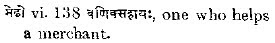

Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/hnagupz

See: http://static.scribd.com/docs/km058hvpku1jx.pdf Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans by Calvert Watkins This is the most lucid exposition of IE linguistics to indicate possible ancestral words such as ayes'copper, perhaps bronze'.

Migrations of Meluhhans who contributed to the Bronze Age revolution and documented metalwork catalogues on Indus Script Corpora (ca. 7000 inscriptions) explain the presence of hieroglyphs as hypertexts -- in lingua franca as distinct from literary forms such as Vedic Chandas -- in Ancient Near East framed by the following three expressions: Mazda, Druids and Tuisto. All three expressions are traceable to the Vedic tradition.

Mazda is associated with Avestan which developed after Vedic. Druids are associated with Karnonou (Cernunnos) attested on Pillar of Boatmen. Tuisto cognate with Vedic Tvaṣṭr̥ is considered the Founder of the Germanic People.

Avestan haoma (cognate soma) was based on herbal preparation, while Vedic soma of Soma samsthA was based on metallic stones.

See:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/legend-of-anzu-which-stole-tablets-of.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/legend-of-anzu-which-stole-tablets-of.html

The links provide arguments of Georges Pinault equating Vedic ams'u 'soma' with ancu 'iron' (Tocharian)

I suggest that references in Rigveda related to Soma are metaphorical expressions of 'drink' in Chandas (Vedic Samskrtam), while the product processed results in a molten state and do NOT constitute a direct reference to a herbal fluid or juice.

Mazda

[quote]2 The name by which the Zoroastrians call their own religion is Mazdayasna, the religion of Ahura Mazda (Sanskrit Asura Medh¯a, “Lord of Wisdom”). The R. gveda 8.6.10 has the expression medh¯am r.tasya, “wisdom of truth”.[unquote]

http://www.archaeologyonline.net/sites/default/files/imported/artifacts/Vedic_Religion_in_Ancient_Iran.pdf

I suggest that the expression Zoroastrian mazda is related to मेध 'yajna' and मेधा 'wisdom'.

Arguing that Samskrtam is older than Avestan, Kazanas suggests that Avestan broke away the Saptasindhu moving northwestwards. See: Kazanas,Nicholas, 2015, Vedic and Indo-European Studies, Delhi, Aditya Prakashan, Chapter 4.

1. मेध [p= 832,3] an animal sacrifice, offering , oblation , any sacrifice (esp. ifc.) ib. MBh. &c मेधा f. mental vigour or power , intelligence , prudence , wisdom (pl. products of intelligence , thoughts , opinions) RV. &cIntelligence personified (esp. as the wife of धर्म and daughter of दक्ष) MBh. R. Hariv. Pur. a form of सरस्वती W.

2. मेधा = धन Naigh. ii , 10. See the coins pouring out of the bag held by Karnonou (Cernunnos) On the base are shown poLa 'zebu' rebus poLa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' and me

medha is an Indus Script hieroglyph and is signified by mēṇḍha 'ram'.

https://www.digitalmedievalist.com/opinionated-celtic-faqs/druids/

Druids

I have embedded an article by Peter Berresford Ellis on the Celtic-Vedic connections.

I suggest that the semantic link between IE *deru and Vedic dru- may also relate to molten fluidity of metalwork (in addition to the suggested IE *deru 'strong'). The druids of Ancient Near East may be compared with the Vedic Rishis whose insights are included in the Aranyaka-s as 'forest-seers' who would meet periodically in NamishAranya.

द्रु [502,1] to become fluid , dissolve , melt Pan5c. Vet. BhP. : Caus. द्राव्/अयति (ep. also °ते ; द्रवयते » under द्रव्/अ) to cause to run , make flow RV. viii , 4 , 11 ; to make fluid , melt , vi , 4 , 3 ; mn. (= 3. दारु) wood or any wooden implement (as a cup , an oar &c ) RV. TBr. Mn.; m. a tree or branch HParis3.

(cf. इन्द्र- सु- , हरिद्- , हरि-). See Root/lemma *deru in IE (appended).

Root / lemma: andh-, anedh-

English meaning: `to grow, bloom, blossom'

German meaning: `hervorstechen, sprießen, blühen'

Material: Old Indian ándhaḥ n. `Soma plants'; arm. and `field'; gr. ἄνθος n. `Flower, bloom', ἀνθέω `blossoms', ἄνθηρός (*-es-ro-) `blossoming' etc; alb. ënde(*andhōn) `blossom, flower', ë̄ndem `blossoms' (ë from present *ë̄ from *andhō); toch. A ānt, В ānte `open space, area'.

Mir. ainder, aindir `young woman', cymr. anner `young cow', Pl. anneirod, acymr. enderic `a bull-calf; also of the young of other animals', cymr. enderig `bull, ox', bret. ounner (Trég. annouar, Vannes an̄noér) `young cow';

moreover frz. (l)andier m. `Fire goat, Aries', also `poppy' (= `young girl', compare ital. madona, fantina `poppy'), further to bask. andere `woman', iber. FNAndere, Anderca, MN Anderus; maybe kelt. Origin? (*andero- `blossoming, young'?).

http://dnghu.org/indoeuropean.html

Meet the Brahmins of ancient Europe, the high caste of Celtic society

By Peter Berresford Ellis

The Celtic people spread from their homeland in what is now Germany across Europe in the first millennium bce. Iron tools and weapons rendered them superior to their neighbors. They were also skilled farmers, road builders, traders and inventors of a fast two-wheeled chariot. They declined in the face of Roman, Germanic and Slavic ascendency by the second centuries bce. Here Peter Berresford Ellis, one of Europe's foremost experts of the Celts, explains how modern research has revealed the amazing similarities between ancient Celt and Vedic culture. The Celt's priestly caste, the Druids, has become a part of modern folklore. Their identity is claimed by New Age enthusiasts likely to appear at annual solstice gatherings around the ancient megaliths of northwest Europe. While sincerely motivated by a desire to resurrect Europe's ancient spiritual ways, Ellis says these modern Druids draw more upon fanciful reconstructions of the 18th century than actual scholarship.

The Druids of the ancient Celtic world have a startling kinship with the brahmins of the Hindu religion and were, indeed, a parallel development from their common Indo-European cultural root which began to branch out probably five thousand years ago. It has been only in recent decades that Celtic scholars have begun to reveal the full

extent of the parallels and cognates between ancient Celtic society and Vedic culture.

The Celts were the first civilization north of the European Alps to emerge into recorded history. At the time of their greatest expansion, in the 3rd century bce, the Celts stretched from Ireland in the west, through to the central plain of Turkey in the east; north from Belgium, down to Cadiz in southern Spain and across the Alps into the Po Valley of Italy. They even impinged on areas of Poland and the Ukraine and, if the amazing recent discoveries of mummies in China's province of Xinjiang are linked with the Tocharian texts, they even moved as far east as the area north of Tibet.

The once great Celtic civilization is today represented only by the modern Irish, Manx and Scots, and the Welsh, Cornish and Bretons. Today on the northwest fringes of Europe cling the survivors of centuries of attempted conquest and "ethnic cleansing" by Rome and its imperial descendants. But of the sixteen million people who make up those populations, only 2.5 million now speak a Celtic language as their mother tongue.

The Druids were not simply priesthood. They were the intellectual caste of ancient Celtic society, incorporating all the professions: judges, lawyers, medical doctors, ambassadors, historians and so forth, just as does the brahmin caste. In fact, other names designate the specific role of the "priests." Only Roman and later Christian propaganda turned them into "shamans,""wizards" and "magicians." The scholars of the Greek Alexandrian school clearly described them as a parallel caste to the brahmins of Vedic society.

The very name Druid is composed of two Celtic word roots which have parallels in Sanskrit. Indeed, the root vid for knowledge, which also emerges in the Sanskrit word Veda, demonstrates the similarity. The Celtic root dru which means "immersion" also appears in Sanskrit. So a Druid was one "immersed in knowledge."

Because Ireland was one of the few areas of the Celtic world that was not conquered by Rome and therefore not influenced by Latin culture until the time of its Christianization in the 5th century ce, its ancient Irish culture has retained the most clear and startling parallels to Hindu society.

Professor Calvert Watkins of Harvard, one of the leading linguistic experts in his field, has pointed out that of all the Celtic linguistic remains, Old Irish represents an extraordinarily archaic and conservative tradition within the Indo-European family. Its nominal and verbal systems are a far truer reflection of the hypothesized parent tongue, from which all Indo-European languages developed, than are Classical Greek or Latin. The structure of Old Irish, says Professor Watkins, can be compared only with that of

Vedic Sanskrit or Hittite of the Old Kingdom.

The vocabulary is amazingly similar. The following are just a few examples:

Old Irish - arya (freeman),Sanskrit - aire (noble)

Old Irish - naib (good), Sanskrit - noeib (holy)

Old Irish - badhira (deaf), Sanskrit - bodhar (deaf)

Old Irish - names (respect), Sanskrit - nemed (respect)

Old Irish - righ (king), Sanskrit - raja (king)

This applies not only in the field of linguistics but in law and social custom, in mythology, in folk custom and in traditional musical form. The ancient Irish law system, the Laws of the Fénechus, is closely parallel to the Laws of Manu. Many surviving Irish myths, and some Welsh ones, show remarkable resemblances to the themes, stories and even names in the sagas of the Indian Vedas.

