Every few months or years, in the recent past, different groups of "scientists" announce the "results" of some "new genetic/genomic study" which "proves" the old colonial theory of an Aryan invasion of India. It is often cloaked in ambiguous terms, but not ambiguous enough for its target audience (political and academic groups committed to the theory that India was invaded by a race of people, popularly known as "Aryans", who brought the Indo-European languages into India) not to get the message and the ammunition. Certainly the present study ("The genomic formation of South and Central Asia", co-directed by Dr David Reich and an "international team of geneticists") is correctlyregarded, by the writers who are tomtoming it as a final answer to the "Aryan" question in India, as ablatant statement in support of the AIT or Aryan Invasion (of India) Theory: an article in theEconomist, Delhi, on 5/8/2018, has the following triumphalist title: "Steppe sons: A new study squelches a treasured theory about Indians' origins - The Aryans did not come from India, they conquered it".

This article goes on to point out that the discovery of the relationship between the languages of northern India and Europe, and the resultant theory that the "Aryan" (Indo-European) languages of northern India were brought into India from outside, led to two kinds of reaction in India: one, "Caste-bound Hindu conservatives declared that the paler-skinned intruders must be ancestors of higher-caste Brahmins and Kshatriyas. Such talk stirred a backlash in southern India, where generally darker-skinned speakers of Dravidian languages were urged to see themselves as a separate nation." And two: "Hindu nationalists took a different tack. The West, some said, had made up the theory to set Hindus against each other. Christian missionaries and communists were using it to stoke caste hatred and so to recruit followers, they claimed. Worse, the theory challenged an emerging vision of Mother India as a sacred Hindu homeland. If the first speakers of Sanskrit and the creators of the Vedas had themselves been intruders, it was harder to portray later Muslim and Christian invaders as violators of a purity that good Hindus should seek to restore. So it was that some proposed an alternative “Out of India” theory. This held that the original Aryans were in fact Indians, who carried their Indo-European language and superior civilisation to the West."

The writer blatantly positions himself on the first side: on the side of the "higher caste Brahmins and Kshatriyas" who like to believe that the white European colonialists "must be [their] ancestors" (even today there are coteries of casteist-racist Brahmins who have this attitude towards a theory which separates them from the "lower castes"), and on the side of the communities (caste-based, regional, linguistic) who have learned to portray themselves, actively and violently, "as a separate nation" within India.

And equally blatantly on the side opposed to the side which treats "Mother India as a sacred Hindu homeland": never mind that this opposition is on the basis of a hypothetical "invasion" or "migration" event, unrecorded in any text or tradition, alleged to have taken place around 4000 to 3500 years ago (long before even a single one of the cultures, civilizations and religions prevalent in every corner of the earth today were even born or conceived), which is treated as being on par with invasions in the last thousand years or so (but which in fact are actually denied!) which are recorded in detail and of which the foreign connections are still proudly held aloft! The title, moreover blatantly abandons the cautious conversion by modern historians of the "Aryan invasion" into an "Aryan immigration", and proclaims: "The Aryans did not come from India, they conquered it".

Most important of all, the whole tone and tenor of the article (which actually reflects, only more blatantly and openly, the tone and tenor of the "new scientific study" on which it claims to be based) isnot of someone referring in passing to some crank fringe "“Out of India” theory": the tone and tenor is of someone reporting the chinks or fallacies in an established theory! We will see presently why this is so.

To come to the actual "new study" which has led to this sharp spate in triumphalist articles and social media campaigns (even a second cousin of mine, with whom I have not been in contact for many years, specially phoned me ostensibly to offer condolences on the demise of the OIT or Out of India Theory of Indo-European origins, carefully and firmly avoiding listening to what I could have to say on the matter!), the tone and tenor of the study is no less blatant in its political aims: to begin with, the title itself "The genomic formation of South and Central Asia". The following is the official abstract of the paper:

"The genetic formation of Central and South Asian populations has been unclear because of an absence of ancient DNA. To address this gap, we generated genome-wide data from 362 ancient individuals, including the first from eastern Iran, Turan (Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan), Bronze Age Kazakhstan, and South Asia. Our data reveal a complex set of genetic sources that ultimately combined to form the ancestry of South Asians today. We document a southward spread of genetic ancestry from the Eurasian Steppe, correlating with the archaeologically known expansion of pastoralist sites from the Steppe to Turan in the Middle Bronze Age (2300-1500 BCE). These Steppe communities mixed genetically with peoples of the Bactria Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) whom they encountered in Turan (primarily descendants of earlier agriculturalists of Iran), but there is no evidence that the main BMAC population contributed genetically to later South Asians. Instead, Steppe communities integrated farther south throughout the 2nd millennium BCE, and we show that they mixed with a more southern population that we document at multiple sites as outlier individuals exhibiting a distinctive mixture of ancestry related to Iranian agriculturalists and South Asian hunter-gathers. We call this group Indus Periphery because they were found at sites in cultural contact with the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) and along its northern fringe, and also because they were genetically similar to post-IVC groups in the Swat Valley of Pakistan. By co-analyzing ancient DNA and genomic data from diverse present-day South Asians, we show that Indus Periphery-related people are the single most important source of ancestry in South Asia — consistent with the idea that the Indus Periphery individuals are providing us with the first direct look at the ancestry of peoples of the IVC — and we develop a model for the formation of present-day South Asians in terms of the temporally and geographically proximate sources of Indus Periphery-related, Steppe, and local South Asian hunter-gatherer-related ancestry. Our results show how ancestry from the Steppe genetically linked Europe and South Asia in the Bronze Age, and identifies the populations that almost certainly were responsible for spreading Indo-European languages across much of Eurasia."

The very concept of an "Aryan" people - even as an entity, let alone as an invading race from outside India - arose from the revolutionary discovery by colonial scholars that Sanskrit and the languages of northern India and the languages of Europe, Iran and Central Asia, are related to each other as a "language family" which has been given the name Indo-European (formerly also "Aryan"). This language family has twelve branches: Italic, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Albanian, Greek,Armenian, Iranian and Indo-Aryan, and the extinct Hittite (Anatolian) and Tocharian. There are five other (non-Indo-European) language families spoken in India: Dravidian, Austric, Sino-Tibetan,Andamanese, Burushaski. Likewise there are two other non-Indo-European language families in Europe: Basque and Finno-Ugric. And three more between India and Europe: Uralo-Altaic(actually, the Finno-Ugric already referred to are a branch of this family), Caucasian and Semito-Hamitic. All this called for an explanation as to how the Indo-European languages are spread out over such a large geographical area, covering "racially" and culturally extremely diverse people: where did these languages originate? Which was the original area from which the twelve branches of Indo-European languages spread out to cover their earliest known historical areas?

This was a question which arose solely from a linguistic fact (the linguistic relationship between all these languages), and three fields or disciplines of academic study have been involved for over two centuries in the elucidation of this problem: linguistics, archaeology and textual/inscriptional data(mainly the Rigveda and the oldest recorded Indo-European language inscriptions and documents from West Asia). The latest entrant in this field is genetics/genomics.

The latest paper on the genetic/genomic evidence which has enthused AIT supporters and activists seems to echo and substantiate with military precision the exact points enunciated by the AIT scholars and activists since two centuries, especially on the chronological angle. It shows an "expansion of pastoralist[s …] from the Steppe to Turan in the Middle Bronze Age (2300-1500 BCE)" and the subsequent part of this story where the "Steppe communities integrated farther south throughout the 2nd millennium BCE" leading to "the formation of present-day South Asians": these were "the populations that almost certainly were responsible for spreading Indo-European languages across much of Eurasia."!

This genetic evidence can be examined as follows:

I. Why the Date of the Rigveda is Crucial to the Whole Debate.

II. The Archaeological Evidence.

III. The Textual/Inscriptional Evidence for the Date of the Rigveda.

IV. The New "Genomic" Thesis.

I. Why the Date of the Rigveda is Crucial to the Whole Debate

The key to all AIT/OIT hypotheses is the date of the Rigveda.

