noise of hammering brass?]N. ṭhaṭṭar ʻ an alloy of copper and bell metal ʼ. *ṭhaṭṭhakāra ʻ brass worker ʼ. 1.Pk. ṭhaṭṭhāra -- m., K. ṭhö̃ṭhur m., S. ṭhã̄ṭhāro m., P. ṭhaṭhiār, °rā m.2. P. ludh. ṭhaṭherā m., Ku. ṭhaṭhero m., N. ṭhaṭero, Bi. ṭhaṭherā, Mth. ṭhaṭheri, H. ṭhaṭherā m.(CDIAL 5491, 5493) PLUS Svastika shape: sattva 'svastika' glyph Rebus: sattu, satavu, satuvu 'pewter' (Kannada) సత్తుతపెల a vessel made of pewter त्रपुधातुविशेषनिर्मितम् jasth जस्थ ।त्रपु m. (sg. dat. jastas जस्तस्), zinc, spelter; pewter

Text message A10:aḍar ‘harrow’ Rebus: aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul ‘casting’.

PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Field symbol: short-tailed caprid kid: ranku‘antelope’ rebus: ranku‘tin’ + xolā 'fish tail' rebus: kolhe 'smelter',

kol 'working in iron'

Text A11: Glyph ‘mountain’: మెట్ట [ meṭṭa ] or మిట్ట meṭṭa. [Tel.] n. Rising ground, high lying land, uplands. A hill, a rock. ఉన్నతభూమి, మెరక, పర్వతము, దిబ్బ. மேடு mēṭu , n. [T. meṭṭa, M. K. mēḍu.] 1. Height; உயரம். (பிங்.) 2. Eminence, little hill, hillock, ridge, rising ground; சிறுதிடர். (பிங்.) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic)

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Category B (21 items), 139 inscriptions

Field symbol: feeding trough + one-horned young bull: kondh ‘young bull’. kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’.kōḍu horn (Kannada. Tulu. Tamil) खोंड [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) Rebus: कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. खोट [khōṭa] Alloyed--a metal (Marathi).

PLUS

pattar ‘trough’ rebus: pattar‘goldsmiths’ guild’

Text B1:loa 'ficus glomerata' Rebus: loha 'copper, iron' PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metalcasting’ PLUS kamaḍha 'crab' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. ḍato = claws of crab (Santali) Rebus: dhātu 'mineral ore'.

khura ‘hoof’ rebus: ċhúrɔ ‘dagger’ (WPah.) 3727 kṣurá m. ʻ razor ʼ RV., ʻ sharp barb of arrow ʼ R., ˚rī -- f. ʻ knife, dagger ʼ lex., ˚rikā -- f. Rājat. [√kṣur]

ch -- forms, esp. in sense ʻ knife ʼ, are wide -- spread outside dial. bounds: -- Sk. chū˘rī -- f. ʻ knife, dagger ʼ lex., churikā -- f. Kathās., chūr˚ lex., Pa. churikā -- f., NiDoc. kṣura; Pk. chura -- m. ʻ knife, razor, arrow ʼ, ˚rī -- , ˚riā -- f. ʻ knife ʼ; Gy. pal. číri ʻ knife, razor ʼ, arm. čhuri ʻ knife ʼ, eur. čuri f., SEeur. čhurí, Ḍ. čuri f., Kt. c̣urīˊ, c̣uī; Dm. c̣húri ʻ dagger ʼ; Kal. c̣hūˊŕi ʻ knife ʼ; Bshk. c̣hur ʻ dagger, knife ʼ, Tor. c̣hū, Phal. c̣hūr f.; Sh. (Lor.) c̣ūr ʻ small knife ʼ; S. churī f. ʻ knife with a hooked blade ʼ; L. churī f. ʻ knife ʼ, awān. churā m.; P. churā m. ʻ large knife ʼ, ˚rī f. ʻ small do. ʼ, Ku. churo, ˚rī; N. churā ʻ razor ʼ, ˚ri ʻ knife ʼ; A. suri ʻ knife ʼ, B. churi; Or. churā ʻ dagger ʼ, ˚rī ʻ knife ʼ; Bi. chūrā ʻ razor ʼ; Mth. chūr, ˚rā ʻ dagger, razor ʼ, ˚rī ʻ small knife ʼ; Bhoj. Aw. lakh. chūrā ʻ razor ʼ; H. churā m. ʻ dagger, razor ʼ, ˚rī f. ʻ knife ʼ; G. charo m. ʻ large knife ʼ, ˚rī f. ʻ small do. ʼ (Bloch LM 415 wrongly < tsáru -- : churī ← H. or M.), M. surā m., ˚rī f.; Si. siriya ʻ dagger ʼ; -- Woṭ. čir ʻ dagger ʼ ← Psht. ← IA. Buddruss Woṭ 96.

kh -- forms: Pa. khura -- m. ʻ razor ʼ; Pk. khura -- m. ʻ knife, razor ʼ; K. khūru m. ʻ razor ʼ; S. khuryo m. ʻ grass -- scraper, tip of silver at the bottom of a scabbard ʼ; WPah. bhal. khuro m. ʻ razor ʼ; Ku. khuro -- muṇḍo ʻ the shaving of heads ʼ; N. khuro ʻ head of a spear, ferrule of a stick, pin at the top or bottom of a door; A. B. khurʻ razor ʼ (whence A. khurāiba ʻ to shave ʼ), Or. khura; Bi. khūr ʻ razor ʼ, khurā, ˚rī ʻ spiked part of the blade of a chopper which fits into the handle ʼ; H. khurā m. ʻ iron nail to fix ploughshare ʼ; Si. karaya ʻ razor ʼ.

kṣaura -- ; kṣurapra -- , kṣurabhāṇḍa -- ; *prakṣurikā -- ; gōkṣura -- , trikṣura -- .

Addenda: kṣurá -- : WPah.kṭg. ċhúrɔ m. ʻ dagger ʼ, Garh. khur, churī ʻ knife ʼ, A. spel. churī AFD 216.

3728 *kṣuraṇa ʻ scraping ʼ. [√kṣur]

Bi. mag. khurnī ʻ a kind of spade ʼ.

