Kassite kudurrus signify many Indus Script hieroglyphs/hypertexts as sacred memories from the Script tradition. This hypothesis is validated in this monograph from the evidence of symbols used on about 50 kudurrus from the Bronze Age Ancient Near East sites including Susa.

Background note on cultural contacts between Indo-Aryan and Kassites/Mitanni

"That there was a migration of Indo-European speakers, possibly in waves, dating from the 2nd millennium bce, is clear from archaeological and epigraphic evidence in western Asia. Mesopotamia witnessed the arrival about 1760 bce of the Kassites, who introduced the horse and the chariot and bore Indo-European names. A treaty from about 1400 bce between the Hittites, who had arrived in Anatolia about the beginning of the 2nd millennium bce, and the Mitanni empire invoked several deities—Indara, Uruvna, Mitira, and the Nasatyas (names that occur in the Rigveda as Indra, Varuna, Mitra, and the Ashvins). An inscription at Bogazköy in Anatolia of about the same date contains Indo-European technical terms pertaining to the training of horses, which suggests cultural origins in Central Asia or the southern Russian steppes. Clay tablets dating to about 1400 bce, written at Tell el-Amarna (in Upper Egypt) in Akkadian cuneiform, mention names of princes that are also Indo-European."

One suggestion is that Kassites are Kāśyas, the founders of Kāśī, the region of Vāranāsi first mentioned in the Paippalada version of the Atharvaveda. "...some Kassite king names, which are evidently Indic (for example: Shuriash = Surya, Maruttash = Marut, Inda-Bugash = Indra-Bhaga), we can understand that they were also influenced by Hurrians or perhaps by the Medes, that in a later period were the owners of the Zagros and appointed the Magi as their priestly caste. Such kind of alliances between Sumerian/Subarian tribes and Indo-Aryan peoples seem to have been very common, and even achieved in taking control of the whole Mesopotamia during that period: the Kassite kingdom in the south preceded about 90 years the Mitanni kingdom in the north, and survived it for other 90 years." http://www.imninalu.net/myths-Huns.htm "The fifth king among the Kassite dynasty took the name Abirattas’ (abhi-ratha ‘facing chariots (in battle)’. (T. Burrow, The Sanskrit Language , London, Faber and Faber, 1955)...Mr. Kak in his paper makes a number of points: a) Following the collapse of the Sarasvati – river based economy around1900 BC, groups of Indians might have moved West and that might explain the presence of the Indic Kassites and the Mitanni in West Asia .

b) The old Vedic religion survived for a fairly long time in corners of Iran. The evidence of its survival comes from the daiva-inscription of Khshayarshan (Xerxes) (486-465 BC).

c) The ruling groups-Kassite and Mitanni – represented a minority in a population that spoke deferent languages. They, however, remained connected to their Vedic traditions. They were neighbors to the pre-Zoroastrian Vedic Iran . In addition, there were other Vedic religion groups in the intermediate region ofIran which itself consisted of several ethnic groups.

d) As per the Mitanni documents , the pre-Zorastrian religon in Iran included Varuna. Since Mitra and Varuna are partners in the Vedas, the omission of Varuna from the Zoroastrian lists indicates that Zarathushtra might be from the borderlands of the Vedic world where the Vedic system was not fully in place. e) The pre-Zoroastrian religion of is clearly Vedic. Zarathushtra’s innovation lay in his emphasis on the dichotomy of good and bad The Zoroastrian innovations did not change the basic Vedic character of the culture in Iran. The worship ritual remained unchanged, as was the case with basic conceptions related to divinity and the place of man." https://sreenivasaraos.com/2012/08/31/the-rig-veda-and-the-gathas-revisited/comment-page-1/

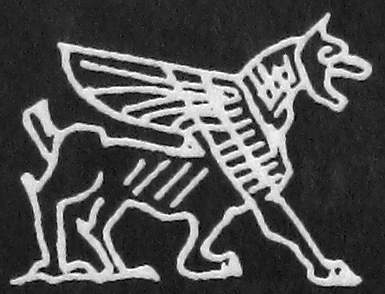

There is a reference to a wheelwright (chariot-maker) in a Susa sculptural frieze with Indus Script hypertext expressions.

kātī, 'spinner' rebus: khātī 'wheelwright'. The fish is ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati)ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda) baṭa 'six' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'. kola 'tiger' (see tiger paws of stools) rebus: kol 'working in iron'.

A fragment called 'spinner' is a relief of bitumen mastic from Susa. Young woman spinning and servant holding a fan. Fragment of a relief known as "The spinner". Bitumen mastic, Neo-Elamite period (8th century B.C.–middle of the 6th century B.C.). Found in Susa. F ig. 141 La Fileuse (Lady spinning) Bitumen compound. H 9.3 cm. W. 13 cm. Neo-Elamite period, ca. 8th -7th century BCE. Susa. Sb 2834 (Louvre Museum) Excavated by J. de Morgan. Sb2834. http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/spinner

The plain-text message of the sculptural frieze is: copper alloy metal mintwork of Meluhha wheelwright

Hieroglyph (cipher-text): Spinner (kātī) lady rebus khātī 'wheelwright‘

kola ‘tiger’rebus: kol ‘working in iron’ kolhe ‘smelter’

kulya 'fly whisk' rebus: kulya n. ʻ receptacle for burnt bones of a corpse ʼ MBh., A. kulā ʻwinnowingfan, hood of a snake ʼ; B. kul, °lā ʻ winnowing basket or fan ʼ; Or.kulā ʻ winnowing fan ʼ, °lāi ʻsmall do. ʼ; Si. kulla, st. kulu -- ʻ winnowing basket or fan ʼ.(CDIAL 3350) Rebus: kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron, blacksmith'. kolhe ‘smelter’

Malt. kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) khāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Marathi)

Hieroglyph: Pk. ṭaṁka -- m., °kā -- f. ʻ leg ʼ, S. ṭaṅga f., L. P. ṭaṅg f., Ku. ṭã̄g, N. ṭāṅ; Or. ṭāṅka ʻ leg, thigh ʼ, °ku ʻ thigh, buttock ʼ. 2. B. ṭāṅ, ṭeṅri ʻ leg, thigh ʼ; Mth. ṭã̄g, ṭãgri ʻ leg, foot ʼ; Bhoj. ṭāṅ, ṭaṅari ʻ leg ʼ, Aw. lakh. H. ṭã̄g f.; G. ṭã̄g f., °gɔ m. ʻ leg from hip to foot ʼ; M. ṭã̄g f. ʻ leg ʼ(CDIAL 5428).Rebus: A. ṭāṅī ʻ wedge ʼ ṭaṅkaśālā -- , ṭaṅkakaś° f. ʻ mint ʼ lex. [ṭaṅka -- 1, śāˊlā -- ] N. ṭaksāl, °ār, B. ṭāksāl, ṭã̄k°, ṭek°, Bhoj. ṭaksār, H. ṭaksāl, °ār f., G. ṭãksāḷ f., M. ṭã̄ksāl, ṭāk°, ṭãk°, ṭak°. -- Deriv. G. ṭaksāḷī m. ʻ mint -- master ʼ, M. ṭāksāḷyā m. Brj. ṭaksāḷī, °sārī m. ʻ mint -- master ʼ. (CDIAL 5434)

aya, ayo ‘fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' PLUS khambhaṛā ʻfish-finʼ rebus: kammaṭa 'coiner, coinage, mint (Kannada) Note: कान्त kānta -अयसम् the loadstone ‘magnetite’; कृष्ण-अयसम्,’crude or black iron’; लोहा* यस ‘any metal mixed with copper , (or) copper’ Br. Ka1tyS3r. लोहित lōhita -अयस् n. copper; -कृष्ण a. dark-red. Thus, ayas means ‘iron, metal’.

baṭa six' Sh.gil. băṭ m. ʻstoneʼ, koh.băṭṭ m., jij. baṭ, pales. baṭ ʻmillstoneʼ; K. waṭh, dat. °ṭas m. ʻround stoneʼ, vüṭü f. ʻsmall do.ʼ; L. vaṭṭā m. ʻstoneʼ, khet. vaṭ ʻrockʼ; P. baṭṭ m. ʻa partic. weightʼ, vaṭṭā, ba°m. ʻstoneʼ, vaṭṭī f. ʻpebbleʼ; WPah.bhal. baṭṭ m. ʻsmall round stoneʼ; Or. bāṭi ʻstoneʼ; Bi. baṭṭā ʻstone roller for spices, grindstoneʼ. [CDIAL 11348] rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace‘. Numeral bhaṭa 'six' is an Indus Script cipher, rebus bhaṭa ‘furnace’; baṭa 'iron'.

This relief has remarkable Indus Script hieroglyphs and has been called a Rosetta Stone of Indus Script cipher. One characteristic feature of the hieroglyph-multiplex is the use of a numerical semantic determinative. Six round objects are shown on a fish. In this pictorial, fish is a hieroglyph. Numeral six is a hieroglyph. Together, the Indus Script cipher is: aya 'fish' Rebus: ayas 'metal' goṭ 'round' Rebus: khoṭ 'alloy' PLUS bhaṭa 'six' Rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace.' Thus, the hieroglyph-multiplex proclaims the message: aya khoṭ bhaṭa

'metal (alloy) furnace'. Similar examples of the significance of 'six' numeral as a cipher from Ancient Near East are presented to signify phrases such as: meḍ bhaṭa 'iron furnace'. करडा karaḍā bhaṭa 'hard alloy furnace'.

Ancillotti demonstrate that Kassite is originally an Indo-Aryan language. (A. Ancillotti, La lingua dei Cassiti, Milan, 1981.) (Encyclopaedia Iranica does not find this convincing).

