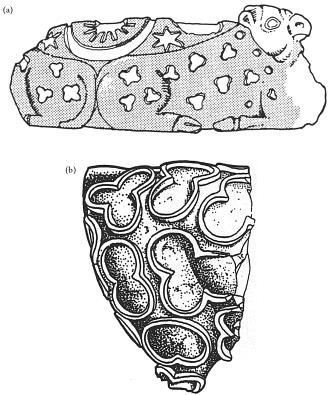

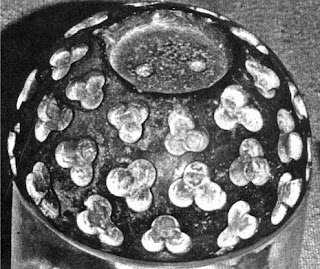

A fragment of a relief 'The spinner' made of Bitumen mastic of Neo-Elamite period (8th cent. BCE - middle of 6th cent. BCE) was found in Susa. This fragment displayed a well-coiffured woman being fanned by an attendant while the woman wearing bangles on both arms -- seated on a stool with feline legs -- held what may be a spinning device before a table with feline legs with a bowl containing a whole fish with six blobs assembled on top of the fish.

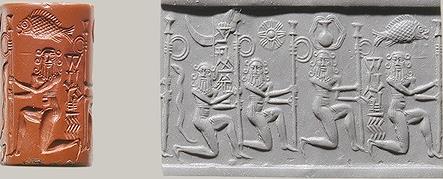

Hieroglyphs: curls on hair, fan, feline-legged stools, six round objects, fish, arms with bangles, headband, hair-knot, spindle, circles on scarf.

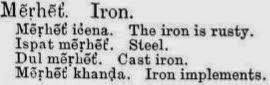

Hieroroglyph: aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati) ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

kola 'tiger' Rebus: kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron'; kolhe 'smelter' kole.l 'smithy, temple'; kolimi 'smithy, forge' Hieroglyph: bhaṭa 'six' Rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'.

2861 karttr̥2 m. ʻ spinner ʼ MBh. [√kr̥t2]H. kātī f. ʻ woman who spins thread ʼ; -- Or. kãtiā ʻ spinner ʼ with ã from verb kã̄tibā (CDIAL 2861) See: khātrī m. ʻ member of a caste of Hindu weavers ʼ.(Gujarati)(CDIAL 3647) kātī 'spinner' Rebus: khātī m. ʻ member of a caste of wheelwrights ʼ(Hindi) kṣattŕ̊ m. ʻ carver, distributor ʼ RV., ʻ attendant, door- keeper ʼ AV., ʻ charioteer ʼ VS., ʻ son of a female slave ʼ lex. [√kṣad]Pa. khattar -- m. ʻ attendant, charioteer ʼ (CDIAL 3647)

Note on the spinner in the Louvre

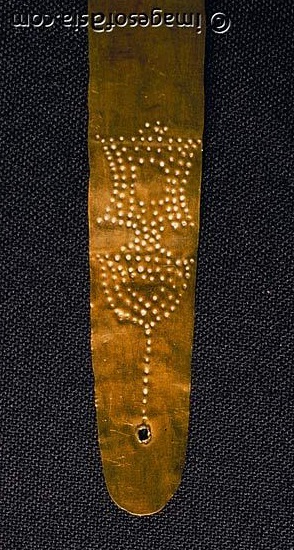

Technical descriptionBas-relief fragment, called "The Spinner"BitumenJ. de Morgan excavationsSb 2834Near Eastern AntiquitiesSully wingGround floorIran in the Iron Age (14th–mid-6th century BC) and during the Neo-Elamite dynastiesRoom 11Display case 6 b: Susiana in the Neo-Elamite period (8th centurymiddle 6th century BC). Goldwork, sculpture, and glyptics

This votive or commemorative relief shows a woman squatting on a stool holding a spindle. Behind her, a servant cools her with a fan; before her stands a pedestal table laden with food. Another figure formerly stood facing her. This figure of a spinner is one of the rare images of a woman in her personal domestic environment in the ancient Orient.

The image of women in the ancient Orient

Women appear in many ancient Oriental texts, always in the background of a predominant male figure. With the exception of goddesses, they feature more rarely in images pertaining to fertility. In this domestic scene, the woman is seated in an informal manner, with one leg folded under her. With her arms full of bracelets, she turns the spindle: the flower-shaped tip is visible above her left hand, and the thread accumulates below the conical spinning whorl serving as a pulley. No skein is visible, perhaps because the scene may not represent the act of spinning so much as the spinner's satisfied presentation of her work to an important figure who is just visible on the other side of the table. She is dressed in a sleeveless tunic; her decorated veil, which does not cover her head - probably because she is an intimate setting - reveals her long hair, pulled back in a bun and held in place with a headscarf crossed around her head. Her face is calm but smiling, her body plump and stocky.

A royal interior

Behind the spinner stands a figure, as large as the seated figure, either because it is a child, or rather because the artist is indicating a social hierarchy. The standing figure has large round curls, wears a short-sleeved tunic and jewelry on his or her wrists, and is shown fanning the spinner with a square fan on a long handle, whose parallel grooves suggest wickework. The spinner's stool is covered with a fabric whose fringed edges hide the upper part of the seat; an ornament protruding at the back, probably an animal's head, remains visible. The feet, joined together by a triple brace, are sculpted in the shape of thick lion claws. This decoration is also visible on the table, a low pedestal table with a thick top resting on molded capitals. This highly ornate style of furniture resembles that depicted on certain Assyrian stone reliefs, at Khorsabad (Louvre), and on the "Banquet under the Arbor" relief from Nineveh (British Museum), featuring a similar scene. Excavations at Ugarit, Nimrud and Arslan Tash (Louvre) produced similar ornamentations in ivory. In the ancient Orient, only gods and sovereigns received such furnishings, a privilege reflected in the inventories of royal trousseaux and lists of booty drawn up by Assyrian scribes. Ordinary people ate and slept on the floor. This scene therefore probably takes place in the divine world or in the palace at Susa, at the court of a Neo-Elamite sovereign, perhaps the figure on the right now completely lost.

