In addition to the focused, time-bound excavations – suggested by Dr. Jagmohan -- from among 2000+ archaeological sites (over 80%) on Sarasvati River basin (to be selected by ASI from the Gazetteer of over 2600 sites included in Gregory Possehl’s 1999 work Indus Age, the Beginnings), multi-disciplinary studies on aspects of the civilization include specific studies/projects such as the following:

1. River channel provenance studies, plate tectonics and glaciology studies

2. Material resources, trade & cultural framework: Marine archaeology (linking Sarasvati river basin to Persian Gulf and sites along the Indian Ocean coastline) and marine activities of Bharatiya civilization; herbals and ayurveda traditions, art and cultural traditions (lapidary work with semiprecious stones such as carnelian, s’ankha shells)

3. Archaeo-metallurgy (Ancient India’s contributions to the Bronze Age Revolution),

4. Water management

5. Formation and evolution of Bharatiya languages from the roots of Sarasvati civilization speakers who venerated VAgdevi (Sarasvati) in the Rashtrii Suktam of Rigveda.

6. Dissemination of information and peoples’ participation

1. River channel provenance studies, plate tectonics and glaciology studies

The greatest water tower of the world, the Himalayan ranges stretch from Hanoi (Vietnam) to Teheran (Iran)

The ongoing northward thrust of Indian plate (at about 6 cm per year) and lifting up the Eurasian plate (about 1 cm per year) are an extraordinary geophysical reality of the Himalayan ranges. which constitute the largest water tower in the globe. The recurring plate tectonic events have impacted river migrations and changes to hydrological flows of perennial river systems of Bharatam. This reality calls for multi-disciplinary studies related to glaciology (formation/movements of glaciers) and river (glacial flow) migrations caused by plate tectonics. (as evidenced near Ropar related to Sutlej river and near Paontasaheb/Rakhigarhi related to Yamuna river which was a tributary of River Sarasvati) See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/01/sarasvati-was-himalayan-river-ks.htmlSarasvati was a Himalayan River -- KS Valdiya (2013) rejects Giosan et al arguments

Current Science, Vol. 104, No. 1,10 January 2013, Pages 42 to 54. In this paper, Dr.Valdiya rgues fo a provenance study: “There is, however, no denying that a comprehensive provenance sudy is required to dispel all doubts about the source of the sediment that fill the channels and the floodplain of the Sarasvati system.” (opcit., Current Science,p.50). Such a provenance study should include glaciologists, seismologists, geologists, archaeologists.

2. Material resources, trade & cultural framework

A striking feature of over 2000 archaeological sites on Sarasvati basin in Bharatam is that there are indications of maritime trade activity across the Persian Gulf. Over 2000 Persian Gulf/Dilmun seals with Indus Script have been found. Another remarkable feature is the clustering of sites with Bronze Age industrial activity in sites close to the Rann of Kutch (en route to Persian Gulf).

In the context of marine archaeological initiatives at Dwaraka, it may be appropriate to conduct further marine archaeological studies in the Indian Ocean along the Rann of Kutch, Saurashtra and western coastlines of Bharatam to unravel the maritime activities of the civilization.

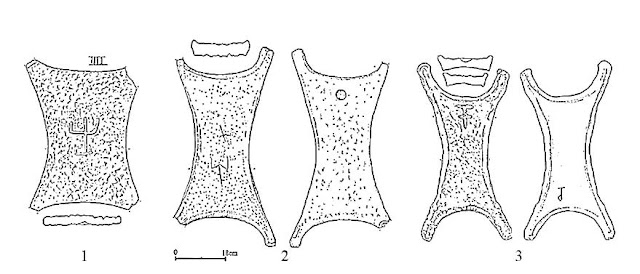

3. Archaeo-metallurgy (Ancient India’s contributions to the Bronze Age Revolution)

The recent discovery by ASI at a site called Bijnor (near Anupgarh) on the banks of River Sarasvati points to two features: 1. Presence of yajna kunda in the Vedic tradition evidenced by an octagonal pillar indicative of Soma yaga as prescribed in ancient Vedic texts) and 2. Metalwork activity and presence of a seal attesting to mature period of the civilization (perhaps dated to ca. 2500 BCE). Further archaeo-metallurgical studies are needed to map 1) the resources from Khetri mines which seem to have sustained sites like Bijnor, Kalibangan, Karanpura (see note below) on Sarasvati River Basin and 2) nature of contributions made by Bharatiyas to Bronze Age Revolution, with particular reference to mleccha ‘copper’.

