http://tinyurl.com/yytexgqb

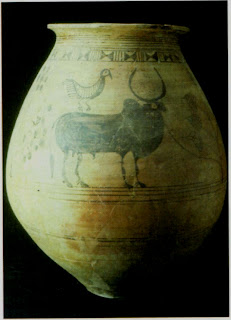

Zebu, National Museum, New Delhi Terracotta ca. 2500 BCE 16x6x8 cm Handmade with cream slip on it.Around the neck is a plaited rope or garland.

meḍhi 'plait' rebus: meḍ '

(Deśīnāmamālā)

mũh 'face' (Santali). Rebus: mũh metal ingot (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each end; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽtko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali.lex.)

Wilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:

Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.

Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'.

~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).

Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.

Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.

KW <i>mENhEd</i>

@(V168,M080)

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

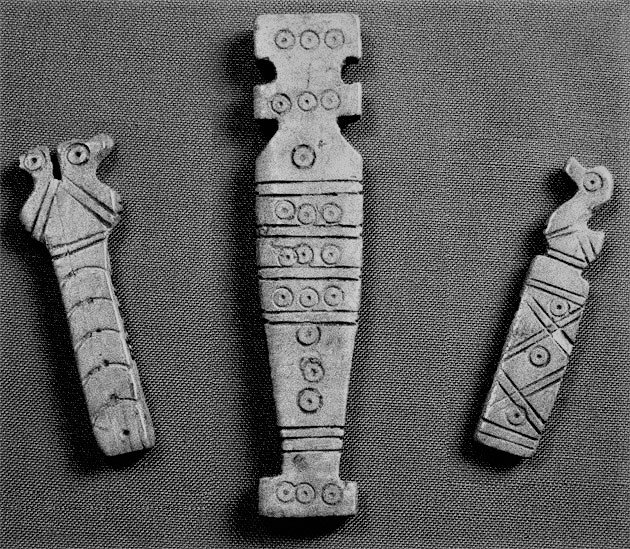

Rojdi. Ax-head or knife of copper, 17.4 cm. long (After Possehl and Raval 1989: 162, fig. 77. The endless knot hieroglyph on the copper knife indicates that the alloying element is: red ore of copper:

m1356, m443 table मेढा [ mēḍhā ] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl.(Marathi) mer.ha = twisted, crumpled, as a horn (Santali.lex.) meli, melika = a turn, a twist, a loop, entanglement; meliyu, melivad.u, meligonu = to get twisted or entwined (Te.lex.) [Note the endless knot motif]. Rebus: med. ‘iron’ (Mu.) Rebus: medh 'yajna' sattva 'svastika glyph' Rebus: sattva, jasta 'zinc'.

m1356, m443 table मेढा [ mēḍhā ] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl.(Marathi) mer.ha = twisted, crumpled, as a horn (Santali.lex.) meli, melika = a turn, a twist, a loop, entanglement; meliyu, melivad.u, meligonu = to get twisted or entwined (Te.lex.) [Note the endless knot motif]. Rebus: med. ‘iron’ (Mu.) Rebus: medh 'yajna' sattva 'svastika glyph' Rebus: sattva, jasta 'zinc'.The set of hieroglyphs deciphered as: 1. zinc-pewter and 2. bronze:1. jasta, sattva and 2. kuṭila

Hieroglyph: sattva 'svastika hieroglyph'; j̈asta, dasta 'five' (Kafiri) Rebus: jasta, sattva 'zinc'

Hieroglyph: kuṛuk 'coil' Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) cf. āra-kūṭa, '

Ext. in H. kuṛuk f. ʻ coil of string or rope ʼ; M. kuḍċā m. ʻ palm contracted and hollowed ʼ, kuḍapṇẽ ʻ to curl over, crisp, contract ʼ. (CDIAL 3230)

Pa. kuṭila -- ʻ bent ʼ, n. ʻ bend ʼ; Pk. kuḍila -- ʻ crooked ʼ, °illa -- ʻ humpbacked ʼ, °illaya -- ʻ bent ʼ(CDIAL 3231)

The Shahdad standard has the 'twisted strand' hieroglyph together with tree, zebu, lion, woman. kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite' arye 'lion' rebus: Ara 'brass' meD 'twist' rebus: meD 'iron, copper, metal'. kola 'woman' rebus: kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'.

The Shahdad standard has the 'twisted strand' hieroglyph together with tree, zebu, lion, woman. kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite' arye 'lion' rebus: Ara 'brass' meD 'twist' rebus: meD 'iron, copper, metal'. kola 'woman' rebus: kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'.kuṭi ‘tree’. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter’ (Santali). The two trees are shown ligatured to a rectangle with ten square divisions and a dot in each square. The dot may denote an ingot in a furnace mould.

Glyph of rectangle with divisions: baṭai = to divide, share (Santali) [Note the glyphs of nine rectangles divided.] Rebus: bhaṭa = an oven, kiln, furnace (Santali)

meṛhao = v.a.m. entwine itself; wind round, wrap round roll up (Santali); maṛhnā cover, encase (Hindi) (Santali.lex.Bodding) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Mu.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) mẽṛhẽt ‘iron’; mẽṛhẽt icena ‘the iron is rusty’; ispat mẽṛhẽt ‘steel’, dul mẽṛhẽt ‘cast iron’;mẽṛhẽt khaṇḍa ‘iron implements’ (Santali) meḍ. (Ho.)(Santali.lex.Bodding) meṛed, mṛed, mṛdiron; enga meṛed soft iron; sanḍi meṛed hard iron; ispāt meṛed steel; dul meṛed cast iron; i meṛed rusty iron, also the iron of which weights are cast; bica meṛed iron extracted from stone ore; bali meṛed iron extracted from sand ore (Mu.lex.)

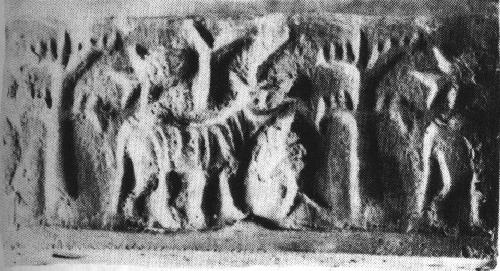

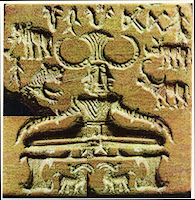

- Votive relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu, in the days of King Entemena of Lagash.

- Mésopotamie, room 1a: La Mésopotamie du Néolithique à l'époque des Dynasties archaïques de Sumer. Richelieu, ground floor.

- Votive bas-relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu in the time of Entemena, prince of Lagash C. 2400 BCE Tello (ancient Girsu) Bituminous stone H. 25 cm; W. 23 cm; Th. 8 cm De Sarzec excavations, 1881 AO 2354

This work is part of the collections of the Louvre (Department of Near Eastern Antiquities).Louvre Museum: excavated by Ernest de Sarzec. Place: Girsu (modern city of Telloh, Iraq). Musée du Louvre, Atlas database: entry 11378 Votive relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu, in the days of King Entemena of Lagash. Oil shale, ca. 2400 BC. Found in Telloh, ancient city of Girsu. |H. 25 cm (9 ¾ in.), W. 23 cm (9 in.), D. 8 cm (3 in.)- Hieroglyph: dhAu 'rope strand' Rebus: dhAtu 'mineral element' Alternative: मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' (Marathi) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) rebus: medha 'yajna' eruvai 'eagle' Rebus: eruvai 'copper'.

- eraka 'wing' Rebus: erako 'moltencast copper'.

- Hieroglyph: arye 'lion' (Akkadian) Rebus: Ara 'brass'Hieroglyph: dām m. ʻ young ungelt ox ʼ: damya ʻ tameable ʼ, m. ʻ young bullock to be tamed ʼ Mn. [~ *

dāmiya -- . -- √dam ]Pa. damma -- ʻ to be tamed (esp. of a young bullock) ʼ; Pk. damma -- ʻ to be tamed ʼ; S. ḍ̠amu ʻ tamed ʼ; -- ext. -- ḍa -- : A. damrā ʻ young bull ʼ, dāmuri ʻ calf ʼ; B.dāmṛā ʻ castrated bullock ʼ; Or. dāmaṛī ʻ heifer ʼ, dāmaṛiā ʻ bullcalf, young castrated bullock ʼ, dāmuṛ, °ṛi ʻ young bullock ʼ.Addenda: damya -- : WPah.kṭg. dām m. ʻ young ungelt ox ʼ.(CDIAL 6184). This is a phonetic determinative of the 'twisted rope' hieroglyph: dhāī˜ f.dāˊman1 ʻ rope ʼ (Rigveda)

Alternative: kōḍe, kōḍiya. [Tel.] n. A bullcalf. Rebus: koḍ artisan’s workshop (Kuwi) kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (Assamese) मेढा [ mēḍhā ] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl.(Marathi)(CDIAL 10312).L. meṛh f. ʻrope tying oxen to each other and to post on threshing floorʼ(CDIAL 10317) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)

Hieroglyph: endless knot motif

Hieroglyph: 'kid': करडूं or करडें (p. 137) [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं ) A kid. Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c.(Marathi)

![]()

![Shrine of the Double Headed Eagle, Buddhist ruins of Sirkap in Punjab Province, Pakistan Stock Photo]()

![]()

![Double-Headed Eagle Stupa, Sirkap, Taxila (UNESCO World Heritage List, 1980), Punjab, Pakistan, 2nd century BC : Stock Photo]()

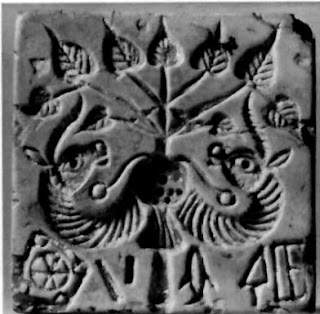

![Image result for shaft-hole axe bharatkalyan97]() On this artifact, eagle,sēṇa, کار کنده kār-kunda are Indus Script hypertexts,signify āhan gar, b'lacksmith', maker of asaṇi,vajrāśani thunderbolt weapon, manager of kiln. The pair of eagle-heads signify dula 'pair' rebus: dul'metal casting'. Thus,metal casting blacksmith. The winged tiger: kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'kolhe 'smelter' PLUS kambha 'wing' rebus: kammata 'mint'. baḍhia 'a castrated boar, a hog'(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar' Rebus: baḍhi 'worker in wood and iron' (Santali) bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) vāḍhī, 'one who helps a merchant. Thus, the hypertexts on the silver gold foil shaft-hole axe constitute metalwork catalogues.

