https://tinyurl.com/yb4db8vl

The best answer to the Steppe Sons hoax reported in The Economist, is provided by BB Lal. His lecture in 2007 is reproduced below for ready reference. For details of the hoax see: TO REVERT TO THE THEORY OF ‘ARYAN INVASION’ -- BB Lal (2007)

Inaugural Address delivered at the 19th International Conference of European Association of South Asian Archaeologists on South Asian Archaeology at University of Bologna, Ravenna, Italy on 2–6 July 2007

Distinguished fellow delegates and other members of the audience,

I am most grateful to the organizers of this conference, in particular to the President, Professor Maurizio Tosi, not only for inviting me to participate in this Conference but also for giving me the additional honour of delivering the Inaugural Address. Indeed, I have no words to thank them adequately for their kindness. Perhaps this is the first occasion when a South Asian is being given this privileged treatment by the European Association of South Asian Archaeologists.

The conference hall is full of scholars from all parts of the world – from the United States of America on the west to the Land of the Rising Sun, Japan, on the east. All these scholars have contributed in a number of ways to our understanding of the past of South Asia, and I salute them with all the humility that I can muster. However, I hope I will not be misunderstood when I say that some amongst us have not yet been able to shake off the 19th-century biases that have blurred our vision of South Asia’s past.

As is well known, it was the renowned German scholar Max Muller who, in the 19th century, attempted for the first time to date the Vedas. Accepting that the Sutra literature was datable to the 6th century BCE, he gave a block-period of 200 years to the preceding three parts of the Vedic literature, namely the Aranyakas, Brahmanas and Vedas. Thus, he arrived at 1200 BCE as the date of the Vedas. However, when his contemporaries, like Goldstucker, Whitney and Wilson, objected to his ad-hocism, he toned down, and finally surrendered by saying (Max Muller 1890, reprint 1979): “Whether the Vedic hymns were composed [in] 1000 or 1500 or 2000 or 3000 BC, no power on earth will ever determine.” But the great pity is that, in spite of such a candid confession by the savant himself, many of his followers continue to swear by his initial dating, viz. 1200 BCE.

The ultimate effect of this blind tenacity was that when in the 1920s the great civilization, now known variously as the Harappan, Indus or Indus-Sarasvati Civilization, was discovered in South Asia, and was dated to the 3rd millennium BCE, it was argued that since the Vedas were no earlier than 1200 BCE, the Harappan Civilization could not have been Vedic. Further, since the only other major linguistic group in the region was the Dravidian, it was held that the Harappans were a Dravidian-speaking people.

Then came the master stroke. In 1946, my revered guru Mortimer Wheeler (later knighted) discovered a fortification wall at Harappa and on learning that the Aryan god Indra had been referred to as puramdara (destroyer of forts) he readily pronounced his judgment (Wheeler 1947: 82): “On circumstantial evidence Indra [representing the Aryans] stands accused [of destroying the Harappan Civilization].” In further support of his thesis, he cited certain human skeletons at Mohenjo-daro, saying that these were the people massacred by the Aryan invaders. Thus was reached the peak of the ‘Aryan Invasion’ theory.

And lo and behold! The very first one to fall in the trap of the ‘Aryan Invasion’ theory was none else but the guru’s disciple himself. With all the enthusiasm inherited from the guru, I started looking for the remains of some culture that may be post-Harappan but anterior to the early historical times. In my exploration of the sites associated with the Mahabharata story I came across the Painted Grey Ware Culture which fitted the bill. It antedated the Northern Black Polished Ware whose beginning went back to the 6th-7th century BCE, and overlay, with a break in between, the Ochre Colour Ware of the early 2nd millennium BCE. In my report on the excavations at Hastinapura and in a few subsequent papers I expressed the view that the Painted Grey Ware Culture represented the early Aryans in India. But the honeymoon was soon to be over. Excavations in the middle Ganga valley threw up in the pre-NBP strata a ceramic industry with the same shapes (viz. bowls and dishes) and painted designs as in the case of the PGW, the only difference being that in the former case the ware had a black or black-and-red surface-colour, which, however, was just the result of a particular method of firing. And even the associated cultural equipment was alike in the two cases. All this similarity opened my eyes and I could no longer sustain the theory of the PGW having been a representative of the early Aryans in India. (The association of this Ware with the Mahabharata story was nevertheless sustainable since that event comes at a later stage in the sequence.) I had no qualms in abandoning my then-favourite theory.

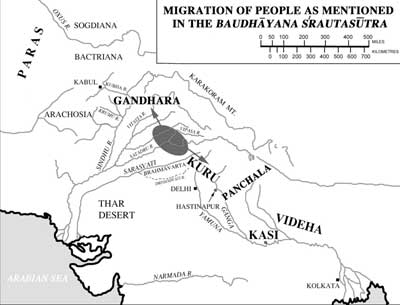

But linguists are far ahead of archaeologists in pushing the poor Aryans through the Khyber / Bolan passes into India. In doing so, they would not mind even distorting the original Sanskrit texts. A case in point is that of the well known Professor of Sanskrit at the Harvard University, Professor Witzel. He did not hesitate to mistranslate a part of the Baudhayana Srautasutra (Witzel 1995: 320-21). In 2003 I published a paper in the East and West (Vol. 53, Nos. 1-4), exposing his manipulation. Witzel’s translation of the relevant Sanskrit text was as follows:

"Aya went eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru-Pancalas and Kasi Videha. This is the Ayava(migration).(His other people)stayed at home in the west. His people are the Gandhari, Parasu and Aratta. This is the Amavasava (group).

Whereas the correct translation is:

Ayu migrated eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru-Pancalas and the Kasi-Videhas. This is the Ayava (migration). Amavasu migrated westwards. His (people) are the Ghandhari, Parsu and Aratta. This is the Amavasu (migration).