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kassites However, Indo-Iranian immigrations are noted:"Early impact of an immigrating Indo-Iranian group is suggested by a small, but linguistically and culturally significant, number of terms. These include šuriias “sun god,” Old Indo-Aryan *sūrya, and the personal name Abi-rattaš, with Indo-Iranian *ratha “chariot,” which reflects the new technology of warfare. Otherwise the linguistic affiliation of these peoples is uncertain." http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iran-vii5-kassite The association of Kassites and Indo-Aryans is clearly related to horse-riding and riding chariots (as noted also in the Indo-Aryan manual on horse-trainining by Kikkuli). "Kikkuli was the Hurrian "master horse trainer" (assussanni, virtually Sanskrit aśva-sana-) of the land Mitanni" (LÚA-AŠ-ŠU-UŠ-ŠA-AN-NI ŠA KUR URUMI-IT-TA-AN-NI) and author of a chariot horse training text written in the Hittite language, dating to the Hittite New Kingdom (around 1400 BCE). The text is notable both for the information it provides about the development of Indo-European languages and for its content...CTH 284 consists of four well preserved tablets or a total of 1080 lines. The text is notable for its Mitanni (Indo-Aryan) loanwords, e.g. the numeral compounds aiga-, tera-, panza-, satta-, nāwa-wartanna ("one, three, five, seven, nine intervals",[11] virtually Vedic eka-, tri-, pañca- sapta-, nava-vartana. Kikkuli apparently was faced with some difficulty getting specific Mitannian concepts across in the Hittite language, for he frequently gives a term such as “Intervals” in his own language (somewhat similar to Vedic Sanskrit), and then states, “this means…” and explained it in Hittite" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kikkuli This is consistent with the postulate of an Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni. "Some theonyms, proper names and other terminology of the Mitanni are considered to form (part of) an Indo-Aryan superstrate, suggesting that an Indo-Aryan elite imposed itself over the Hurrian population in the course of the Indo-Aryan expansion....Sanskritic interpretations of Mitanni names render Artashumara (artaššumara) as Arta-smara "who thinks of Arta/Ṛta" (Mayrhofer II 780), Biridashva (biridašṷa, biriiašṷa) as Prītāśva "whose horse is dear" (Mayrhofer II 182), Priyamazda (priiamazda) as Priyamedha "whose wisdom is dear" (Mayrhofer II 189, II378), Citrarata as citraratha "whose chariot is shining" (Mayrhofer I 553), Indaruda/Endaruta as Indrota "helped by Indra" (Mayrhofer I 134), Shativaza (šattiṷaza) as Sātivāja "winning the race price" (Mayrhofer II 540, 696), Šubandhu as Subandhu 'having good relatives" (a name in Palestine, Mayrhofer II 209, 735), Tushratta (tṷišeratta, tušratta, etc.) as *tṷaišaratha, Vedic Tveṣaratha "whose chariot is vehement" (Mayrhofer I 686, I 736). Archaeologists have attested a striking parallel in the spread to Syria of a distinct pottery type associated with what they call the Kura-Araxes culture." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mitanni-Aryan

With this background of links between Syria/Kassites with Indo-Aryan, it is instructive to find many Indus Script hieroglyphs on Kassite kudurrus.

Examples of Kassite kudurru hypertexts deploying Indus Script hieroglyphs are presented in this monograph.

Scorpion hieroglyph on a kudurru. Indus Script: bicha'scorpion' Rebus: bica 'hematite, sandstone ferrite ore'

Hooded snake on kudurrus. Indus Script: phaṇi 'cobra hood' rebus: phaṇi'lead or zinc'; paṇi'merchant, marketplace'.

Turtle atop a temple on kudurru. Indus Script: kamaṭha 'turtle' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'

- Ram atop temple on a kudurru. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS miṇḍāl 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ'iron' (Munda.Ho.) meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakrtam)

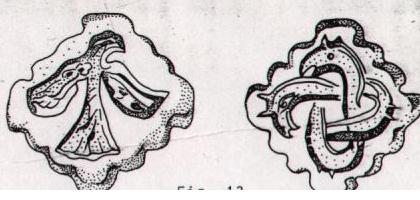

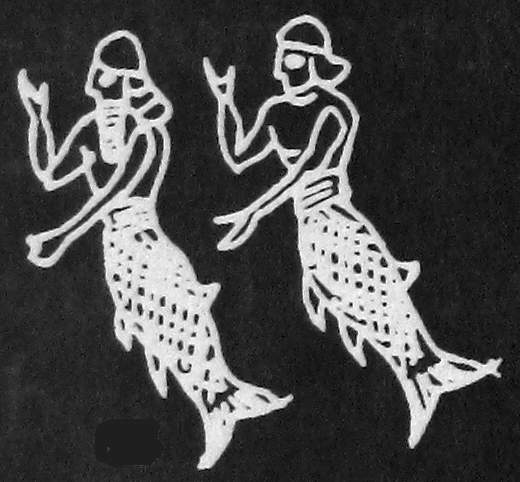

![]() Fish-anthropomorphs. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya'iron'ayas'alloy metal'

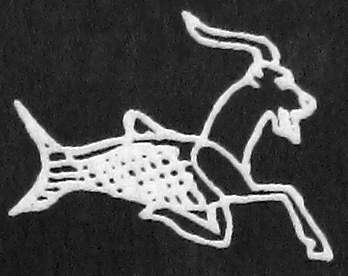

Fish-anthropomorphs. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya'iron'ayas'alloy metal'![]() Goat-fish-fin hypertext. Indus Script: ayo'fish' rebus: aya 'iron'ayas'alloy metal' PLUS khambhaṛā fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa'mint, coiner, coinage' PLUS mr̤eka, melh 'goat' (Telugu. Brahui) Rebus: melukkha 'milakkha, copper'. meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakrtam) The expression signifies a copper-metal (iron) mint, smith/merchant.

Goat-fish-fin hypertext. Indus Script: ayo'fish' rebus: aya 'iron'ayas'alloy metal' PLUS khambhaṛā fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa'mint, coiner, coinage' PLUS mr̤eka, melh 'goat' (Telugu. Brahui) Rebus: melukkha 'milakkha, copper'. meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakrtam) The expression signifies a copper-metal (iron) mint, smith/merchant.

Moonhieroglyph on a kudurru. Indus Script: مر ḳamar A قمر ḳamar, s.m. (9th) The moon. Sing. and Pl. See سپوږمي or سپوګمي (Pashto) rebus: kamar 'artisan, smith' (Santali) Arrow atop a temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l'smithy, forge' PLUS Oriya. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023). ayaskāṇḍa 'a quantity of iron; kāṇḍa 'implements'NOTE: The Indus Script expression kole.l which signifies a temple is significant. Since kole.l is a smithy, forge', the activities related to metalwork gain sacredness and veneration as products realized in a temple. Hence, the Kassite kudurrus equate metalwork hieroglyphs and express veneration of ancestors who were metalworkers with divinities (as signified on the hieroglyphs used on kudurrus). The divinities for Kassites are: (1) Anu, (2) Enlil, (3) Ea, (4) Ninmakh, (5) Sin, (6) Nabu, (7) Gula, (8) Ninib, and (9) Marduk.

Tiger-head atop a temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS kola'tiger' rebus: kol'working in iron'

Rim-of-jar (upside down) atop temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS karṇika, kanka 'rim of jar' Rebus: karṇI 'supercaro, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale'.'

A rod (signifying 'one') atop temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS koḍa'one' rebus: koḍ'workshop'

Sun's rays hieroglyph on kudurrus. Indus Script: arka 'sun' rebus: arka, eraka 'copper'.

Star hieroglyph on kudurru. Indus Script: mēḍhaमेढ 'polar star' (Marathi) rebus: मृदु mṛdu, mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Samskrtam, Santali. Mu.Ho.)

![]() Black drongo atop a pillar on a kudurru. Indus Script: pōlaḍu 'black drongo' signify polad 'steel' PLUS skambha 'pillar' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint', coiner, coinage

Black drongo atop a pillar on a kudurru. Indus Script: pōlaḍu 'black drongo' signify polad 'steel' PLUS skambha 'pillar' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint', coiner, coinage ![]() Duck atop a temple on a kudurru. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS karaṇḍa'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

Duck atop a temple on a kudurru. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS karaṇḍa'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

Tree atop a temple on a kudurru. Indus Script:kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS kuṭhi a sacred, divine tree, kuṭi 'temple'; kuṭhi 'smelter'

Tree and bull on a kudurru. Indus Script: kuṭhi a sacred, divine tree, kuṭi 'temple'; kuṭhi 'smelter' PLUS ḍhaṅgaru, ḍhiṅgaru m. ʻlean emaciated beastʼ(Sindhi) Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili)

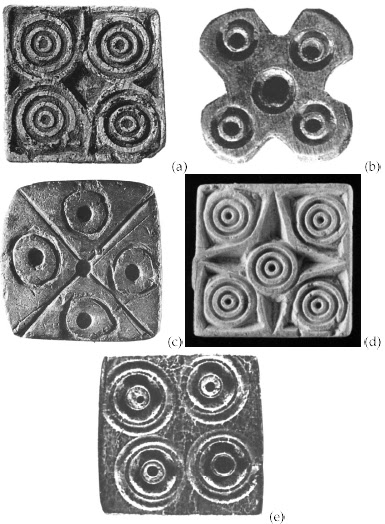

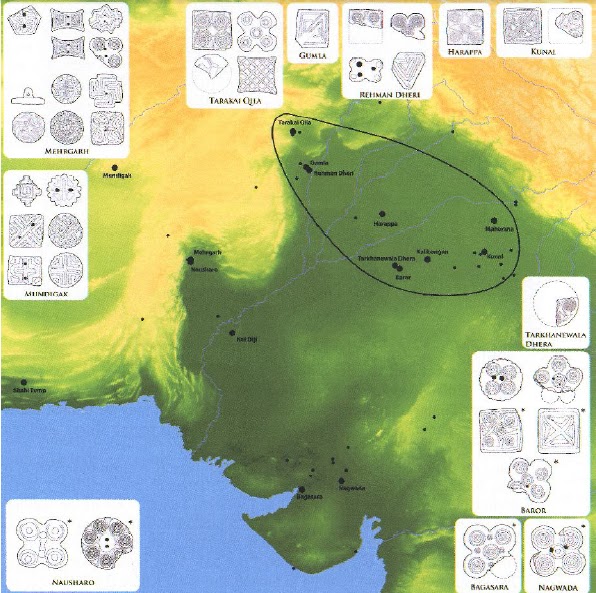

kudurru stones of the Kassite Period (circa 1530-1155/1160 BCE) includes the following hieroglyphs:

Meli-Šipak kudurru, 1186–1172. pr. Kr. Goat-fish

![Image result for Kudurru]() mushhushshu.

mushhushshu.Kudurru fragments. With mushhushshu.

Lion

Furrow

Scorpion-Archer

Hired-Man

Goat-Fish

Limestone kudurru reign of Marduk-nadin-ahhe: the boundary-stone consists of a block of black limestone, which has been shaped and rubbed down to take sculptures and inscriptions. Culture/period: Middle Babylonian Date: 11thC BC From: Babylon (Asia, Middle East, Iraq, South Iraq, Babylon) Materials: limestone Technique: carved British Museum number: 90841

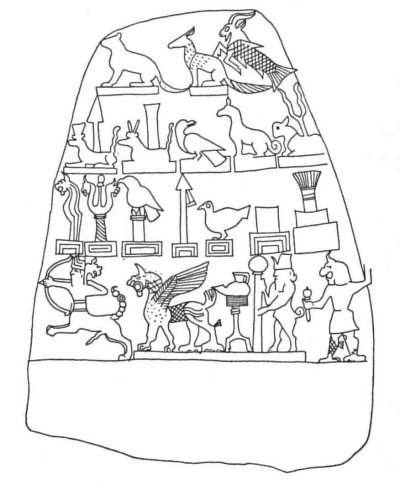

![]() Meli-Shipak kudurru.

Meli-Shipak kudurru."Unfinished" Kudurru Kassite period, attributed to the reign of Melishipak (1186-1172 BC). Susa, Iran (where it had been taken as war booty in the 12th century BC). Limestone.

