Gruppen, bestehend aus Sprachen, die eine große Ähnlichkeit in syntaktischer Hinsicht;

eine Ähnlichkeit in den Grundsätzen des morphologischen Baues aufweisen; und eine

große Anzahl gemeinsamer Kulturwörter bieten, manchmal auch äussere Ähnlichkeit

im Bestande der Lautsystem, — dabei aber keine systematischen Lautentsprechungen keine Übereinstimmung in der lautlichen Gestalt der morphologischen Elemente, und

keine gemeinsamen Elementarwörter besitzen, — solche Sprachgruppen nennen wir

Sprachbünde. [Trubetzkoy, 1928: 18 (italics his)]Trubetzkoy, N. S., 1928. Proposition 16. In: Actes du 1er Congrès international de linguistes, 17-18.Leiden: A. W. Sijthoff’s Uitgeversmaatschappij.

A study of what is defined as Indian Linguistic Area by Murray B. Emeneau can begin with the co-author of Dravidian Etymological Dictionary T. Burrow, who wrote the following embedded article on the Proto-Indoaryans in JRAS (April 1973). A number of linguists have also endorsed the reality of Indian Linguistic Area. The question to be explored is: what was the date of the genesis of this area?

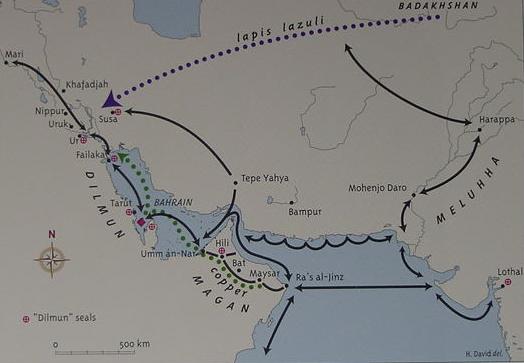

I suggest that the genesis can be traced to the Indus-Sarasvati civilization which is evidenced archaeologically, from ca. 3500 BCE.

An Indian Lexicon is provided in the embedded document below including comparative glosses from Indo-Aryan, Dravidian and Munda streams.

This lexicon clusters together, semantically, lexemes from over 25 Indian languages with surface resemblances (äussere Ähnlichkeit) in the sound system.

This lexicon demonstrates a large amount of shared cultural vocabulary in the three streams.

The field of inquiry is to delineate how this sharing occurred. In some semantic clusters of the lexicon, a hypothesized common substrate may explain the surface resemblances in the sound system.

One possibility is that the three streams descend from a community which lived and worked together in a transition from chalcolithic age to bronze age.

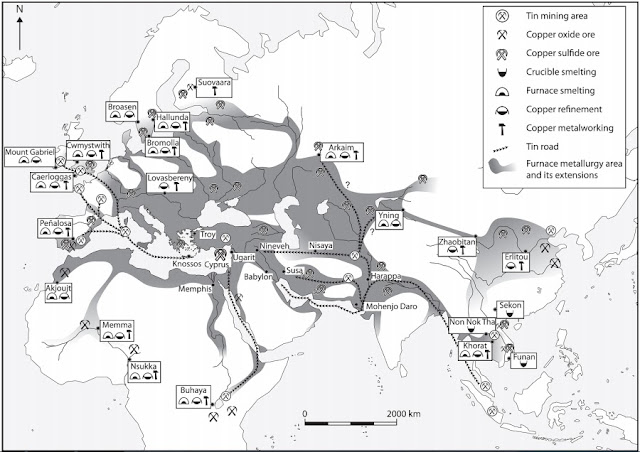

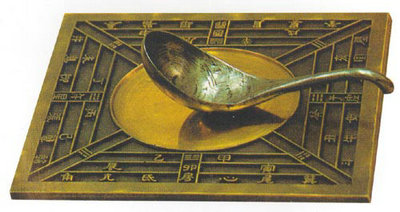

Substratum words Indian sprachbund could be culled from the Bronze Age social experience recorded i the data archives of Indus Script Corpora and hypothesised to constitute lexemes of 'Indus language' of the Bronze Age. The 4th millennium BCE heralded the arrival of a veritable revolution in technology -- the making of tin bronzes to complement arsenical bronzes. Contemporaneous with this metallurgical revolution was the invention of writing systems which evolved from early tokens and bullae to categorise commodities and provide for their accounting systems using advanced tokens with writing as administrative devices.

Remarkable progress has been made ever since Kuiper identified a stunning array of glosses which were found in early Samskrtam and which were not explained by Indo-Aryan or Indo-European language evolution chronologies. On Munda lexemes in Sanskrit see: [F.B.J. Kuiper, Proto-Munda Words in Sanskrit, Amsterdam, Verhandeling der Koninklijke Nederlandsche Akademie Van Wetenschappen, Afd. Letterkunde, Nieuwe Reeks Deel Li, No. 3, 1948] http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/sarasvati/dictionary/9MUNDA.HTM Kuiper's brilliant exposition begins: "Some hundred Sanskrit and Prakrit words are shown to be derived from the Proto-Munda branch of the Austro-Asiatic source. The term 'Proto-Munda' is used to indicate that the Munda languages had departed considerably from the Austro-Asiatic type of language as early as the Vedic period... a process of 'Dravidization' of the Munda tongues... contributing to the growth of the Indian linguistic league (sprachbund)."

కండె [ kaṇḍe ] kaṇḍe. [Tel.] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. జొన్నకంకి. Mth. kã̄ṛ ʻstack of stalks of large milletʼ(CDIAL 3023). Rebus: kaṇḍ‘ furnace, fire-altar, consecrated fire’. Rebus: khāṇḍā‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. By shaping the tablets in fish-shapes, the intent is to convey the definitive message that the khāṇḍā 'implements' are made of metal (ayo 'fish' rebus: ayas 'metal')

![]() h337, h338 Texts 4417, 4426 with two glyphs each on leaf-shaped, miniature Harappa tablets.

h337, h338 Texts 4417, 4426 with two glyphs each on leaf-shaped, miniature Harappa tablets.A miniature, incised tablet from Harappa h329A has a fish-shaped tablet with two signs: fish + arrow (which combination was also pronounced as ayaskāṇḍa on a bos indicus seal Kalibangan032).

![]() The 'dotted circle' hieroglyph signifying the fish-eye may be dhA 'strand' rebus: dhAu 'mineral'.

The 'dotted circle' hieroglyph signifying the fish-eye may be dhA 'strand' rebus: dhAu 'mineral'.

Combination of ‘fish’ glyph and ‘four-short-linear-strokes’ circumgraph also pronounced the same text ayaskāṇḍa on another bos indicus seal m1118. This seal uses circumgraph of four short linear strokes which included a morpheme which was pronounced variantly as gaṇḍa ‘four’ (Santali).

Thus, the circumgraph of four linear strokes used on m1118 Mohenjo-daro seal was an allograph for ‘arrow’ glyph used on h329A Harappa tablet. poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' See: bolad 'steel' (Russian) folad 'steel' (Old Persian).

The dotted circle denotes: khaṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’.

Evidence for Meluhha as a language comes from Mahabharata and also from Shu-ilishu cylinder seal signifying him as a Meluhha translator (in cuneiform text).

Vatsyayana attests mlecchitavikalpa as a cipher, one of the 64 arts to be learnt together with deśabhāṣā jnānam and akṣaramuṣṭika kathanam. Patanjali elaborates on mleccha as a dialect. There is a lot of textual data on people as distinct from language -- both mleccha and ārya as dasyu (cf. OIr. daha) and as dwīpavāsinah.

One intriguing semantic may be cited, again, in the context of the bronze-age. There are two compounds: milakkhu rajanam 'copper-coloured'

(Pali), mleccha mukha 'copper' (Samskrtam)

Why mleccha mukha? I think the lexeme mukha isa substrate lexeme mūh 'face, ingot' (Munda. Santali etc.); it is possible that mleccha mukha may

refer to 'copper ingot'. mũhã = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace (Santali) Mleccha, language. Mleccha, copper. The other meaning of mūh 'face' (CDIAL 10158) explains why a face glyph

gets ligatured in Indus writing to clear composite hieroglyphs to create mlecchitavikalpa (cipher mentioned by Vātsyāyana) .

A reference to mleccha as language, bhāṣā, occurs in Bharata's Nāṭyaśāstra:

XVIII. 80 ] RULES ON THE USE OF LANGUAGES 827 The Common Language

28. The Common Language prescribed for use [on the stage] has various forms 1 . It contains [many] words of Barbarian {mleccha) origin and is spoken in Bharata-varsa [only] Note: 28 (C.26b-27a; B.XVII.29b-30a). 'Read vividha-jatibhasa ; vividha (ca, da in B.) for dvividha.

'The common speech or the speech of the commoners is distinguished here from that of the priests and the nobility by describing it as containing words of Barbarian (mleccha) origin. These words seem to have been none other than vocables of the Dravidian and Austric languages. They entered Indo-Aryan pretty early in its history. See S. K. Chatterji, Origin and Development of the Bengali Language, Calcutta, 1926 pp. 42,178.'

Source: Natya Shastra of Bharata Muni in english THE NATYASASTRA A Treatise on Hindu Dramaturgy and Histrionics Ascribed to B H A R A T A - M r X I Vol. I. ( Chapters I-XXVII ) Completely translated jor the jirst tune from the original Sanskrit tuttri «u Introduction and Various Notes, Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta http://archive.org/stream/NatyaShastraOfBharataMuniVolume1/NatyaShastraOfBharataMuniVolume1_djvu.txt

Ancient Near East evidence for mleccha (meluhha) language from ancient texts (Update: June 14, 2013)

A personal cylinder seal of Shu-ilishu, a translator of the Meluhhan language (Expedition 48 (1): 42-43) with cuneiform writing exists. The rollout of Shu-ilishu’s cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Département des Antiquités Orientales, Musée du Louvre, Paris. "The presence in Akkad of a translator of the Meluhhan language suggests that he may have been literate and could read the undeciphered Indus script. This in turn suggests that there may be bilingual Akkadian/Meluhhan tablets somewhere in Mesopotamia. Although such documents may not exist, Shu-ilishu's cylinder seal offers a glimmer of hope for the future in unraveling the mystery of the Indus script." (Gregory L. Possehl,Shu-ilishu's cylinder seal, Expedition, Vol. 48, Number 1, pp. 42-43).http://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/48-1/What%20in%20the%20World.pdf

[quote] The suggestion that ‘fish-eyes’ (IGI.HA, IGI-KU6), imported through Ur, may have been pearls has been advanced by a number of scholars. ‘Fish-eyes’ were among a number of valuable commodities (gold, copper, lapis lazuli, stone beads) offered in thanksgiving at the temple of the Sumerian goddess Ningal at Ur by seafaring merchants who had returned safely from Dilmun and perhaps further afield. Elsewhere they are said to have been bought in Dilmun. Whether ‘fish-eyes’ differed from ‘fish-eye stones’ (NA4 IGI.HA, NA4 IGI-KU6) and from simply ‘eye-stones’ is not entirely clear. The latter are included among goods imported from Meluhha (NA4 IGI-ME-LUH-HA) ca. 1816-1810 BCE and ca. 1600-1570 BCE. Any pearls from Meluhha – probably coastal Baluchistan-Sind – would have been generally inferior to those from Dilmun itself. It has been strongly argued that ‘fish-eyes’, ‘fish-eye stones’ and ‘eye-stones’ in Old Babylonian and Akkadian texts were not in fact pearls, but rather (a) etched cornelian beads, imported from India and/or (b) pebbles of banded agate, cut to resemble closely a black/brown pupil and white cornea. The nearest source of good agate is in northwest India, which would accord with supplies obtained from Meluhha. ‘Eye-stones’ of agate were undoubtedly treasured: some were inscribed and used as amulets, others have been found in votive deposits. Perhaps pearls were at times included among ‘fish-eyes,’ if not ‘fish-eye stones’. More likely, however, the word for ‘pearl’ is among the ‘more than 800 terms in the lexical lists of stones and gems [that] remain to be identified.[unquote] (Donkin, R.A., 1998, Beyond price: pearls and pearl-fishing: origins to the age of discoveries, Philadelphia, American Philosophical Society, Memoir Volume 224, pp.49-50)Full text at http://tinyurl.com/y9zpb5n Note 109. For Sumerian words, see Delitzch, 1914: pp.18-19 (igi, eye), 125 (ku, fish), 195 (na, stone); and cf. Chicago Assyrian Dictionary I/J: 1960: pp.45 (iga), 153-158 (Akk. i_nu), N(2), 1980: p.340 (k), ‘fish-eye stones’.Note 110. A.L. Oppenheim, 1954: pp.7-8; Leemans, 1960b: pp.24 f. (IGI-KU6). Followed by Kramer, 1963a: p.113, 1963b: p.283; Bibby, 1970: pp.189, 191-192: Ratnagar, 1981: pp.23-24,79, 188; M. Rice, 1985: p.181.Note 111. A.L. Oppenheim, 1954: p.11; Leemans, 1960b: p.37 (NA4 IGI-KU6, ‘fish-eye stones’).Note 112. Leemans, 1968: p.222 (‘pearls from Meluhha’. Falkenstein (1963: pp.10-11 [12]) has ‘augenformigen Perlen aus Meluhha’.(lit. shaped eyes beads from Meluhha).

