https://tinyurl.com/y4wwtp96

The petroglyphs of Ratnagiri, Rajapur areas of Konkan are created on laterite rocks.

There are indications that these petroglyphs may be precursors of the Indus Script writing system. A number of domesticated and wild animals seen on such petroglyphs are part of the iconographic repertoire in the phonetics, semantics and pragmatics of Meluhha, Indian sprachbund ‘language union’.

The Meluhha word for laterite as a wealth-accounting category is: goṭa.

The hieroglyph is goṭa 'a round pebble, or blob'. 24 dots on a seal.

Meluhha rebus readings are: goṭa, goṭā 'laterite, ferrite ore'. खोट [khōṭa] ‘ingot, wedge’; A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down)(Marathi) khoṭ f ʻalloy' (Lahnda); goṭī 'lump of silver' (Gujarati); goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ(Kashmiri).

The first Indian coins of Apollodotus used Indian symbols. These coins associated the elephant with the Buddhist Chaitya or arched-hill symbol, sun symbols, six-armed symbol, and a river. The bull had a Nandipada in front. The symbol at the top of the bull is only a mint mark. These symbols disappeared soon after, and only the elephant and the bull remained.

Indus Script Hypertexts on Apollodotus coin (ca.2nd-1st cent. BCE)

The legends in Greek and Kharoṣṭhī read:

Greeklegend ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΠΟΛΛΟΔΟΤΟΥ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ, "of Saviour King Apollodotus".

Rev: Zebu bull with Kharoshti legend 𐨨𐨱𐨪𐨗𐨯 𐨀𐨤𐨫𐨡𐨟𐨯 𐨟𐨿𐨪𐨟𐨪𐨯 (MAHARAJASA APALADATASA TRATARASA),"Saviour King Apollodotus".

Rev: Zebu bull with Kharoshti legend 𐨨𐨱𐨪𐨗𐨯 𐨀𐨤𐨫𐨡𐨟𐨯 𐨟𐨿𐨪𐨟𐨪𐨯 (MAHARAJASA APALADATASA TRATARASA),"Saviour King Apollodotus".

The Indus Script Hypertexts in addition to the Greek and Kharoṣṭhī legends are:

1. Nandipada in front of 2. zebu, bos indicus, 3. arched-hill, 4. sun, 5 six-armed vajra, 6. elephant; and 7. a river.

These five Indus Script Hypertexts are read rebus (or, rūpaka, metaphors in Meluhha).

1. Nandipada. dul ayo kammaṭa 'alloy metal casting mint' PLUS dala 'leaf petal' rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot PLUS karã̄ n.' pl.wristlets, bangles' Rebus: khār 'blacksmith, iron worker'. The 'bangle' image may have a variant reading as a 'pebble, round stone' goṭā 'round pebble, stone' Rebus: goṭā ''laterite, ferrite ore''gold braid' खोट [khōṭa] ‘ingot, wedge’; A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down)(Marathi) khoṭ f ʻalloy' (Lahnda)

2. poḷa 'zebu' rebus: poḷa 'magnetite ore'.

3. ḍāngā = hill, dry upland (B.); ḍã̄g mountain-ridge' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'

4. arka 'sun' rebus; arka, eraka 'gold, copper', eraka 'molten cast'

5. Six-armed vajra: dhā̆vaḍ 'strands' rebus: dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter'. -- and relate the work of a smelter to a dotted circle which is dāya 'throw of one in dice' rebus: dhāi 'mineral ore' PLUS arā 'spokes' rebus: āra 'brass'.PLUS eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'molten cast'

6. karba, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron' ibbo 'merchant'

This is an addendum to:

Itihāsa, Prehistoric art of Ratnagiri, Rajapur areas of Konkan hints at lost Indian civilisation

Prehistoric art hints at lost Indian civilisation

Petroglyphs "Petroglyphs are images created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions of the technique to refer to such images. Petroglyphs are found worldwide, and are often associated with prehistoric peoples. The word comes from the Greek prefix petro-, from πέτρα petra meaning "stone", and γλύφω glýphō meaning "to carve", and was originally coined in French as pétroglyphe....Some petroglyphs might be as old as 40,000 years, and petroglyph sites in Australia are estimated to date back 27,000 years. Many petroglyphs are dated to approximately the Neolithic and late Upper Paleolithic boundary, about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, if not earlier, such as Kamyana Mohyla. Around 7,000 to 9,000 years ago, other precursors of writing systems, such as pictographs and ideograms, began to appear. Petroglyphs were still common though, and some cultures continued using them much longer, even until contact with Western culture was made in the 19th and 20th centuries. Petroglyphs have been found in all parts of the globe except Antarctica, with highest concentrations in parts of Africa, Scandinavia, Siberia, southwestern North America, and Australia."

India

- Bhimbetka rock shelters, Raisen District, Madhya Pradesh, India.

- Kupgal petroglyphs on Dolerite Dyke, near Bellary, Karnataka, India.

- Kudopi, Sindhudurg District, Maharashtra, India.

- Hiwale, Sindhudurg District, Maharashtra, India.

- Barsu, Ratnagiri District, Maharashtra, India.

- Devihasol, Ratnagiri District, Maharashtra, India

- Edakkal Caves, Wayanad District, Kerala, India.

- Perumukkal, Tindivanam District, Tamil Nadu, India.

- Kollur, Villupuram, Tamil Nadu.

- Unakoti near Kailashahar in North Tripura District, Tripura, India.

- Usgalimal rock engravings, Kushavati river banks, in Goa

- Ladakh, NW Indian Himalaya.

Recently petroglyphs were found at Kollur village in Tamil Nadu. A large dolmen with four petroglyphs that portray men with trident and a wheel with spokes has been found at Kollur near Triukoilur 35 km from Villupuram. The discovery was made by K.T. Gandhirajan. This is the second instance when a dolmen with petrographs has been found in Tamil Nadu, India. In October 2018, petroglyphs were discovered in the Ratnagiri and Rajapur areas in the Konkan region of western Maharashtra. Those rock carvings which might date back to 10,000 BC, depict animals like hippopotamuses and rhinoceroses which aren't found in that region of India.

PETROGLYPH PARADISE Read more at: https://punemirror.indiatimes.com/pune/others/history-on-the-rocks/articleshow/47348674.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

The discovery of rock carvings believed to be tens of thousands of years old in India's western state of Maharashtra has greatly excited archaeologists who believe they hold clues to a previously unknown civilisation, BBC Marathi's Mayuresh Konnur reports.The rock carvings - known as petroglyphs - have been discovered in their thousands atop hillocks in the Konkan region of western Maharashtra.Mostly discovered in the Ratnagiri and Rajapur areas, a majority of the images etched on the rocky, flat hilltops remained unnoticed for thousands of years.Most of them were hidden beneath layers of soil and mud. But a few were in the open - these were considered holy and worshipped by locals in some areas. The sheer variety of the rock carvings have stunned experts - animals, birds, human figures and geometrical designs are all depicted.The way the petroglyphs have been drawn, and their similarity to those found in other parts of the world, have led experts to believe that they were created in prehistoric times and are possibly among the oldest ever discovered. "Our first deduction from examining these petroglyphs is that they were created around 10,000BC," the director of the Maharashtra state archaeology department, Tejas Garge, told the BBC.The credit for their discovery goes to a group of explorers led by Sudhir Risbood and Manoj Marathe, who began searching for the images in earnest after observing a few in the area. Many were found in village temples and played a part in local folklore."We walked thousands of kilometres. People started sending photographs to us and we even enlisted schools in our efforts to find them. We made students ask their grandparents and other village elders if they knew about any other engravings. This provided us with a lot of valuable information," Mr Risbood told the BBC.Together they found petroglyphs in and around 52 villages in the area. But only around five villages were aware that the images even existed. Apart from actively searching for them, Mr Risbood and Mr Marathe have also played an important role in documenting the petroglyphs and lobbying authorities to get involved in studying and preserving them.Mr Garge says the images appear to have been created by a hunter-gatherer community which was not familiar with agriculture."We have not found any pictures of farming activities. But the images depict hunted animals and there's detailing of animal forms. So this man knew about animals and sea creatures. That indicates he was dependent on hunting for food." Dr Shrikant Pradhan, a researcher and art historian at Pune's Deccan College who has studied the petroglyphs closely, said that the art was clearly inspired by things observed by people at the time. "Most of the petroglyphs show familiar animals. There are images of sharks and whales as well as amphibians like turtles," Mr Garge adds. But this begs the question of why some of the petroglyphs depict animals like hippos and rhinoceroses which aren't found in this part of India. Did the people who created them migrate to India from Africa? Or were these animals once found in India? The history of India in one exhibition Cooking the world's oldest known curry Early civilisation thrived without river The state Government has set aside a fund of 240 million rupees ($3.2m; £2.5m) to further study 400 of the identified petroglyphs. It is hoped that some of these questions will eventually be answered.

