http://tinyurl.com/y2v4a7vs

--The Itihāsa of दशराज्ञ युद्ध Daśarājñá yuddha, Battle of Ten Kings dates R̥gveda, since the ancient text recalls the historical events and people engaged in a series of battles on the banks of River Paruṣṇī (Ravi) and contiguous regions.

This is an addendum to

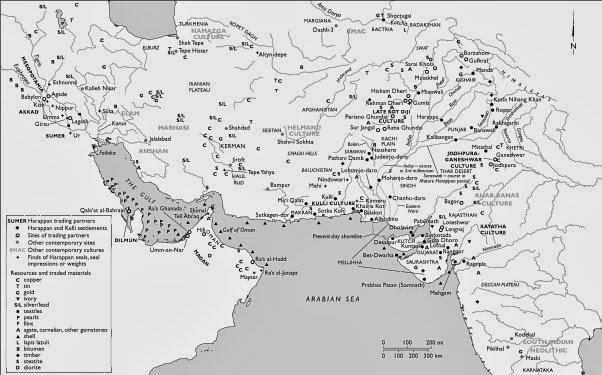

Archaeological, Indus Script evidence for Meluhha smiths, traders moving into Indo-European speaker areas of BMAC and Anau, Turkmenistan, ca. 2300 BCE http://tinyurl.com/y4h4qu3t

The battle finds mention in Avesta. "No one can compare the Avestan poetry with the Indian [Rigvedic] poetry in its content, in its style of expression, and in its entire coloring, without coming to the conclusion, on account of their agreement in small details which force themselves on us at every step, that both the literatures point not only to a common origin of these two peoples and their religions, but also to a community of Indo-Iranian religious poetry, developed in well-established forms." --[Hermann Oldenberg]

R̥gveda VII.18 andVII.83 refer to the following Anu conglomerate who opposed Sudas:

Shrikant Talageri notes that these names of the Anu conglomerate cover, in an almost continuous geographical belt, the entire sweep of areas extending westwards from the Punjab (the battleground of the dāśarājña battle) right up to southern and eastern Europe:

Clik here to view.![]()

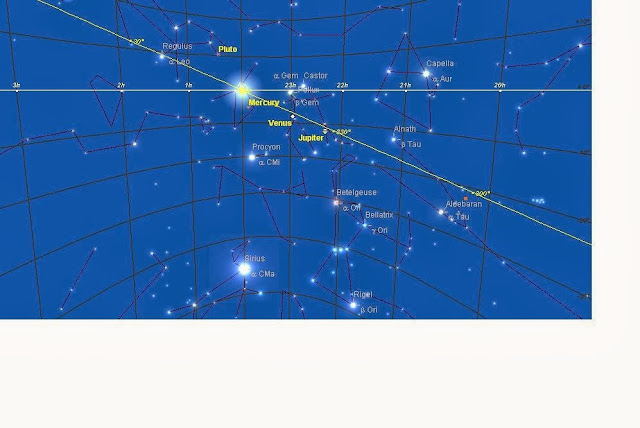

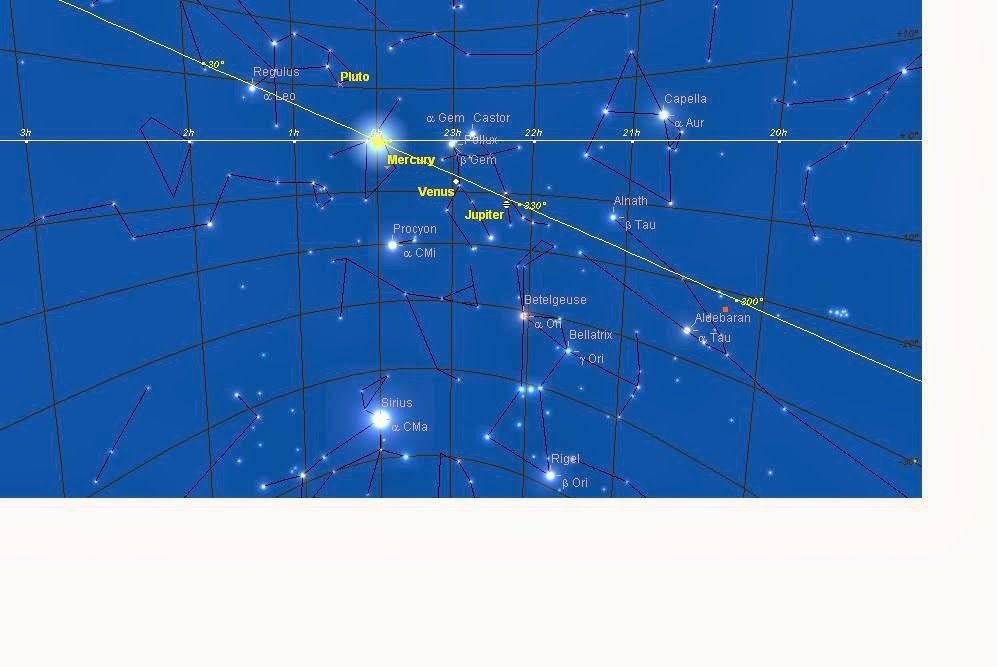

This monograph posits ca. 8th millennium BCE as the date of R̥gveda narratives related to people engaged in दशराज्ञ युद्ध Daśarājñá yuddha. The date is evidenced by archaeological settlement of Bhirrana and by astronomical skymaps derived from details provided in Veda texts on the legends of the ṛbhu as referring to the time when the year commenced with the autumnal equinox in Canis Major. Astronomically, the time is reckoned as 7240 BCE.

ऋभु may thus refer to a smith of 8th m. BCE, one who works in iron , a smith , builder (of carriages &c ), N. of three semi-divine beings (ऋभु , वाज , and विभ्वन् , the name of the first being applied to all of them ; thought by some to represent the three seasons of the year [Ludwig RV. vol.iii , p.187] , and celebrated for their skill as artists ; they are supposed to dwell in the solar sphere , and are the artists who formed the horses of इन्द्र , the carriage of the अश्विन्s , and the miraculous cow of बृहस्पति ; they made their parents young , and performed other wonderful works [Sv-apas] ; they are supposed to take their ease and remain idle for twelve days [the twelve intercalary days of the winter solstice] every year in the house of the Sun [Agohya] ; after which they recommence working ; when the gods heard of their skill , they sent अग्नि to them with the one cup of their rival त्वष्टृ , the artificer of the gods , bidding the ऋभुs construct four cups from it; when they had successfully executed this task , the gods received the ऋभुs amongst themselves and allowed them to partake of their sacrifices &c ; cf. Kaegi RV. p.53 f.) RV. AV. &c.

R̥gveda attests the locus of speakers of Indo-European dialects, including Mleccha (Meluhha) dialect which is the lingua franca of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization evidenced by over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions which are wealth-accounting metalwork ledgers/catalogues.

