Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/h2pzo85

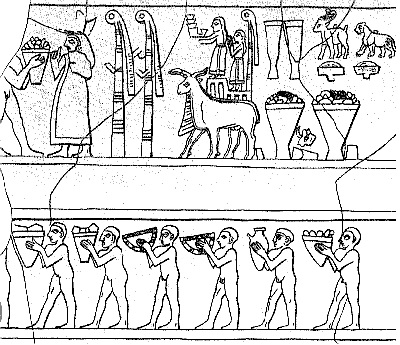

![]()

Meluhha and Bronze Age revolution

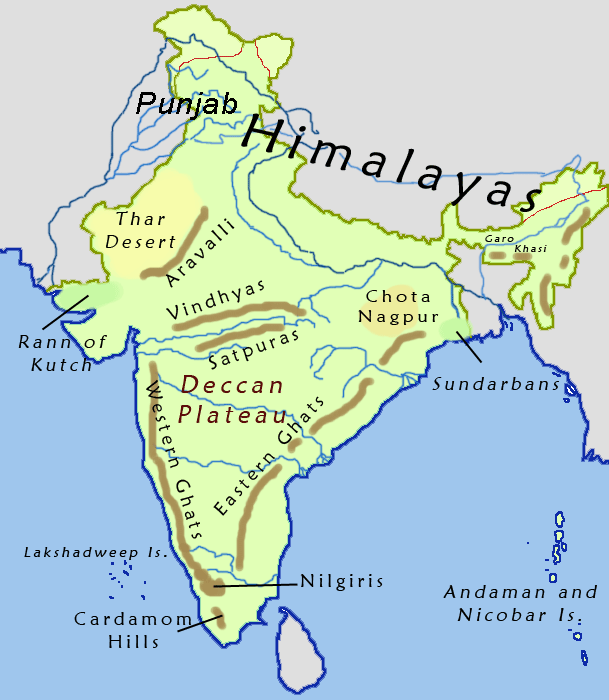

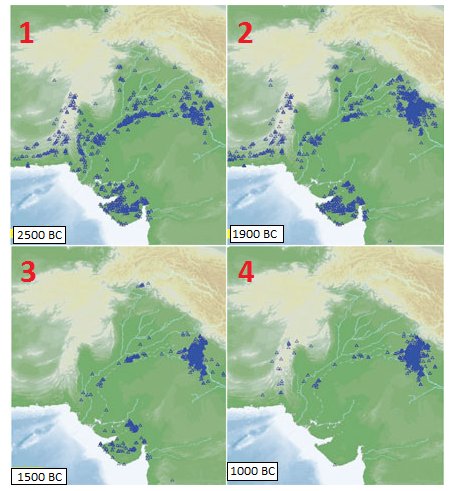

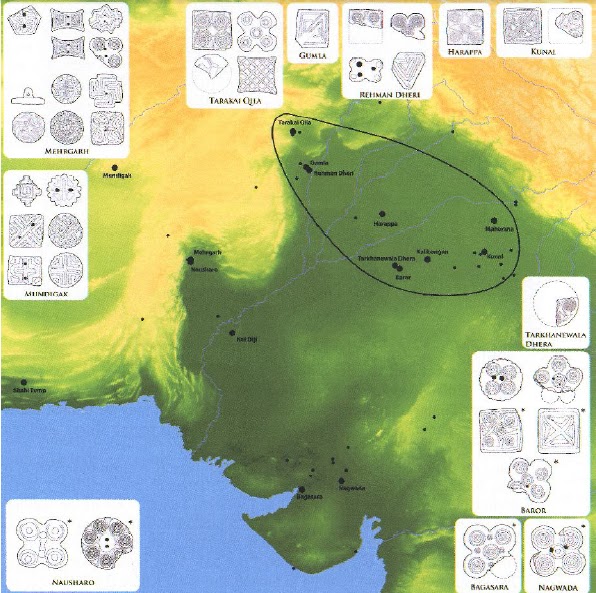

Indus Script evidence validates maritime trade of Meluhha (Sarasvati civilization) with Dilmun from 2500 BCE.

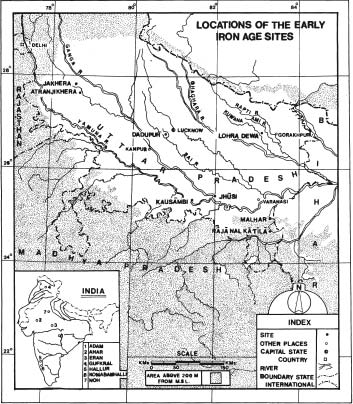

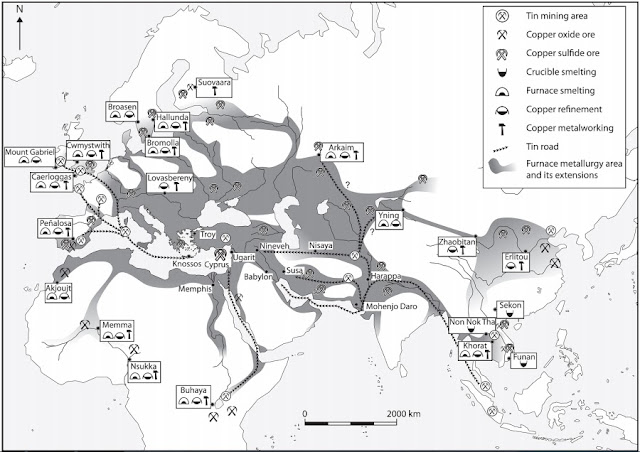

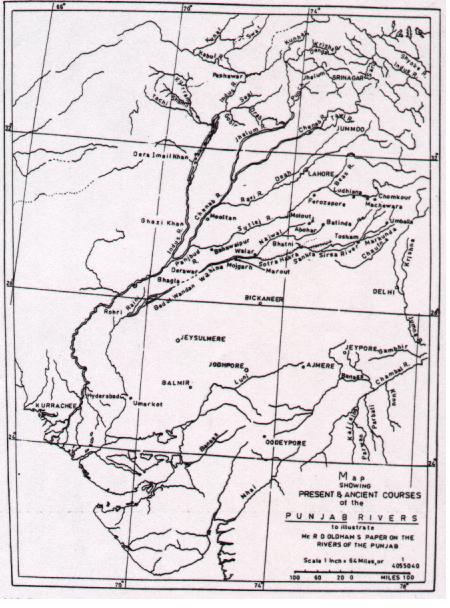

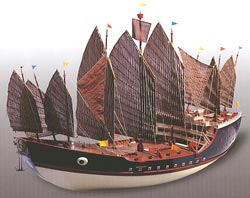

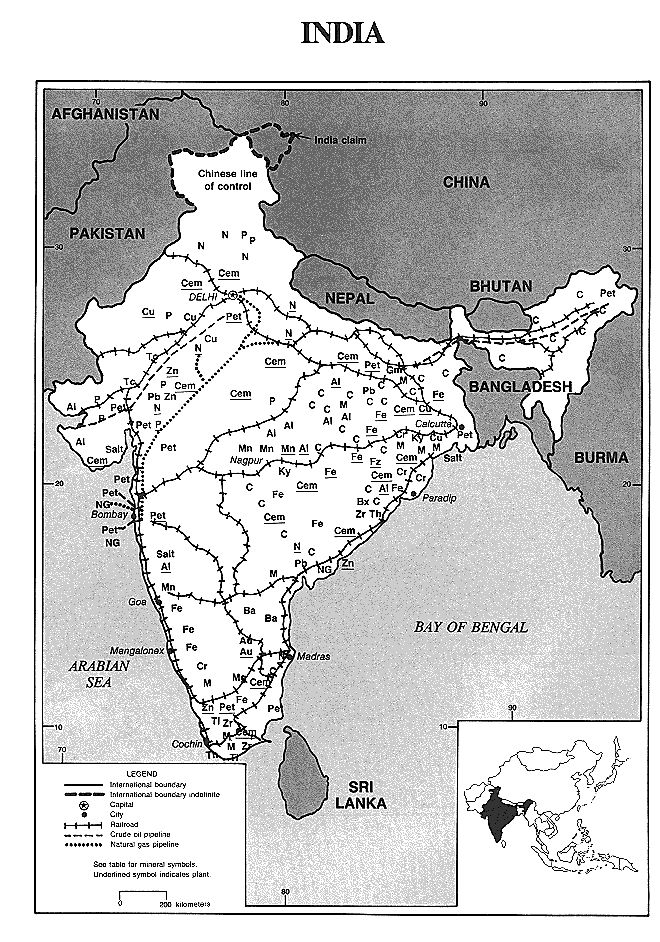

A Maritime tin route from Hanoi to Haifa has been posited to transport tin which was a critical component to alloy with copper to sustain the Bronze Age revolution. On this route which predated Silk Road by two millennia, the Persian Gulf (Straits of Hormuz), together with the Straits of Malacca, was the critical maritime link. Archaeological reports on sites along the Persian Gulf have cumulatively evidenced the trade and cultural contacts Meluhha (Sarasvati civilization) merchants and artisans (some with settlements in Ancient Near East) had with Ancient Near East and Ancient Far East as active participants in the revolution. The presence of Munda in Austro-asiatic speaker areas of Ancient Far East is well-attested by Austro-asiatic etyma also present in glosses of Indian sprachbund (pace FBJ Kuiper on Munda words in Samskrtam).

![]()

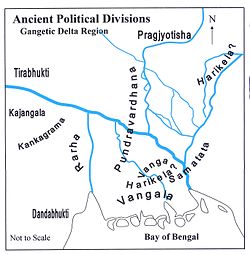

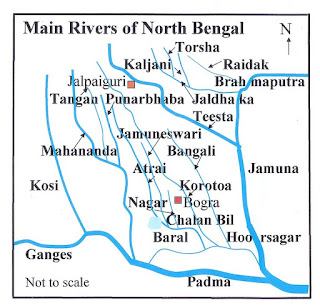

Map of Bronze Age sites of eastern India and neighbouring areas: 1. Koldihwa; 2.Khairdih; 3. Chirand; 4. Mahisadal; 5. Pandu Rajar Dhibi; 6.Mehrgarh; 7. Harappa;8. Mohenjo-daro; 9.Ahar; 10. Kayatha; 11.Navdatoli; 12.Inamgaon; 13. Non PaWai; 14. Nong Nor;15. Ban Na Di andBan Chiang; 16. NonNok Tha; 17. Thanh Den; 18. Shizhaishan; 19. Ban Don Ta Phet [After Fig. 8.1 in: Charles Higham, 1996, The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia, Cambridge University Press].

![]()

Austroasiatic languages map (in German) from H.-J. Pinnow's Versuch einer historischen Lautlehre der Kharia-Sprache, 1958: map

The Gundestrup cauldron and Pillar of Boatmen are evidence of the Meluhhan contact areas in the Ancient NEar East. So are the hieroglyphs of frog, peacock, elephant, antelopes, heron on Dong Son bronze drums evidenc of the Meluhhan contact areas in the Tin Belt of the Globe in Ancient Far East.

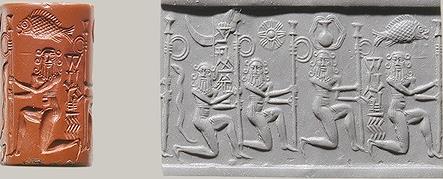

Glyptic art of the Seals from Persian Gulf are a combination of Mesopotamian syles of cylinder seals combined with Indus Script hieroglyphs. Meluhhans had a flourishing tradw with Sumer ca. 2350 BCE. The inscriptions of Persian Gulf cylinder seald and also Dilmun-type stamp seals provide conclusive evidence for the presence of Meluhha merchants/artisans in the Persian Gulf and interacting with Ur and Susa. The trade transactions with Susa are attested by a Susa pot with the cargo of metal implements, tools, weapons. The decipherment of Indus Script hieroglyphs on the Susa pot as metalwork catalogues are presented in:See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/06/antithetical-antelopes-indus-script.html The hieroglyphs on the Kuwait Museum gold disc can be read rebus:1. A pair of tabernae montana flowers tagara 'tabernae montana' flower; rebus: tagara 'tin'

2. A pair of rams tagara 'ram'; rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian) Next to one ram: kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter' Alternative: kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

3. Ficus religiosa leaves on a tree branch (5) loa 'ficus leaf'; rebus: loh 'metal'. kol in Tamil means pancaloha'alloy of five metals'. PLUS flanking pair of lotus flowers: tAmarasa 'lotus' Rebus: tAmra 'copper' dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' thus, denoting copper castings.