3729 kṣuráti ʻ cuts, scratches, digs ʼ, churáti ʻ cuts off, incises ʼ Dhātup. [√kṣur]

Pa. khurati ʻ scrapes ʼ, Pk. churaï ʻ breaks ʼ; G. chɔrvũ ʻ to dig up with a sharp spade ʼ. -- Ext. with -- ḍ -- : S. khurṛaṇu ʻ to scrape ʼ, khurṛi f. ʻ scrapings ʼ; -- with -- kk -- : S. khurka f. ʻ itching ʼ; L. khurkaṇ ʻ to scratch ʼ, P. khurkṇā; N. khurkanu ʻ to scrape ʼ; -- with -- cc -- : P. khurcṇā ʻ to scrape (a pot) ʼ; G. khurcā m. pl. ʻ scrapings ʼ. -- X trōṭayati: M. khurtuḍṇẽ ʻ to nip off ʼ.

3730 kṣurapra ʻ sharp -- edged like a razor ʼ BhP., m. ʻ sharp- edged arrow ʼ MBh., ʻ sharp -- edged knife ʼ Pañcat., ʻ a sort of hoe ʼ lex. [Cf. *prakṣurikā -- . -- kṣurá+?]

Pa. khurappa -- m. ʻ arrow with a horseshoe head ʼ; Pk. khurappa -- , ˚ruppa -- m. ʻ a kind of arrow, knife for cutting grass ʼ; S. khurpo m. ʻ a pot -- scraper ʼ; P. khurpā m., ˚pī f. ʻ pot -- scraper, grubber for grass ʼ; N. khurpo ʻ sickle ʼ, ˚pi ʻ weeding knife ʼ; B. khurpā ʻ spud for grubbing up grass ʼ (X khanítra -- q.v.), Or. khurapa, ˚pā, ˚pi, ˚rupā, ˚pi;; Bi. khurpā ʻ blade of hoe ʼ, ˚pī ʻ small hoe for weeding ʼ; Mth. khurpā, ˚pī ʻ scraper ʼ; H. khurpā m. ʻ weeding knife ʼ, ˚pī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; G. kharpɔ m. ʻ scraper ʼ, ˚pī f. ʻ grubber ʼ (X kāpvũ in karpī f. ʻ weeding tool ʼ); M. khurpẽ n. ʻ curved grubbing hoe ʼ, ˚pī f. ʻ grub -- axe ʼ. -- Deriv. H. khurapnā, ˚rupnā ʻ to scrape up grass ʼ; G. kharapvũ ʻ to cut, dig, remove with a scraper ʼ; M. khurapṇẽ ʻ to grub up ʼ.

3731 kṣurabhāṇḍa n. ʻ razor -- case ʼ Pañcat. [Cf. kṣura- dhāná -- n. ŚBr. -- kṣurá -- , bhāṇḍa -- ]

H. churã̄ṛī f. ʻ razor -- case ʼ.

meḍ 'body' rebus: meḍ 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic). PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'

ranku ‘liquid measure’rebus:ranku ‘tin’

meḍ 'body' rebus: meḍ 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic). PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Field symbol: feeding trough + shor-horned bull: pattar 'trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths' guild' PLUS barad, balad 'ox'

rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

Text B2:khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'

ranku‘antelope’ rebus: ranku‘tin’ + xolā 'fish tail' rebus: kolhe 'smelter',

kol 'working in iron'

ranku‘liquid’ rebus: ranku‘tin’

Text message B3:dula‘two’rebus: dul ‘metal casting’

aḍaren,'lid' Rebus: aduru 'native unsmelted metal' PLUS koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'. Thus, unsmelted native metal workshop.

kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’

Field symbol: duplicated feeding trough + duplicated (antithetical bulls) PLU short-horned bulls: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' Duplication is an orthographic style to signify cire perdue (lost-wax) casting.PLUS pattar 'trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths' guild' PLUS barad, balad 'ox'

rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

Text B10: dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'

baraḍo 'spine, backbone' rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Field symbol: feeding trough + buffalo: pattar 'trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths' guild' PLUS rango 'buffalo' Rebus: rango 'pewter' raṅga3 n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. [Cf. nāga -- 2, vaṅga -- 1]Pk. raṁga -- n. ʻ tin ʼ; P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ (← H.); Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼ, gng. rã̄k; N. rāṅ, rāṅo ʻ tin, solder ʼ, A. B. rāṅ; Or. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; Si. ran̆ga ʻ tin ʼ.(CDIAL 10562)

Text B4:bicha 'scorpion' Rebus: bica 'haetite, sandstone ferrite ore' PLUS मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick) Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Semantic determinative)

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

gaṇḍa 'four' rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'. PLUS kolmo ‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’. Thus, implements forge..

Field symbol: feeding trough + rhinoceros:pattar 'trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths' guild' PLUS : kāṇṭā'rhinoceros. Rebus: kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Gujarati)

Text B5: మెట్ట [ meṭṭa ] or మిట్ట meṭṭa. [Tel.] n. Rising ground, high lying land, uplands. A hill, a rock. ఉన్నతభూమి, మెరక, పర్వతము, దిబ్బ. மேடு mēṭu , n. [T. meṭṭa, M. K. mēḍu.] 1. Height; உயரம். (பிங்.) 2. Eminence, little hill, hillock, ridge, rising ground; சிறுதிடர்.

(பிங்.) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic)

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī

'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'Field symbol B6: feeding trough: elephant: pattar 'feeding trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths, guild' PLUS karibha, ibha‘elephant’ rebus: karba, ib‘iron’ ibbo mjerchant’

Text B6:baṭa 'rimless, wide-mouthed pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS ḍabu 'an iron spoon' (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo 'lump (ingot?).

kolom ‘three’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forgek

kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’ rebus: kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’; Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) kauṭilikḥ कौटिलिकः 1 A hunter.-2 A blacksmith PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'.

