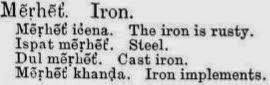

The Mother Goddess The people of the Indus Valley cities, also worshiped a Mother Goddess. The importance accorded to these roles and also to the feminine, can be drawn from the number of figurines excavated. The important uncovered poses include – a Dancing Girl, and terracotta figurines of what can be identified as Fertility goddess.

![indus-goddess Mother Goddess figurine]()

MOTHER GODDESS FIGURINE

![dancinglady_sm Metal figurine of Dancing Lady]()

METAL FIGURINE OF DANCING LADY

![teracotta-fertility-goddess Terracotta Fertility Goddess]()

TERRACOTTA FERTILITY GODDESS, SOURCE: HARAPPA.COM

TERRACOTTA GODDESS WITH PANNIER HEADDRESS. SOURCE: HARAPPA.COM

One of the largest female figurines found at Harappa has a (badly broken) fan-shaped pannier headdress with black residue in the cups of the panniers and a forward-projecting face. She is heavily ornamented with an elaborate choker and two other necklaces, each with three strands and many pendants. This elaborate ornamentation of figurines is one reason that female figurines have often been interpreted as deities, most commonly as “Mother Goddesses.”

Residues that may indicate burning of oils or other substances in the panniers have also prompted a cultic interpretation and ritual worship. [http://www.harappa.com/figurines/15.html

]

Women in Ancient Sindh: Bronze Age Figurines of the Indus Valley Civilization

In this 2004 article from the quarterly publication Sindh Watch, Paolo Biagi synthesizes the evidence of female clay figurines from Bronze Age sites in the Indus Valley to highlight the social and cultural roles of women in that society. He draws on earlier evidence from the neolithic site of Mehrgarh, in Balochistan, as well as that from mature Harappan sites like Mohenjodaro and Harappa. Based on this analysis he offers the following insights into the role of women as depicted in the figurines:

"Although little is known of the true role women played in the Indus Valley Civilization...there is little doubt that many of them represent fertility images, as suggested by characteristics depicted in the statuettes. The hairstyles, ornaments and dressing clearly indicate the important prominence assigned to women at that time in what appeared to be a nearly egalitarian society. Additionally, the bronze 'Dancing Girls' statuettes suggest specific, public activities played by women at that time. Of extreme interest is also the occurrence of specific naturalistic goddesses and their priestesses, which suggest that the Indus people worshipped a goddess whose domain was the forest."

2004 From a history of the portrait in art David J Bromley, M.F.A. inst.2004 Section Class Portfolio:

A Glimpse at the Human Figurines of the Indus Valley Civilization - Jithin R. Veer ![]()

Seated Mother Goddess of Çatal Hüyük

c. 6000 B.C. | The Fall 2004 Module, "History of the Portrait," focused on the evolution of art, beginning from ancient drawings of animals, and sometimes humans, on cave walls, to figurine sculptures such as "fertility figures," and on to artwork during the Egyptian, Greek, and Roman eras, eventually leading to the more sophisticated portraiture of the Northern and Southern European Renaissance. I found the concept of human figurines to be very interesting because I did not expect figurines of the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic Eras to be ancestors of the Renaissance-era work of da Vinci, or Velasquez, or the predecessors of modern paintings from artists such as Picasso or Dali. The human figurines discussed in class were primarily "fertility figures"– figures paying homage to the fertility of the female and the virility of the male in the act of procreation -- originating from European, or "Western" cultures such as Mesopotamia, closer to the waters of the Mediterranean. Professor Bromley mentioned in class that Eastern European art of the Paleolithic through the Neolithic Eras focused more on this type of sculpture compared to portraiture. However, the use of human figurines is not exclusive to Western art; it extends to the art of Eastern Asian cultures as well. Human figures of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization in present-day Pakistan and India of South Asia exemplify the common use of human figurines as fertility figures, and also illustrate the roles of children, women, and men of Indus Valley culture. The Indus human figurines are somewhat similar in their purpose in society, but are differentiated from their Western counterparts in the figurines’ ornamental features. |

| During the Paleolithic and much of the Neolithic Eras, mankind was primarily living as a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, first using stones as tools. Humans needed to hunt animals for their sustenance; communal bonds between hunters and their families may have developed, but the need to settle permanently on the land was not justified. However, by the end of the Neolithic Era, a few civilizations such as Egypt and Mesopotamia in the West/Middle East, and the Indus Valley and China in the East, began to develop as people began to depend on each other for physical, psychological, and cultural means. Of these ancient civilizations, perhaps it is the Indus Valley Civilization that is most easily overlooked by modern researchers. Nevertheless, the Indus Valley Civilization was one of the most advanced settlements of its day. Situated along the banks of the Indus River moving inland from the Arabian Sea, the Indus Valley Civilization is thought to have extended for about 700 years, from around 2600 to 1900 BC. The Indus Valley Civilization was only brought to an end by a combination of attacks by Aryan neighbors to the west and a decline caused by an overextension of resources. The Indus Valley Civilization could be best described as a complex network of at least 1500 towns and cities spread over 680,000 sq. kilometers of land. The inhabitants of the Indus Valley are believed to have been dark-skinned, or Dravidian, most likely ancestors of the darker-skinned peoples of South India. A few of the most well-known Indus cities include Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa. All cities were designed according to a master plan, and featured organized housing for the rulers, well-to-do, and the commoners. Most cities were constructed out of brick and featured communal areas such as "Great Baths," likely used for cultural/spiritual purposes. Cities were also advanced – in Mohenjo Daro, every house had a private well dug deep to provide water, along with public wells located outside for the general public and travelers. All cities also had an organized system to safely transport sewage waste away, and most houses had private bathing areas and latrines. While the language(s) of the Indus Valley have not yet been deciphered, evidence of written documents and inscriptions prove the presence of sophisticated communication in the Indus society. Art and cultural development was also important to the dwellers of the Indus Valley Civilization. The importance of art can be seen on ornamented seals belonging to rulers, to terra-cotta disposable drinking cups. | ![]()

Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro

c. 2500 B.C. |

![]()

Beaded necklace of the Indus Valley

c. 2,600 – 1,900 B.C. | | Jewelry was highly ornamented, and every man and woman wore at least one piece of jewelry. A few types of jewelry such as necklaces and bangles show direct lineage to the more ornamented necklaces and bangles of modern Indian jewelry. | | ![]()

Terra-cotta figure with a headdress of flowers

c. 3000 B.C. | Human figurines were also found in the Indus Valley. Like other civilizations such as Mesopotamia which featured human figurines, the use of these figurines was to primarily celebrate childbirth and fertility in the female and virility for the male. It is presumed that the human figurines may have been involved in a cultural or ceremonial event. However, one reason why human figurines are often hard to find intact or in good condition in the Indus Valley is that the figurines were often given as toys to children after their ceremonial use and then likely discarded. This is in sharp contrast to Mesopotamia, where human figurines were often involved in the burial process. In addition, the figurines at the Indus Valley excavation sites were found to be primarily made out of the medium terra-cotta. |

| Figurines of children are a common find among the Indus figurines. Children were highly revered as they were the products of the successful act of procreation and childbirth. Due to complications in pregnancy, the mortality rate for women and children during childbirth was relatively high. Many children figurines are actually children nursing at the breasts of their mother. The position of the figurine is usually a nursing infant situated on the left hip, while leaving the mother’s right arm free to perform other tasks. This anatomical position is similar to the characteristic pose of Indian village women, nursing their young, today. Like other civilizations of the time, the children are depicted to be primarily male, perhaps showing a gender bias. However, the children figurines of the Indus Valley are markedly different than their counterparts in the West in their ornamentation. Children figurines of the Indus are usually shown nude, but their ornamentation often includes a necklace and a turban (males). This is culturally significant because both genders wore necklaces and the turban is a hairdressing still worn today by many Indian men. Other figurines of children include their toys as well. One common toy many children figurines have in their hand or are associated, is a small disc. These small discs are part of a game called "pittu." In this game, still played today in North India and Pakistan, a group of children stack up their discs and attempt to knock all of the discs down by throwing a ball. Other games include terra-cotta spinning tops and miniature objects such as musical instruments and cooking pans, meant to prepare children for an adult life. | |

| "Figurines of women are perhaps the most plentiful of the figurines in Indus Valley. The reason for this is unknown, but it proposed that women were given a special place culturally in society, due to their ability to produce offspring. Indeed, studies of burial sites at Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa have shown that a man was often buried with his wife’s family. The female figurines are easily distinguished by a curving, pear-shaped body with large protruding breasts. The effect of these female figurines is two-fold: it emphasizes the beauty, and phallic/ sexual nature of the female; but at the same time, cherishes the nurturing, motherly nature of the female. The figurines of the women tend to also be heavily ornamented. It is, therefore, easier to learn about the culture of the Indus Valley through these female figurines." (encarta.msn.com)