A Susian material

The material used to sculpt this relief is highly characteristic of Susa: a bituminous stone, a matte, black sedimentary rock. Deposits of bitumen, a thick hydrocarbon, are relatively numerous in Mesopotamia and in western Iran, an area of abundant oil resources, but the bituminous stone deposit in the Susa region seems to have been unique and the Susians were the only ones to use it from the 4th millennium. The fine grain of the stone permitted a high level of precision in the details. If heated slightly, the stone could be coated with gold or silver leaf or receive incrustatations of various materials, for the making of luxury objects typical of Susa.

Bibliography

Amiet Pierre, Elam, Auvers-sur-Oise, Archée, 1966, p. 413.

Amiet Pierre, Suse : 6000 ans d'histoire, Éditions de la Réunion des Musées nationaux, coll. "monographies des Musées de France", 1988, p. 112, fig. 69.

The Royal City of Susa. Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre, catalogue de l'exposition, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1992, pp. 200-201, cat. n 141.

Connan Jacques , Deschesne Odile, Le bitume à Suse : collection du Musée du Louvre, Éditions de la Réunion des Musées nationaux, Elf Aquitaine Production, 1996, p. 227, fig. 34 ; pp. 339-340, cat. n 431.

Herrmann Georgina (éd.), Furniture in Ancient Orient, Mainz, Philipp von Zabern.

Roaf Mickhaël, Atlas de la Mésopotamie et du Proche Orient antique, Brepols, 1991, p. 130.

http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/spinner

Resources to delineate Meluhha (Mleccha) language of ca. 4th millennium BCE

Delineating Meluhha (Mleccha) language of ca. 4th millennium BCE, a date which produced evidence of the earliest writing on a Harappa potsherd is a philological challenge. Attempts can be made to respond to this challenge using a variety of textual resources available, apart from using the Indus Writing corpora as a frame of reference to validate the Meluhha (Mleccha) words. This note discusses some resources provided by studies related to ancient Indian languages which contributed to the Indian sprachbund.

Ancient arts related to communicating ideas

Vātsyāyana’s Kāmasūtra refers to a cipher called mlecchita vikalpa (alternative representation in writing of mleccha (Meluhha) language) as one of the 64 arts to be learnt by youth. Vātsyāyana also uses the phrase deśabhāṣā jñānam referring to the learning of vernacular languages and dialects. deśabhāṣā is also variously referred to as deśī or deśya. He also uses the phrase akṣara muṣṭikā kathanam as another of the 64 arts. This is a reference to karaṇa or karaṇīmentioned in Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra as gesticulation or articulation in dance using positions of finger-knuckles and wrists to convey messages or bhāvá‘thought or disposition’. akṣara muṣṭikā is explained by Monier-Williams (p. 3) as: ‘the art of communicating syllables or ideas by the fingers (one of the 64 kalās, Vātsyāyana)’.

करण the occupation of this class is writing , accounts (Monier-Williams, p. 254) n. (in law) an instrument , document , bond Mn. viii , 51 ; 52 ; 154. m. writer , scribe. n. the special business of any tribe or caste करणी f. a particular position of the fingers (Monier-Williams, p. 254) n. pronunciation , articulation , APrāt.करण n. the act of making , doing , producing , effecting S3Br. MBh. &c (very often ifc. e.g. मुष्टि-क्° , विरूप-क्°) Pori ‘the joints of a bamboo, a cane, or the fingers’ (Maltese)(DEDR 4541). Pkt. pora- joint (CDIAL 8406). Meluhha is cognate mleccha. Mleccha were island-dwellers (attested in Mahabharata and other ancientIndian sprachbund texts). Their speech did not conform to the rules of grammar (mlecchāḥ mā bhūma iti adhyeyam vyākaraṇam) and had dialectical variants or unrefined sounds in words (mlecchitavai na apabhāṣitavai) (Patanjali: Mahābhāṣya). Prākṛitarūpāvatāra literally means ‘the descent of Prākṛit forms’. Pischel noted: “…the Prākṛitarūpāvatāra is not unimportant for the knowledge of the declension and conjugation, chiefly because Simharāja frequently quotes more forms than Hēmachandra and Trivikrama. No doubt many of these forms are theoretically inferred; but they are formed strictly according to the rules and are not without interest.” (Pischel, 1900, Grammatik der Prākṛit-Sprachen, Strassburg, p.43). Pischel also had written a book titled, Hēmachandra's Prākṛit grammar, Halle, 1877. The full text of the Vālmīkisūtra, with gaṇas, dēśīyas, and iṣṭis, has been printed in Telugu characters at Mysore in 1886 as an appendix to the ṣaḍbhāṣachandrikā.

A format to determine the structure of Prākṛit is to identify words which are identical with Sanskrit words or can be derived from Sanskrit. In this process, dēśīyas or dēśyas, ‘provincialisms’ are excluded. One part of the work of Simharja is samjñāvibhāga ‘technical terms’. Another is pari bhāṣāvibhāga ‘explanatory rules’. Dialects are identified in a part called śaurasēnyādivibhāga; the dialects include: śaurasēni, māgadhī, paiśācī, chūḷikā paiśācī, apabhramśa.

Additional rules are identified beyond those employed by Pāṇini:

sus, nominative; as, accusative; ṭās, instrumental; nēs, dative; nam, genitive; nip, locative.