![]()

kalibangan 059a shows structural groups of numeral strokes, together with a ‘bow’ glyph.

Mint, workshop (for) native metal, furnace, smithy.

kamāt.hiyo = archer; kāmaṭhum = a bow; ka_mad.i_, ka_mad.um = a chip of bamboo (G.) ka_maṭhiyo a bowman; an archer (Skt.lex.) Rebus: kammaṭa = portable furnace (Te.) kampaṭṭam coiner, mint (Ta.)

One short numeral stroke: sal stake, spike, splinter, thorn, difficulty (H.); rebus: sal ‘workshop’ (Santali)

One long numeral stroke with superscripte of two short strokes: kod.a = in arithmetic, one (Santali) Together with pairing sign Sign 99 : at.ar a splinter; at.aruka to burst, crack, slit off, fly open;at.arcca splitting, a crack; at.arttuka to split, tear off, open (an oyster)(Ma.); ad.aruni to crack (Tu.)(DEDR 66) Rebus: kod. ‘workshop’ (G.); aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.)

The numeral strokes should be read as: 3+2 (non-superscript). kolmo ‘three’; rebus: kolimi ‘forge’ (Te.); dol ‘pair’; rebus: dul ‘cast’ as in dul mer.ed ‘cast iron’ (Santali). Thus 3+2 are decoded as: forging, casting (smithy)] Vikalpa: pan~ca ‘five’ (Skt.) pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali).

Substrtum words are likely to have been retained in more than one language of the Indian sprachbund, irrespective of the language-family to which a particular language belongs. This is the justification for the identification, in comparative lexicons, of sememes with cognate lexemes from languages such as Gujarati, Marathi, Kannada, Santali, Munda or Toda or Kota. The underlying assumption is that the substratum words were absorbed into the particular languages either as borrowings or as morphemes subjected to phonetic changes over time. There is no linguistic technique available to 'date' a particular sememe and relate it to the technical processes which resulted in naming, for example, the metalware or furnaces/smelters used to create metals and cast the metals or alloys and forge them. It is remarkable, indeed, that hundreds of cognate lexemes have been retained in more than one language to facilitate rebus readings of hieroglyphs.

An example can be cited to elucidate the point made in this argument. The word attested in Rigveda is ayas, often interpreted as 'metal or bronze'. The cognate lexemes are ayo 'iron' (Gujarati. Santali) ayaskāṇḍa 'excellent quantity of iron' (Panini), kāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans of metalware' (Marathi). अयोगूः A blacksmith; Vāj.3.5. अयस् a. [इ-गतौ-असुन्] Going, moving; nimble. N. (-यः) 1 Iron (एति चलति अयस्कान्तसंनिकर्षं इति तथात्वम्; नायसोल्लिख्यते रत्नम् Śukra 4.169. अभितप्तमयो$पि मार्दवं भजते कैव कथा शरीरिषु R.8.43. -2 Steel. -3 Gold. -4 A metal in general. Ayaskāṇḍa 1 an iron-arrow. -2 excellent iron. -3 a large quantity of iron. –क_नत_(अयसक_नत_) 1 ‘beloved of iron’, a magnet, load-stone; 2 a precious stone; ˚मजण_ a loadstone; ayaskāra 1 an iron-smith, blacksmith (Skt.Apte) ayas-kāntamu. [Skt.] n. The load-stone, a magnet. Ayaskāruḍu. n. A black smith, one who works in iron. ayassu. N. ayō-mayamu. [Skt.] adj. made of iron (Te.) áyas— n. ‘metal, iron’ RV. Pa. ayō nom. Sg. N. and m., aya— n. ‘iron’, Pk. Aya— n., Si. Ya. AYAŚCŪRṆA—, AYASKĀṆḌA—, *AYASKŪṬA—. Addenda: áyas—: Md. Da ‘iron’, dafat ‘piece of iron’. ayaskāṇḍa— m.n. ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ Pāṇ. Gaṇ. Viii.3.48 [ÁYAS—, KAA ́ṆḌA—]Si.yakaḍa ‘iron’.*ayaskūṭa— ‘iron hammer’. [ÁYAS—, KUU ́ṬA—1] Pa. ayōkūṭa—, ayak m.; Si. Yakuḷa‘sledge —hammer’, yavuḷa (< ayōkūṭa) (CDIAL 590, 591, 592). Cf. Lat. Aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. Ais , Thema aisa; Old Germ. E7r , iron ;Goth. Eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen. aduru native metal (Ka.); ayil iron (Ta.) ayir, ayiram any ore (Ma.); ajirda karba very hard iron (Tu.)(DEDR 192). Ta. Ayil javelin, lance, surgical knife, lancet.Ma. ayil javelin, lance; ayiri surgical knife, lancet. (DEDR 193). Aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330); adar = fine sand (Ta.); ayir – iron dust, any ore (Ma.) Kur. Adar the waste of pounded rice, broken grains, etc. Malt. Adru broken grain (DEDR 134). Ma. Aśu thin, slender;ayir, ayiram iron dust.Ta. ayir subtlety, fineness, fine sand, candied sugar; ? atar fine sand, dust. அய.ர³ ayir, n. 1. Subtlety, fineness; நணசம. (த_வ_.) 2. [M. ayir.] Fine sand; நணமணல. (மலசலப. 92.) ayiram, n. Candied sugar; ayil, n. cf. ayas. 1. Iron; 2. Surgical knife, lancet; Javelin, lance; ayilavaṉ, Skanda, as bearing a javelin (DEDR 341).Tu. gadarů a lump (DEDR 1196) kadara— m. ‘iron goad for guiding an elephant’ lex. (CDIAL 2711).

The rebus reading is provided by the fish hieroglyph which reads in Munda languages:

<ayu?>(A) {N} ``^fish’’. #1370. <yO>\\<AyO>(L) {N} ``^fish’’. #3612. <kukkulEyO>,,<kukkuli-yO>(LMD) {N} ``prawn’’. !Serango dialect. #32612. <sArjAjyO>,,<sArjAj>(D) {N} ``prawn’’. #32622. <magur-yO>(ZL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish’’. *Or.<>. #32632. <ur+Gol-Da-yO>(LL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish’’. #32642.<bal.bal-yO>(DL) {N} ``smoked fish’’. #15163. Vikalpa: Munda: <aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree’’.#10171. So<aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree’’. Indian mackerel Ta. Ayirai, acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitis thermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma. Ayala a fish, mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind of small fish, loach (DEDR 191)

A beginning has been made presenting over 8000 semantic clusters of Indo-Aryan, Dravidian and Munda words in a comparative Indian Lexicon.

After compiling the Dravidian Etymological Dictionary with Burrow, and descriptions of Toda, Badaga, Kolami, and Kota languages, MB Emeneau made this observation in Annamalai University(India and historical grammar : lecture on diffusion and evolution in comparative linguistics, and lecture on India and the linguistic areas, delivered as special lectures at the Linguistics Dept. of the Annamalai University in 1959). See: India as a Lingustic Area M. B. Emeneau Language Vol. 32, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1956), pp. 3-16

Root / lemma: du̯ō(u) (*du̯ei-)

English meaning: two

German meaning: `zwei'

Grammatical information: m. (grammatical double form duu̯ōu), du̯ai f. n., besides du̯ei-, du̯oi-, du̯i-

…from Adv. z.B. duví-dhā, dvē-dhā (probably*dvai̯i-dhā, that to be read in the oldest texts 3-syllable) `twofold, in two parts', wherewith the ending from air. dēde`duality of things' seems to be connected, as well as the from and. twēdi `halb', ags. twǣde `two thirds', ahd. zwitaran`hybrid, mongrel, half breed', nhd. Zwitter. Gr. δίχα `twofold, divided in two parts' (after hom. διχῇ, διχοῦ), next to which (through hybridization with *δι-θά to Old Indian dvídhā) hom. διχθά `δίχα', therefrom ion. διξός `twofold' (*διχθι̯ός or *δικσός), and δισσός, att. διττός ds. (*διχι̯ός, Schwyzer Gr. Gr. I 598, 840); about hitt. dak-ša-an `Halbteil' s. Pedersen Hitt. 141.

Root / lemma: gan(dh)-

English meaning: vessel

German meaning: `Geföß'ö

Note: Only kelt. (ö) and germ.

Material: Mir. gann (*gandhn- or *gandh-) `vessel' (very doubtful covered: Stokes BB. 19, 82);

isl. kani `vessel with a handle, bowl (poet.), norw. dial. kane `a bowl with a handle', schwed. dial. kana `sled', dön. kane`sled' (older dön. also `boat'), mnd. kane `boat' (from which aschwed. kani `boat'), ndl. kaan `small boat, barge' (from dem Ndd. derives also nhd. Kahn, s. Kluge EWb. s. v., v. Bahder, Wortwahl 30); with it changing through ablaut aisl. kǣna`kind of boat'; in addition further(< *gandhnā) anord. kanna, aschw. kanna, dön. kande, ags. canne, and. kanna, ahd.channa `carafe, glass bottle, jar, pitcher, vase', from which is borrowed late lat. canna; from frönk. kanna also prov. cana`measure of capacity', afr. channe `carafe, glass bottle, jar, pitcher, vase', s. Meyer-Löbke 1596, Gamillscheg EWb. d. Franz. 168; besides ahd. chanta, canneta, frönk. cannada `carafe, glass bottle, jar, pitcher, vase' (< gandhā).

Maybe alb. kanë `carafe, glass bottle, jar, pitcher, vase'.

References: WP. I 535, WH. I 154.

Page(s): 351

Root / lemma: nāus-1

English meaning: boat

German meaning: `Schiff' (ausgehöhlter Einbaum)

Grammatical information: f. Akk. nāu̯m̥

Material: Old Indian nāu- (Nom. nā́uḥ) `ship, boat' (nāvya- `schiffbar'); ap. nāviyā `fleet' (: gr. νήιος `zumSchiff gehörig'); nāvāja- m. `Schiffer', av. navāza- ds (: gr. ναυ-ηγός ds., compare also lat.nāvig-āre, -ium); av. nāvaya-`schiffbar' (about Old Indian ati-nu s. Brugrnann II1 137 Anm. 2); arm. nav `ship' (from dem Pers.ö); gr. hom. νηῦς, νηός (*νᾱFός), att. ναῦς, νεώς `ship'; lat. nāvis ds. (originally conservative stem, compare Akk. nāvem = Old Indian nā́vam, gr. νῆα; air. náu (Gen. nōë, Dat. Pl. nōib) `ship'; cymr. noe `flaches vessel, kneading or dough trough; dough tray; hutch', bret. neo ds. (*nāu̯i̯ā); here gall. (vorrom.) nāvā `Talschlucht', also FlN; gall. nausum `ship'; aisl. nōr m. `ship', nau-st`Schiffsschuppen', nōa-tūn (nōa = gr. νηῶν) `Schiffsburg', ags. nōwend `Schiffer', (but mhd.nāwe, næwe `small ship', nhd. dial. Naue from dem Lat.); norw. nō `trough from a ausgehöhlten tree truck', nøla (*nōwilōn-) `großer trough, schweres boat' ahd. nuosc, mhd. nuosch m. `trough, gully', afries. nōst `trough', mnd. nōste `Viehtrog, Wassertrog'; here the lit. FlN Nóva, polonis. Nawa.

