![]()

An oval furnace with a hub in the middle for keeping the crucible where artisans kept the copper ingots before fashioning them into artefacts. The furnace has holes for aeration and for inserting tuyeres to work up the flames. Photo:V.V. KRISHNAN

The star discovery of the year at 4MSR, the Archaeological Survey of India's site in Rajasthan, was this oval-shaped furnace lined with mud bricks. It was in furnaces such as these that the laborious process of making copper artefacts began. The furnace was used to smelt copper from the copper ore. It had a hole for inserting the tuyere for fanning the flame and holes on its sides for aeration. Beside the furnace is an anvil

where the sheeted ore was hammered into ingots. Photo:T.S. Subramanian

![]()

Sanjay Kumar Manjul, ASI’s director of excavation, studying storage jars adjacent to furnaces build on brick platforms. Photo: V.V. Krishnan

In 4MSR, trench after trench threw up furnaces and hearths in different shapes, clearly indicating that it was a thriving industrial centre. The picture shows a long, oval-shaped furnace and a circular furnace built on a mud-brick platform. Photo:V.V. KRISHNAN

A circular hearth with charcoal pieces and ash. Harappans made beads out of steatite, agate, carnelian, lapis lazuli, and so on here. Photo:T.S. SUBRAMANIAN

A yoni-shaped furnace found at 4MSR. Photo:T.S. SUBRAMANIAN

This terracotta vessel with a pronounced knob at the centre has engaged the attention of archaeologists as a "unique find" and is probably used in rituals or ceremonies. Similar vessels have been depicted on Harappan seals and copper plates. Photo:ASI

The copper plate with the engraving of the knobbed ceremonial vessel similar to the one found in the 2017 round of excavations. Photo:VASANT SHINDE

At the ASI's 43GB site, Sanjay Kumar Manjul (right) and K. Rajan, professor of history, Pondicherry University. Photo:V.V. KRISHNAN

An inverted pot, probably of the Mature Harappan period, found in situ in a trench at 4MSR. Photo:V.V. KRISHNAN

A portion of the enclosure wall that has been excavated in different areas around the mound. The wall, made of mud bricks, is thought to run around the settlement, and this one is in the south-east corner. Photo:ASI

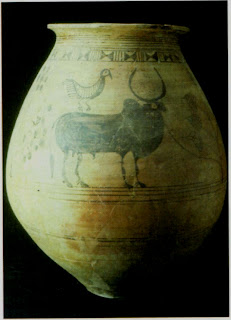

A painted vase that was probably baked in one of the many kilns at the 4MSR site, which also yielded baked pots, storage jars, perforated jars, beakers and so on. Photo:ASI

A painted terracotta pot. Photo:ASI

A view of the sunset from the mound at 4MSR surrounded by wheat fields. Photo:T.S. SUBRAMANIAN

Harappan beakers for measuring liquids. Photo: V.V. KRISHNAN

Boards announcing the names of 4MSR village near Bijnor. 4MSR is, as the crow flies, 7 km from the border with Pakistan. After Partition, Rajasthan Irrigation Department officials gave names such as 4MSR, 43GB and 86GB to newly created settlements for refugees from across the border. Photo:T.S. SUBRAMANIAN

The ASI's Arvin Manjul (third from left), co-director of the excavation at 4MSR, 43GB and 68/2GB, and other archaeologists examine a human skeleton found in the trench at 68/2GB. Photo:ASI

On the mound at 43GB around 50 km from 4MSR. Unlike 4MSR, the mound is heavily built up with houses and other structures, making excavation a real challenge. People of the Mature Harappan period settled on a big sand dune at 43GB, which became a mound after they abandoned it. Photo: T.S. SUBRAMANIAN

The trial trench at 68/2GB near 4MSR. It yielded Early Harappan ceramics, beads made of semi-precious stones, terracotta bangles and pestles. Photo:ASI

Gold rings, pieces and foils found in the 2017 excavations testified to the fact that the 4MSR Harappans made gold products too. They sourced gold from present-day Karnataka. Photo:ASI

The seal with a perfectly carved figure of a unicorn-it has been scooped out with precision on a thin slate of white steatlite-belongs to the Mature Harappan period. The ceremonial vessel in front of the unicorn is a puzzle. The seal has one Harappan sign on top and other signs that seem to have been scraped off. It has a perfectly made knob with a hole on the reverse and is a good example of seals of the Mature Harappan period. Photo:ASI

Seven different seals were found at 4MSR in the 2017 round of excavations and they provided insights into the gradual development in the production of seals. The seal with triangular designs and a crudely made knob, with a hole through which to string a thread, belongs to the transitional phase between the Early Harappan and Mature Harappan phases. Photo:ASI

Seven different seals were found at 4MSR in the 2017 round of excavations and they provided insights into the gradual development in the production of seals. The triangular seal with three concentric circles and no motifs on the other side belongs to the Early Harappan phase (c.3000 BCE-2600 BCE). Photo:ASI

Arrowheads, spearheads, celts and fish hooks, all made of copper, were found in the trenches at 4MSR, affirming to the industrial nature of the site. Archaeologists found copper bangles, rings, beads, and so on. Photo:ASI

Hundreds of oblong (popular qamong archaeologists as idli-shaped), triangular terracotta cakes have been found at 4MSR and the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi in Haryana, 340 km away. While the oblong cakes were used to retain heat in domestic hearths and chulas for keeping milk and water warm, the painted triangular cakes were embedded as decorative pieces on walls and floors of houses. Photo:ASI

Humped bulls, made of terracotta, found in the trenches at 4MSR. Photo:ASI

The shell of a tortoise in one of the trenches. Two such shells were found in different trenches along with charred bones, indicating that the Harappans consumed tortoise meat. Photo:ASI

The latest round of the Archaeological Survey of India’s excavations at 4MSR in Rajasthan gives valuable insights into how the Harappans made the transition from an agricultural society into an industrial one. By T.S. SUBRAMANIAN

A CIRCULAR flat-bottomed terracotta vessel with a pronounced knob at the centre is among the artefacts that are engaging the attention of archaeologists at 4MSR, a Harappan site about 10 kilometres from Anupgarh town in Rajasthan. They found not one but two such vessels, but in the second one the knob had broken off. “This is a unique find,” says Sanjay Kumar Manjul, director of the excavation for the 2017 field season, the third so far, at 4MSR. (No one seems to know what 4MSR stands for.) “It is probably a ritualistic vessel. Similar type of pot depictions have been found on seals from Harappan sites in India and Pakistan,” he added. The vessel has been depicted on Harappan seals, placed in front of a unicorn, and on copper plates along with a seated “yogi” with a horned headdress. Manjul, who is also Director of the Institute of Archaeology, the academic wing of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), New Delhi, and other scholars make intelligent guesses that it may be a ritual/ceremonial vessel, an incense burner, or a massive dish that is placed on a stand.

The bowl takes pride of place in the huge tent pitched on the dry bed of the Ghaggar river near 4MSR that houses all artefacts excavated at the site. Another exciting find was two tortoise shells amid charred bones of the tortoises. This suggested that tortoises formed an important part of the food of the Harappans who lived at 4MSR about 5,000 years ago.

Among the artefacts discovered were seals; fragments of gold foils and gold beads; miniature beakers probably used for measuring liquids; painted pottery; perforated jars; goblets and storage pots; beads made of steatite, agate, jasper, carnelian, lapis lazuli, and other semi-precious stones; earrings; fish hooks; spear-heads and arrowheads made of copper; bangles made of conch shells; and terracotta figurines. The trenches also yielded hundreds of terracotta cakes in shapes that ranged from oblong (popular among archaeologists as idli-shaped) to triangle and similar to a clenched fist (mushtika). They also yielded 10 pieces of weights made of banded chert stones.

But the most important discovery this year was a massive wall built of mud bricks stacked to a width of 8 metres, in the south-eastern corner of the excavation mound. The wall showed clear evidence of having been built during two successive phases of the Harappan civilisation, and it turns right at one point perhaps indicating that it could have run around the settlement, thus demolishing the assumption that 4MSR did not have a fortification or enclosure wall. In fact, the remains of the wall have been found on the western and northern sides of the mound.

K. Rajan, professor of history, Pondicherry University, who gave a series of lectures to students of the Institute of Archaeology at the site, confirmed that it was an enclosure wall, a feature found in many Harappan sites. The paleo-channels of the Ghaggar river were just 500 metres away from the site, to the north and the south. The wall could have been built to prevent flooding of the site. While fortification/enclosure walls at Harappan sites in Gujarat were made of stones, as one travelled towards Mohenjo-daro or Harappa (both in Pakistan now) they began to be made of burnt bricks. In Rajasthan, the walls, be they at 4MSR or Kalibangan, were built of mud bricks that were made with fine clay, which gave the bricks a fine texture, that is, they had been well levigated, as Disha Ahluwalia, a superviser at 4MSR, explained.