Other resources available for delineation of mleccha are: The Prākṛita-prakāśa; or the Prākṛit grammar of Vararuchi. With the commentary Manorama of Bhamaha. The first complete ed. of the original text... With notes, an English translation and index of Prākṛit words; to which is prefixed a short introd. to Prākṛit grammar (Ed. Cowell, Edward Byles,1868, London, Trubner)

On these lines, and using the methods used for delineating Ardhamāgadhi language, by Prākṛita grammarians, and in a process of extrapolation of such possible morphemic changes into the past, an attempt may be made to hypothesize morphemic or phonetic variants of mleccha words as they might have been, in various periods from ca. 4th millennium BCE. There are also grammars of languages such as Marathi (William Carey), Braj bhāṣā grammar (James Robert), Sindhi, Hindi, Tamil (Tolkāppiyam) and Gujarati which can be used as supplementary references, together with the classic Hemacandra's Dēsīnāmamālā, Prākṛit Grammar of Hemachandra edited by P. L. Vaidya (BORI, Pune), Vararuchi's works and Richard Pischel's Comparative Grammar of Prākṛit Languages.(Repr. Motilal Banarsidass, 1957). Colin P. Masica's Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge University Press, 1993,"... has provided a fundamental, comparative introduction that will interest not only general and theoretical linguists but also students of one or more languages (Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Punjabi, Gujurati, Marathi, Sinhalese, etc.) who want to acquaint themselves with the broader linguistic context. Generally synchronic in approach, concentrating on the phonology, morphology and syntax of the modern representatives of the group, the volume also covers their historical development, writing systems, and aspects of sociolinguistics."Thomas Oberlies' Pali grammar (Walter de Gruyter, 2001) presents a full description of Pali, the language used in the Theravada Buddhist canon, which is still alive in Ceylon and South-East Asia. The development of its phonological and morphological systems is traced in detail from Old Indic (including mleccha?). Comprehensive references to comparable features and phenomena from other Middle Indic languages mean that this grammar can also be used to study the literature of Jainism. Madhukar Anant Mehendale's Historical Grammar of Inscriptional Prākṛit s is a useful aid to delineate changes in morphemes over time. A good introduction is: Alfred C. Woolner's Introduction to Prākṛit , 1928 (Motilal Banarsidass). "Introduction to Prākṛit provides the reader with a guide for the more attentive and scholarly study of Prākṛit occurring in Sanskrit plays, poetry and prose--both literary and inscriptional. It presents a general view of the subject with special stress on Sauraseni and Maharastri Prākṛit system. The book is divided into two parts. Part I consists of I-XI Chapters which deal with the three periods of Indo-Aryan speech, the three stages of the Middle Period, the literary and spoken Prākṛit s, their classification and characteristics, their system of Single and Compound Consonants, Vowels, Sandhi, Declension, Conjugation and their history of literature. Part II consists of a number of extracts from Sanskrit and Prākṛit literature which illustrate different types of Prākṛit --Sauraseni, Maharastri, Magadhi, Ardhamagadhi, Avanti, Apabhramsa, etc., most of which are translated into English. The book contains valuable information on the Phonetics and Grammar of the Dramatic Prākṛit s--Sauraseni and Maharastri. It is documented with an Index as well as a Students'. " It may be noted that Hemacandra is a resource which has provided the sememe ibbo 'merchant' which reads rebus with ibha 'elephant' hieroglyph.

Sir George A. Grierson's article on The Prākṛit Vibhasas cites: "Pischel, in §§3, 4, and 5 of his Prākṛit Grammar, refers very briefly to the Vibhāṣās of the Prākṛit grammarians. In § 3 he quotes Mārkaṇḍēya's (Intr., 4) division of the Prākṛit s into Bhāṣā, Vibhāṣā, Apabhraṁśa, and Paiśāca, his division of the Vibhāṣās into Śākārī, Cāṇḍālī, Śābarī, Ābhīrikā, and Ṭākkī (not Śākkī, as written by Pischel), and his rejection of Auḍhrī (Pischel, Oḍrī) and Drāviḍī. In § 4 he says, “Rāmatarkavāgīśa observes that the vibhāṣāḥcannot be called Apabhraṁśa, if they are used in dramatic works and the like.” He repeats the latter statement in § 5, and this is all that he says on the subject. Nowhere does he say what the term vibhāṣā means. The present paper is an attempt to supply this deficiency." See also: http://www.indianetzone.com/39/Prākṛit _language.htm

"...Ganga, on the lower reaches of which were the kingdoms of Anga, Variga, and Kalinga, regarded in the Mahabharata as Mleccha. Now the non- Aryan people that today live closest to the territory formerly occupied by these ancient kingdoms are Tibeto-Burmans of the Baric branch. One of the languages of that branch is called Mech, a term given to them by their Hindu neighbors. The Mech live partly in Bengal and partly in Assam. B(runo) Lieblich remarked the resemblance between Mleccha and Mech and that Skr. Mleccha normally became Prākṛit Meccha or Mecha and that the last form is actually found in Sauraseni. 1 Sten Konow thought Mech probably a corruption of Mleccha.* I do not believe that the people of the ancient kingdoms of Anga, Vanga, and Kalinga were precisely of the same stock as the modern Mech, but rather that they and the modern Mech spoke languages of the Baric division of Sino-Tibetan. " (Robert Shafer, 1954, Ethnography of Ancient India, Otto Harras Sowitz, Wiesbaden).http://archive.org/stream/ethnographyofanc033514mbp/ethnographyofanc033514mbp_djvu.txt The following note is based on: Source: MK Dhavalikar, 1997, Meluhha, the land of copper, South Asian Studies, 13:1, 275-279 (embedded document appended):