Maybe alb. *nāviyā, anija ‘ship’

References: WP. II 315, WH. II 148 f., J. Hubschmid R. int. d'Onom. 4, 3 ff.

Page(s): 755-756

Root / lemma: reudh-

English meaning: red

German meaning: `rot'

Material: Old Indian rṓhita- = av. raoiδita- `red, reddish', rōhít- `rote mare, Weibchen a gazelle', rṓhi- m., rōhī f. `gazelle'; Old Indian lōhá- `reddish', m. n. `rötliches metal, copper, iron' (formal = lat. rūfus, air. rūad, got. rauÞs, lit.raũdas, Old Church Slavic rudъ), rōdhra-, lōdhra- m. `symplocosracemosa, ein tree, from dessen Rinde ein rotes Pulver bereitet wird', loṣṭa- n. `Eisenrost' (*reudh-s-to-); rudhirá- `red, blutig', n. `blood' (*rudhḫiḫro-, contaminated from*rudh-ro- and*rudh-i-); khotansak. rrusta- `red' (*reudh-s-to-);

gr. ἐρεύθω `I röte' (= aisl. rjōða), ἔρευθος n. `Röte' (compare lat. rubor); ἐρυθρός `red' (= lat. ruber, Old Church Slavic*rъdrъ etc.); ἐρυσί̄βη `Mehltau, robīgo' (ambiguous ending), ἐρυσί-πελας `Röteln' (*ἐρυσσι-, *rudh-s-);

lat. rūbidus `oxblood, indigo' (with -do- further formations = Old Indian lōhá-);

with dial. f: rūfus `lichtrot, fuchsrot', umbr. rofu `rubros'; with dial. ō from *ou lat. rōbus, rōbeus, rōbius `red', rōbīgo`Rost; Mehltau, Getreidebrand', also probably rōbus, rōbur `Hartholz, heartwood'; ruber, rubra, -um `red' (umbr. rufru`rubros'), lat. rubor `Röte', rubeō, -ēre `red sein' (: ahd. rotēn, Old Church Slavic rъděti), russus `fleischrot' (*rudh-so-); auf *rudhro- go die auson. Lw. rutilus `reddish', VN Rutuli (with Dissim.) back; compare lig. fundus Roudelius, illyr.Campī Raudii, apul. PN Rudiae (Szemerényi Arch. Ling. 4, 112 f.); about lat. raudus see under;

air. rūad, cymr. etc. rhudd `red', air. rucc(a)e `Schande' (*rud-ki̯ā), nasal. fo-roind `rötet'; gall. PN Roudus, Ande-roudus, GN Rudiobos (`roter Schlöger'ö), Rudianos; kelt. roudo- `red' and `strong';

aisl. rjōðr, ags. rēod `red', aisl. rjōða `blutig make', ags. rēodan `red förben', got. (about `shamefaced blush') ga-riuÞs`ehrbar', ga-riudei `Schamhaftigkeit'; ablaut. rauÞs, aisl. rauðr, ags. rēad, ahd. rōt `red', aisl. rauði m. `rotes Eisenerz',roðra f. `blood', roði m. `Röte', ryð n. and ryðr m. `Rost', roða `red sein or become', ahd. rotēn `blush', mhd. rot `red', ahd. rotamo, rosamo (*rudh-s-men-) `Röte' (moreover aisl. rosmu-fjǫll `rötliche Berge'), ags. rudu `Röte', rudig`reddish'; ā-ryderian `blush'; ags. rūst, ahd. as. rost `Rost' (*rū̆dh-s-to);

lit. raũdas, raudónas `red', raudà `rote paint, color'; rùdas `puce' (lett. ruds `reddish'), ruduõ `autumn', rudė́ti `rosten',rūdìs f. `Rost', rūdýnas, rūdynà, rūdỹnė `swamp, marsh with rötlichem, eisenhaltigem water, morass, puddle, slop',raũsvas (*roudh-s-u̯o-) `reddish', lett. rûsa (*rūdh-s-ā) `Rost', lit. rùsvas `reddish brown' (*rudh-s-u̯o-), ruslis`Bratrost', rusė́ti `gleam, burn', lett. rusla `kind of rotbrauner paint, color', lit. rùstas `bröunlich, purple, mauve' (*rudhḫsḫto-), lett. rusta `braune paint, color', rustēt `red förben';

Old Church Slavic rudъ `red', ruda `Erz, metal', rusъ (*roudh-s-o-) `reddish, blond'; *rъdrъ `red' in r.-Church Slavicrodrъ; rъděti sę `sich röten', rьžda `Rost', russ. rysyj `reddish blond' (*rūdh-s-o-, compare lett. rūsa);

toch. A rötr-ārkyant `rotglönzend', rtör, В rötre `red' (*rutre-ö).

Old Indian ravi- m. `sun', arm. arev ds. kann only very doubtful as `the Rote' gedeutet become; lat. raudus, rōdus, rūdus`ein formloses Erzstöck as Mönze' is perhaps with Old Indian lōhá- `rotes metal, copper, iron' and aisl. rauði `rotes Eisenerz', Old Church Slavic ruda `Erz, metal' to connect and gall. or illyr. Lw.;

maybe alb. rrotull `wheel, sunö' [diminutive -l]

also ahd. aruzzi, erizzi, aruz, as. arut `Erz, Erzstöck', aisl. ortog (*arutia-taugo) `Drittel eines øre' are because of Schwankens the forms as borrowed to betrachten; hence bestehtHommels derivation from sum. urud `copper' letztlich to right, different Kretschmer Gl. 32, 6 ff.

References: WP. II 358 f., WH. II 420 f., 444 f., 455, 456, Trautmann 239.

Page(s): 872-873

Root / lemma: ai̯os-

English meaning: `metal (copper; iron)'

German meaning: `Metall', under zw. probably `Kupfer ('brandfarbig'?), Bronze'; im Arischen also `Eisen'

Note:

Root / lemma: ai̯os- : `metal (copper; iron)' derived from Root / lemma: eis-1 : `to move rapidly, *weapon, iron'.

Material:

Old Indian áyas- n., av. ayaŋh- n. `metal, iron';

lat. aes, g. aeris; got. aiz (proto germ. *a(i̯)iz- = idg. *ai̯es-) `copper ore, and the alloy of copper, bronze. Transf., anything made of bronze; a vessel, statue, trumpet, kettle', ahd. ēr `ore', anord. eir n. `ore, copper'.

thereof av. ayaŋhaēna- `metallic, iron', lat. aēnus (*ai̯es-no- = umbr. ahesnes `of copper, of bronze'), aēneus, ags. ǣren, as. ahd. mhd. ērīn, nhd. ēren (ehern). despite Pokorny KZ. 46, 292 f. is not idg. ai̯os old borrowing from Ajasja, olderAɫas(ja), the old name of Cyprus, as lat. cuprum : Κύπρος, there according to D. Davis (BSA. 30, 74-86, 1932) the copper pits were tackled in Cyprus only in late Mycenaean time.

Note:

Ajasja, older Aɫas(ja) (Cyprus) : Hittite PN Wilusa (gr. reading Ilios) [common phonetic mutation of the old laryngeal ḫ- > a-, i-] : gall. Isarno- PN, ven. FlN'I σάρας, later Īsarcus, nhd. Eisack (Tirol); urir. PN I(s)aros, air. Īär, balkanillyr. iser, messap. isareti (Krahe IF. 46, 184 f.); kelt. FlN Isarā, nhd. Isar, Iser, frz. Isère; *Isiā, frz. Oise; *Isurā, engl. Ure, etc. (Pokorny Urillyrier 114 f., 161); nhd. FlN Ill, Illach, Iller, lett. FlN Isline, Islīcis, wruss. Isɫa, alb. VN Illyrii.

Here lat. aestimō, old aestumō `to appraise, rate, estimate the value of; to assess the damages in a lawsuit; in a wider sense, to value a thing or person; hence, in gen., to judge', Denomin. from *ais-temos `he cuts the ore' (to temnō).

References: WP. I 4, WH. I, 19, 20, Feist 31.

Anord. vāđ f. `fabric, piece, stuff, as comes ready of the loom, drag net', Pl.vāđir `gowns, clothes', ags. wǣd (*wēđi-) f. `clothes, rope', as. wād `clothes', ahd. wāt, Gen.-i `clothes, armament';anord. vađr m. `rope, string, fishing line', schwed. norw. vad n. `drag net' (anord. vǫzt f. `spot for fishing at sea from*wađa-stō), mhd. wate, wade f. `drag net, trawl net', mhd. spinne-wet `spinning web'.References: WP. I 16 f., WH. I 88.

ahd. trā̆da `fringe' (nhd. Troddel), mhd. trōdel (for *trādel) `tassel, wood fiber';

trā̆da `fringe' (nhd. Troddel), mhd. trōdel (for *trādel) `tassel, wood fiber';

trint, trent`circular', trent m. `curvature, roundness, circular line', ags. trinde f. (or trinda m.) `round clump', mhd. trindel, trendel`ball, circle, wheel' under likewise

Indo-European Etymological Dictionary - Indogermanisches Etymologisches Woerterbuch (JPokorny)

Some examples from Indus Script Corpora may relate to these etyma compiled by Pokorny.

Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/nfm5pbc

meRed bica ‘iron stone ore’, lo ‘copper ore’

![]()

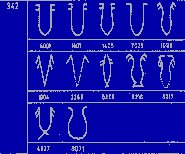

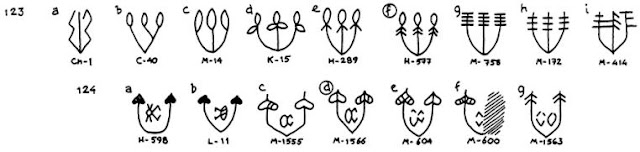

![]() V326 (Orthographic variants of Sign 326)

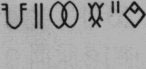

V326 (Orthographic variants of Sign 326) ![]() V327 (Orthographic variants of Sign 327)

V327 (Orthographic variants of Sign 327)Sign 51 Variants. It is seen from all these variants, that the semantic focus signified by the orthography is on the 'scorpion's pointed stinger'

These are two glyphs of the script with unique superscripted ligatures; this pair of ligatures does not occur on any other ligatured glyph in the entire corpus of Indus script inscriptions. Orthographically, Sign 51 glyph is a ‘scorpion’; Sign 327 glyph is a ‘ficus glomerata leaf’. The glosses for the ‘sound values’ are, respectively: bica ‘scorpion’ (Santali), lo ‘ficus’ (Santali).

Dravidian proof of Indus Script has been refuted. See link: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/a-four-hieroglyph-multiplex-of.html This note provides additional evidence to support this refutation by providing decipherment of inscriptions which are signified by the 'scorpion''fish' or 'ficus' hieroglyphs of Indus Script. The context of life-activity of the artisans is work in a mint, metalwork.