This is because:

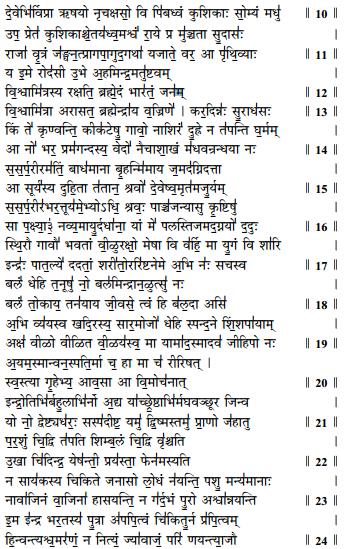

1.The Rigveda is the oldest recorded major text in any Indo-European language. As Griffith puts it in the preface to the first edition of his translation of the Rigveda: “The great interest of the Ṛgveda is, in fact, historical rather than poetical. As in its original language we see the roots and shoots of the languages of Greek and Latin, of Kelt, Teuton and Slavonian, so the deities, the myths, and the religious beliefs and practices of the Veda throw a flood of light upon the religions of all European countries before the introduction of Christianity.”

2. It shows absolutely no extra-territorial memories and shows ancestral attachment to the geographical area extending from Haryana to southern Afghanistan, and particularly and originally to the Haryana area in the east.

3. It does not refer to any "non-Indo-European" entities at all: i.e. to entities anywhere in the vicinity which can be identified linguistically as Dravidian, Austric or anything else "non-Aryan", let alone to non-Indo-European people who lived in these areas before them and were invaded and conquered by them.

4. Even the rivers and animals in this area have purely Indo-Aryan (Indo-European) Sanskrit names: as Witzel puts it, “in northern India rivers in general have early Sanskrit names from the Vedic period, and names derived from the daughter languages of Sanskrit later on […] This is especially surprising in the area once occupied by the Indus Civilisation where one would have expected the survival of older names, as has been the case in Europe and the Near East. At the least, one would expect a palimpsest, as found in New England with the name of the state of Massachussetts next to the Charles river, formerly called the Massachussetts river, and such new adaptations as Stony Brook, Muddy Creek, Red River, etc., next to the adaptations of Indian names such as the Mississippi and the Missouri”.” (WITZEL 1995a:105-107). This contrasts for example, sharply with Europe: "In Europe, river names were found to reflect the languages spoken before the influx of Indo-European speaking populations. They are thus older than c. 4500-2500 B.C. (depending on the date of the spread of Indo-European languages in various parts of Europe).” (WITZEL 1995a:104-105).

So what is the date of the Rigveda? The scholars are compelled to calibrate the date of the Rigveda between two known dates:

a) The linguistically determined date of 3000 BCE, which was the date when all the twelve Indo-European branches were together in their Original Homeland (which was assumed to be South Russia) and only started separating away from each other around that point of time.

b) The Buddhist period in Bihar from around 600 BCE, when it is definitely recorded that the whole of northern India was covered mainly by speakers of Indo-Aryan languages, and which definitely followed the periods of composition not only of the Rigveda but also of the three other Vedic Samhitas, the Brahmanas, Aranyakas, Upanishads and Sutras.

Therefore it is vital and mandatory, in fact a life-and-death requirement for the AIT, to date the Rigveda to a date calibrated between 3000 BCE and 600 BCE, ideally to a date around and after 1500 BCE.

Calibrating the date of the Rigveda by squeezing all the periods between these two dates, the scholars arrived at the following dates (echoed by the present scientists):

a) The "Indo-Iranians" migrated eastwards from the Steppes of South Russia around 3000 BCE.

b) They were settled in Central Asia or "Turan in the Middle Bronze Age (2300-1500 BCE)".

c) They moved southwards "throughout the 2nd millennium BCE", finally reaching the area described in the Rigveda, settling there, forgetting their entire past, and finally composing the text of the Rigveda.

The Rigveda is thus dated, by both the traditionalist AIT scholars, as well as by these new "genomic" scientists, to a period 1500-1000 BCE. Both these theses therefore stand or fall on the correctness of this date.

This date is absolutely mandatory for the AIT. If the Rigveda, for example, is accepted or proved to be going, even in its earliest parts, beyond 2500 BCE or even 2000 BCE, the entire AIT structure collapses like a pack of cards. It is impossible to bring the Indo-Aryans from the Steppes of South Russia all the way into the Rigvedic area of Haryana-S.Afghanistan (with complete loss of memory of the invasion/migration, with complete absence of any trace of non-Indo-European languages or people in the area, with Indo-Aryan names for the local rivers, etc.) within that microscopic period.

Hence we will first examine the textual and archaeological evidence for the date of the Rigveda. The linguistic evidence is so massive and uni-directional (all the evidence confirms the OIT, and not a single piece of evidence supports the AIT) that it will require a big article on its own (although all the evidence has already been given by me at various places in my books and other blog articles) - and in any case it cannot tell us much about the exact date of the Rigveda.

Then, we will look at the totally irrelevant (to the AIT/OIT debate) genetic/genomic data.

II. The Archaeological Evidence

Archaeology completely disproves the idea of any Indo-European movement into India around 1500 BCE:

1. To begin with, absolutely no archaeological evidence has been found of the Proto-Indo-European language spoken in Russia before 3000 BCE, or of the Indo-Iranian speakers moving from South Russia to Central Asia between 3000-2000 BCE, or of the Indo-Aryan speakers moving from Central Asia to the Punjab around 1500 BCE, or even of the Vedic Indo-Aryans moving from the Punjab into the rest of northern India after 1000 BCE. Even Michael Witzel, who is spearheading the AIT battalions, admits that archaeology offers no proof of the AIT: "None of the archaeologically identified post-Harappan cultures so far found, from Cemetery H, Sarai Kala III, the early Gandhara and Gomal Grave Cultures, does make a good fit for the culture of the speakers of Vedic […] At the present moment, we can only state that linguistic and textual studies confirm the presence of an outside, Indo-Aryan speaking element, whose language and spiritual culture has definitely been introduced, along with the horse and the spoked wheel chariot, via the BMAC area into northwestern South Asia. However, much of present-day Archaeology denies that. To put it in the words of Shaffer (1999:245) ‘A diffusion or migration of a culturally complex ‘Indo-Aryan’ people into South Asia is not described by the archaeological record’[…] [But] the importation of their spiritual and material culture must be explained. So far, clear archaeological evidence has just not been found" (WITZEL 2000a:§15).

2. In fact, archaeologists are almost unanimous on the point that there is absolutely no archaeological evidence for any change in the ethnic composition and the material culture in the Harappan areas between "the 5th/4th and […] the 1st millennium B.C.", and that there was "indigenous development of South Asian civilization from the Neolithic onward"; and further that any change which took place before "the 5th/4th […] millennium B.C." and after "the 1stmillennium B.C." is "too early and too late to have any connection with ‘Aryans’".

3. The archaeological consensus against the AIT is so strong that in an academic volume of papers devoted to the subject by western academicians, George Erdosy, in his preface to the volume, stresses that this is a subject of dispute between linguists and archaeologists, and that the idea of an Aryan invasion of India in the second millennium BCE "has recently been challenged by archaeologists, who ― along with linguists ― are best qualified to evaluate its validity. Lack of convincing material (or osteological) traces left behind by the incoming Indo-Aryan speakers, the possibility of explaining cultural change without reference to external factors and ― above all ― an altered world-view (Shaffer 1984) have all contributed to a questioning of assumptions long taken for granted and buttressed by the accumulated weight of two centuries of scholarship" (ERDOSY 1995:x). Of the papers presented by archaeologists in the volume (being papers presented at a conference on Archaeological and Linguistic approaches to Ethnicity in Ancient South Asia, held in Toronto from 4-6/10/1991), the paper by K.A.R. Kennedy concludes that "while discontinuities in physical types have certainly been found in South Asia, they are dated to the 5th/4th, and to the 1st millennium B.C. respectively, too early and too late to have any connection with ‘Aryans’" (ERDOSY 1995:xii); the paper by J. Shaffer and D. Lichtenstein stresses on "the indigenous development of South Asian civilization from the Neolithic onward" (ERDOSY 1995:xiii); and the paper by J.M. Kenoyer stresses that "the cultural history of South Asia in the 2nd millennium B.C. may be explained without reference to external agents" (ERDOSY 1995:xiv). Erdosy points out that the perspective offered by archaeology, "that of material culture […] is in direct conflict with the findings of the other discipline claiming a key to the solution of the ‘Aryan Problem’, linguistics" (ERDOSY 1995:xi).

