Halil Rud Civilization; Intercultural Style; Chlorite Hand-bag; Meteoritic Iron

http://ijas.usb.ac.ir/article_1442.html

Jiroft, Cradle Of Human Civilization In Iran?For centuries, Mesopotamia was thought to be the world's oldest civilization. This was generally accepted by most people until a 5,000-year old temple was discovered in Jiroft Historical Site in Iran's southern Kerman province, prompting archaeologists to identify the region as the world's oldest cradle of human civilization.

![Jiroft, cradle of human civilization in Iran? Jiroft, cradle of human civilization in Iran?]() | One of the mounds at Jiroft Historical Site

[Credit: Ali Shahryari] |

Jiroft has undergone different phases of archeological excavations since 2002. Although many valuable objects, including two clay inscriptions carrying the oldest human scripts, have been unearthed during authorized excavations in the region, many more such objects have been found by pillagers and smuggled abroad to become the centerpieces in museums across the world.

Nader Alidad Soleimani, the manager of Jiroft's Cultural Heritage Site, has been studying the location for the past 20 years. He has greatly contributed to safeguarding the cultural and historical remains of Jiroft.

Iran Daily conducted an interview with him to get detailed information about the ongoing studies.

Excerpts follow:

ID: Please explain the various phases of excavations that have been conducted in Jiroft.

SOLEIMANI: The first phase of official archaeological studies was conducted during 2002-2007. The studies resumed in the region in 2014 after a seven-year pause. However, I have been exploring the Jiroft region since 1995, since I was aware of the historical importance of Jiroft, years before official studies began. Currently, the second season of excavations is underway in Esfandagheh Plains in Jiroft. The first season was completed last summer.

![Jiroft, cradle of human civilization in Iran? Jiroft, cradle of human civilization in Iran?]() | Excavations at site B - thought to be a citadel

[Credit: National Geographic] |

Valuable architectural items have been unearthed during the first and the second excavation seasons, including evidences of Neolithic settlement and the remnants of ancient buildings in red and yellow colors. In addition to archaeological excavations, the joint three-month research studies were conducted in collaboration with a delegation from German University of Tübingen International and Iranian experts during Feb. 20-May 20, 2015. The research yielded positive outcomes and raised our knowledge about the historical site.

ID: American archaeologists have described Jiroft's excavations as the largest excavation projects of its kind ever conducted in the Middle East. The importance of Jiroft's human civilization has been accepted by French, British and Italian experts as well. Many experts also believe that if any important event were to occur in the field of archaeology within the next 50 years, it would definitely occur in Jiroft. Please tell us more about the geographic situation of Jiroft and its importance.

SOLEIMANI: Many think that Jiroft is only a city with identifiable boundaries. This is while, when we talk of Jiroft we mean an extensive cultural field that once was thrived along Halilroud river. The river is situated in the southeast of Iran near Jiroft, Kerman province. The river, which extends for 390 kilometers, runs along the Jiroft and Kahnuj districts. It originates in Hazar mountains, some 3,300 meters above sea level and about 100 kilometers to the northwest of Jiroft, and flows to the southwest. Many historical hills have been located in this massive area, each providing valuable evidence of the cultural richness of the region. The region is host to various archeological teams every year.

![Jiroft, cradle of human civilization in Iran? Jiroft, cradle of human civilization in Iran?]() | An inscription found in archaeological excavations of Kerman Province near,Jiroft,

or the Halil Rud region of Iran, which dates back to the sixth millennium BC

[Credit: Sciencepost] |

ID: Which countries are involved in the archaeological excavation project of Jiroft?

SOLEIMANI: The US, France, Italy and, very recently, Germany have so far sent archaeological teams to Jiroft. Foreign archaeological teams can only work under the supervision of Iranian experts. Their activities are also limited.

ID: Why are foreign teams needed for excavations?

SOLEIMANI: Today, archaeology is regarded as an interdisciplinary field. Ancient Botany and Osteology are among the fields of study that have contributed to the development of global archaeology over the past few years. Such fields of study are not available in Iranian universities. Sometimes, they are available but domestic knowledge about them is poor. Theses shortcomings make the need for using the proficiency of foreign archaeologists greatly felt. Foreign experts engaged in excavations help train Iranian students, improve their knowledge, and contribute to the archaeological excavations.

ID: Numerous illegal diggings have taken place in the region in the past, leading to the smuggling of many valuable items. What has the government done to address illegal pillagers or prevent such problems from recurring?

SOLEIMANI: Illegal diggings have damaged Jiroft historical site over the years, leading to the smuggling of a great volume of valuable historical objects, which are now being kept at the world's prestigious museums. The Iranian government has taken effective steps for the repatriation of such objects. Eighteen artifacts, each dating back to 5,000 years were returned home four years ago thanks to former government's efforts. The return of historical objects becomes a more complicated if they are owned by unknown private collectors or kept at private museums. Filing lawsuit against private collectors in international courts is a tougher job.

ID: How much money is allocated for archaeological projects annually?

SOLEIMANI: An annual $10,000 is allocated by the government for archaeological excavations in Jiroft, which is meager given the extensive areas which have to be explored. An archaeological team consists of only six individuals and this is not enough for conducting excavations over such extensive areas. All the shortages pave the ground for looters, and increase the risk of illegal diggings. urrently, the digs are refilled on the completion of the projects so that the site and historical objects can be protected. This is while, a historical site, such as Jiroft, can also serve as an open-air museum. An open-air museum attracts so many visitors and contributes to the development of tourism sector as well.

Author: Fatemeh Shokri & Atefeh Rezvan-Nia | Source: Iran Daily [August 04, 2015]

https://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.in/2015/08/jiroft-cradle-of-human-civilization-in.html#YMj4fRospTI7tiqa.97

Ancient Metal Relics Discovered In Jiroft

Persian Journal ^ | 7-19-2006

Posted on 21/07/2006, 03:34:59 by blam

Ancient Metal Relics Discovered in Jiroft

Jul 19, 2006

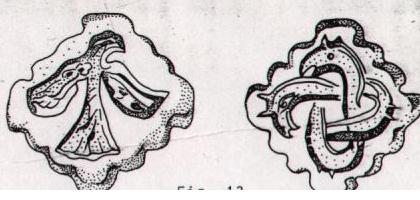

The police department of Jiroft succeeded in confiscating 41 metal relics belonging to the pre-historic and historic periods. The most ancient one is a Riton belonging to the third millennium BC. Riton is a kind of goblet with the head of an animal, usually in the shape of a lion, horse, ibex, or winged lion.

![]()

"The police department of Jiroft found 41 bronze, copper, and silver relics. The most ancient one is a Riton with the head of a humped cow belonging to some 5000 years ago," said Nader Soleimani, archeologist from the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Department of Kerman province.

According to Soleimani, a bronze dagger belonging to the first millennium BC with the design of an animal like crocodile is one of the other interesting relics in this collection. "The designs which can be seen on this dagger depict something like the crocodiles which still exist in south of Chabahar Port in Iran's Sistan va Baluchestan province. The person who came up with this design must have seen this animal closely to be able to put down such accurate pattern," added Soleimani.

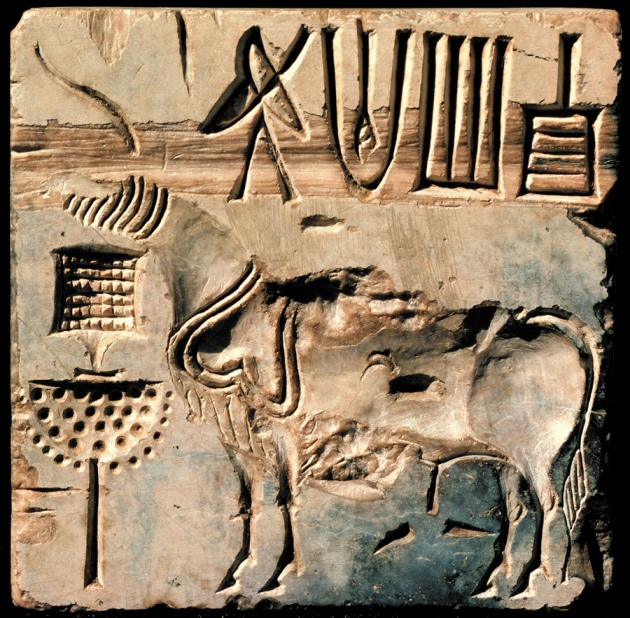

A bronze axe and a copper plaque engraved with a humped cow, an ibex and palm tree are the other discovered relics. "Such designs had already been seen in other parts of Jiroft on artifacts made with soapstone," said Soleimani.

Soleimani also announced the existence of a small bronze vessel belonging to the third millennium BC with some geometrical designs, and also 24 antique coins belonging to different periods of Parthian, Sassanid, the beginning of Islamic, Seljuk, Ilkhanid, Safavid, and Qajar periods in this newly discovered collection.

Jiroft historical site is located in Kerman province on the basin of Halil Rud River. Jiroft is known to be one of the most historical sites of the world which enjoyed a rich civilization in the third millennium BC. Over 100 historical sites have so far been identified along the bank of Halili-Rud River, extended for 400 kilometers.

Lack of enough control over this historical site and unawareness of the public about its importance turned Jiroft into a paradise for illegal diggers, plundering a large number of ancient relics in this site. What happened in Jiroft is today known as one of the most tragic events in archeology. It was only after all these illegal excavations that the archeologists rushed to this area to study one of the most prominent historical sites in Iran which revealed much about one of the most ancient civilizations of the world. Some archeologists believe that more findings on the earliest civilization that lived in Jiroft will be a turning point in their current understanding of the history of civilization.

![]()

"This threshold of history found in Jiroft is what is lost in the evolution course of the Mesopotamian civilization and is not that notable in that of Egypt. There are so many objects dating to this time found in the Halil-Rud Area, which can fill the gap in the formation and development course of the Jiroft civilization. Therefore, one can say that Jiroft is the capital of today's world archeology because it allows the archeologists to modify the previous theories on how people lived during that time. The part of history that was hidden in the strata of Iran's plateau is essential to rebuilding the base of world's history," these words were expressed by Jean Perrot, one of world's greatest archeologists who headed the French teams working in Iran from 1968 to 1978 and also attended the International Conference of Halil-Rud Civilization which was held in Jiroft from 1-3 February 2005.

Up until now, some 4000 historical relics which had been unearthed during illegal excavations in Jiroft have been identified and confiscated by the police department.

