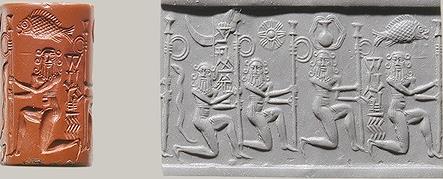

A bilingual Sumerian's seal reported by Jean-Jacques Glassner and Massimo Vidale signifies 1. name in Sumerian cuneiform script, 2. profession in Meluhha hieroglyphs of Indus Script. The profession is signified by a bull with its head bent downwards -- a signature-tune of Indus writing system. Such animals including wild animals are often shown in front of a trough -- which documents a metalwork guild.

Viewed in the context of many artifacts documenting another Meluhha Indus Script hieroglyph-multiplex of 'overflowing water from a pot' which signifies metal implements, this Sumerian seal reinforces and attests to the acculturation of Sumerian artisans to Meluhhan artisanal competence.

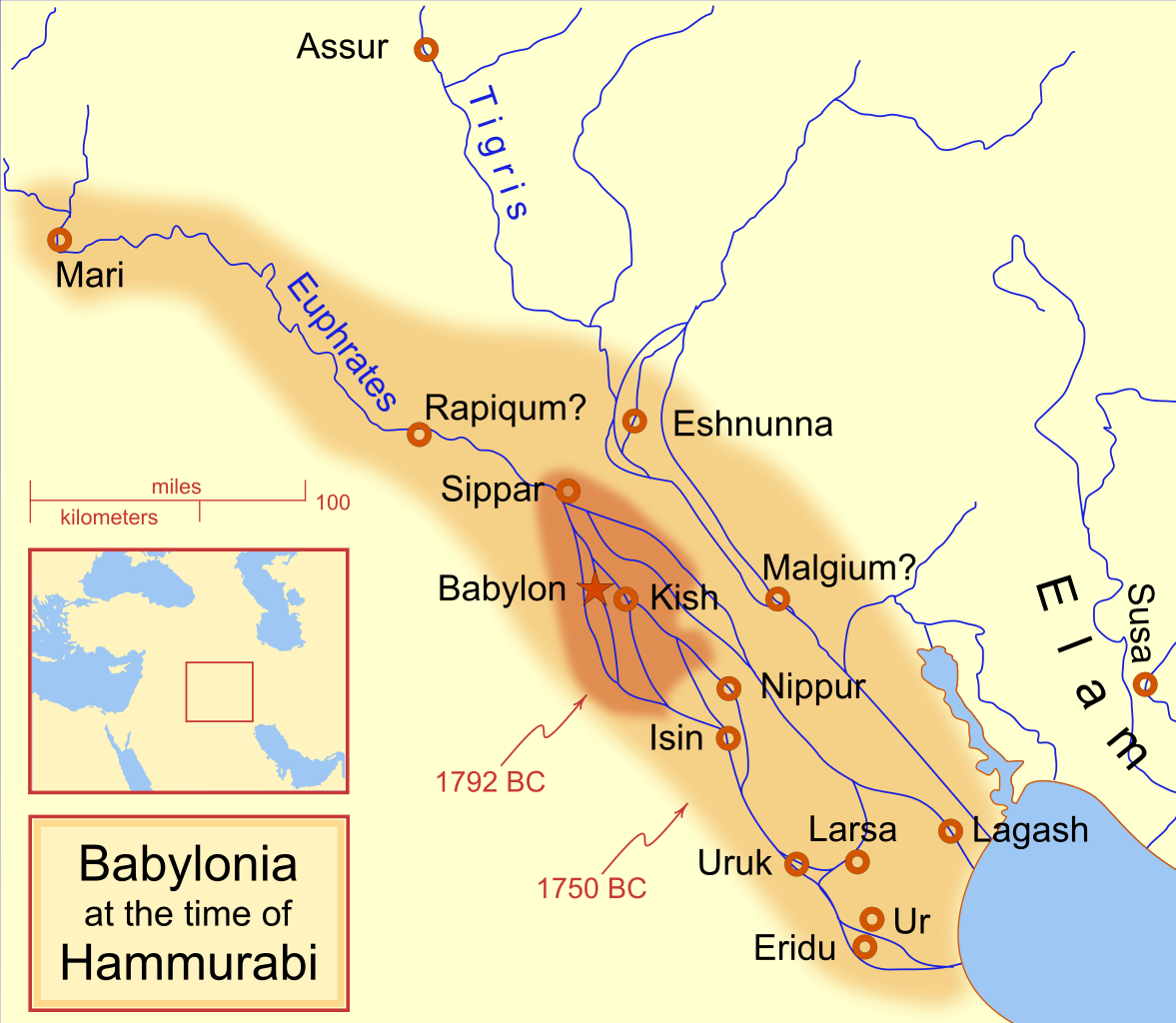

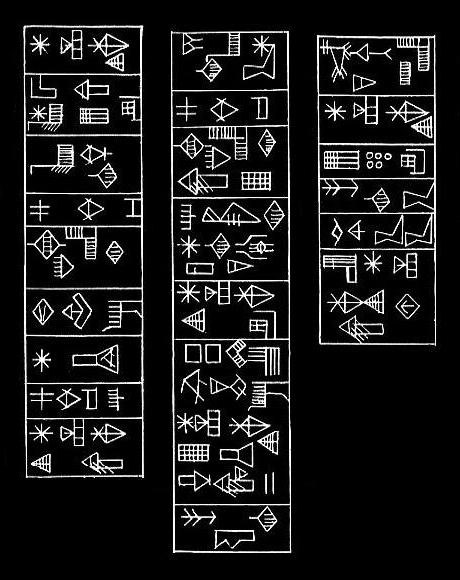

Hundreds of Indus Script hieroglyphs are signified on cylinder seals of Ancient Near East and along the Persian Gulf and along the Tin Route from Assur to Kultepe, in particular. Many examples are cited in this note; the examples record metalwork catalogues using Indus Script cipher. There are also artifacts like those documenting Ashurbanipal or Tukulti-Ninurta I and II or Gudea signified by Indus Script hieroglyph-multiplexes. There is a possibility that Assur were celebrating Meluhhan heritage, that is, the legacy of Bhāratam Janam, 'metalcaster folk', though speaking a language alien to Akkadians or Sumerians or Elamites or Semites or Amorites. Of course, there were, in the Ancient Near East, eme.bal Meluhha, ‘interpreters of the Meluhha language’.

Unfortunately, this seal bought on the market (with little provinience information) remains unpublished by Cabinet des Medailles. The significance of this seal is that it attests to the impact of Indus Script writing system on the form and function of cylinder seals in early Sumer. Use of cuneiform was necessary because the cuneiform writing system was most suitable for signifying names and offices, say, in Akkadian, Sumerian or Elamite.

Indus Script Corpora DOES NOT contain personal names and signifies only professions and metals/minerals/alloys/ metal artifacts as catalogus catalogorum, technical specification archiving developments such as cire perdue metalcastings, new alloys of the new ball game of the Tin-Bronze Age.

![]() Entry into Cabinet des Médailles, Département des Monnaies, Médailles et Antiques de la Bibliothèque nationale de France, is a department of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.

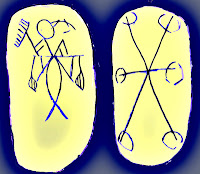

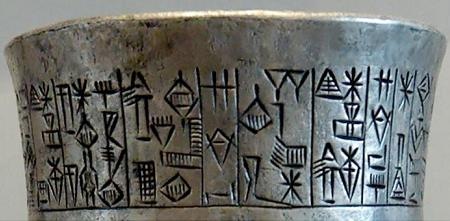

Entry into Cabinet des Médailles, Département des Monnaies, Médailles et Antiques de la Bibliothèque nationale de France, is a department of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.A Sumerian seal (not published, held in the Cabinet des Medailles of Paris) discussed by Glassner and Vidale signifies Indus script hieroglyph of a bull with a lowered head. Normally such a bull is shown in front of a trough. The rebus readings of the hieroglyph-multiplex on Indus Script Corpora are: barad, barat 'bull' Rebus: भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. (Marathi) PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'goldsmith (guild)'.

The Sumerian's name which appears on the Sumerian seal in cuneiform text is clearly using the Indus Script hieroglyph-multiplex to connote that he is an artisan in the Meluhha tradition. Maybe, he was a Sumerian artisan working in metal and wood (badhae, takshaka) and adopted the iconographic tradition of Meluhhan artisans present and trading in the territory and who documented Indus Script Corpora to signify -- as proclamations -- metalwork catalogues.

“In the third millennium, the term Meluhha designated the Indus valley and its vicinity. This toponym is a foreign one, whose transcription into cuneiform writing makes it look like a Sumerian word. Meluhha was certainly a foreign country where a foreign language was spoken: an old Akkadian cylinder seal retains the name of Shu-ilishu, eme.bal Meluhha, ‘interpreter of the Meluhha language’ (Edzard, D.O.: 1968-9, Die Inschriften der altakkadischen Rollsiegel. Archiv fur Orientforschung 22: 15, no. 33). Besides, a bilingual lexicographical list quotes a word belonging to the language of Meluhha with its Akkadian equivalent u-shamTu = GISH.U.GIR ina-Meluhhi (von Soden 1965: 1159, s.v.); behind the logogram GISH.U.GIR two Akkadian terms stand out: ashagu, one of the most widespread kinds of acacia, and eTTettu/eddetu, a widely distributed boxthorn (von Soden 1965: 77f, 266). Unfortunately, the sources quoting this botanical term are to be dated from the first millennium, a period in which the name Meluhha most generally designated Nubia or Ethiopia and no longer the Indus Valley and Gedrosia (Weidner 1952-3:10…Meluhha = Kashi, that is to say Kush); anyway, at that time, it was a learned term. Further, an old Akkadian juridical text indicates that a certain Lu.sun.zi.da lu Me.luh.ha.ke, ‘Lu.sunzida, man from Meluhha’, has been condemned to pay ten shekels of silver to somebody for having broken his tooth (Sollberger 1972: no.76). The name Lu.sunzida is hapax legomenon in Mesopotamia but it has a good Sumerian look: sun.zi, written without the divine determinative, is a well-documented epithet of the goddess Inanna…The proper name may concern somebody living in a place called Meluhha, such a place having existed at least a century later, within the Lagash territory (Parpola, Parpola and Brunswig 1977). This place has a perfect Sumerian name and there is no proof of any link between it and the foreign country of Meluhha: the Sumerian scribes may have tried to express approximately, through their own graphic system that the provision of a good Sumerian appearance, the pronunciation of a foreign word. An unpublished Harappan seal, kept in the Cabinet des Medailles at Paris, is also of great interest (to be published by D. Arnaud who kindly allowed me to mention it). Its inscription says: ‘So-and-so son of So-and-so’, the two names being typically Sumerian ones. Unfortunately, the seal was bought on the market and therefore nobody knows anything about its origin...Relationship between Mesopotamia and Meluhha went on by sea. We know of ‘Meluhha-boats’ and other ships called magillum. A so-called DAdI (a typical Akkadian name) received at Umma, in the Old Akkadian period, a viaticum as being lu.KU.ma Me.luh.ha.ka. The expression lu.KU may have one of several meanings: lu tukul: a gendarme on a Meluhha boat…the function is generally written lu.gish.tukul; lu.tush: a traveler on a Meluhha boat; lu.dab: a man in charge of a Meluhha boat…An Ur III text says, about a boat coming from Dilmun, that it conveyed several soldiers, aga.us.lugal; but we may have some doubts on their efficiency, as the text specifies that they arrived sick, tu.ra.me…Overland relationships between Mesopotamia and Meluhha also existed. An old Akkadian royal inscription known through an Old Babylonian copy says that Rimush, king of Akkade, defeated in Marhashi, possibly the province of Kerman, a coalition allying Zahara, Elam, Gupin an Meluhha…" (Glassner, Jean-Jacques, 2013, Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha: some observations on language, toponymy, anthroponymy and theonymy, in: Reade, Julian, Indian Ocean in Antiquity, Routledge, pp.236-237).

"Magan. With the toponym Magan or Makkan, the geographical horizon becomes nearer to Mesopotamia and slightly more precise. In the third and early second millennium documents, Magan designates Oman, and a.ab.ba. Ma.gan the Oman sea. In the middle of the second millennium, the sources designate south-eastern Iran by this name too. In the first millennium documents, however, the word most commonly means Egypt. It is impossible to know to which countries Esarhaddon’s title ‘king of the kings of Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha’ makes reference; the association of the three toponyms makes it clear that it is a literary and historical reminiscence…Dilmun. On the way to Mesopotamia, one finally arrives at Dilmun. Dilmun is better documented than the other areas. For the first time we have at our disposal, besides the testimony of Mesopotamian sources, some local ones too, the inscriptions from Failaka and Bahrain…The Mesopotamian viewpoint: a summary. Late fourth to early third millennium. The word NI.TUK/DILMUN occurs, linked with metal objects or fabrics; it is mentioned in professional or geographical lists of words. An administrative document of Uruk mentions a nameshda, ‘important man’, of the ‘good house/shrine of Dilmun’…the word NI.TUK/DILMUN makes reference to: a name of a craft or function; an anthroponym; a toponym. In the case of a toponym, sources are concerned with amounts of land allocated to several people. It means that a place existed, called Ni.TUK/DILMUN, not far away from Ur and belonging to its territory…Late third to early second millennium. Except for the e.Dilmuna, Inanna’s shrine in Ur, Dilmun designated, henceforth, the only geographic area bathed by the ‘Lower Sea’, a.ab.ba.igi.nim.ma, in other words, the Gulf…Mid to late second millennium. Dilmun had entered the Mesopotamian political sphere. A cylinder-seal in the British Museum mentions the name of Ushi-ana-nUri-x (the end of the name is lost in a break of the seal), who was military governor of Dilmun, GIR.NITA KUR.DILMUN.KI, and ancestor of a Kassite high official. Also, from the Assyrian sources, we learn that Tukulti-Ninurta I bore the title ‘king of Dilmun and Meluhha’…Concluding proposals…In short, the anthroponyms and the remnants of the language show that at the beginning of the second millennium the people of Dilmun was a Semitic one. An Amorite presence, among these Semites, is obviously attested. The language is Semitic, perhaps an Akkadian dialect, at least very close to it or greatly influenced by Akkadian…In Sumerian literature, Dilmun was often called ki.u.e, ‘the place where the sun rises’. ” (Glassner, Jean-Jacques, 2013, Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha: some observations on language, toponymy, anthroponymy and theonymy, in: Reade, Julian, Indian Ocean in Antiquity, Routledge, pp.237-238, 242-243).

Massimo Vidale perhaps refers to the same seal: “…seal with a cuneiform inscription (at the Cabinet des Medailles of Paris) bears an Indus bull with a lowered head, and has been preliminarily read by J.J. Glassner (2002) as Ur.Ninildum dumu Ur.gi…Ninildum is a secondary Mesopotamian divinity that appears in the famous ‘Curse of Akkad’ (perhaps composed at Nippur, and dated by some authors at the times of Naram-Sin, while others in contrast suggest a Ur III dating) and in few other later texts. What is clear is that Ninildum a goddess of carpentry and timber, called in later Babylonian texts ‘great hevenly carpenter” and ‘bearer of the shiny hatchet’. (Vidale, Massimo, Growing in a foreign world: for a history of the ‘Meluhha villages’ in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BCE’, Panaino A. & A. Piras, eds., Melammu Symposia IV, Milano, 2004, pp.264-265). http://a.harappa.com/sites/g/files/g65461/f/201402/Vidale-Indus-Mesopotamia.pdf

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/persian-gulf-seals-and-meluhha.html Chrobak, Marzena, For a tin ingot: the archaeology of oral interpretation in:Przekladaniec. A journal of literary translation. Special issue 2013: 87-101 http://www.ejournals.eu/pliki/art/1690/

Mitchell, TC, 1986, Indus and Gulf type seals from Ur. In Al Khalifa, Haya Ali and M. Rice, eds.1986, Bahrain through the ages: the archaeology, London, Routledge (KPI): 278-85

A possible ancient Maritime Tin Route between Hanoi and Haifa

“In pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, Bahrain depended for its prosperity on its harbor. This was the base of the pearling fleet; and also, because of the excellent shelter and the abundance of fresh water and food on the island of AwAl, a convenient staging-post for ships bound for India from Iraq. Bahrain was also itself a natural terminus for sea-trade from the Far East, because the nearby mainland province of Hajar, which was also called Al-Bahrain, was well irrigated and accessible to trade-routes from Nejd, Hejaz and the Mediterranean. Two of the great seasonal fairs of pre-Islamic times were held here, at Hajar and Al-Mushaqqar; and earlier, in classical times, there stood here the great trading city of Gerrha, not yet certainly identified, but thought by some to have been located at the extensive ruins of Al-ThAj in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia. The Greek botanist Theophrastus, writing in the early third century BCE, refers to the ships built on Bahrain, then called the Island of Tylus. They were made of a timber, probably Indian teak, which was said to last for 200 years. Bahrain has continued until modern times as a leading centre in the Gulf of ship-building and of sea-going commerce, and indeed has outlasted some of its early rivals, like Ubullah and SirAf...|t is probable that Persian Xoroastrians, known to the Chinese as Posse, had already established trading links with Canton in ptr-Islamic times. They were joined by Arab traders, called Ta-shih by the Chinese, by about CE 750. However, the trade with China only became of important scale after about 800, and it declined rapidly after the 870s following internal disturbances both in Abbasid Iraq and Tang China. Al-Ubullah and Al-Basra were destroyed at this time, and Siraf declined rapidly in importance. The trade from the East moved instead to Bahrain, Aden and the Red Sea, as Fustat in Fatimid Egypt replaced Abbasid Baghdad as the most prosperous city of the Middle East." (Brice, William C., Traditional techniques of navigation in the seas of Bahrain, in: Al Khalifa, Haya Ali and M. Rice, eds.1986, Bahrain through the ages: the archaeology, London, Routledge (KPI)

PERSIAN GULF

i. IN ANTIQUITY

The Persian Gulf (24°-30°30′N, 48°-56°30′E) is a shallow, epi-continental sea approximately 1,000 km long and 200-350 km wide, narrowing to about 60 km across at the Straits of Hormuz (Hormoz). Depths average only 35 m (max. ca. 100 m), and a rate of 37-40% salinity is considered high. During the last glacial maximum (c. 70,000-17,000 BP) when worldwide sea-levels were up to 120 m lower than at present, the bed of the Persian Gulf was a valley floor through which the combined waters of the Tigris, Euphrates and Karun (Kārun) ran as a single river draining into the Straits of Hormuz. With the onset of the Flandrian Transgression about 17,000 BP, sea-levels in the Gulf valley began to rise and by 7000 BP a sea-level comparable to that of the present day was reached (Lambeck, 1996, p. 49). Although sea-levels have fluctuated slightly since that time (Sanlaville et al., 1987), the main point of relevance with regard to understanding the archaeology of the surrounding landmasses is that any site of the Palaeolithic, Epipalaeolithic or Neolithic along the ancient ‘Tigris-Euphrates-Karun to Hormuz’ river which may have been in what was then southernmost Iran or eastern Arabia were submerged by the rising sea-levels of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene (Teller et al., 2000). Consequently, it would be unusual, except on highly elevated ground, to find any prehistoric remains pre-dating the Chalcolithic, but this is in fact the case.

To date, no Neolithic remains have been found anywhere along the Persian Gulf coast of Iran. The earliest archaeological remains yet identified on the coast of Iran consist of sherds of Mesopotamian Ubaid (ʿObayd) 1-2 (Eridu, Haji Muhammad) type picked up by M. E. Prickett and A. Williamson on the surface of Halilah (Ḥalila), a prehistoric site on the Bushehr (Bušehr) peninsula (Oates, 2004, p. 92). These may be roughly dated to about 5500-5000 BCE (cf. Porada et al., 1992, p. 92). On the Arabian coast, dozens of sites in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.), characterized by bifacial, finely pressure-flaked arrowheads, belong to the so-called Arabian bifacial tradition (Uerpmann, 1992). Because of the presence of domesticated sheep and goat on those sites which have been excavated, this tradition is considered ‘Neolithic’ (Kallweit, 2003), even though there is no evidence of domesticated plant use and the societies who left these remains are probably best understood as herders who engaged in some hunting (hence the preponderance of arrowheads) to supplement their source of protein, conserving their herds for the exploitation of their secondary products (milk, cheese, hair/fleece), as opposed to hunter-gatherers. The earliest dates for this complex come from some of the offshore islands of Abu Dhabi and cluster in the period between ca. 5300-5800 BCE (Shepherd Popescu, 2003, Table 1). As the east Arabian littoral is well outside the natural habitat of either sheep or goat both species must have been introduced into the area, most probably from the aceramic Neolithic communities of the southern Levant (Uerpmann, Uerpmann and Jasim, 2000). Marine resources (shellfish, fish, dugong, etc), of course, were extremely important to the diet of the inhabitants of the Arabian coast (Shepherd Popescu, 2003; Beech, 2

(Daniel T. Potts)

Originally Published: July 20, 2005

MARITIME TRADE

i. PRE-ISLAMIC PERIOD

In comparison with Mesopotamia, which provides an abundance of cuneiform sources as well as physical evidence in the form of imports bearing on the question of pre-Islamic maritime trade, Persia has far less incontrovertible proof that maritime trade was an important factor in her ancient economy. Whereas the cities of southern Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley had obvious outlets to the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea, those of the Persian interior, in most cases, did not. Yet, it is important to stress that Susa lies on the Karḵa (Elamite Ulā, Akk. Ulaya) river which, as the accounts of Alexander’s departure from Susa in 324 BCE and of Nearchus’ arrival from the Indus attest, was navigable in antiquity (and even in the 19th century) up to the Karun (Kārun), from which point onward access to the Persian Gulf was unproblematic (Potts, 1999a; Bosworth, 1988). The same general conditions apply, therefore, to sites like Chogha Zambil (Čoḡā Zanbil) (albeit using the Diz river in the first instance). Sites in the Shushtar (Šuštar) region had ready access to the head of the Gulf by following the Karun, while further east, in the Behbahān or Rām Hormoz regions, the Marun river provided an outlet. Once we move into the highlands of Fārs, it becomes easier to reach the Persian Gulf at Bushehr (Bušehr, ancient Liyan), by going overland down through a series of passes which eventually lead to the coast. This approach would have been equally relevant for prehistoric sites in the Marv Dašt plain (e.g. Tell-e Bakun), for Elamite sites (e.g. Tell-e Mālyān, ancient Anshan (Anšān)) and for Achaemenid and later sites (e.g. Persepolis, Estakhr (Eṣṭaḵr), and eventually Shiraz). As records from the Islamic period show, routes also linked e.g. Shiraz with Sirāf; the interior of southern Fars (Fārs) with Lenga; Sirjān with present-day Bandar ʿAbbās (a name which it acquired only in the early 17th century CE; before that, it was known as Shahru (Šahru)); Jiroft with Hormoz via Mināb, etc. (Aubin 1969; Yajima and Kamioka 1988), but the relevance of these coast-hinterland routes for the pre-Islamic era is unclear. Nevertheless, a study of archaeological evidence found at sites in land-locked parts of Persia and literary sources confirms that trade with the Persian Gulf region was vigorous enough to effect the import of numerous types of materials.

A number of pre-Sargonic (mid-3rd millennium BCE) commercial texts from Tello (ancient Girsu) in southern Mesopotamia mention barley, flour, livestock, textiles, sandals, and other commodities being sent to Elam (Lambert, 1953, pp. 62-65) without, however, specifying whether the goods traveled by land or sea. In one Telloh text (RTC 21; dated to Urukagina 5), however, a má-Elam or “Elamite ship/ship from Elam” is mentioned (Lambert, 1953, p. 115; Heimpel, 1987, pp. 71-72). Although a designation of this sort is open to several interpretations: is it a reference to a type of ship called “Elamite” which nevertheless might have been built in Mesopotamia (cf. Brussels sprouts grown and eaten outside of Belgium) or to an actual ship from Elam? The fact that ships from Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha are all attested in cuneiform sources suggests that ships from Elam may well have traveled to cities like Girsu by entering the Persian Gulf and sailing up the Shatt al-Arab (Šaṭṭ al-ʿArab) as well. What such Elamite ships may have looked like we cannot say. Scholars have long appreciated that the maritime regions associated in cuneiform texts with Babylonia, such as Dilmun (eastern Arabia/Bahrain), Magan (Oman peninsula), and Meluhha (Indus Valley), had their own styles of sea craft (e.g. Pinches 1886-87; cf. Potts 1995).

An Ur III text from Tello (MVN 10, 149 II.6-9; dated to Shulgi 34) contains a reference to the transport of troops from Anshan (Englund, 1990, pp. 132-3; not sacks containing goods transshipped from a ship arriving from Anshan as suggested by Heimpel, 1987, p. 33). Another text from Tello records the provisions sent in the second year of Shu-Sin’s reign when his daughter was married to a prince of Anshan. Because the “controller” of the shipment bore the title “fisherman” (sal-˙u-ba), it has been suggested that the goods went by ship from Girsu to Anshan via Susa (Sigrist and Butz 1986, p. 28; R. K. Englund (personal communication) is doubtful of the translation “fisherman” for the Sumerian term used in this text). Yet another Ur III text from Telloh qualifies six ships with thirty-six seamen making a two-month journey as “sesame ships from Susa” (Sigrist and Butz 1986, p. 29), i.e. ships from Susa containing sesame. It must be remembered, however, that Susa and its hinterland at this time were part of the Ur III empire (Steinkeller 1987, p. 37); thus, we are not dealing with a case of free trade between Susa and a Mesopotamian city-state. Nevertheless, a mace head from Susa with a dedication to Shulgi from Urniginmu, identified as a “maritime merchant,” makes it clear that specialists in sea trade were indeed resident at Susa in the Ur III period (Amiet, 1986a, p. 146). This individual’s name, however, strongly suggests he was a Mesopotamian, not an Elamite.

It is generally assumed that most trade between the Indus Valley (ancient Meluhha?) and western neighbors proceeded up the Persian Gulf rather than overland. Although there is no incontrovertible proof that this was indeed the case, the distribution of Indus-type artifacts on the Oman peninsula, on Bahrain and in southern Mesopotamia makes it plausible that a series of maritime stages linked the Indus Valley and the Gulf region. If this is accepted, then the presence of etched carnelian beads, a Harappan-style cubical stone weight, and a Harappan-style cylinder seal at Susa (Amiet 1986a, Figs. 92-94) may be evidence of maritime trade between Susa and the Indus Valley in the late 3rd millennium BCE. On the other hand, given that similar finds, particularly etched carnelian beads, are attested at landlocked sites including Tepe Hissar (Tappe Heṣār), Shah Tepe (Šāh-Tappe), Kalleh Nisar (Kalla Nisār), Jalalabad (Jalālābād), Marlik (Mārlik) and Tepe Yahya (Tappe Yaḥyā) (Possehl 1996, pp. 153-54), other mechanisms, including overland traffic by peddlers or caravans, may account for their presence at Susa.

The involvement of Harappan middlemen may have effected the distribution of other commodities in Persia not normally associated with sea borne trade, including tin and lapis-lazuli, from sources in Afghanistan (cf. Pigott et al, 2003, pp. 164-65; Weeks, 2003, p. 186). In each case commodities could have been transported from the Indus Valley by sea and then entered the Elamite economic system via the riverine route from the head of the Gulf to Susa or the overland route from Liyan, near modern Bushehr (Potts, 2003), northwards to Anshan. Certainly the function of Liyan as a coastal port involved in cross-Gulf trade would seem clear after the discovery there, during excavations in 1913, of soft-stone vessels of a distinctly Omani type, comparable examples of which are known from Susa and Tepe Yahya, as well. Alternatively, tin and lapis lazuli from Afghanistan could have been shipped on Meluhhan vessels to the Oman peninsula and then sold onwards to customers in Elam. In this case the small numbers of Persian imports in the Oman peninsula, such as two complete Kaftari beakers from Tell Abraq, with close parallels at Tell-e Mālyān and Liyan (Potts 2003), might be regarded as by-products of the more important trade in tin (Weeks 2003, p. 184).

Whether Susa was also being supplied with copper from the mountains of Oman during the middle and late 3rd millennium BCE is unclear. Although it has been claimed that metal objects from the “vase à la cachette,” an Early Dynastic hoard discovered at Susa, were made of copper imported from Oman (Berthoud et al., 1980), this assertion has been called into question by other scholars (Seeliger et al., 1985, p. 643) and a Persian origin for the copper used to make these finds cannot be excluded (Hauptmann et al., 1988, p. 34; cf. Pigott 1999, p. 80).

Other evidence from Susa demonstrates the existence of commercial ties in the early 2nd millennium BCE with Dilmun (modern Bahrain), most probably via the maritime route from the mouth of the Karun across the Gulf to the main site of Qalat al-Bahrain (Qalʿat al-Baḥrayn). One of the most important entrepJ̌ts in the Gulf region during the late 3rd and early 2nd millennium, Dilmun was noted for transshipping commodities which originated further east, such as copper from Magan (Oman) and wood from “foreign lands,” most probably including Meluhha (Indus Valley). An early-2nd-millennium contract from Susa records a loan to an individual named Ekiba who was about to depart on a business trip (Lambert 1976). The fact that the tablet was impressed with a typical Dilmun seal strongly suggests that the transaction involved a purchase of goods to be made in Dilmun, or that Ekiba himself was a Dilmunite, and this interpretation is bolstered by the discovery at Susa of four Dilmun stamp seals; six copies of Dilmun seals made in locally-produced bitumen compound (Amiet, 1986b, Figs. 92-5; Connan and Deschesne 1996); and a clay sealing bearing the impression of a Dilmun stamp seal, most probably from a package sealed in Dilmun before shipment to Susa (Potts, 1999b, p. 179). A further early-2nd-millennium cuneiform text from Susa that dates to the reign of the sukkalmah Kutir-Nahhunte I records the arrival of 17.5 minas of silver said to have been “brought by the Dilmunite” (de Meyer 1966, p. 117). These references are interesting in light of the presence of diagnostic Dilmunite pottery (red-ridged ware) amongst the shards recovered at Tul-e Peytul (ancient Liyan) by M. Pézard in 1913 (Pézard 1914, Pl. 8). Moreover, in the Sumerian myth Enki and Ninhursag, Elam is listed as one of eight countries that traded with Dilmun (Kramer 1977, p. 59).

A number of shell-finds from archaeological sites in Iran attest to the movement of raw shells and/or finished shell objects from the Persian Gulf or Arabian Sea. A tomb excavated by de Mecquenem on the Acropole at Susa, of probable early-3rd-millennium date, has yielded a group (perhaps the remains of a bracelet or necklace) of seven rings made from Conus sp. (Tosi and Biscione, 1981, p. 51, Fig. 12). A 5.7 cm long, 3.6 cm high, flat mother-of-pearl (Pinctada margaritifera) inlay carved to resemble a Przewalski’s horse (Idem, p. 49, Fig. 9) from the early Susa excavations of J. de Morgan has been dated to the late 3rd millennium BCE on stylistic grounds. A shell bangle of uncertain date from Susa, originally identified as Fasciolaria trapezium (Idem, p. 51, Fig. 13) is more likely to have been made of Turbinella pyrum, a species common in the Indus Valley (Gensheimer 1984, p. 71). Another object of uncertain date from Susa is a necklace made of Dentalium octogonum andDentalium variabile shells (Tosi and Biscione 1981, p. 51, Fig. 14). Other necklaces, found in graves of unknown date, were composites of Conus ebraeus, Oliva bulbosa,Pinctada margaritifera, and Engina mendicaria shells (Idem, 1981, pp. 52-53, Figs. 15-16). A lamp of Cypraea tigris, also of uncertain date, is also known from Susa (Idem, p. 54, Fig. 17).

On the central Persian Plateau, an early Iron Age grave (ca. 1350-1000 BCE) in cemetery A at Tepe Sialk (Tappe Sialk) has yielded a button of an unidentified, large gastropod (Idem, pp. 55, Fig. 19) while tomb 94 in cemetery B at Sialk produced a necklace conmposed of Engina mendicaria, Dentalia octogonum, and several unidentified shells (Idem, Fig. 20).

At Tepe Yahya in southeastern Persia a nearly complete, un-worked shell of the pearl oyster (Pinctada margaritifera) was found in a 3rd-millennium context (Idem, Fig. 21) while the same species was used to fashion a 3rd-millennium, cruciform stamp seal (Idem, p. 56, Fig. 22), carved and perforated plaques (Idem, p. 57, Figs. 25-26) and pendants or large beads (Idem, pp. 58-59, Figs. 26-27). Xancus pyrumwas used at Tepe Yahya to carve both a cruciform and a square, compartmented stamp seal (Idem, pp. 56-57, Figs. 23-24). Beads of Conus quercinus, Conus ebraeus,and Polynices mamilla, all dating to the 4th and 3rd millennia, were also recorded (Idem, p. 63, Figs. 37-40). Beads made from the latter species are also known from Tepe Hissar (Idem, p. 64, Fig. 42).

In Persian Sistān, 3rd millennium contexts at Shahr-e Sokhta (Šahr-e Suḵta) have yielded rings of Conus pusillus, Engina mendicaria, and Conus sp.; worked fragments of Xancus pyrum, Cypraea tigris, and Pinctada margaritifera; beads ofPolynices mamilla and Engina mendicaria (Idem, pp. 65-67, Figs. 46-54); and bracelets or bangles of Xancus pyrum (Durante 1979, Fig. 3). Finally, a perforatedSpondylus exilis, perhaps intended to be used as a pendant, as well as examples ofArchitectonica perspectiva, Polynices mammilla, Cypraea turdus, Cassis rufa,Oliva bulbosa, and Arca inaequivalvis were also found in the late 3rd/early-2nd-millennium contexts during the excavations at Bampur (Biggs 1970, p. 333). The presence of shell waste fragments at both Tepe Yahya and Shahr-e Sokhta proves conclusively that shell-working was carried out at both sites (Durante 1979, pp. 323 ff). All of this material implies the existence of maritime sources in the Persian Gulf and/or Arabian Sea and suggests that organized trade and transport mechanisms may have facilitated the movement of shells from the points at which they were gathered to the settlements of the Persian interior (Durante 1979, pp. 341-42).

Cross-Gulf trade is also suggested by the presence of Persian archaeological material at sites on the Arabian side of the Persian Gulf. Large quantities of carved chlorite vessels and vessel fragments in the “Intercultural Style” or série ancienne, found in such profusion in Jiroft (Majidzadeh 2003) and known to have been manufactured in southeastern Persia, have been found on the island of Tārut, off the coast of eastern Saudi Arabia (Zarins, 1978; cf. Potts, 1989, p. 18; Pittman, 1984, p. 20). Black-on-gray pottery of analytically proven Persian provenance, dating to the late 3rd millennium, has been discovered in both the Oman peninsula (e.g. Tell Abraq, Umm an-Nar (Omm al-Nār), Hili) and eastern Arabia (Dhahran tombs; Méry, 2000). Archaeological finds of bitumen, in the form of balls, basket-lining, and otherwise unidentifiable fragments, from Qalat al-Bahrain, Saar (Sār), Karranah (Karrāna), and Buri on Bahrain, spanning the period from the late 3rd millennium BCE to the Parthian era, are now known to have been made of bitumen from sources in Fars, Khuzestan (Ḵuzestān), and/or Lorestān (Connan et al., 1998). This material clearly demonstrates the ongoing supply of Persian bitumen to Bahrain over the course of two millennia (note also that other pieces date to the 13th-15th centuries CE). Also of late 3rd millennium date and of probable east Persian origin is a small number of alabaster vessels, including two from the foundation deposit of temple IIa at Barbar (Bārbār) on Bahrain and two from plundered graves on Tārut island (Potts, 1986, pp. 283-84; Potts, 1989, pp. 20-22).

Several complete Kaftari beakers have been found in the United Arab Emirates with late 3rd-millennium, Umm an-Nar-style graves at Tell Abraq in Sharjah (Šarja) and Shimal (Šemāl) in Ras al-Khaimah (Raʾs al-Ḵayma). Possible Kaftari shards (which could date anywhere between 2200 and 1600 BCE) have been identified on Failaka (Faylaka), in the bay of Kuwait; in some of the tombs near Dhahran (Ẓahrān) in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia; and at Qalat al-Bahrain (Potts, 2003, p. 157). Second millennium Elamite cylinder seals have been discovered on Failaka at the head of the Persian Gulf (Kjærum, 1983, pp. 162-70) and at Tell Abraq (Potts, 1990, Figs. 150-51).

When we move into the Iron Age and later periods, the evidence becomes increasingly sparse. A text like DSf (Lecoq, 1997, pp. 234-37) contains no clues as to the means by which the exotic materials (e.g. ebony, sissoo wood) employed in the construction of Darius’ palace at Susa were actually transported, but it is unlikely that they arrived by other than royal command and hence they should be excluded from a discussion of “normal” trade. Likewise, it is not clear how Herodotus’ statement (Hist. 4.44) should be interpreted, to the effect that, following Scylax’s exploration of the Indus, Darius I opened the Indian Ocean to his ships (Salles, 1996). It is, however, interesting to note that a late Achaemenid grave at Susa, dated by numismatic evidence to about 350-32 BCE, contained three strands of 400-500 pearls interspersed with gold spacer beads (de Morgan 1905; Tallon 1992, p. 242). A second necklace from the same grave, made of sixty-five agate beads (Tallon 1992, p. 249), attests to the continued supply of high-quality semi-precious stones from, in all probability, an Indian source. Agate, like carnelian, is most likely to have reached Persia via maritime commercial channels, although overland trade cannot be excluded as a possibility.

With regard to the Parthian period, the anonymous Periplus of the Erythraean Sea,apparently written during the 1st century CE by a Greek-speaking mariner of Roman Egypt (Casson 1989), which contains little intelligence on the Persian Gulf itself, identifies “Ommana” as a market town of Persia (sec. 36). Regardless of where Ommana was located (scholars and the ancient sources themselves disagree as to whether it was on the Arabian or the Iranian side of the Gulf), the entrepJ̌t was a center of importing and exporting, receiving sandalwood, teak, and ebony from Barygaza in India (often bearing goods from even further east), and frankincense from Kane in south Arabia. Unfortunately, the text is ambiguous about Ommana’s exports, mentioning slaves, gold, dates, wine, clothing, purple, and pearls amongst the goods shipped from Kane and Ommana, without distinguishing which town sent what commodities.

Certainly pearls are associated in many sources with the Persian Gulf, most commonly with Bahrain (e.g. Athenaeus, Deipnosophistai 3.146). During the Sasanian period, pearls were highly prized by Sasanian rulers (Simpson, 2003), and Pseudo-Moses of Khorene states that Rishahr (Rišahr) was the source of the best pearls and “Perlenedelsteine” (Marquart, 1901, p. 138), a term which may refer to a type of stone like agate. Sasanian investment in the fortifications at Rishahr (ancient Rev-Ardashir (Rēv-Ardašir) and Sirāf (Whitehouse and Williamson, 1972, pp. 33-42) may well reflect a desire to bolster their position as commercial entrepJ̌ts through which goods passed from the East. In this regard, moreover, the fact that Māni passed through Rev-Ardashir on his way from India to Mesopotamia is surely relevant (Sundermann 1981, pp. 56-57; cf. Gropp 1991, p. 86). Commercial maritime traffic with India and China is also indicated by an anecdote related in the Chronicle of Seert (Scher, 1908, p. 324) according to which Yazdegerd I (r. 399-421) sent the Nestorian catholicos Aḥdai to Fars, charged with the task of investigating the alleged theft of pearls by pirates preying on the fleets trafficking between the Persian Gulf, India, and China (cf. Whitehouse and Williamson, 1972, p. 43). The existence of such commercial traffic between the Persian Gulf and the East means that other commodities besides pearls must also be considered as a potential part of Gulf maritime trade. Thus, for example, although Chinese silk entering Persia is usually associated with the continental Silk Road it is also possible that at least some of it reached the region by sea. Conversely, some of the Sasanian glass that wound up in graves in China, Korea, and Japan (Whitehouse, 1996) may well have traveled by ship rather than caravan.

Bibliography:

P. Amiet, L’âge des échanges inter-iraniens, 3500-1700 avant J.-C., Paris, 1986a.

Idem, “Susa and the Dilmun Culture,” in H. A. Al Khalifa and M. Rice, eds., Bahrain Through the Ages: The Archaeology, London, 1986b, pp. 262-68.

J. Aubin, “La survie de Shilhāu et la route du Khunj-ō-fāl,” Iran 7, 1969, pp. 21-37.

T. Berthoud, S. Bonnefous, M. Dechoux, and J. FranÇaix, “Data Analysis: Towards a Model of Chemical Modification of Copper from Ores to Metal,” in R. T. Craddock, ed., Proceedings of the XIXth Symposium on Archaeometry, London, 1980, pp. 87-102.

H. E. J. Biggs, “Report on Mollusks Collected by the Expedition to Bampur,” in B. de Cardi, Excavations at Bampur, A Third Millennium Settlement in Persian Baluchistan, 1966, New York, N.Y., 1970, pp. 333-34.

A. B. Bosworth, “Nearchus in Susiana,” in W. Will and J. Heinrichs, eds., Zu Alexander d. Gr.: Festschrift G. Wirth zum 60. Geburtstag am 9.12.86, Amsterdam, 1988, pp. 541-66.

L. Casson, The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary, Princeton, N.J., 1989.

J. Connan and O. Deschesne, Le bitume à Suse, Paris, 1996.

J. Connan, P. Lombard, R. Killick, F. Højlund, J.-F. Salles, and A. Khalaf, “The Archaeological Bitumens of Bahrain from the Early Dilmun Period (c. 2200 BC) to the Sixteenth Century AD: A Problem of Sources and Trade,” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 9, 1998, pp. 141-81.

S. Durante, “Marine Shells from Balakot, Shahr-i Sokhta and Tepe Yahya: Their Significance for Trade and Technology in Ancient Indo-Iran,” in M. Taddei, ed.,South Asian Archaeology 1977, Naples, 1979, pp. 317-44.

R. K. Englund, Organisation und Verwaltung der Ur III-Fischerei, Berlin, 1990.

T. R. Gensheimer, “The Role of Shell in Mesopotamia: Evidence for Trade Exchange with Oman and the Indus Valley,” Paléorient 10, 1984, pp. 65-73.

G. Gropp, “Christian Maritime Trade of Sasanian Age in the Persian Gulf,” in K. Schippmann, A. Herling, and J.-F. Salles, eds., Golf-Archäologie, Buch am Erlbach, 1991, pp. 83-88.

A. Hauptmann, G. Weisgerber, and H.-G. Bachmann, “Early Copper Metallurgy in Oman,” in R. Maddin, ed., The Beginning of the Use of Metals and Alloys, Cambridge, 1988, pp. 34-51.

W. Heimpel, “Das untere Meer,” Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 77, 1987, pp. 22-91.

P. Kjærum, Failaka/Dilmun, the Second Millennium Settlements I, The Stamp and Cylinder Seals, Aarhus, Denmark, 1983.

S. N. Kramer, “Commerce and Trade: Gleanings from Sumerian Literature,” Iraq39, 1977, pp. 59-66.

M. Lambert, “Textes commerciaux de Lagash,” Revue d’Assyriologie 47, 1953, pp. 57-69, 105-20.

Idem, “Tablette de Suse avec cachet du Golfe,” Revue d’Assyriologie 70, 1976, pp. 71-72.

P. Lecoq, Les inscriptions de la Perse achéménide, Paris, 1997.

J. Marquart, Ērānšahr nach der Geographie des Ps. Moses Xorenac‘i, Berlin, 1901.

Y. Majidzadeh, Jiroft, the Earliest Oriental Civilization, Tehran, 2003.

S. Méry, Les céramiques d’Oman et l’Asie moyenne: Une archéologie des échanges à l’âge du Bronze, Paris, 2000.

L. de Meyer, “Een Tilmoenit te Suse,” Orientalia Gandensia 3, 1966, pp. 115-17.

J. de Morgan, “Découverte d’une sépulture Achéménide à Suse”, MDP 8, 1905, pp. 51-52.

M. Pézard, Mission à Bender-Bouchir, Paris, 1914.

V. C. Pigott, “The Development of Metal Production on the Iranian Plateau: An Archaeometallurgical Perspective,” in Idem, ed., The Archaeometallurgy of the Ancient World, Philadelphia, Pa., 1999, pp. 73-106.

Idem, H. C. Rogers, and S. K. Nash, “Archaeometallurgical Investigations at Malyan,” in N. F. Miller and K. Abdi, eds., Yeki bud, yeki nabud: Essays on the Archaeology of Iran in Honor of William M. Sumner, Los Angeles, Calif., 2003, pp. 161-75.

T. G. Pinches, “The Babylonians and Assyrians as Maritime Nations,” The Babylonian and Oriental Record 1, 1886-87, pp. 41-42.

H. Pittman, Art of the Bronze Age, New York, N.Y., 1984.

G. L. Possehl, “Meluhha,” in J. Reade, ed., The Indian Ocean in Antiquity, London, 1996, pp. 133-208.

D. T. Potts, “The Booty of Magan,” Oriens Antiquus 25, 1986, pp. 271-85.

Idem, Miscellanea Hasaitica, Copenhagen, 1989.

Idem, A Prehistoric Mound in the Emirate of Umm al-Qaiwain: Excavations at Tell Abraq in 1989, Copenhagen, 1990.

Idem, “Watercraft of the Lower Sea,” in U. Finkbeiner, R. Dittmann, and H. Hauptmann, eds., Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte Vorderasiens: Festschrift für Rainer Michael Boehmer, Mainz, 1995, pp. 559-71.

Idem, “Elamite Ulā, Akkadian Ulaya, and Greek Choaspes: A Solution to the Eulaios Problem,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, N.S., 13, 1999a, pp. 27-44.

Idem, The Archaeology of Elam, Cambridge, 1999b. Idem, “Anshan, Liyan and Magan circa 2000 BCE,” in N. F. Miller and K. Abdi, eds., Yeki bud, yeki nabud: Essays on the Archaeology of Iran in Honor of William M. Sumner, Los Angeles, Calif. 2003, pp. 156-59.

J.-F. Salles, “Achaemenid and Hellenistic Trade in the Indian Ocean,” in J. Reade, ed.The Indian Ocean in Antiquity, London, 1996, pp. 251-67.

A. Scher, Patrologia Orientalis II: Histoire Nestorienne (Chronique de Séert), Paris, 1908.

T. C. Seeliger, E. Pernicka, G. A. Wagner, F. Begemann, S. Schmitt-Strecker, C. Eibner, Ö. Öztunali, and I. Baranyi, “Archäometallurgische Untersuchungen in Nord- und Ostanatolien,” Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums32, 1985, pp. 597-659.

M. Sigrist and K. Butz, “Wirtschaftliche Beziehungen zwischen der Susiana und Südmesopotamien in der Ur-III-Zeit,” Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran 19, 1986, pp. 27-31.

St. J. Simpson, “Sasanian beads: The Evidence of Art, Texts and Archaeology,”Ornaments from the Past: Bead Studies after Beck, ed. I. C. Glover, H. Hughes-Brock, and J. Henderson, London, 2003, pp. 59-78.

P. Steinkeller, “The Administrative and Economic Organization of the Ur III State: The Core and the Periphery,” in McG. Gibson and R. D. Biggs, eds., The Organization of Power: Aspects of Bureaucracy in the Ancient Near East, Chicago, Ill., 1987, pp. 19-41.

W. Sundermann, Mitteliranische manichäische Texte kirchengeschichtlichen Inhalts, Berlin, 1981.

F. Tallon, “The Achaemenid Tomb on the Acropole,” in P. O. Harper, J. Aruz, and F. Tallon, eds., The Royal City of Susa, New York, N.Y., 1992, pp. 242-52.

M. Tosi and R. Biscione, eds., Conchiglie: Il commercio e la lavorazione delle conchiglie marine nel medio oriente dal IV al II millennio a. C., Rome, 1981.

L. R. Weeks, Early Metallurgy of the Persian Gulf: Technology, Trade, and the Bronze Age World, Boston, Mass., and Leiden, 2003.

D. Whitehouse, “Sasanian Maritime Activity,” in J. Reade, ed., The Indian Ocean in Antiquity, London, 1996, pp. 339-49.

Idem and A. Williamson, “Sasanian Maritime Trade,” Iran 11, 1973, pp. 29-49.

H. Yajima and K. Kamioka, Caravan Routes Across the Zagros Mountains in Iran, Tokyo, 1988.

J. Zarins, “Steatite Vessels in the Riyadh Museum,” Atlal 2, 1978, pp. 65-94.

August 15, 2009

(Daniel T. Potts)

Originally Published: August 15, 2009

![A photograph of a fish market in Bahrain]() The hypothesis is that the 'Persian Gulf seals' some of which are referenced in the embedded documents relate to trade with Meluhha since many Meluhha hieroglyphs can be identified on such seals. See the interpretation of 'fish-eyes' in Philosophy of symbolic forms in Meluhha cipher.

The hypothesis is that the 'Persian Gulf seals' some of which are referenced in the embedded documents relate to trade with Meluhha since many Meluhha hieroglyphs can be identified on such seals. See the interpretation of 'fish-eyes' in Philosophy of symbolic forms in Meluhha cipher.

The term 'barbarian' originates from the Greek word βάρβαρος (barbaros). Hence the Greek idiom "πᾶς μὴ Ἕλλην βάρβαρος" (pas mē Hellēn barbaros) which literally means "whoever is not Greek is a barbarian". The Ancient Greek word βάρβαρος (barbaros), "barbarian", was an antonym for πολίτης (politēs), "citizen" (from πόλις - polis, "city-state"). The sound ofbarbaros onomatopoetically evokes the image of babbling (a person speaking a non-Greek language)(Pagden, Anthony (1986). "The image of the barbarian. The fall of natural man: the American Indian and the origins of comparative ethnology. Cambridge University Press.) The earliest attested form of the word is theMycenaean Greek pa-pa-ro, written in Linear B syllabic script. (Johannes Kramer, Die Sprachbezeichnungen 'Latinus' und 'Romanus' im Lateinischen und Romanischen, Erich Schmidt Verlag, 1998, p.86). In Homer's works, the term appeared only once (Iliad 2.867), in the form βαρβαρόφωνος (barbarophonos) ("of incomprehensible speech"). The verb βαρβαρίζειν (barbarízein) in ancient Greek meant imitating the linguistic sounds non-Greeks made or making grammatical errors in Greek. बर्बर mfn. (also written वर्वर) stammering (Monier-Williams, p. 722)

म्लेच्छ any person who does not speak Sanskrit and does not conform to the usual Hindu institutions, ignorance of Sanskrit , barbarism (Monier-Williams, p. 837) Thus, in the Indian tradition, a barbara may be a mleccha, that is, a Meluhha speaker. The two Meluhha's mentioned in ancient cuneiform texts of 3rd millennium and 1st millennium, respectively, may refer to mleccha speakers (India) and to Barbara speakers (North Africa).

See a review of seven works in: Reflections on the history and archaeology of Bahrain (1985) by D.T. Potts

Dilmun appears first in Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets dated to the end of fourth millennium BC, found in the temple of goddess Inanna, in the city of Uruk. The adjective Dilmunis used to describe a type of axe and one specific official; in addition there are lists of rations of wool issued to people connected with Dilmun. (Dilmun and Its Gulf Neighbours by Harriet E. W. Crawford, page 5.) There is both literary and archaeological evidence of extensive trade between Ancient Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley civilization (probably correctly identified with the land called Meluhha in Akkadian). Impressions of clay seals from the Indus Valley city of Harappa were evidently used to seal bundles of merchandise, as clay seal impressions with cord or sack marks on the reverse side testify. A number of these Indus Valley seals have turned up at Ur and other Mesopotamian sites. The "Persian Gulf" types of circular, stamped (rather than rolled) seals known from Dilmun, that appear at Lothal inGujarat, India, and Failaka, as well as in Mesopotamia, are convincing corroboration of the long-distance sea trade. What the commerce consisted of is less known: timber and precious woods, ivory, lapis lazuli, gold, and luxury goods such as carnelian and glazed stone beads, pearls from the Persian Gulf, shell and bone inlays, were among the goods sent to Mesopotamia in exchange for silver, tin, woolen textiles, olive oil and grains. Copper ingots from Oman and bitumen which occurred naturally in Mesopotamia may have been exchanged for cotton textiles and domestic fowl, major products of the Indus region that are not native to Mesopotamia. Instances of all of these trade goods have been found. The importance of this trade is shown by the fact that the weights and measures used at Dilmun were in fact identical to those used by the Indus, and were not those used in Southern Mesopotamia.- "the ships of Dilmun, from the foreign land, brought him wood as a tribute"

(Larsen, Curtis E. (1983). Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society. University of Chicago Press, p. 33.)Mesopotamian trade documents, lists of goods, and official inscriptions mentioning Meluhha supplement Harappan seals and archaeological finds. Literary references to Meluhhan trade date from the Akkadian, the Third Dynasty of Ur, and Isin-Larsa Periods (c. 2350–1800 BC), but the trade probably started in the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2600 BC). Some Meluhhan vessels may have sailed directly to Mesopotamian ports, but by the Isin-Larsa Period, Dilmun monopolized the trade.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Bahrain

Strabo, the Greek historian, geographer and philosopher mentioned that the Phoenicians came from Bahrain where they have similar gods, cemeteries and temples. Herodotus's account (written c. 440 BC) refers to the Phoenicians originating from Bahrain. (History, I:1).According to the Persians best informed in history, the Phoenicians began the quarrel. These people, who had formerly dwelt on the shores of the Erythraean Sea (the eastern part of the Arabia peninsula), having migrated to the Mediterranean and settled in the parts which they now inhabit, began at once, they say, to adventure on long voyages, freighting their vessels with the wares of Egypt and Assyria... —Herodotus

![File:AssyrianWarship.jpg]()

Phoenicians men their ships in service to Assyrian king Sennacherib, during his war against the Chaldeansin the Persian Gulf, ca. 700 BCE.

Bahrain was referred to by the ancient Greeks as Tylos, the centre of pearl trading. "The name Tylos is thought to be a Hellenisation of the Semitic, Tilmun (from Dilmun). The term Tylos was commonly used for the islands until Ptolemy’s Geographia when the inhabitants are referred to as 'Thilouanoi'.Some place names in Bahrain go back to the Tylos era, for instance, the residential suburb of Arad in Muharraq, is believed to originate from "Arados", the ancient Greek name for Muharraq island."(Jean Francois Salles in Traces of Paradise: The Archaeology of Bahrain, 2500BC-300AD in Michael Rice, Harriet Crawford Ed, IB Tauris, 2002, p.132)

"Bahrain (Arabic: البحرين, Bahreyn), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain (Arabic: مملكة البحرين) is a small island country situated near the western shores of the Persian Gulf. It is an archipelago of 33 islands, the largest being Bahrain Island, at 55 km (34 mi) long by 18 km (11 mi) wide. Saudi Arabia lies to the west and is connected to Bahrain by the King Fahd Causeway. Iran lies 200 km (124 mi) to the north of Bahrain, across the Gulf. The peninsula of Qatar is to the southeast across the Gulf of Bahrain.

![File:Map of Bahrain.svg]() Barbar, Bahrain, a village in the north of Bahrain. Close to this village, a temple dated to ca. 3000 BCE has been found, caleld Barbar temple. "Inhabited since ancient times, Bahrain occupies a strategic location in the Persian Gulf. It is the best natural port between the mouth of the Tigris, Euphrates Rivers and Oman, a source of copper in ancient times. Bahrain may have been associated with the Dilmun civilisation, an important Bronze Age trade centre linking Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bahrain

Barbar, Bahrain, a village in the north of Bahrain. Close to this village, a temple dated to ca. 3000 BCE has been found, caleld Barbar temple. "Inhabited since ancient times, Bahrain occupies a strategic location in the Persian Gulf. It is the best natural port between the mouth of the Tigris, Euphrates Rivers and Oman, a source of copper in ancient times. Bahrain may have been associated with the Dilmun civilisation, an important Bronze Age trade centre linking Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bahrain

Bahrain is believed to be the site of the ancient land of the Dilmuncivilisation." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portal:Bahrain

In Arabic, Bahrayn is the dual form of bahr ("sea"), so al-Bahrayn means "the Two Seas". It is possible that the word barbar may be related to bahr 'sea', as sea-people. It is instructive that both barbara and mleccha (Meluhha) are used as languages but with ungrammatical, variant pronunciations, making them dialectical variants as lingua franca as opposed to grammatically correct, literary versions of languages.

31% of agriculture related words in Hindi have no etymological connection that can be found (Masica, Colin, 1978, Aryan and non-Aryan elements in north Indian agriculture: in: Madhav M Deshpande and Peter Edwin Hook, eds., Aryan and non-aryan in India. Michigan papers on south and southeast Asia, 14:55-151. Ann Arbor: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, The Univ. of Michigan: 134-138). Bailey notes that Ir. daha-, OPers. dahA refer to ‘man’ or ‘men’. (Bailey, Harold Water, 1973, Mleccha-, Baloc, and GadrOsia in: Hansman, John, 1973, A Periplus of Magan and Meluhha. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Univ. of London 36(3): 584-587). See: Levitt, Stephan Hillyer, The ancient Mesopotamian place name ‘Meluhha’, pp. 135-176

http://ojs.tsv.fi/index.php/StOrE/article/download/51787/16150![]() | File:Harappa seals nm india 04.JPG DescriptionHarappa seals nm india 04.JPG English: Some Seals of the HarappanCivilization on display in the National Museum Date 5 January 2014, 09:48:24 (2,192 × 2,095 (1.69 MB)) - 13:12, 27 December 2014 |

![]() | File:Harappa seals nm india 06.JPG DescriptionHarappa seals nm india 06.JPG English: Some Seals of the HarappanCivilization on display in the National Museum Date 5 January 2014, 09:50:04 (4,849 × 2,676 (4.55 MB)) - 13:12, 27 December 2014 |

![]() | File:Harappa seals nm india 05.JPG DescriptionHarappa seals nm india 05.JPG English: Some Seals of the HarappanCivilization on display in the National Museum Date 5 January 2014, 09:48:32 (2,766 × 2,102 (2.12 MB)) - 13:12, 27 December 2014 |

![]() | File:Harappa seals nm india 03.JPG DescriptionHarappa seals nm india 03.JPG English: Some Seals of the HarappanCivilization on display in the National Museum Date 5 January 2014, 09:48:20 (4,984 × 1,470 (2.57 MB)) - 13:11, 27 December 2014 |

![]() | File:Harappa seals nm india 02.JPG DescriptionHarappa seals nm india 02.JPG English: Some Seals of the HarappanCivilization on display in the National Museum Date 5 January 2014, 09:41:43 (4,429 × 2,663 (4.28 MB)) - 13:11, 27 December 2014 |

![]() | File:Harappa seals nm india 01.JPG DescriptionHarappa seals nm india 01.JPG English: Some Seals of the HarappanCivilization on display in the National Museum Date 5 January 2014, 09:48:13 (4,758 × 1,173 (2.04 MB)) - 13:12, 27 December 2014 |

![]() | File:Harappa seals nm india 07.JPG DescriptionHarappa seals nm india 07.JPG English: Some Seals of the HarappanCivilization on display in the National Museum Date 5 January 2014, 09:50:16 (4,249 × 2,882 (4.45 MB)) - 13:12, 27 December 2014 |

![]() | File:Dholavira gujarat.jpg the two most remarkable excavations of the Indus Valley Civilization or Harappanculture, dating back to 4500 years ago. While the other site, Lothal, is (3,056 × 2,292 (1.13 MB)) - 20:03, 26 October 2012 |

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=harappan+seal&title=Special%3ASearch&go=Go&uselang=enIndus Valley seals showing an unidentified animal with some form of foot support,British Museum. ![]() Copper artifacts. Gola Dhoro.

Copper artifacts. Gola Dhoro.![]() Copper knives with bone handles.

Copper knives with bone handles. ![]() Gola Dhoro.

Gola Dhoro.![]()

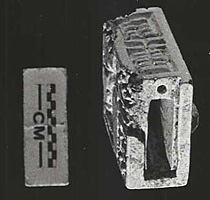

![Figure 9]() Gola Dhoro. A unique steatite inscribed unicorn seal with a socket perhaps for attaching a lid. "One of the steatite seals discovered this season has decorative linear patterns incised on three sides and a deep, scooped out rectangular socket-like cavity on the fourth side and originally it perhaps had a sliding lid to cover the socket. These are in addition to the usual engraved inscription and the unicorn figure on the seal and therefore it appears to be a unique one, since such seals with socket have not been reported from any other Harappan site so far."

Gola Dhoro. A unique steatite inscribed unicorn seal with a socket perhaps for attaching a lid. "One of the steatite seals discovered this season has decorative linear patterns incised on three sides and a deep, scooped out rectangular socket-like cavity on the fourth side and originally it perhaps had a sliding lid to cover the socket. These are in addition to the usual engraved inscription and the unicorn figure on the seal and therefore it appears to be a unique one, since such seals with socket have not been reported from any other Harappan site so far."

Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. Gola dhoro location and other sites with sources of principal traded commodities (After Maps 1 and 3 in: Jane Mcintosh, 2008, The ancient Indus valley: new perspectives,ABC-CLIO

![]() Seals and sealings. Gola Dhoro, Begasra.

Seals and sealings. Gola Dhoro, Begasra.Citadel mound. Mohenjo-daro. See across to the Greath Bath and behind it the 'granary'.

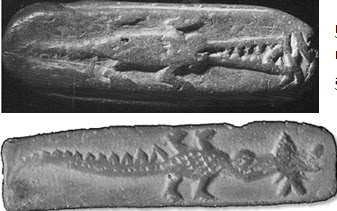

https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/oimp32.pdfMeluhha 'crocodile' hieroglyph in Ancient Near East (Eshnunna or Tell Asmar) and India![]() Location of Eshnunna (Tell Asmar), Sumerian cultural milieu in vicinity of Susa

Location of Eshnunna (Tell Asmar), Sumerian cultural milieu in vicinity of Susa![]() Votive Statues, from the Temple of Abu, Tell Asmar,c.2500 BC, limestone, shell, and gypsum

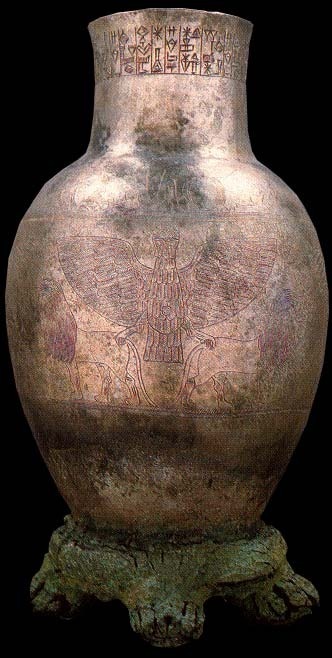

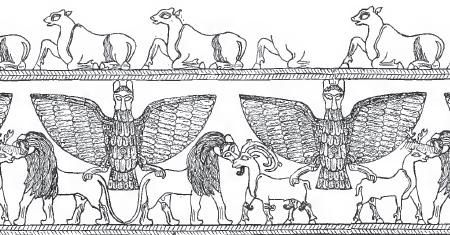

Votive Statues, from the Temple of Abu, Tell Asmar,c.2500 BC, limestone, shell, and gypsum![]() Asmar 12 sculpture. The hieroglyph-multiplex shows a palm tree trunk and a storage vase on the top register. I suggest that the hieroglyph-multiplex signifies tamar'palm tree' karaḍī 'safflower' Rebus: tAmra karaDa'copper hard alloy'. I realize that this will be critiqued as an article of faith. Maybe, but I do not know if there are cognates to the Hebrew word tamar'palm tree' in other languages of the Ancient Near East including the Slavic languages which have a record of med 'copper' cognate with meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Munda). I am suggesting the use of Indus Script cipher also on Warka vase hieroglyph-multiplex in the context of a metalwork catalogue. I would respectfully review any alternative decipherments of the Warka vase narrative signified by Indus Script hieroglyph-multiplex of antelope, tiger, reed, head of bull [face muha 'mouth, face' (Prakritam) Rebus: muhA 'quantity of smelted metal' (Santali)].

Asmar 12 sculpture. The hieroglyph-multiplex shows a palm tree trunk and a storage vase on the top register. I suggest that the hieroglyph-multiplex signifies tamar'palm tree' karaḍī 'safflower' Rebus: tAmra karaDa'copper hard alloy'. I realize that this will be critiqued as an article of faith. Maybe, but I do not know if there are cognates to the Hebrew word tamar'palm tree' in other languages of the Ancient Near East including the Slavic languages which have a record of med 'copper' cognate with meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Munda). I am suggesting the use of Indus Script cipher also on Warka vase hieroglyph-multiplex in the context of a metalwork catalogue. I would respectfully review any alternative decipherments of the Warka vase narrative signified by Indus Script hieroglyph-multiplex of antelope, tiger, reed, head of bull [face muha 'mouth, face' (Prakritam) Rebus: muhA 'quantity of smelted metal' (Santali)].

Part of Speech: Noun Masculine

Transliteration: tamar

Phonetic Spelling: (taw-mawr')

Short Definition: trees http://biblehub.com/hebrew/8558.htm![]() Safflower bracelet. From the stone reliefs of Ashurnasirpal II. Wrist with a safflower bracelet: safflower karaḍī as fire-god karandi

Safflower bracelet. From the stone reliefs of Ashurnasirpal II. Wrist with a safflower bracelet: safflower karaḍī as fire-god karandi

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/07/tin-road-meluhha-aratta-assur-kanesh.html

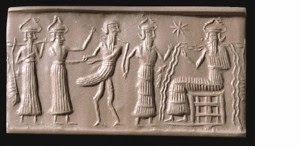

करडी [ karaḍī ] f (See करडई) Safflower: also its seed. (Marathi) karaṭa2 m. ʻ Carthamus tinctorius ʼ lex.Pk. karaḍa -- m. ʻ safflower ʼ, °ḍā -- f. ʻ a tree like the karañja ʼ; M. karḍī, °ḍaī f. ʻ safflower, Carthamus tinctorius and its seed ʼ.M. karḍel n. ʻ oil from the seed of safflower ʼ(CDIAL 2788, 2789)![]() Shu-ilishu cylinder seal. Note the water-vessel held by the woman accompanying the Meluhha merchant. The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris.A Mesopotamian cylinder seal referring to the personal translator of the ancient Indus or Meluhan language, Shu-ilishu, who lived around 2020 BCE during the late Akkadian period. The late Dr. Gregory L. Possehl, a leading Indus scholar, tells the story of getting a fresh rollout of the seal during its visit to the Ancient Cities Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2004.

Shu-ilishu cylinder seal. Note the water-vessel held by the woman accompanying the Meluhha merchant. The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris.A Mesopotamian cylinder seal referring to the personal translator of the ancient Indus or Meluhan language, Shu-ilishu, who lived around 2020 BCE during the late Akkadian period. The late Dr. Gregory L. Possehl, a leading Indus scholar, tells the story of getting a fresh rollout of the seal during its visit to the Ancient Cities Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2004.

கரண்டை² karaṇṭai, n. < karaṇḍa. Water- vessel, used by ascetics; கமண்டலம். சிமிலிக் கரண்டையன் (மணி. 3, 86). करोट [p= 255,3] m. a basin , cup L.

![]() British Museum. 22.5 cm h. Wallet shaped chlorite of BMAC. Arye 'lion' Rebus: Ara 'brass' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'..

British Museum. 22.5 cm h. Wallet shaped chlorite of BMAC. Arye 'lion' Rebus: Ara 'brass' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'..

करण्ड mf(ई L. )n. ( Un2. i , 128) a basket or covered box of bamboo wicker-work BhP. Bhartr2. &c (Samskritam) Karaṇḍaka [fr. last] a box, basket, casket, as dussa˚ M i.215=S v.71=A iv.230 (in simile); S iii.131; v.351 cp. Pug 34; J i 96; iii.527; v.473 (here to be changed into koraṇḍaka); DA i.222 (vilīva˚); SnA 11.Karaṇḍa (m. nt.) [cp. Sk. karaṇḍa, ˚ka, ˚ikā. The Dhātu- mañjūsā expls k. by "bhājanatthe"] 1. a basket or box of wicker -- work Mhvs 31, 98; Dāvs v.60; DhAiii.18; -- 2. the cast skin, slough of a serpent D i.77 (=DA i.222 ahi -- kañcuka) cp. Dial. i.88. (Pali) గరిడియ (p. 0358) [ gariḍiya ] gariḍiya. [from Skt. కరండము.] n. A wallet, or basket for food, &c. బుట్ట. M. III. vii. 221. భార. అర. vii. (Telugu)káraṇḍa1 m.n. ʻ basket ʼ BhP., °ḍaka -- m., °ḍī -- f. lex.Pa. karaṇḍa -- m.n., °aka -- m. ʻ wickerwork box ʼ, Pk. karaṁḍa -- , °aya -- m. ʻ basket ʼ, °ḍī -- , °ḍiyā -- f. ʻ small do. ʼ; K. kranḍa m. ʻ large covered trunk ʼ,kronḍu m. ʻ basket of withies for grain ʼ, krünḍü f. ʻ large basket of withies ʼ; Ku. kaṇḍo ʻ basket ʼ; N. kaṇḍi ʻ basket -- like conveyance ʼ; A. karṇi ʻ open clothes basket ʼ; H. kaṇḍī f. ʻ long deep basket ʼ; G. karãḍɔ m. ʻ wicker or metal box ʼ, kãḍiyɔ m. ʻ cane or bamboo box ʼ; M. karãḍ m. ʻ bamboo basket ʼ, °ḍā m. ʻ covered bamboo basket, metal box ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; Si. karan̆ḍuva ʻ small box or casket ʼ. -- Deriv. G. kãḍī m. ʻ snake -- charmer who carries his snakes in a wicker basket ʼ.(CDIAL 2789) kronḍu, Skt. karaṇḍa-, a basket (Kashmiri)

Meluhha hieroglyph 'overflowing pot' with rebus reading: metal tools, pots and pans

![]()

m1656 Mohenjodro Pectoral. kāṇṭamkāṇḍam காண்டம்² kāṇṭam, n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர். துருத்திவா யதுக்கிய குங்குமக் காண் டமும் (கல்லா. 49, 16). Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘metal tools, pots and pans’ (Marathi)

<lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. @B24310. #20851. Re<lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) The hieroglyph clearly refers to the metal tools, pots and pans of copper. The pot carried by the woman accompanying the Meluhha sea-faring merchant could also be a hieroglyphic rebus reading of kāṇṭam signifying metal pots and pans and tools.

M177. Kidin-Marduk, son of Sha-ilima-damqa, the sha reshi official of Burnaburiash, king of the world Untash-Napirisha

![]()

Cuneiform texts attest to the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer. [The Meluḫḫa Village: Evidence of Acculturation of Harappan Traders in Late ThirdMillennium Mesopotamia?Author(s): Simo Parpola, Asko Parpola, Robert H. Brunswig, Jr.Source:Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 20, No. 2 (May, 1977),pp. 129-165].

[quote] MAGAN and MELUHHA Geographical terms for regions in the distant south and southeast of Mesopotamia. Both names first appear in royal inscriptions of the Akkad period; “ships from Magan and Meluhha” were said to have brought goods to the quays of Akkad and other cities. It has been proposed that Magan referred to the coast of Oman along the Persian Gulf, rich in copper and dates, and Meluhha in the Indus valley. In Neo-Assyrian texts of the first millennium B.C., Magan and Meluhha probably designated the African coast of the Red Sea (Upper Egypt and Sudan). --Historical Dictionary of Mesopotamia[unquote]

The major contribution made by Meluhhans in Sumer was tin as an alloying mineral to create tin-bronzes (to complement naturally-occurring copper + arsenic ores for arsenic bronzes).

Meluhhan artisans in Sumer used Indus writing to create metal-ware catalogs. This is exemplified by the 'water-buffalo' glyph used on some cylinder seals.

kaṇḍ ‘buffalo’; rebus: kaṇḍ ‘stone (ore)’. Meluhha was the habitat for the water-buffalo.

While cuneiform script was used to write names syllabically or to record benedictions ('short invocations for divine help'), rest of the writing (for e.g. on cylinder seals) used hieroglyphs.

Cylinder seal image. The water-god in his sea house (Abzu) (ea. 2200 B.C.). On the extreme right is Enki, the water-god, enthroned in his sea house. To the left is Utu, the sun-god, with his rays and saw. The middle deity is unidentified. (British Museum)

These images are explained in terms of associated sacredness of Enki, who in Sumerian mythology (Enki and Ninhursag) is associated with Abzu where he lives with the source sweet waters.

Gypsum statuette. "A Gypsum statuette of a priestess or goddess from the Sumerian Dynastic period, most likely Inanna. ...She holds a sacred vessel from which the life-giving waters flow in two streams. Several gods and goddesses are shown thus with running water, including Inanna, and it speaks of their life-giving powers as only water brings life to the barren earth of Sumeria. The two streams of water are thought to stand for the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. This is the earliest of the group of statues and dates to c. 2600-2300 B.C. 150 mm tall."

![]()

Cylinder seal explained as Enki seated on a throne with a flowing stream full of fish, ca. 2250 BCE (BM 103317).British Museum.

2605 (#KJ Roach's thesis). Sealed tablet. Susa. Illituram, son of Il-mishar, servant of Pala-isshan

#KJ Roach M9 Mesopotamia

#Roach 2168 Cream limestone. Susa.

The streams of water flowing the naked, bearded person are the signature tune of the times in Ancient Near East. This glyptic or overflowing pot held by Gudea, appears on hundreds of cylinder seals and friezes of many sites.

Overflowing water from a pot is a recurrent motif in Sumer-Elam-Mesopotamian contact areas – a motif demonstrated to be of semantic significance in the context of lapidary-metallurgy life activity of the artisans.

The rebus readings are:

కాండము [ kāṇḍamu ] kānḍamu. [Skt.] n. Water. నీళ్లు (Telugu) kaṇṭhá -- : (b) ʻ water -- channel ʼ: Paš. kaṭāˊ ʻ irrigation channel ʼ, Shum. xãṭṭä. (CDIAL 14349). kāṇḍa ‘flowing water’ Rebus: kāṇḍā ‘metalware, tools, pots and pans’. lokhaṇḍ (overflowing pot) ‘metal tools, pots and pans, metalware’ lokhãḍ ‘overflowing pot’ Rebus: ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ (Gujarati) Rebus: लोखंड lokhaṇḍ Iron tools, vessels, or articles in general. lo ‘pot to overflow’. Gu<loRa>(D) {} ``^flowing strongly''.கொட்டம்¹ koṭṭam Flowing, pouring; நீர் முதலியன ஒழுகுகை. கொடுங்காற் குண்டிகைக் கொட்ட மேய்ப்ப (பெருங். உஞ்சைக். 43, 130) கொட்டம் koṭṭam < gōṣṭha. Cattle- shed (Tamil)

koṭṭam flowing, pouring (Tamil). Ma. koṭṭuka to shoot out, empty a sack. ? Te. koṭṭukonipōvu to be carried along by stream or air current.(DEDR 2065).

Gudea’s link with Meluhha is clear from the elaborate texts on the two cylinders describing the construction of the Ninĝirsu temple in Lagash. An excerpt: 1143-1154. Along with copper, tin, slabs of lapis lazuli, refined silver and pure Meluḫa cornelian, he set up (?) huge copper cauldrons, huge …… of copper, shining copper goblets and shining copper jars worthy of An, for laying (?) a holy table in the open air …… at the place of regular offerings (?). Ninĝirsu gave his city, Lagaš

Chlorite vessel found at Khafajeh: Ht 11.5 cm. 2,600 BCE, Khafajeh, north-east of Baghdad (Photo from pg. 69 of D. Collon's 1995 Ancient Near Eastern Art).

![]() Impression of seal on tablets from Kanesh (After Larsen, Mogens Trolle and Moller Eva, Five old Assyrian texts, in: D. Charpin - Joannès F. (ed.), Marchands, Diplomates et Empereurs. Études sur la civilization Mésopotamienne offertes à Paul Garelli (Éditions research sur les Civilisations), Paris, 1991, pp. 214-245: figs. 5,6 and 10.)

Impression of seal on tablets from Kanesh (After Larsen, Mogens Trolle and Moller Eva, Five old Assyrian texts, in: D. Charpin - Joannès F. (ed.), Marchands, Diplomates et Empereurs. Études sur la civilization Mésopotamienne offertes à Paul Garelli (Éditions research sur les Civilisations), Paris, 1991, pp. 214-245: figs. 5,6 and 10.)

![]()

![]() Workers from Elam, Susa, Magan and Meluhha were deployed by Gudea, the ruler of Lagaṣ, to build The Eninnu, the main temple of Girsu, c. 2125 BCE. We are dealing with Indian sprachbundwhen we refer to Meluhha. This sprachbund has a remarkable lexeme which is used to signify a smithy, as also a temple: Kota. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. Toda. kwala·l Kota smithy Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer; Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133).

Workers from Elam, Susa, Magan and Meluhha were deployed by Gudea, the ruler of Lagaṣ, to build The Eninnu, the main temple of Girsu, c. 2125 BCE. We are dealing with Indian sprachbundwhen we refer to Meluhha. This sprachbund has a remarkable lexeme which is used to signify a smithy, as also a temple: Kota. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. Toda. kwala·l Kota smithy Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer; Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133).

![]()

Gudea Basin. Water overflowing from vases. : The Representation of an Early Mesopotamian Ruler ... By Claudia E. Suter "The standing statue N (Fig. 5) holds a vase from which four streams of water flow down on each side of the dress into identical vases depicted on the pedestal, which are equally overflowing with water. Little fish swim up the streams to the vase held by Gudea. This statue evidently shows the ruler in possession of prosperity symbolized by the overflowing vase." (p.58)ayo 'fish' (Munda) Rebus: ayo 'iron' (Gujarati); ayas'metal' (Skt.) Together with lo, 'overflow', the compound word can be read as loh+ayas. The compound lohāyas is attested in ancient Indian texts, contrasted withkṛṣṇāyas, distinguishing red alloy metal (bronze) from black alloy metal (iron alloy). ayaskāṇḍa is a compound attested in Pāṇini; the word may be semantically explained as 'metal tools, pots and pans' or as alloyed metal.

A baked-clay plaque from Ur, Iraq, portraying a goddess; she holds a vase overflowing with water ('hé-gál' or 'hegallu') is a symbol of abundance and prosperity. (Beijing World Art Museum) Fish in water on statue, on viewer's right. Gudea's Temple Building "The goddesses wit overflowing vases. (Fig.8). The large limestone basin (SV.7) restored by Unger from twenty-six fragments is carved in relief on its outside. It shows a row of goddesses walking on a stream of water. Between them they are holding vases from which water flows down into the stream. These, in turn, are fed with water poured from vases which are held by smaller-scale goddesses hovering above. All goddesses wear long pleated dresses, and crowns with a single horn pair. There are remains of at least six standing and four hovering goddesses. Considering the importance the number seven plays in Gudea's inscriptions, Unger's reconstruction of seven goddesses of each type is credible. The inscription on the basin, which relates its fashioning, designates it as a large S'IM, a relatively rare and only vagueely understood term, perhaps to be read agarinX. The fashioning of one or more S'IM is also related in the Cylinder inscriptions, and the finished artifact is mentioned again in the description of the temple...Since the metaphor paraphrasing the basin refers to th ceaseless flow of water, it is possible that the basin(s) mentioned in the account of Eninnu's construction is (are) identical with the fragmentary remains of the one (perhaps two?) actually found within the area of Gudea's Eninnu, as Unger presumed. Several similar and somewhat intuitive identifications of the goddesses with the overflowing vases have been proposed: Heuzey saw personifications of the Euphrates and Tigris; Unger saw personifications of sources and rain clouds that form the Tigris and identified them with Ningirsu and Baba's seven daughters; van Buren saw personifications of higher white clouds and lower rain clouds whom she assigned to Ea's circle. Neither are the seven (not fourteen!) daughters of Ningirsu and Baba ever associated with water, nor can fourteen personified clouds be made out in Ea's circle...The clue must be the overflowing vase which van Buren correctly interpreted as a symbol of abundance and prosperity. This interpretation is corroborated by the Gottertsypentext which states that the images of Kulullu is blessing with one hand (ikarrab) and holding abundance (HE.GAL) in the other. The protective spirit Kulullu is usually associated with abundance and divine benevolence, and may be reminiscent of the god bestowing the overflowing vase upon a human petititioner in much earlier presentation scenes. The narrative context in which the goddess with the overflowing vase occurs is confined to presentations of a human petititioner to a deity. The Akkadian seal fo the scribe Ili-Es'tar shows her accompanying the petitioner, not unlike a Lamma.![]() Fig. 33 Urnamma stela.

Fig. 33 Urnamma stela.![]()

On the Urmamma Stela, she is hovering over the offering of flowing water to the ruler by the enthroned deity. In this scene the goddess underlines the gift bestowed on the ruler, and figures as a personification of it, while on the seal she may have implied and guaranteed that the petitioner who offers an antelope (?) is pleading for and will receive blessings of abundance in return. The basin of Gudea is dedicated to Ningirsu, and may be understood as a plea for prosperity as well as a boast of its successful outcome."(Claudia E. Suter, 2000, Gudea's Temple Building: the representation of an early Mesopotamian Ruler in text and image, BRILL., II.c.i.d, pp. 62-63).|

![]() ![]() Location.Current Repository Location.Current Repository

|

|

gud. ' ea guda ' ea warrior ' emphasis/the best "The best warrior". http://evans-experientialism.freewebspace.com/ling_sumerian.htm

Inscription on base of skirt- God commands him to build house. Gudea is holding plans. Gudea depicted as strong, peaceful ruler. Vessel flowing with life-giving water w/ fish. Text on garment dedicates himself, the statue, and its temple to the goddess Geshtinanna. According to the inscription this statue was made by Gudea, ruler of Lagash (c. 2100 BCE) for the temple of the goddess Geshtinanna. Gudea refurbished the temples of Girsu and 11 statues of him have been found in excavations at the site. Nine others including this one were sold on the art market. It has been suggested that this statue is a forgery. Unlike the hard diorite of the excavated statues, it is made of soft calcite, and shows a ruler with a flowing vase which elsewhere in Mesopotamian art is only held by gods. It also differs stylistically from the excavated statues. On the other hand, the Sumerian inscription appears to be genuine and would be very difficult to fake. Statues of Gudea show him standing or sitting. Ine one, he rests on his knee a plan of the temple he is building. On some statues Gudea has a shaven head, while on others like this one he wears a headdress covered with spirals, probably indicating that it was made out of fur. Height 61 cm. The overflowing water from the vase is a hieroglyph comparable to the pectoral of Mohenjo-daro showing an overflowing pot together with a one-horned young bull and standard device in front. The diorite from Magan (Oman), and timber from Dilmun (Bahrain) obtained by Gudea could have come from Meluhha.

"The goddess Geshtinanna was known as “chief scribe” (Lambert 1990, 298– 299) and probably was a patron of scribes, as was Nidaba/Nisaba (Micha-lowski 2002). " http://www.academia.edu/2360254/Temple_Sacred_Prostitution_in_Ancient_Mesopotamia_Revisited

That the hieroglyph of pot/vase overflowing with water is a recurring theme can be seen from other cylinder seals, including Ibni-Sharrum cylinder seal. Such an imagery also occurs on a fragment of a stele, showing part of a lion and vases.

| |

![]()

![]() khaṇṭi ‘buffalo bull’ (Tamil) Rebus: khãḍ '(metal) tools, pots and pans' (Gujarati)

khaṇṭi ‘buffalo bull’ (Tamil) Rebus: khãḍ '(metal) tools, pots and pans' (Gujarati)