On the other hand, there is conclusive archaeological evidence for the arrival of the European branches (the Italic, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic and Slavic branches) into Europe from the east, for the arrival of the Hittites (the Anatolian branch) into Turkey (Anatolia) from the northeast, for the arrival of the Greeks and Albanians (the Greek and Albanian branches) into Greece from the east(across the Aegean Sea), and for the arrival of the Tocharian branch into the Qinjiang province of China from Central Asia to its south. [The arrival of the Iranian branch into Iran from the east is recorded in Babylonian texts. The Armenian branch is also clearly an intruder into Armenia, as evident from the evidence of the place names in Armenia]. It is only the theoretically postulatedarrival of the Indo-Aryan branch (as represented by its oldest form, Vedic) into northwestern India from further northwest which is absolutely unsupported by any archaeological evidence.

III. The Textual/Inscriptional Evidence for the Date of the Rigveda

The exact copious details of the data for dating the Rigveda have been given in my books and other blogs. I will only give the essential points here:

1. The Divisions of the Rigveda: As per the consensus among all the Indologists, the ten Books or Maṇḍalas of the Rigveda can be divided into two groups:

a) The earlier Family Books: Books 2-7.

b) The later non-Family Books: 1,8-10.

Further, on the basis of a large range of criteria, one of the Family Books, Book 5, is later than the other four Family Books. Thus, we get two chronological groups of Books:

a) The Old Books: Books 2-4,6-7.

b) The New Books: Books 1,5,8-10.

2. The external sources for comparison of data with the Rigvedic data: There are two external sources for comparison of common or related data with the Rigvedic data:

a) The Iranian Avesta.

b) The Mitanni data.

The Mitanni data is particularly significant because:

a) It is specifically "Indo-Aryan" or "Vedic" data.

b) It is scientifically dated data found in the scientifically dated inscriptions and documents about the Mitanni kingdom and kings of Iraq and Syria, in the historically well-attested records of Egypt and West Asia.

3. Conventional Interpretation of the common data as per the AIT: The conventional theory is that:

a) The Indo-Aryan and Iranian branches jointly migrated eastwards from the Steppes of South Russia to Central Asia over a period of time.

b) The Indo-Aryans and Iranians separated from each other after a common sojourn in Central Asia:

The Vedic Indo-Aryans (who were to compose the Rigveda) migrated southeastwards into the Greater Punjab region (Saptasindhava or northern Pakistan).

The Iranians (who were to compose the Avesta) migrated southwards into Afghanistan.

The Mitanni Indo-Aryans (whose data is found recorded in the dated documents of Iraq, Syria and West Asia in general) migrated southwestwards towards West Asia.

c) The common linguistic-cultural elements found in the Rigveda, the Avesta, and the Mitanni records, are pre-Rigvedic elements of the common culture developed jointly by these three peoples during their common sojourn in Central Asia.

4. Actual Facts Emerging from the common data: An actual examination of the common data shows that the common elements are not elements of a common pre-Rigvedic culture, but elements of a common culture developed during the period of the New Books of the Rigveda. These elements are completely missing in all the Old Hymns and verses in the Old Books of the Rigveda (though found occasionally in a handful of occurences in certain hymns which the Indological scholars themselves have classified as late, interpolated or redacted hymns in the Old Books), but found in overwhelming numbers in the New Books of the Rigveda, in all the post-Rigvedic Vedic literature, and in all the post-Vedic Sanskrit literature. These elements are also central to the Avesta and the Mitanni data.

The distribution of these common elements in the Rigveda is as follows:

TOTAL HYMNS AND VERSES:

1. Old Hymns in Books 2,3,4,6,7: 280 Hymns, 2351 verses.

2. New Hymns in Books 1,5,8,9,10: 686 Hymns, 7311 verses.

COMMON RIGVEDIC-AVESTAN-MITANNI NAME TYPES IN COMPOSER NAMES:

1. Old Hymns in Books 2,3,4,6,7: 0 Hymns, 0 verses.

2. New Hymns in Books 1,5,8,9,10: 309 Hymns, 3389 verses.

COMMON RIGVEDIC-AVESTAN-MITANNI NAME TYPES AND WORDS WITHIN THE HYMNS:

1. Old Hymns in Books 2,3,4,6,7: 0 Hymns, 0 verses.

2. New Hymns in Books 1,5,8,9,10: 225 Hymns, 434 verses.

COMMON RIGVEDIC-AVESTAN NEW DIMETRIC METERS:

1. Old Hymns in Books 2,3,4,6,7: 0 Hymns, 0 verses.

2. New Hymns in Books 1,5,8,9,10: 50 Hymns, 255 verses.

This is not arbitrary data: it is absolute data. It proves that the three peoples separated from each other not in some pre-Rigvedic period but during the period of composition of the New Books of the Rigveda, when these new cultural elements developed, and therefore that they were all three of them together with each other during the composition of the Old Books, within the geographical area of the Rigveda.

The geographical area of the Rigveda as a whole stretches from Haryana-western U.P (Ganga) in the east to southeastern Afghanistan in the west. This therefore is the area from where the ancestors of the Mitanni kings and the composers of the Avesta migrated to their historical areas, taking these common cultural elements with them.

5. The Date of the Rigveda: The Mitanni data is found in securely dated records in West Asia, and can be exactly dated: the Mitanni kingdom flourished from around 1500 BCE onwards, and the Mitanni (and a related people, the Kassites) are found in West Asian records from around 1750 BCE. Moreover, they were already so long settled in West Asia that they had even adopted the local Hurrian language, while still retaining what the scholars refer to as "remnants" and "residual elements" of their ancestral Indo-Aryan heritage.

Going backwards from the Mitanni data:

a) The Mitanni must have arrived in West Asia at least a few hundred years before their recorded presence. At any rate, even if one assumes they had stepped into West Asia on the very day their presence was first recorded, they must still have left their ancestral area where they developed the common cultural elements (Haryana to southeastern Afghanistan) before 2000 BCE at the very minimum.

b) This means that the culture depicted in the New Books of the Rigveda was flourishing in this area (Haryana to southeastern Afghanistan) before 2000 BCE at the very minimum. It was already a fully developed culture by that time, hence we find it among the Mitanni.

c) This means that the beginnings of the fully developed culture of the New Books go back far beyond 2000 BCE, and the totally different culture of the Old Books goes even further back. I take the date of the beginning of composition of the Old Books and their hinter-period beyond 3000 BCE. How far can someone wanting to squeeze the date to as late a point of time as possible go: did the date of composition of the New Books start in 2000 BCE, and the date of composition of the Old Books with their totally different culture in 2010 BCE?

It must be noted that it is impossible to ignore all this recorded data and claim that the Vedic Indo-Aryans entered India after 1500 BCE.

In short, the culture found as the fading "remnants" of an ancestral culture among the Mitanni people in Syria-Iraq from at least 1750 BCE (as per scientifically dated records) is a culture which developed during the period of composition of the five New Books of the Rigveda, and is completely missing in the five Old Books.

Note: This dating is further confirmed by the references in the Rigveda to certain technological innovations which took place in the second half of the third millennium BCE, which are likewisecompletely absent in the Old Books:

Spoked wheels were invented (supposedly somewhere around Central Asia) in the second half of the third millennium BCE. Likewise, the “Bactrian camel was domesticated in Central Asia in the late 3rd mill. BCE” (Witzel). The following is the distribution of references to camels and to spokesin the Rigveda, all exclusively in the New Books:

V.13.6; 58.5.

I.32.15; 141.9; 138.2; 164.11,12,13,48.