4. A pair of bulls tethered to the tree branch: barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' (Marathi) PLUS kola 'man' Rebus: kolhe 'smelter' kur.i 'woman' Rebus: kol 'working in iron' Alternative: ḍhangar 'bull'; rebus ḍhangar 'blacksmith' poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'.

Two persons touch the two bulls: meḍ ‘body’ (Mu.) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) Thus, the hieroglyph composition denotes ironsmiths.

5. A pair of antelopes looking back: krammara 'look back'; rebus: kamar 'smith' (Santali); tagara 'antelope'; rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian) Alternative: melh, mr..eka 'goat' (Brahui. Telugu) Rebus: milakkhu 'copper' (Pali), mleccha-mukha 'copper' (Samskritam)

6. A pair of antelopes mē̃ḍh 'antelope, ram'; rebus: mē̃ḍ 'iron' (Mu.)

7. A pair of combs kāṅga 'comb' Rebus: kanga 'brazier, fireplace'

Phal. kāṅga ʻ combing ʼ in ṣiṣ k° dūm ʻI comb my hairʼ khyḗṅgia, kēṅgī f.;

kaṅghā m. ʻ large comb (Punjabi) káṅkata m. ʻ comb ʼ AV., n. lex., °tī -- , °tikã -- f. lex. 2. *kaṅkaṭa -- 2. 3. *kaṅkaśa -- . [Of doubtful IE. origin WP i 335, EWA i 137: aberrant -- uta -- as well as -- aśa -- replacing -- ata -- in MIA. and NIA.]1. Pk. kaṁkaya -- m. ʻ comb ʼ, kaṁkaya -- , °kaï -- m. ʻ name of a tree ʼ; Gy. eur. kangli f.; Wg. kuṇi -- přũ ʻ man's comb ʼ (for kuṇi -- cf. kuṇälík beside kuṅälíks.v. kr̥muka -- ; -- přũ see prapavaṇa -- ); Bshk. kēṅg ʻ comb ʼ, Gaw. khēṅgīˊ, Sv. khḗṅgiā, Tor. kyäṅg ʻ comb ʼ (Dard. forms, esp. Gaw., Sv., Phal. but not Sh., prob. ← L. P. type < *kaṅgahiā -- , see 3 below); Sh. kōṅyi̯ f. (→ Ḍ. k*lṅi f.), gil. (Lor.) kōĩ f. ʻ man's comb ʼ, kōũ m. ʻ woman's comb ʼ, pales. kōgō m. ʻ comb ʼ; K. kanguwu m. ʻ man's comb ʼ, kangañ f. ʻ woman's ʼ; WPah. bhad. kãˊkei ʻ a comb -- like fern ʼ, bhal. kãkei f. ʻ comb, plant with comb -- like leaves ʼ; N. kāṅiyo, kāĩyo ʻ comb ʼ, A. kã̄kai, B. kã̄kui; Or. kaṅkāi, kaṅkuā ʻ comb ʼ, kakuā ʻ ladder -- like bier for carrying corpse to the burning -- ghat ʼ; Bi. kakwā ʻ comb ʼ, kakahā, °hī, Mth. kakwā, Aw. lakh. kakawā, Bhoj. kakahī f.; H. kakaiyā ʻ shaped like a comb (of a brick) ʼ; G. (non -- Aryan tribes of Dharampur)kākhāī f. ʻ comb ʼ; M. kaṅkvā m. ʻ comb ʼ, kã̄kaī f. ʻ a partic. shell fish and its shell ʼ; -- S. kaṅgu m. ʻ a partic. kind of small fish ʼ < *kaṅkuta -- ? -- Ext. with --l -- in Ku. kã̄gilo, kāĩlo ʻ comb ʼ.2. G. (Soraṭh) kã̄gaṛ m. ʻ a weaver's instrument ʼ?3. L. kaṅghī f. ʻ comb, a fish of the perch family ʼ, awāṇ. kaghī ʻ comb ʼ; P. kaṅghā m. ʻ large comb ʼ, °ghī f. ʻ small comb for men, large one for women ʼ (→ H. kaṅghā m. ʻ man's comb ʼ, °gahī, °ghī f. ʻ woman's ʼ, kaṅghuā m. ʻ rake or harrow ʼ; Bi. kãgahī ʻ comb ʼ, Or. kaṅgei, M. kaṅgvā); -- G. kã̄gsī f. ʻ comb ʼ, with metath. kã̄sko m., °kī f.; WPah. khaś. kāgśī, śeu. kāśkī ʻ a comblike fern ʼ or < *kaṅkataśikha -- .WPah.kṭg. kaṅgi f. ʻ comb ʼ; J. kāṅgṛu m. ʻ small comb ʼ.(CDIAL 2598)

Rebus: large furnace, fireplace: kang कंग् । आवसथ्यो &1;ग्निः m. the fire-receptacle or fire-place, kept burning in former times in the courtyard of a Kāshmīrī house for the benefit of guests, etc., and distinct from the three religious domestic fires of a Hindū; (at the present day) a fire-place or brazier lit in the open air on mountain sides, etc., for the sake of warmth or for keeping off wild beasts. nāra-kang, a fire-receptacle; hence, met. a shower of sparks (falling on a person) (Rām. 182). kan:gar `portable furnace' (Kashmiri)Cf. kã̄gürü, which is the fem. of this word in a dim. sense (Gr.Gr. 33, 7). kã̄gürü काँग्् or

kã̄gürü काँग or kã̄gar काँग््र्् । हसब्तिका f. (sg. dat. kã̄grĕ काँग्र्य or kã̄garĕ काँगर्य, abl. kã̄gri काँग्रि), the portable brazier, or kāngrī, much used in Kashmīr (K.Pr. kángár, 129, 131, 178; káṅgrí, 5, 128, 129). For particulars see El. s.v. kángri; L. 7, 25, kangar;and K.Pr. 129. The word is a fem. dim. of kang, q.v. (Gr.Gr. 37). kã̄gri-khŏphürükã̄gri-khŏphürü काँग्रि-ख्वफ््&above;रू&below; । भग्ना काष्ठाङ्गारिका f. a worn-out brazier. -khôru -खोरु&below; । काष्ठाङ्गारिका<-> र्धभागः m. the outer half (made of woven twigs) of a brazier, remaining after the inner earthenware bowl has been broken or removed; see khôru. -kŏnḍolu -क्वंड । हसन्तिकापात्रम् m. the circular earthenware bowl of a brazier, which contains the burning fuel. -köñü -का&above;ञू&below; । हसन्तिकालता f. the covering of woven twigs outside the earthenware bowl of a brazier.

It is an archaeometallurgical challenge to trace the Maritime Tin Route from the tin belt of the world on Mekong River delta in the Far East and trace the contributions made by seafaring merchants of Meluhha in reaching the tin mineral resource to sustain the Tin-Bronze Age which was a revolution unleashed ca. 5th millennium BCE. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/indus-script-corpora-as-catalogus.html

8. A pair of fishes ayo 'fish' (Mu.); rebus: ayo 'metal, iron' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Sanskrit)

9.A pair of buffaloes tethered to a post-standard kāṛā ‘buffalo’ கண்டி kaṇṭi buffalo bull (Tamil); rebus: kaṇḍ 'stone ore'; kāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar, consecrated fire’.

10. A pair of birds Rebus 1: kōḍi. [Tel.] n. A fowl, a bird. (Telugu) Rebus: khōṭ ‘alloyed ingots’. Rebus 2: kol ‘the name of a bird, the Indian cuckoo’ (Santali) kol 'iron, smithy, forge'. Rebus 3: baṭa = quail (Santali) Rebus: baṭa = furnace, kiln (Santali) bhrāṣṭra = furnace (Skt.) baṭa = a kind of iron (G.) bhaṭa ‘furnace’ (Gujarati)

11. The buffaloes, birds flank a post-standard with curved horns on top of a stylized 'eye' PLUS 'eyebrows' with one-horn on either side of two faces

![]() mũh ‘face’; rebus: mũh ‘ingot’ (Mu.)

mũh ‘face’; rebus: mũh ‘ingot’ (Mu.)

ṭhaṭera ‘buffalo horns’. ṭhaṭerā ‘brass worker’ (Punjabi)

Pe. kaṇga (pl. -ŋ, kaṇku) eye. Rebus: kanga ' large portable brazier, fire-place' (Kashmiri).

Thus the stylized standard is read rebus: Hieroglyph components:kanga + ṭhaṭerā 'one eye + buffalo horn' Rebus: kanga 'large portable barzier' (Kashmiri) + ṭhaṭerā ‘brass worker’ (Punjabi)

Ta. kaṇ eye, aperture, orifice, star of a peacock's tail. Ma. kaṇ, kaṇṇu eye, nipple, star in peacock's tail, bud. Ko. kaṇ eye. To. koṇ eye, loop in string.Ka. kaṇ eye, small hole, orifice. Koḍ. kaṇṇï id. Tu. kaṇṇů eye, nipple, star in peacock's feather, rent, tear. Te. kanu, kannu eye, small hole, orifice, mesh of net, eye in peacock's feather. Kol. kan (pl. kanḍl) eye, small hole in ground, cave. Nk. kan (pl. kanḍḷ) eye, spot in peacock's tail. Nk. (Ch.) kan (pl. -l) eye. Pa.(S. only) kan (pl. kanul) eye. Ga. (Oll.) kaṇ (pl. kaṇkul) id.; kaṇul maṭṭa eyebrow; kaṇa (pl. kaṇul) hole; (S.) kanu (pl. kankul) eye. Go. (Tr.) kan (pl.kank) id.; (A.) kaṛ (pl. kaṛk) id. Konḍa kaṇ id. Pe. kaṇga (pl. -ŋ, kaṇku) id. Manḍ. kan (pl. -ke) id. Kui kanu (pl. kan-ga), (K.) kanu (pl. kaṛka) id. Kuwi(F.) kannū (pl. kar&nangle;ka), (S.) kannu (pl. kanka), (Su. P. Isr.) kanu (pl. kaṇka) id. Kur. xann eye, eye of tuber; xannērnā (of newly born babies or animals) to begin to see, have the use of one's eyesight (for ērnā, see 903). Malt. qanu eye. Br. xan id., bud. (DEDR 1159) kāṇá ʻ one -- eyed ʼ RV. Pa. Pk. kāṇa -- ʻ blind of one eye, blind ʼ; Ash. kã̄ṛa, °ṛī f. ʻ blind ʼ, Kt. kãŕ, Wg. kŕãmacrdotdot;, Pr. k&schwatildemacr;, Tir. kāˊna, Kho. kāṇu NTS ii 260,kánu BelvalkarVol 91; K. kônu ʻ one -- eyed ʼ, S. kāṇo, L. P. kāṇã̄; WPah. rudh. śeu. kāṇā ʻ blind ʼ; Ku. kāṇo, gng. kã̄&rtodtilde; ʻ blind of one eye ʼ, N. kānu;A. kanā ʻ blind ʼ; B. kāṇā ʻ one -- eyed, blind ʼ; Or. kaṇā, f. kāṇī ʻ one -- eyed ʼ, Mth. kān, °nā, kanahā, Bhoj. kān, f. °ni, kanwā m. ʻ one -- eyed man ʼ, H. kān,°nā, G. kāṇũ; M. kāṇā ʻ one -- eyed, squint -- eyed ʼ; Si. kaṇa ʻ one -- eyed, blind ʼ. -- Pk. kāṇa -- ʻ full of holes ʼ, G. kāṇũ ʻ full of holes ʼ, n. ʻ hole ʼ (< ʻ empty eyehole ʼ? Cf. ã̄dhḷũ n. ʻ hole ʼ < andhala -- ).S.kcch. kāṇī f.adj. ʻ one -- eyed ʼ; WPah.kṭg. kaṇɔ ʻ blind in one eye ʼ, J. kāṇā; Md. kanu ʻ blind ʼ.(CDIAL 3019) Ko. kāṇso ʻ squint -- eyed ʼ.(Konkani)

Paš. ainċ -- gánik ʻ eyelid ʼ(CDIAL 3999) Phonetic reinforcement of the gloss: Pe. kaṇga (pl. -ŋ, kaṇku) eye.

