The thesis of this monograph is that the mušḫuššu, aurochs, lions, symbolising Marduk, Adad, and Ishtar are Indus Script hypertexts which signify wealth accounting ledgers of metalwork catalogues involving alloys, minerals, metals, cire perdue metal castings, smelting, forging, carburization, cementation and other metallurgical techniques.

This monograph is organized in the folllowing sections to identify and read the hieroglyphs which compose an Indus Script hypertext in the corpora of inscriptions.

Section 1. Archaeobotany

Section 2. Archaeozoology

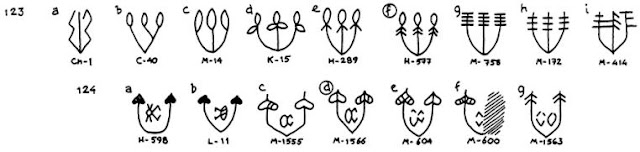

Section 3. Orthography of the Field Symbol of One-horned young bull

The Indus Script Corpora now include over 8000 inscriptions, the majority of which include the Field Symbol of 1. one-horned young bull; PLUS 2. standard device wich vivid hieroglyph components:

![]() m1656

m1656

m1656 Mohenjodro Pectoral. Carnelian. kanda kanka 'rim of pot' (Santali) rebus: kanda 'fire-altar'khaNDa 'implements' PLUS karNaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNi 'Supercargo, scribe' PLUS semantic determinant: kANDa 'water' rebus: khaNDa 'implements'. In the context of semantics of karNi 'supercargo', it is possible to decipher the standard device sangaDa 'lathe' rebus: jangada 'double-canoe' as a seafaring merchant vessel. The suffix -karnika signifies a 'maker'. Kāraṇika [der. fr. prec.] the meaning ought to be "one who is under a certain obligation" or "one who dispenses certain obligations." In usu˚ S ii.257 however used simply in the sense of making: arrow -- maker, fletcher (Pali). kāraṇika m. ʻ teacher ʼ MBh., ʻ judge ʼ Pañcat. [kā- raṇa -- ]Pa. usu -- kāraṇika -- m. ʻ arrow -- maker ʼ; Pk. kāraṇiya -- m. ʻ teacher of Nyāya ʼ; S. kāriṇī m. ʻ guardian, heir ʼ; N. kārani ʻ abettor in crime ʼ; M. kārṇī m. ʻ prime minister, supercargo of a ship ʼ, kul -- karṇī m. ʻ village accountant ʼ(CDIAL 3058) Kāraṇika is an arrows-maker, a fletcher. "Fletching (also known as a flight or feather) is the aerodynamic stabilization of arrows or darts with materials such as feathers, each piece of which is referred to as a fletch. A fletcher is a person who attaches the fletching.The word is related to the French word flèche, meaning "arrow", via Old French; the ultimate root is Frankish fliukka."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fletching

Perhaps the reading should be ˚kāraka. (Pali) Similarly, khaṇḍa kāraṇika can be semantically explained as 'implements maker'. The pectoral thus signifies the profession of an implements-maker and a supercargo, merchant's representative on the merchant vessel taking charge of the cargo and the trade of the cargo.

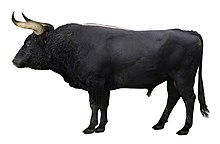

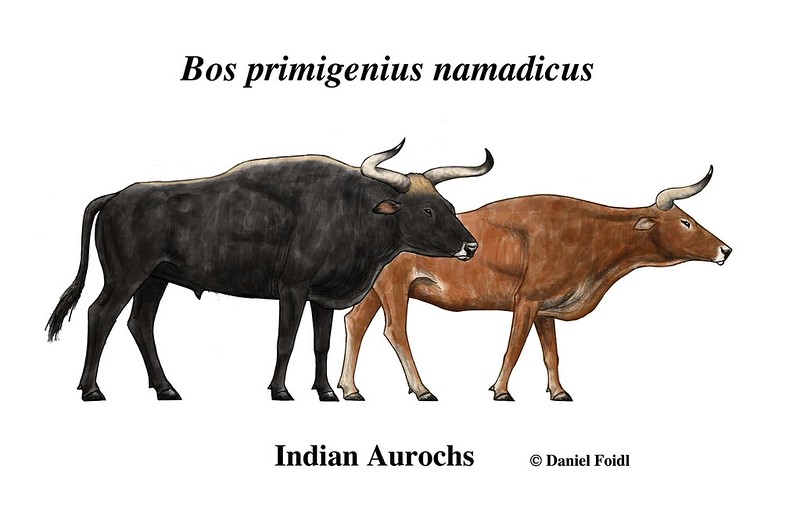

"The aurochs ( or ; pl. aurochs, or rarely aurochsen, aurochses), also known as urus or ure (Bos primigenius), is an extinct species of large wild cattle that inhabited Europe, Asia, and North Africa...During the Neolithic Revolution, which occurred during the early Holocene, at least two aurochs domestication events occurred: one related to the Indian subspecies, leading to zebu cattle, and the other one related to the Eurasian subspecies, leading to taurine cattle. Other species of wild bovines were also domesticated, namely the wild water buffalo, gaur, wild yak and banteng. In modern cattle, numerous breeds share characteristics of the aurochs, such as a dark colour in the bulls with a light eel stripe along the back (the cows being lighter), or a typical aurochs-like horn shape.("Aurochs – Bos primigenius". petermaas.nl.)"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aurochs

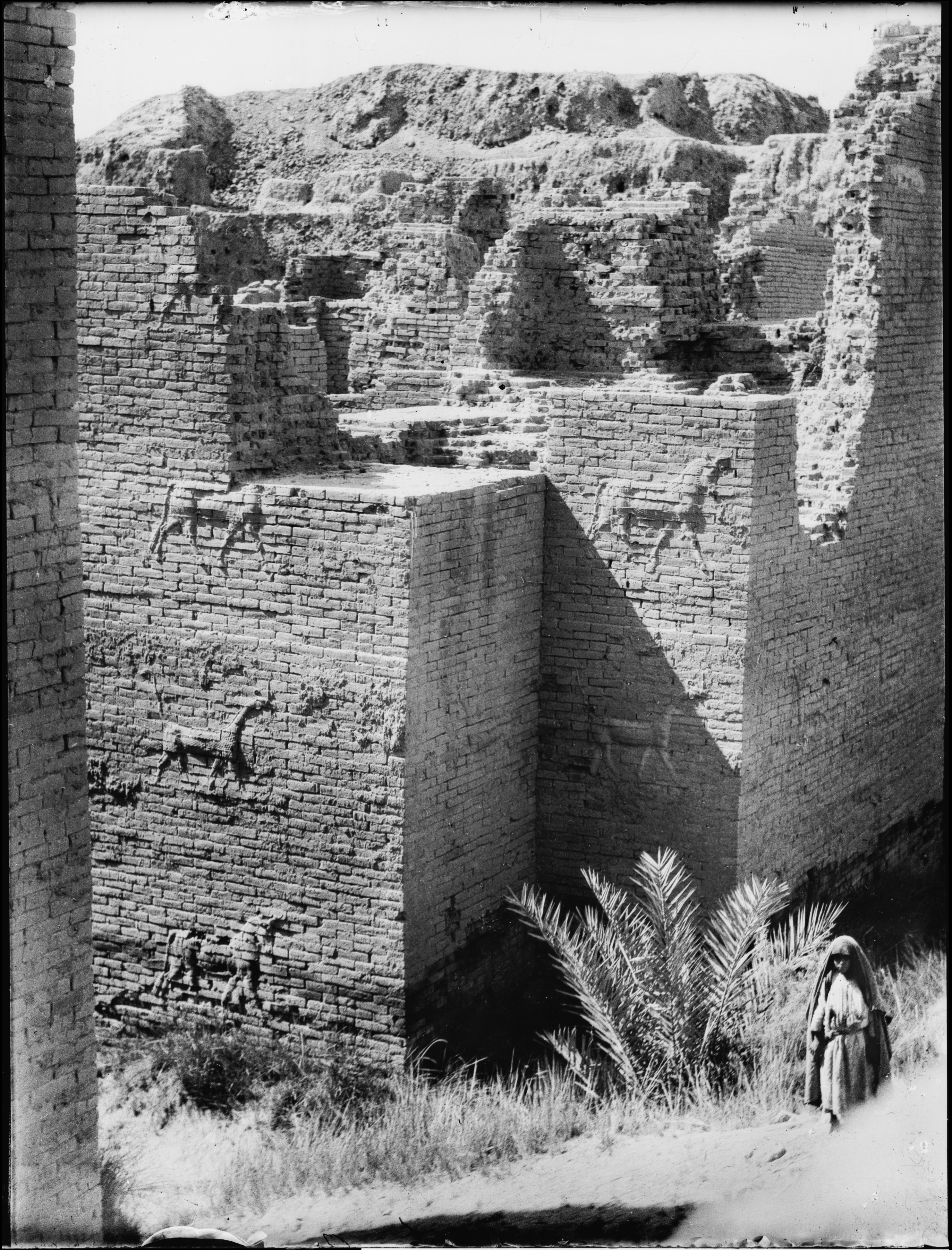

I suggest that the aurochs on the walls of Ishtar Gate, Babylon (6th cent.BCE) are Indian aurochs, one-horned young bulls which are the most frequently deployed hypertexts on Indus Script Corpora. These aurochs signify arka kundaṇa 'goldsmith guild' PLUS koḍ 'horn' rebus koḍ 'workshop'.The lions signify arye 'lion' rebus: arā'brass'. The tradition of signifying wealth accounting ledgers using hieroglyphs/hypertexts is traceable to the Sumerian cylinder seal which displays a mudhif.

कोंडी (p. 102) kōṇḍī f (कोंडणें) A confined place gen.; a lockup house, a pen, fold, pound; a receiving apartment or court for Bráhmans gathering for दक्षिणा; a prison at the play of आट्यापाट्या; a dammed up part of a stream &c. &c. कोंडवाड (p. 102) kōṇḍavāḍa n f C (कोंडणें & वाडा) A pen or fold for cattle. कोंडण (p. 102) kōṇḍaṇa f A fold or pen. कोंडमार (p. 102) kōṇḍamāra or -मारा m (कोंडणें & मारणें) Shutting up in a confined place and beating. Gen. used in the laxer senses of Suffocating or stifling in a close room; pressing hard and distressing (of an opponent) in disputation; straitening and oppressing (of a person) under many troubles or difficulties; कोंडाळें (p. 102) kōṇḍāḷēṃ n (कुंडली S) A ring or circularly inclosed space. 2 fig. A circle made by persons sitting round. कोंड (p. 102) kōṇḍa m C A circular hedge or field-fence. 2 A circle described around a person under adjuration. 3 The circle at marbles. 4 A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. 5 Grounds under one occupancy or tenancy. 6 f R A deep part of a river. 7 f (Or कोंडी q. v.) A confined place gen.; a lock-up house &c.

कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa, 'cattlepen', Mesopotamia Rebus: kundaṇa 'fine gold'

Mudhif and three reed banners ![]()

Figure 15.1. Sealing with representations of reed structures with cows, calves, lambs, and ringed

bundle “standards” of Inana (drawing by Diane Gurney. After Hamilton 1967, fig. 1)

Three rings on reed posts are three dotted circles: dāya 'dotted circle' on dhā̆vaḍ priest of 'iron-smelters', signifies tadbhava from Rigveda dhāī ''a strand (Sindhi) (hence, dotted circle shoring cross section of a thread through a perorated bead);rebus: dhāū, dhāv ʻa partic. soft red ores'. dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā]Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)

![]() Cylinder seal impression, Uruk period, Uruk?, 3500-2900 BCE. Note a load of livestock (upper), overlapping greatly (weird representation), and standard 'mudhif' reed house form common to S. Iraq (lower).

Cylinder seal impression, Uruk period, Uruk?, 3500-2900 BCE. Note a load of livestock (upper), overlapping greatly (weird representation), and standard 'mudhif' reed house form common to S. Iraq (lower).

Cattle Byres c.3200-3000 B.C. Late Uruk-Jemdet Nasr period. Magnesite. Cylinder seal. In the lower field of this seal appear three reed cattle byres. Each byre is surmounted by three reed pillars topped by rings, a motif that has been suggested as symbolizing a male god, perhaps Dumuzi. Within the huts calves or vessels appear alternately; from the sides come calves that drink out of a vessel between them. Above each pair of animals another small calf appears. A herd of enormous cattle moves in the upper field. Cattle and cattle byres in Southern Mesopotamia, c. 3500 BCE. Drawing of an impression from a Uruk period cylinder seal. (After Moorey, PRS, 1999, Ancient mesopotamian materials and industries: the archaeological evidence, Eisenbrauns.)

