सोमःसंस्था reported by Valmiki as बहुसुवर्णक, bahusuvarṇaka is the economic institutional framework which explains the principal wealth-creation activities of brahma-somāraṇyadocumented by Kautilya in 4th cent. BCE.

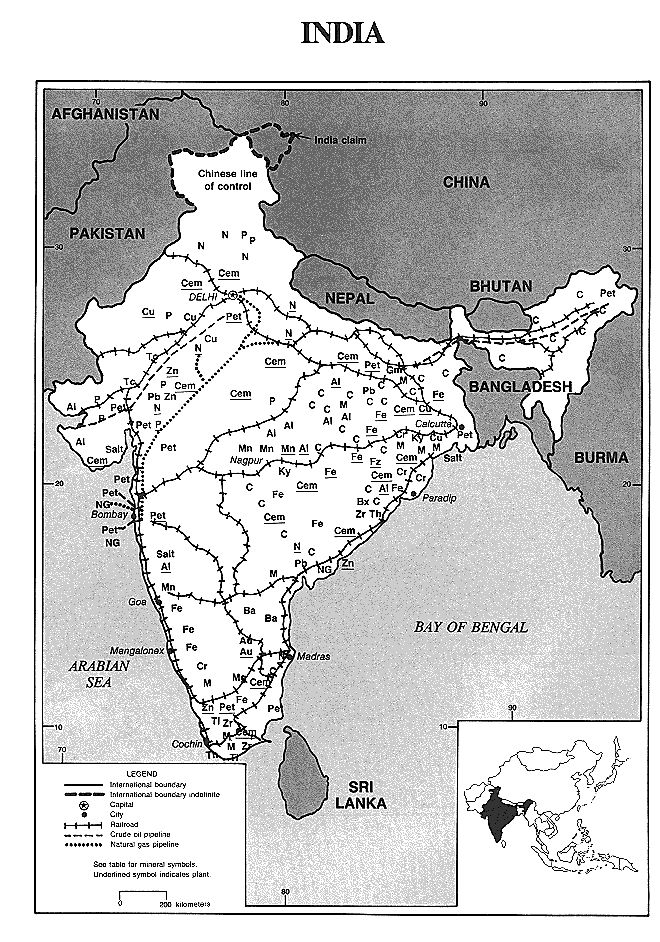

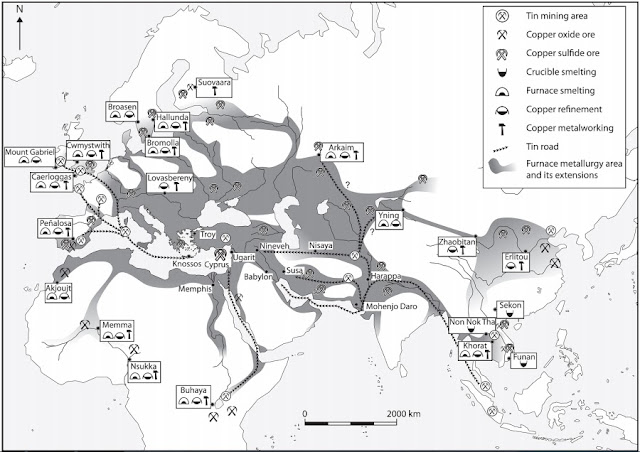

Cultural Itihāsa of Bhārata is narrated in exquisite detail and splendour on data archives of ancient sculptural and writing system traditions, starting from the days of Veda and Harappa Script. These data archives provide information on the wealth of rāṣṭram of Vedic times, ca. 8th millennium BCE which resulted in the status of Bharata as the richest nation on the globe accounting for 33.9% of Global Gross Domestic Product in 1 CE. Bronze Age Revolution alone of arts, crafts, technological excellence and work ethos of the people organized in corporate form of श्रेणि ‘guild’, explains the wealth of the nation (which according to Angus Maddison was close to 33.9% of world GDP in 1 CE).

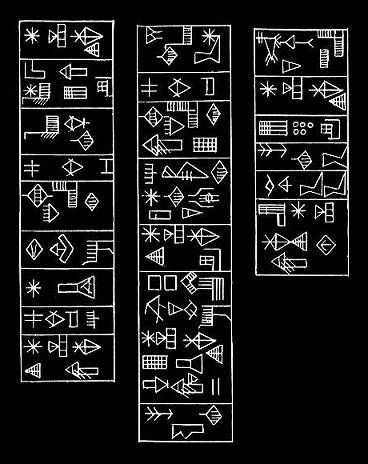

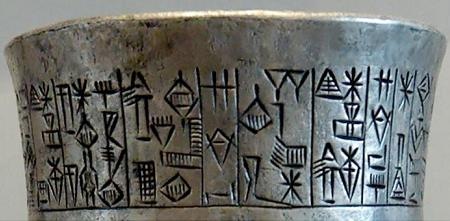

The full history of the processes leading to the creating the wealth of Bharatam has to be told. A first step has been taken, deciphering the 7000+ inscriptions of the civilization dated from ca. 4th millennium BCE [the early writing system is established by the discovery of a potsherd with Harappa script discovered by Harvard HARP archaeology team (signifying tin smithy) is dated to ca. 3300 BCE].

A synonym for pyrites is: madhu dhātu. A knowledge system of metallurgical processes or madhu-vidyā or pravargya vidyā related to such ores are narrated in the Veda.

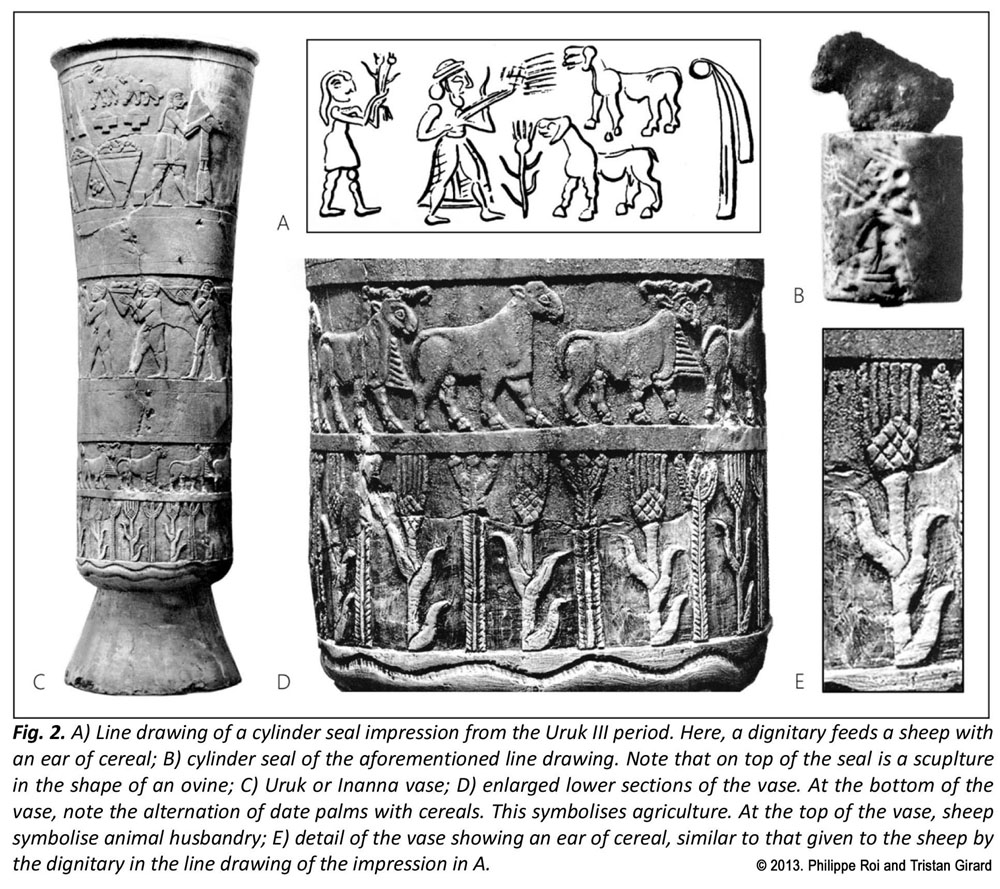

Data archives documenting these processes are found in Harappa Script hypertexts and in Yajñavarāha metaphors in Veda texts and sacred Yajñavarāha sculptures with iconographic details as hypertexts.

The discovery of yajñakundas in many sites and the stellar evidence of Binjor yajñakunda with octagonal pillar and Seal with Harappa Script attesting to metalwork of the Bronze Age affirm the civilization as a continuum of Vedic cultura, Soma SamsthA. It is thus apposite to designate the civilization as Vedic Sarasvati Civilization with roots traceable to ca. 8th millennium (evidenced by the Bhirrana archaeological site with carbon-14 dates confirmed between ca. 7570 BCE to 6200 BCE).

Executive summary of सोमःसंस्था, brahma-somāraṇya (reported by Kautilya, 4th cent. BCE)

Work and striving result in creation of wealth from earth’s resources and endowed faculties of the अर्थिन् a. one who longs for or strives to get wealth or gain any object. अर्थार्थी जीवलोको$यम् । आर्तो जिज्ञासुरर्थार्थी Bg.7.16. यजस् n. Ved. Worship; इन्द्राग्नी यजसा गिरा Rv. 8.4.4. Hence, yajña is performance of worship. The governing principle, dharma is: work is worship, which is a prayer to the paramaatman who has endowed the people with competence to relate to environmental phenomena and earth’s resources.

The ancient people of Bharata who participated in the processes of creation of wealth from Vedic times and during the Bronze Age Tin Bronze Revolution have left for us the legacy of yajña and a writing system called mlecchita vikalpa, ‘Meluhha cipher.’

These resources constitute a framework of ‘wealth’ as posited in the following sections in a pilgrim’s journey from Being to Becoming:

- Ancient Veda tradition, cultural, economic history सोमःसंस्था, brahma-somāraṇya, yūpa, yajñasya ketu

- Archaeological evidence of Binjor अष्टाश्रि यूप in yajñakuṇḍa, 2500 BCE

- Metonymy — hypertexts in Harappa Script of Bronze Age

- Metonymy –Vedic Yajñavarāha metaphors in Veda texts, in sculptures/hypertexts of Veda/Harappa Script tradition

Section 1. ancient Veda tradition, cultural, economic history सोमःसंस्था, brahma-somāraṇya, yūpa, yajñasya ketu

As Narahari Achar has demonstrated, सोमःसंस्था to process soma, is the central yajña in all four Veda-s and that the 191 suktas of Mandala 1 and 10 of Rgveda lay out the plan for the performance of Somayajña. (BN Narahari Achar, Somayajña and the structure of Rgveda, 2016).

sōmḥ सोमःसंस्था a form of the Soma-yAga; (these are seven अग्निष्टोम, अत्यग्निष्टोम, उक्थ, षोढशी, अतिरात्र, आप्तोर्याम and वाजपेय). agniSToma, atyagniSToma, ukthya, Soḍaśin, atirātra, aptoryāma and vājapeya. संस्था ‘occupation, business , profession.‘

Manasataramgini has shown that all the mandala-s of Rigveda are tightly networked and integrated with the central सोमःसंस्था and hence, the somayajña tradition described in the Rigveda is a definitive sacred text which dates to the time when Vedavyasa compiled the Samhita. It will thus be erroneous to interpret the Samhita text as a layered document, over an extended period of time. The dates of Rishis who are mantra-drashTa-s of specific sukta-s (sets of Rca-s) can be reckoned by astronomical evidences recorded in ancient texts.

There are three groups of yajña s, depending on the type of offering made to fire in the sacred prayer:

- haviryajña (b) pākayajña and (c) somayajña. Each of these in turn consists of seven subgroups of

yajñas

The haviryajña group offering consists of “havis”, such as milk, clarified butter, food- grains, etc.

Pākayajña material offerings include cooked food-grains.

somayajña s in which the offering is the juice of the crushed soma plant made to the deity soma, are

further divided into

(i) aikāha those that are completed in one single day

(ii) ahīna, those that require from two to twelve days for completion

(iii) satra, those that require more than twelve days.

The somayāga ceremony is the holiest ritual, which symbolically transforms the earthly yajamāna into a celestial one.