Field symbol B14: horned elephant + cobrahood tail + ligatured to thigh and hind legs of bovine: feeding trough: elephant: pattar 'feeding trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths, guild' PLUS karibha, ibha ‘elephant’ rebus: karba, ib ‘iron’ ibbo mjerchant’ PLUS

फडा phaḍā f (फटा S) The hood of Coluber Nága Rebus: phaḍa फड 'manufactory, company, guild, public office' PLUS Hieroglyph: Buttock, back, thigh: (b) Pk. ṭaṁka -- m., °kā -- f. ʻ leg ʼ, S. ṭaṅga f., L. P. ṭaṅg f., Ku. ṭã̄g, N. ṭāṅ; Or. ṭāṅka ʻ leg, thigh ʼ, °ku ʻ thigh, buttock ʼ.2. B. ṭāṅ, ṭeṅri ʻ leg, thigh ʼ; Mth. ṭã̄g, ṭãgri ʻ leg, foot ʼ; Bhoj. ṭāṅ, ṭaṅari ʻ leg ʼ, Aw. lakh. H. ṭã̄g f.; G. ṭã̄g f., °gɔ m. ʻ leg from hip to foot ʼ; M. ṭã̄g f. ʻ leg ʼ.Addenda: 1(b): S.kcch. ṭaṅg(h) f. ʻ leg ʼ, WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ṭāṅg f. (obl. -- a) ʻ leg (from knee to foot) ʼ.(CDIAL 5428)

Hieroglyph: ḍāg, 'waist': *ḍhākka ʻ back, waist ʼ. Wg. ḍakāˊ ʻ waist ʼ; Dm. ḍã̄k, ḍaṅ ʻ back ʼ, Shum. ḍäg, Woṭ. ḍāg, Gaw. ḍáka; Kal. rumb. ḍhak ʻ waist ʼ, urt. ḍhã̄k ʻ back ʼ; Bshk. ḍāk ʻ waist ʼ, d(h)āk ʻ back ʼ AO xviii 233; Tor. ḍāk, ḍāgʻ back ʼ, Mai. ḍāg, ḍā; Phal. ḍōk ʻ waist, back ʼ; Sh. ḍāki̯ f. ʻ back, small of back ʼ, pales. ḍāko; S. ḍhāka f. ʻ hip ʼ, L. ḍhāk; P. ḍhāk f. ʻ side, hip ʼ.(CDIAL 5582)

Rebus: mint, pure gold: Ta. taṅkam pure gold, that which is precious, of great worth. Ma. taṅkam pure gold. /? < Skt. ṭaṅka- a stamped (gold) coin.(DEDR 3013) टङ्क m. a stamped coin Hit.; m. a weight of 4 माषs S3a1rn3gS. i , 19 Vet. iv , 2÷3; m. a sword L.

ṭaṅkaśālā -- , ṭaṅkakaś° f. ʻ mint ʼ lex. [ṭaṅka -- 1, śāˊlā -- ] N. ṭaksāl, °ār, B. ṭāksāl, ṭã̄k°, ṭek°, Bhoj. ṭaksār, H. ṭaksāl, °ār f., G. ṭãksāḷ f., M. ṭã̄ksāl, ṭāk°, ṭãk°, ṭak°. -- Deriv. G. ṭaksāḷī m. ʻ mint -- master ʼ, M. ṭāksāḷyā m.Addenda: ṭaṅkaśālā -- : Brj. ṭaksāḷī, °sārī m. ʻ mint -- master ʼ.(CDIAL 5434) ṭaṅka2 m.n. ʻ spade, hoe, chisel ʼ R. 2. ṭaṅga -- 2 m.n. ʻ sword, spade ʼ lex.1. Pa. ṭaṅka -- m. ʻ stone mason's chisel ʼ; Pk. ṭaṁka -- m. ʻ stone -- chisel, sword ʼ; Woṭ. ṭhõ ʻ axe ʼ; Bshk. ṭhoṅ ʻ battleaxe ʼ, ṭheṅ ʻ small axe ʼ (< *ṭaṅkī); Tor. (Biddulph) "tunger" m. ʻ axe ʼ (ṭ? AO viii 310), Phal. ṭhō˘ṅgif.; K.ṭŏnguru m. ʻ a kind of hoe ʼ; N. (Tarai) ṭã̄gi ʻ adze ʼ; H. ṭã̄kī f. ʻ chisel ʼ; G. ṭã̄k f. ʻ pen nib ʼ; M. ṭã̄k m. ʻ pen nib ʼ, ṭã̄kī f. ʻ chisel ʼ.2. A. ṭāṅgi ʻ stone chisel ʼ; B. ṭāṅg, °gi ʻ spade, axe ʼ; Or. ṭāṅgi ʻ battle -- axe ʼ; Bi. ṭã̄gā, °gī ʻ adze ʼ; Bhoj. ṭāṅī ʻ axe ʼ; H. ṭã̄gī f. ʻ hatchet ʼ. (CDIAL 5427) ṭaṅka1 m.n. ʻ weight of 4 māṣas ʼ ŚārṅgS., ʻ a stamped coin ʼ Hit., °aka -- m. ʻ a silver coin ʼ lex. 2. ṭaṅga -- 1 m.n. ʻ weight of 4 māṣas ʼ lex. 3. *ṭakka -- 1. [Bloch IA 59 ← Tatar tanka (Khot. tanka = kārṣāpaṇa S. Konow Saka Studies 184)]1. Pk. ṭaṁka -- m. ʻ a stamped coin ʼ; N. ṭã̄k ʻ button ʼ (lw. with k); Or. ṭaṅkā ʻ rupee ʼ; H. ṭã̄k m. ʻ a partic. weight ʼ; G. ṭã̄k f. ʻ a partic. weight equivalent to 1/72 ser ʼ; M. ṭã̄k m. ʻ a partic. weight ʼ.2. H. ṭaṅgā m. ʻ a coin worth 2 paisā ʼ.3. Sh. ṭăk m. ʻ button ʼ; S. ṭako m. ʻ two paisā ʼ, pl. ʻ money in general ʼ, ṭrakaku ʻ worth two paisā ʼ, m. ʻ coin of that value ʼ; P. ṭakā m. ʻ a copper coin ʼ; Ku. ṭākā ʻ two paisā ʼ; N. ṭako ʻ money ʼ; A. ṭakā ʻ rupee ʼ, B. ṭākā; Mth. ṭakā, ṭakkā, ṭakwā ʻ money ʼ, Bhoj. ṭākā; H. ṭakā m. ʻ two paisā coin ʼ, G. ṭakɔ m., M. ṭakā m.*uṭṭaṅka -- , *ṣaṭṭaṅka -- , ṭaṅkaśālā -- .Addenda: ṭaṅka -- 1 [H. W. Bailey in letter of 6.11.66: Khot. tanka is not = kārṣāpaṇa -- but is older Khot. ttandäka ʻ so much ʼ < *tantika -- ](CDIAL 5426) *ṭaṅkati2 ʻ chisels ʼ. [ṭaṅka -- 2] Pa. ṭaṅkita -- mañca -- ʻ a stone (i.e. chiselled) platform ʼ; G. ṭã̄kvũ ʻ to chisel ʼ, M. ṭã̄kṇẽ.(CDIAL 5433)

Text B14: dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'

aḍar ‘harrow’ Rebus: aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul ‘casting’.

PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'![]()

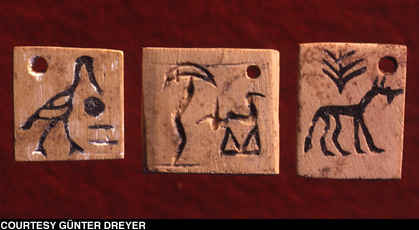

Field symbol: hare + three thorns (bush):Hare in front of the bush: Hieroglyph kharā 'hare' (Oriya) Rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri) PLUS kaṇḍɔ m. ʻ thorn'; kaṇṭa1 m. ʻ thorn ʼ BhP. 2. káṇṭaka -- m. ʻ thorn ʼ ŚBr., ʻ anything pointed ʼ R. 1. Pa. kaṇṭa -- m. ʻ thorn ʼ, Gy. pal. ḳand, Sh. koh. gur. kōṇ m., Ku. gng. kã̄ṇ, A. kāĩṭ (< nom. *kaṇṭē?), Mth. Bhoj. kã̄ṭ, OH. kã̄ṭa. 2. Pa. kaṇṭaka -- m. ʻ thorn, fishbone ʼ; Pk. kaṁṭaya<-> m. ʻ thorn ʼ, Gy. eur. kanro m., SEeur. kai̦o, Dm. kãṭa, Phal. kāṇḍu, kã̄ṛo, Sh. gil. kóṇŭ m., K. konḍu m., S. kaṇḍo m., L. P. kaṇḍā m., WPah. khaś. kaṇṭā m., bhal. kaṇṭo m., jaun. kã̄ḍā, Ku. kāno; N. kã̄ṛo ʻ thorn, afterbirth ʼ (semant. cf.śalyá -- ); B. kã̄ṭā ʻ thorn, fishbone ʼ, Or. kaṇṭā; Aw. lakh. H. kã̄ṭā m.; G. kã̄ṭɔ ʻ thorn, fishbone ʼ; M. kã̄ṭā, kāṭā m. ʻ thorn ʼ, Ko. kāṇṭo, Si. kaṭuva. kaṇṭala -- Addenda: kaṇṭa -- 1. 1. A. also kã̄iṭ; Md. kaři ʻ thorn, bone ʼ.2. káṇṭaka -- : S.kcch. kaṇḍho m. ʻ thorn ʼ; WPah.kṭg. (kc.) kaṇḍɔ m. ʻ thorn, mountain peak ʼ, J. kã̄ḍā m.; Garh. kã̄ḍu ʻ thorn ʼ. (CDIAL 2668) Rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'. Thus, hare in front of thorn/bush signifies: khār खार् 'blacksmith' PLUS kaṇḍa 'implements', i.e. implements from smithy/forge.

Text B7:aya, ayo'fish' rebus: aya'iron'ayas'metal' PLUS adaren'lid' rebus: aduru 'unsmelted metal' PLUS gaNDA 'four' rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'. Thus metal implements of unsmelted metal.

baṭa 'rimless, wide-mouthed pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS ḍabu 'an iron spoon' (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo 'lump (ingot?).

dula ‘two’ rebus: dul ‘metalcasting’

karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles

Rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith' kolmo 'riceplant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’.

ranku ‘antelope’ rebus: ranku ‘tin’ PLUS koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'

kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’Field symbol: feeding trough + short-tailed markhor :pattar 'trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths' guild' PLUS Wkh. merg f. 'ibex' (CDIAL 9885) Tor. miṇḍ 'ram', miṇḍā́l 'markhor' (CDIAL 10310) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet'iron' (Munda.Ho.). Alternative rebus: करडूं karaḍū 'kid' Rebus: karaḍā 'hard alloy'. Rebus 2: karaḍā 'daybook (accounting ledger)(Marathi); Rebus 3: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) PLUS qola 'tail' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter'.

Text B8: kolom‘three’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy,forge’ PLUS gaṇḍa 'four' rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'. PLUS kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’. Thus, implements forge.

baraḍo 'spine, backbone' rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

bhaṭā 'warrior' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī

'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

goṭā ‘round pebble’ Rebus: goṭā 'gold-braid'khoṭa 'ingot, wedge' Rebus: गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe.

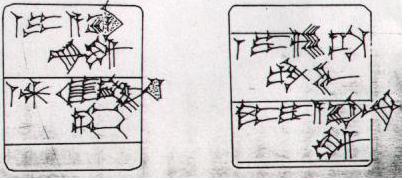

![]() An example of a copper plate inscribed on two sides m2045 which records a descriptive catalogue of work of a goldsmith (guild).

An example of a copper plate inscribed on two sides m2045 which records a descriptive catalogue of work of a goldsmith (guild).![]()

Field symbol: feeding trough + markhor ligatured to body of a bull: pattar 'trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths' guild' PLUS Wkh. merg f. 'ibex' (CDIAL 9885) Tor. miṇḍ 'ram', miṇḍā́l 'markhor' (CDIAL 10310) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) PLUS barad, balad 'ox'

rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

Text B11: మెట్ట [ meṭṭa ] or మిట్ట meṭṭa. [Tel.] n. Rising ground, high lying land, uplands. A hill, a rock. ఉన్నతభూమి, మెరక, పర్వతము, దిబ్బ. மேடு mēṭu , n. [T. meṭṭa, M. K. mēḍu.] 1. Height; உயரம். (பிங்.) 2. Eminence, little hill, hillock, ridge, rising ground; சிறுதிடர். (பிங்.) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'

muṣṭi 'fist' rebus: muṣṭika 'goldsmith'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī

'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'Field symbol: horned tiger: kola 'tiger' rebus: kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pancaloha’; kolhe (iron-smelter; kolhuyo, jackal) kol, kollan-, kollar = blacksmith; kol‘to kill’ (Tamil) PLUS koḍu 'horn' rebus: kod 'artisan's workplace'.