म्लेच्छा* स्य = म्लेच्छ—मुख means ‘copper’म्लेच्छास्यं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छे म्लेच्छदेशे आस्यमुत्पत्ति-रस्य ।) ताम्रम् । इति हारावली ॥ म्लेच्छास्यं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छे म्लेच्छदेशे आस्यमुत्पत्ति-रस्य ।) ताम्रम् । इति हारावली ॥ म्लेच्छमुखं, क्ली, (म्लेच्छे म्लेच्छदेशे मुखमुत्पत्ति- रस्य । इत्यमरटीकायां रघुनाथः ।) ताम्रम् । इत्यमरः । २ । ९ । ९७ ॥ (तथास्य पर्य्यायः । “ताम्रमौदुम्बरं शुल्वमुदुम्बरमपि स्मृतम् । रविप्रियं म्लेच्छमुखं सूर्य्यपर्य्यायनामकम् ॥” इति भावप्रकाशस्य पूर्ब्बखण्डे प्रथमे भागे ॥ “ताम्रमौडुम्बरं शूल्वं विद्यात् म्लेच्छमुख- न्तथा ॥” इति गारुडे २०८ अध्याये ॥)

Prabhakar, V. N. and Majid, Jaseera C. , "Preliminary results of excavation at Karanpura, a Harappan settlement in district Hanumangarh", Man and Environment, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 13-41, 2014.

Abstract

Karanpura is located on the River Chautang (ancient Drishadvati, a tributary of River Sarasvati) nearly 60 km west of Hissar and 6 km west of Bhadra on the Bhadra-Goga Medi road in District Hanumangarh, Rajasthan. The Excavation Branch II of the Archaeological Survey of India excavated the site for two field seaso-ns, viz., 2012- 13 and 2013-14. The excavation brought to light occupational remains of Early Harappan and Mature Harap-pan phases of Harappan civilization. The occupational remains of over 3 m evidenced a continuous occupation at the site starting around circa 2800 BCE until around the end .of second millennium BCE. The upper 1.5 m of occupational deposit had been removed by local villagers for agricultural purposes and it hence could be presumed that the end of the habitation occurred towards 2000 BCE. Nevertheless the excavation has enabled us to understand the dynamics of Harappan culture and its spread into the areas watered by the tributary rivers like River Drishadvati for reasons of exploitation of various copper resources located in the northern Aravalli region. The access to these raw material sources might have been facilitated through the settlements located on the River Drishadvati to a larger extent. This paper puts forth the preliminary results of two seasons of excavation at this site

4. Water management

This review provides a framework for the detailed design of channels for the reborn Sarasvati based on the Perspective Plan of NWDA (Min. of Water Resources) Sharda-Yamuna-Rajasthan-Sabarmati Links (with aqueducts across Ganga and Yamuna which will be engineering marvels). Hopefully, the links which will be perennial channels drawing upon the resources of Meham glacier, will be put on fast-track.

5. Formation and evolution of Bharatiya languages from the roots of Sarasvati civilization

It is important to identify the lingua franca of Bharatiya civilization which emerged on the banks of River Sarasvati. Pots and pans, implements and metal-/lapidary-work should get documented in the languages of the region. There is increasing recognition among linguists (such as Emeneau, Kuiper, Masica) that India was a linguistic area or sprachbund (language union) cutting across and absorbing words from Austro-Asiatic, Dravidian and Indo-Aryan language families. Scholars like David Snow (Univ. of Hawaii) have pointed to the links of Autro-Asiatic languages of the Far East with Munda speakers of Bharatam. The multi-disciplinary initiatives for studying the roote and evolution of the civilization should include promotion of studies related to the formation and evolution of languages such as Prakrtam, Desi (Gujarati), Marathi, Maithili, Santali to identify the language speakers whose identity is closely linked to the identity of ancestors of present-day Bharatiyas.

The Indus Script Corpora which started with 2,200 inscriptions documented in Mahadevan Concordance (ASI) has now grown to over 7000 with over 4500 inscriptions discovered in two sites alone: Mohenjo-daro and Harappa PLUS over 2000 inscriptions on so-called Persian Gulf/Dilmun seals from a number of sites along the Persian Gulf. May Indus Script inscriptions have also been found in sites of Ancient Near East (Mesopotamia and also from a shipwreck in Haifa (Levant, Israel) with three inscribed tin ingots). A documentation of the inscriptions should be made available for all

6. 6. Dissemination of information and peoples’ participation

The remarkable initiatives of Min. of Culture (ASI, in particular) should be disseminated in all Bharatiya languages to reach every students of every educational institution in the nation through multi-media presentations.