![Image result for bharatkalyan97 mudhif]() A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

![08-02-14/62 Fragment of a stele,...]()

- Fragment of a stele, raised standards. From Tello.

- Hieroglyphs: Quadrupeds exiting the mund (or mudhif) are pasaramu, pasalamu ‘an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped’ (Telugu) పసరము [ pasaramu ] or పసలము pasaramu. [Tel.] n. A beast, an animal. గోమహిషహాతి.

- A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia. Limestone 16 X 22.5 cm. AO 8842, Louvre, Departement des Antiquites Orientales, Paris, France. Six circles decorated on the reed post are semantic determinants of Glyphआर [ āra ] A term in the play of इटीदांडू,--the number six. (Marathi) आर [ āra ] A tuft or ring of hair on the body. (Marathi) Rebus: āra ‘brass’. काँड् । काण्डः m. the stalk or stem of a reed, grass, or the like, straw. In the compound with dan 5 (p. 221a, l. 13) the word is spelt kāḍ. The rebus reading of the pair of reeds in Sumer standard is: khānḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’.

Rebus: pasra = a smithy, place where a black-smith works, to work as a blacksmith; kamar pasra = a smithy; pasrao lagao akata se ban:? Has the blacksmith begun to work? pasraedae = the blacksmith is at his work (Santali.lex.) pasra meṛed, pasāra meṛed = syn. of koṭe meṛed = forged iron, in contrast to dul meṛed, cast iron (Mundari.lex.) పసారము [ pasāramu ] or పసారు pasārdmu. [Tel.] n. A shop. అంగడి.

Both hieroglyphs together may have read rebus: *kāṇḍāra: *kāṇḍakara ʻ worker with reeds or arrows ʼ. [kāˊṇḍa -- , kará -- 1] L. kanērā m. ʻ mat -- maker ʼ; H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers ʼ.(CDIAL 3024). Rebus: kaṇḍa 'fire-altar'. khaṇḍa 'implements' (Santali) लोखंड (p. 423) lōkhaṇḍa n (लोह S) Iron. लोखंडकाम (p. 423) lōkhaṇḍakāma n Iron work; that portion (of a building, machine &c.) which consists of iron. 2 The business of an ironsmith. लोखंडी (p. 423) lōkhaṇḍī a (लोखंड) Composed of iron; relating to iron.

![]()

Figure 15.2. Tell al Ubaid, Temple of Ninhursag. Isometric reconstruction. Early Dynastic period

(ca. 2600 b.c.e.) (Hall and Woolley 1927)

ancient relief of reed huts in Mesopotamia; columns of bound reeds like quansut huts https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=3&v=3TIcVJGfjLU

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/241294492513412051/

Cattle gather around a byre, distinguished by its poles with rings. From a cylinder seal of the Late Uruk period. Black and Green, Gods Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. Figure 127 (p. 155)

![]()

The Uruk trough. From Uruk (Warka), southern Iraq. Late Prehistoric period, about 3300-3000 BC

A cult object in the Temple of Inanna?

This trough was found at Uruk, the largest city so far known in southern Mesopotamia in the late prehistoric period (3300-3000 BC). The carving on the side shows a procession of sheep approaching a reed hut (of a type still found in southern Iraq) and two lambs emerging. The decoration is only visible if the trough is raised above the level at which it could be conveniently used, suggesting that it was probably a cult object, rather than of practical use. It may have been a cult object in the Temple of Inana (Ishtar), the Sumerian goddess of love and fertility; a bundle of reeds (Inanna's symbol) can be seen projecting from the hut and at the edges of the scene. Later documents make it clear that Inanna was the supreme goddess of Uruk. Many finely-modelled representations of animals and humans made of clay and stone have been found in what were once enormous buildings in the centre of Uruk, which were probably temples. Cylinder seals of the period also depict sheep, cattle, processions of people and possibly rituals. Part of the right-hand scene is cast from the original fragment now in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

J. Black and A. Green, Gods, demons and symbols of -1 (London, The British Museum Press, 1992)

H.W.F. Saggs, Babylonians (London, The British Museum Press, 1995)

D. Collon, Ancient Near Eastern art (London, The British Museum Press, 1995)

H. Frankfort, The art and architecture of th (London, Pelican, 1970)

Life on the edge of the marshes (Edward Ochsenschlaer, 1998)![]() Another black & white view of the trough.

Another black & white view of the trough.

Sumerian mudhif facade, with uncut reed fonds and sheep entering, carved into a gypsum trough from Uruk, c. 3200 BCE (British Museum WA 12000). Photo source. Fig. 5B. Carved gypsum trough from Uruk. Two lambs exit a reed structure identifical to the present-day mudhif on this ceremonial trough from the site of Uruk in northern Iraq. Neither the leaves or plumes have been removed from the reds which are tied together to form the arch. As a result, the crossed-over, feathered reeds create a decorative pattern along the length of the roof, a style more often seen in modern animal shelters built by the Mi'dan. Dating to ca. 3000 BCE, the trough documents the extraordinry length of time, such arched reed buildings have been in use. (The British Museum BCA 120000, acg. 2F2077)

End of the Uruk trough. Length: 96.520 cm Width: 35.560 cm Height: 15.240 cm

![Image result for bharatkalyan97 mudhif]() 284 x 190 mm. Close up view of a Toda hut, with figures seated on the stone wall in front of the building. Photograph taken circa 1875-1880, numbered 37 elsewhere. Royal Commonwealth Society Library. Cambridge University Library. University of Cambridge.

284 x 190 mm. Close up view of a Toda hut, with figures seated on the stone wall in front of the building. Photograph taken circa 1875-1880, numbered 37 elsewhere. Royal Commonwealth Society Library. Cambridge University Library. University of Cambridge.

![]() The Toda mund, from, Richard Barron, 1837, "View in India, chiefly among the Nilgiri Hills'. Oil on canvas. The architecture of Iraqi mudhif and Toda mund -- of Indian linguistic area -- is comparable.

The Toda mund, from, Richard Barron, 1837, "View in India, chiefly among the Nilgiri Hills'. Oil on canvas. The architecture of Iraqi mudhif and Toda mund -- of Indian linguistic area -- is comparable.

The hut of a Toda Tribe of Nilgiris, India. Note the decoration of the front wall, and the very small door.

![]()

![]() Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.

m0702 Text 2206 showing Sign 39, a glyph which compares with the Sumerian mudhif structure.

- ढालकाठी [ ḍhālakāṭhī ] f ढालखांब m A flagstaff; esp.the pole for a grand flag or standard.

ढाल [ ḍhāla ] 'flagstaff' rebus: dhalako 'a large metal ingot (Gujarati) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati). The mudhif flag on the inscription is read rebus: xolā 'tail' Rebus: kole.l 'smithy, temple'. The structure is goṭ 'catttle-pen' (Santali) rebus: koṭṭhaka 'warehouse'. [kōṣṭhāgāra n. ʻ storeroom, store ʼ Mn. [kṓṣṭha -- 2, agāra -- ]Pa. koṭṭhāgāra -- n. ʻ storehouse, granary ʼ; Pk. koṭṭhāgāra -- , koṭṭhāra -- n. ʻ storehouse ʼ; K. kuṭhār m. ʻ wooden granary ʼ, WPah. bhal. kóṭhār m.; A. B. kuṭharī ʻ apartment ʼ, Or. koṭhari; Aw. lakh. koṭhārʻ zemindar's residence ʼ; H. kuṭhiyār ʻ granary ʼ; G. koṭhār m. ʻ granary, storehouse ʼ, koṭhāriyũ n. ʻ small do. ʼ; M. koṭhār n., koṭhārẽ n. ʻ large granary ʼ, -- °rī f. ʻ small one ʼ; Si. koṭāra ʻ granary, store ʼ.WPah.kṭg. kəṭhāˊr, kc. kuṭhār m. ʻ granary, storeroom ʼ, J. kuṭhār, kṭhār m.; -- Md. kořāru ʻ storehouse ʼ ← Ind.(CDIAL 3550)] Rebus: kuṭhāru 'armourer,

![]() Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.

Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.Text 1330 (appears with Zebu glyph) showing Sign 39. Pictorial motif: Zebu (Bos indicus) This sign is comparable to the cattle byre of Southern Mesopotamia dated to c. 3000 BCE. Rebus Meluhha readings of gthe inscription are from r. to l.: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS goṭ 'cattle-pen' rebus: koṭṭhāra 'warehouse' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' PLUS aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS kuṭika— 'bent' MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) PLUS kanka, karṇika कर्णिक 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale'. Read together with the fieldsymbol of the zebu,the message is: magnetite ore smithy, forge, warehouse, iron alloy metal, bronze merchandise (ready for loading as cargo).

goṭ = the place where cattle are collected at mid-day (Santali); goṭh (Brj.)(CDIAL 4336). goṣṭha (Skt.); cattle-shed (Or.) koḍ = a cow-pen; a cattlepen; a byre (G.) कोठी cattle-shed (Marathi) कोंडी [ kōṇḍī ] A pen or fold for cattle. गोठी [ gōṭhī ] f C (Dim. of गोठा) A pen or fold for calves. (Marathi)

koṭṭhaka1 (nt.) "a kind of koṭṭha," the stronghold over a gateway, used as a store -- room for various things, a chamber, treasury, granary Vin ii.153, 210; for the purpose of keeping water in it Vin ii.121=142; 220; treasury J i.230; ii.168; -- store -- room J ii.246; koṭthake pāturahosi appeared at the gateway, i. e. arrived at the mansion Vin i.291.; -- udaka -- k a bath -- room, bath cabinet Vin i.205 (cp. Bdhgh's expln at Vin. Texts ii.57); so also nahāna -- k˚ and piṭṭhi -- k˚, bath -- room behind a hermitage J iii.71; DhA ii.19; a gateway, Vin ii.77; usually in cpd. dvāra -- k˚ "door cavity," i. e. room over the gate: gharaŋ satta -- dvāra -- koṭṭhakapaṭimaṇḍitaŋ "a mansion adorned with seven gateways" J i.227=230, 290; VvA 322. dvāra -- koṭṭhakesu āsanāni paṭṭhapenti "they spread mats in the gateways" VvA 6; esp. with bahi: bahi -- dvārakoṭṭhakā nikkhāmetvā "leading him out in front of the gateway" A iv.206; ˚e thiṭa or nisinna standing or sitting in front of the gateway S i.77; M i.161, 382; A iii.30. -- bala -- k. a line of infantry J i.179. -- koṭṭhaka -- kamma or the occupation connected with a storehouse (or bathroom?) is mentioned as an example of a low occupation at Vin iv.6; Kern, Toev. s. v. "someone who sweeps away dirt." (Pali)

कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa, 'cattlepen', Mesopotamia Rebus: kundaṇa 'fine gold'

One-horned young bulls and calves are shown emerging out of कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa cattlepens heralded by Inana standards atop the mudhifs. The Inana standards are reeds with three rings. The reed standard is the same which is signified on Warka vase c. 3200–3000 BCE.

Warka vase also shows Indus Script hypertexts.

![]()

![]() Reed PLUS ring on Inanna standard on Warka vase.

Reed PLUS ring on Inanna standard on Warka vase.Scarf on the reeds: dhaṭu 'scarf' Rebus: dhatu 'mineral' (Santali) *dhaṭa2, dhaṭī -- f. ʻ old cloth, loincloth ʼ lex. [Drav., Kan. daṭṭi ʻ waistband ʼ etc., DED 2465]Ku. dhaṛo ʻ piece of cloth ʼ, N. dharo, B. dhaṛā; Or. dhaṛā ʻ rag, loincloth ʼ, dhaṛi ʻ rag ʼ; Mth. dhariā ʻ child's narrow loincloth ʼ.Addenda: *dhaṭa-- 2. 2. †*dhaṭṭa -- : WPah.kṭg. dhàṭṭu m. ʻ woman's headgear, kerchief ʼ, kc. dhaṭu m. (also dhaṭhu m. ʻ scarf ʼ, J. dhāṭ(h)u m. Him.I 105).(CDIAL 6707)

![]()

Hypertexts of goat and tiger atop fire-altars (with ore pellets) mlekh 'goat' rebus: milakkhu, mleccha'copper' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter'. Products (offerings) carried by worshippers in baskets and large storage jars and dedicated to Divinity Inanna clearly include metal ingots, as signified by the Indus Script hypertexts: copper ingots, iron (smelted) ingots.

