--Meluhha metals trade in BMAC. Gonur cuneiform cylinder buffalo seal of Ibni-sharrum, the scribe and Gonur Indus Script elephant seal iron metalwork wealth-accounting ledger

Anau Indus Script seal

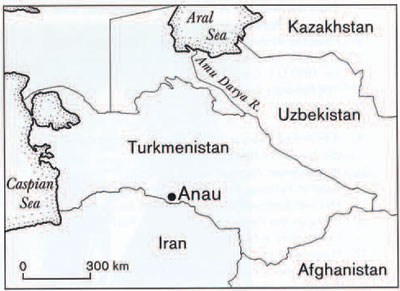

![anau_turkmenistan_map]()

See: http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp124_anau_niya_seals.pdf Fredrik T. Hiebert (2002), The Context of the Anau Seal."It most likely reflects a local symbolic system. Seals are used in the administrative system of an economy that needs to keep track of goods such as supplies for temples, barracks, or palaces. Even a small site like Anau has imposing architectural remains, and now we have in this seal evidence for Ana’s involvement in a managed system of distribution. This pattern of small and large sites having elite and bureaucratic functions is unique to the Central Asian Bronze Age." (Fredrik T. Hiebert, 2000, Unique Bronze Age Stamp Seal Found in Central Asia, Expedition, Vol. 42, Issue 3)

https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/unique-bronze-age-stamp-seal-found-in-central-asia/

![]()

![map showing location of Anau]()

Anau Indus Script seal

See: http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp124_anau_niya_seals.pdf Fredrik T. Hiebert (2002), The Context of the Anau Seal."It most likely reflects a local symbolic system. Seals are used in the administrative system of an economy that needs to keep track of goods such as supplies for temples, barracks, or palaces. Even a small site like Anau has imposing architectural remains, and now we have in this seal evidence for Ana’s involvement in a managed system of distribution. This pattern of small and large sites having elite and bureaucratic functions is unique to the Central Asian Bronze Age." (Fredrik T. Hiebert, 2000, Unique Bronze Age Stamp Seal Found in Central Asia, Expedition, Vol. 42, Issue 3)

https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/unique-bronze-age-stamp-seal-found-in-central-asia/

Bronze Age seal from Anau, Turkmenistan. ca. 2300 -1900 BCE

dāṭu 'cross' (Telugu); Rebus: dhatu 'mineral (ore)'(Santali) dhātu 'mineral (Pali) dhātu 'mineral' (Vedic); a mineral, metal (Santali); dhāta id. (Gujarati.)

kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin)

dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS Ku. danīṛo m. ʻ harrow ʼ rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'. Thus, metalcaster smith.

koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'.

The inscription message on the Anau seal thus means: mineral, bronze, metalcasting smith workshop.

"According to Dr. Hiebert, while Anau is a small site compared to nearby Silk Road sites like Namazga depe and Altyn depe, it none-the-less shows evidence of involvement in a wide-reaching, managed system of distribution and trade occurring at perhaps hundreds of sites throughout the Central Asian Bronze Age period. "This pattern of small and large settlements having elite and bureaucratic functions is unique to the area," notes Dr. Hiebert.

In his report, Dr. Hiebert stated, "We like Anau because it was occupied for almost every period. Deposits stretch from the earliest village way of life (4500 BCE) to a Bronze Age town (2300 BCE) to a walled classical city (2nd c. BCE) which was eventually topped by a medieval mosque (1500th c CE) with glistening blue-green glazed tiles." During his excavations, Dr. Hiebert uncovered a unique engraved stamp seal made from a shiny jet-black stone. The seal bore an inscription that was emphasized with a reddish brown pigment. The design of the inscription does not match any known writing or symbol system. Researchers are careful not to claim this is a form of writing, for if it were, it would represent one of the earliest writing systems known. Writes Dr. Hiebert: "Seals are used in the administrative system of an economy that needs to keep track of goods such as supplies for temples, barracks, or palaces."