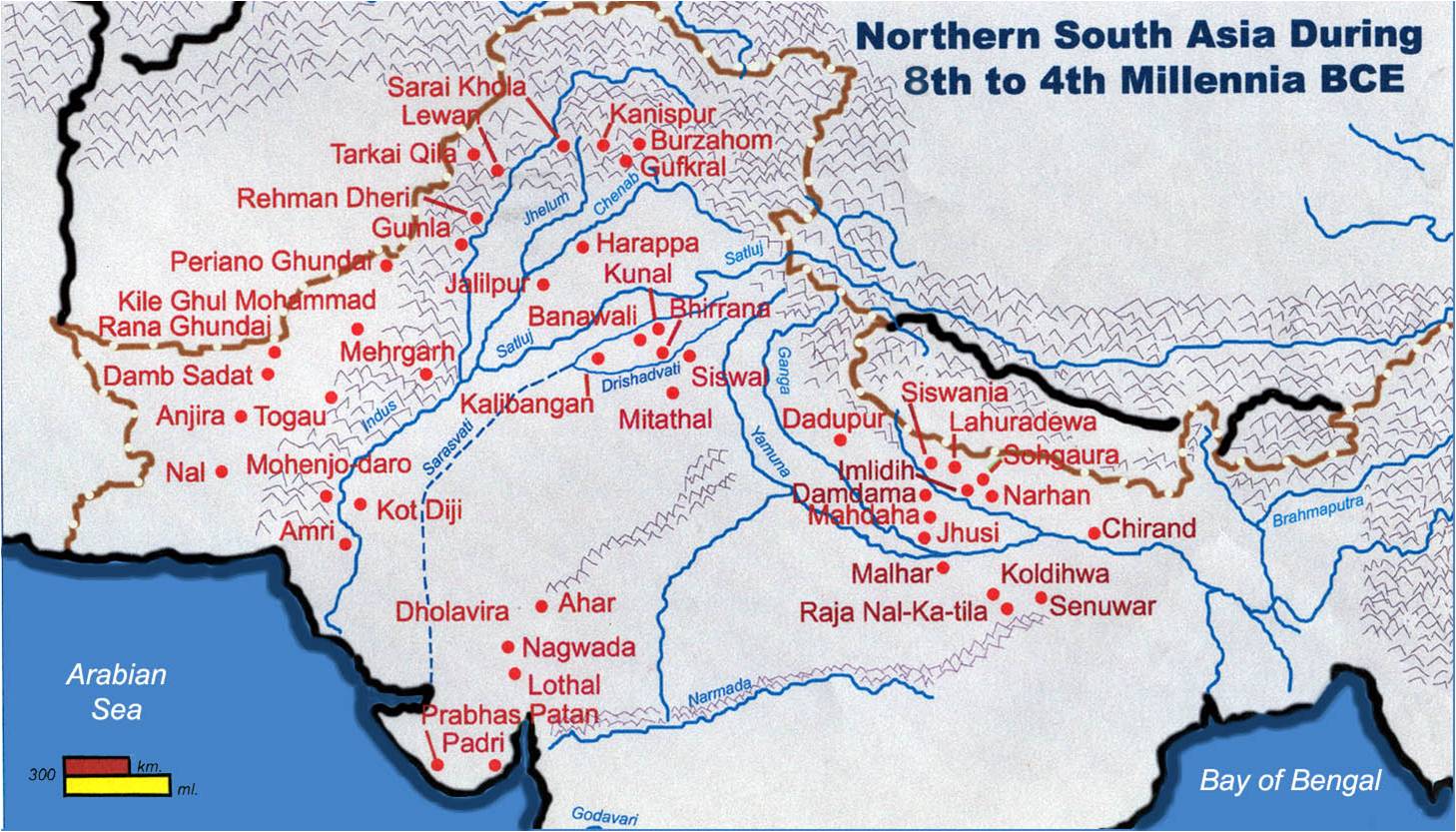

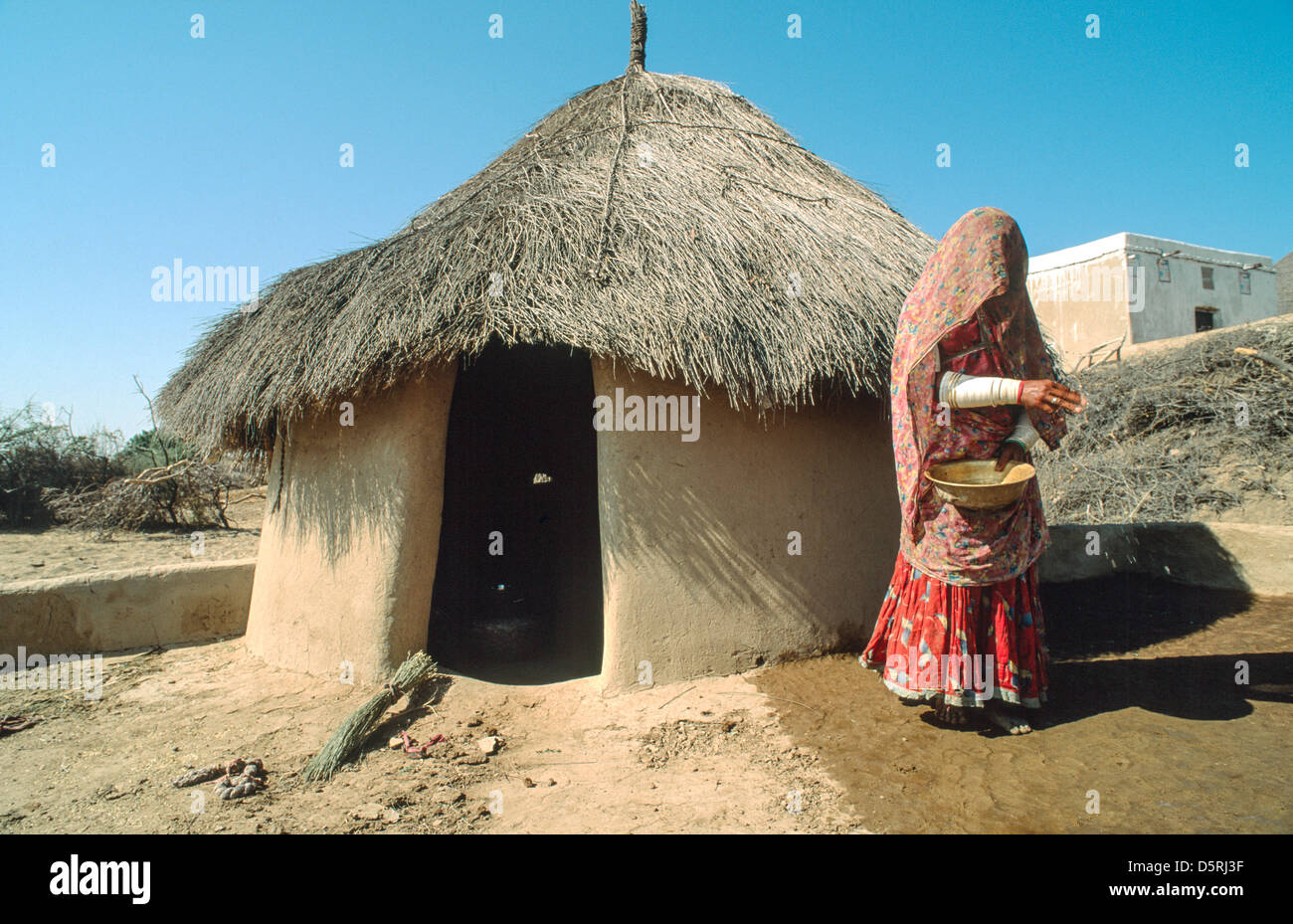

Burzahom, Farmana and Bhirrama sites of Sarasvati Civilization have yielded circular pit dwellings which are characteristic Vedic houses described in the texts.

Bhirrana, pronounced: Bhirḍānā 29°33′15″N 75°33′55″E is a settlement on the banks of River Sarasvati with continuos habitation from ca. 8th millennium BCE.

Bharata Kings of R̥gveda Pratardana, Sudas, Somaka, Sahadeva, Aśvamedha etc. are followed by Kuru Śaravaṇa, Devāpi and Śantanu. Mahābhārata historical narratives are a sequel to R̥gveda Śantanu. A Bharata king mentioned in Yajur Veda is King Dhr̥tarāṣṭra. The last Bharata king mentioned in Atharvaṇa Veda is Parīkṣit. antanu was a Kuru king of Hastinapura. He was a descendant of the Bharata race, of the Solar dynasty and great-grandfather of the Pandavas and Kauravas. He was the youngest son of King Pratipa of Hastinapura and had been born in the latter's old age. The eldest son Devapi had leprosy and gave up his inheritance to become a hermit. The middle son Bahlika (or Vahlika) abandoned his paternal kingdom and started living with his maternal uncle in Balkh and inherited his kingdom. Śantanu thus became the king of Hastinapura.

This narrative clearly links Bahlika and Sarasvati Civilization area as both inhabited by Meluhha (Proto_Indo-Aryan) speakers.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Circular Pit dwelling complex,Bhirrana.

http://asi.nic.in/asi_exca_2007_bhirrana.asp

--The Itihāsa of दशराज्ञ युद्ध Daśarājñá yuddha, Battle of Ten Kings dates R̥gveda, since the ancient text recalls the historical events and people engaged in a series of battles on the banks of River Paruṣṇī (Ravi) and contiguous regions.

This is an addendum to

Archaeological, Indus Script evidence for Meluhha smiths, traders moving into Indo-European speaker areas of BMAC and Anau, Turkmenistan, ca. 2300 BCE http://tinyurl.com/y4h4qu3t

Eleven kings of the Bharata dynasty are referred in the Rig Veda: Mudgala, Vadhryasva, Divodasa, Srnjaya, Pijavana, Sudasa, Sahadeva and Somaka belong to the Northern Panchala dynasty. As Sudas lived three generations after Sri Rama, the probable date which we can assign to Sudasa is 4107/3489 B.C.E.

https://ithihas.wordpress.com/2013/04/20/date-of-mahabharatha-war/R̥gveda VII.18 andVII.83 refer to the following Anu conglomerate who opposed Sudas:

VII.18.5 Śimyu.

VII.18.6 Bhṛgu.

VII.18.7 Paktha, Bhalāna, Alina, Śiva, Viṣāṇin.

VII.83.1 Parśu/Parśava, Pṛthu/Pārthava, Dāsa.

[Puranic Anus: Madra.]

Their exodus westwards is mentioned in RV. VII.5.3 and VII.6.3.

Shrikant Talageri notes that these names of the Anu conglomerate cover, in an almost continuous geographical belt, the entire sweep of areas extending westwards from the Punjab (the battleground of the dāśarājña battle) right up to southern and eastern Europe:

(Avestan) Afghanistan: Proto-Iranian: Sairima (Śimyu), Dahi (Dāsa).

NE Afghanistan: Proto-Iranian: Nuristani/Piśācin (Viṣāṇin).

Pakhtoonistan (NW Pakistan), South Afghanistan: Iranian: Pakhtoon/Pashtu (Paktha).

Baluchistan (SW Pakistan), SE Iran: Iranian: Bolan/Baluchi (Bhalāna).

NE Iran: Iranian: Parthian/Parthava (Pṛthu/Pārthava).

SW Iran: Iranian: Parsua/Persian (Parśu/Parśava).

NW Iran: Iranian: Madai/Mede (Madra).

Uzbekistan: Iranian: Khiva/Khwarezmian (Śiva).

W. Turkmenistan: Iranian: Dahae (Dāsa).

Ukraine, S, Russia: Iranian: Alan (Alina), Sarmatian (Śimyu).

Turkey: Thraco-Phrygian/Armenian: Phryge/Phrygian (Bhṛgu).

Romania, Bulgaria: Thraco-Phrygian/Armenian: Dacian (Dāsa).

Greece: Greek: Hellene (Alina).

Albania: Albanian: Sirmio (Śimyu). "Further:a) The leader of the enemy alliance is Kavi Cāyamāna: Kauui is an Iranian (Avestan) name. b) The priest of the enemy alliance is Kavaṣa: Kaoša is an Iranian (Avestan) name.c) Kavi Cāyamāna of the battle hymn was a descendant of Abhyāvartin Cāyamāna, who is described in the Rigveda (VI.27.8) as a Pārthava. The later Iranian (Avestan) dynasty (after the Iranians migrated westwards from the Rigvedic Greater Punjab into Afghanistan, and composed the Avesta), the oldest Iranian dynasty in historical record (outside the Rigveda) to which belongedZarathushtra's patron king and foremost disciple Vištāspa, is theKavyān (Pahlavi Kayanian) dynasty descended from this sameKavi/Kauui. In later historical times, it is the Parthians (Parthava) who maintained a strong tradition that the kings of the Kavyān dynasty of the Avesta belonged to their tribe."

Arguments advanced by Shrikant Talageri: "The Rigvedic people were in northwestern India from before 3000 BCE.As per all the linguistic evidence accepted by a general consensus among linguists, this was a point of time when all the 12 branches of Indo-European languages were still together in contiguous areas in and around the Original Indo-European Homeland. In short: the Original Indo-European Homeland was in India, and the Harappan Civilization (in linguistic terms) was an "Indo-Iranian" Civilization."