Besides the wall, the lower levels of this Harappan industrial complex showed evidence of streets having been there, belying the assumption that the settlement had no organised streets.

Industrial secrets

The trenches excavated in 2015, 2016 and 2017 revealed the industrial secrets of 4MSR, which lasted from circa 4000 BCE to circa 2000 BCE through what is called the Early Harappan (3000-2600 BCE) and the Mature Harappan (2600-2000 BCE) phases. Possibly the Late Harappan phase settlements may also be visible. At the time Frontline visited the mound in March, more than 15 trenches, each 10 metre x 10 metre, had been dug jointly by students of the Institute of Archaeology and archaeologists of the Excavation Branch-II of the ASI. Arvin Manjul, Superintending Archaeologist, Excavation Branch-II was the co-director of the excavation.

The mound itself offered a spectacular sight, with trench upon trench bristling with furnaces, hearths and kilns that confirmed the industrial nature of the site. The furnaces, hearths and kilns were situated on mud-brick platforms at various levels and presented insights into the activity during the various periods. Close to the furnaces and hearths were big storage pots, twin pots and broken perforated jars. Beads lay scattered on a few furnace floors. In the kilns, there were terracotta beads and broken terracotta bangles. This year’s excavation threw up furnaces and hearths of different shapes: oval, circular, yoni-shaped and even a squarish one.

One of the trenches had a big, oval-shaped furnace lined with mud bricks. It had a short mud-brick wall, with the inner side of the bricks blackened from the searing heat of the furnace and the furnace floor rammed with mud. The furnace had a hole for blowing air into it with tuyeres to fan the flames. There was a central hub too for placing crucibles in which to smelt copper from the copper ore. “This furnace was for extracting copper from the copper ore. It was periodically plastered. That meant it was used for a long time,” Manjul said.

In a furnace in a nearby trench, copper ingots recovered from the copper ore in the previous furnace had been converted into workable pieces. This furnace had a passage for blowing air with bellows and charcoal pieces were found strewn on the furnace floor. An anvil was found nearby, which was obviously the place where the copper ingots were beaten into workable pieces. There was also a channel for bringing fresh water that the smiths used for strengthening the workable pieces.

In the third furnace, the Harappan artisans converted the copper ingots into tools and artefacts Manjul summed up the process: “The first furnace was probably for smelting copper from the ore. Here, high temperature was required. In the second, normal temperature was required because the smiths had already made copper. In the third, the artisans made a variety of copper artefacts such as bangles, beads, rings, fish hooks, arrowheads, spear heads, and so on.”

In one trench was a big, circular kiln, with potsherds lying on its floor. There were white patches on the floor, which had apparently resulted from the intense heat worked up in the kiln. Explaining the difference between a furnace and a kiln, Rajan said: “If you are working a metal like copper, it is called a furnace. If you are firing/baking ceramic products, it is called a kiln.” It is in these kilns that the Harappans fired a variety of pottery, including storage pots, big jars, perforated jars, goblets, beakers, dish-on-stands and terracotta figurines.

With such a variety of furnaces, hearths and kilns, it was not surprising that Manjul called 4MSR “an important industrial settlement” that is “at present the only example in the Harappan context which shows a major industrial activity”. The series of furnaces in trench after trench and at different levels indicated that multiple artisans had worked simultaneously and that the site had been occupied continuously and industrial activity was also continuous, he said. There were many sites of a similar nature in the vicinity. Manjul added: “The region was a major industrial hub. There is no doubt about it. These varieties of artefacts cannot be consumed here itself. This was one of the industrial centres that catered to urban settlements such as Kalibangan, Rakhigari and Ganweriwala.”

Indeed, the three seasons of excavation have provided a tremendous insight into how 4MSR evolved from an agricultural settlement into a major industrial centre that manufactured copper artefacts, beads from semi-precious stones and a wide variety of terracotta products and exported them to Harappan sites nearby and far away.

Manjul said: “In the lower levels [of trenches], there is evidence of agriculture because there are domestic hearths within residential complexes. In the transitional phase from Early Harappan to Mature Harappan, there are furnaces within house complexes. Later, during the Mature Harappan phase, there was a complete transformation into an industrial site. Thus, there was a gradual transformation from agriculture to industry.”

The third season of excavation at 4MSR had a clear objective: to understand the nature of the industrial activity that had been observed during the second field season in 2016. Manjul said: “In this season, we have some clear evidence of copper smelting, melting and craftsmen working on the metal. Along with that, we have excavated anvils, storage jars, dish-on-stand, etc. We have found copper slag, terracotta crucibles and terracotta moulds and finished copper artefacts such as fish-hooks, spearheads, arrowheads, beads, copper strings, copper rings and bangles. It was observed that the entire process of copper working, from smelting to making finished products, was done here. This site revealed manufacturing of artefacts from steatite. In the smaller hearths, along with steatite we noticed charcoal and ash.

“The industrial activity started during the transitional stage from the Early Harappan phase to the Mature Harappan stage. Full-fledged industrial activity took place during the Mature Harappan stage and the late Mature Harappan phase.” Shubha Majumdar, Deputy Superintending Archaeologist, ASI, said that at least four major structural phases were noticed during the Mature Harappan phase.

There were signs of agricultural activity in the lower levels of the trenches because the weather at that point of time was conducive to farming. When the weather changed for the worse, the region became semi-arid. “So people switched over from agriculture to industrial activity to sustain themselves,” Manjul said.

What facilitated the change to industrial activity in a big way was the availability of copper ore, possibly from the Khetri belt situated about 150 km away, in Rajasthan. Similarly, gypsum, which was used in the flooring of homes, was available in the nearby area, while steatite, which was used for making beads, was available in plenty within a 200 sq km area. On the other had, lapis lazuli, gold, shell and semi-precious stones were not available nearby, and artefacts made from them showed clear evidence of 4MSR’s linkage with distant shores and contemporary settlements, Manjul said.

The Harappans at 4MSR exploited a variety of stones available in the Aravalli hill range for making pestles, mortars and anvils. Chert stones were available in the Rohri hills in Pakistan. The artisans made both small and big chert blades. The chert blades were used for manifold purposes, including skinning of animals and making sickles. The Harappans also fashioned modular chert blades for making different tools, besides tools of copper, bones, antlers and stone. Stone-hammers were made with a wooden handle. In the early stages of development, the Harappans made tools by driving the stone inside the wood. In subsequent stages, they drove the wood inside metal for they had learnt the art of metal working.

The settlement pattern 10 to 20 km around 4MSR showed that there were separate Early Harappan sites, Mature Harappan sites and sites with the late phase of the Mature Harappan civilisation. “After that, in this same region, we had painted grey ware (PGW) settlements, and they continued up to post-Gupta period followed by the Rang Mahal culture. This is the complete cultural sequence of this area,” Manjul said.

Seals

Another important feature of the latest round of excavation is the discovery of seven seals, which confirmed that 4MSR belonged to the Early Harappan, then transitional and the Mature Harappan phases.The seal that belonged to the transitional phase has a geometric design on the one side and a little knob on the other side. Since it has a knob on the obverse side, it could have been used to stamp the geometric pattern on a piece of clay tied to a bag to signal that duty had been paid on the goods kept in the bag. Of the two seals that belong to the Mature Harappan phase, one had the engraving of a unicorn with a ceremonial vessel in front of it. There is a Harappan sign above the unicorn. There were more Harappan characters, but they had been scraped off. This seal showed superb workmanship because the artisan had not merely carved the unicorn on the tiny steatite slab but had unerringly scooped out the outline of the entire animal within the narrow confines of the seal.

This seal has a knob on the obverse with a hole in it for a string to pass through. Perhaps, the owner of the seal wore it around his neck. Another seal portrays a unicorn, but the seal’s top portion is broken off. It was found embedded in the mud and the impression of the unicorn can still be seen on the mud.

Animal treasures

What excited the archaeologists was the discovery of two tortoise shells amid charred remains of tortoises. Vijay Sathe, a professor in the Deccan College Post-graduate and Research Institute, Pune, who studied the tortoise shells, antlers and other animal remains, said: “This site has a good representation of skeletal evidence of animals. They include cattle, sheep, goat, antelope and similar small-sized mammalian fauna. The inhabitants of 4MSR used a good blend of wild and domesticated animals for food and farming. An interesting thing noticed here was the inhabitants’ preference for animals such as tortoise and fish. The presence of a couple of varieties of tortoises was noticed in the form of their carapace and their charred bones, which are potential indicators of the food habits of the inhabitants. That is, they roasted and consumed the tortoise. Besides tortoises, the remains of a variety of freshwater fish have been found in charred condition.”

If one were to look at the composition of both wild and domesticated animals that the Harappans of 4MSR ate, it appears that a variety of animals, especially small-sized animals, such as chinkara, antelope and barking deer, besides cattle, goat and sheep, did have their share in their food economy, Sathe said. The science of archaeo-zoology had important role in archaeology, he added. Once a detailed analysis was completed, it would be possible to talk about the animal population found around 4MSR, the contribution of the cattle to agricultural and other practices and the attitude of the Harappans towards these animals as a whole.