Limestone boundary-stone (kudurru) from the time of Nabu-mukin-apli

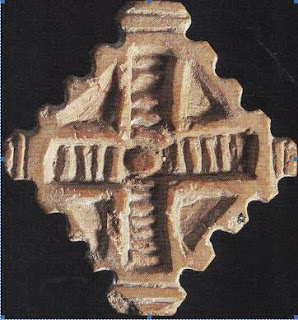

Unfinished kudurru (boundary marker) with a horned serpent (symbol of Marduk) around pillar at bottom. The most proeminent gods are featured as symbols. The space for the inscription was left unused.White limestone Kassites era, found in Susa Found by J. de Morgan. Accession No. Sb25 Louvre Museum. Kudurru "inachevé" Époque kassite, attribué au règne de Meli-Shipak (1186-1172 av. J.-C.) Découvert à Suse où il avait été emporté en butin de guerre au XIIe siècle avant J.-C.

Calcaire

Sous les anneaux du serpent qui s'enroule sur le sommet sont figurées les principales divinités du panthéon sous forme de symboles. Au-dessous, un cortège de dieux musiciens et d'animaux. Murs et tours crénelées encadrent l'emplacement réservé à une inscription qui n'a jamais été gravée. Un serpent cornu, emblème du dieu Marduk, entoure la base. |

|

What are kudurrus? They are stelas or stone (or clay) slabs (called nargus or asumittu, "inscribed slab," and abnu, "stone." by the Babylonians) with inscriptions, generally of land grants, boundary markers.

Ignace Gelb et al detailt the functions of the kudurrus as documents of land tenure systems of the Bronze Age. [Ignace Gelb, Piotr Steinkeller, and Robert Whiting Jr., 1991, Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus by Ignace Gelb, Piotr Steinkeller, and Robert Whiting Junior (1989-1991, 2 Parts: Part 1: Text, Part 2: Plates)].

Giorgio Buccellati details field and/or temple placement of kudurrus. (Giorgio Buccellati, 1994, The Kudurrus as Monuments in: Cinquante-deux reflexions sur le Proche-Orient ancien offertes en hommage a Leon de Meyer, Pages 283-291).

Kathryn Slanski presents an 'administrative' view on the purpose of kudurrus. (Kathryn Slanski, 2000, Classification, Historiography and Monumental Authority: The Babylonian Entitlement Narus (Kudurrus), in: Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Volume 52, 2000, Pages 95-114).

Brinkman provides an economic interpretation that kudurrus were not legal documents - but mere commemoration/markers of the acquisition of land (perpetual income). (John Brinkman, 2006, Babylonian royal land grants, memorials of financial interest, and invocation of the divine, in: Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient [JESHO], Volume 49, 2006, Pages 1-47).

جدار jidar 'wall'; pl. جدور judūr). The kudurrus are the only surviving artworks for the period of Kassite rule in Babylonia with examples kept in the Louvre, the British Museum, and the National Museum of Iraq. he kudurrus recorded the land granted by the king to his vassals as a record of his decision. The original kudurru would be stored in a temple while the person granted the land would be given a clay copy to use as a boundary stone to confirm legal ownership. The kudurrus would contain symbolic images of the deities who were protecting the contract, the contract, and the divine curse that would be placed on a person who broke the contract. Some kudurrus also contained an image of the king who granted the land. As they contained a great deal of images as well as a contract, kudurrus were engraved on large slabs of stone.[unquote] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kudurru

http://members.westnet.com.au/gary-david-thompson/index1.html This is a remarkable website with many details about kudurrus and annotated bibliographies. Gary D. Thompson who is the author of the website notes: "Some 15 Sumerian kudurrus dating to the Uruk III period (circa 3100-2900 BCE) and Early Dynastic II-III period (circa 2900-2600 BCE) are known. Early kudurrus have been recovered from Sumerian locations that include Lagash, Nippur, Adab, and Ur. All these locations were subject to Semitic influence.

![]()

Source: Aspects of the early history of the Kassites and the archaeology of the Kassite Period in Iraq (c. 1600-1150 BC) by Tim Clayden (1989 (Volume 1, Pages 157-158), 2 Volumes; Unpublished PhD Thesis; Wolfson College, Oxford).

"Daniel potts makes the point that: divine symbols also appear in oaths and legal texts where, in taking the oath, the oath-taker swears by the symbol of a particular god/goddess. One example given is the depiction on the stele of vultures. (source: mesopotamian civilization: the material foundations by daniel potts (1997, page 193).) The stele known as the stele of the vultures is a monument from the early dynastic iii period (2600–2350 bce) in mesopotamia. It was erected in 2450 bce by this king of the city-state of lagash to commemorate his victory over the city of umma. The stele was originally carved out of a single slab of limestone but only seven fragments are known today. The fragments were found at tello (ancient girsu) in southern iraq in the late 19th-century and are now on display in the louvre." http://members.westnet.com.au/gary-david-thompson/page11-6.html ![]()

"Source: Aspects of the early history of the Kassites and the archaeology of the Kassite Period in Iraq (c. 1600-1150 BC) by Tim Clayden (1989 (Volume 1, Pages 167-168), 2 Volumes; Unpublished PhD Thesis; Wolfson College, Oxford). The goddess Išhara is identified with label on a kudurru recovered from Susa. Regarding Sb 31: No 64; Sb is the prefix number from the French excavations at Susa.

The scorpion was a common symbol during the First Dynasty of Babylon and also the Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian, and Seleucid periods. The scorpion symbol appeared on cylinder seals and also has been found carved on a stone bowl dated to the reign of King Rimus of Akkad (circa 2200 BCE).

According to F. Wiggerman, Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts (1992, Page 180), the appearance of the scorpion-man dates at least to the 3rd-millennium BCE, and is associated with the sun-god. (There are several traditions of scorpion men.) A scorpion-man could be depicted as an archer in a number of hybrid (composite) combinations. The picture of a scorpion is very common on kudurrus and there sometimes occurs a what is termed a "scorpion-archer." (The later constellation Sagittarius = a centaur with bow and arrow.) There are several different depictions of a centaur archer on kudurru. A strange hybrid (composite) creature as archer appears on a kudurru (BM 80858) alongside the goddess Gula and her dog. It comprises a half man (human head and arms holding a stretched bow, a scorpion's body and tail, and bird's feet. The representation of a 2-headed centaur archer that is a half-man, half horse with wings, and 2 tails - one a scorpion tail - is both early and late. It appears at the top of a Kassite dynasty kudurru in the British Museum and also appears on a Hellenistic/Seleucid period stamp seal. The late stamp seal image is interpreted as a depiction of the zodiacal constellation Sagittarius. All of the signs of the zodiac can be recognised on stamp seal designs of the Hellenistic period. (See: Catalogue of Western Asiatic Seals in the British Museum by Terence Mitchell and Ann Searight (2008 Page 218, and also see Pages 238-239).) For a recent study of Babylonian composite figures see: Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art by Constance Gane (unpublished PhD thesis, 2012)."

![]()

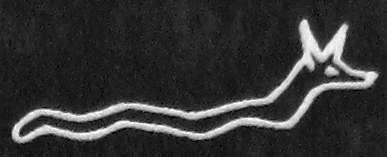

"Kudurru of King Marduk-zakir-shumi (854-819 BCE) with interesting iconography (including a fox). Underneath the serpent do we have the scorpion constellation and the Pleiades or Išhara and her 7 children the Sebetti/Sibitti (the 7 benevolent demon gods)? Peter van der Veen (2008) has pointed out the '7 dots' (commonly symbolising the Pleiades) do not appear on Kassite kudurrus, but only on post-Kassite Babylonian kudurrus from year 8 of Nabu-shuma-ishkun (circa 760-746 BCE) and Shamash-shum-ukin (667-648 BCE). The 7 dots (2 horizontal rows of 3 plus 1 to the right) are an Assyrian convention of rendering the sibitti. Only later were the 7 sibitti/sebittu associated with the Pleiades." http://members.westnet.com.au/gary-david-thompson/page11-6.html ![]()

![]()

"Several views of VA 3031 dating to reign of Nabu-shuma-ishkun (circa 760-746 BCE). VA 3031 (VAS 1 36/VS 1, 36) from Borsippa is tablet shaped. The 7 dots (2 horizontal rows of 3 plus 1 to the right) are in this post-Kassite period associated with the Pleiades. (Peter van der Veen (2008) has pointed out the '7 dots' (commonly symbolising the Pleiades) do not appear on Kassite kudurrus, but only on kudurrus from year 8 of Nabu-shuma-ishkun (circa 760-746 BCE) and Shamash-shum-ukin (667-648 BCE)." http://members.westnet.com.au/gary-david-thompson/page11-6.html

![Boundary stone (kudurru)]() Kassite dynasty, about 1186-1172 BC

Kassite dynasty, about 1186-1172 BC

From Sippar, southern Iraq

The gift of farmland to a senior Babylonian official

The cuneiform text records an extensive royal gift of farmland (50 gur) by Meli-Shipak (reigned 1186-1172 BC), a king of the Kassite dynasty ruling Babylonia, to Khasardu, the son of Sume. The land was situated on the bank of the Royal Canal. The deed was drawn up in the presence of seven high officials who are listed in the cuneiform inscription by name. The stone is given its own name in the text as: 'O Adad [the storm god], mighty lord, bestow abundant streams'. As is typical with documents of this type, the text ends with curses against anyone who ignores the legal contents or damages the stone. The columns of writing are presented as if on the walls of a fortress. Further protection is given by thirteen gods who are invoked to guard the document. In addition, eighteen divine symbols are carved on the upper part of the kudurru. These include a figure with twisting legs and a two-headed, two-tailed winged centaur, a precursor of Sagittarius, drawing a bow.

Is scorpion a constellation symbol?

"Kudurru, (Akkadian: “frontier,” or “boundary”), type of boundary stone used by the Kassites of ancient Mesopotamia. A stone block or slab, it served as a record of a grant of land made by the king to a favoured person. The original kudurrus were kept in temples, while clay copies were landowners. On the stone were engraved the clauses of the contract, the images or symbols of the gods under whose protection the gift was placed, and the curse on those who violated the rights conferred. The kudurrus are important not only for economic and religious reasons but also as almost the only works of art surviving from the period of Kassite rule in Babylonia (c. 16th–c. 12th century bc)." https://www.britannica.com/topic/kudurruDivin "Some kudurrus are known for their portrayal of the king, etc., who consigned it. Most kudurrus portray Mesopotamian gods, which are often portrayed graphically in segmented registers on the stone. Nazimaruttash's kudurru does not use registers. Instead, graphic symbols are used. Nineteen deities are invoked to curse the foolhardy individual who seeks to desecrate it. Some are represented by symbols, such as a goat-fish for Enki or a bird on a pole for Papsukkal, a spear-head for Marduk or an eight-pointed star for Ishtar. Shamash is represented by a disc." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazimarutta%C5%A1_kudurru_stone

Bible: Proverbs 22:28 “Do not move an ancient boundary stone set up by your forefathers.”

Kudurru de Melishipak

The kudurru of Melishihu (1186-1172 BCE). Register V has 3 symbols including a snake and a scorpion.

![Related image]()

![Kudurru of Melishihu. Louvre, Paris]() Kudurru of Mellishihu.Louvre.

Kudurru of Mellishihu.Louvre.