On this artifact, eagle,sēṇa, کار کنده kār-kunda are Indus Script hypertexts,signify āhan gar, b'lacksmith', maker of asaṇi,vajrāśani thunderbolt weapon, manager of kiln. The pair of eagle-heads signify dula 'pair' rebus: dul'metal casting'. Thus,metal casting blacksmith. The winged tiger: kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'kolhe 'smelter' PLUS kambha 'wing' rebus: kammata 'mint'. baḍhia 'a castrated boar, a hog'(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar' Rebus: baḍhi 'worker in wood and iron' (Santali) bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) vāḍhī, 'one who helps a merchant. Thus, the hypertexts on the silver gold foil shaft-hole axe constitute metalwork catalogues.

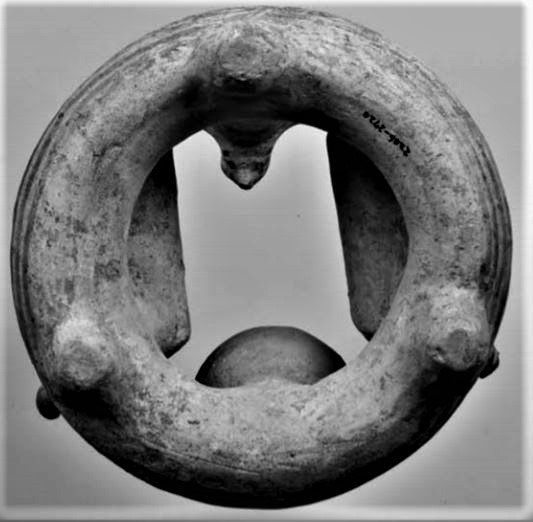

After Fig. 52, p.85 in Prudence Hopper opcit. Plaque with male figures, serpents and quadruped. Bitumen compound. H. 9 7/8 in (25 cm); w. 8 ½ in. (21.5 cm); d. 3 3/8 in. (8.5 cm). ca. 2600-2500 BCE. Acropole, temple of Ninhursag Sb 2724. The scene is described: “Two beardless, long-haired, nude male figures, their heads in profile and their bodies in three-quarter view, face the center of the composition…upper centre, where two intertwined serpents with their tails in their mouths appear above the upraised hands. At the base of the plaque, between the feet of the two figures, a small calf or lamb strides to the right. An irregular oblong cavity or break was made in the centre of the scene at a later date.”

The hieroglyphs on this plaque are: kid and endless-knot motif (or three strands of rope twisted).

I suggest that the center of the composition is NOT set of intertwined serpents, but an endless knot motif signifying a coiled rope being twisted from three strands of fibre.

Bogazkoy Seal impression: Two-headed eagle, a twisted cord below. From Bogazköy . 18th c. BCE (Museum Ankara). eruvai 'kite' Rebus: eruvai 'copper' dhAtu 'strands of rope' Rebus: dhAtu 'mineral' (Note the three strands of the rope hieroglyph on the seal impression from Bogazkoy; it is read: tridhAtu 'three mineral elements'). It signifies copper compound of three minerals; maybe, arsenic copper? or arsenic bronze, as distinct from tin bronze?

Eagle, श्येन sēṇa, کار کنده kār-kunda are Indus Script metalwork wealth मेधा 'yajña, धन' hypertexts, signify آهن ګر āhan gar, 'blacksmith', maker of asaṇi, vajrāśani thunderbolt weapon, manager of kiln

The sacred double-headed temple has a temple in Sirkap, Takṣaśila. The double-headed eagle is an Indus Script hypertext to signify kār-kunda, 'manager of kiln', āhan gar, 'blacksmith', maker of asaṇi, vajrāśani 'Indra's thunderbolt' signified by श्येन 'm. a hawk , falcon , eagle , any bird of prey (esp. the eagle that brings down सोम to man)' RV. &c. It is veneration of the thunderbolt maker, blacksmith, āhan gar -- an expression derived from श्येन 'hawk' 1) attested in R̥gveda. .श्येन is name of a ऋषि (having the patr. आग्नेय and author of RV. x , 188; and 2) double eagles celebrated in Rāmāyaṇa: सम्-पाति m. N. of a fabulous bird (the eldest son of अरुण or गरुड and brother of जटायु) MBh. R. &c and जटायु m. N. of the king of vultures (son of अरुण and श्येनी MBh. ; son of गरुड R. ; younger brother of सम्पाति ; promising his aid to राम , out of regard for his father दश-रथ , but defeated and mortally wounded by रावण on attempting to rescue सीता) MBh. i , 2634 ; iii , 16043ff. and 16242ff R. i , iii f.![Image result for meister shrine of eagle taxila]()

Shrine of Two Headed Eagle, 2nd cent.BCE

Double-Headed Eagle Stupa, Sirkap, Taxila (UNESCO World Heritage List, 1980), Punjab, Pakistan, 2nd century BCE

On this artifact, eagle,sēṇa, کار کنده kār-kunda are Indus Script hypertexts,signify āhan gar, b'lacksmith', maker of asaṇi,vajrāśani thunderbolt weapon, manager of kiln. The pair of eagle-heads signify dula 'pair' rebus: dul'metal casting'. Thus,metal casting blacksmith. The winged tiger: kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'kolhe 'smelter' PLUS kambha 'wing' rebus: kammata 'mint'. baḍhia 'a castrated boar, a hog'(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar' Rebus: baḍhi 'worker in wood and iron' (Santali) bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) vāḍhī, 'one who helps a merchant. Thus, the hypertexts on the silver gold foil shaft-hole axe constitute metalwork catalogues.

On this artifact, eagle,sēṇa, کار کنده kār-kunda are Indus Script hypertexts,signify āhan gar, b'lacksmith', maker of asaṇi,vajrāśani thunderbolt weapon, manager of kiln. The pair of eagle-heads signify dula 'pair' rebus: dul'metal casting'. Thus,metal casting blacksmith. The winged tiger: kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'kolhe 'smelter' PLUS kambha 'wing' rebus: kammata 'mint'. baḍhia 'a castrated boar, a hog'(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar' Rebus: baḍhi 'worker in wood and iron' (Santali) bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) vāḍhī, 'one who helps a merchant. Thus, the hypertexts on the silver gold foil shaft-hole axe constitute metalwork catalogues.![ahar14]()

![Image result for m1390Bt Text 2868 Pict-74: Bird in flight.m0451A,B Text3235 h166A, h166B Harappa Seal; Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255. Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7,8); eagle engraved on one. Seal impression. Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a lion striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255. Griffin, Baluchistan (Provenance unknown); ficus leaves, tiger, with a wing, ligatured to an eagle. The ligature on the Nal pot ca 2800 BCE(Balochistan: first settlement in southeastern Baluchistan was in the 4th millennium BCE) is extraordinary: an eagle's head is ligatured to the body of a tiger. In BMAC area, the 'eagle' is a recurrent motif on seals. Gold seal. Bactria. A winged person flanked by two heads of lions (a) obverse; (b) reverse. After Ligabue and Salvatgori n.d. (1989): figs. 58-9; cf. Asko Parpola, 1994, Fig. 14.29, p. 255.]() Sculptural frieze. stūpa of Sanchi, second half of 2nd century BCE (Kramrisch,1954, pic13)

Sculptural frieze. stūpa of Sanchi, second half of 2nd century BCE (Kramrisch,1954, pic13)

![Image result for eagle indus script]() Sanchi. Winged composite animal: tiger, eagle. The last two letters to the right of this inscription in Brahmi form the word "danam" (donation). This hypothesis permitted the decipherment of the Brahmi script by James Prinsep in 1837. The Indus Script hypertext of the composite animal:

Sanchi. Winged composite animal: tiger, eagle. The last two letters to the right of this inscription in Brahmi form the word "danam" (donation). This hypothesis permitted the decipherment of the Brahmi script by James Prinsep in 1837. The Indus Script hypertext of the composite animal:

Hierogoyph: hawk: śyēná m. ʻ hawk, falcon, eagle ʼ RV. Pa. sēna -- , °aka -- m. ʻ hawk ʼ, Pk. sēṇa -- m.; WPah.bhad. śeṇ ʻ kite ʼ; A. xen ʻ falcon, hawk ʼ, Or. seṇā, H. sen, sẽ m., M. śen m., śenī f. (< MIA. *senna -- ); Si. sen ʻ falcon, eagle, kite ʼ.(CDIAL 12674) Rebus: sena 'thunderbolt' (Sinhala)

Hieroglyph: wings: *skambha2 ʻ shoulder -- blade, wing, plumage ʼ. [Cf. *skapa -- s.v. *khavaka -- ]

S. khambhu, °bho m. ʻ plumage ʼ, khambhuṛi f. ʻ wing ʼ; L. khabbh m., mult. khambh m. ʻ shoulder -- blade, wing, feather ʼ, khet. khamb ʻ wing ʼ, mult. khambhaṛā m. ʻ fin ʼ; P. khambh m. ʻ wing, feather ʼ; G. khā̆m f., khabhɔ m. ʻ shoulder ʼ.(CDIAL 13640) Rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236)

Hieroglyph: tiger, feline paw: kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' PLUS panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja'kiln, furnace, smelter'. Thus, the hypertext reads: kol panja sena kammaṭa 'iron smelter thunderbolt mint.![]() Miraculous crossing of the Ganges by the Buddha when he left Rajagriha to visit Vaisali (partial remain). (John Marshall, A Guide to Sanchi, p. 38. Calcutta: Superintendent, Government Printing (1918), p.73).

