Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/j5dx7qd

This is an addendum to http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/07/mohenjo-daro-and-dr-w-i-say-indus.html

Mohenjo-daro and Dr. W. I say "Indus Script is a knowledge system". I look forward to Dr. W's rebuttal.

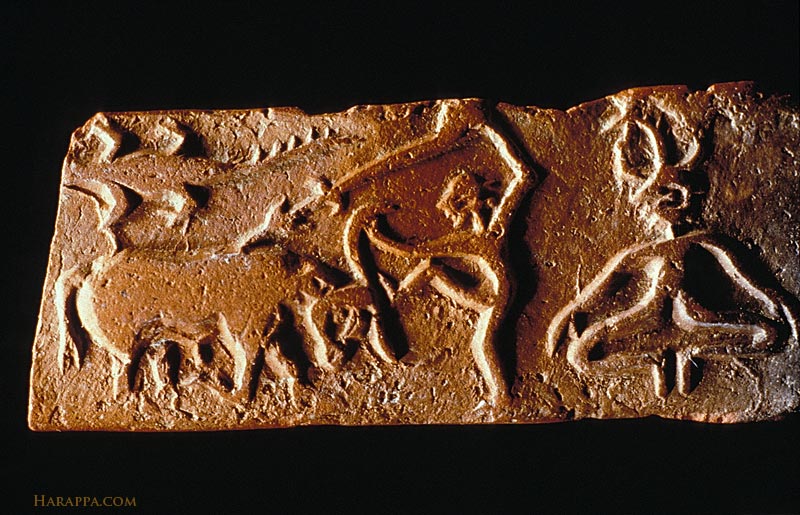

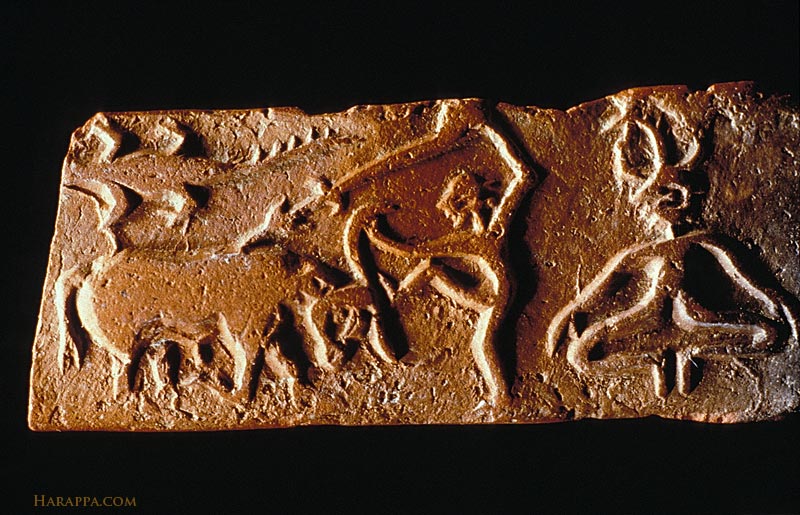

A Harappa tablet discovered by HARP team (H2001-5075/2922-01) compares with h489 tablet with comparable narratives & hypertexts. Both molded terracotta tablets have inscriptions on two sides.

![]() h2001-5075/2922-01 Harappa tablet

h2001-5075/2922-01 Harappa tablet

![]() h489A

h489A![]() h489B Harappa tablet (in Harappa museum)

h489B Harappa tablet (in Harappa museum)

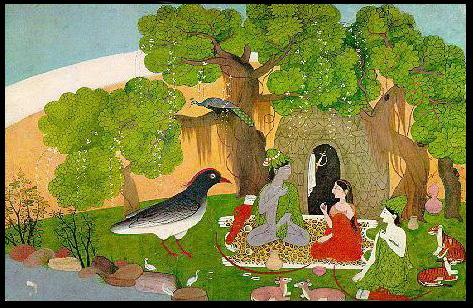

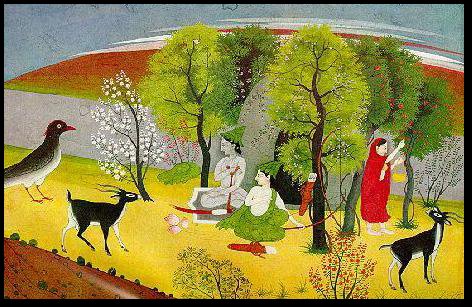

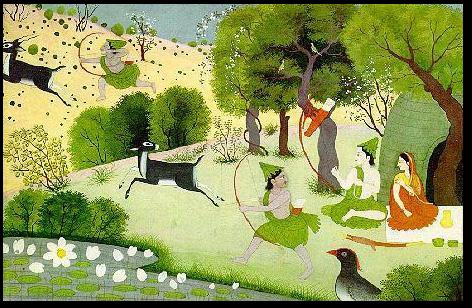

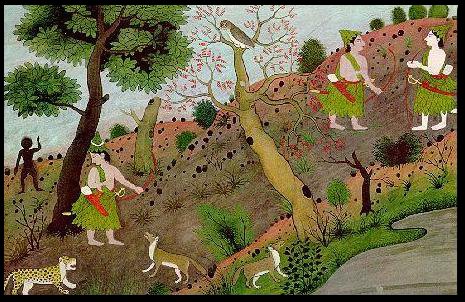

One side (the reverse) of two molded terra cotta tablets signify a common narrative or hypertext: a woman grapples with two tigers and stands above an elephant. Top of the narrative is a spoked wheel.

All are hieroglyphs: kola 'woman' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' karibha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ib 'iron' eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'copper' arA 'spokes' rebus: Ara 'brass'.

![]() h489 (Also, reverse of tablet H2001-5075/2922-01 hazily seen). A sharper orthographic representation of the woman grappling with two igers occurs on another seal of Mohenjo-daro. The face of the woman with a hypertext composed of hieroglyphs signifies: kammaṭa, kampaṭṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage.'

h489 (Also, reverse of tablet H2001-5075/2922-01 hazily seen). A sharper orthographic representation of the woman grappling with two igers occurs on another seal of Mohenjo-daro. The face of the woman with a hypertext composed of hieroglyphs signifies: kammaṭa, kampaṭṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage.'

![]()

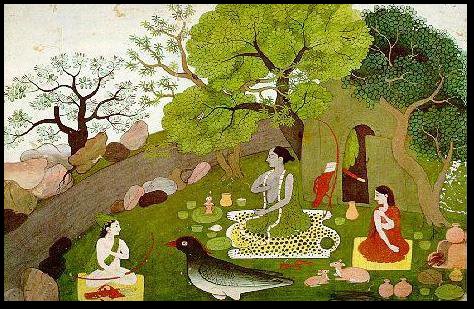

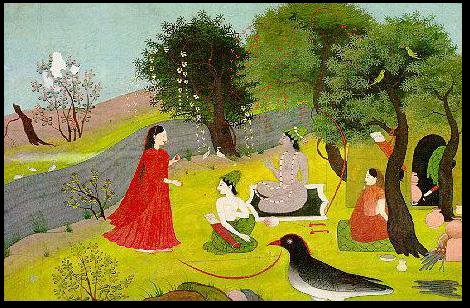

The obverse side of the tablets of Harappa have two different narratives: 1. One narrative shows a tiger looking up at a spy on a tree branch (H2001-5075/2922-01). 2. Another narrative shows a person kicking and spearing a bovine (h489B) PLUS crocodile and a horned person seated in penance with twig head-dress as field hieroglyphs.

The unique orthography on the face of the woman shows a circle around one eye: kāṇī ʻone -- eyedʼ (feminine) PLUS வட்டம்¹ vaṭṭam < Pkt. vaṭṭavṛtta. n. 1. Circle, circular form, ring-like shape; மண்ட லம். (தொல். சொல். 402, உரை.) 2. Halo round the sun or moon, a karantuṟai-kōḷ; பரிவேடம். (சிலப். 10, 102, உரை.) (சினேந். 164.) 3. Potter's wheel; குயவன் திரிகை. (பிங்.) 4. Wheel of a cart; வண்டிச்சக்கரம். (யாழ். அக.) baṭlohi ʻ round metal vessel ʼ(Nepalese).

Thus, the orthographic composition is read as kāṇī vaṭṭa 'eye + circular form' Rebus the expression is: kan 'copper' +bhaTa 'furnace' or khambhaṛā which signifies 'fish-fin' and also 'mint' (with variant pronunciations: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236). The orthographic composition is thus explained rebus as copper mint (kan + bhaTa).

There are six round blobs around the hairstyle of the woman: baTa 'six, round stone' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'.

The six blobs may also signify six locks of hair:मेढा (p. 391) mēḍhā A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl (Marathi) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meD 'iron'(Santali.Mu.Ho.).med 'copper' (Slavic languages).