Comparisons are almost endless. Among the ancient Celts, Danu was regarded as the "Mother Goddess." The Irish Gods and Goddesses were the Tuatha De Danaan ("Children of Danu"). Danu was the "divine waters" falling from heaven and nurturing Bíle, the sacred oak from whose acorns their children sprang. Moreover, the waters of Danu went on to create the great Celtic sacred river--Danuvius, today called the Danube. Many European rivers bear the name of Danu--the Rhône (ro- Dhanu, "Great Danu") and several rivers called Don. Rivers were sacred in the Celtic world, and places where votive offerings were deposited and burials often conducted. The Thames, which flows through London, still bears its Celtic name, from Tamesis, the dark river, which is the same name as Tamesa, a tributary of the Ganges.

Not only is the story of Danu and the Danube a parallel to that of Ganga and the Ganges but a Hindu Danu appears in the Vedic story "The Churning of the Oceans," a story with parallels in Irish and Welsh mytholgy. Danu in Sanskrit also means "divine waters" and "moisture."

In ancient Ireland, as in ancient Hindu society, there was a class of poets who acted as charioteers to the warriors They were also their intimates and friends. In Irish sagas these charioteers extolled the prowess of the warriors. The Sanskrit Satapatha Brahmana says that on the evening of the first day of the horse sacrifice (and horse sacrifice was known in ancient Irish kingship rituals, recorded as late as the 12th century) the poets had to chant a praise poem in honor of the king or his warriors, usually extolling their genealogy

and deeds.

Such praise poems are found in the Rig Veda and are called narasamsi. The earliest surviving poems in old Irish are also praise poems, called fursundud, which trace back the genealogy of the kings of Ireland to Golamh or Mile Easpain, whose sons landed in Ireland at the end of the second millennium bce. When Amairgen, Golamh's son, who later traditions hail as the "first Druid," set foot in Ireland, he cried out an extraordinary incantation that could have come from the Bhagavad Gita, subsuming all things into his being.

Celtic cosmology is a parallel to Vedic cosmology. Ancient Celtic astrologers used a similar system based on twenty-seven lunar mansions, called nakshatras in Vedic Sanskrit. Like the Hindu Soma, King Ailill of Connacht, Ireland, had a circular palace constructed with twenty-seven windows through which he could gaze on his twenty-seven "star wives."

There survives the famous first century bce Celtic calendar (the Coligny Calendar) which, as soon as it was first discovered in 1897, was seen to have parallels to Vedic calendrical computations. In the most recent study of it, Dr. Garret Olmsted, an astronomer as well as Celtic scholar, points out the startling fact that while the surviving calendar was manufactured in the first century bce, astronomical calculus shows that it must have been computed in 1100 bce.

One fascinating parallel is that the ancient Irish and Hindus used the name Budh for the planet Mercury. The stem budh appears in all the Celtic languages, as it does in Sanskrit, as meaning "all victorious,""gift of teaching,""accomplished,""enlightened,""exalted" and so on. The names of the famous Celtic queen Boudicca, of ancient Britain (1st century ce), and of Jim Bowie (1796-1836), of the Texas Alamo fame, contain the same root. Buddha is the past participle of the same Sanskrit word--"one who is enlightened."

For Celtic scholars, the world of the Druids of reality is far more revealing and exciting, and showing of the amazingly close common bond with its sister Vedic culture, than the inventions of those who have now taken on the mantle of modern "Druids," even when done so with great sincerity.

If we are all truly wedded to living in harmony with one another, with nature, and seeking to protect endangered species of animal and plant life, let us remember that language and culture can also be in ecological danger. The Celtic languages and cultures today stand on the verge of extinction. That is no natural phenomenon but the result of centuries of politically directed ethnocide. What price a "spiritual awareness" with the ancient Celts when their culture is in the process of being destroyed or reinvented? Far better we seek to understand and preserve intact the Celt's ancient wisdom. In this, Hindus may prove good allies.

The Song of Amairgen the Druid I am the wind that blows across the sea; I am the wave of the ocean; I am the murmur of the billows; I am the bull of the seven combats; I am the vulture on the rock; I am a ray of the sun; I am the fairest of flowers; I am a wild boar in valor; I am a salmon in the pool; I am a lake on the plain; I am the skill of the craftsman; I am a word of science; I am the spearpoint that gives battle; I am the God who creates in the head of man the fire of thought. Who is it that enlightens the assembly upon the mountain, if not I? Who tells the ages of the moon, if not I? Who shows the place where the sun goes to rest, if not I? Who is the God that fashions enchantments-- The enchantment of battle and the wind of change?

Amairgen was the first Druid to arrive in Ireland. Ellis states, "In this song Amairgen subsumes everything into his own being with a philosophic outlook that parallels the declaration of Krishna in the Hindu Bhagavad-Gita." It also is quite similar in style and content to the more ancient Sri Rudra chant of the Yajur Veda.

Peter Berresford Ellis is one of the foremost living authorities on the Celts and author of many books on the subject, including "Celt and Roman,""Celt and Greek,""Dictionary of Celtic Mythology" and "Celtic Women."

PETER BERRESFORD ELLIS, 30 GRESLEY ROAD, LONDON, N19 3JZ, ENGLAND

http://www.hinduwisdom.info/articles_hinduism/258.htm

Root / lemma: deru-, dō̆ru-, dr(e)u-, drou-; dreu̯ǝ- : drū-

English meaning: tree

German meaning: `Baum', probably originally and actually `Eiche'

Note: see to the precise definition Osthoff Par. I 169 f., Hoops Waldb. 117 f.; in addition words for various wood tools as well as for `good as heartwood hard, fast, loyal'; Specht (KZ. 65, 198 f., 66, 58 f.) goes though from a nominalized neuter of an adjective *dṓru `das Harte', from which previously `tree' and `oak':dṓru n., Gen. dreu-s, dru-nó-s

Material: Old Indian dā́ru n. `wood' (Gen. drṓḥ, drúṇaḥ, Instr. drúṇā, Lok. dā́ruṇi; dravya- `from tree'), drú- n. m. `wood, wood tool', m. `tree, bough', av. dāuru`tree truck, bit of wood, weapon from wood, perhaps club, mace, joint' (Gen. draoš), Old Indian dāruṇá- `hard, rough, stern' (actually `hard as wood, lumpy'),dru- in compounds as dru-pāda- `klotzfößig', dru-ghnī `wood ax' (-wooden rod), su-drú-ḥ `good wood'; dhruvá- `tight, firm, remaining' (dh- through folk etymology connection in dhar- `hold, stop, prop, sustain' = av. dr(u)vō, Old pers. duruva `fit, healthy, intact', compare Old Church Slavic sъ-dravъ); av. drvaēna-`wooden', Old Indian druváya-ḥ `wooden vessel, box made of wood, the drum', drū̆ṇa-m `bow, sword' (uncovered; with ū npers. durūna, balučī drīn `rainbow'),druṇī `bucket; pail', dróṇa-m `wooden trough, tub'; drumá-ḥ `tree' (compare under δρυμός);

Old Indian dárviḫḥ, darvī́ `(wooden) spoon';

arm. tram `tight, firm' (*drū̆rāmo, Pedersen KZ. 40, 208); probably also (Lidén Arm. stem 66) targal `spoon' from *dr̥u̯- or *deru̯-.

Gr. δόρυ `tree truck, wood, spear, javelin' (Gen. hom. δουρός, trag. δορός from *δορFός, δούρατος, att. δόρατος from *δορFn̥τος, whose n̥ is comparable with Old Indian drúṇaḥ);

kret. δορά (*δορFά) `balk, beam' (= lit. lett. darva);

sizil. ἀσχέδωρος `boar' (after Kretschmer KZ. 36, 267 f. *ἀν-σχε-δορFος or -δωρFος `standing firm to the spear'), ark. dor. Δωρι-κλῆς, dor. böot. Δωρί-μαχος under likewise, Δωριεύς `Dorian' (of Δωρίς `timberland');

Note:

Who were Dorian tribesö Dorians were Celtic tribes who worshipped trees. In Celtic they were called Druids, priests of ancient Gaul and Britain (also Greece and Illyria). The caste of Druids must have worshiped the dominant thunder god whose thunderbolt used to strike sacred trees. Druids must have planted the religion around the sacred oak at Dodona.

δρῦς, δρυός `oak, tree' (from n. *dru or *deru, *doru g.*druu̯ós become after other tree name to Fem.; as a result of the tendency of nominative gradation), ἀκρό-δρυα `fruit tree', δρυ-τόμος `woodchopper', δρύινος `from the oak, from oak tree', Δρυάς `dryad, tree nymph', γεράνδρυον `old tree truck', ἄδρυα πλοῖα μονόξυλα. Κύπριοι Hes. (*sm̥-, Lit. by Boisacq s. v.), ἔνδρυον καρδία δένδρου Hes.

Hom. δρῠμά n. Pl. `wood, forest', nachhom. δρῡμός ds. (the latter with previous changed length after δρῦς); δένδρεον `tree' (Hom.; out of it att. δένδρον), from redupl. *δeν(= δερ)-δρεFον, Demin. δενδρύφιον; compare Schwyzer Gr. Gr. I 583;

δροF- in arg. δροόν ἰσχυρόν. ᾽Αργεῖοι Hes., ἔνδροια καρδία δένδρου καὶ τὸ μέσον Hes., Δροῦθος (*ΔροF-υθος), δροίτη `wooden tub, trough, coffin' (probably from *δροFίτᾱ, compare lastly Schwyzer KZ. 62, 199 ff., different Specht Dekl. 139); δοῖτρον πύελον σκάφην Hes. (diss. from *δροFιτρον), next to which *dr̥u̯io-in δραιόν μάκτραν. πύελον Hes.