Stunning aerial shots of India's prehistoric art

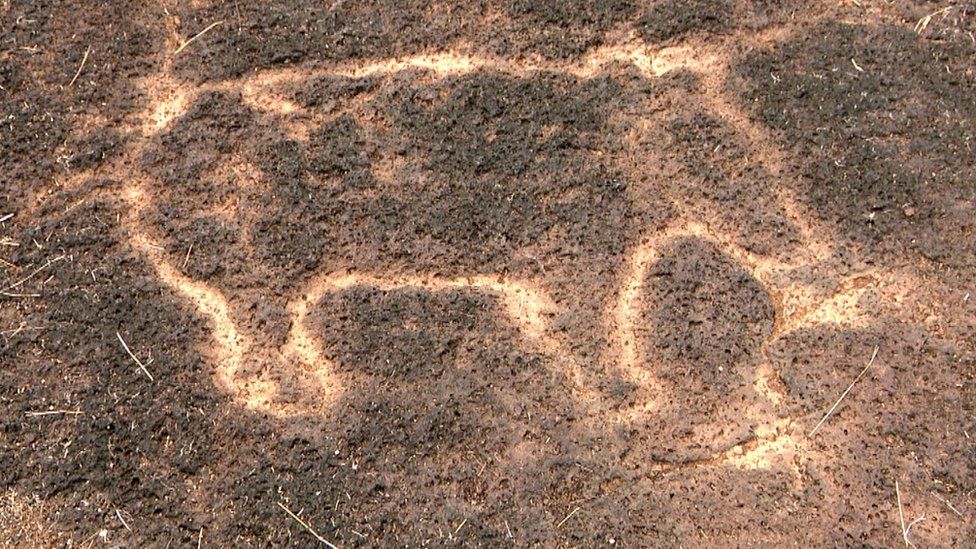

Ratnagiri Petroglyph depicting

Ratnagiri Petroglyph depicting a kangaroo. Source: www.bbc.com.

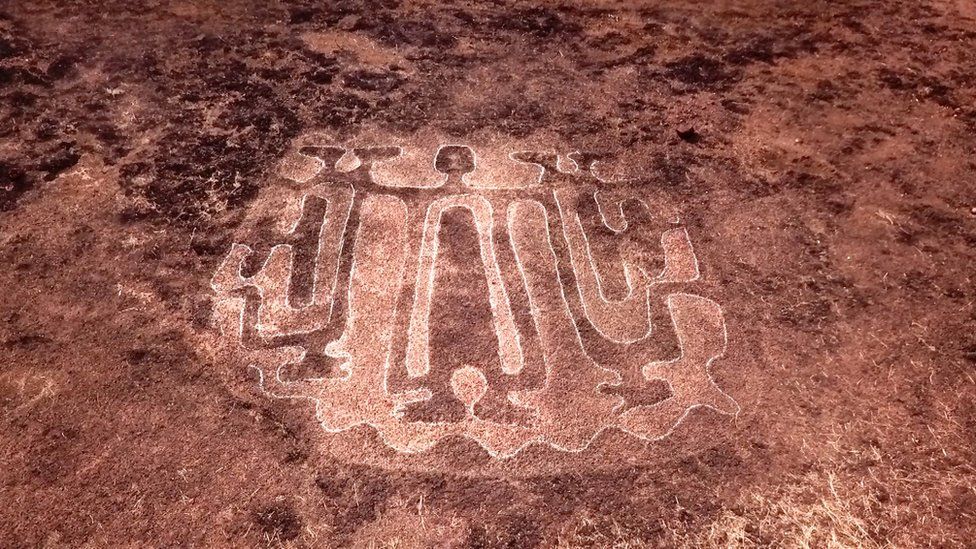

Master of Animals?

Master of Animals?  Ratnagiri Petroglyph showing a figure lifting up a pair of tigers. Source: bbc.com.Compares with:

Ratnagiri Petroglyph showing a figure lifting up a pair of tigers. Source: bbc.com.Compares with: Mohenjo-Daro seal depicting a man grappling with two tigers. Source: harappa.com.

Mohenjo-Daro seal depicting a man grappling with two tigers. Source: harappa.com. Mistress of Animals holding in each hand a lion by its tail. Gold plaque pendant. Kamiros, Rhodes, 720–650 BCE. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Source: www.my-favourite-planet.de

Mistress of Animals holding in each hand a lion by its tail. Gold plaque pendant. Kamiros, Rhodes, 720–650 BCE. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Source: www.my-favourite-planet.de A relief of the Master of Animals from Mesopotamia. 9th — 8th century BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Source: www.my-favourite-planet.de

A relief of the Master of Animals from Mesopotamia. 9th — 8th century BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Source: www.my-favourite-planet.de

Carved by a Lost Ancient Civilisation, ‘History on the Rocks’ Discovered in Ratnagiri!

“The petroglyphs… may be carved by our ancestors in the Neolithic Age, that is 7000-4000 BC. It is very hard to determine the exact period, but these petroglyphs are carved using metal tools, so that is one way of determining the period (of origin).”

by Tanvi PatelOctober 23, 2018, 3:59 pm

As a child, Sudhir Risbood would cycle past a peculiar square-shaped rock, just off the main road in Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri. The concentric circles and artistic curls on the rock made it stand out from the rest.

This rock was different, Risbood knew. But little did he know that it was a clue to a lost ancient civilisation!

Now an engineer working in Konkan, Risbood often cycles and treks in Ratnagiri and Rajapur with his friend, Manoj Marathe. Both of them are electric engineers by profession but have a deep passion for nature and history.

When they were working on a project near the coastal town of Ganpatipule, they came across a rock very similar to the peculiar one that Risbood observed as a child. It was then that it struck him–that it wasn’t by accident that these rocks were unlike the rest in the region.

They held historic importance, evidence even, about ancient cultures.

“In 2012, we decided to see how many more sites like these we could find. We started asking around in the villages and realised that because of the new roads people didn’t walk across the flat rock surfaces any more. But some of the older people knew,” Risbood told The Hindu.

Risbood and Marathe decided to use their passion for trekking and adventure to search for more such rocks. These rocks, were in fact, petroglyphs–images that are carved on rocks as art.

In the following years, the duo unearthed 86 such “drawings” in 10 sites in the Ratnagiri district.

Satish Lalit, who has been studying these petroglyphs in the Konkan region for over 16 years explained, “The petroglyphs… may be carved by our ancestors in the Neolithic Age, that is 7000-4000 BC. It is very hard to determine the exact period, but these petroglyphs are carved using metal tools, so that is one way of determining the period (of origin). The locals had only heard about these images; I asked so many people in these villages about them, but nobody knew the location as nobody had visited the site. They call them Pandava Chitra (pictures) and only knew from their elders that there were some such images on the hill.”

The ancient rock art that Lalit referred to was discovered in Sindhudurg district, just south of Ratnagiri.

Shrikant Pradhan is a professor at Deccan College in Pune. Along with a team of researchers, he has been studying these discoveries to put them in the context of a historical timeframe.

Speaking to The Times of India, Pradhan said, “What we can say from the data gathered till now is that these carvings are from the prehistoric to the early historic period. To prove that it might have been a part of a lost civilisation, we have to find a lot of other things, like stone tools, besides more of these sites. We can also gather that it was definitely not a farming society, but seeing the kind of curvilinear lines on the rocks, there was some advancement in thinking. The lines are abstract but they are in some form, and there is a particular pattern among a lot of them.”

Tejas Garge, Director of Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Maharashtra, added that after studying the available pieces of evidence, the research team has estimated the petroglyphs to be about 25,000 years old.

“If you consider that the records of the port towns are from about 3000 BCE, we are talking of a gap of about 20,000 years. No one knew what happened here during this period,” he said.

This places the period of the petroglyphs in the Mesolithic age (or middle stone age), which existed between the Paleothilic period (old stone age) and Neolithic period (new stone age). The Laterite soil on which they are carved, helped the researchers arrive at this.

Risbood, Marathe and other researchers involved in these projects wish to pursue more such discoveries in and around Ratnagiri so that the ancient artwork can be preserved.

As Garge says, the 86 discoveries could help further explore and determine the period to which these petroglyphs belong. However, with more discoveries and proper conservation, the petroglyphs could prove to be the ancient treasure that leads the way to a whole new chapter in history!

(Edited by Shruti Singhal)

You cannot miss the sculptures which are beautifully carved on the open and vast lateritic plateaus in Ratnagiri. These magnificent rock carvings are made in hard lateritic rock during the Pre-historic era, almost 10,000 years ago. Even though these sculptures which are made of various animals, birds, geometrical structures and ancient hieroglyphics are very mysterious, yet they are a beautiful man-made invention.

More than 280 sculptures have been found in vicinity of Ratnagiri, Rajapur, and Lanja in the Ratnagiri district. Who carved these mysterious sculptures on these plateaus? What was their purpose? What did the ancient man intend to tell us through these sculptures? Although its official information is not available today, more research is being conducted by the scientists. In many places, the size of the carvings of the elephants and tigers are as big as the actual animals. You can also see the carvings of a crocodile, tortoise, fishes, and snakes.But in all the sculptures, you get to see human carvings the most. As geometrical shapes were excavated in the square of Gawadewadi and Nivali phata, the purpose of this carving is yet undiscovered. Many of the sculptures are unfinished but most of them have been carved clearly and beautifully. Sudhir Rishbud and Dhananjay Marathe, the enthusiastic researchers of Ratnagiri, have thoroughly studied these sculptures and made a classified list of them. They have marked the similarities and differences found in the sculptures with their hard work.