All these are already well known in the Rgveda samhita, for example, RV (I. 20. 7) refers to the

Twenty-one yajñas.

“teno ratnāni dhattana trirāsāptāni sunvate | ekamekam suśastibhih||” RV (I.20.7)

“Confer therefore, (Ribhus), moved by our praises, the three-fold riches one by one upon our

yajamāna, who performs the thrice seven-fold sacrifices.”

Yajña in the simplest terms involves the tyāga (the giving up) of some dravya (material possession)

of the yajamāna (the sacrificer) to the devata(deity) through the medium of agni (fire) to the

accompaniment of recitation of mantra s.

Yajña is a journey (adhvaram). At the cosmic level, creation itself is an yajña. yajnena yajña mayajanta deva-s RV(I.164.50; X.90.16) Soma was brought to earth so humans can ascend to heaven with its help.

yajno vai sutarmA nauh |(AB I.19) “yajña is verily the ship of good passage.”

somam rājānam krUNantyauSadho vai somo r ājauSadhibhistam bhiSajyanti somameva rājānam

krUyamāNamānu yāni kāni ca bheSajāni tāni sarvāNyagniSToma mapiyanti ||

“They buy the King Soma. The King Soma belongs to the herbs. They cure a sick person by means of

medicaments taken from the vegetable kingdom. All the vegetable medicaments follow the King Soma as he is being bought. They are thus comprised in the AgniSToma.”

The origin of somayajña: the hawk brought soma

As is well known by the legend, soma was originally in heaven, and was brought to earth by the chandas gāyatri. This legend is known in Rgveda :

Rjipi s’yeno dadamāno ams’um parāvatah s’akuno mandram madam |

Somam bharaddād RhANo devāvan divo amuSmād uttaratādāya || (RV IV. 26. 6)

“The straight flying hawk, conveying the plant from afar; the bird resolute with purpose brought the exhilarating soma attended by the gods, having taken it from the lofty heaven.”

ādāya s’yeno ābharat somam sahasram savān ayutanca sākam |

atrā purandhirajah āda r rātirmade somasya mUrā amUrah || (RV IV.26.7)

“The hawk, having taken the Soma brought it for the performance of thousands and tens of thousands of yajñas. Here the unbewildered (steady minded) performer of many deeds (Indra) destroyed the bewildered enemies with the help of soma.” (BN Narahari Achar, Somayajña and the structure of Rgveda)

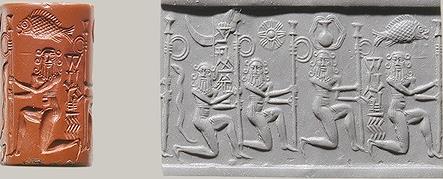

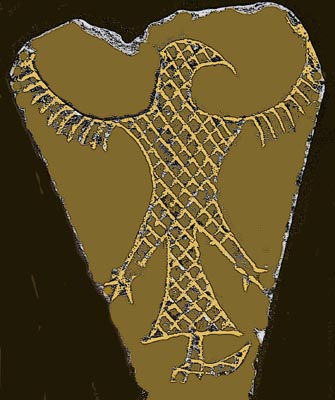

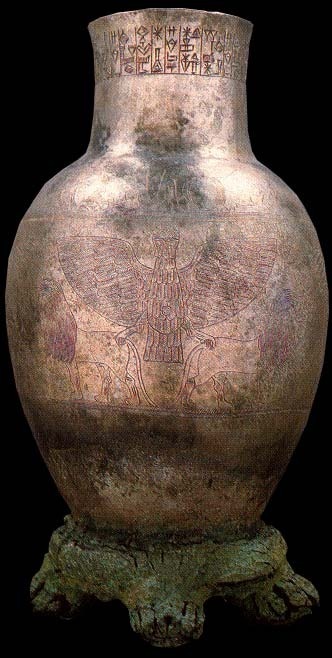

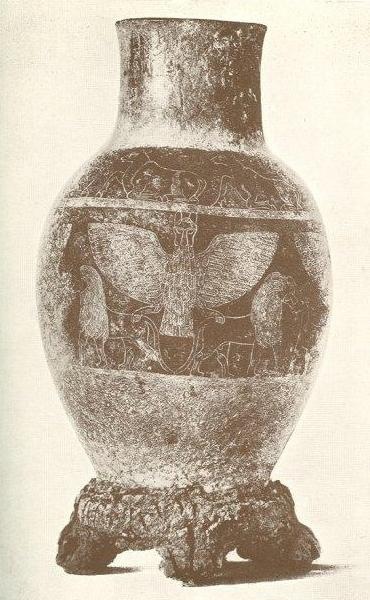

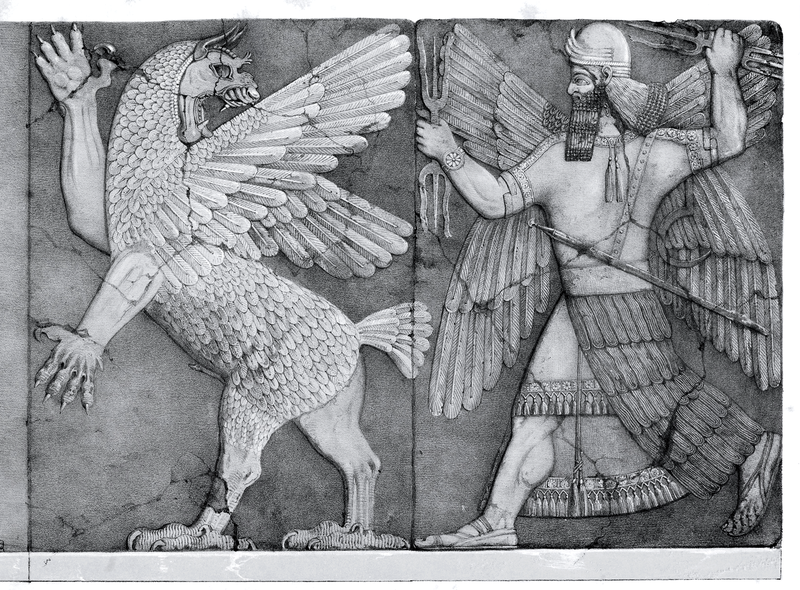

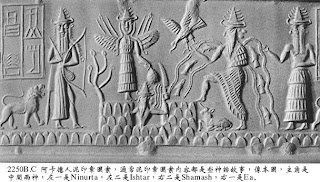

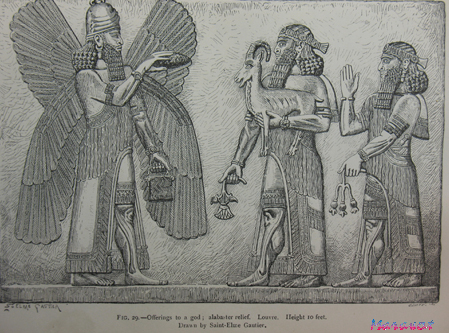

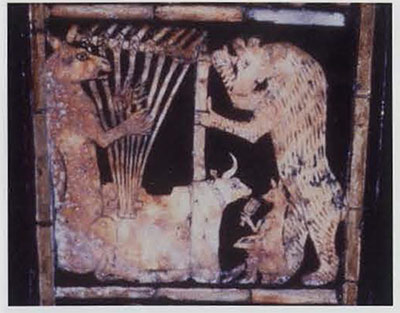

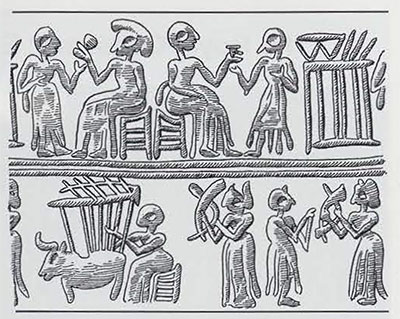

The references to Anzu in ancient Mesopotamian tradition parallels the legends of śyena ‘falcon’ which is used in Vedic tradition of Soma yajña attested archaeologically in Uttarakhand with a śyenaciti, ‘falcon-shaped’ fire-altar.

śyena, orthography, Sasanian iconography. Continued use of Indus Script hieroglyphs

Comparing the allegory of soma and the legend of Anzu, the bird which stole the tablets of destiny, I posit a hypothesis that the tablets of destiny are paralleled by the Indus writing corpora which constitute a veritable catalog of stone-, mineral- and metal-ware in the bronze age evolving from the chalcolithic phase of what constituted an ‘industrial’ revolution of ancient times creating ingots of metal alloys and weapons and tools using metal alloys which transformed the relation of communities with nature and resulted in the life-activities of lapidaries transforming into miners, smiths and traders of metal artefacts.

I suggest that ayas of bronze age created a revolutionary transformation in the lives of people of these bronze age times.

Maybe, Tocharian ancu had the same meaning as Rigvedic gloss, amśu rendered in the sculptural metaphors of Anzu. If so, ancu might have denoted electrum, ‘gold-silver compound’ which was subjected to reduction, by oxidation of impurities, by incessant firing for five days and nights to create the shining wealth of gold. The old Egyptian gloss for electrum was assem, cognate soma, an insight provided by the savant Joseph Needham in his magnum opus.

Soma is associated with the mountains (adri) ‘growing’ on the mountains (giriṣṭhhām) RV. III.48,2; V.43.4; IX.18.1, 62,4.

RV 3.48.2 On the day on which you (Indra) were born, you did drink at will the mountain-abiding nectar of this Soma, for your youthful parent mother (Aditi), in the dwelling of your great sire (Kaśyapa), gave it to you before she gave the breast.

RV 5.43.4 The ten express of the juice, (the fingers), and the two arms of the priests, which are the dexterous immolators of the Soma, take hold of the stone; the exulting, skilful-fingered (priest) milks the mountain-born juice of the sweet Soma, and that Soma (yields its) pure juice. [The text has only śukram amśuh = sa ca amśuh śukram nirmalam rasam dugdhe, and that Soma has milked the pure juice; or amśu may be an epithet of adhvaryu, the extensively present priest, amśur vya_pto adhvaryuh].

RV 9.62.4 The mountain-born Soma flows for exhilaration, mighty in the (vasati_vari_) waters; he alights like a falcon on his own place. [amśu may also be interpreted as metal-streaks in an ore block.)

RV 9.18.1 Effused while pressed between the stones, the Soma flows upon the straining cloth; you are the giver of all things to those who praise you.

Soma is described as parvatāvr.dhah in a rica, that the pyrites are from the mountain slopes:

RV 9.46.1 Begotten by the stones the flowing (Soma-juices) are effused for the banquet of the gods’ active horses. [Begotten by the stones: or, growing on the mountain slopes].

Soma is ‘a god pressed for the gods’ (RV 9,3.6-7).

