Svādhyāya: Studying our Holy Books -- Vishal Agarwal

Indology | From 25-12-2017 to 31-05-2018 Vishal Agarwal

The Hindu tradition lays great stress on the study of scriptures-svādhyāya. It is considered a religious duty for Hindus to study and recite their scriptures on a daily basis, if possible.

The Hindu tradition lays great stress on the study of scriptures. It is considered a religious duty for Hindus to study and recite their scriptures on a daily basis, if possible. In particular, Hindu priests are required to recite their own designated group of scriptures (called ‘svādhyāya’) every day, and even multiple times every day because that is what grants them the status of priesthood.

Shruti and Smriti are the two eyes of Brahmanas. He who is bereft of one is one eyed, and if bereft of both, is completely blind – thus it is said.” Vādhūla Smriti, verse 197

Hindu scriptures assign five great daily duties for all householders, and the very first one of them is the Brahmayajna, or the daily study and recitation of scriptures, in particular, the Vedas.

Lord Krishna enunciates the study of sacred scriptures as one of the 26 attributes of one who is endowed with divine wealth.

“Absence of fear, Purity of heart and Mind, Steadfastness in the path of Spiritual Wisdom, Charity, Control over one’s senses, Performance of Vedic sacrifices, Study of Holy Scriptures, Austerity and Straightforwardness” Gita 16.1

“Ahimsa, Truth, Absence of Anger, Renunciation, Peacefulness, Absence of Backbiting or Crookedness, Compassion towards all Creatures, Absence of Covetousness, Gentleness, Modesty (Decency), Absence of Fickleness (or immaturity).” Gita 16.2

“Vigor and Energy, Forgiveness, Fortitude, Cleanliness (external and internal), and Absence of too much pride – These belong to the One who is born to achieve Divine Wealth, O Bhārata!” Gita 16.3

Millions of Hindus recite ‘Om’, the Gayatri Mantra, the Purusha Sūkta (Rigveda 10.90), Stotras (hymns in praise of different deities), or sing devotional hymns, or study their holy books on a daily basis as an act of piety and to earn religious merit.

During the convocation ceremony, the Vedic teacher, therefore exhorts his student to continue studying and teaching the scriptures everyday even after they have graduated and have left the school. The Upanishad says that while performing various religious duties and practicing virtues, we must at all times continue svādhyāya and pravachana (teaching to others).

Righteousness, and study and teaching (are to be practiced). Truth (should be adhered to), and study and teaching (are to be practiced). Austerity, and study and teaching (are to be practiced). Control over senses, and study and teaching (are to be practiced). Control over the mind, and study and teaching (are to be practiced). The Vedic ceremonial fires (are to be kept lit), and learning and teaching (are to be practiced. The Agnihotra or Vedic twilight worship (is to be performed), and study and teaching (are to be practiced). The guests, scholars, and the needy (are to be served), and study and teaching (are to be practiced). Humans (should be served and interacted with appropriately), and study and learning (are to be practiced)…..Taittiriya Upanishad 1.9

Hindu scriptures themselves equate the study of scriptures to acts of worship, and the fruit of studying and reciting scriptures is said to be considerable. They say: They studied the Riks and thereby offered milk to the Devas. The Devas then manifested. With the study of Yajus, the Rishis made the offerings of clarified butter; with Samans, made an offering of Soma; with the Atharva Angiras, the made the offering of honey. With the study of Brahmanas, Itihāsa, Nārāshaṃsī, Gāthā, Kalpa and Purāṇa, they offered animal fat to the Devas. When the Devas manifested, they destroyed hunger and other evils, and then returned to heaven. By means of this Brahmayajna, the Rishis attained proximity to the Supreme Being. (Taittirīya Āraṇyaka 2.9.2)

If a twice born recites the Rigveda daily, he offers milk and honey (so to speak) to the Devas and honey and Ghee to his ancestors. If he studies the Yajurveda daily, he offers Ghee and water to the Devas, and Grains and honey to his ancestors. If he studies the Samaveda daily, he satisfies the Devas with Soma and Ghee, and satisfies his ancestors with honey and Ghee. If he studies the Atharvaveda daily, he offers butter to the Devas and honey and Ghee to the ancestors. He who studies the Vākovākya, Purāṇas, Nārashamsi (ballads), Gāthās, Itihāsas and different sciences offers meat, milk, honey and porridge to the ancestors. Satisfied with these offerings, the Devas and ancestors bestow desired fruits to the regular student of the scriptures. He who is ever devoted to the study of scriptures obtains the fruit of whatever yajna (Vedic religious ceremony) he performs, the fruit of donating the entire earth filled with treasures and food thrice, and obtains the fruit of performing numerous austerities. Yajnavalkya Smriti 1.41-48

Chanting the Scriptures:

This study of the sacred Hindu literature can occur in many ways –

1. Japa or chanting of ‘Om’ and selected passages (such as the Purusha Sūkta from the Rigveda), stotras (devotional hymns to various Deities) from holy books with attentiveness and reverence, and paying attention to the meaning and significance of the words recited. In most cases, the focus is on chanting as an act of devotion, without paying much attention to the meaning although the latter too is strongly recommended.

2. Svādhyāya: In ancient times (and to a limited extent even today), different families studied a specific set of scriptures from the entire corpus of Hindu sacred literature. For example, a family belonging to the Deshastha Brahmana community in Maharashtra (India) could chant a specific group of 10 scriptures related to the Rigveda (the Rigveda Samhitā, Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, Aitareya Āraṇyaka, Aitareya Upanishad, Āshvalāyana Shrauta Sūtra, Āshvalāyana Grhya Sūtra, Panini’s Așhtādhyāyī, Pingala’s Chhandasūtra, Yāska’s Nirukta and Kātyāyana’s Sarvānukramaṇī) during their lifelong study of scriptures. This same set of scriptures was studied by the members of the family as their primary focus generation after generation and constituted their traditional scriptural study or Svādhyāya. In this form of study too, the focus is on the recitation of the sacred texts, and not necessarily on their meaning.

3. Adhyayana or study of scriptures in general to imbibe their teachings, and reflect upon their meaning. There may or may not be any chanting involved. The student may study them privately, or under the guidance of a Guru.

The three terms are however used interchangeably. For example, the word ‘adhyayana’ is often used to denote the corpus of texts that are recited during ‘Svādhyāya’. Likewise, Japa is also often used to denote svādhyāya.

A lot of times, Hindus recite and study scriptures without reflecting upon their meaning. This method of reciting scriptural passages from memory mechanically as a ritualistic or a devotional act, without pondering over their meaning, is a good preliminary step towards studying them and acquiring familiarity with their contents. But we must not stop at that.

Importance of Knowing the Meaning of our Scriptures:

Hindu scriptures criticize those who merely chant the scriptures like parrots without trying to understanding their meaning. They say –

He, who having learned the Veda does not know its meaning is like a pillar which merely carries a burden, because only he who knows the meaning attains the auspiciousness and the holy, having got rid of all his sins through wisdom (contained in the meaning of the words).Sage Yāska’s Nirukta 1.18; Rigveda’s Shānkhāyana Āraṇyaka 14.2

An ignorant man has eyes to see but sees nothing, has ears to hear but hears nothing, has a tongue to speak but speaks nothing. The ignorant can never understand the hidden mysteries of knowledge. But it is to the learned alone that knowledge reveals its true nature, just as a woman longing to meet her husband, dresses in her best and puts on her finest jewelry, so as to display her charms to him. Rigveda 10.17.4

Only he who knows (and not merely recites) the Vedic mantras knows the Deities because the Deity does not accept the ceremonial offering that is made without knowledge. Rishi Shaunaka’s Brihaddevatā 7.130,132

Therefore, one must try to understand the meaning of scriptural passages too. But even and chanting and knowing the meaning of the scriptures is not sufficient. Hindu tradition states that the study of our holy books involves five activities:

Fivefold is the practice of Vedas: First is learning it from a teacher, second is contemplation, third is their practice (acting per their teachings and performing the rituals taught by them), fourth is their recitation (Japa) and the fifth is teaching them to one’s own disciple. Daksha Smriti 2.31

Knowledge is acquired and mastered in 4 steps – during the period of study, during the period of self-reflection on what is taught, during the period of teaching it to others, and while practicing it. Mahābhāshya of Patanjali

In other words, the learning of the letter and the meaning of scriptures must be followed by self-reflection, teaching it to others, and application of the teachings in our daily lives. The daily study of scriptures, and the performance of our daily duties are closely inter-related, and they illuminate and reinforce each other.

Benefits of Studying our Scriptures

1. Means of attaining all the goals of our Life

Hindu Dharma states that every human being should have four aims in life: Artha (material possessions), Kāma (gratification of senses), Dharma (piety, performing one’s duty) and Moksha (liberation from the cycle of births and deaths). These goals might seem mutually irreconcilable, but the scriptures provide ways and means and frameworks for our lives and the society so that all of them can be achieved in a harmonious manner.