Source: (L) Ratnagiri Tourism (R) Sushama Katti/ Facebook.

Rock Carvings in Ratnagiri, Man Made Wonders

Published on Jun 24, 2018

त्रि tri-धातुः an epithet of Gaṇeśa; -तुम् 1 the triple world. -2 the aggregate of the 3 minerals or humours. (Apte lexicon) त्रि--धातु [p= 458,3] mfn. consisting of 3 parts , triple , threefold (used like Lat. triplex to denote excessive) RV. S3Br. v , 5 , 5 , 6; m. (scil. पुरोड्/आश) N. of an oblation TS. ii , 3 , 6. 1 ( -त्व्/अ n. abstr.); n. the triple world RV.; n. the aggregate of the 3 minerals or of the 3 humours W.; m. गणे*श L.

त्रिधातुः is an epithet of Gaṇeśa. tri-dhātu 'three minerals'.This may indicate three forms of ferrite ores: magnetite, haematite, laterite which were identified in Indus Script as poḷa 'magnetite', bichi 'haematite' and goṭa, goṭā 'laterite, ferrite ore'. khoṭ m. ʻbase, alloyʼ goṭī 'lump of silver' (Gujarati); goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ(Kashmiri).

Kur. goṭā any seed which forms inside a fruit or shell. Malt. goṭa a seed or berry(DEDR 069) N. goṭo ʻ piece ʼ, goṭi ʻ chess piece ʼ; A. goṭ ʻ a fruit, whole piece ʼ, °ṭā ʻ globular, solid ʼ, guṭi ʻ small ball, seed, kernel ʼ; B. goṭā ʻ seed, bean, whole ʼ; Or. goṭā ʻ whole, undivided ʼ, M. goṭā m. ʻ roundish stone ʼ (CDIAL 4271) <gOTa>(P) {ADJ} ``^whole''. {SX} ``^numeral ^intensive suffix''. *Kh., Sa., Mu., Ho<goTA>,B.<goTa> `undivided'; Kh.<goThaG>(P), Sa.<goTAG>,~<gOTe'j>, Mu.<goTo>; Sad.<goT>, O., Bh.<goTa>; cf.Ju.<goTo> `piece', O.<goTa> `one'. %11811. #11721. <goTa>(BD) {NI} ``the ^whole''. *@. #10971. (Munda etyma) Rebus: <gota> {N} ``^stone''. @3014. #10171. Note: The stone may be gota, laterite mineral ore stone. khoṭ m. ʻbase, alloyʼ (Punjabi) Rebus: koṭe ‘forging (metal)(Mu.) Rebus: goṭī f. ʻlump of silver' (G.) goṭi = silver (G.) koḍ ‘workshop’ (Gujarati). P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ, H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ(CDIAL 4271) Rebus: goṭa 'laterite' khoṭ m. ʻbase, alloyʼ (Punjabi) koṭe ‘forging (metal)(Mu.) Rebus: goṭī f. ʻlump of silver' (G.) goṭi = silver (G.) koḍ ‘workshop’ (Gujarati).

See:

An archaeology of R̥gveda https://tinyurl.com/yahba38c

(Silver/gold braid products of furnace) Investigated daybook![]() FSFig. 123 (FS 85) associated with

FSFig. 123 (FS 85) associated with ![]() (Freq. 11) bhaṭa 'warrior' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'कारणिक investigating; khareḍo 'a currycomb' rebus: kharada खरडें daybook. M. goṭā m. ʻ roundish stone ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ a marble ʼ, goṭuḷā ʻ spherical ʼ; Si. guṭiya ʻ lump, ball ʼ rebus: P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ,H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ.*gōḍḍ -- ʻ dig ʼ see *khōdd -- .Addenda: *gōṭṭa -- : also Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271)

(Freq. 11) bhaṭa 'warrior' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'कारणिक investigating; khareḍo 'a currycomb' rebus: kharada खरडें daybook. M. goṭā m. ʻ roundish stone ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ a marble ʼ, goṭuḷā ʻ spherical ʼ; Si. guṭiya ʻ lump, ball ʼ rebus: P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ,H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ.*gōḍḍ -- ʻ dig ʼ see *khōdd -- .Addenda: *gōṭṭa -- : also Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271)

Hieroglyph: seed, something round:

gōṭī 'round pebble'

*gōṭṭa ʻ something round ʼ. [Cf. guḍá -- 1. -- In sense ʻ fruit, kernel ʼ cert. ← Drav., cf. Tam. koṭṭai ʻ nut, kernel ʼ, Kan. goṟaṭe &c. listed DED 1722]K. goṭh f., dat. °ṭi f. ʻ chequer or chess or dice board ʼ; S. g̠oṭu m. ʻ large ball of tobacco ready for hookah ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; P. goṭ f. ʻ spool on which gold or silver wire is wound, piece on a chequer board ʼ; N. goṭo ʻ piece ʼ, goṭi ʻ chess piece ʼ; A. goṭ ʻ a fruit, whole piece ʼ, °ṭā ʻ globular, solid ʼ, guṭi ʻ small ball, seed, kernel ʼ; B. goṭā ʻ seed, bean, whole ʼ; Or. goṭā ʻ whole, undivided ʼ, goṭi ʻ small ball, cocoon ʼ, goṭāli ʻ small round piece of chalk ʼ; Bi. goṭā ʻ seed ʼ; Mth. goṭa ʻ numerative particle ʼ; H. goṭf. ʻ piece (at chess &c.) ʼ; G. goṭ m. ʻ cloud of smoke ʼ, °ṭɔ m. ʻ kernel of coconut, nosegay ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ lump of silver, clot of blood ʼ, °ṭilɔ m. ʻ hard ball of cloth ʼ; M. goṭā m. ʻ roundish stone ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ a marble ʼ, goṭuḷā ʻ spherical ʼ; Si. guṭiya ʻ lump, ball ʼ; -- prob. also P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ, H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ.*gōḍḍ -- ʻ dig ʼ see *khōdd -- .Addenda: *gōṭṭa -- : also Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271) Ta. koṭṭai seed of any kind not enclosed in chaff or husk, nut, stone, kernel; testicles; (RS, p. 142, items 200, 201) koṭṭāṅkacci, koṭṭācci coconut shell. Ma. koṭṭakernel of fruit, particularly of coconut, castor-oil seed; kuṟaṭṭa, kuraṭṭa kernel; kuraṇṭi stone of palmfruit. Ko. keṭ testes; scrotum. Ka. koṭṭe, goṟaṭe stone or kernel of fruit, esp. of mangoes; goṭṭa mango stone. Koḍ. koraṇḍi id. Tu. koṭṭè kernel of a nut, testicles; koṭṭañji a fruit without flesh; koṭṭayi a dried areca-nut; koraṇtu kernel or stone of fruit, cashew-nut; goṭṭu kernel of a nut as coconut, almond, castor-oil seed. Te. kuriḍī dried whole kernel of coconut. Kol. (Kin.) goṛva stone of fruit. Nk. goṛage stone of fruit. Kur. goṭā any seed which forms inside a fruit or shell. Malt. goṭa a seed or berry. / Cf. words meaning 'fruit, kernel, seed' in Turner, CDIAL, no. 4271 (so noted by Turner).(DEDR 2069) Rebus: khōṭa 'alloy ingot' (Marathi) goṭi, ‘silver, laterite’.

The petroglyphs of Ratnagiri

OCTOBER 20, 2018 00:15 IST![A large engraving of an elephant in Ukshi village in north Ratnagiri, where a circular viewing gallery has been constructed, along with an inscription that explains the art workâs significance.]()

A large engraving of an elephant in Ukshi village in north Ratnagiri, where a circular viewing gallery has been constructed, along with an inscription that explains the art work’s significance. | Photo Credit: Prashant Nakwe

The recent discovery of 1,000 rock carvings on Maharashtra’s Konkan coast is expected to provide new insights into the early history of the region. Jayant Sriram reports on the archaeological significance of these petroglyphs, which are estimated to be 12,000 years old.

The colour of the setting sun matches the ferrous red of the porous laterite rock that dominates the terrain of Ratnagiri and Rajapur along Maharashtra’s Konkan coast. At a quarter past six in the evening, in the small village of Devache Gothane, when there is finally some respite from the heat, the two shades converge, casting a soft glow on the lush grass that covers the flat hilltops. The monsoon has evidently been generous to this region. A steep climb from the village ends in an endless expanse of such grass. But the sight that greets you in the middle of it, on a patch where the heat has baked the surface of the red laterite black, makes the climb worth it.

An oval ring of stones frames an image carved into the laterite. It depicts a human form — a man standing feet akimbo, arms loose by his side. The carving is about eight feet long. It’s the head that is most striking, framed by a kind of aura or halo. Something about the vastness of that meadow, the rapidly fading light, and the eerie nature of that single carving in a desolate field evokes a strange excitement. A small window into another world.