VIII.5.37; 6.48; 20.14; 46.22,31; 77.3.

X.78.4.

6. The Geography of the Old Books: And what is the geography of the Old Books of the Rigveda in the period definitely long before 2000 BCE (and actually as far back as 3000 BCE)? Does it show that the culture of the Old Books (ancestral to the culture of the New Books, the Avesta and the Mitanni) was located somewhere between the Steppes and Central Asia, or at least in Central Asia?

On the contrary, the geographical data of the Old Books is restricted to the area to the east of the Sarasvati river in Haryana (for more precise details see my books and other blogs):

a) The places, lake and animals of the East (east of the Sarasvatī, in Haryana and further east) are found in all the Books, both the Old Books and the New Books:

Old Books (25 hymns, 28 verses, 31 names):

VI.(5 hymns, 5 verses and names).

III. (7 hymns, 9 verses, 12 names).

VII. (4 hymns, 4 verses and names).

IV. (5 hymns, 5 verses and names).

II. (4 hymns, 5 verses and names).

New Books (63 hymns, 73 verses, 77 names) :

V. (6 hymns, 7 verses and names).

I. (16 hymns, 19 verses, 22 names).

VIII. (9 hymns, 11 verses and names).

IX. (14 hymns, 17 verses and names).

X. (18 hymns, 19 verses, 20 references).

But the places, lakes, mountains and animals of the West (west of the Indus, in southern and eastern Afghanistan) are completely missing in the Old Hymns in the Old Books and are found only in the New Hymns in the New Books. In fact they are missing even in the New Family Book 5:

Old Hymns in the Old Books (0 hymns, 0 verses and names).

New Hymns in the New Books (57 hymns, 72 verses, 73 names):

I. (18 hymns, 21 verses and names).

VIII. (13 hymns, 17 verses, 18 names).

IX. (8 hymns, 12 verses and names).

X. (18 hymns, 22 verses and names).

b) The place names of the Rigveda, further show an east to west expansion from the Old Books to the New Books:

The river names of the Rigveda, likewise, also show this east to west expansion:

In short, the Old Books were composed in the East, well to the east of the Sarasvati, and far from Central Asia, which only entered the geographical horizon of the Rigveda in the New Books.

The evidence of the Rigvedic data shows that long before 2000 BCE, in the period of the Old Books, the Vedic Aryans were originally located in the areas of Haryana and further east. The east-to-west expansion shown by the above data-graphs is actually described in the historical narrative in the Rigveda: the activities of the ancestors of Sudās (in order of lineage: Bharata, Devavāta, Sṛñjaya, Divodāsa) are all located in Haryana. The expansion in the period of Sudas (following his own earlier activities in Haryana) shows him first crossing the two easternmost rivers of the Punjab westwards with his army. Then he fights an alliance of ten western tribes on the banks of the third river, and his enemies are described as fighting from the region of the fourth river. Later, in the period of his descendants Sahadeva and Somaka, the Vedic Aryans expand as far west as beyond the Indus.

Note: it is in this period, long before 2000 BCE, that we find the Vedic Aryans originally not even familiar with the northwestern parts of India into which they were yet to expand, let alone with Central Asia or areas further west. They do not refer to any linguistically non-Indo-European entitiesanywhere in their vicinity. And the local rivers all have Indo-Aryan/Indo-European names.

In the face of this overwhelming evidence that the oldest parts of the Rigveda hark back to a periodlong before 2000 BCE (actually even going as far back as 3000 BCE), and that the Vedic beginnings were in Haryana in the east, what is the value of these "genomic" claims by "scientists" who speak of"the populations that almost certainly were responsible for spreading Indo-European languages across much of Eurasia" moving southwards from an earlier habitat in Central Asia and first entering India during "the 2nd millennium BCE"?

Can genomists prove in the face of all the recorded historical evidence to the contrary, on the basis of "scientific genomic evidence", that Columbus discovered America in the 4th century BCE or alternately in the nineteenth century CE, and that the Europeans started colonizing the Americas at that point of time? What would be the value of such "genomic" claims which fly in the face of recorded history? Would anyone take them seriously, let alone treat them as invalidating the presently accepted ideas about the date of the colonization of the Americas by Europeans?

Further, it is also being claimed that the "genomic" Revelations have "confirmed" the linguistic and textual interpretations of the Indologists and AIT protagonist scholars. A leftist writer Prabir Purkayastha in an article on a site "newsclick.in" on 9/4/2018 writes: "For the historians there should be a sigh of relief. The painstaking work that they have done with archaeological and textual evidence is very close to the new genetic evidence"! But we have already seen above what the archaeologists have to say about the AIT, and what the textual evidence shows!

The fact is that the extremely lop-sided and faulty linguistic and textual interpretations of the Indologists and AIT protagonist scholars have already been completely overturned and disproved by newer and more complete analyses: by in fact the linguistic and textual analysis presented in my books (and blogs). So much so that the AIT scholars have now fully conceded defeat in the fields oflinguistics, archaeology and textual data analysis and have fled from the debate. Hence these desperate attempts by motivated "scientists" to completely abandon these three academic disciplines and shift the debate to the totally irrelevant (to the AIT/OIT debate) field of "genomics". After Copernicus announced his discovery that it was the earth which moved around the sun and not vice versa, there must have been many church "scientists" who made "discoveries" which confirmed the old Church view that it was the sun which moved around the earth, and thereby allowed the geocentric "scholars" to heave "a sigh of relief"! But that did not stop the ultimate vindication of Copernicus' discovery. The cowardly campaign by these "genomic" scientists to "confirm" old and completely discredited dates for the Rigveda can have no value so long as they studiously skulk away and avoid addressing the real evidence for the dating of Rigveda and the Vedic period, which completely shatters their "scientific" humbug.

IV. The New "Genomic" Thesis

The international consortium of "genomic scientists", committed to "confirming" and "proving" the discredited AIT (the team includes old suspects like Tony Joseph who has been conducting an active political campaign on this issue in the Indian media in the last few years, and this team has been at it for years trying to drum up a "genetic" case for the utterly discredited theory - a new case every time), claims that the Rigveda was composed by "Aryan" invaders who were part of an "expansion of pastoralist[s …] from the Steppe to Turan in the Middle Bronze Age (2300-1500 BCE)" and that these "Steppe communities integrated farther south throughout the 2nd millennium BCE" leading to "the formation of present-day South Asians". The very dates they claim - which are absolutely vital for them in order to fit in with the linguistic fact that the twelve branches of Indo-European languages were together in the Original Homeland till 3000 BCE as well as the well attested presence of established Indo-Aryan speakers all over northern India as far east as Bihar well before 600 BCE - prove their thesis to be completely impossible:

Let us examine the mind-bogglingly impossible scenario that the "scientists" postulate. According to them, the Indo-Aryans:

a) moved southwards from Turan (Central Asia) into the Punjab region "throughout the 2nd millennium BCE" (i.e. definitely well after 2000 BCE),

b) then moved through the area of the declining Harappan civilization without leaving even the faintest traces in the archaeological record - so much so that archaeologists strongly dispute this alleged invasion/migration in the second millennium BCE,

c) and yet affected such a complete transformation in the entire area (without leaving any memories of it among either the conquerors or the conquered) that even invasionist scholars are struck by it: "What is relatively rare is the adoption of complete systems of belief, mythology and language from neighbouring peoples […] Yet, in South Asia we are dealing precisely with the absorption of not only new languages but also of an entire complex of material and spiritual culture, ranging from chariotry and horsemanship to Indo-Iranian poetry whose complicated conventions are still actively used in the Ṛgveda. The old Indo-Iranian religion, centred on the opposition of Devas and Asuras, was also adopted, along with Indo-European systems of ancestor worship.” (WITZEL 1995a:112),