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1669440/posts

Halil-Rud Civilization: Shahdad

Shahdad Halil-Rud Civilization تمدن هلیل رود- شهداد Ever since the excavations of Ali Hakemi at the site of Shahdad at the edge of the Dasht-I Lut, we have understood that the Bronze Age communities of the Iranian plateau played a central role in the greater ancient world system of exchange that connected all of the Middle East during the 3rd millennium BC. When published in comprehensive form, Hakimi’s results, combined with Tal-I Iblis and Yahya, allowed us to begin to sketch picture of long distance interaction that began with the arrival of the proto- Elamites into the region around 3000 BC and intensified for a millennium before it faded in response to environmental challenges. With additional data coming from the recent excavation at the sites of Konar Sandal South and North in the Halil River Valley, we can now begin to construct a picture of interaction that puts the region of Kerman as a central nexus of interaction in all directions. (Pittman 2011) Prehistoric Shahdad was a major Bronze Age centre discovered at the edge of the Dasht-e-Lut in 1968. From that point up until the early 1970s, the late professor ALI HAKEMI of the Archaeological Institute of Iran supervised intensive excavations at Shahdad over seven consecutive seasons, revealing extensive evidence for a sophisticated civilization using a range of elite artifacts, elaborate metalwork technology, complex burial practices and archaic pictographs. In many ways, the late 1960s and 1970s were a truly pioneering period for the archaeology of southeast Iran, and work at sites like Shahdad, Tal-e Iblis, and Tepe Yahya revolutionized our understanding of Iran in the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. Since the publication of the monumental volume “SHAHDAD - Archaeological Excavations of a Bronze Age Center in Iran” by ISMEO in 1997, there have been several major books published on the archaeology of southeast Iran, and extensive new excavations at several mound sites, including Konar Sandal at Jiroft in the Halil Rud plain. Five Linear Elamite texts inscribed on metal vessels (W, X, Y, Z and A’) have been recently ‘published’. Through their comparison with the susian Linear Elamite documents corpus, they permit to identify several graphical variants for the same sign. This consideration about graphical variations in Linear Elamite writing gives a better understanding of the only inscription (S) found up to now in Shahdad. Then will be particularly examined the sign probably used to note down the sound in, for which ‘occidental’ variations (in Susa and Marv Dasht plain), different from ‘oriental’ ones (in Shahdad and Konar Sandal), have been identified. ( Desset, 2011) We sampled a small collection of copper working indicators (slag, crucibles, kiln linings, possibly ore fragments) from 4th and 3rd millennium BCE settlement areas of Shahdad. These finds were investigate by the means of XRD, SEM and metallographic analysis, providing preliminary information on the type of metallurgical processes carried out in the site and their changes in time.( Vidale, 2011) Southeast of Iran especially Kerman region has played an important role during the fourth and third millennium BC due to its rich Mines. The most important metallurgical analysis is Hakemi’s work, which have been carried out on Shahdad samples. He has analyzed these samples through AAS, EDAX, SEM and XRFS. Results of his analyses show that high percentage of the coppers in the Shahdad objects testify that craftsmen of Shahdad had not alloyed copper and tin during the 4th and 3rd millennium BC; however a few samples showed that they might have been aware to alloy copper and tin. ( Mortazavi, 2011) The finds of objects made of a special type of coralline limestone are distributed over a vast area that extends from the Persian Gulf and the eastern Iranian Plateau to Mesopotamia. While two manufacturing areas of this stone have been recently identified at Shahdad (see the related paper of Vidale, Desset, Pignatti and Conti), a group of such objects found in excavations at Tello (ancient Girsu) and bearing dedicatory inscriptions of rulers of the so-called Second Dynasty of Lagash, or of high-ranking officials in their service, attest to trade relationships between the independent city-state of Lagash and the East (possibly the area of Shahdad) throughout several generations. These objects are also remarkable in that they represent a unique class of prestige goods and votive artefacts: indeed, in Mesopotamia, they are almost exclusively found at Lagash and for a relatively short period of time. An argument is presented that the ancient name of the stone of which they were made was pirig-gùnu, "spotted lion," that is "leopard spotted stone" - a name that recalls one of the animal symbols par excellence in the Iranian art of the third millennium BC. (Marchesi, 2011) Between 1967 and 1970 three sites in Eastern Iran, Shahdad, Shahr-i Sokhta, Tepe Yahya, contributed to open a new perspective on the emergence of civilization in the Ancient Orient filling the geographic gap between the Near East and the Indian Subcontinent, proving that political complexity and economic wealth had been equally shared by the all agricultural heartlands east of Mesopotamia. While trade circuits and exchange networks did connect desert highlands and alluvial floodplains in a mosaic of polities culturally linked in spite of the autarchic structure of their economies. (Tosi, 2011)

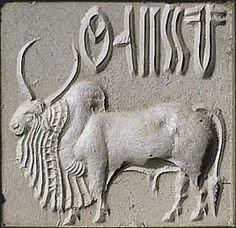

- Jiroft. Antelope, snake, tiger. ranku 'antelope', 'liquid measure'; read rebus: ranku 'tin'. kol = tiger (Santali) kol ‘pancaloha, alloy of five metals (Ta.) http://sarasvatismithy.blogspot.com/ na_ga `serpent' (Sanskrit) na_ga `lead' (Sanskrit)

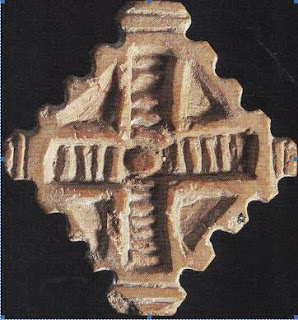

pōḷa dhā̆vaḍ sãgaṛh 'fortified settlement of magnetite steel, ore workers' signified by Sarasvati Script hieroglyphs

--Hieroglyphs पोळ pōḷa 'zebu'& pōlaḍu 'black drongo' signify polad 'steel'; saggeḍa 'cup' signifies sãgaṛh 'fortified settlement'; samghāta 'adamantine glue or hard metallic cement'

--Evidence from Nahal Mishmar, Jiroft, Halil Rud, Konar Sandal Ancient Near East (Sarasvati Civilization contact areas of Bronze Age, 3rd millennium BCE)

It is remarkable that Meluhha artisans had attained in 3rd millennium BCE the metallurgical competence to formulate adamantine glue (vajra) or hard metallic cement.

Massimo Vidale et al have provided remarkable archaeological narratives from Konar Sandal and Halil Rud (Helmand):

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02666030.2015.1008820 (Konar Sandal)https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Indus-helmand2.pdf (Helmand)

![Related image]() Jiroft. Vase. Basket-shaped wallet. http://antikforever.com/Perse/Divers/jiroft.htm Jiroft. Vase. Basket-shaped wallet. http://antikforever.com/Perse/Divers/jiroft.htm

Bi. dhŏkrā ʻ jute bag ʼ; Mth. dhokṛā ʻ bag, vessel, receptacle ʼ; OMarw. ḍhokaro m. ʻ basket ʼ; -- N. ḍhokse ʻ place covered with a mat to store rice in, large basket ʼ.(CDIAL 6880) Rebus: dhokra kamar 'cire perdue, lost-wax casting metalworker'.

āre 'lion' rebu: āra 'brass' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting'.

pōḷa 'zebu' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore)

pōladu 'black drongo bird' rebus: pōḷad 'steel'

Thus, this Jiroft vase with Sarasvati Script hieroglyphs is a professional calling card -- dharma samjñā 'responsibility badge' -- of the Meluhha cire perdue metalcaster.

"Steel (with a carbon content between pig iron and wrought iron) was first produced in antiquity as an alloy. Its process of production, Wootz steel, was exported before the 4th century BC to ancient China, Africa, the Middle East and Europe. Archaeological evidence of cast iron appears in 5th century BC China."

![]() Bulat steel blade of a knife."Bulat is a type of steel alloy known in Russia from medieval times; regularly being mentioned in Russian legends as the material of choice for cold steel. The name булат is a Russian transliteration of the Persian word fulad, meaning steel. This type of steel was used by the armies of nomadic peoples. Bulat steel was the main type of steel used for swords in the armies of Genghis Khan, the great emperor of the Mongolian Empire. The technique used in making wootz steel has been lost for centuries and the bulat steel used today makes use of a more recently developed technique...Carbon steel consists of two components: pure iron, in the form of ferrite, and cementite or iron carbide, a compound of iron and carbon. Cementite is very hard and brittle; its hardness is about 640 by the Brinell hardness test, whereas ferrite is only 200. The amount of the carbon and the cooling regimen determine the crystalline and chemical composition of the final steel. In bulat, the slow cooling process allowed the cementite to precipitate as micro particles in between ferrite crystals and arrange in random patterns. The color of the carbide is dark while steel is grey. This mixture is what leads to the famous patterning of Damascus steel. Bulat steel blade of a knife."Bulat is a type of steel alloy known in Russia from medieval times; regularly being mentioned in Russian legends as the material of choice for cold steel. The name булат is a Russian transliteration of the Persian word fulad, meaning steel. This type of steel was used by the armies of nomadic peoples. Bulat steel was the main type of steel used for swords in the armies of Genghis Khan, the great emperor of the Mongolian Empire. The technique used in making wootz steel has been lost for centuries and the bulat steel used today makes use of a more recently developed technique...Carbon steel consists of two components: pure iron, in the form of ferrite, and cementite or iron carbide, a compound of iron and carbon. Cementite is very hard and brittle; its hardness is about 640 by the Brinell hardness test, whereas ferrite is only 200. The amount of the carbon and the cooling regimen determine the crystalline and chemical composition of the final steel. In bulat, the slow cooling process allowed the cementite to precipitate as micro particles in between ferrite crystals and arrange in random patterns. The color of the carbide is dark while steel is grey. This mixture is what leads to the famous patterning of Damascus steel.

Cementite is essentially a ceramic, which accounts for the sharpness of the Damascus (and bulat) steel. Cementite is unstable and breaks down between 600–1100 °C into ferrite and carbon, so working the hot metal must be done very carefully." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulat_steel

“One of the big mysteries of wootz Damascus steel has been why the art of making these blades was lost…to produce the damascene patterns of a museum-quality wootz Damascus blade the smith would have to fulfill at least three requirements. First, the wootz ingot would have to have come from an ore deposit that provided significant levels of certain trace elements, notably, Cr, Mo, Nb, Mn, or V. This idea is consistent with the theory of some authors30 who believe the blades with good patterns were only produced from wootz ingots made in southern India, apparently around Hyderabad. Second, the data … confirm previous knowledge that wootz Damascus blades with good patterns are characterized by a high phosphorus level. This means that the ingots of these blades would be severely hot short.. as previously shown,15successful forging would require the development of heat-treating techniques that decarburized the surface in order to produce a ductile surface rim adequate to contain the hot-short interior regions. Third, a smith who developed a heat-treatment technique that allowed the hot-short ingots to be forged might still not have learned how to produce the surface patterns, because they do not appear until the surface decarb region is ground off the blades; this grinding process is not a simple matter.” http://www.tms.org/pubs/journals/JOM/9809/Verhoeven-9809.html

Hypertext on Mohenjo-daro seal m301 is composed of hieroglyphs to create a 'composite animal'; this animal has zebu horns. Zebu is the dominant signature tune of Sarasvati Civilization. The message and meaning of the hypertexts of the inscription is simple: a metalwork catalogue is documented by the artisan. The 'rim=of-jar'. hieroglyph signifies a seafaring merchant with a cargo of metalwork: khanka'rim-of-jar' rebus: karṇika, karaika 'helmsman of a seafaring merchant vessel' and supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.