To promote participation of people in the new multi-disciplinary initiatives, Min. of Culture may consider setting up Heritage Resource Centers in the nodes of Dholavira, Kurukshetra, Chandigarh, Rakhigarhi with facilities of researchers to participate – as research fellows under the guidance of experts -- in the eco- and cultural tourism programmes suggested by Dr. Jagmohan in his letter to the PM (copy of letter attached).

Dr. S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Centre

July 15, 2016

Attachment (May 7, 2006 letter of Dr. Jagmohan to PM)

Jagmohan's open letter (May 7, 2006) to Prime Minister on Sarasvati civilization

A search for our lost cities

May 7, 2006

Dear Dr Manmohan Singh-ji,

This pertains to a special project, which I had conceived when I was working as Culture and Tourism Minister. The project, I thought, would have enlarged the dimensions of tourism, provided new insight into the origin of our civilization, and attracted a number of scholars and archaeologists to study the unexplored layers of our past. Unfortunately, it has since been given up.

Through this letter, I am approaching you with the request to intervene and ensure that the project is viewed in the right perspective and revived. I give below a brief backdrop of the project and the course that it intended to follow.

From the point of view of culture, the project was named as “A search For Lost Cities, A Lost Civilization and A Lost River”, and from the tourism point of view it was titled, “Travels Around Lost Cities, A Lost Civilization and a Lost River”. The river was Sarasvati and the civilization was the one known as Harappan/Indus-Sarasvati.

There were five major objectives that the project sought to achieve: 1) To undertake extensive excavations of the Harappan settlements in the basin of the now dried-up Sarasvati, and build archaeological museums at the sites.

2) Set up small tourist-cent res nearby.

3) Establish documentation-cum-multidisciplinary research units with attached pavilions, showing 5,000 years of Indian civilization through large panel-photographs, 3-D models etc.

4) Make the newly created complex attractive for residents of the neighboring towns and villages.

5) Open at each of the centres, a small window to the visitors.

The significance lay in the attempt to provide clear answers to some crucial questions, which I will answer one by one:

Was there an Aryan invasion?

It has been propagated by Western scholars and their Indian disciples that

between 1,500 to 1,000 BC, there was an invasion of India by light-skinned nomadic tribes, the Aryans, which gave birth to the Vedic civilization of India. But this hypothesis has no legs to stand upon. The study of Colin Renfrew, a noted archaeologist at Cambridge University, not only debunks the theory propounded by Mortimer Wheeler but also points at the similarities between the Aryan Vedic civilization and the Harappan one. Nor can the theory of invasion/migration provide answers to pertinent questions like: How come the ‘Aryans’, who showed strong attachment to lands, did not carry with them the memories of their previous homeland and nurse no nostalgia about their past? Is it not clear that the Rig-Vedic expressions like ‘sabha’, ‘samiti’, ‘samrat’, ‘ranjan’, ‘rajaka’, which indicate the existence of organized assemblies and rulers of different ranks, are relevant not to the nomadic invaders, but to the advanced urban society of the Vedic Aryans who were indigenous inhabitant of Harappan settlements? Was not the evolution of chariot more likely in the flat lands of North India rather than in the uneven terrain of the Central Asia?

The last nail in the coffin of the invasion/migration theory has been hammered in by the recent genetic studies, conducted by scientists in Calcutta with foreign scientists. They analyzed the Y-Chromosomes of 936 men and 77 castes, and referred to the work of the international research teams that found that the earliest modern human arrived in India from Africa, trudging along the Indian Ocean coast about 60,000 years ago. They concluded: “Our findings suggest that most modern Indians have genetic affinities to the earlier settlers and

subsequent migrants and not to central Asians or ‘Aryans’, as they are called”.

Nature of Civilization

When, in 1922, the Harappan civilization was discovered, only two major settlements — Mohenjo-daro and Harappa — had been excavated and that too partially. On this basis, views were formulated about the origin of these advanced urban civilizations. It was given out that its roots lay in Mesopotamia. Subsequent excavations of more Harappan sites have shown that these views and assertions were made without adequate evidence.