d) and, what is more, transformed even the names of the local rivers into Indo-Aryan ones, leaving not a trace of the original names - a situation absolutely unparalleled in world history, as we have already noted earlier: “in northern India rivers in general have early Sanskrit names from the Vedic period, and names derived from the daughter languages of Sanskrit later on […]This is especially surprising in the area once occupied by the Indus Civilisation where one would have expected the survival of older names, as has been the case in Europe and the Near East. At the least, one would expect a palimpsest, as found in New England with the name of the state of Massachussetts next to the Charles river, formerly called the Massachussetts river, and such new adaptations as Stony Brook, Muddy Creek, Red River, etc., next to the adaptations of Indian names such as the Mississippi and the Missouri” (WITZEL 1995a:105-107),

e) and then, moved eastwards across the Sarasvati into the area of Haryana and eastern Uttar Pradesh, and effected "an almost complete Indo-Aryanization in northern India" (WITZEL 1995a:106) to the extent that by the time they composed the Old Books of the Rigveda, not a trace was left in the area of any linguistically non-Indo-European (specifically Dravidian or Austric) entity, and they themselves had already completely forgotten their entire extra-territorial history and the western territories through which they moved eastwards,

f) after which they started expanding "back" westwards into the Punjab and southern Afghanistan (as recorded in the Rigveda), in the process developing the completely new culture of the New Books of the Rigveda: the proto-Iranians and proto-Mitanni were also with them during this historical process as shown by the common data,

f) then after this completely new culture of the New Books was fully crystallized, the proto-Mitanni migrated westwards from this area all the way into Iraq and Syria by 1750 BCE taking this culture with them, and established their historically attested and scientifically dated empire around 1500 BCE, by which time they, in turn, had completely forgotten their own migration history, had adopted the local Hurrian language, and were only left with Vedic elements that linguists describe as the "remnants" (WITZEL 2005:361) and "the residue of a dead language in Hurrian" of a "symbiosis that produced the Mitanni [which] may have taken place centuries earlier” (MALLORY 1989:42).

Will any sane person credit this above story, which tries to condense millennia of history and alleged historical changes within a century or less? Clearly one of the three key elements in this story are wrong:

1. Either the Mitanni date and data are wrong (but unfortunately for any possible claims of this kind, this is the only real and securely and scientifically dated material evidence in this whole debate).

2. Or the date of the Rigveda as proved by me to be going back to around 3000 BCE, and certainly long before 2000 BCE is wrong (but this evidence is so massive and unidirectional and final that no-one has the guts to take up the challenge to even try to examine and disprove it. It is a complete presentation of the data, and such data cannot be fabricated).

3. Or the "genomic" thesis of the "international team of scientists" is wrong. Well, unless the "genomic" scholars or their compatriots in the field of textual analysis can prove the above date of the Rigveda wrong by providing counter-data (which is impossible, since this data is the only data available), then the "international team of scientists" is pathetically and pitifully wrong.

One Example of the detailed records of the Indo-European migrations: Before evaluating the worth of this so-called "genomic" evidence in the "Aryan" debate, one more point must be noted: the migration of the Indo-European branches from the Indian Homeland is not a matter of pure conjecture concerning faceless and nameless groups of prehistoric people to be identified now only by the names of their (presently named) Indo-European branches: the migrations of the historical speakers of the other eleven branches from India is recorded in the Puranas and the Rigveda, and the whole history is corroborated by massive textual, linguistic and archaeological evidence, and nothing contradicts or disproves it. All this massive evidence is given in my books and blogs. Here I will give only one small piece of the evidence as a sample:

As per the established linguistic analysis, seven branches had migrated from the Homeland (wherever it was located) in the following order: Hittite (Anatolian), Tocharian, Italic, Celtic,Germanic, Baltic and Slavic. Finally only five branches were left in the Homeland: “After the dispersals of the early PIE dialects […] there were still those who remained […] Among them were the ancestors of the Greeks and Indo-Iranians […] also shared by Armenian; all these languages it seems, existed in an area of mutual interaction.” (WINN 1995:323-324). The five branches which share many linguistic features missing in the earlier seven are Albanian (not mentioned in the above quote), Greek, Armenian, Iranian and Indo-Aryan.

However, the data in the Rigveda regarding the dāśarājña battle and the expansionary activities of Sudās (Book 7), shows this area to be in the Punjab. Sudās, the Vedic (Indo-Aryan/Pūru) king enters the Punjab area from the east and fights this historical battle against a coalition of ten tribes (nine Anu tribes, and one tribe of the remnant Druhyu in the area), and later these tribes start migrating westwards.

The Anu tribes (or the epithets used for them) named in the battle hymns are:

VII.18.5 Śimyu.

VII.18.6 Bhṛgu.

VII.18.7 Paktha, Bhalāna, Alina, Śiva, Viṣāṇin.

VII.83.1 Parśu/Parśava, Pṛthu/Pārthava, Dāsa.

(Another Anu tribe in the Puranas and later tradition is the Madra).

These tribal names are primarily found only in two hymns, VII.18 and VII.83, of the Rigveda, which refer to the Anu tribes who fought against Sudās in the dāśarājña battle or "the Battle of the Ten Kings". But see where these same tribal names are found in later historical times (after their exodus westwards referred to in VII.5.3 and VII.6.3). Incredibly, they are found dotted over an almost continuous geographical belt, covering the five last branches (which, according to the linguistic analysis, remained in the Homeland before the last stage of migrations), and covering the entire sweep of areas extending westwards from the Punjab (the battleground of the dāśarājña battle) right up to southern and eastern Europe:

Afghanistan: (Avestan) Proto-Iranian: Sairima (Śimyu), Dahi (Dāsa).

NE Afghanistan: Proto-Iranian: Nuristani/Piśācin (Viṣāṇin).

Pakhtoonistan (NW Pakistan), South Afghanistan: Iranian: Pakhtoon/Pashtu (Paktha).

Baluchistan (SW Pakistan), SE Iran: Iranian: Bolan/Baluchi (Bhalāna).

NE Iran: Iranian: Parthian/Parthava (Pṛthu/Pārthava).

SW Iran: Iranian: Parsua/Persian (Parśu/Parśava).

NW Iran: Iranian: Madai/Mede (Madra).

Uzbekistan: Iranian: Khiva/Khwarezmian (Śiva).

W. Turkmenistan: Iranian: Dahae (Dāsa).

Ukraine, S, Russia: Iranian: Alan (Alina), Sarmatian (Śimyu).

Turkey: Thraco-Phrygian/Armenian: Phryge/Phrygian (Bhṛgu).

Romania, Bulgaria: Thraco-Phrygian/Armenian: Dacian (Dāsa).

Greece: Greek: Hellene (Alina).

Albania: Albanian: Sirmio (Śimyu).

The above named Iranian tribes are also the ancestors of almost all other prominent historical and modern Iranian groups not directly named above (check the encyclopedias and wikipedia on this point), such as the Scythians (Sakas), Ossetes and Kurds, and even the presently Slavic-language speaking (but formerly Iranian-language speaking) Serbs, Croats, Poles, Slovaks and Ukrainians!

The earlier migrations of the seven earlier branches are recorded in the Puranas, which describe the migrations of the Druhyu tribes who first migrated northwards into Central Asia:

"Indian tradition distinctly asserts that there was an Aila outflow of the Druhyus through the northwest into the countries beyond, where they founded various kingdoms" (PARGITER 1962:298).

"Five Purāṇas add that Pracetas’ descendants spread out into the mleccha countries to the north beyond India and founded kingdoms there" (BHARGAVA 1956/1971:99).

"After a time, being overpopulated, the Druhyus crossed the borders of India and founded many principalities in the Mleccha territories in the north, and probably carried the Aryan culture beyond the frontiers of India" (MAJUMDAR 1951/1996:283).

But now back to the "genomic evidence":

The very fact that the "genomic evidence" is being tailor-made to fit into the geography and chronology of the conventional AIT theory which dates the Rigveda to 1500-1200 BCE, when the scientifically dated Mitanni records prove that the culture of the New Books of the Rigveda, which the ancestors of the Mitanni kings brought into West Asia, had developed in the Haryana-S.Afghanistan area long before 2000 BCE, and that the older Old Books go back to at least 3000 BCE in Haryana, automatically and immediately debunks the contention that the "genomic evidence" has anything to do with the movement of the Indo-European languages.