The conflict between Vedic Aryans and Iranians (Indian Journal of History and Culture, Chennai, Autumn 2015) -- Koenraad Elst (2016)"Sudās, the Tṛtsu, defeats the Pauravas’ western neighbor among the five tribes, the Ānavas: “The goods of Anu’s son he gave to Tṛtsu.” (RV 7:18:13) In the next verse, the Ānavas are mentioned again, together with what remained of the Druhyutribe, as having been “put to sleep”. The enemies include Kaviand Kavaṣa, the enemy tribes Pṛśu, Pṛthu, Paktha, Bhalana(RV 7:18:7) are collectively known as Dāsa, some of them asPaṇi (lambasted already in 7:6:3), and their priests as Dasyu. Practically all the names of enemy tribes or enemy leaders are Iranian or pertain to tribes known from Greco-Roman sources as Iranian: Kavi, the name of the Iranian dynasty still featuring in Zarathuštra’s Gāthās (e.g. Gāthā 51:16, Insler 1975:107); Kavaśa/Kaoša; Dāsa/Dahae; Dasyu/

Danghyu; Paṇi/Parnoi;Ānava/Anaoi; Parśu/Persoi; Pṛthu/Parthoi; Paktha/Paštu;Bhalāna/Baluc/Bolān...Dāsas and Dasyus were “people and cultures either indigenous to South Asia or already in South Asia – from wherever or whenever they may have come – when the carriers of Rgvedic culture and religion moved into and through the northwest of the subcontinent” (Jamison & Brereton 2014:56). The thrust of Sudās’s Vedic Aryans was towards “the region to the east (…), the Gaṅgā-Yamunā Doab to which the Bharatas advanced (…) In this country of the Dāsas and Asuras”. (Pradhan 2014:188)...the source text says it is theDāsas and Dasyus who came from the west. It says that they have come to the “east” for a fight and that these “godless ones” are turned back “westward” (7:6:3); and it has them come from the westerly Asiknī/Chenab river valley to challenge and fight Sudās on the shores of the easterly Paruṣṇī/Ravi...The heroes of this hymn, the Tṛtsus (a clan around seven successive kings belonging to the broader Bhārata dynasty, including Sudās), are Āryas and supported by Indra. The enemy camp as a whole is deemed anindra, “without Indra” (7:18:16), in a verse that seems to furnish the first instance of this term. Later books use this as a standard allegation of the enemies: “Indra-less destructive spirit” (RV 4:23.7), “how can those without Indra and without hymns harm me?” (RV 5:2:3), “enemies without Indra”, truth-haters (RV 1:133:1), “my enemies without Indra” (RV 10:48:7), “Indra-less libation-drinkers” (RV 10:27:6, according to Geldner 2003/3:166, a “reminiscence of 7:18:16”). Included in the enemy camp are the Dasyus, described as “faithless, rudely-speaking Paṇis/niggards, without belief, sacrifice or worship” (RV 7:6:3). Other seers call them “without sacrifice” (RV 1:33:4, 8:70:11), “without oath” (RV 1:51:8, 1:175:3, 6:14:3, 9:41:2), “riteless” (RV 10:22:8), “godless” (adeva, RV 8:70:11), “faithless” (RV 1.33.9, 2:22:10), “prayerless” (RV 4:16:9), “following different rites” (RV 8:70:11, 10:22:8).All these are properties pertaining to religion. Dasyus are the Dāsas’ priests and the special target ofVasiṣṭha’s ire. In fact, opposition to the Dasyus is a general Vedic trait: “Dasyus never figure as rich or powerful enemies. They are depicted as sly enemies who incite others into acts of boldness (6:24:8)...Who the enemies were not None of the names or nicknames associated with the Ten Kings, their tribes or their religion is attested in Dravidian, Munda, Burushaski, Kusunda, Nahali, Tibetan or any other nearby language. Most of them, by contrast, are completely transparent as Iranian names. Similarly, their stated religious identification points to the Mazdean tradition...The first reason is that those targeted by Vasiṣṭha aremṛdhravāc (RV 7:6:3), “babblers defective in speech” (Wilson), “rudely-speaking” (Griffith), “wrongly speaking” (“misredend”, Geldner), or “of disdainful words” (Jamison and Brereton). This is not normally said of people speaking a foreign language, but of people who are comprehensible yet don’t use the accent or the sociolinguistic register we are used to. ..The Vārṣāgira battle

A few generations later, another battle pitted the same tribes against each other. The centre of Ānava culture had by then decisely shifted from Panjab to Afghanistan, and the confrontation took place on the then borderline between Vedic-Indian and Afghan-Iranian territory, beyond the Sarayu river (RV 4:30:18) near the Bolan pass in southern Afghanistan. The battle was very briefly sung esp. in RV 1:100, but may be alluded to elsewhere. It features Ṛjāśva the Vārṣāgira, i.e. “descendent of Vṛṣāgir” (RV 1:100:16-17), with Sahadeva(descendant of Sudās and father of Somaka) and three others, as defeating “Dasyus and Śimyus”. The Śimyus are one of the enemy tribes in the Battle of the Ten Kings, the Dasyus are the priests of the enemy camp.The result of this “victory” is that the kings of both sides survive the battle (as we shall see), that the division of territory remains the same, and that the chroniclers of both sides can give their own versions to claim victory. So, with the benefit of hindsight, the war in this case seems to have been pointless. In the Vedic account, it does indeed conclude the period of conflict. Bhārata expansionism into Afghanistan seems to have been overstretched, and subsequent generations left it to the Iranians: “Good fences make good neighbours.” This way, the battle ushers in a period of peaceful coexistence forming the setting of books 2, 5 and 8...The Avestan version of the same battle first of all exists. That means there are two accounts of one event. It makesZarathuštra’s patron Vištāspa (mentioned by Zarathuštra himself as his friend, follower and champion) fight against“Arjāsp” or “Arejataspa”, meaning the Vedic king Ṛjāśva., as well as against Hazadaēva > Hušdiv and Humayaka, meaning Vedic Sahadeva and his son Somaka. This is related in the Ābān Yašt, Yt.5.109, 5.113, 9.130, in which Vištāspa prays for strength to crush the Daēva-worshippers including Arejatāspa; and much later in the medieval epic Šāh Namah, esp. ch.462. (Talageri 2000:214-224, elaborating on Hodiwala 1913) In the Avestan version, the Iranians are victorious in the end...A related Vedic hymn could be read as mentioning kingVištāspa: “kimiṣṭāśva iṣṭaraśmireta īśānāsastaruṣa ṛñjate nṝ na” (RV.I.122.13). Wilson, like the medieval commentatorSāyana, identifies it as a name: “What can Iṣṭāśva, (what can)Iṣṭaraśmi, (what can) those who are now lords of the earth, achieve (with respect) to the leaders of men, the conquerors of their foes?” Similarly, translator Geldner: “Werden Iṣṭāśva,Iṣṭaraśmi, diese siegreichen Machthaber, die Herren auszeichnen?” (“Will Iṣṭāśva, Iṣṭaraśmi, these victorious sovereigns, honour the lords?”)...Consequences for the age of Zarathuštra

Since the classical Greeks already, it has been common to dateZarathuštra to the 6th century BC, hardly a few generations before the Persian wars. In popular literature, this date is still given, but scholars have now settled for an earlier date: “The archaism of the Gāthās would incline us to situate Zarathuštrain the very beginning of the first millennium BCE, if not even earlier.” (Varenne 2006:43) But how much earlier? According to leading scholar SkjaervØ (2011:350), “Zoroastrianism (…) originated some four millennia ago”.

Well, we bet on an even earlier date. If Zarathuštra was contemporaneous with the Vārṣāgira battle, and at any rate with the Ṛg-Veda, he must have lived either in ca. 1400 according to the Aryan Invasion Theory (AIT), or earlier. The fact that the Vedic people had the Iranians as their western neighbours and fought with them, does not by itself prove anything about the homeland of their language family, and is in itself compatible with the AIT. But for other reasons, the AIT has been argued to be wrong (Kazanas 2015:268, Talageri 2000 and 2008), and if we go by the Out-of-India scenario, the events from the Ṛg-Veda’ Family Books are lifted back into the third millennium.

Independent of the relation with Vedic history, the Avestā itself gives more reasons for Zarathuštra’s ancientness, though not dated with precision. The first chapter of the Vendidād, discussed in Gnoli 1985:24-30, lists sixteen countries fit for Iranian habitation: most are parts of Afghanistan or due north of it (but not towards the Aral Lake, as the Aryan Invasion Theory would make you expect, nor the more westerly historical habitats of the Medes, Persians and Scythians), two are parts of Northwest India. These are Hapta Hendū, the “Land of Seven Rivers”, roughly Panjab; and Airiiānām Vaējo (the “Seed of the Aryans”), the first habitat after the Ānava ethnogenesis, which is Kaśmīr: “Given its very Oriental horizon, this list must be pre-Achaemenid; on the other hand, the remarkable extendedness of the territories concerned recommends situating them in a period much later than the Zoroastrian origins. (…) one or several centuries later than Zarathuštra’s preaching.” (Gnoli 1985:25) "

Bibliography

Avesta, the Sacred Scripture of the Parsees, Vaidika Samsodhana Mandala, Bombay 1962.

Bhargava, P.L., 1971 (1956): India in the Vedic Age, Lucknow: Upper India Publishing House.

--: 1998 (1984): Retrieval of History from Puranic Myths, Delhi: D.K. Printworld.

Elizarenkova, J., 1995: Language and Style of the Vedic Ṛṣis, Albany: SUNY.

Elst, Koenraad, 2013: “The Indo-European, Vedic and post-Vedic meanings of Ārya”, Vedic Venues 2, p.57-77, Kolkata:Kothari Charity Trust.

Fortson, Benjamin, 2004: Indo-European Language and Culture. An Introduction, Oxford: Blackwell.

Geldner, Karl Friedrich, 2003 (1951): Der Rigveda (1-2-3, in one volume), Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Gnoli, Gherarda, 1985: De Zoroastre à Mani, Paris, Institut d’Etudes Iraniennes, Sorbonne.

Griffith, Ralph, 1991 (1): The Ṛgveda, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Hale, Wash Edward, 1986: Asura in Early Vedic Religion, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

Hock, Hans Heinrich, 1999: “Through a glass darkly: modern ‘racial’ interpretations vs. textual and general prehistoric evidence on ārya and dāsa/dasyu in Vedic society”, p.145-174 in Bronkhorst, Johannes, and Deshpande, Madhav, eds. 1999:Aryan and Non-Aryan in South Asia. Evidence, Interpretation and Ideology, Cambridge MA: Harvard.

Hodiwala, Shapurji Kavasji, 1913: Zarathushtra and His Contemporaries in the Rigveda, Bombay: Hodiwala.

Hume, Robert Ernest, 1977 (1921): The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford: OUP.

Insler, S., 1975: The Gāthās of Zarathustra, in Acta Iranica, series 3, vol.1, Teheran-Liège: Bibliothèque Pahlavi.

Jamison, Stephanie, and Brereton, Joel, 2014: The Rigveda. The Earliest Religious Poetry of India, Oxford/New York: OUP.

Kazanas, Nicholas, 2015: Vedic and Indo-European Studies, Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

Krishna, Nanditha, 2014 (2007): The Book of Demons. Including a Dictionary of Demons in Sanskrit Literature, Delhi: Penguin.

Martínez, Javier, and de Vaan, Michiel, 2014: Introduction to Avestan, Leiden: Brill.

Molé, Marijan, 1993: La Légende de Zoroastre selon les Textes Pehlevis, Paris: Peeters.

Nagar, Shantilal, 2012: Biographical Dictionary of Ancient Indian Rishis, Delhi: Akshaya Prakashan.

Oldenberg, Hermann, 1894: Die Religion des Veda, Berlin, W. Hertz.