See also: nimišta kanag 'to write' (SBal): *nipēśayati ʻ writes ʼ. [√piś] Very doubtful: Kal.rumb. Kho. nivḗš -- ʻ to write ʼ more prob. ← EPers. Morgenstierne BSOS viii 659. <-> Ir. pres. st. *nipaiš -- (for *nipais -- after past *nipišta -- ) in Yid. nuviš -- , Mj. nuvuš -- , Sang. Wkh. nəviš -- ; -- Aś. nipista<-> ← Ir. *nipista -- (for *nipišta -- after pres. *nipais -- ) in SBal. novīsta or nimišta kanag ʻ to write ʼ.(CDIAL 7220)

Alternative: dol ‘eye’; Rebus: dul ‘to cast metal in a mould’ (Santali)Alternative: kandi ‘hole, opening’ (Ka.)[Note the eye shown as a dotted circle on many Dilmun seals.]; kan ‘eye’ (Ka.); rebus: kandi (pl. –l) necklace, beads (Pa.);kaṇḍ 'stone ore' Alternative: kã̄gsī f. ʻcombʼ (Gujarati); rebus 1: kangar ‘portable furnace’ (Kashmiri); rebus 2: kamsa 'bronze'.

khuṇḍ ʻtethering peg or post' (Western Pahari) Rebus: kūṭa ‘workshop’; kuṭi= smelter furnace (Santali); Rebus 2: kuṇḍ 'fire-altar'

Why are animals shown in pairs?

dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); rebus: dul ‘cast metal’ (Mu.)

Thus, all the hieroglyphs on the gold disc can be read as Indus writing related to one bronze-age artifact category: metalware catalog entries.

![]() kondh ‘young bull’. kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’. sangaDa 'lathe, brazier' rebus: sangAta 'collection' (of metalwork) koTiya 'rings on neck' rebus: kotiya 'baghlah dhow, cargo boat'. कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copperand 2 parts tin) dATu ‘cross’ rebus: dhAtu ‘mineral’ gaNDa ‘four’ rebus: kaNDa ‘implements’ dula ‘two’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’ ayo, aya ‘fish’ rebus: aya ‘iron’ ayas ‘metal’ aya ‘fish’ rebus: ayas ‘metal’ PLUS adaren ‘lid’ rebus: aduru ‘unsmelted metal’ kolmo ‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’ muh ‘ingot’ kolom ‘three’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’ dula ‘two’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’ ranku ‘liquid measure’ rebus: ranku ‘tin’ kolmo ‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’ karNaka, kanka ‘rim of jar’ rebus: karNI ‘supercargo, engraver, account’.

kondh ‘young bull’. kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’. sangaDa 'lathe, brazier' rebus: sangAta 'collection' (of metalwork) koTiya 'rings on neck' rebus: kotiya 'baghlah dhow, cargo boat'. कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copperand 2 parts tin) dATu ‘cross’ rebus: dhAtu ‘mineral’ gaNDa ‘four’ rebus: kaNDa ‘implements’ dula ‘two’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’ ayo, aya ‘fish’ rebus: aya ‘iron’ ayas ‘metal’ aya ‘fish’ rebus: ayas ‘metal’ PLUS adaren ‘lid’ rebus: aduru ‘unsmelted metal’ kolmo ‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’ muh ‘ingot’ kolom ‘three’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’ dula ‘two’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’ ranku ‘liquid measure’ rebus: ranku ‘tin’ kolmo ‘rice plant’ rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’ karNaka, kanka ‘rim of jar’ rebus: karNI ‘supercargo, engraver, account’.

See: https://www.academia.edu/1898205/Potts_2010_-_Cylinder_seals_and_their_use_in_the_Arabian_Peninsula_AAE_21_ DT Potts, 2010 Cylnder seals and their use in Arabian Peninsula. After presenting the following figures of cylinder seals, DT Potts concludes:

"In conclusion, the number of seals discovered in eastern Arabia comes nowhere near the thousands known further north in the cuneiform-using heartland of the ancient Near East. Nevertheless, the apparent dearth of cylinder seals in the region is itself a relative estimation. Compared with the Indus Valley, eastern Iran, Central Asia and the Bronze Age Caucasus, the numbers are not insignificant. There is, however, a very clear fall-off in seal numbers...

![]()

![]()

![]()

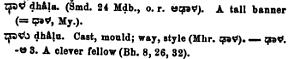

koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer, warehouse' . मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Munda)

मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Munda)

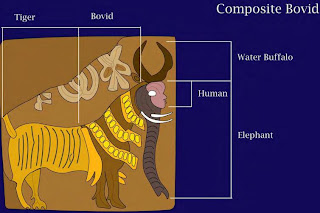

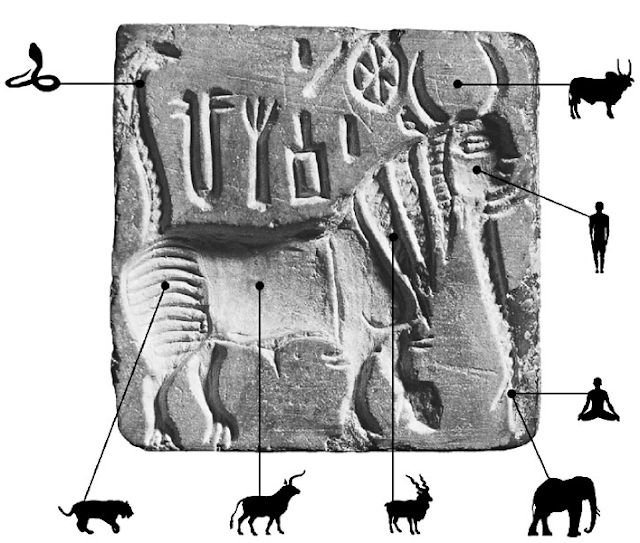

kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' mlekh 'goat' rebus:milakkhu 'copper' barad, balad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'

Fig. 6c offering table with hooves grasped/touched by bull-men or humans

Fig. 6e table grasped/touched by monkeys

Fig. 6a-e symbols/objects apparently placed on the table

Fig. 6a,c table apparently placed on a ‘podium’

कर्णक kárṇaka, kannā 'legs spread', 'rim of jar', 'pericarp of lotus' karaṇī 'scribe, supercargo', kañi-āra 'helmsman'.kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware'

![]() Fig. 5a-f bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch; Fig 5c, d bull-man standing ‘above’ an animal; Fig. 5a-f : bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch

Fig. 5a-f bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch; Fig 5c, d bull-man standing ‘above’ an animal; Fig. 5a-f : bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer, warehouse' . मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.M

करडूं or करडें (p. 137) [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं) A kid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) khaNDa 'divisions' Rebus: khANDa 'implements'

![]() Fig. 4a b

Fig. 4a bull-man standing on a hatched podium Fig. 4b, f bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch; Fig. 4a, c-d bull-man grasping an animal; Fig. 4b : bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch

karaDi 'safflower' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' (Marathi); khaNDa 'divisions' Rebus: khANDa 'implements' koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer, warehouse' . मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.M

![]() Fig. 3a Features: god with a naked or garbed attendant behind or before; god holding/touching a crescent-standard; bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch Fig. 3b bull-man grasped/touched by a naked male figure Fig. 3b-f bull-man grasping an animal; Fig. 3d bull-man standing ‘above’ an animal; Fig. 3a : bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch

Fig. 3a Features: god with a naked or garbed attendant behind or before; god holding/touching a crescent-standard; bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch Fig. 3b bull-man grasped/touched by a naked male figure Fig. 3b-f bull-man grasping an animal; Fig. 3d bull-man standing ‘above’ an animal; Fig. 3a : bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch करडूं or करडें (p. 137) [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं) A kid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

![]() Fig. 2 e-f god with a naked or garbed attendant behind or before; Fig. 2c-d god grasping/touching a gazelle

Fig. 2 e-f god with a naked or garbed attendant behind or before; Fig. 2c-d god grasping/touching a gazelle करडूं or करडें (p. 137) [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं) A kid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

![]() Features Fig. 1c-f: god with a naked or garbed attendant behind or before; Fig. 1d-e god seated on a stool/throne ‘above’ a bull; Fig. 1a-f god drinking through a tube leading to a jar; god holding a cup

Features Fig. 1c-f: god with a naked or garbed attendant behind or before; Fig. 1d-e god seated on a stool/throne ‘above’ a bull; Fig. 1a-f god drinking through a tube leading to a jar; god holding a cup

barad, balad, 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'

meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). dula ‘pair’.

Rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) dul meṛed, cast iron (Mu.) mẽṛhẽt baṭi = iron (Ore) furnaces (Santali)

kuDi 'drink' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' khaNDa 'water' rebus: khaNDa 'implements'

“Recent excavations on the island of Bahrain have uncovered a seal impression similar to a stamped seal tablet in the Yale Babylonian Collection. This Yale impression is dated to the tenth year of Gungunum, King of Larsa, in southern Babylonia – that is 1923 BCE. The Bahrain seal was found in a Barbar culture level, partially contemporary with the Umm an-Nar culture of Oman, which can in turn be paralled at Bampur V with the incised ware (‘hut-pot’) motifs. The general evidence, thus, points to a date c. 1900 BCE for the terminus of the Bampur sequence, and for the date of the Kurab shaft-hole pick-axe.” (Lamberg-Karlovsky, GC, 1969, Further Notes on the Shaft Hole Pick Axe From Khurab MakranIran, Vol. 7, 1969, pp 163-164) http://www.jstor.org/stable/4299621 .British Institute of Persian Studies

https://www.scribd.com/doc/315224554/Further-Notes-on-the-Shaft-Hole-Pick-Axe-From-Khurab-Makran-G-C-Lamberg-Karlovsky-Year-1969

Many sites on the Gulf of Khambat, and the site of Lothal evidence that the Sarasvati civilization was involved in trade through the Persian Gulf and beyond through Tigris-Euphrates upto Haifa, Israel in Ancient Near East.

![]() This is a remarkable square seal from Ur, with cuneiform script together with a bison/bull/ox hieroglyph. This may be called Gadd Seal 1 of Ur since this was the first item on the Plates of figures included in Gadd's paper. Assigned to the pre-Sargonic period, this is perhaps a seal of a Meluhha (Indus) merchant. Gadd lists 18 seals from Ur and sites in Babylonia, witn Indus-type writing system. Gadd Seal No. 2 is of circular shape with a button boss, perhaps of Persian Gulf origin (perhaps belongs to a Meluhha merchant in Bahrain). This seal plus seal nos. 3,4,5,15,16,17 have Indus script motifs and hieroglyphs. Seal no. 6 is cylindrical and Sumerian with hieroglyphs of zebu, scorpion, and other Indus Script hieroglyphs. Seal no. 7 has kuTi, 'tree' Indus Script hieroglyph (which signifies rebus kuThi 'smelter'). Seal no. 8 is Sumerian and perhaps relates to a Bahrain merchant who holds a goat (mlekh 'goat' rebus: milakkhu 'copper'), an Indus script hieroglyph. Seals 9,10,11, 12,13,14 are perhaps from Bahrain of a Meluhha merchant. Seal no. 15 was found with carnelian, steatite and copper beads in a Sargonid period grave, and is a Persian Gulf seal attributable to contacts with Sarasvati riverbasin (Gujarat carnelian in particular). Seal No. 16,17,18 are clearly those of Meluhha merchants in Bahrain. Seals found at Kish, Gawra and Asmar are of Indus Script corpora. Briggs Buchanan assigns Seal nos. 2,3,4,5 and 16 to Indus seal type I, a type which includes circular seals but with Indus script on the obverse. Seal no. 15 is categorised in type II as a crude Indus script imitation while seal no. 16 is categorised in type III as Persian Gulf Bahrain seal of the type found in Lothal and also Failaka. This tablet assigned to 10th year of Gungunum of Larsa (1923 BCE) is stamped by an Indus Script seal of type III in Buchanan classification of Persian Gulf seals.