One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meḍ (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream. It is significant that the word med in Slavic languages signifies copper.

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

http://www.vanderkrogt.net/elements/element.php?sym=Cu

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

Standard of Ur displays one-horned young bull, the Indian aurochs on a harp.

Figure 15.6. Tell al Ubaid, Temple of Ninhursag. Tridacna shell inlaid architectural frieze with bitumen and black shale. Early Dynastic period (ca. 2600 b.c.) (Hall and Woolley 1927)

Figure 15.5. Tell al Ubaid, Temple of Ninhursag. Tridacna shell-inlaid architectural frieze with bitumen and black shale. Early Dynastic period (ca. 2600 b.c.e.) (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

A lyrist on the Standard of Ur, believed to date to between 2600–2400 BCE. "There are several hypotheses as to the origin of the instrument. One suggests that it descended from the kopuz, a string instrument still in use among the Turkic peoples of Central Asia and the Caspian region.[1] The name itself derives from the tanbur (tunbur). Tanbur in turn might have descended from the Sumerian pantur." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_tambur Hieroglyph: kã̄ḍ reed Rebus: kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Hieroglyph: tanbūra 'lyre' Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper'.

![Mesopotamia. Estandarte de Ur. Lapislázuli, piedra caliza y conchas]()

![]() An orthographic composition to createa hypertext with hieroglyphs of animal parts or device components is called सांगड sāṅgaḍa m f (संघट्ट S) f A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together. The word also signifies 'that member of a turner's apparatus by which the piece to be turned is confined and steadied. सांगडीस धरणें To take into linkedness or close connection with, lit. fig.'(Marathi) A number of rebus readings related to metalwork, trade transactions, fortified locations of workshops are: sanghar 'fortification' (Pashto) A number of homonyms signify specific trade terms: jangadiyo 'military guard carrying treasure into the treasury' (Gujarati) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati).The mercantile agents who were jangadiyo received goods on jangad 'entrusted for approval'. An ancient Near East accounting system was jangaḍ. The system of jangaḍ simply meant 'goods on approval' with the agent -- like the Meluhhan merchant-agents or brokers living in settlements in ancient near East -- merely responsible for showing the goods to the intended buyers. సంగడము (p. 1272) saṅgaḍamu sangaḍamu. [from Skt. సంగతమ్.] n. Dumb-bells, సాముచేయువారు తిప్పేలోడు. Help, assistance, aid, సహాయము. Friendship, త, స్నేహము. Meeting, చేరిక. Nearness, సమీపము. A retinue, పరిచారము. Service, సేవ. An army, సేన. "అనవుడు వాడునగుచు నీవిక్రమంబునకు నా వెరపు సంగడంబుగాదె." M. VII. iv. 59. "ఉ అంచెలుగట్టి కాలి తొడుసైచనననీవుగదమ్మప్రోదిరా, యంచలివేటి సంగడములయ్యెను." Swa. v. 72. Trouble, annoyance, ంాటము, సంకటము. సంగడమువాడు sangaḍamu-vāḍu. n. A friend or companion. చెలికాడు, నేస్తకాడు. సంగడి sangaḍi. n. A couple, pair, ంట త, ోడు. Friendship, స్నేహము. A friend, a fellow, a playmate, నేస్తకాడు. A raft or boat made of two canoes fastened side by side. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-jangad-accounting-for.html sãgaḍ f. ʻ a body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together, part of a turner's apparatus ʼ, m.f. ʻ float made of two canoes joined together ʼsaṁghāṭa m. ʻ fitting and joining of timber ʼ R. sãgaḍ māṇi 'alloying adamantine glue, सं-घात caravan standard' -- vajra saṁghāṭa in archaeometallurgy. sangar̥h 'proclamation, trade.' sãgaṛh 'fortification'

An orthographic composition to createa hypertext with hieroglyphs of animal parts or device components is called सांगड sāṅgaḍa m f (संघट्ट S) f A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together. The word also signifies 'that member of a turner's apparatus by which the piece to be turned is confined and steadied. सांगडीस धरणें To take into linkedness or close connection with, lit. fig.'(Marathi) A number of rebus readings related to metalwork, trade transactions, fortified locations of workshops are: sanghar 'fortification' (Pashto) A number of homonyms signify specific trade terms: jangadiyo 'military guard carrying treasure into the treasury' (Gujarati) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati).The mercantile agents who were jangadiyo received goods on jangad 'entrusted for approval'. An ancient Near East accounting system was jangaḍ. The system of jangaḍ simply meant 'goods on approval' with the agent -- like the Meluhhan merchant-agents or brokers living in settlements in ancient near East -- merely responsible for showing the goods to the intended buyers. సంగడము (p. 1272) saṅgaḍamu sangaḍamu. [from Skt. సంగతమ్.] n. Dumb-bells, సాముచేయువారు తిప్పేలోడు. Help, assistance, aid, సహాయము. Friendship, త, స్నేహము. Meeting, చేరిక. Nearness, సమీపము. A retinue, పరిచారము. Service, సేవ. An army, సేన. "అనవుడు వాడునగుచు నీవిక్రమంబునకు నా వెరపు సంగడంబుగాదె." M. VII. iv. 59. "ఉ అంచెలుగట్టి కాలి తొడుసైచనననీవుగదమ్మప్రోదిరా, యంచలివేటి సంగడములయ్యెను." Swa. v. 72. Trouble, annoyance, ంాటము, సంకటము. సంగడమువాడు sangaḍamu-vāḍu. n. A friend or companion. చెలికాడు, నేస్తకాడు. సంగడి sangaḍi. n. A couple, pair, ంట త, ోడు. Friendship, స్నేహము. A friend, a fellow, a playmate, నేస్తకాడు. A raft or boat made of two canoes fastened side by side. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-jangad-accounting-for.html sãgaḍ f. ʻ a body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together, part of a turner's apparatus ʼ, m.f. ʻ float made of two canoes joined together ʼsaṁghāṭa m. ʻ fitting and joining of timber ʼ R. sãgaḍ māṇi 'alloying adamantine glue, सं-घात caravan standard' -- vajra saṁghāṭa in archaeometallurgy. sangar̥h 'proclamation, trade.' sãgaṛh 'fortification'

The standard device is a composite of two hieroglyphs, 1. portable furnace; and 2. lathe

Hieroglyph 1: కమటము kamaṭamu. [Tel.] n. A portable furnace for melting the precious metals. అగసాలెవాని కుంపటి. "చ కమటము కట్లెసంచియొరగల్లును గత్తెర సుత్తె చీర్ణముల్ ధమనియుస్రావణంబు మొలత్రాసును బట్టెడ నీరుకారు సా నము పటుకారు మూస బలునాణె పరీక్షల మచ్చులాదిగా నమరగభద్రకారక సమాహ్వయు డొక్కరుడుండు నప్పురిన్"హంస. ii. Rebus:Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236) కమ్మటము kammaṭamu Same as కమటము. కమ్మటీడు kammaṭīḍu. [Tel.] A man of the goldsmith caste. R

Hieroglyph 2: sãghāṛɔ 'lathe' (Gujarati).Rebus: sanghar'fortification' (Pashto) See:

Vajra Sanghāta 'binding together' (Varahamihira) *saṁgaḍha ʻ collection of forts ʼ. [*gaḍha -- ]L. sãgaṛh m. ʻ line of entrenchments, stone walls for defence ʼ.(CDIAL 12845). సంగడము (p. 1279) [ saṅgaḍamu ] A raft or boat made of two canoes fastened side by side. రెండుతాటి. బొండులు జతగాకట్టినతెప్ప சங்கடம்² caṅkaṭam, n. < Port. jangada. Ferry-boat of two canoes with a platform thereon; இரட்டைத்தோணி. (J.) G. sãghāṛɔ m. ʻ lathe ʼ; M. sãgaḍ f. ʻ a body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together, part of a turner's apparatus ʼ, m.f. ʻ float made of two canoes joined together ʼsaṁghāṭa m. ʻ fitting and joining of timber ʼ R. [√ghaṭ] LM 417 compares saggarai at Limurike in the Periplus, Tam. śaṅgaḍam, Tu. jaṅgala ʻ double -- canoe ʼ),sã̄gāḍā m. ʻ frame of a building ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ lathe ʼ; Si. san̆gaḷa ʻ pair ʼ, han̆guḷa, an̆g° ʻ double canoe, raft ʼ.(CDIAL 12859) Cangavāra [cp. Tamil canguvaḍa a dhoney, Anglo-- Ind. ḍoni, a canoe hollowed from a log, see also doṇi] a hollow vessel, a bowl, cask M i.142; J v.186 (Pali)

Hieroglyph: खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. खोंडरूं [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा-cowl (Marathi. Molesworth); kōḍe dūḍa bull calf (Telugu); kōṛe 'young bullock' (Konda)Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali)

kāṇḍam காண்டம்² kāṇṭam, n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர். துருத்திவா யதுக்கிய குங்குமக் காண் டமும் (கல்லா. 49, 16). Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘metal tools, pots and pans’ (Marathi) (B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See `to be left over'. @B24310. #20851. Re(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See`to be left over'. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) The hieroglyph clearly refers to the metal tools, pots and pans of copper.

Section 1. Archaeobotany

Archaeobotany is a sub-specialization within environmental archaeology that studies human interactions with plants in the past. The hieroglyph on the body of the one-horned young bull is identified as calotropis gigantea leaf (arka) read rebus as arka'copper,gold' The 'arka' design on the body (to signify arka 'sun's rays' a homonym of arka'gold, copper'. అగసాలిagasāli or అగసాలెవాడు agasāli. [Tel.] n. A goldsmith. కంసాలివాడు. Orthography of the leaf is a continuous line with rows to signify short linear, angular strokes like sun's rays (arka) which evokes the word sāl, 'joining line'. Thus, arka + sāl is used as an expression: akasāle, 'goldsmith shop'.

![]()

![]()

The hieroglyph on the body of the young bull is:

अर्क the plant Calotropis Gigantea (the larger leaves are used for yajña performances ;

cf. अर्क-कोशी , -पर्ण्/अ , पलश्/अ ,&c below)

S3Br. &c , a religious ceremony

S3Br. Br2A1rUp. (

cf. अर्का*श्वमेध below) अर्क--पर्ण

n. the leaf of the अर्क plant

S3Br. Ka1tyS3r.; -पलाश

n. (for 1. » under पल) a leaf , petal , foliage (

ifc. f(ई)

. )

S3Br. Gr2S3rS. MBh. &c; अर्क--कोशी

f. a bud of the अर्क plant

S3Br. x. Rebus:

अर्क fire

RV. ix , 50 , 4

S3Br. Br2A1rUp.; the sun

RV. &c;

m. ( √ अर्च्) , Ved. a ray , flash of lightning

RV. &c; अर्का* श्व-मेध

m. du.([

Pa1n2. 2-4 , 4

Ka1s3. ]) or °ध्/औ ([

AV. xi , 7 , 7 , and

S3Br. ]), the अर्क ceremony and the अश्वमेध

yajña. (Note: This is a clear indicator that अश्वमेध is only a Chandas (Veda) metaphor and DOES NOT involve a horse sacrifice).

वराह-मिहिर 's बृहज्जातक explains अश्व as a hieroglyph of the archer (in the Zodiac)(Monier-Williams); अश्व as a symbolic expression to signify the number seven: aśvḥ अश्वः [अश्नुते अध्वानं व्याप्नोति, महाशनो वा भवति Nir.; अश्-क्वन् Uṇ.1.149] 1 A horse; the horses are said to have 7 breeds:- अमृताद् बाष्पतो वह्नेर्वेदेभ्यो$ण़्डाच्च गर्भतः । साम्नो हयानामुत्पत्तिः सप्तधा परिकीर्तिता ॥A symbolical expression for the number 'seven' (that being the number of the horses of the Sun) सूर्याश्वैर्मसजस्तताः सगुरवः शार्दूलविक्रीडितम् V. Ratn. -मेधः [अश्वः प्रधानतया मेध्यते हिंस्यते$त्र, मेध् हिंसने घञ्] a horse-sacrifice; यथाश्वमेधः क्रतुराट् सर्वपापापनोदनः Ms.11.26. [In Vedic times this sacrifice was performed by kings desirous of offspring; but subsequently it was performed only by kings and implied that he who instituted it, was a conqueror and king of kings. A horse was turned loose to wander at will for a year, attended by a guardian; when the horse entered a foreign country, the ruler was bound either to submit or to fight. In this way the horse returned at the end of a year, the guardian obtaining or enforcing the submission of princes whom he brought in his train. After the successful return of the horse, the rite called Aśvamedha was performed amidst great rejoicings. It was believed that the performance of 1 such yajña would lead to the attainment of the seat or world of Indra, who is, therefore, always represented as trying to prevent the completion of the hundredth sacrifice. cf. Rv.1.162-163 hymns; Vāj.22 seq.](Apte)

![]()

Gold Pendant From Harappa , Sarasvati Civilization ( Photo - National Museum Delhi )

I am baffled by the unique hieroglyph.![Inline image Inline image]() Sign 323 of Indus Script inverted on the body of the bull. Maybe, the word 'arka' was a synonym of kundaṇa, fine gold' (Tulu)

Sign 323 of Indus Script inverted on the body of the bull. Maybe, the word 'arka' was a synonym of kundaṇa, fine gold' (Tulu)

A synonym for gold is -- kundaṇa pure gold(Tulu) PLUS sack on the shoulder constitute hieroglyphs (semantic, phonetic determinants). खोंडरूं [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा-cowl.खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.)