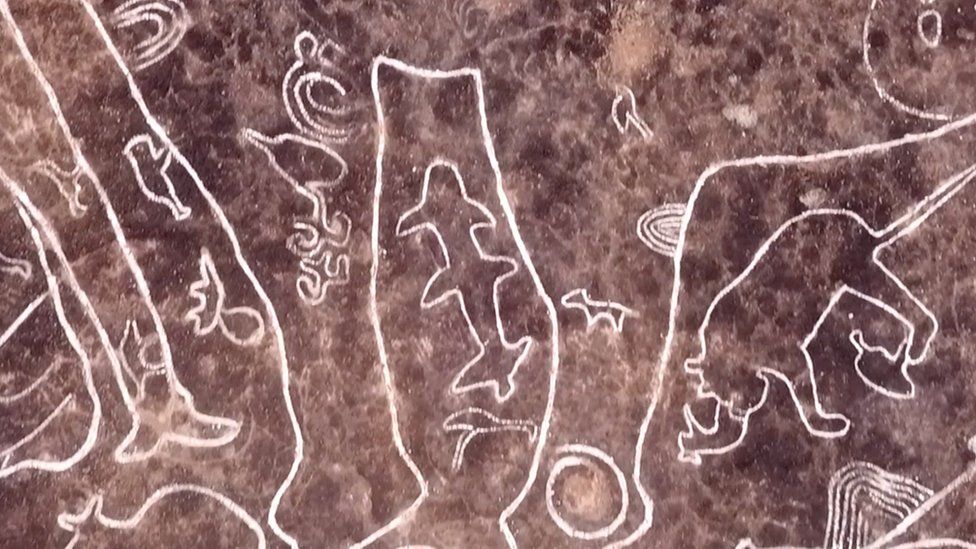

This carving is one of the over 1,000 such petroglyphs that have been discovered in and around the Ratnagiri and Rajapur districts over the last two or three years, making them one of the most significant archaeological finds of recent times. The carvings cover over 52 sites across the region. The 12 sites that The Hindu travelled to contained an incredible range of images, from basic depictions of human and animal forms to a stunning 50-ft carving of an elephant, within which a series of smaller animal and aquatic forms were drawn. From abstract patterns and fertility symbols carved rudimentarily on the rock surface to dizzyingly complex geometric reliefs cut deep into the rock, the etchings seem straight out of the movie Signs or the television series Lost. The term rock art usually brings to mind pictographs (paintings on rocks). But these are petroglyphs, and the fact that the images are carved into the flat, open rock surface gives them a scale and look that is unique.

Filling a gap in history

“These petroglyphs fill a huge gap in the history of the Konkan region,” says Tejas Garge, Director, Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Maharashtra. There is ample evidence that in the medieval age, the Konkan coast was lined with important port towns. It has been reconstructed from epigraphs and contemporaneous records that it has a history of trade and contact with Europe, and even with the Roman Empire. But there was a big void regarding what went on here in prehistoric times. Some evidence has come from the caves in the region. A team of researchers from Deccan College, Pune, discovered stone tools that were estimated to be 25,000 years old. “If you consider that the records of the port towns are from about 3,000 BCE, we are talking of a gap of about 20,000 years. No one knew what happened here during this period,” Garge says.

The working theory around these petroglyphs is that they date back to about 10,000 BCE, placing them in the Mesolithic Period, which comes between the Old Stone Age or Paleolithic period, characterised by chipped stone tools, and the New Stone Age or Neolithic period, associated with smaller, more polished tools. The basis for this reasoning are two-fold. The first is that the petroglyph style of art is associated in other archaeological sites with tools from the Mesolithic period. Second, near one petroglyph site in the village of Kasheli, about 25 km from Ratnagiri city, Garge’s team also found evidence of stone tools, along with the petroglyphs dating back to this time. More precise dating may be hindered at this point, he explains, partly because of the way in which many of these sites were discovered.

“These were accidental discoveries by amateurs. As often happens in such cases, they cleared away much of the soil around the carvings, soil that would normally have been part of the archaeological record,” he says. Accidental discovery by explorers is not uncommon in archaeology, Garge says, adding that amateurs account for about 20% of all the world’s archaeological discoveries.

The road to discovery

In 2010, Sudhir Risbood, an electrical engineer, started a campaign and an informal group called Adgalnavarche Konkan, or Unexplored Konkan. Risbood is a keen ornithologist and a passionate raconteur of Konkan history. His eyes light up when he speaks of the different kinds of beaches in the region (black sand, red sand, and white sand), and the multitude of forts and temples that have become tourist attractions. For years now, he has been building replicas of the forts of Ratnagiri, Raigad, and Sindhudurg for public display. He likes to regale students and history enthusiasts with tales of how they were built and operated.

Unexplored Konkan is a motley crew of like-minded individuals who are all into documenting nature. Manoj Marathe, like Risbood, is also an electrical engineer, but with a passion for butterflies. Surendra Thakurdesai is a geography professor with a deep interest in snakes. Along the way, they acquired a rotating cast of allies which included the Superintendent of Police and Collector of Ratnagiri district.

In 2012, Risbood came up with a plan to expand the group’s activities. Having grown up in Ratnagiri, he remembered having seen, as a school boy, a square rock relief pattern just off the road near the village of Nivali, about 17 kilometres from Ratnagiri city. “I would cycle pass it and wonder what it was,” he says. It was full of interlocking curls and concentric circles, Risbood recalls, but of course, he had no idea that he was seeing a petroglyph from an ancient culture. But he did know that the local tribal population treated it with reverence, as a legacy of their forefathers.

Years later, in the mid-2000s, while doing a project in the area around the Aryadurga temple and Ganpatipule, Risbood came across more such rock carvings. “In 2012, we decided to see how many more sites like these we could find. We started asking around in the villages, and realised that because of the new roads people didn’t walk across the flat rock surfaces any more. But some of the older people knew.”

A shepherd was the first to volunteer information. He plotted a location for them by describing a boundary wall and the shape of bushes around the petroglyph. From then on, there was no looking back. Three sites became 52, and Rajapur and the number of petroglyphs recorded grew to over a thousand. When the new director of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums (Garge) visited Ratnagiri in 2016, Risbood sought a meeting. He showed sketches of the petroglyphs to Garge and took him to some of the locations. In 2017, Garge transferred a young Archaeology Department official, Rutwij Apte, from Pune to Ratnagiri to work full time on the petroglyphs. Currently, Apte and Risbood’s crew are in charge of the project.

As much as they are involved in discovering and documenting the sites, Risbood and Apte, along with Manoj Marathe, have also started speaking to the local villagers about the importance of the sites and the need to protect them. The ring of stones around the human carving in Devache Gothane is one such attempt. In other sites, particularly where the petroglyphs fall in land that is mined for laterite stone, widely used in construction across the western coast, they have convinced the land owners to erect brick boundaries protecting the sites. Help also arrived from the Collector, Radhakrishnan B., who put a halt to mining around some sites. In the village of Ukshi in north Ratnagiri, for a large engraving of an elephant, the team worked with local authorities to construct a circular viewing gallery, complete with an inscription that explains the art work’s significance.

Decoding their significance

What do we know so far about the significance of these petroglyphs? The Ratnagiri project is yet to focus on comparative analysis. But these carvings could be contemporaneous to other petroglyph sites in India that date back to the Middle and Later Stone Age. The period in history preceding the Indus Valley Civilisation, which is dated to about 5,000 BCE, is a rich one of historical discovery, with evidence of stone tool cultures scattered across the subcontinent.

Prominent petroglyph and rock art sites in India that could be contemporary to this period are the Bhimbetka rock shelters in Madhya Pradesh, rock carvings in Mirzapur in Uttar Pradesh, petroglyphs from the Tindivanam and Viluppuram districts in Tamil Nadu and Unakoti in Tripura. The carvings on laterite stone are what make the petroglyphs in this region unique, as the carvings discovered in other sites around India are on granite and sandstone. More recently, petroglyphs of a similar nature, though not in the same numbers, have been discovered in Sindhudurg district, and near the banks of the Kushavati river in Goa. Both are south of Ratnagiri, hinting at a pattern of migration.

Garge is quick to point out that this is not yet evidence of a civilisation, as there is no evidence of writing, agricultural or economic activity, or of living arrangements or settlements. It’s more likely, he says, that these were nomadic tribes, with the preponderant depiction of animals and aquatic life suggesting that they were hunter-gatherer tribes. Interestingly, there are no actual scenes depicting the hunting of animals, unlike the carvings in Bhimbetka and Mirzapur. “In Maharashtra’s cultural records, there is no evidence of any art being practised until about 3,000 BCE, which is when we find the first mention of painted pots and clay figurines. That’s why these petroglyphs are a significant find for a better understanding of the history of this region and its artistic traditions,” Garge says.

It could be argued that the very content of the petroglyphs points to their relevance. For starters, some of them depict rhinoceroses and hippopotami, two species that were never thought to be prevalent in this part of India. The carvings, however, suggest that the Konkan may have once been a lot like the rainforests where these animals are typically found.

More pertinent, perhaps, is the scale of the art itself. “We have to ask what is the purpose behind all these carvings. In many of the cases, what we have are not rudimentary scratches but carvings with a great deal of detail. Some are incredible life-size depictions of large animals such as elephants and tigers,” Garge says. Most of the art from the later medieval period is religious in nature, he says, and it is quite likely that such a significant investment in art points to some form of religious belief or religious system.