Citing a cuneiform tablet inscription of Sargon of Akkad (2370-2316 BCE), Dhavalikar notes that the boats of Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha were moored at the quay in his capital (Leemans, WF, 1960, Foreign Trade in the Old Babylonian Period as revealed by texts from Southern Mesopotamia, EJ Brill, Leiden, p. 11). The goods imported include agate, carnelian, shell, ivory, varieties of wood and copper. Dhavalikar cites a reference to the people or ‘sons’ of Meluhha who had undergone a process of acculturation into Mesopotamian society of Ur III times cf. Parpola, S., A. Parpola and RH Brunswwig, Jr., 1977, The Meluhha Village: evidence of acculturation of Harappan traders in the late Third Millennium Mesopotamia, JESHO, 20 , p.152. Oppenheim describes Meluhha as the land of seafarers. (Oppenheim, AL, 1954, The seafaring merchants of Ur, JAOS, 74: 6-17). Dhavalikar notes the name given to a rāga of classical Indian (Hindustani) music – maluha kedār – which may indicate maluha as a geographical connotation as in the name of another rāga called Gujarī Todi. Noting a pronunciation variant for meluhha, melukkha, the form is noted as closer to Prākṛit milakkhu (Jaina Sūtras, SBE XLV, p. 414, n.) cognate Pali malikkho or malikkhako (Childer’s Pali Dictionary). Prākṛit milakkhu or Pali malikkho are cognate with the Sanskrit word mleccha (References cited include Mahabharata, Patanjali). Jayaswal (Jayaswal, KP, 1914, On the origin of Mlechcha, ZDMG, 68: pp. 719-720) takes the Sanskrit representation to be cognate with Semitic melekh (Hebrew) meaning ‘king’.

Śathapatha Brāhmaṇa [3.2.1(24)], a Vedic text (ca. 8th century BCE) uses the word mleccha as a noun referring to Asuras who ill-pronounce or speak an imprecise language: tatraitāmapi vācamūduḥ | upajijñāsyāṃ sa mlecastasmānna brāhmaṇo mlecedasuryāhaiṣā vā natevaiṣa dviṣatāṃ sapatnānāmādatte vācaṃ te 'syāttavacasaḥ parābhavanti ya evametadveda. This is a remarkable reference to mleccha (meluhha) as a language in the ancient Indian tradition. Pali texts Digha Nikāya and Vinaya, also denotes milakkha as a language (milakkha bhāsā). Comparable to the reference in Manu, a Jaina text (Pannavana, 1.37) also described two groups of speakers (people?): ārya and milakkhu. Pāṇini also observes the imprecise nature of mleccha language by using the terms: avyaktayam vāci (X, 1663) and mleccha avyakte śabde (1.205). This is echoed in Patanjali’s reference to apaśabda.

Dhavalikar notes: “Sengupta (1971) has made out a strong case for identifying mlecchas with the Phoenicians. He proposes to derive the word mleccha from Moloch or Molech and relates it to Melek or Melqart which was the god of the Phoenicians. But the Phoenicians flourished in the latter half of the second and the first half of the first millennium when the Harappan civilization was a thing of the past.” (: MK Dhavalikar, 1997, Meluhha, the land of copper, South Asian Studies, 13:1, p. 276).

Worterbuch (St. Petersburg Dictionary), Hemacandra’s Abhidāna Cintāmaṇi (IV.105), lexicons of Monier Williams and Apte give ‘copper’ as one of the meanings of the lexeme mleccha.

Gudea (ca. 2200 BCE) under the Lagash dynasty brought usu wood and gold dust and carnelian from Meluhha. Ibbi-Sin (2029-2006 BCE) under the third dynasty of Ur “imported from Meluhha copper, wood used for making chairs and dagger sheaths, mesu wood, and the multi-coloured birds of ivory.”

Dhavalikar argues for the identification of Gujarat with Meluhha (interpreted as a region and as copper ore of Gujarat) and makes a reference to Viṣṇu Purāṇa (IV,24) which refers to Gujarat as mleccha country.

Nicholas Kazanas has demonstrated that Avestan (OldIranian) is much later than Vedic. "'Vedic and Avestan' by N. Kazanas In this essay the author examines independent linguistic evidence, often provided by iranianists like R. Beekes, and arrives at the conclusion that the Avesta, even its older parts (the gaθas), is much later than the Rigveda. Also, of course, that Vedic is more archaic than Avestan and that it was not the Indoaryans who moved away from the common Indo-Iranian habitat into the Region of the Seven Rivers, but the Iranians broke off and eventually settled and spread in ancientv Iran." http://www.omilosmeleton.gr/pdf/en/indology/Vedic_and_Avestan.pdf

The oldest Prākṛit lexicon is the work of a Jaina scholar, Paiyalacchi nāmamālā of Dhanapāla (972 A. D.)

Mahapurana of Pushpadanta–A critical study: By Dr Smt. Ratna Nagesha Shriyan. L. D. Bharatiya Samskriti Vidyamandira, Ahmadabad–9 . Price: Rs. 30.

A thesis approved for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy by the Bombay University, this is a critical study of the Desya and rare material contained in the three Apabhramsa works of Pushpadanta, a major Apabhramsa poet of the Ninth Century CE D.

The first part mainly deals with the nature and character of Desya element and the role of Desya element in Prākṛit and Apabhramsa in general and Pushpadanta’s works in particular. The authoress pointed out that the term Deśī has been used in the earlier Sanskrit and Prākṛit literature mainly in three different senses, viz., (1) a local spoken dialect (2) a type of Prākṛit , (3) and as equivalent to Apabhramsa. The interpretations of the word Deśī as given by Hemachandra and modern scholars are also given in detail. The authoress comes to the conclusion that most of the modern scholars agree that “Desya or Deśī is a very loose label applied by early grammarians and lexicographers to a section of Middle Indo-Aryan lexical material of a heterogeneous character.