PN Δρύτων: lit. Drūktenis, Old Prussian Drutenne (E. Fraenkel, Pauly-Wissowa 16, 1633);

in vocalism still not explained certainly δρίος `shrubbery, bush, thicket'; maked. δάρυλλος f. `oak' Hes. (*deru-, compare air. daur); but δρίς δύναμις Hes., lies δFίς (Schwyzer Gr. Gr. I 4955);

alb. dru f. `wood, tree, shaft, pole' (*druu̯ā, compare Old Church Slavic drъva n. pl. `wood'); drush-k (es-stem) `oak'; ablaut. *drū- in driḫzë `tree', dröni `wood bar';

Note:

Alb. definite form Nom. dru-ni = alb. Gen. dru-ni `of wood': Old Indian dā́ru n. `wood' (Gen. drṓḥ, drúṇaḥ `of wood'; but a pure Slavic loanword is alb. druvar`woodcutter, woodchopper'

[conservative definitive forms versus indefinite forms (alb. phonetic trait)]

thrak. καλαμίν-δαρ `sycamore', PN Δάρανδος, Τάραντος (*darḫant-) `Eichstött a district in Bavaria', Ζίνδρουμα, Δινδρύμη `Zeus's grove', VN ᾽Ο-δρύ-σ-αι, Δρόσοι, Dru-geri (dru- `wood, forest');

Maybe VN ᾽Ο - δρύ - σ - αι : Etruria (Italy)

from Lat. perhaps dūrus `hard, harsh; tough, strong, enduring; in demeanour or tastes, rough, rude, uncouth; in character, hard, austere,sometimes brazen, shameless; of things, hard, awkward, difficult, adverse' (but about dūrāre `to make hard or hardy, to inure; intransit., to become hard or dry; to be hard or callous; to endure, hold out; to last, remain, continue' see under S. 220), if after Osthoff 111 f. as `strong, tight, firm as (oak)tree' dissimilated from *drū-ro-s (*dreu-ro-sö);

Maybe alb. duroj `endure, last', durim `patience' .

but lat. larix `larch tree', Lw. is from an idg. Alpine language, idg. *derik-s, is conceivable because of heavy l;

Note:

Common lat. d- > l- phonetic mutation hence lat. larix (*derik-s) `larch tree'.

Maybe Pelasgian Larissa (*dariksa)

air. derucc (gg), Gen. dercon `glans', cymr. derwen `oak' (Pl. derw), bret. deruenn ds., gall. place name Dervus (`oak forest'), abrit. Derventiō, place name, VNDervāci under likewise; air. dērb `safe'; reduced grade air. daur, Gen. daro `oak' (deru-), also dair, Gen. darach ds. (*deri-), air. daurde and dairde `oaken'; derived gall. *d(a)rullia `oak' (Wartburg III 50); maked. δάρυλλος f. `oak'; zero grade *dru- in intensification particle (ö different Thurneysen ZcPh. 16, 277: `oak-': dru- in galat. δρυ-ναίμετον `holy oak grove'), e.g. gall. Dru-talos (`*with big forehead'), Druides, Druidae Pl., air. drūi `Druid' (`the high; noble', *druḫu̯id-), air. dron `tight, firm' (*drunos, compare Old Indian dru-ṇa-m, dāru-ṇá-, dró-ṇa-m), with guttural extension (compare under nhd. Trog) mir. drochta `(*wooden) barrel, vat, cask; barrel, tub', drochat `bridge'; here also gallorom. drūtos `strong, exuberant (: lit. drūtas)', gr. PN Δρύτων, air. drūth `foolish, loony' (: aisl. trūðr`juggler, buffoon'ö), cymr. drud `foolish, loony, valiant' (cymr. u derives from roman. equivalent);

deru̯- in germ. Tervingl, Matrib(us) Alatervīs, anord. tjara (*deru̯ōn-), finn. Lw. terva, ags. teoru n., tierwe f., -a m. `tar, resin' (*deru̯i̯o-), mnd. tere `tar' (nhd.Teer); anord. tyrvi, tyri `pinewood', tyrr `pine' (doubtful mhd. zirwe, zirbel `pine cone', there perhaps rather to mhd. zirbel `whirl', because of the round spigot);

dreu̯- in got. triu n. `wood, tree', anord. trē, ags. trēow (engl. tree), as. trio `tree, balk, beam'; in öbtr. meaning `tight, firm - tight, firm relying' (as gr. ἰσχῡρός `tight, firm': ἰσχυρίζομαι `show firmly, rely on whereupon, trust in'), got. triggws (*treu̯u̯az) `loyal, faithful', ahd. gi-triuwi `loyal, faithful', an: tryggr `loyal, faithful, reliable, unworried', got. triggwa `alliance, covenant', ags. trēow `faith, belief, loyalty, verity', ahd. triuwa, nhd. Treue, compare with ders. meaning, but other ablaut anord. trū f. `religious faith, belief, assurance, pledge', ags. trŭwa m., mnd. trūwe f. ds., ahd. trūwa, aisl. trū f., besides trūr `loyal, faithful'; derived anord. trūa `trust, hold for true' = got. trauan, and ags. trŭwian, as. trūōn, ahd. trū(w)ēn `trust' (compare n. Old Prussian druwis); similarly anord. traustr `strong, tight, firm', traust n. `confidence, reliance, what one can count on', ahd. trōst `reliance, consolation' (*droust-), got. trausti `pact, covenant', changing through ablaut engl. trust `reliance' (mengl. trūst), mlat. trustis `loyalty' in afrönk. `law', mhd. getröste `troop, multitude, crowd';

maybe alb. trös, trys `press, crowd'

(st- formation is old because of npers. durušt `hard, strong', durust `fit, healthy, whole'; norw. trysja `clean the ground', ags. trūs `deadwood', engl. trouse, aisl.tros `dross', got. ufar-trusnjan `disperse, scatter'.

*drou- in ags. trīg, engl. tray `flat trough, platter', aschwed. trö `a certain measure vessel' (*trauja-, compare above δροίτη), anord. treyju-sǫðull (also trȳju-sǫðoll) `a kind of trough shaped saddle';

*drū- in aisl. trūðr `jester', ags. trūð `merrymaker, trumpeter' (:gallorom. *drūto-s, etc)ö

*dru- in ags. trum `tight, firm, strong, fit, healthy' (*dru-mo-s), with k-extension, respectively forms -ko- (compare above mir. drochta, drochat), ahd. nhd. trog, ags. trog, troh (m.), anord. trog (n.) `trough' and ahd. truha `footlocker', norw. mdartl. trygje n. `a kind of pack saddle or packsaddle', trygja `a kind of creel', ahd. trucka `hutch', nd. trögge `trough' and with the original meaning `tree, wood' ahd. hart-trugil `dogwood';

maybe nasalized alb. trung (*trögge) `wood, tree'

bsl. *deru̯a- n. `tree' in Old Church Slavic drěvo (Gen. drěva, also drěvese), skr. dial. drêvo (drȉjevo), sloven. drẹvộ, ačech. dřěvo, russ. dérevo, klr. dérevo `tree'; in addition as originally collective lit. dervà, (Akk. der̃vą) f. `chip of pinewood; tar, resinous wood'; ablaut, lett. dar̃va `tar', Old Prussian in PN Derwayn; lengthened grade *dōru̯-i̯ā- in lett. dùore f. `wood vessel, beehive in tree';*su-doru̯a- `fit, healthy' in Old Church Slavic sъdravъ, čech. zdráv (zdravý), russ. zdoróv (f.zdoróva) `fit, healthy', compare av. dr(u)vō, Old pers. duruva ds.

balt. *dreu̯i̯ā- f. `wood beehive', substantiv. adj. (Old Indian dravya- `belonging to the tree') : lit. drẽvė and drevė̃ `cavity in tree', lett. dreve ds.: in ablaut lit.dravìs f., lett. drava f. `wood beehive', in addition Old Prussian drawine f. `prey, bee's load' and lit. dravė̃ `hole in tree'; furthermore in ablaut ostlit. drėvė̃ anddrovė̃ f. ds., lett. drava `cavity in beehive';

proto slav.. *druu̯a- Nom. Pl. `wood' in Old Church Slavic drъva, russ. drová, poln. drwa (Gen. drew); *druu̯ina- n. `wood' in klr. drovno, slovz. drẽvnø;

slav. *drъmъ in russ. drom `virgin forest, thicket', etc (= Old Indian drumáḫḥ, gr. δρυμός, adjekt. ags. trum);

lit. su-drus `abundant, fat (from the growth of the plants)' (= Old Indian su-drú-ḥ `good wood');

balt. drūta- `strong' (== gallorom. *drūto-s, gr. PN Δρύτων) in lit. drū́tas, driū́tas `strong, thick', Old Prussian in PN Drutenne, PN Druthayn, Druthelauken; belongs to Old Prussian druwis m. `faith, belief', druwi f., druwīt `believe' (*druwēti: ahd. trūen), na-po-druwīsnan `reliance, hope'. Beside lit. drū́tas also drū́ktas; see under dher-2.