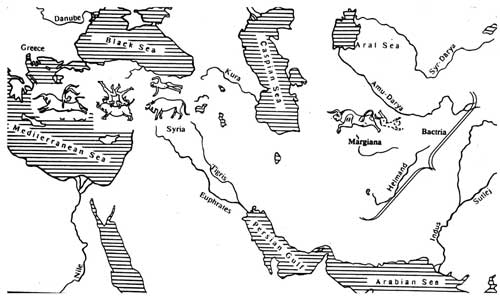

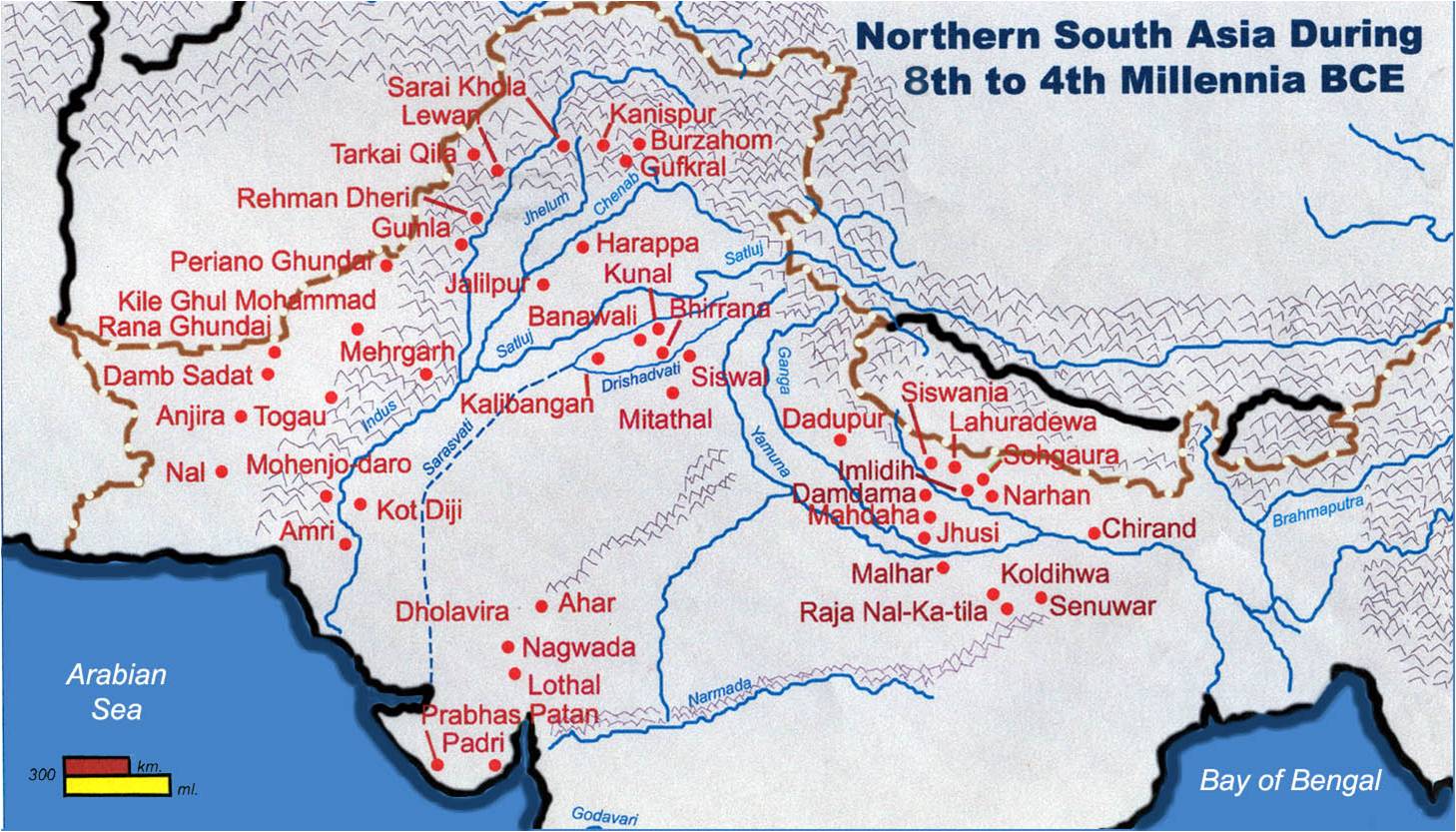

According to the correct translation, there was no movement of the Aryan people from anywhere in the north-west. On the other hand, the evidence indicates that it was from an intermediary point that some of the Aryan tribes went eastwards and other westwards. This would be clear from the map that follows(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Professor Witzel and I happened to participate in a seminar organized by UMASS, Dartmouth in June 2006. When I referred, during the course of my presentation, to this wrong translation by the learned Professor, he, instead of providing evidence in support of his own stand, shot at me by saying that I did not know the difference between Vedic and Classical Sanskrit. Should that be the level of an academic debate? (Anyway, he had to be told that I had the privilege of obtaining in 1943 my Master’s Degree in Sanskrit (with the Vedas included), with a First Class First, from a first class university of India, namely Allahabad.)

The year 1964 saw this theory being pushed back in the reverse gear. George F. Dales published a paper in which, after presenting a thorough analysis of the evidence, he completely lambasted the massacre theory and, in a way, rescued Indra from the charge of having been a marauder. Since then many other scholars (e.g. Danino 2006, Kenoyer 1998, Lal 2002 and 2005, Renfrew 1988, Shaffer and Lichtenstein 1999) have adduced further evidence to add successive nails on to the coffin of the ‘Aryan Invasion’ theory.

Unfortunately, however, the ghost of ‘Aryan Invasion’ is not buried deep enough. It is being resurrected in the form of ‘Aryan Immigration’, and in this context the Bactria-Margiana region is said to be the source. Out of the scholars who stand by this rejuvenated thesis, I shall deal here with four representative ones, namely Professors Romila Thapar and R. S. Sharma from India and Professors Asko Parpola and V. I. Sarianidi from the West.

But before the views of these four scholars are examined it seems appropriate to spell out in some detail the nature of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), even though some of the scholars present here may be familiar with it. I would also like to take this opportunity to heartily congratulate Professor Sarianidi and other archaeologists whose sustained fieldwork has placed the BMAC on the same high pedestal as occupied by other civilizations of the ancient world.

CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES OF THE BMAC

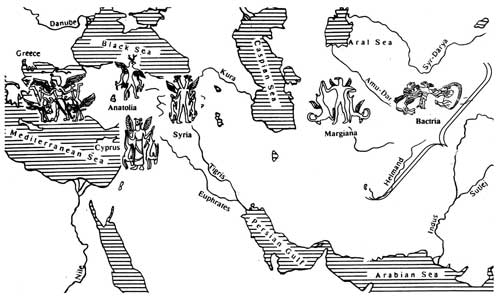

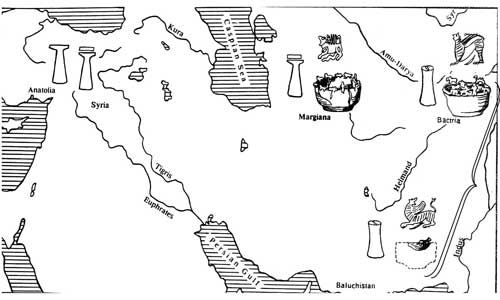

First, a map of the region involved is given below (Fig. 2):

Fig. 2. Region of Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex.

It is now proposed to discuss, though very briefly, the following features of the BMAC: (i) town-planning and monumental architecture; (ii) the ceramics; (iii) stone objects; (iv) metal objects; (v) sculptural art; (vi) seals and amulets; and finally (vii) the chronological horizon. This seemingly uncalled for exercise is being done in order to demonstrate that (a) the BMAC people were not nomads, as held by my Indian colleagues; and (b) these characteristic features of the BMAC never ever reached east of the Indus up to the upper Ganga-Yamuna doab – an area which was the homeland of the Rigvedic people, as is clear from the Nadi-stuti verses (10.75.5 and 6) of the Rigveda itself.