Pargiter, F.E., 1962: Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Pusalker, A.D., 1996 (1951): The Vedic Age, vol.1. of Majumdar, R.C., ed.: The History and Culture of the Indian People, Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

Schwartz, Martin, 2006: “How Zarathuštra generated the Gathic corpus”, Bulletin of the Asia Institute 16, .53-64.

Siddhantashastree, R., 1978: History of the Pre-Kali-Yuga India, Delhi: Inter-India Publications.

SkjaervØ, Prods Oktor, 2011: “Zarathustra: a Revolutionary Monotheist?”, p. 317-350, in Pongratz-Leisten, Beate 2011:Reconsidering the Concept of Revolutionary Monotheism, Winona Lake IN: Eisenbrauns.

Talageri, Shrikant, 2000: The Rigveda, an Historical Analysis, Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

--, 2008: The Rigveda and the Avesta, the Final Analysis, Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

Varenne, Jean, 2006: Zoroastre, le Prophète de l’Iran, Paris: Dervy, Paris.

Verma, H.N., and Verma, Amrit, 1994: Decisive Battles of India, Campbell CA: GIP Books.

Wilson, H.H., 1997 (1860): Ṛg-Veda-Saṁhitā, Delhi: Parimal Publications..

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

This monograph posits ca. 8th millennium BCE as the date of R̥gveda narratives related to people engaged in दशराज्ञ युद्ध Daśarājñá yuddha. The date is evidenced by archaeological settlement of Bhirrana and by astronomical skymaps derived from details provided in Veda texts on the legends of the ṛbhu as referring to the time when the year commenced with the autumnal equinox in Canis Major. Astronomically, the time is reckoned as 7240 BCE.

ऋभु may thus refer to a smith of 8th m. BCE, one who works in iron , a smith , builder (of carriages &c ), N. of three semi-divine beings (ऋभु , वाज , and विभ्वन् , the name of the first being applied to all of them ; thought by some to represent the three seasons of the year [Ludwig RV. vol.iii , p.187] , and celebrated for their skill as artists ; they are supposed to dwell in the solar sphere , and are the artists who formed the horses of इन्द्र , the carriage of the अश्विन्s , and the miraculous cow of बृहस्पति ; they made their parents young , and performed other wonderful works [Sv-apas] ; they are supposed to take their ease and remain idle for twelve days [the twelve intercalary days of the winter solstice] every year in the house of the Sun [Agohya] ; after which they recommence working ; when the gods heard of their skill , they sent अग्नि to them with the one cup of their rival त्वष्टृ , the artificer of the gods , bidding the ऋभुs construct four cups from it; when they had successfully executed this task , the gods received the ऋभुs amongst themselves and allowed them to partake of their sacrifices &c ; cf. Kaegi RV. p.53 f.) RV. AV. &c.

The following sky chart in figure 9 shows the occurrence of autumnal equinox at canis major, in 7240 BCE in reference to ṛbhu legends interpreted from R̥gveda metaphors.Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

R̥gveda attests the locus of speakers of Indo-European dialects, including Mleccha (Meluhha) dialect which is the lingua franca of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization evidenced by over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions which are wealth-accounting metalwork ledgers/catalogues.

Burzahom, Farmana and Bhirrama sites of Sarasvati Civilization have yielded circular pit dwellings which are characteristic Vedic houses described in the texts.

Bhirrana, pronounced: Bhirḍānā 29°33′15″N 75°33′55″E is a settlement on the banks of River Sarasvati with continuos habitation from ca. 8th millennium BCE.

Hariyūpiya is an expression composed of two words:

1. हरि mfn. (for 2. » col.3) bearing , carrying (» दृति and नाथ-ह्°)

2. यूप m. (prob. fr. √ युप् ; but according to Un2. iii , 27 , fr. √2. यु) a post , beam , pillar , (esp.) a smooth post or stake; 21 of these posts are set up , 6 made of बिल्व , 6 of खदिर , 6 of पलाश , one of उडुम्बर , one of श्लेष्मातक , and one of देव-दारु) RV. &c; a column erected in honour of victory , a trophy (= जय-स्तम्भ) L.; N. of a partic. conjunction of the class आकृति-योग (i.e. when all the planets are situated in the 1st , 2nd , 3rd and 4th houses) (वराह-मिहिर 's बृहत्-संहिता)

Together, the expression Hariyūpiya refers to a lcoation which carries यूप yūpa, 'stakes used to proclaim yajña-s.

RV 6.27.5 is explained in Sāyaṇa's commentary: Favouring Abhya_vartin, the son of Ca_yama_na, Indra destroyed the varas'ikha (people), killng the descendants of Vr.ci_vat, (who were stationed) on the Hariyu_pi_ya, on the eastern part, while the western (troop) was scattered through fear. [Abhya_vartin, Ca_yama_na: names of ra_ja_s. Vr.ci_vat is the first-born of the sons of varas'ikha, thereafter others are named. Hariyūpiya is the name of either a river or a city].

A number of R̥gveda people are mentioned and the ākhyāna narrative records the exploits of Indra at this river or city called Hariyūpiya where he smote the vanguard of the Vr̥cīvan-s. The exploits are also associated with cāyamāna and abhyāvartin as names of kings involved in the battles.

अभ्य्-ावर्तिन् m. N. of a king (son of चायमान and descendant of पृथु) RV. vi , 27 , 5 and 8. "Chinese scholar Hiuen Tsang (c. 640 AD) records the existence of the town Pehowa, named after Prithu, "who is said to be the first person that obtained the title Raja(king)". Another place associated with Prithu is Prithudaka (lit. "Prithu's pool"), a town on banks of Sarasvati river, where Prithu is believed to have performed the Shraddhaof his father. The town is referred as the boundary between Northern and central India and referred to by Patanjali as the modern Pehowa." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prithu

We do not know if this is a recollection of parts of or related to the Battle of the Ten Kings (dāśarājñá) alluded to in the R̥gveda (Book 7, hymns 18, 33 and 83.4-8). The significant fact is that the battles occured on the banks of Ravi River in the Punjab.

Is it a coincidence that Harappa is located on the banks of Ravi River? "Harappa (Urdu/Punjabi: ہڑپّہ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about 24 km (15 mi) west of Sahiwal. The site takes its name from a modern village located near the former course of the Ravi River (Part of Panjnad, five rivers) which now runs 8 km (5.0 mi) in north. The current village of Harappa is 6 km (3.7 mi) from the ancient site. Although modern Harappa has a legacy railway station from the period of the British Raj, it is today just a small crossroads town of population 15,000." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa

The location of Harappa in relation to some other archaeological sites of Sarasvati Civilization may be seen on the present-day map.

Translation (Sāyaṇa/Wilson):

6.027.01 What has Indra done in the exhilaration of this (Soma)? What has he done on quaffing this (libation)? What has he done in friendship for this (Soma)? What have former, what have recent adorers obtained from you in the chamber of this (libation)? [The r.s.i is expressing his impatience at the dealing of the reward of his praises; in the next stanza, he recants].

6.027.02 Verily, in the exhilaration of this (Soma) Indra has done a good deed; on quaffing the libation (he has done) a good deed; (he has done) a good deed in friendship for this Soma; former as well as recent adorers have obtained good of you in the chamber (of the libation).

6.027.03 We acknowledge no one, Maghavan, of greatness equal to yours, nor one of like affluence, nor one of equally glorifiable riches, none has (such as) your power been ever seen (in any other).

6.027.04 Such as your power (is) it has been comprehended (by us) as that wherewith you have slain the race of Varas'ikha, when the boldest (of them) was demolished by the noise of your thunderbolt hurled with (all your) force. [varas'ikha: name of an asura; or, perhaps, the name of a people].

6.027.05 Favouring Abhya_vartin, the son of Ca_yama_na, Indra destroyed the varas'ikha (people), killng the descendants of Vr.ci_vat, (who were stationed) on the Hariyu_pi_ya, on the eastern part, while the western (troop) was scattered through fear. [Abhya_vartin, Ca_yama_na: names of ra_ja_s. Vr.ci_vat is the first-born of the sons of varas'ikha, thereafter others are named. Hariyu_pi_ya is the name of either a river or a city].

6.027.06 Indra, the invoked of many, thirty hundred mailed warriors (were collected) together on the Yavya_vati_, to acquire glory, but the Vr.ci_vats advancing in a hostile manner, and breaking the sacrificial vessels, went to (their own) annihilation. [Thirty hundred: trim.s'ac chatam varmin.ah = trim.s'ada dhikas'atam, one hundred and thirty; kavacabhr.tas, wearers of breasplates or armour; yavya_vati_ = same as hariyu_pi_ya].

6.027.07 He whose bright prancing horses, delighted with choice fodder, proceed between (heaven and earth), gave up Turvas'a to Sr.n~jaya, subjecting the Vr.ci_vats to the descendant of Devava_ta (Abhya_vartin). [Sr.n~jaya: there are several princes with this name in the pura_n.as; one of them, the son of Haryas'va, was one of the five Pa_n~ca_la princes; the name is also that of a people, probably in the same direction, the northwest of India, or towards the Punjab (Vis.n.u Pura_n.a)].

6.027.08 The opulent supreme sovereign Abhya_vartin, the son of Ca_yama_na, presents, Agni, to me two damsels riding in cars, and twenty cows; this donation of the descendant of Pr.thu cannot be destroyed. [Two damsels: dvaya_n rathino vim.s'ati ga_ vadhu_mantah = rathasahita_n vadhu_matah stri_yukta_n dvaya_n mithunabhu_ta_n, being in pairs, having women together with cars; twenty animals, pas'u_n; perhaps, the gift comprised of twenty pairs of oxen yoked two and two in chariots; the gift of females to saintly persons; this donation: du_n.a_s'eyam daks.in.a_ pa_rthava_na_m = na_s'ayitum as'akya_; pa_rthava: Abhya_vartin, as descended from Pr.thu, the plural is used honorifically].

Bharata Kings of R̥gveda Pratardana, Sudas, Somaka, Sahadeva, Aśvamedha etc. are followed by Kuru Śaravaṇa, Devāpi and Śantanu. Mahābhārata historical narratives are a sequel to R̥gveda Śantanu. A Bharata king mentioned in Yajur Veda is King Dhr̥tarāṣṭra. The last Bharata king mentioned in Atharvaṇa Veda is Parīkṣit. antanu was a Kuru king of Hastinapura. He was a descendant of the Bharata race, of the Solar dynasty and great-grandfather of the Pandavas and Kauravas. He was the youngest son of King Pratipa of Hastinapura and had been born in the latter's old age. The eldest son Devapi had leprosy and gave up his inheritance to become a hermit. The middle son Bahlika (or Vahlika) abandoned his paternal kingdom and started living with his maternal uncle in Balkh and inherited his kingdom. Śantanu thus became the king of Hastinapura.