Text B12:kolom‘three’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy,forge’ PLUS gaṇḍa 'four' rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'. PLUS kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’. Thus, implements forge. Text on obverse of B12 together with field symbol: baṭa 'rimless, wide-mouthed pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS ḍabu 'an iron spoon' (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo 'lump (ingot?).

kolom ‘three’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forgek

kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’ rebus: kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’; Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) kauṭilikḥ कौटिलिकः 1 A hunter.-2 A blacksmith PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Text B13:kamaḍha 'crab' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. ḍato = claws of crab (Santali) Rebus: dhātu 'mineral ore'.

.

khaṇḍa 'implements'. karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus: khārखार्'blacksmith' kanka

dhāḷ 'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot' PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'. Thus, ingots and implements.

kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’Field symbol: feeding trough + rhinoceros: pattar 'trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths' guild' PLUS : kāṇṭā'rhinoceros. Rebus: kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Gujarati)

Text B15a:aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'metal (alloy)' PLUS aḍaren 'lid' Rebus: aduru 'unsmelted metal'

aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) PLUS dhāḷ 'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot' . Alternative to the rebus reading of 'lid' hieroglyph in hypertext: ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article' Thus, to signify, excellent, bright, blazing alloy metal article.

dāntā 'tooth, tusk' rebus: dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (ferrite ores, copper ores. PLUS circumscript (lozenge) Split parenthesis: mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting Split parenthesis (lozenge): mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'.PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus, ingot forge.furnace.' PLUS ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda)

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Text B15b:kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus bronze/bell-metal workshop.

ḍhāla f (S through H) The grand flag of an army directing its march and encampments: also the standard or banner of a chieftain rebus: ḍhālako 'ingot'

meḍ 'body' rebus: meḍ 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic). PLUS xolā 'fish tail' rebus: kolhe

'smelter', kol 'working in iron'

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'metal (alloy)' PLUS aḍaren 'lid' Rebus: aduru 'unsmelted metal'

aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) PLUS dhāḷ 'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot' Alternative to the rebus reading of 'lid' hieroglyph in hypertext: ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article' Thus, to signify, excellent, bright, blazing alloy metal article.

dāntā 'tooth, tusk' rebus: dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (ferrite ores, copper ores. PLUS circumscript (lozenge) Split parenthesis: mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting Split parenthesis (lozenge): mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'.PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus, ingot forge.furnace.' PLUS ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda)

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Text B16:Split parenthesis (lozenge): mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'.PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus, ingot forge.

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'metal (alloy)' PLUS aḍaren 'lid' Rebus: aduru 'unsmelted metal'

aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) PLUS dhāḷ 'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot'

baṭa 'rimless, wide-mouthed pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS ḍabu 'an iron spoon' (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo 'lump (ingot?).

dhāḷ 'slanted stroke'rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot' PLUS kolom ‘three’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’

koḍa ‘sluice’; Rebus: koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop (Kuwi)

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

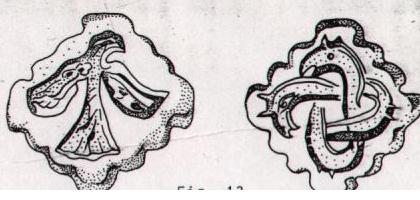

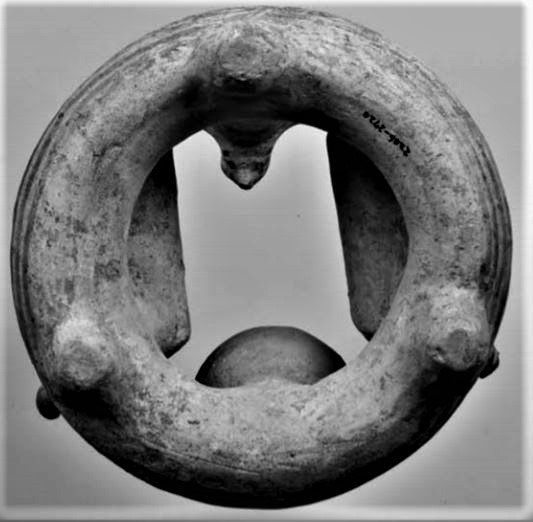

![]() Field symbol: Antithetical turtles: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' (Cire perdue or lost-wax casting) signified by antithesis in orthography.

Field symbol: Antithetical turtles: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' (Cire perdue or lost-wax casting) signified by antithesis in orthography. On this copper tablet, the correct identification of the animal heads will be turtle species comparable toMeiolania, a horned large turtle of New Guinea.See: http://tinyurl.com/jfwgzyo dula'pair, duplicated' rebus: dul'cast metal' PLUS kassa 'turtle' rebus: kãsā 'bell-metal' kamaṭha'turtle' rebus: kãsā kammaṭa'bell-metal coiner, mint, portable furnace'.

Text B17a: dāntā 'tooth, tusk' rebus: dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (ferrite ores, copper ores) PLUS kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin)

khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) PLUS kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa 'bronze' (Telugu)

ranku ‘liquid measure’rebus:ranku ‘tin’ PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'

meḍ 'body' rebus: meḍ 'iron' med

'copper' (Slavic). PLUS koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'.

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Text B17b:dāntā 'tooth, tusk' rebus: dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (ferrite ores, copper ores) kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. ḍhāla f (S through H) The grand flag of an army directing its march and encampments: also the standard or banner of a chieftain rebus: ḍhālako 'ingot'

sal ‘splinter’ rebus: sal ‘workshop’

kolom ‘three’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’

kolmo ‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’ (Semantic determinative).

dāntā 'tooth, tusk' rebus: dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (ferrite ores, copper ores) PLUS kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin)

khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) PLUS kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa 'bronze' (Telugu)

ranku ‘liquid measure’rebus:ranku ‘tin’ PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'

meḍ 'body' rebus: meḍ 'iron' med

'copper' (Slavic). PLUS koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'.

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Text B18:gaṇḍa 'four' rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements' PLUS kolom 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge’

koḍa 'sluice'; Rebus: koḍ'artisan's workshop

loa 'ficus glomerata' Rebus: loha 'copper, iron'. PLUS karNI ‘ears’ rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar'rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe,helmsman'.

Field symbol: horned archer:kamaḍha 'archer, bow' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner

karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus: khārखार्‘blacksmith’dula'two' rebus: dul'metalcasting'

dhāḷ 'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot' PLUS खांडा (p. 116) khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'.