In part II, the more important one, the learned Doctor has collected 1430 words and divided them into seven categories– (1) items only derivable from Samskrit (2) Tadbhavas with specialized or changed meaning (3) items partly derivable from Samskrit (4) items that have correspondents only in late Samskrit (5) onometopoetic words (6) foreign loans and (7) pure Deśī words. Critical and comparative notes on their meanings and interpretations, with corroborating passages from original texts are also given here and they evidence the high scholarly labours of the authoress. We cannot, but respect the words of Dr H. C. Bhayani of the Gujarat University in whose opinion the present study paves “the way for investigating the bases and authenticity of Hemachandra’s Deśīnāmamālā and provides highly valuable material for middle and Modern Indo-Aryan lexicography.”

“Words which are not derived from Sanskrit in his grammar, which though derived from Sanskrit, are not found in that sense in the Sanskrit lexicons, which have changed their meaning in Prākṛit , the change not being due to the secondary or metaphorical use of words, and which are used in standard Prākṛit from times immemorial, are considered as deśī by Hemacandra (I,3,4). Thus, he teaches in his grammar (IV,2) that pajjar is one of the substitutes of the root kath in Prākṛit . In II,136 he says that trasta assumes the forms hittha and taTTha in Prākṛit . The words pajjara, hittha and taTTha are not, therefore, des’yas and are excluded from the work. The Verbal substitutes have been, as a matter of fact, considered as deśī words by Hemacandra’s predecessors (1.11,13,20). Again the word amayaNiggamo signifies the moon in Prākṛit , and it is evidently a bhava of amrutanirgama which by some such analysis as amrutaanirgamo yasya can denote the moon But the Sanskrit word is not found in that sense in any of the lexicons and hence amayaNiggamo is reckoned as a deśya and taught in this work. The word yayillo is a regular derivative of baliivarda according to rules of Prākṛit grammar, and as the latter word can by the force of lakshaNa mean a ‘fool’, the word vayillo in this sense is not considered a deśī word and, therefore, is not included in this work. Every provincial expression is not considered a deśī word, but only those which have found entrance into the known Prākṛit literature. Otherwise, the number of deśī words will be innumerable and it will be impossible to teach them all. As Hemacandra himself says (I,4): vacaspaterapi matirna prabhavati divyayugasahasreNa. This definition of a deśī word does not appear to have been followed by the predecessors of Hemacandra; and therein consists, he says, the superiority of his work over that of others. He quotes in a number of places words which have been taught as deśī words by his predecessors and shows that they are derived from Sanskrit words. Thus in I.37 Hemacandra says that the words acchoDaNam, alinjaramk, amilaayam and acchabhallo are considered as deśī words by some authors, but he does not do so as they are evidently derived from Sanskrit words. Again in II.89, he says that the word gamgarii is taught a a deśī word by some authors but Hemacandra says this is not a deśī word as it is derived from Sanskrit gargarii. But here our author shows some latitude and says that it may be considered a deśī word. Many such instances may be quoted and in most cases Hemacandra gives the Sanskrit equivalents to such words.” (Paravastu Venkata Ramanujaswami, in: Introduction, The Deśīnāmamālā of Hemachandra ed. By R. Pischel, 1938, 2nd edn., Dept. of Public Instruction, Bombay, pp.3-4).

TABLE : DICTIONARIES

PRĀKṛIT :

10 C.E : Deshi Nama Mala (Hemachandra)

11 C.E ![]() ayyalacchi Nama Mala (Maha Kavi Dhanapala)

ayyalacchi Nama Mala (Maha Kavi Dhanapala) 12 C.E :Abhidana Rajendra (Vijayendra Suri)

SANSKRIT

4 C.E : Amarakosha (Amarasimha) Dhanvantari Nighantu (Dhanvantari)

6 C.E : Anekartha Samucchaya (Shashaavata)

10 C.E : Abhidana Ratna Mala (Hemachandra ),Srikanda Shesha Vishvakosha (Srikanda Shesha),HaravaLi (Purushottama Deva) ,Abhidana Ratnamala (Halayudha)

11 C.E :Vyjayanti (Yadava Prakasha), Nama Mala (Dhananjaya) , Anekartha Nama Mala (Amara Keerti) , Shabdha Pradipa (Sureshvara)

12 C.E :Namarthaarnava Sankshepa , Shabda Kalpa Druma (Keshava Svamin ), Vishva Prakasha (Maheshvara) , Namartha Ratnamala (Abhaya Pala) , Abidana Cintamani +Anekartha Sangraha (Hemachandra) , Anekartha Kosha (Mankha) , Akyata Candrika (Malla Bhatta) , Raja Nighantu (Narahari)

14 C.E : Nanartha Ratna Mala (Irugappa Dandanatha) , Madana Vinoda Nighantu (Madana Pala)

15 C.E : Shabda Chandrike ( Vamana Bhatta) , Shabda Ratnakara(Bana)

16 C.E :Sundara Prakashabdarnava (Padma Sundara)

17 C.E :Kalpa Druma (Keshava Daivajna), Nama Sangraha Mala(Appaiah Dikshita)

TAMIL :

10 C.E – Sendan Divakaram (Divakaram) , Pingalantai (Pingalar)

12 C.E : Chudamani Nighantu (Mangala Puttiran)

16 C.E : Chudamani Nighantu ( Mandala Purutan) ,Akaradi Nighantu (Chidambara Revana)

17 C.E : Uriccol Nighantu (Gangeyan) , Kayataram (Kayatarar) ,Bharati Deepam (Anonymus) , Ashiriya Nighantu (Anonymus)

18 C.E : Pothigai Nighantu (Swaminatha Kavirayar), Pal Porul Chudamani (Eshwara Bharati) , Arumpporul Vilakka Nighantu (Anonymus)