COMMENTS:

A new Harappan site

The discovery and excavation of a new site, 4MSR, near Binjor, Rajasthan, may yield vital clues about the evolution and continuity of the mature and late phases of the Harappan civilisation and their relationship to the painted grey ware culture that followed. By T.S. SUBRAMANIAN

A seal made of steatite stone found in one of the trenches in 4MSR. It is a sure sign that the site belongs to the Mature Harappan phase. The seal has the carving of a unicorn standing in front of an incense burner and five Harappan characters on the top part.

A view of the mounds at the 4MSR site near Binjor.

Sanjay Kumar Manjul, Director of the Institute of Archaeology and also Director of Excavation at 4MSR, examining a painted pot. Manjul is a specialist in ceramics.

A perforated pot found in a trench. A rare feature of the site is that a perforated jar, a perforated pot and a perforated bowl have been found, all telltale signs a Mature Harappan culture.

A.K. Pandey, Deputy Director of Excavation, points to the mud-brick structures and a pestle in a trench. The trench also yielded ovens and hearths. At right is a silo lined with mud for storing grains.

A view of the trench with rooms made of mud bricks.

A view of the trenches, which have revealed mud-brick structures, silos for storing grains, and ovens and hearths.

A trench full of pots, jars and other ceramics. It was perhaps a storehouse for grains.

A razor blade (left) and a broken celt, both made of copper. Harappan culture belonged to the Bronze Age.

A variety of beads found at the site, which yielded evidence of industrial activity to make beads from semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli, carnelian, faience, agate and steatite.

A chert blade. Such blades were used for skinning hunted animals.

Painted terracota pottery.

A perforated bowl, with a hole at the bottom, a rare occurence in Harappan sites.

A potsherd with a painted flower.

A potsherd with a painting of a lion or an animal belonging to the cat family.

Ceramics, includinga painted pot with a handle, another rarity.

Copper rings.

A terracota figurine of a humped bull.

Fabric marks on a piece of clay. Spindle whorls have been found, indicating that the residents there knew how to weave fine fabrics.

The impression of a seal on clay, indicating that tax had been paid on goods. This confirms that the site had trade with other Harappan settlements.

A part of a gold ear ornament. It is rare to find gold ornaments at Harappan sites. However, gold tubular beads have been found at Khirsara and Lothal, both in Gujarat.

A cubicular weight made of chert stone.

The fire altar, with a yasti made of an octagonal brick.

An idli-shaped terracota cake that retained heat and was used to keep milk warm for children in winter.

The skeleton of a woman, about 40 years old. The ASI archaeologists are identifying the grave goods in the trench to determine whether the skeleton belongs to the Early Harappan, Mature Harappan or a later period.

Students of the Institute of Archaeology, New Delhi, and staff of the ASI taking part in the excavation at 4MSR. In the back row, A.K. Pandey is seen showing an instrument used in the excavation. On his left is Sanjay Kumar Manjul.

SEVEN kilometres from the small town of Anupgarh in Rajasthan, as our taxi was speeding on the road, we spotted the board we were looking for. It simply said “4MSR”. Nobody seems to know what “MSR” stands for. The local people say names like these are given to villages by the Irrigation Department. Houses in the village have spacious, open courtyards where tractors are parked, or cattle are chewing hay in the late afternoon sun. One kilometre from the village, a fascinating site greets us: big tents on four corners of a level ground which is actually the dry bed of the Ghaggar river. At the centre is a badminton court. At the entrance to the bivouac is the tent for security personnel, and it has a bell—a piece of iron railing—hanging next to it. The tent we enter is a spacious one and has a white screen on one side and several rows of chairs in front of it—obviously a classroom.

“To welcome you, we excavated a seal just yesterday. It is made of steatite.” A.K. Pandey, Deputy Director of the excavation at the Harappan site of 4MSR, told the Frontlineteam. Along with Pandey, who is also the Superintending Archaeologist, Excavation Branch-II, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), New Delhi, were the staff of the ASI and the students of the Institute of Archaeology, New Delhi, affiliated to the ASI. “It is a square seal, having the figure of a unicorn. Five Harappan letters are incised on its upper part. The seal shows that the people of 4MSR had trade with other areas,” he said.

The site, which is a couple of kilometres from Binjor village, is in Anupgarh tehsil of Sri Ganganagar district, Rajasthan. It is just 7 km from the India-Pakistan border as the crow flies. The archaeologists and the students are excavating a big mound in the alluvial plains of the Ghaggar river. Ghaggar is the modern name given to the Saraswati river. The village residents call the mound Thed and it is about 400 metres from the camp.

There was a swirl of activity on the mound, where 10 trenches have been excavated, each measuring 10 by 10 metres, with four quadrants. Women from 4MSR were sieving the sand dug up from the trench, hoping to find tiny beads or seals. In the pottery yard, more women were sorting out different types of pottery. Behind the pottery yard, Hardeep Singh, a carpenter, was giving the finishing touches to a scabbard he had made while Mangla Ram, an ironsmith, was working up the flames in a chula and sharpening the tools needed for the excavation. Sometimes, Hardeep Singh becomes the ironsmith and Mangla Ram the carpenter.

Sanjay Kumar Manjul, Director, the Institute of Archaeology and head of the excavation at 4MSR, came straight to the topic. “It is natural to ask why there was a need to excavate at 4MSR when so many Harappan sites situated in the Ghaggar river valley have been excavated and reports published on them,” he said. In the Ghaggar river valley itself, he pointed out, explorations and excavations had been done in several sites by archaeologists such as L.P. Tessitore (1916-17), Aurel Stein (1940-41), Amalananda Ghosh, Katy Dalal and others. These sites included Kalibangan, excavated by B.B. Lal, B.K. Thapar and J.P. Joshi, over nine field seasons from 1961 to 1969; 46 GB and Binjor 2, 3 and 4, all situated within a few kilometres of 4MSR and excavated by Amalananda Ghosh; Binjor 1, excavated by Dalal; Rakhigarhi, excavated by Amarendra Nath (1997-2000) and Vasant Shinde (2014 and 2015); and Baror (2003-06), excavated by Urmila Sant and T.J. Baidya.

Manjul explained: “The purpose of the present excavation at 4MSR is to learn about the Early Harappan deposits, 4MSR’s relationship with other contemporary sites and to fill the gap between the Late Harappan phase and the painted grey ware [PGW] culture. We should know about the early farming phase [that existed in the pre-Harappan period]. It is also important to know the continuity of the sequence from the Late Harappan phase to the PGW culture. That is why we have taken up explorations and excavations in this entire area.”

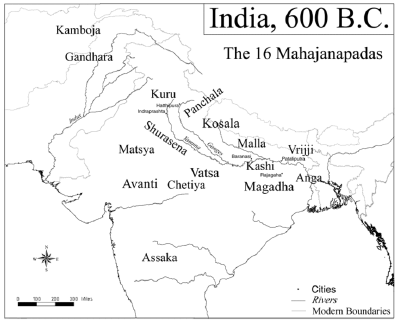

At its height, the Harappan civilisation flourished over 2.5 million sq. km in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. About 2,000 sites have been found, from Sutkagendor in the Makran coast of Balochistan to Alamgirhpur in the east in Uttar Pradesh and from Manda in Jammu to Daimabad in Maharashtra.

The Harappan civilisation is divided into three phases: Early (3000 BCE-2600 BCE), Mature (2600 BCE -1900 BCE) and Late (1900 BCE-1500 BCE). The PGW culture came later and is datable to circa 1200 BCE and belongs to the early historical period.

After Partition, big Harappan sites such as Mohenjo-daro, Harappa and Ganweriwala fell on the Pakistani side. Between 1972 and 1974, M.R. Mughal, former Director General of Archaeology and Museums, Pakistan, explored Bahawalpur in the Cholistan region of Punjab, situated on the border with Rajasthan. Mughal found a lot of pottery on the surface there and named it Hakra ware after the Hakra river which flows there and which is called Ghaggar in India. Originating in the Himalayas, the Ghaggar flows through Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Gujarat before joining the Arabian Sea near the Rann of Kutch.

If the cornucopia of artefacts thrown up from the current excavation is any indication, 4MSR has all the characteristics of having been an Early Harappan and Mature Harappan site like Kalibangan situated 120 km away. There are no indications that a Late Harappan phase existed. “A special feature of 4MSR is the discovery of a perforated jar, a perforated bowl with a hole at the bottom and a perforated pot, confirming its status as a Mature Harappan site,” asserted Pandey. What fascinated him was the discovery of pots with handles. “In a nutshell, our excavations have yielded pre-Harappan Hakra ware, Early Harappan pottery and Mature Harappan ceramics,” he said.