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

goṭā ‘round pebble’ Rebus: goṭā 'gold-braid'khoṭa 'ingot, wedge' Rebus: गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe.

kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) cf. āra-kūṭa, 'brass' Old English ār 'brass, copper, bronze' Old Norse eir 'brass, copper', German ehern 'brassy, bronzen'. kastīra n. ʻ tin ʼ lex.

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar'rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

Category C (12 items), 39 inscriptions

Field symbol: double-axe:kuṭhāra m. ʻ axe ʼ R., °raka -- m. VarBr̥S., °rī -- f. lex., °rikā -- f. Suśr. [kuṭhātaṅka -- m., °kā -- f. lex. Prob. ← Drav. and conn. with √kuṭṭ EWA i 223 with lit.]Pa. kuṭhārī -- f., Pk. kuḍhāra -- m., kuhāḍa -- m., °ḍī -- f. (for ṭh -- r ~ h -- ḍ see piṭhara -- ), S. kuhāṛo m., L. P. kuhāṛā m., °ṛī f., P. kulhāṛā m., °ṛī f., WPah. bhal. kurhāṛi f., Ku. kulyāṛo, gng. kulyāṛ, B. kuṛā̆l, °li, kuṛul, Or. kuṛāla, kurāṛha, °ṛhi, kurhāṛi, kuṛāri; Bi. kulhārī ʻ large axe for squaring logs ʼ; H. kulhāṛā m., °ṛī f. ʻ axe ʼ, G. kuhāṛɔ m., °ṛī f., kuvāṛī f., M. kurhāḍ, °ḍī f., Si. keṇeri Hettiaratchi Indeclinables 6 (connexion, if any, with keṭeri,°ṭēriya ʻ long -- handled axe ʼ is obscure).Addenda: kuṭhāra --: WPah.kṭg. khəṛari, kəṛari f. ʻ axe ʼ.(CDIAL 3244) Rebus: kuThAru 'armourer' कुठारु [p= 289,1] an armourer L.

Text C1 is the same as Text B1:loa 'ficus glomerata' Rebus: loha 'copper, iron' PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metalcasting’ PLUS kamaḍha 'crab' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. ḍato = claws of crab (Santali) Rebus: dhātu 'mineral ore'.

khura ‘hoof’ rebus: ċhúrɔ ‘dagger’ (WPah.) 3727 kṣurá m. ʻ razor ʼ RV., ʻ sharp barb of arrow ʼ R., ˚rī -- f. ʻ knife, dagger ʼ lex., ˚rikā -- f. Rājat. [√kṣur]

ch -- forms, esp. in sense ʻ knife ʼ, are wide -- spread outside dial. bounds: -- Sk. chū˘rī -- f. ʻ knife, dagger ʼ lex., churikā -- f. Kathās., chūr˚ lex., Pa. churikā -- f., NiDoc. kṣura; Pk. chura -- m. ʻ knife, razor, arrow ʼ, ˚rī -- , ˚riā -- f. ʻ knife ʼ; Gy. pal. číri ʻ knife, razor ʼ, arm. čhuri ʻ knife ʼ, eur. čuri f., SEeur. čhurí, Ḍ. čuri f., Kt. c̣urīˊ, c̣uī; Dm. c̣húri ʻ dagger ʼ; Kal. c̣hūˊŕi ʻ knife ʼ; Bshk. c̣hur ʻ dagger, knife ʼ, Tor. c̣hū, Phal. c̣hūr f.; Sh. (Lor.) c̣ūr ʻ small knife ʼ; S. churī f. ʻ knife with a hooked blade ʼ; L. churī f. ʻ knife ʼ, awān. churā m.; P. churā m. ʻ large knife ʼ, ˚rī f. ʻ small do. ʼ, Ku. churo, ˚rī; N. churā ʻ razor ʼ, ˚ri ʻ knife ʼ; A. suri ʻ knife ʼ, B. churi; Or. churā ʻ dagger ʼ, ˚rī ʻ knife ʼ; Bi. chūrā ʻ razor ʼ; Mth. chūr, ˚rā ʻ dagger, razor ʼ, ˚rī ʻ small knife ʼ; Bhoj. Aw. lakh. chūrā ʻ razor ʼ; H. churā m. ʻ dagger, razor ʼ, ˚rī f. ʻ knife ʼ; G. charo m. ʻ large knife ʼ, ˚rī f. ʻ small do. ʼ (Bloch LM 415 wrongly < tsáru -- : churī ← H. or M.), M. surā m., ˚rī f.; Si. siriya ʻ dagger ʼ; -- Woṭ. čir ʻ dagger ʼ ← Psht. ← IA. Buddruss Woṭ 96.

kh -- forms: Pa. khura -- m. ʻ razor ʼ; Pk. khura -- m. ʻ knife, razor ʼ; K. khūru m. ʻ razor ʼ; S. khuryo m. ʻ grass -- scraper, tip of silver at the bottom of a scabbard ʼ; WPah. bhal. khuro m. ʻ razor ʼ; Ku. khuro -- muṇḍo ʻ the shaving of heads ʼ; N. khuro ʻ head of a spear, ferrule of a stick, pin at the top or bottom of a door; A. B. khurʻ razor ʼ (whence A. khurāiba ʻ to shave ʼ), Or. khura; Bi. khūr ʻ razor ʼ, khurā, ˚rī ʻ spiked part of the blade of a chopper which fits into the handle ʼ; H. khurā m. ʻ iron nail to fix ploughshare ʼ; Si. karaya ʻ razor ʼ.

kṣaura -- ; kṣurapra -- , kṣurabhāṇḍa -- ; *prakṣurikā -- ; gōkṣura -- , trikṣura -- .

Addenda: kṣurá -- : WPah.kṭg. ċhúrɔ m. ʻ dagger ʼ, Garh. khur, churī ʻ knife ʼ, A. spel. churī AFD 216.

3728 *kṣuraṇa ʻ scraping ʼ. [√kṣur]

Bi. mag. khurnī ʻ a kind of spade ʼ.

3729 kṣuráti ʻ cuts, scratches, digs ʼ, churáti ʻ cuts off, incises ʼ Dhātup. [√kṣur]

Pa. khurati ʻ scrapes ʼ, Pk. churaï ʻ breaks ʼ; G. chɔrvũ ʻ to dig up with a sharp spade ʼ. -- Ext. with -- ḍ -- : S. khurṛaṇu ʻ to scrape ʼ, khurṛi f. ʻ scrapings ʼ; -- with -- kk -- : S. khurka f. ʻ itching ʼ; L. khurkaṇ ʻ to scratch ʼ, P. khurkṇā; N. khurkanu ʻ to scrape ʼ; -- with -- cc -- : P. khurcṇā ʻ to scrape (a pot) ʼ; G. khurcā m. pl. ʻ scrapings ʼ. -- X trōṭayati: M. khurtuḍṇẽ ʻ to nip off ʼ.