Gerd Carling, Georges-Jean Pinault, Werner Winter, 2008, Dictionary and thesaurus of Tocharian A, Volume 1, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. Georges-Jean Pinault, 2006, Further links between the Indo-Iranian substratum and the BMAC language in: Bertil Tikkanen & Heinrich Hettrich, eds., 2006, Themes and tasks in old and middle Indo-Aryan linguistics, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 167 to 196. “…we have Toch. A. *ancu ‘iron’, the basis of the derived adjective ancwaashi ‘made of iron’, to which corresponds Toch. B encuwo, with the parallel derived adjective encuwanne ‘made of iron’…The two forms go back to CToch. oencuwoen- non.sg. *oencuwo, the final part of which is a regular product of IE *-on…This noun is deprived of any convincing IE etymology…The term Ved. amśu-, Av . asu- goes back to a noun borrowed from some donor language of Central Asia, as confirmed by CToch. *oencuwoen-…the BMAC language would not belong to the Indo-European family; it does not seem to be related to Dravidian either…New identifications and reconstructions will certainly help to define more precisely the contours of the BMAC vocabulary in Indo-Iranian, as well as in Tocharian.” (Georges-Jean Pinault, 2006, Further links between the Indo-Iranian substratum and the BMAC language in: Bertil Tikkanen & Heinrich Hettrich, eds., 2006, Themes and tasks in old and middle Indo-Aryan linguistics, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 167 to 196.) “…The contrast between Soma as god and amśu– as material unit is clear from the following mantra (TS 1.2.11a, etc. quoted in SB 3.4.3.19) amśur-amśus te deva somaapyaayataam indraayaikadhanavide ‘Let stalk after stalk of thine swell strong, O divine Soma, for Indra, the winner of one part of the booty!’. It is true that in Vedic literature amśu- refers only to the twigs of the Soma plant and not of any other plant, but it is only to be expected, given the prestige of the hymns, where the word was used in hieratic language for the whole Soma plant: in this poetic usage, it can be explained by a commonplace metonymy, and by the pressure to give many names to Soma… From the Tocharian vocabularies, we have Toch. A. *ancu ‘iron’, the basis of the derived adjective ancwaashi ‘made of iron’, to which corresponds Toch. B encuwo, with the parallel derived adjective encuwanne ‘made of iron’…The two forms go back to CToch. oencuwoen- non.sg. *oencuwo, the final part of which is a regular product of IE *-on. Nasal enlargement (from: IE *-on-) of nominal stems is very common in Tocharian. This noun is deprived of any convincing IE etymology (cf. Adams 1999:80), which is not surprising, since IE did not have a common word for ‘iron’. The connection with an Iranian form *aśwanya- according to Bailey (1957: 55-56), which does not fit in with the first cluster, was later abandoned (Bailey, Harold W., 1979, Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 32, 487). The CToch. form may reflect a term proper to the Central Asiatic region, cf. Chorasmian hnc’w ‘iron’ (‘iron tip’, see Benzing 1983: 319) < Iranian *anśuwan- (Schwartz, Martin, 1974. Irano-Tocharica. In: Philippe Gignoux & Tafazzoli (eds.), Memorial Jean de Menasce. Louvain: Imprimerie Orientaliste. p. 409): the formal shape is extremely close to the CToch. transposition, so that the Iranian and Tocharian words may have been borrowed from a common substratum language…The primitive system opposed Ved. ayas- (Av. aiiah-) ‘metal of utility’ to hiraNya- ‘noble metal’: the former term originally referred to ‘copper’, later to ‘iron’. I recall that the prominent colour of iron ore is rusty red, reddish-brown. Besides Toch. B eñcuwo (A *añcu), we know several names of metals in Tocharian: B yasa (A was) ‘gold’, B ñakante (A nkiñc) ‘silver’, B pilke ‘copper’, B lant* (adj. lantaṣṣe) ‘lead’…RV VIII.53.4c (Vālakhilya hymn) śiṣṭeṣu cit te madirāso amśavah‘Among the ś. also the exciting (Soma) plants belong to you (Indra)’. The form śiṣṭa- with variants śīṣṭra-, śīrṣṭra- testifies to a non-Aryan name with ‘intrusive -r-‘ (Kuiper 1991: 7,70).” (Pinault, ibid., p. 189)

I suggest that śiṣṭa– are mleccha, meluhha who are amśavah ‘amśu-, soma-workers’.

RV 8.53.4:

Trans. RV 8.53.4 Smite all our enemies and drive them away, may we all obtain their wealth; even among the śiṣṭa– s are you exhilarating Soma-stalks, where you fill yourself with the Soma

Pinault parallels amśu of Rigveda with añcu of Tocharian and Late Av. asu- ‘Haoma plant’. In Tocharian it means ‘iron’. Tocharin language as an Indo-European language has revealed a word anzu in Tocharian which meant ‘iron’. It is likely that this is the word used for soma in Rigveda.

Following this insightful analysis of the Ved. amśu- cognate Toch. añcu- there is a simple strategy to deal with Ved. soma- as a material related to the borrowed word: añcu-‘iron’…As the following are lexemes from Indian linguistic area attest, Ved. soma- might have referred to a metallic ore from the Mount Mujavant:

சோமமணல், s. Sand containing silver, வெள்ளிமணல். (R.)சோமனுப்பு, s. Rock-salt, as இந்துப்பு.(Winslow dictionary) sambr.o bica = gold ore (Mundarica)

hom = gold (Kannada)

somnakay = gold (Gypsy)

assem, s’m, asemon = electrum (Old Egyptian. cf. Joseph Needham)

soma man.al = sand containing silver ore (Tamil. Winslow lexicon)

According to RV 10.34.1, the Soma workers bought the resource from the sellers of Mujavata.

Trans. RV10.34.1 The large rattling dice exhilarate me as torrents borne on a precipice flowing in a desert; the exciting dice animate me as the taste of the Soma of Maujavat (delights the gods). [Flowing in a desert: iriṇe varvṛtānah: a reference to the dice; rolling on the dice-board; exciting dice: vibhi_taka, the seed of the myrobalan, used as a die; Maujavat: a mountain, where is said the best Soma is found].

If Tocharian speakers were aware of the Mujavant mountain and if Soma came from this mountain, what did Tocharian’s call Soma? Ancu! ‘iron’. This word ‘ancu’ is cognate with amśu which is used in the Rgveda to describe Soma. Soma was a metallic ore, a compound of silver and gold called by metallurgists as: electrum. Thus, for Rgvedic kavi, description of soma in metaphoric terms comparing it to a plant should not be treated literally as a reference to a ‘plant’. The reference could as well have been to a metallic ore subjected to refining process of smelting in fire which could raise upto 1500 degrees C in a yajña — agnishthoma, for example — which lasted continuously for 5 days and 5 nights.

Substitution of Soma with ‘plants’ is attested in many texts which post-date Rigveda and also in Avesta traditionof haoma, which is clearly a reference to a plant. But, the original reference in the root text of Rigveda can be explained as a metaphor for a metal/mineral ore of the Bronze Age.

Expiatory prayers in Indian tradition apologize to the divinities for the use of a substitute plant (somalataa, e.g. the pūtīka —Guilandina Bonduc?) because Soma had become unavailable. Texts provide an extensive list of plants that can be used as substitutes and end the list by saying that any plant is acceptable, provided it is yellow. (Angot, Michel, 2001, L’Inde Classique, Les Belles Lettres, Paris.)

Tandya Mahabrahmana 9.5.1-3 suggests the use of putika — basella cordifolia? — as a substitute for Soma. Other substitutes (e.g. Satapatha Brahmana 4.5.10; 5.3.3; 6.6.3) mentioned in many Brahmana texts were praprotha, adara, usana and prsniparni (122). Prsniparni had speckled leaves and its wood was used to protect from the negative effects caused by evil spirits. ApSS 14.24,13 suggests the use of rice and barley as substitutes for Soma.

Jaiminiya Brahmana notes that “if they do not find Soma…they should press out Phalguna plants with tawny panicles. Indra killed Vrtra with the Vajra. The Soma which flowed out of his nose, became these Phalguna plants with tawny panicles. And what was produced on account of the drawing out of the omentum, that became Phalguna plants with red panicles. Therefore they press out Phalguna plants with tawny panicles, since these are more suitable to be used in a sacrifice. They say: ‘This (pseudo-Soma) belongs to the Asuras, therefore it should not be pressed out (for a Soma sacrifice)’. (The answer should be:) ‘In the beginning all here was with the Asuras. The gods placed this with themselves after their victory. Therefore it should be used for the Soma pressing.’ If they should not find this (substitute), they should press out Utika plants. Indra having thrown the Vajra at Vrtra but thinking ‘I have not slain him’ entered the Utika plants. Someone whose Soma they steal loses his help (Uti). They find help for him (in the form of the Utika). When the head of the sacrifice was cut off, the sap which streamed forth out of it became the Utika plants. Therefore also they obviously press out sacrifice itself in the form of these Utika plants. If they should not find this they should press out light-coloured grass. When king Soma came to this world, then he stayed in the grasses. This is a trace of him. Thus they press him out (when they press out the grasses). If they should not find this, they should press out the Parna. When Suparna fetched king Soma, then the feather which fell down became the Parna (leaf). That is his trace. Thus they press him out (when they press out the Parna). If they should not find this, they may press out whatever plants there are. When Suparna fetched king Soma and broke him, then the drops which fell down, became these plants. And all plants are related to Soma. That is this trace of him. Him they thereby press out. At the morning pressing one should pour fresh milk, at the midday pressing boiled milk and at the third pressing coagulated milk to (these substitutes of Soma). It is obvious that they also consume this Soma, when they consume milk, for that is the sap of all the plants. (Excerpted from HW Bodewitz, 1990, The Jyotistoma ritual: Jaiminiya Brahmana I, 66-364, Brill, p. 203) Substrates of mleccha? Vedic, Avestan! soma, haoma

Trans. RV 10.124.3 Beholding the guest of another family, I have created the manifold abodes of sacrifice; I repeat praises, (wishing) good luck to the paternal foe-destroying (race of deities), I pass from a place unfit for sacrifice to a place where sacrifice can be offered. [Beholding the guest: vayāyāh = gantavyāyāh: beholding, i.e., following the course of, the guest, i.e., the sun, who is connected with a different region to be traversed (the sky) than that which is my abode, viz., the earth].

One statement is emphatic in RV 10.124.3 which uses the expression pitre asurAya,’Father Asura’as the primeval world of undivided unity. I suggest that Asura signified mleccha, meluhha speakers.

RV 9.74.4 connects Soma to the cosmic order with the expression, Rtasya nAbhi, ‘the navel of the cosmic order’ in reference to the birth of Soma of life. This expression takes the Rigveda metaphor into a transcendental AdhyAtmika, spiritual plane – again, emphasizing that the references to Soma in chandas text should be interpreted metaphorically. So, it is NOT a plant, it is the phenomenon of some divine intervention in transmutation of mere earth and stones in the medium of fire-altar. It is clear that the text of the chandas is at many levels of prayer, from the gross material resource level to transcendence.

The recurrent refrain of references to Soma is an association with wealth, thus making the processing of this phenomenon an important life-activities of the mleccha, meluhha among Bharatam Janam

RV 9.71.2 The metaphors and narratives of RV 9.71.2 refer to Sauma’s asurya varNam, ‘Asuric colour’ placing asura-s as elder brothers of deva-s declaring them as two moieties (say, dasa-varNa and arya-varNa). Like Varuna, Sarasvati, Agni, Soma is also Asurya. In the course of the yajña, Soma casts off his Asura moiety that is his and becomes deva.

RV9.72.7 Soma is the cosmic pillar which supports the sky in the world centre. This pillar has sahasrbhRSTi, i.e. an epithet of Vajra, with a thousand sharp points elaborated in RV 9.83.5, RV 9.86.40:

Trans. RV 9.83.5 Possessed of water, you go clothed in the liquid water, to the great celestial abode to (take) the sacrifice; as king you ascend to the battle, mounted to your filter-chariot; armed with a thousand weapons you win (us) abundant food. [In the liquid water: havih in contrast to nabhah; to the battle: i.e., the sacrifice].

Trans. RV 9.86.40 The wave of the swee-flavoured (Soma) excites voices (of praise); clothed in water the mighty one plunges (into the pitcher); the king whose chariot is the filter mounts for the conflict, and, armed with a thousand weapons, wins ample sustenance (for us).

One characteristic is that Soma is in plural and signifies vasUni RV 9.15.6

Trans. RV 9.15.6 Overpowering at the juncture of time the discomfited concealers (the rāks.asas), he descends upon those doomed to destruction. [Another reading (St. Petersburg Dictionary): ‘at the juncture of time passing beyond the solid treasures (of heaven and earth), he descends upon the young Soma’].

The significance of Soma as wealth in plural is consistent with the description of the processing in Taittiriya Samhita: अम्शुर अम्शुष ते देवा सोमाप्यायतां इन्द्रायैकधनाविदे (TS 1.2.11a cited in ŚB 3.4.3.19)

Let stalk after stalk of thine swell strong, O divine Soma, for Indra, the winner of one part of the booty!

Jyotishtoma yajña

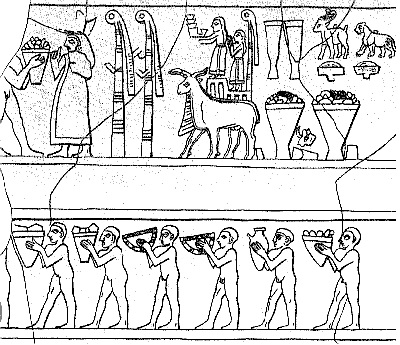

Avantaradiksa comes to an end and Agnidhriya and Ahavaniya offerings are made. Next morning, Prataranuvaaka is addressed to Agni and Aśvins and offerings made to Indra, Harivant, Indra, Pusan, Sarasvati, Bharati, Indra, Mitra and Varuna. Then the ceremony of fetching waters to mix Soma begins.