But the fact is that languages have no direct connections with DNA, genes, genomes and haplogroups at all. Languages spread in ways which do not have anything to do with the spread of DNA and genetic features. For example:

a) The English language today is spoken by millions and millions of people all over the world: large numbers of Americans of native-American-Indian and African origin speak only English and do not know their original ancestral languages. In our own country it is one of the major languages of communication between different language speakers (this article is being written and read in English, for example), and likewise in other large parts of Asia and Africa: but would it be possible to be able to trace the history of the spread of the language by analyzing the DNA and genomes of all these different people?

b) The Sinhalese people to the south of India speak an Indo-European language which often contains Indo-European words of even more archaic vintage than the Vedic language (e.g. watura for "water"). But are the Sinhalese people genetically closer to Kashmiris, Maharashtrians and Assamese, or Iranians, Greeks and Scandinavians, than to their neighboring Dravidian-language Tamil speaking neighbors?

c) The Santali-Mundari people of east-central India speak Austric languages related to the Austric language of Vietnam (e.g. "one, three, four" in Santali is "mit, pa-ia, pon-ia" and in Vietnamese "mot, ba, bon"). Are the Vietnamese and the Santals genetically closer to each other than the Vietnamese are to their neighboring Sino-Tibetan language speaking Laotians and Burmese or the Santals are to their non-Austric neighbors?

At the most, after a piece of history is all cut and dried from more pertinent recorded historical sources, "DNA" evidence can be searched out which fits in with the proved and established historical narrative: such as for example that the American continent, already populated by native Americans, was colonized By Europeans in the last few centuries, and that large batches of Africans were also transported to the Americas by the Europeans, thus possibly leading to interesting studies on the genetic, genomic and DNA composition of the present day "Americans". However, although the present gang of "scientists" claim to have done just such studies which confirm earlier linguistic and textual studies on the "Aryan" presence in India, the fact is that they are fitting their jacket onto the wrong studies - studies which have been thoroughly disproved on the basis of newer and more detailed and comprehensive studies on the linguistic and textual data.

It must be noted that genetic studies are as scientific as they are believed to be when it pertains to tracing genetic lines. Human beings have been migrating from every conceivable area to every other conceivable area and in every possible direction since the dawn of history. Certain areas, indeed, like Central Asia, are seething hotbeds of ethnic to-and-fro migrations, and India has seen countless migrations and invasions in the last many thousand years: we have Scythians, Greeks, Kushanas, Hunas, Arabs, Turks, Afghans, Ethiopian slave-soldiers and Persians invading, we have other Persians and Syrian Christians taking refuge in India, and none of them retained their language, and all of them assimilated into the local populations and adopted the local languages, but their foreign genes remain in the genetic record. As almost all the invasions and migrations took place from the northwest into northern India (although coastal areas also have their high share of foreign interactions), naturally any foreign genes are more likely to be found in greater proportions in the north than in the south; and as invaders are more likely to mix with the elites in the conquered societies, these genes are more likely to be found among "upper"-castes or ruling classes than among the "lower"-castes or isolated jungle or hill tribes. That this phenomenon is being invested with linguistic "Aryan" connotations and caste implications is testimony to the motives behind the whole enterprise. Needless to say, the real or alleged genetic compositions of present day Indians belonging to different castes or regions is irrelevant to the linguistic question.

In short:

1. Racial movements allegedly traced on the basis of genomes and haplogroups cannot help us trace the history of the Indo-European language migrations.

2. The date of the earliest part of the Rigveda goes back to beyond 3000 BCE in a purely "Indo-Aryan" Haryana; and the later expansion of the geographical horizon of the Rigveda, to cover the area up to southernmost and easternmost Afghanistan in the west, not only identifies the Vedic people with the Harappans but also makes this area the PIE Homeland (since, as per the linguistic consequence, all the twelve Indo-European branches were together with each other in the PIE Homeland till around 3000 BCE). And the whole migration history of the other eleven branches from this Homeland is recorded history. All this makes any talk of "Indo-Aryans" invading northwestern India in 1500 BCE, and composing the Rigveda after that, purely a hallucination of these politically determined academicians.

But even if we were to assume for the sake of argument that (a) all this evidence should be completely ignored or blanked out, (b) that the "migration" of "genomic" features should be treated as the migration of languages, and (c) that the Rigveda should be religiously dated after 1500 BCE; even then, the "genomic evidence" should specifically identify certain specific haplogroups as "Indo-European", and should show on the basis of secure scientific evidence that:

1. These "Indo-European" haplogroups were found only in the Steppe area, and nowhere else, till around 3000 BCE.

2. They are found in chronologically clear trails from 3000 BCE onwards leading into Central Asia (two distinct trails for the linguistically distinct Tocharians and "Indo-Iranians" respectively), Europe (the Italic, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic and Slavic branches), southeastern Europe (the Albanians and Greeks, with the Armenians) and Anatolia (the Hittite/Anatolian branch) respectively in the "linguistically predicted" time frames.

3. The "Indo-Iranian" haplogroups, in particular, appear in Central Asia (through an identifiable trail of genomic specimens) only around 2000 BCE or so, and then appear in the area of the Indus area only in the period after 1500 BCE - being completely missing in that area before then.

But this is not the kind of "genomic" evidence being presented. The whole case is a kind of "trust us, we are scientists, and we know what happened"!

On the contrary:

a) The entire AIT, or caste history of India, is sought to be "confirmed" or "proved" on the basis of the very general (with various factors breezily clubbed together in conveniently selected contexts) DNA analysis of a few scattered individuals from the remote past, or stray selected specimens from selected castes.

b) All kinds of (sometimes actually mutually contradictory) conclusions are sought to be drawn from three individual specimens from Central Asia, which have been labeled as "Indus periphery".

c) There are actually no specimens from the actual Indus/Vedic area in the relevant period: the much-publicized and long-awaited DNA results of the almost 5000-year-old specimen from Rakhigarhi in Haryana are unfortunately yet to see the light of day.

d) Genetic data of modern specimens of people from India, which is known to be a kind of melting-pot of all the possible races of the world (there is a picturesque rhetorical quote to this effect from Swami Vivekananda, quoted by me in my second book, see TALAGERI 2000:401), are cited to show that "Aryans" invaded India in 1500 BCE.

Further, note the following statements in the "report" which really go against their basic thesis:

1. “…there is no evidence that the main BMAC population contributed genetically to later South Asians.”(Abstract).

“The absence in the BMAC cluster of the Steppe_EMBA ancestry that is ubiquitous in South Asia today—along with qpAdm analyses that rule out BMAC as a substantial source of ancestry in South Asia (Fig. 3A)—suggests that while the BMAC was affected by the same demographic forces that later impacted South Asia (the southward movement of Middle to Late Bronze Age Steppe pastoralists described in the next section), it was also bypassed by members of these groups who hardly mixed with BMAC people and instead mixed with peoples further south.”

“In fact, the data suggest that instead of the main BMAC population having a demographic impact on South Asia, there was a larger effect of gene flow in the reverse direction, as the main BMAC genetic cluster is slightly different from the preceding Turan populations in harboring ~5% of their ancestry from the AASI.”.

All the 4 samples from Shahr-i-Sokhta in Eastern Iran also show South Asian admixture. In other words, based on the evidence given in the paper, there was a very large genetic contribution of South Asia in both the BMAC as well as in the Helmand civilization of which Shahr-i-Sokhta is a principal site. In fact, in both the Bronze Age Eastern Iran and Central Asia, the principal cattle is the Zebu cattle which is Indian in origin and there are besides many other lines of evidence suggesting Indus civilization influence in both these regions.

2. “… samples from three sites from the southern and eastern end of the Steppe dated to 1600-1500 BCE (Dashti-kozy, Taldysay and Kyzlbulak) show evidence of significant admixture from Iranian agriculturalist-related populations, demonstrating northward gene flow from Turan into the Steppe…”.