(I) TOWN-PLANNING AND MONUMENTAL ARCHITECTURE

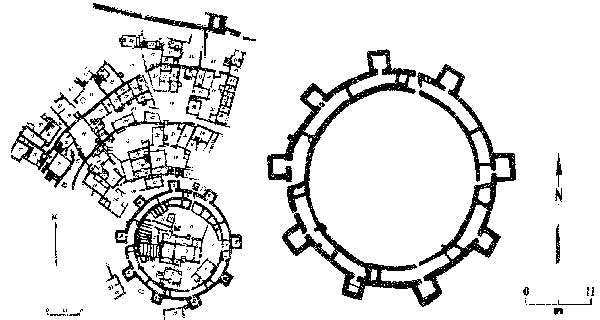

The BMAC settlements, by and large, were well planned and contained monumental structures. This is abundantly clear, for example, from the excavated remains at Dashly-3, in Bactria, where a ‘cultic centre’ has been found located within a series of three successive fortifications. The cultic centre, circular on plan, with a diameter of 40 metres, was provided with nine square bastions on the exterior (Fig. 3).

![]()

Fig. 3. Temple at Dashly-3, Bactria.

In Margiana, excavations at Togolok-1 and Togolok-21 have yielded the remains of multi-roomed temples, of which that at the latter site is more elaborate. Covering an overall area of about 1.5 hectares, the Togolok-21 complex had in the centre a 60 x 50 m. unit enclosed by a 5-m. thick wall which was provided on its exterior with four circular towers, one at each corner, and two semicircular towers, one each abutting the exterior of the eastern and western walls. This central unit had two more enclosure walls at successive distances, which too were provided with circular towers at the corners and semicircular towers along the walls (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Temple at Togolok-21, Margiana.

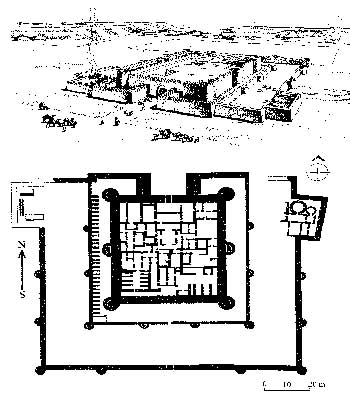

Besides the foregoing temples, at Gonur (also in Margiana) has been brought to light a massive architectural complex of secular nature. Called variously as ‘Citadel’ or ‘Kremlin’, it measures 120 x 115 m. on plan and is enclosed by a fortification wall, having on the exterior a rectangular tower at each corner and four rectangular towers on each side. Here is the plan of the ‘Kremlin’ which incorporates within its premises the king’s palace, audience hall, administrative blocks, garrison complex, etc. (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. ‘Citadel’ at Gonur, Margiana.(II) THE CERAMICS

Many of the BMAC settlements have yielded remains of pottery kilns, having a lower ‘fire-chamber’ and an upper ‘baking chamber’. The pot-forms include, besides others, large carafes with stretched narrow necks, vases with long slim stems and ‘tea-pots’ with spouts. The spouts themselves show a great variety, which includes ‘long tubular’ spouts, ‘bridge’ spouts and ‘trough or channel’ spouts (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Pottery vessels from Margiana.

Besides these distinctive spouted vessels, there is yet another category which calls for special attention. It is a basin or bowl having a frieze of small animals (sometimes humans as well) running along the rim. Also to be noted are serpents crawling up along the walls of the pot, both on the exterior as well as interior (Fig. 7). Although there is no conclusive contextual evidence to establish their ‘ritual association’, it has been surmised that these bowls may still have had such a use, primarily because the animal-cum-human frieze on the rims would render the bowls rather uncomfortable for the lips to directly drink a liquid from the bowls.

Fig. 7. Cult vessel from Togolok-1 temple.

(III) STONE OBJECTS

There is a great variety of stone objects in the BMAC: for example, beads and pendants of carnelian, lapis lazuli and turquoise, carved vessels of steatite, ‘diminutive columns’ of multicoloured stones and seals and amulets of steatite.

The illustration that follows shows a cup-on-stand and a deep inward-tapering bowl of black steatite. Both these bear etched geometrical designs on the exterior (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Carved stone vessels from Gonur, Margiana.

The ‘diminutive columns’, also known as ‘dainty columns’ or ‘dainty pillars’, are generally less than half-metre in height, highly polished and sometimes provided with a vertical groove. While their exact use is debated, it has been suggested by certain scholars that these were used in some kind of ritual (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Stone ‘dainty columns’ from the temple, Togolok-21.(IV) METAL OBJECTS

The BMAC settlements, including graves, have yielded a large number of metal objects, mostly of bronze / copper but sometimes of silver and gold too. Here we illustrate two very distinctive axes. On one of these there sits a human figure at the butt-end, whereas in the other case that position is occupied by an animal (Fig. 10).

However, much more remarkable is an axe, made of silver but covered with gold lamina. The decoration showing a winged feline and heads of two eagles would appear to have had some mythological import (Fig. 11). It also seems most likely that this axe was not used for cutting wood or for a similar purpose but may have been ceremonial in nature – perhaps mounted on a specially made staff and held by a person in authority, as a mark of his position.

![spacer]()

Fig. 10. Bronze axes.

![]()

Fig. 11. Silver ceremonial axe.

(V) SCULPTURAL ART

Though we have already dealt with objects of stone and metal and with ceramics, we discuss here separately the art of sculpting in stone, metal and earthenware, since these objects throw valuable light on the artistic acumen of the BMAC people and demonstrate how very individualistic was their art-style.

Here is a stone sculpture of a seated lady from Bactria (Fig. 12). In order to bring out the contrast in the portrayal, the sculptor has chosen a blackish stone for the dress with which the major part of the body is covered, but a pinkish white one for the head and hands. Also to be noted are not only the herring-bone weave (decoration) of the garment, but also the details in depicting the hairstyle.

Fig. 12. Composite stone figurine.

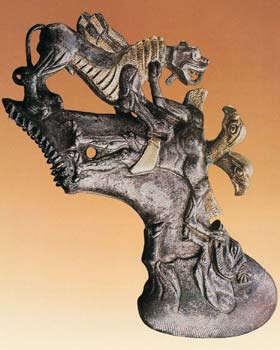

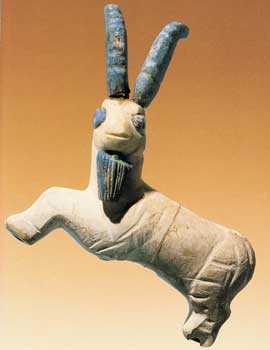

It is not just the human beings that attracted the attention of the BMAC artist, but the animal-world as well. And here are two objects, both from Bactria, one depicting a feline (Fig. 13) and the other a goat (Fig. 14).

Fig. 13. Chlorite and gold leaf representation of a feline,

with semiprecious stone inlay.

The gold leaf and inlay-work in the case of the former are indeed superb and so also is the choice of coloured stones in the case of the goat, namely lapis lazuli for the horns, eyes and beard and limestone for the rest of the body.

Fig. 14. Limestone goat with horns, eyes and beard in lapis lazuli.