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/nisa/anau.htm

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/nisa/anau.htm

Map showing location of Anau & Kopet Dag Mountains

Image credit: Discover Magazine

"Anau (also spelled Annau, Turkmen: Änew) is a city in Turkmenistan. It is the capital of Ahal Province and is 8 km southeast of Ashgabat which is connected via the M37 highway.The name Anau is from Persian Âbe nav (آب نو) meaning "New Water...The Chalcolithic Anau culture dates back to 4500 BC, following the Neolithic Jeitun culture in the cultural sequence of southern Turkmenistan.Anau was a stopping point along the famous ancient Silk Road. Fine painted potteries are found here. Pottery similar to that of Anau (the earliest Anau IA phase) has been found as far as Shir Ashian Tepe in the Semnan Province of Iran...An enigmatic stamp seal was found here, that may be the first evidence of an indigenous written language in Anau. The new find is dated to c. 2300 BC.[Bronze Age seals from Altyndepe provide some parallels to the Anau seal. Two similar stamp seals have been found at Altyndepe with the same dimensions as the Anau seal. These seals are also similar to the ones from Tepe Hissar and from Tepe Sialk in Iran, where such seals with geometric designs go back to the 5th m. BCE. Also, some Chinese parallels to the Anau seal are possibled."

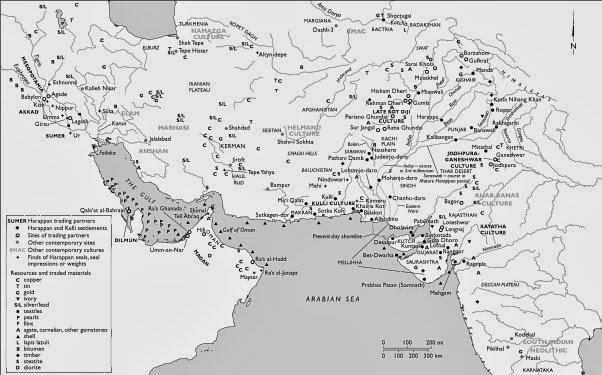

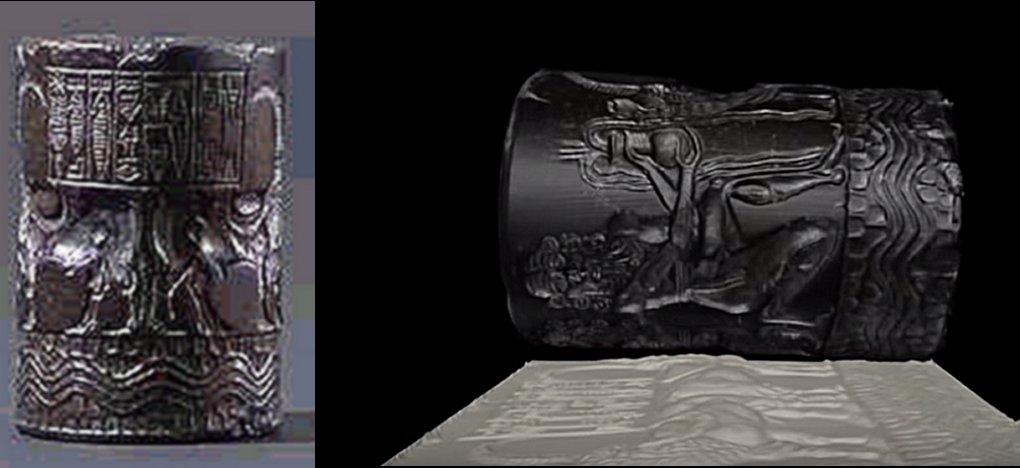

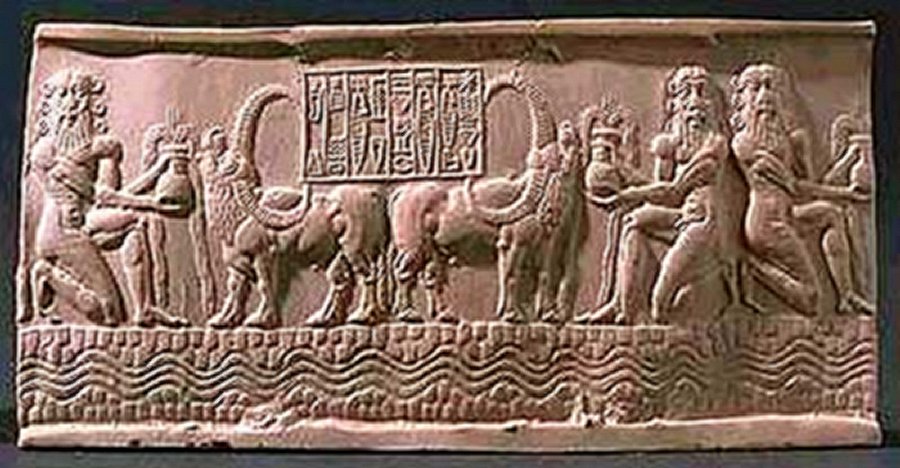

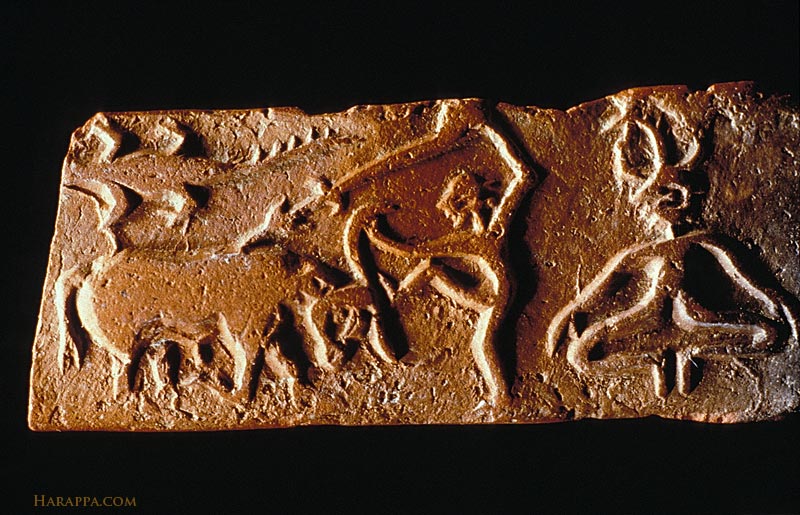

Gonur in Bactria Margiana Cultural Complex (BMAC) has yielded two remarkable seals: 1. Cylinder seal with cuneiform script of Ibni-sharrum, the scribe with water-buffaloes; 2. Square stamp seal of elephant with Indus Script inscription. This monograph posits that these two seals are cler evidence of the presence of Meluhha artisans and seafaring merchants in BMAC engaged in metals trade of the Bronze Age.

- Héros acolytes d'Ea abreuvant des buffles

- DioriteH. 3.9 cm; Diam. 2.6 cm

- Don H. de Boisgelin 1967. Ancienne collection De Clercq , 1967AO 22303

- Fine engraving, elegant drawing, and a balanced composition make this seal one of the masterpieces of glyptic art. The decoration, which is characteristic of the Agade period, shows two buffaloes that have just slaked their thirst in the stream of water spurting from two vases held by two naked kneeling heroes.