Thus, I suggest that the hypertext of one-horned young bull with a design of arka leaf reads: arka kundaṇa 'goldsmith guild' PLUS koḍ 'horn' rebus koḍ 'workshop', since the Marathi word has the meaning: कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa f A fold or pen.Thus, the seal with the one-horned young bull is signifier of a goldsmith guild workshop.

Arka is the gigantic Swallow wort. Aselepias gigantea. Rox. ii. 30. and ii. 7. Calotropis gigantea (Watts.)

This is calatropis procera' arka in Kannda is ekke plant

எருக்கு¹ erukku , n. prob. arka. [M. erik- ku.] Yarcum, madar, m. sh., Calotropis gigantea; செடிவகை. எருக்கின் முகிழ்நோக்கும் (தணிகைப்பு. களவு. 274). ![]()

![]()

arká2 m. ʻ the plant Calotropis gigantea ʼ ŚBr. [Cf. alarka -- 2 m. Suśr., alāka -- m. Car., Pa. alakka -- m.]Pa. Pk. akka -- m.; S. aku m. ʻ Calotropis procera ʼ, L. akk m., awāṇ. ak; P. akk m. ʻ a partic. plant with an acrid milky juice ʼ; Garh. Ku. ã̄k ʻ C. gigantea ʼ, N. āk ʻ C. acia ʼ; H. āk, ākh m. ʻ C. gigantea ʼ; Marw. āk ʻ C. acia ʼ; G. āk m., ākṛɔ m. ʻ a partic. tree or shrub ʼ; Si. aka ʻ the tree Asclepias gigantea ʼ.arkaparṇá -- , arkapādapa -- .Addenda: arká -- 2: S.kcch. akk m. ʻ Calotropis gigantea ʼ, OMarw. āka m. ʻ swallow -- wort ʼ.(CDIAL 625)If the 'heart design' signifies arka leaf, it can be related to The Surya Siddhanta definition of Uttarāyaṇa or Uttarayan as the period between the Makara Sankranti (which currently occurs around January 14) and Karka Sankranti (which currently occurs around July 16). (Burgess, Ebenezer (1858). The Surya Siddhantha - A Textbook of Hindu Astronomy. American Oriental Society. Chapter 14, Verse 7-9.Se)

Section 2. Archaeozoology

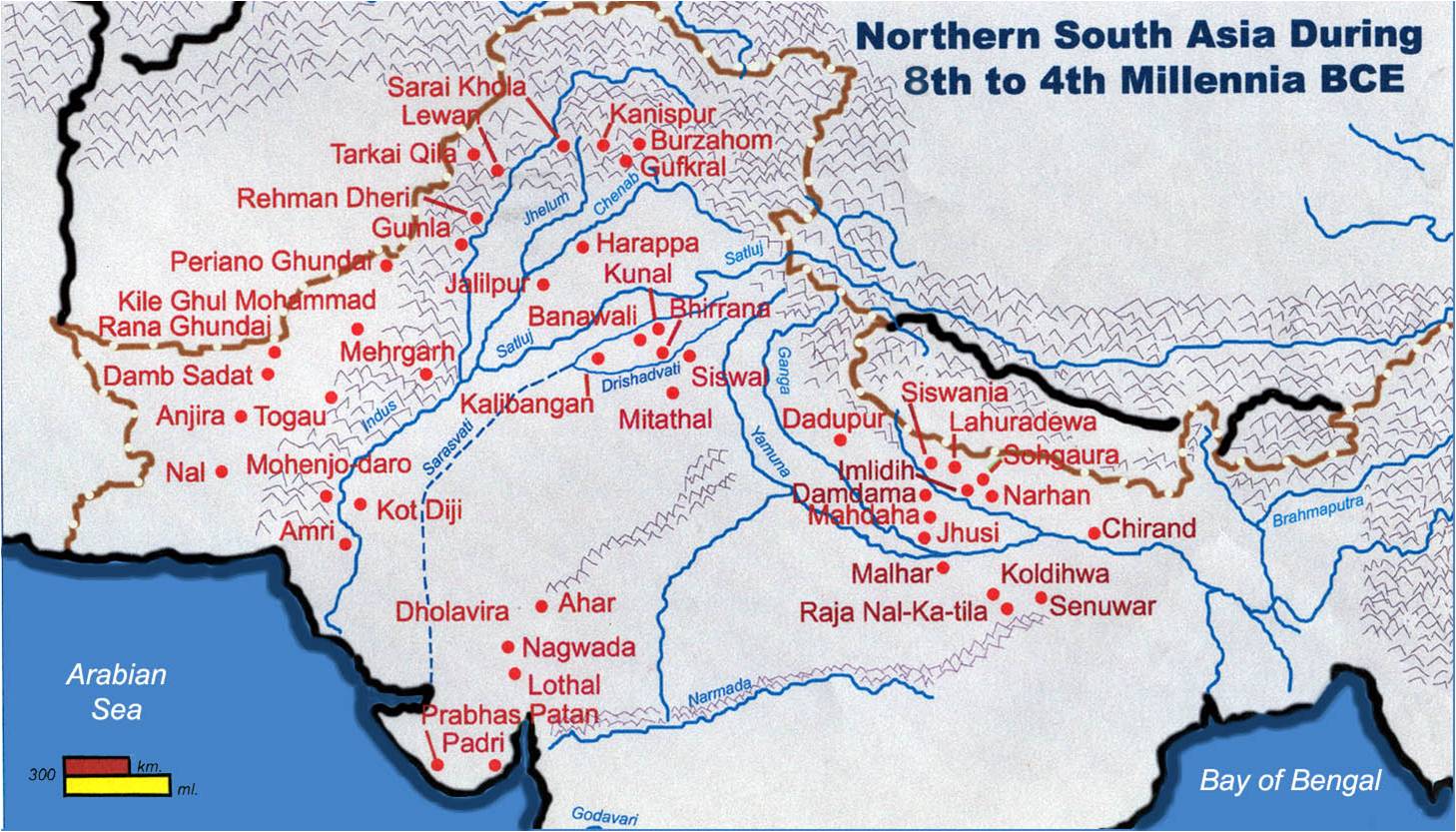

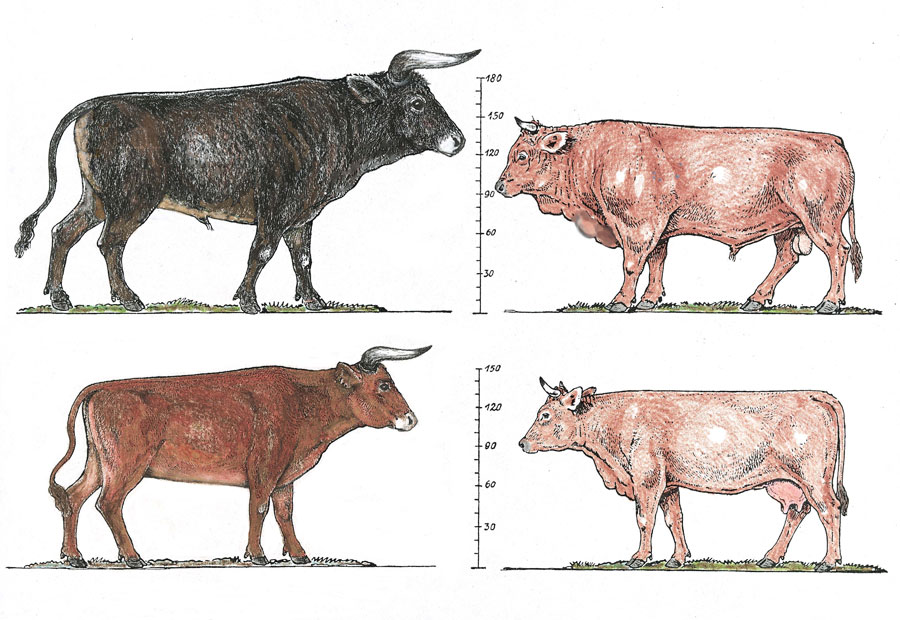

Archaeozoology is the study of animals in archaeological contexts. The young bull with one curved horn is identified as bos aurochs, a species of the genus bos. Indian aurochs is sometimes regarded as a distinct species.

Restoration of the aurochs based on a bull skeleton from Lund and a cow skeleton from Cambridge, with chart of characteristic external features of the aurochs

Comparison of bull and cow of the aurochs (left) and modern cattle (right). Image: Courtesy T. Van Vuure

Cro-Magnon graffito of Bos primigenius in Grotta del Romito, Papasidero, Italy

The Indian aurochs (B. p. namadicus) once inhabited India. It was the first subspecies of the aurochs to appear, at 2 million years ago, and from about 9000 years ago, it was domesticated as the zebu.(In the Light of Evolution III: Two Centuries of Darwin. National Academies Press. 2009. p. 96.) Fossil remains indicate wild Indian aurochs besides domesticated zebu cattle were in Gujarat and the Ganges area until about 4–5000 years ago. Remains from wild aurochs 4400 years old are clearly identified from Karnataka

in South India.(Shanyuan Chen, et al, "Zebu Cattle Are an Exclusive Legacy of the South Asia Neolithic", Mol Biol Evol (2010) 27(1): 1-6 ).

Indian zebu, although domesticated eight to ten thousand years ago, are related to aurochs that diverged from the Near Eastern ones some 200,000 years ago. African cattle are thought to have descended from aurochs more closely related to the Near Eastern ones. The Near East and African aurochs groups are thought to have split some 25,000 years ago, probably 15,000 years before domestication. The "Turano-Mongolian" type of cattle now found in northern China, Mongolia, Korea, and Japan may represent a fourth domestication event (and a third event among B. taurus–type aurochs). This group may have diverged from the Near East group some 35,000 years ago. Whether these separate genetic populations would have equated to separate subspecies is unclear. (Hideyuki Mannen; et al. (August 2004). "Independent mitochondrial origin and historical genetic differentiation in North Eastern Asian cattle" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, Volume 32, issue 2. pp. 539–544.)

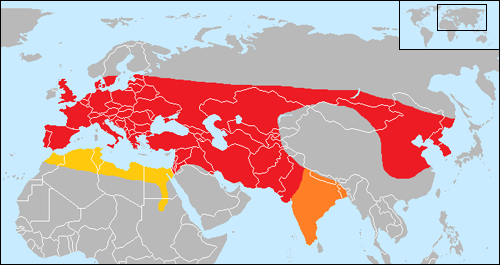

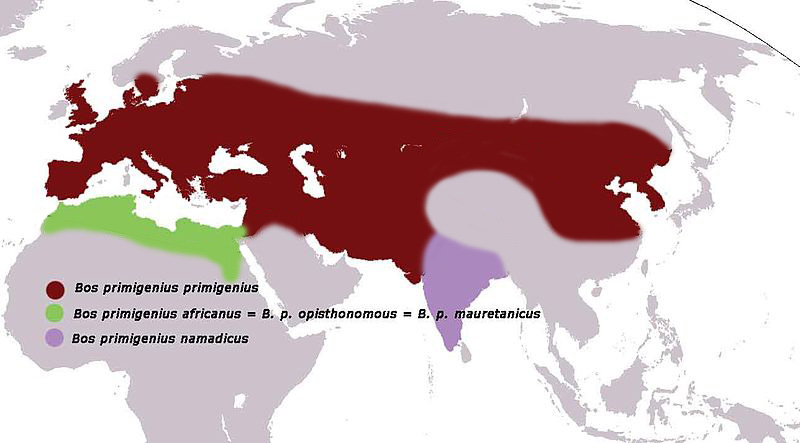

The maximum range of the aurochs was from Europe (excluding Ireland and northern Scandinavia), to northern Africa, the Middle East, India, and Central Asia.("History, Morphology And Ecology Of The Aurochs"(PDF) (McKenzie, Steven (17 February 2010). "Ancient giant cattle genome first". BBC News.) Until at least 3,000 years ago, the aurochs was also found in eastern China, where it is recorded at the Dingjiabao Reservoir in Yangyuan County. Most remains in China are known from the area east of 105°E, but the species has also been reported from the eastern margin of the Tibetan plateau, close to the Heihe River.(Zong, G (1984). A record of Bos primigenius from the Quaternary of the Aba Tibetan Autonomous Region, Volume XXII No. 3. Vertebrata PalAsiatica. pp. 239–245.)In Japan, excavations in various locations such as in Iwate and Tochigi prefectures have found aurochs which may have herded with steppe bisons.(HASEGAWA Y.,OKUMURA Y., TATSUKAWA H. (2009). "First record of Late Pleistocene Bison from the fissure deposits of the Kuzuu Limestone, Yamasuge,Sano-shi,Tochigi Prefecture,Japan" (pdf). Bull.Gunma Mus.Natu.Hist.(13). Gunma Museum of Natural History and Kuzuu Fossil Museum: 47–52.). ![]()

The Vig-aurochs, one of two very well-preserved aurochs skeletons found in Denmark. The circles indicate where the animal was wounded by arrows.