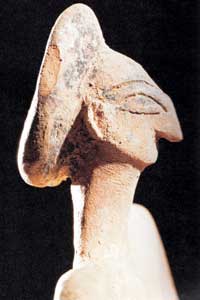

Though termed as ‘the poor man’s medium’ of art-expression, the earthen sculptures are no less remarkable. Take for example, the following figurine from Gonur Depe necropolis in Margiana. It has a slender neck, aquiline nose, prominent eyes, arched eyebrows, receding forehead and a very distinctive headdress (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Terracotta figurine from Gonur Depe necropolis.(VI) SEALS AND AMULETS

Seals and amulets are a very significant constituent of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, since the individual motifs as well as the narrative scenes depicted thereon throw valuable light on the religious beliefs and practices of the people. The seals were made of metals, such as copper / bronze and silver, while the amulets were usually of stone, mostly black steatite. These latter usually show, amongst other motifs, snakes, scorpions, eagles, two-humped (typically Bactrian) camels, felines, etc. The snake seems to be such a favourite that it is depicted on the ceramic ‘rituals bowls’ as well (already referred to). The metal seals are to be noted, besides other motifs, for geometric ones. But most spectacular are the narratives on the cylindrical seals. We propose to illustrate these later when their narratives will also be discussed.

(VII) THE CHRONOLOGICAL HORIZON–

A good deal of controversy surrounds the origin of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, namely whether it was a local development from Namazga V or it was born out of an external impetus. Be that as it may, Carbon-14 dates indicate that Period 1 at Gonur Depe may have commenced around 2100 BCE and continued up to 1900 BCE, while Period 2, which is what is known as the BMAC proper, may be ascribed to circa 2000-1700 BCE.

AN ANALYSIS OF THE VARIOUS VIEWS

In the earlier part of this Address we had stated that we shall examine the viewpoints of Professors Romila Thapar and R. S. Sharma on the one hand and of Professors Asko Parpola and Viktor Sarianidi on the other. Thus, we begin with the views of the first two scholars.

VIEWS OF ROMILA THAPAR AND R. S. SHARMA

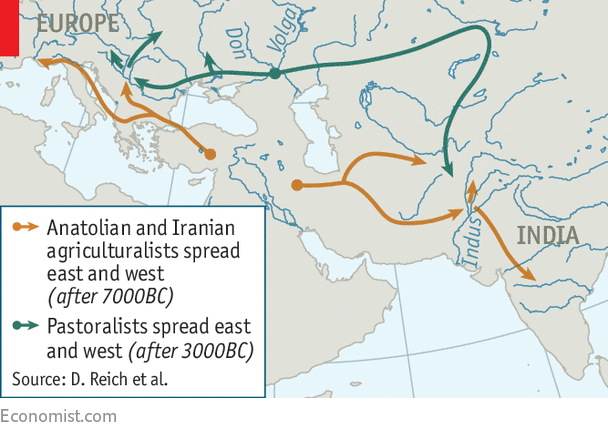

Having failed to establish an ‘Aryan Invasion’ of India, Professor Thapar comes out (1989-91: 259-60) with a new theory, viz.: “If invasion is discarded then the mechanism of migration and occasional contacts come into sharper focus. The migrations appear to have been of pastoral cattle-breeders who are prominent in the Avesta and Rigveda”.

Following faithfully the footsteps of Thapar and amplifying her stand, Professor Sharma avers (1999: 77): “... the pastoralists who moved to the Indian borderland came from Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex or BMAC which saw the genesis of the culture of the Rigveda.”

Both Thapar and Sharma are even now labouring under the 19th century belief that the Vedic Aryans were nomads. But have they even once cast a glance at the make-up of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. As would have been absolutely clear by now, the BMAC is a fully developed civilization with all the trappings of urbanism. How can then Thapar and Sharma devalue the Bactria-Margiana people and call them ‘pastoral cattle-breeders’? Just to fit into their preconceived notion that the¡Rigvedic Aryans were ‘nomads’?

VIEWS OF ASKO PARPOLA

In his paper, ‘Margiana and the Aryan Problem’, Asko Parpola states (1993: 47): “These excavations at Mehrgarh, Sibri, Nausharo and Quetta have conclusively shown that immigrants bringing with them an entire new cultural complex have settled in Baluchistan, with close parallels in Gurgan, south Turkmenistan, Margiana and Bactria of the Namazga V-VI period.”

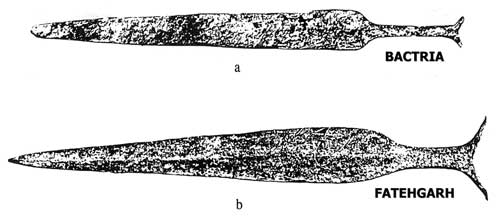

Whereas certain parallels between the Quetta-Sibri finds and those from the Bactria-Margiana regions are acceptable, one is really baffled by the succeeding statement of Parpola, namely: “A newly found antennae-hilted sword from Bactria paralleling those from Fatehgarh suggests that this same wave of immigrants may also have introduced the Gangetic Copper Hoards into India.” (Fig. 16).

Fig. 16. Antennae-hilted swords of copper.

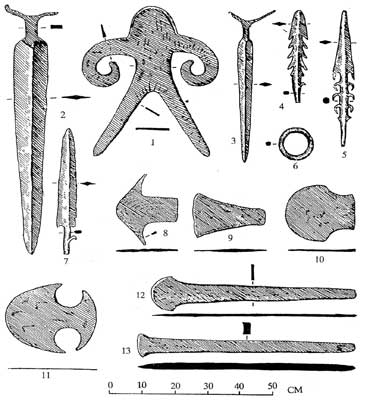

I am sure Parpola is aware of the fact that the Copper Hoards of the Gangetic Valley, as would be seen from the illustration that follows (Fig. 17), include many other very distinctive types, such as anthropomorphic figures, harpoons, shouldered axes, etc. which have never been found in Bactria.

Fig. 17. Copper hoards from the Gangetic valley, India.

Further, the overall cultural ethos, including the distinctive pottery, of the Gangetic Copper Hoards is totally different from that of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex and that the former cannot be derived from the latter. But more strange is the argument that the occurrence of a single antennae-hilted sword in Bactria would entitle that region to be the ‘motherland’ of the Gangetic Copper Hoard people who produced these copper weapons and other associated objects in hundreds, if not thousands. If this logic is stretched further, I will not be surprised if one day Parpola comes out with the thesis that the Harappan Civilization too originated in Margiana, because in that region (at Gonur) has been found one steatite seal bearing typical Harappan inscription and motif (Fig. 18), unmindful of the fact that such seals constitute an integral part of the Harappan Civilization.

Fig. 18. Harappan seal from Gonur, and its impression.

If, following the footsteps of Parpola, I were to say that the find of the well known seal of the ‘Persian Gulf’ style at Lothal in Gujarat establishes that the Persian Gulf Culture (which abounds in such seals) originated in Gujarat or, again, if I said that the occurrence of a cylinder seal at Kalibangan in Rajasthan entitles Rajasthan to be the ‘motherland’ of the Mesopotamian Culture (wherein cylinder seals are found in large numbers), I am sure my learned colleagues present here would at once get me admitted to the nearest lunatic asylum.