Kudurru of Melishihu. Louvre, Paris. Boundary markers for property are a very old concept. They are mentioned in the Bible: Proverbs 22:28 “Do not move an ancient boundary stone set up by your forefathers.”

![Pantheon of Kassite Gods. Melishipak kudurru-Land grant to Marduk-apla-iddina]()

The stone shown above is even older, it is a Kudurru, a small stone stele recording a royal gift of land, from ancient Babylonia, and the concept is exactly the same as a boundary stone. The word is Akkadian for “frontier” or “boundary”. This kudurru is from the reign of King Melišipak (1186–1172 BC) at the Louvre. It records a land grant to his son, Adad-šuma-u?ur or Meliši?u. Meli means servant or slave, Šipak was a moon god, but Ši?u was possibly one of the Kassite names for Marduk, patron God of Babylon. On the front of the stele is represented the entire pantheon of gods who preserve the order of the world. The artist has used a formula that was later to be developed on other kudurrus, presenting the symbols associated with each deity in hierarchical rows. On the reverse side is cuneiform writing describing the gift and the responsibilities to the king as a result of the gift. This is followed by a section calling down a divine curse on anyone who opposed the gift. The gift was thus not only recorded and displayed for all to see, but also placed under divine protection. Because stone was precious in Babylon, the original was kept in a temple and clay replicas were placed on the land.

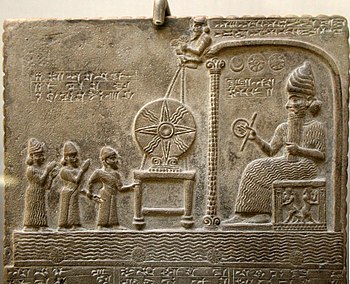

Melišipak kudurru-Land grant to Hunnubat-Nannaya. Louvre, Paris

In the kudurru pictured above King Melišipak, with his hand over his mouth as a sign of respect, is shown presenting his daughter to the goddess Nannaya. As noted above, the crescent moon représents the god Sîn, the sun representing the god Shamash and the star (Venus) representing the goddess Ishtar. His daughter ?unnubat-Nana(ja) was the recipient of a land grant, which her father had purchased on her behalf, disproving a theory of Kassite feudalism that all land belonged to the Monarch. With the exception of the relief shown above, there are no further inscriptions. The surface is hammered, suggesting the original inscriptions have been removed, perhaps by the Elam King Shutruk-Nakhunte.

![]() Melli-shipak Kudurru

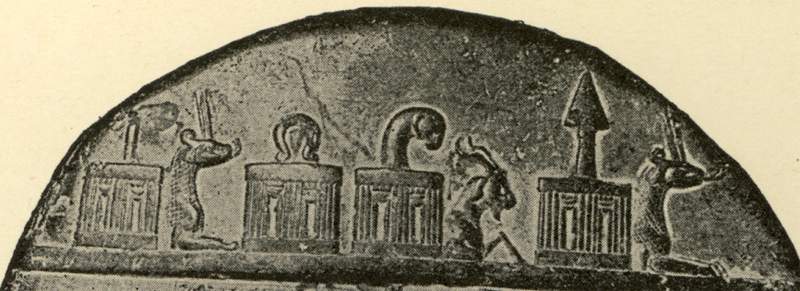

Melli-shipak KudurruUnfinished Kudurru from the Reign of Melishipak, found in Sousa. Louvre, Paris

Unfinished Kudurru from the Reign of Melishipak, found in Sousa. Louvre, Paris

The kudurru pictured above is unfinished, without text. You can see some of the same now familiar symbols at the top. In the top row, the crowns with six rows of horns placed on the altars are the emblems of Anu, the sky god, and Enlil, the air god. To the left, the ram's head and the goatfish representing Ea, the god of fresh water, and Ninhursag, the earth goddess. To the right, the sun of Shamash and the star (Venus) of Ishtar. At the bottom you can see the scales of the Chtonian underworld snake winding around the stone and in the picture to the right, you can see the head and tail. Also on this view you can see three symbols on the third row, the plow of Ningirsu followed by the birds of Shuqamuna and Shumalia, the divine couple of the Kassite pantheon. At the top is Marduk, represented by a horned dragon, Adad, shown with a storm on an alter and Nabu, Marduk's son and the god of scribes, represented by a tablet and calamus. The middle row is very unusual. It depicts a procession of eight figures, all carrying bows and wearing the horned crowns that mark them out as gods, probably minor deities. Seven of the figures are bearded gods, playing the lute and accompanied by animals. A goddess playing the tambourine and possibly dancing follows them. These emblems were difficult to interpret, even for the ancients who sometimes inscribed the name of the gods symbolized next to the symbols themselves.

Babylonia at the Time of the Kassites

These kudurrus are important because they are the only surviving artworks for the period of Kassite rule in Babylonia. They were found in Susa, capital city of ancient Elam. They were taken when the Elam King Shutruk-Nakhunte, who had married the eldest daughter of King Melišipak, sacked Babylon and took them back to Elam as spoils of war. Cruel and fierce, the Elamites finally destroyed the dynasty of the Kassites during these wars (about 1155), often lamented by the poets of Babylon.

The Kassites first appeared during the reign of Samsu-iluna (1749–1712 BC), son of Hammurabi (see my post on the Code of Hamarabi) of the First Babylonian Dynasty and after being defeated by Babylon, moved to control the city-state of Mari. Babylon was invaded and captured by the Hittite king Mursilis in about 1595 BC, but he mysteriously soon left Babylon and returned to Hattusas. The Kassite ruler, Agum II, filled this power void establishing the Kassite dynasty in Mesopotamia that was to last until about 1157 BC. Some undetermined amount of time after the fall of Babylon to, the Kassites established a new Babylonian dynasty. The Hittites had carried off the idol of the god Marduk, but the Kassite rulers regained possession, returned Marduk to Babylon, and made him the equal of the Kassite Shuqamuna. They went on to to conquer the southern part of Mesopotamia, roughly corresponding to ancient Sumer and known as the Dynasty of the Sealand by 1460 BC. The Kassites restored the ancient temples of Nippur, Larsa, Ur, and Uruk, while their scholars were preserving the literature in Akkadian, the standard language of the Near East for a millennium. Much of what we know about the Kassites comes from tablets found in Nippur. A new capital west of Baghdad, Dur Kurigalzu, competing with Babylon, was founded and named after Kurigalzu I (c. 1400-c. 1375). The Kassites rapidly adopted the Babylonian language, customs, and traditions. They introduced the use of small stone steles known as kudurrus, a tradition maintained by later dynasties until the 7th century BC. Surprisingly no inscription or document in the Kassite language has been preserved. Kassite kings established trade and diplomacy with Assyria, Egypt, Elam, and the Hittites, and the Kassite royal house intermarried with their royal families. There were foreign merchants in Babylon and other cities, and Babylonian merchants were active from Egypt (a major source of Nubian gold) to Assyria and Anatolia. But the catastrophic collapse at the end of the bronze age was starting to dramatically unfold with many of the cities of the Levant experiencing destruction. During the reign of Kashtiliash IV (1232-1225), Babylonia waged war on two fronts at the same time, against Elam and Assyria, ending in the invasion and destruction of Babylon by Tukulti-Ninurta of Assyria (Chronicle of Tukulti-Ninurta I) perhaps around 1225 BC. The situation had improved by the time of King Melišipak, but during his reign Emar in Syria (Mitanni, an ally of Egypt) was sacked in 1187 BC and and the Hittite capital of Hattusa was burnt to the ground sometime around 1180 BC.

Between 1206 and 1150 BCE, the cultural collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms, the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and Syria, and the New Kingdom of Egypt in Syria and Canaan interrupted trade routes and severely reduced literacy. From Greece to Egypt, the social and political system of the Bronze Age collapsed. Amid war and chaos, the great palaces of the ancient Greek kings and the strong fortress of Troy were destroyed. Hittite rule in Asia Minor was ended forever, and the Hittites disappeared from history. The cities of Cyprus and Syria (Mitanni) were destroyed. A mysterious group, the Sea Peoples were a confederacy of seafaring raiders of the second millennium BC who sailed around the eastern Mediterranean, causing political unrest, and attempted to enter or control Egyptian territory. Egypt fought against them for its very existence. The battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC was the first contact of Egypt with the Sea Peoples. Subsequently Ramesses III, the second king of the Egyptian 20th Dynasty, who reigned for most of the first half of the 12th century BC, was forced to deal with a later wave of invasions of the Sea Peoples, and by the way won. Ramses tells us that, having brought the imprisoned Sea Peoples to Egypt, he “settled them in strongholds, bound in my name. Some scholars suggest it is likely that these “strongholds” were fortified towns in southern Canaan, which would eventually become the five cities (the Pentapolis) of the Philistines.

These were not typical invasions but rather a mass migration from places unknown. The invaders, that is, the replacement cultures, apparently made no attempt to retain the cities' wealth but instead built new settlements of a materially simpler cultural and less complex economic level on top of the ruins, particularly in Canaan. The fact that several civilizations around 1175 BCE collapsed has led suggestion that the Sea Peoples may have been involved in the end of the Hittite, Mycenaean and Mitanni kingdoms.

Many, but not all, of the Canaanite cities were destroyed, international trade collapsed, and the Egyptians withdrew. At the end of this period a new landscape emerges: the northern Canaanite cities still existed, more or less intact, and became the Phoenicians; the highlands behind the coastal plains, previously largely uninhabited, were rapidly filling with villages, largely Canaanite in their basic culture but without the Bronze Age city-state structure; and along the southern coastal plain there are clear signs that a non-Canaanite people had taken over the former Canaanite cities while adopting almost all aspects of Canaanite culture, the Philistines and the Jewish states of Judah and Israel. The Arameans never had a unified nation; they were divided into small independent kingdoms across parts of the Near East, particularly in what is now modern Syria. By contrast, the Aramaic language came to be the lingua franca of the entire Fertile Crescent, by Late Antiquity developing into the literary languages such as Syriac and Mandaic (see my post on the Syriac Church). Arameans are mostly defined by their use of the West Semitic Old Aramaic language (1100 BC–AD 200), first written using the Phoenician alphabet, over time modified to a specifically Aramaic alphabet. The 2nd and 3rd centuries were the golden age of Palmyra, home to the Arameans, when it flourished through its extensive trading and favored status under the Romans.

https://traveltoeat.com/babylonian-kudurru-at-the-louvre-2/![File:Kudurru of Adad-etir BM ME 90834.jpg]() Commemorative stone stela (kudurru) set up in honour of Adad-etir, an official of the Marduk Temple, by his son Marduk-balassu-iqbi. From the Temple of Marduk in Babylon. Granite. from 900 until 800 BCE Length: 38 cm (15 in). Width: 27 cm (10.6 in). Thickness: 12.7 cm (5 in). British Museum.. Accession No. ME 90834

Commemorative stone stela (kudurru) set up in honour of Adad-etir, an official of the Marduk Temple, by his son Marduk-balassu-iqbi. From the Temple of Marduk in Babylon. Granite. from 900 until 800 BCE Length: 38 cm (15 in). Width: 27 cm (10.6 in). Thickness: 12.7 cm (5 in). British Museum.. Accession No. ME 90834The British Museum dates this kudurru to 1125-1100 BC:

![]() Walters Art Museum no. 2110 kudurru A "kudurru," the Akkadian term for boundary stone, combines images of the king, gods, and divine symbols with a text recording royal grants of land and tax exemption to an individual. While the original was housed in the temple, a copy of the document was kept at the site of the land in question. This example was found at the temple of Esagila, the primary sanctuary of the god Marduk. The king Marduk-nadin-ahe is depicted with his left hand raised in front of his face; he wears the tall Babylonian feathered crown and an elaborately decorated garment with a honeycomb pattern. On the top are a sun disk, star, crescent moon, and scorpion, representing deities who witnessed the land grant and tax exemption. A snake-dragon deity emerges from a row of altars shaped like temple façades along the back.