The head region of the figurines usually show a complex arrangement of hair and flowers and usually head ornaments, therefore showing a greater cultural interest in hair style, likely related to a particular ethnic community or family within the civilization. On many figurines seen today, parts of the headdresses have broken off. Clothing on women figurines include short skirts. Additional ornaments on the female figurines include belts, necklaces, and bangles. While males also wore these accessories, the female figurines demonstrate that the women most likely wore larger, more prominent necklaces, and a variety of many bangles on their arm. In reality, this jewelry was gold, bronze, agate, ivory, and semiprecious stones. However, in the figurines, they are simply outlined and sculpted onto the surface. Almost all figurines were crafted from terra-cotta, but a few sculptures towards the end of the Indus Valley Civilization have been cast of bronze. Modern bronze sculptures, especially prominent in Hindu India, seem to have originated from the human figurines of the Indus Valley. |

Figurines of men are slightly harder to find in the Indus Valley excavations compared to those of females. Figurines of men tend to be more simplistic, and little can be told of their clothing or accessories they may have worn. This is because most male figurines are shown in the nude. The reason for this is not known, but could be because of the ceremonial purposes of the male figurine related to strength and virility. Because the male figurines were not considered to be as beautiful as the female figurines, many male figurines studied today are broken in half or have substantial parts missing. Nevertheless, it is possible to reconstruct the ornamental design of the male figurines and draw parallels to the Indus Valley society. For example, almost all male figurines have a turban, or similar style of headdress. Some male figurines which are intact with their arms may hold a spear, signaling strength and protection of the Indus from outside attack. Many adult male figurines have a projection on the chin for a beard, some closely combed, others combed out, and spread wide. Male figurines tend to have much less jewelry than the females; male jewelry in the Indus Valley figurines typically includes one necklace or one bangle on an arm. It is likely that the materials used to make these ornaments for men were different than the materials and styles used for the women, however it is difficult to make a distinction in the figurines themselves. However, males in higher socio-economic levels tended to have more ornaments; the famous "Priest-King" sculpture (right) of Mohenjo-Daro shows multiple pieces of jewelry, such as a bangle and a headband.

The human figurines of the Indus Valley Civilization reflect the common use of figurines in all cultures during this time period, to celebrate the act of procreation and childbirth. While celebrating fertility and virility may seem arcane in a modern context, producing children successfully was a crucial yet dangerous task for all members of society, in order to ensure survival of the family unit, civilization, and their culture. However, the human figurines of the Indus Valley Civilization are unique in that their figurines are more than objects celebrating procreation – the figurines also include details of the clothing, jewelry, hair styles, and toys that were integral to the Indus Valley Civilization. While much of the puzzles surrounding life in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China have been solved by extensive research, excavation, and a deciphering of their languages, modern society is only now beginning to unlock the stories behind one of the oldest civilizations of the world - the Indus Valley Civilization. Because the ancient languages of the Indus have not been deciphered yet, by studying the significance of these human figurines and other pieces of art, researchers can better understand the civilization that is arguably the birthplace of all modern cultures of the Indian subcontinent. | ![]()

2200-1900 B.C. |

References "Indus Valley Civilization." Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia Online. Internet. Online ed. 2004. <http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761556839/Indus_Valley_Civilization.html>

Urmila, Sant. Terracotta Art of Rajasthan (From Pre-Harappan and Harappan Times to the Gupta Period). New Delhi, India: Aryan Books International, 1997.

Pulsipher, Lydia Mihelic, and Alex Pulsipher. World Regional Geography. 2nd ed. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company, 2003.

Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark. Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Bromley, David J. 17 Dec 2004. History of Portraiture - VCU Honors. 01 Nov 2004. <http://www.artviews.net>. |

http://www.people.vcu.edu/~djbromle/artviewsnet/portrait04/jithin/indusvalley.htm

[quote]The Indus Valley Civilization ensued during the Bronze Age (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE). It mostly spread along the Indus and the Punjab region, extending into the Ghaggar-Hakra river valley and the Ganga-Yamuna Doab, surrounding most of what is now Pakistan, the western states of modern-day India, as well as extending into south-eastern Afghanistan, and the easternmost part of Baluchistan, Iran. The geography of the Indus Valley put the civilizations that arose there in a similar situation to those in Egypt and Peru, with rich agricultural lands being surrounded by highlands, desert, and ocean. Of late, Indus sites had been discovered in Pakistan's north-western Frontier Province as well. Other smaller isolated colonies were found as far away as Turkmenistan. Coastal settlements extended from Sutkagan Dor in Western Baluchistan to Lothal in Gujarat. An Indus Valley site was located on the Oxus River at Shortughai in northern Afghanistan, By 2600 BCE, early communities turned into large urban centres. Such inner-city centres included Harappa, Ganeriwala, Mohenjo-Daro in Pakistan, and Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Rupar, and Lothal in India. In total, over 1,052 cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the region of the Indus and the tributaries.

Steatite seals had images of animals, people (perhaps gods), and other types of inscriptions, including the yet un-deciphered writingsystem of the Indus Valley Civilization. A number of gold, terra-cotta and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses showed the presence of some dance form. Also, these terra-cotta figurines included cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs. Sir John Marshall reacted with surprise when he saw the famous Indus bronze statuette of a slender-limbed dancing girl in Mohenjo-Daro: When I first saw I found it difficult to believe that they were prehistoric; they seemed to completely upset all established ideas about early art, and culture. Modelling such as this was unknown in the ancient world up to the Hellenistic age of Greece, and I thought, therefore, that some mistake must surely have been made; that these figures had found their way into levels some 3000 years older than those to which they properly belonged.

Now, in these statuettes, it was just this anatomical truth which was so startling; that made us wonder whether, in this all-important matter, Greek artistry could possibly have been anticipated by the sculptors of a far-off age on the banks of the Indus. It was widely suggested that the Harappan people worshipped a Mother goddess symbolizing fertility. A few Indus valley seals displayed swastika sign which were there in many religions, especially in Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. The earliest evidence for elements of Hinduism is before and during the early Harappan period. Phallic symbols close to the Hindu Shiva lingam was located in the Harappan ruins. Mohenjo-Daro or “heap of the dead” was the largest city excavated of the Indus Valley, or Harappa Civilization. Mohenjo-Daro was a Sindhi word in the locality meaning ‘mound of the dead’...

Hwen Tsang in 630-635 CE saw a palisade (stupa) of Mauryan times. It was one hundred feet high. Cunningham said of this pillar: The principality of Middle Sind, which is generally known as Vichalo or ‘Midland’ is described by Hwen Tsang as only 2,500 li or 417 miles in circuit. The chief city, named ‘O-fan-cha’ was at 700 li or 117 miles from the capital of the upper Sind, and 50 miles from Pitasala, the capital of lower Sind. As the former was Alor, and the latter was almost certainly the Pattale of the Greeks or Haiderabad, the recorded distances fix the position of O-fan-cha in the immediate neighbourhood vicinity of the ruins of an ancient city called Bambhra-ka-Thul or simply Bambhar. This, according to tradition, was the site of the once famous city of Brahmanwas or Brahmanabad […].