In ablaut here Old Church Slavic drevlje `fore, former, of place or time; higher in importance, at first or for the first time', ačech. dřéve, russ. drévle `ages before'; adverb of comparative or affirmative.

hitt. ta-ru `tree, wood', Dat. ta-ru-ú-i;

here also probably toch. AB or `wood' (false abstraction from *tod dor, K. Schneider IF. 57, 203).

Note:

The shift d- > zero is a balt.-illyr. phonetic mutation inherited by toch.

References: WP. I 804 ff., WH. I 374, 384 ff., 765 f., Trautmann 52 f., 56, 60 f., Schwyzer Gr. Gr. I 463, 518, Specht Dekl. 29, 54, 139.

Page(s): 214-217

http://dnghu.org/indoeuropean.html

Tuisto

![]() Tuiscon (Tuisto) as depicted in a German broadside by Nikolaus Stör c. 1543, with a caption by Burkard Waldis. According to Tacitus's Germania (98 CE), "In their ancient songs, their only form of recorded history, the Germans celebrate the earth-born god, Tuisto. They assign to him a son, Mannus, the author of their race, and to Mannus three sons,..."

Tuiscon (Tuisto) as depicted in a German broadside by Nikolaus Stör c. 1543, with a caption by Burkard Waldis. According to Tacitus's Germania (98 CE), "In their ancient songs, their only form of recorded history, the Germans celebrate the earth-born god, Tuisto. They assign to him a son, Mannus, the author of their race, and to Mannus three sons,..."

http://www.ourcivilisation.com/smartboard/shop/tacitusc/germany/chap1.htm

"According to Roman sources, Tacitus in his Annals and Histories, the Germans claimed to be descendants of the Mannus, the son of Tuisto. Tuisto relates to Vedic Tvasthar, the Vedic father-creator Sky God, who is also a name for the father of Manu (RV X.17.1-2). This makes the Rig Vedic people also descendants of Manu, the son of Tvashtar.In the Rig Veda, Tvashtar appears as the father of Indra, who fashions his thunderbolt (vajra) for him (RV X.48.3). Yet Indra is sometimes at odds with Tvashtar because is compelled to surpass him (RV III.48.3-4). Elsewhere Tvashtar’s son is Vishvarupa or Vritra, whom Indra kills, cutting off his three heads (RV X.8.8-9), (TS II.4.12, II.5.1). Indra slays the dragon, Vritra, who lays at the foot of the mountain withholding the waters, and releases the seven rivers to flow into the sea. In several instances, Vritra is called Danava, the son of the Goddess Danu who is connected to the sea (RV I.32.9; II.11.10; III.30.8; V.30.4; V.32)." https://vedanet.com/2012/06/13/vedic-origins-of-the-europeans-the-children-of-danu/

See:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/08/indus-script-hieroglyphs-on-artifacts.html Indus Script hieroglyphs on artifacts which signify Karnonou (Cernunnos), Gundestrup cauldron, Celtic tomb of Lavau (500 BCE)

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/tvastr-meluhha-of-bharatam-janam.html

See: http://static.scribd.com/docs/km058hvpku1jx.pdf Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans by Calvert Watkins This is the most lucid exposition of IE linguistics to indicate possible ancestral words such as ayes'copper, perhaps bronze'.

Migrations of Meluhhans who contributed to the Bronze Age revolution and documented metalwork catalogues on Indus Script Corpora (ca. 7000 inscriptions) explain the presence of hieroglyphs as hypertexts -- in lingua franca as distinct from literary forms such as Vedic Chandas -- in Ancient Near East framed by the following three expressions: Mazda, Druids and Tuisto. All three expressions are traceable to the Vedic tradition.

Mazda is associated with Avestan which developed after Vedic. Druids are associated with Karnonou (Cernunnos) attested on Pillar of Boatmen. Tuisto cognate with Vedic Tvaṣṭr̥ is considered the Founder of the Germanic People.

Avestan haoma (cognate soma) was based on herbal preparation, while Vedic soma of Soma samsthA was based on metallic stones.

See:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/legend-of-anzu-which-stole-tablets-of.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/legend-of-anzu-which-stole-tablets-of.html

The links provide arguments of Georges Pinault equating Vedic ams'u 'soma' with ancu 'iron' (Tocharian)

I suggest that references in Rigveda related to Soma are metaphorical expressions of 'drink' in Chandas (Vedic Samskrtam), while the product processed results in a molten state and do NOT constitute a direct reference to a herbal fluid or juice.

The Chandogya in 8 chapters is Vedantic philosophy.

esha somo raja devanam annam tam deva bhakshayanti: "That soma is king; this is the devas' food. The devas eat it." [Chandogya.Upanishad (Ch.Up.]

This is the clearest statement that references to or attributes of Soma in the Vedic tradition, right from the Rigveda, should be viewed as metaphors. Even when Agni or ghee or Soma are viewed as products, the emphatic statement is that Soma is NOT for human digestion or consumption but associated with divinities, digested by the divinities (deva bhakshyanti) -- not by mortals or worshippers in the sacred yajna.

It will thus be an error to interpret Soma as an edible product. Such interpretations that Soma is a hallucinogen or an inebriant are not sanctioned by tradition. If at all there is a refrain metaphor, it relates to processing of Soma to generate or obtain wealth.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/03/soma-in-rigveda.html See also: S. Kalyanaraman,2004, Indian Alchemy, Soma in the Veda, Delhi,Munshiram Manoharlal

Mazda

[quote]2 The name by which the Zoroastrians call their own religion is Mazdayasna, the religion of Ahura Mazda (Sanskrit Asura Medh¯a, “Lord of Wisdom”). The R. gveda 8.6.10 has the expression medh¯am r.tasya, “wisdom of truth”.[unquote]

http://www.archaeologyonline.net/sites/default/files/imported/artifacts/Vedic_Religion_in_Ancient_Iran.pdf

I suggest that the expression Zoroastrian mazda is related to मेध 'yajna' and मेधा 'wisdom'.

Arguing that Samskrtam is older than Avestan, Kazanas suggests that Avestan broke away the Saptasindhu moving northwestwards. See: Kazanas,Nicholas, 2015, Vedic and Indo-European Studies, Delhi, Aditya Prakashan, Chapter 4.

This is consistent with the presence of Meluhha settlements in Ancient Near East attested in cuneiform texts. this finds confirmation in an ancient text.

Baudhāyana śrautasūtra 18.44 which documents migrations of Āyu and Amavasu from a central region:

pran Ayuh pravavraja. tasyaite Kuru-Pancalah Kasi-Videha ity. etad Ayavam pravrajam. pratyan amavasus. tasyaite Gandharvarayas Parsavo ‘ratta ity. etad Amavasavam

Trans. Ayu went east, his is the Yamuna-Ganga region (Kuru-Pancala, Kasi-Videha). Amavasu went west, his is Gandhara, Parsu and Araṭṭa.

Ayu went east from Kurukshetra to Kuru-Pancala, Kasi-Videha. The migratory path of Meluhha artisand in the lineage of Ayu of the Rigvedic tradition, to Kasi-Videha certainly included the very ancient temple town of Sheorajpur of Dist. Etawah (Kanpur), Uttar Pradesh. ![]()

1. मेध [p= 832,3] an animal sacrifice, offering , oblation , any sacrifice (esp. ifc.) ib. MBh. &c मेधा f. mental vigour or power , intelligence , prudence , wisdom (pl. products of intelligence , thoughts , opinions) RV. &cIntelligence personified (esp. as the wife of धर्म and daughter of दक्ष) MBh. R. Hariv. Pur. a form of सरस्वती W.

2. मेधा = धन Naigh. ii , 10. See the coins pouring out of the bag held by Karnonou (Cernunnos) On the base are shown poLa 'zebu' rebus poLa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' and me

medha is an Indus Script hieroglyph and is signified by mēṇḍha 'ram'.

A variety of forms एड, ēḍa, mēḍa, mēṣá -- point to collision with Aryn mḗḍhra (providing a form bhēḍra), Austro-Asiatic mēḍa and Dravidian ēḍa:

menda(A) {N} ``^sheep''. *Des.menda(GM) `sheep'. #21810. me~Da o~?-Doi {N} ``^lamb''. |me~Da `^sheep'. @N0747. #6052. gadra me~Da {N} ``^ram, ^male ^sheep''. |me~Da `sheep'. @N0745. #7240. me~Da {N} ``^sheep''. *De. menda (GM). @N0744. #14741.

me~Da o?~-Doi {N} ``^lamb''. |o~?-Doi `young of an animal'. @N0747. #14750.

gadra me~Da {N} ``^ram''. |gadra `male of sheep or goat'. @N0745. #14762.

peti me~Da {N} ``^ewe (without young)''. |peti `young female of sheep or goat'. @N0746. #14772.me~Da o~?-Doi {N} ``^lamb''. |me~Da `^sheep'. @N0747. #6053.peti me~Da {N} ``^ewe (without young)''. |me~Da `sheep'. @N0746. #14773. menda(KMP) {N} ``^sheep [MP], ewe [K], ram, ^wether [P]''. Cf. merom `goat', boda `??'. *O.menda, B.mera, H.merha, Sk.lex, ~medhra, ~mendha, Sa.bheda `ram', ~bhidi `sheep', MuNbhera, MuHbera `ram', Mu., Kh bheri(AB) `sheep', H., O. bhera `ram', H. bhera `sheep'. %21781. #21611.