![]() m0301 Mohenjo-daro seal. m0301 Mohenjo-daro seal.

Components of hieroglyph multiplex of m0301 inscription are: --ram or sheep (forelegs denote a bovine) --neck-band, ring --bos indicus (zebu)(the high horns denote a bos indicus) --elephant (the elephant's trunk ligatured to human face) --tiger (hind legs denote a tiger) --serpent (tail denotes a serpent) --human face

All these glyphic elements are decoded rebus:

meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120); kaḍum ‘neck-band, ring’ adar ḍangra ‘zebu’ ibha ‘elephant’ (Skt.); rebus: ib ‘iron’ (Ko.) kolo ‘jackal’ (Kon.)

moṇḍ the tail of a serpent (Santali) Rebus: Md. moḍenī ʻ massages, mixes ʼ. Kal.rumb. moṇḍ -- ʻ to thresh ʼ, urt. maṇḍ -- ʻ to soften ʼ (CDIAL 9890) Thus, the ligature of the serpent as a tail of the composite animal glyph is decoded as: polished metal (artifact).

mũhe ‘face’ (Santali); mleccha-mukha (Skt.) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali)

கோடு kōṭu : •நடுநிலை நீங்குகை. கோடிறீக் கூற் றம் (நாலடி, 5). 3. [K. kōḍu.] Tusk; யானை பன்றிகளின் தந்தம். மத்த யானையின் கோடும் (தேவா. 39, 1). 4. Horn; விலங்கின் கொம்பு. கோட்டிடை யாடினை கூத்து (திவ். இயற். திருவிருத். 21). Ta. kōṭu (in cpds. kōṭṭu-) horn, tusk, branch of tree, cluster, bunch, coil of hair, line, diagram, bank of stream or pool; kuvaṭu branch of a tree; kōṭṭāṉ, kōṭṭuvāṉ rock horned-owl (cf. 1657 Ta. kuṭiñai). Ko. kṛ (obl. kṭ-) horns (one horn is kob), half of hair on each side of parting, side in game, log, section of bamboo used as fuel, line marked out. To. kwṛ (obl. kwṭ-) horn, branch, path across stream in thicket. Ka. kōḍu horn, tusk, branch of a tree; kōr̤ horn. Tu. kōḍů, kōḍu horn. Te. kōḍu rivulet, branch of a river. Pa. kōḍ (pl. kōḍul) horn (DEDR 2200)

meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) khāḍ ‘trench, firepit’ aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’ (H.) poL 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite' kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pancaloha’ (Ta.) mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends (Santali) koḍ = the place where artisans work (G.)

Orthographically, the glytic compositions add on the characteristic short tail as a hieroglyph (on both ligatured signs and on pictorial motifs)

xolā = tail (Kur.); qoli id. (Malt.)(DEDr 2135). Rebus: kol ‘pañcalōha’ (Ta.)கொல் kol, n. 1. Iron; இரும்பு. மின் வெள்ளி பொன் கொல்லெனச் சொல்லும் (தக்கயாகப். 550). 2. Metal; உலோகம். (நாமதீப. 318.) கொல்லன் kollaṉ, n. < T. golla. Custodian of treasure; கஜானாக்காரன். (P. T. L.) கொல்லிச்சி kollicci, n. Fem. of கொல்லன். Woman of the blacksmith caste; கொல்லச் சாதிப் பெண். (யாழ். அக.) The gloss kollicci is notable. It clearly evidences that kol was a blacksmith. kola ‘blacksmith’ (Ka.); Koḍ. kollë blacksmith (DEDR 2133). Vikalpa: dumba दुम्ब or (El.) duma दुम । पशुपुच्छः m. the tail of an animal. (Kashmiri) Rebus: ḍōmba ?Gypsy (CDIAL 5570).

sangaḍi = joined animals (Marathi) Rebus: sãgaṛh m. ʻ line of entrenchments, stone walls for defence ʼ (Lahnda)(CDIAL 12845) [Note: Within this fortification, zebu signifies a poliya 'citizen, gatekeeper of town quarter'.] This suggests that seal m0301 is an archaeometallurgist signifying the guild of artisans at work in the fortified settlement.

baraDo 'backbone' Rebus: bharat 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' karNIka 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNIka 'scribe'.

dhatu 'scarf' Rebus: dhatu 'mineral' kola 'tiger' Rebus: kolhe 'smelter' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead' खोंड khōṇḍa A variety of जोंधळा.कांबळा-cowl. खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. Rebus: khond 'turner'

Hieroglyph: pōḷa 'zebu' Rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore'

Hieroglyph: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi)

Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. (Marathi)

Nahal Mishmar. Crown with building facade decoration, Ibex and birds on Nahal Mishmar artefacts

After examining several artefacts of Nahal Mishmar hoard, Goren concludes: "The results of this study indicate that all the examined materials were the remains of the casting molds...This indeed indiates that the Chalcolithic technology of mold construction for the lost wax casting technique was well established and performed by specialists. Moreover, the emphasized homogeneity of the materials and technology in use, regardless of the location of the find, stands against the possibility of production by itinerary craftsmen and supports the idea that all of these items were produced by a single workshop or workshop cluster. The results make it clear that, although Chalcolithic mold production and casting techniques can be compared to some extent with the methods of traditional craftsmen such as the Dhokra of India, they are far more sophisticated and thus more analogous with the mold construction techniques used today by modern workshops...some motifs...specifically depict ibexes and vultures...It is likely that these animals were seen as protectors of this highly skilled metallurgy... (ibex) representation in the En Gedi sanctuary might be related to the special role of this animal in the decoration fo the Chalcolithic metal artifacts as well as ossuaries. (p.393)"

[Yuval Goren, 2008, The location of specialized copper production by the lost wax technique in the chalcolithis southern Levant, Geoarchaeology: An international Journal, Vol. 23, No. 3, 374-397 (2008), p. 377].

http://www.scribd.com/doc/220039411/Yuval-Goren-2008-The-location-of-specialized-copper-production-by-the-lost-wax-technique-in-the-chalcolithis-southern-Levant-Geoarchaeology-An-int

Radiocarbon dating of Nahal Mishmar reed mat by Arizona AMS laboratory takes at least some of (the finds to 5375 +_ 55 to 6020+_60 BP). (Aardsman, G., 2001, New radiocarbon dates for the reed mat from the cave of the treasure, Israel, Radiocarbon, Volume 43, number 3: 1247-1254). This indicates the possibility that cire perdue technique was already known to the metallurgists who created the Nahal Mishmar artefacts. There is, however, a possibility that all the artefacts of the Nahal Mishmar hoard may not belong to the same date and hence, cire perdue artefacts might have been acquisitions of a later date. (Shlomo Guil

I suggest that an interpretation for the use of ibex and birds on Nahal Mishmar artefacts. They may be Meluhha hieroglyphs describing the specific metallurgical skill of and materials used by the artisans.

![In 1961, a group of archaeologists were looking for Dead Sea scrolls. Instead, they found the striking double ibex and the rest of the hoard now known as the "Cave of Treasure." (Courtesy of the Israel Museum)]() ![]()

The double ibex was made using a complicated wax and ceramic mold..Standard (scepter)

with ibex heads.

Dm. mraṅ m. ‘markhor’ Wkh. merg f. ‘ibex’ (CDIAL 9885) Tor. miṇḍ ‘ram’, miṇḍā́l ‘markhor’

(CDIAL 10310) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Munda.Ho.) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. āra‘six’ Rebus: āra ‘brass’ karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'.![]() ![]()

sã̄gāḍā m. ʻ frame of a building ʼ (M.)(CDIAL 12859) Rebus: jaṅgaḍ ‘entrustment articles’ sãgaṛh m. ʻ line of entrenchments, stone walls for defence ʼ (Lahnda).(CDIAL 12845) Allograph: saṅgaḍa ‘lathe’. 'potable furnace'. sang ‘stone’, gaḍa ‘large stone’. Rebus: Vajra-samghāta is to be compounded of 8 parts of lead, 2 parts of bell metal and 1 part of brass, melted and poured hot. It is stated that when this type of cement is applied to temple, etc. they last for around thousand years. Vajra-samghāta means, composition as hard as thunderbolt.

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. koḍ ‘horns’ Rebus: koḍ‘artisan’s workshop’.

पोलाद [ pōlāda ] n ( or P) Steel. पोलादी a Of steel. (Marathi) ولاد polād, s.m. (6th) The finest kind of steel. Sing. and Pl. folād P فولاد folād or fūlād, s.m. (6th) Steel. Sing. and Pl. folādī P فولادي folādī or fūlādī, adj. Made of steel, steel. (Pashto) pŏlād प्वलाद् or phōlād फोलाद् । मृदुलोहविशेषः m. steel (Gr.M.; Rām. 431, 635, phōlād).pŏlödi pōlödi phōlödi (= ) । लोहविशेषमयः adj. c.g. of steel, steel (Rām. 19, 974, 167, pōo) pŏlāduwu । शस्त्रविशेषमयः adj. (f. pŏlādüvü made of steel (H. v, 4).(Kashmiri).

Polad, bulat crucible steel

'Schrader gives a list of names for 'steel' related to Pers. pulAd; Syr. pld; Kurd. pila, pola, pulad; Pehl. polAwat; Armen. polovat; Turk. pala; Russ. bulat; Mizdzhegan polad, bolat; Mongol. bolot, bulat, buriat. He is unable to suggest an origin for these words. Fr. Muller pointed out that the Pehlevi and Armenian should be polapat and suggested Greek 'much-beaten' as the original word...not all the countries of Asia had been exhausted in search for similar names...by adding Tibetan p'olad, Sulu bAlan, Tagalog patalim, Ilocano paslip, we at once see that the origin of the word may lie to the east. Naturally one thinks of China as the possible point of issue, for there steel was known in the third millenium before our era and we have the positive reference to steel in a Chinese writer of the fifth century BCE...Cantonese dialect fo-lim, literally 'fire-sickle'..."(Wiener, Leo, 2002, Contributions toward a history of Arabico-Gothc culture, vol.4, Gorgias Press LLC, pp. xli-xlii)

"...‘pulad’ of Central Asia. The oasis of Merv where crucible steel was also made by the medieval period lies in this region. The term ‘pulad’ appears in Avesta, the holy book of Zorastrianism and in a Manichéen text of Chinese Turkestan. There are many variations of this term ranging from the Persian

‘polad’, the Mongolian ‘bolat’ and ‘tchechene’, the Russian ‘bulat’, the Ukrainian and Armenian ‘potovat’, Turkish and Arab ‘fulad’, ‘farlad’ in Urdu and ‘phaulad’ in Hindi. It is this bewildering variety of descriptions that was used in the past that makes a study of this subject so challenging."

https://www.scribd.com/doc/268526061/Wootz-Steel-Indian-Institute-of-Science Wootz Steel, Indian Institute of Science

Meluhha and Jiroft

A dominant hieroglyph depicted on Jiroft artifacts is a 'wallet'. The Meluhha word for this hieroglyph is dhokra. Meluhha hieroglyphs related to metalwork are depicted on artifacts shaped like wallets.