With the eyes of knowledge, a wise man should closely examine all the sources of Dharma, and then determine and practice that Dharma which is in accordance with the Vedas. Manusmriti 2.8Following the Dharma taught in the Shruti and the Smriti, one obtains great fame in this life, and attains a state of great happiness upon death. Manusmriti 2.9 By Shruti is meant the Veda, and by Smriti is meant the Dharmashāstra. Dharma has originated from these two main sources, and therefore one should not find fault in them unnecessarily. Manusmriti 2.10 The four varnas, the three worlds, the four ashramas, the past, present and future are all known well through the Vedas alone. Manusmriti 12.97 The Vedas sustains all creatures and promotes their success/progress – therefore I consider the Vedas as the best means of attaining one’s goals. Manusmriti 12.99 |

“… A young man working in Indian Army could not find any meaning in life and so contemplated suicide while sitting on a bench at Delhi Railway Station. But, suddenly he remembered that his sister was to get married shortly. So, he decided to postpone his suicide mission until the marriage or his sister. Next day, he went to a book shop to purchase newspaper when he came across a book by Swami Vivekananda which contained many inspiring thoughts like – ‘This life is short, the vanities of the world are transient. They alone live who live for others; the rest are more dead than alive.’ He made up his mind to live for others. Afterwards he took premature retirement from Army and received Rs. 65,000/ – as retirement benefits. He went to his village in Maharashtra and utilized this money to repair the village temple. With the temple as the focal point, he mobilized public opinion and stopped all liquor outlets in the village despite stiff resistance from the vested interests. He educated the villagers, both young and old, and started many economic projects. In a few years, his village was declared an ideal village by the Government. The Maharashtra Government then released grant for transforming some more villages. The name of the village is Ralegaon Siddhi and the person’s name is Anna Hazare. He was awarded Padmasri and then Padma Bhushan for his work. Just a small book by Swami Vivekananda gave a new direction in Anna Hazare’s life.”[1] 2. Golden Standard for judging Good from Evil

Scriptures, and especially the Vedas, are the yardstick by which we measure the morality of our actions and judge whether we are right or wrong.

With the eyes of knowledge, a wise man should closely examine all the sources of Dharma, and then determine and practice that Dharma which is in accordance with the Vedas. Manusmriti 2.8By Shruti is meant the Veda, and by Smriti is meant the Dharmashāstra. Dharma has originated from these two main sources, and therefore one should not find fault in them unnecessarily. Manusmriti 2.10 |

In the Bhagavad Gita, Lord Krishna censures those persons who act without regard to scriptural directives:

He who, having cast aside the commandments of the scriptures, acts under the impulse of desire, attains neither spiritual powers, nor happiness, nor the Supreme Goal. Gita 16.23

Therefore, let the scriptures be your authority, in determining what should be done and what should not be done. You should perform your actions in this life only after knowing what is said in the commandments of the scripture. Gita 16.24 |

When we read our scriptures, we learn how we can live a virtuous life and why doing evil does not benefit us in the long run.

3. Provide Supra-sensuous Answers to difficult Questions about Life and Universe

Hindu Dharma seeks to address core questions related to our being – Who are we? What are we here for? Where do we go? What happens when we die? And so on. The answers to these questions are supra-sensuous, and cannot be determined through logical reasoning, or scientific experimentation. Hindus believe that our Holy books contain the wisdom of spiritually enlightened Rishis, Saints and Sages who had realized and understood these supra-sensuous or paranormal truths and therefore a study of these scriptures can help us answer our fundamental questions and doubts. In fact, Hindu schools of philosophy maintain that scriptures are the only perfect means of finding the true nature of Dharma and God because their true nature cannot be ascertained beyond doubt through other means such as perception by senses, or by logical inferences.

The Vedas are the eternal eye of the ancestors, devas and humans. Vedic teaching is beyond perception by senses and beyond logic – this is the established rule. Manusmriti 12.94Sense perception results when a person’s senses come into contact with an object that is present and can be perceived. But perception cannot be a means for knowing eternal Dharma because it is not a material object that can be perceived. On the contrary, the Vedas are an independent and infallible means of knowing imperceptible Dharma, and the relationship between the letters and meaning of Vedas is eternal – so says Bādarāyaṇa. Jaimini’s Pūrva Mimāmsā Sūtras 1.1.4-5 Brahman (Supreme Being) is not known from perception by senses or by logical inferences because he can be understood only through scriptures. Vedānta Sūtra 1.1.3 |

4. Collected Wisdom of Several Millennia

We can all eventually learn the principles of Physics, Chemistry etc. on our own if we spend ages trying to observe things first hand without the benefit of using any texts on these subjects or study under any teacher. But no one wastes time and energy in learning first hand through endless experimentation when one can conveniently learn from reliable books. Likewise, Hindus should consult and study the scriptures that contain collected wisdom on Dharma and Moksha instead of trying to figure it out again, and re-invent the wheel.

5. Substitute for other Dharmic Practices

Certain acts of Dharma such as charity, construction of temples, rituals and so on require wealth. So what should a poor person do? Hindu scriptures state that a person who is unable of performing rituals should still not abandon practices such as study and recitation of the Vedas.

Even if a Brahmana stops performing Vedic rituals, he should nevertheless exert to study the Vedas, acquire spiritual wisdom and control his senses. Manusmriti 12.92 |

6. Save us from Sins

Reflection upon and recitation of specific hymns from holy books helps us in reducing the burdens of our sins.

Regular study and recitation of scriptures, performance of the five great daily duties and forgiving others – these save a person from the greatest sins. Manusmriti 11.245 By studying the Rigveda, Yajurveda and Sāmaveda together with their Brāhmaṇas and Upanishads three times with a focused mind, one becomes free from all sins. Manusmriti 11.262 |

Good deeds to not necessarily cancel the results (or fruit) of bad deeds, and therefore, one must reap their fruits independently. However, there are a few good deeds that are exceptions and can cancel the results of bad deeds. Scriptural study is one of these exceptional good deeds.

Story: Ekanath’s son-in-law overcomes his bad habits with the help of Bhagavad Gita

![SvÄdhyÄya Sant Eknath Bhagavad Gita.jpg]() Sant Eknath was a renowned saint of Maharashtra. He married his daughter to a famous scholar (Pandit) of the region. Unfortunately, this scholar fell into bad company. He started going out of his home late in the night, leaving his wife alone. Eknath’s daughter became very worried about her husband’s behavior and she spoke to her father about it.

Sant Eknath was a renowned saint of Maharashtra. He married his daughter to a famous scholar (Pandit) of the region. Unfortunately, this scholar fell into bad company. He started going out of his home late in the night, leaving his wife alone. Eknath’s daughter became very worried about her husband’s behavior and she spoke to her father about it.Eknath then called his son in law and said, “Look here my son in law. You are a learned man, but my daughter is not. Do her a favor. Before you leave your home every night, please read to her a verse or two of the Bhagavad Gita. This will benefit her greatly. Then, you can go out wherever you please.” The Pandit agreed. So every night before he stepped out, he would read a couple of verses of the Bhagavad Gita to his wife, and explain the meaning to her. Slowly and slowly, the Pandit realized how beautiful the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita were. They started having an influence on how own mind. After some time, with the effect of the Gita, the Pandit stopped going out at the night. He had not intended to study the Gita for his own benefit. But nevertheless, the study of the holy book for the sake of his wife impacted him too in a positive way, and he became a virtuous man.

A traditional story is narrated from the times of the virtuous and scholarly king Raja Bhoja, who ruled central India in the 11th century CE. In his kingdom, there lived a virtuous Brahmana who was very learned in Hindu scriptures, but was very poor. The Brahmana was too proud to beg for food. But one day, he was so overcome by the hardships of poverty that he decided to rob Raja Bhoja’s palace.

He somehow entered the palace on a dark night, and reached the chamber in which the King was sleeping with his queen. Expensive jewels, gold jewelry and other costly items were scattered all across the room. The Brahmana could have stolen some of them, but just at that moment, he recalled the teachings of scriptures that one must not steal. Heeding the teaching, he refrained from the evil act. But now, he was realized that the sun was rising on the horizon and darkness was vanishing rapidly. There was no way he could free from the palace in daylight. Scared, he quickly hid under the bed of the King.

Soon thereafter royal attendants arrived to awaken the King and the Queen with song and music. The King got out of the bed in a good mood, and said three quarters of a verse that praised the joys and pleasures of his life.

When the Brahmana heard these words, he could not restrain himself and uttered the fourth quarter of the verse, “But none of these remain when the eyes are shut.”

Startled the King bent down and saw him. His guards rushed to arrest the Brahmana. The King asked him the reason for his hiding. The Brahmana narrated how he wanted to rob the palace but that he recalled the words of shāstras at that very moment and therefore stopped himself. The King was pleased to hear the truthful Brahmana and said, “Since you have practiced the teachings of our scriptures, I will not let you go away empty handed. You certainly seem to be a scholar because you completed my verse. And I value scholarship and give gifts to poets in my kingdom.” Saying this, Raja Bhoja ordered that the Brahmana be sent away with costly presents.[2] 7. Help us in knowing the truth about our multiple Lives

Hindus also believe that an intensive study of scriptures assists in recollection of our past lives. And when we learn about our former existences in different forms, we get less attached to this material world, and become inclined towards the path of spirituality, eventually resulting in Moksha.