The violent cup of Vaphio showing aurochs hunting, Greece, (15th century BCE)

“Several ancient Babylonian sculptures or cylinder seals and many later Assyrian sculptures show very realistic pictures of a wild bovine, which I formerly identified with Bos primigenius Bojanus (plate 83, fig.1). My recent studies on fossil remains of the bovines of the Indian Pleistocene have shown me that the Indian (Narbada and Siwaliks) and China Taurina are the exact equivalent of te European urus (Bos primigenius Bojanus), excepting some slight variations produced by different geographical and local influences so that the Bos namadicus Falconer Cautley would represent the European urus for the Asiatic continent, especially the North Indian mountains and their neighborhood (compare fig. 490 with plate 81).” (Raphael Pumpelly: Explorations in Turkestan : Expedition of 1904 : vol.2, p. 361 http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/VIII-5-A-a-3/V-2/page-hr/0167.html.en, p. 361).

Holocene aurochs bull skull in Berlin

Aurochs

1627 (wild form) resp. Present (domestic form)

The Prejlerup-aurochs, a bull at the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen from 7400 BCE

Life restoration of an aurochs bull found in Braunschweig, Germany The inscription reads: "The Aurochs – Bos primigenius bojanus, the ancestor of domestic cattle, lived in this forest Jaktorów until the year 1627."

Speculative life restoration of the enigmatic Indian aurochs (B. p. namadicus) ![Image result for bos aurochs]()

![]()

"The Indian aurochs (Bos primigenius namadicus) was a subspecies of the extinct aurochs. It is considered as the ancestor of the zebu cattle, which is mainly found in southern Asia and has been introduced in many other parts of the world, like Africa and South America. In contrast, the taurine cattle breeds, which are native to Europe, the Near East, and other parts of the world, are descendants of the Eurasian aurochs (Bos primigenuis primigenius). According to IUCN, the Indian aurochs disappeared sometime until the 13th century AD, when the only subspecies standing was the Bos primigenius primigenius.(Tikhonov, A. (2008). "Bos primigenius". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.)...The Indian aurochs diverged from the Eurasian aurochs (B. p. primigenius) about 100,000 - 200,000 years ago. This has been shown by comparison of DNA from zebus and taurine cattle breeds, the living descendants of these two aurochs forms.(Verkaar, Nijman, Beeke, Hanekamp & Lenstra: Maternal and Paternal Lineages in Cross-breeding bovine species. Has Wisent a Hybrid Origin?.2004.) The Indian aurochs is sometimes regarded as a distinct species.(MacHugh et al., 1997: Microsatellite DNA Variation and the Evolution, Domestication and Phylogeography of Taurine and Zebu Cattle (Bos taurus and Bos indicus). Genetics, Vol. 146, 1071–1086. )Zebu cattle are phenotypically distinguished from taurine cattle by the presence of a prominent shoulder hump.(Loftus et al., 1994: Evidence for two independent domestications of cattle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 91.7: 2757-2761.)"

"The aurochs originated about 2 million years ago in India and spread westwards.(Cis van Vuure: Retracing the Aurochs - History, Morphology and Ecology of an extinct wild Ox.2005.) The Indian aurochs roamed in the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs throughout the Indian subcontinent from Baluchistan, the Indus valley and the Ganges valley to south India. Most remains are from the north of India, on the Kathiawar Peninsula, along the Ganges, and from the area of the Narmada River. However, bone remains of the Indian aurochs are present in the south as well, such as the Deccan area and along the Krishna area. The wild Indian aurochs survived into neolithic times, when it was domesticated. The youngest known remains, which clearly belong to wild Indian aurochs are from Banahalli in Karnataka, southern India, with an age of about 4200 years old...The first centre for domestication of the Indian aurochs was probably the Baluchistan region in Pakistan. The domestication process seems to have been prompted by the arrival of new crop species from the Near East around 7000 BC. It is possible, that Indian aurochs were domesticated independently in Southern India, in Gujarat and the Ganges floodplains. Domestic zebu are recorded from the Indus region since 6000 BC and from south India, the middle Ganges region, and Gujarat since 2000-3500 BC. Domestic cattle seem to have been absent in southern China and southeast Asia until 2000-1000 BCE.(Chen et al., 2010: Zebu cattle are an exclusive legacy of the South Asia Neolithic. Molecular biology and evolution, 27(1), 1-6.)"

![]()

Known locations of Bos Primigenius according to historical records. Image from Maas, P.H.J. (2011).

Distribution of the three sub-species.

Subspecise

Bos primigenius (Bojanus 1827)

Wild:

domestic:

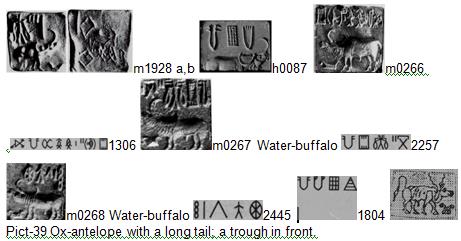

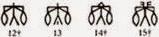

Section 3. Orthography of the Field Symbol of One-horned young bull

![]() Field Symbol 59

Field Symbol 59![]()

![Image result for Pict mahadevan bharatkalyan97]()

![]() Field Symbol 62 Mohenjo-daro seal m417 six heads from a core.

Field Symbol 62 Mohenjo-daro seal m417 six heads from a core.

sãgaḍ f. ʻa body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together' (Marathi). This gloss sãgaḍ as a body of written or pictorial material of hieroglyphs (voiced in Meluhha speech) can be used to create a ciphertext with elements of enhanced cyber-security encryptions. This ciphertext can be called: Hieroglyphmultiplextext. Rebus 1: sãgaḍ māṇi 'alloying adamantine glue, सं-घात caravan standard' -- vajra saṁghāṭa in archaeometallurgy, deciphered in Indus Script Corpora. Enhanced encryption cyber-security. Rebus 2: जांगड [jāṅgaḍa] ad Without definitive settlement of purchase--goods taken from a shop. जांगड [ jāṅgaḍa ] f ( H) Goods taken from a shop, to be retained or returned as may suit: also articles of apparel taken from a tailor or clothier to sell for him. 2 or जांगड वही The account or account-book of goods so taken.Rebud 3: sangaDa 'a cargo boat'. Rebus 4: sangaRh 'proclamation'.

śrēṇikā -- f. ʻ tent ʼ lex. and mngs. ʻ house ~ ladder ʼ in *śriṣṭa -- 2, *śrīḍhi -- . -- Words for ʻ ladder ʼ see śrití -- . -- √śri]H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ; Si. hiṇi, hiṇa, iṇi ʻ ladder, stairs ʼ (GS 84 < śrēṇi -- ).(CDIAL 12685). Woṭ. Šen ʻ roof ʼ, Bshk. Šan, Phal. Šān(AO xviii 251) Rebus: seṇi (f.) [Class. Sk. Śreṇi in meaning “guild”; Vedic= row] 1. A guild Vin iv.226; J i.267, 314; iv.43; Dāvs ii.124; their number was eighteen J vi.22, 427; VbhA 466. ˚ -- pamukha the head of a guild J ii.12 (text seni -- ). — 2. A division of an army J vi.583; ratha -- ˚ J vi.81, 49; seṇimokkha the chief of an army J vi.371 (cp. Senā and seniya). (Pali)

*śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ. [Cf. śrētr̥ -- ʻ one who has recourse to ʼ MBh. -- See śrití -- . -- √śri]Ash. ċeitr ʻ ladder ʼ (< *ċaitr -- dissim. from ċraitr -- ?).(CDIAL 12720) *śrēṣṭrī2 ʻ line, ladder ʼ. [For mng. ʻ line ʼ conn. with √śriṣ2 cf. śrḗṇi -- ~ √śri. -- See śrití -- . -- √śriṣ2]Pk. sēḍhĭ̄ -- f. ʻ line, row ʼ (cf. pasēḍhi -- f. ʻ id. ʼ. -- < EMIA. *sēṭhī -- sanskritized as śrēḍhī -- , śrēṭī -- , śrēḍī<-> (Col.), śrēdhī -- (W.) f. ʻ a partic. progression of arithmetical figures ʼ); K. hēr, dat. °ri f. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 12724) Rebus: śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ]Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ, seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M.śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2?)(CDIAL 12726)

This denotes a mason (artisan) guild -- seni -- of 1. brass-workers; 2. blacksmiths; 3. iron-workers; 4. copper-workers; 5. native metal workers; 6. workers in alloys.

The core is a glyphic ‘chain’ or ‘ladder’. Glyph: kaḍī a chain; a hook; a link (G.); kaḍum a bracelet, a ring (G.) Rebus: kaḍiyo [Hem. Des. kaḍaio = Skt. sthapati a mason] a bricklayer; a mason; kaḍiyaṇa, kaḍiyeṇa a woman of the bricklayer caste; a wife of a bricklayer (G.)

The glyphics are:

1. Glyph: ‘one-horned young bull’: kondh ‘heifer’. kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’; arka kundaṇa'goldsmith guild' PLUS koḍ 'horn' rebus koḍ 'workshop' See:

One-horned young bull is Indus Script hypertext; semantic determinant hieroglyphs, fine gold, sack, young bull, one horn rebus arka kundaṇa 'goldsmith guild'.

2. Glyph: ‘bull’: ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’. koḍ 'horns' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'

3. Glyph: ‘ram’: meḍh ‘ram’. Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’

4. Glyph: ‘antelope’: mr̤eka ‘goat’. Rebus: milakkhu ‘copper’. Vikalpa 1: meluhha ‘mleccha’ ‘copper worker’. Vikalpa 2: meṛh ‘helper of merchant’.

5. Glyph: ‘zebu’: khũṭ ‘zebu’. Rebus: khũṭ ‘guild, community’ (Semantic determinant of the ‘jointed animals’ glyphic composition). kūṭa joining, connexion, assembly, crowd, fellowship (DEDR 1882) Pa. gotta ‘clan’; Pk. gotta, gōya id. (CDIAL 4279) Semantics of Pkt. lexeme gōya is concordant with Hebrew ‘goy’ in ha-goy-im (lit. the-nation-s). Pa. gotta -- n. ʻ clan ʼ, Pk. gotta -- , gutta -- , amg. gōya -- n.; Gau. gū ʻ house ʼ (in Kaf. and Dard. several other words for ʻ cowpen ʼ > ʻ house ʼ: gōṣṭhá -- , Pr. gūˊṭu ʻ cow ʼ; S. g̠oṭru m. ʻ parentage ʼ, L. got f. ʻ clan ʼ, P. gotar, got f.; Ku. N. got ʻ family ʼ; A. got -- nāti ʻ relatives ʼ; B. got ʻ clan ʼ; Or. gota ʻ family, relative ʼ; Bhoj. H. got m. ʻ family, clan ʼ, G. got n.; M. got ʻ clan, relatives ʼ; -- Si. gota ʻ clan, family ʼ ← Pa. (CDIAL 4279). Alternative: adar ḍangra ‘zebu or humped bull’; rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.); ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’ (H.)