![]()

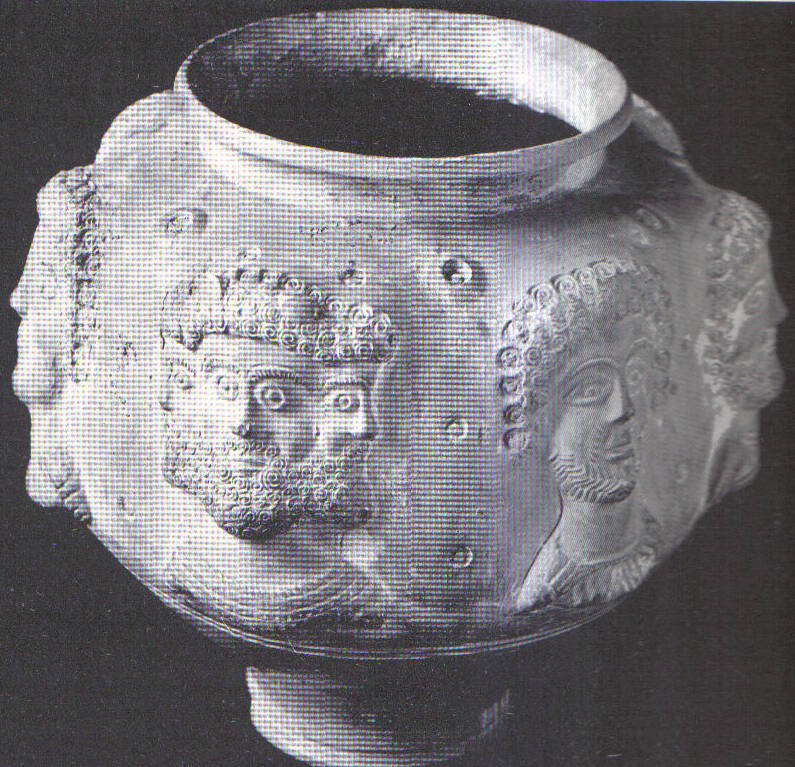

The inscription on the seal starts with 'scorpion' hieroglyph on modern impression of seal M-414 from Mohenjo-daro. After CISI 1:100. This sign is followed by a hieroglyph multiplex signifyinjg: rimledss pot PLUS ficus leaves PLUS infixed crab hieroglyphs. The terminal sign is 'fish' hieroglyph.

Rebus-metonymy readings in Meluhha cipher (mlecchita vikalpa) are of the three sets of hieroglyph multipexes: 1. meṛed-bica 'iron (hematite) stone ore' 2. bhaTa loh kammaṭa 'furnace copper mint, coiner' 3. aya 'alloy metal'.

Note: The 'ficus' hieroglyph is signified by two glosses: vaTa 'banyan' loa 'ficus glomerata'. Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' loha 'copper, iron'.![]()

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/a-four-hieroglyph-multiplex-of.html

On Mohenjo-daro seal m-414, the 'scorpion' sign is followed by a hieroglyph multiplex which is explained by Asko Parpola:

![]()

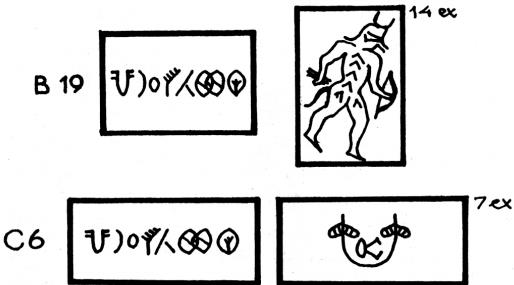

Parpola illustrates the 'crab' hieroglyhph with the following examples from copper plate inscriptions (Note: there are 240 copper plates with inscriptions from Mohenjo-daro):

Copper tablets from Mohenjo-daro providing a 'pictorial translation' of the Indus sign 'crab inside fig tree' (After Parpola 1994: 234, fig. 13.13)

Variants of 'crab' hieroglyph (After Parpola 1994: 232, cf. 71-72)

The hieroglyph-multiplex, thus orthographically signifies two ficus leaves ligatured to the top edge of a wide rimless pot and a crab hieroglyph is inscripted. In this hieroglyph-multiplex three hieroglyph components are signified: 1. rimless pot, 2. two ficus leaves, 3. crab. baTa 'rimless pot' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'; loa 'ficus' Rebus: loha 'copper, iron'; kamaDha 'crab' Rebus: kammaTa 'coiner, mint'.

Examples are:Modern impression of Harappa Seal h-598

![]() Modern impression of seal L-11 Lothal

Modern impression of seal L-11 Lothal

The third sign is a 'fish' hieroglyph.

(http://www.harappa.com/script/script-indus-parpola.pdf Asko Parpola, 2009k,'Hind leg' + 'fish': towards further understanding of the Indus Script, in: SCRIPTA, volume 1 (September 2009): 37-76, The Hummn Jeongeum Society)

Annex A: loa 'ficus glomerata' Rebus: loha 'copper, iron'

![]()

vaṭa1 m. ʻ the banyan Ficus indica ʼ MBh. Pa. vaṭa -- m. ʻ banyan ʼ, Pk. vaḍa -- , °aga -- m., K. war in war -- kulu m., S. baṛu m. (← E); P. vaṛ, baṛ m.,

vohṛ, bohṛ f. ʻ banyan ʼ, vaṛoṭā, ba° m. ʻ young banyan ʼ (+?); N. A. bar ʻ banyan ʼ, B. baṛ, Bi. bar (→ Or. bara), H. baṛ m. (→ Bhoj. Mth. baṛ), G. vaṛ m., M. vaḍ m., Ko. vaḍu. *vaṭapadra -- , *vaṭapātikā -- .Addenda: vaṭa -- 1: Garh. baṛ ʻ fig tree ʼ. 11215 *vaṭapātikā ʻ falling from banyan ʼ. [vaṭa -- 1, pāta -- ] G. vaṛvāī f. ʻ hanging root of banyan tree ʼ. (CDIAL 11211)

Allograph: vaṭa 'string': vaṭa2 ʻ string ʼ lex. [Prob. ← Drav. Tam. vaṭam, Kan. vaṭi, vaṭara, &c. DED 4268] N. bariyo ʻ cord, rope ʼ; Bi. barah ʻ rope working irrigation lever ʼ, barhā ʻ thick well -- rope ʼ, Mth. barahā ʻ rope ʼ.vaṭāraka -- , varāṭaka -- m. ʻ string ʼ MBh. [vaṭa -- 2]Pa. sa -- vaṭākara -- ʻ having a cable ʼ; Bi. baral -- rassī ʻ twisted string ʼ; H. barrā m. ʻ rope ʼ, barārā m. ʻ thong ʼ. (CDIAL 11212, 11217)

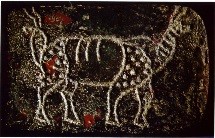

![]() lo 'nine', loa 'ficus religiosa' Rebus: loh 'copper'; kunda 'young bull' Rebus: kundār, kũdār 'turner'; firs hieroglph from r. on the text: eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'moltencast'; arA 'spoke' Rebus: Ara 'brass'; kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'.

lo 'nine', loa 'ficus religiosa' Rebus: loh 'copper'; kunda 'young bull' Rebus: kundār, kũdār 'turner'; firs hieroglph from r. on the text: eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'moltencast'; arA 'spoke' Rebus: Ara 'brass'; kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'.

lo = nine (Santali) [Note the count of nine fig leaves on m0296]

loa = a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata, the fruit of ficus glomerata (Santali.lex.)

loha lut.i = iron utensils and implements (Santali.lex.)

lauha = made of copper or iron (Gr.S’r.); metal, iron (Skt.); lo_haka_ra = coppersmith, ironsmith (Pali); lo_ha_ra = blacksmith (Pt.); lohal.a (Or.); lo_ha = metal, esp. copper or bronze (Pali); copper (VS.); loho, lo_ = metal, ore, iron (Si.)

Ficus glomerata: loa, kamat.ha = ficus glomerata (Santali); rebus: loha = iron, metal (Skt.) kamat.amu, kammat.amu = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.) kammat.i_d.u = a goldsmith, a silversmith (Te.) kampat.t.tam coinage coin (Ta.);kammat.t.am kammit.t.am coinage, mint (Ma.); kammat.a id.; kammat.i a coiner (Ka.)(DEDR 1236)

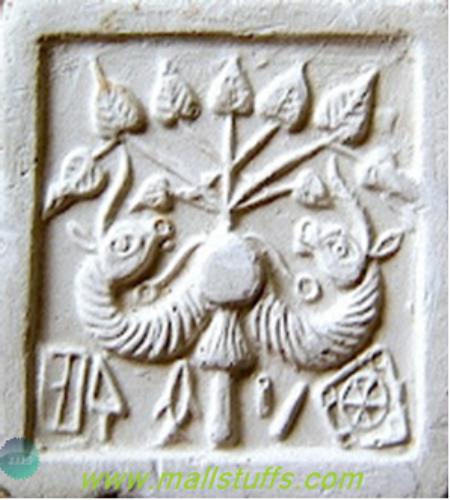

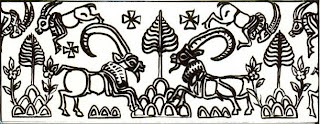

![]()

Sumerian cylinder seal showing flanking goats with hooves on tree and/or mountain. Uruk period. (After Joyce Burstein in: Katherine Anne Harper, Robert L. Brown, 2002, The roots of tantra, SUNY Press, p.100)Hence, two goats + mountain glyph reads rebus: meḍ kundār 'iron turner'. Leaf on mountain: kamaṛkom 'petiole of leaf'; rebus: kampaṭṭam 'mint'. loa = a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata, the fruit of ficus glomerata (Santali) Rebus: lo ‘iron’ (Assamese, Bengali); loa ‘iron’ (Gypsy). The glyphic composition is read rebus: meḍ loa kundār 'iron turner mint'. kundavum = manger, a hayrick (G.) Rebus: kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner's lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295) This rebus reading may explain the hayrick glyph shown on the sodagor 'merchant, trader' seal surrounded by four animals.Two antelopes are put next to the hayrick on the platform of the seal on which the horned person is seated. mlekh 'goat' (Br.); rebus: milakku 'copper' (Pali); mleccha 'copper' (Skt.) Thus, the composition of glyphs on the platform: pair of antelopes + pair of hayricks read rebus: milakku kundār 'copper turner'. Thus the seal is a framework of glyphic compositions to describe the repertoire of a brazier-mint, 'one who works in brass or makes brass articles' and 'a mint'.

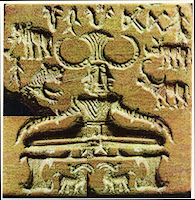

![Image result for mohenjo daro pashupati]()

Ta. meṭṭu mound, heap of earth; mēṭu height, eminence, hillock; muṭṭu rising ground, high ground, heap. Ma. mēṭu rising ground, hillock; māṭu hillock, raised ground; miṭṭāl rising ground, an alluvial bank; (Tiyya) maṭṭa hill. Ka. mēḍu height, rising ground, hillock; miṭṭu rising or high ground, hill; miṭṭe state of being high, rising ground, hill, mass, a large number; (Hav.) muṭṭe heap (as of straw). Tu. miṭṭè prominent, protruding; muṭṭe heap. Te. meṭṭa raised or high ground, hill; (K.) meṭṭu mound; miṭṭa high ground, hillock, mound; high, elevated, raised, projecting; (VPK) mēṭu, mēṭa, mēṭi stack of hay; (Inscr.) meṇṭa-cēnu dry field (cf. meṭṭu-nēla, meṭṭu-vari). Kol. (SR.) meṭṭā hill; (Kin.) meṭṭ, (Hislop) met mountain. Nk. meṭṭ hill, mountain. Ga. (S.3, LSB 20.3) meṭṭa high land. Go. (Tr. W. Ph.) maṭṭā, (Mu.) maṭṭa mountain; (M. L.) meṭā id., hill; (A. D. Ko.) meṭṭa, (Y. Ma. M.) meṭa hill; (SR.) meṭṭā hillock (Voc. 2949). Konḍa meṭa id. Kuwi (S.) metta hill; (Isr.) meṭa sand hill. (DEDR 5058) kamaṛkom = fig leaf (Santali.lex.) kamarmaṛā (Has.), kamaṛkom (Nag.); the petiole or stalk of a leaf (Mundari.lex.)Rebus: kampaṭṭam coinage, coin (Ta.)(DEDR 1236) kampaṭṭa- muḷai die, coining stamp (Ta.) Vikalpa: lo ‘iron’ (Assamese, Bengali); loa ‘iron’ (Gypsy)