Through constant study of the Vedas, austerities, purity (of mind and body) and absence of any hatred towards other creatures, a person comes to recollect his former lives. Recollecting one’s previous lives, such a person then becomes devoted to Brahman, and as a result, he attains the blissful state of Moksha. Manusmriti 4.148-149 |

When we remember our previous lives, we see the futility and the triviality of our current life in the larger scheme of things. And therefore, we start getting drawn towards the more real, and permanent entities, such as our soul, which survives multiple bodies; and God, who transcends the entire creation in space and time.

8. Provide a Starting Point for one’s Spiritual Journey

Reading scriptures is one of the means by which we can purify our bodies and minds, and make it a fit receptacle for spiritual enlightenment.

Practice of Tapas (austerity and forbearance), svādhyāya and Ishvara-prāṇidhāna (resigning oneself to God’s will, and offering him the fruits of all of one’s actions) are recommended as a starting point for those who desire to progress along the path of Yoga, but whose mind is unsteady…. svādhyāya means recitation of ‘Om’ and other sacred purifying scriptural statements, and study of spiritual scriptures.Patanjali’s Yogasūtra 2.1 and Vyāsa’s commentary on it (paraphrased) Through recitation of scriptures, performance of religious vows (vrata), performance of homa (daily Vedic ritual), study of the Vedas, daily offerings, birth of children, five great daily sacrifices and Vedic sacrifices, one’s body becomes Divine and holy. Manusmriti 2.28 |

Practice of Dharma does not necessarily have to involve grand and great deeds. One can do great deeds in a small way every day, and this is the basis of the performance of the five great daily sacrifices. Studying a portion of the scriptures every day is one of these five great daily sacrifices.

9. Assist Practice of Spiritual Disciplines such as Yoga

Study of scriptures has a synergistic relationship with the practice of Yoga and aids in attainment of Moksha-

The mind of the Yogi who constantly repeats ‘Om’, and reflects on its meaning and significance simultaneously becomes very focused and attentive. And so it has been said- “Let the Yoga be practiced through svādhyāya and let svādhyāya be facilitated through the practice of Yoga. By practicing Yoga and svādhyāya together, the Supreme Ātman (God) shines (in the heart of the Yogi).”Vyāsa’s commentary on Patanjali’s Yogasūtra 1.28 Rishis, Brahmanas and householders can enhance their wisdom and austerity, as well as purify their body by studying the Vedas and the Upanishads. Manusmriti 6.30 Study of the Vedas, austerity, spiritual enlightenment, control over one’s senses, service towards one’s Guru and Ahimsa, these six lead to the greatest good (Moksha). Manusmriti 12.83 |

10. Result in Spiritual Visions, help in Divine Interventions

Study of Scriptures is indeed known to be productive of good results. It gives one the peace of mind, and leads to a direct vision of the Devas.

The Devas, Rishis and Siddhas (spiritual masters) become visible to who is given to svādhyāya, and they assist him in his tasks. Vyāsa’s commentary on Patanjali’s Yogasūtra 2.44 |

Therefore, a regular study of scriptures accelerates our spiritual growth.

11. Beneficial effect on Minds and Body

The very act of recitation of Vedic scriptures is said to have a beneficial effect on our minds due to the combination of the sounds involved, and their soothing teachings. Study of scriptures gives peace to one’s mind and directs us towards the path of virtue and happiness.

He who studies all the Vedas is freed of all sorrows before long. He who practices purifying Dharma is worshipped in Heaven. Brihaspati Smriti 79 |

Therefore, in times of great sorrow (such as the death of a family member); it is a common Hindu practice to organize a public recitation and sermon of Hindu scriptures.

12. Means for Worshipping Rishis and Repaying our Debt to them

Hindu scriptures are a sacred inheritance of all human beings. They are the wisdom of the Rishis and have been passed on from generation to generation to our present times by a devoted and continuous string of teachers and students. Therefore it is our duty to continue the tradition of their study and teaching. Many saints and sages have recommended the study of scriptures and Hindus should feel obliged to follow their advice.

Hindu scriptures say that we are all born with a triple debt – the debt towards Devas, debt towards the Rishis and debt towards our elders. The debt towards Rishis is repaid only by reading the scriptures. Therefore, Hindu scriptures state that study and recitation of Vedas is a form of worshipping the Rishis themselves.

Do not neglect the study and teaching of scriptures. Taittiriya Upanishad 1.11.1 And for in as much as a person is bound to study the Veda, for that reason he is born with a debt owed to the Rishis. Therefore, he studies the Vedas to repay that debt, and one who has studies the Vedas is called the guardian of the treasure of Rishis. Shukla Yajurveda’s Mādhyandina Shatapatha Brāhmaṇa 1.7.2.3 Rishis are worshipped through svādhyāya. Manusmriti 3.81 |

13. Pleasing to the Lord

Hindu scriptures also state that recitation of the Vedas and other scriptures are pleasing to Lord Vishnu and other Deities, due to which their devotees should do the same regularly.

Story: Ravana chants the Samaveda to get his Freedom

When the arrogant Ravana tried to uproot and lift Mount Kailash (the abode of Shiva) in his hands, Shiva taught him a lesson by pressing the mountain with a toe and crushing Ravana below it. Ravana was trapped, and was not able to extricate himself out of the mountain. The Rishis advised him to chant the Samaveda, as Bhagavān Shiva loved to hear its chanting.

Ravana followed their advice and started chanting Mantras from the Samaveda. Soon, Shiva was pleased and He released Ravana from the mountain. Shiva also granted him a boon.

14. Teaching of Scriptures to Others earns Religious Merit

We should study our scriptures so that we can teach them to others. Teaching scriptures to others is an act of charity or gift, and in fact this gift is more exalted than many other forms of charity:

The gift of Vedic learning is the best of all gifts because the Vedas are the repository of all Dharma. The donor of Vedas dwells in Brahmaloka (the Supreme Abode) forever. Yājñavalkya Smriti 1.212 |

15. Non Religious Reasons for Studying Hindu Scriptures

It is fruitful to study Hindu scriptures for several other reasons:

§ The doctrines and logic of Pūrva Mimāmsā related scriptures are the basis of the Hindu personal law in India. Likewise, a study of the Nyāya Sūtras and other associated scriptures is beneficial for acquiring skills of logic and debating.

§ Hindu scriptures are amongst the oldest surviving and living religions traditions in the world. As such, a study of these texts is essential for understanding our past, and the development of religious ideas of the entire humanity as a whole.

§ Hindu scriptures can also be studied to gain insights into historical linguistics, history, and ancient mathematics, music, grammar etc.

§ Several Hindu scriptures are a delight to study from the perspective of appreciating good poetry.

§ There is an astonishing amount of information on medicine, statecraft etc., in Hindu scriptures and scholars are still unraveling bits of this knowledge.

John Hanning Speke, who discovered the source of the Nile river in Lake Victoria in 1862 CE, wrote “The Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile” a year later. In his Journal, the British explorer claims that he discovered the location of the source of the river in descriptions of the region in the Skanda Purāṇa, a Hindu scripture!

References

[1] Swami Nikhileshwarananda (2015), pp. 17-18 [2] Chaitanya and Chakra, pp. 662-663 Featured Image: Wikipedia

In this part we discuss the relative importance of scriptures vis-à-vis Dharma and Moksha.

Scriptures and Dharma- Their Relative Importance

With all the benefits of studying scriptures, it must be clarified that even the study and recitation of scriptures is no substitute for good conduct and pious living. One cannot wash his hands off goodness and perform evil actions thinking that his scriptural learning will save him.

The Vedas cannot help a man who does not have a virtuous conduct, even though he may have studied them together with the six Vedāngas. At the time of his death, the Vedas abandon such a man, just as birdlings fly out of their nest when they become adults.

Indeed, all the Vedas together with the Vedāngas and the Yajnas, can bring no joy to a man devoid of good conduct, just as a blind husband derives no joy on seeing his beautiful wife. Vasishtha Smriti 6.3-4

A Brahmana whose conduct is evil does not reap the fruit of Vedic study. Conversely, a Brahmana who shows appropriate conduct reaps the entire fruit of his Vedic study. Manusmriti 1.109

Study of scriptures is only one of the virtues of acts of Dharma. Dharma is much more than studying scriptures. They who are masters of scriptural learning but are evil in their conduct have merely wasted their time in studying the holy books. Therefore, scriptures are a means to knowing the difference between Dharma and Adharma, and not a substitute for practicing Dharma.

Scriptures and Moksha (The Final Goal) – Their Relative Importance

Hinduism also does not consider study of scriptures as the final goal. Unlike Abrahamic faiths, Hindus are not strictly a ‘book-religion’. Although long revelatory and other sacred texts exist in hundreds (‘Mahabharata’ in 100,000 verses is the longest poem in the world), they are merely considered as a guide to experience and realize the Supreme Reality, which is beyond all books and intellectual enterprise.

