Yoga for Personal & Social Development in Greece

Lecture

by

Prof. Bharat Gupt

SHANTOM CENTRE, Athens, June 6, 2015

Lida Shantala, director of Shantom, introduced Prof Bharat Gupt as a friend of the Centre, a classicist, lover of Greece, expert in ancient Greek and Indian theater, and a scholar of Indian philosophy and religion. As Prof. Gupt spoke in English, translation was provided by Ms. Irene Maradei. Lida also thanked the Indian Embassy for its participation.

Beginning his talk, Prof Gupt said that he was extremely delighted at having this chance to speak at a Centre established in the memory of Smaro Stefanidou, a famous Greek film and theatre actress and Lida Shantala’s mother. He said, that speaking on Yoga at an artisitic Centre, rather than a religious venue, was more valuable, as art is usually more creative and all-embracing, whereas religio-centricity sometimes declines into conservatism. This Centre celebrates the lifelong dedication to art by Smaro Stefanidou and Lida Shantala, and is thus, a place of special significance. Yoga, he said, is also an art. In ancient times, in both Greece and India, there was no dividing line between humanities and sciences, and both were categor-ised as episteme or vidyaa.

He started with recitation in Sanskrit of an invocation by the ancient Indian poet Bhartrihari,

Dikkaalaadiyanavacchinnaanantachinmaatramuurtaye/

Svaanubhuutimekamaanaaya namah shaantaaya tejse.

“I bow to Shiva, to ultimate peace and dynamism, boundless, not limited by time or space; to the Image of pure Consciousness, experienced and known by oneself alone.”

Prof. Gupt expounded that in the Indian traditional systems (and this was true of Socrates in Greece as well), knowledge is validated by self-experience only; not through a scripture, a teacher or a prophet's words or any material inference. Actually, knowing Truth through physical, mental and higher conscious-ness, is YOGA. The asanasand pranaayama are the physical level, the channeling of the mind is the psychic level, and the knowing the Ultimate through consciousness is the final level as mentioned in the verse just recited.

If one is to look for a definition of Yoga, the best is to be found in Patanjali,

Yogah chittavrittih nirodhah.”

This is not to be translated as “Yoga is control of mind”, as is often done. Yoga is an unfolding or experience of the true nature of Consciousness. It is through Consciousness that one becomes aware of the body and the mind. TrueYoga, therefore, is channelling of the physical, of the mental and of consciousness, to its final destination. Yoga is certainlynot asanas or postures only. The purpose of Yoga is not to have merely an attractive and healthy body. If that were so, Yoga would be no different from swimming or eurythmics. We have to see the totality of Yoga at all the levels.

Yoga is also not to be seen as a method of control which means doing certain things and stopping with it. It does not mean doing this and not doing something else. Yoga is actually channeling of your total self towards a journey. It is a journey to good physical health, mental health and stability and to opening up of the consciousness to the total Cosmos. Yoga, therefore, is just about everything.

Hence in the famous text the Bhagavadgita, it is said, that Yoga is doing all our activities with the highest skill. “Yogah karmasu kaushalam.” Yoga is doing the best in every human sphere of action.

A Yoga follower is not an ascetic, nor a recluse, nor is she or he, exclusively devoted to spiritual concerns. One is most thorough in doing all things with highest efficiency. It is living life in all its completeness, with all its travails, troubles and challenges. That is the reason why Yoga is not merely a theology. There are many controversies at present regarding Yoga. It is often asked if Yoga is merely a Hindu pursuit. Can Christians or Muslims practice it? Would they cease to be Muslims or Christians if they do so? There are theological wars going on around this question. But if you experience Yoga as I explained it to be, there cannot be any controversy. Every human being has a body, a mind and a consciousness which he transcends if he wishes to go beyond the conventional and wants to experience the Cosmos. Yoga is an exploration and an experience and not a set of doctrines.

This brings me to central question of this lecture. Can Yoga be used for combating the hard times that Greece is going through now? If you see the vastness of Yoga, you will realise that it becomes an instrument for facing all the problems and trepidations that we face in our lives. Yoga then is for those who are in difficulties and for nations in difficult periods.

How should then pursue Yoga? Should it done with a limited aim? It cannot be done with a single aim. Yoga offers to solve all the problems of life. It does provide you a healthy body, a mind which can face the challenges of daily living, and above all Yoga makes you aware that there is a reality beyond body and mind.

Some theologies are disturbed by Yoga for a simple reason. Every theology that does not accept the totality of existence but insists that “my God alone is true,” or that “my prophet alone is the messenger of God”, or that by following a particular Saviour alone one shall not walk in darkness any more, feels threatened by the exploratory nature of Yoga. It is not for theological differences that Yoga is threatening to such doctrines. It is so, because Yoga expands the heart and the mind and is all inclusive. It reveals through self experience and personal testimony and not through stated dogmas regarding the truth of religious experience. It makes you decide yourself about the diversities and differences in the Universe and how to deal with them by self experience and not by doctrinal submission to the 'revealed' words of others.