This is preceded by the offering of cups of curds, butter or soma when only a few stalks are pressed. In the Vajapeya and Rajasuya yajña Amsu and Adaabhya cups are used. Amsu cup is for sour milk merely touched with soma stalks. Adaabhya cup is for soma. Upabsusavana provides soma for the Upansu cup. Three rounds of pressings ocur: the Adhvaryu, Pratiprasthatr and Unnetr pour the mix into the Adhavaniya vessel filled with water and pass it through a sieve to the wooden tub. Unnetr draws soma from the Adhavaniya with a vessel and pours it into Hotr’s cup. The yajnika pours from it an unbroken stream on the sieve from which the next cups are drawn for offering, the Antaryama, Aindrayaava, Maitraavaruna, Cukra, Manthin, Agrayana, Ukthya and Dhruva. This is the reason why they are called dhaaraagrhas (as distinct from other cups), which are made full from the wooden tub with the vessel called Pariplavaa. Rest of soma is placed in the Putabhrt vessel, retaining a part needed to fill the goblets, camasas of the priests. After libations to atone for loss of drops of soma, bahispavamaana stotra is performed outside the sadas.

Emptied cups are filled again and placed on the back part of the southern soma cart. This is Naaraaśamsa allotted to the fathers as Avamas, Urvas and Kaavyas.

What is the Amsu cup? What is the Adaabhya cup?

May the Amsu cup for me, the Rasmi, the Adabhya, the overlord (cup), the Upansu, the Antaryama, the (cup) for Indra and Vayu, the (cup) for Mitra and Varuna, the (cup) for the Asvins, the Pratiprasthana (cup) the Sukra, the Manthin, the Agrayana, the (cup) for the All gods, the Dhruva, the (cup) for Vaisvanara, the season cups [1], the Atigrahyas, the (cup) for Indra and Agni, the (cup) for the All gods, the (cups) for the Maruts, the (cup) for Mahendra, the (cup) for Aditya, the (cup) for Savitr the (cup) for Sarasvati, the (cup) for Pusan, the (cup) for Tvastr() with the wives (of the gods), the Hariyojana (cup) (prosper for me through the sacrifice).(Shukla Yajurveda, 4.7)

Offspring and cattle are born through the cups, goats and sheep through the Upansu and Antaryama, men through the Sukra and Manthin, whole hooved animals through the season cups, kine through the Aditya cup…(The stone) for pressing out the Upansu (cup) is this Aditya Vivasvant; it lies round this Soma drink until the third pressing. The Upansu is the breath; in that the first and the, last cups are drawn with the Upansu vessel, verily they follow forward the breath, they follow back the breath.(ibid., 6.5)

अ-दाभ्य N. of a libation (ग्रह) in the ज्योतिष्टोम sacrifice (Monier-Williams,p.18).

Both Avestan haoma and Sanskrit soma derived from proto-Indo-Iranian *sauma. The linguistic root of the word haoma, hu-, and of soma, su-, suggests ‘press’ or ‘pound’. [Taillieu, Dieter and Boyce, Mary (2002). “Haoma”. Encyclopaedia Iranica. New York: Mazda Pub.] The name of the Scythian tribe Hauma-varga is related to the word, and probably connected with the ritual. The word is derived from an Indo-Iranian root *sav- (Sanskrit sav-/su) “to press”, i.e. *sau-ma- is the drink prepared by pressing the stalks of a plant. [K.F.Geldner, Der Rig-Veda. Cambridge MA, 1951, Vol. III: 1-9] The root is Proto-Indo-European (*sew(h)-)[M. Mayrhofer, Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindoarischen, Heidelberg 1986–2000, vol II: 748].

The root word is also relatable to P. sã̄vā ʻ grey, greyish, green ʼ; N. sāũ ʻ dark – coloured in the following etyma: śyāmá ʻ black, swarthy, dark — blue ʼ AV., °aka<-> VarBr̥S. 2. śyāmā — f. ʻ hen cuckoo ʼ VarBr̥S., ʻ *hen pheasant, hen golden oriole ʼ (opposed to bright cock bird s.v. *lōhiṣṭha — ). 3. *śyāmī — ʻ spleen ʼ (semant. cf. Psht. tōrai ~ tōr ʻ black ʼ EVP 82). [Cf. śyāvá — ]

1. Pa. sāma — ʻ black, dark, golden — coloured ʼ; Pk. sāma<-> ʻ black, dark — blue ʼ; Paš.lauṛ. šāmāk (< *śyāmakka — ), f. šaməč (< *śyāmikkī– ) ʻ black ʼ, kch. nir. weg. sāmek, kuṛ. chil. ṣāmāk (ṣ — after ṣōṇāˊk ʻ red ʼ s.v. śōṇá — 1?); K. śômu ʻ dark blue, dark brown ʼ, hômu ʻ dark grey ʼ, hām f. ʻ dirtiedness ʼ; P. sã̄vā ʻ grey, greyish, green ʼ; N. sāũ ʻ dark — coloured ʼ; A. xāũ, xã̄o ʻ swarthy, lightish dark ʼ; G. sām ʻ black, dark ʼ; Si.sam — van ʻ black colour ʼ. 2. Ash. sã̄ — waċūˊ ʻ hen monal pheasant ʼ (waċūˊ < *vāśuka — Add.), Kt. šōm; Wg. ċām, ċäm f. ʻ hen golden oriole ʼ, Tor. šām f.; Phal. Sh.pales.šām f. ʻ hen of either bird ʼ; K. “haum” f. ʻ hen pheasant ʼ. 3. Bshk. šēm ʻ spleen ʼ, Tor. šam, Phal. šēmi f., Sh.pales. šōm, jij. šō˘m. śyāmalá — ; — śyāmālatā — ? Addenda: śyāmá — : WPah.kṭg. śáũɔ ʻ blue ʼ.(CDIAL 12664).

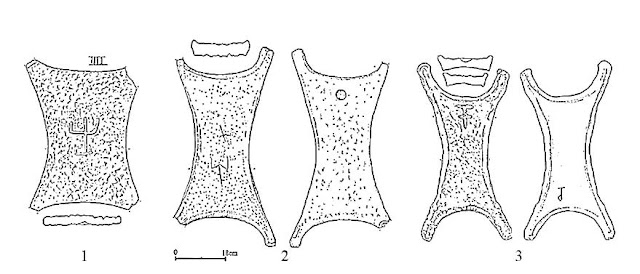

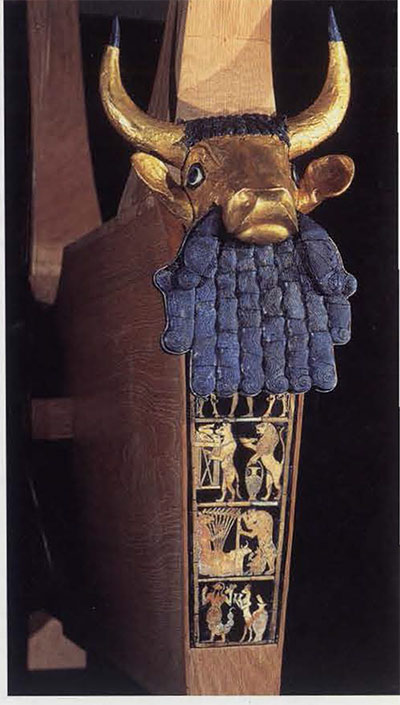

I suggest that the PIE verb root *sew(h)- ‘to press’ is also relatable to crushing amśu/soma with stones, subjected to yajña in fire, to yield ‘molten metal’ metaphored as a drink. See: Kalyanaraman, S., 2004, Indian Alchemy: Soma in the Veda. cf. S. Kalyanaraman, 2008, Sarasvati: Soma yajña and the Veda. The argument: Rigveda is a metallurgical allegory; soma is electrum ore. cf. S. Mahdihassan, 1991, The vedic gods Agni, Indra and Soma as interrelated: A study of Soma,Indian Journal of History of Science, 26(1), pp. 11-15 yūpa mēḍhā ‘stake’ is an Indus Script hieroglyph rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.), med ‘copper’ (Slavic) The vedic texts use the glosses yupa, skambha, yaṣṭi, vajra while the synonym in Prakritam is mēḍhā ‘stake, pillar.’ Rebus: मेधः mēdhḥ (com. मेधो युद्धयज्ञः । ‘यज्ञो वै मेधः’ इति श्रुतेः ।), an offering, an oblation. (Samskritam)

An exposition by Sadhashiv A Dange: “the yūpa is described as being the emblem of the sacrifice (RV III.8.8 yajñasya ketu). Though it is fixed on the terrestrial plane at the sacrifice, it is expected to reach the path of the gods. Thus, about the many sacrificial poles (fixed in the Paśubandha, or at the Horse-sacrifice) it is said that they actually provide the path for reaching the gods (ib., 9 devānām api yanti pāthah). They are invoked to carry the oferings to the gods (ib., 7 te no vyantu vāryam devatrā), which is the prerogative of the fire-god who is acclaiemd as ‘messenger’ (dūta); cf. RV I.12.1 agrim dūtam vṛṇimahe). In what way is the yūpa expected to carry the chosen offering to the gods? It is when the victim is tied to the sacrificial pole. The prallelism between the sacrificial fire and the yūpa is clear. The fire carries it through the smoke and flames; the yūpa is believed to carry it before that, when the victim is tied to it, as its upper end is believed to touch heaven. A more vivid picture obtains at the yajapeya. Here the yūpa is eight-angled, corresponding to the eight qurters. (Śat. Br. V.2.1.5 aṣṭāśrir yūpo bhavati; the reason given is that the metre Gayatri has eight letters in one foot; not applicable here, as it is just hackneyed. At Taitt.Sam. I.7.9.1, in this context a four-angled yūpa is prescribed.) The one yūpa is conceived as touching three worlds: Heaven, Earth and the nether subterranean. The portion that is above the caṣāla (ring) made of wheat-dough (cf. Śat. Br. V.2.1.6 gaudhūmam caṣālam bhavati) represents Heaven. This is clear from the rite of ascending to the caṣāla, made of wheat-dough, in the Vajapeya sacrifice. The sarificer ascends to it with the help of a ladder (niśrayaṇī); and, while doing so, calls upon his wife, ‘Wife, come; let us ascend to Heaven’. As soon as he ascends and touches the caṣāla, he utters, ‘We have reached Heavven, O gods’ (ib., 12). According to Sāyaṇa on the Taiit.Sam. I.7.9.1, the sacrificer stretches his hands upwards when he reaches the caṣāla and says, ‘We have reached the gods that stay in heaven’ (udgṛhītābhyām bāhubhyām). Even out of the context of the Vajapeya, when the yūpa is erected (say in the Paśubandha), it is addressed, ‘For the earth you, for the mid-region you, for heaven you (do we hoist you)’ (Taitt. Sam. I.3.6.1-3; cf. śat. Br. III.7.1.5-6). The chiselled portion of the yūpa is above the earth. So, from the earth to heaven, through the mid-region the yūpa represents the three-regions. The un-chiselled portion of the yūpa is fixed in the pit (avaṭa) and the avaṭa, which represents the subterranean regions, is the region of the ancestors (ib.4).The yūpa, thus, is the axis mundi…Then, it gave rise to various myths, one of them being that of the stūpa of Varuṇa, developing further into Aśvattha tree, which is nothing but a symbol of a tree standing with roots in the sun conceived as the horse (aśva-stha = aśvattha), a symbol obtaining at various places in the Hindu tradition. It further developed into the myth of the churning staff of the mountain (Amṛta-manthana); and yet further, into the myth of Vasu Uparicara, whom Indra is said to have given his yaṣṭi (Mb.Adi. 6y3.12-19). This myth of the yaṣṭi was perpetuated in the ritual of the Indra-dhvaja in the secular practice (Brhatsamhita, Chapter XLII), while in the śrauta practice the original concept of the axis mundi was transformed into the yūpa that reached all regions, including the under-earth. There is another important angle to the yūpa. As the axis mundi it stands erect to the east of the Uttaravedi and indicates the upward move to heaven. This position is unique. If one takes into account the position of the Gārhapatya and the āhavaniya fireplaces, it gets clear that the march is from the earth to heaven; because, the Gārhapatya is associated with this earth and it is the household fire (cf. gṛhā vai gārhapatyah, a very common saying in the ritual texts), and the seat of the sacrificer’s wife is just near it, along with the wives of the gods, conceptually. From this fire a portion is led to the east, in the quarter of the rising sun (which is in tune with such expressions as prāñcam yajñam pra nayatā sahāyah, RV X.101.2); where the Ahavaniya fireplace is structured. As the offerings for the gods are cast in the Ahavaniya, this fire is the very gate of heaven. And, here stands, the yūpa to its east taking a rise heavenwards. This is, by far, the upward rise. But, on the horizontal plane, the yūpa is posted half-inside, half-outside the altar. The reason is, that thereby it controls the sacred region and also the secular, i.e. both heaven and earth, a belief attested by the ritual texts. (Tait. Sam. VI.6.4.1; Mait. Sam. III.9.4).” (Dange, SA, 2002, Gleanings from Vedic to Puranic age, New Delhi, Aryan Books International, pp. 20-24).