What good can the Vedas do unto him who does not know that Great Being, who is All-pervading and Eternal, Holiest of all, Who sustains the Sun and the Earth, and is the support of the learned, the method of Whose realization is the chief aim of Vedic teaching? But they alone enjoy eternal bliss who study the Vedas, live a righteous life, become perfect Yogis and realize God. Rigveda 1.164.39.

The purport of all Scriptures is Brahman (Supreme Being) indeed, and this is known when their passages are considered harmoniously. Vedānta Sūtra 1.1.4

After studying the scriptures, the wise person who is solely intent on acquiring spiritual knowledge and realization, should discard the scriptures together, just as a man who seeks to abandon rice discards the husk. Amritabindu Upanishad 18

As is the use of a pond in a place flooded with water, so is that of all Vedas for a Brahmana who is enlightened spiritually. Gita 2.46

The mere study of the letter of the scriptures does not have much benefit. One should first study the scriptures, try to understand their essence and finally practice the same to achieve the final goal of their teaching – spiritual realization. Moksha is the final goal of our life, and therefore also the final goal of scriptural study. If scriptural learning does not advance one’s understanding of God and lead us closer to Moksha, then it is of no use. And when the goal is achieved, the scriptures have no value left because the means of reaching the goal are of no further use once the goal itself is reached.

How to and How not to Study the Scriptures

As state above, a study of scriptures and following their teachings is a pre-requisite to advancing in Dharma and Moksha. However, many people study the scriptures with the wrong intentions, or they believe that they are very Dharmic and are entitled to Moksha just because they have mastered the scriptures. The following parables from the Hindu tradition teach the correct and the wrong ways of studying the holy books.

1. Live the Scriptures, do not just memorize their Words

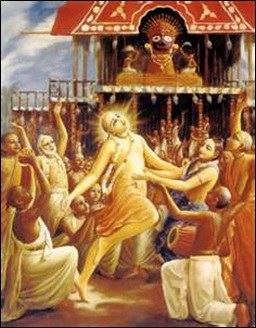

![Svadhaya 3 - 01]() Studying the scripture is not an end in itself. Once, a man came to Swami Chinmayananda and said, “I have gone through the Gita fifteen times.” Swami-ji asked, “But has the Gita gone through you even once?” The story below illustrates this message very aptly-

Studying the scripture is not an end in itself. Once, a man came to Swami Chinmayananda and said, “I have gone through the Gita fifteen times.” Swami-ji asked, “But has the Gita gone through you even once?” The story below illustrates this message very aptly-“While touring South India, Chaitanya encountered a certain Brahmin in the temple of Ranga-kshetra. This man daily sat in the temple turning over the pages of the Bhagavad-gita, but his constant mispronunciation of the Sanskrit made him the object of general mirth and derision. Chaitanya, however, observed signs of genuine spiritual ecstasy on the Brahmin’s body, and he asked him what he read in the Gita to induce such ecstasy. The Brahmin replied that he didn’t read anything. He was illiterate and could not understand Sanskrit. Nevertheless, his guru had ordered him to read the Gita daily, and he complied as best he could. He simply pictured Krishna and Arjuna together on the chariot, and this image of Krishna’s merciful dealings with his devotee caused this ecstasy. Chaitanya embraced the Brahmin and declared that he was an “authority on reading the Bhagavad-gita.”[1] 2. Do not study scriptures to show-off, but for self-transformation

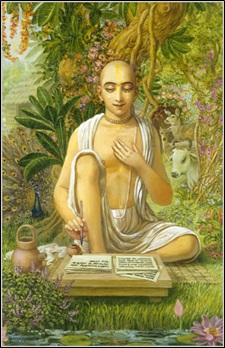

![Svadhaya 3 - 02]() The story of Vāmana Pandit below shows how mere learning of Gita and other scriptures does not benefit us spiritually. We become ‘alive’ only when we give up our ego and pride, when our heart is filled with devotion, and when we are able to teach the scriptures to the common man in a simple language out of love and compassion.

The story of Vāmana Pandit below shows how mere learning of Gita and other scriptures does not benefit us spiritually. We become ‘alive’ only when we give up our ego and pride, when our heart is filled with devotion, and when we are able to teach the scriptures to the common man in a simple language out of love and compassion.“Vāmana pandit was born in a Brahmin family of Bijapur, which was under Muslim rule. Even as a young boy he could compose Sanskrit verses. When the ruler Adil Shah heard of this child prodigy, he offered to support the boy, if he embraced Islam, so the family sent him secretly to Varanasi to study under some scholars. After studying there for about twenty years, Vāmana became quite famous for his knowledge and skill at debating. He used to go on tours and challenge other pandits to a debate. Hearing of Ramadasa, he decided to visit him and challenge him also to a debate. When he arrived near the place where Rāmadāsa was staying, Vāmana pandit sent a messenger to get Rāmadāsa. Vāmana waited and waited under a tree, but by midnight Rāmadāsa had still not come. At that time, he happened to see two ghosts, and overheard them talking about him. The ghosts were saying that Vāmana would soon be joining them. Vāmana pandit became very afraid. He thought about what the ghosts had said and gradually understood that his egotism and pride of scholarship was leading him to hell. In fact, he became so repentant that he decided he would approach Rāmadāsa for spiritual instructions.

Soon after, at dawn, Rāmadasa arrived and Vāmana pandit bowed down at his feet. Rāmadasa blessed the pandit and after giving him some spiritual instructions, told him to go to Badarika Ashrama, in the Himalayas, and meditate on Vishnu. After practicing sadhana whole-heartedly there for a long time, Vāmana pandit had a vision of the Lord, who blessed him and told him to go back to Rāmadāsa for further instructions. When Vamana pandit met Rāmadāsa again, Rāmadāsa gave him more instructions and told him to go to Shri Shaila Hill to meditate on Shiva. Again Vāmana did as he was told, practicing intense sādhanā for several years. Here also he was blessed by the Lord and told to return to Rāmadāsa. This time (in 1668 CE) Rāmadāsa described to the pandit how the common man needed religious education in their own language. Thus far the pundit had written only in Sanskrit. His learning was learning only among other Brahmin pundits like himself. It was of no use to ordinary people. So Rāmadāsa requested Vāmana pandit to write religious books in Marathi for the common people, and Vāmana agreed. Besides some very beautiful poems, Vāmana pundit also wrote a Marathi commentary on the Bhagavad-Gita, entitled Yathārtha Dīpikā.”[2] 3. There are no Short-Cuts to Studying the Scriptures, it takes Hard Work

![Svadhaya 3 - 03]() Sage Bharadvāja and his son Yavakrīta were neighbors of Sage Raibhya and his sons. The latter were all great scholars. Many people travelled long distances to study under Raibhya and his children. This made Yavakrīta jealous. But he did not like to study. So, he started praying to Lord Indra. Pleased with Yavakrīta’s penance, Lord Indra appeared in front of him and offered him a boon. Yavakrīta asked that he become a great scholar, so that people should come to study under him, just as they went to study under Raibhya and his scholarly sons.

Sage Bharadvāja and his son Yavakrīta were neighbors of Sage Raibhya and his sons. The latter were all great scholars. Many people travelled long distances to study under Raibhya and his children. This made Yavakrīta jealous. But he did not like to study. So, he started praying to Lord Indra. Pleased with Yavakrīta’s penance, Lord Indra appeared in front of him and offered him a boon. Yavakrīta asked that he become a great scholar, so that people should come to study under him, just as they went to study under Raibhya and his scholarly sons.But Indra replied, “If you want to become knowledgeable, you should focus on your studies, rather than trying to please me and get the boon of wisdom from me.”

But Yavakrīta would not listen. He resumed his austerities and penance, hoping that Indra would eventually get impressed and bless him with knowledge. One day, Yavakrīta went to the River Ganga to take a bath, when he noticed an old man throwing handfuls of sand into the river current. When Yavakrīta asked him the reason for doing so, the old man said, “People have a difficulty crossing the river. Therefore, I am constructing a bridge across it by throwing sand into the water.”

Yavakrīta was amused, and said, “But you cannot construct a bridge this way because the water will keep washing away the sand that you throw. Instead, you need to work harder and put in more effort and materials to construct the bridge.” The old man replied, “If you can become a scholar without studying, I too can construct a bridge with just handfuls of sand.”

Yavakrīta realized that it was Lord Indra who came disguised as the old man to teach him that worship alone cannot result in scholarship. He therefore apologized to Lord Indra and started studying diligently.

4. Scriptural Learning is not a Substitute for Practical Wisdom & Wisdom

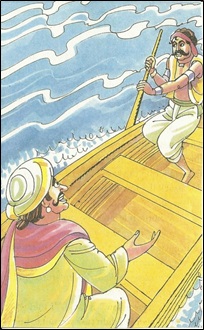

![Svadhaya 3 - 04]() “Once several men were crossing the Ganges in a boat. One of them, a Pandit, was making a great display of his erudition, saying that he had studied various books – the Vedas, the Vedanta, and the six systems of philosophy. He asked a fellow passenger, “Do you know the Vedanta?” “No, revered sir.” “The Samkhya and the Patanjala?” “No, revered sir.” “Have you read no philosophy whatsoever?” “No, revered sir.” The pandit was talking in this vain way and the passenger was sitting in silence when a great storm arose and the boat was about to sink. The passenger said to the pandit, “Sir, can you swim?” “No”, replied the pandit. The passenger said, “I don’t know Samkhya or the Patanjala, but I can swim.”