This narrative clearly links Bahlika and Sarasvati Civilization area as both inhabited by Meluhha (Proto_Indo-Aryan) speakers.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Circular Pit dwelling complex,Bhirrana.

ca. 8th millennium BCE. "Excavations by the ASI at Bhirrana (290 33’ N; 750 33’ E), (on the left bank of River Ghaggar), district Fatehabad, Haryana since 2003, has revealed a 4.5 m cultural sequence consisting of Hakra Ware, Early and Mature Harappan cultures. A transitional phase in between the Early and Mature Harappan cultures is also noticed. The earliest period, of the Hakra Ware culture, consisted of sub-terranean circular pit dwellings cut into the natural soil. These pit dwelling are noticed to the north of the Harappan town, and below the Early Harappan structures of the town. The Mature Harappan town consisted of a fortified settlement with two major divisions. The cultural remains consists of pottery repertoire of different kinds, antiquities of copper, faience, steatite, shell, semi-precious stones like agate, carnelian, chalcedony, jasper, lapis lazuli, and terracotta." |

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Structural evidence from Harappan site of Farmana]()

Circular dwelling houses at Farmana See:

Clik here to view.![Image result for vedic house louis renou]() Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Related image]() Vedic house.

Vedic house.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Bhirrana dancing girl on a potsherd is Indus Script hypertext.

Hieroglyph: meḍ 'to dance' (F.)[reduplicated from me-]; me id. (M.) in Remo (Munda)(Source: D. Stampe's Munda etyma) meṭṭu to tread, trample, crush under foot, tread or place the foot upon (Te.); meṭṭu step (Ga.); mettunga steps (Ga.). maṭye to trample, tread (Malt.)(DEDR 5057)

Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Mundari. Remo.) karaṇa 'dance posture' rebus:karaṇa 'scribe'.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Bhirrana Indus Script seals

Bhirrana Indus Script seals

http://www.frontline.in/navigation/?type=static&page=flonnet&rdurl=fl2502/stories/20080201504012900.htm

Apart from Trtsu Puru (Bharata) named in RV 7.33, the belligerents in the battle are: Ten listed as Turvasa, Yaksu (pun for Yadu), Matsya, Bhrgu, Druhyu, Paktha, Bhalana, Alina, Shiva and Visanin Other belligerents are Anava (Anu)(RV 7.18.14), the Aja and Sigru (RV 7.18.19) and the "21 men of both Vaikarna tribes" (RV 7.18.11) without a king, and individual kings Bheda (7.18.19, also mentioned RVv 7.33.3 and RV 7.83.4, the main leader slain by Sudas), Shimyu (RV 7.18.5), and Kavasa (RV 7.18.12). Puru, Parśu and Pani are also belligerents.

In one battle on the banks of Ravi river, the kings of Anu and Druhyu kingdoms were drowned.

Reasons/causes for the dāśarājñá, battle of ten kings

Turvasas and Yaksus (Yadu), together with the Matsya people (punned upon by the R̥ṣi by comparing them to hungry fish (matsya) flocking together) appear and ally themselves with the Bhr̥gu:and the Druhyu.

What was the objective of the battle? In my view, the battlefield in the Ravi riverbasin and the key cause for the battle is provided by the metaphor of 'hungry fish' used in RV VII.18.6:

"Eager for spoil was Turvasa Purodas, fain to win wealth, like fishes urged by hunger.

The Bhrgus and the Druhyus quickly listened: friend rescued friend mid the two distant peoples." (Griffith translation)

Sayana/Wilson translate the r̥ca focussing on Turvaśa's mission to acquire wealth: Turvas'a, who was presiding (at solemn rites), diligent in sacrifice, (went to Suda_sa) for wealth; but like fishes restricted (to the element of water), the Bhrigus and Druhyus quickly assailed them; of these two everywhere going the friend (of Suda_sa, Indra) rescued his friend.

रयि m. or (rarely) f. (fr. √ रा ; the following forms occur in the वेद , रयिस् , °य्/इम् , °यिभिस् , °यीणाम् ; रय्य्/आ,°य्य्/ऐ,°य्य्/आम् ; cf. 2. रै) , property , goods , possessions , treasure , wealth (often personified) RV. AV. VS. Br. S3rS. ChUp.

This comparison of Matsya people with 'hungry fish' means, that there were rivalries among the people about the use of water from the rivers for their livelihoods (hence, the signifier of hungry fish) and about the impediments caused to acquire wealth.

The pun on the word matsya, 'fish' is also a reference to the name of peoples called matsya. Matsya is one of the 16 janapada-s. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matsya_Kingdom This may explain the reason why the battle was joined by ten kings since a large number of people from the region of North India were concerned about their livelihood, searching for avenues to acquire wealth.

Another interpretation is possible. The fish is an Indus Script hypertext. It signifies aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'. The metaphor 'hungry fish' may thus be a refererence to the belligerents desirous of acquiring and possessing wealth derived from metalwork.

दशराज्ञ युद्ध Daśarājñá yuddha, Battle of Ten Kings is referred to in R̥gveda (Maṇḍala 7, hymns 18, 33 and 83.4–8), (Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, p.1). K. F. Geldner in his 1951 translation of the Rigveda considers the hymns as "obviously based on an historical event". [Geldner, Karl Friedrich, Der Rig-Veda: Aus dem Sanskrit ins Deutsche übersetzt Harvard Oriental Studies, vols. 33, 34, 35 (1951), reprint Harvard University Press (2003)] Further elaboration in Schmidt, H.P. Notes on Rgveda 7.18.5–10. Indica. Organ of the Heras Institute, Bombay. Vol.17, 1980, 41–47.

pancajana, pancakrishtya or pancamanusha are five sons of Yayati: तुर्वश,

Turvaśa, lived southeast of the Sarasvati river region; the other four are Yadu, Druhyu, Anu and Puru. Yadu and Turvaśa were born to Devayani, and the other three were born to Śarmiṣṭha. Cholas, Pandyas, Cheras have descended from Turvaśa, (Asiatic Society of Bombay, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Bombay Branch. Journal, Volume 24. Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. p. 49.)

The locus of the main battle is near Parusni River (modern Ravi), Punjab. This battle records the victory of Tr̥tsu-Bharata (Puru) led by King Sudas, resulting in the settlement of Bharatas in Kurukshetra and emergence of Kuru kingdom. R̥gveda Maṇḍala 3 is attributed to the Bharata R̥ṣi Viśvāmitra. In this Maṇḍala 3, Viśvāmitrarefers to Bhāratam Janam, 'Bharata people or Bharata kula'. भारत as perceived by Visvamitra is cognate with 1. भारत episodes and narratives of the Great Epic and 2 .panca janah Aditi of Taitt. Sam. 7.6.1.1Pañca-janāḥ (Rv, 1.89.10; 3.37.9; 5.9.8; etc.), भारत and म्लेच्छ mleccha are the most frequently mentioned groups or collectives of people in the Veda texts and in the Great Epic, महाभारतम्. These are narratives related to the people of भरतवर्ष –and abbreviated synonyms or semantic variants of the expression: Bhārtam Janam. In the days of the Rigveda, these Bhārtam Janam had gained proficiency in working with metals and alloys, creating metal sculptures using cire perdue techniques, producing tools, pots and pans, weapons of metal and spoked-wheel chariots. In the days related to the events narrated in महाभारतम्. which expanded the Tin-Bronze Age into the Iron Age, a framework for social regulation and creation of the rashtram was outlined, consistent with the ideas formulated in Vagdevi Suktam of Rigveda (aham rashtrii samgamani vasuunaam..)

.

Ancient Age. The Iberians and the Celts. The Iberian towns occupied the coasts of the south and east of the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th century BC. In the north of the Ebro, these towns had some common cultural characteristics, such as language and writing, mastery of iron metallurgy and potter's turn and basically agricultural economics. The basis of the social organization of the Iberians was the tribe, headed by the monarchy and the warrior aristocracy. The Iberians placed their villages in high places to facilitate their defense and organized them as cities. We have witnessed his burial ritual thanks to the cemeteries that have left us, where Iberian pieces have been found in the tombs.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

The Celts lived in a much larger territory: in the British Isles and in Ireland, in France, previously called Galicia, Portugal, Galicia, Asturias, Extremadura and a part of Castile and Leon, Switzerland, Belgium, Netherlands (Netherlands) , part of Germany, Xequia, Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, the central part of Italy, Romania, Bulgaria, part of the former Yugoslavia, and the central part of Turkey. The Celts lived from 1000 BC until the year 43 BC, after the Romans expelled them from their territories, the Celts (the majority) became Roman, but in Ireland there were some who still populated it. The most relevant of his tribe was that they were experts in the manufacture of weapons, armor, helmets and other types of armor with bronze. They also had druids who were the wizards of the tribe, worked hard on the field, their tools were very similar to ours, they used the sickle and the plow, and they also had the king or queen that ruled them.

http://ticotazos.blogspot.com/2013/05/edat-antiga-els-ibers-i-els-celtes.html

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Interior Santa Tecla Celtic dwelling, Spain. 2nd century B.C.]()

"Interior de un castro" Interior Santa Tecla Celtic dwelling, Spain. 2nd century B.C.E Castro, in a Celtic Village. "Amazing ruins of an ancient tribal village spanning the slopes of a mountain in Northern Spain. Santa Tecla Celtic Village clearly displays celtic village life.The uncovered ruins are a sight to see obviously each hut is connected to the group sharing a partial circular wall. They appear similar in size bases constructed of local stone with central gathering areas." https://www.tripadvisor.in/Attraction_Review-g2137545-d3291950-Reviews-Santa_Tecla_Celtic_Village-A_Guarda_Province_of_Pontevedra_Galicia.html

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Built over a wide river with access to the North Sea and inland farms these Bronze Age houses could have easily traded grain, meat and metal tools. Yet not long after they were built 3,000 years ago the houses burned down and collapsed into the water preserving their contents | Illustration by Adolfo Arranz and Chris Bickel]()

"Built over a wide river with access to the North Sea and inland farms these Bronze Age houses could have easily traded grain, meat and metal tools. Yet not long after they were built 3,000 years ago the houses burned down and collapsed into the water preserving their contents | Illustration by Adolfo Arranz and Chris Bickel." https://www.pinterest.com/pin/554365035365893664/

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() A celtic village. Drawsing.