3730 kṣurapra ʻ sharp -- edged like a razor ʼ BhP., m. ʻ sharp- edged arrow ʼ MBh., ʻ sharp -- edged knife ʼ Pañcat., ʻ a sort of hoe ʼ lex. [Cf. *prakṣurikā -- . -- kṣurá+?]

Pa. khurappa -- m. ʻ arrow with a horseshoe head ʼ; Pk. khurappa -- , ˚ruppa -- m. ʻ a kind of arrow, knife for cutting grass ʼ; S. khurpo m. ʻ a pot -- scraper ʼ; P. khurpā m., ˚pī f. ʻ pot -- scraper, grubber for grass ʼ; N. khurpo ʻ sickle ʼ, ˚pi ʻ weeding knife ʼ; B. khurpā ʻ spud for grubbing up grass ʼ (X khanítra -- q.v.), Or. khurapa, ˚pā, ˚pi, ˚rupā, ˚pi;; Bi. khurpā ʻ blade of hoe ʼ, ˚pī ʻ small hoe for weeding ʼ; Mth. khurpā, ˚pī ʻ scraper ʼ; H. khurpā m. ʻ weeding knife ʼ, ˚pī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; G. kharpɔ m. ʻ scraper ʼ, ˚pī f. ʻ grubber ʼ (X kāpvũ in karpī f. ʻ weeding tool ʼ); M. khurpẽ n. ʻ curved grubbing hoe ʼ, ˚pī f. ʻ grub -- axe ʼ. -- Deriv. H. khurapnā, ˚rupnā ʻ to scrape up grass ʼ; G. kharapvũ ʻ to cut, dig, remove with a scraper ʼ; M. khurapṇẽ ʻ to grub up ʼ.

3731 kṣurabhāṇḍa n. ʻ razor -- case ʼ Pañcat. [Cf. kṣura- dhāná -- n. ŚBr. -- kṣurá -- , bhāṇḍa -- ]

H. churã̄ṛī f. ʻ razor -- case ʼ.

meḍ 'body' rebus: meḍ 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic). PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'

ranku ‘liquid measure’rebus:ranku ‘tin’

meḍ 'body' rebus: meḍ 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic). PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khaṇḍa 'implements'

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'.

Field symbol: spoked wheel within a fisted hand:arā 'spokes' Rebus: āra 'brass' eraka 'knave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'moltencast' PLUS muṣṭi 'fist' rebus: muṣṭika 'goldsmith'. Thus, goldsmith working with moltencast brass.

Text C2:ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) aya aDaren,'fish+superscript lid' Rebus: aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal'

baṭa 'rimless, wide-mouthed pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS ḍabu 'an iron spoon' (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo 'lump (ingot?).

dula‘two’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’

karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus: khār खार्'blacksmith' PLUS dhāḷ 'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot'. Thus, ingots (worked on by) blacksmiths.

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus, blacksmiths working in forge.

ranku‘antelope’ rebus: ranku‘tin’ + xolā 'fish tail' rebus: kolhe 'smelter',

kol 'working in iron'

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus, smelters working in smithy.Field symbol: rim-of-jar with inlaid 3+3 short strokes + pair of 'short tails':ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) aya aDaren,'fish+superscript lid' Rebus: aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal' PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’ Alternative rebus reading: ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article' Thus, to signify, excellent, bright, blazing alloy metal article. PLUS dula 'duplicated' rebus: dul 'metal casting'. Thus, cast metal blazing articles.

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar'rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'.

PLUS sal ‘splinter’ rebus: sal ‘workshop, school’ PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’ PLUS xolā 'fish tail' rebus: kolhe 'smelter', kol 'working in iron'

Text C3:ayo ‘fish’ rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda)

bicha 'scorpion' Rebus: bica 'haetite, sandstone ferrite ore' PLUS मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick) Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Semantic determinative)

dāṭu 'cross' rebus: dhatu = mineral (Santali) Hindi. dhāṭnā 'to send out, pour out, cast (metal)' (CDIAL 6771)

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar'rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'.

PLUS ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin'. Thus, tin metalcasting.

PLUS ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin'. Thus, tin metalcasting. ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin' PLUS

ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin' PLUS

PLUS dhangra 'bull' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'

PLUS dhangra 'bull' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' m0480a

m0480a

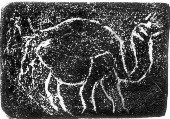

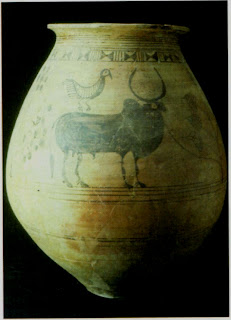

9351; Nippur; ca. 13th cent. BC; white stone; zebu bull and two pictograms. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'. goTa 'round object' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'; bartI 'partridge/quail' (Khotanese); bharati id. (Samskritam) Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, the message is: kuThi poLa khoTa bharata smelter for magnetite, alloy ingot (copper, pewter, tin alloy).

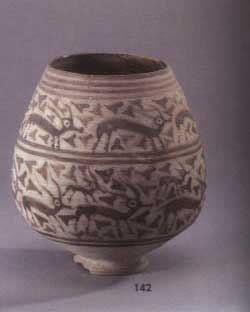

9351; Nippur; ca. 13th cent. BC; white stone; zebu bull and two pictograms. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'. goTa 'round object' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'; bartI 'partridge/quail' (Khotanese); bharati id. (Samskritam) Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, the message is: kuThi poLa khoTa bharata smelter for magnetite, alloy ingot (copper, pewter, tin alloy). 9851; Louvre Museum; Luristan; unglazed, gray steatite; short-horned bull and 4 pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; PLUS meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' thus, the pair of 'bodies' signify: iron cast metal.

9851; Louvre Museum; Luristan; unglazed, gray steatite; short-horned bull and 4 pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; PLUS meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' thus, the pair of 'bodies' signify: iron cast metal.

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription.

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription.  Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron'

Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron' 3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'. 9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'

9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze' 9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'.