What stands out in the excavation is the bonanza of Early Harappan pottery with beautifully painted figures of peacocks, a lion, birds, pipal leaves and fish-net designs. Another discovery, a beautiful pot with a pencil mouth, could have been used to keep precious liquids or perfume.

Other important artefacts obtained from the site are beads made of carnelian, lapis lazuli, steatite, agate and terracotta; copper, shell and terracotta bangles; copper rings and fish hooks; terracotta spindles and whorls; weights made out chert stone; terracotta sling balls, toy-cart frames, figurines of humped bulls, and arrowheads. Two horns of nilgai were found in a trench. Of particular interest is a potsherd with the impression of a fabric. Besides the seal, a sealing (impression of a seal) was found. The centrepiece of the discoveries is a fragment of a gold ornament for the ear. It is rare to find gold ornaments in Harappan sites although tubular gold beads have been found in Khirsara and Lothal, both Harappan sites in Gujarat.

One trench yielded a skeleton, perhaps that of a female, about 40 years old. The ASI team is in the process of identifying the presence of grave goods in the trench to determine the period to which it belongs.

What has come as a bonus is the discovery of a fire altar, with a yasti (a shaft) in the middle. “The yasti is an indication that rituals were performed at the altar,” said Manjul. The yasti here is an octagonal, burnt brick. Although bones were found in the upper level of the deposits in this trench, it could not be ascertained whether they were sacrificial bones. The ASI team traced mud and ash layers at the lower level in the trench and also found a bead inside the fire altar. Pandey said fire altars had been found in Kalibangan and Rakhigarhi, and the yastis were octagonal or cylindrical bricks. There were “signatures” indicating that worship of some kind had taken place at the fire altar here.

Rakhigarhi Rediscovered

According to Manjul, an important reason why so many Harappan settlements came up in the then Saraswati valley was its fertile alluvial plains. Besides, raw materials such as chert, clay and copper were available in the nearby areas.

It was puzzling, Manjul said, that while a lot of pottery belonging to the Mature Harappan period was found at Kalibangan, Baror, Binjor and 4MSR, no pottery belonging to the Late Harappan phase had been found in these and other nearby sites. “The Harappans deserted 4MSR, Binjor and Baror after the Mature Harappan phase. Why?” he asked. Another puzzle was that only the Late Harappan culture existed in the Suratgarh region in Rajasthan. “There is no continuity of the Harappan phases in the Ghaggar river valley. Did a migration take place towards Suratgarh after the Mature Harappan period? We have to find out the reasons why it happened,” Manjul said. (Baror, Binjor and 4MSR are contiguous sites. While Baror is about 20 km from Binjor and 4MSR, Kalibangan is 120 km from 4MSR. Kalibangan is 25 km from Suratgarh).

Again, there was no continuity between the Late Harappan phase and the PGW culture. To find out whether there was any continuity between the Late Harappan phase and the PGW culture, the ASI and the Institute of Archaeology excavated a trial trench in March 2015 in a mound called 86 GB, less than 2 km from 4MSR. There are several sites with PGW deposits within 20 km of 4MSR. “It is important to understand both the cultures, the Late Harappan and the PGW cultures, which are in independent horizons along the Ghaggar river,” Manjul said.

It was ASI Director General Rakesh Tewari and former Joint Director General R.S. Bisht who suggested that the ASI excavate Binjor again, where earlier Amalananda Ghosh and Katy Dalal had dug up several mounds. This led to the Excavation Branch-II, ASI, and the Institute of Archaeology taking up a joint excavation at 4MSR. “If an excavation is done again at Binjor [4MSR], we can combine the results of the excavation done in Cholistan by M.R. Mughal and the excavations here,” Bisht said.

So, when Pandey and his colleagues surveyed Binjor in September 2014, they discovered Thed. “We thought it had been discovered earlier by either [Amalananda] Ghosh or [Katy] Dalal, but nowhere has it been mentioned in the records. Ghosh had mentioned four mounds named Binjor 1, 2, 3 and 4. This mound is not one of them. This is different. This was discovered by me, Ambily C.S. and Vinay Kumar, both assistant archaeologists of the ASI,” Pandey said. On the top of the mound is the grave of Peer Baba, a Muslim holy man who is worshipped by Hindus and Sikhs.

When the excavation began in January 2015, ASI archaeologists found that a lot of waste material had been dumped on the summit of the mound by the local people and the Army, which had camped there soon after Partition. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise because the dump had protected the mound. But modern farming activity had reduced the mound’s size because farmers had cut away its sloping fringes to reclaim land for farming. So, the mound that exists now is only half its original size. Farmers have built a long concrete trough for storing water and laid water channels around the mound to water the wheat fields. In February, when Frontline visited the area, all around the mound were vast stretches of wheat fields in bloom. Indeed, for 100 km from Kalibangan to 4MSR, wheat fields, watered by the aquifers of the Ghaggar river, stretch endlessly on either side of the road. Every trench has revealed structures such as walls and small rooms made of mud bricks. Most of the rooms have post holes, where posts stood more than 4,000 years ago to support the roof, or perhaps they held door jambs. The size of the mud bricks is in the ratio of 1:2:4, a typical Mature Harappan feature.

There are successive floor levels made of mud bricks, especially in the industrial area of the site. “It shows that whenever the original floor in which the Harappans were working got damaged, they built another floor over it. Between two floors, we have found a lot of ash, charcoal, bones, pottery and artefacts. There are katcha drains in some trenches,” Pandey said.

The trenches have thrown up remnants of ovens, hearths and furnaces, with white ash and soot embedded in the soil, testifying to the industrial activity of making beads at the site. Hearths were found both inside and outside the Harappan houses. Pandey offered an explanation: During winter, Harappans cooked inside their homes but in summer, they cooked outside. One trench revealed a deep silo, lined with mud, to store grains.

The number of idli-shaped terracotta cakes found in the ovens and hearths is incredible. “The presence of idli-shaped terracotta cakes in great numbers in ovens and hearths shows that they had a great role to play in baking many things,” Pandey said.

V. Muthukumar, assistant archaeologist with the ASI and a trench supervisor at the site, who is now a student of the Institute of Archaeology, explained that the idli-shaped terracotta cakes, heated by flaming charcoal, retained their heat for a long time. These hot terracotta cakes were kept in the oven at night to keep milk warm for children, he said. Hundreds of small riverine shells found in trenches “must have been used to clean pots”, Muthukumar said.

To reach the soil beneath the mound quickly, two trenches had been dug in the south-east and south-west corners. Since water channels ran close to these two trenches, their floors were wet and mud bricks found in these trenches had coagulated because of water seepage. The trench in the south-east corner had mud-brick structures and a “hara” for keeping cattle feed. “This was perhaps a cattle shed,” said Jigme Wangmo, a student who was at work there. Since the mud bricks had got fused, it would be difficult to say with certainty whether the bricks had been used for flooring or building a wall, said Siripuram Rushikesh, also a student.

Indeed, the credit for discovering the steatite seal that was shown to us on our arrival goes to Raj Kumar, a labourer who was working in quadrant three of trench N30 E10. Delighted, he showed it to the trench supervisor, Ambily C.S., who sprinted to show it to Pandey. It was in the same trench that she found the skeleton too.

What has gladdened Pandey is that the excavation has thrown up a variety of artefacts, confirming that 4MSR has all the traits of a Mature Harappan civilisation. These include a jar, a pot and a bowl, all perforated; jars for storage; black-on-red and plain red ceramics; goblets; beakers; dish-on-stand; pots with pencil mouths; a seal; a sealing; a cubicular weight made of chert stone; mud-brick structures; painted pottery with a variety of designs, and so on. Goblets have rims with lines incised at perfect intervals.

“The characteristics of the pottery of the Mature Harappan period are that they are made of well-baked clay and precisely decorated with paintings. Perfection is the hallmark of Mature Harappan ware,” Pandey said.

A remarkable feature is that a bonanza of ceramic assemblage belonging to the Early Harappan period has been found in the lower levels of the trenches. They are akin to the Hakra and Sothi ware of Pakistan, and the Kulli style of paintings of Afghanistan. “We also found plenty of Periano Ghundai [an archaeological mound in Balochistan, Pakistan] reserved slipware. Along with this, an exuberant amount of Kot Dijian [Kot Diji is an archaeological site in Sindh, Pakistan, considered a forerunner of the Harappan Civilisation] style of the painted pottery tradition of Pakistan has been found,” said Manjul. Periano Ghundai is in the Zhop valley of Pakistan. Pottery from this Early Harappan site has designs of peacocks, birds, a lion or perhaps an animal belonging to the cat family, a moustache design and bichrome floral designs, and they are similar to the Kot Diji ware. “The Kot Dijian style of ceramics, which consists of pots with everted, rounded, square and beaked rims, is prominent in the assemblage,” said Prabodh Shirvalkar, Assistant Professor of Archaeology, Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune. The pots are painted with black horizontal bands and wavy lines in panels. An important example, which shows the influence of the Kulli style of painting on ceramics, is the painting of the body portion of an animal belonging to the cat family. The animal has an elongated body and its hind limbs are curved inwards.