6. The sixth animal can only be guessed. Perhaps, a tiger (A reasonable inference, because the glyph ’tiger’ appears in a procession on some Indus script inscriptions. Glyph: ‘tiger?’: kol ‘tiger’.Rebus: kol ’worker in iron’. Vikalpa (alternative): perhaps, rhinoceros. gaṇḍa ‘rhinoceros’; rebus:khaṇḍ ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’. Thus, the entire glyphic composition of six animals on the Mohenjodaro seal m417 is semantically a representation of a śrḗṇi, ’guild’, a khũṭ , ‘community’ of smiths and masons.

bhaTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' Also, baTa 'six' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'.

See: ![]() m0491

m0491![]() Field Symbol FS 58

Field Symbol FS 58 Field Symbol Fig. 94

![]() Field Symbol 58

Field Symbol 58![]() Field Symbol 55 Mohenjo-daro Seal impression. m0296 Two heads of one-horned bulls with neck-rings, joined end to end (to a standard device with two rings coming out of the top part?), under a stylized tree-branch with nine leaves.

Field Symbol 55 Mohenjo-daro Seal impression. m0296 Two heads of one-horned bulls with neck-rings, joined end to end (to a standard device with two rings coming out of the top part?), under a stylized tree-branch with nine leaves.

खोंद [ khōnda ] n A hump (on the back): also a protuberance or an incurvation (of a wall, a hedge, a road). Rebus: खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i (

H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or -पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe.

गोट [ gōṭa ] m (

H) A metal wristlet. An ornament of women. 2 Encircling or investing. v घाल, दे. 3 An encampment or camp: also a division of a camp. 4 The hem or an appended border (of a garment).गोटा [ gōṭā ] m A roundish stone or pebble. 2 A marble (of stone, lac, wood &c.) 3 fig. A grain of rice in the ear. Ex. पावसानें भाताचे गोटे झडले. An overripe and rattling cocoanut: also such dry kernel detached from the shell. 5 A narrow fillet of brocade.गोटाळ [ gōṭāḷa ] a (गोटा) Abounding in pebbles--ground.गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A roundish stone or pebble. 2 A marble. 3 A large lifting stone. Used in trials of strength among the Athletæ. 4 A stone in temples described at length under उचला 5 fig. A term for a round, fleshy, well-filled body.

Rebus: गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe.

Hieroglyph: lo = nine (Santali); no = nine (B.) on-patu = nine (Ta.)

[Note the count of nine fig leaves on m0296] Rebus: loa = a

species of fig tree, ficus glomerata,

the fruit of ficus glomerata (Santali.lex.)

![]() kana, kanac =

kana, kanac =corner (Santali); Rebus: kan~cu

= bronze (Te.) ![]() Ligatured glyph. ara 'spoke' rebus: ara 'brass'. era, er-a = eraka =

Ligatured glyph. ara 'spoke' rebus: ara 'brass'. era, er-a = eraka = ?nave; erako_lu = the iron axle of a carriage (Ka.M.); cf. irasu (Ka.lex.)

[Note Sign 391 and its ligatures Signs 392 and 393 may connote a spoked-wheel,

nave of the wheel through which the axle passes; cf. ara_, spoke]erka = ekke (Tbh.

of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal);

crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any

metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) Rebus: eraka

= copper (Ka.)eruvai =copper (Ta.); ere - a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a = syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.)Vikalpa: ara, arā (RV.) = spoke

of wheel ஆரம்² āram , n. < āra. 1. Spoke of a wheel. See ஆரக்கால். ஆரஞ்சூழ்ந்தவயில்வாய்நேமியொடு (சிறுபாண். 253). Rebus: ஆரம்

brass; பித்தளை.(அக. நி.)

![]() kuṭi = a

kuṭi = aslice, a bit, a small piece (Santali.lex.Bodding) Rebus: kuṭhi

‘iron smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṭhī

factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546)

![]() Thus, the sign sequence

Thus, the sign sequenceconnotes a copper, bronze, brass smelter furnace

![]() Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa

Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa‘arrow’; rebus: ayaskāṇḍa. The sign sequence is ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron,

excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) ayo, hako 'fish'; a~s = scales of fish (Santali); rebus:

aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) kaṇḍa

‘fire-altar’ (Santali) DEDR 191 Ta. ayirai,

acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitis

thermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma. ayala a fish,

mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind of

small fish, loach.

![]() kole.l 'temple, smithy'

kole.l 'temple, smithy'(Ko.); kolme ‘smithy' (Ka.) kol ‘working in iron, blacksmith (Ta.); kollan-

blacksmith (Ta.); kollan blacksmith, artificer (Ma.)(DEDR 2133) kolme =

furnace (Ka.) kol = pan~calo_ha (five

metals); kol metal (Ta.lex.) pan~caloha = a metallic alloy

containing five metals: copper, brass, tin, lead and iron (Skt.); an

alternative list of five metals: gold, silver, copper, tin (lead), and iron

(dhātu; Nānārtharatnākara. 82; Man:garāja’s Nighaṇṭu.

498)(Ka.) kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, an aboriginal tribe if iron smelters speaking

a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali)

![]()

![]() Field Symbol 54 m297a: Seal h1018a: copper plate

Field Symbol 54 m297a: Seal h1018a: copper plate

A lexeme for a Gangetic/Indus river octopus is retained as a cultural memory only in Jatki (language of the Jats) of Punjab-Sindh region. veṛhā octopus, said to be found in the Indus (Jaṭki lexicon of A. Jukes, 1900)

Rebus 1: L. veṛh, vehṛ m. fencing; Mth. beṛhī granary; L. veṛhā, vehṛā enclosure containing many houses; beṛā building with a courtyard (WPah.) (CDIAL 12130)

Rebus 2: Ta. vēḷ petty ruler, chief, Cāḷukya king, illustrious or great man, hero; ? title given by ancient Tamil kings to Vēḷāḷas; vēḷir a class of ancient chiefs in the Tamil country, the Cāḷukyas, petty chiefs; ? vēḷāḷaṉ a person of Vēḷāḷa caste. Kur. bēlas king, zemindar, god; belxā kingdom; belō, (Hahn) bēlō queen of white-ants. (DEDR 5545)

![]() Field Symbol 1 The orthography of the standard device clearly distinguishes two parts: Top register is a lathe with zigzag lines signifying churning motion and a pointed gimlet which drills into a bead. Bottom register is a portable furnace decorated with dotted circles. The nature of the furnace is reinforced by the orthography of smoke emanating from the portable furnace. Thus, the hypertext reads: 1. सांगड sāṅgaḍa m f (संघट्ट S) f A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together; 2. sangaḍ 'lathe/gimlet' rebus: sãgaṛh 'fortification' ; 3. kamaṭamu'portable furnace' rebus: kammaṭa'mint'; 4. dotted circle: dhāū, 'one in dice throw' rebus: 'red stone, mineral (iron ore)' PLUS vaṭṭa,vrtta'circle' Thus, together the expression is dhā̆vaḍ'smelter'. Thus, the hypertext of the composite standard device is: smelter's mint (in) fortification.

Field Symbol 1 The orthography of the standard device clearly distinguishes two parts: Top register is a lathe with zigzag lines signifying churning motion and a pointed gimlet which drills into a bead. Bottom register is a portable furnace decorated with dotted circles. The nature of the furnace is reinforced by the orthography of smoke emanating from the portable furnace. Thus, the hypertext reads: 1. सांगड sāṅgaḍa m f (संघट्ट S) f A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together; 2. sangaḍ 'lathe/gimlet' rebus: sãgaṛh 'fortification' ; 3. kamaṭamu'portable furnace' rebus: kammaṭa'mint'; 4. dotted circle: dhāū, 'one in dice throw' rebus: 'red stone, mineral (iron ore)' PLUS vaṭṭa,vrtta'circle' Thus, together the expression is dhā̆vaḍ'smelter'. Thus, the hypertext of the composite standard device is: smelter's mint (in) fortification.![]() Field Symbol 2

Field Symbol 2

![]() Field Symbol 3 The spoked wheelon the neck of the young bull is a hypertext. Ma. vēḷa throat. Koḍ. bo·ḷe neck. Go. (Tr.) warēṛ, (G.) veṛeṛ, vereṛ, vereḍi, (Mu.) vaṛer, (Ma.) veṛer̥ neck; (Y.) verer, (S.) veḍeṛu (pl. veḍahku), (L.) veḍāgāthroat; (W.) warer id., neck (DEDR 5547) Rebus: Ta. vēḷ petty ruler, chief, Cāḷukya king, illustrious or great man, hero; ? title given by ancient Tamil kings to Vēḷāḷas; vēḷir a class of ancient chiefs in the Tamil country, the Cāḷukyas, petty chiefs; ? vēḷāḷaṉ a person of Vēḷāḷa caste. Kur. bēlas king, zemindar, god; belxā kingdom; belō, (Hahn) bēlō queen of white-ants (DEDR 5545) PLUS arā'spokes of wheel' rebus: āra'brass'eraka'knave of wheel' rebus:eraka'moltencast copper' ; arka 'gold, copper'

Field Symbol 3 The spoked wheelon the neck of the young bull is a hypertext. Ma. vēḷa throat. Koḍ. bo·ḷe neck. Go. (Tr.) warēṛ, (G.) veṛeṛ, vereṛ, vereḍi, (Mu.) vaṛer, (Ma.) veṛer̥ neck; (Y.) verer, (S.) veḍeṛu (pl. veḍahku), (L.) veḍāgāthroat; (W.) warer id., neck (DEDR 5547) Rebus: Ta. vēḷ petty ruler, chief, Cāḷukya king, illustrious or great man, hero; ? title given by ancient Tamil kings to Vēḷāḷas; vēḷir a class of ancient chiefs in the Tamil country, the Cāḷukyas, petty chiefs; ? vēḷāḷaṉ a person of Vēḷāḷa caste. Kur. bēlas king, zemindar, god; belxā kingdom; belō, (Hahn) bēlō queen of white-ants (DEDR 5545) PLUS arā'spokes of wheel' rebus: āra'brass'eraka'knave of wheel' rebus:eraka'moltencast copper' ; arka 'gold, copper'

![]() Field Symbol 4 The device in front of the one-horned young bull signifies an artisan (goldsmith) guild: pattar 'trough' Ta. pātti bathing tub, watering trough or basin, spout, drain; pattal wooden bucket; pattar id., wooden trough for feeding animals. Ka. pāti basin for water round the foot of a tree. Tu. pāti trough or bathing tub, spout, drain. Te. pādi, pādu basin for water round the foot of a tree.(DEDR 4079) rebus: pattar, 'goldsmith guild' (Tamil) బత్తుడు battuḍu. n. A worshipper. భక్తుడు. The caste title of all the five castes of artificers as వడ్లబత్తుడు a carpenter. కడుపుబత్తుడు one who makes a god of his belly. L. xvi. 230. (Telugu) pattar paṭṭi 'goldsmith guild market, goldsmith guild hamlet'. See:

Field Symbol 4 The device in front of the one-horned young bull signifies an artisan (goldsmith) guild: pattar 'trough' Ta. pātti bathing tub, watering trough or basin, spout, drain; pattal wooden bucket; pattar id., wooden trough for feeding animals. Ka. pāti basin for water round the foot of a tree. Tu. pāti trough or bathing tub, spout, drain. Te. pādi, pādu basin for water round the foot of a tree.(DEDR 4079) rebus: pattar, 'goldsmith guild' (Tamil) బత్తుడు battuḍu. n. A worshipper. భక్తుడు. The caste title of all the five castes of artificers as వడ్లబత్తుడు a carpenter. కడుపుబత్తుడు one who makes a god of his belly. L. xvi. 230. (Telugu) pattar paṭṭi 'goldsmith guild market, goldsmith guild hamlet'. See:

![]() Field Symbol 5 kuṭhāru 'monkey' Rebus:kuṭhāru'armourer or weapon-maker'.

Field Symbol 5 kuṭhāru 'monkey' Rebus:kuṭhāru'armourer or weapon-maker'.

![]() Field Symbol 6 m1792a (Marshall, Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization (1931), Vol. 3., Plate CVI, # 93.) Size: ca. 1 in. square

Field Symbol 6 m1792a (Marshall, Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization (1931), Vol. 3., Plate CVI, # 93.) Size: ca. 1 in. squareField symbol: kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’; kundana ‘fine gold’ (Kannada). कुन्द [p= 291,2] one of कुबेर's nine treasures (N. of a गुह्यक Gal. ) L. کار کند kār-kund (corrup. of P کار کن) adj. Adroit, clever, experienced. 2. A director, a manager; (Fem.) کار کنده kār-kundaʿh. (Pashto) arka kundaṇa'goldsmith guild' PLUS koḍ 'horn' rebus koḍ 'workshop' See: The cartouched hieroglyph is the key hypertext expression.