The Sukta RV X.101 reads, explaining the entire yajña as a metaphor of golden-tinted soma poured into a wooden bowl, a smelting process yielding weapons of war and transport and implements of daily life:

10.101.01 Awake, friends, being all agreed; many in number, abiding in one dwelling, kindle Agni. I invoke you, Dadhikra, Agni, and the divine Us.as, who are associated with Indra, for our protection. [In one dwelling: lit., in one nest; in one hall].

10.101.02 Construct exhilarating (hymns), spread forth praises, construct the ship which is propelled by oars, prepare your weapons, make ready, lead forth, O friends, the herald, the adorable (Agni).

10.101.03 Harness the ploughs, fit on the yokes, now that the womb of earth is ready, sow the seed therein, and through our praise may there be abundant food; may (the grain) fall ripe towards the sickle. [Through our praise: sow the seed with praise, with a prayer of the Veda; śrus.t.i = rice and other different kinds of food].

10.101.04 The wise (priests) harness the ploughs, they lay the yokes apart, firmly devoted through the desire of happiness. [Happiness: sumnaya_ = to give pleasure to the gods].

10.101.05 Set up the cattle-troughs, bind the straps to it; let us pour out (the water of) the well, which is full of water, fit to be poured out, and not easily exhausted.

10.101.06 I pour out (the water of) the well, whose cattle troughs are prepared, well fitted with straps, fit to be poured out, full of water, inexhaustible.

10.101.07 Satisfy the horses, accomplish the good work (of ploughing), equip a car laden with good fortune, pour out (the water of) the well, having wooden cattle-troughs having a stone rim, having a receptable like armour, fit for the drinking of men.

10.101.08 Construct the cow-stall, for that is the drinking place of your leaders (the gods), fabricate armour, manifold and ample; make cities of metal and impregnable; let not the ladle leak, make it strong.

10.101.09 I attract, O gods, for my protection, your adorable, divine mine, which is deserving of sacrifice and worship here; may it milk forth for us, like a large cow with milk, giving a thousand strreams, (having eaten) fodder and returned.

10.101.10 Pour out the golden-tinted Soma into the bowl of the wooden cup, fabricate it with the stone axes, gird it with ten bands, harness the beast of burden to the two poles (of the cart).

10.101.11 The beast of burden pressed with the two cart-poles, moves as if on the womb of sacrifice having two wives. Place the chariot in the wood, without digging store up the Soma.

10.101.12 Indra, you leaders, is the giver of happiness; excite the giver of happiness, stimulate him, sport with him for the acquisition of food, bring down here, O priests, Indra, the son of Nis.t.igri_, to drink the Soma. [Nis.t.igri_ = a name of Aditi: nis.t.im ditim svasapatni_m girati_ti nis.t.igri_raditih].

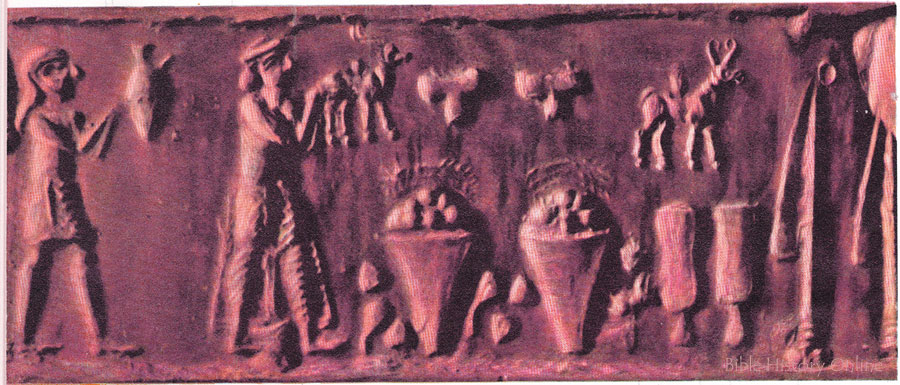

As the yajnika together with his dharmapatni performs vājapeya soma yaga, the attainment of heaven occurs when the yajnika touches the wheat (top-piece) (SBr. 5.1.2.12-16). This top-piece is the चषालः caṣāla signified by Varāha’s snout and which signifies चषालः caṣāla ‘anna, food’ for pyrolysis to carburize metal into hard alloy, in the smelting process.

Wheat which is annam is the wheat chaff constituting the चषालः caṣāla. This is the vajra, adamantine glue which achieves the process of caburization in pyrolysis to attain hard alloys.

The depiction of this wheat chaff is rendered in Indus Script cipher. Hierroglyph: bhūĩ ‘earth’ signified as bhudevi carried on the चषालः caṣāla ‘snout of boar’ varāha Rebus: bhũ ‘wheat chaff’ as annam.

Procedure fo vājapeya soma yaga

Satapatha Brahmana elucidates the process using wheat chaff as चषालः caṣāla, the metaphor is ascent on Yupa to heaven.

5.2.1.[9]

atha niśrayaṇo niśrayati | sa dakṣiṇata udaṅ roheduttarato vā dakṣiṇā

dakṣiṇatastvevodaṅ rohettathā hyudagbhavati

5:2:1:99. He then leans a ladder (against the post). He may ascend either from the south northwards, or from the north southwards; but let him rather ascend from the south northwards (udak), for thus it goes upwards (udak).

5.2.1.[10]

sa rokṣyanjāyāmāmantrayate | jāya ehi svo rohāveti rohāvetyāha jāyā

tadyajjāyāmāmantrayate ‘rdho ha vā eṣa ātmano yajjāyā tasmādyāvajjāyāṃ na vindate naiva tāvatprajāyate ‘sarvo hi tāvadbhavatyatha yadaiva jāyāṃ vindate ‘tha prajāyate tarhi hi sarvo bhavati sarva etāṃ gatiṃ gacānīti tasmājjāyāmāmantrayate

5:2:1:1010. Being about to ascend, he (the Sacrificer) addresses his wife, ‘Come, wife, ascend we the sky!’–‘Ascend we!’ says the wife. Now as to why he addresses his wife: she, the wife, in sooth is one half of his own self; hence, as long as he does not obtain her, so long he is not regenerated, for so long he is incomplete. But as soon as he obtains her he is regenerated, for then he is complete. ‘Complete I want to go to that supreme goal,’ thus (he thinks) and therefore he addresses his wife.

5.2.1.[11]

sa rohati | prajāpateḥ prajā abhūmeti prajāpaterhyeṣa prajā bhavati yo vājapeyena yajate

5:2:1:1111. He ascends, with, ‘We have become Prajâpati’s children;’ for he who offers the Vâgapeya indeed becomes Prajâpati’s child:

5.2.1.[12]atha godhūmānupaspṛśati | svardevā aganmeti svarhyeṣa gacati yo vājapeyena yajate

5:2:1:1212. He then touches the wheat (top-piece) 2, with, ‘We have gone to the light, O ye gods!’ for he who offers the Vâjapeya, indeed goes to the light.

5.2.1.[13]tadyadgodhūmānupaspṛśati | annaṃ vai godhūmā annaṃ vā eṣa ujjayati yo vājapeyena yajate ‘nnapeyaṃ ha vai nāmaitadyadvājapeyaṃ

tadyadevaitadannamudajaiṣīttenaivaitadetāṃ gatiṃ gatvā saṃspṛśate tadātmankurute tasmādgodhūmānupaspṛśati

5:2:1:1313. And as to why he touches the wheat: wheat is food, and he who offers the Vâgapeya, wins food, for vâga-peya is the same as anna-peya (food and drink): thus whatever food he has thereby won, therewith now that he has gone to that supreme goal, he puts himself in contact, and possesses himself of it,–therefore he touches the wheat (top-piece).

5.2.1.[14]atha śīrṣṇā yūpamatyujjihīte | amṛtā abhūmeti devalokamevaitenojjayati

5:2:1:1414. He then rises by (the measure of) his head over the post, with, ‘We have become immortal!’ whereby he wins the world of the gods.

5.2.1.[15]

atha diśo ‘nuvīkṣamāṇo japati | asme vo astvindriyamasme nṛmṇamuta kraturasme varcāṃsi santu va iti sarvaṃ vā eṣa idamujjayati yo vājapeyena yajate prajāpatiṃ hyujjayati sarvamu hyevedam prajāpatiḥ so ‘sya sarvasya yaśa indriyaṃ vīryaṃ saṃvṛjya tadātmandhatte tadātmankurute tasmāddiśo ‘nuvīkṣamāṇo japati

5:2:1:1515. Thereupon, while looking in the different directions, he mutters (Vâg. S. IX, 22), ‘Ours be your power, ours your manhood and intelligence ours be your energies!’ For he who offers the Vâgapeya wins everything here, winning as he does Prajâpati, and Prajâpati being everything here;–having appropriated to himself the glory, the power, and the strength of this All, he now lays them within himself, makes them his own: that is why he mutters, while looking in the different directions.

5.2.1.[16]athainamūṣapuṭairanūdasyanti | paśavo vā ūṣā annaṃ vai paśavo ‘nnaṃ vā eṣa ujjayati yo vājapeyena yajate ‘nnapeyaṃ ha vai nāmaitadyadvājapeyaṃ

tadyadevaitadannamudajaiṣīttenaivaitadetāṃ gatiṃ gatvā saṃspṛśate tadātmankurute tasmādenamūṣapuṭairanūdasyanti

5:2:1:1616. They throw up to him bags of salt; for salt means cattle, and cattle is food; and he who offers the Vâgapeya wins food, for vâga-peya is the same as anna-peya: thus whatever food he thereby has gained, therewith now that he has gone to the supreme goal, he puts himself in contact, and makes it his own,–therefore they throw bags of salt up to him. 5.2.1.[17]āśvattheṣu palāśeṣūpanaddhā bhavanti | sa yadevādo ‘śvatthe tiṣṭhata indro maruta upāmantrayata tasmādāśvattheṣu palāśeṣūpanaddhā bhavanti viśo ‘nūdasyanti viśo vai maruto ‘nnaṃ viśastasmādviśo ‘nūdasyanti saptadaśa bhavanti saptadaśo vai prajāpatistatprajāpatimujjayati

5:2:1:1717. They (the pieces of salt) are done up in asvattha (ficus religiosa) leaves: because Indra on that (former) occasion called upon the Maruts staying on the Asvattha tree 1, therefore they are done up in asvattha leaves. Peasants (vis) throw them up to him, for the Maruts are the peasants, and the peasants are food (for the nobleman): hence peasants throw them up. There are seventeen (bags), for Prajâpati is seventeenfold: he thus wins Prajâpati.