“Once several men were crossing the Ganges in a boat. One of them, a Pandit, was making a great display of his erudition, saying that he had studied various books – the Vedas, the Vedanta, and the six systems of philosophy. He asked a fellow passenger, “Do you know the Vedanta?” “No, revered sir.” “The Samkhya and the Patanjala?” “No, revered sir.” “Have you read no philosophy whatsoever?” “No, revered sir.” The pandit was talking in this vain way and the passenger was sitting in silence when a great storm arose and the boat was about to sink. The passenger said to the pandit, “Sir, can you swim?” “No”, replied the pandit. The passenger said, “I don’t know Samkhya or the Patanjala, but I can swim.”What will a man gain by knowing many scriptures? That one thing needful is to know how to cross the river of the word. God alone is real, and all else is illusory.”[3] 5. Scriptural learning is not a substitute for common-sense

A Sanskrit proverb reads – “Just as a blind man has no use for a mirror, what will he do with scriptural knowledge if he lacks common-sense?” The following story from the Panchatantra illustrates the truth that in addition to mastering the Holy Scriptures, one must also have commonsense.

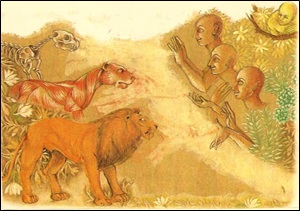

![Svadhaya 3 - 05]() The Four Pandits and the Lion: There were four childhood friends. Three of them studied a lot in different schools and became very learned scholars. The fourth was not that learned, but he had a lot of wisdom and commonsense. One day, the three scholars met with each other and said, “What is the use of our knowledge if we are not able to make any money out of it? Let us go to the royal palace and get a job with the King. This will make us rich.” The first scholar said, “The fourth among us is not really a scholar. What is the use of taking him with us? Let us leave him behind.’

The Four Pandits and the Lion: There were four childhood friends. Three of them studied a lot in different schools and became very learned scholars. The fourth was not that learned, but he had a lot of wisdom and commonsense. One day, the three scholars met with each other and said, “What is the use of our knowledge if we are not able to make any money out of it? Let us go to the royal palace and get a job with the King. This will make us rich.” The first scholar said, “The fourth among us is not really a scholar. What is the use of taking him with us? Let us leave him behind.’But the third of them was a kind hearted person. He said, “We have been friends since our childhood. Therefore, it is not fair to leave him behind.” So all the four got together and started walking towards the palace. On the way, there was a jungle. There, they saw a pile of bones lying on the ground. They immediately recognized that these bones belonged to a dead lion.

![Svadhaya 3 - 06]() The first scholar said, “I know how to put these bones together and complete the skeleton of the lion.” He used his knowledge, and within a few minutes, the skeleton was ready.

The first scholar said, “I know how to put these bones together and complete the skeleton of the lion.” He used his knowledge, and within a few minutes, the skeleton was ready.The second scholar said, “I know how to put blood, skin and muscles into the skeleton.” He too worked for some time, and soon, the skeleton had muscles, eyes, blood and skin on it.

The third scholar said, “I can give life to this animal and make it alive!” Everyone seemed impressed. But, the fourth friend, who was not very scholarly, immediately stopped them and said, “Do not be foolish. A lion eats human beings. If you make it alive, it will pounce on us and eat us.” But the three did not listen to him. However, he begged them to allow him to climb a tree before they make him alive. They agreed.

When the lion came alive, it immediately pounced on the three scholarly friends and killed them. The fourth friend on the tree looked at the dead bodies of his friends and wept. He waited for the lion to go away, and then got off the tree and went back to his village. He said, “I wish that my scholarly friends also had some common-sense.”

6. Scriptural learning is useless if it does not make you a better Human Being

Once, a gathering of Rishis took place at Mt Kailash, where Bhagavan Shiva lives. Rishi Durvasa too walked in with a bundle of books in his hand. But he did not greet any of the other Rishis present, and went up to Bhagavan Shiva’s throne, sitting right next to him. Bhagavan Shiva asked him, “Rishi, how is your study progressing?” With pride on his face, Rishi Durvasa replied, “I have studied all the books that I am carrying and have learned them by heart.”

Rishi Narada got up and then said, “Pardon me Rishi Durvasa, but you are just carrying these books like a donkey that carries burden on its back.” When Rishi Durvasa heard these words, he became red with anger, and threatened Rishi Narada, “How dare you ridicule me? I will curse you. Why did you compare me to a donkey?”

Rishi Narada replied, “True knowledge gives humility, forgiveness and good manners. You walked in without greeting others, and sat right next to Bhagavan, instead of sitting at His feet. Does this not show that you have not learned anything even after memorizing your books?”

Rishi Durvasa realized that Rishi Narada was saying the truth. He realized that his behavior had been foolish. In repentance, he discarded his books in the ocean, and left the assembly to do meditation to atone for his inappropriate behavior.

7. At the Time of Death, it is not Scriptural learning, but Bhakti that will save you

![Svadhaya 3 - 07]() Once, Shri Shankaracharya was walking along the banks of the Ganga River in Varanasi with his disciples. He saw a very old Pandit, almost on his death bed, trying to master and teach the rules of Sanskrit grammar. Out of compassion, the Acharya composed a stotra of 13 verses, in which he asks humans to seek refuge in Krishna because only He can save us at the time of death. Learning rules of grammar for mere intellectual satisfaction will not save us from death. The 14 disciples of Shankaracharya added a verse each, and collectively, it became a Stotra of 27 verses. This beautiful stotra is called Bhaja Govindam, or Moha Mudgara (a Hammer to shatter delusion).

Once, Shri Shankaracharya was walking along the banks of the Ganga River in Varanasi with his disciples. He saw a very old Pandit, almost on his death bed, trying to master and teach the rules of Sanskrit grammar. Out of compassion, the Acharya composed a stotra of 13 verses, in which he asks humans to seek refuge in Krishna because only He can save us at the time of death. Learning rules of grammar for mere intellectual satisfaction will not save us from death. The 14 disciples of Shankaracharya added a verse each, and collectively, it became a Stotra of 27 verses. This beautiful stotra is called Bhaja Govindam, or Moha Mudgara (a Hammer to shatter delusion).The stotra teaches the worthlessness of worldly desires and ego and asks us to seek refuge in Bhagavān by chanting His names, reading the Gita, and becoming dispassionate towards worldly pleasures.

References

[1] Rosen, Steven. 1988. The Life and Times of Lord Chaitanya. Folk Books: Brooklyn (New York). pp. 163-164 [2] Parivrajika, pp. 199-200 [3] Tales and Parables of Sri Ramakrishna. Sri Ramakrishna Math. Mylapore: Madras, pp. 58-59 Featured Image: Wikipedia

Why do Hindus have so many Scriptures?

Most religions have one holy book. The Sikhs have the Adi Granth, Christians have the Bible (which is a collection of 66 books plus a few more in the Catholic version), Muslims have the Koran and Jews have the Torah. But Hindus, Buddhists and Jains seem to have an abundance of scriptures – literally hundreds of them. Why don’t Hindus have just one Holy Book?

Story: Rishi Bharadvaja realizes that there is no end to studying Scriptures

![SvÄdhyÄya 4 01]() A beautiful story in the Yajurveda (Taittiriya Brahmana 3.10.11) narrates the infinite extent of the Vedas themselves. Some Rishis in the Hindu tradition are said to have lived a very long life. One of them was Rishi Bharadvaja. A beautiful story is narrated on his love for the study of the Vedas. He spent his extra-ordinary long life of 300 years studying the Vedas. Pleased with his devotion to the scriptures, Indra appeared before the Rishi and asked: “If I were to increase your life by another 300 years, what would you want to do?”

A beautiful story in the Yajurveda (Taittiriya Brahmana 3.10.11) narrates the infinite extent of the Vedas themselves. Some Rishis in the Hindu tradition are said to have lived a very long life. One of them was Rishi Bharadvaja. A beautiful story is narrated on his love for the study of the Vedas. He spent his extra-ordinary long life of 300 years studying the Vedas. Pleased with his devotion to the scriptures, Indra appeared before the Rishi and asked: “If I were to increase your life by another 300 years, what would you want to do?”The Rishi replied, “I would spend the next 100 years again in studying the Vedas.”

Indra then created three mountains of sand in front of the Rishi, and said, “These three mountains represent Rik, Yajus and Samans, the three types of Vedic mantras. And from each mountain, your study is but a fistful of sand because endless are the Vedas (anantā vai vedāh).”

Rishi Bharadvaja was amazed, and asked Indra to show him the true path. Indra recommended him to worship the Divine in the form of the Sun through a special religious ceremony. He said that worshipping Bhagavān was equivalent in merit to mastering the three mountains of sand worth Vedic knowledge.

Rishi Bharadvaja followed Indra’s advice, and attained Moksha. He realized that there is no end to studying the scriptures. At a certain point, we should focus more on applying their teachings.