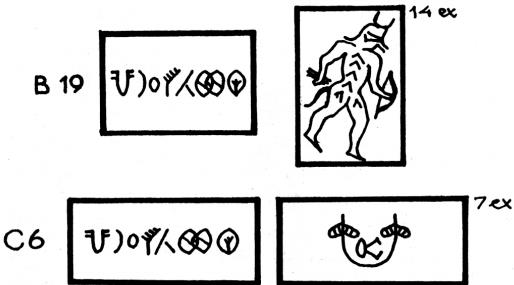

Meaning, artha of inscription: Trade (and metalwork wealth production) of kōnda sangara 'metalwork engraver'... PLUS (wealth categories cited.) This seal signifies vartaka bell-metal, brass metal castings smithy-forge merchant, mintmaster, helmsman.

Line 1:

dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’PLUS kolmo ‘rice plant’ rebus: kolilmi ‘smithy, forge’ PLUS kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe' कर्णिक 'steersman, helmsman'

Line 2:

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish-fin’ rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'.

Line 3:

Circumscipt dula ‘two’ rebus: dui ‘metal casting’ PLUS kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe' कर्णिक 'steersman, helmsman' PLUS vártikā f. ʻ quail ʼ (R̥gveda) vartaka ‘round stone’ rebus: vartaka ‘bell-metal, brass, merchant (pattar in Tamil)’ பத்தர்; pattar, n. perh. vartaka. Merchants; வியாபாரிகள். (W.)

Thus, helmsman, merchant in charge of bell-metal metal casting, mint and cargo.

vártikā f. ʻ quail ʼ RV. 2. vārtika -- m. lex. 3. var- takā -- f. lex. (eastern form ac. to Kātyāyana: S. Lévi JA 1912, 498), °ka -- m. Car., vārtāka -- m. lex. [Cf. vartīra -- m. Suśr., °tira -- lex., *vartakara -- ] 1. Ash. uwŕe/ ʻ partridge ʼ NTS ii 246 (connexion denied NTS v 340), Paš.snj. waṭīˊ; K. hāra -- wüṭü f. ʻ species of waterfowl ʼ (hāra -- < śāˊra -- ).

2. Kho. barti ʻ quail, partridge ʼ BelvalkarVol 88. 3. Pa. vaṭṭakā -- f., °ka -- in cmpds. ʻ quail ʼ, Pk. vaṭṭaya -- m., N. baṭṭāi (< vārtāka -- ?), A. batā -- sarāi, B. batui, baṭuyā; Si. vaṭuvā ʻ snipe, sandpiper ʼ (ext. of *vaṭu < vartakā -- ). -- With unexpl. bh -- : Or. bhāṭoi, °ṭui ʻ the grey quail Cotarnix communis ʼ, (dial.) bhāroi, °rui (< early MIA. *vāṭāka -- < vārtāka -- : cf. vāṭī -- f. ʻ a kind of bird ʼ Car.). Addenda: vartikā -- [Dial. a ~ ā < IE. non -- apophonic o (cf. Gk. o)/rtuc and early EMIA. vāṭī -- f. ʻ a kind of bird ʼ Car. < *vārtī -- )(CDIAL 11351) Rebus:vartalōha n. ʻ a kind of brass (i.e. *cup metal?) ʼ lex. [*varta -- 2 associated with lōhá -- by pop. etym.?]

Pa. vaṭṭalōha -- n. ʻ a partic. kind of metal ʼ; L.awāṇ. valṭōā ʻ metal pitcher ʼ, P. valṭoh, ba° f., vaṭlohā, ba° m.; N. baṭlohi ʻ round metal vessel ʼ; A. baṭlahi ʻ water vessel ʼ; B. bāṭlahi, bāṭulāi ʻ round brass cooking vessel ʼ; Bi. baṭlohī ʻ small metal vessel ʼ; H. baṭlohī, °loī f. ʻ brass drinking and cooking vessel ʼ, G. vaṭloi f.

Addenda: vartalōha -- : WPah.kṭg. bəlṭóɔ m. ʻ large brass vessel ʼ.CDIAl 11357)

*varta2 ʻ circular object ʼ or more prob. ʻ something made of metal ʼ, cf. vartaka -- 2 n. ʻ bell -- metal, brass ʼ lex. and vartalōha -- . [√vr̥t?] Pk. vaṭṭa -- m.n., °aya -- m. ʻ cup ʼ; Ash. waṭāˊk ʻ cup, plate ʼ; K. waṭukh, dat. °ṭakas m. ʻ cup, bowl ʼ; S. vaṭo m. ʻ metal drinking cup ʼ; N. bāṭā, ʻ round copper or brass vessel ʼ; A. bāṭi ʻ cup ʼ; B. bāṭā ʻ box for betel ʼ; Or. baṭā ʻ metal pot for betel ʼ, bāṭi ʻ cup, saucer ʼ; Mth. baṭṭā ʻ large metal cup ʼ, bāṭī ʻ small do. ʼ, H. baṭṛī f.; G. M. vāṭī f. ʻ vessel ʼ. *aṅkavarta -- , *kajjalavarta -- , *kalaśavarta -- , *kṣāṇavartaka -- , *cūrṇavarta -- , parṇavartikā -- , *hiṅgulavarta -- .

Addenda: *varta -- 2: Md. vař ʻ circle ʼ (vař -- han̆du ʻ full moon ʼ).(CDIAL 11347)

*varta3 ʻ round stone ʼ. 2. *vārta -- . [Cf. Kurd. bard ʻ stone ʼ. -- √vr̥t1]

1. Gy. eur. bar, SEeur. bai̦ ʻ stone ʼ, pal. wăṭ, wŭṭ ʻ stone, cliff ʼ; Ḍ. boṭ m. ʻ stone ʼ, Ash. Wg. wāṭ, Kt. woṭ, Dm. bɔ̈̄'ṭ, Tir. baṭ, Niṅg. bōt, Woṭ. baṭ m., Gmb. wāṭ; Gaw. wāṭ ʻ stone, millstone ʼ; Kal.rumb. bat ʻ stone ʼ (bad -- váṣ ʻ hail ʼ), Kho. bort, Bshk. baṭ, Tor. bāṭ, Mai. (Barth) "bhāt" NTS xviii 125, Sv. bāṭ, Phal. bā̆ṭ; Sh.gil. băṭ m. ʻ stone ʼ, koh. băṭṭ m., jij. baṭ, pales. baṭ ʻ millstone ʼ; K. waṭh, dat. °ṭas m. ʻ round stone ʼ, vüṭü f. ʻ small do. ʼ; L. vaṭṭā m. ʻ stone ʼ, khet. vaṭ ʻ rock ʼ; P. baṭṭ m. ʻ a partic. weight ʼ, vaṭṭā, ba° m. ʻ stone ʼ, vaṭṭī f. ʻ pebble ʼ; WPah.bhal. baṭṭ m. ʻ small round stone ʼ; Or. bāṭi ʻ stone ʼ; Bi. baṭṭāʻ stone roller for spices, grindstone ʼ. -- With unexpl. -- ṭṭh -- : Sh.gur. baṭṭh m. ʻ stone ʼ, gil. baṭhāˊ m. ʻ avalanche of stones ʼ, baṭhúi f. ʻ pebble ʼ (suggesting also an orig. *vartuka -- which Morgenstierne sees in Kho. place -- name bortuili, cf. *vartu -- , vartula -- ).2. Paš.lauṛ. wāṛ, kuṛ. wō ʻ stone ʼ, Shum. wāṛ.vartaka -- 1; *vartadruṇa -- , *vartapānīya -- ; *aṅgāravarta -- , *arkavarta -- , *kaṣavartikā -- .vartaka1 m. ʻ *something round ʼ (ʻ horse's hoof ʼ lex.), vaṭṭaka -- m. ʻ pill, bolus ʼ Bhadrab. [Cf. Orm. waṭk ʻ walnut ʼ (wrongly ← IA. *akhōṭa -- s.v. akṣōṭa -- ). <-> √vr̥t1]

Wg. wāṭi( -- štūm) ʻ walnut( -- tree) ʼ NTS vii 315; K. woṭu m., vüṭü f. ʻ globulated mass ʼ; L. vaṭṭā m. ʻ clod, lobe of ear ʼ; P. vaṭṭī f. ʻ pill ʼ; WPah.bhal. baṭṭi f. ʻ egg ʼ.

vartaka -- 2 n. ʻ bell -- metal, brass ʼ lex. -- See *varta -- 2, vártalōha -- .(CDIAL 11348, 11349)

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish-fin’ rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'.

![]() Field Symbol 7 The plant in front of the one-horned young bull: kolmo'rice plant' rebus; kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

Field Symbol 7 The plant in front of the one-horned young bull: kolmo'rice plant' rebus; kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

![]() Field Symbol 8 The two horns of the aurochs (Indian bos aurochs) is a determinative that the young bull is NOT a unicorn but a bovine of the bos genus.

Field Symbol 8 The two horns of the aurochs (Indian bos aurochs) is a determinative that the young bull is NOT a unicorn but a bovine of the bos genus.

![]() Field Symbol 9 The two horns of the aurochs (Indian bos aurochs) is a determinative that the young bull is NOT a unicorn but a bovine of the bos genus.

Field Symbol 9 The two horns of the aurochs (Indian bos aurochs) is a determinative that the young bull is NOT a unicorn but a bovine of the bos genus.

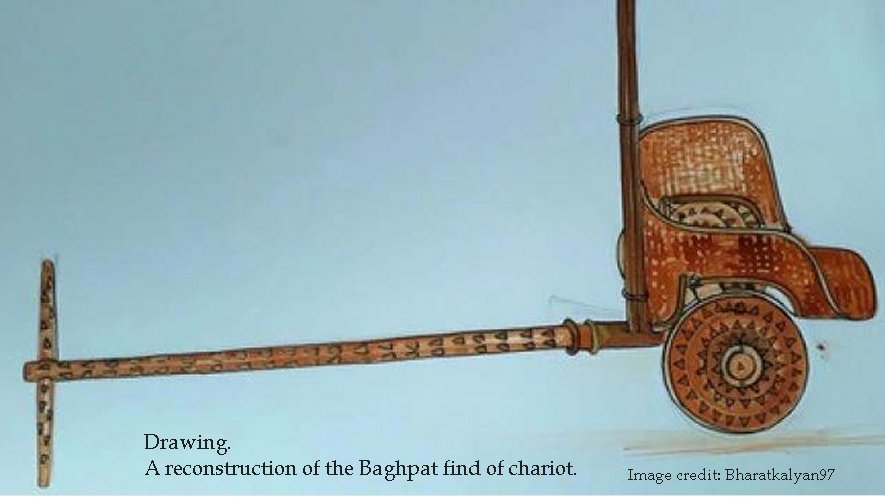

The post holding the young bull banner is signified by a culm of plant, esp. of millet. This is karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron' ajirda karba 'very hard iron' (Tulu)

L’enseigne (M,458) (pl. LVII) est faite d’un petit taureau dresse, passant a gauche, monte sur un socle supporte par l’anneau double du type passe-guides. La hamper est ornementee d’une ligne chevronnee et on retrouve le meme theme en travers de l’anneau double.M.458 H. 0.070 m. (totale); h. 0, 026 m. (taureau sur socle); l. 0,018m.

Translation

The sign (M, 458) (pl. LVII) is made of a young bull stand, from left, mounted on a base supports the double ring-pass type guides. The hamper is decorated with a line and the same theme is found across the double ring.

M.458 H. 0.070 m. (Total); h. 0, 026 m. (Bull on base); l. 0,018m.

Frise d'un panneau de mosaïque

Vers 2500 - 2400 avant J.-C.

Mari, temple d'Ishtar

Coquille, schiste

Fouilles Parrot, 1934 - 1936

AO 19820 Louvre reference

![]()

![]()

![Inline image 3]() Mari procession with one-horned young bull atop a culm of millet as the flagstaff. Detail of a victory parade. Schist panel inlaid with mother-of-pearl plaques. Louvre Museum. Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820

Mari procession with one-horned young bull atop a culm of millet as the flagstaff. Detail of a victory parade. Schist panel inlaid with mother-of-pearl plaques. Louvre Museum. Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820

In front of a soldier, a Sumerian standard bearer holds a banner aloft signifying the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Harappa Script (Indus writing). Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. 2400 BCE Schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques. Louvre Museum.