Ta. kaṉ copper work, copper, workmanship; kaṉṉāṉ brazier. Ma. kannān id.(DEDR 1402)

Hieroglyphs: six, round stone: baTa 'six' baTT 'round stone': WPah.bhal. baṭṭ m. ʻ small round stone ʼ; Or. bāṭi ʻ stone ʼ; Bi. baṭṭā ʻ stone roller for spices, grindstone ʼ. -- With unexpl. -- ṭṭh -- : Sh.gur. baṭṭh m. ʻ stone ʼ, gil. baṭhāˊ m. ʻ avalanche of stones ʼ (CDIAL 11348) Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'Rebus: bhaṭṭhā 'kiln, furnace': bhráṣṭra n. ʻ frying pan, gridiron ʼ MaitrS. [√bhrajj ]

Pk. bhaṭṭha -- m.n. ʻ gridiron ʼ; K. büṭhü f. ʻ level surface by kitchen fireplace on which vessels are put when taken off fire ʼ; S. baṭhu m. ʻ large pot in which grain is parched, large cooking fire ʼ, baṭhī f. ʻ distilling furnace ʼ; L. bhaṭṭh m. ʻ grain -- parcher's oven ʼ, bhaṭṭhī f. ʻ kiln, distillery ʼ, awāṇ. bhaṭh; P. bhaṭṭh m., °ṭhī f. ʻ furnace ʼ, bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ; N. bhāṭi ʻ oven or vessel in which clothes are steamed for washing ʼ; A. bhaṭā ʻ brick -- or lime -- kiln ʼ; B. bhāṭi ʻ kiln ʼ; Or. bhāṭi ʻ brick -- kiln, distilling pot ʼ; Mth. bhaṭhī, bhaṭṭī ʻ brick -- kiln, furnace, still ʼ; Aw.lakh. bhāṭhā ʻ kiln ʼ; H. bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ, bhaṭ f. ʻ kiln, oven, fireplace ʼ; M. bhaṭṭā m. ʻ pot of fire ʼ, bhaṭṭī f. ʻ forge ʼ. -- X bhástrā -- q.v. bhrāṣṭra -- ; *bhraṣṭrapūra -- , *bhraṣṭrāgāra -- . Addenda: bhráṣṭra -- : S.kcch. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ʻ distil (spirits) ʼ. *bhraṣṭrapūra ʻ gridiron -- cake ʼ. [Cf. bhrāṣṭraja -- ʻ pro- duced on a gridiron ʼ lex. -- bhráṣṭra -- , pūra -- 2 ] P. bhaṭhūhar, °hrā, bhaṭhūrā, °ṭhorū m. ʻ cake of leavened bread ʼ; -- or < *bhr̥ṣṭapūra - *bhraṣṭrāgāra ʻ grain parching house ʼ. [bhráṣṭra -- , agāra -- ] P. bhaṭhiār, °ālā m. ʻ grainparcher's shop ʼ.(CDIAL 9656, 9657, 9658)

*varta2 ʻ circular object ʼ or more prob. ʻ something made of metal ʼ, cf. vartaka -- 2 n. ʻ bell -- metal, brass ʼ lex. and vartalōha -- . [√vr̥t ?] Pk. vaṭṭa -- m.n., °aya -- m. ʻ cup ʼ; Ash. waṭāˊk ʻ cup, plate ʼ; K. waṭukh, dat. °ṭakas m. ʻ cup, bowl ʼ; S. vaṭo m. ʻ metal drinking cup ʼ; N.bāṭā, ʻ round copper or brass vessel ʼ; A. bāṭi ʻ cup ʼ; B. bāṭā ʻ box for betel ʼ; Or. baṭā ʻ metal pot for betel ʼ, bāṭi ʻ cup, saucer ʼ; Mth. baṭṭā ʻ large metal cup ʼ, bāṭī ʻ small do. ʼ, H. baṭṛī f.; G. M. vāṭī f. ʻ vessel ʼ.(CDIAL 11347) *varta3 ʻ round stone ʼ. 2. *vārta -- . [Cf. Kurd. bard ʻ stone ʼ. -- √vr̥t 1 ] 1. Gy. eur. bar, SEeur. bai̦ ʻ stone ʼ, pal. wăṭ, wŭṭ ʻ stone, cliff ʼ; Ḍ. boṭ m. ʻ stone ʼ, Ash. Wg. wāṭ, Kt. woṭ, Dm. bɔ̈̄'ṭ, Tir. baṭ, Niṅg. bōt, Woṭ.baṭ m., Gmb. wāṭ; Gaw. wāṭ ʻ stone, millstone ʼ; Kal.rumb. bat ʻ stone ʼ (bad -- váṣ ʻ hail ʼ), Kho. bort, Bshk. baṭ, Tor. bāṭ, Mai. (Barth) "bhāt" NTS xviii 125, Sv. bāṭ, Phal. bā̆ṭ; Sh.gil. băṭ m. ʻ stone ʼ, koh. băṭṭ m., jij. baṭ, pales. baṭ ʻ millstone ʼ; K. waṭh, dat. °ṭas m. ʻ round stone ʼ, vüṭü f. ʻ small do. ʼ; L. vaṭṭā m. ʻ stone ʼ, khet. vaṭ ʻ rock ʼ; P. baṭṭ m. ʻ a partic. weight ʼ, vaṭṭā, ba° m. ʻ stone ʼ, vaṭṭī f. ʻ pebble ʼ; WPah.bhal. baṭṭ m. ʻ small round stone ʼ; Or. bāṭi ʻ stone ʼ; Bi. baṭṭā ʻ stone roller for spices, grindstone ʼ. -- With unexpl. -- ṭṭh -- : Sh.gur. baṭṭh m. ʻ stone ʼ, gil. baṭhāˊ m. ʻ avalanche of stones ʼ, baṭhúi f. ʻ pebble ʼ (suggesting also an orig. *vartuka -- which Morgenstierne sees in Kho. place -- namebortuili, cf. *vartu -- , vartula -- ). 2. Paš.lauṛ. wāṛ, kuṛ. wō ʻ stone ʼ, Shum. wāṛ.vartaka -- 1 ; *vartadruṇa -- , *vartapānīya -- ; *aṅgāravarta -- , *arkavarta -- , *kaṣavartikā -- (CDIAL 11348)

1 m. ʻ *something round ʼ (ʻ horse's hoof ʼ lex.), vaṭṭaka -- m. ʻ pill, bolus ʼ Bhadrab. [Cf. Orm. waṭk ʻ walnut ʼ (wrongly ← IA. *akhōṭa -- s.v. akṣōṭa -- ). <-> √vr̥t 1 ]

Wg. wāṭi( -- štūm) ʻ walnut( -- tree) ʼ NTS vii 315; K. woṭu m., vüṭü f. ʻ globulated mass ʼ; L. vaṭṭā m. ʻ clod, lobe of ear ʼ; P. vaṭṭī f. ʻ pill ʼ; WPah.bhal. baṭṭi f. ʻ egg ʼ.

vartaka --2 n. ʻ bell -- metal, brass ʼ lex. -- See *varta -- 2 , vártalōha -- . (CDIAL 11349)

vartalōha n. ʻ a kind of brass (i.e. *cup metal?) ʼ lex. [*varta -- 2 associated with lōhá -- by pop. etym.?]Pa. vaṭṭalōha -- n. ʻ a partic. kind of metal ʼ; L.awāṇ. valṭōā ʻ metal pitcher ʼ, P. valṭoh, ba° f., vaṭlohā, ba° m.; N. baṭlohi ʻ round metal vessel ʼ; A. baṭlahi ʻ water vessel ʼ; B. bāṭlahi, bāṭulāi ʻ round brass cooking vessel ʼ; Bi. baṭlohī ʻ small metal vessel ʼ; H. baṭlohī, °loī f. ʻ brass drinking and cooking vessel ʼ, G. vaṭloi f.Addenda: vartalōha -- : WPah.kṭg. bəlṭóɔ m. ʻ large brass vessel ʼ.(CDIAL 11357)

The first type of narrative records products from a smelter. The second type of narrative records products from a smithy/mint.

This is an addendum to http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/07/mohenjo-daro-and-dr-w-i-say-indus.html

Mohenjo-daro and Dr. W. I say "Indus Script is a knowledge system". I look forward to Dr. W's rebuttal.

Is there a chance that Dr. W will respond to the request in the interest of contributions to civilization studies which is a subject area common to both Dr. K and Dr. W?

A Harappa tablet discovered by HARP team (H2001-5075/2922-01) compares with h489 tablet with comparable narratives & hypertexts. Both molded terracotta tablets have inscriptions on two sides.

h2001-5075/2922-01 Harappa tablet

h2001-5075/2922-01 Harappa tablet h489A

h489A h489B Harappa tablet (in Harappa museum)

h489B Harappa tablet (in Harappa museum)One side (the reverse) of two molded terra cotta tablets signify a common narrative or hypertext: a woman grapples with two tigers and stands above an elephant. Top of the narrative is a spoked wheel.

All are hieroglyphs: kola 'woman' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' karibha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ib 'iron' eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'copper' arA 'spokes' rebus: Ara 'brass'.

h489 (Also, reverse of tablet H2001-5075/2922-01 hazily seen). A sharper orthographic representation of the woman grappling with two igers occurs on another seal of Mohenjo-daro. The face of the woman with a hypertext composed of hieroglyphs signifies: kammaṭa, kampaṭṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage.'

h489 (Also, reverse of tablet H2001-5075/2922-01 hazily seen). A sharper orthographic representation of the woman grappling with two igers occurs on another seal of Mohenjo-daro. The face of the woman with a hypertext composed of hieroglyphs signifies: kammaṭa, kampaṭṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage.'

The obverse side of the tablets of Harappa have two different narratives: 1. One narrative shows a tiger looking up at a spy on a tree branch (H2001-5075/2922-01). 2. Another narrative shows a person kicking and spearing a bovine (h489B) PLUS crocodile and a horned person seated in penance with twig head-dress as field hieroglyphs.