An article in the Indian Express of 16/4/2018, "The Long Walk: Did the Aryans migrate into India? New genetics study adds to debate. Co-authored by 92 leading scientists, it offers new insights into makeup of the Indian population. Will it settle or again trigger the contentious debate?" by Sowmika Ashok and Adrija Roychowdhury quoting Tony Joseph, tells us: "Essentially, Joseph points out, the study shows that there are no “pure” people anywhere — except perhaps in some very isolated and remote places such as some of the Andaman and Nicobar islands. 'We are all mixed. Almost all parts of the world have seen repeated mass migrations that have deeply impacted their demography and India is no exception. The genetic studies should be liberating in a way because it should make us aware that we are all interconnected.'"

It also quotes David Reich, the scientist who heads this gang of politically-committed "scientists", as follows, in the context of a previous study: "The ANI are related to Europeans, central Asians, Near Easterners, and people of the Caucasus, but we made no claim about the location of their homeland or any migrations. The ASI descend from a population not related to any present-day populations outside India. We showed that the ANI and ASI had mixed dramatically in India. The result is that everyone in mainland India today is a mix, albeit in different proportions, of ancestry related to West Eurasians, and… more closely related to diverse East Asian and South Asian populations. No group in India can claim genetic purity.".

But all this is absolutely right. Certainly, no group in India can claim genetic purity: all people represent "a mix, albeit in different proportions, of ancestry related to West Eurasians, and… more closely related to diverse East Asian and South Asian populations" - ironically, the ideas of "genetic purity" lie in the hearts of those, both the casteist-racist Brahmin defenders of the AIT as well as the pseudo-dalit supporters of the AIT (note that Dr. Ambedkar had sharply rejected the AIT in his writings) who are among the most gleeful in support of these "new findings" - but this has nothing to do with the history of the Indo-European languages.

The Indian Express article also quotes Michel Danino: "ICHR member and guest professor at IIT Gandhinagar, Michel Danino, said that the study is 'steeped in circularity'. 'It accepts the Indo-European migrations into Europe and into South Asia as a fact, then repeatedly fits the genetic evidence to this ‘fact’. This is faulty methodology…,' he said. He pointed out that 'No ancient Harappan DNA has been analysed, which could have provided some secure comparison for contemporary samples in Central Asia and elsewhere.'

Danino also says that the study assumes that South Asia was more or less empty of population in the pre-Harappan era. 'It sweeps aside the subcontinent’s Mesolithic and Neolithic populations which undoubtedly have substantial contributions to the South Asian genome. It considers such Mesolithic and Neolithic populations only in the context of Central Asia and Europe! This is one example [among others] of a strong Eurocentric bias in the study,' he says.".

Actually, the most vital mistake which these committed scientists make is to accept as a "fact" the date of the Rigveda as post-1500 BCE (while ignoring the massive evidence which shows that it goes beyond 3000 BCE), and "then repeatedly fit the genetic evidence to this ‘fact’". The result is "garbage in garbage out" so far as the linguistic question is concerned, whatever the (dubious or still to be properly evaluated) value of the analysis to actual migrations of people and mixtures of populations.

The "genomic scientists" have only released preliminary trailers of what their "report" is going to "prove". The full report is yet to come. And it will be answered in full by the appropriate people. The only thing to note here is that objectivity and honesty cannot be expected from a group of people -whatever their academic status - calling themselves "scientists", but working for years to a definite political objective, and refusing to deal with the relevant evidence (in this case, the linguistic, archaeological and textual/inscriptional data), while proclaiming and propagating their motivated and flawed conclusions on a war footing.

What is worse is that, even as they ignore the latest linguistic, archaeological and textual/inscriptional data and evidence, their whole proof is based on the claim that the "genomic" dates derived by them actually "fit in" with the dates derived by linguists (but, note, strongly rejected by archaeologists) for the alleged "Aryan" migrations from the Steppes (and consequently with the date assigned by the linguists to the Rigveda)! This is like a group of committed Church "scientists" in the 1600s periodically announcing new "scientific" discoveries which fitted in with the Church-held geocentric view of the world, while refusing to consider or debate the contemporary works of Galileo Galilei which proved the heliocentric case. [Galileo was tried by the Roman Inquisition in 1633 for "heresy" and kept under house arrest till his death in 1642. One can imagine the power of the Church "scholars" in Europe in those days, and the clout of the works of their committed "scientists". But what would be the status of their "scientific" works today?].

In any case, however many new strands of different foreign DNA and genes are discovered to be embedded in the genetic structure of different sections of Indians, all this has nothing to do with the question of the "Aryan languages" in India, and of the Original Homeland and the migrations of the ancient Indo-European tribes, since all this has already been answered: the Original Homeland of the Indo-European languages was in northern India, and the migrations of the other eleven branches of Indo-European languages from India is a matter of recorded history.

[I owe my main inputs above on the "genetic evidence" to Nirjhar Mukhopadhyay and Jaydeep Rathod, and hereby express my thanks to them for the same].

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

BHARGAVA 1956/1971: India in the Vedic Age: A History of Aryan Expansion in India. Upper India Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. Lucknow, 1956.

ERDOSY 1995: Preface to “The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: language, material Culture and Ethnicity”, edited George Erdosy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin-NY, 1995.

GRIFFITH: The Hymns of the Rigveda - Translated with a popular commentary. Griffith, Ralph T.H. (first publ.) E.J Lazarus and Co., Benares, 1889.

MAJUMDAR ed.1951/1996: The Vedic Age. General Editor Majumdar R.C. The History and Culture of the Indian People. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. Mumbai, 1951.

MALLORY 1989: In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth. Mallory J.P. Thames and Hudson Ltd., London 1989.

PARGITER 1962: Ancient Indian Historical Tradition. Pargiter F.E. Motilal Banarsidas, Delhi-Varanasi-Patna, 1962.

WINN 1995: Heaven, Heroes and Happiness: The Indo-European Roots of Western Ideology. Winn, Shan M.M. University Press of America, Lanham-New York-London, 1995.

WITZEL 1995a: Early Indian History: Linguistic and Textual Parameters. Witzel. Michael. pp. 85-125 in “The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia”, ed. by George Erdosy. Walter de Gruyter. Berlin, 1995.

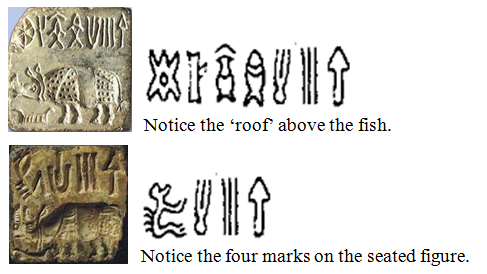

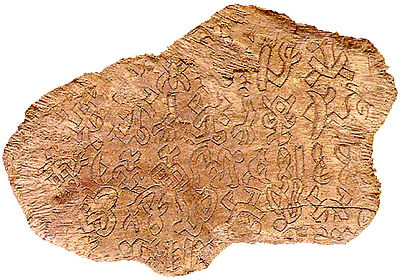

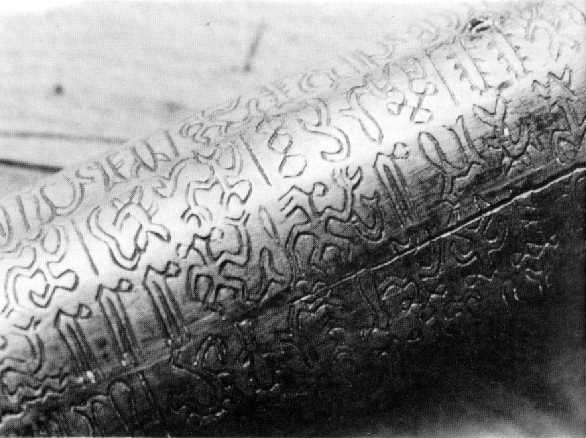

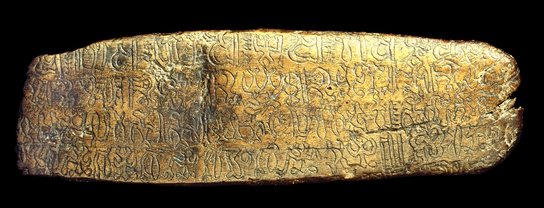

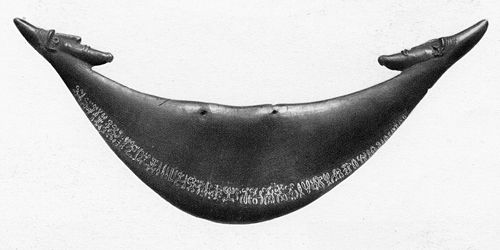

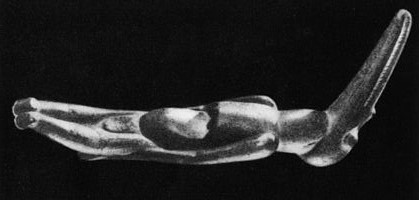

![Image result for mohenjodaro seal onager]() m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of = goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'

m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of = goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'![]() FS 72 Fig. 108 Chanhudaro seal. Person kneeling under a tree facing a tiger. [Chanhudaro Excavations, Pl. LI, 18]