A celtic village. Drawsing.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Modern depiction of Celtic Roundhouse, The Din Lligwy Ancient Village, 3-4th century AD, North Wales.]()

Modern depiction of Celtic Roundhouse, The Din Lligwy Ancient Village, 3-4th century CE, North Wales. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/286963807481590855/

Mudhif: Giant reed houses made in the marshes of Southern Iraq

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Houses made of reed Iraq]()

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/520447300685745184/

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Mudhif Houses â Al-Chibayish, Iraq | Atlas Obscura]()

Ma’dan reed houses , Iraq

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/mudhif-houses

Mudhif and three reed banners

Sumerian mudhif and Sohgaura copper plate signify Indus Script hypertexts of metalwork https://tinyurl.com/yczjracd

The products produced by artisans working on the platforms of Harappa are linked to Indus Script wealth accounting system through miniature tablets of Harappa with Meluhha inscriptions which are written documents, metalwork accounting ledgers.

Clik here to view.![Image result for bharhut hut]() Toda hut with reed roof.

Toda hut with reed roof.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Related image]() Hut. Islamkot. Thar Parkar. Sind. Pakistan.

Hut. Islamkot. Thar Parkar. Sind. Pakistan.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Image result for bharhut hut]() Mud huts. Cholistan. Pakistan.

Mud huts. Cholistan. Pakistan.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Roofed circular hut. Bharhut sculptural frieze. It is possible that the circular working platforms had comparable roof structures.

Roofed circular hut. Bharhut sculptural frieze. It is possible that the circular working platforms had comparable roof structures.

See: Battle of R̥gveda texts. Battle of Ten Kings (dāśarājñá) in R̥gveda https://tinyurl.com/yckdognr This link includes full texts from R̥gveda (with alternative translations) and full texts of the papers of Stuhrmann, Witzel and Talageri. An earlier comment of Talageri:

With thee are milchkine- good to milk, and horses: best winner thou of riches for the pious.

2 For like a King among his wives thou dwellest: with glories, as a Sage, surround and help us.

Make us, thy servants, strong for wealth, and honour our songs wirth kine and steeds and

decoration.

3 Here these our holy hymns with joy and gladness in pious emulation have approached thee.

Hitherward come thy path that leads to riches: may we find shelter in thy favour, Indra.

4 Vasistha hath poured forth his prayers, desiring to milk thee like a cow in goodly pasture.

All these my people call thee Lord of cattle: may Indra. come unto the prayer we offer.

5 What though the floods spread widely, Indra made them shallow and easy for Sudas to traverse.

He, worthy of our praises, caused the Simyu, foe of our hymn, to curse the rivers' fury.

6 Eager for spoil was Turvasa Purodas, fain to win wealth, like fishes urged by hunger.

The Bhrgus and the Druhyus quickly listened: friend rescued friend mid the two distant peoples.

7 Together came the Pakthas, the Bhalanas, the Alinas, the Sivas, the Visanins.

Yet to the Trtsus came the Aryas' Comrade, through love of spoil and heroes' war, to lead them.

8 Fools, in their folly fain to waste her waters, they parted inexhaustible Parusni.

Lord of the Earth, he with his might repressed them: still lay the herd and the affrighted

herdsman.

9 As to their goal they sped to their destruetion: they sought Parusni; even the swift returned

not.

Indra abandoned, to Sudas the manly, the swiftly flying foes, unmanly babblers.

10 They went like kine unherded from the pasture, each clinging to a friend as chance directed.

They who drive spotted steeds, sent down by Prsni, gave ear, the Warriors and the harnessed horses.

11 The King who scattered oneandtwenty— people of both Vaikarna tribes through lust of glory-

As the skilled priest clips grass within the chamber, so hath the Hero Indra, wrought their

downfall.

12 Thou, thunderarmed-, overwhelmedst in the waters famed ancient Kavasa and then the Druhyu.

Others here claiming friendship to their friendship, devoted unto thee, in thee were joyful.

13 Indra at once with conquering might demolished all their strong places and their seven castles.

The goods of Anus' son he gave to Trtsu. May we in sacrifice conquer scorned Puru.

14 The Anavas and Druhyus, seeking booty, have slept, the sixty hundred, yea, six thousand,

And sixandsixty— heroes. For the pious were all these mighty exploits done by Indra.

15 These Trtsus under Indras' careful guidance came speeding like loosed waters rushing downward.

The foemen, measuring exceeding closely, abandoned to Sudas all their provisions.

16 The heros' side who drank the dressed oblation, Indras' denier, far over earth he scattered.

Indra brought down the fierce destroyers' fury. He gave them various roads, the paths' Controller.

17 even with the weak he wrought this matchless exploit: even with a goat he did to death a lion.

He pared the pillars' angles with a needle. Thus to Sudas Indra gave all provisions.

18 To thee have all thine enemies submitted: even the fierce Bheda hast thou made thy subject.

Cast down thy sharpened thunderbolt, O Indra, on him who harms the men who sing thy praises.

19 Yamuna and the Trtsus aided Indra. There he stripped Bheda bare of all his treasures.

The Ajas and the Sigrus and the Yaksus brought in to him as tribute heads of horses.

20 Not to be scorned, but like Dawns past and recent, O Indra, are thy favours and thy riches.

Devaka, Manyamanas' son, thou slewest, and smotest Sambara from the lofty mountain.

21 They who, from home, have gladdened thee, thy servants Parasara, Vasistha, Satayatu,

Will not forget thy friendship, liberal Giver. So shall the days dawn prosperous for the princes.

22 Priestlike-, with praise, I move around the altar, earning Paijavanas' reward, O Agni,

Two hundred cows from Devavans' descendant, two chariots from Sudas with mares to draw them.

23 Gift of Paijavana, four horses bear me in foremost place, trained steeds with pearl to deck

them.

Sudass' brown steeds, firmlystepping-, carry me and my son for progeny and glory.

24 Him whose fame spreads between wide earth and heaven, who, as dispenser, gives each chief his

portion,

Seven flowing Rivers glorify like Indra. He slew Yudhyamadhi in close encounter.

25 Attend on him O ye heroic Maruts as on Sudass' father Divodasa.

Further Paijavanas' desire with favour. Guard faithfully his lasting firm dominion.

over.

I warned the men, when from the grass I raised me, Not from afar can my Vasisthas help you.

2 With Soma they brought Indra from a distance, Over Vaisanta, from the strong libation.

Indra preferred Vasisthas to the Soma pressed by the son of Vayata, Pasadyumna.

3 So, verily, with these he crossed the river, in company with these he slaughtered Bheda.

So in the fight with the Ten Kings, Vasisthas! did Indra help Sudas through your devotions.

4 I gladly, men I with prayer prayed by our fathers have fixed your axle: ye shall not be injured:

Since, when ye sang aloud the Sakvari verses, Vasisthas! ye invigorated Indra.

5 Like thirsty men they looked to heaven, in battle with the Ten Kings, surrounded and imploring.

Then Indra heard Vasistha as he praised him, and gave the Trtsus ample room and freedom.

6 Like sticks and staves wherewith they drive the cattle, Stripped bare, the Bharatas were found

defenceless:

Vasistha then became their chief and leader: then widely. were the Trtsus' clans extended.

7 Three fertilize the worlds with genial moisture: three noble Creatures cast a light before them.

Three that give warmth to all attend the morning. All these have they discovered, these Vasisthas.

8 Like the Suns' growing glory is their splendour, and like the seas' is their unflathomed

greatness.

Their course is like the winds'. Your laud, Vasisthas, can never be attained by any other.

9 They with perceptions of the heart in secret resort to that which spreads a thousand branches.

The Apsaras brought hither the Vasisthas wearing the vesture spun for them by Yama.

10 A form of lustre springing from the lightning wast thou, when Varuna and Mitra saw thee.

Thy one and only birth was then, Vasistha, when from thy stock Agastya brought thee hither.

11 Born of their love for Urvasi, Vasistha thou, priest, art son of Varuna and Mitra;

And as a fallen drop, in heavenly fervour, all the Gods laid thee on a lotusblossorn-.

12 He thinker, knower both of earth and heaven, endowed with many a gift, bestowing thousands,

Destined to wear the vesture spun by Yama, sprang from the Apsaras to life, Vasistha.

13 Born at the sacrifice, urged by adorations, both with a common flow bedewed the pitcher.

Then from the midst thereof there rose up Mana, and thence they say was born the sage Vasistha.

14 He brings the bearer of the laud and Saman: first shall he speak bringing the stone for

pressing.

With grateful hearts in reverence approach him: to you, O Pratrdas, Vasistha cometh.

spoil.

Ye smote and slew his Dasa and his Aryan enemies, and helped Sudas with favour, IndraVaruna-.

2 Where heroes come together with their banners raised, in the encounter where is naught for us to

love,

Where all things that behold the light are terrified, there did ye comfort us, O IndraVaruna-.

3 The boundaries of earth were seen all dark with dust: O IndraVaruna-, the shout went up to

heaven.

The enmities of the people compassed me about. Ye heard my calling and ye came to me with help.

4 With your resistless weapons, IndraVaruna-, ye conquered Bheda and ye gave Sudas your aid.

Ye heard the prayers of these amid the cries of war: effectual was the service of the Trtsus'

priest.

5 O IndraVaruna-, the wickedness of foes and mine assailants' hatred sorely trouble me.

Ye Twain are Lords of riches both of earth and heaven: so grant to us your aid on the decisive day.

6 The men of both the hosts invoked you in the fight, Indra and Varuna, that they might win the

wealth,

What time ye helped Sudas, with all the Trtsu folk, when the Ten Kings had pressed him down in

their attack.

7 Ten Kings who worshipped not, O IndraVaruna-, confederate, in war prevailed not over Sudas.

True was the boast of heroes sitting at the feast: so at their invocations Gods were on their side.

8 O IndraVaruna-, ye gave Sudas your aid when the Ten Kings in battle compassed him about,

There where the whiterobed- Trtsus with their braided hair, skilled in song worshipped you with

homage and with hymn.

9 One of you Twain destroys the Vrtras in the fight, the Other evermore maintains his holy Laws.

We call on you, ye Mighty, with our hymns of praise. Vouchsafe us your protection, IndraVaruna-.

10 May Indra, Varuna, Mitra, and Aryaman vouchsafe us glory and great shelter spreading far.

We think of the beneficent light of Aditi, and Savitars' song of praise, the God who strengthens

Law.

Clik here to view.

Circular dwelling houses at Farmana See:

Harappan Civilization: Current Perspective and its Contribution – By Dr. Vasant Shinde (Feb. 2016) https://www.sindhulogy.org/cdn/articles/harappan-civilization-current-perspective-and-its-contribution-vasant-shinde/

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Vedic house.

Vedic house.Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Bhirrana dancing girl on a potsherd is Indus Script hypertext.