9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim)

Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim) Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead' 9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'

9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

This is the image of the first seal and a seal impression which has stimulated the spectacular discoveries of the roots of Hindu Civilization along the banks of River Sarasvati adored in 72 r̥ca-s in the R̥

This is the image of the first seal and a seal impression which has stimulated the spectacular discoveries of the roots of Hindu Civilization along the banks of River Sarasvati adored in 72 r̥ca-s in the R̥

"

"

eruvai 'eagle' rebus: eruvai 'copper'

eruvai 'eagle' rebus: eruvai 'copper'

Article Info

Article Info

CC Lamberg-Karlovsky and DT Potts , 2001, Excavations at Tepe Yahya, Iran, 1967-1975: the third millennium, CC Lamberg-Karlovsky, DT Potts with contributions by Holly Pittman and Philip L.Kohl, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

CC Lamberg-Karlovsky and DT Potts , 2001, Excavations at Tepe Yahya, Iran, 1967-1975: the third millennium, CC Lamberg-Karlovsky, DT Potts with contributions by Holly Pittman and Philip L.Kohl, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

![clip_image057[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0574-thumb.jpg?w=80&h=68)

For a color image of 'archer' see m1540A image of copper tablet, Mohenjodaro.

For a color image of 'archer' see m1540A image of copper tablet, Mohenjodaro.

Figure 2. Mis-correction of a mis-spelled word

Figure 2. Mis-correction of a mis-spelled word

Location of Nausharo in relation to other sites of Sarasvati (Indus) Civilization

Location of Nausharo in relation to other sites of Sarasvati (Indus) Civilization

Crucible steel button.

Crucible steel button.

Zebu, bos indicus PLUS black drongo bird (perched on the back of the bull) This bird is called పసులపోలిగాడు

Zebu, bos indicus PLUS black drongo bird (perched on the back of the bull) This bird is called పసులపోలిగాడు :max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/rao4HR-56a021705f9b58eba4af1a4b.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/rao1hr-56a0216f5f9b58eba4af1a42.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/rao3HR-56a0216f5f9b58eba4af1a48.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/rao5HR-56a0216f5f9b58eba4af1a3f.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/rao2HR-56a0216f5f9b58eba4af1a45.jpg)

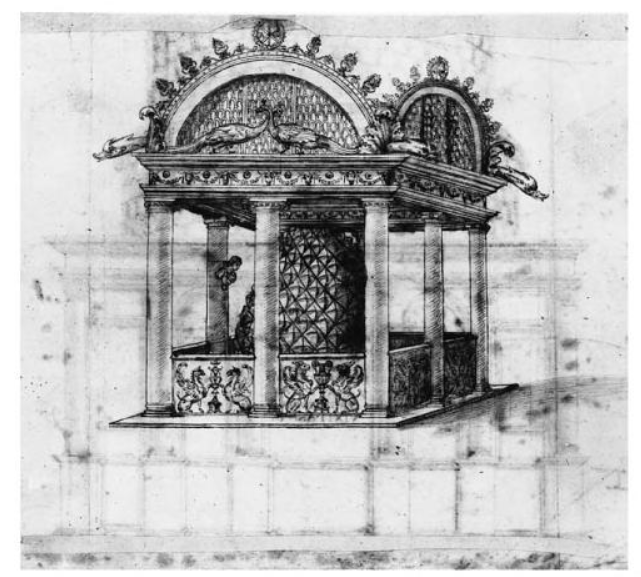

Altar, offered by Tukulti-Ninurta I, 1243-1208 BCE, in prayer before two deities carrying wooden standards, Assyria, Bronze

Altar, offered by Tukulti-Ninurta I, 1243-1208 BCE, in prayer before two deities carrying wooden standards, Assyria, Bronze

Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BCE.

Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BCE.

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Late Harappan Period large burial urn with ledged rim for holding a bowl-shaped lid. The painted panel around the shoulder of the vessel depicts flying peacocks with sun or star motifs and wavy lines that may represent water. Cemetery H period, after 1900 BCE. These new pottery styles seem to have been introduced at the very end of the Harappan Period. The transitional phase (Period 4) at Harappa has begun to yield richly diverse material remains suggesting a period of considerable dynamism as socio-cultural traditions became realigned.

Late Harappan Period large burial urn with ledged rim for holding a bowl-shaped lid. The painted panel around the shoulder of the vessel depicts flying peacocks with sun or star motifs and wavy lines that may represent water. Cemetery H period, after 1900 BCE. These new pottery styles seem to have been introduced at the very end of the Harappan Period. The transitional phase (Period 4) at Harappa has begun to yield richly diverse material remains suggesting a period of considerable dynamism as socio-cultural traditions became realigned.

Water holes in the pine cone can be seen. The bronze piece was part of a water-fountain.

Water holes in the pine cone can be seen. The bronze piece was part of a water-fountain.

Fontana della Pigna(fountain of the pine cone) in piazza San Marco. This fountain, very close to theAltare della Patria, celebrates the huge bronze sculpture called Pignone(kept in the Vatican museums today).

Fontana della Pigna(fountain of the pine cone) in piazza San Marco. This fountain, very close to theAltare della Patria, celebrates the huge bronze sculpture called Pignone(kept in the Vatican museums today).

Bronze Peacock in Hadrian museum, Vatican. See:

Bronze Peacock in Hadrian museum, Vatican. See:

Logo of the Rione.

Logo of the Rione.

Map of the archaeological complex: Largo di Torre Argentina, Rome, Italy

Map of the archaeological complex: Largo di Torre Argentina, Rome, Italy

_-2.jpg)

This temple was built for the Egyptian merchants. It was located on the Commercial Agora near the western gate. There is also another entrance into the temple from the south-west corner of the Agora through stairs.

This temple was built for the Egyptian merchants. It was located on the Commercial Agora near the western gate. There is also another entrance into the temple from the south-west corner of the Agora through stairs.

A pair of eagle-headed Annunak flanking a staff capped with a pine-cone.

A pair of eagle-headed Annunak flanking a staff capped with a pine-cone. Marduk, winged, holding the pine-cone. Bracelet has safflower hieroglyph. Annunaki, Sumerian.

Marduk, winged, holding the pine-cone. Bracelet has safflower hieroglyph. Annunaki, Sumerian.

Technical information

Technical information

āmalaka, Phyllanthus emblica.

āmalaka, Phyllanthus emblica.