An eight ftlong petroglyph in Devache Gothane village in Rajapur district, Maharashtra. | Photo Credit: Prashant Nakwe

Many of the petroglyphs are accompanied by abstract motifs and symbols, the meaning of which is not yet known. The most intriguing of these is the motif of two legs, squatting and spread outward. The symbol is cut off at the hip and is usually deployed as a side motif to the larger, more abstract rock reliefs. “Images from later periods depict a goddess called Lajja Gauri who is similarly portrayed, squatting and with legs facing outward, though in those cases the rest of the body is also shown. We are exploring a link between the two,” Garge says.

Apte believes that some of the more complex reliefs, etched deep into the ground, may have been done using metal tools rather than stone. If his theory is proven right, then just as in sites like Bhimbetka, where art has been dated from prehistoric times right down to the medieval period, it could point to a continuous habitation of this region, across millennia, possibly by various nomadic tribes. Apte, who is now doing his PhD on these petroglyphs, is also working on a theory that the carvings get more complex as one moves from north to south, suggesting a pattern of migration in this direction over many centuries. One of the most complex petroglyphs The Hindu visited, in the village of Barsu at the southern tip of Ratnagiri, was a large image of a man standing with two tigers (etched stylistically with precise geometric shapes) flanking him on either side. The carvings in the north of Ratnagiri district are more basic depictions of animal and human forms.

Stage set for further research

The discovery of these sites marks the commencement of what is likely to be a long project. “We still need to look for more evidence of stone tools and evidence of settlements around these sites so that we can do a more accurate dating,” Apte says. So far, such evidence has been hard to come by in Ratnagiri and Rajapur, though there have been recent reports of some caves with petroglyphs being discovered in the Sindhudurg region. To discover more such petroglyph sites, Garge is also planning to deploy drones to cover areas of open laterite rock surface that are not yet accessible. Then there is the question of comparative analysis and collaboration with various universities to understand more about these sites. Maharashtra’s Archaeology Department is already in the process of putting together an academic paper detailing these findings.

For now, while the State government has set aside ₹24 crore for further research on these sites, a lot of administrative work still needs to be done if they are to be showcased as tourist attractions for the region. For a start, the sites need to be notified as archaeological heritage. Then, as Risbood explains, the State government will have to engage in a long process of land acquisition that could prove tricky.

“We have already spoken to many of the villagers in this region. Some are willing to work in partnership with the government because they realise the importance of these sites,” Risbood says. This would involve a system whereby viewing galleries are created and the villagers are able to charge a small fee and possibly sell tea and snacks. The Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation has already shown interest in developing some of these sites and incorporating them into the tourist circuit of a region that attracts a lot of travellers, drawn to it by the beaches and famous temples such as Ganpatipule.

Going forward, Risbood concedes that a more coherent narrative needs to be woven around some of the more prominent sites. Promoting tourism and the unknown wonders of the Konkan region is, of course, his passion. The heaps of documents that he has gathered for each site also include rudimentary drawings for viewing galleries and detailed plans for partnership with the villagers. That story, as also the unfolding archaeological research on these sites, is likely to be an even more exciting one.

https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/the-petroglyphs-of-ratnagiri/article25265399.ece

Rock Art of the Himalayas, Tibet and Central Asia. Photos by Rob Linrothe.

Pictures: Possibly 12,000 Years Old

Before there were books, before there was writing, there was art. We don’t know why that instinct welled up in early humans to make a mark, to render their world in images, but we know it did because the results endure today. In the Ratnagiri District of the Indian state of Maharashtra, I saw petroglyphs carved into the porous laterite rock beds that lie scattered among fields, in this area famous for its distinctive Alfonso mangoes.

Here is an elephant, its eye-folds delicately marked, its tusks and ears and trunk clearly defined, recognizable even after millennia of exposure to sun and wind and blowing sands:

Documenting the petroglyphs has been an entirely voluntary enterprise, led by two men, both engineers by profession, both with deep connections to the region and with driving interests in birds and butterflies respectively: Sudhir Risbood and Manoj Marathe. With the help of volunteers, they have located up to 1,500 discrete images at over 50 sites. They’re also speaking to local villagers about the importance of the sites and the need to protect them–and trying to decide what form such protection would take.

Documenting the petroglyphs has been an entirely voluntary enterprise, led by two men, both engineers by profession, both with deep connections to the region and with driving interests in birds and butterflies respectively: Sudhir Risbood and Manoj Marathe. With the help of volunteers, they have located up to 1,500 discrete images at over 50 sites. They’re also speaking to local villagers about the importance of the sites and the need to protect them–and trying to decide what form such protection would take.Some of the carvings are bold and representational. Here’s a monkey. ![Ukshi2.jpg]()

The seashore’s pretty close, so as one might expect, there are fish. ![Ratnagiri3.jpg]() And peacocks, and tigers, and rhinos as well, in an area far from current rhinoceros habitat. And then there is this strange figure, stylized and enigmatic:

And peacocks, and tigers, and rhinos as well, in an area far from current rhinoceros habitat. And then there is this strange figure, stylized and enigmatic:![Rajapur.jpg]()

And peacocks, and tigers, and rhinos as well, in an area far from current rhinoceros habitat. And then there is this strange figure, stylized and enigmatic:

And peacocks, and tigers, and rhinos as well, in an area far from current rhinoceros habitat. And then there is this strange figure, stylized and enigmatic:

There are other sites with prehistoric rock art elsewhere in India–the rock shelter paintings of Bhimbetka, the carvings in the Edakkal caves in Kerala’s Wayanad, and others. We don’t know yet how the Ratnagiri sites fit in with all those others. That is yet to be studied.

What now? What do you do when you have a treasure like this on your hands, scattered over a large area, across a patchwork of private and public lands? Marathe and Risbood both speak of a holistic vision–of a region designated not only as a site with historical and cultural significance but also a biosphere, rich in plant, bird, and butterfly species, and home to people with real-life stakes in the place. Stewardship is only possible, they argue, when you create it from the ground up. It can’t be imposed by governmental fiat and it shouldn’t be dictated by politicians and bureaucrats who don’t understand local concerns.

As we left the last figure–who is it meant to be and what is it saying? No one knows–I felt strangely moved. When a vast work of art lies at your feet, almost too large for your eyes to take in all at once, you cannot help but think about the mind or minds that dreamed it up, and the hands that held the chipping quartz. You cannot help but wonder what meaning we should draw from this human urge to think about the world around us, to recreate it in stone.

As the documentation and protection of these sites progresses, Sudhir Risbood can be contacted via old-fashioned post at the following address:

B-09 Shri Datta Sankul

Ghanekar Alley

Subhash Road

Ratnagiri 415612

Maharashtra

India

Ghanekar Alley

Subhash Road

Ratnagiri 415612

Maharashtra

India

mēḍi 'Ficus glomerata' in Indus Script Sanauli anthropomorph is rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron', mēṭi 'chief', meũ, muhāṇo 'boatman' (mintmaster)

See:

మేటి or మేటరి mēṭi [Tel.] n. A chief, leader, head man, lord, శ్రేష్ఠుడు, అధిపుడు. adj. Chief, excellent, noble. శ్రేష్ఠమైన. మేటిదొర a noble man, lord. Bilh. ii. 50. మెరయుచునుండెడి మేటీరంబులు మేటీరంబులు, అనగా మేటి, గొప్పలైన, ఈరంబులు, పొదలు large bushes. "తేటైనపన్నీట తీర్థంబులాడి, మేటికస్తూరిమేనెల్లబూసి." Misc. iii. 322. మేటిగా = మెండుగా. మేటిల్లు mētillu. v. n. To excel. అతిశయించు. Ta. mēṭṭi haughtiness, excellence, chief, head, land granted free of tax to the headman of a village; mēṭṭimai haughtiness; leadership, excellence. Ka. mēṭi loftiness, greatness, excellence, a big man, a chief, a head, head servant. Te.mēṭari, mēṭi chief, head, leader, lord; (prob. mēṭi < *mēl-ti [cf. 5086]; Ka. Ta. < Te.; Burrow 1969, p. 277).(DEDR 5091)

మేదర mēdara. [Tel.] n. The basket maker caste. గంపలల్లే ఒక జాతి. మేదరది or మేదరసాని a woman of that caste. మేదరకులము the basket weaver's caste. మేదరపెట్టె a bamboo box. మేదరి or మేదరవాడు a basket maker. మేదరచాప a bamboo mat. Ta. mētaravar, mētavar a class of people who do bamboo work. Ka. mēda, mēdā̆ra, mādara man who plaits baskets, mats, etc. of bamboo splits, man of the basket-maker caste. Koḍ. me·dë man of caste who make baskets and leaf-umbrellas and play drums at ceremonies; fem. me·di. Te. mēdara, mēdari the basket-maker caste, a basket-maker; of or pertaining to the basket-maker caste. Kuwi (S.) mētri, (Isr.) mētreˀ esi matmaker. / Cf. Skt. meda- a particular mixed caste; Turner, CDIAL, no. 10320. (DEDR 5092) mēda m. ʻ a mixed caste, any one living by a degrading occupation ʼ Mn. [→ Bal. mē

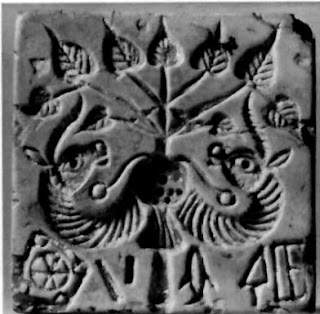

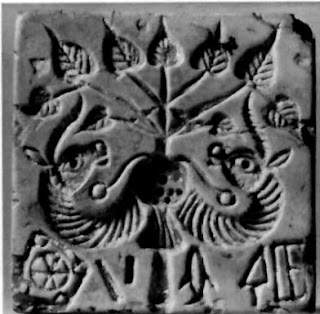

Mohenjo-daro Seal impression. m0296 Two heads of one-horned bulls with neck-rings, joined end to end (to a standard device with two rings coming out of the top part?), under a stylized tree-branch with nine leaves.