The city can be located because the circumstances are narrated in detail. The king of the city had previously submitted, but the citizens withheld their allegiance, and shut their gates. By a stratagem, they were induced to come out, and a conflict ensued, in which Ptolemy was seriously wounded in the shoulder by a poisoned sword. The mention of Ptolemy’s wound enables us to identify this city with that of Hermetalia, which Diodorus describes as the ‘last town of the Brahmins on the river.

Hermes in Greek is the muted term for Brahma. The Chinese syllable fan is the well-known phrasing of Brahma. Hence, both O-fan-cha and Hermetalia is a direct wording of Bambhra-ka-thul or Brahma-sthal. From all these discussions, it seemed certain that what Hwen Tsang visited was the city of Mohenjo-Daro and its real name was Brahma-sthal or Brahmanabad. The meaning of the name Mohenjo-Daro is ‘Heap of the Dead’. Such a name seems peculiar for a prosperous city like this. The Hindi word was mohan jodad.o. This word jodad.o had cognates in many mleccha, meluhha languages. The Sindhi word d.a_r.o meant ‘feast given to relatives in honour of the dead’. A number of scholars made out that meluhha was the Sumerian name for mleccha, meaning non-Vedic, barbarian. It was used by the Aryans much as the ancient Greeks used barbaros, indicating garbled speech of foreigners or native people of the country.

The city flourished between 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE, although the first signs of settlement in the area had been dated to the period of 3500 BCE. Excavation at this level was impossible due to the high water table that made even simple excavations of Mohenjo-Daro difficult. The city covered around 200 hectares of land and at its height might have had a population of 85, 000 people. The site was located in the modern Larkana district of Sind province in Pakistan. Mohenjo-Daro was the largest city in the southern portion of the Indus Valley Civilization and important for trade and governance of this area.

The Great Mound, or Citadel, stood out the west end of Mohenjo-Daro. The mound rose 40 feet about the plain at present time; it would have been higher at the time Mohenjo-Daro was inhabited. There was a gap between the mound and the lower city. Because of the large size and separation from the rest of the city, it was thought the mound might have been used for a religious or administrative purpose. This hypothesis was supported by the architecture found on the top of the mound. The mound at Mohenjo-Daro had two distinct features: the Great Bath and the Granary or Meeting hall. The Great Bath was a sunken tank on the top of the mound; the tank was 12 meters long, 7 meters wide and was sunk 2.4 meters below the depth of the mud bricks that enclosed it. The Great Bath was one of the first aspects of Indus Valley life that could be related to modern Hinduism. The Great Bath might also be linked to the concept of river worship, much like the worship of the River Ganga today.[unquote]http://www.ancient.eu/article/230/

Archaeology of the goddess: an Indian paradox (Bibliography by A. Di Castro)

Abhinavagupta 1985, Parātriṃśikāvivaraṇa, Il commento di Abhinavagupta alla

Parātriṃśikā, translated by Raniero Gnoli, Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed

Estremo Oriente, Roma.

—— 1987, Tantrāloka 1987, with the commentary of Jayaratha, re-edited by RC

Dwivedi and Navjivan Rastogi, enlarged with an introduction by Navjivan

Rastogi, 8 vols, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

—— 1990, The Dhvanyāloka of Anandavardhana with the Locana of

Abhinavagupta, translated by Daniel HH Ingalls, Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson and

MV Patwardhan; edited with an introduction by Daniel HH Ingalls, Harvard

University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Agrawal, Dileep P 1982, The archaeology of India, Curzon, London.

Agrawala, Prithvi Kumar 1983, Mithuna. the male female symbol in Indian art and

thought, Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi.

—— 1984, Goddesses in Ancient India, Abhinav Publications, New Delhi.

—— 1993, Ancient Indian mother-goddess votive discs, Books Asia, Varanasi.

Agrawala, Vasudeva S 1970, Ancient Indian folk cults, Prithivi Prakashan,

Varanasi.

Ahmad, Zahiruddin 1999, Saṅs-rGyas rGya-mTsho: life of the Fifth Dalai Lama,

International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan, New Delhi.

Allchin, Bridget and Frank Raymond Allchin 1982, The rise of civilization in India

and Pakistan, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Allchin, Frank Raymond 1995, ‘Mauryan architecture and Art’ in Allchin, FR,

The archaeology of Early Historic South Asia, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Amiet, Pierre 1986, L’âge des èchanges inter-iraniens 3500–1700 avant J-C,

Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris.

Apte, VS 1979, The student’s Sanskrit English dictionary, Motilal Banarasidass,

New Delhi.

Bibliography

209

210 the iconic female

Ardeleanu-Jansen, Alexandra 1992, ‘New evidence on the distribution of artifacts:

an approach towards a qualitative-quantitative assessment of the terracotta

figurines of Mohenjo-Daro’ in Catherine Jarrige, John P Gerry, and Richard H

Meadow (eds), South Asian archaeology 1989, Prehistory Press, Madison.

Arts Council of Great Britain, 1971, Catalogue of the exhibition on Tantra.

Atre, Shubhangana 1998, ‘The high priestess: gender signifiers and the feminine in

the Harappa context’, South Asian Studies 14.

Babb, LA 1970, ‘The uses of sexual opposition in a Hindu pantheon’, Ethnology

9(2).

—— 1975, Popular Hinduism in Central India, Columbia UP, New York.

Bailey, Greg 1995, The Gaṇeśa Purāṇa, Volume One: Upāsanā Khaṇḍa, Otto

Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden.

—— 2008, The Gaṇeśa Purāṇa, Volume Two: Krīḍā Khaṇḍa, Otto Harrassowitz,

Wiesbaden.

Banerjea, Jitendra Nath 1956, The development of Hindu iconography, University

of Calcutta, Calcutta.

—— 1966, Purāṇic and tāntric religion, University of Calcutta, Calcutta.

Banerji, Arundhati 1994, Early Indian terracotta art, Harman Publishing House,

New Delhi.

Barth, F 1959, Political leadership among the Swat Pathans, Athlone Press,

London.

Bhāgavata Purāṇa 1950, NR Acarya, (ed), Bombay.

Bhattacharyya, Narendra Nath 1996, History of the Śākta religion, Munshiram

Manoharlal, New Delhi.

—— 1999, The Indian mother goddess, third enlarged edition, Manohar, New

Delhi.

Biardeau, Madeleine (ed) 1981, Autour de la déesse hindoue, Ecole des hautes

études en sciences sociales, Paris.

—— (trans R Nice) 1989, Hinduism: the anthropology of a civilisation, Oxford

University Press, New Delhi.

—— 2004, Stories about posts: Vedic variations around the Hindu Goddess,

translated by Alf Hiltebeitel, Marie-Louise Reinike and James Walker,

University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Boyce, Mary 1975, A history of Zoroastrianism Vol 1, EJ Brill, Leiden.

Brahmānda Purāṇa 1993, Vol 23 Part I in Shastri, JL (ed), Ancient Indian tradition

and mythology, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Brooks, DR 1990, The secret of the three cities, an introduction to Hindu śākta

tantrism, Chicago UP, Chicago.

bibliography 211

Bruckner, Heidrun 1994, ‘Divinity, violence, wedding and gender in some South

Indian cults’ in Schwartz, AM et al (eds), Wild goddesses in India and Nepal:

proceedings of an international symposium, Berne and Zurich, November 1994,

Peter Lang, Bern.

Bryant, Edwin 2001, The quest for origins of Vedic culture, Oxford University

Press, Oxford and New York.

Bryant, Edwin and Laurie L Patton (eds) 2005, The Indo-Aryan controversy:

evidence and inference in Indian history, Routledge, London and New York.

Bühnemann, Gudrun 2000-2001, Iconography of Hindu tantric deities, 2 vols,

Egbert Forsten, Groningen.