Miraculous crossing of the Ganges by the Buddha when he left Rajagriha to visit Vaisali (partial remain). (John Marshall, A Guide to Sanchi, p. 38. Calcutta: Superintendent, Government Printing (1918), p.73).

Hieroglyph: pericarp of lotus: kárṇikā f. ʻ round protuberance ʼ Suśr., ʻ pericarp of a lotus ʼ MBh., ʻ ear -- ring ʼ Kathās. [kárṇa -- ] Pa. kaṇṇikā -- f. ʻ ear ornament, pericarp of lotus, corner of upper story, sheaf in form of a pinnacle ʼ; Pk. kaṇṇiā -- f. ʻ corner, pericarp of lotus ʼ; Paš. kanīˊ ʻ corner ʼ; S. kanī f. ʻ border ʼ, L. P. kannī f. (→ H. kannī f.); WPah. bhal. kanni f. ʻ yarn used for the border of cloth in weaving ʼ; B. kāṇī ʻ ornamental swelling out in a vessel ʼ, Or. kānī ʻ corner of a cloth ʼ; H. kaniyã̄ f. ʻ lap ʼ; G. kānī f. ʻ border of a garment tucked up ʼ; M. kānī f. ʻ loop of a tie -- rope ʼ; Si. käni, kän ʻ sheaf in the form of a pinnacle, housetop ʼ.(CDIAL 2849) rebus: supercargo: kāraṇika m. ʻ teacher ʼ MBh., ʻ judge ʼ Pañcat. [kā- raṇa -- ]Pa. usu -- kāraṇika -- m. ʻ arrow -- maker ʼ; Pk. kāraṇiya -- m. ʻ teacher of Nyāya ʼ; S. kāriṇī m. ʻ guardian, heir ʼ; N. kārani ʻ abettor in crime ʼ; M. kārṇī m. ʻ prime minister, supercargo of a ship ʼ, kul -- karṇī m. ʻ village accountant ʼ. (CDIAL 3058) Helmsman: कर्णिक m. a steersman W.; having a helm (Monier-Williams)

Hierogoyph: hawk: śyēná m. ʻ hawk, falcon, eagle ʼ RV. Pa. sēna -- , °aka -- m. ʻ hawk ʼ, Pk. sēṇa -- m.; WPah.bhad. śeṇ ʻ kite ʼ; A. xen ʻ falcon, hawk ʼ, Or. seṇā, H. sen, sẽ m., M. śen m., śenī f. (< MIA. *senna -- ); Si. sen ʻ falcon, eagle, kite ʼ.(CDIAL 12674) Rebus: sena 'thunderbolt' (Sinhala)

Sanchi. Winged composite animal: tiger, eagle. The last two letters to the right of this inscription in Brahmi form the word "danam" (donation). This hypothesis permitted the decipherment of the Brahmi script by James Prinsep in 1837. The Indus Script hypertext of the composite animal:

Sanchi. Winged composite animal: tiger, eagle. The last two letters to the right of this inscription in Brahmi form the word "danam" (donation). This hypothesis permitted the decipherment of the Brahmi script by James Prinsep in 1837. The Indus Script hypertext of the composite animal: Hieroglyph: wings: *skambha

S. khambhu, °bho m. ʻ plumage ʼ, khambhuṛi f. ʻ wing ʼ; L. khabbh m., mult. khambh m. ʻ shoulder -- blade, wing, feather ʼ, khet. khamb ʻ wing ʼ, mult. khambhaṛā m. ʻ fin ʼ; P. khambh m. ʻ wing, feather ʼ; G. khā̆m f., khabhɔ m. ʻ shoulder ʼ.(CDIAL 13640) Rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236)

Hieroglyph: tiger, feline paw: kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' PLUS panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja'kiln, furnace, smelter'. Thus, the hypertext reads: kol panja sena kammaṭa 'iron smelter thunderbolt mint.

Miraculous crossing of the Ganges by the Buddha when he left Rajagriha to visit Vaisali (partial remain). (John Marshall, A Guide to Sanchi, p. 38. Calcutta: Superintendent, Government Printing (1918), p.73).

Hierogoyph: hawk: śyēná m. ʻ hawk, falcon, eagle ʼ RV. Pa. sēna -- , °aka -- m. ʻ hawk ʼ, Pk. sēṇa -- m.; WPah.bhad. śeṇ ʻ kite ʼ; A. xen ʻ falcon, hawk ʼ, Or. seṇā, H. sen, sẽ m., M. śen m., śenī f. (< MIA. *senna -- ); Si. sen ʻ falcon, eagle, kite ʼ.(CDIAL 12674) Rebus: sena 'thunderbolt' (Sinhala)

Hieroglyph: धातु [p= 513,3] m. layer , stratum Ka1tyS3r. Kaus3. constituent part , ingredient (esp. [ and in RV. only] ifc. , where often = " fold " e.g. त्रि-ध्/आतु , threefold &c ; cf.त्रिविष्टि- , सप्त- , सु-) RV. TS. S3Br. &c (Monier-Williams) dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.).; S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)

Rebus: M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; (CDIAL 6773) धातु primary element of the earth i.e. metal , mineral, ore (esp. a mineral of a red colour) Mn. MBh. &c element of words i.e. grammatical or verbal root or stem Nir. Pra1t. MBh. &c (with the southern Buddhists धातु means either the 6 elements [see above] Dharmas. xxv ; or the 18 elementary spheres [धातु-लोक] ib. lviii ; or the ashes of the body , relics L. [cf. -गर्भ]) (Monier-Williams. Samskritam)

There are two Railway stations in India called Dharwad and Ib. Both are related to Prakritam words with the semantic significance: iron worker, iron ore.

dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ (Marathi)(CDIAL 6773).

Twisted rope as hieroglyph:

dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.) S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773 ) Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn.Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ)(CDIAL 6773).

dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ

The suffix -vaḍ is relatable to the semantics of vaTam ‘string’.(as may be seen in the expressions in vogue in Tamil) Thus, dhā̆vaḍ can be elaborated as a compound made of dhA PLUS vaTam, i.e. layers of minerals or elements in the smelting process.

அணிவடம் aṇi-vaṭam

, n. < vaṭa. 1. Cable, large rope, as for drawing a temple-car; கனமான கயிறு. வடமற்றது (நன். 219, மயிலை.). 2. Cord; தாம்பு. (சூடா.) 3. A loop of coir rope, used for climbing palm-trees; மரமேறவுதவுங் கயிறு. Loc. 4. Bowstring; வில்லின் நாணி. (பிங்.) 5. String of jewels; மணிவடம். வடங்கள் அசையும்படி உடுத்து(திருமுரு. 204, உரை). (சூடா.) 6. Strands of a garland; chains of a necklace; சரம். இடை மங்கை கொங்கைவடமலைய (அஷ்டப். திருவேங்கடத் தந். 39). 7. Arrangement; ஒழுங்கு. தொடங்கற் காலை வடம்படவிளங்கும் (ஞானா. 14, 41).

Twisted rope as hieroglyph:

dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.) S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773 ) Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn.Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ)(CDIAL 6773).

dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ

The suffix -vaḍ is relatable to the semantics of vaTam ‘string’.(as may be seen in the expressions in vogue in Tamil) Thus, dhā̆vaḍ can be elaborated as a compound made of dhA PLUS vaTam, i.e. layers of minerals or elements in the smelting process.

அணிவடம் aṇi-vaṭam

, n. < அணி- +. Ornamental string of jewels, necklace; கழுத் திலணியு மாலை.

அரைவடம் arai-vaṭam

, n. < id. +. String of beads round the waist, worn by little children; அரைச்சதங்கை.அரைவடங்கள் கட்டி (திருப்பு. 2).

ஈர்வடம் īr-vaṭam

, n. < ஈர்³ +. Rope made of the ribs of the palmyra leaf; பனை யீர்க்குக்கயிறு. (J.)

ஏகவடம் ēka-vaṭam

, n. < id. +. Necklace of a single string. See ஏகாவலி. பொங்கிள நாகமொரேகவடத்தோடு (தேவா. 350, 7)

கால்வடம் kāl-vaṭam

, n. < கால்¹ +. Foot- ornament strung with pearls; காலணிவகை. திருக்கால்வடமொன்றிற் கோத்த (S.I.I. ii, 397, 205).

சபவடம் capa-vaṭam

, n. < சபம்¹ +. String of beads for keeping count in prayer, rosary; செபமாலை. சபவடமும்வெண்ணூல் மார்பும் (திருவாலவா. 27, 51).

தாழ்வடம் tāḻ-vaṭam

, n. < id. +. 1. [M. tāḻvaṭam.] Necklace of pearls or beads; கழுத் தணி. தாவி றாழ்வடம்தயங்க (சீவக. 2426).

தேர்வடம் tēr-vaṭam

, n. < id. +. Cable, thick rope for drawing a car; தேரிழுத்தற்குரிய பெரிய கயிற்றுவடம்.மணலையு மேவுதேர்வட மாக்க லாம் (அருட்பா, vi, வயித்திய. 4).

வடம்¹ vaṭam, n. < vaṭa. 1. Cable, large rope, as for drawing a temple-car; கனமான கயிறு. வடமற்றது (நன். 219, மயிலை.). 2. Cord; தாம்பு. (சூடா.) 3. A loop of coir rope, used for climbing palm-trees; மரமேறவுதவுங் கயிறு. Loc. 4. Bowstring; வில்லின் நாணி. (பிங்.) 5. String of jewels; மணிவடம். வடங்கள் அசையும்படி உடுத்து(திருமுரு. 204, உரை). (சூடா.) 6. Strands of a garland; chains of a necklace; சரம். இடை மங்கை கொங்கைவடமலைய (அஷ்டப். திருவேங்கடத் தந். 39). 7. Arrangement; ஒழுங்கு. தொடங்கற் காலை வடம்படவிளங்கும் (ஞானா. 14, 41).