Yoga is the best practical way of living through hard times. However, the ground needs to be prepared before starting the practice of Yoga. In the classical systems of Indian thought this preparation was called as submitting to Yama and Niyama. That is, to create and sustain certain attitudes and practices. Briefly speaking, it is pursuing a life of hard work, not desiring the wealth of others, maintaining a life of discipline though not of asceticism. For a serious and determined person on the path of Yoga, being an ascetic is not a requirement. Countless sages and yogis in India have set the example of being stationed in their worldly lives and duties while being at a high level of yogic knowledge.

Yoga, therefore requires, some kind of a restraint and refraining from aggression. It should not be very difficult for this audience to understand these are the same as the preconditions for artistic activity. If an artist is hateful or destructive, or angry and unforgiving, he or she cannot create great art. The same is true for Yoga.

So where do we begin? There are many prescriptions, but more than them, it is your own search which is going to tell you where and how to start. The needed frame of mind for Yoga is non aggression, tremendous patience and then a regimen of the asanas and various exercises. These have to be done under proper guidance. The next stage is control of breath or pranaayama. After a habit of doing these with ease has been developed and fresh energies are seen as manifesting in the body, one starts going inward. Inwardness is an essential activity for any creative person. Again the artists are the best paradigm for a budding yogi.

Yoga is the beginning of a new art, the art of going within. This is the start of serious Yoga. Very few of us are capable of doing this, just as very few of us are capable of becoming good artists. But even coming close to this condition, helps you attain a good vision of the world, a harmonious way of living with other persons. That is not a small thing. And so, even the mundane results of yoga are spectacular.

I shall describe what is said to be inward life. It is said that it is essentially a union of the individual self with the whole Cosmos. It is thus that a true knowledge of the permanent reality comes to you.

The very word yoga means uniting. But we think of Yoga as a cult of exercises. I hope I have succeeded in bringing to your attention the totality of the Yoga pursuit.

Efcharisto para poli.

And now the questions.

Q: (by a Greek poet.). I am very moved and happy to be here. I ask your advice rather than a question. Yoga has a country, it sprang from a certain tradition. I am aware of the fact that it is not limited to it. But please tell me, for someone who wants to delve more seriously, more in depth into yoga and serve it better, is it advisable or necessary to delve into Eastern philosophy and Hindu religion?

BG: Studying Hinduism will bring its own reward. But even after studying it, there is little chance that one understands Yoga. Nothing shall mean much unless one does some practical Yoga. I can say from my own experience, as I have done music as Yoga (called naadopaasanaa in India). It was only after doing something practical like music that I could understand the meaning of the deep philosophical texts of Hinduism. As any musician knows, music makes you aware of your body as you employ it to create art, and so your mind, and an entire differently way of understanding develops by constant practice. Same is true of Yoga.

Question: What you explained about Yoga seems to be very similar to Zen or Buddhist thought. What do you think?

BG: Well, in my humble opinion there is extremely little difference between what have been academically called as separate doctrines going by the name of Hinduism and Buddhism. There have been political reasons for projecting a big divide between the two but to discuss them is beyond the subject of this talk today.

Question: What is Yoga for Indians, I mean the common persons? For those who do not study or discuss the way we have been talking here? What place does Yoga have in a regular Indian’s everyday life?

BG: Yoga is a very wide term used terms for many kinds of practices. Asanasand pranayama is one part of it though they stand for Yoga in the common mind now. But if Yoga is to be seen as way or journey to knowing the Cosmic Self-experience, then there have to many ways of approaching the Cosmic Truth. So there are dozens of Yogas: Selfless service, social responsibility, lifelong devotion to the pursuit of an art or a science, or even a political responsibility

{laughter}.

Question: What did you say? Politics?

BG: It is surprising to hear this. However, if you take political responsibility in the spirit of total selflessness and with no personal interest whatsoever, it is a legitimate Yoga. Arjun was preached to do that by Krishna, to establish a just kingdom for common Good. Politics can thus be beautiful.

{Laughter and disbelief}.

Question: Do you know of any such politicians?

BG: Yes, many! I have lived in Delhi all my life where all kinds of politicians live, from black to white. If I recall correctly, Plato has said that of all arts, statecraft is the highest art. You make a state for others, not just for yourself to be a tyrant.

Question: You spoke of regular Yoga practice. What does “regular” mean? How often and for how long does Yoga need to be done?

BG The physical part of it is always a regimen but the inner journey is known only to the practitioner. Classical texts use a term called pranidhaana or concentrative determination for progressing in a Yoga journey. Higher and stronger the pranidhaana, better the result.

Question: Sometimes I try very hard to go ahead in my Yoga pursuit but then sometimes I catch myself getting angry or upset - I get very disappointed for not being able to control myself more, following the yamas and niyamas. What should I do?

BG: We are all like that. That is why we need Yoga.

Question: (The poet) Are Yoga and meditation part of life or are they separate or is there a sacred union?

BG: In whatever form or style, Yoga has to be part of daily life.

Question: (by Lida). I like the way you have explained the channelling of energies in Yoga or rather that which is called 'control' in terms of Yoga. It is good that you explained that Yoga is not following a dogma or merely a set of rules but that it requires unconventional thinking and the opening of the mind.