Hieroglyph: meḍ 'to dance' (F.)[reduplicated from me-]; me id. (M.) in Remo (Munda)(Source: D. Stampe's Munda etyma) meṭṭu to tread, trample, crush under foot, tread or place the foot upon (Te.); meṭṭu step (Ga.); mettunga steps (Ga.). maṭye to trample, tread (Malt.)(DEDR 5057)

Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Mundari. Remo.) karaṇa 'dance posture' rebus:karaṇa 'scribe'.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Bhirrana Indus Script seals

Bhirrana Indus Script sealsImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

THE EXCAVATION OF 2003-04 yielded inscribed copper celts.

The finding of a needle suggested that some kind of a stitched clothing was used. As if to confirm this, a potsherd with a painting was found: Amarendra Nath said, “This is a rare painting in the Harappan context, wherein you get evidence of a person wearing a dhoti and a stitched upper garment.”

ASI

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

THE ARTEFACTS UNEARTHED include pottery and potsherds, an ivory comb, bone points and chert blades.

A number of sealings and seals were found. (A seal is an original stone object, which is carved in depth. A sealing is an impression of a seal.) One of them is a cylindrical seal, which indicates contact with contemporary urban centres in Iraq. This seal has an engraving of a crocodile on the one side and Harappan characters on the other. Such types of seals have been found in Iraq. The significance of the Rakhigarhi site also lies in its having 11 burials, with the skeletons aligned north to south. The skeletons were laid in pits with grave goods, copper bangles and shell bangles. Arun Malik found an intact skeleton in a pit. The burial site is located north of the habitational site.

http://www.frontline.in/navigation/?type=static&page=flonnet&rdurl=fl2502/stories/20080201504012900.htm

Rammed floor with hearth.

Bhirrana house structures in the form of subterranean dwelling pits were, cut into the natural soil. The walls and floor of these pits were plastered with the yellowish alluvium of the Saraswati valley.Apart from Trtsu Puru (Bharata) named in RV 7.33, the belligerents in the battle are: Ten listed as Turvasa, Yaksu (pun for Yadu), Matsya, Bhrgu, Druhyu, Paktha, Bhalana, Alina, Shiva and Visanin Other belligerents are Anava (Anu)(RV 7.18.14), the Aja and Sigru (RV 7.18.19) and the "21 men of both Vaikarna tribes" (RV 7.18.11) without a king, and individual kings Bheda (7.18.19, also mentioned RVv 7.33.3 and RV 7.83.4, the main leader slain by Sudas), Shimyu (RV 7.18.5), and Kavasa (RV 7.18.12). Puru, Parśu and Pani are also belligerents.

In one battle on the banks of Ravi river, the kings of Anu and Druhyu kingdoms were drowned.

Shrikant Talageri provides the following identities of belligerents in the Ten Kings' Battle:

Prthu or Parthava (RV 7-83-1) Parthians

Parsu or Parsvas (7-83-1) Persians

Paktha (7-18-7) Paktoons

Bhalana (7-18-7) Baluchis

Siva (7-18-7) Kivas

Visanin (7-18-7) Pisachas/Dards

Simyu (718-5) Sarmatians(ancient Albanians)

Alina (7-18-7) Alans /Hellennes/ Ancient Greeks

Bhrgu (7-18-6) Phyrgians

In another battle on the banks of Yamuna river, Sudas fought with and won against Aja, Sigru and Yaksu who had united under King Bheda.

Turvasas and Yaksus (Yadu), together with the Matsya people (punned upon by the R̥ṣi by comparing them to hungry fish (matsya) flocking together) appear and ally themselves with the Bhr̥gu:and the Druhyu.

What was the objective of the battle? In my view, the battlefield in the Ravi riverbasin and the key cause for the battle is provided by the metaphor of 'hungry fish' used in RV VII.18.6:

"Eager for spoil was Turvasa Purodas, fain to win wealth, like fishes urged by hunger.

The Bhrgus and the Druhyus quickly listened: friend rescued friend mid the two distant peoples." (Griffith translation)

Sayana/Wilson translate the r̥ca focussing on Turvaśa's mission to acquire wealth: Turvas'a, who was presiding (at solemn rites), diligent in sacrifice, (went to Suda_sa) for wealth; but like fishes restricted (to the element of water), the Bhrigus and Druhyus quickly assailed them; of these two everywhere going the friend (of Suda_sa, Indra) rescued his friend.

रयि m. or (rarely) f. (fr. √ रा ; the following forms occur in the वेद , रयिस् , °य्/इम् , °यिभिस् , °यीणाम् ; रय्य्/आ,°य्य्/ऐ,°य्य्/आम् ; cf. 2. रै) , property , goods , possessions , treasure , wealth (often personified) RV. AV. VS. Br. S3rS. ChUp.

This comparison of Matsya people with 'hungry fish' means, that there were rivalries among the people about the use of water from the rivers for their livelihoods (hence, the signifier of hungry fish) and about the impediments caused to acquire wealth.

The pun on the word matsya, 'fish' is also a reference to the name of peoples called matsya. Matsya is one of the 16 janapada-s. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matsya_Kingdom This may explain the reason why the battle was joined by ten kings since a large number of people from the region of North India were concerned about their livelihood, searching for avenues to acquire wealth.

Another interpretation is possible. The fish is an Indus Script hypertext. It signifies aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'. The metaphor 'hungry fish' may thus be a refererence to the belligerents desirous of acquiring and possessing wealth derived from metalwork.

- Alinas: defeated by Sudas lived to the north-east of Nuristan, because the land was mentioned by the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang (Macdonell and Keith, Vedic Index, 1912, I, 39.)

- Anu: People in the Paruṣṇī (Ravi) area.

- Bhr̥gu: Probably the priestly family descended from the ancient Kavi Bhr̥gu. Later, they are related to the composition of parts of the Atharva Veda (Bhṛgv-Āṅgirasa) .

- Bhalana: Fought against Sudas; perhaps lived in the Bolan Pass area.

- Druhyu: Could be Gandhari (RV I 1.126.7).

- Matsya are only mentioned in the RV (7.18.6), but later in connection with the Śālva.

- Parśu: The Parśu have been connected by some with the ancient Persians. (Macdonell and Keith, Vedic Index. This is based on the evidence of an Assyrian inscription of 844 BCE referring to the Persians as Paršu, and the Behistun Inscription of Darius I of Persia referring to Parsa (Pārsa) as the area of the Persians. Radhakumud Mookerji (1988). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (p. 23). Motilal Banarsidass)

- Puru: A major confederation in the Rigveda.

- Pani: A bargainer, market, N. of a class of envious demons watching over treasures RV. (esp. x , 108) AV. Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa; later associated with the Scythians.

दशराज्ञ युद्ध Daśarājñá yuddha, Battle of Ten Kings is referred to in R̥gveda (Maṇḍala 7, hymns 18, 33 and 83.4–8), (Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, p.1). K. F. Geldner in his 1951 translation of the Rigveda considers the hymns as "obviously based on an historical event". [Geldner, Karl Friedrich, Der Rig-Veda: Aus dem Sanskrit ins Deutsche übersetzt Harvard Oriental Studies, vols. 33, 34, 35 (1951), reprint Harvard University Press (2003)] Further elaboration in Schmidt, H.P. Notes on Rgveda 7.18.5–10. Indica. Organ of the Heras Institute, Bombay. Vol.17, 1980, 41–47.

pancajana, pancakrishtya or pancamanusha are five sons of Yayati: तुर्वश,

Turvaśa, lived southeast of the Sarasvati river region; the other four are Yadu, Druhyu, Anu and Puru. Yadu and Turvaśa were born to Devayani, and the other three were born to Śarmiṣṭha. Cholas, Pandyas, Cheras have descended from Turvaśa, (Asiatic Society of Bombay, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Bombay Branch. Journal, Volume 24. Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. p. 49.)

RV 3.53.12 Praises to Indra have I sung, sustainer of this earth and heaven. This prayer of Viśvāmitra keeps secure the race of Bharatas.

The locus of the main battle is near Parusni River (modern Ravi), Punjab. This battle records the victory of Tr̥tsu-Bharata (Puru) led by King Sudas, resulting in the settlement of Bharatas in Kurukshetra and emergence of Kuru kingdom. R̥gveda Maṇḍala 3 is attributed to the Bharata R̥ṣi Viśvāmitra. In this Maṇḍala 3, Viśvāmitrarefers to Bhāratam Janam, 'Bharata people or Bharata kula'. भारत as perceived by Visvamitra is cognate with 1. भारत episodes and narratives of the Great Epic and 2 .panca janah Aditi of Taitt. Sam. 7.6.1.1Pañca-janāḥ (Rv, 1.89.10; 3.37.9; 5.9.8; etc.), भारत and म्लेच्छ mleccha are the most frequently mentioned groups or collectives of people in the Veda texts and in the Great Epic, महाभारतम्. These are narratives related to the people of भरतवर्ष –and abbreviated synonyms or semantic variants of the expression: Bhārtam Janam. In the days of the Rigveda, these Bhārtam Janam had gained proficiency in working with metals and alloys, creating metal sculptures using cire perdue techniques, producing tools, pots and pans, weapons of metal and spoked-wheel chariots. In the days related to the events narrated in महाभारतम्. which expanded the Tin-Bronze Age into the Iron Age, a framework for social regulation and creation of the rashtram was outlined, consistent with the ideas formulated in Vagdevi Suktam of Rigveda (aham rashtrii samgamani vasuunaam..)

The narratives of महाभारतम् related to material aspects of lives of people correlate with the archaeological finds of over 2000 sites on the banks of Vedic River Sarasvati. The archaeological finds attest the continuum of Veda cultural traditions exemplified by 1. the performance of Soma SamsthA YAgas and 2. metalwork contributions of the people during the Bronze Age, recorded on over 8000 Harappa (Indus) Script inscriptions which are metalwork catalogues. The continued use of Harappa (Indus) Script hieroglyphs/hypertexts as signifiers of metalwork during the Coinage period is attested in tens of thousands of punch-marked and cast coins of the civilization. Across the entire civilization area from Takshasila to Anuradhapura, punch-mark symbols are derived from Harappa (Indus) Script hieroglyphs/hypertexts.

This narrative of Sauptikaparvan of महाभारतम् is of fundamental significance in defining the weltanschauung, the value-frame of Bhārtam Janam in reference to dharma, ‘performance of duties’ and daiva, ‘fate’ which impacts material, wealth-creating activities and lend meaning to ‘being’ and ‘becoming’.

भारत [p= 753,1] mf(ई)n. descended from भरत or the भरतs (applied to अग्नि either ” sprung from the priests called भरतs ” or ” bearer of the oblation “) RV. &c; belonging or relating to the भरतs (with युद्ध n. संग्राम m. समर m. समिति f. the war or battle of the भरतs ; with or scil. आख्यानn.with इतिहास m. and कथा f. the story of the भरतs , the history or narrative of their war ; with or scil. मण्डल n. or वर्ष n. ” king भरतs’s realm ” i.e. India) MBh. Ka1v. &c; inhabiting भरत-वर्ष i.e. India BhP.