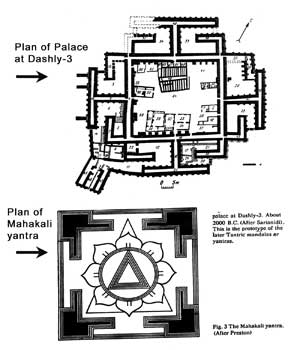

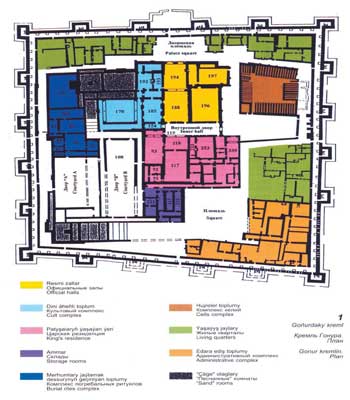

One finds yet another amusing example of a similar kind of unbridled imagination when Parpola calls the ground-plan of the palace at Dashly-3, datable to circa 2000 BCE, “the prototype of the later Tantric mandalas / yantras”. He then goes on to add: “That the religion of the Dasas [who are mentioned in the Rigveda and whom he identifies with the Bactria-Margiana people] was an early form of Ýaktism is also suggested by the ground plan of the palace of Dashly-3 in Bactria closely agreeing with the later Tantric mandalas...”(ibid.: 52). For the sake of unambiguity, I reproduce now the drawings of the Dashly-3 Palace and the Mahakali yantra (Fig. 19), as published by Parpola himself (ibid.: 62), and leave it to the learned scholars to decide whether they too would like to accompany Parpola in crossing this 4000-year-old and 4000-kilometre-long bridge along with Parpola.

![temple]()

Fig. 19.

Must we really indulge in such a kite-flying just to support our preconceived notions?SARIANIDI’S VIEWS

It has been claimed by certain scholars, including Sarianidi, that the BMAC people were the forebears of the Iranians and Indo-Aryans. This conclusion seems to have been drawn primarily on the following four counts: viz.

(i) fire-worship temples of BMAC;

(ii) supposed use of soma / homa in BMAC rituals;

(iii) mistaken identity of a horse’s skeleton as evidence of the asvamedha; and

(iv) cult motifs on the BMAC glyptics.

We shall now examine, though briefly, the evidence in respect of these four claims.

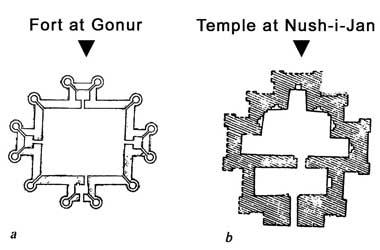

(i) Fire WorshipIt has been argued that the BMAC temples were devoted to fire-worship and that since this kind of worship constitutes the main religious base of the Zoroastrians, they and the BMAC people shared a common ancestry. This is what Sarianidi says (1993a: 679) in this context: “A building unearthed at Gonur temenos and conveniently called a fort has a cross-shaped general plan with twelve corner towers. It most closely resembles the outer contours of the indisputable fire temple at Tepe Nush-i-Jan. A difference of minor importance only consists of the fact that while the towers are round at Gonur, they are square at Tepe Nush-i-Jan” (Fig. 20). But he immediately admits the weakness of the comparison by stating: “Unfortunately, the fort (at Gonur temenos) appears to be unfinished so we do not know its inner construction, but apparently it too was a fire temple.” What is the great point in forcing such a comparison when the evidence itself so weak?

Fig. 20.

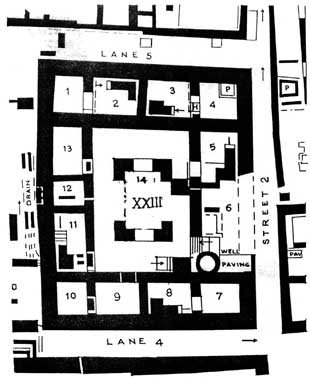

In order to show that the Indian subcontinent was also involved in such a fire-worship, Sarianidi adds (ibid., p. 676): “An example is the fire temple in the lower town of Mohenjo-daro; its basic plan comprises a ‘courtyard encompassed by corridors’ (Dhavalikar and Atre 1989)” (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21. Mohenjo-daro: “Fire Temple”

In their article, Dhavalikar and Atre have gone into a series of conjectures, there being no down-to-earth evidence for actual fire worship in that complex. On the contrary, Marshall (1931, Vol. I: 202) takes this structure to have been a normal residential house. But in his desperation to bring India as well into the orbit of a Zoroastrian kind of fire worship, Sarianidi has completely lost sight of the fact that the house-complex at Mohenjo-daro belongs to the Indus Civilization of the 3rd millennium BCE whereas the BMAC is much later, dated to the 2nd millennium BCE. Thus, if at all the comparison made by Sarianidi is accepted, the direction of movement will have to be from India to Central Asia and not vice-versa!

(ii) The Soma / Homa

It has been claimed that there occurred the remains of ephedra and poppy in the temple of Togolok-21 in Margiana and since ephedra has been thought to be identical with the soma / homa of the Rigveda / Avesta, the BMAC people must have been the ancestors of the Indo-Iranians. There are two snags in this thesis. In the first place, not all experts agree that soma / homa is nothing but ephedra. But what is more important is that Harri Nyberg, a well known authority on the subject, after a thorough examination of the Toglok evidence, writes (1995: 400):

... remains of ephedras have also been reported from the temple-fortress complex of Togolok 21 in the Merv oasis (ancient Margiana – Parpola 1988; Meier-Melikyan 1990) along with the remains of poppies. ... In 1990 I received some samples from the site [forwarded by Dr. Fred Hiebert of Harvard University] , which were subjected to pollen analysis at the Department of Botany, University of Helsinki. .... The largest amount of pollen was found in the bone tube (used for imbibing liquid?) from Gonur 1, but even in this sample, which had been preserved in a comparatively sheltered position when compared with the other investigated samples, only pollen of the family Caryophyllaceae was present. No pollen from ephedras or poppies was found and even the pollen left in the samples showed clear traces of deterioration (typical in ancient pollen having been preserved in a dry environment in contact with oxygen). Our pollen analysis was carefully checked for any methodological errors, but no inaccuracies were found.

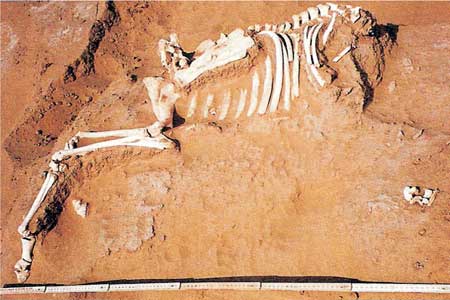

(iii) The Asvamedha

The discovery, in the cemetery area at Gonur, of the skeleton of a horse, with its head missing, has led Sarianidi to postulate that it is a case of the Asvamedha (horse sacrifice); and since the Asvamedha is a ritual mentioned in the Rigveda, he argues that the authors of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex must have been the ancestors of the Rigvedic Aryans.

Before we examine the validity of such a conclusion, let us have a look at the photograph of the skeleton, published by Sarianidi himself (Fig. 22).

Fig. 22. Burial (?) of a horse in Gonur Depe.

It would be seen from the photograph that there is no clear outline of a pit in which the horse is supposed to have been regularly buried. Further, the skeleton lies hardly a few centimetres below the ground-level. Thus, there could have been many other reasons for the head to be missing, such as erosion through natural agencies or subsequent human interference.

And no less important is the fact that the skeletal remains do not conform to the manner in which the horse had to be sacrificed in the asvamedha.