This is a remarkable square seal from Ur, with cuneiform script together with a bison/bull/ox hieroglyph. This may be called Gadd Seal 1 of Ur since this was the first item on the Plates of figures included in Gadd's paper. Assigned to the pre-Sargonic period, this is perhaps a seal of a Meluhha (Indus) merchant. Gadd lists 18 seals from Ur and sites in Babylonia, witn Indus-type writing system. Gadd Seal No. 2 is of circular shape with a button boss, perhaps of Persian Gulf origin (perhaps belongs to a Meluhha merchant in Bahrain). This seal plus seal nos. 3,4,5,15,16,17 have Indus script motifs and hieroglyphs. Seal no. 6 is cylindrical and Sumerian with hieroglyphs of zebu, scorpion, and other Indus Script hieroglyphs. Seal no. 7 has kuTi, 'tree' Indus Script hieroglyph (which signifies rebus kuThi 'smelter'). Seal no. 8 is Sumerian and perhaps relates to a Bahrain merchant who holds a goat (mlekh 'goat' rebus: milakkhu 'copper'), an Indus script hieroglyph. Seals 9,10,11, 12,13,14 are perhaps from Bahrain of a Meluhha merchant. Seal no. 15 was found with carnelian, steatite and copper beads in a Sargonid period grave, and is a Persian Gulf seal attributable to contacts with Sarasvati riverbasin (Gujarat carnelian in particular). Seal No. 16,17,18 are clearly those of Meluhha merchants in Bahrain. Seals found at Kish, Gawra and Asmar are of Indus Script corpora. Briggs Buchanan assigns Seal nos. 2,3,4,5 and 16 to Indus seal type I, a type which includes circular seals but with Indus script on the obverse. Seal no. 15 is categorised in type II as a crude Indus script imitation while seal no. 16 is categorised in type III as Persian Gulf Bahrain seal of the type found in Lothal and also Failaka. This tablet assigned to 10th year of Gungunum of Larsa (1923 BCE) is stamped by an Indus Script seal of type III in Buchanan classification of Persian Gulf seals.

m417 Glyph: ‘ladder’: H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ Rebus: Pa. sēṇi -- f. ʻ guild, division of army ʼ; Pk. sēṇi -- f. ʻ row, collection ʼ; śrḗṇi (metr. often śrayaṇi -- ) f. ʻ line, row, troop ʼ RV. The lexeme in Tamil means: Limit, boundary; எல்லை. நளியிரு முந்நீரேணி யாக (புறநா. 35, 1). Country, territory.

Hieroglyph: *śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ. [Cf. śrētr̥ -- ʻ one who has recourse to ʼ MBh. -- See śrití -- . -- √śri]Ash. ċeitr ʻ ladder ʼ (< *ċaitr -- dissim. from ċraitr -- ?).(CDIAL 12720)*śrēṣṭrī2 ʻ line, ladder ʼ. [For mng. ʻ line ʼ conn. with √śriṣ2 cf. śrḗṇi -- ~ √śri. -- See śrití -- . -- √śriṣ2]

Pk. sēḍhĭ̄ -- f. ʻ line, row ʼ (cf. pasēḍhi -- f. ʻ id. ʼ. -- < EMIA. *sēṭhī -- sanskritized as śrēḍhī -- , śrēṭī -- , śrēḍī<-> (Col.), śrēdhī -- (W.) f. ʻ a partic. progression of arithmetical figures ʼ); K. hēr, dat. °ri f. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 12724) rebus: Seṭṭhi [fr. seṭṭha, Sk. śreṣṭhin] foreman of a guild, treasurer, banker, "City man", wealthy merchant Vin i.15 sq., 271 sq.; ii.110 sq., 157; S i.89; J i.122;ii.367 etc.; Rājagaha˚ the merchant of Rājagaha Vin ii.154; J iv.37; Bārāṇasi˚ the merchant of Benares J i.242, 269; jana -- pada -- seṭṭhi a commercial man of the country J iv.37; seṭṭhi gahapati Vin i.273; S i.92; there were families of seṭṭhis Vin i.18; J iv.62; ˚ -- ṭṭhāna the position of a seṭṭhi J ii.122, 231; hereditary J i.231, 243; ii.64; iii.475; iv.62 etc.; seṭṭhânuseṭṭhī treasurers and under -- treasurers Vin i.18; see Vinaya Texts i.102.

Seṭṭhitta

Seṭṭhitta (nt.) [abstr. fr. seṭṭhi] the office of treasurer or (wholesale) merchant S i.92.

The glyphics are:

Semantics: ‘group of animals/quadrupeds’: paśu ‘animal’ (RV), pasaramu, pasalamu = an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped (Te.) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)

Glyph: ‘six’: bhaṭa ‘six’. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

Glyph (the only inscription on the Mohenjo-daro seal m417): ‘warrior’: bhaṭa. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’. Thus, this glyph is a semantic determinant of the message: ‘furnace’. It appears that the six heads of ‘animal’ glyphs are related to ‘furnace’ work. This guild, community of smiths and masons evolves into Harosheth Hagoyim, ‘a smithy of nations’.

It appears that the Meluhhans were in contact with many interaction areas, Dilmun and Susa (elam) in particular. There is evidence for Meluhhan settlements outside of Meluhha. It is a reasonable inference that the Meluhhans with bronze-age expertise of creating arsenical and bronze alloys and working with other metals constituted the ‘smithy of nations’, Harosheth Hagoyim.

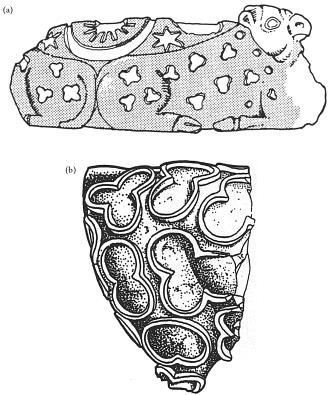

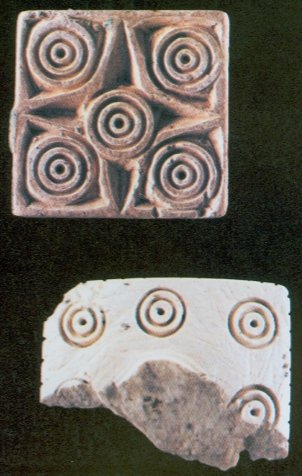

Dilmun seal from Barbar; six heads of antelope radiating from a circle; similar to animal protomes in Failaka, Anatolia and Indus. Obverse of the seal shows four dotted circles. [Poul Kjærum , The Dilmun Seals as evidence of long distance relations in the early second millennium BC, pp. 269-277.] A tree is shown on this Dilmun seal.

Glyph: ‘tree’: kuṭi ‘tree’. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali).

baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'

Izzat Allah Nigahban, 1991, Excavations at Haft Tepe, Iran, The University Museum, UPenn, p. 97. furnace’ Fig.96a.

There is a possibility that this seal impression from Haft Tepe had some connections with Indian hieroglyphs. This requires further investigation. “From Haft Tepe (Middle Elamite period, ca. 13th century) in Ḵūzestān an unusual pyrotechnological installation was associated with a craft workroom containing such materials as mosaics of colored stones framed in bronze, a dismembered elephant skeleton used in manufacture of bone tools, and several hundred bronze arrowpoints and small tools. “Situated in a courtyard directly in front of this workroom is a most unusual kiln. This kiln is very large, about 8 m long and 2 and one half m wide, and contains two long compartments with chimneys at each end, separated by a fuel chamber in the middle. Although the roof of the kiln had collapsed, it is evident from the slight inturning of the walls which remain in situ that it was barrel vaulted like the roofs of the tombs. Each of the two long heating chambers is divided into eight sections by partition walls. The southern heating chamber contained metallic slag, and was apparently used for making bronze objects. The northern heating chamber contained pieces of broken pottery and other material, and thus was apparently used for baking clay objects including tablets . . .” (loc.cit. Bronze in pre-Islamic Iran, Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bronze-i Negahban, 1977; and forthcoming).

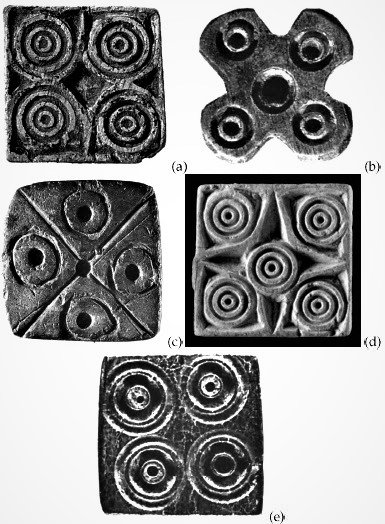

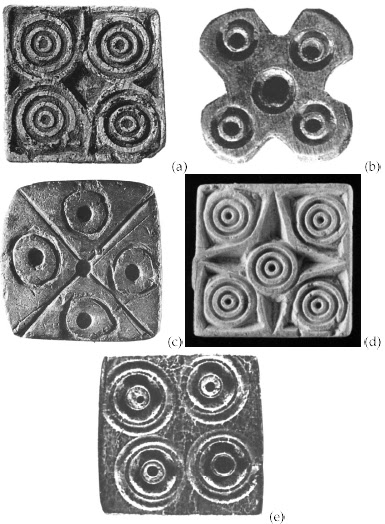

Stamp seals with figures and animals as Indus Script hieroglyphs![]() 220a

220a

![]() 220b

220b

![]() 220c,d,e

220c,d,e

![]() 220f,g

220f,ga. Dia 2.9 cm thickness 1.25 cm Gulf region, Bahrain, Karrana, Bahrain national Museum, Manama 4061

b. Dia 2.4 cm thickness 1.15 cm Gulf region, Bahrain, Karrana, Bahrain national Museum, Manama 4054

c. Dia 3 cm thickness 1.3 cm Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum 881 AIT

d. Dia 6.5 cm thickness 3 cm. Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum

e. Dia 2.8 cm thickness 1.3 cm Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum

f. Dia 2.5 cm thickness 1.3 cm Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum 881 UK

g. Dia 3.5 cm thickness 1.25 cm Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum 1129 CE.