Etyma from Indo-Aryan languages: lōhá 'copper, iron'

11158 lōhá ʻ red, copper -- coloured ʼ ŚrS., ʻ made of copper ʼ ŚBr., m.n. ʻ copper ʼ VS., ʻ iron ʼ MBh. [*rudh -- ] Pa. lōha -- m. ʻ metal, esp. copper or bronze ʼ; Pk. lōha -- m. ʻ iron ʼ, Gy. pal. li°, lihi, obl. elhás, as. loa JGLS new ser. ii 258; Wg. (Lumsden) "loa"ʻ steel ʼ; Kho. loh ʻ copper ʼ; S. lohu m. ʻ iron ʼ, L. lohā m., awāṇ. lōˋā, P. lohā m. (→ K.rām. ḍoḍ. lohā), WPah.bhad. lɔ̃u n., bhal. lòtilde; n., pāḍ. jaun. lōh, paṅ. luhā, cur. cam. lohā, Ku. luwā, N. lohu, °hā, A. lo, B. lo, no, Or. lohā, luhā, Mth. loh, Bhoj. lohā, Aw.lakh. lōh, H. loh, lohā m., G. M. loh n.; Si. loho, lō ʻ metal, ore, iron ʼ; Md. ratu -- lō ʻ copper ʼ. *lōhala -- , *lōhila -- , *lōhiṣṭha -- , lōhī -- , laúha -- ; lōhakāra -- , *lōhaghaṭa -- , *lōhaśālā -- , *lōhahaṭṭika -- , *lōhōpaskara -- ; vartalōha -- .Addenda: lōhá -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) lóɔ ʻ iron ʼ, J. lohā m., Garh. loho; Md. lō ʻ metal ʼ.†*lōhaphāla -- or †*lōhahala -- . lōhakāra 11159 lōhakāra m. ʻ iron -- worker ʼ, °rī -- f., °raka -- m. lex., lauhakāra -- m. Hit. [lōhá -- , kāra -- 1] Pa. lōhakāra -- m. ʻ coppersmith, ironsmith ʼ; Pk. lōhāra -- m. ʻ blacksmith ʼ, S. luhā̆ru m., L. lohār m., °rī f., awāṇ. luhār, P. WPah.khaś. bhal. luhār m., Ku. lwār, N. B. lohār, Or. lohaḷa, Bi.Bhoj. Aw.lakh. lohār, H. lohār, luh° m., G. lavār m., M. lohār m.; Si. lōvaru ʻ coppersmith ʼ. Addenda: lōhakāra -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) lhwāˋr m. ʻ blacksmith ʼ, lhwàri f. ʻ his wife ʼ, Garh. lwār m.

lōhaghaṭa 11160 *lōhaghaṭa ʻ iron pot ʼ. [lōhá -- , ghaṭa -- 1]

Bi. lohrā, °rī ʻ small iron pan ʼ. 11160a †*lōhaphāla -- ʻ ploughshare ʼ. [lōhá -- , phāˊla -- 1] WPah.kṭg. lhwāˋḷ m. ʻ ploughshare ʼ, J. lohāl m. ʻ an agricultural implement ʼ Him.I 197; -- or < †*lōhahala -- . lōhala 11161 lōhala ʻ made of iron ʼ W. [lōhá -- ] G. lohar, lohariyɔ m. ʻ selfwilled and unyielding man ʼ.

lōhaśālā 11162 *lōhaśālā ʻ smithy ʼ. [lōhá -- , śāˊlā -- ]

Bi. lohsārī ʻ smithy ʼ. lōhahaṭṭika 11163 *lōhahaṭṭika ʻ ironmonger ʼ. [lōhá -- , haṭṭa -- ] P.ludh. lōhṭiyā m. ʻ ironmonger ʼ. 11163a †*lōhahala -- ʻ ploughshare ʼ. [lōhá -- , halá -- ] WPah.kṭg. lhwāˋḷ m. ʻ ploughshare ʼ, J. lohāl ʻ an agricultural instrument ʼ; rather < †*lōhaphāla -- . lōhi 11164 lōhi ʻ *red, blood ʼ (n. ʻ a kind of borax ʼ lex.). [~ rṓhi -- . -- *rudh -- ] Kho. lei ʻ blood ʼ (BelvalkarVol 92 < *lōhika -- ), Kal.rumb. lū˘i, urt. lhɔ̈̄i. lṓhita 11165 lṓhita ʻ red ʼ AV., n. ʻ any red substance ʼ ŚBr., ʻ blood ʼ VS. [< rṓhita -- . -- *rudh -- ] Pa. lōhita -- in cmpds. ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻ blood ʼ, °aka -- ʻ red ʼ; Pk. lōhia -- ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻ blood ʼ; Gy. eur. lolo ʻ red ʼ, arm. nəxul ʻ blood, wound ʼ, pal. lúḥră ʻ red ʼ, inhīˊr ʻ blood ʼ, as. lur ʻ blood ʼ, lohri ʻ red ʼ Miklosich Mund viii 8; Ḍ. lōya ʻ red ʼ; Ash. leu ʻ blood ʼ, Wg. läi, Kt. lūi, Dm. lōi; Tir. ləwī, (Leech) luhī ʻ red ʼ, lọ̈̄i ʻ blood ʼ; Paš. lū f. ʻ blood ʼ, Shum. lúī, Gmb. lūi, Gaw. lō; Bshk. lōu ʻ red ʼ (AO xviii 241 < *lohuta -- ); S. lohū m. ʻ blood ʼ, L. lahū m., awāṇ. làū; P. lohī ʻ red ʼ, lohū, lahū m. ʻ blood ʼ; WPah.jaun. loī ʻ blood ʼ, Ku. loi, lwe, B. lau, Or. lohu, nohu, la(h)u, na(h)u, laa, Mth. lehū, OAw. lohū m., H. lohū, lahū, lehū m., G. lohī n.; OM.lohivā ʻ red ʼ Panse Jñān 536; Si. lehe, lē ʻ blood ʼ, le ʻ red ʼ SigGr ii 460; Md. lē ʻ blood ʼ. -- Sh. lēl m. ʻ blood ʼ, lōlyŭ ʻ red ʼ rather < *lōhila -- . lōhitaka -- . Addenda: lṓhita -- : Kho. lei ʻ blood ʼ BKhoT 70, WPah.kṭg. lóu m., Garh. loi, Md. lei, lē.

lōhitaka 11166 lōhitaka ʻ reddish ʼ Āpast., n. ʻ calx of brass, bell- metal ʼ lex. [lṓhita -- ] K. lŏy f. ʻ white copper, bell -- metal ʼ. lōhittara 11167 *lōhittara ʻ reddish ʼ. [Comp. of *lōhit -- ~ rōhít -- . - *rudh -- ] Woṭ. latúr ʻ red ʼ, Gaw. luturá: very doubtful (see úparakta -- ) lōhila 11168 *lōhila ʻ red ʼ. [lōhá -- ] Wg. lailäi -- štä ʻ red ʼ; Paš.chil. lēle -- šiṓl ʻ fox ʼ; Sv. lohĩló ʻ red ʼ, Phal. lohílu, ləhōilo; Sh.gil. jij. lēl m. ʻ blood ʼ, gil. lōlyŭ, (Lor.)loilo ʻ red, bay (of horse or cow) ʼ, pales. lēlo swã̄ṛə ʻ (red) gold ʼ. -- X nīˊla -- : Sh.gil. līlo ʻ violet ʼ, koh. līlṷ, pales. līˊlo ʻ red ʼ. -- Si. luhul, lūlā ʻ the dark -- coloured river fish Ophiocephalus striatus ʼ? -- Tor. lohūr, laūr, f. lihīr ʻ red ʼ < *lōhuṭa<-> AO xviii 241? lōhiṣṭha 11169 *lōhiṣṭha ʻ very red ʼ. [lōhá -- ] Kal.rumb. lohíṣṭ, urt. liūṣṭ ʻ male of Himalayan pheasant ʼ, Phal. lōwīṣṭ (f. šām s.v. śyāmá -- ); Bshk. lōīˊṭ ʻ id., golden oriole ʼ; Tor.lawēṭ ʻ male golden oriole ʼ, Sh.pales. lēṭh.

lōhī 11170 lōhī f. ʻ any object made of iron ʼ Kāv., ʻ pot ʼ Divyāv., lōhikā -- f. ʻ large shallow wooden bowl bound with iron ʼ,lauhā -- f. ʻ iron pot ʼ lex. [lōhá -- ]

Pk. lōhī -- f. ʻ iron pot ʼ; P. loh f. ʻ large baking iron ʼ; A. luhiyā ʻ iron pan ʼ; Bi. lohiyā ʻ iron or brass shallow pan with handles ʼ; G.lohiyũ n. ʻ frying pan ʼ.

lōhōpaskara 11171 *lōhōpaskara ʻ iron tools ʼ. [lōhá -- , upaskara -- 1]

N. lokhar ʻ bag in which a barber keeps his tools ʼ; H. lokhar m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; -- X lauhabhāṇḍa -- : Ku. lokhaṛ ʻ iron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻ tools, iron, ironware ʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ (LM 400 < -- khaṇḍa -- ). laúkika -- , laukyá -- see *lōkíya -- . laulāha 11172 laulāha m. ʻ name of a place ʼ Stein RājatTrans ii 487.

K. lōlav ʻ name of a Pargana and valley west of Wular Lake ʼ.

11172a laúha -- ʻ made of copper or iron ʼ Gr̥Śr., ʻ red ʼ MBh., n. ʻ iron, metal ʼ Bhaṭṭ. [lōhá -- ] Pk. lōha -- ʻ made of iron ʼ; L. lohā ʻ iron -- coloured, reddish ʼ; P. lohā ʻ reddish -- brown (of cattle) ʼ. lauhabhāṇḍa -- , *lauhāṅga -- .

lauhakāra -- see lōhakāra -- . Addenda: laúha -- [Dial. au ~ ō (in lōhá -- ) < IE. ou T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 74]

lauhabhāṇḍa 11173 lauhabhāṇḍa n. ʻ iron pot, iron mortar ʼ lex. [laúha -- , bhāṇḍa -- 1] Pa. lōhabhaṇḍa -- n. ʻ copper or brass ware ʼ; S. luhã̄ḍ̠iṛī f. ʻ iron pot ʼ, L.awāṇ. luhã̄ḍā; P. luhã̄ḍā, lohṇḍā, ludh. lō̃hḍā m. ʻ frying pan ʼ; N. luhũṛe ʻ iron cooking pot ʼ; A. lohorā ʻ iron pan ʼ; Bi. lohãṛā ʻ iron vessel for drawing water for irrigation ʼ; H. lohaṇḍā, luh° m. ʻ iron pot ʼ; G. loḍhũ n. ʻ iron, razor ʼ, pl. ʻ car<-> penter's tools ʼ, loḍhī f. ʻ iron pan ʼ. -- X *lōhōpaskara<-> q.v.

lauhāṅgika 11174 *lauhāṅgika ʻ iron -- bodied ʼ. [láuha -- , áṅga -- 1]

P. luhã̄gī f. ʻ staff set with iron rings ʼ, H. lohã̄gī f., M. lohã̄gī, lavh°, lohãgī f.; -- Bi. lohãgā, lahaũgā ʻ cobbler's iron pounder ʼ, Mth.lehõgā.

A variant orthography for sãghāṛɔ 'lathe' is displayed on m0296 Mohenjo-daro seal.