There are many answers to the question why we Hindus have thousands of scriptures:

1. There is a lot of wisdom in Hindu Dharma, and this requires many books. Hindus have been blessed with a continuous string of saints and sages for several thousands of years. These great men and their disciples have collected their teachings resulting in a vast number of sacred writings. It is similar to the fact that the entire knowledge of Physics cannot be captured within a single book these days. So also, the entire wisdom of Hindus cannot be incorporated in just one holy book.

2. Hindu Dharma is the most ancient faith in the world. It is expected then that it has had the longest period of time to churn out more holy writings than others. This is another obvious reason why Hindus have so many scriptures.

3. The core scriptures of other religions originated in a very small area whereas the core scriptures of Hindus were compiled in a much larger region, resulting in Hindus having a lot more holy writings than many other faiths. To get a perspective, most Hindu writings originated in different parts of the Indian subcontinent, a region that is dozens of time larger than Israel (where the Jewish and Christian writings arose) or Hijaz (where the Koran originated). This too has resulted in the large number of Hindu scriptures.

4. Hindu Dharma recognizes a diversity of beliefs, doctrines and practices. It is not a ‘one size fits all’ or a ‘my way or the highway religion’. To reach these diverse perspectives, Hindus have multiple books. This explains why Hindus have multiple schools of philosophy, each with their own set of scriptures.

5. Hinduism also permits the worship of God in many different forms and also as a Formless Supreme Being. Many different scriptures contain instructions on the proper procedure for worshipping these different forms of the Divine. For example, the Vaishnava Pancharatra texts have details on worshipping Lord Vishnu, whereas the Shaiva Agamas contain instructions on worshipping Lord Shiva. The multiplicity of worship amongst Hindus has also contributed to the diversity of Hindu scriptures.

6. Hindus recognize the fact different people are at different levels of mental capacity, spiritual attainment and temperaments. To cater to people of different calibers, Hindus have different scriptures. For example, the Purāṇas are more user-friendly and are geared towards Hindus who might not have the competence or temperament to study the more difficult Vedas. This is just like the fact that students use different textbooks for the same subject (say, Chemistry) in different grades in their schools.

7. Hindus also tend to have different scriptures to discuss different topics instead of lumping all topics and branches of learning into a single book. For example, just as students have different textbooks for Physics, Chemistry and Biology, Hindus too have different scriptures to explain to them the principles of ritual, devotion, wisdom and so on in separate books. If the wisdom of Hindus were not great in extent, it would have been possible to combine all these different writings into one collection. But individual Hindu scriptures can also tend to be very vast. E.g., the Vedic literature is six times the length of the Bible.

![SvÄdhyÄya 4 02]()

8. Hindus do not have a central authority that regulates what is scripture and what is an ordinary writing. In other religions such as Islam and Christianity, there too existed many versions of scripture in the past, but central councils of scholars met to stamp out diversity of holy writings and mandated only one particular version of their scripture as authorized or acceptable. For example the Council of Nicea in 325 CE suppressed several alternate versions of the Bible and approved only one that is similar to the version available these days. Similarly, the second Islamic Caliph Othman ordered destruction of several divergent versions of the Koran and allowed only one to circulate. In contrast, Hindus accept diversity and the original four Vedas developed into hundreds of different branches that differ slightly from each other. Hindus consider all these versions as authoritative because of the realization that all these branches teach the same principles, even though in a slightly different language. Hindus explain the multiplicity of our scriptures through the dictum that “The Truth is One, but the wise teach it in many different ways” (Rigveda 1.164.46).

9. Hindu Dharma is not tied to a particular period of time, or to a particular founder of the Hindu religion, or to a last Prophet or the only son of God. Hindus believe that although the Vedas are held to be the gold standard because they were intuited by spiritually realized Rishis, there are many other writings that contain the teachings of Saints, Sages and scholars who were also divinely inspired. Hindus believe that at any given point of time in history, it is possible for a spiritual person to attain great heights of realization which the Vedas talk about, and the writings of such great men then assume the form of scripture, because they reflect the spirit of the Vedas and other holy books.

10. Hinduism relies a lot on personal teaching by a Guru. Much of Hindu scriptures have been passed on from generation to generation through the medium of instruction from Guru to his disciples. Several Gurus have added their own commentaries and explanations to the scriptures to explain their meaning more effectively. Or they have compiled their own versions of the scripture to cater to the needs of their own disciples better. This has lead to several versions of the same scripture, and Hindus do not have a problem treating these different versions and commentaries as sacred writings.

11. Hindus also believe that several scriptures such as the Dhamashastras do not have eternal validity because of changed social conditions. Therefore, new scriptures are codified to apply the Vedic principles so that they suit the new conditions better. For example, it was believed by some Hindus that the Manu Smriti was applicable in more ancient times whereas the Parashara Smriti is applicable in the present age according to some Hindus.

12. In many cases, one holy book of the Hindus has been split into many for the convenience of the readers. For e.g., Hindus believe that the Vedas were one holy book which was split into four Vedas (Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda and Atharvaveda) for the convenience of students by Veda Vyasa. In contrast, Christians have combined 66 books written by different people and during different times into a single book called the Bible.

13. The final reason for such a large number of scriptural texts in Hinduism is the fact that Sanskrit, in which the most ancient writings of Hindus were composed, ceased to be a popularly spoken language in the last 2000 years or so. Therefore, Saints who were filled with compassion wrote versions of several popular ancient Sanskrit scriptures in the vernacular languages prevalent amongst Hindus in their region. E.g. the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki has been rendered into Tamil, Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, Telugu and numerous other languages by Saint Poets and is widely read with reverence by Hindus today.

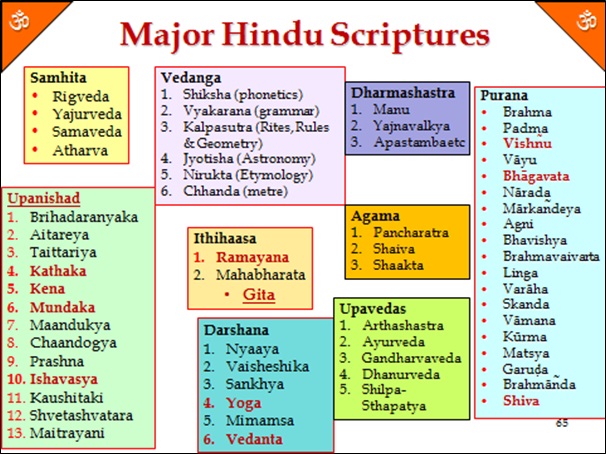

Can we Read all these Scriptures? Choosing One Scripture for Studying

Having multiple scriptures can sometimes make the task of reading them daunting for most Hindus. Therefore, there are some scriptures that are believed to contain the main teachings of all the other scriptures. E.g., the Gita is said to be the essence of teachings of spiritual scriptures such as the Upanishads. It is recommended that if one can read only one Hindu scripture, then let it be the Bhagavad Gita. Or Ramayana. Or Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Intellectual minded Hindus also like to read the Upanishads today.

In the chart below, the scriptures that are commonly read by ordinary Hindus are shown in the red font.

Featured Image: The Hindu Portal

Svādhyāya: Studying our Holy Books- VThe Hindu tendency to see all faiths through their own spiritual viewpoint is patronizing and insulting to other faiths, whose followers openly reject the Hindu interpretations of their own doctrines which they have understood in a different manner traditionally.

Hindu Scriptures and the Proverbial Hindu Tolerance: Interfaith Perspectives

Hindu Dharma is not a ‘One Book, One Prophet, One God’ religion. The very fact that there are thousands of sacred books within our own tradition, and that thousands are Saints and Sages are associated with revealing and compiling them has made Hindus take it for granted that diversity of scriptures is a fact of nature. The existence of so large a number of scriptures within our own tradition makes it easier for Hindus to accept that religious traditions outside our own also have their own scriptures, and that these non-Hindu scriptures are also worthy of study, respect and reverence.

Hindu Dharma encourages us not just to get a well-rounded knowledge of all our scriptures (or as many as possible), but also study the Holy Books of other religions with respect. A scripture which says that it is itself is ‘the only true book’ and everything else is not worthy of study and respect is actually the product of the limited spiritual vision and world view of its author. This is why Hindus have not indulged in bouts of burning and destroying books of other religions. In contrast, the followers of ‘One Book, One Religion, Last/One Prophet, One God’ faiths have frequently burned the scriptures of other religions and continue to cause bloodshed and destruction even in our own times.