This unique composition of the face of a woman includes identifiable hieroglyphs: 1. eye (kaN, kANi); 2. circular form (baTa); 3. six round (stones)(baTa); 4. face (mũh).

Each hieroglyph is rendered rebus: kan 'copper' baTa 'circular form' baTa 'six stones'muhã'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'

mũh 'a face' in Indus Script Cipher signifies mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'

Indus Script hieroglyphs of Prakrtam sprachbund lexis khambhaṛā 'fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint' has a synonymகண்வட்டம் kaṇ-vaṭṭam 'mint, coiner, coinage'

The note has recorded evidence that கண்வட்டம் kaṇ-vaṭṭam 'mint' has a synonym (demonstrably, a phonetic variant in mleccha/meluhha): khambhaṛā 'fin' (Lahnda) rebus: kammaTa 'mint' and these two expressions are combined in the Begram ivory (Plate 389)

The unique orthography on the face of the woman shows a circle around one eye: kāṇī ʻone -- eyedʼ (feminine) PLUS வட்டம்¹ vaṭṭam < Pkt. vaṭṭavṛtta. n. 1. Circle, circular form, ring-like shape; மண்ட லம். (தொல். சொல். 402, உரை.) 2. Halo round the sun or moon, a karantuṟai-kōḷ; பரிவேடம். (சிலப். 10, 102, உரை.) (சினேந். 164.) 3. Potter's wheel; குயவன் திரிகை. (பிங்.) 4. Wheel of a cart; வண்டிச்சக்கரம். (யாழ். அக.) baṭlohi ʻ round metal vessel ʼ(Nepalese).

Thus, the orthographic composition is read as kāṇī vaṭṭa 'eye + circular form' Rebus the expression is: kan 'copper' +bhaTa 'furnace' or khambhaṛā which signifies 'fish-fin' and also 'mint' (with variant pronunciations: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236). The orthographic composition is thus explained rebus as copper mint (kan + bhaTa).

There are six round blobs around the hairstyle of the woman: baTa 'six, round stone' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'.

The six blobs may also signify six locks of hair:

Ta. kaṉ copper work, copper, workmanship; kaṉṉāṉ brazier. Ma. kannān id.(DEDR 1402)

Hieroglyphs: six, round stone: baTa 'six' baTT 'round stone': WPah.bhal. baṭṭ m. ʻ small round stone ʼ; Or. bāṭi ʻ stone ʼ; Bi. baṭṭā ʻ stone roller for spices, grindstone ʼ. -- With unexpl. -- ṭṭh -- : Sh.gur. baṭṭh m. ʻ stone ʼ, gil. baṭhāˊ m. ʻ avalanche of stones ʼ (CDIAL 11348) Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

*varta

vartaka --

vartalōha n. ʻ a kind of brass (i.e. *cup metal?) ʼ lex. [*

The first type of narrative records products from a smelter. The second type of narrative records products from a smithy/mint.

Molded terracotta tablet (H2001-5075/2922-01) with a narrative scene of a man in a tree with a tiger looking back over its shoulder. The tablet, found in the Trench 54 area on the west side of Mound E, is broken, but was made with the same mold as ones found on the eastern side of Mound E and also in other parts of the site (see slide 89 for the right hand portion of the same scene). The reverse of the same molded terra cotta tablet shows a deity grappling with two tigers and standing above an elephant (see slide 90 for a clearer example from the same mold). https://www.harappa.com/indus3/185.html heraka 'spy' rebus: eraka 'moltencast copper' kuTi 'tree' rebus:kuThi 'smelter' karA 'crocodile' rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' barad 'bull' rebus: baraDo 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'. Another animal (perhaps bovine) is signified in a procession together with the tiger. This may signify barad, balad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'. Thus the products shown as from smithy (blacksmith).with a smelter.

![]() h489A

h489A![]() h489B

h489B

Slide 89 Plano convex molded tablet showing an individual spearing a water buffalo with one foot pressing the head down and one arm holding the tip of a horn. A gharial is depicted above the sacrifice scene and a figure seated in yogic position, wearing a horned headdress, looks on. The horned headdress has a branch with three prongs or leaves emerging from the center.

![Images show a figure strangling two tigers with his bare hands.]()

कुंठणें [ kuṇṭhaṇēṃ ] v i (

கண்வட்டம் kaṇ-vaṭṭam , n. < id. +. 1. Range of vision, eye-sweep, full reach of one's observation;கண்பார்வைக்குட்பட்ட இடம். தங்கள் கண்வட்டத்திலே உண்டுடுத்துத்திரிகிற (ஈடு, 3, 5, 2). 2. Mint;நாணயசாலை.

Bengali word: f. kāṇī ʻone -- eyedʼ: kāṇá ʻ one -- eyed ʼ RV.Pa. Pk. kāṇa -- ʻ blind of one eye, blind ʼ; Ash. kã̄ṛa, °ṛī f. ʻ blind ʼ, Kt. kãŕ, Wg. kŕãmacrdotdot;, Pr. k&schwatildemacr;, Tir. kāˊna, Kho. kāṇu NTS ii 260, kánu BelvalkarVol 91; K. kônu ʻ one -- eyed ʼ, S.kāṇo, L. P. kāṇã̄; WPah. rudh. śeu. kāṇā ʻ blind ʼ; Ku. kāṇo, gng. kã̄&rtodtilde; ʻ blind of one eye ʼ, N. kānu; A. kanā ʻ blind ʼ; B. kāṇā ʻ one -- eyed, blind ʼ; Or. kaṇā, f. kāṇī ʻ one -- eyed ʼ, Mth. kān, °nā,kanahā, Bhoj. kān, f. °ni, kanwā m. ʻ one -- eyed man ʼ, H. kān, °nā, G. kāṇũ; M. kāṇā ʻ one -- eyed, squint -- eyed ʼ; Si. kaṇa ʻ one -- eyed, blind ʼ. -- Pk. kāṇa -- ʻ full of holes ʼ, G. kāṇũ ʻ full of holes ʼ, n. ʻ hole ʼ (< ʻ empty eyehole ʼ? Cf. ã̄dhḷũ n. ʻ hole ʼ < andhala -- ).*kāṇiya -- ; *kāṇākṣa -- .Addenda: kāṇá -- : S.kcch. kāṇī f.adj. ʻ one -- eyed ʼ; WPah.kṭg. kaṇɔ ʻ blind in one eye ʼ, J. kāṇā; Md. kanu ʻ blind ʼ. *kāṇākṣa ʻ one -- eyed ʼ. [kāṇá -- , ákṣi -- ]Ko. kāṇso ʻ squint -- eyed ʼ.(CDIAL 3019, 3020)

Side A narrative is common to both tablets: arA 'spoked wheel' rebus: Ara 'brass'; eraka 'knave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS karabha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ib 'iron' PLUS karA 'crocodile' rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' PLUS one-eyed woman thwarting rearing tigers.

h489A

h489A h489B

h489BSlide 89 Plano convex molded tablet showing an individual spearing a water buffalo with one foot pressing the head down and one arm holding the tip of a horn. A gharial is depicted above the sacrifice scene and a figure seated in yogic position, wearing a horned headdress, looks on. The horned headdress has a branch with three prongs or leaves emerging from the center.

On the reverse (90),a female deity is battling two tigers and standing above an elephant. A single Indus script depicting a spoked wheel is above the head of the deity.

Material: terra cotta

Dimensions: 3.91 length, 1.5 to 1.62 cm width

Harappa, Lot 4651-01

Harappa Museum, H95-2486

Meadow and Kenoyer 1997

Dimensions: 3.91 length, 1.5 to 1.62 cm width

Harappa, Lot 4651-01

Harappa Museum, H95-2486

Meadow and Kenoyer 1997

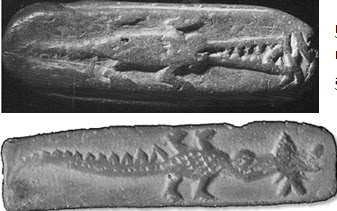

karA 'crocodile' Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

kamaDha 'penance' (Prakritam) Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'

kUtI 'twigs' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

muh 'face' Rebus: muhe 'ingot' (Santali)

Hieroglyph: kolsa = to kick the foot forward, the foot to come into contact with anything when walking or running; kolsa pasirkedan = I kicked it over (Santali.lex.)mēṛsa = v.a. toss, kick with the foot, hit with the tail (Santali)

Rebus: kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pancaloha’ (Ta.) •kolhe (iron-smelter; kolhuyo, jackal) kol, kollan-, kollar = blacksmith (Ta.lex.)•kol‘to kill’ (Ta.)

m0308, m0306, m0307 (Seal impressions of m0306 and m0307 are also shown side-by-side).

Hieroglyph 'thwarting' is signified by the glosses: hieroglyph: ‘impeding, hindering’: taṭu (Ta.) Rebus: dhatu ‘mineral’ (Santali) Ta. taṭu (-pp-, -tt) to hinder, stop, obstruct, forbid, prohibit, resist, dam, block up, partition off, curb, check, restrain, control, ward off, avert; n. hindering, checking, resisting; taṭuppu hindering, obstructing, resisting, restraint; Kur. ṭaṇḍnā to prevent, hinder, impede. Br. taḍ power to resist. (DEDR 3031)

कुंठणें [ kuṇṭhaṇēṃ ] v i (कुंठ S) To be stopped, detained, obstructed, arrested in progress (Marathi) Rebus: kuṇṭha munda (loha) 'hard iron (native metal)'.