5.2.1.[18]athemāmupāvekṣamāṇo japati | namo mātre pṛthivyai namo mātre pṛthivyā iti

bṛhaspaterha vā abhiṣiṣicānātpṛthivī bibhayāṃ cakāra mahadvā ayamabhūdyo

‘bhyaṣeci yadvai māyaṃ nāvadṛṇīyāditi bṛhaspatirha pṛthivyai bibhayāṃ cakāra yadvai meyaṃ nāvadhūnvīteti tadanayaivaitanmitradheyamakuruta na hi mātā putraṃ hinasti na putro mātaram

5:2:1:1818. Thereupon; while looking down upon this (earth), he mutters, Homage be to the mother Earth! homage be to the mother Earth!’ For when Brihaspati had been consecrated, the Earth was afraid of him, thinking, ‘Something great surely has he become now that he has been consecrated: I fear lest he may rend me asunder 2!’ And Brihaspati also was afraid of the Earth, thinking, ‘I fear lest she may shake me off!’ Hence by that (formula) he entered into a friendly relation with her; for a mother does not hurt her son, nor does a son hurt his mother.

5.2.1.[19]bṛhaspatisavo vā eṣa yadvājapeyam | pṛthivyu haitasmādbibheti mahadvā

ayamabhūdyo ‘bhyaṣeci yadvai māyaṃ nāvadṛṇīyādityeṣa u hāsyai bibheti yadvai meyaṃ nāvadhūnvīteti tadanayaivaitanmitradheyaṃ kurute na hi mātā putraṃ hinasti na putro mātaram

5:2:1:1919. Now the

Brihaspati consecration 3 is the same as the Vâ

gapeya; and the earth in truth is afraid of that (Sacrificer), thinking, ‘Something great surely has he become now that he has been consecrated: I fear lest he may rend me asunder!’ And he himself is afraid of her, thinking, ‘I fear lest she may shake me off!’ Hence he thereby enters into a friendly relation with her, for a mother does not hurt her son; neither does a son hurt his mother.

5.2.1.[20]atha hiraṇyamabhyavarohati | amṛtamāyurhiraṇyaṃ tadamṛta āyuṣi pratitiṣṭhati

5:2:1:2020. He then descends (and treads) upon a piece of gold;–gold is immortal life: he thus takes his stand on life immortal.

5.2.1.[21]athājarṣabhasyājinamupastṛṇāti | tadupariṣṭādrukmaṃ nidadhāti

tamabhyavarohatīmāṃ vaiva

5:2:1:2121. Now (in the first place) he (the Adhvaryu) spreads out the skin of a he-goat, and lays a (small) gold plate thereon: upon that–or indeed upon this (earth) itself–he (the Sacrificer) steps.

5.2.1.[22]athāsmā āsandīmāharanti | uparisadyaṃ vā eṣa jayati yo jayatyantarikṣasadyaṃ tadenamuparyāsīnamadhastādimāḥ prajā upāsate tasmādasmā āsandīmāharanti

5:2:1:2222. They then bring a throne-seat for him; for truly he who gains a seat in the air 1, gains a seat above (others): thus these subjects of his sit below him who is seated above,–this is why they bring him a throne-seat.

5.2.1.[23]audumbarī bhavati | annaṃ vā ūrgudumbara ūrjo ‘nnādyasyāvaruddhyai

tasmādaudumbarī bhavati tāmagreṇa havirdhāne jaghanenāhavanīyaṃ nidadhāti

5:2:1:2323. It is made of udumbara wood,–the Udumbara tree being sustenance, (that is) food,–for his obtainment of sustenance, food: therefore it is made of udumbara wood. They set it down in front of the Havirdhâna (cart-shed), behind the Âhavanîya (fire).

5.2.1.[24]athājarṣabhasyājinamāstṛṇāti | prajāpatirvā eṣa yadajarṣabha etā vai prajāpateḥ pratyakṣatamāṃ yadajāstasmādetāstriḥ saṃvatsarasya vijāyamānā dvau trīniti janayanti tatprajāpatimevaitatkaroti tasmādajarṣabas yājinamāstṛṇāti

5:2:1:2424. He then spreads the goat-skin thereon; for truly the he-goat is no other than Prajâpati, for they, the goats, are most clearly of Prajâpati (the lord of generation or creatures);–whence, bringing forth thrice in a year, they produce two or three 2: thus he thereby makes him (the Sacrificer) to be Prajâpati himself,–this is why he spreads the goat-skin thereon.

5.2.1.[25]sa āstṛṇāti | iyaṃ te rāḍiti rājyamevāsminnetaddadhātyathainamāsādayati yantāsi yamana iti yantāramevainametadyamanamāsām prajānāṃ karoti dhruvo ‘si dharuṇa iti dhruvamevainametaddharuṇamasmiṃloke karoti kṛṣyai tvā kṣemāya tvā rayyai tvā poṣāya tveti sādhave tvetyevaitadāha

5:2:1:2525. He spreads it, with, ‘This is thy kingship 1!’ whereby he endows him with royal power. He then makes him sit down, with, Thou art the ruler, the ruling lord!’ whereby he makes him the ruler, ruling over those subjects of his Thou art firm, and steadfast!’ whereby he makes him firm and stedfast in this world;–‘Thee for the tilling!–Thee for peaceful dwelling!–Thee for wealth!–Thee for thrift!’ whereby he means to say, ‘(here I seat) thee for the welfare (of the people).’ SBr. 5.1.2.12-18

He then touches the wheat (top-piece)[8], with, [Page 33] ‘We have gone to the light, O ye gods!’ for he who offers the Vājapeya, indeed goes to the light. - And as to why he touches the wheat: wheat is food, and he who offers the Vājapeya, wins food, for vāja-peya is the same as anna-peya (food and drink): thus whatever food he has thereby won, therewith now that he has gone to that supreme goal, he puts himself in contact, and possesses himself of it,–therefore he touches the wheat (top-piece).

- He then rises by (the measure of) his head over the post, with, ‘We have become immortal!’ whereby he wins the world of the gods.

- Thereupon, while looking in the different directions, he mutters (Vāj. S. IX, 22), ‘Ours be your power, ours your manhood and intelligence ours be your energies!’ For he who offers the Vājapeya wins everything here, winning as he does Prajāpati, and Prajāpati being everything here;–having appropriated to himself the glory, the power, and the strength of this All, he now lays them within himself, makes them his own: that is why he mutters, while looking in the different directions.

- They throw up to him bags of salt; for salt means cattle, and cattle is food; and he who offers theVājapeyawins food, for vāja-peya is the same as anna-peya: thus whatever food he thereby has gained, therewith now that he has gone to the supreme goal, he puts himself in contact, and makes it his own,–therefore they throw bags of salt up to him.

- They (the pieces of salt) are done up in aśvattha [Page 34] (ficus religiosa) leaves: because Indra on that (former) occasion called upon the Maruts staying on the Aśvattha tree[9], therefore they are done up in aśvattha leaves. Peasants (viś) throw them up to him, for the Maruts are the peasants, and the peasants are food (for the nobleman): hence peasants throw them up. There are seventeen (bags), for Prajāpati is seventeenfold: he thus wins Prajāpati.

- Thereupon; while looking down upon this (earth), he mutters, Homage be to the mother Earth! homage be to the mother Earth!’ For when Bṛhaspati had been consecrated, the Earth was afraid of him, thinking, ‘Something great surely has he become now that he has been consecrated: I fear lest he may rend me asunder[10]!’ And Bṛhaspati also was afraid of the Earth, thinking, ‘I fear lest she may shake me off!’ Hence by that (formula) he entered into a friendly relation with her; for a mother does not hurt her son, nor does a son hurt his mother.

SBr. ३.७.१.[१८] अथ चषालमुदीक्षते । तद्विष्णोः परमं पदं सदा पश्यन्ति सूरयः दिवीव चक्षुराततमिति वज्रं वा एष प्राहार्षीद्यो यूपमुदशिश्रियत्ता विष्णोर्विजितिम्पश्यतेत्येवैतदाह यदाह तद्विष्णोः परमं पदं सदा पश्यन्ति सूरयः दिवीव चक्षुराततमिति

Translation of Eggeling is as follows:

- He then looks up at the top-ring with (Vāj. S. VI, 5; Rig-veda I, 22, 20), ‘The wise ever behold that highest step of Viṣṇu, fixed like an eye in the heaven.’ For he who has set up the sacrificial stake has hurled the thunderbolt: ‘See ye that conquest of Viṣṇu!’ he means to say when he says, ‘The wise ever behold that highest step of Viṣṇu, fixed like an eye in the heaven.’

Eggeling’ translation of Sbr. Pt III, Vol. XLI, Oxford, 1894, p.31 says:

“The post is either wrapped up or bound up in 17 cloths for Prajapati is 17-fold.’ The top of the Yupa carries a wheel called caṣāla in a horizontal position. The indrakila too is adorned with a wheel-ike object made of white cloth, but it is placed in a vertical position.

The process of reaching to heaven (which may be elaborated by a metaphor of obtaining amRtatva as in RV 1.72.1 and RV 3.38.4) is paralleled by the processing of a yajña as detailed in the Satapatha Brahmana:

SBr. ३.७.१.[१८] अथ चषालमुदीक्षते । तद्विष्णोः परमं पदं सदा पश्यन्ति सूरयः दिवीव चक्षुराततमिति वज्रं वा एष प्राहार्षीद्यो यूपमुदशिश्रियत्ता विष्णोर्विजितिम्पश्यतेत्येवैतदाह यदाह तद्विष्णोः परमं पदं सदा पश्यन्ति सूरयः दिवीव चक्षुराततमिति

Translation of Eggeling is as follows:

He then looks up at the top-ring with (Vāj. S. VI, 5; Rig-veda I, 22, 20), ‘The wise ever behold that highest step of Viṣṇu, fixed like an eye in the heaven.’ For he who has set up the sacrificial stake has hurled the thunderbolt: ‘See ye that conquest of Viṣṇu!’ he means to say when he says, ‘The wise ever behold that highest step of Viṣṇu, fixed like an eye in the heaven.’

A horizontally placed vishnu cakra is also a substitute for caṣāla. But the key in archaeometallurgical terms is wheat straw, which is a carburization mediation to harden wrought iron into steel. Thus, climbing up to the entire top portion of the Yupa as a metaphor is the attainment of immortality. This amRtatva in materialistic terms is the acquisition of muhã̄, ‘quantity of iron produced from a smelter’. Hence the mukha, mũh ‘face’ ligatured to the sivalinga atop the smelting structure shown on Bhutesvar sculptural frieze.kuTi ‘tree’ rebus: kuThi ‘smelter’

Notes taken from ‘The symbolism of the Indrakila’ Senarat Paranavitana, Leelananda Prematilleka, Johanna Engelberta van Lohulzen-De Leeuw, 1978, Senarat Paranavitana Commemoration Volume, BRILL 1978, p.247)

caṣālḥ चषालः is a Rigveda citation of a ring atop the Soma Yaga yupa. caṣālḥचषालः is a Vajra, is annam (godhUma गोधूम ‘wheat chaff’ in processes of carburization and pyrolysis).

Process of carburization of metal explained in Vedic text शत-पथ-ब्राह्मण

That caṣālḥ चषालः is godhuma is specified in शत-पथ-ब्राह्मण in Vedic metaphor in chandas textual tradition.

शत-पथ-ब्राह्मण vividly, metaphorically describes Vajapeya ascent on the Yupa to heaven (amṛtā abhūmeti ‘we have become immortal’) with metaphors of गो ‘thunderbolt’ गो-धूम ‘wheat’ rebus: ‘earth-smoke’. The expression गो-धूम can be explained as composed of गो and धूम Attainment of immortality is a metaphor for the successful processing of Soma yaga yielding Soma, molten metal (hence, the metaphor of Vajapeya, ‘drink of strength or battle’. Hence, the metaphor of vajra, thunderbolt weapon.

गो or गो-धूम is the thunderbolt weapon of Indra. It is चषालः caṣāla and वज्र vajra. धूम is smoke , vapour, mist which emanates from the yupa as a fiery pillar of light during the Vajapeya yajña or Soma processing or smelting process. Orthographically, the चषालः caṣāla is denoted as an अष्टाश्रि octagonal thunderbolt weapon carried by Vajrapani. Rudra is also VajrabAho.

I suggest that references in Rigveda related to Soma are metaphorical expressions of ‘drink’ in Chandas (Vedic Samskrtam), while the product processed results in a molten state.