Metalwork hypertexts/hieroglyphs rendered rebus in Harappa (Indus) Script inscriptions: balad m. ox , gng.bald , (Ku.)barad , id. (Nepali. Tarai) Rebus: bharat (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1tin)(Punjabi) Rebus: bharata ‘alloy of copper, pewter, tin’ (Marathi) bhāraṇ = to bring out froma kiln (G.) bāraṇiyo = one whose profession it is to sift ashes or dust in a goldsmith’s workshop(G.lex.) In the Punjab, the mixed alloys were generally called, bharat (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin).In Bengal, an alloy called bharan or toul was created by adding some brass or zinc into purebronze. bharata = casting metals in moulds; bharavum = to fill in; to put in; to pour into (G.lex.) Bengali. ভরন [ bharana ] n an inferior metal obtained from an alloy of coper, zinc andtin.baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)ixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

भारत m. fire L. n. the story of the भरतs and their wars (sometimes identified with the महा-भारत , and sometimes distinguished from it) MBh. Ra1jat. IW. 371 n. 1 and 2.

भरतवर्ष न० ६ त० । भारते वर्षे ।भरतखण्ड कुमारिकाखण्डे “कुमारिकेति विख्याता यस्या नाम्ना प्रकथ्यते । इदं कुमारिकाखण्डं चतुर्वर्गफल-व्रदम् । यथा कृतावनीयञ्च नानाग्रामादिकल्पना ।इदं भरतखण्डश्च मया सम्यक् प्रकल्पितम्” स्कन्दपु० । https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/वाचस्पत्यम्

Sanjaya said, “They had not proceeded far, O king, when they stopped, for they beheld a dense forest abounding with trees and creepers…At that hour, filled with grief and sorrow, Kritavarma and Kripa and Drona’s son all sat down together. Seated under that banyan, they began to give expression to their sorrow in respect of that very matter: the destruction that had taken place of both the Kurus and the Pandavas. Heavy with sleep, they laid themselves down on the bare earth. They had been exceedingly tired and greatly mangled with shafts. The two great car-warriors, Kripa and Kritavarma, succumbed to sleep. However deserving of happiness and undeserving of misery, they then lay stretched on the bare ground. Indeed, O monarch, those two who had always slept on costly beds now slept, like helpless persons, on the bare ground, afflicted with toil and grief…Drona’s son, however, O Bharata, yielding to the influence of wrath and reverence, could not sleep, but continued to breathe like a snake. Burning with rage, he could not get a wink of slumber. That hero of mighty arms cast his eyes on every side of that terrible forest.”Dhritarashtra asks Sanjaya: “What, however, did Kritavarma and Kripa and Drona’s son do after my son Duryodhana had been unfairly stuck down?”

Vaishampayana continues the narrative, addressing Yudhisthira:” O Pandava! The world once more became safe and sound. The gods assigned unto Mahadeva all the libations of clarified butter as the share of great deity. O monarch, when Mahadeva had become angry, the whole world had thus become agitated: when he became gratified everything became safe. Possessed of great energy, the god Mahadeva was gratified with Ashvatthama. It was for this that thy sons, those mighty car-warriors, could be slain by that warrior. It was for this that many other heroes, the Pancalas, with all their followers, could be slain by him. Thou shouldst not suffer thy mind to dwell on it. It was not Drona’s son that accomplished that act. It was done through the grace of Mahadeva. Do now what should next be done.” http://sacred-texts.com/hin/m10/m10018.htm

Book 10 called Sauptikaparva narrates the inevitability of daiva, ‘fate’. The book recounts renunciation of throne of Hastinapur by Yudhisthira. सौप्तिक mfn. (fr. सुप्त) connected with or relating to sleep , nocturnal Mr2icch. n. an attack on sleeping men , nocturnal combat MBh. R. Ka1m. Thus, the narrative in Book 10 is about sleeping men, an extraordinary metaphorical rendering of the inexorable phenomenon of daiva, ‘fate’.

अश्वत्थामा, Aśvatthāmā is commander-in-chief of Duryodhana’s army and seeks to take revenge on Pandavas for the injustices done to Kauravas. He ends up killing the Upapandavas and Uttara.

The Pandavas including Draupadi, journey through the country before their final journey to heaven.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![mbh1]()

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![136973-004-E93CD713]() Pandavas. Draupadi. Dashavatara temple, Deogarh, Rajasthan.

Pandavas. Draupadi. Dashavatara temple, Deogarh, Rajasthan.

Clik here to view.

Pandavas. Draupadi. Dashavatara temple, Deogarh, Rajasthan.

Pandavas. Draupadi. Dashavatara temple, Deogarh, Rajasthan.Sculptures in hypertexts, metaphors of Candi Sukuh Java, Bhima Swarga iconographic metaphors of Bali compare with Indus Script metalwork heritage. Bhima is the smith producing a sword. Ganesa takes a dance-step. Arjuna works at the bellows.

The story of Bhima Swarga is painted around the ceiling of the Kertha Gosa Pavilion of 18thcent. at Klungkung, Bali, Indonesia. Bhima Swarga is referenced from the Mahabharata..The journey of aatman from hell to heaven narrated by Bhima Swarga (in Bali tradition) is ametaphor parallel to the Indus Script archives documenting production (purification) of metalfrom mere earth and stone through furnaces.The Candi Sukuh sculptures (in Java tradition) are also in the metalwork tradition documentingBhima and Arjuna as metalworkers.Bhima Swarga episodes are also signified on candi Sukuh sculptures with Indus Scriptmetalwork hieroglyphs and metaphors.

The total categories of people specifically named in the Great Epic number 850. In all these names which indicative collective groups of people, the most dominant use occurs for Bharatas in the Great Epic, Mahābhārata (Bharata 2261, Bharatas 418 and Bharata’s 668). Other frequencies of names of people in Mahābhārata relate mostly to mleccha (Meluhha) who mispronounce words:

Abhiras (8), Aila (14), Aja (4), Amvastha (20), Andhaka (37), Anga (52), Aratta (11), Aratta-Vahika (2), Artayani (8), Asmaka (3), Arya (3), Avanti (5), Bahlika (12), Banga (2), Barbara (5), Bharata (3,547), Bhoja (110), Bhuta (9), Brahmasastri (3), Cedi (132), China (8), Chola (4), Danda (15), Darada (18), Dasarha (121), Dasarnaka (43), Daseraka (5), Dravida (13), Dundubha (2), Gana (17), Gandhara (36), Gautami (15), Gopala (4), Govasan (4), Haihaya (30), Hansa (2), Huna (3), Ikshvaku (53), Kaikeya (92), Kalinga (87), Kamatha (1), Kamboja (75), Kanchi (7), Kanka (21), Kapa (15), Karnata (1), Karusha (25), Kashmira (8), Katirava (12), Kaunteya (12), Kauraka (460), Kekaya (55), Kerala (5), Khalin (2), Khasa (11), Kichaka (135), Kirata (22), Kitava (5), Kosala (36), Kshudraka (6), Kukura (13), Kulinda (8), Kumara (3), Kuntala 6), Kunti (1001), Kuru (1460), Kuru-Panchala (1), Kurd (1), Kusika (50), Madhu (254), Madra (56), Magadha (60), Mahisha (20), Malava (32), Malla (5), Manasa (2), Matsya (158), Mekala (5), Mleccha (66), Munda (2), Naimisha (3), Nairita (4), Nishada (184), Narayana (7), Nipa (4), Odra (1), Pahlava (3), Panchala (693), Pandava (2275), Pandya (7), Pannaga (11), Parada (6),Parvata (49), Patacchara (3), Pauloma (8), Paundra (12), Paundramatsyaka (1), Paurava (40), Prabhadra (37), Prabhadra-Panchala (1), Prachetasa (2), Pramatha (3), Pukkasa (4), Pulinda (15), Pundra (6), Raghava (1), Ramatha (4), R̥bhu (3), Rishika (6), Rohita (1), Siindhu, Saindava (244), Saka (40), Salwa (40), Samsaptaka (45), Sarabha (3), Sarava (1), Samgaka (7), Sattvata (157), Sauvira (25), Singhala (5), Sivi (27) Somaka (135). Srinjaya (307), Sura (37), Surasena (23), Surashtra (2), Swaitya (29), Savara (10), Shalva (2), Talajangha (8), Tamraliptaka (7), Tangana (12), Tapatya (5), Takshya (2) Trigarta (104), Tukhara (2), Tundikera 92), Tushara 93), Uluka (82), Uraga (40), Usinara (15), Utkala (2), Uttara-Kuru (6), Vabhravya (2), Vahika (28), Vahlika (134), Vaikanasa (14), Vaiswanara (2), Vaivaswata (9),Valmiki (9) Vanga (14), Vashneya (21), Vasati (17), Vatadhana (4), Vatsa (3), Vidarbha (35), Videha (33), Vaideha (5), Vodha (2), Vrishala (2), Vrishni (487), Yadava (68), Yadu (88), Yaudheya (3), Yavana (53), Yayavara (6)

In the context of life-activities of the people of the Bronze Age, Bharatam Janam refers to metalcasters: bharata ‘alloy of copper, pewter, tin’.Thus, I suggest that the people identified as Bharatam Janam by Rishi Visvamitra (RV 3.53.12) refers to all the people in general, the Panca jana, ‘the collective of five peoples, i.e. people in general’. The expressions, pañca-pañca-janāh or pañca-janāh refer to a collective of people. It is not necessary to precisely delineate and identify the specific groups of people referred to in this collective category of ‘four’ or ‘five’ people. For e.g., an idiom in Tamil refers to nāluper ‘four persons’ in a general reference to the ‘people’ in general and in some specific instances refers to the four pall-bearers who carry the corpse to the cremation ground. So, the idiom is: nāluper enna colluvā?‘What will four people say’ i.e. a reference to the general consensus of the people of the family circles whose opinion is the determinant of a value system, a norm in social parlance.

In the context of frequent references to mleccha as people inhabiting Bharata Varsha in many islands and in many parts of Bharata, mleccha speakers (mlecchavAcas) constituted the speaker of the lingua france, Meluhha, who pronounced Samskritam words in the colloquial tongue with mispronunciations and variant spellings. Hence, the pronunciation variations recorded in the Indian Lexicon which is a compendium of over 8000 semantic clusters encompassing Indo-Aryan, Dravidian and Mundarica streams, thus establishing the reality of Bharata sprachbund of the Bronze Age. Mleccha as the lingua franca, is attested by Manu and recognized by Bharata. These tongues are later categorized as Apabhrams’a or Apas’abda or as Desi in Hemacandra’s Desi NAmamAlA, a Prakritam lexicon.