A masterpiece of glyptic art

This seal, which belonged to Ibni-Sharrum, the scribe of King Sharkali-Sharri, who succeeded his father Naram-Sin, is one of the most striking examples of the perfection attained by carvers in the Agade period. The two naked, curly-headed heroes are arranged symmetrically, half-kneeling. They are both holding vases from which water is gushing as a symbol of fertility and abundance; it is also the attribute of the god of the river, Enki-Ea, of whom these spirits of running water are indeed the acolytes. Two arni, or water buffaloes, have just drunk from them. Below the scene, a river winds between the mountains represented conventionally by a pattern of two lines of scales. The central cartouche bearing an inscription is held between the buffaloes' horns.A scene testifying to relations with distant lands

Buffaloes are emblematic animals in glyptic art in the Agade period. They first appear in the reign of Sargon, indicating sustained relations between the Akkadian Empire and the distant country of Meluhha, that is, the present Indus Valley, where these animals come from. These exotic creatures were probably kept in zoos and do not seem to have been acclimatized in Iraq at the end of the 3rd millennium BC. Indeed, it was not until the Sassanid Empire that they reappeared. The engraver has carefully accentuated the animals' powerful muscles and spectacular horns, which are shown as if seen from above, as they appear on the seals of the Indus.The production of a royal workshop

The calm balance of the composition, based on horizontal and vertical lines, gives this tiny low relief a classical monumental character, typical of the style of the late Akkadian period. Seals of this quality were the preserve of the entourage of the royal family or high dignitaries and were probably made in a workshop whose production was reserved for this elite.Bibliography

Amiet Pierre, Bas-reliefs imaginaires de l'ancien Orient : d'après les cachets et les sceaux-cylindres, exp. Paris, Hôtel de la Monnaie, juin-octobre 1973, avec une préface de Jean Nougayrol, Paris, Hôtel de la Monnaie, 1973.

Amiet Pierre, L'Art d'Agadé au musée du Louvre, Paris,

Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1976.

Art of the First Cities, New York, 2003, n 135.

Boehmer Rainer Michael, Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit, Berlin, W. De Gruyter und C , 1965, n 724, fig. 232.