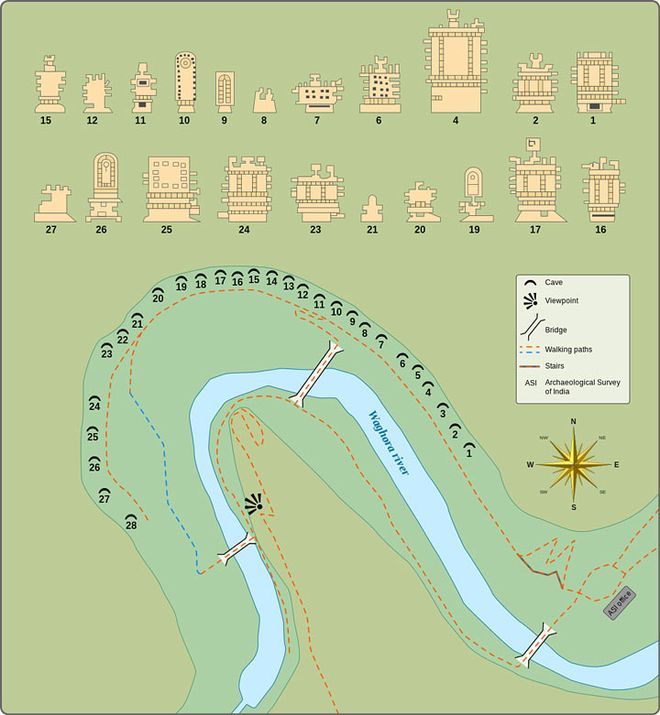

Hieroglyph: wallet: *dhōkka1 ʻ sacking, matting ʼ. 2. *dhōkha -- . 3. *dhōṅga -- 2. 4. *ḍhōkka -- 1. [Cf. *ṭōkka -- 1]1. Ext. -- ḍ -- : N. dhokro ʻ large jute bag ʼ, B. dhokaṛ; Or. dhokaṛa ʻ cloth bag ʼ; Bi. dhŏkrā ʻ jute bag ʼ; Mth. dhokṛā ʻ bag, vessel, receptacle ʼ; H. dhukṛī f. ʻ small bag ʼ; G. dhokṛũ n. ʻ bale of cotton ʼ; -- with -- ṭṭ -- : M. dhokṭī f. ʻ wallet ʼ; -- with -- n -- : G. dhokṇũ n. ʻ bale of cotton ʼ; -- with -- s -- : N. (Tarai) dhokse ʻ place covered with a mat to store rice in ʼ.2. L. dhohẽ (pl. dhūhī˜) m. ʻ large thatched shed ʼ.3. M. dhõgḍā m. ʻ coarse cloth ʼ, dhõgṭī f. ʻ wallet ʼ.4. L. ḍhok f. ʻ hut in the fields ʼ; Ku. ḍhwākā m. pl. ʻ gates of a city or market ʼ; N. ḍhokā (pl. of *ḍhoko) ʻ door ʼ; -- OMarw. ḍhokaro m. ʻ basket ʼ; -- N. ḍhokse ʻ place covered with a mat to store rice in, large basket ʼ.(CDIAL 6880) Rebus: dhokra kamar 'cire perdue, lost-wax casting metalworker' ![]() Stairs of Konar Sandal Ziggurat Stairs of Konar Sandal Ziggurat

The main part of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat of the Jiroft ancient site, located in the southern Iranian province of Kerman, has recently been excavated, the Persian service of CHN reported on Friday.

Before the discovery of the ziggurat in 2002, Chogha Zanbil, a major remnant of the Elamite civilization near Susa , was the only surviving ziggurat in Iran . Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat dates back to 1250 BCE.

“The main part of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat is the lower part and is 200 years older than the upper section. Thus, construction of the ziggurat was carried out in stages beginning in 2200 BCE,” said Professor Yusef Majidzadeh, the director of the archaeological team working at the site.

Built some time around 2100 BCE by king Ur-Nammu, the Ur Ziggurat is the oldest one in Mesopotamia , but the Konar Sandal Ziggurat is a century older than it, he added.

The Ur Ziggurat was built in honor of the god Sin in Ur , a Sumerian city on the Euphrates , in the south of modern-day Iraq . It was called 'Etemennigur', which means 'house whose foundation creates terror'.

“The archaeologists have determined the original shape of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat for restoration,” Majidzadeh said.

Jiroft came into the spotlight nearly four years ago when reports of extensive illegal excavations and plundering of the priceless historical items of the area by local people surfaced.

Since 2002, two excavation seasons have been carried out at the Jiroft site under the supervision of Majidzadeh, leading to the discovery of a ziggurat made of more than four million mud bricks dating back to about 2200 BCE.

Jiroft is one of the richest historical areas in the world, with ruins and artifacts dating back to the third millennium BCE. Over 100 historical sites are located along the approximately 400 kilometers of the Halil Rud riverbank.

Many Iranian and foreign experts see the findings in Jiroft as signs of a civilization as great as Sumer and ancientMesopotamia . Majidzadeh believes that Jiroft is the ancient city of Aratta , which was described as a great civilization in a Sumerian clay inscription.

Jiroft artifacts with Meluhha hieroglhyphs referencing dhokra kamar working with metals.

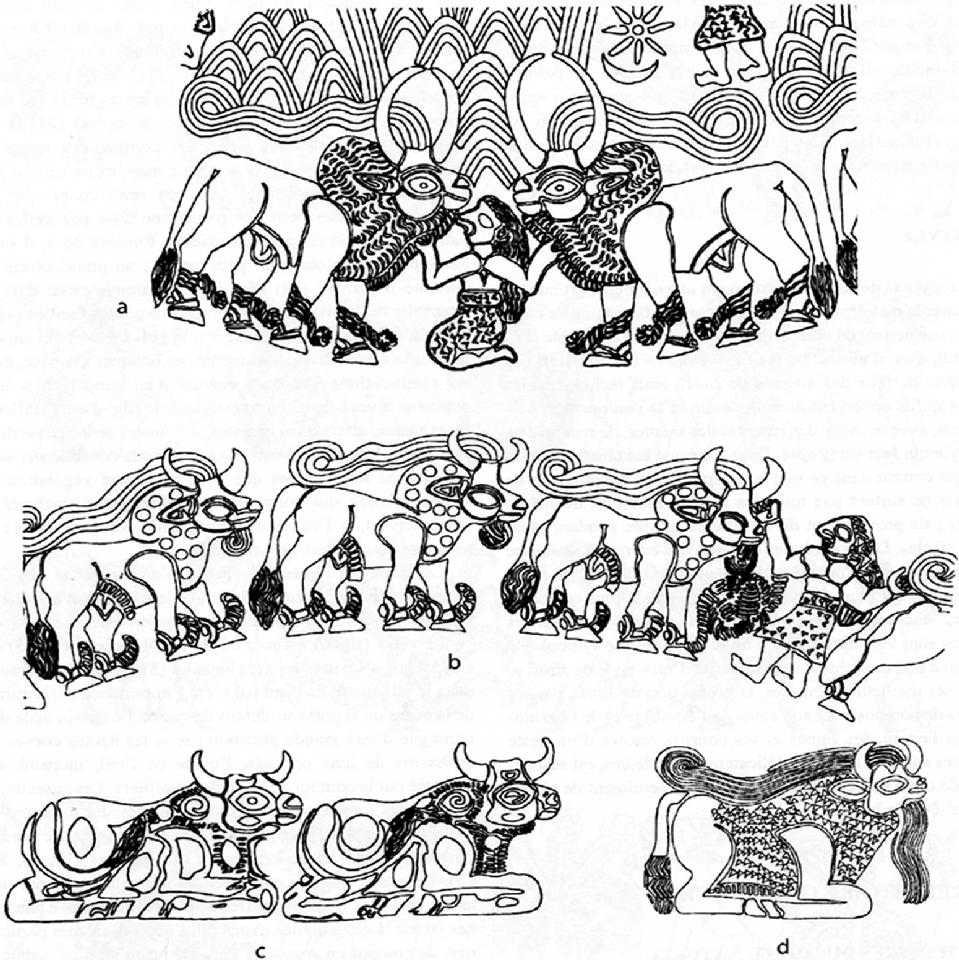

Dark grey steatite bowl carved in relief. Zebu or brahmani bull is shown with its hump back; a male figure with long hair and wearing akilt grasps two sinuous objects, representing running water, which flows in a continuous stream. Around the bowl, another similar male figure stands between two lionesses with their head turned back towards him; he grasps a serpent in each hand. A further scene (not shown) represents a prostrate bull which is being attacked by a vulture and a lion.

The zebu is reminiscent of Sarasvati Sindhu seals. The stone used, steatite, is familiar in Baluchistan and a number of vessels at the Royal Cemetery at Ur were made out of this material.

The bowl dates from c. 2700-2500 B.C. and the motif shown on it resembles that on a fragment of a green stone vase from one of the Sin Temples at Tell Asmar of almost the same date.