menda kOnOn (P) {N} ``^lamb''. | konon `child'. *$Ho mindi hon . %21790. #21620.

mendi (P) {N} ``^sheep''. *$Mu., Ho, Bh. mindi . %21800. #21630. meram (P),, merom (KMP) {N} ``^goat [MP], she-goat [K]''. Cf. menda `sheep'. *Kh., Sa., Mu., Ho merom , So. k+mmEd/-mEd , Nic. me ; cf. O., Bh. mera `goat'. %21821. #21651. meram kOnOn (P),, merom kOnOn (P) {N} ``^kid''. | konon `child'. merom (KMP),, meram (P) {N} ``^goat [MP], she-goat [K]''. Cf. menda `sheep'. *Kh., Sa., Mu., Ho merom , So. k+mmEd/-mEd , Nic. me ; cf. O., Bh. mera `goat'. %21851. #21681. bheri (D),, bheri (AB) {NA} ``^sheep [ABD]; ^bear [D]''. *@. ??VAR. #3251. menda ,, mendi {N} ``^sheep''. @7906. ??M|F masc|fem #19501. menda (B)F {N(M)} ``(male) ^sheep''. Fem. mendi . *Loan. @B21460,N760. #22531.Ju menda (KMP) {N} ``^sheep [MP], ewe [K], ram, ^wether [P]''. Cf. merom `goat', boda `??'. *O. menda , B. mera , H. merha , Sk. lex , ~ medhra , ~ mendha , Sa. bheda `ram', ~ bhidi `sheep', MuN bhera , MuH bera `ram', Mu., Kh. bheri (AB) `sheep', H., O. bhera `ram', H. bhera `sheep'.Ju meram (P),, merom (KMP) {N} ``^goat [MP], she-goat [K]''. Cf. menda `sheep'. *Kh., Sa., Mu., Ho merom , So. k+mmEd/-mEd , Nic. me ; cf. O., Bh. mera `goat'.Ju merego (P),, mergo (P),, mirigo (M) {N} ``^deer''. *Sa. mirgi jel `a certain kind of deer', H. mrgo `deer', antelope, O. mrgo , Sk. mrga . Ju merom (KMP),, meram (P) {N} ``^goat [MP], she-goat [K]''. Cf. menda `sheep'. *Kh., Sa., Mu., Ho merom , So. k+mmEd/-mEd , Nic. me ; cf. O., Bh. mera `goat'.Go menda (A) {N} ``^sheep''. *Des. menda (GM) `sheep'.Gu me~Da {N} ``^sheep''. *Des. menda (GM).Re menda (B)F {N(M)} ``(male) ^sheep''. Fem. mendi . *Loan.(Munda etyma. STAMPE-DM--MP.NEW.84, 20-Jun-85 13:32:53, Edit by STAMPE-D Pinnow Versuch and Munda's thesis combined).

mēṭam (Ta.);[← Austro -- as. J. Przyluski BSL xxx 200: perh. Austro -- as. *mēḍra ~ bhēḍra collides with Aryan mḗḍhra -- 1 in mēṇḍhra -- m. ʻ penis ʼ BhP., ʻ ram ʼ lex. -- See also bhēḍa -- 1, mēṣá -- , ēḍa -- . -- The similarity between bhēḍa -- 1, bhēḍra -- , bhēṇḍa -- ʻ ram ʼ and *bhēḍa -- 2 ʻ defective ʼ is paralleled by that between mḗḍhra -- 1, mēṇḍha -- 1 ʻ ram ʼ and *mēṇḍa -- 1, *mēṇḍha -- 2 (s.v. *miḍḍa -- ) ʻ defective ʼ] Rebus: ![]()

https://www.digitalmedievalist.com/opinionated-celtic-faqs/druids/

Druids

I have embedded an article by Peter Berresford Ellis on the Celtic-Vedic connections.

I suggest that the semantic link between IE *deru and Vedic dru- may also relate to molten fluidity of metalwork (in addition to the suggested IE *deru 'strong'). The druids of Ancient Near East may be compared with the Vedic Rishis whose insights are included in the Aranyaka-s as 'forest-seers' who would meet periodically in NamishAranya.

द्रु [502,1] to become fluid , dissolve , melt Pan5c. Vet. BhP. : Caus. द्राव्/अयति (ep. also °ते ; द्रवयते » under द्रव्/अ) to cause to run , make flow RV. viii , 4 , 11 ; to make fluid , melt , vi , 4 , 3 ; mn. (= 3. दारु) wood or any wooden implement (as a cup , an oar &c ) RV. TBr. Mn.; m. a tree or branch HParis3.

(cf. इन्द्र- सु- , हरिद्- , हरि-). See Root/lemma *deru in IE (appended).

Root / lemma: andh-, anedh-

English meaning: `to grow, bloom, blossom'

German meaning: `hervorstechen, sprießen, blühen'

Material: Old Indian ándhaḥ n. `Soma plants'; arm. and `field'; gr. ἄνθος n. `Flower, bloom', ἀνθέω `blossoms', ἄνθηρός (*-es-ro-) `blossoming' etc; alb. ënde(*andhōn) `blossom, flower', ë̄ndem `blossoms' (ë from present *ë̄ from *andhō); toch. A ānt, В ānte `open space, area'.

Mir. ainder, aindir `young woman', cymr. anner `young cow', Pl. anneirod, acymr. enderic `a bull-calf; also of the young of other animals', cymr. enderig `bull, ox', bret. ounner (Trég. annouar, Vannes an̄noér) `young cow';

moreover frz. (l)andier m. `Fire goat, Aries', also `poppy' (= `young girl', compare ital. madona, fantina `poppy'), further to bask. andere `woman', iber. FNAndere, Anderca, MN Anderus; maybe kelt. Origin? (*andero- `blossoming, young'?).

http://dnghu.org/indoeuropean.html

Meet the Brahmins of ancient Europe, the high caste of Celtic society

By Peter Berresford Ellis

The Celtic people spread from their homeland in what is now Germany across Europe in the first millennium bce. Iron tools and weapons rendered them superior to their neighbors. They were also skilled farmers, road builders, traders and inventors of a fast two-wheeled chariot. They declined in the face of Roman, Germanic and Slavic ascendency by the second centuries bce. Here Peter Berresford Ellis, one of Europe's foremost experts of the Celts, explains how modern research has revealed the amazing similarities between ancient Celt and Vedic culture. The Celt's priestly caste, the Druids, has become a part of modern folklore. Their identity is claimed by New Age enthusiasts likely to appear at annual solstice gatherings around the ancient megaliths of northwest Europe. While sincerely motivated by a desire to resurrect Europe's ancient spiritual ways, Ellis says these modern Druids draw more upon fanciful reconstructions of the 18th century than actual scholarship.

The Druids of the ancient Celtic world have a startling kinship with the brahmins of the Hindu religion and were, indeed, a parallel development from their common Indo-European cultural root which began to branch out probably five thousand years ago. It has been only in recent decades that Celtic scholars have begun to reveal the full

extent of the parallels and cognates between ancient Celtic society and Vedic culture.

The Celts were the first civilization north of the European Alps to emerge into recorded history. At the time of their greatest expansion, in the 3rd century bce, the Celts stretched from Ireland in the west, through to the central plain of Turkey in the east; north from Belgium, down to Cadiz in southern Spain and across the Alps into the Po Valley of Italy. They even impinged on areas of Poland and the Ukraine and, if the amazing recent discoveries of mummies in China's province of Xinjiang are linked with the Tocharian texts, they even moved as far east as the area north of Tibet.

The once great Celtic civilization is today represented only by the modern Irish, Manx and Scots, and the Welsh, Cornish and Bretons. Today on the northwest fringes of Europe cling the survivors of centuries of attempted conquest and "ethnic cleansing" by Rome and its imperial descendants. But of the sixteen million people who make up those populations, only 2.5 million now speak a Celtic language as their mother tongue.

The Druids were not simply priesthood. They were the intellectual caste of ancient Celtic society, incorporating all the professions: judges, lawyers, medical doctors, ambassadors, historians and so forth, just as does the brahmin caste. In fact, other names designate the specific role of the "priests." Only Roman and later Christian propaganda turned them into "shamans,""wizards" and "magicians." The scholars of the Greek Alexandrian school clearly described them as a parallel caste to the brahmins of Vedic society.

The very name Druid is composed of two Celtic word roots which have parallels in Sanskrit. Indeed, the root vid for knowledge, which also emerges in the Sanskrit word Veda, demonstrates the similarity. The Celtic root dru which means "immersion" also appears in Sanskrit. So a Druid was one "immersed in knowledge."

Because Ireland was one of the few areas of the Celtic world that was not conquered by Rome and therefore not influenced by Latin culture until the time of its Christianization in the 5th century ce, its ancient Irish culture has retained the most clear and startling parallels to Hindu society.

Professor Calvert Watkins of Harvard, one of the leading linguistic experts in his field, has pointed out that of all the Celtic linguistic remains, Old Irish represents an extraordinarily archaic and conservative tradition within the Indo-European family. Its nominal and verbal systems are a far truer reflection of the hypothesized parent tongue, from which all Indo-European languages developed, than are Classical Greek or Latin. The structure of Old Irish, says Professor Watkins, can be compared only with that of

Vedic Sanskrit or Hittite of the Old Kingdom.