Boehmer Rainer Michael, Das Auftreten des Wasserbüffels

in Mesopotamien in historischer Zeit und sein sumerische Bezeichnung,

ZA 64 (1974), pp. 1-19.

Clercq Louis (de), Collection de Clercq. Catalogue méthodique et raisonné. Antiquités assyriennes, cylindres orientaux, cachets, briques, bronzes,

bas-reliefs, etc., t. I, Cylindres orientaux, avec la collaboration de Joachim Menant, Paris, E. Leroux, 1888, n 46.

Collon Dominique, First Impressions : cylinder seals in the Ancient

Near-East, Londres, British museum publications, 1987, n 529.

Frankfort Henri, Cylinder Seals, Londres, 1939, pl XVIIc.

Zettler Richard L., "The Sargonic Royal Seal. A Consideration of Sealing in Mesopotamia", in Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East,Bibliotheca Mesopotamica 6, Malibu, 1977, pp. 33-39. - https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/cylinder-seal-ibni-sharrum

- Ibni-Sharrum cylinder seal shows a kneeling person with six curls of hair.Cylinder seal of Ibni-sharrum, a scribe of Shar-kali-sharri (left) and impression (right), ca. 2183–2159 B.C.; Akkadian, reign of Shar-kali-sharri, son of Naram-sin (2250 BCE).Six curls on the kneeling adorant's hair style: Numeral bhaṭa 'six' is an Indus Script cipher, rebus bhaṭa ‘furnace’; baṭa 'iron'.Hieroglyph: rã̄go ʻ buffalo bull ʼ

Rebus: Pk. raṅga 'tin' P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼOr. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼraṅgaada -- m. ʻ borax ʼ lex.Kho. (Lor.) ruṅ ʻ saline ground with white efflorescence, salt in earth ʼ *raṅgapattra ʻ tinfoil ʼ. [raṅga -- 3, páttra -- ]B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.kāṇḍam காண்டம்² kāṇṭam, n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர். துருத்திவா யதுக்கிய குங்குமக் காண் டமும் (கல்லா. 49, 16). Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘metal tools, pots and pans’ (Marathi)(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See `to be left over'. @B24310. #20851. Re (B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See `to be left over'. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) The hieroglyph clearly refers to the metal tools, pots and pans of copper. - There are some seals with clear Indus themes among Dept. of Near Eastern Antiquities collections at the Louvre in Paris, France, among them the Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum, described as "one of the most striking examples of the perfection attained by carvers in the Agade period [2350–2170 BCE]. . . . The decoration, which is characteristic of the Agade period, shows two buffaloes that have just slaked their thirst in the stream of water spurting from two vases held by two naked kneeling heroes." It belonged to Ibni-Sharrum, the scribe of King Sharkali-Sharri, who succeeded his father Naram-Sin. The caption cotinues: "The two naked, curly-headed heroes are arranged symmetrically, half-kneeling. They are both holding vases from which water is gushing as a symbol of fertility and abundance; it is also the attribute of the god of the river, Enki-Ea, of whom these spirits of running water are indeed the acolytes. Two arni, or water buffaloes, have just drunk from them. Below the scene, a river winds between the mountains represented conventionally by a pattern of two lines of scales. The central cartouche bearing an inscription is held between the buffaloes' horns." The buffalo was known to have come from ancient Indus lands by the Akkadians.The first image shows the imprint of the cylinder seal, the general Mesopotamian type of seal as opposed to the usually square stamp seals found in Indus cities. The second is the diorite cylinder seal, the negative of the pressed sealing.A second seal at the Louvre is made of steatite, the traditional Indus material, "the animal carving is similar to those found in Harappan works. The animal is a bull with no hump on its shoulders, or possibly a short-horned gaur. Its head is lowered and the body unusually elongated. As was often the case, the animal is depicted eating from a woven wicker manger."Both seals can be found in Room 8 of the Richeliu wing, Iran and Susa during the 3rd millennium BCE.Courtesy, The Louvre, Paris, respectively copyright RMN/Franck Raux and RMN/Thierry Ollivier. More at

http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/cylinder-seal-carved-elongated-bu...

Gulf type seals were used by merchants for administrative purposes. The seals were ued to record technical specifications of metal products and metal trades. All Indus Script inscriptions are metalwork catalogues.