Khafajeh bowl; a man sitting, with his legs bent underneath, upon two zebu bulls. This evokes the proto-Elamite bull-man; the man holds in his hands streams of water and issurrounded by ears of corn. He has a crescent beside his head. On the other side of the bowl, a man is standing upon two lionesses and grasping two serpents. ![]() An Early Dynastic II votive plaque from the Inanna temple at Nippur VIII (after Pritchard, 1969: 356, no. 646). "It has something very Harappan about it also in the lower part depicting two 'unicorn' bulls around a tree. The six dots around the head of the Harappan hero, clearly visible in one seal (Mohenjodaro, DK 11794; cf. Mackay, 1937: II, pl. 84:75) may be compared to the six locks of hair characteristic of the Mesopotamian hero from Jemdet Nasr to Akkadian times (cf. Calmeyer, 1957-71: 373). From the Early Dynastic period onwards the scene usually comprises a man fighting with one or two bulls, and a bull-man fighting with one or two lions....North-west India of the third millennium BC can be considered as an integral, if marginal, part of the West Asian cultural area." (Parpola, A., New correspondences between Harappan and Near Eastern glyptic art, in: Bridget Allchin (ed.), South Asian Archaeology, 1981, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1984). An Early Dynastic II votive plaque from the Inanna temple at Nippur VIII (after Pritchard, 1969: 356, no. 646). "It has something very Harappan about it also in the lower part depicting two 'unicorn' bulls around a tree. The six dots around the head of the Harappan hero, clearly visible in one seal (Mohenjodaro, DK 11794; cf. Mackay, 1937: II, pl. 84:75) may be compared to the six locks of hair characteristic of the Mesopotamian hero from Jemdet Nasr to Akkadian times (cf. Calmeyer, 1957-71: 373). From the Early Dynastic period onwards the scene usually comprises a man fighting with one or two bulls, and a bull-man fighting with one or two lions....North-west India of the third millennium BC can be considered as an integral, if marginal, part of the West Asian cultural area." (Parpola, A., New correspondences between Harappan and Near Eastern glyptic art, in: Bridget Allchin (ed.), South Asian Archaeology, 1981, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1984).

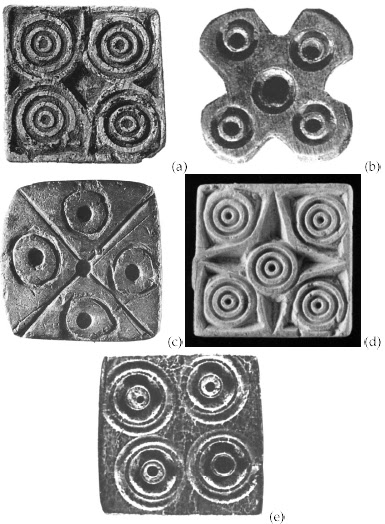

Finds at Atlyn-depe: ivory sticks and gaming pieces (?) obtained from Sarasvati Sindhu civilization; similar objects with dotted circles found in Mohenjodaro and Harappa. (Masson, VM, 1988, Altyn-depe, UPenn museum, p. 90)

Zebu draws the ratha with uṣas 'female sun divinity' called the spiked throne terracotta object. A pair of zebu bull heads flank the throne which is embellished with 'spikes' to signify sun's rays. I suggest that zebu is a hieroglyph metaphor to signify magnetite, ferrite ore.

![Image result for uṣa spiked throne bharatkalyan97]() ![]() Plate 7. Details of the zebu bull's head, with its painted and incised decoration. Pipal leaf motif is notable. Decoration on the bull is indication of a celebration. Just as decoration of a heifer (bull-calf?) with trefoils is also indicative of sacredness. The over all impression of the artifact is an exquisite expression of the life familiar to the artist. Plate 7. Details of the zebu bull's head, with its painted and incised decoration. Pipal leaf motif is notable. Decoration on the bull is indication of a celebration. Just as decoration of a heifer (bull-calf?) with trefoils is also indicative of sacredness. The over all impression of the artifact is an exquisite expression of the life familiar to the artist.

Note: The nostrils are painted with a red pigment. The practice of using red pigment is also noted on the 'priest' statuette. Trefoil glyphs on the 'priest' statuette were originally filled with red pigment. cf. http://www.harappa.com/indus/41.html http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2012/06/lady-of-spiked-throne-massimo-vidale.html

See: http://tinyurl.com/p3n28lfThat zebu, bos indicus, is an exclusive legacy of South Asia is proven by genetic studies. After the domestication of the zebu, bos indicus, deployment of the hierolyph of zebu on Indus Script Corpora is a significant advance in archaeometallurgy documentation.

The writing system depicting a hieroglyph multiplex of a zebu tied to a post with a bird perched on top is based on the rebus rendering of the Prakritam glosses: Hieroglyph: पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' Rebus: magnetite, citizen. baṭa 'quail' Rebus: baṭha'furnace'. Alternative: Hieroglyph: black drongo: పోలడు pōlaḍu rebus: पोलाद [ pōlāda ] n ( or P) Steel. पोलादी a Of steel. (Marathi) bulad 'steel, flint and steel for making fire' (Amharic); fUlAd 'steel' (Arabic)

The messaging on Nausharo pots of a magnetite furnace for metalwork continues on seals and tablets including copper plates as metalwork catalogues.

The Prakritam gloss पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' as hieroglyph is read rebus: pōḷa, 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide'; poliya 'citizen, gatekeeper of town quarter'.

Zebu also signifies a native metal blacksmith: another gloss for zebu: ad.ar d.an:gra (Santali); rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) d.han:gar ‘blacksmith’ (WPah.) aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada. Siddha_nti Subrahman.ya’ S’astri’s new interpretation of theAmarakos’a, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330). Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiramany ore. Ka. aduru native metal. Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron. (DEDR 192). ayas 'metal' (Rigveda); aya'iron' (Gujarati) Note: karba 'iron' is signified by hieroglyphs: karibha 'trunk of elephant' (Pali); ibha'elephant' (Samsritam). Thus, ajirda karba (Tulu) = aduru (aya) karba 'native metal iron' in semantic expansion of Prakritam in tune with archaeometallurgy advances in smelting, alloying and cire perduemetalcastings.

Hieroglyph: पोळ [pōḷa] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. பொலியெருது poli-y-erutu , n. < பொலி- +. 1. Bull kept for covering; பசுக்களைச் சினையாக்குதற் பொருட்டு வளர்க்கப்படும் காளை. (பிங்.) கொடிய பொலியெருதை யிருமூக்கிலும் கயி றொன்று கோத்து (அறப். சத. 42). 2. The leading ox in treading out grain on a threshing-floor; களத்துப் பிணையல்மாடுகளில் முதற்செல்லுங் கடா. (W.) பொலி முறைநாகு poli-muṟai-nāku, n. < பொலி + முறை +. Heifer fit for covering; பொலியக்கூடிய பக்குவமுள்ள கிடாரி. (S. I. I. iv, 102.)

Rebus 1: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide Fe3O4'.

Rebus 2: pol m. ʻgate, courtyard, town quarter with its own gate': Ka. por̤al town, city. Te. prōlu, (inscr.) pr̤ōl(u) city. ? (DEDR 4555) पोवळ or पोंवळ [ pōvaḷa or pōṃvaḷa ] f पोवळी or पोंवळी f The court-wall of a temple. (Marathi) *pratōlika ʻ gatekeeper ʼ. [pratōlī -- ] H. pauliyā, pol°, pauriyā m. ʻ gatekeeper ʼ, G. poḷiyɔ m.(CDIAL 8632) pratōlī f. ʻ gate of town or fort, main street ʼ MBh. [Cf. tōlikā -- . -- Perh. conn. with tōraṇa -- EWA ii 361, less likely with *ṭōla -- ] Pk. paōlī -- f. ʻ city gate, main street ʼ; WPah. (Joshi) prauḷ m., °ḷi f., pauḷ m., °ḷi f. ʻ gateway of a chief ʼ, proḷ ʻ village ward ʼ; H. paul, pol m. ʻ gate, courtyard, town quarter with its own gate ʼ, paulī f. ʻ gate ʼ; OG. poli f. ʻ door ʼ; G. poḷi f. ʻ street ʼ; M. pauḷ, poḷ f. ʻ wall of loose stones ʼ. -- Forms with -- r -- poss. < *pradura -- : OAw. paüri ʻ gatepost ʼ; H. paur, °rī, pãwar, °rī f. ʻ gate, door ʼ.WPah.poet. prɔ̈̄ḷ m., prɔḷo m., prɔḷe f. ʻ gate of palace or temple ʼ.(CDIAL 8633) Porin (adj.) [fr. pora=Epic Sk. paura citizen, see pura. Semantically cp. urbane>urbanus>urbs; polite= poli/ths>po/lis. For pop. etym. see DA i.73 & 282] belonging to a citizen, i. e. citizenlike, urbane, polite, usually in phrase porī vācā polite speech D i.4, 114; S i.189; ii.280=A ii.51; A iii.114; Pug 57; Dhs 1344; DA i.75, 282; DhsA 397. Cp. BSk. paurī vācā MVastu iii.322. Porisa2 (nt.) [abstr. fr. purisa, *pauruṣyaŋ, cp. porisiya and poroseyya] 1. business, doing of a man (or servant, cp. purisa 2), service, occupation; human doing, activity M i.85 (rāja˚); Vv 6311 (=purisa -- kicca VvA 263); Pv iv.324 (uṭṭhāna˚=purisa -- viriya, purisa -- kāra PvA 252). -- 2. height of a man M. i.74, 187, 365.(Pali) పౌరము [ pauramu ] pauramu. [Skt. from పుర.] adj. Belonging to a city or town (పురము.) పౌరసతులు the ladies of the place: citizens' wives. పౌరలోకము paura-lōkamu. n. The townsfolk, a body of citizens. పౌరుడు pauruḍu. n. A citizen. పౌరులు citizens, townsfolk.(Telugu)

वृषः 1 A bull; असंपदस्तस्य वृषेण गच्छतः Ku.5.8; Me.54; R.2.35; Ms.9.123. -2 The sign Taurus of the zodiac. -3 The chief or best of a class, the best of its kind; (often at the end of comp.); मुनिवृषः, कपिवृषः &c. -उत्सर्गः setting free a bull on the occasion of a funeral rite, or as a religious act generally; एकादशाहे प्रेतस्य यस्य चोत्सृज्यते वृषः । प्रेतलोकं परित्यज्य स्वर्गलोकं च गच्छति (Samskritam. Apte)

वृषोत्सर्ग [p=1012,2] m. letting loose a bull (or accord. to some , a bull and four heifers , as a work of merit esp. on the occasion of a श्राद्ध in honour of deceased ancestors) Gr2S. Pan5cat. RTL. 319 (Monier-Williams. Samskritam)

"The letting loose of a bull (vRshotsarga) stamped with Siva's trident -- in cities like Benares and Gaya is fraught with the highest merit. This setting free of a bull to roam about at will often takes place at zrAddhas." (Monier Monier-Williams, 1891, Brahmanism and Hinduism: or religious thought and life in Asia, Macmillan, p.319). In Hindu tradition, GRhyasUtra prescribe procedures for vRshotsarga.