As a proclamation of a metallurgical achievement, this composition of a culm of millet upholding kōnda ‘engraver', kōndaṇa, 'lapidary infixing gems' is a signifier of the competence to create a ferrite alloy with kundaṇa 'pure gold'. The idea of a ferrite metal alloy or cementite (with perhaps gold) is explained by the Mari proclamation procession carrying a one-horned young bull atop a culm-of-millet flagstaff, as a process of hardening metal alloy: "Mild steel (carbon steel with up to about 0.2 wt% C) consist mostly of ferrite and increasing amounts of cementite (iron carbide) in a laminar structure called pearlite. Since bainite and pearlite each have ferrite as a component, any iron-carbon alloy will contain some amount of ferrite if it is allowed to reach equilibrium at room temperature. The exact amount of ferrite will depend on the cooling process the iron-carbon alloy undergoes as it cools."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrite_(iron)

The arrival of the 'unicorn' motif is heralded in a Frise d'un panneau de mosaïque Vers 2500 - 2400 avant J.-C. Mari, temple d'Ishtar. The priest who proclaims the flagstaff carrying 'unicorn' is comparable to the Mohenjo-daro priest who has been deciphered as Potr̥ पोतृ,'purifier' priest of dhā̆vaḍ 'iron-smelters'. ![]()

![Image result for mari mesopotamia]()

Location of Mari.

![]() This shell plaque was found in the palace of Mari. It is dated circa 2500 B.C.E. Sumerian soldier carrying weapons, implements (armour, battle-axe, helmet).

This shell plaque was found in the palace of Mari. It is dated circa 2500 B.C.E. Sumerian soldier carrying weapons, implements (armour, battle-axe, helmet).Rein-rings link the culm of millet to the stand on which one-horned young bull is held: saṅghara 'chain link' rebus: jangaḍiyo ‘military guard', This unique metaphor of a Sumerian standard bearer using culm of millet as the flagpost is a Harappa Script hieroglyph. A number of hieroglyph-rebus possibilities to explain this pictorial narrative. It is suggested that the best fit for rebus reading is: karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

Pearl millet in the field.

![Groene naaldaar aarpluim (Setaria viridis).jpg]() Setaria viridis inflorescence.Setaria viridis is a species of grass known by many common names, including green foxtail green bristlegrass,and wild foxtail millet.Foxtail Millet was cultivated in China by 2700 B.C. and during the Stone Age in Europe.

Setaria viridis inflorescence.Setaria viridis is a species of grass known by many common names, including green foxtail green bristlegrass,and wild foxtail millet.Foxtail Millet was cultivated in China by 2700 B.C. and during the Stone Age in Europe.

Ka. ārike the Indian millet, Panicum italicum; hāraka, hāraku Paspalum scrobiculatum Lin. Te. āruka, āruga, (B. also) ārike, āriga P. scrobiculatum (B. P. frumentaceum); āḷḷu (pl.) P. scrobiculatum. Go. (Mu. Elwin) ārk Setaria italica (Voc. 137). Pe. ārku (pl.) a species of millet. Kui ārka id. Kuwi (Su.) ārgu (pl. ārka) Panicum italicum.(DEDR 379) *aṇuni ʻ millet ʼ. [Cf. áṇu -- 1 NTS xii 156] NiDoc. aḍ́iṁni prob. ʻ millet ʼ H. W. Bailey BSOAS xii 332; Ḍ. árīn ʻ millet ʼ, Kt. awŕī˜, Dm. äŕín, Paš. aṛīˊn, Gaw. éṛin, Kal. aṛín, Kho. oḷīn; -- all < *aḍin -- with same dissimilation of ṇ -- n as in ajñānin -- rather than < *arjana -- -- More doubtful is Sh. (Lorimer) āno ʻ Indian millet ʼ.(CDIAL 145) Rebus: arka 'gold, copper' (Hence, a semantic determinant of the young bull: arka kundaṇa 'goldsmith guild' PLUS koḍ 'horn' rebus koḍ 'workshop' See:

Rebus: అగసాలి (p. 23) agasāli or అగసాలెవాడు agasāli. [Tel.] n. A goldsmith. కంసాలివాడు.

The procession is a proclamation and a celebration of new technological competence gained by the 'turner' artisans of the civilization.

The 'turner' (one who uses a lathe for turning) in copper/bronze/brass smithy/forge has gained the competence to work with karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

![]()

Hieroglyph on an Elamite cylinder seal (See illustration embedded)

Hieroglyph: stalk, thorny

Seal published: The Elamite Cylinder seal corpus: c. 3500-1000 BCE. karba 'millet culm' rebus: karba'iron'. krammara 'look back' rebus: kamar 'artisan' karaDa 'aquatic bird' rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' mlekh 'goat' (Br.); mr̤eka (Te.); mēṭam 'ram, antelope' rebus: milakkhu 'copper' (Pali) mlecchamukha 'copper' (Samskrtam)

Tubular stalk: karb (Punjabi) kaḍambá, kalamba -- 1, m. ʻ end, point, stalk of a pot- herb ʼ lex. [See kadambá -- ] B. kaṛamba ʻ stalk of greens ʼ; Or. kaṛambā, °mā stalks and plants among stubble of a reaped field ʼ; H. kaṛbī, karbī f. ʻ tubular stalk or culm of a plant, esp. of millet ʼ (→ P. karb m.); M. kaḍbā m. ʻ the culm of millet ʼ. -- Or. kaḷama ʻ a kind of firm -- stemmed reed from which pens are made ʼ infl. by H. kalam ʻ pen ʼ ← Ar.?(CDIAL 2653) See: Ta. kāmpu flower-stalk, flowering branch, handle, shaft, haft. Ma. kāmpu stem, stalk, stick of umbrella. Ko. ka·v handle. To. ko·f hollow stem, handle of tool. Ka. kāmu, kāvu stalk, culm, stem, handle. Te. kāma stem, stalk, stick, handle (of axe, hoe, umbrella, etc.), shaft. Ga. (S.3) kāŋ butt of axe. Go. (Tr.) kāmē stalk of a spoon; (Mu.) kāme handle of ladle (Voc. 640)(DEDR1454). Ka. kAvu is cognate with karb 'culm of millet' and kharva 'nidhi'.

Hieroglyph 1: H. kaṛbī, karbī f. ʻ tubular stalk or culm of a plant, esp. of millet ʼ (→ P. karb m.); M. kaḍbā m. ʻ the culm of millet ʼ. (CDIAL 2653) Mar. karvā a bit of sugarcane.(DEDR 1288) Culm, in botanical context, originally referred to a stem of any type of plant. It is derived from the Latin word for 'stalk' (culmus) and now specifically refers to the above-ground or aerial stems of grasses and sedges. Proso millet, common millet, broomtail millet, hog millet, white millet, broomcorn millet Panicum miliaceum L. [Poaceae]Leptoloma miliacea (L.) Smyth; Milium esculentum Moench; Milium paniceum Mill.; Panicum asperrimum Fischer ex Jacq.;Panicum densepilosum Steud.; Panicum miliaceum Blanco, nom. illeg., non Panicum miliaceum L.; Panicum miliaceumWalter, nom. illeg., non Panicum miliaceum L.; Panicum miliaceum var. miliaceum; Panicum milium Pers. (Quattrocchi, 2006) Proso millet is an erect annual grass up to 1.2-1.5 m tall, usually free-tillering and tufted, with a rather shallow root system. Its stems are cylindrical, simple or sparingly branched, with simple alternate and hairy leaves. The inflorescence is a slender panicle with solitary spikelets. The fruit is a small caryopsis (grain), broadly ovoid, up to 3×2 mm, smooth, variously coloured but often white, shedding easily (Kaume, 2006).Panicum miliaceum has been cultivated in eastern and central Asia for more than 5000 years. It later spread into Europe and has been found in agricultural settlements dating back about 3000 years. http://www.feedipedia.org/node/722 Ta. varaku common millet, Paspalum scrobiculatum; poor man's millet, P. crusgalli. Ma. varaku P. frumentaceum; a grass Panicum. Ka. baraga, baragu P. frumentaceum; Indian millet; a kind of hill grass of which writing pens are made. Te. varaga, (Inscr.) varuvu Panicum miliaceum. / Cf. Mar. barag millet, P. miliaceum; Skt. varuka- a kind of inferior grain. [Paspalum scrobiculatum Linn. = P. frumentaceum Rottb. P. crusgalli is not identified in Hooker.] (DEDR 5260)

Rebus 1:

![]() Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron; Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native metal (DEDR 192) Tu. kari soot, charcoal; kariya black; karṅka state of being burnt or singed; karṅkāḍuni to burn (tr.); karñcuni to be burned to cinders;karñcāvuni to cause to burn to cinders; kardů black; karba iron; karvāvuni to burn the down of a fowl by holding it over the fire (DEDR 1278). खर्व (-र्ब) a. [खर्व्-अच्] N. of one of the treasures of Kubera (Samskritam)

Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron; Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native metal (DEDR 192) Tu. kari soot, charcoal; kariya black; karṅka state of being burnt or singed; karṅkāḍuni to burn (tr.); karñcuni to be burned to cinders;karñcāvuni to cause to burn to cinders; kardů black; karba iron; karvāvuni to burn the down of a fowl by holding it over the fire (DEDR 1278). खर्व (-र्ब) a. [खर्व्-अच्] N. of one of the treasures of Kubera (Samskritam) ![]()

The replica Ishtar Gate in Babylon, Iraq in 2011

![]() Model of the main procession street (Aj-ibur-shapu) towards Ishtar Gate

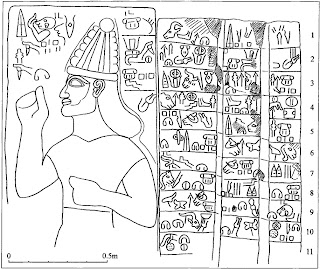

Model of the main procession street (Aj-ibur-shapu) towards Ishtar GateThe cuneiform inscription of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

Inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II

Inscription:The inscription of the Ishtar Gate is written in Akkadian cuneiform in white-glazed and blue glazed bricks, and was a dedication by Nebuchadnezzar to explain the gate’s purpose. On the wall of the Ishtar Gate the inscription is 15 meters tall by 10 meters wide and includes 60 lines of writing. The inscription was created around the same time as the gates construction, around 605-562 BCE.[6][citation needed]Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, the pious prince appointed by the will of Marduk, the highest priestly prince, beloved of Nabu, of prudent deliberation, who has learnt to embrace wisdom, who fathomed Their (Marduk and Nabu) godly being and pays reverence to their Majesty, the untiring Governor, who always has at heart the care of the cult of Esagila and Ezida and is constantly concerned with the well being of Babylon and Borsippa, the wise, the humble, the caretaker of Esagila and Ezida, the first born son of Nabopolassar, the King of Babylon, am I.

Both gate entrances of the (city walls) Imgur-Ellil and Nemetti-Ellil following the filling of the street from Babylon had become increasingly lower. (Therefore,) I pulled down these gates and laid their foundations at the water table with asphalt and bricks and had them made of bricks with blue stone on which wonderful bulls and dragons were depicted. I covered their roofs by laying majestic cedars lengthwise over them. I fixed doors of cedar wood adorned with bronze at all the gate openings. I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor so that Mankind might gaze on them in wonder.

I let the temple of Esiskursiskur, the highest festival house of Marduk, the lord of the gods, a place of joy and jubilation for the major and minor deities, be built firm like a mountain in the precinct of Babylon of asphalt and fired bricks.(Marzahn, Joachim (1981). Babylon und das Neujahrsfest. Berlin: Berlin : Vorderasiatisches Museum. pp. 29–30.)

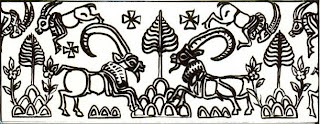

The reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. "The gate was constructed using glazed brick with alternating rows of bas-relief mušḫuššu (dragons), aurochs (bulls), and lions, symbolizing the gods Marduk, Adad, and Ishtar respectively." (Kleiner, Fred (2005). Gardner's Art Through the Ages. Belmont, CA: Thompson Learning, Inc. p. 49.)

Marduk and his dragon Mušḫuššu, from a Babylonian cylinder seal (Willis, Roy (2012). World Mythology. New York: Metro Books. p. 62. ) ![phantasmagoricaldreams: Detail of a Mushussu, symbol of the god Marduk, from the Ishtar gate. Babylon (575 BC)]()