There are two Suktas in the Rigveda, viz. 1.162 and 1.163, which are devoted to the Asvamedha and lay down how the horse, tied with ropes and accompanied by a goat, had to be taken to the sacrificial altar and then, after some rituals, had to be sacrificed. I quote below two of the verses, viz. 1.162.18 and 1.162.19, which are very relevant here.

“The axe penetrates the thirty-four ribs of the swift horse, the beloved of the gods, (the immolators), cut up (the horse) with skill, so that the limbs may be unperforated and recapitulating joint by joint. (18)

“There is one immolator of the radiant horse, which is Time: that are two that hold him fast: such of thy limbs as I cut up in due season. I offer them, made into balls (of meat), upon the fire.” (19)

The foregoing description makes it abundantly clear that in the case of the asvamedha the horse had to be cut up into parts, ‘recapitulating joint by joint’.

There is hardly any evidence of such a cutting up in the case of the horse’s skeleton discovered at Gonur. Then why be so imaginative as to call this skeleton as evidence of the asvamedha and thereby draw an uncalled for conclusion that the BMAC people were the ancestors of the Rigvedic Aryans ?(iv) Motifs on BMAC glyptics

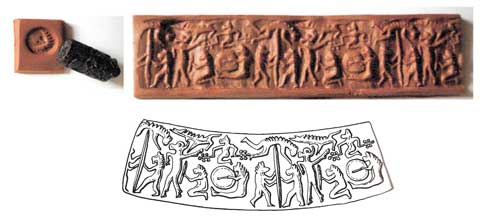

The fourth argument that has been pressed into the service of the supposed BMAC = Aryan equation is that the motifs on the BMAC seals compare with certain motifs on the Syro-Hittite glyptics and since there occur on some Boghaz Qui tablets the names of Vedic deities, viz. Indra, Mitra, Varuna and Nasatya, the Boghaz Qui Aryans must be at the root of BMAC ethnic make-up. To quote Sarianidi (op.cit.: 677): “Since it is Mitanni texts that contain the oldest mention of Aryan deities, there cannot be any doubt about the connection of the Mitanni empire with the so-called Aryan problem. As the replication of Mitanni art in Bactria and Margiana is clearly not coincidental, we are justified in connecting the tribes migrating into Central Asia and the Indus Valley with the settlement process of the Aryan or Indo-Iranian tribes.”

Elsewhere Sarianidi goes into the details of these Syro-Hittite vis-a-vis Bactria-Margiana glyptic parallels. For example, he states (1993b: 12-13):

In this connection worthy of utmost attention is the impression of a cylinder seal on one of the Margianian vessels, found .... at Gonur. The central figure of a frequently repeated frieze composition is a standing nude anthropomorphic winged deity with an avian head holding two mountain goats by the legs....

Such anthropomorphic winged and avian-headed deities are represented fairly fully in the glyptics and on the seals of Bactria.... These Bactrian images find the most impressive correspondence in Syro-Hittite glyptics....

If the fact that it’s for the Mittani kingdom that the names of Aryan deities are evidenced is taken into account the importance of the Bactrian-Margianian images will become obvious in the light of solving the Aryan problem on the basis of new archaeological data.

While one has little hesitation in accepting the above-noted Syro-Hittite vis-a-vis Bactria-Margiana parallels, what indeed is the basis of connecting these motifs with the Aryan gods, viz. Indra, Maruta, Varuna and Nasatya? (cf. Fig. 23).

Fig. 23. Impression of cylinder seal from Gonur-1

Does Sarianidi think that the ‘standing nude anthropomorphic winged deity with avian head’ and holding animals by their tails in each hand represents one of the above-mentioned Vedic gods– Indra, Maruta, Varuna, Nasatya?

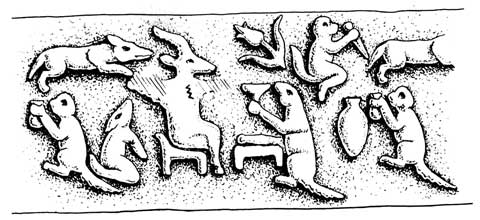

Likewise, what precisely Aryan is there in the narrative portrayed on another cylinder seal? (Fig. 24).

Fig. 24. Cylinder seal from Togolok-21 and its impression.

Perhaps one fine morning someone might be tempted to designate the scene depicted on the next seal as “ The offering of Soma to Indra”, where Indra is the central figure seated on a chair and his devotees are offering the soma in cups, the beverage itself being stored in the jar! (Fig. 25).

FINALLY, THE MOST CRUCIAL ASPECT OF THE ISSUE

The following three maps (Figs. 26, 27 & 28), not drawn by me but published by Sarianidi himself (1993b: Figs. 2, 3 and 5) relate to the spatial distribution respectively of ‘the motif of man-bird with hit animals’, ‘the motif of acrobats jumping over bulls’, and ‘miniature columns and cult vessels with depiction of snakes and animals on the rim’.

Fig. 26. Spread of the motif of man-bird with hit animals.

Fig. 27. Spread of the motif of acrobats jumping over bulls.

Fig. 28. Spread of ‘miniature columns’ and their probable

prototypes in the Sypro-Hittite world.

A careful look at these maps would make it abundantly clear that the glyptic motifs shown on the first two maps occur from the Bactria-Margiana region on the east to the Syro-Hittite region on the west but do not travel southwards in the direction of Baluchistan. It is only the miniature columns and bowls bearing on their rim animal-and-snake motifs that find their way into Baluchistan. But in no case did any of the above-noted motifs, columns or snake-decorated bowls find their way east of the Indus up to the upper reaches of the Ganga-Yamuna doab which, as spelt out in the Nadi-stuti Sukta of the Rigveda itself (10.75.5-6), was the region occupied by the Rigvedic Aryans.

The only exceptions to the foregoing distribution-pattern are some seals / seal-impressions from Chanhu-daro and Gilund (Possehl 2004: figs. 7 and 15). Sometimes, a double-spiral-headed copper pin from Chanhu-daro (Mackay 1976, reprint, p. 195, pl. LXVIII, 9) and a two-animal-headed antimony stopper-rod, also of copper, from Harappa (Vats 1974, reprint, p. 390, pl. CXXV, 36) are also brought into the discussion. But let it be remembered that all these are only peripheral to the most characteristic and core items of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. Anyway, it would be simply ridiculous to ascribe these few objects to a migration of the BMAC people (cf. Gupta 2006, under print). Have we not in the past explained the occurrence of some items of a given culture-complex in another complex by means of trade / exchange / casual gift or a similar mechanism: for example, the occurrence of Harappan seals, etched carnelian beads, etc. in Mesopotamia, Iran and even Central Asia by trade and not by migration of the Harappan population? Then why invoke the migration of the BMAC people to explain the presence of some seals / seal-impressions, etc. at stray Indian sites?

In the context of the debate whether the ¡Rigvedic people were indigenous or invaders / immigrants from outside, the evidence of two sister disciplines, namely human biology and human genetics, must also be brought into the picture.