Hieroglyph componens are: face in profile, one eye, circumfix (circle) and 6 curls of hair. Readings: muh 'face' rebus: muhA 'ingot'; கண்வட்டம் kaṇ-vaṭṭam 'eye PLUS circumfix' rebus: கண்வட்டம் kaṇ-vaṭṭan 'mint'; baTa 'six' rebus: baTa 'iron' bhaTa 'furnace' PLUS meD 'curl' rebus: meD 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic) Thus, the message is: mint with furnace for iron, copper. Tigers: dula 'two' rebus: dul 'cast metal' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' kolle 'blacksmith' kariba 'elephant trunk' ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ib 'iron' eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' arA 'spoke' rebus: Ara 'brass'.

கண்வட்டம் kaṇ-vaṭṭam , n. < id. +. 1. Range of vision, eye-sweep, full reach of one's observation;கண்பார்வைக்குட்பட்ட இடம். தங்கள் கண்வட்டத்திலே உண்டுடுத்துத்திரிகிற (ஈடு, 3, 5, 2). 2. Mint;நாணயசாலை.

aya khambhaṛā (Lahnda) rebus: aya 'iron' PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish fin'

Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage' (Kannada)== 'fish PLUS fin' rebus: ayas kammaTa 'metal mint'.

A one-eyed lady is shown to impede,check two rearing tigers (Side A of two-sided tablets). Same narrative appears on two tablets of Harappa. The hypertext of a woman/person thwarting two rearing tigers also occurs on four other seals with Indus Script inscriptions. The lady with one-eye is: kāṇī ʻone -- eyedʼ (feminine) rebus: kārṇī 'Supercargo'

The rebus readings of hypertext on Side A of the two tablets of Harappa are: kāṇī ʻone -- eyedʼ (feminine) rebus: kārṇī 'Supercargo' -- a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale. By denoting six curls on locks of hair, the word suggested is Ara 'six' rebus read together with kārṇī + Ara = kaṇṇahāra -- m. ʻhelmsman, sailorʼ. Thus, the hieroglyph of the six-locks of hair on woman signifies a 'helmsman + Supercargo'.

She is thwarting two rearing tigers: dula 'two' rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' PLUS taTu 'thwart' rebus: dhatu 'mineral'. Thus, 'mineral smelter'. Together the hieroglyph-multiplex or hypertext of a woman thwarting two tigers signifies: 'helmsman, supercargo of metal casting products from mineral smelter'.

What minerals? The top hieroglyph is a spoked wheel; the bottom hieroglyph is an elephant. They signify copper and iron minerals. eraka 'nave of wheel'rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' karibha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ib 'iron.

Thus the entire narrative on Side A of the Harappa tablets signifies 'helmsnan, supercargo of products from copper and iron mineral smelters.

What minerals? The top hieroglyph is a spoked wheel; the bottom hieroglyph is an elephant. They signify copper and iron minerals. eraka 'nave of wheel'rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' karibha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ib 'iron.

Thus the entire narrative on Side A of the Harappa tablets signifies 'helmsnan, supercargo of products from copper and iron mineral smelters.

Glyph: ‘woman’: kola ‘woman’ (Nahali). Rebus kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil)

Glyph: ‘impeding, hindering’: taṭu (Ta.) Rebus: dhatu ‘mineral’ (Santali) Ta. taṭu (-pp-, -tt) to hinder, stop, obstruct, forbid, prohibit, resist, dam, block up, partition off, curb, check, restrain, control, ward off, avert; n. hindering, checking, resisting; taṭuppu hindering, obstructing, resisting, restraint; Kur. ṭaṇḍnā to prevent, hinder, impede. Br. taḍ power to resist. (DEDR 3031) baTa 'six' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'. Alternative: Ta. āṟu six; aṟu-patu sixty; aṟu-nūṟu 600; aṟumai six; aṟuvar six persons; avv-āṟu by sixes. Ma. āṟu six; aṟu-patu sixty; aṟu-nnūṟu 600; aṟuvar six persons. Ko. a·r six; ar vat sixty; a·r nu·r 600;ar va·ṇy six pa·ṇy measures. To. o·ṟ six; pa·ṟ sixteen; aṟoQ sixty; o·ṟ nu·ṟ 600; aṟ xwa·w six kwa·x measures. Ka. āṟu six; aṟa-vattu, aṟu-vattu, ar-vattu sixty; aṟu-nūṟu, āṟu-nūṟu 600; aṟuvar, ārvarusix persons. Koḍ. a·rï six;

a·rane sixth; aru-vadï sixty; a·r-nu·rï 600. Tu. āji six; ājane sixth; ajipa, ajippa, ājipa, ājpa sixty. Te. āṟu six; āṟuguru, āṟuvuru six persons; aṟu-vadi, aruvai, aravai sixty;aṟuvaṇḍru sixty persons. Kol. (SR. Kin., Haig) ār six; (SR.) ārgur six persons. Nk. (Ch.) sādi six. Go. (Tr.) sāṟung six; sārk six each; (W.) sārūṅg, (Pat.) harung, (M.) ārū, hārūṃ, (L.) hārūṅg six; (Y.)sārvir, (G.) sārvur, (Mu.) hārvur, hāruṛ, (Ma.) ār̥vur six (masc.) (Voc. 3372); sarne (W.) fourth day after tomorrow, (Ph.) sixth day (Voc. 3344); Kui (Letchmajee) sajgi six; sāja pattu six times twelve dozen (= 864); (Friend-Pereira; Gūmsar dialect) saj six; sajgi six things; (K.) hāja six (DEDR 2485) Together, the reading of the hypertext of one-eyed PLUS six hair-knots is: kArNI-Ara, i.e. kaṇṇahāra -- m. ʻ helmsman, sailor ʼ (Prakrtam): karṇadhāra m. ʻ helmsman ʼ Suśr. [kárṇa -- , dhāra -- 1 ] Pa. kaṇṇadhāra -- m. ʻ helmsman ʼ; Pk. kaṇṇahāra -- m. ʻ helmsman, sailor ʼ; H. kanahār m. ʻ helmsman, fisherman ʼ.(CDIAL 2836) PLUS मेढा [mēḍhā] A twist rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meD 'iron' Thus, the narrative hypertext signifies helmsman carrying cargo of smelted iron.

काण [p= 269,1] mf(आ)n. (etym. doubtful ; g. कडारा*दि) one-eyed , monoculous (अक्ष्णा काणः , blind of one eye Comm. on Pa1n2. 2-1 , 30 and 3 , 20) RV. x , 155 , 1 AV. xii , 4 , 3 TS. ii , 5 , 1 , 7 Mn. MBh." having only one loop or ring " and " one-eyed " Pan5cat. Rebus: kārṇī m. ʻ prime minister, supercargo of a ship ʼ Pa. usu -- kāraṇika -- m. ʻ arrow -- maker ʼ; Pk. kāraṇiya -- m. ʻ teacher of Nyāya ʼ; S. kāriṇī m. ʻ guardian, heir ʼ; N. kārani ʻ abettor in crime ʼ; M. kārṇī m. ʻ prime minister, supercargo of a ship ʼ, kul -- karṇī m. ʻ village accountant ʼ.(CDIAL 3058)

Side A narrative is common to both tablets: arA 'spoked wheel' rebus: Ara 'brass'; eraka 'knave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS karabha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ib 'iron' PLUS karA 'crocodile' rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' PLUS one-eyed woman thwarting rearing tigers.

m0308 Seal 1 Hieroglyph: śrēṣṭrī 'ladder' Rebus: seṭh ʻ head of a guild, sangaDa 'lathe, portable brazier' rebus: sangarh 'fortification' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' (That is, guild workshop in a fortification) ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' khaNDa 'arrow' rebus: khaNDa 'implements'. Thus the hypertext signifies; metal implements from a workshop (in) fortification. The seal is that of a guild-master and helmsman PLUS supercargo (responsible for the shipment/cargo).

m0307 Seal 2 & seal impression: Two part message: Part 1: kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze' sangaDa 'lathe, portable brazier' rebus: sangarh 'fortification' kanka, karNika 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karnika 'scribe, engraver' muh 'ingot' dhatu 'claws of crab' rebus: dhatu 'minerals' Part 2: kanka, karNika 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karnika 'scribe, engraver' plus kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge'. The seal is that of a helmsman PLUS supercargo responsible for cargo of ingots, minerals and products from smithy/forge.

m0306 Seal 3 and impression: dhatu 'claws of crab' rebus: dhatu 'minerals' dhāḷ 'a slope'; 'inclination' rebus: dhALako 'ingot' PLUS kANDa 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implements' dula 'two' rebus: dul 'cast metal' kuTil 'curve' rebus: kuTila 'bronze' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' kanka, karNika 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karnika 'scribe, engraver' . The seal is that of a helmsman of bronze cargo of metal castings, ingots and implements

Indus Script seals showing a lady thwarting, impeding, checking two rearing tigers.