Byron, John 1987, Portrait of a Chinese paradise, Quartet Books, London.

Caldwell, Sarah 2005, ‘Margins at the center: tracing Kālī through time, space

and culture’ in McDermott, Rachel Fell and Jeffrey J Kripal (eds), Encountering

Kālī: In the margins, at the center, in the West, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Campbell, James 1884, Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, vol 23, Bijapur.

Campbell, JM (ed) 1918, Hindu tribes and castes of Gujarat, Bombay Presidency

Gazetteer.

Campbell, June 2002, Traveller in space: gender, identity and Tibetan Buddhism,

Continuum, London.

Chakrabarti, Dilip 2001, ‘The archaeology of Hinduism’ in Insoll, Timothy (ed)

Archaeology and world religion, Routledge, London, New York.

—— 2004, ‘Introduction’ in Chakrabarti, DK (ed), Indus Civilization sites in

India: new discoveries, Marg Publications, Mumbai.

Chandra, Pramod 1971, ‘The cult of Śrī Lakshmī and four carved discs in Bharat

Kala Bhavan’, Chhavi Golden Jubilee Volume, Bharat Kala Bhavan, Banaras

Hindu University, Varanasi.

Choudhary, Radakrishna 1964, The Vrātyas in Ancient India, Chowkhamba

Sanskrit Series Office, Varanasi.

Clark, Sharri R 2003, ‘Representing the Indus body: sex, gender, sexuality,

and the anthropomorphic terracotta figurines from Harappa’, The Journal of

Archaeology for Asia and the Pacific 42(2).

Codrington, K de B 1935, ‘Iconography, Classical and Indian’, Man 35(70).

Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish 1971 [1928 & 1931], Yakṣas, Munshiram

Manoharlal, New Delhi.

Courtright, Paul B 2001 (1985), Gaṇeśa: lord of obstacles, lord of beginnings,

Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Crooke, William 1907, Natives of Northern India, Constable & Company, London.

Czuma, Stanislaw 1985, Kushan sculpture: images from early India, Cleveland

Museum of Art in association with Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

212 the iconic female

Dani, AH 1999 [1992], ‘Pastoral-agricultural tribes of Pakistan in the post-

Indus period’ in Dani, AH and VM Masson (eds), History of civilizations of

Central Asia, Vol 1, The dawn of civilization: earliest times to 700 BC, Motilal

Banarsidas, Delhi.

Dani, AH and BK Thapar 1999 [1992], ‘The Indus civilization’ in Dani, AH and

VM Masson (eds), History of civilizations of Central Asia, Vol 1, The dawn of

civilization: earliest times to 700 BC, Motilal Banarsidas, Delhi.

Daniélou, Alain 1994, The complete Kāma Sūtra, Park Street Press, Rochester.

Das Gupta, Charu Chandra 1961, Origin and evolution of Indian clay sculpture,

University of Calcutta Press, Calcutta.

de Mallmann, Marie-Thérèse 1963, Les enseignements iconographiques de l’Agni-

Purāṇa, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

de Sade, le Marquis 1969, Justine, ou les malheurs de la vertu, Union Générale

d’Edition, Paris.

Dehejia, Vidya 1986, Yoginī cult and temples: a tantric tradition, National

Museum, New Delhi.

—— 1999, Devi: the great female divinity in South Asian art, Arthur M Sackler

Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Mapin Publishing, Ahmedabad &

Prestel Verlag, Munich.

Desai, Devangana 1975, Erotic sculpture of India: a socio-cultural study, Tata

McGraw Hill, New Delhi.

Dexter, MR (ed) 1990, Whence the goddesses. a source book, Pergamon, New

York.

Dhavalikar Madhukar Keshav 1977, Masterpiece of Indian terracottas,

Taraporevala, Bombay.

—— 1985, ‘Chalcolithic cultures: a socio-economic perspective’ in Dikshit,

KN (ed), Archaeological perspectives of India since Independence, Books and

Books, New Delhi.

—— 1987, ‘Śakaṃbharī—the headless goddess’, Annals of the Bhandarkar

Oriental Research Institute 68.

—— 2002, Environment and culture: a historical perspective, Bhandarkar Oriental

Research Institute, Pune.

Dhere, RC 1988 (1978), Lajjagauri, Shri Vidya Prakashan, Pune (Marathi).

Di Castro, Angelo Andrea 1998, L’archeologia dell’Uttarāpatha tra il V e il

III sec. a. C., Istituto Universitario Orientale, Naples (unpublished doctoral

dissertation).

Dimmit, C and JAB van Buitenen 1978, A Reader in the Sanskrit Purāṇas, Temple

University Press, Philadelphia.

Donaldson, Thomas 1975, ‘Propitious-apotropaic eroticism in the art of Orissa’,

Artibus Asiae 35(1–2).

bibliography 213

Doniger, Wendy 1995, ‘Introduction’ in Eilberg-Schwartz, Howard and Wendy

Doniger, Off with her head!: the denial of women’s identity in myth, religion and

culture, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Dupuche, John 2003, Abhinavagupta, the Kula ritual as elaborated in Chapter 29

of the Tantrāloka, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Eilberg-Schwartz, Howard and Wendy Doniger (eds) 1995, Off with her head!,

University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Eisler, Riane 1992, ‘La Dea della natura e della spiritualità: un ecomanifesto’ in

Campbell, Joseph & Charles Musés (eds), I nomi della Dea: Il femminile nella

divinità , Ubaldini Editore, Rome (translation of In All Her Names: Explorations

of the Feminine Divinity, 1991), Harper and Row, San Francisco.

Eller, Cynthia 2000, The myth of matriarchal prehistory: why an invented past

won’t give women a future, Beacon Press, Boston.

Erdosy, George (ed) 1995, The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: language,

material culture and ethnicity, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York.

Erndl, Kathleen 1993, Victory to the Mother: the Hindu goddess of northwest India

in myth, ritual and symbol, Oxford University Press, New York.

Faust, B 1982, Women, sex and pornography, Penguin, London.

Fleet, JF 1881, ‘Sanskrit and Old Canarese inscriptions’, Indian Antiquary 10.

Foulston, Lynn 2002, At the feet of the goddess: the divine feminine in local Hindu

religion, Sussex Academic Press, Brighton.

Francfort, Henri-Paul 1992, ‘Dungeons and dragons: reflections on the system of

iconography in Protohistoric Bactria and Margiana’ in Possehl, Gregory (ed),

South Asian archaeology studies, Oxford & IBH Publishing, New Delhi.

—— 1994, ‘The Central Asian dimension of the symbolic system in Bactria and

Margiana’, Antiquity 68(259).

Freed, Stanley A and Ruth S Freed 1998, Hindu festivals in a North Indian village

(Anthropological papers of the American Museum of Natural History, no 81),

University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Führer, Alois 1897, Monograph on Buddha Sakyamumi’s birth place in the Nepalese

Tarai (Archaeological Survey of India, new imperial series 26, Northern India,

6), Allahabad.

Gail, AJ and GJ Mevissen (eds) 1993, South Asian archaeology, Stuttgart, GJR

Verlag.

Gaṇeśa Purāṇa 1892, Gopal Narayan & Sons, Bombay.

George, E 1992, ‘A background to the uneven development amongst the women of

one caste in Western Saurashtra’, Unpublished MA Prelim, Latrobe University.

—— 2004, The Sorathiya Rabari: women’s instrumentality in the culture of a

pastoral caste, Unpublished PhD thesis, Latrobe University, Bundoora.

214 the iconic female

Ghadavi, LP 1983, Cāraṇa ni Asmita, Jamnagar (Gujarati).

Ghosh, A (ed) 1989, An encyclopaedia of Indian archaeology, 2 vols, Munshiram

Manoharlal, Delhi.

Ghosh, Avijit 2004, ‘Catch me if you can’, The Telegraph 23 May, www.

telegraphindia.com, accessed 24 February 2007.