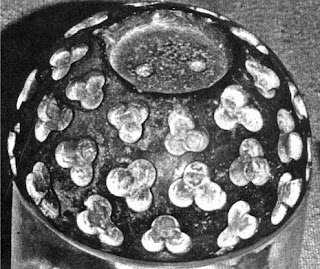

“A number of decorative elements on the seals excavated at Bahrain and Failaka – two islands in the Gulf, which have been identified with the legendary kingdom of Dilmun – can be traced to Mesopotamia, Iran, the Indus Valley, Anatolia, and Central Asia. The cultural influences that these foreign motifs reflect stemmed from the maritime trade that connected the far-flung cities of the region beginning about 2500 BCE and lasting until about 1500 BCE. Epigraphic evidence from dated seal impressions and tablets found at Susa and Ur suggests that the Dilmun stamp seals, with their distinctive shape, were made between the end of the third millennium BCE and the early second millennium BCE. They are characterized by a flat obverse and a hemispherical reverse. Their backs are pierced for suspension and scored with multiple grooves at right angles to the piercing. Pairs of concentric circles are placed symmetrically on eithr side of the groose. Other characteristic features of the Dilmun glyptic include the manner in which animals and human figures are depicted. Deep cavities mark the eyes of animals, and there is no indication of a pupil; human figures, seen in profile, have linear bodies and stylized facial features rendered with horizontal lines. Foreign decorative elements on Dilmun seals include typical third-millennium BCE Mesopotamian imagery centered on male figures engaged in a rich repertoire of activities, including presentations in which local gods are occasionally adorned with the Mesopotamian horned crown as protectors of the flock; in contests with animals (see nos. 220d,e). In these scenes the adaptation of Mesopotamian dress, horned crown, bull-men (see no. 220c), standards, and lyres with taurine sound boxes (see no. 220f) indicates a close contact between the two regions and may signify a spiritual affinity. In catalogue number 220a a seated figure holds an axelike tool in one hand and reaches for the hand of a standing winged creature, possibly a deity, with the other. Similar winged figures on seals dating to the third millennium BCE are known from both Mesopotamia and Central Asia. The northern connection is underscored in this image by a solitary foot (here with four toes), a motif known from Central Asia and Syria and Iran. Two more seemingly unrelated elements – a bird and a gazelle – complete the composition. Ships and boats are a common theme. In catalogue number 220b the image can be interpreted as a variation of the Mesopotamian contest scene. Here, the central figure dressed in a tufted garment stands in a boat. He graps the animal’s foreleg with one hand, while the other is extended towards a companion figure. The craft resembles the modern-day mashluf – a small boat with a rather shallow draft, ideal for marsh travel. The boat with its upturned stern is reminiscent of vessels depicted in the earlier seals of Ur, a motif rarely occurring the second-millennium BCE Mesopotamian glyptic. The Mesopotamian pictorial repertoire is again reflected on a Dilmun seal showing two figures in an architectural setting (cat. No. 220c). The motif may best be compared with that of an early Old Babylonian seal in the Yale Babylonian Collection, New Haven, where suppliant deities and worshippers face an altar within a temple. They raise their hands in a gesture of respect toward a star standard on a podium. On the roof are two winged creatures and two vertical snakes that may be grasping. Two nude, double-belted fantastic beings with what seems to be three horns flank the structure and repeate the central worshippers’ gestures. Local decorative motifs such as a rosette, three stars, and two tree branches complete the harmonious, almost symmetrical composition that is so typical of later Dilmun seals. Mesopotamian banquet imagery occurs on three seals. In catalogue number 220e a high podium on which a small jar is placed separates two seated figures who confront each other. One of them is drinking through a long straw from a jar comparable in size to the one on the podium. This drinking scene closely parallels the image on a sealing dated to the reign of Gungunum of Larsa. Such drinking scenes must have had propitious significance for local Dilmunite seal owners. On a second seal with banquet imagery – by far the largest of the seven seals discussed here – two men dressed in tiered, flounced skirts face eath other (cat. No. 220d). Seated on rectangular stols, they are flanked by a ladder and a bird; between them are four vessels beneath a crescent and a star. Below, occupying most of the seal’s surface, are two vertical rows of bovids and recumbent antelopes. Two human figures, one nude, the other clothed, each raise one hand. On the third seal a seated man plays a three-stringed lyre (cat. No. 220f). The sound box is similar to Mesopotamian examples, such as those excavated from the royal tombs of Ur and those depicted on the Standard of Ur and in glyptic art. On preserved Mesopotamian lyres, bulls’ heads decorate the boxes, but in the present example the artists has created the music box out of the body of a bull so that its back acts as a strut – a detail paralleled on a stele from Tello, where the sound box of a lyre is formed by two superimposed bulls, one in profile. Seals with a radial composition form a distinct group. An example in this exhibition (cat. No. 220g) displays six antelope heads radiating like a six-pointed star from a central point. This decoration closely resembles that on sealings excavated at the early-second-millennium BCE site of Acemhovuk, in central Anatolia. Similar compositions are recorded earlier, however, at the site of Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley.

(Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp.320-321)

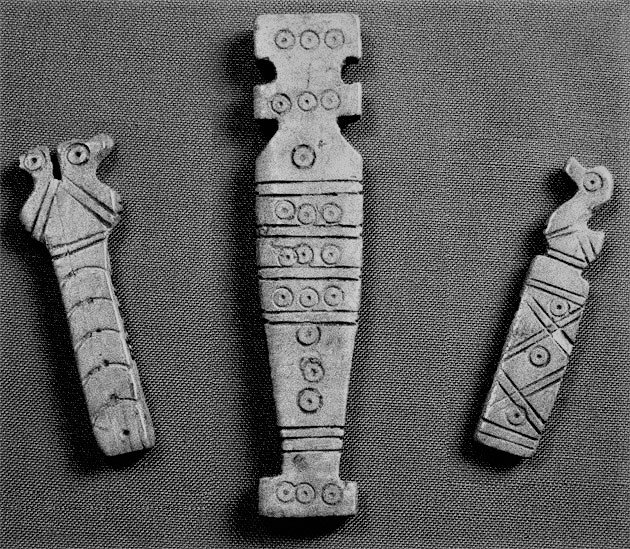

![]() cat.no. 218

cat.no. 218

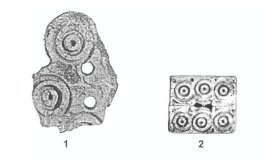

“218. Cylinder seal with confronted figures and a tree. Steatite h 2.2 cm dia 1.15 cm Gulf region, Failaka F6 1174 Early Dilmun ca. 2000-1800 BCE National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum 1129 AXJ. The cylindrical form and the imagery of the seal exhibited here clearly illustrate how strong was Mesopotamian influence on the glyptic art of the Gulf. The image is a crude imitation of a Mesopotamian banquet scene. Two figures are seated on stools, which have been made to differ slightly by the addition of a second horizontal bar to one on the right. Horned headdresses identify the figures as deities. They are dressed in garments with tufts, indicated by the vertical striations, and their lower bodies appear exaggeratedly triangular. A crescent fills the space above and between them. Two nude worshippers, each of whom holds a crescent, flank a stylized tree, perhaps a date palm. Although the scene may have Mesopotamian roots, the peculiar details of the tree and the manner in which the humans are depicted – with elongated bodies and horizontal facial features – are typical of Gulf seals. This seal has counterparts at Susa, in Iran, where similarly nude worshippers are shown in front of enthroned deities.”(Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp.318-319)

![]() cat. no. 221

cat. no. 221

“221. Stamp seal with a boat scene. Steatite. L. 2 cm, w. 1.9 cm Gulf region, Failaka, F6 758 early Dilmun, ca. 2000-1800 BCE National Council of Culture, Arts, and Letters, Kuwait National Museum, 1129 ADY. This seal from Failaka island, at the head of the Gulf, is unusual in shape, as it is square rather than circular possibly alluding to the most common form of Harappan seals. The subject is a nude male figure standing in the middle of a flat-bottomed boat, facing right. The man’s arms are bent at the elbow, perpendicular to his torso. Beside him two jars stand on the deck of the boat, each containing a long pole to which is attached a hatched square that perhaps represents a banner. Flat-bottomed vessels with a single sail were used to transport cargoes in shallow tidal waters, but the one illustrated on this seal lacks a sail. If the two vertical posts on the stern are interpreted as steering paddles, then it resembles a model found in India at Lothal, which appears to have had square sails. Although the seal’s shape is atypical, all the decorative elements, including the boat and the two jars, find parallels on other seals from Dilmun, indicating that this one was made in the region where it was found.” (Note: On the Lothal boat model, three blind holes used as sockets may have held the masts of square-shaped sails.)(Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp.322-323)

Early Near Eastern Seals in the Yale Babylonian Collection, by Briggs Buchanan, with introduction and seal inscriptions by William W. Hallo, edited by Ulla Kasten. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1981.

Uruk-period seal (NBC 2579).

![]()

Seal no. 79 Persian gulf cylinder seal with seated person. Burnt steatite. H. 2.7 cm, dia 1.4 cm; string hole .3 cm Late 3rd-early 2nd millennium BCE Sb 1383 Excavated by Mecquenem. “The Mesopotamian influence on glyptic from the Persian gulf area is very clearly demonstrated in this example, one of the few cylinder seals executed in this distinctive style. Close parallels are found at Failaka, in the Gulf. Adopted here are not only the Mesopotamian cylinder-seal shape but also the theme of a worshipper standing before a seated horned deity in a flounced (?) garment and a version of the context scene with crossed animals. Pecular iconographic details also appear, however, such as the nude worshipper with his hand in a pot; the two ‘master of animals’, one nude and one kilted, grasping the animals’ necks; and the snake framing the scene from above. Glyptic and textual evidence suggests that the cities of Susa and Ur were trading centers in close contact with ancient Dilmun, located in the Persian Gulf. This contact, however, does not seem to have been limited to an exchange of goods. Francois Vallat has noted, the chief god of Dilmun, was one of a triad of deities worshipped on the Susa Acropole in the eighteenth century BCE. Persian Gulf-style seals found at Susa and other foreign sites with Mesopotamian and Indus-derived themes incorporated into their iconography were created, some scholars believe, for Dilmunite traders living abroad.” (The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre By Musée du Louvre, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992, p.120)

![]() A bun-ingot flanked by two goats: mlekh 'goat' rebus: milakkhu 'copper' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS muh

A bun-ingot flanked by two goats: mlekh 'goat' rebus: milakkhu 'copper' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS muh ingot

. Thus copper ingot. The dotted circles and three lines on the boss: dhAv 'strand' rebus: dhAv, dhAtu 'mineral' kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' tri-dhAtu 'three strands' rebus: three minerals. Thus the seal signifies a copper mineral cast ingot and a smithy/forge working with three minerals, tridhAtu. Seal of the old Elamite period in Metmuseum cat. no. 78 Persian Gulf stamp seal with two caprids. Burnt steatite. 2.2 cm. dia, .8 cm ht. Late 3rd -early 2nd millennium BCE Sb1015 Excavated by Mecquenem

The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre By Musée du Louvre, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992 “Many objects found at Susa reflect contacts with the Persian Gulf region…A mercantile document and a basket sealing were stamped with Gulf-style seals. Elamite imitations of Gulf seals were made in the local bitumen compound. Perhaps the most characteristic type of Persian Gulf seal is illustrated by this piece, one of four burnt, (whitened) steatite stamp seals found at Susa that have distinctive grooves and dot circles incised on a raised boss on the back. The face of this seal is engraved with the figures of two goats crouching head to foot on opposite sides of the circular field, the center of which is marked by a lozenge. Their slightly modeled bodies are defined by a curving outline, and distinctive details, such as large dot-circle eyes and striated necks, are sharply cut. Similar seals are known mainly from the Gulf region (and one example was found at Lothal in India). They were also exported to, and imitated at, the southern Mesopotamian city of Ur, a site with cuneiform texts that refer to the import of copper, semiprecious stones, and perhaps pearls from Dilmun. They are datable to the end of the third and the beginning of the second millennium BCE. That is the period when one elaborate Persian Gulf seal depicting a a Mesopotamian-derived ‘banquet scene’ was stamped on an old Babylonian contract between two merchants. The tablet, written in the time of Gungunum, ruler of Larsa in the late twentieth century BCE, is in the Yale Babylonian Collection. The document from Susa mentioning a Dilmunite merchant and ten minas of copper dates to the same period.” (p.119)

![]() Yale tablet. Bull's head (bucranium) between two seated figures drinking from two vessels through straws. YBC. 5447; dia. c. 2.5 cm. Possibly from Ur. Buchanan, studies Landsberger, 1965, p. 204; A seal impression was found on an inscribed tablet (called Yale tablet) dated to the tenth year of Gungunum, King of Larsa, in southern Babylonia--that is, 1923 B.C. according to the most commonly accepted ('middle') chronology of the period. The design in the impression closely matches that in a stamp seal found on the Failaka island in the Persian Gulf, west of the delta of the Shatt al Arab, which is formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

Yale tablet. Bull's head (bucranium) between two seated figures drinking from two vessels through straws. YBC. 5447; dia. c. 2.5 cm. Possibly from Ur. Buchanan, studies Landsberger, 1965, p. 204; A seal impression was found on an inscribed tablet (called Yale tablet) dated to the tenth year of Gungunum, King of Larsa, in southern Babylonia--that is, 1923 B.C. according to the most commonly accepted ('middle') chronology of the period. The design in the impression closely matches that in a stamp seal found on the Failaka island in the Persian Gulf, west of the delta of the Shatt al Arab, which is formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

karaṇḍa 'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa 'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) kaNDa 'divisions' rebus: kaNDa 'implements' muh 'face' rebus: muhA 'quantity of smelted metal taken out of a furnace';'ingot' kaNDa 'water' rebus: kaNDA 'implements' kanda 'fire-altar' meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'supercargo'. dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' dhAV 'strand' rebus: dhAv 'mineral, dhAtu'

![failakaseal-t.jpg (4854 bytes)]() Failaka seal. The Yale tablet is dated to ca. the second half of the twentieth century B.C.... Trade3 on the Persian gulf was in existence well before that time-- about 2350 B.C.-- when Sargon, the first Akkadian king referred to ships from or destined for Melukhkha, Magan and Tilmun (Dilmun) at his wharves. in the Third Dynasty of Ur (around 2000), when trade apparently was centred at Magan. It is even better documented on other tablets from Ur (from about 1900 and from about 1800), belonging to various kings of Larsa. At this time the trade was centered at Tilmun... Cuneiform inscriptions naming Inzak, the god of Tilmun, were found on Failaka and, a long time ago, one on Bahrein... Failaka can be equated with Tilmun, or at least was an important part of it. (Briggs Buchanan, A dated seal impression connecting Babylonia and ancient India, Archaeology, Vol. 20, No.2, 1967, pp. 104-107).