P

Hypertext: Pair of rings attached to string, pair of young bulls: dol 'likeness, picture, form' (Santali) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast iron' (Santali) dul ‘to cast metal in a mould’ (Santali) dul meṛeḍ cast iron (Mundari. Santali) కమ్మరు kammaru or కమరు kammaru. [Tel.] n. A girdle. మొలనూలు. కమ్మరము kammaramu kammaramu. [Tel.] n. Smith's work, iron work. కమ్మరవాడు, కమ్మరి or కమ్మరీడు kammara-vāḍu. n. An iron-smith or blacksmith. బైటికమ్మరవాడు an itinerant blacksmith. कर्मार karmāra m. an artisan , mechanic , artificer, a blacksmith &c ऋग्-वेद RV. x , 72 , 2 AV. iii , 5 , 6 VS. Mn. iv , 215 &c (Monier-Williams)

Thus, semantics of 'metalcasting' should be used to expand the meanings of associated hypertexts of 'young bull' or 'ring' hieroglyphs.

Hieroglyphs which compose the hypertext on m296 are vivid and unambiguous.

Hieroglyph:Nine, ficus leaves: 1.loa 'ficus glomerata' (Santali) no = nine (B.) on-patu = nine (Ta.)

rebus: lo 'iron' (Assamese) loa ‘iron’ (Gypsy) lauha = made of copper or iron (Gr.S'r.); metal, iron (Skt.); lohakāra = coppersmith, ironsmith (Pali);lohāra = blacksmith (Pt.); lohal.a (Or.); loha = metal, esp. copper or

bronze (Pali); copper (VS.); loho, lo = metal, ore, iron (Si.) loha lut.i = iron utensils and implements (Santali)

Exact number of nine ficus leaves occur together with a zebu tied to a post, on another artifact of Mehi, a site of the civilization.

Hieroglyph: loa 'a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata, the fruit of ficus glomerata (Santali)

kamaṛkom ‘ficus’ (Santali); Rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭamcoinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner (DEDR 1236)

Hieroglyph: Semantic determinative of portable furnace:

koṭ = neck (Gujarati) koḍ 'horn' koḍiyum ‘heifer’ (G.). Rebus: koṭ ‘workshop’ (Kuwi) koṭe = forge (Santali) kōḍiya, kōḍe = young bull (G.)Rebus: ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tulu) Pair:

koṭ = neck (Gujarati) koḍ 'horn' koḍiyum ‘heifer’ (G.). Rebus: koṭ ‘workshop’ (Kuwi) koṭe = forge (Santali) kōḍiya, kōḍe = young bull (G.)Rebus: ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tulu) Pair: kondh 'young bull' rebus: kũdār 'turner, brass-worker, engraver (writer)' kundaṇa 'fine gold'. Thus apair of young bulls signify the hypertext: dul kundaṇa koḍ 'metalcaster goldsmith workshop'.

Hieroglyph: गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A roundish stone or pebble. 2 A marble Rebus: गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe. Thus, the hypertext reads: dul gōṭī khār 'silver metalcaster smith'.

Rebus: khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार ; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन् , which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-basta खार -बस््त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith. -büṭhü -ब&above;ठू&below; । लोहकारभित्तिः f. the wall of a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -bāy-बाय् । लोहकारपत्नी f. a blacksmith's wife (Gr.Gr. 34). -dŏkuru । लोहकारायोघनः m. a blacksmith's hammer, a sledge-hammer.; । लोहकारचुल्लिः f. a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -hāl -हाल् । लोहकारकन्दुः f. , a blacksmith's smelting furnace; cf. hāl । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter. । लोहकारपुत्रः m. the son of a blacksmith, esp. a skilful son, who can work at the same profession. । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter, esp. one who has the virtues and qualities properly belonging to her father's profession or caste. -më˘ʦü 1 -म्य&above;च&dotbelow;ू&below; । लोहकारमृत्तिका f. (for 2, see [khāra 3] ), 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore.; । लोहकारात्मजः m. a blacksmith's son. -nay -नय् । लोहकारनालिका f. (for khāranay 2, see [khārun] ), the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting. -ʦañĕ -च्&dotbelow;ञ । लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wān वान् । लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 3). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि ), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil. (Kashmiri)Rebus: khara 'sharp-edged' Kannada); pure, unalloyed (Kashmiri)

Text of the Indus Script inscription m296

kana, kanac =corner (Santali); Rebus: kañcu, 'bell-metal' (Telugu) कंस mn. ( √कम् Un2. iii , 62), a vessel made of metal , drinking vessel , cup , goblet AV. x , 10 , 5 AitBr. S3Br. &c; a metal , tutanag or white copper , brass , bell-metal (Monier-Williams) kana, kanac =corner (Santali); Rebus: kañcu, 'bell-metal' (Telugu) कंस mn. ( √कम् Un2. iii , 62), a vessel made of metal , drinking vessel , cup , goblet AV. x , 10 , 5 AitBr. S3Br. &c; a metal , tutanag or white copper , brass , bell-metal (Monier-Williams)?nave; erakōlu = the iron axle of a carriage (Ka.M.); cf. irasu (Kannada) [Note Sign 391 and its ligatures Signs 392 and 393 may connote a spoked-wheel, nave of the wheel through which the axle passes; cf. ar ā, spoke]erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal);crystal (Kannada) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tulu) Rebus: eraka = copper (Ka.)eruvai =copper (Ta.); ere - a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a = syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.)Vikalpa: ara, arā (RV.) = spoke of wheel ஆரம்² āram , n. < āra. 1. Spoke of a wheel. See ஆரக்கால். ஆரஞ்சூழ்ந்தவயில்வாய்நேமியொடு (சிறுபாண். 253). Rebus: ஆரம்brass; பித்தளை.(அக. நி.)  kuṭi = a slice, a bit, a small piece (Santali.Bodding) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘iron smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṭhī kuṭi = a slice, a bit, a small piece (Santali.Bodding) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘iron smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṭhīfactory (A.)(CDIAL 3546)  Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa‘arrow’; rebus: ayaskāṇḍa. ayas 'alloy metal' The sign sequence is ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron,excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) ayo, hako 'fish'; a~s = scales of fish (Santali); rebus: aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) DEDR 191 Ta. ayirai, acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitis thermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma. ayala a fish, mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind of small fish, loach. ayir = iron dust, any ore (Ma.) aduru = gan.iyindategadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddha_nti Subrahman.ya’ S’astri’s new interpretationof the Amarakos’a, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330) DEDR 192 Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir,ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru nativemetal. Tu. ajirdakarba very hard iron Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa‘arrow’; rebus: ayaskāṇḍa. ayas 'alloy metal' The sign sequence is ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron,excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) ayo, hako 'fish'; a~s = scales of fish (Santali); rebus: aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) DEDR 191 Ta. ayirai, acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitis thermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma. ayala a fish, mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind of small fish, loach. ayir = iron dust, any ore (Ma.) aduru = gan.iyindategadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddha_nti Subrahman.ya’ S’astri’s new interpretationof the Amarakos’a, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330) DEDR 192 Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir,ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru nativemetal. Tu. ajirdakarba very hard iron अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c ; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold Naigh.; steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.])(Monier-Williams) Thus, in R̥gveda, the falsifiable hypothesis is that ayas signified 'alloy metal' in the early Tin-Bronze Revolution.  kole.l 'temple, smithy' (Kota); kolme ‘smithy' (Ka.) kol ‘working in iron, blacksmith (Ta.); kollan- kole.l 'temple, smithy' (Kota); kolme ‘smithy' (Ka.) kol ‘working in iron, blacksmith (Ta.); kollan-blacksmith (Ta.); kollan blacksmith, artificer (Ma.)(DEDR 2133) kolme =furnace (Ka.) kol = pan~calo_ha (five metals); kol metal (Ta.lex.) pan~caloha = a metallic alloy containing five metals: copper, brass, tin, lead and iron (Skt.); an alternative list of five metals: gold, silver, copper, tin (lead), and iron (dhātu; Nānārtharatnākara. 82; Man:garāja’s Nighaṇṭu. 498)(Ka.) kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, an aboriginal tribe if iron smelters speaking a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali) kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Telugu) Thus, Part 2 of hypertext reads: ayaskāṇḍa kole.l 'smithy/forge excellent quantity of iron' Both Part 1 an Part 2 of ypertext together: kamsa āra kuṭhi 'bronze (bell-meta), brass smelter'; ayaskāṇḍa kole.l 'smithy/forge excellent quantity of iron (alloy metal)' |

loa 'ficus glomerata' (Santali); Phonetic determinative: lo 'nine' (Santali.Bengali) rebus: lo 'iron' (Assamese)

poḷa 'zebu' rebus; poḷa 'magnetite'

mēdhi 'post to tie cattle to' rebus: मृदु mṛdu, mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Santali.Mu.Ho.);med 'copper' (Slavic)Ficus glomerata: loa, kamat.ha = ficus glomerata (Santali); rebus: loha = iron, metal (Skt.) kamat.amu, kammat.amu = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.) kammat.i_d.u = a goldsmith, a silversmith (Te.) kampat.t.tam coinage coin (Ta.);kammat.t.am kammit.t.am coinage, mint (Ma.); kammat.a id.; kammat.i a coiner (Ka.)(DEDR 1236) ḍāṅgā 'mountain' rebus: ṭhākur, dhangar 'blacksmith'. Nepali. ḍāṅro ʻterm of contempt for a blacksmithʼ(CDIAL 5524)