Gimbutas, Marija 1974, The gods and goddesses of Old Europe 7000 to 3500 BC:

myths, legends and cult images, University of California Press, Berkeley.

—— 1999, The living goddesses, University of California Press, Berkeley.

—— 2001a, The language of the goddess, Thames & Hudson, London.

—— 2001b, The living goddesses (edited and supplemented by Miriam Robbins

Dexter), University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London.

Giri, Gitu 2003, Art and architecture remains in the Western Terai region of Nepal,

Droit Publishers, Delhi.

Goldman, Robert P 1999, ‘God in hiding: the Mahābhārata’s Virāṭa Parvan and

the divinity of the Indian epic hero’, Purāṇa XLI/2:95–131.

Guha, R 1985, ‘The career of an anti-god in heaven and on earth’ in Mitra, Ashok

(ed), The truth unites: essays in tribute to Samar Sen, Subarna Rekha, Calcutta.

Gupta, Swarajya Prakash 1980, The roots of Indian art, BR Publishing, Delhi.

Gyatso, Janet 1998, Apparitions of the self: the secret autobiographies of a Tibetan

visionary, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Hall, Fitz-Edward 1859, ‘The Śrīsūkta or litany to fortune’, Journal of the Asiatic

Society of Bengal 28.

Hamilton, Jennifer 1998, ‘Reclaiming the goddess: feminist spirituality and the

use of symbols’ in Casey, M, D Donlon, J Hope and S Wellfare (eds), Redefining

archaeology: feminist perspectives, ANH Publications, The Australian National

University, Canberra.

Hancock, M 1995, ‘The dilemmas of domesticity: possession and devotional

experience among urban Smārta women’ in Harlan L and P Courtright (eds),

From the margins of Hindu marriage: essays on gender, religion and culture,

Oxford University Press, New York.

Harcourt, MV 1993, ‘The Deshnoke “Karni Mata” temple and political legitimacy

in medieval Rajasthan’ South Asia 16 (supplement 1).

Harlan, L 2003, The Goddesses’ henchmen, Oxford University Press, New York.

Harper, EB 1959, ‘A Hindu village pantheon’, Southwestern Journal of

Anthropology 15(3).

Hawley, John S 1996, ‘Prologue’ in Hawley, John S and Donna M Wulff (eds)

Devī: goddesses of India, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles,

and London.

bibliography 215

Heesterman, JC 1962, ‘Vrātya and sacrifice’, Indo-Iranian Journal 6(1).

Hermann-Pfandt, Adelheid 1990, Ḍākinīs: zur Stellung und Symbolik des

Weiblichen in tantrischen Buddhismus, Indica et Tibetica Verlag, Bonn.

—— 1992–3, ‘Ḍākinīs in Indo-Tibetan Tantric Buddhism: Some Results of Recent

Research’, Studies in Central and East Asian Religions 5/6.

Hiltebeitel, Alf 1981, ‘Draupadī’s hair’ in Biardeau, Madeleine (ed), Autour de la

déesse hindoue, Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris.

Hobsbawm, Eric 1983, ‘Introduction: inventing traditions’ in Hobsbawm, Eric and

Terence Ranger (eds), The invention of tradition, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Hodder, Ian 1986, Reading the past, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

—— 1993, ‘Social cognition’, Cambridge Archaeological Journal 3(2).

—— 1998, ‘The goddess and leopard’s den: conflicting interpretations at

Çatalhoyuk’ in Casey, M, D Donlon, J Hope and S Wellfare (eds) Redefining

archaeology: feminist perspectives, ANH Publications, The Australian National

University, Canberra.

—— 1999, The archaeological process: an introduction, Blackwell Publishers,

Malden.

Humes, Cynthia Ann 1996, ‘Vindhyavāsinī: local goddess yet great goddess’

in Hawley, JS and DM Wulff (eds), Devī goddesses of India, University of

California Press, Berkeley.

—— 2005, ‘Wrestling with Kālī: South Asian and British constructions

of the Dark Goddess’ in McDermott, Rachel Fell and Jeffrey J Kripal

(eds), Encountering Kālī: in the margins, at the center, in the West, Motilal

Banarsidass, Delhi.

Insoll, Timothy 2004, Archaeology, ritual, religion, Routledge, London, New York.

Jamkhedkar, AP 2004, ‘Symbols, images and rituals of the mother in Vakātaka

period’, Lalit Kala 30.

Janssen, Frans HPM 1991, ‘On the origin and development of the so-called

Lajjāgaurī’ in Gail, AJ, and GJR Mevissen (eds), South Asian Archaeology, FS

Verlag, Stuttgart.

Jarrige, Catherine 1984, ‘Terracotta human figurines from Nindowari’ in Allchin,

Bridget (ed), South Asian archaeology 1981, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Jarrige, Jean-Francois 2000, ‘Mehrgarh Neolithic: new excavations’ in Taddei,

Maurizio and Giuseppe De Marco (eds), South Asian Archaeology 1997, Istituto

Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente, Rome.

Jayakar, Pupul 1989, The Earth Mother, Penguin, New Delhi.

Joshi, NP 1986, Mātṛkās: Mothers in Kuṣāna art, Kanak Publications, New Delhi.

216 the iconic female

Jung, CG 1938, ‘Psychological aspects of the mother archetype’ in Jung, CG,

The archetypes and the collective unconscious, RFC Hull (trans), Princeton UP,

Princeton.

Kakar, Sudhir 1991, The analyst and the mystic, University of Chicago Press,

Chicago.

—— 1996, The Indian psyche, Oxford University Press, Delhi.

Kalff, Martin 1979, Selected chapters from the Abhidhānottara-Tantra: the union

of female and male deities, Unpublished PhD thesis, Columbia University, New

York.

Kathuria, RP 1987, Life in the courts of Rajasthan, New Delhi.

Kelkar, Kamal 2002, Vidharbhātīla Prācīna Mūrtī [Old sculptures in Vidharbha],

Shri Mangesha Prakashan, Nagpur.

Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark 1993, ‘Socio-ritual artifacts of Upper Paleolithic huntergatherers

in South Asia’ in Possehl, Gregory (ed), South Asian archaeology

studies, Oxford & IBH Publishing, New Delhi.

—— 2000, Ancient cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, American Institute of

Pakistan Studies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York.

Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark, JD Clark, JN Pal and GR Sharma 1983, ‘An Upper

Palaeolithic shrine in India?’, Antiquity 57(220).

Khan, Gulzar Muhammad 1973, ‘Excavations at Zarif Karuna’, Pakistan

Archaeology 9.

Khergamker, Gajanan 2006, ‘Goddess of the sea polices over Kolaba cop station’,

Downtown plus Times of India 26 June.

Kinsley, David 1986, Hindu goddesses: visions of the divine feminine in the Hindu

religious tradition, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles,

London.

Kolff, DHA 1990, Naukar, Rajput and Sepoy: the ethno-history of the military

labour market in Hindustan, 1450–1850, Cambridge University Press.

Kosambi, Damodar Dharmanand 1962, Myth and reality: studies in the formation

of Indian culture, Popular Prakashan, Bombay.

Kovacs, Anja 2004, ‘You don’t understand, we are at war! Refashioning Durga in

the service of Hindu nationalism’, Contemporary South Asia 13(4).

Kramrisch, Stella 1956, ‘An image of Aditi Uttanapad’, Artibus Asiae 19.

Kun dga’ grol mchog 1982, ‘Nag po spyod pa’i rtogs pa brjod pa’i yal ’dab’ in The

Autobiographies of Jo-nang Kun-dga’ grol mchog and his Previous Embodiments,

Tibet House Publishers, New Delhi.

Kūrma Purāṇa 1972, (edited and translated into English by AS Gupta et al),

Kashiraj Trust, Varanasi.

bibliography 217

Kurtz, Stanley 1992, All the mothers are one: Hindu India and the cultural

reshaping of psychoanalysis, Columbia University Press, New York

Lalye PG 1973, Studies in Devāī Bhāgavata, Popular Prakashan, Bombay.