FS 72 Fig. 108 Chanhudaro seal. Person kneeling under a tree facing a tiger. [Chanhudaro Excavations, Pl. LI, 18]![]() Feeding trough in front of cattle (even wild animals) pattar 'feeding trough' rebus: pattar, బత్తుడు battuḍu 'a guild, title of goldsmiths'. Ta. paṭṭai painted stripe (as on a temple wall), piebald colour, dapple.Ma. paṭṭa stripe. Ka. paṭṭe, paṭṭi id. Koḍ. paṭṭe striped or spotted (as tiger or leopard); paṭṭati n.pr. of dappled cow. Tu. paṭṭè stripe. Te. paṭṭe stripe or streak of paint; paḍita stripe, streak, wale.(DEDR 3877) Ta. pātti bathing tub, watering trough or basin, spout, drain; pattal wooden bucket; pattar id., wooden trough for feeding animals. Ka. pāti basin for water round the foot of a tree. Tu. pāti trough or bathing tub, spout, drain. Te. pādi, pādu basin for water round the foot of a tree(DEDR 4079)

Feeding trough in front of cattle (even wild animals) pattar 'feeding trough' rebus: pattar, బత్తుడు battuḍu 'a guild, title of goldsmiths'. Ta. paṭṭai painted stripe (as on a temple wall), piebald colour, dapple.Ma. paṭṭa stripe. Ka. paṭṭe, paṭṭi id. Koḍ. paṭṭe striped or spotted (as tiger or leopard); paṭṭati n.pr. of dappled cow. Tu. paṭṭè stripe. Te. paṭṭe stripe or streak of paint; paḍita stripe, streak, wale.(DEDR 3877) Ta. pātti bathing tub, watering trough or basin, spout, drain; pattal wooden bucket; pattar id., wooden trough for feeding animals. Ka. pāti basin for water round the foot of a tree. Tu. pāti trough or bathing tub, spout, drain. Te. pādi, pādu basin for water round the foot of a tree(DEDR 4079) m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of = goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'

m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of = goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'![]()

Portrait of Toramana.

Portrait of Toramana.

Signature stone.

Signature stone.

Zinc chloride.

Zinc chloride.

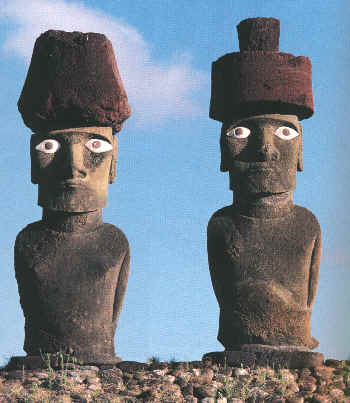

Peacocks and stars with the image of a person in cartouche. Funerary urn of Late Harappan Cemetery H at Harappa. After Piggott 1950: 234, fig. 29

Peacocks and stars with the image of a person in cartouche. Funerary urn of Late Harappan Cemetery H at Harappa. After Piggott 1950: 234, fig. 29 Figure of a person is ligatured within the body of the peacock with a wavy plume (first peacock on the right); The person shown within the circle is probably the depiction of the departed a_tman, who has, after cremation, become an ancestor. The stylized depiction of the arms is paralleled by the stylized depiction of arms (or horns?) of the copper anthropomorphs found in Copper Hoard Culture.

Figure of a person is ligatured within the body of the peacock with a wavy plume (first peacock on the right); The person shown within the circle is probably the depiction of the departed a_tman, who has, after cremation, become an ancestor. The stylized depiction of the arms is paralleled by the stylized depiction of arms (or horns?) of the copper anthropomorphs found in Copper Hoard Culture. The Samarra Bowl, Mesopotamia, Uruk Period, C. 4000 BCE

The Samarra Bowl, Mesopotamia, Uruk Period, C. 4000 BCE

Harappa, Indus River, Pakistan

Harappa, Indus River, Pakistan Kulli, Pakistan, before 3000 bce

Kulli, Pakistan, before 3000 bce

"Faience button seal (H99-3814/8756-01) with swastika motif found on the floor of Room 202 (Trench 43), Harappa, 2000-01"

"Faience button seal (H99-3814/8756-01) with swastika motif found on the floor of Room 202 (Trench 43), Harappa, 2000-01"

Variation of Svastika hieroglyph.

Variation of Svastika hieroglyph.

m1429a

m1429a

Specimen of calamine from mine at

Specimen of calamine from mine at

kole.l 'temple' Rebu: kole.l 'smithy' (Kota) baTa 'rimless pot' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace, kiln'.

kole.l 'temple' Rebu: kole.l 'smithy' (Kota) baTa 'rimless pot' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace, kiln'. Ficus benghalensis

Ficus benghalensis Santali glosses

Santali glosses

![clip_image062[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0624-thumb.jpg?w=99&h=45)

The compound pictorial motif ligaturing elephant with tiger atop a standard (flag post) is mounted on a platform.

The compound pictorial motif ligaturing elephant with tiger atop a standard (flag post) is mounted on a platform.

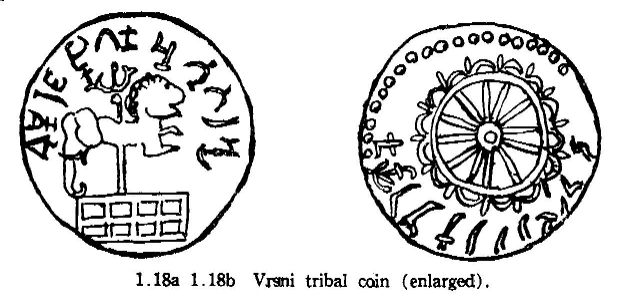

Kuninda coin. Chatreśvara.

Kuninda coin. Chatreśvara.

![clip_image004[3]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0043-thumb.jpg?w=186&h=124)

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Looking towards the Upper Rupin valley

Looking towards the Upper Rupin valley

Bronze coin of Huviška from Kashmir Smast (limestone caves) depicting elephant rider and eight armed Viṣṇu.

Bronze coin of Huviška from Kashmir Smast (limestone caves) depicting elephant rider and eight armed Viṣṇu.

Dholavira

Dholavira Harappa

Harappa Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro

.jpg)

Sanchi. Pilars with capitals.

Sanchi. Pilars with capitals.

The one-horned young bull of Indus Script Corpora is a

The one-horned young bull of Indus Script Corpora is a

Most detailed orthography of the mint hypertext appears in Bharhut and Sanchi toraṇa.'decorated gateway'. A variant is included in:Mathura lion capital inscription plaque between two seated tigers (or lions)

Most detailed orthography of the mint hypertext appears in Bharhut and Sanchi toraṇa.'decorated gateway'. A variant is included in:Mathura lion capital inscription plaque between two seated tigers (or lions)

Silver 25-mashakas

Silver 25-mashakas Silver 25-mashakas

Silver 25-mashakas

Silver 25-mashakas

Silver 25-mashakas