Walters Art Museum no. 2110 kudurru A "kudurru," the Akkadian term for boundary stone, combines images of the king, gods, and divine symbols with a text recording royal grants of land and tax exemption to an individual. While the original was housed in the temple, a copy of the document was kept at the site of the land in question. This example was found at the temple of Esagila, the primary sanctuary of the god Marduk. The king Marduk-nadin-ahe is depicted with his left hand raised in front of his face; he wears the tall Babylonian feathered crown and an elaborately decorated garment with a honeycomb pattern. On the top are a sun disk, star, crescent moon, and scorpion, representing deities who witnessed the land grant and tax exemption. A snake-dragon deity emerges from a row of altars shaped like temple façades along the back.![Tablet of Shamash relief.jpg]() Tablet of Shamash |

| Material | Limestone |

|---|

| Size | Length: 29.2 cm, Width: 17.8 cm |

|---|

| Created | 888-855 BC |

|---|

| Present location | British Museum, London. Room 55. |

|---|

| Registration | ME 91000 |

|---|

![AO 6684 deed of gift of Marduk-zākir-šumi.jpg]() Kudurru recording the bequest of land by Marduk-zâkir-šumi to Ibni-Ištar on behalf of the Eanna temple in Uruk [i 1] |

| Reign | c. 855 – 819 BC |

|---|

![]() Merodach-Baladan, King of Babylon, enfeoffs(makes a legal agreement with) a vassal. From the original in the Altes Museum, Berlin. Marduk-apla-iddina II (cuneiform spelling ᴰMES.A.SUM-na; in the Bible Merodach-Baladan, also called Marduk-Baladan, Baladan and Berodach-Baladan, lit. Marduk has given me an heir) was a Chaldean prince who usurped the Babylonian throne in 721 BC and reigned in 722 BC--710 BC, and 703 BC--702 BC.

Merodach-Baladan, King of Babylon, enfeoffs(makes a legal agreement with) a vassal. From the original in the Altes Museum, Berlin. Marduk-apla-iddina II (cuneiform spelling ᴰMES.A.SUM-na; in the Bible Merodach-Baladan, also called Marduk-Baladan, Baladan and Berodach-Baladan, lit. Marduk has given me an heir) was a Chaldean prince who usurped the Babylonian throne in 721 BC and reigned in 722 BC--710 BC, and 703 BC--702 BC.

"The kudurrus (in Akkadian "limit") were stelae to verify the donation of lands for the benefit of a community or important personage.

They delimitd properties granted by the king of Babylon. These are legal documents with the names and positions of the

magistrates and the king, the owners and their offices. They are protected by the gods engraved on them." -- Dra. Ana Ma Vazquez Hoys

| | | | | | | 1.A boundary stone recording a royal gift of land.I I Dinastía de Isin, h, 1099-1082 a.C. De Babilonia, sur Iraq. Museo Británico ANE 90840 | 2. The Establisher the Boundary forever.I I Dinastía de Isin, h, 1099-1082

De Babilonia, sur Iraq. Museo Británico ANE 90841 | 3.A legal statement about the ownership of a piece of land.Museo Británico, ANE 102485 | 4.A legal statement about the ownership of a piece of land.Museo Británico, ANE 108835 | | | | | | 5.Dinastía kasita , h. 1186-1172 a.C. De Sippar, sur Iraq, Museo Británico, ANE 90829 | 6.Babilonia, h. 1125-1104 a.C. De Sippar, sur Iraq. Museo Británico ANE 90858, | 7. Babilonia, h.978-943 BC

De Sippar, sur Iraq.A legal statement about the ownership of some land.Museo Británico ANE 90835 | 8.Kudurru de Melishipak.Museo del Louvre |

|

|

![]() Die Babylonischen Kudurru-Reliefs p.21

Die Babylonischen Kudurru-Reliefs p.21

See: http://cmaa-museum.org/kudurru.pdf

Excerpted from: http://benedante.blogspot.in/2015/10/in-name-of-mesopotamian-gods.html

In the Name of the Mesopotamian Gods

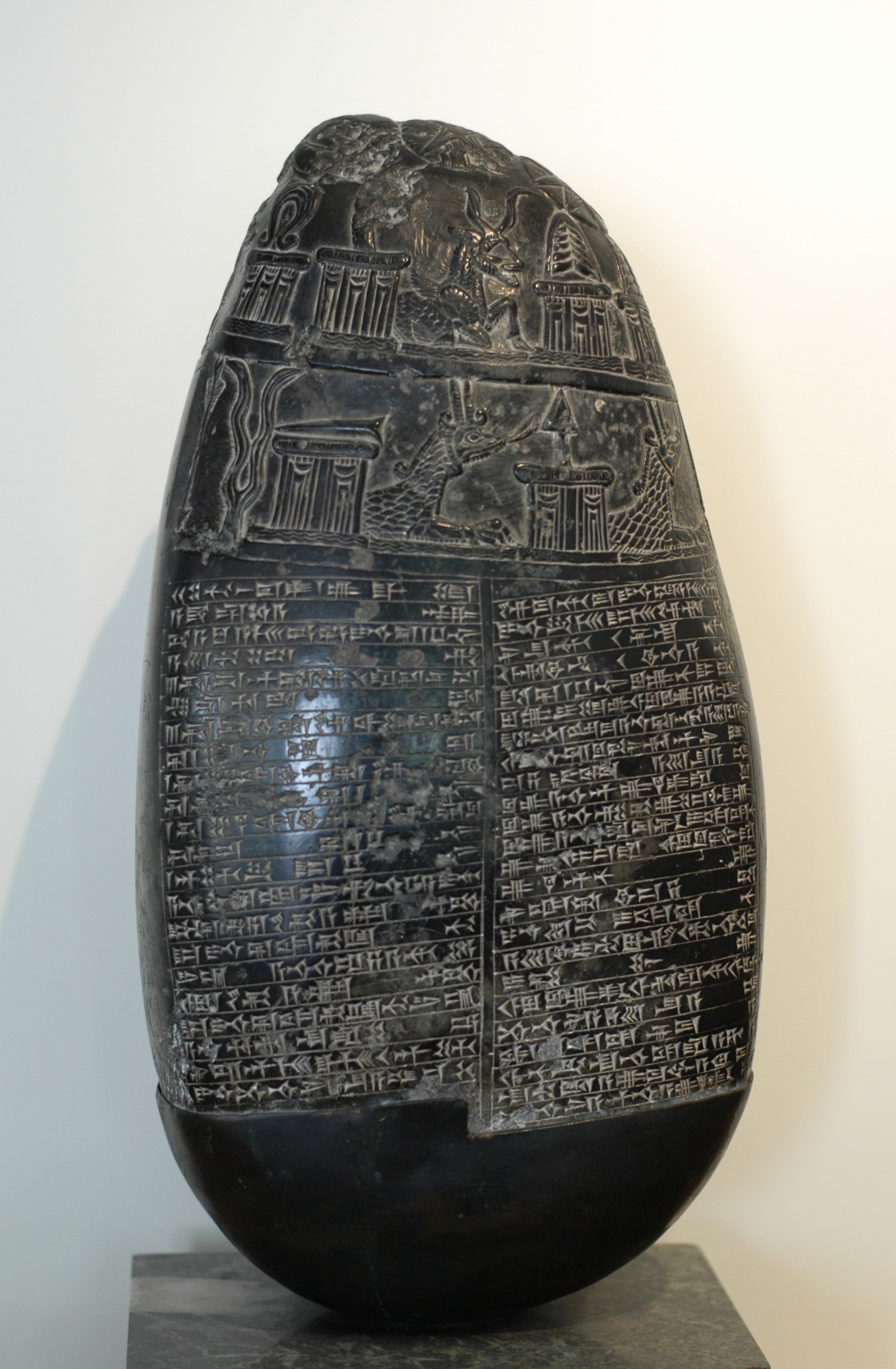

This magnificent object is a Kudurru, a carved stone used to mark a royal land grant. Old books call them "boundary stones", but they were kept in the palace or temple archives, not placed out on the borders of the grant. This one comes from Babylon, the Second Dynasty of Isin, 1157-1025 BC; I found it in an online exhibit at the California Museum of Ancient Art.

This stone is carved of black limestone, 16.5 inches tall (42 cm). The designs are full of significance. On the front:the Mesopotamian pantheon is presented. The four great gods come first. Anu ("father of the gods" and god of heaven) and Enlil (god of wind, kingship and the earth), are shown as a multi-horned divine crown each on its own temple facade. Then Ea (god of water, magic and wisdom), is shown as a curved stick ending in a ram's head atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a horned goat. Above the first two deities, a female headdress in the shape of an omega sign, symbolizes Ninhursag ("mother of the gods" and goddess of fertility).

Reverse:The leading Babylonian god, Marduk, and his son Nabu, appear next. A triangular spade pointing up and a scribe's wedge-shaped stylus, respectively, each sits atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a snake-dragon known as a Mushus. All five temple facades float on fresh, underground waters known as the Apsu or the Deep. Following these divinities, we find the mace, perhaps a local war god, the scepter with double lion heads of Ninurta (god of war), the arrow, a symbol of the star Sirius, and the two-pronged lightning bolt of Adad. This storm god is called by the similar name Haddad in the Levant. The running bird Papsukkal (minister of the gods, associated with the constellation Orion), is followed by the scorpion Ishara (goddess of oaths), the seated dog Gula (goddess of healing) and a bird on a perch, symbolizing both Shuqamuna and Shumalia (patron deities of the Kassite royal family).