Manjul said: “The appearance of the Early Harappan period ceramic assemblage found at 4MSR is dominated by Hakra, Kot Dijian and Sothi elements. This is the first site in this region where so much of cultural mixing or amalgamation is available. This has helped in understanding the development of the Mature Harappan phase and its cultural process. In the transitional phase, there is a combination of Early and Mature Harappan pottery. The ceramic assemblage of Mature Harappan is dominated by black-on-red ware, plain red ware, perforated jars, pots and plates, globular pots and dish-on-stand, but there is a continuation of the early traditions. The gradual transformation from the Early Harappan to the Mature Harappan is very visible here.”

A bar seal found in one of the trenches at Kalibangan, an Early and Mature Harappan site. Photo:V.V. Krishnan dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic) karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNadhAra 'helmsman'. dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS bAra 'twelve' rebus: barae 'merchant'. Thus, metal castings merchant. dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS aḍar 'harrow' Rebus: aduru 'native metal' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS kamaTha 'bow and arrow' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner,coinage'. Thus, meta casting mint.

OUR plan was to visit the Harappan site of 4MSR in Rajasthan, where excavation is under way, by travelling by train from New Delhi to Sri Ganganagar and then driving down to 4MSR. When we told P.S. Sriraman, Superintending Archaeologist-in-charge, Jodhpur Circle, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), about our plans to visit 4MSR from Sri Ganganagar, he told us: “You have made a mistake. You should get down at Suratgarh railway station, which is 80 km beyond Sri Ganganagar and drive down from Suratgarh to 4MSR. Kalibangan lies on the way. Anyway, you have to cross Kalibangan to reach 4MSR. Do visit Kalibangan, which was a big Harappan site, which the ASI excavated from 1961 to 1969. We have a good site museum at Kalibangan.”

That was music to the Frontline team’s ears. Behind the spacious site museum of the ASI in Kalibangan lie three big rolling mounds which, in their innards, had concealed a big Harappan town that belonged to the Early Harappan period (3000 BCE–2600 BCE) and the Mature Harappan period (2600 BCE–1900 BCE). Pravin Singh, Assistant Archaeologist, ASI, Kalibangan, led us to the mounds. “You put your foot anywhere on the mounds, and you will trample on a prodigious amount of pottery,” he said. He knew the rolling, desolate mounds like the back of his hand. The entire Harappan town at Kalibangan was built of mud bricks, Pravin Singh stressed. He took us to the KLB-1 mound, which housed the citadel where the ruling elite lived and the KLB-2 mound where the lower town was built. (Kalibangan in the Rajasthani language means black bangles. Nearby is Pilibangan, which means blue bangles).

It was eerie visiting the greatly eroded mounds, with millions of potsherds, broken terracotta bangles, and idli-shaped terracotta cakes lying everywhere. Rows of Harappan bricks or terracotta drainpipes jutted out of the eroded mounds, giving us an insight into how the town would have been built with mud bricks more than 4,500 years ago.

Sriraman calls Kalibangan an important Harappan site and ranks it “on a par with Dholavira, Rakhigarhi and Lothal”. It was a site that belonged to both the Early Harappan and the Mature Harappan phases. It did not have a Late Harappan phase, he stressed.

“It was a typical Harappan settlement, with fortification walls, an upper town and a lower town,” Sriraman said.

Like 4MSR, situated about 120 km away, Kalibangan was built on the banks of the now-dry Ghaggar river. According to Michel Danino, a specialist in Harappan civilisation, Amalananda Ghosh, who became the ASI Director General in 1953, spent two winters in 1950 and 1951 exploring the valleys of Saraswati and Drishadvati rivers, as he called the Ghaggar and the Chautang rivers respectively, and identified the Harappan culture of Kalibangan in about December 1950. Professor B.B. Lal, B.K. Thapar and J.P. Joshi excavated the mounds for nine field seasons from 1961 to 1969.

The late B.K. Thapar, in his article entitled “Kalibangan, A Harappan Metropolis Beyond the Indus Valley”, says that “the excavations at Kalibangan brought to light the grid layout of a Harappan metropolis, perhaps truly ‘the first city’ of the Indian cultural heritage.” The significant part of the evidence from the excavation, according to Thapar, “relates to the discovery of a non-Harappan settlement immediately underlying the occupational remains of the Harappan citadel (KLB-1). Kalibangan thus became the fourth site, after Amri, Harappa and Kot Diji, all in Pakistan, where the existence of a preceding culture below that of the Harappan has been recognised.”

“An outstanding discovery” of the excavations at Kalibangan, Thapar said, was the discovery of a ploughed field, situated south-east of the settlement, outside the town wall. The ploughed field revealed a criss-cross pattern of furrows. The nine field seasons of excavation revealed a series of seven fire altars, residential buildings for the elite, drains and wells built with baked bricks, large quantities of beads, copper artefacts, and so on.

Sriraman said the ASI had plans to refurbish the site museum at Kalibangan, add more galleries displaying the artefacts found there and provide more facilities to tourists.

July 22, 2016

Harappan surprises

Excavations at the 4MSR site near Binjor in Rajasthan reveal an exclusive industrial production centre belonging to the Early Harappan and Mature Harappan phases. By T.S. SUBRAMANIAN

An aerial view of the Harappan industrial site of 4MSR near Binjor in Rajasthan.

This photograph, taken from a drone, shows the “key trench”, the main trenches on the mound, the grave of Peer Baba (which stands separately on the mound) and a concrete tank with water (partly seen) to irrigate the wheat fields that surround the mound at 4MSR.

Platforms made of mud bricks, at varying levels.

Some platforms at the site were separated by a gap of 170 cm. “It can be a corridor or a passage. It can be a separation of one house from the other,” said Mazumdar. Some workshops had small residential houses situated adjacent to them.

The rubble dumped on the mound by the Army after Partition in 1947 and later by villagers helped preserve the Harappan exotica for many years. But farmers have cut the sloping sides of the mound to reclaim more area for wheat cultivation. Worse, a concrete tank used for irrigation now stands close to the mound.

Circular and yoni-shaped (foreground) hearths in a trench. In the furnaces, Harappan artisans made beads, copper products and gold ornaments.

Platforms made of mud bricks, and oval- and circular-shaped hearths.

An ingeniously built furnace with a platform (right) for the smith to sit and blow the fire burning in a pit in front of it. Air from the blower resting in a depression abutting the platform ran through an underground pipe to the firepit. The molten metal collected in the hearth was cast by artisans into ingots.

Terracotta cakes of different shapes found in the trenches. While the disc-shaped cakes were used to maintain the temperature in hearths, the triangular- and the rectangular-shaped ones were used for decoration and flooring.

Hundreds of disc-shaped terracotta cakes have been found at 4 MSR during the excavations in 2015 and 2016.

Four of a series of circular hearths. The hearths, the furnaces and the artefacts confirm that 4MSR was a Harappan industrial site.

Excavations at the 4MSR site near Binjor in Rajasthan reveal an exclusive industrial production centre belonging to the Early Harappan and Mature Harappan phases. By T.S. SUBRAMANIAN

Updated: July 6, 2016 12:53 IST

AS far as Harappan sites go, it is the odd one out. The settlement had no fortification walls, no streets cutting at right angles, no citadel where the ruling elite lived, no middle town which housed the residences of traders and craftsmen and no warehouse—features that characterise Harappan settlements. Instead, it had all the trappings of a small, rural industrial production centre. This Harappan site, named 4MSR, is near Binjor village in Suratgarh district of Rajasthan and is believed to be 5,000 years old. It lasted for more than 1,100 years through what is called the Early Harappan (3000-2600 BCE) and the Mature Harappan (2600-1900 BCE) phases. It had no Late Harappan (1900-1500 BCE) phase.

Why Harappans abandoned the site at the peak of the Mature Harappan phase is not clear. Experts believe it could either be because of floods or because the land became arid. The site was situated between the two channels of the Ghaggar river.

The furnaces, hearths and structures made of mud bricks discovered in the 12 trenches dug by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) from January to March in a big mound surrounded by wheat fields at 4MSR were ample proof of a factory site with multipurpose workshops. The ash in the furnaces looked fresh 4,000 years after the site was abandoned!

One of the furnaces stood out for the ingenuity of its design. It had a platform for the smith to sit and blow the fire burning in a pit a short distance away. A tuyere (a tube or pipe through which air is blown into a furnace) ran through the earth from a scooped out depression, in which one end of the blower rested, to the firepit. Artisans sat here to smelt gold and copper from the ore and cast them into ingots. An anvil lay in another trench.