BG: If you would read the lives of great Yogis, you will find that nearly all of them were unconventional and had their own innovative systems and even their rather eccentric style of social behaviour. The very core of Yoga is to think beyond the conventional and to know things afresh. That is why all puritans feel threatened by Yoga, specially by Yoginis, as they break rules.

Q Regarding your expounding of Yoga as channelling of the forces and going within, I would like to say that in the Greek tradition there is a term used for inward exploration called 'endoscopia.'

BG For my info can you tell me in which text is this mentioned?

The Poet: One hundred maxims from the sayings of the Oracle of Delphi.

Q Was Gandhi a Yogi?

BG: I will like to take that up in a separate lecture on Gandhi. I have a very critical view of Gandhi. In my humble opinion, right or wrong, like most social and political thinkers of modern India, Gandhi was cut off from the essential thought of classical India. Gandhi's ideas were rooted in the paradigma of the medieval Hindu devotional movement called Vaishnavism that dominated the medieval times. The difference is the same as between a Byzantine painting of Christ in a monastery and an ancient painting of Apollon on a ritual ceramic vase. I am giving a comparison from Greece for your easy understanding. Gandhi did not belong to ancient Indian thought. My view, many may disagree.

Prof. Vassiliades: I want to say, although influenced by Islam and Christianity, Gandhi revered and constantly read the Bhagavadgita, thus he does havesome connection with ancient Indian thought.

BG: That is why he made a mess of the Bhagavadgita. That is why he told the Jews to surrender to Hitler. We have to reassess Gandhi, Nehru and many of the so called makers of modern India. I have been saying this for 40 years. Most of these modern Indian leaders have been unaware of the real classical Indian thought. Look how Gandhi treated sex, which had little to do even with medieval India. Gandhi, regarding his attitude to sex and women reminds me of some Christian monk of the early centuries AD, who castrated himself. Don't mind, mine is, perhaps, a very politically incorrect view.

Prof.Vasillidaes: Classical India is not just Tantrism. It is also Jain thought which was a big influence on Gandhi.

BG. I agree with you, that there is more to ancient Indian philosophy than just Tantra and the influence of Jain thought on Gandhi was certainly present. However, look at the real spirit of those ideas of brahmcharya (sexual control) and ahimsa (non-violence), which Gandhi adopted from Jain thought. In ancient times, as shown in the texts, brahmacharya was supposed to be practiced as moderation by the householder and total abstinence was for the mendicant ascetic. It was different for different people, in ancient society. Brahmacharya was not abstinence for the householder in ancient thought which rested on the four stages of life and social responsibility. But Gandhi forced abstinence on himself and preached it as desirable for all. Non violence or ahimsa was never pushed to such extreme in classical times, as Gandhi pushed it. All the Jain and Buddhist kings of India had strong and well equipped armies.

There is a lot of confusion about ancient Indian texts as for the past six to seven hundred years there have been no universities where these texts could have been studied systematically. Now there is a fresh need to understand them, prescribe them, study them at all levels of education, and discuss them again widely. Then alone we will be able to judge our modern political leaders.

I thank you all, for coming and listening to me and giving your time this evening. Thank you very much indeed.

END

Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj and PM

Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj and PM

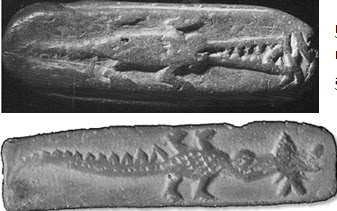

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Tied: dhama ‘cord’ rebus: dhamma ‘dharma, virtuous conduct’ sangin ‘mollusc’ rebus: sangha ‘community’. Thus, dhamma guild has been identified by the hieroglyph multiplex.

Tied: dhama ‘cord’ rebus: dhamma ‘dharma, virtuous conduct’ sangin ‘mollusc’ rebus: sangha ‘community’. Thus, dhamma guild has been identified by the hieroglyph multiplex.

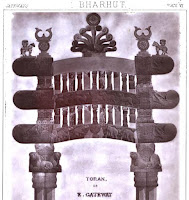

Bharhut molluscs centre-piece on tōraṇa

Bharhut molluscs centre-piece on tōraṇa  Sanchi tōraṇa molluscs centre-piece on hieroglyph multiplexes flanking ibbo vaThAra, merchant quarter'

Sanchi tōraṇa molluscs centre-piece on hieroglyph multiplexes flanking ibbo vaThAra, merchant quarter'

.jpg)

![[Sahitya Akademi_dream_of_queen_maya.jpg]](http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_zfDuy4-yDB8/S3D0eHNWs2I/AAAAAAAAE4w/LeapHKHr18c/s640/Sahitya+Akademi_dream_of_queen_maya.jpg)

Hoof of an equus genus (one toe per foot protected by a strong hoof).

Hoof of an equus genus (one toe per foot protected by a strong hoof). The rear foot of a giraffe.

The rear foot of a giraffe. kiang

kiang

A Persian onager (Equus hemionus onager) at Rostov-on-Don Zoo, Russia.

A Persian onager (Equus hemionus onager) at Rostov-on-Don Zoo, Russia.

Indian onager

Indian onager