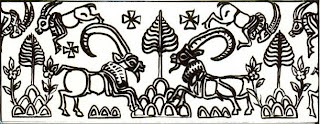

Sumerian cylinder seal showing flanking goats with hooves on tree and/or mountain. Uruk period. (After Joyce Burstein in: Katherine Anne Harper, Robert L. Brown, 2002, The roots of tantra, SUNY Press, p.100)Hence, two goats + mountain glyph reads rebus: meḍ kundār 'iron turner'. Leaf on mountain: kamaṛkom 'petiole of leaf'; rebus: kampaṭṭam 'mint'. loa = a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata, the fruit of ficus glomerata (Santali) Rebus: lo ‘iron’ (Assamese, Bengali); loa ‘iron’ (Gypsy). The glyphic composition is read rebus: meḍ loa kundār 'iron turner mint'. kundavum = manger, a hayrick (G.) Rebus: kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner's lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295) This rebus reading may explain the hayrick glyph shown on the sodagor 'merchant, trader' seal surrounded by four animals.Two antelopes are put next to the hayrick on the platform of the seal on which the horned person is seated. mlekh 'goat' (Br.); rebus: milakku 'copper' (Pali); mleccha 'copper' (Skt.) Thus, the composition of glyphs on the platform: pair of antelopes + pair of hayricks read rebus: milakku kundār 'copper turner'. Thus the seal is a framework of glyphic compositions to describe the repertoire of a brazier-mint, 'one who works in brass or makes brass articles' and 'a mint'. Markhor:mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4 , miṇḍha -- 2 , °aka -- , mēṭha -- 2 , mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2 , °aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ]

*l m0296 Seal impression. Decoding of a very remarkable set of glyphs and a 5-sign epigraph on a seal, m0296, together with a review of few other pictographs used in the writing system of Indus script. This seal virtually defines and prefaces the entire corpus of inscriptions of mleccha (cognate meluhha) artisans of smithy guild, caravan of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. The center-piece of the orthography is a stylized representation of a 'lathe' which normally is shown in front of a one-horned young bull on hundreds of seals of Indus Script Corpora. This stylized sãghāṛɔ 'lathe' is a layered rebus-metonymy to denote 'collection of implements': sangāṭh संगाठ् । सामग्री m. (sg. dat. sangāṭas संगाटस्), a collection (of implements, tools, materials, for any object), apparatus, furniture, a collection of the things wanted on a journey, luggage, and so on. This device of a stylized 'lathe' is ligatured with a circular grapheme enclosing 'protuberances' from which emanate a pair of 'chain-links'. These hieroglyphs are also read as rebus-metonymy layers to represent a specific form of lapidary or metalwork: goṭī 'lump of silver' (Gujarati); goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ(Kashmiri). Thus, a collection of hieroglyphs are deployed as rebus-metonymy layered encryptions, to convey a message in Meluhha (mleccha) speech form.

m0296 Seal impression. Decoding of a very remarkable set of glyphs and a 5-sign epigraph on a seal, m0296, together with a review of few other pictographs used in the writing system of Indus script. This seal virtually defines and prefaces the entire corpus of inscriptions of mleccha (cognate meluhha) artisans of smithy guild, caravan of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. The center-piece of the orthography is a stylized representation of a 'lathe' which normally is shown in front of a one-horned young bull on hundreds of seals of Indus Script Corpora. This stylized sãghāṛɔ 'lathe' is a layered rebus-metonymy to denote 'collection of implements': sangāṭh संगाठ् । सामग्री m. (sg. dat. sangāṭas संगाटस्), a collection (of implements, tools, materials, for any object), apparatus, furniture, a collection of the things wanted on a journey, luggage, and so on. This device of a stylized 'lathe' is ligatured with a circular grapheme enclosing 'protuberances' from which emanate a pair of 'chain-links'. These hieroglyphs are also read as rebus-metonymy layers to represent a specific form of lapidary or metalwork: goṭī 'lump of silver' (Gujarati); goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ(Kashmiri). Thus, a collection of hieroglyphs are deployed as rebus-metonymy layered encryptions, to convey a message in Meluhha (mleccha) speech form.Hypertext: Pair of rings attached to string, pair of young bulls: dol 'likeness, picture, form' (Santali) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast iron' (Santali) dul ‘to cast metal in a mould’ (Santali) dul meṛeḍ cast iron (Mundari. Santali) కమ్మరు kammaru or కమరు kammaru. [Tel.] n. A girdle. మొలనూలు. కమ్మరము kammaramu kammaramu. [Tel.] n. Smith's work, iron work. కమ్మరవాడు, కమ్మరి or కమ్మరీడు kammara-vāḍu. n. An iron-smith or blacksmith. బైటికమ్మరవాడు an itinerant blacksmith. कर्मार karmāra m. an artisan , mechanic , artificer, a blacksmith &c ऋग्-वेद RV. x , 72 , 2 AV. iii , 5 , 6 VS. Mn. iv , 215 &c (Monier-Williams)

Thus, semantics of 'metalcasting' should be used to expand the meanings of associated hypertexts of 'young bull' or 'ring' hieroglyphs.

Hieroglyphs which compose the hypertext on m296 are vivid and unambiguous.

Hieroglyph: gö̃ṭh 1 अर्गलम्, चिन्हितग्रन्थिः f. (sg. dat. gö̃ṭhi गाँ&above;ठि), a bolt, door-chain; a method of tying up a parcel with a special knot marked or sealed so that it cannot be opened by an unauthorized person. Cf. gã̄ṭh and gö̃ṭhü. -- dyunu -- m.inf. to knot, fasten; to bolt, fasten (a door) (K.Pr. 76). *gōṭṭa ʻ something round ʼ. [Cf. guḍá -- 1. -- In sense ʻ fruit, kernel ʼ cert. ← Drav., cf. Tam. koṭṭai ʻ nut, kernel ʼ, Kan. goṟaṭe &c. listed DED 1722] K. goṭh f., dat. °ṭi f. ʻ chequer or chess or dice board ʼ; S. g̠oṭu m. ʻ large ball of tobacco ready for hookah ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; P. goṭ f. ʻ spool on which gold or silver wire is wound, piece on a chequer board ʼ; N. goṭo ʻ piece ʼ, goṭi ʻ chess piece ʼ; A. goṭ ʻ a fruit, whole piece ʼ, °ṭā ʻ globular, solid ʼ, guṭi ʻ small ball, seed, kernel ʼ; B. goṭā ʻ seed, bean, whole ʼ; Or. goṭā ʻ whole, undivided ʼ, goṭi ʻ small ball, cocoon ʼ, goṭāli ʻ small round piece of chalk ʼ; Bi. goṭā ʻ seed ʼ; Mth. goṭa ʻ numerative particle ʼ; H.goṭ f. ʻ piece (at chess &c.) ʼ; G. goṭ m. ʻ cloud of smoke ʼ, °ṭɔ m. ʻ kernel of coconut, nosegay ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ lump of silver, clot of blood ʼ, °ṭilɔ m. ʻ hard ball of cloth ʼ; M. goṭām. ʻ roundish stone ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ a marble ʼ, goṭuḷā ʻ spherical ʼ; Si. guṭiya ʻ lump, ball ʼ; -- prob. also P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ, H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ. Rebus: °ṭī f. ʻ lump of silver*gōḍḍ -- ʻ dig ʼ see *khōdd -- .Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271).Rebus: goṭī f. ʻ lump of silver (Gujarati).