"It is note-worthy that the details of the ceremony of setting a bull at liberty viz. the 'Vrshotsarga' in the Grhya-Sutras viz. S & P, in which it is described are almost identical (mutual borrowing or a common source are possibilities). On the Karttika full-moon day or on the day of the Asvayuja month falling under the Nakshtra RevatI, the fire is made to blaze in the midst of cows and Ajya oblations are sacrificed with ap propriate Mantras. Then he sacrifices from the Sthalipaka be longing to Pushan with an invocation to Pushan. Then he selects a bull of one, two or three colours or a red bull or one that leads the herd or is loved by the herd, perfect in all limbs and the finest in the herd, mumuring the Rudra-hymns. Then that bull is adorned, as also four of the finest young cows of the herd and then he says "This young bull, I give you as your husband; sporting with him, your lover, walk about etc." When the bull is in the midst of the cows, he recites over them the Rig-Verses X, 169. With the milk of all those cows he should cook milk-rice and feed the Brahmins with it. In the opinion of some (P) an animal is sacrificed in this rite, in which case the ritual is the same as that of the *sula-gava*." http://dli.gov.in/rawdataupload/upload/0113/986/RTF/00000141.rtf

Hieroglyph: black drongo: పోలడు pōlaḍu rebus: पोलाद [ pōlāda ] n ( or P) Steel. पोलादी a Of steel. (Marathi) bulad 'steel, flint and steel for making fire' (Amharic); fUlAd 'steel' (Arabic)

Hieroglyph: eagle పోలడు [ pōlaḍu ] , పోలిగాడు or దూడలపోలడు pōlaḍu. [Tel.] n. An eagle. పసులపోలిగాడు the bird called the Black Drongo. Dicrurus ater. (F.B.I.)(Telugu)

పసి (p. 730) pasi pasi. [from Skt. పశువు.] n. Cattle. పశుసమూహము, గోగణము. The smell of cattle, పశ్వాదులమీదిగాలి, వాసన. పసిపట్టు pasi-paṭṭu. To scent or follow by the nose, as a dog does a fox. పసిగొను to trace out or smell out. వాసనపట్టు. మొసలి కుక్కను పసిపట్టి when the crocodile scented the dog. పసులు pasulu. n. plu. Cattle, గోవులు. పసిగాపు pasi-gāpu. n. A herdsman, గోపకుడు పసితిండి pasi-tinḍi. n. A tiger, పెద్దపులి. పసులపోలిగాడు pasula-pōli-gāḍu. n. The Black Drongo or King crow, Dicrurusater. (F.B.I.) ఏట్రింత. Also, the Adjutant. తోకపసులపోలిగాడు the Raquet-tailed Drongo shrike. Jerdon. No. 55. 56. 59. కొండ పనులపోలిగాడు the White bellied Drongo, Dicrurus coerulescens. వెంటికపనుల పోలిగాడు the Hair-crested Drongo, Chibia hottentotta. టెంకిపనుల పోలిగాడు the larger Racket-tailed Drongo, Dissemurus paradiseus (F.B.I.) పసులవాడు pasula-vāḍu. n. A herdsman, గొల్లవాడు.

A Black drongo in Rajasthan state, northern India

Rebus: पोळ [ pōḷa ] 'magnetite', ferrous-ferric oxide Fe3O4 (Asuri)

Rebus: cattle festival: पोळ (p. 305) pōḷa m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. पोळा [ pōḷā ] m (पोळ) A festive day for cattle,--the day of new moon of श्रावण or of भाद्रपद. Bullocks are exempted from labor; variously daubed and decorated; and paraded about in worship. (Marathi) "Pola is a bull-worshipping festival celebrated by farmers mainly in the Indian state of Maharashtra (especially among the Kunbis). On the day of Pola, the farmers decorate and worship their bulls. Pola falls on the day of the Pithori Amavasya (the new moon day) in the month of Shravana (usually in August)." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pola_(festival) Festival held on the day after Sankranti ( = kANum) is called pōlāla paNDaga (Telugu). होळा (p. 526) hōḷā m (Intens. of होळी) A huge blazing and roaring fire. होळी (p. 527) hōḷī f (होलिका S) The name of a Rákshasí to whom this festival is addressed. 2 The pile (of wood, grass &c.) arranged to be kindled at the close of the festival of the होळी. 2 The festival of the होळी, or the season of it. It is held at the approach of the vernal equinox. It is comprehended within the first day (or the fifth day) and the day of full moon of the month Phálgun. The term is applied also to the day of full moon of Phálgun, and to that of the month Mágh. 3 Applied to the tree or stick which is planted or fixed in the centre of the pile. होळी करणें To burn the होळी,--to kindle the pile and close the festival. hōlā f. ʻ spring festival ʼ MW., hōlākā -- f. Rājat., hōlī- f. W. Pk. hōliyā -- f. ʻ spring festival ʼ, K. hūli f., S. horī f., P. horī, hollī f., Ku. holī, N. holi, hori (← Mth.), A. hâlī, B. holi, Or. huḷi, Bi. holī; OAw. horī ʻ pile of wood for burning at the spring festival ʼ; H. holī, horī f. ʻ the festival ʼ, G. M. hoḷī f. (CDIAL 14182) ![]() Toy animals made for the Pola festival especially celebrated by the Dhanoje Kunbis. (Bemrose, Colo. Derby - Russell, Robert Vane (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: volume IV. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. London: Macmillan and Co., limited. p. 40). Toy animals made for the Pola festival especially celebrated by the Dhanoje Kunbis. (Bemrose, Colo. Derby - Russell, Robert Vane (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: volume IV. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. London: Macmillan and Co., limited. p. 40).

Oxen pulled Bronze chariot found at Daimabad in Maharshtra Daimabad bronze chariot. c. 1500 BCE. 22X52X17.5 cm.

"Magnetite is a mineral, ferrous-ferric oxide, one of the three common naturally occurring iron oxides (chemical formula Fe3O4) and a member of the spinel group. Magnetite is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth.[Harrison, R. J.; Dunin-Borkowski, RE; Putnis, A (2002). "Direct imaging of nanoscale magnetic interactions in minerals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (26): 16556–16561] Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, and this was how ancient people first noticed the property of magnetism...Magnetite reacts with oxygen to produce hematite, and the mineral pair forms a buffer that can control oxygen fugacity."

"Magnetite is a mineral, one of the three common naturally occurring iron oxides (chemical formula Fe3O4) and a member of the spinel group. Magnetite is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth.[ Harrison, R. J.; Dunin-Borkowski, RE; Putnis, A (2002). "Direct imaging of nanoscale magnetic interactions in minerals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (26): 16556–16561. ] Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, and this was how ancient people first noticed the property of magnetism." http://www.pnas.org/content/99/26/16556.full.pdf loc.cit. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetite ![]()

Magnetite and pyrite from Piedmont, Italy

"The process by which lodestone is created has long been an open question in geology. Only a small amount of the magnetite on Earth is found magnetized as lodestone. Ordinary magnetite is attracted to a magnetic field like iron and steel is, but does not tend to become magnetized itself; it has too low a magnetic coercivity (resistance to demagnetization) to stay magnetized for long...The leading theory suggests that lodestones are magnetized by the strong magnetic fields surrounding lightning bolts."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lodestone See: http://www.phy6.org/earthmag/lodeston.htm

[quote] Magnetite, a ferrimagnetic mineral with chemical formula Fe3O4, one of several iron oxides, is one of the more common meteor-wrongs. Magnetite displays a black exterior and magnetic properties.

![]()

magnetite

Magnetite can be a found in a meteorite's crust. When a meteor enters the earth's atmosphere the rock's surface is ablated by ultra high temperatures. Before it hits the ground, the molten surface solidifies into a thin glassy coating, called fusion crust. Crystals of magnetite color the thin fusion crust black. (Magnetite streaks black - see photo below)

![lodestone]()

lodestone

A piece of intensely magnetic magnetite was used as an early form of magnetic compass. Iron, steel and ordinary magnetite are attracted to a magnetic field, including the Earth's magnetic field. Only magnetite with a particular crystalline structure, lodestone, can act as a natural magnet and attract and magnetize iron. The name "magnet" comes from lodestones found in a place called Magnesia. [unquote] http://meteorite-identification.com/Hot%20Rocks/magnetite.html

Ancient Blacksmiths: ukku pola (steel from magnetite)? Magnetite var. lodestone 5.0x4.5x3.5cm With nails and metal dust attached to it. ![]() Superb, mirror-like crystals of lustrous Magnetite covering one side of block of matrix. These Magnetite crystals are exceptionally sharp and well formed. 5 x 4 x 2 cm.A tool to use the magnetic qualities of iron is a lodestone (which is a natural magnetic iron oxide mineral). Such a tool could have enabled ancient blacksmiths to identify and distinguish a type if iron ore called ‘magnetite’ called in Meluhha: pola (which yields the Russian bulat steel) made from Latin wootz (Meluhha ukku)."In the Muslim world of the 9th-12th centuries CE, the production of fuladh, a Persian word, has been described by Al-Kindi, Al-Biruni and Al-Tarsusi, from narm-ahanand shaburqan, two other Persian words representing iron products obtained by direct reduction of the ore. Ahan means iron. Narm-ahan is a soft iron and shaburqan a harder one or able to be quench-hardened. Old nails and horse-shoes were also used as base for fuladh preparation. It must be noticed that, according to Hammer- Purgstall, there was no Arab word for steel, which explain the use of Persian words. Fuladh prepared by melting in small crucibles can be considered as a steel in our modem classification, due to its properties (hardness, quench hardened ability, etc.). The word fuladh means "the purified" as explained by Al-Kindi. This word can be found as puladh, for instance in Chardin (1711 AD) who called this product; poulad jauherder, acier onde, which means "watering steel", a characteristic of what was called Damascene steel in Europe."Known to ancient Greeks, magnetite was so-called because it was found in the lands of the Magnetes (Magnesia) in Thessaly. Ancient Indians (Bharatam Janam) called it पोळ [pōḷa] which gave the root for the famed crucible wootz steel called पोलाद [pōlāda] n ( or P) पोलादी 'steel'. Superb, mirror-like crystals of lustrous Magnetite covering one side of block of matrix. These Magnetite crystals are exceptionally sharp and well formed. 5 x 4 x 2 cm.A tool to use the magnetic qualities of iron is a lodestone (which is a natural magnetic iron oxide mineral). Such a tool could have enabled ancient blacksmiths to identify and distinguish a type if iron ore called ‘magnetite’ called in Meluhha: pola (which yields the Russian bulat steel) made from Latin wootz (Meluhha ukku)."In the Muslim world of the 9th-12th centuries CE, the production of fuladh, a Persian word, has been described by Al-Kindi, Al-Biruni and Al-Tarsusi, from narm-ahanand shaburqan, two other Persian words representing iron products obtained by direct reduction of the ore. Ahan means iron. Narm-ahan is a soft iron and shaburqan a harder one or able to be quench-hardened. Old nails and horse-shoes were also used as base for fuladh preparation. It must be noticed that, according to Hammer- Purgstall, there was no Arab word for steel, which explain the use of Persian words. Fuladh prepared by melting in small crucibles can be considered as a steel in our modem classification, due to its properties (hardness, quench hardened ability, etc.). The word fuladh means "the purified" as explained by Al-Kindi. This word can be found as puladh, for instance in Chardin (1711 AD) who called this product; poulad jauherder, acier onde, which means "watering steel", a characteristic of what was called Damascene steel in Europe."Known to ancient Greeks, magnetite was so-called because it was found in the lands of the Magnetes (Magnesia) in Thessaly. Ancient Indians (Bharatam Janam) called it पोळ [pōḷa] which gave the root for the famed crucible wootz steel called पोलाद [pōlāda] n ( or P) पोलादी 'steel'.पोलाद [ pōlāda ] n ( or P) Steel. पोलादी a Of steel. (Marathi) bulad 'steel, flint and steel for making fire' (Amharic); fUlAd 'steel' (Arabic)

The Marathi gloss pōlāda may be formed with pōḷa+hlād = magnetite ore + rejoice.