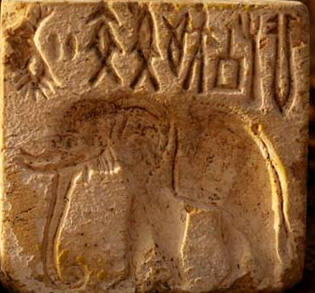

Desinamamala of Hemacandra ed. R. Pischel (1938) meḍ 'iron'(Munda); मेढ meḍh'merchant's helper'(Prakrtam) meḍho 'one who helps a merchant' (Desi) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand (Santali.Munda)  Gonur Tepe Indus Script. karibha 'trunk of elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron' Hieroglyph: ingot out of crucible: muh 'ingot' kuThAru 'crucible' rebus:kuThAru 'armourer' kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus ingot for forge. sal 'splinter'rebus: sal 'workshop' aDaren 'lid' rebus: aduru 'native metal' aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' Hieroglyph: kāmṭhiyɔ m. ʻ archer ʼ.rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coin, coiner' ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin' kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' karNaka, kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'Supercargo' karnaka 'engraver, scribe'. Gonur Tepe Indus Script. karibha 'trunk of elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron' Hieroglyph: ingot out of crucible: muh 'ingot' kuThAru 'crucible' rebus:kuThAru 'armourer' kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus ingot for forge. sal 'splinter'rebus: sal 'workshop' aDaren 'lid' rebus: aduru 'native metal' aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' Hieroglyph: kāmṭhiyɔ m. ʻ archer ʼ.rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coin, coiner' ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin' kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' karNaka, kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'Supercargo' karnaka 'engraver, scribe'.kamaṭha m. ʻ bamboo ʼ lex. 2. *kāmaṭha -- . 3. *kāmāṭṭha -- . 4. *kammaṭha -- . 5. *kammaṭṭha -- . 6. *kambāṭha -- . 7. *kambiṭṭha -- . [Cf. °bṭī, kāmīṭ, °maṭ, °mṭī, kāmṭhī, kāmāṭhī f. ʻ split piece of bamboo &c., lath ʼ.(CDIAL 2760)  These objects document long-distance contact in the MAIS: (a) an impression of an Indus “unicorn” seal thought to come from Tell Umma; (b) an Indus “unicorn” seal from Mohenjo-daro; (c) one of the seals published by Gadd (now on display in the British Museum) showing an Indus script and animal device on a Persian Gulf–style seal; and (d) the Indus elephant seal from Gonur Depe (compiled from images supplied by Maurizio Tosi, Gregory L. Possehl, and Viktor Sarianidi). These objects document long-distance contact in the MAIS: (a) an impression of an Indus “unicorn” seal thought to come from Tell Umma; (b) an Indus “unicorn” seal from Mohenjo-daro; (c) one of the seals published by Gadd (now on display in the British Museum) showing an Indus script and animal device on a Persian Gulf–style seal; and (d) the Indus elephant seal from Gonur Depe (compiled from images supplied by Maurizio Tosi, Gregory L. Possehl, and Viktor Sarianidi).  Sites across Middle Asia have revealed BMAC, or BMAC-like, artifacts (adapted from figure 10.8 in Fredrik T. Hiebert. Origins of the Bronze Age Oasis Civilization in Central Asia. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1994). Sites across Middle Asia have revealed BMAC, or BMAC-like, artifacts (adapted from figure 10.8 in Fredrik T. Hiebert. Origins of the Bronze Age Oasis Civilization in Central Asia. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1994). |

The word Meluhha used in cuneiform texts is called mleccha in Ancient Indian texts. The region of Meluhha speakers may include regions of Ancient India and also Straits of Malaka (Malacca) in the Indian Ocean. More than 2000 words of Meluhha speakers explain the readings of over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions. These inscriptions are in Meluhha hypertexts read rebus; for e.g. karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron'. Such an elephant is shown on an Indus Script seal from Gonur Tepe. It is for linguists to figure out how Meluhha word for elephant travelled in Eurasia and got used in Gonur Tepe (spelled as Gonur Depe on the map) of Bactria-Mariana Cultural Complex. With the comments of Angela Marcangonio presented in the following excerpts, it is suggested that the linguists shold re-visit their theories about the roots of Indo-European language family.