There are two Railway stations in India called Dharwad and Ib. Both are related to Prakritam words with the semantic significance: iron worker, iron ore.

dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ (Marathi)(CDIAL 6773)

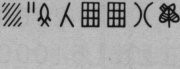

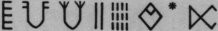

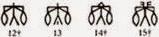

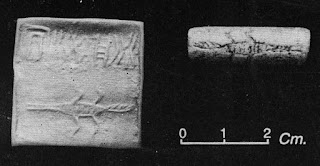

m478a tablet

m478a tablet m0478b tablet

m0478b tableterga = act of clearing jungle (Kui) [Note image showing two men carrying

uprooted trees] thwarted by a person in the middle with outstretched hands

Aḍaru twig; aḍiri small and thin branch of a tree; aḍari small branches (Ka.); aḍaru twig (Tu.)(DEDR 67). Aḍar = splinter (Santali); rebus: aduru = native metal (Ka.) Vikalpa: kūtī = bunch of twigs (Skt.) Rebus: kuṭhi = furnace (Santali) ḍhaṁkhara — m.n. ʻbranch without leaves or fruitʼ (Prakrit) (CDIAL 5524)

Hieroglyph: era female, applied to women only, and generally as a mark of respect, wife; hopon era a daughter; era hopon a man’s family; manjhi era the village chief’s wife; gosae era a female Santal deity; bud.hi era an old woman; era uru wife and children; nabi era a prophetess; diku era a Hindu woman (Santali)

•Rebus: er-r-a = red; eraka = copper (Ka.) erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Ka.lex.) erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) agasa_le, agasa_li, agasa_lava_d.u = a goldsmith (Te.lex.)

kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuṭhi = (smelter) furnace (Santali)

heraka = spy (Skt.); eraka, hero = a messenger; a spy (Gujarati); er to look at or for (Pkt.); er uk- to play 'peeping tom' (Ko.) Rebus: erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.) eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada)

kōṭu branch of tree, Rebus: खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge.

Hieroglyph: Looking back: krammara 'look back' (Telugu) kamar 'smith, artisan' (Santali)

kola ‘tiger, jackal’ (Kon.); rebus: kol working in iron, blacksmith, ‘alloy of five metals, panchaloha’ (Tamil) kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kolami ‘smithy’ (Telugu)

^ Inverted V, m478 (lid above rim of narrow-necked jar) The rimmed jar next to the tiger with turned head has a lid. Lid ‘ad.aren’; rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ karnika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karni 'supercargo' (Marathi) Thus, together, the jar with lid composite hieroglyhph denotes 'native metal supercargo'. karn.aka = handle of a vessel; ka_n.a_, kanna_ = rim, edge; kan.t.u = rim of a vessel; kan.t.ud.iyo = a small earthen vessel; kan.d.a kanka = rim of a water-pot; kan:kha, kankha = rim of a vessel

dhāu 'rope' rebus: dhāu 'metal' PLUS मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’. Thus, metallic ore.

kōlam, n. [T. kōlamu, K. kōla, M. kōlam.] 'ornamental figure' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'

The inscription on m478 thus signifies, reading hieroglyphs from r.:

Tree: kuThi 'smelter'

Worshipper: bhaTa 'furnace'

Four linear strokes + rimless pot: kanda baTa 'fire-altar for iron'

Circumscript two linear strokes + body: meD koDa 'metal workshop'

Currycomb:khareḍo 'currycomb' rebus: kharādī ‘turner’; dhāu 'metal'

PLUS mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’; kol 'working in iron'. Together, the two hieroglyphs

signify metalworker, ironsmith turner.

m479A eragu 'bow' rebus: erako 'moltencast, copper' baTa 'rimless pot' rebus: baTa 'iron' bhaTa 'furnace' kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, moltencast copper, iron furnace/smelter

m479A eragu 'bow' rebus: erako 'moltencast, copper' baTa 'rimless pot' rebus: baTa 'iron' bhaTa 'furnace' kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, moltencast copper, iron furnace/smeltergaNDa 'four' rebus: kaNDa 'implements' kanda 'fire-alter' baTa 'rimless pot' rebus: baTa 'iron' koDa 'one' rebus: koD 'workshop' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metalcasting' Thus, metalcasting workshop PLUS karNika 'spread legs' meD 'body' rebus: karNI 'supercargo''scribe, account' thus, account of metalcasting workshop (products)

khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ‘turner’ (Gujarati) kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa 'bronze' (Te.) dhāu 'rope' rebus: dhāu 'metal' PLUS मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’.

m479B kanka, karNaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' adaren 'lid' rebus: aduru 'native metal' Thus, native metal handed to supercargo for shipment. kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' krammara 'look back' rebus: kamar 'artisan, smith' heraka 'spy' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' Thus, copper smelter artisan. erga 'act of clearing jungle' rebus: erako 'moltencast copper'

m479B kanka, karNaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' adaren 'lid' rebus: aduru 'native metal' Thus, native metal handed to supercargo for shipment. kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' krammara 'look back' rebus: kamar 'artisan, smith' heraka 'spy' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' Thus, copper smelter artisan. erga 'act of clearing jungle' rebus: erako 'moltencast copper'Mohenjodaro, tablet in bas relief (M-478)

m0478B tablet erga = act of clearing jungle (Kui) [Note image showing two men carrying uprooted trees].

Aḍaru twig; aḍiri small and thin branch of a tree; aḍari small branches (Ka.); aḍaru twig (Tu.)(DEDR 67). Aḍar = splinter (Santali); rebus: aduru = native metal (Ka.) Vikalpa: kūtī = bunch of twigs (Skt.) Rebus: kuṭhi = furnace (Santali) ḍhaṁkhara — m.n. ʻbranch without leaves or fruitʼ (Prakrit) (CDIAL 5524)

•era, er-a = eraka = ?nave; erako_lu = the iron axle of a carriage (Ka.M.); cf. irasu (Ka.lex.)

•era_ = claws of an animal that can do no harm (G.)

•era female, applied to women only, and generally as a mark of respect, wife; hopon era a daughter; era hopon a man’s family; manjhi era the village chief’s wife; gosae era a female Santal deity; bud.hi era an old woman; era uru wife and children; nabi era a prophetess; diku era a Hindu woman (Santali)

•Rebus: er-r-a = red; eraka = copper (Ka.) erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Ka.lex.) erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) agasa_le, agasa_li, agasa_lava_d.u = a goldsmith (Te.lex.)

Hieroglyph: Looking back: krammara 'look back' (Telugu) kamar 'smith, artisan' (Santali)

erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.);

^ Inverted V, m478 (lid above rim of narrow-necked jar)

The rimmed jar next to the tiger with turned head has a lid. Lid ‘ad.aren’; rebus: aduru ‘native metal’

karnika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karni 'supercargo' (Marathi) Thus, together, the jar with lid composite hieroglyhph denotes 'native metal supercargo'.

kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuṭhi = (smelter) furnace (Santali)

eraka, hero = a messenger; a spy (G.lex.) kola ‘tiger, jackal’ (Kon.); rebus: kol working in iron, blacksmith, ‘alloy of five metals, panchaloha’ (Tamil) kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kolami ‘smithy’ (Te.) heraka = spy (Skt.); er to look at or for (Pkt.); er uk- to play 'peeping tom' (Ko.) Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Ka.) kōṭu branch of tree, Rebus: खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge.

karn.aka = handle of a vessel; ka_n.a_, kanna_ = rim, edge;

kan.t.u = rim of a vessel; kan.t.ud.iyo = a small earthen vessel

kan.d.a kanka = rim of a water-pot; kan:kha, kankha = rim of a vessel

svastika pewter (Kannada); jasta = zinc (Hindi) yasada (Jaina Pkt.)

karibha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' Rebus: karba 'iron' (Tulu)

kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron' krammara 'turn back' Rebus: kamar 'smith'

heraka 'spy' Rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper'

meDha 'ram' Rebus: meD 'iron' (Mu.Ho)

bAraNe ' an offering of food to a demon' (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi. Bengali) bhaTa 'worshipper' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' baTa 'iron' (Gujarati)

saman 'make an offering (Santali) samanon 'gold' (Santali)

minDAl 'markhor' (Torwali) meDho 'ram' (Gujarati)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: me~Rhet, meD 'iron' (Mu.Ho.Santali)

heraka 'spy' (Samskritam) Rebus:eraka 'molten metal, copper'

maNDa 'branch, twig' (Telugu) Rebus: maNDA 'warehouse, workshop' (Konkani)\karibha, jata kola Rebus: karba, ib, jasta, 'iron, zinc, metal (alloy of five metals)

maNDi 'kneeling position' Rebus: mADa 'shrine; mandil 'temple' (Santali)

The hieroglyphs on m478a tablet are read rebus:

kuTi 'tree'Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

bhaTa 'worshipper' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' baTa 'iron' (Gujarati) This hieroglyph is a phonetic deterinant of the 'rimless pot': baṭa = rimless pot (Kannada) Rebus: baṭa = a kind of iron (Gujarati) bhaṭa 'a furnace'. Hence, the hieroglyph-multiplex of an adorant with rimless pot signifies: 'iron furnace' bhaTa.

bAraNe ' an offering of food to a demon' (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi. Bengali) The narrative of a worshipper offering to a tree is thus interpretable as a smelting of three minerals: copper, zinc and tin.

Numeral four: gaNDa 'four' Rebus: kand 'fire-altar'; Four 'ones': koḍa ‘one’ (Santali) Rebus: koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop'. Thus, the pair of 'four linear strokes PLUS rimless pot' signifies: 'fire-altar (in) artisan's wrkshop'.

Circumscript of two linear strokes for 'body' hieroglyph: dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' koḍa ‘one’(Santali) Rebus: koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop'. Thus, the circumscript signifies 'cast metal workshop'. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'.

khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ‘turner’ (Gujarati)

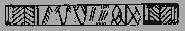

m1457A Copper tablet

m1457Bct Text 2904 Pict-124: Endless knot motif. The hypertext on two lines are read rebus:

Hieroglyph: मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' (Marathi) .L. meṛh f. ʻrope tying oxen to each other'.mer.ha = twisted, crumpled, as a horn (Santali.lex.) meli, melika = a turn, a twist, a loop, entanglement. Viewed as a string or strand of rope, the gloss is read rebus as dhāu ʻore (esp. of copper)ʼ. The specific ore is:

dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.) S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773 ) Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn.Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ)(CDIAL 6773).