Instead of telling us to prove ourselves different from other peoples so that we can set ‘up our own prophetable shop’ for potential customers, Hindu Dharma advises us to look for common spiritual themes or the common essence of all these diverse scriptures. Therefore, instead of seeing these different holy books as disconnected and discrete pieces of knowledge, we should seek their underlying higher teachings. For example, the Upanishad says:

Truth is One, but the realized Poets with spiritual vision describe it in many different ways. Rigveda 1.164.46 Cows are of different colors but their milk is the same color. Similarly, (the wise person) regards spiritual wisdom as the milk and the many branched Vedas as different cows. Amritabindu Upanishad 19 Just as the bee extracts the essence from several flowers (to make the nectar like honey), a clever man should also take the essence from all sources and scriptures, whether they are short or long. Bhāgavata Purāņa 11.8.10 |

This does not mean however that Hindus should accept any writing considered as sacred by any community as a holy scripture. The rule still remains that the Vedas are the golden standard by which all other scriptures are judged. Unfortunately, Hindus have carried the spirit of inclusivism and acceptance of diversity to such an extreme that they have ceased to see the genuine differences in the doctrines of different religions, and also fail to see the faults in various religious scriptures. Likewise, they have also started assuming that the Prophets and Saints of all religions were also spiritually realized souls in the Vedāntic and Yogic mold of Hindu tradition. However, when we actually read the sacred texts of other religions, and study the biographies of prophets and saints, the results are not always flattering. In fact, the Hindu tendency to see all faiths through their own spiritual viewpoint is patronizing and insulting to other faiths, whose followers openly reject the Hindu interpretations of their own doctrines which they have understood in a different manner traditionally. Therefore, instead of considering scriptures and important figures of all religions as equal, Hindus ought to use ‘viveka’ and try to discriminate between what is false, and what is true.

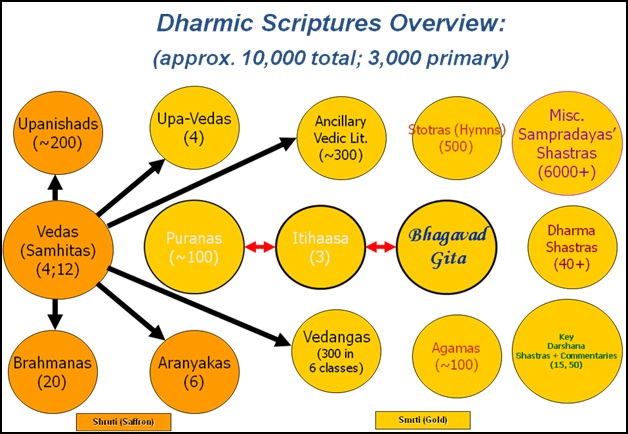

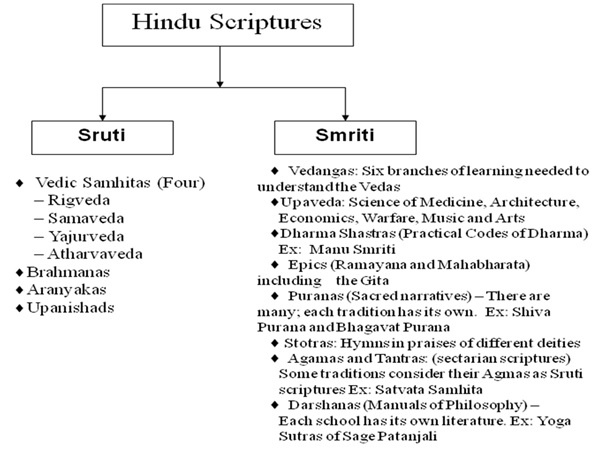

Classification of Hindu Scriptures

The two major categories in which all Hindu scriptures are divided are the Shruti and the Smriti.

Shruti: The Vedas constitute the Shruti, a word that means ‘that which has been heard (from God) by the Rishis’ and are considered of Divine origin[1]. The principles of Dharma that are taught in the Vedas are called the ‘Vaidika Dharma’ or ‘Shrauta Dharma’ and are considered to be infallible (without error), universal and eternal. Smriti: The word Smriti word literally means ‘that which is remembered’. Human culture advances when the collected wisdom of the society is passed on from one generation to another (‘societal memory’), and each new generation adds to its inherited wisdom.

Whereas Shruti is considered of Divine origin or inspiration, Smriti is considered the wisdom of Saints and Sages who were pious, virtuous and had understood the Vedas. It is believed that the teachings of Smritis are derived from the Vedas itself. The Hindu tradition says that although the Saintly authors of the Smritis were enlightened souls, yet it is still possible that they had some imperfections. For this reason, the Smriti scriptures have a lower authority than the Shruti scriptures, which are directly revealed by or inspired by the perfect God. Smritis which openly conflict with the Veda are rejected.

“Smriti or ‘remembering’ is an eminently personal experience. One remembers what one has done or what has happened to one. Through memory one can appropriate and relive one’s past, and learn from experiences. These marks – appropriation, reliving, learning, and guidance – are all included in the sense of smriti. Smriti refers to that store of group experiences by which the community appropriates and relives its past, learns from it and is guided by it, and in the process shapes its identity. In so far as smriti has to do with personal experience, it is humanly authored (paurusheya in contrast to shruti proper, which is apurusheya or ‘not humanly produced.’ This is a crucial distinction for the ongoing life of a community. The non-personal Veda, received by the seers, which is religiously sacrosanct, linguistically immutable, culturally perfect…. Needs to be made accessible and humanized. Smriti probes, interrogates, debates, offers answers, mediates. It makes the impersonal personal. It allows the shruti to shape the world in which we live, and so to shape lives. For what may be smriti to you or your community, may not function as smriti for me or my community. Or it may weight this authority differently according to the particular traditions that nurture us, or the demands of our situations. Smriti is the medium through which we hear the voice of the shruti; it is interpretive, selective, collaborative, pliable. Shruti and smriti – or their equivalents, namely the primary scripture and tradition – are the co-ordinates by which the religious authority of Hinduism has been transmitted.

For Hindus, smriti recalls exemplary figures and events that have shaped their past, the universe they inhabit. These figures may be human or non-human, benevolent or hostile, virtuous or malign. Smriti pronounces on the origination and transmission of almost every branch of human expertise. Its concerns include how to use words, how to read the heavens, how to care for elephants, how to make love, how to make war, how to make temples, how to worship, how to go on pilgrimage (and where and why), how to dance, how to sing; how to classify men, women, horses, gems, snakes, herbs, dreams….how to curse and how to heal. Smriti deals with the founding of ancient dynasties and their ending; with the origination and destruction of the world; with rites of passage, the goals and stages of life, and cremation rites.

Smriti prescribes and cautions in all matters of dharma or right living: in the dharma of husbands, in the dharma of wives….of eating, drinking….worshipping, purifying: in a word, in the dharma of living and in the dharma of dying. Smriti is a great story-teller, myth-maker, codifier, teacher, punisher, rewarder, guide.”[2] “Smriti can support primary scripture directly or indirectly through stories about gods, saints and sacred events, cautionary tales, graphic descriptions of heavenly and hellish realms, didactic discourses, the elaboration of codes of dharma, the sanctioning of reward or punishments for observing or violating these codes, and by recording the development of human expertise in prosody, phonetics, astronomy, love-making, war-waging, temple building, icon-shaping, philosophy and theology and so on. The amount of accumulated material that counts for smriti over the past 4000 years is immense, and in the more articulate world in which we live this material is increasingly rapidly all the time….”[3] “….implementing smriti is a subjective exercise. What may be suitably corroborative material for my grasp of primary scripture may not be so for you; or you may use the same material in a different way. For smriti to function as smriti, what matters is the intention seen to underlie the material in question. An item of smriti may not seem to focus on primary scripture at all, e.g. a treatise on erotics, or grammar, or astronomy, but it is regarded as smriti because it is seen as intended to further – or is made by those in appropriate authority to bear upon – the aims of the shruti or primary scripture. For instance, it may do this by enabling an appropriate lifestyle to be followed, for it is only on this basis that scripture would be efficacious.”[4] Although the word Smriti may be used in general to denote all the non-Shruti literature, it is often used in a more restricted sense to denote only the Dharmashāstra scriptures. Traditionally, the Dharmashāstras are considered the second only to Shruti in terms of authority. Therefore, they are more authoritative than the Purāṇas, Itihāsas and all the other non-Shruti classes of scriptures.

Āgamas:

There is a class of Hindu scriptures called the Āgamas which are accepted only by the sampradāya or the tradition to which they belong. For e.g., the Vaishnava Āgamas are followed only by worshippers of Vishnu, and the Shaiva Agamas are accepted only by worshippers of Shiva. The Āgamas are also referred to as Tantras, especially those belong to the Shākta and Shaiva traditions. Sometimes, the followers of these Āgamas consider their own Agama text as at par with Shruti. It is for this reason that Hindu traditions sometimes says that the Shruti is of two types – Vaidika and Tāntrika. However, this view that the Āgamas are of equal authority as the Shruti is not accepted by all Hindus.

Shruti as the Supreme Authority for Hindus:

Practically all Hindus accept the supreme authority of the Shruti literature, with a few exceptions such as the Lingayyata Shaivite Hindus, who consider the Shaiva scriptures as more authoritative. Acceptance of the Vedic authority is often considered a hallmark of being a Hindu. For this reason, Jains and Buddhists are not sometimes considered as Hindus, even though they share their history, cultural heritage, ethical values etc., with the Hindu community. The case of Sikhs is more complicated, because their own supreme scripture (the Ādi Grantha) seems to accept the Divine origin and authority of the Vedas in matters of Dharma. However, modern Sikhs by and large do not accept the Vedas and do not consider themselves as Hindus.