Lele-Trymbakkar, Ganesha Shastri 1964, Trīthayātrāprabandha (2nd edn),

Deshmukh Prakashan, Pune.

Lerner, Martin and Steven Kossak 1991, The lotus transcendent. Indian and

Southeast Asian art from the Samuel Eilenberg Collection, Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York.

Lohuizen-de Leeuw, Johanna Engelberta van 1972, ‘Gandhara and Mathura:

their cultural relationship’ in Pal Pratapaditya (ed), Aspects of Indian art, Brill,

Leiden.

Mabbett, IW 2006, ‘L’indologie de Paul Mus: sociologie ou cosmologie?’ in

Chandler, DP and C Goscha (eds), Paul Mus (1902–1969): L’espace d’un

regard, Les Indes savantes, Paris.

Mackay, Ernest 1931, ‘Household objects, tools and implements’ in Marshall, John

H (ed), Mohenjodaro and the Indus Civilization, Arthur Probsthain, London.

—— 1948, Early Indus Civilization, Luzac, London.

Mackenzie Brown, C 1991, The triumph of the Goddess: the canonical models and

theological visions of the Devībhāgavata Purāṇa, State University of New York

Press, Albany.

Maddock, P 2006, ‘Mammai Mataji: a contemporary Indian great goddess,’

Fieldwork in religion, 2(2).

Mahadik, Krishnaswami A (ed) 1952, Śarabhendra bhūpālakṛta tristhalī yātrecyā

lāvṇyā aṇi Śarabhendra tīrthāvaḷi, Saraswati Mahal Granthalaya (Marathi).

Malcolm, J 1832, A memoir of Central India, London.

Mankad, BL 1939, ‘Rabaris of Kathiawar (a social study)’, Journal of the

University of Bombay 7(4).

Marglin, FA 1985, Wives of the god-king: the rituals of the devadasis of Puri,

Oxford University Press, Delhi.

Marshall, John H 1931, ‘Religion’ in Marshall, John H (ed), Mohenjodaro and the

Indus Civilization, Arthur Probsthain, London.

—— 1951, Taxila, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Maula, Erkka 1984, ‘The calendar stones from Moenjo Daro’ in Jansen, Michael

and Gunter Urban (eds), Interim reports vol. 1: Reports on field work carried out

at Mohenjo-Daro, Pakistan 1982–83 by the IsMEO-Aachen University Mission,

RWTH/IsMEO, Aachen, Rome.

McDermott, Rachel Fell and Jeffrey J Kripal (eds), Encountering Kālī: In the

margins, at the center, in the West, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

218 the iconic female

Mehta, Rustam J 1976, Masterpieces of Indian sculpture, Taraporwala and Sons,

Bombay.

Menzies, Jackie 2006, ‘Concept of the goddess’ in Menzies, Jackie (ed), Goddess

divine energy, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney.

Meskell, Lynn 1998, ‘That’s capital M, capital G’ in Casey, M, D Donlon, J Hope

and S Wellfare (eds), Redefining archaeology: feminist perspectives, ANH

Publications, The Australian National University, Canberra.

Mishra, Tara Nanda 1996, ‘The archaeological activities in Lumbini’, Ancient

Nepal 139.

Mishra, V 1998, Devotional poetics and the Indian sublime, State University of

New York Press, Albany.

Misra, Baba and Pradeep Mohanty 2002, ‘Headless contour in the art tradition

of Orissa, Eastern India’, Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and

Research Institute 62–63.

Mitra, Debala 1972, Excavations at Tilaura-Kot and Kodan and explorations in the

Nepalese Terai, Department of Archaeology, Kathmandu.

Mode, Heinz 1960, L’antica India (translated by G Gentili and L Petech), Le

Grandi Civiltà del Passato, Editrice Primato, Rome.

Moffat, Michael 1979, An Untouchable community in South India: structure and

consensus, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ.

Monier-Williams, Monier 1986, A Sanskrit–English dictionary, Motilal

Banarasidass, New Delhi (originally published by Oxford University Press,

1899).

—— 1993, Sanskrit–English Dictionary, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Mukherji, Purna Chandra 1901, A report on a tour of exploration of the antiquities

in the Tarai, Nepal, the Region of Kapilavastu; during February and March

1899, with a prefatory note by Vincent A Smith (Archaeological Survey of India,

imperial series 26, part I), Calcutta.

Murray, MA 1934, ‘Female fertility figures’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological

Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 44.

Narasimhaswami, HK 1952, ‘Nagarjunakonda image inscription’, Epigraphica

Indica 29 (5).

Nasim Khan, M 2002, ‘Lajjāgaurī seals and related antiquities from Kashmir

Smast-Gandhāra’, Journal of the Society for South Indian Studies 18(8).

—— 2003, ‘Kashmir Smast (Gandhara) and its religious significance: study based

on epigraphic and other antiquities from the site’ in Franke-Vogt, Ute, and

Hans-Joachim Weisshaar (eds), South Asian Archeology, LindenSoft Verlag,

Aachen.

Nath, Amarendra 1990, ‘Lajjā Gaurī and her possible genesis’, Lalit Kala 25.

bibliography 219

Nelson, Sarah Milledge 1997, Gender in archaeology: analyzing power and

prestige, AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek.

O’Flaherty, WD 1981, ‘The shifting balance of power in the marriage of Śiva and

Pārvatī’ in Hawley J, and D Wulff (eds), The divine consort: Rādhā and the

goddesses of India, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley.

Obeyesekere, Gananath 1984, The cult of the goddess Pattini, University of

Chicago Press, Chicago.

Obeyesekere, Gananath 1990, The work of culture: symbolic transformation in

psychoanalysis and anthropology, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Parpola, Asko 1994, Deciphering the Indus script, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

—— 1995, ‘The problem of the Aryans and the Soma: textual-linguistic and

archaeological evidence’ in Erdosy George (ed), The Indo-Aryans of Ancient

South Asia: language, material culture and ethnicity, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin,

New York.

—— 2002, ‘Pre-proto-Iranians of Afghanistan as initiators of śākta tantrism: on

the Scythian/Saka affiliation of the Dāsas, Nuristanis and Magadhans’, Iranica

Antiqua 37.

Paul, K 1993, ‘Negotiating sacred space: the Mandir and the Oran as contested

sites,’ South Asia 16(supplement 1).

—— 1995, Constituting Cāraṇa, unpublished PhD thesis, Anthropology Dept

Sydney University.

Piggott, Stuart 1950, Prehistoric India, Penguin, Harmondsworth.

Pintchman, Tracy 1994, The rise of the goddess in the Hindu tradition, State

University of New York Press, Albany.

Possehl, Gregory L 2002, The Indus Civilization: a contemporary perspective,

Vistaar, New Delhi.

Poster, Amy J 1986, From Indian earth: 4,000 years of terracotta art, Brooklyn

Museum, New York.

Prabhudesai, PK 1968, Ādiśaktīce viṣvasvarūpa (Devikośa), Tilak Maharashtra

Vidyapeeth, Pune (Marathi).

Radcliffe-Bolon, Carol 1997 (1992), Forms of the goddess Lajja Gauri in Indian

art, Motilal Banarasidass, Delhi.

Raghavan, V 1956, ‘Variety and integration in the pattern of Indian culture’, Far

Eastern Quarterly 15.

Raghunathji 1900, The Hindu temples of Bombay, Fort Printing Press, Bombay

(Reprinted in 2004 by Mumbai philanthropist and scholar, Phiroze Ranade.)

220 the iconic female

Raheja, Gloria and Ann Gold 1994, Listen to the heron’s words: reimagining

gender and kinship in North India, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los

Angeles, London.

Ramanujan, AK 1973, Speaking of Śiva, Penguin, Harmondsworth.