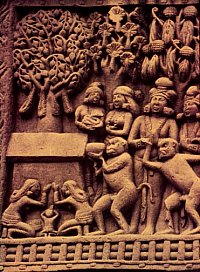

Adjacent to the furnaces were hearths, which were circular, oval or yoni-shaped, where craftsmen made exquisitely finished products in gold, such as earrings, beads, spacers and pendant frames, or stuff like rings, bangles, chisels, needles, fish hooks and spearheads in copper. A rare artefact unearthed from one of the trenches was a copper stylus with a thin gold foil wrapped around one end of it.

Beads in different shapes and designs made out of semi-precious stones such as carnelian, lapis lazuli, jasper, agate, steatite and amazonite were also produced in these workshops. Bangles and rings were made out of seashells and terracotta too. The assemblage of ceramic ware—S-shaped jars, perforated jars, storage pots, goblets, beakers, and black and redware—at 4MSR shows that the potters of the Early Harappan period were a creative lot.

Most of the artefacts, especially the beads, the copper ware and the gold ornaments, were traded in other Harappan sites. The weights, small and big, made from chert stone and seashells bear testimony to the long-distance trade links of the Harappans at 4MSR.

Rural settlement

“The usual plan of a Harappan settlement, which had a citadel, a middle town, a lower town and fortifications, is not traced here. This was a rural settlement,” said Sanjay Manjul, the director of the excavation at 4MSR. Manjul is the Director of the Institute of Archaeology, New Delhi, ASI’s academic wing, which offers a two-year postgraduate diploma in archaeology. It has been conducting the excavations at 4MSR jointly with the Excavation Branch-II of the ASI at Purana Qila, New Delhi. Students of Santiniketan, Kolkata; and Kumaon University, Uttarakhand; and the staff of the archaeology departments of Telangana and Assam also formed part of the excavation team.

Each of the 12 trenches dug in the second season this year measures 10 x 10 metres and has four quadrants of varying depths. “This site is important,” Manjul said, “to get a complete picture of the Harappan period and to understand the process of urbanisation at that time. Without studying a rural settlement, one cannot understand an urban settlement.”

‘A unique site’

R.S. Bisht, former Joint Director General, ASI, called it “a unique site” which “exclusively had a cluster of workshops for industrial activity right at the beginning of the pre-Harappan [also known as Early Harappan] period”. Bisht, who led 13 seasons of excavation of Harappan sites at Dholavira in Gujarat from 1990 to 2005, visited 4MSR both last year and this year.

He observed that 4MSR had “so many factories” and said: “I could not notice any street system. There were no lanes either. I saw so many fireplaces for the first time in a Harappan settlement.”

One other thing that fascinated Bisht was the discovery of a cluster of eight weights made out of banded chert stone, seashells (three) and sandstone. They weighed 0.25 grams, 0.46 g, 0.76 g, 2.26 g, 6.95 g, 13.68 g, 27.5 g and 52.10 g. The general ratio of the weights was 1:2. “So far, Dholavira is the only site which has yielded so many shell weights. It has not been reported from any other site that the Harappans were also using shell weights. But Binjor now has three shell weights,” he said.

Shubha Mazumdar, Deputy Superintending Archaeologist, Excavation Branch-II, ASI, said the importance of the site lay in its workshops. “The Harappans, depending on their capacity and economic conditions, built these kinds of workshops. They made finished products here and exported them to other sites,” he said.

The ASI team also discovered a large quantity of terracotta and shell bangles with ornamentation from the site. Some of them were of the conjoined variety, that is, twin bangles. “They were all made in hearths. In the bigger hearths, we found a lot of disc-shaped or triangular terracotta cakes,” Manjul said. Among the artefacts found at 4MSR, three stand out: a seal-cum-pendant made out of steatite with engravings of animals on both sides; a terracotta seal with three Harappan signs; and a terracotta figurine with a beak-like nose, hairdo, banded ornaments, and holes around the neck, which might have been for the inlay of semi-precious stones.

K. Rajan, Professor of History, Pondicherry University, and an accomplished field archaeologist, called his visit to 4MSR in March “one of the most rewarding academic experiences”. The 4MSR excavation was important on several counts, he said. Generally attention was paid to big Harappan sites such as Kalibangan, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi and others, he said. “We hardly concentrate on small settlements to understand the intricacies involved in the urbanisation of the Indus Valley civilisation. That way, Binjor is a unique Harappan settlement that provides the much-needed data on feeding [distribution] centres,” Rajan said.

Similarities, differencesIn what ways are this year’s excavation different from the one last year which yielded a vast assemblage of painted ceramic ware from the Early Harappan period? A Harappan seal, thousands of beads made from semi-precious stones, a gold ornament, hundreds of disc- and triangular-shaped terracotta cakes, a fire altar and the skeleton of a woman were found in the excavation at 4MSR in 2015 (“Harappan surprise”, Frontline, April 17, 2015).

“It was a limited excavation last year to know the cultural sequence and the nature of the site, the catchment area of nearby Late Harappan sites, and the sites that belonged to the painted greyware [PGW] culture and the black and redware [BRW] culture. These sites are situated all around 4MSR,” said Manjul. This year, the ASI team tried to understand the settlement pattern of the Harappans, and the horizontal plan of each stage of the Early Harappan and the Mature Harappan periods. So trenches were laid across the mound in the east-west and north-south directions.

The excavation last year, though limited in scale, prompted the ASI staff to assume that 4MSR was a factory site with several workshops. “This year’s excavation confirmed that 4MSR was indeed a factory site and the horizontal excavation revealed the plan of these multipurpose workshops with their furnaces, a series of hearths of different shapes and sizes and an anvil,” Manjul said.

“A lot of urban sites have been excavated. But rural, camp or factory sites have hardly been excavated in the Harappan context. This excavation has revealed a lot of furnaces, hearths and an anvil along with the raw materials that the artisans used in their workshops. So this site is important to understand a rural Harappan settlement. It came up sometime during the period of other Harappan sites such as Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Baror and Banawali,” he said.

Ingenious designThe multipurpose workshop complex had within it a small square tank ingeniously designed with wedge-shaped bricks to store water. In many Harappan sites, while structures such as platforms and residential houses were built with rectangular mud bricks (bricks made of clay and dried in the sun), the well was built with wedge-shaped burnt bricks.

![]()

A small tank made with wedge-shaped burnt bricks and the channel that carried water into it. The tank measured 130 cm x 130 cm on the outside. Harappan craftsmen used the water in the tank mainly for cooling the beads they made.

Layers of history

The key trench did not reveal any structural activity after the eighth layer. It was in the eighth layer that the ASI staff found the steatite seal-cum-pendant which carried the engravings of animals on both sides.

There were indications in the 10th and 11th layers that a flood had occurred. “This is river sand from the Ghaggar,” said Yathees Kumar, scooping out sand from the 11th level.

The trenches dug in the mound have seven layers, each layer revealing the history of a particular period. The top two layers form the rubble heap. Layers three and four, below them, are associated with the Mature Harappan period. “Layer four signifies the peak period of the Mature Harappan phase. Layer three depicts the end of the Mature Harappan phase.

There is no Late Harappan phase here,” said Mazumdar. Layer five forms the transitional phase between the Early Harappan phase and the Mature Harappan phase. Vestiges of the Early Harappan period are found in layers six and seven.

Bricks baked in kilns at a high temperature did not break easily. The tank in this case was made of two layers of wedge-shaped burnt bricks, with the floor level measuring 80 cm x 80 cm and the outer wall of the tank measuring 130 cm x 130 cm. Water reached the tank through a small channel on the floor.

“Water is sprinkled on the beads which get heated up when craftsmen drill holes in them. Besides, water is used for kneading the clay for the terracotta products and while bending products,” Shubha Mazumdar said.

There was “abundant evidence” of the abandonment of the site, and the ASI staff noticed flood deposits in the “key trench” in at least two stages, during the Early Harappan and the Mature Harappan phases, Manjul said. “The reason may be floods or a dry phase, which we will determine after the scientific analysis of the sediments,” he said.

The botanical remains from the trench will be sent to the Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleobotany, Lucknow, to find out what forced the Harappans to abandon the site after its Mature Harappan phase. The faunal remains are being studied by a multidisciplinary team from the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute in Pune, which is excavating the Harappan site at Rakhigarhi, and other institutions to understand the climatic conditions that prevailed at the site during its Early Harappan and Mature Harappan phases. “As a whole, the site shows the various stages of the Early Harappan and Mature Harappan periods. Mud-brick structures to house multipurpose workshops-cum-residential quarters were found there,” Manjul said.

Importantly, the ASI staff excavated what they call “a key trench” among the wheat fields, about 30 metres from where the slope of the mound ends. “The original mound would have extended beyond this key trench. The key trench was excavated to identify the original extent of the mound and unearth the cultural deposits there,” said V.P. Yathees Kumar, assistant archaeologist, ASI.

The ASI team dug this trench up to 11 layers. The villagers and the Army had disturbed the top six layers. So the top 80 cm did not yield any cultural deposit. The sixth layer yielded Early Harappan pottery. The rim of Early Harappan pottery was thin or featureless. That is, it did not turn inwards or outwards. The rim carried paintings.