Mohenjo-daro seal. Mohenjo-daro, ca. 2500 BCE Asko Parpola writes: "The 'contest' motif is one of the most convincing and widely accepted parallels between Harappan and Near Eastern glyptic art. A considerable number of Harappan seals depict a manly hero, each hand grasping a tiger by the throat. In Mesopotamian art, the fight with lions and / or bulls is the most popular motif. The Harappan substitution of tigers for lions merely reconciles the scene with the fauna of the Indus Valley ... The six dots around the head of the Harappan hero are a significant detail, since they may correspond to the six locks of hair characteristic of the Mesopotamian hero, from Jemdet Nasr to Akkadian times," (Deciphering the Indus Script, pp. 246-7).

Mark Kenoyer writes that "discoveries of this motif on seals from Mohenjo-daro definitely show a male figure and most scholars have assumed some connection with the carved seals from Mesopotamia that illustrate episodes from the famous Gilgamesh epic. The Mesopotamian motifs show lions being strangled by a hero, whereas the Indus narratives render tigers being strangled by a figure, sometime clearly males, sometimes ambiguous or possibly female. This motif of a hero or heroine grappling with two wild animals could have been created independently for similar events that may have occurred in Mesopotamia as well as the Indus valley," ( Ancient Cities, p. 114).

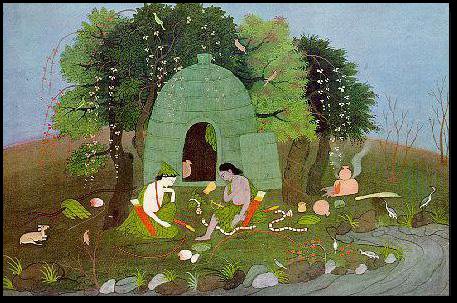

h180: Three-sided prism tablet from Harappa also includes a rearing-set of tigers narrative

ext 4304 Text on both sides of the tablet Hieroglyphs read rebus from r. to l.: koDi 'flag' rebus: koD 'workshop' gaNDa 'four' rebus: kanda 'fire-altar' kanda kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: kanda 'fire-altar' karNI 'supercargo' karNika 'scribe' khaNDa 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'i9mplements' ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin' kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smith, forge' kuTi 'water-carrier' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'.

Two tigers: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter'.

h180A

h180B4304 Tablet in bas-relief h180a Pict-106: Nude female figure upside down with thighs drawn apart and crab (?) issuing from her womb; two tigers standing face to face rearing on their hindlegs at L.

h180b

Pict-92: Man armed with a sickle-shaped weapon on his right hand and a cakra (?) on his left hand, facing a seated woman with disheveled hair and upraised arms.

A person carrying a sickle-shaped weapon and a wheel on his bands faces a woman with disheveled hair and upraised arm. kuṭhāru ‘armourer’ (Sanskrit) salae sapae = untangled, combed out, hair hanging loose (Santali.lex.) Rebus: sal workshop (Santali) The glyptic composition is decoded as kuṭhāru sal‘armourer workshop.’ eṛaka 'upraised arm' (Tamil). Rebus: eraka = copper (Kannada) Thus, the entire composition of these glyphic elements relate to an armourer’s copper workshop. Vikalpa:

<raca>(D) {ADJ} ``^dishevelled'' (Munda) rasāṇẽ n. ʻglowing embersʼ (Marathi). rabca ‘dishevelled’ Rebus: రాచrāca (adj.) Pertaining to a stone (ore) (bica).

The descriptive glyphics indicates that the smelting furnace is for bica, stone (ore). This is distinquished from sand ore.

![]() The object between the outspread legs of the woman lying upside down is comparable orthography of a crocodile holding fiish in its jaws shown on tablets h705B and h172B. The snout of the crocodile is shown in copulation with the lying-in woman (as seen from the enlarged portion of h180 Harappa tablet).

The object between the outspread legs of the woman lying upside down is comparable orthography of a crocodile holding fiish in its jaws shown on tablets h705B and h172B. The snout of the crocodile is shown in copulation with the lying-in woman (as seen from the enlarged portion of h180 Harappa tablet).

Glosses: Indian sprachbund

h180b

Pict-92: Man armed with a sickle-shaped weapon on his right hand and a cakra (?) on his left hand, facing a seated woman with disheveled hair and upraised arms.

A person carrying a sickle-shaped weapon and a wheel on his bands faces a woman with disheveled hair and upraised arm. kuṭhāru ‘armourer’ (Sanskrit) salae sapae = untangled, combed out, hair hanging loose (Santali.lex.) Rebus: sal workshop (Santali) The glyptic composition is decoded as kuṭhāru sal‘armourer workshop.’ eṛaka 'upraised arm' (Tamil). Rebus: eraka = copper (Kannada) Thus, the entire composition of these glyphic elements relate to an armourer’s copper workshop. Vikalpa:

<raca>(D) {ADJ} ``^dishevelled'' (Munda) rasāṇẽ n. ʻglowing embersʼ (Marathi). rabca ‘dishevelled’ Rebus: రాచrāca (adj.) Pertaining to a stone (ore) (bica).

The descriptive glyphics indicates that the smelting furnace is for bica, stone (ore). This is distinquished from sand ore.

The object between the outspread legs of the woman lying upside down is comparable orthography of a crocodile holding fiish in its jaws shown on tablets h705B and h172B. The snout of the crocodile is shown in copulation with the lying-in woman (as seen from the enlarged portion of h180 Harappa tablet).

The object between the outspread legs of the woman lying upside down is comparable orthography of a crocodile holding fiish in its jaws shown on tablets h705B and h172B. The snout of the crocodile is shown in copulation with the lying-in woman (as seen from the enlarged portion of h180 Harappa tablet).kola ‘woman’; rebus: kol ‘iron’. kola ‘blacksmith’ (Ka.); kollë ‘blacksmith’ (Koḍ) kuThi 'vagina' rebus: kuThi 'smnelter' karA 'crocodile' rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' khamDa 'copulation' rebus: kammaTa 'coin, mint'

The glyphic elements shown on the tablet are: copulation, vagina, crocodile.

Gyphic: ‘copulation’: kamḍa, khamḍa 'copulation' (Santali) Rebus: kammaṭi a coiner (Ka.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Ta.) kammaṭa = mint, gold furnace (Te.) Vikalpa: kaṇḍa ‘stone (ore)’. Glyph: vagina: kuṭhi ‘vagina’; rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’. The descriptive glyphics indicates that the smelting furnace is for stone (ore). This is distinquished from sand ore. Glyph: ‘crocodile’: karā ‘crocodile’. Rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’. kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Te.) Rebus: kāruvu ‘artisan’

kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Te.) mosale ‘wild crocodile or alligator. S. ghaṛyālu m. ʻ long — snouted porpoise ʼ; N. ghaṛiyāl ʻ crocodile’ (Telugu)ʼ; A. B. ghãṛiyāl ʻ alligator ʼ, Or. Ghaṛiāḷa, H. ghaṛyāl, ghariār m. (CDIAL 4422) கரவு² karavu

, n. < கரா. cf. grāha. Alligator; முதலை. கரவார்தடம் (திவ். திருவாய். 8, 9, 9).

கரா karā , n. prob. grāha. 1. A species of alligator; முதலை. கராவதன் காலினைக்கதுவ (திவ். பெரியதி. 2, 3, 9). 2. Male alligator; ஆண்முதலை. (பிங்.) கராம் karām , n. prob. grāha. 1. A species of alligator; முதலைவகை. முதலையு மிடங்கருங் கராமும் (குறிஞ்சிப். 257). 2. Male alligator; ஆண் முதலை. (திவா.)கரவா karavā , n. A sea-fish of vermilion colour, Upeneus cinnabarinus; கடல்மீன்வகை. Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)kuṭhi = pubes. kola ‘foetus’ [Glyph of a foetus emerging from pudendum muliebre on a Harappa tablet.] kuṭhi = the pubes (lower down than paṇḍe) (Santali) kuṭhi = the womb, the female sexual organ; sorrege kuṭhi menaktaea, tale tale gidrakoa lit. her womb is near, she gets children continually (H. koṭhī, the womb) (Santali.Bodding) kōṣṭha = anyone of the large viscera (MBh.); koṭṭha = stomach (Pali.Pkt.); kuṭṭha (Pkt.); koṭhī heart, breast (L.); koṭṭhā, koṭhā belly (P.); koṭho (G.); koṭhā (M.)(CDIAL 3545). kottha pertaining to the belly (Pkt.); kothā corpulent (Or.)(CDIAL 3510). koṭho [Skt. koṣṭha inner part] the stomach, the belly (Gujarat) kūti = pudendum muliebre (Ta.); posteriors, membrum muliebre (Ma.); ku.0y anus, region of buttocks in general (To.); kūdi = anus, posteriors, membrum muliebre (Tu.)(DEDR 188). kūṭu = hip (Tu.); kuṭa = thigh (Pe.); kuṭe id. (Mand.); kūṭi hip (Kui)(DEDR 1885). gūde prolapsus of the anus (Ka.Tu.); gūda, gudda id. (Te.)(DEDR 1891).

Glosses: Indian sprachbund

kāru ‘crocodile’ (Telugu). Rebus: artisan (Marathi) Rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri)

kola ‘tiger’ Rebus: kol ‘working in iron’.

Heraka ‘spy’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’. khōṇḍa ‘leafless tree’ (Marathi). Rebus: kõdār’turner’ (Bengali) dhamkara 'leafless tree' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'

Looking back: krammara ‘look back’ Rebus: kamar ‘smith, artisan’.