[HLĀD ʻ rejoice ʼ: āhlādayati,āhlādayati ʻ refreshes, gladdens ʼ MBh. [āhlāda -- m. ʻ joy ʼ, Pk. alhāya -- m.: √hlād] H. āhlānā, aihl°, alhānā intr. ʻ to rejoice ʼ.(CDIAL 1549) प्रह्रा prahrā (ह्ला hlā) दः dḥ प्रह्रा (ह्ला) दः 1 Great joy, pleasure, delight, happi- ness. प्रह्रा (ह्ला) दन a. Gladdening, delighting; प्रह्लादनं ज्योतिरजन्यनेन R.13.4. अग्निः agniḥ -प्रस्तरः [अग्निं प्रस्तृणाति अग्नेः प्रस्तरो वा] a flint, a stone producing fire.]

pola ‘magnetite ore’ (Munda. Asuri) See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/ancient-blacksmiths.html Three mineral ores: pola (magnetite), gota (laterite), bichi (hematite) -- all three Meluhha glosses -- are three varieties of minerals with sources for alloying metals. The importance of bichi (hematite) as a hieroglyph has been detailed.

Hieroglyph: baṭa 'quail'; bhaṭa 'furnace' (G.); baṭa 'a kind of iron' (Gujarati.) Alternative: Hieroglyph: black drongo: పోలడు pōlaḍu rebus: पोलाद [ pōlāda ] n ( or P) Steel. पोलादी a Of steel. (Marathi) bulad 'steel, flint and steel for making fire' (Amharic); fUlAd 'steel' (Arabic)

![Image result for painted jars nausharo indus]() Slip painted cylindrical jar, Kulli. Slip painted cylindrical jar, Kulli. ![]() The earliest animal figurines from Harappa are Early Harappan (Ravi Phase, Period 1 and Kot Diji Phase, Period 2) zebu figurines. They are typically very small with joined legs and stylized humps. A few of these zebu figurines have holes through the humps that may have allowed them to be worn as amulets on a cord or a string. One Early Harappan zebu figurine was found with the remains of a copper alloy ring still in this hole. The earliest animal figurines from Harappa are Early Harappan (Ravi Phase, Period 1 and Kot Diji Phase, Period 2) zebu figurines. They are typically very small with joined legs and stylized humps. A few of these zebu figurines have holes through the humps that may have allowed them to be worn as amulets on a cord or a string. One Early Harappan zebu figurine was found with the remains of a copper alloy ring still in this hole.Approximate dimensions (W x H (L) x D) of the uppermost figurine: 1.2 x 3.3 x 2.8 cm. "Slide 34. Zebu figurine with painted designs from Harappa. Other animal and sometimes anthropomorphic figurines are decorated with black stripes and other patterns, and features such as eyes are also sometimes rendered in pigment. Figurines of cattle with and without humps are found at Indus sites, possibly indicating that multiple breeds of cattle were in use. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D): 3.9 x 8.5 x 5.5 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)."http://www.harappa.com/figurines/34.html ![]() After Figure 1. Major domestic cattle species: (a) Spanish Tudanca taurine and (b) Pullikulam zebu bull (photographs by Marleen Felius and Anno Fokkinga, 2008, 2005). After Fig. 7 Pictorial evidence of the origin and dispersal of zebu. (a) Harappa seal (National Museum, India, [70]), 5000–3500 BP; (b) detail of cylindrical chlorite vessel (Mesopotamia (mid-5th millennium BP, The British Museum, London); (c) detail of conic object from Tarut Island near the Eastern coast of the Arabian peninsula (Metropolitan Museum, NY) and (d) detail of a painting: inspection of cattle belonging to Nebamun, Thebes,ca. 3400 BP, The British Museum, London). http://www.mdpi.com/1424-2818/6/4/705/htm Marleen Felius et al, 2014, On the history of cattle genetic resources, Diversity 2014, 6(4), 705-750 "Around 2000 years after the taurine domestication, zebu was domesticated in the Indus Valley at the edge of the Indian Desert. Fossil remains attributed to zebu have been found in Mehrgarh, a proto-Indus culture site in Baluchistan in southwest Pakistan and were dated at 8000 BP." ![]() "Bull seal, Harappa. The majestic zebu bull, with its heavy dewlap and wide curving horns is perhaps the most impressive motif found on the Indus seals. Generally carved on large seals with relatively short inscriptions, the zebu motif is found almost exclusively at the largest cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. The rarity of zebu seals is curious because the humped bull is a recurring theme in many of the ritual and decorative arts of the Indus region, appearing on painted pottery and as figurines long before the rise of cities and continuing on into later historical times. The zebu bull may symbolize the leader of the herd, whose strength and virility protects the herd and ensures the procreation of the species or it stands for a sacrificial animal. When carved in stone, the zebu bull probably represents the most powerful clan or top officials of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. Harappa Archaeological Research Project."http://www.harappa.com/indus/27.html "Bull seal, Harappa. The majestic zebu bull, with its heavy dewlap and wide curving horns is perhaps the most impressive motif found on the Indus seals. Generally carved on large seals with relatively short inscriptions, the zebu motif is found almost exclusively at the largest cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. The rarity of zebu seals is curious because the humped bull is a recurring theme in many of the ritual and decorative arts of the Indus region, appearing on painted pottery and as figurines long before the rise of cities and continuing on into later historical times. The zebu bull may symbolize the leader of the herd, whose strength and virility protects the herd and ensures the procreation of the species or it stands for a sacrificial animal. When carved in stone, the zebu bull probably represents the most powerful clan or top officials of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. Harappa Archaeological Research Project."http://www.harappa.com/indus/27.html![]() "Slide 68. Wheeled zebu figurine from Harappa. A small subset of the figurines from Harappa originally had wheels. Of the many small terracotta wheels found at Harappa, at least some must have been intended for these wheeled objects. One style of wheeled figurine has lateral holes for the axles through the bottom of the torso. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D): 5.9 x 6.2 x 8.7 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)." http://www.harappa.com/figurines/68.html

I suggest that the birds signified on the following two storage pots of Nausharo signify black drango birds. The characteristic feature of the characteristic outward-curving rectrices (feathers on the tail), the black drango is also called fork-tailed drongo. The Meluhha word for a black drango is pōlaḍu. The word is a phonetic reinforcing deterinant of the Meluhha word which signifies a zebu. The signifier Meluhha word for a zebu is: पोळ pōḷa. Thus, both the hieroglyphs -- black drogon and zebu-- signify the word pōḷa read rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore'.

![]() ![]() Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8.

![]() Ceramic from Nausharo showing transition from Early to Mature Phase of Sarasvati Civilization (Image after Jarrige, J.F., 1989, Excavations at Nausharo 1987-88. Pakistan Archaeology 24: 21-67.) Ceramic from Nausharo showing transition from Early to Mature Phase of Sarasvati Civilization (Image after Jarrige, J.F., 1989, Excavations at Nausharo 1987-88. Pakistan Archaeology 24: 21-67.)

Leopards weight from Shahi-Tump (Baluchistan) made using cire perdue technique. "The artefact was discovered in a grave, in the Kech valley, in Balochistan, southern part of present Pakistan. It belongs to the Shahi Tump - Makran civilisation (end of 4th millennium -- beginning of 3rd millennium BCe). Ht. 200 mm. weight: 13.5 kg. The shell has been manufactured by lost-wax foundry of a copper alloy (12.6%b, 2.6%As), then it has been filled up through lead (99.5%) foundry. The shell is engraved with figures of leopards hunting wild goats, made of polished fragments of shellfishes. No identification of the artefact's use has been given. (Scientific team: B. Mille, D. Bourgarit, R. Besenval, Musee Guimet, Paris)." Mille, B., R. besenval, D. Bourgarit, Early lost-wax casting in Balochistan (Pakistan): the 'Leopards Weight' from Shahi-Tump in Persiens antike Pracht, Bergau-Handwerk-Archaologie, T. Stollner, R. Slotta, A. Vatandoust, A. ed., p. 274-80. Bouchum: Deutsches Bergbau Museum, 2004.

Mille B., D. Bourgarit, R. Besenval, 2005, Metallurgical study of the 'Leopards Weight' from Shahi-Tump (Pakistan) in South Asian Archaeology 2001, C. Jarrige, V. Lefevre, ed., p. 237-244. Paris: Editions Recherches sur les Civilisations, 2005. Bourgarit, D., N. Taher, B. Mille & J.-P. Mohen Copper Metallurgy in the Kutch (India) during the Indus Civilization: First Results from Dholavira in South Asian Archaeology 2001, C. Jarrige, V. Lefevre, ed., p. 27-34. Paris: Editions Recherches sur les Civilisations, 2005.

![]()

Hieroglyph: leopard: kolha Rebus: kolhe 'smelter'. kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Te.) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.)Pk. kolhuya -- , kulha — m. ʻ jackal ʼ < *kōḍhu -- ; H.kolhā, °lā m. ʻ jackal ʼ, adj. ʻ crafty ʼ; G. kohlũ, °lũ n. ʻ jackal ʼ, M. kolhā, °lā m. krōṣṭŕ̊ ʻ crying ʼ BhP., m. ʻ jackal ʼ RV. = krṓṣṭu — m. Pāṇ. [√kruś] Pa. koṭṭhu -- , °uka — and kotthu -- , °uka — m. ʻ jackal ʼ, Pk. koṭṭhu — m.; Si. koṭa ʻ jackal ʼ, koṭiya ʻ leopard ʼ GS 42 (CDIAL 3615). कोल्हा [ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [ kōlhēṃ ] A jackal (Marathi) Rebus: kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pañcaloha’ (Ta.)