Line 1: ad.ar 'harrow'; rebus: aduru 'native metal, unsmelted' (Kannada)

baTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

karNika 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo'; karNaka 'account'. Alternative: kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: kanga 'brazier'.

Line 2: ad.ar 'harrow'; rebus: aduru 'native metal, unsmelted' (Kannada)

aya 'fish' rebus: aya, ayas 'iron''metal'

dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS goTa 'round' rebus: goTa 'laterite ore'

Thus, the hieroglyph-multiplex signifies cast metal of laterite ore

mū̃h ‘ingot’ (Santali) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' Thus, cast metal ingot of laterite and implements.

Thus, the hieroglyph-multiplex signifies cast metal of laterite ore

pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali) Rebus: pasra 'smithy' (Santali) kolom,

Alternative: kolma 'rice plant' rebus: kolime 'furnace' (Kannada) kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Telugu); kolame 'deep pit' (Tulu)

Decipherment

Thus, read together with Lines 1 and 2 of Hypertext, the copper plate m1457 with the 'endless knot' hieroglyph signifies: copper smithy. The descriptive glosses of the metalwork catalogue are: karNi 'supercargo' of med 'copper', dhāu 'metal'; kolimi 'furnace'; dul goTa kaNDa 'cast laterite ore implements'; ayas 'metal alloy'; furnace for aduru 'native (unsmelted) metal'.

Alternative: kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: kanga 'brazier'.

Alternative: kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: kanga 'brazier'.

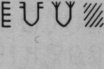

h613C dhāu 'rope' rebus: dhāu 'metal' PLUS मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’.

h613C dhāu 'rope' rebus: dhāu 'metal' PLUS मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’. 4259 ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' PLUS dhal 'slope' rebus: dhALako 'large ingot (oxhide)'.

4259 ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' PLUS dhal 'slope' rebus: dhALako 'large ingot (oxhide)'.Endless knot: Yajna, Iron Mineral smelter cluster

C-49 a,b,c

+ hieroglyph in the middle with covering lines around/dots in corners poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite'; dhAv 'strand' rebus: dhAv 'smelter'; kulA 'hooded snake' rebus: kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter'; kolmo 'three' koD 'horn' rebus: kolimi 'smithy' koD 'workshop'. tri-dhAtu 'three strands, threefold' rebus: tri-dhAv 'three mineral ores'.

mḗdha m. ʻ sacrificial oblation ʼ RV. Pa. mēdha -- m. ʻ sacrifice ʼ; Si. mehe, mē sb. ʻ eating ʼ ES 69.(CDIAL 10327).

Thus, mḗdha is a yajna. 1 ] fit for sacrifice, pure; neg. a˚ impure Sdhp 363. medha [Vedic medha, in aśva, go˚, puruṣa˚ etc.] sacrifice only in assa˚ horse -- sacrifice (Pali)

गृहम् gṛhamमेध a. 1 one who performs the domestic rites or sacrifices; गृह- मेधास आ गत मरुतो माप भूतन Rv.7.59.1.-2 connected with the duties of a householder. (-धः) 1 a householder. -2 a domestic sacrifice; मेधः 1 A sacrifice, as in नरमेध, अश्वमेध, एकविंशति- मेधान्ते Mb.14.29.18. (com. मेधो युद्धयज्ञः । 'यज्ञो वै मेधः'इति श्रुतेः ।). -2 A sacrificial animal or victim. -3 An offering, oblation. मेधा [मेध्-अञ्] (changed to मेधस् in Bah. comp. when preceded by सु, दुस् and the negative particle अ A sacrifice. -5 Strength, power (Ved.). मेध्य a. [मेध्-ण्यत्, मेधाय हितं यत् वा] 1 Fit for a sacrifice; अजाश्वयोर्मुखं मेध्यम् Y.1.194; Ms.5.54. -2 Relating to a sacrifice, sacrificial; मेध्येनाश्वेनेजे; R.13. 3; उषा वा अश्वस्य मेध्यस्य शिरः Bṛi. Up.1.1.1. -3 Pure, sacred, holy; भुवं कोष्णेन कुण्डोघ्नी मध्येनावमृथादपि R.1.84; 3.31;14.81 Mejjha (adj. -- nt.) [*medhya; fr. medha] 1. (adj.) [to medhaमेढा [ mēḍhā ]'twist, curl'

rebus: meD 'iron, copper,metal‘ medha ‘yajna

rebus: meD 'iron, copper,metal‘ medha ‘yajna

Fatehpur Sikri (1569-1584 CE cf. RS Bisht

Hieroglyph: Endless knot

dhAtu 'strand of rope' Rebus: dhAtu 'mineral, metal, ore'धातु [p= 513,3] m. layer , stratum Ka1tyS3r. Kaus3. constituent part , ingredient (esp. [ and in RV. only] ifc. , where often = " fold " e.g. त्रि-ध्/आतु , threefold &c ; cf.त्रिविष्टि- , सप्त- , सु-) RV. TS. S3Br. &c (Monier-Williams) dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.).; S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773) tántu m. ʻ thread, warp ʼ RV. [√

dhAtu 'strand of rope' Rebus: dhAtu 'mineral, metal, ore'धातु [p= 513,3] m. layer , stratum Ka1tyS3r. Kaus3. constituent part , ingredient (esp. [ and in RV. only] ifc. , where often = " fold " e.g. त्रि-ध्/आतु , threefold &c ; cf.त्रिविष्टि- , सप्त- , सु-) RV. TS. S3Br. &c (Monier-Williams) dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.).; S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773) tántu m. ʻ thread, warp ʼ RV. [√मेढा [ mēḍhā ] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl.(Marathi)(CDIAL 10312).L. meṛh f. ʻrope tying oxen to each other and to post on threshing floorʼ(CDIAL 10317) Rebus: meḍ'iron'. mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)

Thus, together, a strand and a curl, the hieroglyph-multiplex of endless-knot signifies iron mineral. mRdu dhAtu (iron mineral).

Bastar Gane gaṇeśa a wears a twisted chain, Chain link on two one-horned youngbulls

Mhttp://tinyurl.com/jmvqrtt

This note collates two hypertexts in Indus Script tradition: One is on a Mohenjo-daro seal m0296 (ca. 2500 BCE) which shows a link of a chain; and the other is on a sculpture of Gaṇeśa (ca 10th cent) shown wearing a chain, as a sacred thread. This collation is a demonstration of the metallurgical competence of the artisans of the civilization.

śã̄gaḍ, 'chain' signifies rebus sanghāta 'adamantine glue (calcine)'; kaṇḍe 'pine-cone' signified rebuskhaṇḍa '(metal) tools'. "Potential calcination is that brought about by potential fire, such as corrosive chemicals; for example, gold was calcined in a reverberatory furnace with mercury and sal ammoniac; silver with common salt and alkali salt; copper with salt and sulfur; iron with sal ammoniac and vinegar; tin with antimony; lead with sulfur; and mercury with aqua fortis". https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calcination"

Mirror: https://www.academia.edu/s/32bd84b1b4

There are two unique hieroglyphs on Gaṇeśa sculpture (h. 6 ft.) seated statue of Dholkal mountain, Bastar, Chattisgarh: The yajnopavitam worn by Gaṇeśa is a chain of three stranded metal chain (iron or steel) wires. Gaṇeśa carries on his left hand a pine cone.

There are two unique hieroglyphs on Gaṇeśa sculpture (h. 6 ft.) seated statue of Dholkal mountain, Bastar, Chattisgarh: The yajnopavitam worn by Gaṇeśa is a chain of three stranded metal chain (iron or steel) wires. Gaṇeśa carries on his left hand a pine cone.

Both hieroglyphs, together with the trunk of elephant in iconographs are related to metalwork catalogues of Indus Script corpora. Veneration of Gaṇeśa dates back to Rigvedic times (See RV 2.23 sukta gaṇānāṃ tvā gaṇapatiṃ havāmahe kaviṃ kavīnām upamaśravastamam -- with translation appended). In the tradition of Bharatam Janam, gana are related to kharva, dwarfs as part of Kubera's nidhi; rebus: karba 'iron'.

Gaṇeśa of Dholkal, Bastar is an emphatic evidence for the thesis of Sandhya Jain in her path-breaking monograph: 'Adi Deo Arya Devata- A Panoramic View of Tribal-Hindu Cultural Interface'. Gaṇeśa is a defining hieroglyph/metaphor of the cultural history of Bharatam Janam. (Bharatam janam, 'metalcaster folk', an expression defining the identity of Bharatiya by Rishi Viswamitra in RV 3.53.12).

Hieroglyph: kariba 'trunk of elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron.

Hieroglyph: dhāu 'strand of rope' Rebus: dhāv 'red ore' (ferrite) ti-dhāu 'three strands' Rebus: ti-dhāv 'three ferrite ores: magnetite, hematite, laterite'.

Hieroglyph: Ash. piċ -- kandə ʻ pine ʼ, Kt. pṳ̄ċi, piċi, Wg. puċ, püċ (pṳ̄ċ -- kəŕ ʻ pine -- cone ʼ), Pr. wyoċ, Shum. lyēwič (lyē -- ?).(CDIAL 8407). Cf. Gk. peu/kh f. ʻ pine ʼ, Lith. pušìs, OPruss. peuse NTS xiii 229. The suffix –kande in the lexeme: Ash. piċ-- kandə ʻ pine ʼ may be cognate with the bulbous glyphic related to a mangrove root: Koḍ. kaṇḍe root-stock from which small roots grow; ila·ti kaṇḍe sweet potato (ila·ti England). Tu. kaṇḍe, gaḍḍè a bulbous root; Ta. kaṇṭal mangrove, Rhizophora mucronata; dichotomous mangrove, Kandelia rheedii. Ma. kaṇṭa bulbous root as of lotus, plantain; point where branches and bunches grow out of the stem of a palm; kaṇṭal what is bulb-like, half-ripe jackfruit and other green fruits; R. candel. (DEDR 1171). Rebus: khaṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans of metal’.