The vocabulary is amazingly similar. The following are just a few examples:

Old Irish - arya (freeman),Sanskrit - aire (noble)

Old Irish - naib (good), Sanskrit - noeib (holy)

Old Irish - badhira (deaf), Sanskrit - bodhar (deaf)

Old Irish - names (respect), Sanskrit - nemed (respect)

Old Irish - righ (king), Sanskrit - raja (king)

This applies not only in the field of linguistics but in law and social custom, in mythology, in folk custom and in traditional musical form. The ancient Irish law system, the Laws of the Fénechus, is closely parallel to the Laws of Manu. Many surviving Irish myths, and some Welsh ones, show remarkable resemblances to the themes, stories and even names in the sagas of the Indian Vedas.

Comparisons are almost endless. Among the ancient Celts, Danu was regarded as the "Mother Goddess." The Irish Gods and Goddesses were the Tuatha De Danaan ("Children of Danu"). Danu was the "divine waters" falling from heaven and nurturing Bíle, the sacred oak from whose acorns their children sprang. Moreover, the waters of Danu went on to create the great Celtic sacred river--Danuvius, today called the Danube. Many European rivers bear the name of Danu--the Rhône (ro- Dhanu, "Great Danu") and several rivers called Don. Rivers were sacred in the Celtic world, and places where votive offerings were deposited and burials often conducted. The Thames, which flows through London, still bears its Celtic name, from Tamesis, the dark river, which is the same name as Tamesa, a tributary of the Ganges.

Not only is the story of Danu and the Danube a parallel to that of Ganga and the Ganges but a Hindu Danu appears in the Vedic story "The Churning of the Oceans," a story with parallels in Irish and Welsh mytholgy. Danu in Sanskrit also means "divine waters" and "moisture."

In ancient Ireland, as in ancient Hindu society, there was a class of poets who acted as charioteers to the warriors They were also their intimates and friends. In Irish sagas these charioteers extolled the prowess of the warriors. The Sanskrit Satapatha Brahmana says that on the evening of the first day of the horse sacrifice (and horse sacrifice was known in ancient Irish kingship rituals, recorded as late as the 12th century) the poets had to chant a praise poem in honor of the king or his warriors, usually extolling their genealogy

and deeds.

Such praise poems are found in the Rig Veda and are called narasamsi. The earliest surviving poems in old Irish are also praise poems, called fursundud, which trace back the genealogy of the kings of Ireland to Golamh or Mile Easpain, whose sons landed in Ireland at the end of the second millennium bce. When Amairgen, Golamh's son, who later traditions hail as the "first Druid," set foot in Ireland, he cried out an extraordinary incantation that could have come from the Bhagavad Gita, subsuming all things into his being.

Celtic cosmology is a parallel to Vedic cosmology. Ancient Celtic astrologers used a similar system based on twenty-seven lunar mansions, called nakshatras in Vedic Sanskrit. Like the Hindu Soma, King Ailill of Connacht, Ireland, had a circular palace constructed with twenty-seven windows through which he could gaze on his twenty-seven "star wives."

There survives the famous first century bce Celtic calendar (the Coligny Calendar) which, as soon as it was first discovered in 1897, was seen to have parallels to Vedic calendrical computations. In the most recent study of it, Dr. Garret Olmsted, an astronomer as well as Celtic scholar, points out the startling fact that while the surviving calendar was manufactured in the first century bce, astronomical calculus shows that it must have been computed in 1100 bce.

One fascinating parallel is that the ancient Irish and Hindus used the name Budh for the planet Mercury. The stem budh appears in all the Celtic languages, as it does in Sanskrit, as meaning "all victorious,""gift of teaching,""accomplished,""enlightened,""exalted" and so on. The names of the famous Celtic queen Boudicca, of ancient Britain (1st century ce), and of Jim Bowie (1796-1836), of the Texas Alamo fame, contain the same root. Buddha is the past participle of the same Sanskrit word--"one who is enlightened."

For Celtic scholars, the world of the Druids of reality is far more revealing and exciting, and showing of the amazingly close common bond with its sister Vedic culture, than the inventions of those who have now taken on the mantle of modern "Druids," even when done so with great sincerity.

If we are all truly wedded to living in harmony with one another, with nature, and seeking to protect endangered species of animal and plant life, let us remember that language and culture can also be in ecological danger. The Celtic languages and cultures today stand on the verge of extinction. That is no natural phenomenon but the result of centuries of politically directed ethnocide. What price a "spiritual awareness" with the ancient Celts when their culture is in the process of being destroyed or reinvented? Far better we seek to understand and preserve intact the Celt's ancient wisdom. In this, Hindus may prove good allies.

The Song of Amairgen the Druid I am the wind that blows across the sea; I am the wave of the ocean; I am the murmur of the billows; I am the bull of the seven combats; I am the vulture on the rock; I am a ray of the sun; I am the fairest of flowers; I am a wild boar in valor; I am a salmon in the pool; I am a lake on the plain; I am the skill of the craftsman; I am a word of science; I am the spearpoint that gives battle; I am the God who creates in the head of man the fire of thought. Who is it that enlightens the assembly upon the mountain, if not I? Who tells the ages of the moon, if not I? Who shows the place where the sun goes to rest, if not I? Who is the God that fashions enchantments-- The enchantment of battle and the wind of change?

Amairgen was the first Druid to arrive in Ireland. Ellis states, "In this song Amairgen subsumes everything into his own being with a philosophic outlook that parallels the declaration of Krishna in the Hindu Bhagavad-Gita." It also is quite similar in style and content to the more ancient Sri Rudra chant of the Yajur Veda.

Peter Berresford Ellis is one of the foremost living authorities on the Celts and author of many books on the subject, including "Celt and Roman,""Celt and Greek,""Dictionary of Celtic Mythology" and "Celtic Women."

PETER BERRESFORD ELLIS, 30 GRESLEY ROAD, LONDON, N19 3JZ, ENGLAND

http://www.hinduwisdom.info/articles_hinduism/258.htm

Root / lemma: deru-, dō̆ru-, dr(e)u-, drou-; dreu̯ǝ- : drū-

English meaning: tree

German meaning: `Baum', probably originally and actually `Eiche'

Note: see to the precise definition Osthoff Par. I 169 f., Hoops Waldb. 117 f.; in addition words for various wood tools as well as for `good as heartwood hard, fast, loyal'; Specht (KZ. 65, 198 f., 66, 58 f.) goes though from a nominalized neuter of an adjective *dṓru `das Harte', from which previously `tree' and `oak':dṓru n., Gen. dreu-s, dru-nó-s

Material: Old Indian dā́ru n. `wood' (Gen. drṓḥ, drúṇaḥ, Instr. drúṇā, Lok. dā́ruṇi; dravya- `from tree'), drú- n. m. `wood, wood tool', m. `tree, bough', av. dāuru`tree truck, bit of wood, weapon from wood, perhaps club, mace, joint' (Gen. draoš), Old Indian dāruṇá- `hard, rough, stern' (actually `hard as wood, lumpy'),dru- in compounds as dru-pāda- `klotzfößig', dru-ghnī `wood ax' (-wooden rod), su-drú-ḥ `good wood'; dhruvá- `tight, firm, remaining' (dh- through folk etymology connection in dhar- `hold, stop, prop, sustain' = av. dr(u)vō, Old pers. duruva `fit, healthy, intact', compare Old Church Slavic sъ-dravъ); av. drvaēna-`wooden', Old Indian druváya-ḥ `wooden vessel, box made of wood, the drum', drū̆ṇa-m `bow, sword' (uncovered; with ū npers. durūna, balučī drīn `rainbow'),druṇī `bucket; pail', dróṇa-m `wooden trough, tub'; drumá-ḥ `tree' (compare under δρυμός);

Old Indian dárviḫḥ, darvī́ `(wooden) spoon';

arm. tram `tight, firm' (*drū̆rāmo, Pedersen KZ. 40, 208); probably also (Lidén Arm. stem 66) targal `spoon' from *dr̥u̯- or *deru̯-.

Gr. δόρυ `tree truck, wood, spear, javelin' (Gen. hom. δουρός, trag. δορός from *δορFός, δούρατος, att. δόρατος from *δορFn̥τος, whose n̥ is comparable with Old Indian drúṇaḥ);

kret. δορά (*δορFά) `balk, beam' (= lit. lett. darva);

sizil. ἀσχέδωρος `boar' (after Kretschmer KZ. 36, 267 f. *ἀν-σχε-δορFος or -δωρFος `standing firm to the spear'), ark. dor. Δωρι-κλῆς, dor. böot. Δωρί-μαχος under likewise, Δωριεύς `Dorian' (of Δωρίς `timberland');

Note:

Who were Dorian tribesö Dorians were Celtic tribes who worshipped trees. In Celtic they were called Druids, priests of ancient Gaul and Britain (also Greece and Illyria). The caste of Druids must have worshiped the dominant thunder god whose thunderbolt used to strike sacred trees. Druids must have planted the religion around the sacred oak at Dodona.

δρῦς, δρυός `oak, tree' (from n. *dru or *deru, *doru g.*druu̯ós become after other tree name to Fem.; as a result of the tendency of nominative gradation), ἀκρό-δρυα `fruit tree', δρυ-τόμος `woodchopper', δρύινος `from the oak, from oak tree', Δρυάς `dryad, tree nymph', γεράνδρυον `old tree truck', ἄδρυα πλοῖα μονόξυλα. Κύπριοι Hes. (*sm̥-, Lit. by Boisacq s. v.), ἔνδρυον καρδία δένδρου Hes.