Hieroglyph: koḍiya 'young bull' rebus: koṭiya 'dhow, seafaring vessel'.

koḍe ‘young bull’ (Telugu) खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) ayakāra ‘ironsmith’ (Pali)[fish = aya (G.); crocodile = kāru (Te.)] baṭṭai quail (N.Santali) Rebus: bhaṭa = an oven, kiln, furnace (Santali)

ayo 'fish' Rebus: ayas 'metal'. kaṇḍa 'arrow' Rebus: khāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. ayaskāṇḍa is a compounde word attested in Panini. The compound or glyphs of fish + arrow may denote metalware tools, pots and pans.kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron, alloy of 5 metals - pancaloha'. ibha 'elephant' Rebus ibbo 'merchant'; ib ‘iron'. Alternative: కరటి [ karaṭi ] karaṭi. [Skt.] n. An elephant. ఏనుగు (Telugu) Rebus: kharādī ‘ turner’ (Gujarati) kāṇḍa 'rhimpceros' Rebus: khāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. The text on h0489 tablet: loa 'ficus religiosa' Rebus: loh 'copper'. kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. Thus the display of the metalware catalog includes the technological competence to work with minerals, metals and alloys and produce tools, pots and pans. The persons involved are krammara 'turn back' Rebus: kamar 'smiths, artisans'. kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron, working in pancaloha alloys'. పంచలోహము pancha-lōnamu. n. A mixed metal, composed of five ingredients, viz., copper, zinc, tin, lead, and iron (Telugu). Thus, when five svastika hieroglyphs are depicted, the depiction is of satthiya 'svastika' Rebus: satthiya 'zinc' and the totality of 5 alloying metals of copper, zinc, tin, lead and iron.

Glyph: Animals in procession: खांडा [khāṇḍā] A flock (of sheep or goats) (Marathi) கண்டி¹ kaṇṭi Flock, herd (Tamil) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’.

Hieroglyph: heraka ‘spy’. Rebus: eraka, arka 'copper, gold'; eraka 'moltencast, metal infusion'; era ‘copper’. हेरक S through e_ rnū ʻ to look at ʼ (bhal. hirāṇū ʻ to show ʼ), pāḍ. hēraṇ, paṅ. hēṇā, cur. hērnā, Ku. herṇo, N. hernu, A. heriba, B. herā, Or. heribā (caus. herāibā), Mth. herab, OAw. heraï, H. hernā; G. hervũ ʻ to spy ʼ, M. herṇẽ. 2. Pk. hēria -- m. ʻ spy ʼ; Kal. (Leitner) "hériu"ʻ spy ʼ; G. herɔ m. ʻ spy ʼ, herũ n. ʻ spying ʼ. Addenda: *hērati: WPah.kṭg. (Wkc.) hèrnõ, kc. erno ʻ observe ʼ; Garh. hernu ʻ to look' (CDIAL 14165) Ko. er uk- (uky-) to play 'peeping tom'. Kui ēra (ēri-) to spy, scout; n. spying, scouting; pl action ērka (ērki-). ? Kuwi (S.) hēnai to scout; hēri kiyali to see; (Su. P.) hēnḍ- (hēṭ-) id. Kur. ērnā (īryas) to see, look, look at, look after, look for, wait for, examine, try; ērta'ānā to let see, show; ērānakhrnā to look at one another. Malt. ére to see, behold, observe; érye to peep, spy. Cf. 892 Kur. ēthrnā. / Cf. Skt. heraka- spy, Pkt. her- to look at or for, and many NIA verbs; Turner, CDIAL, no. 14165(DEDR 903)

కారుమొసలి a wild crocodile or alligator (Telugu).

Rebus: khār ‘blacksmith’ khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार ; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन् , which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-basta खार-बस््त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith. -büṭhü -; । लोहकारभित्तिः f. the wall of a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -bāy -बाय् । लोहकारपत्नी f. a blacksmith's wife (Gr.Gr. 34). -dŏkuru -; । लोहकारायोघनः m. a blacksmith's hammer, a sledge-hammer. -gȧji -ग&above;जि&below; or । लोहकारचुल्लिः f. a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -hāl -हाल् । लोहकारकन्दुः f. (sg. dat. -höjü ), a blacksmith's smelting furnace; cf. hāl 5. -kūrü; । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter. -koṭu; । लोहकारपुत्रः m. the son of a blacksmith, esp. a skilful son, who can work at the same profession. -küṭü -क&above;टू&below; । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter, esp. one who has the virtues and qualities properly belonging to her father's profession or caste. -më˘ʦü 1 ; । लोहकारमृत्तिका f. (for 2, see [khāra 3] ), 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore. -nĕcyuwu -न्यचिवु&below; । लोहकारात्मजः m. a blacksmith's son. -nay -नय् । लोहकारनालिका f. (for khāranay 2, see [khārun] ), the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting. -ʦañĕ -च्&dotbelow;ञ । लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wān वान् । लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 3). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि ), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil.

One side of a molded tablet m 492 Mohenjo-daro (DK 8120, NMI 151. National Museum, Delhi. A person places his foot on the horns of a buffalo while spearing it in front of a cobra hood.

Hieroglyph: kolsa = to kick the foot forward, the foot to come into contact with anything when walking or running; kolsa pasirkedan = I kicked it over (Santali.lex.)mēṛsa = v.a. toss, kick with the foot, hit with the tail (Santali)

kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pancaloha’ (Ta.) •kolhe (iron-smelter; kolhuyo, jackal) kol, kollan-, kollar = blacksmith (Ta.lex.)•kol‘to kill’ (Ta.)

kulā 'hood of snake' rebus: kol 'working in iron'

Hieroglyph: rã̄go ʻ buffalo bull ʼ

Rebus: Pk. raṅga 'tin' P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼOr. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼraṅgaada -- m. ʻ borax ʼ lex.Kho. (Lor.) ruṅ ʻ saline ground with white efflorescence, salt in earth ʼ *raṅgapattra ʻ tinfoil ʼ. [raṅga -- 3, páttra -- ]B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.

paTa 'hood of serpent' Rebus: padanu 'sharpness of weapon' (Telugu)

Rebus: Pk. raṅga 'tin' P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼOr. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼraṅgaada -- m. ʻ borax ʼ lex.Kho. (Lor.) ruṅ ʻ saline ground with white efflorescence, salt in earth ʼ *raṅgapattra ʻ tinfoil ʼ. [raṅga -- 3, páttra -- ]B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.

paTa 'hood of serpent' Rebus: padanu 'sharpness of weapon' (Telugu)

Hieroglyph: kunta1 ʻ spear ʼ. 2. *kōnta -- . [Perh. ← Gk. konto/ s ʻ spear ʼ EWA i 229]1. Pk. kuṁta -- m. ʻ spear ʼ; S. kundu m. ʻ spike of a top ʼ, °dī f. ʻ spike at the bottom of a stick ʼ, °diṛī, °dirī f. ʻ spike of a spear or stick ʼ; Si. kutu ʻ lance ʼ.2. Pa. konta -- m. ʻ standard ʼ; Pk. koṁta -- m. ʻ spear ʼ; H. kõt m. (f.?) ʻ spear, dart ʼ; -- Si. kota ʻ spear, spire, standard ʼ perh. ← Pa.(CDIAL 3289)

Rebus: kuṇṭha munda (loha) 'hard iron (native metal)'

Allograph: कुंठणें [ kuṇṭhaṇēṃ ] v i (कुंठ S) To be stopped, detained, obstructed, arrested in progress (Marathi) Rebus: kuṇṭha munda (loha) 'hard iron (native metal)'.