After a thorough examination of the relevant human skeletons, Hemphill and his colleagues (1991) categorically pronounced: “As for the question of biological continuity within the Indus Valley, two discontinuities appear to exist. The first occurs between 6000 and 4500 BC ... and the second occurs at some point after 800 BC.” In other words, there was no entry of a new set of people between 4500 and 800 BCE, much less of Aryan invaders / immigrants !

In recent years a great deal of genetic research has been carried out which too throws valuable light on this issue; and I quote here Sanghamitra Sahoo, et al. (2006: 843-48): “The sharing of some Y-chromosomal haplogroups between Indian and Central Asian populations is most parsimoniously explained by a deep, common ancestry between the two regions, with the diffusion of some Indian-specific lineages northward. The Y-chromosomal data consistently suggest a largely South Asian origin for Indian caste communities and therefore argue against any major influx, from regions north and west of India, of people associated either with the development of agriculture or the spread of the Indo-Aryan language family.”

Scholars have already abandoned (though after much dithering) the ‘Aryan Invasion’ theory. Is it not high time to rethink and shelve the newly hugged-to-the-chest ‘Bactria-Margiana Immigration’ thesis as well?

At the end, it needs to be emphasized that the purpose of this Address was not to criticize Professor X or Professor Y. Far from it. The whole emphasis has been on demonstrating how the 19th-century paradigms are still dominating our thinking, thereby producing a very blurred vision of South Asia’s past. Can’t we begin thinking afresh in this 21st century?

* * *

REFERENCES

Dales, G.F. 1964. The Mythical Massacre at Mohenjo-daro. Expedition 6(3): 36-43.

Danino, M. 2006. L’Inde et l’invasion de nulle part. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Dhavalikar, M. K. and Shubhangana Atre. 1989. The Fire Cult and Virgin Sacrifice: Some Harappan

Rituals. In J. M. Kenoyer (ed.) Old Problems and New Perspectives in the Archaeology of South Asia,

Wisconsin Archaeological Reports, Vol. 2, pp.193-205.

Gupta, S. P. 2006 (under print). Did the BMAC ever cross the Indus? Paper presented at an international conference held at Vadodara in 2005.

Hemphill, B. E. et al. 1991. Biological Adaptations and Affinities of Bronze Age Harappans. In R. H. Meadow (ed.) Harappa Excavations 1986-1990, pp. 137-82. Madison, Wisconsin: Prehistory Press.

Kenoyer, J. M. 1998. Ancient Cities of the Indus Civilization. Karachi: Oxford University Press and American Institute of Pakistan Studies.

Lal, B. B. 2002. The Sarasvati Flows On: The Continuity of Indian Culture. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

——. 2005. The Homeland of the Aryans: Evidence of Rigvedic Flora and Fauna & Archaeology. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

Ligabue, G. and S. Salvatori. 1989. Bactria: an Ancient Oasis Civilization from the Sands of Afghanistan. Venice: Erizzo.

Mackay, E. J. H. 1976, reprint. Chanhu-daro Excavations 1935-36. Delhi: Bhartiya Publishing House.

Marshall, John. 1931. Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization. 3 vols. London: Arthur Probsthain.

Muller, F. Max. 1890, reprint1979. Physical Religion. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

Nyberg, Harri. 1995. The Problem of the Aryans and the Soma: The Botanical Evidence. In G. Erdosy (ed.) The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia, pp. 382-406. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Parpola, Asko. 1993. Margiana and the Aryan Problem. In IASCCA Information Bulletin, 19, pp.41-62. Nauka.

Possehl, Gregory L. et al. 2004. The Ahar-Banas Complex and the BMAC, Man and Environment, Vol. XXIX, No. 2, pp. 18-29.

Renfrew, C. 1988. Archaeology and Language. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sahoo, Sanghamitra,et al. 2006. A Prehistory of Indian Y Chromosomes: Evaluating Demic Diffusion Scenarios. PNAS, Vol. 103, No. 4: 843-48.

Sarianidi, V. I. 1993 a. Margiana and the Indo-Iranian World. South Asian Archaeology, Vol. II, pp.667-80.

——. 1993 b. Margiana in the Ancient Orient. In IASCCA Information Bulletin, 19, pp. 5-28. Nauka.

Sarianidi, V. I. 2002. Margush. Ancient Oriental Kingdom in the Old Delta of the Murghab River. Ashgabat.

Shaffer, Jim.G. and Diane Lichtenstein 1999.Migration. Migration, Philology and South Asian Archaeology. In Johannes Bronkhorst and Madhav M. Deshpande (eds.), Aryan and Non-Aryan in South Asia: Evidence, Interpretation and Ideology. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Sharma, R. S. 1999. Advent of the Aryans in India. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers.

Thapar, Romila. 1988-91. In Journal Asiatic Society of Bombay, Vol. 64-66, pp.259-60.

Vats, M. S. 1974, reprint. Excavations at Harappa. Delhi: Bhartiya Publishing House.

Wheeler, R. E. M. 1947. Harappa 1946: The Defences and Cemetery R 37. Ancient India, 3: 58-130.

Witzel, M. 1995. Rigvedic history: poets, chieftains and polities. In George Erdosy (ed.) The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia, pp. 307-52. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

![]() Marble , Sarasvati Civilization ( Photo - @metmuseum )

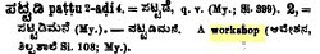

Marble , Sarasvati Civilization ( Photo - @metmuseum )![]() Deśīnāmamālā Glossary, p. 71 The early meaning of the lexeme meḍh can be traced from the semantics recorded in the following lexemes of Indian linguistic area; as Pischel notes, the word meḍh can be identified as susbtratum semantic for 'helper/assistant of merchant): MBh. [mēṭha -- 1, mēṇḍa -- 3 m. ʻ elephant -- keeper ʼ lex., Pa. hatthimeṇḍa -- m. ʻ elephant -- driver ʼ, Pk. meṁṭha -- , miṁṭha -- , miṁṭhala -- , mahāmettha -- (note final -- th in P. below), metthapurisa -- m. (Pischel PkGr 202) may point to a non -- Aryan word for ʻ elephant -- driver ʼ which became associated with mahāmātra -- : EWA ii 611. -- mahā -- , māˊtrā -- ] (CDIAL 9950). meṇḍa, मेण्ठः मेण्डः An elephant-keeper (Apte. lex.) a groom, elephant -- driver in cpd. hatthi˚ elephants' keeper J iii.431; v.287; vi.489. (Pali).

Deśīnāmamālā Glossary, p. 71 The early meaning of the lexeme meḍh can be traced from the semantics recorded in the following lexemes of Indian linguistic area; as Pischel notes, the word meḍh can be identified as susbtratum semantic for 'helper/assistant of merchant): MBh. [mēṭha -- 1, mēṇḍa -- 3 m. ʻ elephant -- keeper ʼ lex., Pa. hatthimeṇḍa -- m. ʻ elephant -- driver ʼ, Pk. meṁṭha -- , miṁṭha -- , miṁṭhala -- , mahāmettha -- (note final -- th in P. below), metthapurisa -- m. (Pischel PkGr 202) may point to a non -- Aryan word for ʻ elephant -- driver ʼ which became associated with mahāmātra -- : EWA ii 611. -- mahā -- , māˊtrā -- ] (CDIAL 9950). meṇḍa, मेण्ठः मेण्डः An elephant-keeper (Apte. lex.) a groom, elephant -- driver in cpd. hatthi˚ elephants' keeper J iii.431; v.287; vi.489. (Pali). ![]()

![]() पोळ [pōḷa] 'zebu'पोळ [pōḷa] 'magnetite, ferrite ore'; kāṇḍa 'rhonoceros' rebus:.kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Gujarati); mẽḍhā m. 'markhor' Rebus: mẽḍh 'iron' (Mu.), med 'copper' (Slavic languages) mẽṛhẽt 'iron' (Santali), meḍho 'helper of merchant'..