Hom. δρῠμά n. Pl. `wood, forest', nachhom. δρῡμός ds. (the latter with previous changed length after δρῦς); δένδρεον `tree' (Hom.; out of it att. δένδρον), from redupl. *δeν(= δερ)-δρεFον, Demin. δενδρύφιον; compare Schwyzer Gr. Gr. I 583;

δροF- in arg. δροόν ἰσχυρόν. ᾽Αργεῖοι Hes., ἔνδροια καρδία δένδρου καὶ τὸ μέσον Hes., Δροῦθος (*ΔροF-υθος), δροίτη `wooden tub, trough, coffin' (probably from *δροFίτᾱ, compare lastly Schwyzer KZ. 62, 199 ff., different Specht Dekl. 139); δοῖτρον πύελον σκάφην Hes. (diss. from *δροFιτρον), next to which *dr̥u̯io-in δραιόν μάκτραν. πύελον Hes.

PN Δρύτων: lit. Drūktenis, Old Prussian Drutenne (E. Fraenkel, Pauly-Wissowa 16, 1633);

in vocalism still not explained certainly δρίος `shrubbery, bush, thicket'; maked. δάρυλλος f. `oak' Hes. (*deru-, compare air. daur); but δρίς δύναμις Hes., lies δFίς (Schwyzer Gr. Gr. I 4955);

alb. dru f. `wood, tree, shaft, pole' (*druu̯ā, compare Old Church Slavic drъva n. pl. `wood'); drush-k (es-stem) `oak'; ablaut. *drū- in driḫzë `tree', dröni `wood bar';

Note:

Alb. definite form Nom. dru-ni = alb. Gen. dru-ni `of wood': Old Indian dā́ru n. `wood' (Gen. drṓḥ, drúṇaḥ `of wood'; but a pure Slavic loanword is alb. druvar`woodcutter, woodchopper'

[conservative definitive forms versus indefinite forms (alb. phonetic trait)]

thrak. καλαμίν-δαρ `sycamore', PN Δάρανδος, Τάραντος (*darḫant-) `Eichstött a district in Bavaria', Ζίνδρουμα, Δινδρύμη `Zeus's grove', VN ᾽Ο-δρύ-σ-αι, Δρόσοι, Dru-geri (dru- `wood, forest');

Maybe VN ᾽Ο - δρύ - σ - αι : Etruria (Italy)

from Lat. perhaps dūrus `hard, harsh; tough, strong, enduring; in demeanour or tastes, rough, rude, uncouth; in character, hard, austere,sometimes brazen, shameless; of things, hard, awkward, difficult, adverse' (but about dūrāre `to make hard or hardy, to inure; intransit., to become hard or dry; to be hard or callous; to endure, hold out; to last, remain, continue' see under S. 220), if after Osthoff 111 f. as `strong, tight, firm as (oak)tree' dissimilated from *drū-ro-s (*dreu-ro-sö);

Maybe alb. duroj `endure, last', durim `patience' .

but lat. larix `larch tree', Lw. is from an idg. Alpine language, idg. *derik-s, is conceivable because of heavy l;

Note:

Common lat. d- > l- phonetic mutation hence lat. larix (*derik-s) `larch tree'.

Maybe Pelasgian Larissa (*dariksa)

air. derucc (gg), Gen. dercon `glans', cymr. derwen `oak' (Pl. derw), bret. deruenn ds., gall. place name Dervus (`oak forest'), abrit. Derventiō, place name, VNDervāci under likewise; air. dērb `safe'; reduced grade air. daur, Gen. daro `oak' (deru-), also dair, Gen. darach ds. (*deri-), air. daurde and dairde `oaken'; derived gall. *d(a)rullia `oak' (Wartburg III 50); maked. δάρυλλος f. `oak'; zero grade *dru- in intensification particle (ö different Thurneysen ZcPh. 16, 277: `oak-': dru- in galat. δρυ-ναίμετον `holy oak grove'), e.g. gall. Dru-talos (`*with big forehead'), Druides, Druidae Pl., air. drūi `Druid' (`the high; noble', *druḫu̯id-), air. dron `tight, firm' (*drunos, compare Old Indian dru-ṇa-m, dāru-ṇá-, dró-ṇa-m), with guttural extension (compare under nhd. Trog) mir. drochta `(*wooden) barrel, vat, cask; barrel, tub', drochat `bridge'; here also gallorom. drūtos `strong, exuberant (: lit. drūtas)', gr. PN Δρύτων, air. drūth `foolish, loony' (: aisl. trūðr`juggler, buffoon'ö), cymr. drud `foolish, loony, valiant' (cymr. u derives from roman. equivalent);

deru̯- in germ. Tervingl, Matrib(us) Alatervīs, anord. tjara (*deru̯ōn-), finn. Lw. terva, ags. teoru n., tierwe f., -a m. `tar, resin' (*deru̯i̯o-), mnd. tere `tar' (nhd.Teer); anord. tyrvi, tyri `pinewood', tyrr `pine' (doubtful mhd. zirwe, zirbel `pine cone', there perhaps rather to mhd. zirbel `whirl', because of the round spigot);

dreu̯- in got. triu n. `wood, tree', anord. trē, ags. trēow (engl. tree), as. trio `tree, balk, beam'; in öbtr. meaning `tight, firm - tight, firm relying' (as gr. ἰσχῡρός `tight, firm': ἰσχυρίζομαι `show firmly, rely on whereupon, trust in'), got. triggws (*treu̯u̯az) `loyal, faithful', ahd. gi-triuwi `loyal, faithful', an: tryggr `loyal, faithful, reliable, unworried', got. triggwa `alliance, covenant', ags. trēow `faith, belief, loyalty, verity', ahd. triuwa, nhd. Treue, compare with ders. meaning, but other ablaut anord. trū f. `religious faith, belief, assurance, pledge', ags. trŭwa m., mnd. trūwe f. ds., ahd. trūwa, aisl. trū f., besides trūr `loyal, faithful'; derived anord. trūa `trust, hold for true' = got. trauan, and ags. trŭwian, as. trūōn, ahd. trū(w)ēn `trust' (compare n. Old Prussian druwis); similarly anord. traustr `strong, tight, firm', traust n. `confidence, reliance, what one can count on', ahd. trōst `reliance, consolation' (*droust-), got. trausti `pact, covenant', changing through ablaut engl. trust `reliance' (mengl. trūst), mlat. trustis `loyalty' in afrönk. `law', mhd. getröste `troop, multitude, crowd';

maybe alb. trös, trys `press, crowd'

(st- formation is old because of npers. durušt `hard, strong', durust `fit, healthy, whole'; norw. trysja `clean the ground', ags. trūs `deadwood', engl. trouse, aisl.tros `dross', got. ufar-trusnjan `disperse, scatter'.

*drou- in ags. trīg, engl. tray `flat trough, platter', aschwed. trö `a certain measure vessel' (*trauja-, compare above δροίτη), anord. treyju-sǫðull (also trȳju-sǫðoll) `a kind of trough shaped saddle';

*drū- in aisl. trūðr `jester', ags. trūð `merrymaker, trumpeter' (:gallorom. *drūto-s, etc)ö

*dru- in ags. trum `tight, firm, strong, fit, healthy' (*dru-mo-s), with k-extension, respectively forms -ko- (compare above mir. drochta, drochat), ahd. nhd. trog, ags. trog, troh (m.), anord. trog (n.) `trough' and ahd. truha `footlocker', norw. mdartl. trygje n. `a kind of pack saddle or packsaddle', trygja `a kind of creel', ahd. trucka `hutch', nd. trögge `trough' and with the original meaning `tree, wood' ahd. hart-trugil `dogwood';

maybe nasalized alb. trung (*trögge) `wood, tree'

bsl. *deru̯a- n. `tree' in Old Church Slavic drěvo (Gen. drěva, also drěvese), skr. dial. drêvo (drȉjevo), sloven. drẹvộ, ačech. dřěvo, russ. dérevo, klr. dérevo `tree'; in addition as originally collective lit. dervà, (Akk. der̃vą) f. `chip of pinewood; tar, resinous wood'; ablaut, lett. dar̃va `tar', Old Prussian in PN Derwayn; lengthened grade *dōru̯-i̯ā- in lett. dùore f. `wood vessel, beehive in tree';*su-doru̯a- `fit, healthy' in Old Church Slavic sъdravъ, čech. zdráv (zdravý), russ. zdoróv (f.zdoróva) `fit, healthy', compare av. dr(u)vō, Old pers. duruva ds.

balt. *dreu̯i̯ā- f. `wood beehive', substantiv. adj. (Old Indian dravya- `belonging to the tree') : lit. drẽvė and drevė̃ `cavity in tree', lett. dreve ds.: in ablaut lit.dravìs f., lett. drava f. `wood beehive', in addition Old Prussian drawine f. `prey, bee's load' and lit. dravė̃ `hole in tree'; furthermore in ablaut ostlit. drėvė̃ anddrovė̃ f. ds., lett. drava `cavity in beehive';

proto slav.. *druu̯a- Nom. Pl. `wood' in Old Church Slavic drъva, russ. drová, poln. drwa (Gen. drew); *druu̯ina- n. `wood' in klr. drovno, slovz. drẽvnø;

slav. *drъmъ in russ. drom `virgin forest, thicket', etc (= Old Indian drumáḫḥ, gr. δρυμός, adjekt. ags. trum);

lit. su-drus `abundant, fat (from the growth of the plants)' (= Old Indian su-drú-ḥ `good wood');

balt. drūta- `strong' (== gallorom. *drūto-s, gr. PN Δρύτων) in lit. drū́tas, driū́tas `strong, thick', Old Prussian in PN Drutenne, PN Druthayn, Druthelauken; belongs to Old Prussian druwis m. `faith, belief', druwi f., druwīt `believe' (*druwēti: ahd. trūen), na-po-druwīsnan `reliance, hope'. Beside lit. drū́tas also drū́ktas; see under dher-2.