John Reader, a noted scholar of anthropology and geography, has pointed out that emergence of cities and civilizations in six widely separated places around

the world — Mesopotamia, India, Egypt, China, Central America and Peru — was spontaneous and none resulted from contact with one another.

Excavations carried out by a French team, headed by Jean-Francois Jarrige, during the last 15 years, at Mehrgarh, Pakistan, have pin-pointed the beginnings

of civilization in India and shown that Indus-Sarasvati civilization had no moorings in Mesopotamia or any civilization outside India.

It has been rightly observed: “The people in Mehrgarh tradition are the people of India today”. There are similarities between the social and religious practices of the Harappan people and the people of present-day India. For example, the spiralled bangles of the type found around the figurine of the Harappan dancing

girl can still be seen on the arms of women in Haryana, Rajasthan, Gujarat, etc.

Again, as was the case with Harappan women, ‘sindoor’ is applied by married women of Hindu families. Some other common features of the two periods are: the practice of worshipping trees, putting of Svastika symbol at the entrance of the houses etc.

Did Sarasvati exist?

There is ample evidence that supports the view that river Sarasvati once existed.

Literary: The Rig Veda mentions the Sarasvati about 50 times, describing it as “the best mother, the best river, the best goddess”. The famous Nadi-stuti hymn mentions a set of rivers, including Ganga, Yamuna, Sarasvati and Sutudori (Sutlej) and places Sarasvati between Yamuna and Sutlej. Its origin is indicated in the hymn that says: “Purest among all rivers and vibrant, the Sarasvati moves on from the mountains to the ocean, manifesting immense riches of the world…” She is also called the seventh “Indus Mother”. Ancient literature also talks of when Sarasvati began to decline. The Mahabharata, the Aitareya and the Satapatha Brahamana refer to its disappearance in the desert.

Archaeological: In 1872, C.F. Oldham and R.D. Oldham undertook a detailed survey of the area where the Sarasvati and its tributaries were said to be flowing in earlier times. They concluded that it was once fed by the Sutlej and the Yamuna, and that it disappeared after the westward movement of the former and eastward movement of the latter.

Geological: A group of scientists led by V.M.K. Puri and B.C. Verma, made a detailed study of the areas from which Sarasvati could have originated. They observed: “This river was in existence during the upper Pleistocene period as it was fed by glaciers that had descended to much lower limits in Garhwal Himalaya than the present day level due to the influence of Pleistocene Ice Age.”

Hydrological: After the Pokhran nuclear explosion on May 11, 1998, the Bhabha

Atomic Research Centre conducted tests to assess the impact of the explosions on the quality of water in the area around. These tests, interalia, revealed that the water in the area was potable, about 8,000 to 14,000 years old, came from the Himalayan glaciers and was being slowly recharged through aquifers from somewhere in the north. Separately, the Central Ground Water Commission dug a number of wells on and along the dry bed. Out of 24 wells dug, 23 yielded potable water.

If all that I have said is viewed in entirety, this is the picture that will emerge: the period 6,500-3,100 BC saw the growth of pre-Harappan/Indus-Sarasvati

civilization, corresponding broadly to the times when the Rig Veda was composed; that during the period 3,100 to 1,900 BC, the Harappan/Indus-Sarasvati civilization prevailed and these were the times when the hymns of four Vedas were composed; and that 1,900 to 1,000 BC was the time of the late Harappan/Indus-Sarasvati civilization which saw the decline and ultimate

disappearance of the surface water of the Sarasvati, forcing the people to move eastward towards the Gangetic plain.

While the puzzles of archaeology and ancient Indian history cannot be resolved with certainty, particularly with regard to Harappa where the script has not so far been deciphered, it could be stated with a fair degree of accuracy that the Harappan/Indus-Sarasvati civilization was born and brought up on the soil of India and its people and Vedic people were one and the same.

A lot of additional work needs to be done to unravel a number of features of one of the most significant civilizations of the ancient world. Hundreds of sites in the

basin of now the submerged Sarasvati need to be excavated. It was this need that the special project intended to meet.

This would also be of huge benefit to the tourism sector. I request you to recommence the special project. I am confident that the project, if implemented in the spirit it was conceived, would show new facets of India’s past, new initiatives of her present and new visions for her future.