Hieroglyph: కండె [ kaṇḍe ] kaṇḍe. [Telugu] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. జొన్నకంకి.

Rebus:Tu. kandůka, kandaka ditch, trench. Te. kandakamu id. Konḍa kanda trench made as a fireplace during weddings. Pe. kanda fire trench. Kui kanda small trench for fireplace. Malt. kandri a pit. (DEDR 1214).

Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/hyl57us

śã̄gal, śã̄gaḍ ʻchainʼ (WPah.) śr̥ṅkhala m.n. ʻ chain ʼ MārkP., °lā -- f. VarBr̥S., śr̥ṅkhalaka -- m. ʻ chain ʼ MW., ʻ chained camel ʼ Pāṇ. [Similar ending inmḗkhalā -- ] Pa. saṅkhalā -- , °likā -- f. ʻ chain ʼ; Pk. saṁkala -- m.n., °lā -- , °lī -- , °liā -- , saṁkhalā -- , siṁkh°, siṁkalā -- f. ʻ chain ʼ, siṁkhala -- n. ʻ anklet ʼ; Sh. šăṅāli̯ f., (Lor.)š*l ṅāli, ši ṅ° ʻ chain ʼ (lw .with š -- < śr̥ -- ), K. hö̃kal f.; S. saṅgharu m. ʻ bell round animal's neck ʼ, °ra f. ʻ chain, necklace ʼ, saṅghāra f. ʻ chain, string of beads ʼ,saṅghirī f. ʻ necklace with double row of beads ʼ; L. saṅglī f. ʻ flock of bustard ʼ, awāṇ. saṅgul ʻ chain ʼ; P. saṅgal m. ʻ chain ʼ, ludh. suṅgal m.; WPah.bhal. śaṅgul m. ʻ chain with which a soothsayer strikes himself ʼ, śaṅgli f. ʻ chain ʼ, śiṅkhal f. ʻ railing round a cow -- stall ʼ, (Joshi) śã̄gaḷ ʻ door -- chain ʼ, jaun. śã̄gal, śã̄gaḍ ʻ chain ʼ; Ku. sã̄glo ʻ doorchain ʼ, gng. śāṅaw ʻ chain ʼ; N. sāṅlo ʻ chain ʼ, °li ʻ small do. ʼ, A. xikali, OB. siṅkala, B. sikal, sikli, chikal, chikli, (Chittagong) hĩol ODBL 454, Or.sāṅk(h)uḷā, °ḷi,

sāṅkoḷi, sikaḷā̆, °ḷi, sikuḷā, °ḷi; Bi. sīkaṛ ʻ chains for pulling harrow ʼ, Mth. sī˜kaṛ; Bhoj. sī˜kar, sĩkarī ʻ chain ʼ, OH. sāṁkaḍa, sīkaḍa m., H. sã̄kal, sã̄kar,°krī, saṅkal, °klī, sikal, sīkar, °krī f.; OG. sāṁkalu n., G. sã̄kaḷ, °kḷī f. ʻ chain ʼ, sã̄kḷũ n. ʻ wristlet ʼ; M. sã̄k(h)aḷ, sāk(h)aḷ, sã̄k(h)ḷī f. ʻ chain ʼ, Ko. sāṁkaḷ; Si. säkilla, hä°, ä° (st. °ili -- ) ʻ elephant chain ʼ.śr̥ṅkhalayati. Addenda: śr̥ṅkhala -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) śáṅgəḷ f. (obl. -- i ) ʻ chain ʼ, J. śã̄gaḷ f., Garh. sã̄gaḷ.śr̥ṅkhalayati ʻ enchains ʼ Daś. [śr̥ṅkhala -- ]

śã̄gal, śã̄gaḍ ʻchainʼ (WPah.) śr̥ṅkhala m.n. ʻ chain ʼ MārkP., °lā -- f. VarBr̥S., śr̥ṅkhalaka -- m. ʻ chain ʼ MW., ʻ chained camel ʼ Pāṇ. [Similar ending in

sāṅkoḷi, sikaḷā̆, °ḷi, sikuḷā, °ḷi; Bi. sīkaṛ ʻ chains for pulling harrow ʼ, Mth. sī˜kaṛ; Bhoj. sī˜kar, sĩkarī ʻ chain ʼ, OH. sāṁkaḍa, sīkaḍa m., H. sã̄kal, sã̄kar,°krī, saṅkal, °klī, sikal, sīkar, °krī f.; OG. sāṁkalu n., G. sã̄kaḷ, °kḷī f. ʻ chain ʼ, sã̄kḷũ n. ʻ wristlet ʼ; M. sã̄k(h)aḷ, sāk(h)aḷ, sã̄k(h)ḷī f. ʻ chain ʼ, Ko. sāṁkaḷ; Si. säkilla, hä°, ä° (st. °ili -- ) ʻ elephant chain ʼ.

Ku.gng. śāṅaī ʻ intertwining of legs in wrestling ʼ (< śr̥ṅkhalita -- ); Or. sāṅkuḷibā ʻ to enchain ʼ.(CDIAL 12580, 12581)சங்கிலி¹ caṅkili , n. < šṛṅkhalaā. [M. caṅ- kala.] 1. Chain, link; தொடர். சங்கிலிபோ லீர்ப்புண்டு (சேதுபு. அகத். 12). 2. Land-measuring chain, Gunter's chain 22 yards long; அளவுச் சங்கிலி. (C. G .) 3. A superficial measure of dry land=3.64 acres; ஓர் நிலவளவு. (G. T n. D. I , 239). 4. A chain-ornament of gold, inset with diamonds; வயிரச்சங்கிலி என்னும் அணி. சங்கிலி நுண்டொடர் (சிலப். 6, 99). 5. Hand-cuffs, fetters; விலங்கு.

Rebus: Vajra Sanghāta 'binding together': Mixture of 8 lead, 2 bell-metal, 1 iron rust constitute adamantine glue. (Allograph) Hieroglyph: sãghāṛɔ 'lathe'.(Gujarati)

Seal m0296 Two heads of young bulls, nine ficus leaves)

m0296 Two heads of one-horned bulls with neck-rings, joined end to end (to a standard device with two rings coming out of the top part?), under a stylized pipal tree with nine leaves. Text 1387

![]() Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa‘arrow’; rebus: ayaskāṇḍa. The sign sequence is ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron,excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) ayo, hako 'fish'; a~s = scales of fish (Santali); rebus:aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) kaṇḍa‘fire-altar’ (Santali) DEDR 191 Ta. ayirai,acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitisthermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma. ayala a fish,mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind ofsmall fish, loach.

Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa‘arrow’; rebus: ayaskāṇḍa. The sign sequence is ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron,excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) ayo, hako 'fish'; a~s = scales of fish (Santali); rebus:aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) kaṇḍa‘fire-altar’ (Santali) DEDR 191 Ta. ayirai,acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitisthermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma. ayala a fish,mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind ofsmall fish, loach.![]() kole.l 'temple, smithy'(Ko.); kolme ‘smithy' (Ka.) kol ‘working in iron, blacksmith (Ta.); kollan-blacksmith (Ta.); kollan blacksmith, artificer (Ma.)(DEDR 2133) kolme =furnace (Ka.) kol = pan~calo_ha (fivemetals); kol metal (Ta.lex.) pan~caloha = a metallic alloy containing five metals: copper, brass, tin, lead and iron (Skt.); an alternative list of five metals: gold, silver, copper, tin (lead), and iron (dhātu; Nānārtharatnākara. 82; Man:garāja’s Nighaṇṭu. 498)(Ka.) kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, an aboriginal tribe if iron smelters speaking a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali)

kole.l 'temple, smithy'(Ko.); kolme ‘smithy' (Ka.) kol ‘working in iron, blacksmith (Ta.); kollan-blacksmith (Ta.); kollan blacksmith, artificer (Ma.)(DEDR 2133) kolme =furnace (Ka.) kol = pan~calo_ha (fivemetals); kol metal (Ta.lex.) pan~caloha = a metallic alloy containing five metals: copper, brass, tin, lead and iron (Skt.); an alternative list of five metals: gold, silver, copper, tin (lead), and iron (dhātu; Nānārtharatnākara. 82; Man:garāja’s Nighaṇṭu. 498)(Ka.) kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, an aboriginal tribe if iron smelters speaking a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali)

![]() dol = likeness, picture, form (Santali) [e.g., two tigers, two bulls, duplicated signs] me~ṛhe~t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Santali) [Thus, the paired glyph of one-horned heifers connotes (metal) casting (dul) workshop (koḍ)]

dol = likeness, picture, form (Santali) [e.g., two tigers, two bulls, duplicated signs] me~ṛhe~t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Santali) [Thus, the paired glyph of one-horned heifers connotes (metal) casting (dul) workshop (koḍ)]

Rebus: Vajra Sanghāta 'binding together': Mixture of 8 lead, 2 bell-metal, 1 iron rust constitute adamantine glue. (Allograph) Hieroglyph: sãghāṛɔ 'lathe'.(Gujarati)

Seal m0296 Two heads of young bulls, nine ficus leaves)

m0296 Two heads of one-horned bulls with neck-rings, joined end to end (to a standard device with two rings coming out of the top part?), under a stylized pipal tree with nine leaves. Text 1387

Mohenjo-daro Seal impression. m0296 Two heads of one-horned bulls with neck-rings, joined end to end (to a standard device with two rings coming out of the top part?), under a stylized tree-branch with nine leaves.

खोंद [ khōnda ] n A hump (on the back): also a protuberance or an incurvation (of a wall, a hedge, a road). Rebus: खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or -पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe.गोट [ gōṭa ] m (H) A metal wristlet. An ornament of women. 2 Encircling or investing. v घाल, दे. 3 An encampment or camp: also a division of a camp. 4 The hem or an appended border (of a garment).गोटा [ gōṭā ] m A roundish stone or pebble. 2 A marble (of stone, lac, wood &c.) 3 fig. A grain of rice in the ear. Ex. पावसानें भाताचे गोटे झडले. An overripe and rattling cocoanut: also such dry kernel detached from the shell. 5 A narrow fillet of brocade.गोटाळ [ gōṭāḷa ] a (गोटा) Abounding in pebbles--ground.गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A roundish stone or pebble. 2 A marble. 3 A large lifting stone. Used in trials of strength among the Athletæ. 4 A stone in temples described at length under उचला 5 fig. A term for a round, fleshy, well-filled body.