Allograph: कुंठणें [ kuṇṭhaṇēṃ ] v i (

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

July 19, 2016

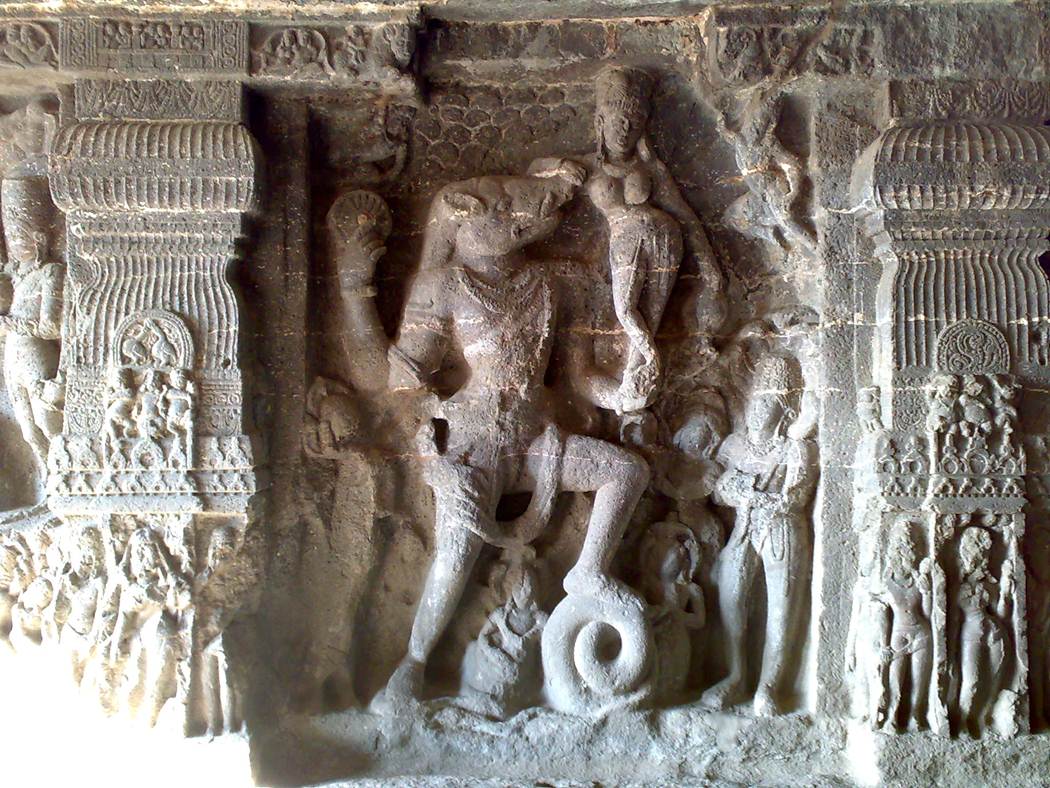

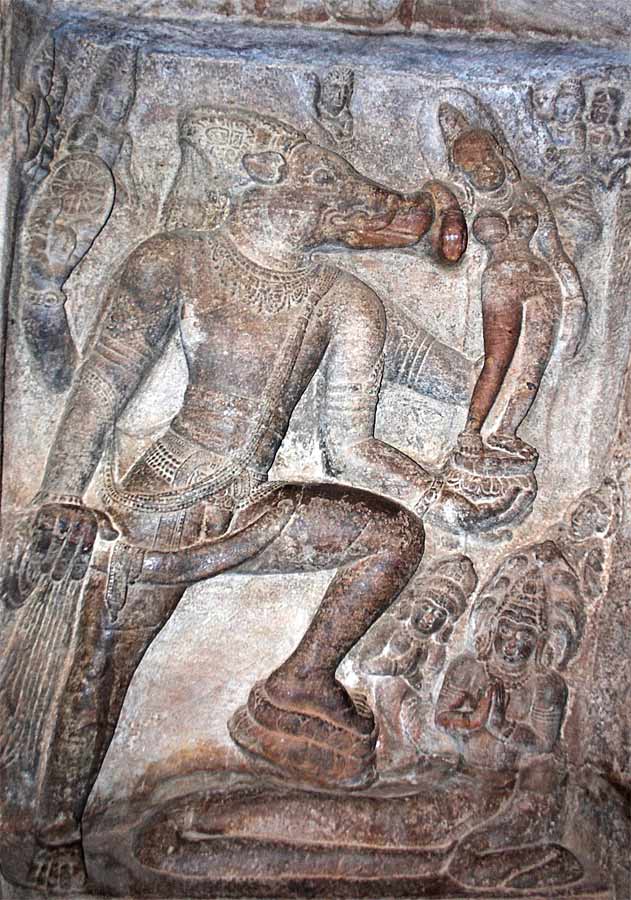

Sarasvati on the snout (cashAla) of Varaha. caSAla is a metallurgical knowledge system of carburization of metal using godhuma fumes to inject carbon into the metal to harden it.. See:

Sarasvati on the snout (cashAla) of Varaha. caSAla is a metallurgical knowledge system of carburization of metal using godhuma fumes to inject carbon into the metal to harden it.. See:

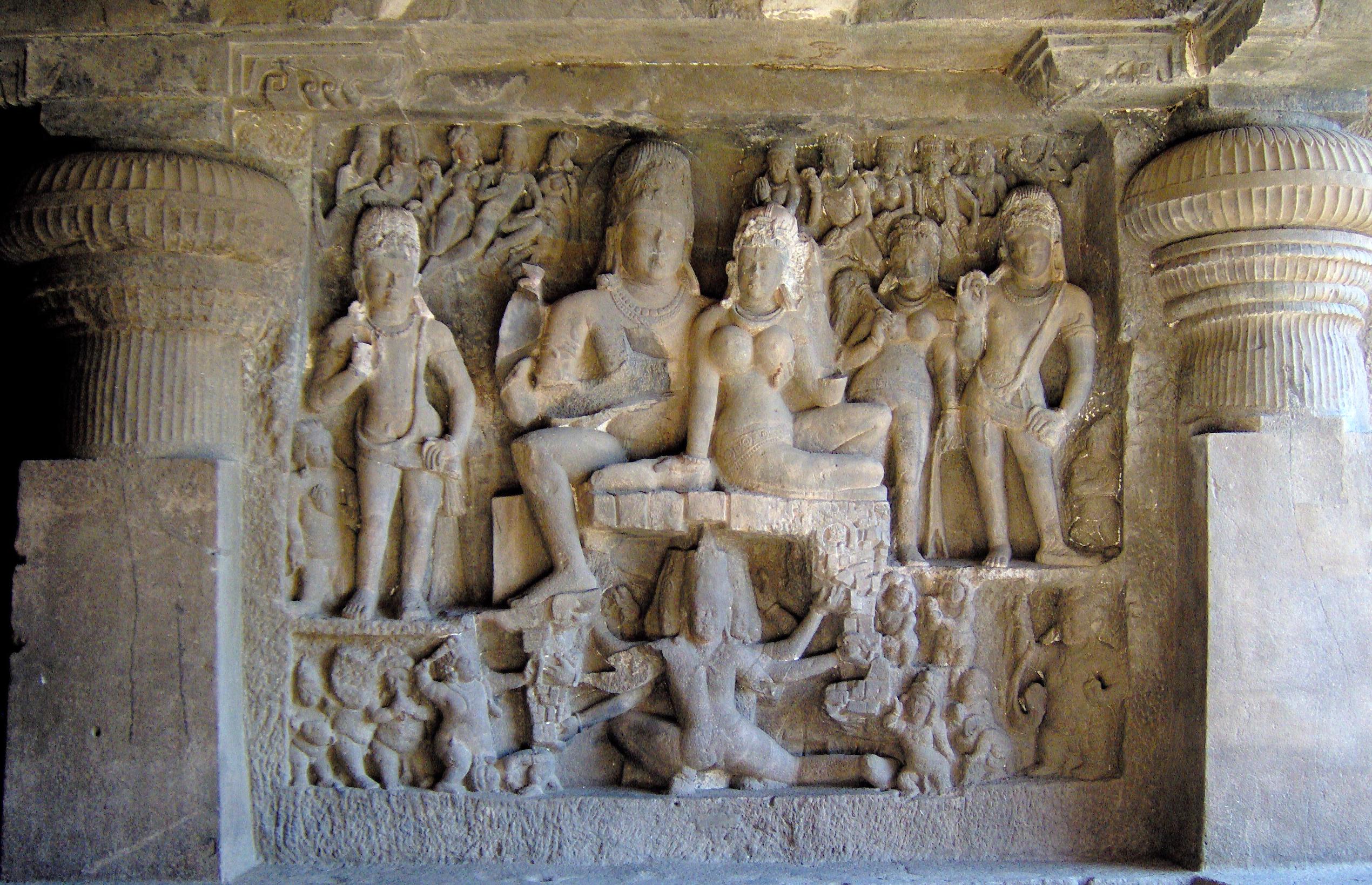

Varaha. Badami.

Varaha. Badami.

Pralaya Varahantha temple situated at Kalahalli, Krishnarajpet taluk. Height 15 ft.

Pralaya Varahantha temple situated at Kalahalli, Krishnarajpet taluk. Height 15 ft. Bhu Varaha, Belgaum

Bhu Varaha, Belgaum

Varaha, Halebidu

Varaha, Halebidu

Varaha, Simhachalam temple, Vishakapatnam

Varaha, Simhachalam temple, Vishakapatnam Varaha. Indian Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Varaha. Indian Asian Art Museum, San Francisco. Varaha, Tirumala

Varaha, Tirumala

Drs Gerda Theuns-de Boer is an art historian and Project Manager of the Photographic Database on Asian Art and Archaeology, Kern Institute, Leiden University.

Drs Gerda Theuns-de Boer is an art historian and Project Manager of the Photographic Database on Asian Art and Archaeology, Kern Institute, Leiden University.

Linteau Ramayana Musee Guimet.

Linteau Ramayana Musee Guimet.

Terracotta Panel ca. 5th century, from Bhitargaon

Terracotta Panel ca. 5th century, from Bhitargaon

The log defines Bharata Rashtram: Asetu Himachalam.

The log defines Bharata Rashtram: Asetu Himachalam.

Ramayana Preah Ko, Angkor Temples, Cambodia

Ramayana Preah Ko, Angkor Temples, Cambodia Linteau Khmer, Guimet.

Linteau Khmer, Guimet.