Yours sincerely,

Jagmohan

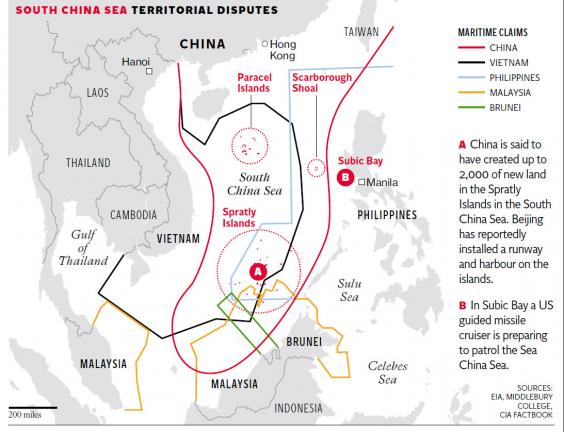

Chinese dredging vessels are purportedly seen in the waters around Fiery Cross Reef in the disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, November, 2015

Chinese dredging vessels are purportedly seen in the waters around Fiery Cross Reef in the disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, November, 2015

शम्बुक्क, शम्बुक [p=

शम्बुक्क, शम्बुक [p=

An Indian Ocean dhow. "

An Indian Ocean dhow. "

Badari twig

Badari twig

Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph.

Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph.  m478a tablet

m478a tablet

The pair of 'ovals or ellipses' are infixed with 'notches'. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implement'. dhal 'slope' rebus: dhALako 'large ingot (oxhide)' PLUS

The pair of 'ovals or ellipses' are infixed with 'notches'. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implement'. dhal 'slope' rebus: dhALako 'large ingot (oxhide)' PLUS

The Shahdad standard has the 'twisted strand' hieroglyph together with tree, zebu, lion, woman. kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite' arye 'lion' rebus: Ara 'brass' meD 'twist' rebus: meD 'iron, copper, metal'. kola 'woman' rebus: kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'.

The Shahdad standard has the 'twisted strand' hieroglyph together with tree, zebu, lion, woman. kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite' arye 'lion' rebus: Ara 'brass' meD 'twist' rebus: meD 'iron, copper, metal'. kola 'woman' rebus: kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'.

Rhd-157

Rhd-157 C-49, C-50

C-49, C-50

m592

m592

Rein Rings atop the shaft of the ceremonial 'chariot' (sledge) found in Queen Pu-abi's tomb. valgā

Rein Rings atop the shaft of the ceremonial 'chariot' (sledge) found in Queen Pu-abi's tomb. valgā

Subramanian Swamy

Subramanian Swamy

Part of a funeral stele, chariot scene, Mycenae 16th cent. BCE The hieroglyphs of molluscs and bivalve shells signify

Part of a funeral stele, chariot scene, Mycenae 16th cent. BCE The hieroglyphs of molluscs and bivalve shells signify

British Museum Number

British Museum Number

Bronze ingot from the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck, about 1200 BC. On display in the Museum of Underwater Archaeology at Bodrum Castle, Turkey.

Bronze ingot from the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck, about 1200 BC. On display in the Museum of Underwater Archaeology at Bodrum Castle, Turkey.

Chakravartin and 7 jewels

Chakravartin and 7 jewels

Inscribed tablets. Third from l. Ajatasatru pillar sculptural frieze.

Inscribed tablets. Third from l. Ajatasatru pillar sculptural frieze. Pasenadi pillar with inscribed tablet

Pasenadi pillar with inscribed tablet Jetavana monastery on medallion. Rectangular coins spread out on field

Jetavana monastery on medallion. Rectangular coins spread out on field Soldier with long sword with kampaTTa 'mint' hieroglyph

Soldier with long sword with kampaTTa 'mint' hieroglyph.jpg/300px-GreekKing(Drawing).jpg) The sword is inscribed with a srivatsa hypertext.

The sword is inscribed with a srivatsa hypertext. Srivatsa on a soldier's arm, together with a dotted circle dhAu 'strand' rebus: dhAu 'element, mineral ore'

Srivatsa on a soldier's arm, together with a dotted circle dhAu 'strand' rebus: dhAu 'element, mineral ore' kampaTTa 'mint' hieroglyph PLUS tAmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tAmra 'copper'

kampaTTa 'mint' hieroglyph PLUS tAmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tAmra 'copper'

Pupphadevi holding a bronze mirror

Pupphadevi holding a bronze mirror Yakkhi holding a bronze mirror. Wears necklace with kammaTa 'mint' hieroglyph

Yakkhi holding a bronze mirror. Wears necklace with kammaTa 'mint' hieroglyph

Kumbhandas carrying a box of coins

Kumbhandas carrying a box of coins