Top:The top of the kudurru, representing the heavens, is surrounded and enclosed by the body of a large snake. Nirah (the snake god) encompasses four astral deities the crescent moon of Sin (the moon god), a multi-rayed circular sun disc of Shamash (the sun god), a star inside a disc for Ishtar (the goddess of love -especially sexuality- and war) and the lamp of Nusku (the god of fire and light). Ishtar, considered the most important Mesopotamian female deity, is associated with the morning and evening star, the planet Venus.

http://cmaa-museum.org/meso01.html The website of the California Museum of Ancient Art includes the following excerpted document introducing kudurrus:http://cmaa-museum.org/kudurru.pdf![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A Gathering of the Gods - the Power of Mesopotamian Religion

Article on Kudurru(1.12MB)

Mesopotamian Black Limestone Kudurru

Mesopotamia; Second Dynasty of Isin, 1157-1025 BC; Height 16.5 inchesThe upper section of this finely polished black limestone kudurru is decorated in intricately carved raised relief with symbols and sacred animals representing a large group or "gathering" of Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. Kudurrus, sometimes referred to as "boundary markers," were actually land grant documents used by kings to reward their favored servants. These monuments were set up in temples to record royal land grants. The full force of the Mesopotamian pantheon was utilized both to witness and guarantee the land grant by carving the symbols and sacred animals of the deities on the kudurru. In the shape of a cylindrical ovoid, this particular kudurru was not inscribed, perhaps because the person who was to receive the land grant died before it could be finalized, or because the king changed his mind and decided not to make the land grant after all. Each kudurru is unique; a good deal of variation exists in the number and choice of deities which appear.

Front:On this standing monument, the Mesopotamian pantheon is presented. The four great gods come first. Anu ("father of the gods" and god of heaven) and Enlil (god of wind, kingship and the earth), are shown as a multi-horned divine crown each on its own temple facade. Then Ea (god of water, magic and wisdom), is shown as a curved stick ending in a ram's head atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a horned goat. Above the first two deities, a female headdress in the shape of an omega sign, symbolizes Ninhursag ("mother of the gods" and goddess of fertility).

Reverse:The leading Babylonian god, Marduk, and his son Nabu, appear next. A triangular spade pointing up and a scribe's wedge-shaped stylus, respectively, each sits atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a snake-dragon known as a Mushus. All five temple facades float on fresh, underground waters known as the Apsu or the Deep. Following these divinities, we find the mace, perhaps a local war god, the scepter with double lion heads of Ninurta (god of war), the arrow, a symbol of the star Sirius, and the two-pronged lightning bolt of Adad. This storm god is called by the similar name Haddad in the Levant. The running bird Papsukkal (minister of the gods, associated with the constellation Orion), is followed by the scorpion Ishara (goddess of oaths), the seated dog Gula (goddess of healing) and a bird on a perch, symbolizing both Shuqamuna and Shumalia (patron deities of the Kassite royal family).

Top:The top of the kudurru, representing the heavens, is surrounded and enclosed by the body of a large snake. Nirah (the snake god) encompasses four astral deities the crescent moon of Sin (the moon god), a multi-rayed circular sun disc of Shamash (the sun god), a star inside a disc for Ishtar (the goddess of love -especially sexuality- and war) and the lamp of Nusku (the god of fire and light). Ishtar, considered the most important Mesopotamian female deity, is associated with the morning and evening star, the planet Venus.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Kudurru, grant deed by Neubchadnezzar I (1125-1104 BCE), Sippar. "This kudurru is of the time of Nebuchadnezzar I (1124-1103 a.C.). At the top, the astral symbols of Sin, Ishtar and Shamash, in the next row, the three tiaras of the gods Anu, Enlil and Ea. Below, Marduk, Nabu and Ninhursag. Then Zababa, Nergal, a warrior god and Shuqamuna and Shumalia. Below is the goddess Ninmah next to a scorpion-man (guardian of the underworld). In the last row is Adad, Nusku, the scorpion of the goddess of the conjugal bed Ishkhara and a turtle, another representation of Ea. In the upper left corner, there is also a serpent, probably representing Ningishzidda god of the underworld." http://www2.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antigua-universal/MESOPOTAMIA/kudurru9.htm

Kudurru, grant deed by Neubchadnezzar I (1125-1104 BCE), Sippar. "This kudurru is of the time of Nebuchadnezzar I (1124-1103 a.C.). At the top, the astral symbols of Sin, Ishtar and Shamash, in the next row, the three tiaras of the gods Anu, Enlil and Ea. Below, Marduk, Nabu and Ninhursag. Then Zababa, Nergal, a warrior god and Shuqamuna and Shumalia. Below is the goddess Ninmah next to a scorpion-man (guardian of the underworld). In the last row is Adad, Nusku, the scorpion of the goddess of the conjugal bed Ishkhara and a turtle, another representation of Ea. In the upper left corner, there is also a serpent, probably representing Ningishzidda god of the underworld." http://www2.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antigua-universal/MESOPOTAMIA/kudurru9.htm ![]() Boundary stone called a kudurru Nebuchadnezzar I, ( U of Penn Museum; Heidel,

Boundary stone called a kudurru Nebuchadnezzar I, ( U of Penn Museum; Heidel,

![]()

Kudurru of Gula The Kudurru of Gula is a boundary stone (Kudurru) for the Babylonian goddess Gula. Gula is the goddess of healing. It is from the 14th century - 13th century BC Kassite Babylonia, and is located at the Louvre.

The Kudurru of Gula shows Gula seated on her chair with her dog adjacent. Another side of the kudurru has registers representing symbols of gods, and also sections of cuneiform text. ![File:Kudurru of Gula-Eresh.jpg]() Kudurru of Gula-Eresh, Goddess of Medicine, Kassite dynasty, Babylon " Sin, Ishtar and Shamash, Anu and Enlil's tiaras, Ninhursag's uterus, Ea's turtle and Marduk's hoe. Around it is a snake that surrounds the scene from the left. In the bottom row is Ninurta's mace, Gula's dog, Ishkhara's scorpion, and Nabu's wall." http://www2.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antigua-universal/MESOPOTAMIA/kudurru10.htm

Kudurru of Gula-Eresh, Goddess of Medicine, Kassite dynasty, Babylon " Sin, Ishtar and Shamash, Anu and Enlil's tiaras, Ninhursag's uterus, Ea's turtle and Marduk's hoe. Around it is a snake that surrounds the scene from the left. In the bottom row is Ninurta's mace, Gula's dog, Ishkhara's scorpion, and Nabu's wall." http://www2.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antigua-universal/MESOPOTAMIA/kudurru10.htm

The Enlil-bānī land grant kudurru is an ancient Mesopotamian narû ša ḫaṣbi, or clay stele, recording the confirmation of a beneficial grant of land by Kassite king Kadašman-Enlil I (ca. 1374–1360 BC) or Kadašman-Enlil II (1263-1255 BC) to one of his officials. It is actually a terra-cotta cone, extant with a duplicate, the orientation of whose inscription, perpendicular to the direction of the cone, in two columns and with the top facing the point, indicates it was to be erected upright, (on its now eroded base), like other entitlement documents of the period.

The kudurru of Kaštiliašu' is a fragment of an ancient Mesopotamian narû, or entitlement stele, recording the legal action taken by Kassiteking Kaštiliašu IV (ca. 1232–1225 BC) over land originally granted by his forebear Kurigalzu II (ca. 1332–1308 BC),[1] son of Burna-Buriaš II to Uzub-Šiḫu or -Šipak in grateful recognition of his efforts in the war against Assyria under its king, Enlil-nirari. Along with the Tablet of Akaptaḫa, these are the only extant kudurrus from this king’s short eight-year reign and were both recovered from Elamite Susa, where they had been taken in antiquity, during the French excavations under Jacques de Morgan at the end of the nineteenth century and now reside in the Musée du Louvre.

The tablet of Akaptaḫa, or Agaptaḫa, is an ancient Mesopotamian private commemorative inscription on stone of the donation of a 10 GURfield (about 200 acres)[1] by Kassite king Kaštiliašu IV (ca. 1232 BC – 1225 BC) to a fugitive leatherworker from Assyrian-occupied Ḫanigalbat in grateful recognition of his services provisioning the Babylonian army with bridles (pagumu, a loanword from Hurrian or perhaps Kassite) .

The Land grant to Ḫunnubat-Nanaya kudurru is an ancient Mesopotamian entitlement narû recording the gift of forty GUR (around a thousand acres) of uncultivated land and control over three settlements by Kassite king Meli-Šipak to his daughter and the provision of exemptions from service and taxation to villages in the region guaranteed with a sealed tablet given to her, presumably to make the land transfer more palatable to the local population. It was excavated by a French archaeological team under the auspices of Jacques de Morgan at the turn of the twentieth century at Susa where it (excavation reference Sb 23) was found with a duplicate (reference Sb 24). It had been taken as booty by Elamite king Šutruk-Naḫḫunte after his 1158 BC campaign that brought about the demise of the regime of Babylonian king Zababa-šuma-iddina, the penultimate monarch of the Kassite dynasty. It is significant in that it shows the king making a second bequest with land he purchased to provide for his beneficiary, contradicting the earlier view of Kassite feudalism, where all land belonged to the monarch.

The Land grant to Marduk-apla-iddina kudurru is a grey limestone 0.7-meter tall ancient Mesopotamian narû or entitlement stele recording the gift of four tracts of cultivated land with settlements totaling 84 GUR 160 qa by Kassite king of Babylon, Meli-Šipak (ca. 1186–1172 BC ), to a person described as his servant (arassu irīm: “he granted his servant”) named Marduk-apla-iddina, who may be his son and/or successor or alternatively another homonymous individual. The large size of the grant together with the generous freedom from all territorial obligations (taxation, corvée, draft, foraging) has led historians to assume he was the prince. There are thirty six kudurrus which are placed on the basis of art-history to Meli-Šipak's reign, of which eight are specifically identified by his name.

The estate of Takil-ana-ilīšu kudurru is an ancient Mesopotamian white limestone narû, or entitlement stela, dating from the latter part of the Kassite era which gives a history of the litigation concerning a contested inheritance over three generations or more than forty years. It describes a patrimonial redemption, or "lineage claim," and provides a great deal of information concerning inheritance during the late Bronze Age. It is identified by its colophon, asumittu annītu garbarê šalati kanīk dīnim, “this stela is a copy of three sealed documents with (royal) edicts”[1] and records the legal judgments made in three successive reigns of the kings, Adad-šuma-iddina (ca. 1222–1217 BC), Adad-šuma-uṣur (ca. 1216–1187 BC) and Meli-Šipak (ca. 1186–1172 BC).[2] It is a contemporary text which confirms the sequence of these Kassite monarchs given on the Babylonian king list and provides the best evidence that the first of these was unlikely to have been merely an Assyrian appointee during their recent hegemony over Babylonia by Tukulti-Ninurta I, as his judgments were honored by the later kings... As was customary on such monuments, various deities were invoked to curse any party who might dispute the legal decision recorded on the kudurru. These included Anu, Enlil, and Ea (evil eye), Sîn, Šamaš, Adad and Marduk (tearing out the foundation); Ningursu and Bau (joyless fate), Šamaš and Adad (lawlessness); Pap-nigin-gara (destruction of the landmark), Uraš and Ninegal (evil); Kassite deities Šuqamuna and Šumalia (humiliation before the king and princes), Ištar (defeat); all the named gods (destruction of the name).

The Stele of Meli-Šipak is an ancient Mesopotamian fragment of the bottom part of a large rectangular stone edifice engraved with reliefs and the remains of Akkadian and Elamiteinscriptions. It was taken as spoil of war by Elamite king Šutruk-Naḫḫunte I during his invasion of Babylonia which deposed Kassite king Zababa-šuma-iddina. It was one of the objects found at Susabetween 1900 and 1904 by the French excavation team under Jacques de Morgan that seems to have formed part of an ancient Museum of trophies, or ex-voto offerings to the deity Inšušinak, in a courtyard adjacent to the main temple.