—— 1986 ‘Two realms of Kannada folklore’ in Blackburn, SH and AK

Ramanujan (eds), Another harmony: new essays on the folklore of India, OUP,

Delhi.

Rao, Vidya 1990, ‘Thumri as feminine voice’, Economic and Political Weekly 28

April.

Renfrew, Colin 1994, ‘The archaeology of religion’ in Renfrew, Colin and Ezra

BW Zubrow (eds), The Ancient mind: elements of cognitive archaeology,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Renfrew, Colin and Paul Bahn 1991, Archaeology, theories, methods and practice,

Thames and Hudson, London.

Rijal, Babu Krishna 1996, 100 years of archaeological research in Lumbini,

Kapilavastu and Devadaha, with the reprint of ‘A report on a tour of exploration

of the antiquities in the Tarai, Nepal (1901)’ by PC Mukherji, SK International

Publishing House, Kathmandu.

Roberts, Gregory David 2004, Shantaram, Scribe Publishers, Melbourne.

Roerich, George 1959, Biography of Dharmasvāmin, Chag lo-tsā-ba Chos-rjedpal,

A Tibetan monk pilgrim, KP Jayaswal Research Institute, Patna.

Rolland, Pierre 1973, ‘Le Mahavrata. Contribution à l’étude d’un rituel solonnnel

védique’, Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Gottingen,

Philologisch-Historische Klasse.

Rosaldo, M 1980, Knowledge and passion: Ilongot notions of self and social life,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Roscoe, Will 1996, ‘Priests of the goddess: gender transgression in ancient

religion’, History of Religions 35(3).

Sanderson, Alexis 1985, ‘The category of purity and power among the Brahmins

of Kashmir’ in Carrithers, M, S Collins and S Lukes (eds), The category of

the person: anthropology, philosophy, history, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

—— 1988, ‘Śaivism and the tantric traditions’ in Sutherland, S, L Houlden, P

Clarke and F Hardy (eds), The World’s Religions, Routledge, London.

—— 1995, ‘Meaning in tantric ritual’ in Blondeau, AM and K Schipper (eds),

Essais sur le rituel III: colloque du centenaire de la section des sciences

religieuses de l'Ecole pratique des hautes études, Peeters, Louvain-Paris,

Sangari, K 1990, ‘Mirabai and the spiritual economy of bhakti’, Economic and

Political Weekly 7 July.

bibliography 221

Sankalia, HD 1960, ‘The nude goddess or “shameless woman” in Western Asia,

India, and South Eastern Asia’, Artibus Asiae 23(2).

Sankalia, Hasmukh Dhirajlal, Shantaram Bhalachandra Deo and Zainuddin

Dawood Ansari 1971, Chalcolithic Navdatoli: The excavations at Navdatoli

1957–59, University of Baroda Press, Poona, Baroda.

Sarohamāhātmya, included in Vāmana Purāṇa 1968.

Sax, WS 1991, Mountain goddess: gender and politics in a Himalayan pilgrimage,

Oxford University Press, New York.

Schopen, Gregory 1997, ‘Archaeology and Protestant presuppositions in the study

of Indian Buddhism’ in Bones, stones, and Buddhist monks: collected papers on

the archaeology, epigraphy, and texts of monastic Buddhism in India, University

of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

Sen, Amartya 2005, The argumentative Indian, Penguin, London.

Shanks, Michael and Christopher Tilley 1987a, Re-constructing archaeology,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

—— 1987b, Social theory and archaeology, Polity Press, Cambridge.

—— 1989, ‘Archaeology into the 1990s’, Norwegian Archaeological Review 22(1).

Shastri, Hariprasad 1982, Lokayata and Vratya, Firma KL Mukhopadhyay,

Calcutta.

Shastri, JL (ed) 1983, Manusmṛti, with the Sanskrit commentary

Manvarthamuktāvali of Kullūka Bhaṭṭa, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Shering, MA 1881, The castes and tribes of Rajasthan, London.

Shulman, David 1980, Tamil temple myths, Princeton University Press, Princeton

NJ.

—— 1984,‘Die Integration der hinduistischen Kultur durch die Brahmanen,

"Große", "mittlere" und "kleine" Versionen des Parasurama-Mythos’,

in Schluchter, Wolfgang (ed), Max Webers Studien über Hinduismus und

Buddhismus. Interpretation und Kritik, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt .

Silburn, Lilian 1983, La kuṇḍalinī, l’énergie des profondeurs. Les Deux Océans,

Paris.

Simmer-Brown, Judith 2002, Ḍākinī’s warm breath: the feminine principle in

Tibetan Buddhism, Shambhala, Boston.

Sinha, Amita 2006, ‘Cultural landscape of Pavagadh: the abode of Mother

Goddess Kalika’, Journal of Cultural Geography 23(2).

Sjöö, Monica and Barbara Mor 1991, The great cosmic mother: rediscovering the

religion of the Earth, Harper, San Francisco.

Sohan Dan Cāraṇa 1987, Interviews with Professor Sohan Dan Cāraṇa, Hindi

Deparment, University of Jodhpur, February 1987.

222 the iconic female

Sonawane, VH 1988, ‘Some remarkable sculptures of Lajja Gauri from Gujarat’,

Lalit Kala 23.

Srinivas, MN 1952, Religion and society among the Coorgs of South India,

Clarendon, Oxford.

Srivastava, Mahesh Chandra Prasad 1979, Mother goddess in Indian art,

archaeology and literature, Agam Kala Prakashan, Delhi.

Staal, JF 1963, ‘Sanskrit and Sanskritization’, Journal of Asian Studies 22(3).

Stern, H 1971, ‘Power in traditional India: territory, caste and kinship. A study of

the Rajasthan region’ in Fox, R (ed), Kin, clan, raja and rule: state–hinterland

relations in pre-industrial India, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Stoller, P 1989, The taste of ethnographic things: the senses in anthropology,

University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

Stutley, Margaret 1985, Hinduism, The Antiquarian Press, Wellingborough.

Sukhthankar (ed) 1942, Mahabharata (Bombay edition) vol 3 Bhandarkar,

Oriental Institute, Poona.

Tambs-Lyche, Harald 1999, ‘Introduction’ in Tambs-Lyche, Harald (ed), The

feminine sacred in South Asia, Manohar, New Delhi.

—— 2004, The feminine sacred in South Asia, Manohar, Delhi.

Tāranātha, 1985a, ‘bKa' babs bdun ldan gyi brgyud pa'i rnam thar ngo mtshar

rmad du byung ba rin po che'i lta bu'i rgyan’ in Namgyal, C and T Taru (eds),

The collected works of Jo-Nang Tāranātha Vol 16, Smanrtsis Shesrig Dpemzod,

Leh.

—— 1985b, ‘Slob dpon chen po spyod ’chang dbang po’i rnam par thar pa ngo

mtshar snyan pa’i sgra dbyangs’ in Namgyal, C and T Taru (eds), The collected

works of Jo-Nang Tāranātha Vol 12, Smanrtsis Shesrig Dpemzod, Leh.

—— 1987, ‘Grub chen Buddha gupta’i rnam thar rje btsun nyid kyi zhal lung las

gzhan du rang rtog gi dri mas ma sbags pa’i yi ge yang dag pa’o’ in Namgyal, C

and T Taru (eds), The collected works of Jo-Nang Tāranātha Vol 17, Smanrtsis

Shesrig Dpemzod, Leh.

Templeman, David 1983, The seven instruction lineages by Jo Nang Tāranātha,

Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala.

—— 1989, Tāranātha’s Life of Kṛṣṇācārya/Kāṇha, Library of Tibetan Works and

Archives, Dharamsala.

—— 1992–3, ‘A narrative account of a Gaṇacakra, and the fulfillment of

Guhyasamāja through Cakrasaṃvara’, Studies in Central and East Asian

Religions 5/6.