Hieroglyph: kāṇḍa'water' Rebus: khāṇḍā'metalware, pots and pans, tools'

Hieroglyph: dhanga 'mountain range' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' adar ḍangra ‘zebu or humped bull’; ḍangar ‘bull’ Rebus: adar ḍhangar 'native metal-smith'.

Rebus: ḍangar ‘blacksmith’; aduru native metal (Kannada). Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron (DEDR 192). aduru =gaṇiyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya śastri’s New interpretation of the Amarakośa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330) aduru ‘native metal’ (Kannada); ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi)![]()

Hieroglyph: nAga 'snake' Rebus; nAga 'lead'

Hieroglyph: kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

Hieroglyph: kola ‘woman’ kuṛī f. ʻ girl’ Rebus: kol ‘working in iron’

Hieroglyph: poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite' dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' Hieroglyph: bichi 'scorpion' Rebus: bica 'sand stone ore'; meṛed-bica 'iron stone-ore' (Santali. Munda)

Hieroglyph: OP. koṭhārī f. ʻ crucible' Rebus: kuṭhārī 'granary, room' (Hindi)

Hieroglyph: meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho. Munda)

Indo-Europeans domesticated the cow, the bull and the horse. Root? gu̯au/-gu̯ou-: Sanskrit go-, Avestan gāu-, Tocharian keu /ko, Armenian kov, Lithuanian gùovs, German Kuh, Irish bó, all for 'cow', Albanian ka/kau, Greek βοῦς, 'ox, cow', Latin bōs, bovis, Croatian and Serbian vo, 'ox'. See discussions at http://new-indology.blogspot.in/

Lapis lazuli stamp seal. Behind the man, drummer, are a stream, a long-horned, bearded goat above a zebu. Mountain range with a line of over 15 notches and a circle on top register. Bronze Age, about 2400-2000 BCE

From the ancient Near East British Museum. Height: 3.100 cm Thickness: 2.500 cm

Width: 4.000 cm ME 1992-10-7,1 Room 52: Ancient Iran This stamp seal was originally almost square, but because of damage one corner is missing. Originally two figures faced each other. The one on the left has largely disappeared. On the right is a man with his legs folded beneath him. It is suggested that at the top are rain clouds and rain or a fenced enclosure. Behind the man are a long-horned goat above a zebu. This last animal is related in style to similar creatures depicted on seals from the Indus Valley civilization, which was thriving at this time. There were close connections between the Indus Valley civilization and eastern Iran. One of the prized materials that was traded across the region was lapis lazuli, the blue stone from which this seal is made. The Sar-i Sang mines in the region of Badakhshan in north-east Afghanistan were probably the source for all lapis lazuli used in the ancient Near East. From here it was carried across Iran, where several lapis working sites have been discovered, and on to Mesopotamia and Egypt. Another source for lapis lazuli exists in southern Pakistan (a region of the Indus Valley civilization) but it is unclear if they were mined at the time of this seal. D. Collon, 'Lapis lazuli from the east: a stamp seal in the British Museum', Ancient Civilizations from Scy, 5/1 (1998), pp. 31-39 The hieroglyph: mountain-range signifies: ḍāṅro 'blacksmith' (Nepali)(CDIAL 5524) dhangar, 'blacksmith' (Hindi) Or. dhāṅgaṛ ʻ young servant, herdsman, name of a Santal tribe ʼ, dhāṅgaṛā ʻ unmarried youth ʼ, °ṛī ʻ unmarried girl ʼ, dhāṅgarā ʻ youth, man ʼ; H. dhaṅgar m. ʻ herdsman ʼ, dhã̄gaṛ, °ar m. ʻ a non-- Aryan tribe in the Vindhyas, digger of wells and tanks ʼ (CDIAL 5524) S. ṭakuru m. ʻ mountain ʼ, ṭakirī f. ʻ hillock ʼ, ṭākara f. ʻ low hill ʼ, ṭākirū m. ʻ mountaineer ʼ; N. ṭākuro, °ri ʻ hill top ʼ K. ḍȧki f. ʻ hill, rising ground ʼ. -- Ext. -- r -- : K. ḍakürü f. ʻ hill on a road ʼ. Ext. -- r -- : Pk. ḍaggara -- m. ʻ upper terrace of a house ʼ; M. ḍagar f. ʻ little hill, slope ʼ. Ku. ḍã̄g, ḍã̄k ʻ stony land ʼ; B. ḍāṅ ʻ heap ʼ, ḍāṅgā ʻ hill, dry upland ʼ; H. ḍã̄g f. ʻ mountain -- ridge ʼ; M. ḍã̄g m.n., ḍã̄gaṇ, °gāṇ, ḍãgāṇ n. ʻ hill -- tract ʼ. -- Ext. -- r -- : N. ḍaṅgur ʻ heap ʼ. M. ḍũg m. ʻ hill, pile ʼ, °gā m. ʻ eminence ʼ, °gī f. ʻ heap ʼ. -- Ext. -- r -- : Pk. ḍuṁgara -- m. ʻ mountain ʼ; Ku. ḍũgar, ḍũgrī; N. ḍuṅgar ʻ heap ʼ; Or. ḍuṅguri ʻ hillock ʼ, H. ḍū̃gar m., G. ḍũgar m., ḍũgrī f. S. ḍ̠ū̃garu m. ʻ hill ʼ, H. M. ḍõgar m. Pa. tuṅga -- ʻ high ʼ; Pk. tuṁga -- ʻ high ʼ, tuṁgĭ̄ya -- m. ʻ mountain ʼ; K. tŏng, tọ̆ngu m. ʻ peak ʼ, P. tuṅg f.; A. tuṅg ʻ importance ʼ; Si. tun̆gu ʻ lofty, mountain ʼ. -- Cf. uttuṅga -- ʻ lofty ʼ MBh. K. thọ̆ngu m. ʻ peak ʼ. H. dã̄g f. ʻ hill, precipice ʼ, dã̄gī ʻ belonging to hill country ʼ. S.kcch. ḍūṅghar m. ʻ hillock ʼ.(CDIAL 5423) Rebus: Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ; N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ(Nepali)(CDIAL 5524) ṭhakkura m. ʻ idol, deity (cf. ḍhakkārī -- ), ʼ lex., ʻ title ʼ Rājat. [Dis- cussion with lit. by W. Wüst RM 3, 13 ff. Prob. orig. a tribal name EWA i 459, which Wüst considers nonAryan borrowing of śākvará -- : very doubtful] Pk. ṭhakkura -- m. ʻ Rajput, chief man of a village ʼ; Kho. (Lor.) takur ʻ barber ʼ (= ṭ° ← Ind.?), Sh. ṭhăkŭr m.; K. ṭhôkur m. ʻ idol ʼ ( ← Ind.?); S. ṭhakuru m. ʻ fakir, term of address between fathers of a husband and wife ʼ; P. ṭhākar m. ʻ landholder ʼ, ludh. ṭhaukar m. ʻ lord ʼ; Ku. ṭhākur m. ʻ master, title of a Rajput ʼ; N. ṭhākur ʻ term of address from slave to master ʼ (f. ṭhakurāni), ṭhakuri ʻ a clan of Chetris ʼ (f. ṭhakurni); A. ṭhākur ʻ a Brahman ʼ, ṭhākurānī ʻ goddess ʼ; B. ṭhākurāni, ṭhākrān, °run ʻ honoured lady, goddess ʼ; Or. ṭhākura ʻ term of address to a Brahman, god, idol ʼ, ṭhākurāṇī ʻ goddess ʼ; Bi. ṭhākur ʻ barber ʼ; Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. ṭhākur ʻ lord, master ʼ; H. ṭhākur m. ʻ master, landlord, god, idol ʼ, ṭhākurāin, ṭhā̆kurānī f. ʻ mistress, goddess ʼ; G. ṭhākor, °kar m. ʻ member of a clan of Rajputs ʼ, ṭhakrāṇī f. ʻ his wife ʼ, ṭhākor ʻ god, idol ʼ; M. ṭhākur m. ʻ jungle tribe in North Konkan, family priest, god, idol ʼ; Si. mald. "tacourou"ʻ title added to names of noblemen ʼ (HJ 915) prob. ← Ind. Garh. ṭhākur ʻ master ʼ; A. ṭhākur also ʻ idol ʼ (CDIAL 5488) Two hieroglyphs on the lapis-lazuli stamp seal are: zebu and markhor. Hieroglyph: poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite' Hieroglyph: miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ Rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.Munda) Hieroglyph: Bi. mẽṛhwā ʻ a bullock with curved horns like a ram's ʼ; M. mẽḍhrū̃ n. ʻ sheep ʼ.(CDIAL 10311) mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4, miṇḍha -- 2, °aka -- , mēṭha -- 2,mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2, °aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r-- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ] Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- ,meṁḍha -- (°ḍhī -- f.), °ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (°dhiā -- f.), °aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇKal.rumb. amŕn/aŕə ʻ sheep ʼ (a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻ ram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*ll ʻ ram ʼ AO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻ ram ʼ,miṇḍṓl m. ʻ yearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m., °ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho,meṛo ʻ ram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāg ʻ ram ʼ ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., °ṛi f., Or.meṇḍhā, °ḍā m., °ḍhi f.,H. meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M. mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā.2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ.(CDIAL 10310) <menDa>(A) {N} ``^sheep''. *Des.<meNDa>(GM) `sheep'. #21810<meD>(:) <arij=meD>(Z),,<ari?=me?n>(A) {N} ``^female ^kid''. ^goat. #3022.<kin=meD>(Z) {N} ``^male ^goat, billy goat''. |<kin> `prefix used in names of male animals'. #17072. <auG kinme?n>(A) {N} ``^nanny ^goat''. |<auG> `mother'. #3729.(Gorum) I suggest an alternative possibility that the gloss 'med' is an adaptation of the Meluhhan gloss vividly identified in Munda languages. meḍ ‘body’ Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) Santali glosses: Wilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream: Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M). Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'. Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'. ~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M). Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'. Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'. KW <i>mENhEd</i> @(V168,M080) http://www.ling.hawaii.edu/austroasiatic/AA/Munda/ETYM/Pinnow&Munda — Slavic glosses for 'copper' Мед [Med]Bulgarian Bakar Bosnian Медзь [medz']Belarusian Měď Czech Bakar Croatian KòperKashubian Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian Miedź Polish Медь [Med']Russian Meď Slovak BakerSlovenian Бакар [Bakar]Serbian Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote] http://www.vanderkrogt.net/elements/element.php?sym=Cu Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'. One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’. ![]() In this hieroglyph multiplex on the lapis-lazuli stamp seal, there are three hieroglyph components: 1. roundish ball; 2. notches (over 15 short strokes down a line); 3. mountain range. In this hieroglyph multiplex on the lapis-lazuli stamp seal, there are three hieroglyph components: 1. roundish ball; 2. notches (over 15 short strokes down a line); 3. mountain range.