The Land grant to Marduk-zākir-šumi kudurru is an ancient Mesopotamian narû, or entitlement stele, recording the gift (irīmšu) of 18 bur 2 eše[1] (about 120 hectares or 300 acres) of corn-land by Kassite king of Babylon Marduk-apla-iddina I (ca. 1171–1159 BC) to his bēl pīḫati(inscribed lúEN NAM and meaning "person responsible"), or a provincial official.[2] The monument is significant in part because it shows the continuation of royal patronage in Babylonia during a period when most of the near East was beset by collapse and confusion, and in part due to the lengthy genealogy of the beneficiary, which links him to his illustrious ancestors.

Boundary stone (kudurru)Babylonian, about 978-943 BC

From Sippar, southern IraqA legal statement about the ownership of some landThis kudurru records a legal settlement of the title to an estate in the district of the city of Sha-mamitu which had formerly been the property of Arad-Sibitti and his family, but had passed through marriage to the family of Burusha, the jewel-worker.According to the cuneiform inscription, for several years previously there had been friction between the two families, and the claim to the land was contested. The text traces the history of the feud between the families. After citing the legal evidence for the transfer of the estate to Burusha's family, it lists the payment of 887 shekels of silver by which Burusha secured ownership of the land. Typically, the text ends with curses on anyone who would destroy or steal the stone. Nineteen divine symbols protect the document while the individuals shown are named as the king of Babylon, Nabu-mukin-apli (978-943 BC), facing Arad-Sibitti and his sister.Length: 26 cm

Width: 20 cm

Height: 50 cm http://www2.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antigua-universal/MESOPOTAMIA/kudurru7.htm

![]() Hinke's artwork for the divine symbols on the top of the Land grant to Munnabittu kudurru " This piece comes from the reign of Marduk-apal-iddina I (1171-1159 a.C.). The drawing is the projection of the upper part of the kudurru (adapted from The Ancient Orient, by Mario Liverani). It emphasizes the serpent coiled around the axis. The numbers indicate: 1- Sin, 2- Ishtar, 3- Shamash, 4y 5- Anu and Enlil, 6- Ea, 7-Gula, 8-Ishkhara, 9-Ninurta, 10-Zababa, 11-Nabu, 12-Nergal , 13- Nusku, 14- Adad, 15- Marduk, 16- Papsukkal, 17- Shuqamuna and Shumalia and 18- Ishtaran, god of justice." http://www2.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antigua-universal/MESOPOTAMIA/kudurru12.htm

Hinke's artwork for the divine symbols on the top of the Land grant to Munnabittu kudurru " This piece comes from the reign of Marduk-apal-iddina I (1171-1159 a.C.). The drawing is the projection of the upper part of the kudurru (adapted from The Ancient Orient, by Mario Liverani). It emphasizes the serpent coiled around the axis. The numbers indicate: 1- Sin, 2- Ishtar, 3- Shamash, 4y 5- Anu and Enlil, 6- Ea, 7-Gula, 8-Ishkhara, 9-Ninurta, 10-Zababa, 11-Nabu, 12-Nergal , 13- Nusku, 14- Adad, 15- Marduk, 16- Papsukkal, 17- Shuqamuna and Shumalia and 18- Ishtaran, god of justice." http://www2.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antigua-universal/MESOPOTAMIA/kudurru12.htm

Kudurru del rey kasita Mellishipak II (Mellishikhu) 1188-1174 av. J.-C.

![]()

![kudurru1]() | | | | | | | | | SIN(Luna) | | SHAMASH(Sol) | | Tiaras de Anu y Enlil | | Nergal(León con cetro) |

| | | Marduk(Dragón) | | Nabu(Estilete) |

| | | Adad(Rayo sobre toro de la tempestad) | | Papsukkal(ave) |

| | | Ninghizzida(Serpiente) | |

| ![]() | | ISHTAR(Estrella) | | EA(cabra-pez) | | Ninhursag(útero) |

| | Zababa(Cetro) | | Ninurta(Cetro cabeza pantera) |

| | Gula(Perro) | | | Nusku(Lámpara) |

| | Ningirsu(Arado) | | Shuqamuna y Shumalia(ave sobre trípode) |

| | | Ishara(Escorpión) | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

|

|

|

| | | | | | | SIN(Luna) | | SHAMASH(Sol) | | Tiaras de Anu y Enlil | | Nergal(León con cetro) |

| | | Marduk(Dragón) | | Nabu(Estilete) |

| | | Adad(Rayo sobre toro de la tempestad) | | Papsukkal(ave) |

| | | Ninghizzida(Serpiente) | |

| A.In the top row, from left to right, The lunar crescent moon Sin (Nanna for the Sumerians), . The star of Venus representing Ishtar (Sumerian Inanna, goddess of love and war) . And the solar disk of the god Shamash (Utu Akkadian, god of justice B. In the lower row we see the crowns (tiaras) on altars of the gods Anu (An) and Enlil, And then the goat-fish of the god Ea (Enki). Next to it is the uterus on an altar of the mother goddess Ninhursag. C. In the next row we see a winged lion with the double-headed lion scepter of the god of the underworld Nergal, .cele with bird head of the god of war Zababa And the scepter with panther head of the god Ninurta. D. In the next row we have the spear-hoe of the Babylonian god Marduk on an altar, placed on a mushhushshu dragon, . Another dragon carrying the stiletto of Nabu, god of wisdom son of Marduk, And the dog of the goddess of health Gula. E. In the last row we have the ray on a bull of the god of the storm Adad (Ishkur), The stylus of Nabu, The lamp of the god of fire Nusku, The Ningirsu plow, The bird of the messenger god Papsukkal And the bird on tripod of the divine couple cottage Shuqamuna and Shumalia, The snake of Ninghizzida And the Ishara Scorpion.

A.In the top row, from left to right, The lunar crescent moon Sin (Nanna for the Sumerians), . The star of Venus representing Ishtar (Sumerian Inanna, goddess of love and war) . And the solar disk of the god Shamash (Utu Akkadian, god of justice B. In the lower row we see the crowns (tiaras) on altars of the gods Anu (An) and Enlil, And then the goat-fish of the god Ea (Enki). Next to it is the uterus on an altar of the mother goddess Ninhursag. C. In the next row we see a winged lion with the double-headed lion scepter of the god of the underworld Nergal, .cele with bird head of the god of war Zababa And the scepter with panther head of the god Ninurta. D. In the next row we have the spear-hoe of the Babylonian god Marduk on an altar, placed on a mushhushshu dragon, . Another dragon carrying the stiletto of Nabu, god of wisdom son of Marduk, And the dog of the goddess of health Gula. E. In the last row we have the ray on a bull of the god of the storm Adad (Ishkur), The stylus of Nabu, The lamp of the god of fire Nusku, The Ningirsu plow, The bird of the messenger god Papsukkal And the bird on tripod of the divine couple cottage Shuqamuna and Shumalia, The snake of Ninghizzida And the Ishara Scorpion.

A.In the top row, from left to right, The lunar crescent moon Sin (Nanna for the Sumerians), . The star of Venus representing Ishtar (Sumerian Inanna, goddess of love and war) . And the solar disk of the god Shamash (Utu Akkadian, god of justice B. In the lower row we see the crowns (tiaras) on altars of the gods Anu (An) and Enlil, And then the goat-fish of the god Ea (Enki). Next to it is the uterus on an altar of the mother goddess Ninhursag. C. In the next row we see a winged lion with the double-headed lion scepter of the god of the underworld Nergal, .cele with bird head of the god of war Zababa And the scepter with panther head of the god Ninurta. D. In the next row we have the spear-hoe of the Babylonian god Marduk on an altar, placed on a mushhushshu dragon, . Another dragon carrying the stiletto of Nabu, god of wisdom son of Marduk, And the dog of the goddess of health Gula. E. In the last row we have the ray on a bull of the god of the storm Adad (Ishkur), The stylus of Nabu, The lamp of the god of fire Nusku, The Ningirsu plow, The bird of the messenger god Papsukkal And the bird on tripod of the divine couple cottage Shuqamuna and Shumalia, The snake of Ninghizzida And the Ishara Scorpion. http://www2.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antigua-universal/MESOPOTAMIA/kudurrusnueva_general.htm | | ISHTAR(Estrella) | | EA(cabra-pez) | | Ninhursag(útero) |

| | Zababa(Cetro) | | Ninurta(Cetro cabeza pantera) |

| | Gula(Perro) | | | Nusku(Lámpara) |

| | Ningirsu(Arado) | | Shuqamuna y Shumalia(ave sobre trípode) |

| | | Ishara(Escorpión) | |

|

|

Kassite-era kudurrus, in approximate chronological order:

Post-Kassite kudurrus:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kudurru![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() A legal statement about the freeing of taxes and obligations.

A legal statement about the freeing of taxes and obligations.

Width: 18 cmBack of the kudurru (boundary stone) for Ritti-Marduk, white limestone![]() Babylonian kudurru of the late Kassite period found near Baghdad by the French botanist André Michaux (Cabinet des Médailles, Paris)

Babylonian kudurru of the late Kassite period found near Baghdad by the French botanist André Michaux (Cabinet des Médailles, Paris)![]() Kudurru of Nazi-Maruttash

Kudurru of Nazi-Maruttash![]() Meli-Šipak presents his daughter to the goddess Nannaya

Meli-Šipak presents his daughter to the goddess Nannaya![]() Deed recording the grant of fifty GUR of corn-land by Kassite king Meli-Šipak to Ḫa-SAR-du, an official, in the British Museum.

Deed recording the grant of fifty GUR of corn-land by Kassite king Meli-Šipak to Ḫa-SAR-du, an official, in the British Museum.Thirteen gods are invoked by name together with "all the gods whose names are portrayed on this narû." These are represented by eighteen icons arranged around the conical top.

The god Marduk is pictured twice, once by a kusarikku holding a spade, and once with a marru or tasseled spade in front of the kusarikku. Ea may be represented both by the south wind and a ram-headed crook.[2] Šuqamuna and Šumalia, the Kassite deities associated with the investiture of kings are portrayed by a bird on a perch. Several of the symbols are widely attested icons of their gods such as the lunar disc for Sîn, solar disc for Šamaš, the lightning-fork for Adad, the lamp for Nusku, the leaping dog for Gula, the mace with twin lion-heads for Nergal, the eagle-headed mace for Ninurta, the eight-pointed star for Ištar, and the coiled snake for Ištaran.