—— 1994, ‘Reflexive criticism: the case of Kun dga’ grol mchog and Tāranātha’

in Kvaerne, Per (ed), Tibetan studies: proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the

bibliography 223

International Association for Tibetan Studies, The Institute for Comparative

Research in Human Culture, Oslo.

—— 2002, ‘Iranian themes in Tibetan tantric culture: the ḍākinī’ in Blezer, Henk

(ed), Religion and secular culture in Tibet, Tibetan studies II, EJ Brill, Leiden.

Thapar, Romila 1963, Aśoka and the decline of the Maurya, Oxford University

Press, Oxford.

—— 1984, From lineage to state: social formations in the mid-First Millennium BC

in the Ganga Valley, Oxford University Press, Delhi.

—— 2002, ‘The Rgveda encapsulating social change’ in Pannikar, KN, Terence L

Byres and Utsa Patnaik, The making of history, Anthem, London.

Tiwari, JN 1985, Goddess cults in Ancient India, Sundeep Prakashan, Delhi.

Tiwari, Sudarshan Raj 1996, ‘Mayadevi temple: recent discoveries and its

implications on history of building at Lumbini’, Tribhuvan University Journal 19.

Tod, J 1987, Annals and antiquities of Rajasthan, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Townsend, Joan B 1990, ‘The goddess: fact fallacy and revitalization movement’

in Hurtado, Larry W (ed), Goddesses in religions and modern debate Scholars

Press, Atlanta.

Trigger, Bruce G 1989, A history of archaeological thought, Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge.

Tripathi, Vibha and K Srivastava Ajeet 1994, The Indus terracottas, Sharada

Publishing House, Delhi.

Turner, V 1974, Dramas, fields and metaphors: symbolic action in human society,

Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY.

U rgyan Ghuru n.d. U rgyan Ghuru Padma ’byung gnas kyi skyes rabs rnam

par thar pa rgyas par bkod pa padma bka’i thang yig, Shes rig par khang,

Dharamsala.

Ujwal, KS Dan 1972, Bhagwati Shri Karṇīji Maharaj, Jaipur.

Urban, Hugh B 2003, Tantra: sex, secrecy, politics and power in the study of

religion, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Urban, Hugh B 2005, ‘India’s darkest heart: Kālī in the colonial imagination’ in

McDermott, Rachel Fell and Jeffrey J Kripal (eds), Encountering Kālī: in the

margins, at the center, in the West, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Vāmana Purāṇa 1968, (edited and translated into English by AS Gupta et al),

Kashiraj Trust, Varanasi.

Van Buitenen, JAB (ed and trans) 1975, The Mahābhārata: the book of the forest,

Chicago University Press, Chicago.

Verardi, Giovanni 1996, ‘Religions, rituals, and the heaviness of Indian history’,

Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale di Napoli 56(2).

224 the iconic female

—— 2003, ‘Images of destruction. an enquiry into Hindu icons in their relation

to Buddhism’ in Buddhist Asia 1, Papers from the First Conference of Buddhist

Studies held in Naples in May 2001, Italian School of East Asian Studies, Kyoto

2003.

Verhoeven, Marc 2002, ‘Ritual and ideology in the pre-pottery Neolithic B of the

Levant and Southeast Anatolia’, Cambridge Archaeological Journal 12(2).

Vicziany, Marika 2007, ‘Understanding the 1993 Mumbai bombings: madrassahs

and the hierarchy of terror’, South Asia 30(1).

Vicziany, Marika and Jayant Bapat 2008, ‘Mumbādevī and the other mother

goddesses in Mumbai’, Modern Asian Studies, Cambridge University Press

(43)1.

Vidal, D 1997, Violence and truth: A Rajasthani kingdom confronts colonial

authority, Oxford University Press, Delhi.

Wadley, Susan S 1977, ‘Women and the Hindu tradition’ in Jacobson, D and Susan

S Wadley (eds), Women in India: two perspectives, South Asia Books, Columbia

MO.

Warhaft, Sally 2003, Fishing in the City of Gold: an ethnography of the Koḷīs of

Mumbai, PhD thesis, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Australia.

White, David Gordon 2003, Kiss of the yoginī: tantric sex in its South Asian

contexts, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

Wilson, HH (ed and trans) 1961, The Vishnu Purāṇa: a system of Hindu mythology

and tradition, Punthi Pustak, Calcutta.

Winkelmann, Sylvia 2000, ‘Some new ideas about the possible origin of the

anthropomorphic and semi-human-creature depictions on Harappan seals’ in

Taddei Maurizio and Giuseppe De Marco (eds), South Asian Archaeology 1997,

Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente, Rome.

Witzel, Michael 1995, ‘Early Indian history: linguistic and textual parameters’ in

Erdosy, George (ed), The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: language, material

culture and ethnicity, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York.

Wood, Juliette 1996, ‘The concept of the goddess’ in Billington, Sandra and

Miranda Green (eds), The concept of the goddess, Routledge, London, New

York.

Ziegler, NP 1976, ‘Marwari historical chronicles: sources for the social and

cultural history of Rajasthan’, Indian Economic and Social History Review

12(2).

Zla ba seng ge (ed) 1997, Grub chen U rgyan pa’i rnam par thar pa byin rlabs

kyi chu rgyun, Vol 32 of series, Gangs can rig mdzod, Bod ljongs bod yig dpe

rnying dpe skrun khang, Tibet Autonomous Region

Unknown nexus between AAP and The Hindus comes out in the open

Unknown nexus between AAP and The Hindus comes out in the open![N Ram and his wife donations to AAP]()

![Information about TNQ books and journals private limited]()

A fact-finding team of UNESCO has informed the Madras High Court that the lacunae in temple conservation work by the state government in Tamil Nadu has badly affected some of the most historic shrines, which include two near Chennai, reported

A fact-finding team of UNESCO has informed the Madras High Court that the lacunae in temple conservation work by the state government in Tamil Nadu has badly affected some of the most historic shrines, which include two near Chennai, reported

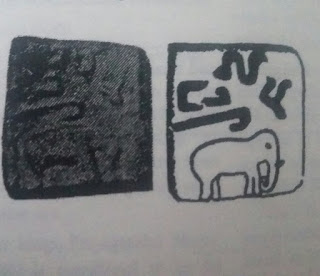

Fronting the elephant on the Kalabhra coin is a ladder. I suggest that both elephant and ladder are Indus Script hypertexts. It appears that the ladder is topped by 'srivatsa' hypertext which has been deciphered elsewhere as dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Fronting the elephant on the Kalabhra coin is a ladder. I suggest that both elephant and ladder are Indus Script hypertexts. It appears that the ladder is topped by 'srivatsa' hypertext which has been deciphered elsewhere as dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Blacksmithing mother.

Blacksmithing mother.

harappa.com "Slide 88. Three objects (harappa.com)

harappa.com "Slide 88. Three objects (harappa.com)

Dancing girl, Mohenjodaro. Hypertext with comparable hieroglyph on potsherd, Bhirrana. Dance step is the signifier hieroglyph.

Dancing girl, Mohenjodaro. Hypertext with comparable hieroglyph on potsherd, Bhirrana. Dance step is the signifier hieroglyph. Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.

Seal. Indus Script.

Seal. Indus Script. Indus Valley Civilization Terracotta Fertility Goddess. Pakistan/Western India. 3500-2500 BCE

Indus Valley Civilization Terracotta Fertility Goddess. Pakistan/Western India. 3500-2500 BCE S

S Busts. Indus Valley.

Busts. Indus Valley.  Nausharo.

Nausharo.

This clay figure of a woman has a headdress, with flowers and what look like baskets. Maybe the 'baskets' were for burning oil?

This clay figure of a woman has a headdress, with flowers and what look like baskets. Maybe the 'baskets' were for burning oil? These little seated figures of men were found at Harappa.

These little seated figures of men were found at Harappa.

SC tells Karti: Appear before CBI

SC tells Karti: Appear before CBI

Nindowari seal with squirrel hieroglyph.

Nindowari seal with squirrel hieroglyph.