Sanjay Manjul (second from left), director of the excavation at 4MSR, and his team members with a pot discovered from the site.

A student of the Institute of Archaeology, ASI, New Delhi, brushing a perfectly made pot.

A soak jar, with a terracotta pipe leading to it. Waste water produced after activities such as cooling of beads while drilling holes in them or washing of vessels and clothes was let into the soak jar. In Harappan settlements, these soak jars were often placed just outside the house, in drains on the street.

A copper ring.

A copper stylus with a gold foil at one end, and gold ornaments.

A terracotta seal with three Harappan signs showing two human figures on both sides of a jar with a double handle. It belongs to the Mature Harappan period. dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic) koDi 'flag' rebus: koD 'workshop'. Thus metal casting workshop. kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNaka 'scribe, account'.

A hammer, chisel and spearhead made out of copper found in the trenches.

Several gold bits found in the workshops.

A terracotta top.

A terracotta animal figure.

The trenches yielded a spectacular variety of pottery assemblage of the Mature Harappan period. They include S-shaped jars, perforated jars, goblets, dish-on-stand, cooking vessels, redware, black and redware, black on redware and greyware.

The layers belonging to the Early Harappan phase yielded dish-on-stand, a variety of goblets, beakers, pottery with bichrome paintings and some shards with polychrome designs. Toy carts and animal figures, especially those of bulls, were recovered from here. “The total cultural deposits of the site would be more than five metres,” said Manjul.

A rare human figurine with a beak-like nose and holes around the neck. The holes may have been for the inlay of semi-precious stones.

A seal-cum-pendant, made out of steatite

*śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ1]Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ?(CDIAL 12723) Rebus: guild master khāra, 'squirrel', rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri). *śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ1] Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ? (CDIAL 12723) Rebus: śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ] Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ,seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ.

khara Equus hemionus, 'Indian wild ass' Rebus: khAr ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri)

mlekh 'goat' rebus: milakkhu 'copper' mlecha ‘copper’

A seal-cum-pendant, made out of steatite.

A seal-cum-pendant, made out of steatite, found in the "key trench" at 4MSR. One one side are engravings of figures of a dog, a mongoose and, perhaps, a goat. On the other are the figures of a frog and a deer. The pendant belongs to the Early Harappan period (3000-2600 BCE). The pendant, with a knob-like projection at the top, had a hole too for a cord to pass through so that it could be worn around the neck [Credit: V. Vedachalam]

Hieroglyph: Kur. mūxā frog. Malt. múqe id. / Cf. Skt. mūkaka- id. (DEDR 5023) Rebus: mū̃h 'ingot'. muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'.

miṇḍā́l 'markhor' (CDIAL 10310) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet 'iron' (Munda.Ho.).med ‘copper’ (Slavic)

The seal-cum-pendant belongs to the Early Harappan phase. Carved on one side of it are a frog and a deer with horns. The other side has a mongoose, a dog and, perhaps, a goat. One cannot but admire the dexterity of the craftsman who carved the animals on both sides of the thin seal, 2.3 cm x 2.2 cm, without damaging it. “You can wear it as an amulet or a pendant. It is basically an amulet-seal without a script,” said Manjul.

Bisht said the discovery of this kind of steatite pendant from the pre-Harappan level was interesting. “It does not appear to be a seal. It appears to be a token, a kind of pendant. I doubt whether such a pendant has been reported from any site so far,” he said. It has a knob-like projection and a hole for a cord to pass through, which is unusual. “What is also unique is the depiction of five animals,” Bisht said.

A dabber used by Harappan potters to smoothen out the surfaces of pots or jars they made. To this day, potters everywhere, be it in villages in Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka or Gujarat, use the same kind of dabber. The tradition has continued for 5,000 years.

A furnace containing ash in an industrial shed. The ash looked fresh in the furnace that was perhaps last used 4,500 years ago.

KN Dikshit, 2013, Origin of early Harappan cultures in the Sarasvati Valley: Recent archaeological evidence and radiometric dates, Journal of Indian Ocean Archaeology No. 9, 2013, pp. 88 to 142 (Plates)

![]() Addorsed zebu, Rakhigarhi. dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magenetite, ferrite ore'. Thus magnetite casting. (After Fig. 69 in KN DIkshit opcit)

Addorsed zebu, Rakhigarhi. dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magenetite, ferrite ore'. Thus magnetite casting. (After Fig. 69 in KN DIkshit opcit)

The work at Binjor 4MSR was not only related to Soma SamsthA but indicate the work of seafaring merchants of Sarasvati Civilization who exported the metalwork products into Ancient Near East.

Revelations in History, Saturday, 13 June 2015 | Vaishnavi Singh

A terracota figurine of a humped bull.poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite, ferrite ore'.

The recent excavation of a modern village at Binjor in Rajasthan has revealed many artefacts dating back to Early and Mature Harappan phases. Vaishnavi Singh reports

A skeleton of a woman, aged 35-40 years, lying in a supine position facing north to south, terracotta spindles and whorls and weights made out of chert stone are few of the intriguing artefacts that were excavated from Binjor, an archeological site in the Ganganar district of Rajasthan, seven km east of the Indo-Pak border. What makes this site more interesting is the fact that it is one of the lesser known places of the ancient Harappan civilisation.

Few mysteries of the new-found artefacts were brought to light by AK Pandey, superintending archaeologist at the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), at a recent discussion. The artefacts are a result of the Phase II excavations at Binjor— 4MSR, which was carried out from January to April 2015 by the excavation branch (at Purana Qila) of the ASI.

The question that arose was why was there a need to excavate this new site when already so many Harappan excavations had been carried out in its near vicinity, in the Ghaggar valley itself. Pandey, also the deputy director of the excavation, explained, “The sole objective of this excavation at 4MSR is to learn about the early Harappan deposits, the sites’ relationship with other contemporary sites and to draw a cultural sequence with the late Harappan phase. If the copious amount of artefacts recovered from Binjor are any indication, then the site belongs to the early Harappan (c. 3000 - 2700 BCE) and the mature Harappan period (c. 2600 - 2000 BCE), much like the Kalibangan site which is 120 km away. This will help in the formation of a sequence and will lead to continuity, and so it becomes imperative to take up explorations in this entire area.”

A mound, known as Thed among the villagers, was found in the Ghaggar river basin, the modern name given to the Saraswati river. “We had earlier dug six trenches on the mound, but the number was increased to 12 trenches of 10 by 10 metres with four quadrants,” he added. In its glorious days, the Harappan civilisation flourished over two million sq km, from Sutkagendor on the Makran coast of Balochistan to Alamgirhpur in Uttar Pradesh, and from Manda in Jammu to Daimabad in Maharashtra.

What interested Pandey was the discovery of a jar, a bowl with a hole at the bottom and a perforated pot. “These confirm that the excavations belong to the mature Harappan period,” he informed us. The unearthing of pots with handles is another thing which fascinated him. He added, “We also uncovered a steatite seal with a hole on the back depicting a mythical animal with a single horn, like a unicorn as found in other Harappan seals, and a short inscription of five letters in the Indus script.” The excavations also lead to the discovery of houses made of standardised size of mud bricks (7.5 by 15 by 30 cm) in a ratio of 1:2:4. Huge quantities of ash and molten metal were also found indicating to metallurgical industrial activities that may have been carried out when the civilisation flourished. A common feature of the mature Harappan phase of large scale structural activities is also suggested through the excavations.

He also spoke about other artefacts which were unearthed at the site including beads made of carnelian, steatite, copper, terracotta bangles and cakes; copper rings and fish hooks; terracotta spindles and whorls; weights made out of chert stone, terracotta sling balls, toy cart frames, figurines of humped bulls, copper arrowheads and terracotta pipes. “Apart from all this we also found gold beads which are very rare to come across in these excavations. One trench also yielded the skeleton of a woman, aged 35-40 years lying in a supine position facing north to south. No burial woods were found on the site and we are still in the process of ascertaining the exact time period to which this body belongs to,” he added.

What has come as a surprise in these excavations is the discovery of a yoni-pitha type fire altar with a stump of octagonal birch in the middle. “This is an indication that rituals were performed at the altar,” said Pandey. The thing that stands out in these excavations is the windfall of pre-Harappan hakra ware, early Harappan pottery and Mature Harappan ceramics. Early Harappan finds include pottery with beautifully painted figures of peacocks, a lion, birds, fish-net and floral designs.

When the excavations initially began, it was found that a lot of waste material had been dumped on the mound by the local people and the Army, which had camped there soon after the partition. This turned out to be a good thing in the end as the dump had protected the mound. But agricultural and irrigation activities later led to the cutting of the mound on three sides which reduced its size considerably.