![]() m0296 See: https://sites.google.com/site/induswriting/epigraphs?pli=1 Decoding of a very remarkable set of glyphs and a 5-sign epigraph on a seal, m0296, together with a review of few other pictographs used in the writing system of Indus script. This seal virtually defines and prefaces the entire corpus of inscriptions of mleccha (cognate meluhha) artisans of smithy guild, caravan of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. The center-piece of the orthography is a stylized representation of a 'lathe' which normally is shown in front of a one-horned young bull on hundreds of seals of Indus Script Corpora. This stylized sãghāṛɔ 'lathe' is a layered rebus-metonymy to denote 'collection of implements': sangāṭh संगाठ् । सामग्री m. (sg. dat. sangāṭas संगाटस्), a collection (of implements, tools, materials, for any object), apparatus, furniture, a collection of the things wanted on a journey, luggage, and so on. This device of a stylized 'lathe' is ligatured with a circular grapheme enclosing 'protuberances' from which emanate a pair of 'chain-links'. These hieroglyphs are also read as rebus-metonymy layers to represent a specific form of lapidary or metalwork: goṭī 'lump of silver' (Gujarati); goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ(Kashmiri). Thus, a collection of hieroglyphs are deployed as rebus-metonymy layered encryptions, to convey a message in Meluhha (mleccha) speech form.

m0296 See: https://sites.google.com/site/induswriting/epigraphs?pli=1 Decoding of a very remarkable set of glyphs and a 5-sign epigraph on a seal, m0296, together with a review of few other pictographs used in the writing system of Indus script. This seal virtually defines and prefaces the entire corpus of inscriptions of mleccha (cognate meluhha) artisans of smithy guild, caravan of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. The center-piece of the orthography is a stylized representation of a 'lathe' which normally is shown in front of a one-horned young bull on hundreds of seals of Indus Script Corpora. This stylized sãghāṛɔ 'lathe' is a layered rebus-metonymy to denote 'collection of implements': sangāṭh संगाठ् । सामग्री m. (sg. dat. sangāṭas संगाटस्), a collection (of implements, tools, materials, for any object), apparatus, furniture, a collection of the things wanted on a journey, luggage, and so on. This device of a stylized 'lathe' is ligatured with a circular grapheme enclosing 'protuberances' from which emanate a pair of 'chain-links'. These hieroglyphs are also read as rebus-metonymy layers to represent a specific form of lapidary or metalwork: goṭī 'lump of silver' (Gujarati); goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ(Kashmiri). Thus, a collection of hieroglyphs are deployed as rebus-metonymy layered encryptions, to convey a message in Meluhha (mleccha) speech form.

Hieroglyph: gö̃ṭh 1 अर्गलम्, चिन्हितग्रन्थिः f. (sg. dat. gö̃ṭhi गाँ&above;ठि), a bolt, door-chain; a method of tying up a parcel with a special knot marked or sealed so that it cannot be opened by an unauthorized person. Cf. gã̄ṭh and gö̃ṭhü. -- dyunu -- m.inf. to knot, fasten; to bolt, fasten (a door) (K.Pr. 76). *gōṭṭa ʻ something round ʼ. [Cf. guḍá -- 1. -- In sense ʻ fruit, kernel ʼ cert. ← Drav., cf. Tam. koṭṭai ʻ nut, kernel ʼ, Kan. goṟaṭe &c. listed DED 1722] K. goṭh f., dat. °ṭi f. ʻ chequer or chess or dice board ʼ; S. g̠oṭu m. ʻ large ball of tobacco ready for hookah ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; P. goṭ f. ʻ spool on which gold or silver wire is wound, piece on a chequer board ʼ; N. goṭo ʻ piece ʼ, goṭi ʻ chess piece ʼ; A. goṭ ʻ a fruit, whole piece ʼ, °ṭā ʻ globular, solid ʼ, guṭi ʻ small ball, seed, kernel ʼ; B. goṭā ʻ seed, bean, whole ʼ; Or. goṭā ʻ whole, undivided ʼ, goṭi ʻ small ball, cocoon ʼ, goṭāli ʻ small round piece of chalk ʼ; Bi. goṭā ʻ seed ʼ; Mth. goṭa ʻ numerative particle ʼ; H.goṭ f. ʻ piece (at chess &c.) ʼ; G. goṭ m. ʻ cloud of smoke ʼ, °ṭɔ m. ʻ kernel of coconut, nosegay ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ lump of silver, clot of blood ʼ, °ṭilɔ m. ʻ hard ball of cloth ʼ; M. goṭām. ʻ roundish stone ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ a marble ʼ, goṭuḷā ʻ spherical ʼ; Si. guṭiya ʻ lump, ball ʼ; -- prob. also P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ, H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ. Rebus: °ṭī f. ʻ lump of silver*gōḍḍ -- ʻ dig ʼ see *khōdd -- .Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271).Rebus: goṭī f. ʻ lump of silver (Gujarati).

Hieroglyph: kaḍī a chain; a hook; a link (G.); kaḍum a bracelet, a ring (G.) Rebus: kaḍiyo [Hem. Des. kaḍaio = Skt. sthapati a mason] a bricklayer; a mason; kaḍiyaṇa, kaḍiyeṇa a woman of the bricklayer caste; a wife of a bricklayer (Gujarati)Why nine leaves? lo = nine (Santali); no = nine (Bengali) [Note the count of nine ‘ficus’ leaves depicted on the epigraph.]

lo, no ‘nine’ phonetic reinforcement of Hieroglyph: loa ‘ficus’ loa = a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata (Santali) Rebus: lo ‘copper’ (Samskritam) loha lut.i = iron utensils and implements (Santali) lauha = made of copper or iron (Gr.S’r.); metal, iron (Skt.); lo_haka_ra = coppersmith, ironsmith (Pali); lo_ha_ra = blacksmith (Pt.); lohal.a (Or.); lo_ha = metal, esp. copper or bronze (Pali); copper (VS.); loho, lo_ = metal, ore, iron (Si.)Interlocking bodies: ca_li (IL 3872); rebus: s’a_lika (IL) village of artisans. [cf. sala_yisu = joining of metal (Ka.)]

kamaḍha = ficus religiosa (Skt.); kamar.kom ‘ficus’ (Santali) rebus: kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.); kampaṭṭam = mint (Ta.) Vikalpa: Fig leaf ‘loa’; rebus: loh ‘(copper) metal’. loha-kāra ‘metalsmith’ (Sanskrit). loa ’fig leaf; Rebus: loh ‘(copper) metal’ The unique ligatures on the 'leaf' hieroglyph may be explained as a professional designation: loha-kāra 'metalsmith'; kāruvu [Skt.] n. 'An artist, artificer. An agent'.(Telugu).

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/10/indus-script-inscriptions-examples-of.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/some-select-meluhha-hieroglyphs.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com.es/2013/12/meluhha-hieroglyphs-of-assur-assur.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/01/multiplex-as-metaphor-ligatures-on.html

sãghāṛɔ 'lathe' is a signifier and the signified is: सं-घात sãghāta 'caravan consignment' [an assemblage, aggregate of metalwork objects (of the turner in workshop): metals, alloys]. sangāṭh संगाठ् । सामग्री m. (sg. dat. sangāṭas संगाटस्), a collection (of implements, tools, materials, for any object), apparatus, furniture, a collection of the things wanted on a journey, luggage, and so on. -- karun -- करुन् । सामग्रीसंग्रहः m.inf. to collect the ab. (L.V. 17).(Kashmiri).

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/03/emphatic-evidence-for-indus-script.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/vajra-sanghata-binding-together.html

Hieroglyph: one-horned young bull: खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. Rebus: कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi)

kot.iyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; kot. = neck (G.lex.) [cf. the orthography of rings on the neck of one-horned young bull]. ko_d.iya, ko_d.e = young bull; ko_d.elu = plump young bull; ko_d.e = a. male as in: ko_d.e du_d.a = bull calf; young, youthful (Te.lex.)

Glyph: ko_t.u = horns (Ta.) ko_r (obl. ko_t-, pl. ko_hk) horn of cattle or wild animals (Go.); ko_r (pl. ko_hk), ko_r.u (pl. ko_hku) horn (Go.); kogoo a horn (Go.); ko_ju (pl. ko_ska) horn, antler (Kui)(DEDR 2200). Homonyms: kohk (Go.), gopka_ = branches (Kui), kob = branch (Ko.) gorka, gohka spear (Go.) gorka (Go)(DEDR 2126).

kod. = place where artisans work (Gujarati) kod. = a cow-pen; a cattlepen; a byre (G.lex.) gor.a = a cow-shed; a cattleshed; gor.a orak = byre (Santali.lex.) got.ho [Skt. kos.t.ha the inner part] a warehouse; an earthen

Rebus: kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A. kundār, B. kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H. kũderā m. ‘one who works a lathe, one who scrapes’, rī f., kũdernā ‘to scrape, plane, round on a lathe’; kundakara—m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण [ kōndaṇa ] n (कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার [ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver. খোদকারি n. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work. খোদাই [ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving. খোদাই করা v. to engrave; to carve. খোদানো v. & n. en graving; carving. খোদিত [ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/meluhha-metalwork-in-lapidary-turner.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/03/explaining-writing-system-as-ciphertext.html

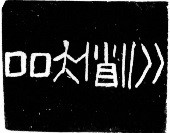

Annex B: aya 'fish' Rebus: ayas 'metal'

The meaning of 'ayas' in Rigveda has been uncertain and conjectures have been made from the texts as exemplified by the succinct presentation by

Arthur Anthony Macdonell, and Arthur Berriedale Keith:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A more precise understanding of the gloss 'ayas' comes from the frequent use of a hieroglyph on Indus Script inscriptions. A Munda gloss for fish is 'aya'. Read rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati) ayas 'metal' (Vedic). The script inscriptions indicate a set of modifiers or ligatures to the hieroglyph indicating that the metal, aya, was worked on during the early Bronze Age metallurgical processes -- to produce aya ingots, aya metalware,aya hard alloys.

Fish hieroglyph in its vivid orthographic form is shown in a Susa pot which contained metalware -- weapons and vessels. Context for use of ‘fish’ glyph. This photograph of a fish and the ‘fish’ glyph on Susa pot are comparable to the ‘fish’ glyph on Indus inscriptions. The modifiers to the 'fish' hieroglyph which commonly occur together are: slanted stroke, notch, fins, lid-of-pot ligatured as superfix:![]() For determining the semantics of the messages conveyed by the script. Positional analysis of ‘fish’ glyphs has also been presented in: The Indus Script: A Positional-statistical Approach By Michael Korvink, 2007, Gilund Press. For determining the semantics of the messages conveyed by the script. Positional analysis of ‘fish’ glyphs has also been presented in: The Indus Script: A Positional-statistical Approach By Michael Korvink, 2007, Gilund Press.