Failaka seal. The Yale tablet is dated to ca. the second half of the twentieth century B.C.... Trade3 on the Persian gulf was in existence well before that time-- about 2350 B.C.-- when Sargon, the first Akkadian king referred to ships from or destined for Melukhkha, Magan and Tilmun (Dilmun) at his wharves. in the Third Dynasty of Ur (around 2000), when trade apparently was centred at Magan. It is even better documented on other tablets from Ur (from about 1900 and from about 1800), belonging to various kings of Larsa. At this time the trade was centered at Tilmun... Cuneiform inscriptions naming Inzak, the god of Tilmun, were found on Failaka and, a long time ago, one on Bahrein... Failaka can be equated with Tilmun, or at least was an important part of it. (Briggs Buchanan, A dated seal impression connecting Babylonia and ancient India, Archaeology, Vol. 20, No.2, 1967, pp. 104-107).

dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' karaṇḍa 'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa 'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:kolimi 'smithy, forge' kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' muh 'face' rebus: muhA 'quantity of smelted metal taken out of a furnace';'ingot' kaNDa 'water' rebus: kaNDA 'implements' kanda 'fire-altar' meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'supercargo'.dhAV 'strand' rebus: dhAv 'mineral, dhAtu'

Gadd, CJ, 1932, Seals of ancient Indian style found at Ur, in: Proceedings of the British Academy, XVIII, 1932, Plate 1, no. 1. Gadd considered this an Indus seal because, 1) it was a square seal, comparable to hundreds of other Indus seals since it had a small pierced boss at the back through which a cord passed through for the owner to hold the seal in his or her possession; and 2) it had a hieroglyph of an ox, a characteristic animal hieroglyph deployed on hundreds of seals.

This classic paper by Cyril John Gadd F.B.A. who was a Professor Emeritus of Ancient Semitic Languages and Civilizations, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, opened up a new series of archaeological studies related to the trade contacts between Ancient Far East and what is now called Sarasvati-Sindhu (Hindu) civilization.

There is now consensus that Meluhhan communities were present in Ur III and also in Sumer/Elam/Mesopotamia. (Parpola S., A. Parpola & RH Brunswig, Jr., 1977, The Meluhha village. Evidence of acculturation of Harappan traders in the late Third Millennium Mesopotamia in: Journal of Economic and Social History of the Orient, 20, 129-165.)

Use of rebus-metonymy layered cipher for the entire Indus Script Corpora as metalwork catalogs provides the framework for reopening the investigation afresh on the semantics of the cuneiform text on Gadd Seal 1, the Indus seal with cuneiform text.

This renewed attempt to decipher the inscription on the seal starts with a hypothesis that the cuneiform sign readings as: SAG KUSIDA. The ox is read rebus in Meluhha as: barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. The gloss bharata denoted metalcasting in general leading to the self-designation of metalworkers in Rigveda as Bharatam Janam, lit. metalcaster folk.

While SAG is a Sumerian word meaning 'head, principal' (detailed in Annex A), KUSIDA is a Meluhha word well-attested semantically in ancient Indian sprachbund of 4th millennium BCE. The semantics of the Meluhha gloss, kusida signifies: money-lender (Annex B). Thus SAG KUSIDA is a combined Sumerian-Meluhha phrase signifying 'principal of chief money-lender'. This could be a clear instance of Sumerian/Akkadian borrowing a Meluhha gloss.

SAG KUSIDA + ox hieroglyphon Gadd Seal 1, read rebus signifies: principal money-lender for bharata metal alloy artisans. This reading is consistent with the finding that the entire Indus Script Corpora are metalwork catalogs.

The money-lender who was the owner of the seal might have created seal impressions as his or her signature on contracts for moneys lent for trade transactions of seafaring merchants of Meluhha.

The Gadd Seal 1 of Ur is thus an example of acculturation of Sumerians/Akkadians in Ur with the Indus writing system and underlying Meluhha language of Meluhha seafaring merchants and Meluhha communities settled in Ur and other parts of Ancient Near East.

Annex A: Meaning of SAG 'head, principal' (Sumerian)

The Sumerians called themselves sag-giga, literally meaning "the black-headed people"

![B184ellst.png]() Cuneiform sign SAG

Cuneiform sign SAG- phonetic values

- Sumerian: SAG, SUR14

- Akkadian: šag, šak, šaq, riš

sign evolution

- 1. the pictogram as it was drawn around 3000 BC;

- 2. the rotated pictogram as written around 2800 BC;

- 3. the abstracted glyph in archaic monumental inscriptions, from ca. 2600 BC;

- 4. the sign as written in clay, contemporary to stage 3;

- 5. late 3rd millennium (Neo-Sumerian);

- 6. Old Assyrian, early 2nd millennium, as adopted into Hittite;

- 7. simplified sign as written by Assyrian scribes in the early 1st millennium.

Akkadian Etymology

Noun

𒊕 (rēšu, qaqqadu) [SAG]

- head (of a person, animal)

- top, upper part

- beginning

- top quality, the best

Sumerian:

(SAG)

- head

Derived terms[edit]

- SAG(.KAL) "first one"

- (LÚ.)SAG a palace official

- ZARAḪ=SAG.PA.LAGAB "lamentation, unrest"

- SAG.DUL a headgear

- SAG.KI "front, face, brow"

http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%F0%92%8A%95Annex B: Meaning of kusīda 'money-lender'

कुशीदम् Usury; see कुसी. कुषीद a. Indifferent, inert. -दम् Usury. कुसितः 1 An inhabited country. -2 One who lives on usury; see कुसीद below. कुसितायी kusitāyī (= कुसीदायी).कुसी kusī (सि si) द d कुसी (सि) द a. Lazy, slothful. -दः (also written as कुशी-षी-द) A monkey-lender, usurer; Mbh.4.29. -दम् 1 Any loan or thing lent to be repaid with in- terest. -2 Lending money, usury, the profession of usury; कुसीदाद् दारिद्र्यं परकरगतग्रन्थिशमनात् Pt.1.11; Ms. 1.9;8.41; Y.1.119. -3 Red sandal wood. -Comp. -पथः usury, usurious interest; any interest exceeding 5 per cent; कृतानुसारादधिका व्यतिरिक्ता न सिध्यति कुसीदपथमा- हुस्तम् (पञ्चकं शतमर्हति) Ms.8.152. -वृद्धिः f. interest on money; कुसीदवृद्धिर्द्वैगुण्यं नात्येति सकृदाहृता Ms.8.151. कुसीदा kusīdā कुसीदा A female usurer. कुसीदायी kusīdāyī कुसीदायी The wife of a usurer. कुसीदिकः kusīdikḥ कुसीदिन् kusīdin कुसीदिकः कुसीदिन् m. A usurer. (Samskritam. Apte) kúsīda ʻ lazy, inert ʼ TS. Pa. kusīta -- ʻ lazy ʼ, kōsajja -- n. ʻ sloth ʼ (EWA i 247 < *kausadya -- ?); Si. kusī ʻ weariness ʼ ES 26, but rather ← Pa.(CDIAL 3376). FBJ Kuiper identifies as a 'borrowed' word in Indo-Aryan which in the context of Indus Script decipherment is denoted by Meluhha as Proto-Prakritam: the gloss kusīda 'money-lender'. (Kuiper, FBJ, 1948, Proto-Munda words in Sanskrit, Amsterdam: Noord-Hollandsche Uit. Mij.; Kuiper, FBJ, 1955, Rigvedic loan-words in: O. Spies (ed.) Studia Indologica. Festschrift fur Willibald Kirfel Vollendung Seines 70. Lebensjahres. Bonn: Orientalisches Seminar; Kuiper, FBJ, 1991, Arans in the Rigveda, Amsterdam-Atlanta: Rodopi).

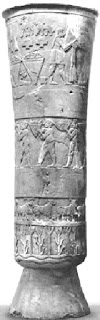

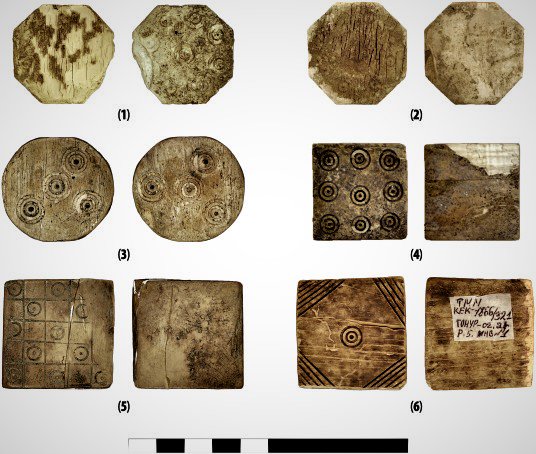

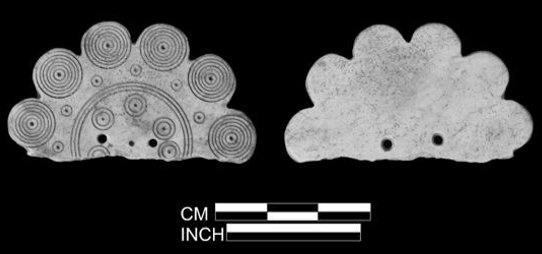

![]() Dilmun seals from Saar

Dilmun seals from SaarDilmun is a trading post on the 'Lower Sea'. In Mesopotamian mythology, Dilmun is the land of immortality, a favourite meeting place of the gods, which was visited by the hero Gilgamesh in his search for everlasting life. Inscriptions indicate that the ancestors of the Sumerians came from Dilmun, and it was here that they learnt the art of writing. We agree with S.N.Kramer's observations identifying Dilmun with the Sarasvati-Sindhu (Indus) valley. The God Enki is said to have given his son Inzak dominion over Dilmun. On the Lagash tablet (ca. 2520 BC) is recorded: "The ships of Dilmun from the foreign lands brought me woods". A document of ca. 1800 BC refers to an expedition "to Dilmun to buy copper there'. Sargon of Assyria (710 BC) notes that "he had received presents from the King of Dilmun, a land which lies like a fish, 60 hours away in the midst of the sea of the rising sun".