KANNADA

10 C.E : Ranna Kanda (Ranna)

11 C.E : Abhidana Vastu Kosha (Nagavarma-2) ,Abhidana Ratna Mala+Amarakosha Bhashya (Halayudha)

12 C.E :Nachirajiya (Naciraja)

13 C.E : Akaradi Vaidya Nighantu+Indra Dipike+Madanari (Amrutanandi)

14 C.E: Karnataka Shbda Sara (Anonymus) , Karnataka Nighantu (Anonymus), Abhinavabhidana (Abhinava Mangaraja)

15 C.E : Chaturasya Nighantu(Bommarasa) , Dhanvantariya Nighantu (Anonymus)

16 C.E : Kabbigara Kaipidi (Linga Mantri) , Shabda Ratnakara (Anonumus) , Nanartha Kanda (Chenna Kavi) , Nanartha Ratnakara+Ekakshara Nighantu (Devottama) , Karnataka Shabda Manjari (Totadarya) , Bharata Nighantu (Anonymus) , Amarakosha Dipike (Vitthala)

17 C.E : Karnataka Sanjivini +Kavi Kanthahara (Shrungara Kavi) , Karnataka Nighantu (Surya kavi)

TELUGU :

14-18 C.E : Venkateshandhramu (Ganavarapu Venkatakavi) , Akaradi Deshiyandhra Nighantu ( Anonymus), Andhra Prayoga Ratnakaram (Anonymus) , Sarva Lakshana Shiromani (Anonymus) ,Padya Rupa Amara Kosham ( Venkata Rayudu), Andhra Nama Sangraham (Lakshmana Kavi) , Andhra Nama Vishesham (Sura Kavi) Samba Nighantuvu (Kasturi Ranga) , Andhra Bhasharnavam ( Venkata Narayanudu) , Akshara Malika Nighantu (Parvatishvara Shastry) , Andhra Pada Nidanam (Tumu Ramadasa) , Sarnadhra Sara sangraham (Amrutapuram Sanyasi),Nanartha Nighantu (Jayarama Rayulu)

TABLE 2 : GRAMMERS

PRĀKṛIT :

5-7 C.E : Prakruta Prakasha (Vararuchi) , Prakruta Lakshana (Chanda) , Prakruta Kamadhenu (Anonymus)

12 C.E : Prakrutanushasana (Purushottama) , Siddha Hema Shabdanushasana (Hemachandra)

14 C.E : Prkruta Shabdanushasdana (Trivikrama) , Shdbhasha Chandrika (Lakshmidhara)

17 C.E : Prakruta Sarvasva (Markandeya)

SANSKRIT

4-2 B.C.E : Ashtadhyayi (Panini) , Mahabhashya-Commentary on Ashtadhyayi (Patanjali)

2 C.E : Katantra Vyakarana (Shrvavarman)

6 C.E : Mahabhashya Dipika-Commentary on Mahabhashya (Bhatruhari ), Kashika Vrutti- Commentary on Ashtadhyayi (Vamana)

7 C.E : Ashtadhyayi-Commentary (Jayaditya)

8 C.E : Kashika Vivarana Pancika –Commentary on Kashika Vrutti (Jinendra Buddivada)

9 C.E : Pada Manjari – Commentary on Kashika Vrutti (Haradatta)

11 C.E : Pradipa ( Kaiyata) , Bhasha Vrutti -Commentary on Ashtadhyayi (Purushottama Deva)

13 C.E ; Rupavatara (Dharma Keerti)

14 C.E : Mitakshara- Commentary on Ashtadhyayi (AnnaM Bhatta) , Rupamala (Vimala Sarsvati)

15 C.E : Prakriya Kaumudi (Ramachandra Shesha)

16 C.E : Shabda kaustubha (Bhattoji Dikshita) , Prakriya Sarvasva (Nayarana Bhatta)

17 C.E : Pradipodyota (Nagesha Bhatta)

TAMIL :

-3 to 10 C.E : Tolkappiam (Tolkappiyanar)

11 C.E : Viracholiyam (Buddha Mitra)

12 C.E : Neminatham (Gunaveera pandita) , Tolkappiam- Poruladigaram Commentary (Perashiyar)

13 C.E : Nannul (Bhavanadi) , Tolkappiam- Solladigaram Commentary (Senavaraiyar)

14 C.E : Tolkappiam-Commentary (Naccinarkkiniyar)

16 C.E : Tolkappiam- Solladigaram Commentary (Teyvacilaiyar , Kalladanar)

17 C.E : Tolkappiam- Solladigaram Commentary (Anonymus)

KANNADA

11 C.E : Kavyavalokana (Nagavarma)

13 C.E : Shabdamani Darpana ( Keshiraja) , Shabdanushasanam (Akalanka Deva)

17 C.E : Shabdamani Darpana-Commentary (Nitturu Nanjayya)

17 C.E : Shabdamani Darpana-Commentary (Anonymus)

TELUGU :

13 C.E : Andhra Bhasha Bhushanam (Mulaghatika Ketana)

14 C.E : Kavyalankara Chidamani (Vinnakota Peddana)

Part-6:

TABLE 3 : POETICS/PROSODY/RHETORIC

SANSKRIT :

5 C.E : Bruhatsamhita (Varahamihira)

6 C.E : Kavyalankara (Bamaha) , Kavyadarsha (Dandin)

9 C.E : Kavyalankara Sara Sangraha (Uddata) , Kavyalankara Sutravrutti (Vamana) , Kavyalankara (Rudrata), Dhvanyaloka (Anandavarhana)

10 C.E : Cahmdraloka (Jayadeva)

11 C.E : Chandonushasana (Jayakirti), Kavyamimamse (Rajashekhara) , Abhidaavrutti Maatruke (Mukula Bhatta) , Kavyakautuka (Bhatta Tauta) , Hrudaya Drapana (Bhatta Nayaka)