Table from: The Indus Script: A Positional-statistical Approach By Michael Korvink, 2007, Gilund Press. Mahadevan notes (Para 6.5 opcit.) that ‘a unique feature of the FISH signs is their tendency to form clusters, often as pairs, and rarely as triplets also. This pattern has fascinated and baffled scholars from the days of Hunter posing problems in interpretation.’ One way to resolve the problem is to interpret the glyptic elements creating ligatured fish signs and read the glyptic elements rebus to define the semantics of the message of an inscription. karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) Rebus: fire-god: @B27990. #16671. Remo <karandi>E155 {N} ``^fire-^god''.(Munda) Rebus:. kharādī ‘ turner’ (Gujarati) ![]() The 'parenthesis' modifier is a circumfix for both 'fish' and 'duck' hieroglyphs, the semantics of () two parenthetical modifiers are: kuṭilá— ‘bent, crooked’ KātyŚr., °aka— Pañcat., n. ‘a partic. plant’ [√kuṭ 1] Pa. kuṭila— ‘bent’, n. ‘bend’; Pk. kuḍila— ‘crooked’, °illa— ‘humpbacked’, °illaya— ‘bent’DEDR 2054 (a) Ta. koṭu curved, bent, crooked; koṭumai crookedness, obliquity; koṭukki hooked bar for fastening doors, clasp of an ornament. A pair of curved lines: dol ‘likeness, picture, form’ [e.g., two tigers, two bulls, sign-pair.] Kashmiri. dula दुल । युग्मम् m. a pair, a couple, esp. of two similar things (Rām. 966). Rebus: dul meṛeḍ cast iron (Mundari. Santali) dul ‘to cast metal in a mould’ (Santali) pasra meṛed, pasāra meṛed = syn. of koṭe meṛed = forged iron, in contrast to dul meṛed, cast iron (Mundari.) Thus, dul kuṭila ‘cast bronze’. The parenthetically ligatured fish+duck hieroglyphs thus read rebus: dul kuṭila ayas karaḍā 'cast bronze ayasor cast alloy metal with ayas as component to create karaḍā ''hard alloy with ayas'. ![]() Ligatures to fish: parentheses + snout dul kuṭila ayas 'cast bronze ayas alloy with tuttha, copper sulphate' Ligatures to fish: parentheses + snout dul kuṭila ayas 'cast bronze ayas alloy with tuttha, copper sulphate'

Modifier hieroglyph: 'snout' Hieroglyph: WPah.kṭg. ṭōṭ ʻ mouth ʼ.WPah.kṭg. thótti f., thótthəṛ m. ʻ snout, mouth ʼ, A. ṭhõt(phonet. thõt) (CDIAL 5853). Semantics, Rebus:

tutthá n. (m. lex.), tutthaka -- n. ʻ blue vitriol (used as an eye ointment) ʼ Suśr., tūtaka -- lex. 2. *thōttha -- 4. 3. *tūtta -- . 4. *tōtta -- 2. [Prob. ← Drav. T. Burrow BSOAS xii 381; cf. dhūrta -- 2 n. ʻ iron filings ʼ lex.]1. N. tutho ʻ blue vitriol or sulphate of copper ʼ, B. tuth.2. K. thŏth, dat. °thas m., P. thothā m.3. S.tūtio m., A. tutiyā, B. tũte, Or. tutiā, H. tūtā, tūtiyā m., M. tutiyā m.

4. M. totā m.(CDIAL 5855) Ka. tukku rust of iron; tutta, tuttu, tutte blue vitriol. Tu. tukků rust; mair(ů)suttu, (Eng.-Tu. Dict.) mairůtuttu blue vitriol. Te. t(r)uppu rust; (SAN) trukku id., verdigris. / Cf. Skt. tuttha- blue vitriol (DEDR 3343). Fish + corner, aya koṇḍa, ‘metal turned or forged’ Fish, aya ‘metal’ Fish + scales, aya ã̄s (amśu) ‘metallic stalks of stone ore’. Vikalpa: badhoṛ ‘a species of fish with many bones’ (Santali) Rebus: baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) Fish + splinter, aya aduru ‘smelted native metal’ Fish + sloping stroke, aya ḍhāḷ ‘metal ingot’ Fish + arrow or allograph, Fish + circumscribed four short strokes This indication of the occurrence, together, of two or more 'fish' hieroglyphs with modifiers is an assurance that the modifiers ar semantic indicators of how aya 'metal' is worked on by the artisans.

ayakāṇḍa ‘’large quantity of stone (ore) metal’ or aya kaṇḍa, ‘metal fire-altar’. ayo, hako 'fish'; ãs = scales of fish (Santali); rebus: aya ‘metal, iron’ (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) Santali lexeme, hako ‘fish’ is concordant with a proto-Indic form which can be identified as ayo in many glosses, Munda, Sora glosses in particular, of the Indian linguistic area. beḍa hako (ayo) ‘fish’ (Santali); beḍa ‘either of the sides of a hearth’ (G.) Munda: So. ayo `fish'. Go. ayu `fish'. Go <ayu> (Z), <ayu?u> (Z),, <ayu?> (A) {N} ``^fish''. Kh. kaDOG `fish'. Sa. Hako `fish'. Mu. hai (H) ~ haku(N) ~ haikO(M) `fish'. Ho haku `fish'. Bj. hai `fish'. Bh.haku `fish'. KW haiku ~ hakO |Analyzed hai-kO, ha-kO (RDM). Ku. Kaku`fish'.@(V064,M106) Mu. ha-i, haku `fish' (HJP). @(V341) ayu>(Z), <ayu?u> (Z) <ayu?>(A) {N} ``^fish''. #1370. <yO>\\<AyO>(L) {N} ``^fish''. #3612. <kukkulEyO>,,<kukkuli-yO>(LMD) {N} ``prawn''. !Serango dialect. #32612. <sArjAjyO>,,<sArjAj>(D) {N} ``prawn''. #32622. <magur-yO>(ZL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish''. *Or.<>. #32632. <ur+GOl-Da-yO>(LL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish''. #32642.<bal.bal-yO>(DL) {N} ``smoked fish''. #15163. Vikalpa: Munda: <aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree''.#10171. So<aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree''. Indian mackerel Ta. ayirai, acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitis thermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma.ayala a fish, mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind of small fish, loach (DEDR 191) aduru native metal (Ka.); ayil iron (Ta.) ayir, ayiram any ore (Ma.); ajirda karba very hard iron (Tu.)(DEDR 192). Ta. ayil javelin, lance, surgical knife, lancet.Ma. ayil javelin, lance; ayiri surgical knife, lancet. (DEDR 193). aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330); adar = fine sand (Ta.); ayir – iron dust, any ore (Ma.) Kur. adar the waste of pounded rice, broken grains, etc. Malt. adru broken grain (DEDR 134). Ma. aśu thin, slender;ayir, ayiram iron dust.Ta. ayir subtlety, fineness, fine sand, candied sugar; ? atar fine sand, dust. அய.ர³ ayir, n. 1. Subtlety, fineness; நணசம. (த_வ_.) 2. [M. ayir.] Fine sand; நணமணல. (மலசலப. 92.) ayiram, n. Candied sugar; ayil, n. cf. ayas. 1. Iron; 2. Surgical knife, lancet; Javelin, lance; ayilavaṉ, Skanda, as bearing a javelin (DEDR 341).Tu. gadarů a lump (DEDR 1196) ![]() kadara— m. ‘iron goad for guiding an elephant’ lex. (CDIAL 2711). अयोगूः A blacksmith; Vāj.3.5. अयस् a. [इ-गतौ-असुन्] Going, moving; nimble. n. (-यः) 1 Iron (एति चलति अयस्कान्तसंनिकर्षं इति तथात्वम्; नायसोल्लिख्यते रत्नम् Śukra 4.169. अभितप्तमयो$पि मार्दवं भजते कैव कथा शरीरिषु R.8.43. -2 Steel. -3 Gold. -4 A metal in general. ayaskāṇḍa 1 an iron-arrow. -2 excellent iron. -3 a large quantity of iron. -क_नत_(अयसक_नत_) 1 'beloved of iron', a magnet, load-stone; 2 a precious stone; ˚मजण_ a loadstone; ayaskāra 1 an iron-smith, blacksmith (Skt.Apte) ayas-kāntamu. [Skt.] n. The load-stone, a magnet. ayaskāruḍu. n. A black smith, one who works in iron. ayassu. n. ayō-mayamu. [Skt.] adj. made of iron (Te.) áyas— n. ‘metal, iron’ RV. Pa. ayō nom. sg. n. and m., aya— n. ‘iron’, Pk. aya— n., Si. ya. AYAŚCŪRṆA—, AYASKĀṆḌA—, *AYASKŪṬA—. Addenda: áyas—: Md. da ‘iron’, dafat ‘piece of iron’. ayaskāṇḍa— m.n. ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ Pāṇ. gaṇ. viii.3.48 [ÁYAS—, KAA ́ṆḌA—]Si.yakaḍa ‘iron’.*ayaskūṭa— ‘iron hammer’. [ÁYAS—, KUU ́ṬA—1] Pa. ayōkūṭa—, ayak m.; Si. yakuḷa‘sledge —hammer’, yavuḷa (< ayōkūṭa) (CDIAL 590, 591, 592). cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa; Old Germ. e7r , iron ;Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen. Note on (amśu) ‘metallic stalks of stone ore’. An uncertain meaning of soma in Rigveda though the entire samhita holds the processing of soma in a nutshell, can be resolved in the context of modifers to 'fish' hieroglyph to denote 'fins or scales'. The vedic texts provide an intimation treating amśu as a synonym of soma. The link with the Tocharian word is intriguing because Soma was supposed to come from Mt. Mujavant. A cognate of Mujavant is Mustagh Ata of the Himalayan ranges in Kyrgystan. Is it possible that the ancu of Tocharian from this mountain was indeed Soma? The referemces to Anzu in ancient Mesopotamian tradition parallels the legends of śyena 'falcon' which is used in Vedic tradition of Soma yajña attested archaeologically in Uttarakhand with a śyenaciti, 'falcon-shaped' fire-altar.

I suggest that ayas of bronze age created a revolutionary transformation in the lives of people of these bronze age times.

|

Maybe, Tocharian ancu had the same meaning as Rigvedic gloss, amśu. If so, ancu might have denoted electrum, 'gold-silver compound' which was subjected to reduction, by oxidation of impurities, by incessant firing for five days and nights to create the shining wealth of gold. The old Egyptian gloss for electrum wasassem, cognate soma.

Reconstructing mleccha (meluhha) beyond identification of glosses is a very tall order and I have no competence whatsoever to take up the task. I have, however, produced a comparative lexicon for the India sprachbund with over 8000 semantic clusters. If it is validated, it could be a beginning to suggest phonetic and morphemic evolution and formation of languages such as Marathi or Bengali or Oriya. Syntax can only be inferred based on evidences provided in early Samskrtam-Prakrtam dramas of the type mentioned in Bharata's Nāṭyaśāstra. Bloch has done pioneering work on Marathi. Similar work has to be done for all languages of the language union which ancient India nurtured on the banks of River Sarasvati. She is vāgdevi and mleccha was a vācas. One thing is clear: if the lexemes related to metalware and metalwork are found as substratum lexemes, the date should be subsequent to the 4th millennium BCE of the bronze-age when tin-bronzes and zinc-bronzes supplemented arsenical bronzes; this was a veritable revolution of the times. Given the rich treasure,Bharata nidhi of ancient Hindu texts such as those of Patanjali or Bhartrhari, we have the work cut out for us to re-evaluate and sharpen our understanding of Bharatiya vāk, the ancient spoken idiom.