The trenches have brought to the fore the remnants of saddle— querns, mullars, ovens, hearths and furnaces. Pandey postulated, “One trench has also revealed a deep silo, lined with mud, to store grains. We have also recovered cattle bones and soil and grain samples, and they are yet to be sent for further examination and carbon dating.” He also disclosed that a bead containing the swastika symbol was also found which greatly fascinated all the archaeologists present at the site. “A lot of red ware and hakra pottery have also been discovered. Storage jars, goblets, stands, miniature pots, vases and paintings with horizontal bands, loops, floral designs and figures of birds and animals of the cat family have been discovered as well. Another intriguing aspect which was found in the handled pots was that there was incised decoration on them, at accurate intervals. Pots with textile and type imprint were also uncovered. These are usually painted with black, and at times, white colour,” he shared.

Pandey concluded by saying, “This is the first site in this region where so much of cultural mixing or amalgamation is available. It has helped in determining the cultural process of the early and mature Harappan phases and the gradual transition from one phase to the other. Interestingly, we could not find any artefacts relating to the late Harappan period at the site.”

This is a signature tune of a Soma SamsthA performed at the site on the banks of Vedic River Sarasvati.

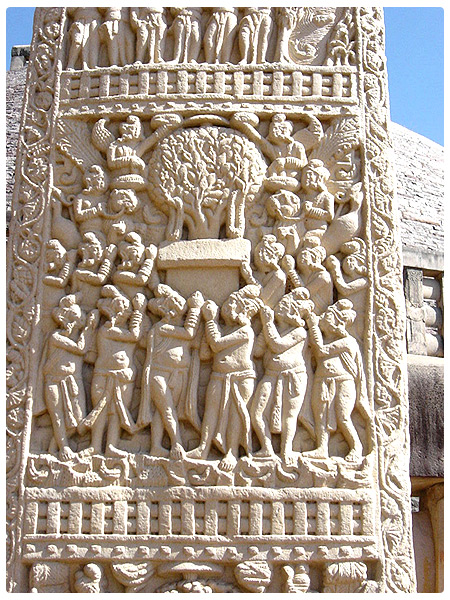

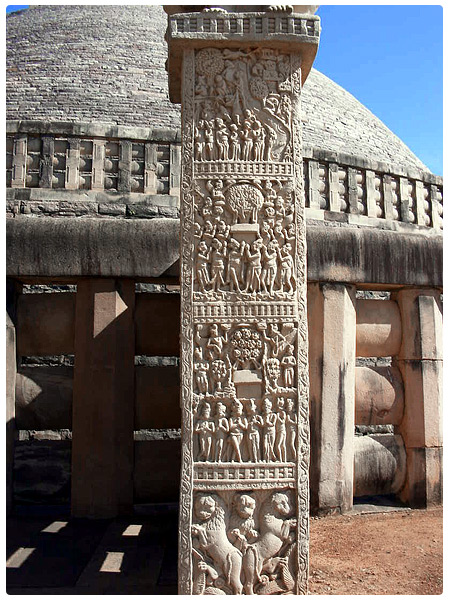

A remarkable discovery is the octoganal brick which is a yaṣṭi.in a fire-altar of Bijnor site on the banks of Vedic River Sarasvati. Thi yaṣṭi attests to the continuum of the Vedic tradition of fire-altars venerating the yaṣṭi as a baton, skambha of divine authority which transforms mere stone and earth into metal ingots, a manifestation of the cosmic dance enacted in the furnace/smelter of a smith. Bhuteswar sculptural friezes provide evidence to reinforce this divine dispensation by describing the nature of the smelting process displaying a tree to signify kuTi rebus: kuThi 'smelter' with kharva 'dwarf' adorning the structure with a garland to signify kharva 'a nidhi or wealth' of Kubera. A Bhutesvar frieze also indicates the skambha with face signifying ekamukha linga rebus:

mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends;kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali).

Kalibangan. Mature Indus period: terracotta cake incised with horned deity. Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India See notes at http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/functions-served-by-terracotta-cakes-of.html A terracotta type found in Kalibangan has the hieroglyph of a warrior: bhaTa 'warrior' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace', thus reinforcing the smelting process in the fire-altars. Smelters might have used bhaThi 'bellows'. bhástrā f. ʻ leathern bag ʼ ŚBr., ʻ bellows ʼ Kāv., bhastrikā -- f. ʻ little bag ʼ Daś. [Despite EWA ii 489, not from a √bhas ʻ blow ʼ (existence of which is very doubtful). -- Basic meaning is ʻ skin bag ʼ (cf. bakura<-> ʻ bellows ʼ ~ bākurá -- dŕ̊ti -- ʻ goat's skin ʼ), der. from bastá -- m. ʻ goat ʼ RV. (cf.bastājina -- n. ʻ goat's skin ʼ MaitrS. = bāstaṁ carma Mn.); with bh -- (and unexpl. -- st -- ) in Pa. bhasta -- m. ʻ goat ʼ, bhastacamma -- n. ʻ goat's skin ʼ. Phonet. Pa. and all NIA. (except S. with a) may be < *bhāsta -- , cf. bāsta -- above (J. C. W.)]With unexpl. retention of -- st -- : Pa. bhastā -- f. ʻ bellows ʼ (cf. vāta -- puṇṇa -- bhasta -- camma -- n. ʻ goat's skin full ofwind ʼ), biḷāra -- bhastā -- f. ʻ catskin bag ʼ, bhasta -- n. ʻ leather sack (for flour) ʼ; K. khāra -- basta f. ʻ blacksmith's skin bellows ʼ; -- S. bathī f. ʻ quiver ʼ (< *bhathī); A. Or. bhāti ʻ bellows ʼ, Bi. bhāthī, (S of Ganges) bhã̄thī; OAw. bhāthā̆ ʻ quiver ʼ; H. bhāthā m. ʻ quiver ʼ, bhāthī f. ʻ bellows ʼ; G. bhāthɔ,bhātɔ, bhāthṛɔ m. ʻ quiver ʼ (whence bhāthī m. ʻ warrior ʼ); M. bhātā m. ʻ leathern bag, bellows, quiver ʼ, bhātaḍ n. ʻ bellows, quiver ʼ; <-> (X bhráṣṭra -- ?) N. bhã̄ṭi ʻ bellows ʼ, H. bhāṭhī f. *khallabhastrā -- .Addenda: bhástrā -- : OA. bhāthi ʻ bellows ʼ .(CDIAL 9424) bhráṣṭra n. ʻ frying pan, gridiron ʼ MaitrS. [√bhrajj] Pk. bhaṭṭha -- m.n. ʻ gridiron ʼ; K. büṭhü f. ʻ level surface by kitchen fireplace on which vessels are put when taken off fire ʼ; S. baṭhu m. ʻ large pot in which grain is parched, large cooking fire ʼ, baṭhī f. ʻ distilling furnace ʼ; L. bhaṭṭh m. ʻ grain -- parcher's oven ʼ, bhaṭṭhī f. ʻ kiln, distillery ʼ, awāṇ. bhaṭh; P. bhaṭṭhm., °ṭhī f. ʻ furnace ʼ, bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ; N. bhāṭi ʻ oven or vessel in which clothes are steamed for washing ʼ; A. bhaṭā ʻ brick -- or lime -- kiln ʼ; B. bhāṭi ʻ kiln ʼ; Or. bhāṭi ʻ brick -- kiln, distilling pot ʼ; Mth. bhaṭhī, bhaṭṭī ʻ brick -- kiln, furnace, still ʼ; Aw.lakh. bhāṭhā ʻ kiln ʼ; H. bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ, bhaṭ f. ʻ kiln, oven, fireplace ʼ; M. bhaṭṭā m. ʻ pot of fire ʼ, bhaṭṭī f. ʻ forge ʼ. -- X bhástrā -- q.v.bhrāṣṭra -- ; *bhraṣṭrapūra -- , *bhraṣṭrāgāra -- .Addenda: bhráṣṭra -- : S.kcch. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ʻ distil (spirits) ʼ.*bhraṣṭrāgāra ʻ grain parching house ʼ. [bhráṣṭra -- , agāra -- ]P. bhaṭhiār, °ālā m. ʻ grainparcher's shop ʼ.(CDIAL 9656, 9658)

![]()

The fire altar, with a yasti made of an octagonal brick. Bijnor (4MSR) near Anupgarh, Rajasthan. Photo:Subhash Chandel, ASI "(Archaeologist) Pandey said fire altars had been found in Kalibangan and Rakhigarhi, and the yastis were octagonal or cylindrical bricks. There were “signatures” indicating that worship of some kind had taken place at the fire altar here." http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/heritage/harappan-surprise/article7053030.ece Amarendra Nath, archaeologist who excavated Rakhigarhi also noted: “Mature Period II is marked by a fortification wall and fire altars with yaSTi and yonipITha, with muSTikA offerings.”(Puratattgva: Bulletin of the Indian Archaeological Society 29 (1998-1999): 46-49). Compare these 'shafts' in fire-altars with the pillars or cylindrical offering bases in Dholavira within an 8-shaped stone-wall enclosure:

Also comparable are the skambha pillar atop a smelter in Bhutesvar friezes:

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda)