Title | Dasavatara shrine | Museum Name | National Museum, New Delhi | Gallery Name | Decorative Arts | Object Type | Decorative Art | Main Material | Ivory | Component Material II | Wood | Manufacturing Technique | Carved and painted | Country | India | Origin Place | South India | Period / Year of Work | Late 18th century CE | Dimensions | Lt. 22; Wd. 17.8; Ht. 15 cms |

A magnificent example of ivory carving and painting pursuing typical South Indian idiom, this tiny shrine, full of luster and most rare, both as the art material and the quality of art, installs Lord Vishnu's ten incarnations, each on a circular double lotus seat. For properly accommodating all images the artist has manipulated the sanctum's space into four steps, the foremost accommodating four images : Rama, Balarama, Krishna and Kalki, next, three : Narsimha, man-lion incarnation, Vamana, dwarf incarnation, and Parasurama, further next, two : Kurma, tortoise incarnation and Varaha, boar incarnation, and the last, just one, Matsya, fish incarnation. This arrangement affords to them proper height perspective and full visibility. The sandal wood base of the shrine is mounted with an ivory sheet and in the background is a perforated ivory screen divided into three parts using European style pillars. Such ivory

Images as has this shrine were the specialty of ivory carvers of Trivandrum, Kerala, while screen, especially its painted form, that of Mysore artists. Maybe, the artefact is an assimilation of both. The four-armed Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, and Narsimha hold in two of them sankha - conch, and chakra - disc, while the other two are held in abhaya - the gesture of granting freedom from fear, and varada - the gesture of accomplishment. Kalki is also four-armed, though while in two of them he carries the same conch and disc in other two he is carrying sword and shield. Of other four incarnations Vamana holds an umbrella and 'kamandala' - water-pot with handle, Rama, bow and arrow, Balarama, mace and one hand held in abhaya, and Krishna, stick/ flute and conch. Except Vamana who is even without a crown figures of all them have been richly adorned. In iconography, anatomical proportions and aesthetic quality every image is outstanding.

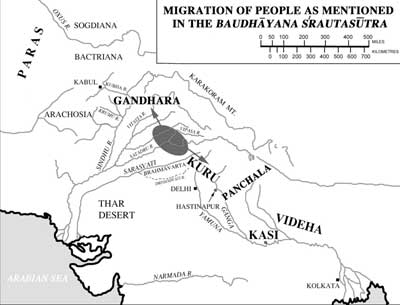

Annex: Indian sprachbund metalwork and related hieroglyph glosses

Hieroglyph:Lotus: Ta. tāmarai lotus, Nelumbium speciosum; tammi lotus. Ma. tāmara id. Ka. tāmare, tāvare id. Koḍ. ta·vare id. Tu. tāmarè lotus flower, Nymphaea pubescens. Te. tāmara, tammi lotus. Pa. tāmarid. Go. (Ko.) tāmar sp. lotus; ? (SR.) dāmerā flower (Voc. 1705). Kuwi (Su.) tāmel bonḍa lotus bud; (S.) tamberi lotus. / Cf. Skt. tāmarasa- id.(DEDR 3163)

Rebus: Copper: Tamba loha: Tamba (nt.) [Sk. tāmra, orig. adj.=dark coloured, leaden; cp. Sk. adj. taŋsra id., to tama] copper ("the dark metal"); usually in combinations, signifying colour of or made of (cp. loha bronze), e. g. lākhātamba (adj.) Th 2, 440 (colour of an ox); ˚akkhin Vv 323 (timira˚) Sdhp 286; ˚nakhin J vi.290; ˚nettā (f.) ibid.; ˚bhājana DhA i.395; ˚mattika DhA iv.106; ˚vammika DhA iii.208; ˚loha PvA 95 (=loha).; Vilīna (adj.) [vi+līna, pp. of vilīyati] 1. clinging, sticking [cp. līyati 1] Vin i.209 (olīna˚ sticking all over). <-> 2. matured ("digested"? cp. vilaya) J iv.72 (nava˚gosappi freshly matured ghee); Miln 301 (phalāni ripefruit). -- 3. [cp. līyati 2] molten, i. e. refined, purified J iv.118 (tamba -- loha˚ molten or liquid -- hot copper); v. 269 (tamba -- loha˚, id.; cp. C. on p. 274; vilīnaŋ tambālohaŋ viya pakkaṭṭhitaŋ lohitaŋ pāyenti); DhsA 14 (˚suvaṇṇa).

*tāmraghaṭa ʻ copper pot ʼ. [tāmrá -- , ghaṭa -- 1]Bi. tamheṛī ʻ round copper vessel ʼ; -- tamheṛā ʻ brassfounder ʼ der. *tamheṛ ʻ copper pot ʼ or < next?*tāmraghaṭaka ʻ copper -- worker ʼ. [tāmrá -- , ghaṭa -- 2]Bi. tamheṛā ʻ brass -- founder ʼ or der. fr. *tamheṛ see prec. (CDIAL 5782, 5783) 5781 tāmrakuṭṭa m. ʻ coppersmith ʼ R. [tāmrá -- , kuṭṭa -- ]N. tamauṭe, tamoṭe ʻ id. ʼ.Garh. ṭamoṭu ʻ coppersmith ʼ; Ko. tāmṭi. (CDIAL 5781) tāmrakāra m. ʻ coppersmith ʼ lex. [tāmrá -- , kāra -- 1]Or. tāmbarā ʻ id. ʼ.(CDIAL 5780) tāmrapaṭṭa m. ʻ copper plate (for inscribing) ʼ Yājñ. [Cf. tāmrapattra -- . -- tāmrá -- , paṭṭa -- 1] M. tã̄boṭī f. ʻ piece of copper of shape and size of a brick ʼ.(CDIAL 5786) tāmrapattra n. ʻ copper plate (for inscribing) ʼ lex. [Cf. tāmrapaṭṭa -- . -- tāmrá -- , páttra -- ] Ku.gng. tamoti ʻ copper plate ʼ.(CDIAL 5787)

tāmrá ʻ dark red, copper -- coloured ʼ VS., n. ʻ copper ʼ Kauś., tāmraka -- n. Yājñ. [Cf. tamrá -- . -- √tam?]Pa. tamba -- ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻ copper ʼ, Pk. taṁba -- adj. and n.; Dm. trāmba -- ʻ red ʼ (in trāmba -- lac̣uk ʻ raspberry ʼ NTS xii 192); Bshk. lām ʻ copper, piece of bad pine -- wood (< ʻ *red wood ʼ?); Phal. tāmba ʻ copper ʼ (→ Sh.koh. tāmbā), K. trām m. (→ Sh.gil. gur. trām m.), S. ṭrāmo m., L. trāmā, (Ju.) tarāmã̄ m., P. tāmbā m., WPah. bhad. ṭḷām n., kiũth. cāmbā, sod. cambo, jaun. tã̄bō, Ku. N. tāmo (pl. ʻ young bamboo shoots ʼ), A. tām, B. tã̄bā, tāmā, Or. tambā, Bi tã̄bā, Mth. tām, tāmā, Bhoj. tāmā, H. tām in cmpds., tã̄bā, tāmā m., G. trã̄bũ, tã̄bũ n.;M. tã̄bẽ n. ʻ copper ʼ, tã̄b f. ʻ rust, redness of sky ʼ; Ko. tāmbe n. ʻ copper ʼ; Si. tam̆ba adj. ʻ reddish ʼ, sb. ʻ copper ʼ, (SigGr) tam, tama. -- Ext. -- ira -- : Pk. taṁbira -- ʻ coppercoloured, red ʼ, L. tāmrā ʻ copper -- coloured (of pigeons) ʼ; -- with -- ḍa -- : S. ṭrāmiṛo m. ʻ a kind of cooking pot ʼ, ṭrāmiṛī ʻ sunburnt, red with anger ʼ, f. ʻ copper pot ʼ; Bhoj. tāmrā ʻ copper vessel ʼ; H. tã̄bṛā, tāmṛā ʻ coppercoloured, dark red ʼ, m. ʻ stone resembling a ruby ʼ; G. tã̄baṛ n., trã̄bṛī, tã̄bṛīf. ʻ copper pot ʼ; OM. tāṁbaḍā ʻ red ʼ. -- X trápu -- q.v. tāmrá -- [< IE. *tomró -- T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 65] S.kcch. trāmo, tām(b)o m. ʻ copper ʼ, trāmbhyo m. ʻ an old copper coin ʼ; WPah.kc. cambo m. ʻ copper ʼ, J. cāmbā m., kṭg. (kc.) tambɔ m. (← P. or H. Him.I 89), Garh. tāmu, tã̄bu.(CDIAL 5779)

paṭṭa 7699 paṭṭa1 m. ʻ slab, tablet ʼ MBh., °ṭaka -- m., °ṭikā -- f. Kathās. [Derivation as MIA. form of páttra -- (EWA ii 192), though very doubtful, does receive support from Dard. *paṭṭa -- ʻ leaf ʼ and meaning ʻ metal plate ʼ of several NIA. forms of páttra -- ]Pa. paṭṭa -- m. ʻ slab, tablet ʼ; Pk. paṭṭa -- , °ṭaya -- m., °ṭiyā<-> f. ʻ slab of stone, board ʼ; NiDoc. paṭami loc. sg., paṭi ʻ tablet ʼ; K. paṭa m. ʻ slab, tablet, metal plate ʼ, poṭu m. ʻ flat board, leaf of door, etc. ʼ,püṭü f. ʻ plank ʼ, paṭürü f. ʻ plank over a watercourse ʼ (< -- aḍikā -- ); S. paṭo m. ʻ strip of paper ʼ, °ṭi f. ʻ boat's landing plank ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ board to write on, rafter ʼ; L. paṭṭ m. ʻ thigh ʼ, f. ʻ beam ʼ, paṭṭā m. ʻ lease ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ narrow strip of level ground ʼ; P. paṭṭ m. ʻ sandy plain ʼ, °ṭā m. ʻ board, title deed to land ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ writing board ʼ; WPah.bhal. paṭṭ m. ʻ thigh ʼ, °ṭo m. ʻ central beam of house ʼ; Ku. pāṭo ʻ millstone ʼ, °ṭī ʻ board, writing board ʼ; N. pāṭo ʻ strip, plot of land, side ʼ, °ṭi ʻ tablet, slate, inn ʼ; A. pāṭ ʻ board ʼ, paṭā ʻ stone slab for grinding on ʼ; B. pāṭ, °ṭā ʻ board, bench, stool, throne ʼ, °ṭi ʻ anything flat, rafter ʼ; Or. pāṭa ʻ plain, throne ʼ, °ṭi, paṭā ʻ wooden plank, metal plate ʼ; Bi. pāṭ ʻ wedge fixing beam to body of plough, washing board ʼ, °ṭī ʻ side -- piece of bed, stone to grind spices on ʼ, (Gaya) paṭṭāʻ wedge ʼ; Mth. pāṭ ʻ end of handle of mattock projecting beyond blade ʼ, °ṭā ʻ wedge for beam of plough ʼ; OAw. pāṭa m. ʻ plank, seat ʼ; H. pāṭ, °ṭā m. ʻ slab, plank ʼ, °ṭī ʻ side -- piece of bed ʼ, paṭṭā m. ʻ board on which to sit while eating ʼ; OMarw. pāṭī f. ʻ plank ʼ; OG. pāṭīuṁ n. ʻ plank ʼ, pāṭalaü m. ʻ dining stool ʼ; G. pāṭ f., pāṭlɔ m. ʻ bench ʼ, pāṭɔ m. ʻ grinding stone ʼ, °ṭiyũ n. ʻ plank ʼ, °ṭṛɔ m., °ṭṛī f. ʻ beam ʼ; M. pāṭ m. ʻ bench ʼ, °ṭā m. ʻ grinding stone, tableland ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ writing board ʼ; Si. paṭa ʻ metal plate, slab ʼ. -- Deriv.: N. paṭāunu ʻ to spread out ʼ; H. pāṭnā ʻ to roof ʼ.WPah.kṭg. pāṭ m. ʻ mill -- stone ʼ (poss. Wkc. pāṭ m. ʻ female genitals ʼ, paṭṭɔ m. ʻ buttocks, back ʼ; bhal. paṭṭ m. ʻ thigh ʼ Him.I 110); kṭg. paṭḷɔ m. ʻ small wooden stool ʼ.

72 Ta. aṭi foot, footprint, base, bottom, source, origin; aṭimai slavery, servitude, slave, servant, devotee; aṭitti, aṭicci maidservant; aṭiyavaṉ, aṭiyāṉ, aṭiyōṉ slave, devotee. Ma. aṭi sole of foot, footstep, measure of foot, bottom, base; aṭima slavery, slave, feudal dependency; aṭiyān slave, servant; fem. aṭiyātti. Ko. aṛy foot (measure); ac place below; acgaṛ place beneath an object, position after the first in a row; ac mog younger son. To. oṛy foot. Ka. aḍi foot, measure of foot, step, pace, base, bottom, under; aḍime slavery; aḍiya slave. Koḍ. aḍi place below, down. Tu. aḍi bottom, base; kār aḍi footsole, footstep; aḍi kai palm of the hand. Te. aḍugu foot, footstep, footprint, step, pace, measure of a foot, bottom, basis; aḍime slavery, slave, bondman; aḍiyãḍu slave, servant; aḍi-gaṟṟa sandal, wooden shoe.Ga. (S.2) aḍugu footstep (< Te.). Go. (G.) aḍi beneath; (Mu.) aḍit below; aḍita lower; aṛke below; (Ma.) aḍita, aḍna lower; (M.) aḍ(ḍ)i below, low; (L.) aḍī down; (Ko.) aṛgi underneath; aṛgita lower (Voc. 33). Konḍa aḍgi below, underneath; aḍgiR(i) that which is underneath; aḍgiRaṇḍ from below, from the bottom.

86 Ta. aṭai prop. slight support; aṭai-kal anvil. Ma. aṭa-kkallu anvil of goldsmiths. Ko. aṛ gal small anvil. Ka. aḍe, aḍa, aḍi the piece of wood on which the five artisans put the article which they happen to operate upon, a support; aḍegal, aḍagallu, aḍigallu anvil. Tu. aṭṭè a support, stand. Te. ḍā-kali, ḍā-kallu, dā-kali, dā-gali, dāyi anvil.

3843 Ta. paṭam instep. Ma. paṭam flat part of the hand or foot. Pe. paṭa key palm of hand. Manḍ. paṭa kiy id.; paṭa kāl sole of foot. Kuwi. (Su.) paṭa naki palm of hand.

3878 Ta. paṭṭai flatness; paṭṭam flat or level surface of anything, flat piece (as of bamboo). Ko. paṭ flatness (of piece of iron, of head); paṭm (obl. paṭt-) ground for house. To. poṭ site of dairy or house. ?Koḍ. paṭṭi space before house, spreading space; maṇa-paṭṭi sandbank. Nk. paṛ place. Pa. paḍ place, site. Pe. paṭ kapṛa top of the head. Manḍ. paṭ kapṛa id. Malt. paṭa numeral classifier of flat objects. Cf. 3843 Ta. paṭam.

3865 Ta. paṭṭaṭai, paṭṭaṟai anvil, smithy, forge. Ka. paṭṭaḍe, paṭṭaḍi anvil, workshop. Te. paṭṭika, paṭṭeḍa anvil; paṭṭaḍa workshop. 3875 Ta. paṭṭai palmyra timber, rafter; paṭṭiyal lath, reeper. Ma. paṭṭa areca bough. Ka. paṭṭe palmyra timber, rafter, areca bough; paṭṭi piece of timber of door-frame, rafter, joist; paṭṭika board. Tu. paṭirafter. Te. paṭṭe bar or spar of wood, piece of timber of door-frame; paṭṭi plank; paṭṭika plank, board, bar of wood. Kol. paṭṭe plank. Nk. paṭi id. Pa. peṭṭi (pl. peṭkul) beam, post. Ga. (P.) paṭiya beam. Kuipaṭi beam; paṭa board. Kur. paṭṭā beam in oilmill.

పట్టిక (p. 0700) [ paṭṭika ] paṭṭika. [Skt.] n. A plate of metal, a board, a frame, the pieces of wood across a door. ఫలకము, పలక, చట్టము, రేకు, గందపట్టె. An anvil, కమ్మరివాని దాగలి. "లలాటపట్టికలబెట్టిన పట్టెవర్థనంబులు." Suca. ii. 19. పట్టికామంచము Same as పట్టెమంచము. పట్టె (p. 0703) [ paṭṭe ] or పట్టియ paṭṭe. [Tel.] n. A spar of wood. పలక. A piece of wood that forms the frame of a cot.

Palagaṇḍa [cp. Sk. palagaṇḍa Halāyudha ii.436; BSk. palagaṇḍa AvŚ i.339; Aṣṭas. Pār. 231; Avad. Kalp. ii.113] a mason, bricklayer, plasterer M i.119; S iii.154 (the reading phala˚ is authentic, see Geiger,P.G. § 40); A iv.127. Phalaka [fr. phal=*sphal or *sphaṭ (see phalati), lit. that which is split or cut off (cp. in same meaning "slab"); cp. Sk. sphaṭika rock -- crystal; on Prk. forms see Pischel, Prk. Gr. §206. Ved. phalaka board, phāla ploughshare; Gr. a)/spalon, spola/s, yali/s scissors; Lat. pellis & spolium; Ohg. spaltan=split, Goth, spilda writing board, tablet; Oicel. spjald board] 1. a flat piece of wood, a slab, board, plank J i.451 (a writing board, school slate); v.155 (akkhassa ph. axle board); vi.281 (dice -- board). pidhāna˚ covering board VbhA 244= Vism 261; sopāna˚ staircase, landing J i.330 (maṇi˚); Vism 313; cp. MVastu i.249;˚āsana a bench J i.199; ˚kāya a great mass of planks J ii.91. ˚atthara -- sayana a bed covered with a board (instead of a mattress) J i.304, 317; ii.68. ˚seyya id. D i.167 ("plank -- bed"). -- 2. a shield J iii.237, 271; Miln 355; DhA ii.2. <-> 3. a slip of wood or bark, used for making an ascetic's dress (˚cīra) D i.167, cp. Vin i.305. ditto for a weight to hang on the robe Vin ii.136. -- 4. a post M iii.95 (aggaḷa˚ doorpost); ThA 70 (Ap. v.17).பலகை palakai

, n. < phalaka. [K. halage] 1. Board, plank; மரப்பலகை. பொற்பலகை யேறி யினிதமர்ந்து (திருவாச. 16, 1). 2. Levelling plank; உழவிற் சமன்படுத்தும் மரம். 3. Gaming table; சூதாட உதவுவதும் கோடுகள் வரையப் பட்டதுமான பலகை. பலகை செம்பொனாக (சீவக. 927). 4. Long shield, buckler; நெடும்பரிசை. (தொல். பொ. 67, உரை, பி-ம், பக். 209). 5. A drum; பறைவகை. வீணை பலகைதித்தி வேணுசுரம் (விறலிவிடு.). 6. Seat on an elephant's back, howdah; யானைமேற்றவிசு. (பிங்.) 7. Tablet, slate; எழுதுபலகை.

khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन्, which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b,l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-bastakhāra-basta खार-बस््त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith. -büṭhü -ब&above;ठू&below; । लोहकारभित्तिः f. the wall of a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -bāy -बाय् । लोहकारपत्नी f. a blacksmith's wife (Gr.Gr. 34). -dŏkuru -द्वकुरु&below; । लोहकारायोघनः m. a blacksmith's hammer, a sledge-hammer. -gȧji -ग&above;जि&below; or -güjü -ग&above;जू&below; । लोहकारचुल्लिः f. a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -hāl -हाल् । लोहकारकन्दुः f. (sg. dat. -höjü -हा&above;जू&below;), a blacksmith's smelting furnace; cf. hāl 5. -kūrü -कूरू&below; । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter. -koṭu -क&above;टु&below; । लोहकारपुत्रः m. the son of a blacksmith, esp. a skilful son, who can work at the same profession. -küṭü -क&above;टू&below; । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter, esp. one who has the virtues and qualities properly belonging to her father's profession or caste. -më˘ʦü 1 -म्य&above;च&dotbelow;ू&below; । लोहकारमृत्तिका f. (for 2, see [khāra 3] ), 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore. -nĕcyuwu -न्यचिवु&below; । लोहकारात्मजः m. a blacksmith's son. -nay -नय् । लोहकारनालिका f. (for khāranay 2, see [khārun] ), the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting. -ʦañĕ -च्&dotbelow;ञ । लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wān वान् ।लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 3). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil. (Kashmiri)

S. KalyanaramanSarasvati Research CenterJune 28, 2015 |

|

![The sculptures of Rama and Lakshmana; (right) the Dhanwantri Vishnu discovered at Gandha Madana hill at Hampi.— Photos: T.M. Keshav The sculptures of Rama and Lakshmana; (right) the Dhanwantri Vishnu discovered at Gandha Madana hill at Hampi.— Photos: T.M. Keshav]() The sculptures of Rama and Lakshmana; (right) the Dhanwantri Vishnu discovered at Gandha Madana hill at Hampi.— Photos: T.M. Keshav

The sculptures of Rama and Lakshmana; (right) the Dhanwantri Vishnu discovered at Gandha Madana hill at Hampi.— Photos: T.M. Keshav![]()

Indian Diplomacy

Indian Diplomacy

Sri Sri Ravi Shankar

Sri Sri Ravi Shankar

Ancient graveyard, near Nakhtarna, Kutch: anthropomorphic menhirs

Ancient graveyard, near Nakhtarna, Kutch: anthropomorphic menhirs

Ukherda burial ground, cemetery.

Ukherda burial ground, cemetery.

![[@]](http://www.paolaraffetta.com.ar/Images/at.gif) optusnet.com.au

optusnet.com.au

kalyan97

kalyan97

Narendra Modi

Narendra Modi

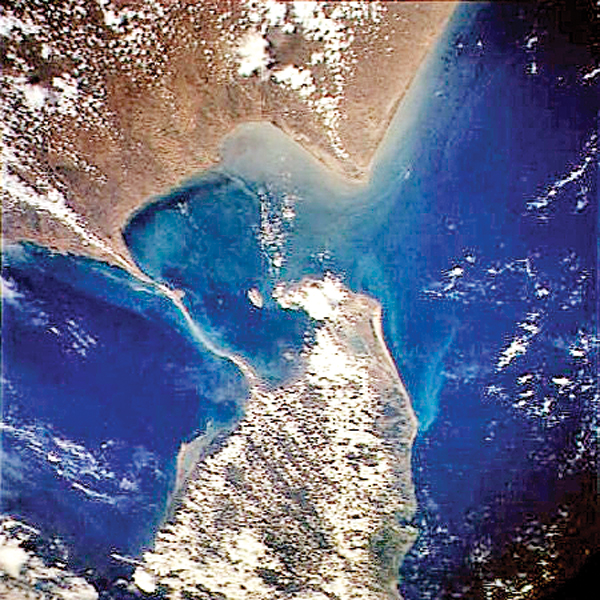

Aerial view of Rama Setu shoals

Aerial view of Rama Setu shoals

Tree on railing. Capital of pillar. Besnagar. This is: kuṭhi-dhvaja, signifying 'smelter'.

Tree on railing. Capital of pillar. Besnagar. This is: kuṭhi-dhvaja, signifying 'smelter'.

indianhistorypics

indianhistorypics

How drones changed the face of journalism