According to Rigveda, Taittiriya Samhita and Satapatha Brāhmana, caṣāla on yupa (Skambha) is ‘wheat chaff’ godhuma rendered rebus as hieroglyph: varāha’s caṣāla, ‘snout of boar’. caṣāla as godhuma is annam; it is the carburization process to harden soft metal in yajña kunda. caṣāla mounted on a Yupa which is the Skambha, octagonal in shape, venerated in an adhyatmika enquiry in Atharva Veda Skambha Sukta (AV X.7,8). This is the quintessence of the Yajña in material terms to infuse carbon as a mineral into the carburization or metal alloy hardening process. This results in karaDi ‘hard alloy’. karaNDi is venerated as Agni.

Trans. “That soma is king; this is the devas’ food. The devas eat it.” [Chandogya.Upanishad (Ch.Up. 5.10.4]

This statement of Chandogya Upanishad is an emphatic declaration that Soma is a metaphor.

- Mortals do not taste Soma. RV 10.85.3, 4 which suggest that Brahmana and those who dwell on earth do NOT partake of Soma. Similar refrain occurs in Atharva Veda. Hillebrandt and Oldenburg suggest that Soma is a metahpor for the sun or moon.

- माक्षिक, the fly, betrays Soma. RV 1.119.9 There is a pun on the word माक्षिक which also signifies ‘pyrites’ (secondary ores).

- Reference to Soma in the dual and plural RV 9.66.2,3,5 refer to Soma in dual, or plural (re-inforcing the allegorical nature of the descriptions.

The Vedic texts and translations are given below.

Item 1: Mortals do not taste Soma

Griffith translation: RV 10.85.1-4: 1. TRUTH is the base that bears the earth; by Surya are the heavens sustained. By Law the Adityas stand secure, and Soma holds his place in heaven. 2 By Soma are the Adityas strong, by Soma mighty is the earth. Thus Soma in the midst of all these constellations hath his place. 3 One thinks, when they have brayed the plant, that he hath drunk the Soma’s juice; Of him whom Brahmans truly know as Soma no one ever tastes. 4 Soma, secured by sheltering rules, guarded by hymns in Brhati, Thou standest listening to the stones none tastes of thee who dwells on earth.

soma is not a drink of mortals: “one thinks to have drunk soma, when they crush the plant. Of him (soma), which the braahmanas know, no one ever tastes.”: RV X.85.3; same hymn in AV. XIV.1.3; “No earthly one eats you.” : RV X.85.4; soma is for Indra: “Boldy drink soma from tbe beaker, Indra!…”: AV VII.77; [Hillebrandt and Oldenburg treat soma as a metaphor for the moon or the sun]

This is the clearest statement that references to or attributes of Soma in the Vedic tradition, right from the Rigveda, should be viewed as metaphors. Even when Agni or ghee or Soma are viewed as products, the emphatic statement is that Soma is NOT for human digestion or consumption but associated with divinities, digested by the divinities (deva bhakshyanti) — not by mortals or worshippers in the sacred yajña.

It will thus be an error to interpret Soma as an edible product. Such interpretations that Soma is a hallucinogen or an inebriant are not sanctioned by tradition. If at all there is a refrain metaphor, it relates to processing of Soma to generate or obtain wealth.

There may be some questions raised based on received wisdom that translations refer to expressions of ‘drinking’ soma.

Here for example are two references from Rigveda: RV 8.48.3 nd RV 8.91.1-7

[08-048] HYMN XLVIII. Soma. 1. WISELY have I enjoyed the savoury viand, religious-thoughted, best to find out treasure, The food to which all Deities and mortals, calling it meath, gather themselves together. <337> 2 Thou shalt be Aditi as thou hast entered within, appeaser of celestial anger. Indu, enjoying Indra’s friendship, bring us – as a swift steed the car – forward to riches. 3 We have drunk Soma and become immortal; we have attained the light, the Gods discovered. Now what may foeman’s malice do to harm us? What, O Immortal, mortal man’s deception?

Griffith Translation RV 8.91.1-7

- DOWN to the stream a maiden came, and found the Soma by the way. Bearing it to her home she said, For Indra will I press thee out, for Sakra will I press thee out. 2 Thou roaming yonder, little man, beholding every house in turn, Drink thou this Soma pressed with teeth, accompanied with grain and curds, with cake of meal and song of praise. 3 Fain would we learn to know thee well, nor yet can we attain to thee. Still slowly and in gradual drops, O Indu, unto Indra flow. 4 Will he not help and work for us? Will he not make us wealthier? Shall we not, hostile to our lord, unite ourselves to Indra now? 5 O Indra, cause to sprout again three places, these which I declare,- My father’s head, his cultured field, and this the part below my waist. 6 Make all of these grow crops of hair, you cultivated field of ours, My body, and my father’s head. 7 Cleansing Apala, Indra! thrice, thou gavest sunlike skin to her, Drawn, Satakratu! through the hole of car, of wagon, and of yoke.

apAma may also mean ‘obtained’. Here:

आप 1 [p= 142,2] m. obtaining mfn. ifc. to be obtained (cf. दुर्°).n. (fr. 2. अप् Pa1n2. 4-2 , 37), a quantity of water , मल्लिनाथ on S3is3. iii , 72. Thus, the translation of apAma ‘we drank’ is of doubtful validity. Apala episode is beautiful. What she found was a stone with traces of soma (electrum, gold/silver compound as assem (Egyptian), noted by Joseph Needham).

In RV 8.48.3 ‘We have drunk…’? Amrutam is a metaphor. It means, we have obtained the Soma, amrutam (wealth).

These metaphors can be explainedby some examples of some crystals of electrum ore naturally found which justify such metahpors.

Round Mountain Mine, Toquima Range, Nye Co., Nevada, USA. A rich mass of finely defined octahedrally grown electrum over milky white crystalline quartz. Analysis shows the make up of electrum to be 66.7% gold, 33.3% silver.

Found in sand.Analysis got 73.14% Au 26.13% Ag. So this is electrum as the colour indicates.

Swauk Dist., Kittitas Co. Washington, USA. Very fragile. Found in sand.

Round Mountain Mine, Round Mountain, Round Mountain, Round Mountain District, Toquima Range, Nye Co., Nevada, USA

Electrum Mineral Facts:

Chemical Formula: Au(Ag) Gold and Silver alloy, more than 20% silver by weight.

Colors: Pale metallic gold, streak is the same.

Hardness: 2.5 to 3

Density: 12.5 to 15.5

The density is variable depending on the silver content.

Cleavage: Electrum is ductile and mallable. Also sectile, and can be cut with a knife like lead.

Crystallography: Isometric, commonly octahedral.

Usually in irregular plates, scales or masses, and seldom definitely crystallized.

Luster:. Metallic luster.

I agree with Georges Pinault about ams’u (Soma) as iron.

Avestan haoma (cognate soma) was based on herbal preparation, while Vedic soma of Soma samsthA was based on metallic stones.

Item 2: माक्षिक, the fly, betrays Soma

माक्षिक [p= 805,2] mfn. (fr. मक्षिका) coming from or belonging to a bee Ma1rkP. (Monier-Williams) मक्षिकः मक्षि (क्षी) का A fly, bee; भो उपस्थितं नयनमधु संनिहिता मक्षिका च M.2. -Comp. –मलम् wax. (Apte)

माक्षिक n. a kind of honey-like mineral substance or pyrites MBh.

उपरसः uparasḥउपरसः 1 A secondary mineral, (red chalk, bitumen, माक्षिक, शिलाजित &c)

Griffith translation: RV 1.119.1-10:1. HITHER, that I may live, I call unto the feast your wondrous car, thought-swift, borne on by rapid steeds. With thousand banners, hundred treasures, pouring gifts, promptly obedient, bestowing ample room. 2 Even as it moveth near my hymn is lifted up, and all the regions come together to sing praise. I sweeten the oblations; now the helpers come. Urjani hath, O Asvins, mounted on your car. 3 When striving man with man for glory they have met, brisk, measurcIess, eager for victory in fight, Then verily your car is seen upon the slope when ye, O Asvins, bring some choice boon to the prince. 4 Ye came to Bhujyu while he struggled in the flood, with flying birds, self-yoked, ye bore him to his sires. Ye went to the far-distant home, O Mighty Ones; and famed is your great aid to Divodisa given. 5 Asvins, the car which you had yoked for glorious show your own two voices urged directed to its goal. Then she who came for friendship, Maid of noble birth, elected you as Husbands, you to be her Lords. 6 Rebha ye saved from tyranny; for Atri’s sake ye quenched with cold the fiery pit that compassed him. Ye made the cow of Sayu stream refreshing milk, and Vandana was holpen to extended life. 7 Doers of marvels, skilful workers, ye restored Vandana, like a car, worn out with length of days. From earth ye brought the sage to life in wondrous mode; be your great deeds done here for him who honours you. 8 Ye went to him who mourned in a far distant place, him who was left forlorn by treachery of his sire. Rich with the light ofheaven was then the help ye gave, and marvellous your succour when ye stood by him. 9 To you in praise of sweetness sang the honey-bee: Ausija calleth you in Soma’s rapturous joy. Ye drew unto yourselves the spirit of Dadhyanc, and then the horse’s head uttered his words to you. 10 A horse did ye provide for Pedu, excellent, white, O ye Asvins, conqueror of combatants, Invincible in war by arrows, seeking heaven worthy of fame, like Indra, vanquisher of men.

A reference to mAkshika in RV 1.119.9 is a pun on the word: mAkshika ‘fly’ mAkshika ‘pyrites’

To you, O Aswins, that fly betrayed the soma: RV 1.119.9

Alternative trans. RV 1.119.9: “The bee desirous of honey sang praise-song for you. Aushij in delight of Soma tells how Dadhichi, told you the secret of his mind after the head of his horse was cured.”

One interpretation is framed on Vedanta: “Chandogya Upanishad (III.i.1) begins teaching Madhu Vidya by stating – The Sun is verily honey to the Devas (Vasus, Rudras, Adityas, Maruts and

Sadhyas), the Heaven is like the cross-beam, the intermediate region is the beehive; and the rays are the sons. But, this vidya does not teach meditation on Devas but on Brahman who is also known by the names Devas are known; it is a Brahma-vidya.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madhu-vidya The interpretation used in this monograph is to treat the text at the material process level of processing soma as metallic mineral resource, evaluating the text as metaphorical renderings..

Makshika as pyrites are used in metalwork: “maakshikam (pyrites), digested hundred times with juice of plantain leaves, and then steeped for three days in oil, clarified butter and honey, and then heated strongly in a crucible yields its essence” (alchemical treatise: Rudrayamala Tantra, cited in P.Ray, History of Chemistry in Ancient and Medieval India, p.157).

Note the pun on the word, ma_ks.ika_ meaning both ‘bee’ and ‘pyrites or quartz’. ma_ks.ika_ are pyrites; hema ma_ks.ika_ and ta_ra ma_ks.ika_ denote gold and silver pyrites. Rasaratna Samuccaya 77,81, 89-90: ma_ks.ikam is born of mountains yielding gold… Almost all epithets attributed to Soma (such as amśu [śukram or bright, pure metallic ore protrusions analagous to shoots of a plant], golden, yellow, shining, resplendent, flowing, filtering: pavitram; crushing on stones; provenance of soma in mountainous terrain) can be explained by this metallurgical-allegorical identification. Even the reference to the seller from Mt. Mujavant who is paid and chased away after taking delivery of the ore product can be explained in the braahman.a days involving the secretive alchemical processes (agni-rahasya; somanala yantra); these practices continue into the Arthaśaastra days with an extraordinary role played by the Adhvaryu in a political nexus within the king’s domain.

If you are looking for gold and cannot tell the difference between the second photo, of pyrite on a gold nugget, then you will find lots of pyrite, but no gold. Pyrite is referred to as “Fools Gold”, since many a prospector brought home the shiny Iron Sulfate, and staked claims on their “gold ” deposit, which turned out to be pyrite. All that glitters is not gold.

Pyrite. Named in antiquity from the Greek “pyros” for “fire” because sparks flew from it when hit with another mineral or a metal. Pyrites are referred to akkinikkal ‘flint, pyrites’ (lit. agni stone) in Tamil. Mākshika has also the meaning of ‘madhu’ in Suśruta. It is also a honey-like mineral substance of pyrites in Mahabharata. A synonym for pyrites is: madhu dhātu (Skt.)