Let me cite a reference in Mahābhārata which refers to mleccha (cognate Meluhha, as a language used by Vidura and Yudhishthira): "Vaisampayana continued, 'Hearing these words, the illustrious Kunti was deeply grieved, and with her children, O bull of Bharata's race, stepped into the boat and went over the Ganges. Then leaving the boat according to the advice of Vidura, the Pandavas took with them the wealth that had been given to them (while at Varanavata) by their enemies and safely entered the deep woods. In the house of lac, however, that had been prepared for the destruction of the Pandavas, an innocent Nishada woman who had come there for some purpose, was, with her children burnt to death. And that worst of Mlechchhas, the wretched Purochana (who was the architect employed in building the house of lac) was also burnt in the conflagration. And thus were the sons of Dhirtarashtra with their counsellors deceived in their expectations. And thus also were the illustrious Pandavas, by the advice of Vidura, saved with their mother. But the people (of Varanavata) knew not of their safety. And the citizens of Varanavata, seeing the house of lac consumed (and believing the Pandavas to have been burnt to death) became exceedingly sorry. And they sent messengers unto king Dhritarashtra to represent everything that had happened. And they said to the monarch, 'Thy great end hath been achieved! Thou hast at last burnt the Pandavas to death! Thy desire fulfilled, enjoy with thy children. O king of the Kurus, the kingdom.' Hearing this, Dhritarashtra with his children, made a show of grief, and along with his relatives, including [paragraph continues] Kshattri (Vidura) and Bhishma the foremost of the Kurus, performed the last honours of the Pandavas.' (Mahābhārata, Section CXLIII,, Jatugriha Parva, pp. 302-303). The Great Epic is replete with hundreds of references to Mlecchas and mleccha speakers.![Image result for gonur bharatkalyan97]()

![Cylinder-seal of Sharkalisharri, Akkadian period (23rd century BC), Mesopotamia â made of chlorite. Credits: Louvre Musée]()

![Impression of the Sharkalisharri cylinder seal, ca. 2183- 2159 BC during Akkadian, reign of Shar-kali-sharri. Mesopotamia. Cuneiform inscription in Old Akkadian. Credits: Louvre Musée]()

![harappan seal]() Indus Script seal and impression from Gonur Tepe.

Indus Script seal and impression from Gonur Tepe.

S'adaupas'ada are also known as PaurUravasau.

9656 bhráṣṭra n. ʻ frying pan, gridiron ʼ MaitrS. [√bhrajj ] Pk. bhaṭṭha -- m.n. ʻ gridiron ʼ; K. büṭhü f. ʻ level surface by kitchen fireplace on which vessels are put when taken off fire ʼ; S. baṭhu m. ʻ large pot in which grain is parched, large cooking fire ʼ, baṭhī f. ʻ distilling furnace ʼ; L. bhaṭṭh m. ʻ grain -- parcher's oven ʼ, bhaṭṭhī f. ʻ kiln, distillery ʼ, awāṇ. bhaṭh; P. bhaṭṭh m., ˚ṭhī f. ʻ furnace ʼ, bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ; N. bhāṭi ʻ oven or vessel in which clothes are steamed for washing ʼ; A. bhaṭā ʻ brick -- or lime -- kiln ʼ; B. bhāṭi ʻ kiln ʼ; Or. bhāṭi ʻ brick -- kiln, distilling pot ʼ; Mth. bhaṭhī, bhaṭṭī ʻ brick -- kiln, furnace, still ʼ; Aw.lakh. bhāṭhā ʻ kiln ʼ; H. bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ, bhaṭ f. ʻ kiln, oven, fireplace ʼ; M. bhaṭṭā m. ʻ pot of fire ʼ, bhaṭṭī f. ʻ forge ʼ. -- X bhástrā -- q.v. bhrāṣṭra -- ; *bhraṣṭrapūra -- , *bhraṣṭrāgāra -- . Addenda: bhráṣṭra -- : S.kcch. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ʻ distil (spirits) ʼ. 9657 *bhraṣṭrapūra ʻ gridiron -- cake ʼ. [Cf. bhrāṣṭraja -- ʻ pro- duced on a gridiron ʼ lex. -- bhráṣṭra -- , pūra -- 2 ] P. bhaṭhūhar, ˚hrā, bhaṭhūrā, ˚ṭhorū m. ʻ cake of leavened bread ʼ; -- or < *bhr̥ṣṭapūra -- . 9658 *bhraṣṭrāgāra ʻ grain parching house ʼ. [bhráṣṭra -- , agāra -- ] P. bhaṭhiār, ˚ālā m. ʻ grainparcher's shop ʼ. 9684 bhrāṣṭra m. ʻ gridiron ʼ Nir., adj. ʻ cooked on a grid- iron ʼ Pāṇ., ˚ka -- m. (n.?) ʻ frying pan ʼ Pañcat. [NIA. forms all < eastern MIA. *bhāṭha -- , but like Pk. none show medial aspirate except G. with -- ḍ -- poss. < -- ḍh -- . -- bhráṣṭra -- , √bhrajj ]Pk. bhāḍa -- n. ʻ oven for parching grain ʼ; Phal. bhaṛ<-> ʻ to roast, fry ʼ (NOPhal 31 < bhr̥kta -- with ?); L. bhāṛ ʻ oven ʼ; Ku. bhāṛ ʻ iron oven, fire, furnace ʼ; Bi. bhār ʻ grain -- parcher's fireplace ʼ, (N of Ganges) bhaṛ -- bhū̃jā ʻ grain -- parcher ʼ; OAw. bhārū, pl. ˚rā m. ʻ oven, furnace ʼ; H. bhāṛ m. ʻ oven, grain -- parcher's fireplace, fire ʼ; G. bhāḍi f. ʻ oven ʼ, M. bhāḍ n.*bhrāṣṭraśālikā -- . 9685 *bhrāṣṭraśālikā ʻ furnace house ʼ. [bhrāṣṭra -- , śāˊlā -- ]H. bharsārī f. ʻ furnace, oven ʼ.