Hieroglyph: Chain links: śã̄gal, śã̄gaḍ ʻchainʼ (WPah.) śr̥ṅkhala m.n. ʻ chain ʼ MārkP., °lā -- f. VarBr̥S., śr̥ṅkhalaka -- m. ʻ chain ʼ MW., ʻ chained camel ʼ Pāṇ. [Similar ending in

Ku.gng. śāṅaī ʻ intertwining of legs in wrestling ʼ (< śr̥ṅkhalita -- ); Or. sāṅkuḷibā ʻ to enchain ʼ.(CDIAL 12580, 12581)சங்கிலி¹ caṅkili , n. < šṛṅkhalaā. [M. caṅ- kala.] 1. Chain, link; தொடர். சங்கிலிபோ லீர்ப்புண்டு (சேதுபு. அகத். 12). 2. Land-measuring chain, Gunter's chain 22 yards long; அளவுச் சங்கிலி. (C. G .) 3. A superficial measure of dry land=3.64 acres; ஓர் நிலவளவு. (G. T n. D. I , 239). 4. A chain-ornament of gold, inset with diamonds; வயிரச்சங்கிலி என்னும் அணி. சங்கிலி நுண்டொடர் (சிலப். 6, 99). 5. Hand-cuffs, fetters; விலங்கு. Rebus: sangaha, sangraha, 'catalogue, list'. saṁgraha m. ʻ collection ʼ Mn., ʻ holding together ʼ MBh. [√grah ] Pa. saṅgaha -- m. ʻ collection ʼ, Pk. saṁgaha -- m.; Bi. sã̄gah ʻ building materials ʼ; Mth. sã̄gah ʻ the plough and all its appurtenances ʼ, Bhoj. har -- sã̄ga; H. sãgahā ʻ collection of materials (e.g. for building) ʼ; <-> Si. san̆gaha ʻ compilation ʼ ← Pa. *saṁgrahati ʻ collects ʼ see sáṁgr̥hṇāti. (CDIAL 12852). sáṁgr̥hṇāti ʻ seizes ʼ RV. 2. *saṁgrahati. 3. saṁgrāhayati ʻ causes to be taken hold of, causes to be comprehended ʼ BhP. [√grah ] 1. Pa. saṅgaṇhāti ʻ collects ʼ, Pk. saṁgiṇhaï; Or. saṅghenibā ʻ to take with, be accompanied by ʼ. 2. Pa. fut. saṅgahissati, pp. saṅgahita -- ; Pk. saṁgahaï ʻ collects, chooses, agrees to ʼ; Si. han̆ginavā ʻ to think ʼ, hän̆genavā, än̆g° ʻ to be convinced, perceive ʼ, han̆gavanavā, an̆g° ʻ to make known ʼ.

3. Or. saṅgāibā ʻ to keep ʼ.(CDIAL 12850)

Rebus: Vajra Sanghāta 'binding together': Mixture of 8 lead, 2 bell-metal, 1 iron rust constitute adamantine glue. (Allograph) Hieroglyph: sãghāṛɔ 'lathe'.(Gujarati)

Rebus: Vajra Sanghāta 'binding together': Mixture of 8 lead, 2 bell-metal, 1 iron rust constitute adamantine glue. (Allograph) Hieroglyph: sãghāṛɔ 'lathe'.(Gujarati)

Why nine leaves? lo = nine (Santali); no = nine (Bengali) on-patu = nine (Ta.) [Note the count of nine ‘ficus’ leaves depicted on the epigraph.]

lo, no ‘nine’ phonetic reinforcement of Hieroglyph: loa ‘ficus’ loa = a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata (Santali) Rebus: lo ‘copper’ (Samskritam) loha lut.i = iron utensils and implements (Santali) lauha = made of copper or iron (Gr.S’r.); metal, iron (Skt.); lo_haka_ra = coppersmith, ironsmith (Pali); lo_ha_ra = blacksmith (Pt.); lohal.a (Or.); lo_ha = metal, esp. copper or bronze (Pali); copper (VS.); loho, lo_ = metal, ore, iron (Si.) lo 'iron' (Assamese) loa ‘iron’ (Gypsy) lauha = made of copper or iron (Gr.S'r.); metal, iron (Skt.); lohakāra = coppersmith, ironsmith (Pali);lohāra = blacksmith (Pt.); lohal.a (Or.); loha = metal, esp. copper or

Interlocking bodies: ca_li (IL 3872); rebus: s’a_lika (IL) village of artisans. [cf. sala_yisu = joining of metal (Ka.)] सांगड sāṅgaḍa m f (संघट्ट S) f A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together.(Marathi). Seal m0296 is a सांगड sāṅgaḍa, 'a hypertext orthograph formed of two or more components linked together'. Rebus: sangraha, sangaha 'catalogue, list' Rebus also: sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati). jangadiyo 'military guards carrying treasure into the treasury' (Gujarati) The mercantile agents who were jangadiyo received goods on jangad 'entrusted for approval'. sangara'trade'.

kamaḍha = ficus religiosa (Skt.); kamar.kom ‘ficus’ (Santali) rebus: kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.); kampaṭṭam = mint (Ta.) Vikalpa: Fig leaf ‘loa’; rebus: loh ‘(copper) metal’. loha-kāra ‘metalsmith’ (Sanskrit). loa ’fig leaf; Rebus: loh ‘(copper) metal’ The unique ligatures on the 'leaf' hieroglyph may be explained as a professional designation: loha-kāra 'metalsmith'; kāruvu [Skt.] n. 'An artist, artificer. An agent'.(Telugu).

sãghāṛɔ 'lathe' is a signifier and the signified is: सं-घात sãghāta 'caravan consignment' [an assemblage, aggregate of metalwork objects (of the turner in workshop): metals, alloys]. sangāṭh संगाठ् । सामग्री m. (sg. dat. sangāṭas संगाटस्), a collection (of implements, tools, materials, for any object), apparatus, furniture, a collection of the things wanted on a journey, luggage, and so on. -- karun -- करुन् । सामग्रीसंग्रहः m.inf. to collect the ab. (L.V. 17).(Kashmiri).

Hieroglyph: one-horned young bull: खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. Rebus: कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi)

kot.iyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; kot. = neck (G.lex.) [cf. the orthography of rings on the neck of one-horned young bull]. ko_d.iya, ko_d.e = young bull; ko_d.elu = plump young bull; ko_d.e = a. male as in: ko_d.e du_d.a = bull calf; young, youthful (Te.lex.)

Glyph: ko_t.u = horns (Ta.) ko_r (obl. ko_t-, pl. ko_hk) horn of cattle or wild animals (Go.); ko_r (pl. ko_hk), ko_r.u (pl. ko_hku) horn (Go.); kogoo a horn (Go.); ko_ju (pl. ko_ska) horn, antler (Kui)(DEDR 2200). Homonyms: kohk (Go.), gopka_ = branches (Kui), kob = branch (Ko.) gorka, gohka spear (Go.) gorka (Go)(DEDR 2126).

kod. = place where artisans work (Gujarati) kod. = a cow-pen; a cattlepen; a byre (G.lex.) gor.a = a cow-shed; a cattleshed; gor.a orak = byre (Santali.lex.) got.ho [Skt. kos.t.ha the inner part] a warehouse; an earthen

Rebus: kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A. kundār, B. kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H. kũderā m. ‘one who works a lathe, one who scrapes’, rī f., kũdernā ‘to scrape, plane, round on a lathe’; kundakara—m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण [ kōndaṇa ] n (कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার [ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver. খোদকারি n. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work. খোদাই [ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving. খোদাই করা v. to engrave; to carve. খোদানো v. & n. en graving; carving. খোদিত [ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

A painted goblet with the 'three-branched fig tree' motif from Nausharo I D, transitional phase between the Early and Mature Harappan periods (c. 2600-2550 BCE) (After Samzun 1992: 250, fig.29.4 no.2)

A painted goblet with the 'three-branched fig tree' motif from Nausharo I D, transitional phase between the Early and Mature Harappan periods (c. 2600-2550 BCE) (After Samzun 1992: 250, fig.29.4 no.2)Zebu and nine leaves. In front of the standard device and the stylized tree of 9 leaves, are the black buck antelopes. Black paint on red ware of Kulli style. Mehi. Second-half of 3rd millennium BCE. [After G.L. Possehl, 1986, Kulli: an exploration of anancient civilization in South Asia, Centers of Civilization, I, Durham, NC: 46, fig. 18 (Mehi II.4.5), based on Stein 1931: pl. 30.

Semantic determinative: markhor: mẽḍhā 'markhor' rebus: medhā 'yajña, dhanam'; दु mṛdu, mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Santali.Mu.Ho.);med 'copper' (Slavic)

mēthí m. ʻ pillar in threshing floor to which oxen are fastened, prop for supporting carriage shafts ʼ AV., °thī -- f. KātyŚr.com., mēdhī -- f. Divyāv. 2. mēṭhī -- f. PañcavBr.com., mēḍhī -- , mēṭī -- f. BhP. 1. Pa. mēdhi -- f. ʻ post to tie cattle to, pillar, part of a stūpa ʼ; Pk. mēhi -- m. ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ, N. meh(e), miho, miyo, B. mei, Or. maï -- dāṇḍi, Bi. mẽh, mẽhā ʻ the post ʼ, (SMunger) mehā ʻ the bullock next the post ʼ, Mth. meh, mehā ʻ the post ʼ, (SBhagalpur) mīhã̄ ʻ the bullock next the post ʼ, (SETirhut) mẽhi bāṭi ʻ vessel with a projecting base ʼ.2. Pk. mēḍhi -- m. ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ, mēḍhaka<-> ʻ small stick ʼ; K. mīr, mīr