पोळ [pōḷa] 'zebu'पोळ [pōḷa] 'magnetite, ferrite ore'; kāṇḍa 'rhonoceros' rebus:.kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Gujarati); mẽḍhā m. 'markhor' Rebus: mẽḍh 'iron' (Mu.), med 'copper' (Slavic languages) mẽṛhẽt 'iron' (Santali), meḍho 'helper of merchant'.. Marble , Sarasvati Civilization ( Photo - @metmuseum )

Marble , Sarasvati Civilization ( Photo - @metmuseum ) Deśīnāmamālā Glossary, p. 71 The early meaning of the lexeme meḍh can be traced from the semantics recorded in the following lexemes of Indian linguistic area; as Pischel notes, the word meḍh can be identified as susbtratum semantic for 'helper/assistant of merchant): MBh. [mēṭha -- 1, mēṇḍa -- 3 m. ʻ elephant -- keeper ʼ lex., Pa. hatthimeṇḍa -- m. ʻ elephant -- driver ʼ, Pk. meṁṭha -- , miṁṭha -- , miṁṭhala -- , mahāmettha -- (note final -- th in P. below), metthapurisa -- m. (Pischel PkGr 202) may point to a non -- Aryan word for ʻ elephant -- driver ʼ which became associated with mahāmātra -- : EWA ii 611. -- mahā -- , māˊtrā -- ] (CDIAL 9950). meṇḍa, मेण्ठः मेण्डः An elephant-keeper (Apte. lex.) a groom, elephant -- driver in cpd. hatthi˚ elephants' keeper J iii.431; v.287; vi.489. (Pali).

Deśīnāmamālā Glossary, p. 71 The early meaning of the lexeme meḍh can be traced from the semantics recorded in the following lexemes of Indian linguistic area; as Pischel notes, the word meḍh can be identified as susbtratum semantic for 'helper/assistant of merchant): MBh. [mēṭha -- 1, mēṇḍa -- 3 m. ʻ elephant -- keeper ʼ lex., Pa. hatthimeṇḍa -- m. ʻ elephant -- driver ʼ, Pk. meṁṭha -- , miṁṭha -- , miṁṭhala -- , mahāmettha -- (note final -- th in P. below), metthapurisa -- m. (Pischel PkGr 202) may point to a non -- Aryan word for ʻ elephant -- driver ʼ which became associated with mahāmātra -- : EWA ii 611. -- mahā -- , māˊtrā -- ] (CDIAL 9950). meṇḍa, मेण्ठः मेण्डः An elephant-keeper (Apte. lex.) a groom, elephant -- driver in cpd. hatthi˚ elephants' keeper J iii.431; v.287; vi.489. (Pali).

पोळ [pōḷa] 'zebu'पोळ [pōḷa] 'magnetite, ferrite ore'; kāṇḍa 'rhonoceros' rebus:.kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Gujarati); mẽḍhā m. 'markhor' Rebus: mẽḍh 'iron' (Mu.), med 'copper' (Slavic languages) mẽṛhẽt 'iron' (Santali), meḍho 'helper of merchant'..

पोळ [pōḷa] 'zebu'पोळ [pōḷa] 'magnetite, ferrite ore'; kāṇḍa 'rhonoceros' rebus:.kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Gujarati); mẽḍhā m. 'markhor' Rebus: mẽḍh 'iron' (Mu.), med 'copper' (Slavic languages) mẽṛhẽt 'iron' (Santali), meḍho 'helper of merchant'.. m0491

m0491

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia. Sohgaura coper plate inscription. ca. 7th cent.BCE Pre-Mauryan.

Sohgaura coper plate inscription. ca. 7th cent.BCE Pre-Mauryan.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā

K

K

Cancho Roano

Cancho Roano  Side view showing the depth of the Burney relief.

Side view showing the depth of the Burney relief.  Approximate red ochre colour scheme of the painted relief. Her necklace is composed of squares (like coins of Nishka). She wears bracelets with three rings. She has flight feathers. Lines on ankles and toes depict scules, with talons on visible toes. She stands atop two lions and flanked by two owls. The sculptural frieze is a hieroglyp-multiplex.

Approximate red ochre colour scheme of the painted relief. Her necklace is composed of squares (like coins of Nishka). She wears bracelets with three rings. She has flight feathers. Lines on ankles and toes depict scules, with talons on visible toes. She stands atop two lions and flanked by two owls. The sculptural frieze is a hieroglyp-multiplex.

h1966A h1966B

h1966A h1966B

FS Fig. 92 (Fig. 92 and Fig. 106 are h180 A and B (two sides of a tablet with same text of inscription Text 4304 on both sides).

FS Fig. 92 (Fig. 92 and Fig. 106 are h180 A and B (two sides of a tablet with same text of inscription Text 4304 on both sides).

Tail of composite animal seals

Tail of composite animal seals

![clip_image057[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0574-thumb.jpg?w=80&h=68)

L

L

Seated position of anthropomorph, Signifies kamaḍha 'penance' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'.

Seated position of anthropomorph, Signifies kamaḍha 'penance' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'.

From Lothal was reported a fragmentary Type 1 anthropomorph (13.0 pres. X 12.8 pres. X c. 0.08 cm, Cu 97.27%, Pb 2.51% (Rao), surface ptterning runs lengthwise, lower portion slightly thicker than the edge of the head, 'arms' and 'legs' broken off (Pl. 1, 22)-- ASI Ahmedabad (10918 -- Rao, SR, 1958, 13 pl. 21A)

From Lothal was reported a fragmentary Type 1 anthropomorph (13.0 pres. X 12.8 pres. X c. 0.08 cm, Cu 97.27%, Pb 2.51% (Rao), surface ptterning runs lengthwise, lower portion slightly thicker than the edge of the head, 'arms' and 'legs' broken off (Pl. 1, 22)-- ASI Ahmedabad (10918 -- Rao, SR, 1958, 13 pl. 21A)

FS 78 Fig. 114 From R. - a horned pe rsonagc standing between the branches of a pipal trec: a low pedestal with some offerings: a horned personage kneeling in adoration; ram; a row of seven robed figures in the lower register.

FS 78 Fig. 114 From R. - a horned pe rsonagc standing between the branches of a pipal trec: a low pedestal with some offerings: a horned personage kneeling in adoration; ram; a row of seven robed figures in the lower register.

![clip_image062[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0624-thumb.jpg?w=99&h=45)

Ruhuna coin

Ruhuna coin Taurine-shaped bead

Taurine-shaped bead

Copper plate m1457

Copper plate m1457

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Fig. 10. Bronze axes.

Fig. 10. Bronze axes.