Rebus: गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe.

Hieroglyph: lo = nine (Santali); no = nine (B.) on-patu = nine (Ta.)

[Note the count of nine fig leaves on m0296] Rebus: loa = a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata,

the fruit of ficus glomerata (Santali.lex.)

the fruit of ficus glomerata (Santali.lex.)

corner (Santali); Rebus: kan~cu

= bronze (Te.)![]() Ligatured glyph. ara 'spoke' rebus: ara 'brass'. era, er-a = eraka =?nave; erako_lu = the iron axle of a carriage (Ka.M.); cf. irasu (Ka.lex.)[Note Sign 391 and its ligatures Signs 392 and 393 may connote a spoked-wheel,nave of the wheel through which the axle passes; cf. ara_, spoke]erka = ekke (Tbh.of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal);crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = anymetal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) Rebus: eraka= copper (Ka.)eruvai =copper (Ta.); ere - a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a= syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.)Vikalpa: ara, arā (RV.) = spokeof wheel ஆரம்² āram , n. < āra. 1. Spokeof a wheel.See ஆரக்கால். ஆரஞ்சூழ்ந்தவயில்வாய்

Ligatured glyph. ara 'spoke' rebus: ara 'brass'. era, er-a = eraka =?nave; erako_lu = the iron axle of a carriage (Ka.M.); cf. irasu (Ka.lex.)[Note Sign 391 and its ligatures Signs 392 and 393 may connote a spoked-wheel,nave of the wheel through which the axle passes; cf. ara_, spoke]erka = ekke (Tbh.of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal);crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = anymetal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) Rebus: eraka= copper (Ka.)eruvai =copper (Ta.); ere - a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a= syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.)Vikalpa: ara, arā (RV.) = spokeof wheel ஆரம்² āram , n. < āra. 1. Spokeof a wheel.See ஆரக்கால். ஆரஞ்சூழ்ந்தவயில்வாய்

= bronze (Te.)

Ligatured glyph. ara 'spoke' rebus: ara 'brass'. era, er-a = eraka =?nave; erako_lu = the iron axle of a carriage (Ka.M.); cf. irasu (Ka.lex.)[Note Sign 391 and its ligatures Signs 392 and 393 may connote a spoked-wheel,nave of the wheel through which the axle passes; cf. ara_, spoke]erka = ekke (Tbh.of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal);crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = anymetal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) Rebus: eraka= copper (Ka.)eruvai =copper (Ta.); ere - a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a= syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.)Vikalpa: ara, arā (RV.) = spokeof wheel ஆரம்² āram , n. < āra. 1. Spokeof a wheel.See ஆரக்கால். ஆரஞ்சூழ்ந்தவயில்வாய்

Ligatured glyph. ara 'spoke' rebus: ara 'brass'. era, er-a = eraka =?nave; erako_lu = the iron axle of a carriage (Ka.M.); cf. irasu (Ka.lex.)[Note Sign 391 and its ligatures Signs 392 and 393 may connote a spoked-wheel,nave of the wheel through which the axle passes; cf. ara_, spoke]erka = ekke (Tbh.of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal);crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = anymetal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) Rebus: eraka= copper (Ka.)eruvai =copper (Ta.); ere - a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a= syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.)Vikalpa: ara, arā (RV.) = spokeof wheel ஆரம்² āram , n. < āra. 1. Spokeof a wheel.See ஆரக்கால். ஆரஞ்சூழ்ந்தவயில்வாய்நேமியொடு (சிறுபாண். 253). Rebus: ஆரம் brass; பித்தளை.(அக. நி.) pittal is cognate with 'pewter'.

‘iron smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546)

Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa‘arrow’; rebus: ayaskāṇḍa. The sign sequence is ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron,excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) ayo, hako 'fish'; a~s = scales of fish (Santali); rebus:aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) kaṇḍa‘fire-altar’ (Santali) DEDR 191 Ta. ayirai,acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitisthermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma. ayala a fish,mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind ofsmall fish, loach.

Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa‘arrow’; rebus: ayaskāṇḍa. The sign sequence is ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron,excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) ayo, hako 'fish'; a~s = scales of fish (Santali); rebus:aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) kaṇḍa‘fire-altar’ (Santali) DEDR 191 Ta. ayirai,acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitisthermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma. ayala a fish,mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind ofsmall fish, loach. kole.l 'temple, smithy'(Ko.); kolme ‘smithy' (Ka.) kol ‘working in iron, blacksmith (Ta.); kollan-blacksmith (Ta.); kollan blacksmith, artificer (Ma.)(DEDR 2133) kolme =furnace (Ka.) kol = pan~calo_ha (five

kole.l 'temple, smithy'(Ko.); kolme ‘smithy' (Ka.) kol ‘working in iron, blacksmith (Ta.); kollan-blacksmith (Ta.); kollan blacksmith, artificer (Ma.)(DEDR 2133) kolme =furnace (Ka.) kol = pan~calo_ha (fivefront of the standard device and the stylized tree of 9 leaves, are the black

buck antelopes. Black paint on red ware of Kulli style. Mehi. Second-half of

3rd millennium BCE. [After G.L. Possehl, 1986, Kulli: an exploration of an

ancient civilization in South Asia, Centers of Civilization, I, Durham, NC:

46, fig. 18 (Mehi II.4.5), based on Stein 1931: pl. 30.

buck antelopes. Black paint on red ware of Kulli style. Mehi. Second-half of

3rd millennium BCE. [After G.L. Possehl, 1986, Kulli: an exploration of an

ancient civilization in South Asia, Centers of Civilization, I, Durham, NC:

46, fig. 18 (Mehi II.4.5), based on Stein 1931: pl. 30.

poLa 'zebu' rebus; poLa 'magnetite'

ayir = iron dust, any ore (Ma.) aduru = gan.iyindategadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to

melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddha_nti Subrahman.ya’ S’astri’s new interpretationof the Amarakos’a, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330) DEDR 192 Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir,ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native

metal. Tu. ajirdakarba very hard iron

melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddha_nti Subrahman.ya’ S’astri’s new interpretationof the Amarakos’a, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330) DEDR 192 Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir,ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native

metal. Tu. ajirdakarba very hard iron

loa = a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata, the fruit of ficus

glomerata (Santali.lex.) Vikalpa: kamaṛkom ‘ficus’ (Santali);

rebus: kampaṭṭam ‘mint’ (Ta.) patra ‘leaf’ (Skt.); rebus: paṭṭarai

‘workshop’ (Ta.) Rebus: lo ‘iron’ (Assamese, Bengali); loa ‘iron’ (Gypsy) lauha = made of

copper or iron (Gr.S'r.); metal, iron (Skt.); lo_haka_ra = coppersmith, ironsmith (Pali);lo_ha_ra = blacksmith (Pt.); lohal.a (Or.); lo_ha = metal, esp. copper or

bronze (Pali); copper (VS.); loho, lo_ = metal, ore, iron (Si.) loha lut.i = iron utensils and implements (Santali.lex.) koṭiyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; koṭ = neck (G.lex.) kōṭu = horns (Ta.) kōḍiya, kōḍe =

glomerata (Santali.lex.) Vikalpa: kamaṛkom ‘ficus’ (Santali);

rebus: kampaṭṭam ‘mint’ (Ta.) patra ‘leaf’ (Skt.); rebus: paṭṭarai

‘workshop’ (Ta.) Rebus: lo ‘iron’ (Assamese, Bengali); loa ‘iron’ (Gypsy) lauha = made of

copper or iron (Gr.S'r.); metal, iron (Skt.); lo_haka_ra = coppersmith, ironsmith (Pali);lo_ha_ra = blacksmith (Pt.); lohal.a (Or.); lo_ha = metal, esp. copper or

bronze (Pali); copper (VS.); loho, lo_ = metal, ore, iron (Si.) loha lut.i = iron utensils and implements (Santali.lex.) koṭiyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; koṭ = neck (G.lex.) kōṭu = horns (Ta.) kōḍiya, kōḍe =

young bull (G.) Rebus: koḍ = place where artisans work (G.lex.)

dol = likeness, picture, form (Santali) [e.g., two tigers, two bulls, duplicated signs] me~ṛhe~t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Santali) [Thus, the paired glyph of one-horned heifers connotes (metal) casting (dul) workshop (koḍ)]

dol = likeness, picture, form (Santali) [e.g., two tigers, two bulls, duplicated signs] me~ṛhe~t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Santali) [Thus, the paired glyph of one-horned heifers connotes (metal) casting (dul) workshop (koḍ)]PLUS

śã̄gaḍ ʻchainʼ rebus: sanghāta 'vajra, metallic adamantine glue'. Thus, the metallurgist has achieved and documented the alloy of copper, as adamantine glue. Decomposition of calcium carbonate (limestone) to calcium oxide (lime) and carbon dioxide, in order to create cement. The process is called calcination of metal which is oxidation of metal. It appears that the process of calcination is signified by the chain worn as sacred thread on the statue of Gaṇeśa of Bastar (Dholkal mountain), Chattisgarh.

Will Durant wrote in The Story of Civilization I: Our Oriental Heritage:The chain hieroglyph component is a semantic determinant of the stylized 'standard device' sã̄gaḍa, 'lathe, portable brazier' used for making, say, crucible steel. Hence the circle with dots or blobs/globules signifying ingots.

The pair of 'ovals or ellipses' are infixed with 'notches'. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implement'. dhal 'slope' rebus: dhALako 'large ingot (oxhide)' PLUS

The pair of 'ovals or ellipses' are infixed with 'notches'. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implement'. dhal 'slope' rebus: dhALako 'large ingot (oxhide)' PLUS

The hieroglyphs are:

The hieroglyphs are:

Harihara with dancing gaṇa.