An Assurbanipal clay cylinder states: Dilmun ki s'a qabal ta_mtim s'apli_t (Dilmun is in the midst of the lower sea) (D.D. Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria, ARAB, II 970. A Ungnad, ZA 31 (1917): 34, 1.9. That Dilmun was a continental coastland may be surmised from Sargon II's great Display inscription: bi_t-ia-kin s'a kis'a_d na_r marrati adi pa_t Dilmun (Bi_t-Iakin which (extends) from the bank of the brackish river to the border of Dilmun)(Luckenbill, ARAB, 54 = 82 =99). Sargon II's inscription states: Upe_ri s'ar Dilmun s'a ma_la_k 30 be_ru ina qabal ta_mtim s'a nipih s'ams'i ki_ma nu_ni s'itkunu narbasu (Upe_ri, king of Dilmun, whose resting place is 30 double hours away like a fish in the midst of the ocean of the rising sun)(Luckenbill, ARAB, 41,70). During the reign of Sargon of Assyria, Dilmun and Magan are stated to be "on the farther side of the lower sea" and there is also a reference to the " sea of Magan" (J.Muhly, Copper and Tin, p. 226; W.F. Leeman, Foreign Trade, p. 81, n.11; M. Weitemeyer, Acta Orientalia, 27 (1964): 207; E. Weidner, AfO, 16 (1953): 5, 1.42). The timber for the boats in Bahrain always came from India. The name of the Meluhha-boat is magilum (Enki and the World Order 128).[Boats which plied on the Sindhu river are called mohanna.]

"The Ninevite Gigamesh Epic, composed probably at the end of the second millennium BC, has Utnapishtim settled "at the mouth of the rivers", taken by all commentators to be identical with Dilmun." (W.F.Albright, The Mouth of the Rivers, AJSL, 35 (1919): 161-195).

The mouth of the rivers may relate to the Rann of Kutch/Saurashtra lying at the mouth of the Sindhu and Sarasvati rivers. In the Sumerian myth Enki and Ninhursag, which recounts a Golden Age, paradise is described: "The crow screams not, the dar-bird cries not dar, the lion kills not... the ferry-man says not 'it's midnight', the herald circles not round himself, the singer says not elulam, at the outside of the city no shout resounds." The cry of the sea-faring boatmen in Indian languages on the west-coast is: e_le_lo!

Lines 123-129; and interpolation UET VI/1:

"Let me admire its green cedars. The (peole of the) lands Magan and Dilmun, Let them come to see me, Enki! Let the mooring posts beplaced for the Dilmun boats! Let the magilum-boats of Meluhha transport of gold and silver for exchange...The land Tukris' shall transport gold from Harali, lapis lazuli and bright... to you. The land Meluhha shall bring cornelian, desirable and precious sissoo-wood from Magan, excellent mangroves, on big ships The land Marhashi will (bring) precious stones, dushia-stones, (to hang) on the breast. The land Magan will bring copper, strong, mighty, diorite-stone, na-buru-stones, shumin-stones to you. The land of the Sea shall bring ebony, the embellishment of (the throne) of kingship to you. The land of the tents shall bring wool... The city, its dwellin gplaces shall be pleasant dwelling places, Dilmun, its dwelling place shall be a pleasant dwelling place. Its barley shall be fine barley, Its dates shall be very big dates! Its harvest shall be threefold. Its trees shall be ...-trees."

We postulate a hypothesis that Dilmun refers to the Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization area and that MAR-TU refer to the people of Marusthali (the present-day Thar-Cholistan on the banks of the Sarasvati river.) In the context of the decipherment of the script inscriptions as lists of bronze-copper weapons, the following analysis based on Uruk texts is significant:

"Almost from the beginning of the excavations in the ruins of the old city of Uruk in Lower Mesopotamia in 1928, work has concentrated on uncovering large parts of the temple area of that city, the holy district of Eanna... It was in these various layers and accumulations of debris covering large parts of the Eanna district that over the years more than four thousand clay tablets and fragments were found... In the Archaic Metals List we again find DILMUN in a line which due to a common denominator proves to be part of an internally cohesive group of entries. The entire list starts out with a sequence of metal vessels and continues with metal tools and weapons. This group opens with a sequence of various daggers, continues with various groups of unidentified objects and from line 23 on shows five entries with the common denominator tun2, 'axe'. The lines read in tentative translation: 'big axe', 'two-handed axe', 'one-handed axe', 'x-axe', and 'Dilmun axe'. Here most likely the differentiation bears on differences in shape, size or function; the 'two-handed axe' may mean a double-edged axe, for instance. Again, if seen as a coherent context DILMUN may be used here as equivalent to 'Dilmun-type axe'. I do not think it could just refer to the provenance of an axe but rather to specific qualities... three texts clearly are dealing with textiles but only one of them has a context which might be interpreted; tentatively it reads' 1 bale of DILMUN garment'... as the title following the one containing the sign for DILMUN we find the comosite sign for namesda, the title of the opening line of the Archaic Professions list. It is supposed that this title represents the highest official. Probably without all connotations of the terms 'ruler' or 'king' it nevertheless should be fairly close. The preceding line contains a number of signs which if translated literally could mean 'the prince of the good Dilmun-house (or temple)'. The exact meaning is elusive. To sum up, from our texts we do not get an adequate picture of the relations of Babylonia, or the city of Uruk, with Dilmun. On a general level, however, we can conclude that not only did such relations exist already by the end of the fourth millennium BC, but that these contacts apparently were not restricted to trade. To be sure, the exchange of metal and ttextiles may represent the main ties, but the existence of titles containing Dilmun in their name in normal Babylonia contexts like the Professions List point to much closer mutual contacts that would be sustained by occasional trade. The same is suggested by the existence of DILMUN in generic designations for kinds of textiles or metal tools. We certainly are entitled to assume that these relations had existed long before the emergence of writing." [Hans J. Nissen, The occurrence of Dilmun in the Oldest texts of Mesopotamia, pp. 335-339].

In the Old Babylonian period, some Mesopotamian seals depict a deity holding a crook. (cf. Seal 124 in Macropoli Collection). The deity also appears with his foot on a gazelle, but sometimes on a small pedestal; he wears a long robe or a kilt and on his head a horned headdress or a tall cylindrical hat. He has been identified as the god AMURRU. In texts and cylinder seal impressions his name is written d/AN.MAR.TU or d/MAR.TU, i.e., AMURRU(M), 'GOD OF THE WEST' in Akkadian. He is often loosely called the god of the Amorites because of his association in texts with the desert and steppe. He became the son of Anu the sky god and was often associated with Sin the moon god. He was referred to as the warrior god. The association with the desert is remarkable. In the Sarasvati Sindhu valley area, the arid zone on the banks of the Sarasvati river is called MARUSTHALI (now called Thar/Cholistan or Great Indian Desert). And, MARUTS are celebrated in the Rigveda as wind-gods, echoing the phenomenon of the 'a_ndhi' or sandstorms common in the region of Thar/Cholistan desert.

"From the Ur III (2112-2004 BC) and Isin-Larsa (2025-1763) periods, we have a number of textual sources which suggest that an ethnic group of people called MAR-TU were associated with the land of Dilmun-- the first of three entities found to be trade partners with Mesopotamia from at least 2500 BC (the others being Makkan and Meluhha). From Drehem, a city near Nippur, we note the occurrence in two texts (dated to AS 2-2044 BC)(CST 254 and TRU 305) of a colophon which reads 'MAR-TU (and) Diviners coming from Dilmun' (or MAR-TU Diviners coming from Dilmun)(BUccellati 1966: 249)... In addition, other evidence suggests that the MAR-TU were associated with (sea) fishing (Civil 1961: Buccellati 1966: 90). Thus Buccellati and later Gelb concluded that the MAR-TU existed in the south in the area of the Gulf as far as Bahrain (Gelb 1968: 43; 1980: 2). Finally, this linkage is suggested by a text from Eshnunna, a Mesopotamian city on the Diyala river. In this text most likely dated to Is'aramas'u (c. 1970 BC) MAR-TU are arranged by segmented lineage affiliation (babtum). The total states that twenty-six MAR-TU are e-lu-tum-me, a term perhaps best translated as meaning' trustworthy' or 'reliable' vis-a-vis the local Eshnunna officials. One MAR-TU from the lineage of Bas'anum is said to be a-ab-ba-ta or 'from the sea (lands)' or the land across the sea (Gelb 1968: 43)... the newely discovered Ibla texts mention the MAR-TU principally in connection with metal daggers (Pettinato 180: 9 and commentary) and prisoners of war (Pettinato 1981b: 120, see text TM 75G.309). (Note also the MAR-TU name Iblanum as meaning man from Ibla, Buccellati 1966: 155, 246)... From the early second millennium BC, we have a much wider body of evidence dealing with the MAR-TU. This is due to the greatly increased numbers of MAR-TU escaping the hamad and entering the settled zones. As early as S'u-Sin year (2034 BC) we see that a large defensive wall was being built in central Mesopotamia for the express purpose of keeping out the MAR-TU (the MAR-TU wall (called) the one which keeps Didanum away, Buccellati 1966: 92). Unfortunately, by the early reign of the succeeding king, Ibbi-Si, things had changed:

Reports that hostiel MAR-TU had entered the plains having been received, 144,000 gur grain (representing) the grain in its entirety was brought into Isin. Now the MAR-TU in their entirety have entered the interior of the country taking one by one all the great fortresses. Because of the MAR-TU I am not able to provide... for that grain... (Jacobsen 1953: 40)

According to the year date of Ibbi-Sin 17, some of these MAR-TU apparently came from the Gulf region: 'The year the MAR-TU, the powerful south wind who, from the remote past, have not known cities, submitted to Ibbi-Sin, the king of Ur.' (cf. also Gelb's views, 1961: 36)... Oppenheim's review of UET V suggests that Ur apparently served as a focal point and port for foreign trade, specifically with Dilmun (Oppenheim 1954: 8, n.8). A number of texts describe this activity as traders called alik Dilmun sailed to Dilmun and exchanged goods. A number of texts (e.g. UET V 286, 297, 549 and 796) clearly demonstrate that individuals with MAR-TU names were involved in the trade (e.g. in UET V 297 a certain Zuabbaum; in UET V 549 a person named Milkudanum; and in UET V 796 Alazum). This then is a clear link between Dilmun and the MAR-TU-- a hypothesis already formulated from a number of literary texts and Ur III economic records... It seems clear in summary that the MAR-TU were linked to Dilmun in a political sense (rulers in southern Mesopotamian towns), commercial agents in Mesopotamia (alik Dilmun), and inhabitants of Dilmun itself (Susa Tablet, UET V 716).[Juris Zarins, MAR-TU and the land of Dilmun, 232-249 in: Shaikha Haya Ali Al Khalifa and Michael Rice (eds.) Bahrain through the ages: the archaeology, London, KPI, 1986.]

Sir Henry Rawlinson in 1880 suggested that Dilmun of the Sumerian and Akkadian texts might be identified with Bahrain island. This was on the basis of a stone cone found by Captain Durand during an archaeological survey of Bahrain in 1879, but later lost. The text related to the temple of Inzak, elsewhere known as the god of Dilmun. (Captain Durand, Extracts from Report on the Islands and Antiquities of Bahrain, with notes by Major-General Sir. H.C. Rawlinson, JRAS, N.S. 12 (1880): 189-227, with two maps. Also suggested by Fr. Hommel, Ethnologie und Geographie des Alten Orients, 1904/1926, p. 24, 270.) Since then various identifications have been suggested such as: encompassing Saudi Arabian mainland in the area called Dilmun, Iranian side of the Persian Gulf as constituting Dilmun, Al-Qurna in southern Iraq and the Indus Valley (S.N.Kramer). All these identifications suggest that not all of them are valid for all periods of Mesopotamian history. Throughout Mesopotamian history, however, Dilmun has been an important trade centre, and 'one of the remote areas which was at times within the reach of Mesopotamian political influence. Noticeable among the early texts mentioning Dilmun is that of Urnanshe who had wood transported to Mesopotamia from Dilmun (ca. 2500 BC). In the same early period copper is known to hae been exported from Dilmun to Sumer. About 2100 BC Urnammu of the 3rd dynasty of Ur reopened the Arabian Gulf trade, this time with direct contact with Magan, from which copper was exported to Mesopotamia. The Dilmun trade flourished in the Larsa period (ca. 2000-1763 BC), but then died out. After an interim of 400 years Kassite influence appears in Dilmun (early 14th century BC). It seems that at this time the only export article was dates. Under Sargon of Assyria (end of 8th century BC) Upe_ri, king of Dilmun, is recorded to have sent tribute to the Assyrian empire. In 544 BC, Dilmun disappears from Mesopotamian history when, according to an administrative document, Nabonidus, king of Babylon, had a governor there. Dilmun is also mentioned in Sumerian literary texts as a famous place of prosperity and happiness, and even of eternal life, with the result that comparisons with the Biblical paradise have been made.' (Bendt Alster, Dilmun, Bahrain, and the alleged paradise in Sumerian Myth and Literature, in: Daniel T. Potts (ed.), Dilmun: New studies in the archaeology and early history of Bahrain, Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1983, pp. 39-74). (See also: Daniel Potts, Dilmun: Where and When? Dilmun: Journal of the Bahrain Historical and Archaeological Society, 11 (1983): 15-19; Theresa Howard-Carter, The tangible evidence for the earliest Dilmun, JCS, 33 (1981): 210-223; S.N.Kramer, Quest for Paradise, Antiquity, 37 (1963): 112-113)

On the northern coast of Bahrain, at Barbar, a Sumerian temple, which had been rebuilt three times was found. The dates for the contruction events are estimated to be: beginning of third millennium B.C., middle of the third millennium BC and for the third event, ca. 2200-2000 BC. In the first temple there were two staircases descending to a square well. This was retained in all the three phases. Peder Mortensen suggested, based on the similarity with the Khafajah and al-'Uaid temples, that the temple was for goddess Ninhursag. The mother-goddess plays an important role in the Sumerian Dilmun myth, Enki and Ninhursag. (Peder Mortensen, Kuml 1956: 189-198, 1970: 385-398).