12 C.E :Vrutta Ratnakara (Kedara Bhatta) ,Kavya Praklasha (mummata)

15 C.E : Chando Manjari (ganga Raja)

TAMIL :

-3 to 10 C.E : Tolkappiam (Tolkappiyanar)

10 C.E : Yappurungulam + Yappurungulakkarikai (Amruta Saagara)

11 C.E : Chulamani (Gunasagarar) , Purapporul Vembamalai (Iyanaar Idanaar), Dandiyalankaram(Annonymus)

12 C.E : Ilakkana Vilakkam (Jivanana Munivar)

13 C.E : Veyyappadial (Gunaveera Panditar)

17 C.E : Chidambaram Seyyuttakkovai (Kumara Kruparar)

18 C.E : Ilakkana Vilakkam (Vaidyanathan Alvar)

KANNADA

9 C.E : Kaviraja Marga (Sri Vijaya)

10 C.E : Chandobudhi (Nagavarma-1)

11 C.E : Kavyavalokana (Nagavarma-2)

12 C.E : Udayadityalankaram (Udayaditya) , Shrungara Ratnakara (Kavi Kama)

15-16 C.E : Madhavalankara (Madhava), Kavi jihva Bandhana (Eshwara Kavi) , Kavya Sara (Abhinava Vadi Vidyananda) , Rasa Ratnakara+Apratima Veera Charite (Tirumalarya)

17 C.E : Navarasalankara (Timma) , Kuvalayananda( Jayendra)

TELUGU :

13 C.E : Kavi Vagbhadanamu (Tikkana)

14 C.E : Pratapa Rudriya (Vaidyanatha) , Kavi Janaashrayamu (Rachanna ) , Kavyalankara Chudamani ( Vinnakota Peddana) , Shrungara Dipika (Srinatha)

Part-7 :

TABLE 4 : ENCYCLOPEDIAS

SANSKRIT :

5 C.E : Bruhatsamhita (Varahamihira)

12 C.E : Abhilashitartha Chintamani ( Bhulokamalla)

TAMIL :

10 C.E : Sendan Divakaram (Divakaram) , Pingalantai (Pingalar)

12 C.E : Chudamani Nigantu (Mangala Puttiran)

KANNADA :

10-11 C.E : Lokopakara (Chavundaraya)

15 C.E : Viveka Chintamani (Nijaguna Shivayogi) , Siribhuvalaya (Kumudendu), Shivatatva Chintamani (Lakkana Dandesha)

16 C.E :Sakala Vaidya Samhita Sararnva ( Veeraraja)

TELUGU :

20 C.E :Andhra Vignana Sarvasvam ( K.V.L. Pantulu)

Part-8:

TABLE 5 : MEDICINE/VETERINARY SCIENCE/EROTICS

SANSKRIT :

-2 TO 0 C.E : Sushruta Samhite (Sushruta) , Gajayurveda (Palakapya) , Ashvashastra (Shalihotra), Vaidyaka Sarvasva ashva Chikitse(Nakula)

0 TO 2 C.E : Charaka Samhita (Charaka) , Kumara Tantra (Ravana) , Prayoga Ratnakara (Garga), Bruhaspatimata (Bruhaspati), Kamasutra (Vatsayana)

4 C.E :Ashtanga Hrudaya + Ashtanga Sangraha (Vagbhata) , Ashvayurveda Saara Sindhu (MallaDeva) ,

5-7 C.E :Matanga Leela , Shalihotra , Ashva Vaidyaka

7 to 10 C.E : Madhava Nidanam +Rugna Nischaya (Madhavakara) , Charaka samhite-Commentary (Jayadatta Suri) , Rati Rahasya (kokkoka)

11 to 13 C.E : Nibandha sangraha (Dallana) , Shabda Pradipa (Sureshvara) , Raja Nighantu+Dhanvantari Nighantu (Narahari) , Sarottama Nighantu (Anonymus) , Bhanumati (Chakradatta) , Jayamangala (Yashodhara) , Nagara sarvasva (Padmashri)

14 to 15 C.E : Madana Vinoda Nighantu (Madanapala), Sarangadhara Samhite (Sarangadhara) , RatiManjari (JayaDeva)

16 to 17 C.E : Anna Pana Vidhi (Susena) , Pathyapathya Nighantu + Bhojana Kutuhala ( Raghunatha) , Anangaranga (Kalyana Malla) , Kandarpa Chudamani (Veerabhadra Deva)

TAMIL :

13 to 18 C.E : Vaidya Shataka Nadi + Chikitsa Sara Sangraha ( Teraiyar) , Amudakalai Jnanam+Muppu+Muppuvaippu+Muppuchunnam+Charakku+GuruseyNeer+PacchaiVettu chuttiram (Agastya) , Kadai Kandam +Valalai ChuttiraM +Nadukandam (Konganavar) , Karagappa +Muppu Chuttiram +Dravakam (Nandikeshvara) , Karpam +Valai Chuttiram (Bogara)

KANNADA :

11-12 C.E : Karnata Kalyana Karaka (Jagaddala Somanatha) , Balagraha Chikitse (Devendra Muni) , Govaodya (Kirti Varma) , Madana Tilaka (Chandra Raja) , Anubhava Mukura (Janna)

14 C.E : Khagendra Mani Darpana (Mangaraja) , Ashvashastra (Abhinava Chandra)

15 C.E : Vaidyanruta (Sridhara Deva) , Vaidya Sangatya (Salva) , Ashva Vaidya (Bacarasa), Janavashya (Kallarasa)

16 C.E : Vaidya Sara Sangraha (Channaraja) , Hastayurveda-Commentary (Veerabhadraraja ) , Ashva Vaidya (Bacarasa), Janavashya (Kallarasa)