![]()

![]() "Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum, described as "one of the most striking examples of the perfection attained by carvers in the Agade period [2350–2170 BCE]. . . . The decoration, which is characteristic of the Agade period, shows two buffaloes that have just slaked their thirst in the stream of water spurting from two vases held by two naked kneeling heroes." It belonged to Ibni-Sharrum, the scribe of King Sharkali-Sharri, who succeeded his father Naram-Sin. The caption cotinues: "The two naked, curly-headed heroes are arranged symmetrically, half-kneeling. They are both holding vases from which water is gushing as a symbol of fertility and abundance; it is also the attribute of the god of the river, Enki-Ea, of whom these spirits of running water are indeed the acolytes. Two arni, or water buffaloes, have just drunk from them. Below the scene, a river winds between the mountains represented conventionally by a pattern of two lines of scales. The central cartouche bearing an inscription is held between the buffaloes' horns." The buffalo was known to have come from ancient Indus lands by the Akkadians." https://www.harappa.com/blog/indus-cylinder-seals-louvre

"Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum, described as "one of the most striking examples of the perfection attained by carvers in the Agade period [2350–2170 BCE]. . . . The decoration, which is characteristic of the Agade period, shows two buffaloes that have just slaked their thirst in the stream of water spurting from two vases held by two naked kneeling heroes." It belonged to Ibni-Sharrum, the scribe of King Sharkali-Sharri, who succeeded his father Naram-Sin. The caption cotinues: "The two naked, curly-headed heroes are arranged symmetrically, half-kneeling. They are both holding vases from which water is gushing as a symbol of fertility and abundance; it is also the attribute of the god of the river, Enki-Ea, of whom these spirits of running water are indeed the acolytes. Two arni, or water buffaloes, have just drunk from them. Below the scene, a river winds between the mountains represented conventionally by a pattern of two lines of scales. The central cartouche bearing an inscription is held between the buffaloes' horns." The buffalo was known to have come from ancient Indus lands by the Akkadians." https://www.harappa.com/blog/indus-cylinder-seals-louvre![]()

v. 406. (˚ja=khagga); Miln 149; DhsA 331.(Pali)

Parpola, Asko, 2017. Indus Seals and Glyptic Studies: An Overview. Pp. 127-147 & pl ix (& pp. 401+449 references) in: Sarah Scott & al. (eds), Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World, Cambridge: CUP.

Let me cite a reference in Mahābhārata which refers to mleccha (cognate Meluhha, as a language used by Vidura and Yudhishthira): "Vaisampayana continued, 'Hearing these words, the illustrious Kunti was deeply grieved, and with her children, O bull of Bharata's race, stepped into the boat and went over the Ganges. Then leaving the boat according to the advice of Vidura, the Pandavas took with them the wealth that had been given to them (while at Varanavata) by their enemies and safely entered the deep woods. In the house of lac, however, that had been prepared for the destruction of the Pandavas, an innocent Nishada woman who had come there for some purpose, was, with her children burnt to death. And that worst of Mlechchhas, the wretched Purochana (who was the architect employed in building the house of lac) was also burnt in the conflagration. And thus were the sons of Dhirtarashtra with their counsellors deceived in their expectations. And thus also were the illustrious Pandavas, by the advice of Vidura, saved with their mother. But the people (of Varanavata) knew not of their safety. And the citizens of Varanavata, seeing the house of lac consumed (and believing the Pandavas to have been burnt to death) became exceedingly sorry. And they sent messengers unto king Dhritarashtra to represent everything that had happened. And they said to the monarch, 'Thy great end hath been achieved! Thou hast at last burnt the Pandavas to death! Thy desire fulfilled, enjoy with thy children. O king of the Kurus, the kingdom.' Hearing this, Dhritarashtra with his children, made a show of grief, and along with his relatives, including [paragraph continues] Kshattri (Vidura) and Bhishma the foremost of the Kurus, performed the last honours of the Pandavas.' (Mahābhārata, Section CXLIII,, Jatugriha Parva, pp. 302-303). The Great Epic is replete with hundreds of references to Mlecchas and mleccha speakers.