Harihara with dancing gaṇa.

Parvati as Lalita carrying a bronze mirror, with her sons Ganesa and Skanda, Orissa. 11th cent. Now in British Museum. 1872.0701.54

Parvati as Lalita carrying a bronze mirror, with her sons Ganesa and Skanda, Orissa. 11th cent. Now in British Museum. 1872.0701.54

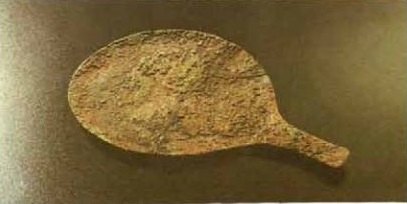

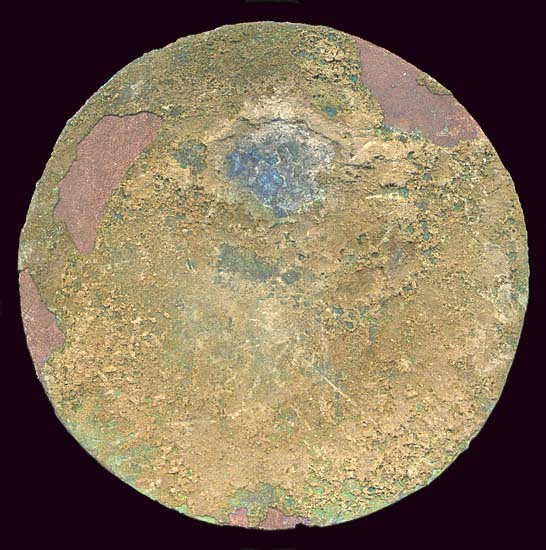

Bronze mirror. Dholavira. Courtesy: ASI

Bronze mirror. Dholavira. Courtesy: ASI

British Museum. Bronze mirror. ca. 300 BCE.

British Museum. Bronze mirror. ca. 300 BCE.

Nausharo. Pot.

Nausharo. Pot. A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE.

A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE.

kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Phonetic determinative)

kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Phonetic determinative)

m1118

m1118

Cylinder (white shell) seal impression; Ur, Mesopotamia (IM 8028); white shell. height 1.7 cm., dia. 0.9 cm.; cf. Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 7-8

Cylinder (white shell) seal impression; Ur, Mesopotamia (IM 8028); white shell. height 1.7 cm., dia. 0.9 cm.; cf. Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 7-8

Mohenjo-daro (?) seal.National Museum, Delhi.

Mohenjo-daro (?) seal.National Museum, Delhi.

Crucible steel button.

Crucible steel button.

Louvre Museum. Susa pot .Clay storage pot discovered in Susa (Acropole mound), ca. 2500-2400 BCE (h. 20 ¼ in. or 51 cm). Musee du Louvre. Sb 2723 bis (vers 2450 avant J.C.)Shows 'fish' + black drongo hieroglyphs to signify the contents: aya 'alloy metal, steel implements'. The lid is also a hypertext: ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebusdhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article' The hieroglyphs and Meluhha rebus readings on this pot from Meluhha are: 1. kāṇḍa 'water' rebus: khāṇḍā

Louvre Museum. Susa pot .Clay storage pot discovered in Susa (Acropole mound), ca. 2500-2400 BCE (h. 20 ¼ in. or 51 cm). Musee du Louvre. Sb 2723 bis (vers 2450 avant J.C.)Shows 'fish' + black drongo hieroglyphs to signify the contents: aya 'alloy metal, steel implements'. The lid is also a hypertext: ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebusdhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article' The hieroglyphs and Meluhha rebus readings on this pot from Meluhha are: 1. kāṇḍa 'water' rebus: khāṇḍā

Jiroft artifact. Two zebu PLUS twisted cord

Jiroft artifact. Two zebu PLUS twisted cord

The frieze is a proclamation of iron workings displayed on tablets atop haystacks by a scribe and merchants of Amaravati. The tablets with writing are atop haystacks. The messages are displayed by

The frieze is a proclamation of iron workings displayed on tablets atop haystacks by a scribe and merchants of Amaravati. The tablets with writing are atop haystacks. The messages are displayed by

Tell Asmar Cylinder seal modern impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] bibliography and image source: Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE. Imported Indian seal from Tell Asmar. "The Indus civilization used the signet, but knew the cylinder seal. Whether the five tall ivory cylinders [4] tentatively explained as seals in Sir John Marshall's work were used for that purpose remains uncertain. They have nothing in common with the seal cylinders of the Near East. In the upper layers of Mohenjo Daro, however, three cylinder seals were found [2,3]. The published specimen shows two animals with birds upon their backs [2], a snake and a small conventional tree. It is an inferior piece of work which displays none of the characteristics of the finely engraved stamp-seals which are so distinctive a feature of early Indian remains. Another cylinder of glazed steatite was discovered at Tell Asmar in Iraq, but here the peculiarities of design, as well as the subject, show such close resemblances to seals from the Indus valley that its Indian origin is certain [3]. The elephant, rhinoceros and crocodile (gharial), foreign to Babylonia, were obviously carved by an artist to whom they were familiar, as appears from the faithful rendering of the skin of the rhinoceros (closely resembling the plate-armour) and the sloping back and bulbous forehead of the elephant. Certain other peculiarities of style connect the seal as definitely with the Indus civilisation as if it actually bore the signs of the Indus script. Such is the convention by which the feet of the elephant are rendered and the network of lines, in other Indian seals mostly confined to the ears, but extending here over the whole of his head and trunk. The setting of the ears of the rhinoceros on two little stems is also a feature connecting this cylinder with the Indus valley seals." (H. Frankfort, Cylinder Seals, Macmillan and Co., 1939, p. 304-305.)

Tell Asmar Cylinder seal modern impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] bibliography and image source: Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE. Imported Indian seal from Tell Asmar. "The Indus civilization used the signet, but knew the cylinder seal. Whether the five tall ivory cylinders [4] tentatively explained as seals in Sir John Marshall's work were used for that purpose remains uncertain. They have nothing in common with the seal cylinders of the Near East. In the upper layers of Mohenjo Daro, however, three cylinder seals were found [2,3]. The published specimen shows two animals with birds upon their backs [2], a snake and a small conventional tree. It is an inferior piece of work which displays none of the characteristics of the finely engraved stamp-seals which are so distinctive a feature of early Indian remains. Another cylinder of glazed steatite was discovered at Tell Asmar in Iraq, but here the peculiarities of design, as well as the subject, show such close resemblances to seals from the Indus valley that its Indian origin is certain [3]. The elephant, rhinoceros and crocodile (gharial), foreign to Babylonia, were obviously carved by an artist to whom they were familiar, as appears from the faithful rendering of the skin of the rhinoceros (closely resembling the plate-armour) and the sloping back and bulbous forehead of the elephant. Certain other peculiarities of style connect the seal as definitely with the Indus civilisation as if it actually bore the signs of the Indus script. Such is the convention by which the feet of the elephant are rendered and the network of lines, in other Indian seals mostly confined to the ears, but extending here over the whole of his head and trunk. The setting of the ears of the rhinoceros on two little stems is also a feature connecting this cylinder with the Indus valley seals." (H. Frankfort, Cylinder Seals, Macmillan and Co., 1939, p. 304-305.)

The fillet worn on the forehead and on the right-shoulder signifies one strand; while the trefoil on the shawl signifies three strands. A hieroglyph for two strands is also signified.

The fillet worn on the forehead and on the right-shoulder signifies one strand; while the trefoil on the shawl signifies three strands. A hieroglyph for two strands is also signified.

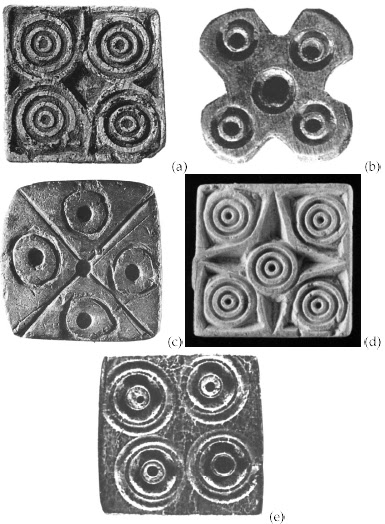

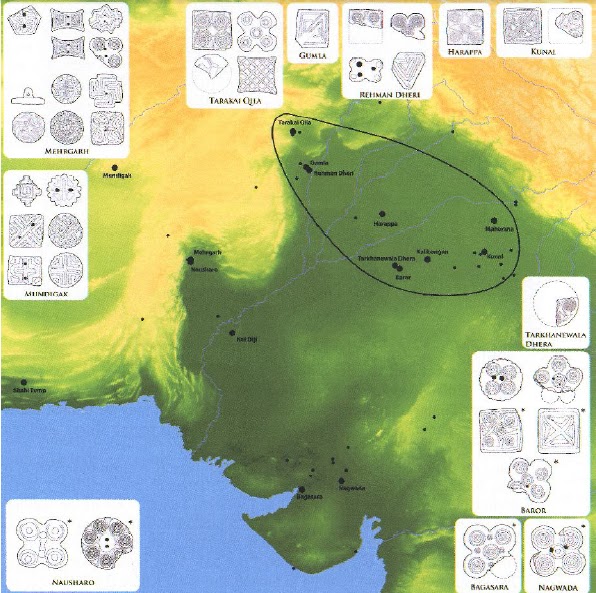

m1162. Mohenjo-daro seal with the same hieroglyph which appears on Kanmer circular tablets.

m1162. Mohenjo-daro seal with the same hieroglyph which appears on Kanmer circular tablets.

Hieroglyphs

Hieroglyphs

Harappa seal h166A, h166B. Vats, 1940, Excavations in Harappa, Vol. II, Calcutta: Pl. XCI. 255

Harappa seal h166A, h166B. Vats, 1940, Excavations in Harappa, Vol. II, Calcutta: Pl. XCI. 255

L

L

7 Hours ago