17 C.E : Vaidya Sara Sangraha (Nanjanatha Bhupala) , Vaidya Samhita Sararnava (Veeraraja ) , Shalihotra Samhita (Ramachandra), Hayasara Samuccaya (Padmana Pandita), Vaidyakanda (Brahma), Strivaidya (Timmaraja)

TELUGU :

15 C.E : Haya Lakshana Sara (manumanchi Bhatta)

TABLE 9 : ASTRONOMY/MATHEMATICS/ASTROLOGY

SANSKRIT :

3-2 B. C.E : Surya Prajnapti , Stananga Sutra , Anuyogadvara Sutra , Shatkhandagama

2-0 B. C.E : Vedanga Jyotishya (Lagada) , Bhadrabahu samhita +Surya Prajnapti-Commentary (Bhadrabahu) , Tiloyapanatti (Yatishvaracharya), Tatvarthayagama shastra (Umasvamin)

5-6 C.E : Arya Bhatiya (Arya Bhata) , Pancvha siddantika + Bruhajjataka+Laghu Jataka + Bruhatsamhita (Varahamihira) , Dashagitika Sara (Anonymus) , Aryastashata (Anonymus)

6-7 C.E : Brahma sputa Siddhanta+Kanadakadhyaya(Brahma Gupta) , Maha Bhaskariyam + Karana Kutuhala (Bhaskara-1) , Rajamruganka (Bhoja)

8 C.E : Shishayabhuvruddhi (Lallacharya) , Ganita Sara sangaraha (Mahaveeracharya) , Horasatpanchashika(Pruthuyana)

11-12 C.E : Siddhanta Shekhara (Sripati) , Siddhanta Shiromani (Bhaskara-2)

14 C.E : Yantraraja (Mahendra Suri)

15 C.E : Tantra sangraha (Neelakantha somayaji)

16 C.E : Sputa Nirnaya (Achyuta)

TAMIL :

16-18 C.E : Ganakkadigaram , Ganita Nul , Asthana Golakam , Ganita Venba , Ganita Divakaram, Ponnilakkam

KANNADA :

11 C.E : Jataka Tilaka (Sridharacharya) ,

12 C.E : Vyavahara Ganita+Kshetra Ganita+Chitra Hasuge +Jaina Ganita Sutra Tikodaaharana +Lilavati (Rajaditya)

15 C.E : Kannada Lilavati (Bala Vaidyada Cheluva)

17 C.E : Ksetra Ganita (Timmarasa) , Behara Ganita (Bhaskara)

TELUGU :

11 C.E : Ganita sara Sangrahamu (Pavaluri Mallana)

The direction of 'borrowings' from one language to another is a secondary component of the philological excursus; there is no universal linguistic rule to firmly aver such a direction of borrowing. Certainly, more work is called for in delineating the structure and forms of meluhha (mleccha) language beyond a mere list of metalware glosses.

What is the female figurine with wristlets, bracelets, anklets and hair-knot carrying in her right hand?

What is the female figurine with wristlets, bracelets, anklets and hair-knot carrying in her right hand?

ABP News

ABP News

Focus on the center-piece: brazier PLUS eye PLUS eyelid PLUS horns of markhor:

Focus on the center-piece: brazier PLUS eye PLUS eyelid PLUS horns of markhor:

Dholavira. Stone statue.

Dholavira. Stone statue.

Ur. Head band. A woman's head in diorite found in Nin-Gal temple at Ur, ca. 2150 B.C.; note the engraved modulations of the hair, elaborate bun at the back of the head and the fillet around the forehead.

Ur. Head band. A woman's head in diorite found in Nin-Gal temple at Ur, ca. 2150 B.C.; note the engraved modulations of the hair, elaborate bun at the back of the head and the fillet around the forehead.

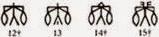

Four standard-bearers with six curls of hair.

Four standard-bearers with six curls of hair.

Ishkaran S. Bhandari

Ishkaran S. Bhandari

A quail'; painted on the top register of the jar.

A quail'; painted on the top register of the jar.

Maverick

Maverick Tony Joseph

Tony Joseph Bhagavad Gita #HDL

Bhagavad Gita #HDL

Posted at: Oct 11 2015 1:20AM

Posted at: Oct 11 2015 1:20AM

kalyan97

kalyan97

Suresh En

Suresh En

Anant Goenka

Anant Goenka

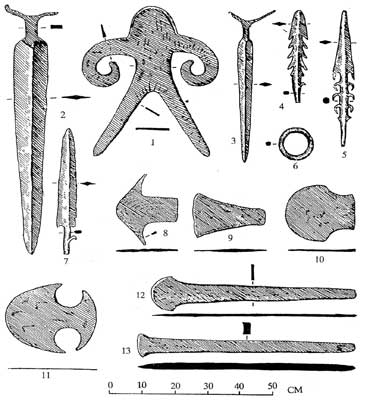

A "Sheffield of Ancient India: Chanhu-Daro's Metal Working Industry 10 x photos of copper knives, spears , razors, axes and dishe s Great New Discoveries of Ancient Indian Culture on a Virgin Prehistoric Site in Sind - further results of pioneer research at Chanu-Daro, in the Indus Valley: relics of craftsmanship, domestic life, and personal adornment in the third millennium B.C. by Ernest Mackay D. Litt, FSA, in 5 x photos of seals and seal amulets with animal designs ...

A "Sheffield of Ancient India: Chanhu-Daro's Metal Working Industry 10 x photos of copper knives, spears , razors, axes and dishe s Great New Discoveries of Ancient Indian Culture on a Virgin Prehistoric Site in Sind - further results of pioneer research at Chanu-Daro, in the Indus Valley: relics of craftsmanship, domestic life, and personal adornment in the third millennium B.C. by Ernest Mackay D. Litt, FSA, in 5 x photos of seals and seal amulets with animal designs ...