![]() The Stele of Meli-Šipak identified by a colophon provided by Ellamite king Šutruk-Naḫḫunte.The limestone stele is engraved with towers, crowning battlements and separating a crenelated wall fortification below, where there is an archway in the lower of perhaps three registers. At least one row of divine symbols appears in an upper register. A human figure dressed in an ornate fringed robe and a high crown of feathers, faces a ship. A standing nude figure has been intentionally chiseled away

The Stele of Meli-Šipak identified by a colophon provided by Ellamite king Šutruk-Naḫḫunte.The limestone stele is engraved with towers, crowning battlements and separating a crenelated wall fortification below, where there is an archway in the lower of perhaps three registers. At least one row of divine symbols appears in an upper register. A human figure dressed in an ornate fringed robe and a high crown of feathers, faces a ship. A standing nude figure has been intentionally chiseled away

![]() Detail from the Land grant to Marduk-zākir-šumi kudurru

Detail from the Land grant to Marduk-zākir-šumi kudurru

Land grant to Marduk-zākir-šumi kudurruThe monument is a large rectangular block of limestone with a base of 51 by 30.5 cm and a height of 91 cm, or around 3 foot, with a broken top making it the tallest of the extant kudurrus[3] and has intentionally flattened sides.[4] It was recovered from the western bank of the Tigrisopposite Baghdad[5] and acquired by George Smith for the British Museum while on his 1873–74 expedition to Nineveh sponsored by the Daily Telegraph. It was originally given the collection reference D.T. 273 and later that of BM 90850. The face has three registers featuring eighteen symbolic representations of gods (listed below identifying the corresponding deity) and the back has three columns of text (line-art pictured right). First register:

- Crescent moon, Sîn

- Solar disc, Šamaš

- Eight-pointed star, Ištar

- Lamp, Nusku

- Walking bird, Bau

- Eagle/vulture-headed mace, Zababa

- Lion-headed mace, Nergal

- Squatting dog, Gula

- Scorpion, Išḫara

- Reversed yoke on a shrine, Ninḫursag

Second register:

- Bird on a perch, the Kassite deities Šuqamuna & Šumalia

- Reclining ox beneath lightning fork, Adad

- Spear-head behind horned dragon, Marduk

- Wedge supported by horned dragon before shrine, Nabû

Third register:

- Horned serpent spanning register, uncertain

- Turtle, uncertain

- Ram-headed crook above goat-fish, Ea

- Winged dragon stepping on hind part of serpent, uncertain

The land grant was situated west of the river Tigris in the province of Ingur-Ištar, one of perhaps twenty-two pīḫatus or provinces known from the Kassite period,[6] and was bordered by estates belonging to the (house of) Bīt-Nazi-Marduk and Bīt-Tunamissaḫ, perhaps Kassite nobility. ![]() The land grant to Marduk-apla-iddina at the Louvre. Like most kudurrus, it portrays Mesopotamian gods graphically in segmented registers on the stone. In this case the divine icons number twenty-four in five registers, rather more than usual.

The land grant to Marduk-apla-iddina at the Louvre. Like most kudurrus, it portrays Mesopotamian gods graphically in segmented registers on the stone. In this case the divine icons number twenty-four in five registers, rather more than usual.The iconic representations of the gods, where they are known, are given in the sequence left-to-right, top-to-bottom:

Two depictions of hybrid centaur archers on Kassite period kudurrus. On the left is the so-called bird-man centaur drawing a bow, and on the right is a winged horse-man centaur drawing a bow. Kudurru image on left is on a side of BM 90858. It is a limestone kudurru from ancient Sippar. It records the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (Second Dynasty of Isin) granting Šitti-Marduk freedom from taxation for services rendered during his invasion of Elam. Kudurru image on right is on a side of BM 90829. It is a limestone Kassite period (1186 BCE-1172 BCE) kudurru from ancient Sippar. There are numerous symbols carved onto the kudurru. The text contains a deed of gift of corn-land by Meli-Shipak to Khasardu.

BM 90858. White limestone kudurru for Ritti-Marduk (late 12th-century BCE).

The identification of the scorpion representations on kudurrus with the goddess Išhara is enabled through accompanying inscriptions. Assured representations of Išhara as a scorpion are identified by kudurru inscriptions dating to the 12th-century BCE. Išhara appears as a scorpion together with an inscription of her name on the registers/panels of the late Kassite kudurrus of Meli-Shipak (1188-1174 BCE) and Marduk-apla-iddina I (1173-1161 BCE). An additional 45 kudurrus depict a scorpion, but with no identifying inscription. (See: Seidl (1989; Pages 156-157).) Išhara is associated with the goddess Gula. Gula is usually the wife of Ninurta. The title of Pa-bil-sag was "vicegerent [= delegated earthly representative] of the Nether World," and he was also identified as the husband of Gula.

BM 102485 (see illustration at top of page) records a land grant to a man named Gula-eresh by Eanna-shum-idina (the governor of Sealand). The square box directly underneath the scorpion symbol represents the altar supporting the scorpion symbol of the goddess Išhara. (Consult Ursula Seidl (1989) or Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie. (Dritter Band 3, 1957-1971, Pages 483-490.)

The names provide no aid to interpret what is meant. Gir.tab simply means scorpion. Pa.bil.sag as the name of the centaur cannot be interpreted because it never occurs in any other context. (The hybrid (composite) loosely described as "scorpion archer" or "scorpion-tailed bird-man" is identified as Pabilsag.) The interpretation is given that the "scorpion-tailed bird-man" drawing a bow has a feathered body - or is wearing a feather robe. It is reasonably suggested that the scorpion-man is somewhat distinct from the "scorpion-tailed bird-man" and similar. Implying that the scorpion and centaur were not distinct is a mistake. The symbol of the scorpion-archer is identified with Ninurta the fiery god of war and the south wind. Ninurta (depicted as an archer with the body of a lion and the tail of a scorpion) standing on the back of a monster has also been identified with the planet Saturn. Pabilsag was identified with the god Ninurta.

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

from "Civilisations of the Ancient Near East"

chapter

"Ancient Mesopotamian Religious Iconography"

by Anthony Green

Principal apotropaic figures

note: "Fig.1" relates to "Principal symbols of deities"

![]()

1.human-headed winged or wingless bull,

Early Dynastic - Achaemenid,

commonly identified as lamassu/šedu. The wingless form may sometimes be a form of kusarrikku "bison"

(but cf.no.9).

![]()

2.human-headed winged lion,

Middle-Assyrian - Neo-Assyrian

commonly identified as šeedu (or aladlammû)

![]()

3.dog, sitting or standing (cf. Fig.no.22)

Old Babylonian - Late Babylonian,

kalbu "dog" (as protective type)

![]()

4.horned snake (see Fig.1 no. 25),

Akkadian?/Kassite - Neo-Assyrian,

bašmu/ušumgallu, "poisonous snake"

![]()

5.(snake-)dragon (=Fig.1, no.30)

Akkadian - Selekuid

mušḫuššu "furious snake"

![]()

6."lion-dragon (=Fig.1,no.31),

Akkadian - Late Babylonian,

possibly ûmu naa´iru "roaring weather-beast"

![]()

7.goat-fish (=Fig.1, no.32),

Neo Sumerian - Selekuid,

suḫurmašû carp-goat

![]()

8.long-haired hero,

Uruk/Early Dynastic - Islamic,

lahmu "hairy" Originally associated with the water-god Enki/Ea, later apparently transfered to Marduk (often holds Fig.1, no.8) or protective in a general way.

![]()

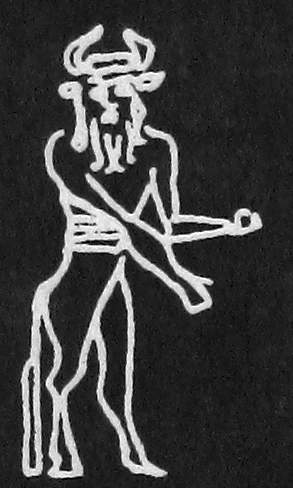

9.bull-man,

Early Dynastic II - Achaemenid,

kusarikku "bison(-man)" originally associated with the sun-god Shamash

![]()

10.scorpion-man,

Early Dynastic III - Selekuid,

girtablullû "scorpion-man". Associated with sun-god Shamash

![]()

11."lion-humanoid" (upright leonide man),

Kassite - Selekuid,

uridimmu "mad lion" (literally "mad canine").

![]()

12."lion-garbed figure" (human-bodied figure in a lion´s pelt and mask),

Neo-Assyrian,

Possibly the god Latarak ( and human imitations).

![]()

13.lion-demon,

Akkadian/Old Babylonian - Selekuid,

ugallu "big weather-beast."

![]()

14.lion-centaur,

Middle-Assyrian - Neo-Assyrian,

urmaḫlullû "lion-man"

![]()

15.merman,

Neo-Sumerian - Selekuid,

kulullû "fish-man"

mermaid,

Old Babylonian - Late Babylonian (probably?. influencing greek and european art)

kuliltu "fish-woman"

![]()

16."fish-garbed figure" (human-bodied figure in a fish-skin),

Kassite - Selekuid,

apkallu "sage" (in fish-guise)

![]()

18.griffin-demon,

Middle Assyrian (with andecedents from Early Dynastic III?) - Selekuid,

apkallu "sage" (in bird-guise)

![]()

18.antropomorphic god with bucket and cone,

Middle-Assyrian - Neo-Assyrian,

possibly apkallu "sage" (in human guise)

![]()

19.antropomorphic goddess with ring of beads,

Neo-Assyrian,

it has been suggested that this is connected with Narudu, sister of the Sebittu, or with the goddess Ishtar

![]()

20.antropomorphic god with axe and dagger,

Neo-Assyrian,

Sebittu "Seven(gods)"

![]()

21.antropomorphic god with axe and mace,

Neo-Assyrian,

the netherworld-god Meslamtaea; an identical pair may be the twin gods Meslamtaea and Lugal-Irra

![]()

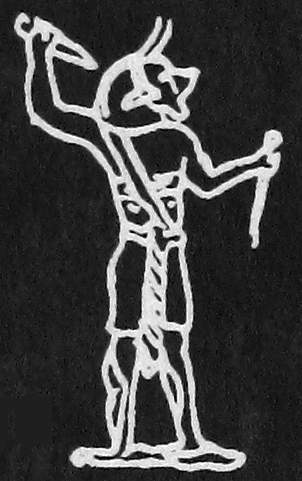

22.smiting god

Neo-Assyrian(with entecedents from Old Babylonian) - Late Babylonian,

possibly the god Lulal

![]()

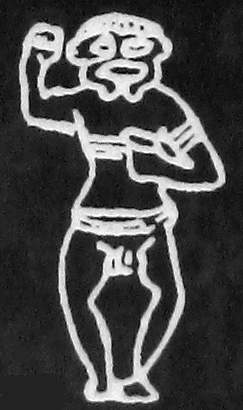

23.bowlegged dwarf,

Neo-Assyrian (with Old Babylonian antecedents?) - Late Babylonian,

ritual dancer(?)/demon like Egyptian Bes

![]()

24.gignatic monstrous human figure,

Old Babylonian - Late Babylonian,

the demon Khuwawa/Khumbaba

![]()

25.canine/leonine demon,

Neo-Assyrian - Late Babylonian,

the god Pazuzu

"Aššur

Assyrian god, the eponymous deity of the capital Aššur who became the

national god of Assyria.

The origin of the name is unknown. He seems to have been a local

mountain god of the Semitic population of northern Mesopotamia (bel