In the context of metallurgy, mākshikā is a technical term, referring to pyrites.

Item 3: Reference to Soma in the dual and plural

Griffith translation: RV 9.66.1-5: 1. For holy lore of every sort, flow onward thou whom all men love. A Friend to be besought by friends. 2 O’er all thou rulest with these Two which, Soma Pavamana, stand, Turned, as thy stations, hitherward. 3 Wise Soma Pavamana, thou encompassest on every side Thy stations as the seasons come. 4 Flow onward, generating food, for precious boons of every kind, A Friend for friends, to be our help. 5 Upon the lofty ridge of heaven thy bright rays with their essences, Soma, spread purifying power.

It is extraordinary that soma is referred to in dual, or plural (re-inforcing

the allegorical nature of the descriptions): “with those two forms” (RV

IX.66.2,3,5); “the forms (plural, not dual) that are thine” (RV IX.66.3); “the

shining rays spread a filter on the back of the heaven, O soma, with (thy) forms

(plural, not dual)” (RV IX.66.5); the dual reference is to the ore-form and the

purified/processed form.

सोमःसंस्था a principal source of wealth for the ancient state, brahma-somāraṇya (4th cent. BCE Kauṭilya’s ArthaŚāstra.2.2.2) produces State revenue.

Artha is the sustenance or livelihood of people. A sutra enunciated: dharmasya mUlam artham, the basis for discharge of one’s responsibility is wealth.

The sequential refrain of Canakya NIti is: sukhasya moolam dharmam. Dharmasya moolam artham Arthasya moolam rajyam. Rajyasya moolam indriya vijayam.

Kauṭilya expounds on the role of the State and training of the crown prince in Chapter I with statements such as: Without government, rises disorder as in the Matsya nyayamud bhavayati (proverb on law of fishes). In the absence of governance, the strong will swallow the weak. In the presence of governance, the weak resists the strong— ArthaŚāstra 1.4

The very second chapter devoted to artha starts with bhūmichidravidhāna focussing principally on wealth from forest areas. One such forest area which is a source of wealth – artha – for the state is (of uncultivable land) is brahma-somāraṇya (AŚ.2.2.2.), that is forest area assigned to Brahmans and ascetics. Brahmans and ascetics saw the Aranyakas, principal documents of the Vedic narratives, enquiries and life-activities.

It appears from the prominent role assigned to artha ‘wealth’ from brahma-somāraṇya (AŚ.2.2.2.) that Soma samsthA were major wealth-producing activities related to such forest areas: brahma-somāraṇya (AŚ.2.2.2.).

It appears that सोमःसंस्था particularly from brahma-somāraṇya — i.e. from uncultivated forest lands — were the principal sources of revenue of the State together with the land revenues collected from cultivable lands. This aspect of life in Ancient India is an area for further researches.

Division of land

bhūmichidravidhāna (AŚ.2.2) भूमि–च्छिद्र [p= 1331,2] land unfit for cultivation, Inscr. THE King shall make provision for pasture grounds on uncultivable tracts. Bráhmans shall be provided with forests for brahma-somāraṇya (should be translated as: forests assigned for Soma yaga, see below), for religious learning, and for the performance of penance, such forests being rendered safe from the dangers from animate or inanimate objects, and being named after the tribal name (gótra) of the Bráhmans resident therein. A forest as extensive as the above, provided with only one entrance rendered inaccessible by the construction of ditches all round, with plantations of delicious fruit trees, bushes, bowers, and thornless trees, with an expansive lake of water full of harmless animals, and with tigers (vyála), beasts of prey (márgáyuka), male and female elephants, young elephants, and bisons—all deprived …Manufactories to prepare commodities from forest produce shall also be set up. (2.2.2, pp.65, 66) https://archive.org/download/Arthasastra_English_Translation/Arthashastra_of_Chanakya_-_English.pdf Notes on brahma-somāraṇya (AŚ.2.2.2.)

For settlement of ascetics and BrAhmanas devoted to the study of the Vedas, two types of forests wre identified: tapovana and brahma-somAraNya (AS 2.2.2)

ब्रह्मा* रण्य [p= 740,3] n. ” holy forest ” , a grove in which the वेद is studied L. brahman ब्रह्मन् One conversant with sacred knowledge -अरण्यम् 1 a place of religious study (Apte) BrahmAraNya mahAtmya is the name of a work. Forest produce was dravyavana distinguished from hastivana which are animal sanctuaries. SamAharta. Dravyavana and brahmAraNya Protection against hindrances to such brahmAraNya had to be given priority by the State officials.

Within the boundary of the forest-area, Kupyādhyakṣa (Director, Forest Produce under the control of Samāhartā) was “to make arrangements, for the settlement of the foresters or forest-dwellers connected with the produce forests (aṭavīmśca dravyavanāpaśrayāh)- AŚ.2.2.5) and they were to preserve and protect forests from various hazards… Kālāyasa (iron), tāmra (copper), vṛtta (steel), kāmsa (bronze), sīsa (lead), trapu (tin), vaikṛntaka (mercury) and ārakūṭa (brass) are included in the group of base metals. These metals were intended for preparing ploughs, pestles, which provided livelihood (ājīva), and machines, weapons, etc. for protection of the city (purarakṣā) (AŚ. 2.17.17). It may be presumed that separate factories were established in forest zones for each class of production. In this context, Kauṭilya advises the Master of the Armoury (Āyudhāgārdhyakṣa) to be conversant with the raw, defence material in the forests and their qualities and to avoid any adulteration (AŚ.2.18.20)… In the capital there was a store–house for forest produce (kupyagrha), built under the supervision of the Director of Stores (Sannidhātā) (AŚ.2.5.1).” (Manubendu Banerjee, 2011, Kauilya’s Arthasastra on Forestry in: Sanskrit Vimarśah, pp. 121-132), pp.123,127,128) http://www.sanskrit.nic.in/svimarsha/V6/c9.pdf Director of mines (Ākarādhyakṣa) (AŚ. 2.12) controlled the production of ores from mines.

Kupyādhyakṣa was in charge of setting up factories in the forests for producing serviceable articles (AS 2.17.2). Chief Ordnance Officer (Āyudhāgārādhyakṣa) supervised the business based on various types of forest-produce in the factories (AŚ. 2.18.20). Such factories most of the weapons. Guards who protected the factories were dravyavanapāla.

brahma-somāraṇya was thus a source of wealth from सोमःसंस्था and also a source for production of metal implements brought into Āyudhāgāra (State Armoury). This possibility is indicated by the evidence for performance of a Soma Yaga in Binjor (ca. 2500 BCE). The evidence is a yajña kunda with an octagonal pillar, a signature pillar of a Soma Yaga, together with an Indus Script inscription.

I suggest that Soma processing is metaphor for a metalwork process using the annam or godhuma or caṣāla atop an octagonal Yupa in a yajña kunda as seen on Binjor Yupa which is octagonal. This annam is for the divinities and NOT for the mortals. Soma aka amsu is ancu ‘iron’ or ‘iron-electrum’ compound ores from Mt. Mujavant.

Soma, wealth

“Ich habe nicht den Eindruck, dass die Pflanze, welche einst den Vorvätern der vedischen Inder als die trefflichste galt, notwendig eins mit der gewesen sein muss, welche von ihren Naehkommen in indischen Landen zur Gewinnung ihres Göttertrankes gebraucht wurde.” (Hillebrandt, Alfred, 1891, Vedische Mythologie I: Soma und verwandte Goetter. Breslau: Koebner.)

Soma prayers are for acquiring wealth

*ancu– ‘iron’ in Tocharian (cognate Ved. amśu-) discussed by Georges-Jean Pinault (2006). The strategy is to aver that Ved. amśu- as a borrowed word from Tocharian had the cognate semantics ‘metal’, while *añcu- (Tocharian) meant ‘iron’. And, in the poetic metaphors which are abundant in Vedic copora, the characterisics of soma- as ‘metal’ processed in yajña, are elaborated by the kavi- ‘smiths’. (The key is in the proto-indic lexeme: kavi, semant. ‘smith, poet’. Cognate, kayanian, cf. Christensen, A.,1932, Les Kayanides. Det Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Sellskab, Hist.-Filos. Meddelelser XIX.2. Copenhagen). cf. S. Kalyanaraman, 2000, Rgvedic Soma as a metallurgical allegory; soma, electrum is deified. RV 1.116.12 I proclaim, leaders (of sacriifce), for the sake of acquiring wealth, that inimitable deed which you performed, as the thunder (announces) rain, when provided by you with the head of a horse. Dadhyan~c, the son of Atharvan, taught you the mystic science. [Legend: Vana Parva, Mahābhārata: gods, being oppressed by the Kālakeya asura-s, solicited from the sage Dadhica his bones, which he gave them, and from which Tvas.t.a fabricated the thunderbolt with which Indra slew Vr.tra and routed the asuras. The text: Indra, having taught the science called pravargya vidyā and madhu–vidyā to Dadhyan~c, threatened that he would cut off his head if ever he taught them to any one else; the Aśvins prevailed upon him, nevertheless, to teach them the prohibited knowledge, and, to evade Indra’s threat, took off the head of the sage, replacing it by that of a horse; Indra, apprised of Dadhyan~c’s breach of faith, sturck off his equine head with the thunderbolt; on which, the Aśvins restored to him his own. The pravargya vidyā is said to imply certain verses of the r.k, yajur and sāma vedas, and the madhu-vidyā the BrāhmaNa].

RV 1.117.22 You replaced, Aśvins, with the head of a horse, (the head of) Dadhyan~c, the son of Atharvan, and, true to his promise, he revealed to you the mystic knowledge which he had learned from Tvas.t.a_, and which was as a ligature of the waist to you. [Tvas.t.a_ = Indra; the knowlege was kaks.yam. vām = a girdle to you both; strengthening them to perform religious rites].

RV 1.119.09 That honey-seeking bee also murmured your praise; the son of Usij invokes you to the exhilaratin of Soma; you conciliated the mind of Dadhyan~c, so that, provided with the head of a horse, he taught you (the mystic science).

Alternative trans.: To you, O Aswins, that fly betrayed the soma… maakshika = pyrite ores; fly. cf. “maakshikam (pyrites), digested hundred times with juice of plantain leaves, and then steeped for three days in oil, clarified butter and honey, and then heated strongly in a crucible yields its essence” (alchemical treatise: Rudrayamala Tantra, cited in P.Ray, History of Chemistry in Ancient and Medieval India, p.157).

RV 1.119.10 Aśvins, you gave to Pedu the white (horse) desired by many, the breaker-through of combatants, shining, unconquerable by foes in battle, fit for every work; like Indra, the conquerer of men.

Valmiki refers to Garuda smashing the iron-grid guard (ayah jaalaani).

Meaning of the word, amśu used by Valmiki

prasrutaH sarva gaatrebhyaH svedaH shoka agni sambhavaH |

yathaa suurya amshu samtaptaH himavaan prasrutaH himam || 2-85-18

Perspiration born of fieriness of grief poured off from all his limbs, as the snow heated by solar rays melts and flows from Himavat mountain

dhyaana nirdara shailena vinihshvasita dhaatunaa |

dainya paadapa samghena shoka aayaasa adhishR^ingiNaa || 2-85-19

pramoha ananta sattvena samtaapa oSadhi veNunaa |

aakraantaH duhkha shailena mahataa kaikayii sutaH || 2-85-20

Bharata, the son of Kaikeyi was pressed by the weight of that colossal mountain of agony consisting of rocky caverns in the shape of settled contemplations on Rama, minerals in the shape of groans and sighs, a cluster of trees in the shape of depressive thoughts, summits in the form of sufferings and fatigue, countless wild beasts in the shape of swoons, herbs and bamboos in the form of his exertions.

The semantic component of ‘clothing or cover’ and Marathi compound: अंशुजाल [aṃśujāla] is consistent with the garuḍa narrative of breaking the ayah jālāni ‘iron-grid or iron-net’ shield of a metamorphic mineral compound, to get to the ambrosia, amṛtam — soma.