Indianized mleccha-, arya-vaacas in polyglossia linguistic area

"Indo-Aryan languages have a long history of transmission, not only in the form of literary works and treatises dealing with logical, philosophical, and ritual matters but also in phonetic, phonological, and grammatical descriptions. The languages are divisible into three major stages: Old-, Middle- and New- (or Modern-) Indo-Aryan. The first is represented by an enormously rich literature stretching over millennia, including Vedic texts and later literary works of various genres. In addition, we are privileged to have knowledge of the details of Old Indo-Aryan of different eras and areas through extraordinarily perceptive descriptions of phonetics and phonology relative to traditions of Vedic recitation in prAtizAkhya works and PANini's ASTAdhyAyI, the brilliant set of rules describing the language current at around the fifth century BCE, with important dialectical observations and contrasts drawn between the then current speech and earlier Vedic usage. Moreover, observations by YAska (possibly antedating PANini) and Patanjali (second century BCE) inform us about some dialect features of Old Indo-Aryan in early times...Speakers of Sanskrit were aware from early on not only of differences between their current language and Vedic but also of areal differences at a given time. Well known examples stem from YAska and Patanjali, who speak of usages proper to the Kamboja, SaurASTra, the east and midlands, as well as of Arya speakers. It is noteworthy that zav is said to occur in Kamboja, a northwestern people whom in his commentary on Nirukta 2.2 Durga refers to as Mleccha (Bhadkamkar 1918: 166.5-6: gatyartho dhAtuh kambojeSv eva bhASyate mleccheSu prakRtyA prayujyata AkhyAtapadabhAvena): zyav, zav, ziyav 'go' are used in Avestan and Old Persian...Patanjali refers to the use of hamm 'go' in SauRASTra. Another feature of the speech of this area is noted in the metrical version of the PANinIyazikSA, which says that nasalized vowels as in arAm 'spokes' of RV 8.77.3b (khe arAm iva khedayA'(...pushed...down) like spokes in the wheel navel with an instrument for pressing together') are pronounced in the manner that a woman from SauRAStra pronounces takram 'buttermilk': takraM, with a fully nasalized final vosel (PS 26: yathA saurASTrikA nArI takrAm ity abhibhASate evam rangAh prayoktavyA khe arAM iva khedayA). Patanjali is well aware of the r/l alternation in particular lexical terms...Old Indo-Aryan was of course dialectically differentiated (See Emeneau 1966). The earliest distribution of dialect areas would have to stem from Vedic times, and the texts, right back to the Rgveda, show evidence of dialect differences, reflected, for example, in the use of forms of the type dakSi and dhakSi 'burn' (Cardona 1991)...There is a large variety of PrAkrits, traditionally named after regions and their inhabitants: MAhArASTrI, zaurasenI and so on. Thus, Bharata mentions (NZ 17.48: mAgadhy avantijA prAcyA zauraseny ardhamAgadhI bAhlikA dAkSiNatyA ca sapta bhASAh prakIrtitA) seven languages as being well known: MAgadhI, the language of Avanti, the language of the east, ZaurasenI, ArdhamAgadhI, BAhlIkA, and the language of the south. Theoreticians of poetics and grammarians of PrAkrits also enumerate and characterize different PrAkrits, among wich MAhArAStrI is given the highest status...The closest thing we have comparable to a dialect map of Middle Indo-Aryan is represented by Azoka's inscriptions of the third century BCE. As has been recognizedd (See Bloch 1950: 43-5, Azokan/PAli section 1.2), the major rock edicts show that east, nortwest and west constitute three major dialect areas...Arya has various meanings centering about the notion of noble, venerable, honorable, but this term was explicitly used with reference to a particular group of people, characterized by the way they spoke...Patanjali uses the phrases AryA bhASante 'Aryas say' and AryAh prayunjate 'Aryas use'. In the comparable passage of his Nirukta, YAska (Nir. 2.2 [161.11-13]) says zavatir gatikarmA kambojeSv eva bhASyate...vikAram asyAryeSu bhASante zava it 'zav meaning 'go' is used only in Kamboja...in the Arya community one uses a derivate (vikAram 'modification) zava 'corpse''. Here, YAska uses the locative plural AryeSu parallel to kambojeSu, both terms referring to communities in which particular usages prevail...The Indian subcontinent has long been home to speakers of languages belonging to different language failies, principally Indo-European (Indo-Aryan), Dravidian, and Austro-Asiatic (Munda). It is to be expected that speakers of these languages who were in contact with each other should have been subject to possible influence of other languages on their own. Scholars have long been aware of and remarked on the changes which the language reflected in the earliest Vedic underwent over time, gradually becoming more and more 'Indianized', so that one can speak of an Indian linguistic area (Emeneau 1956, 1971, 1974, 1980, Kuiper 1967). Scholars have also differed concerning the degree of influence exerted by Munda or Dravidian languages on Indo-Aryan at different stages and the manner in which such influence was made felt. It is proper to emphasize from the outset that Old Indo-Aryan should be viewed as encompassing a variety of regional and social dialects spoken natively, developing historically in the way any living language does, and whose speakers interacted in a society where diglossia and polyglossia were the norm. Sanskrit speakers show an awareness of these facts. Thus, it is not only historically true that early Vedic root aorists of the type akar, agan were gradually replaced by forms of the types akArSU, agamat but also that YAska and Patanjali were aware of such changes and brought the fact out in their paraphrases; see Mehendale 1968: 15-33. PANini accounted for major features of Vedic which differed from his current language. In addition, such early native speakers of Sanskrit give us evidence of attitudes towards different varieties of speech which should be taken into consideration...Patanjali recounts the dialogue: A certain grammarian (kazcid vaiyAkaraNah) says to a chariot driver, ko 'sya rathasya pravetA 'Who is the driver of this car?' The driver answers, AyuSmann aham prAjitA 'Sir, I am the driver', upon which the grammarian accuses him of using an incorrect speech form (apazabda). The driver retorts that the grammarian knows what should obtain by rule (prAptijnah) but not what is desired (iSTijnah): this term is desirable (iSyata etad rUpam), Patanjali doubtless reflects a historical change in the language between PANini's time and area and his. At the same time, he is clearly willing to countenance that usage could include terms which a strict grammarian might consider improper. And he puts this in terms of a contrast between a grammarian and a charioteer. Another famous MaHAbhASya passage concerns sages (RSi-) who were characterized by the way they pronounced the phrases yad vA nah and tad vA nah: yar vA nah, tar vA nah. Although these sages spoke with such vernacular features, they did not do so during ritual acts...On the contrary, both accepted forms and those considered incorrect served equally to convey meanings, and what distinguished corrrect speech was that one gaind merit from such usage accompanied by a knowledge of its grammatical formation. One must recognize also that the standard speech could include elements which originally were not part of the Sanskrit norm. Moreover, Zabara remarks (on JS 1.3.5.10 [II.151]) that although authoity (pramANam) is granted to a learned elite (ziSTAh whose behaviour is authoritative with respect to what cannot be known directly (yat tu ziSTAcArah pramANam iti tat pratyakSAnavagate 'rthe) and who are experts (abhiyuktAh) as concerns the meanings of terms, nevertheless Mlecchas are more expert as concernss the care and binding of birds (yat tv abhiyuktAh zabdArtheSu ziSTA iti tatrocyate: abhiyuktatarAh pakSiNAm poSaNe bandhan ca mlecchAh). Consequently, when it comes to terms like pika- 'cuckcoo', which Aryas do not use in any meaning but which Mlecchas do (ZBh. 1.3.5.10 [II.149]: atha yAN chamdAn AryA na kasmimzcid artha Acaranti mlecchAs tu kasmimzcit prayunjate yathA pika...), authority is granted to Mleccha usage...There is thus evidence to show that before the second century BCE and possibly before PANini's time Mlecchas who inhabited areas outside the bounds of AryAvartta could be absorbed into the prevalent social system and that terms from speech areas such as that of the Kambojas could be treated as Indo-Aryan...Arya brAhmaNas normally were not supposed to engage in discourse with Mlecchas, but they had to do so on occasion. In brief, the picture is that of a society in which an Arya group considered itself the carrier of a higher culture and strived to keep this culture and the language associated with it but at the same time had necessarily to interact with groups like Mlecchas, whose language and customs were considered lesser. The result of such interaction, both with other Indo-Aryans who spoke dalects with Middle Indo-Aryan features and with non-Indo-Aryans, was that Sanskrit was effected through adoption of lexical terms and grammatical features...There is no cogent reason to consider that such changes due to contact had not been carried out gradually over generations for a long time before. Modern views. Although scholars generally agree that Old Indo-Aryan was indeed affected by 'autochthonous' languages and that there is indeed a South Asia linguistic area (see, e.g., Emeneau 1956, 1980, Kuiper 1967, Masica 1976), there are disagreements concerning the possible degree to which such effects should be seen in early Vedic and whether the features at issue could reflect also developments from Indo-European sources. In addition to the extent and sources of lexical borrowings, the main points of contention concern four features commonly considered characteristic of a South Asian linguistic area: (1) a contrast between retroflex and dental consonants, (2) the use of quotative particle (Skt. iti), (3) the use of absolutives (Skt. -tvA, ya), (4) the general unmarked word subject-object-verb...As to what non-Indo-Aryan languages are concerned, obvious candidates are Dravidian and Munda languages. The number of such borrowings into early Indo-Aryan has been the topic of ongoing debate...It has also to be admitted that the archaeological evidence available does not serve to confirm Indo-Aryan migrations into the subcontinent. Moreover, there is no textual evidence in the early literary traditions unambiguously showing a trace of such migration...In an email message kindly conveyed to me by S. Kalyanaraman (11 April 1999)...BaudhAyanazrautasUtra passage...this text cannot serve to document an Indo-Aryan migration into the main part of the subcontinent... " (Dhanesh Jain, George Cardona (eds.), 2003, The Indo-Aryan languages, Routledge, pp.6-7,17-21, 26-28, 31-37).

All indications point to Vedic people performing their fire worship on the banks of River Sarasvati. The river basin has revealed 80% or over 2000 of the 2600 archaeological sites of Sarasvati-Sindhu (Hindu) civilization. Language, astronomical, and archaeological pointers refer to 7th millennium BCE as the date for the formation of language and activities of Vedic people on this doab of Sarasvati-Sindhu rivers.

Baudhāyana Śrautasūtra belongs to Taittiriya Shakha school of the Krishna Yajurveda (ca. 6th century BCE). This Vedic text has the following statement:

pran Ayuh pravavraja. Tasyaite Kuru-Pancalah Kasi-Videha ity. Etad Ayavam pravrajam. Pratyan amavasus. Tasyaite Gandharvarayas Parsavo ‘ratta ity. Etad Amavasavam. (BSS18.44:397.9 sqq)

Translation: Ayu migrated eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru-Pancalas and the Kasi-Videhas. This is the Ayava (migration). Amavasu migrated westwards. His (people) are the Ghandhari, Parsu and Aratta. This is the Amavasu (migration).

This Sutra provides evidence for two historical narratives: 1. Both Ayu and Amavasu were indigenous Vedic people located in the Sarasvati-Sindhu river basins and hence, provides ZERO evidence for any mythical Aryan Invasion/Migration theory; 2. the movements of people away from Kurukshetra on the banks of River Sarasvati attest to the formation of the Indian sprachbund in Gangetic basin, Gujarat and beyond including areas west of River Sindhu (Indus).

The memory recorded in the Sutra refers to an ancient Itihasa of Bharatam Janam, in the context of narratives related to philosophers of fire, worshippers of fire. That the legend is mentioned as a received memory in Rigveda points to the possibility of this narrative related to Ayu and Amavasu being dated earlier than 7th millennium BCE. The passage is part of a dialogue between Pururava and Urvasi. Their sons were Ayu and Amavasu who were associated with two twin groups formed as they wandered forth: Ayava (eastern) kin group and Amavasava (western) kin group.

Yes, there were migrations but the text in Baudhāyana Śrautasūtra emphatically declares the directions of earlier migrations of Ayu and Amavasu who are memories from events in bygone millennia, perhaps earlier to the 7th millennium BCE which is the date posited for Rigveda by other evidences such as the archaeologically attested pit-dwellings of Bhirrana, a site which is dated to 7th millennium BCE. Nicholas Kazanas a scholar in Indo-European studies dates the bulk of Rigveda to the fourth millennium BCE based on hiseorical linguistic analyses. (Kazanas, Nicholas, 2015, Vedic and Indo-European Studies, Delhi, Aditya Prakashan, p.xxxi). After affirming that Indo-Aryans were indigenous to India from at least the 7th millennium BCE, Kazanas also notes that Vedic is much older than any other IE language and suggests a fresh start to IE studies and to studies on Proto-Indo-European mother tongue. In all his studies spanning many IE branches, comparing evidences from the linguistic, literary, anthropological and archaeological fields (and from Genetics), Vedic inheritance emerges as the oldest of all IE traditions, older than even the Near Eastern cultures; the bulk of the Rgveda hymns appear to have been composed with Indo-Aryans residing in North-West India (and Pakistan) since about 5000 BCE.

BB Lal's work,(The Rigvedic People, 'Invaders'? 'Immigrants'? or Indigenous? -- Evidence of Archaeology and Literature, 2015, Aryan Books International) notes that the Rigveda (10.75, 5-6) refers to Vedic people occupying the entire territory from the Indus on the west to the upper reaches of the Ganga-Yamuna in the east and only one civilization that existed in the same region: Harappan Civilization. Lal concludes that the Civilization and Vedas are but two faces of the same coin (pp.122-23) and adds that evidence from Kunal and Bhirrana (pp. 54-55) trace the roots of the civilization to the 6th-5th millennia BCE, indicating that Harappans were the 'sons of the soil' and not aliens. Thus, according to Lal, the Vedic people who were themselves the Harappans, were indigenous and neither 'invaders' nor 'immigrants'.

![]()