Indus valley type seals and cubical chert weights were found. (T.G. Bibby, Kuml 1970: 345-353; cf. Michael Roaf, Weights on the Dilmun standard, Iraq 44 (1982): 137:141). A bronze mirror handle was also found in the Barbar temple suggesting a link with the Kulli culture in South Baluchistan (N.Rao, Kuml 1969: 218-220). "....as far as the third millennium BC is concerned, the cultural relations with the early civilizations in the Indus valley and southern Iran seem to have been much more outspoken than those with Mesopotamia. (M.Tosi, Dilmun, Antiquity, 45 (1971): 21-25). Yet, as far as the early second millennium BC is concerned, a cultural setting has certainly been found within which the identification of Dilmun with Bahrain makes good sense... There is now wide agreement among most, but not all scholars, that from the middle of the third millennium BC, Magan and Meluhha are to be found east of Mesopotamia along the coast of the Arabian Gulf or the Arabian Sea, whereas later, from the middle of the secon dmillennium BC, Egypt, Nubia or Ethiopia must be considered. (I.J.Gelb, Makkan and Meluhha in Early Mesopotamian Sources, RA 64 (1970): 1-8; E. Sollberger, The Problem of Magan and Meluhha, Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology 8-9 (1968-69): 247-250; John Hansman, A Periplus of Magan and Meluhha, BOAS 36 (1973): 554-587; E.C.L. During Caspers and A. Govindakutty, R. Thapar's Dravidian Hypothesis for the Location of Meluhha, Dilmun and Makan, JESHO 21 (1978): 114-145.) The cuneiform texts certainly give the impression that at least originally they (Makan and Meluhha) were located in the same direction as Dilmun, but farther away-- and later, remembrance of this direction was demonstrably kept alive, which makes the matter rather complicated. Archaeologically it makes sense to speak of Bahrain as a station on the way to Magan and Meluhha if these two were located east of Bahrain, as the most important cultural relations of Bahrain were Indus and Iran rather than Egypt. The use of Indus measuring standards in Bahrain clearly testifies to this, and was taken for granted by the Mesopotamian traders... The most important suggestins that have been made for Magan are Makran on the Iranian coast, and the Oman peninsula. As copper has been found in the Oman, the latter possibility seems highly likely. This, however, has been questioned by W. Heimpel, according ot whom diorite statues of Naramsin and Gudea said to be made of stones from Magan cannot have come from Oman, because diorite stones big enough for these statues are reported not to exist in Oman. As a possible source he suggests a position 50 miles NNE of Bandar Abbas on the northern side of the Arabian Gulf. Meluhha is to be found along the coast of Baluchistan and the Indus valley.

"...there was a temple of Enzak, the god of Dilmun, on Failaka... it was Failaka that was Dilmun?...the so-called a_lik Dilmun, the sea-faring merchants of Ur... The returning merchants used to offer a share of their goods or a silver model of their boat to the temple of the goddess Ningal, and he texts tell about partnerships and the sharing of profit and losses in a way which would not fit such an easy travel as thaf from Ur to Failaka. The distance from Aba_da_n to Failaka is no more than 60 nautical miles (111 km.) and could hardly be considered a great enterprise... Another possibility would be to suggest that Dilmun was a designation not only of Bahrain, but also of other parts of the Arabian Gulf area, among which Failaka would be counted... Dilmun is likely to the name of a rather large geographical area, including Bahrain, Failaka, Tarut, and certain parts of the Arabian littoral (During Caspers and Govindakutty, JESHO 21 (1978): 130; cf. the map in D.O.Edzard and G.Farber, Repertoire Geographique des Textes Cuneiformes 2, Wiesbaden, 1974)..." (Bendt Alster, opcit., 1983, p. 41).

COMMON MOTIFS ON MESOPOTAMIAN CIVILIZATION AND SARASVATI SINDHU CIVILIZATION SEALS/TABLETS

The following seals of Mesopotamia contain features reminiscent of themes depicted on the seals of the Sarasvati Sindhu civilization. Typical motifs are: rows of animals, combat, antelope or tiger with head turned, woman with thighs spread out, circle-and-dot, one-horned bull, hare, plant, snake, bird, fish. All these motifs have been explained as related to metallic weapons, in the context of the decipherment of Indus script pictorials and signs. In the Mesopotamian motifs, there are clear images related to WEAPONS.

The only motif that is remarkably unique in Mesopotamian seals is the LION. Only a tiger motif appears on the seals of the Sarasvati Sindhu civilization. The closest to a lion motif is the bristled-hair (like a lion's mane) on the face of the three-faced, fully adorned, horned, seated person surrounded by animals and an inscription.

Beatrice Teissier, Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals: From the Marcopoli Collection, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1984.

![cylmarc313.jpg (12402 bytes)]() | ca. 3100-2900 BC; serpentine; cat. 313; top end converges into a squat perforated handle; pattern on stamp base of seal. Row of open double-lined lozenges with circle and dot motif in center. Circle and dot motif along upper and lower edge and on base of seal. |

![cylmarc343.jpg (8773 bytes)]() | ca. 2700-2200 BC; serpentine; cat. 343; a crossed lion and a bearded bull between a rampant gazelle and a bull (?). In the field: drill holes, curved shape resembling a pommel (handle ofsword). |

![cylmarc371.jpg (4394 bytes)]() | ca. 2000-1900 BC; serpentine; cat. 371; two figures stand beside an antelope and a bull. In the field: serpent,dagger, ball staff. In the sky: disc and crescent. |

![cylmarc375.jpg (4435 bytes)]() | ca. 2000-1900 BC; serpentine; cat. 375; two figures stand beside two rampant hares. In the field: schematic plant, star. |

![cylmarc379.jpg (4901 bytes)]() | ca. 2000-1900 BC; serpentine; cat. 379; a figure drives a spear into a lion attacking a bull. In the sky: bird, star, crescent. |

![cylmarc381.jpg (4282 bytes)]() | ca. 1900 BC; serpentine; cat. 381; two figures stand facing each other, holding a spear between them. Terminal: two schematic bull-men, snake. |

![cylmarc580.jpg (6741 bytes)]() | Mitannian seal; ca. 1450-1300 BC; pyro-phyllite; cat. 580; a kneeling figure grasps an antelope by the hind legs. A lion attacks the antelope from behind. In the sky: fish. |

![cylmarc581.jpg (10859 bytes)]() | Mitannian seal; ca. 1550-1350 BC; composition; cat. 581; two crossed bulls. Terminal: laticed panel. |

![cylmarc584.jpg (6673 bytes)]() | Mitannian seal; ca. 1500-1300 BC; chert; cat. 584; two figures stand grasping a tree between them. In the field: ball staff, drill hole. Terminal: fish, bull's head, drill hole above recumbent antelope and star. |

![cylmarc585.jpg (3918 bytes)]() | Mitannian seal; ca. 1500-1300 BC; hematite; cat. 585; two figures stand before a seated deity holding a triple lightning fork. In the field: incomplete ankh. In the sky: three stars. |

![cylmarc586.jpg (7467 bytes)]() | Mitannian seal; ca. 1500-1300 BC; hematite; cat. 586; a worshipper presents an antelope to a deity standing on a lion which it holds by a leash. A nude goddess with hands clasped under her breasts stands between them. In the field: bird. In the sky: two rosettes. Terminal: inscription. IS'KUR.MU-u-s.ur = Adad-sum-us.ur |

![cylmarc589.jpg (3988 bytes)]() | Mitannian seal; ca. 1500-1300 BC; hematite; cat. 589; a lion atacks an antelope. Recumbent antelope above the lion. In the field: animal head, fish. In the sky: winged sun disc, drill holes. |

![cylmarc630.jpg (4172 bytes)]() | Mitannian seal; ca. 1450-1300 BC; chert; cat. 630; animal row: two antelopes and a lion. In the sky: scorpion, drill hole. |

![cyluruk1.jpg (41782 bytes)]() | Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr seal; ca. 3200-3000 BC; serpentine; cat.1; boar and bull in procession; terminal: plant; heavily pitted surface beyond plant |

![cyluruk2.jpg (24589 bytes)]() | Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr seal; ca. 3200-3000 BC; talc; cat.2; two gazelles (?) with heads turned backward, an antelope, a recumbent antelope (?), with two smaller indistinguishable animals above; in the field: plant(?) |

![cyluruk3.jpg (18880 bytes)]() | Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr seal; ca. 3200-3000 (?) BC; marble; cat.3; loop bore; an antelope wiht two panchers, one with head turned. |

![cyluruk4.jpg (26806 bytes)]() | Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr seal; marble; ca. 3200-3000 BC; cat.4; surface divided into 3 panels, from l. to r.: (a) squatting figure with arms raised to pot, (b) squatting figure with arms raised to pot, second pot on ground, (c) two figures squat one behind the other with their arms raised before them. |

![cylmarc076.jpg (11395 bytes)]() | ca. 2334-2260 BC; serpentine; cat. 76; two groups in combat. a hero wearing a kilt and a conical cap wrestles with a lion attacking a bull. A urinating bull-man wrestles with a water-buffalo. |

![cylmarc077.jpg (12286 bytes)]() | ca, 2334-2260 BC (early); marble; cat. 77; a hero in combat with a urinating, human-headed bull. A similar bull with forelegs resting on a bush stands to one side. |

![cylmarc078.jpg (15587 bytes)]() | ca. 233-2220 BC (early-mature); serpentine; cat. 78; two kilted heroes, one wearing a feathered crown and other a chignon, grapple with a lion attacking a bull. In the field: a small naked bearded figure kneels facing right |

![cylmarc079.jpg (9374 bytes)]() | ca. 2254-2220 BC (mature); ceramic; cat. 79; two groups in combat. A naked, bearded hero wrestles with a water buffalo, and a bull-man wrestles with a lion. In the centre: inscription (unread). Appears to be recut. |

![cylmarc080.jpg (27809 bytes)]() | ca. 2334-2260 BC (Early); serpentine; cat. 80; six dieties in combat in groups of two. A deity with rays issuing from the shoulders and holding a macesubdues a kneeling deity. A third deity with a mace grapples with a deity also armed with a mace. A fifth deity with a mace clutches an unarmed deity. In the field: mountain. |

![cylmarc081.jpg (10269 bytes)]() | ca. 2334-2220 BC (early-mature); serpentine; cat. 81; a deity with rays issuing from the shoulders and holding a saw (?) and a mace ascends a mountain. A worshipper carrying a kid salutes a deity opening a portal to the ascending deity. |