.jpg?itok=SzxHAdqn)

Urdu copy of Ramacharitamanas, 1910

Urdu copy of Ramacharitamanas, 1910

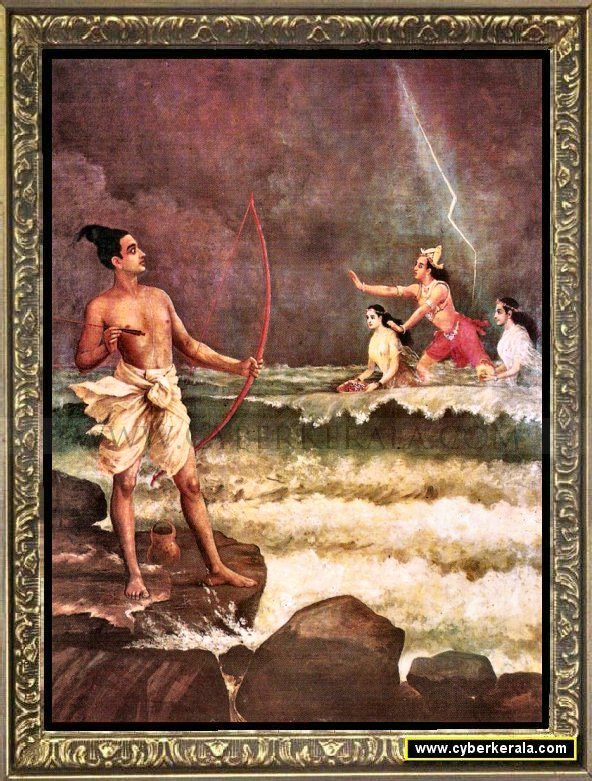

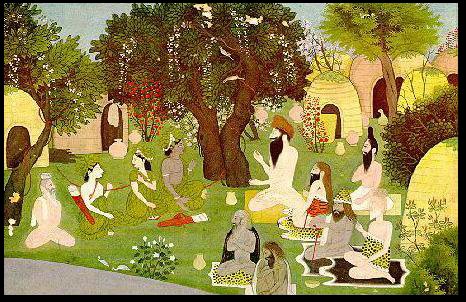

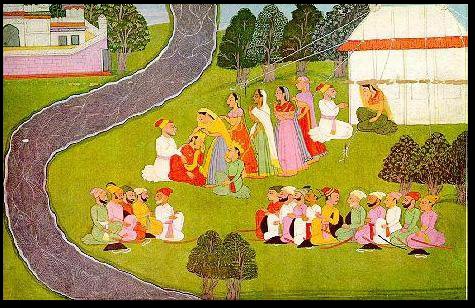

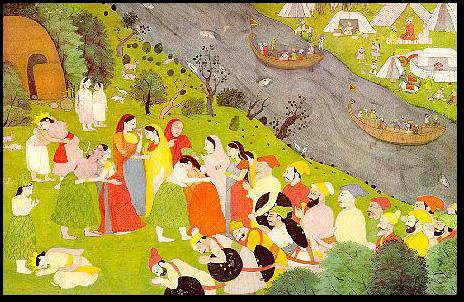

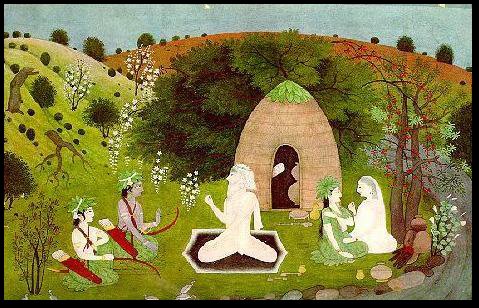

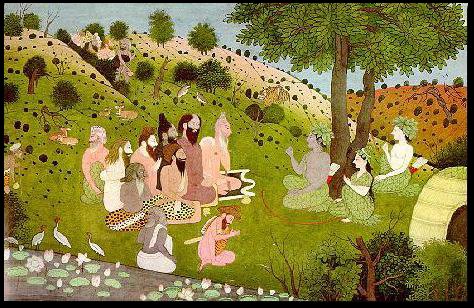

Meeting of Rama and Parasurama. Sages.

Meeting of Rama and Parasurama. Sages.

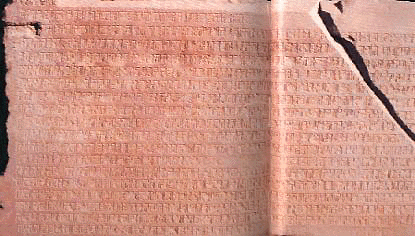

Ruins from Ayodhya temple at Babri Mosque.

Ruins from Ayodhya temple at Babri Mosque.

Ruis of Dwarapalaka, Ayodhya temple found at Babri Mosque

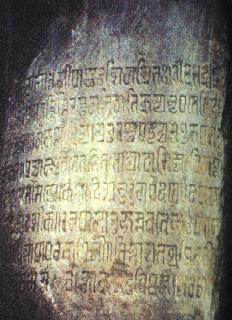

Ruis of Dwarapalaka, Ayodhya temple found at Babri Mosque 12th cent. Hari-Vishnu inscription."

12th cent. Hari-Vishnu inscription."

Vishnu as Trivikrama. Mahabalipuram.

Vishnu as Trivikrama. Mahabalipuram. Bronze Vishnu statue. Vamana Avatar.

Bronze Vishnu statue. Vamana Avatar.

Halebidu. Beluru.

Halebidu. Beluru.

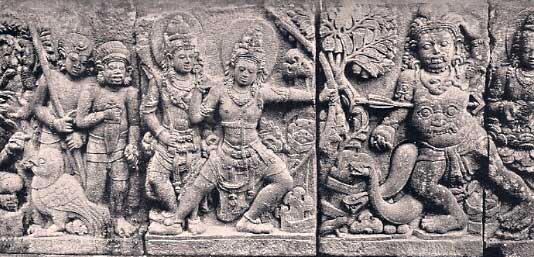

Parambanan, Indonesia. Ramayana scenes.

Parambanan, Indonesia. Ramayana scenes.

Sri Sita Ramachandra Swamy, Bhadrachalam, Andhra Pradesh..

Sri Sita Ramachandra Swamy, Bhadrachalam, Andhra Pradesh.. Pattabhirama temple, Hampi.

Pattabhirama temple, Hampi.

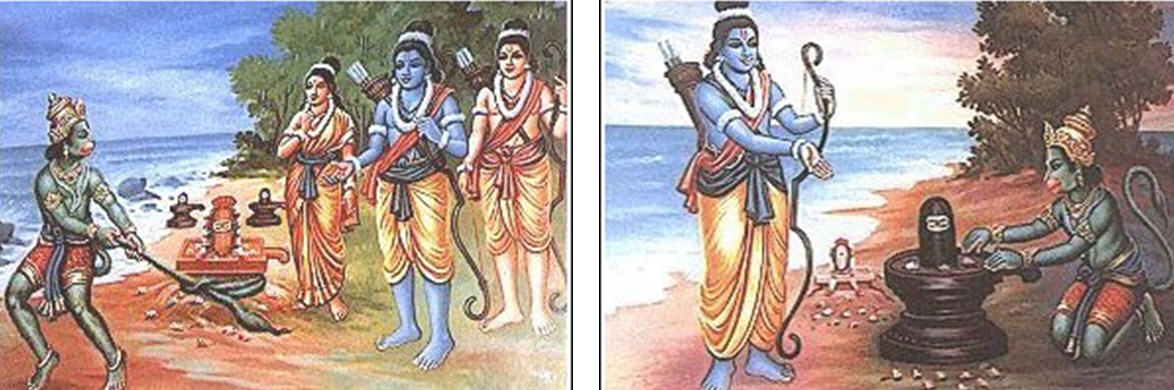

Sivalingas at Rameshwaram installed by Sri Rama, Sita, Hanuman.

Sivalingas at Rameshwaram installed by Sri Rama, Sita, Hanuman.

Halebid.

Halebid.

Hampi Ramayana scenes.

Hampi Ramayana scenes.

Vanaras.Hoysaleshwara temple, Halebid

Vanaras.Hoysaleshwara temple, Halebid Halebid. Rama at war.

Halebid. Rama at war.

Sailing boat (Mohenjodaro Polished painting, 3000 BCE, National Museum, New Delhi)

Sailing boat (Mohenjodaro Polished painting, 3000 BCE, National Museum, New Delhi)

13th century. Rudra.

13th century. Rudra. Siva. Musee Guimet.

Siva. Musee Guimet. Aditya flanked by Brahman and Rudra. Note Rudra and Brahma flanking Surya (Aditya).just above the kirITam (crown). It is notable that a makara is shown as a vAhana of Rudra.

Aditya flanked by Brahman and Rudra. Note Rudra and Brahma flanking Surya (Aditya).just above the kirITam (crown). It is notable that a makara is shown as a vAhana of Rudra..jpg/800px-Shiva_(Mus%C3%A9e_Guimet).jpg)

Rudra

Rudra

Coin found in Thailand. ayo-kammaTa on elephant Reverse: lamp & horsehead

Coin found in Thailand. ayo-kammaTa on elephant Reverse: lamp & horsehead

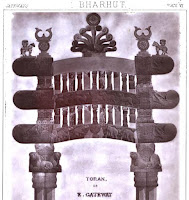

Srivatsa atop Sanchi torana.

Srivatsa atop Sanchi torana.

} The nun had committed the cruel act out of fear of humiliation and possible expulsion from her ascetic life if Sr Abhaya reported what she saw to the higher authorities of the Church, the CBI said.

} The nun had committed the cruel act out of fear of humiliation and possible expulsion from her ascetic life if Sr Abhaya reported what she saw to the higher authorities of the Church, the CBI said.

Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.

Gold fillet. Lathe + portable furnace

Gold fillet. Lathe + portable furnace

Bharhut. Sculptural frieze venerating 'srivatsa'.

Bharhut. Sculptural frieze venerating 'srivatsa'.