In ablaut here Old Church Slavic drevlje `fore, former, of place or time; higher in importance, at first or for the first time', ačech. dřéve, russ. drévle `ages before'; adverb of comparative or affirmative.

hitt. ta-ru `tree, wood', Dat. ta-ru-ú-i;

here also probably toch. AB or `wood' (false abstraction from *tod dor, K. Schneider IF. 57, 203).

Note:

The shift d- > zero is a balt.-illyr. phonetic mutation inherited by toch.

References: WP. I 804 ff., WH. I 374, 384 ff., 765 f., Trautmann 52 f., 56, 60 f., Schwyzer Gr. Gr. I 463, 518, Specht Dekl. 29, 54, 139.

Page(s): 214-217

http://dnghu.org/indoeuropean.html

Tuisto

Tuiscon (Tuisto) as depicted in a German broadside by Nikolaus Stör c. 1543, with a caption by Burkard Waldis. According to Tacitus's Germania (98 CE), "In their ancient songs, their only form of recorded history, the Germans celebrate the earth-born god, Tuisto. They assign to him a son, Mannus, the author of their race, and to Mannus three sons,..."

Tuiscon (Tuisto) as depicted in a German broadside by Nikolaus Stör c. 1543, with a caption by Burkard Waldis. According to Tacitus's Germania (98 CE), "In their ancient songs, their only form of recorded history, the Germans celebrate the earth-born god, Tuisto. They assign to him a son, Mannus, the author of their race, and to Mannus three sons,..." http://www.ourcivilisation.com/smartboard/shop/tacitusc/germany/chap1.htm

"According to Roman sources, Tacitus in his Annals and Histories, the Germans claimed to be descendants of the Mannus, the son of Tuisto. Tuisto relates to Vedic Tvasthar, the Vedic father-creator Sky God, who is also a name for the father of Manu (RV X.17.1-2). This makes the Rig Vedic people also descendants of Manu, the son of Tvashtar.In the Rig Veda, Tvashtar appears as the father of Indra, who fashions his thunderbolt (vajra) for him (RV X.48.3). Yet Indra is sometimes at odds with Tvashtar because is compelled to surpass him (RV III.48.3-4). Elsewhere Tvashtar’s son is Vishvarupa or Vritra, whom Indra kills, cutting off his three heads (RV X.8.8-9), (TS II.4.12, II.5.1). Indra slays the dragon, Vritra, who lays at the foot of the mountain withholding the waters, and releases the seven rivers to flow into the sea. In several instances, Vritra is called Danava, the son of the Goddess Danu who is connected to the sea (RV I.32.9; II.11.10; III.30.8; V.30.4; V.32)." https://vedanet.com/2012/06/13/vedic-origins-of-the-europeans-the-children-of-danu/

See:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/08/indus-script-hieroglyphs-on-artifacts.html Indus Script hieroglyphs on artifacts which signify Karnonou (Cernunnos), Gundestrup cauldron, Celtic tomb of Lavau (500 BCE)

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/tvastr-meluhha-of-bharatam-janam.html

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

August 26, 2016

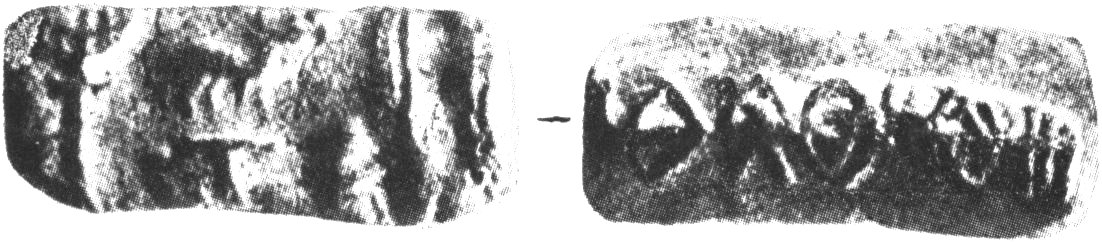

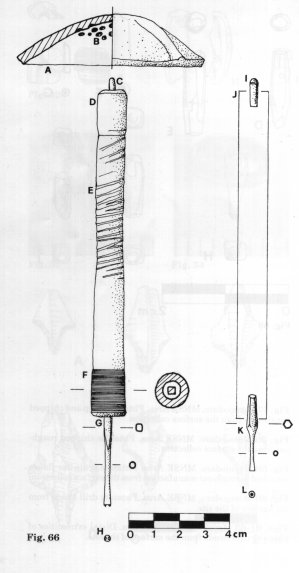

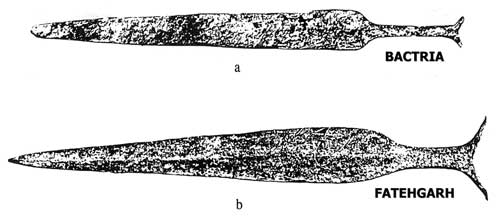

Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral'

Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral'

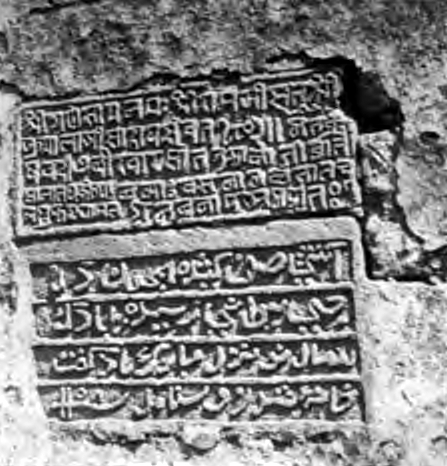

Samskrtam invocation to Lord Shiva in an Atashgah inscription, with the Hindu devotional-form of the Swastika on top

Samskrtam invocation to Lord Shiva in an Atashgah inscription, with the Hindu devotional-form of the Swastika on top

.png)

m0453 . Scarf as pigtail of seated person.Kneeling adorant and serpent on the field.

m0453 . Scarf as pigtail of seated person.Kneeling adorant and serpent on the field. Text on obverse of the tablet m453A: Text 1629. m453BC Seated in penance, the person is flanked on either side by a kneeling adorant, offering a pot and a hooded serpent rearing up.

Text on obverse of the tablet m453A: Text 1629. m453BC Seated in penance, the person is flanked on either side by a kneeling adorant, offering a pot and a hooded serpent rearing up.

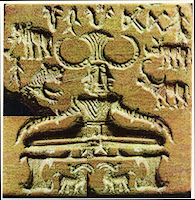

m1181. Seal. Mohenjo-daro. Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown), wearing bangles and armlets and seated on a hoofed platform.

m1181. Seal. Mohenjo-daro. Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown), wearing bangles and armlets and seated on a hoofed platform.

Karnonou (Cernunnos) on Pillarof Boatmen.Seated in penance. Wearing three strands as shawl.. tri-dhAtu 'three strands' rebus: tri-dhAtu 'three ferrite ores'. kamaDha 'penance' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. karNadhAra (kannahAra?) 'rings or torcs on antlers (ears?)' rebus: kannahAra 'helmsman' (Pali)

Karnonou (Cernunnos) on Pillarof Boatmen.Seated in penance. Wearing three strands as shawl.. tri-dhAtu 'three strands' rebus: tri-dhAtu 'three ferrite ores'. kamaDha 'penance' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. karNadhAra (kannahAra?) 'rings or torcs on antlers (ears?)' rebus: kannahAra 'helmsman' (Pali)

Hieroglyph components on the head-gear of the person on cylinder seal impression are: twig, crucible, buffalo horns: kuThI 'badari ziziphus jojoba' twig Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'; koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer'; tattAru 'buffalo horn' Rebus: ṭhã̄ṭhāro 'brassworker'.

Hieroglyph components on the head-gear of the person on cylinder seal impression are: twig, crucible, buffalo horns: kuThI 'badari ziziphus jojoba' twig Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'; koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer'; tattAru 'buffalo horn' Rebus: ṭhã̄ṭhāro 'brassworker'.

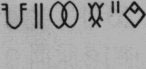

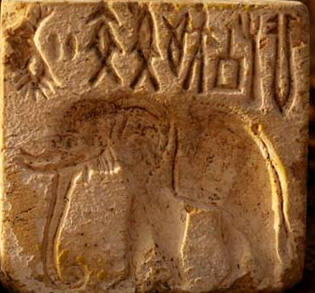

Inscription. Altyn Depe seal.

Inscription. Altyn Depe seal.

Bhadre

Bhadre

Dong Son Bronze Drum with Indus Script hieroglyphs.

Dong Son Bronze Drum with Indus Script hieroglyphs.