Sometimes, the Agamas and Tantras are considered a second type of Shrutis in addition to the Vedas (Samhitā, Brāhmaṇa, Āranyaka and Upanishads). This is because according to some Hindu traditions, the Āgamas and Tantras were also directly revealed by Bhagavān.

Some Hindus also believe that the Bhagavad Gita is Shruti, because Bhagavān in the Form of Krishna revealed it to Arjuna. A majority of Hindus however believe in the chart displayed above.

Similarly, the school of Indian philosophies (Darshana Shastras) that accept the authority of the Shruti, even if for the sake of formality, are considered as Āstika (or ‘Believer’, ‘orthodox’) Darshanas; whereas those which reject the Shruti are called the Nāstika (heretical) Darshanas. The latter includes the Buddhist, Jain and the Chārvāka/Bāhrsapatya (atheist and materialistic) Darshanas. The former includes the Hindu Darshanas of Sāmkhya, Yoga, Vedānta, Pūrva Mīmāmsā, Nyāya and Vaisheshika Darshanas.

The chart below shows the major categories of Hindu sacred literature.

Notes

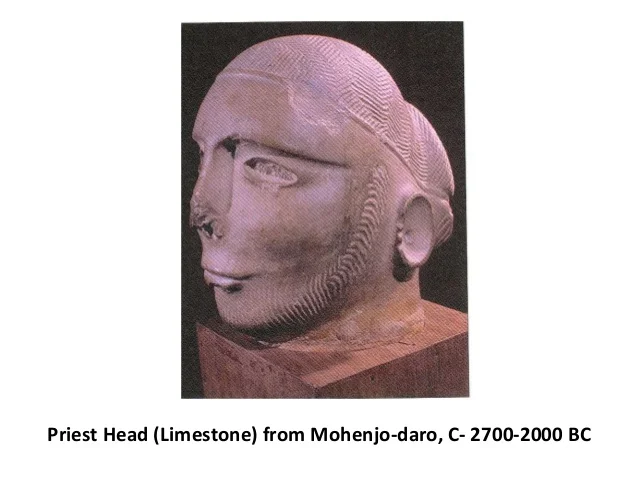

[1] The word ‘Rishi’ is derived from the Sanskrit root ‘Drish’, or ‘to see’. In other words, the Shruti is the record of the spiritual vision, or insight into the Divine of the Rishis. The Rishis were pure hearted and spritually advanced individuals who devoted their entire lives to Dharma and Moksha. Women Rishis are called Rishikas. ![SvÄdhyÄya-6 Veda]() Traditionally, the Vedic literature as such signifies a vast body of sacred and esoteric knowledge concerning eternal spiritual truths revealed to sages (Rishis) during intense meditation. They have been accorded the position of revealed scriptures and are revered in Hindu religious tradition.

Traditionally, the Vedic literature as such signifies a vast body of sacred and esoteric knowledge concerning eternal spiritual truths revealed to sages (Rishis) during intense meditation. They have been accorded the position of revealed scriptures and are revered in Hindu religious tradition.The Vedas or Shruti

Importance of the Vedas

As explained above, the Vedas are considered the supreme scriptures, or the gold-standard by most Hindus. The word ‘Veda’ is often derived from 5 Sanskrit roots these days:

§ Vid jnaane: To know

§ Vid sattaayaam: To be, to endure

§ Vid labhe: To obtain

§ Vid vichaarane: To consider

§ Vid chetanaakhyaananiveseshu: To feel, to tell, to dwell

To these roots is added the suffix ‘ghaw’ according to Ashtādhyāyī 3.3.19, the celebrated text of Sanskrit grammar of Panini. Accordingly, the word Veda means ‘the means by which, or in which all persons know, acquire mastery in, deliberate over the various lores or live or subsist upon them.’

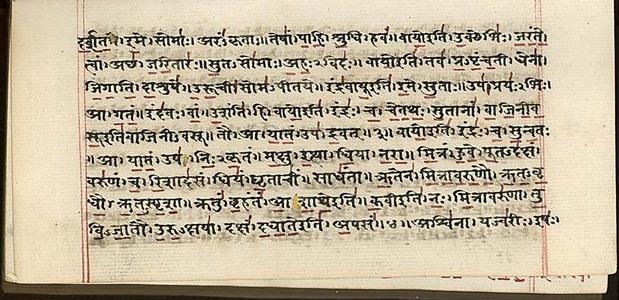

Traditionally, the Vedic literature as such signifies a vast body of sacred and esoteric knowledge concerning eternal spiritual truths revealed to sages (Rishis) during intense meditation. They have been accorded the position of revealed scriptures and are revered in Hindu religious tradition. Over the millennia the Vedas have been handed over generation to generation by oral tradition and hence the name “shruti” or “that which is heard”. According to tradition they are un-authored (apaurusheya) and eternal, and are considered the revelation of God to the Rishis. This is the other reason for calling them Shruti.

Theoretically, the Vedic corpus is held in deep reverence in the Hindu society. It constitutes the most authoritative genre of Hindu scriptures. Any other Hindu scripture must agree with the Vedas in order to be considered an authority. Schools of philosophy which reject the authority of the Vedas are considered ‘Naastika’ or heretical, while schools which accept Vedic authority, even if nominally, are considered ‘Aastika’ or orthodox, from a Hindu perspective. While most Hindus never see Vedic texts in their lifetime, the term ‘Veda’ is used as a synonym for authoritativeness in religious matters. The Vedas are considered full of all kinds of knowledge, and an infallible guide for man in his quest for the four goals – Dharma, Artha(material welfare), Kāma (pleasure and happiness) and Moksha (Salvation). In sacred Hindu literature, they are considered the very manifestation of God, and the ultimate source of all wisdom and of all Dharma.

Hindu priests were exhorted to study them regularly, recite their sentences, practice their sacraments and memorize their words. In practice however, this has been restricted to a dwindling minority of the Brāhmaṇa caste, despite recent attempts to revive Vedic study, ritual and recitation in the traditional manner. On the other hand, the Vedic texts are now widely available in print, and this has lead to a greater dissemination of their knowledge amongst Hindu masses, than say, a century back. Even here however, the popularization largely concerns the spiritual treatises called the Upanishads – the texts par excellence of Hindu spirituality. In fact, for several centuries now, the word ‘Veda’ has been used by Hindu teachers to indicate the Upanishadic texts in particular.

How Were the Vedas Revealed?

According to Hindu tradition, Bhagavān Brahmā created the Universe and then revealed the four Vedas to numerous Rishis at the beginning of this creation. Since then, an unbroken chain of students and teachers have been transmitting the Vedas down to our time. The four faces of Brahmā represent these four Vedas as well as the four directions.

The Vedas are also associated with his consort Devi Sarasvati, who is the Devi of all wisdom and knowledge.

The Vedas however are not the creation or composition of the Brahmā because they are eternal. Bhagavān Brahmā is merely their caretaker of this Divine knowledge, which really belongs to the Supreme Being (Brahman). However, Brahmā also composed some original works, which initiated many other branches of Hindu knowledge – like Ayurveda, Dharmashāstras etc. All these works whose tradition started from the original compositions of Brahmā are called Smritis; whereas the Vedas which were revealed by Brahmā but not authored by him are called Shruti (‘that which are heard from Brahman’).

As time progressed, the capacity of human beings to study scriptures declined. Sometimes, the Vedas even got lost. Therefore, a Rishi appeared periodically to re-arrange them and even rediscover them. The current version of the four Vedas is said to have been given their present form by Rishi Veda Vyasa, who was the son of Rishi Parāshara, and a fisherwoman named Satyavatī. Veda Vyāsa then taught the Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda and Atharvaveda to his four students: Rishi Paila, Rishi Vaishampāyana, Rishi Jaimini and Rishi Sumantu respectively. They in turn taught them to numerous disciples and so on, leading to slightly differing versions of the four Vedas. These versions are known by the names of the last Rishis after whom no other modifications were made to the texts of the Vedas.

However, another viewpoint is that hundreds of very ancient Rishis (mainly on the banks of the river Sarasvati which dried out by 1500 BCE or even earlier) received the hymns and sections of the four Vedas from Brahman. Brahmā has no role to play in this viewpoint. A big chunk of these revelations were lost with time, and Veda Vyāsa compiled whatever remained, to preserve it for posterity. Even the existing Vedic literature is 6 times the length of the Bible, and is much older!

There is a third, modern viewpoint proposed by Swami Dayanand Saraswati (1824-1873 CE). According to this view, the Supreme Being revealed the four Vedas respectively to Rishis Agni (Rigveda), Vāyu (Yajurveda), Āditya (Samaveda) and Angirasa (Atharvaveda).

Several modern scholars have proposed different dates for the Vedas:[1] § Tilak 4000 – 2500 BCE

§ Jacobi 4000 BCE

§ Wilson 3500 BCE

§ Hough 2500 – 1400 BCE

§ R C Dutt 2000 – 1400 BCE

§ Roth 1000 BCE

§ Max Mueller 1500 – 1200 BCE

Classification of the Vedic Scriptures