https://tinyurl.com/ybhlynzk

"The merchants of Gonur and Central Asia could even have been the possible originators of the Silk Roads." -- K.E. Eduljee

I suggest that the settlement of Gonur Tepe was by people from Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. Parallels between Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization settlements and Gonur settlements are vivid and emphatic, apart from the commonly shared writing system of Indus Script cipher.

The fortified settlements of Gonur Tepe with citadel compare with the layout of Dholavira fortified settlement and citadel with gateway suggesting that the Dholavira artisans migrated to Gonur in search of minerals and settled there for metalwork. The evidence for metalwork of Gonur Tepe is provided by a seal with Indus Script inscription including pictorial motif of an elephant and text message of 8 hieroglyphs/hypertexts deciphered in this monograph.

![Image result for dholavira citadel]()

Dholavira. gateway. A designer's impressions (reconstruction) of the world's first signboard on the gateway of fortification or citadel.

Gonur south complex.

![Reconstruction of the Gonur south fortifications at National Museum of Turkmenistan]()

Decipherment of Gonur Tepe Indus Script inscription on seal

![Image result for gonur tepe]()

Gonur Tepe.Indus Script. Seal, Seal impression. t:

![]() This is a unique hypertext composed of a crucible PLUS a sprig. The sprig compares with the sprig inscribed on the exquisite terracotta image found at Altyn Tepe.

This is a unique hypertext composed of a crucible PLUS a sprig. The sprig compares with the sprig inscribed on the exquisite terracotta image found at Altyn Tepe.![]() Hypertext: ingot out of crucible: mũh, muhã 'ingot' Rebus: muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'.PLUS kuṭhāru 'crucible' rebus:kuṭhāru 'armourer' PLUS kolmo'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus ingot for forge. Alternative: xoli 'fish-tail' rebus: kolhe'smelter', kol '

Hypertext: ingot out of crucible: mũh, muhã 'ingot' Rebus: muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'.PLUS kuṭhāru 'crucible' rebus:kuṭhāru 'armourer' PLUS kolmo'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus ingot for forge. Alternative: xoli 'fish-tail' rebus: kolhe'smelter', kol '

![Votive figure from Altyn-Depe (the Golden Hill), Turkmenistan. Altyn-Depe is an ancient settlement of the Bronze Age (3,000 - 2,000 B.C.E.) on the territory of ancient Abiver. It's known locally as the "Turkmen Stonehenge". União Soviética.:]()

![Bronze Age Indo-Iranian Archaeological Complexes]()

![South Turkmenistan Mugrab delta and oasis]()

![Distribution of archaeological sites (in red) in the Murgab Delta]() Distribution of archaeological sites (in red)

Distribution of archaeological sites (in red)

![GAerial photo of Gonur showing both complexes]()

![Gonur south complex]()

Gonur south complex.

![Reconstruction of the Gonur south fortifications at National Museum of Turkmenistan]()

![Excavated Gonur north complex]()

![Artist's reconstruction of the Gonur north complex]() Artist's reconstruction of the Gonur north complex. Note the successive protective walls with the outer-most surrounding what appear to be dwellings.

Artist's reconstruction of the Gonur north complex. Note the successive protective walls with the outer-most surrounding what appear to be dwellings.

![Reconstruction of the Gonur north citadel at National Museum of Turkmenistan]()

![Another reconstruction of the Gonur north complex]()

Excavations at Southern Gonur, by V. Sarianidi, 1993, British Institute of Persian Studies.

» Brief History of Researches in Margiana by Museo-on

Other web articles include Discover Magazine, Anahita Gallery, Kar Po's Travel Blog, Dan & Mary's Monastery, Archaeology Online, Turkmenistan June 2006 and Stantours. Generally, we find the quality of research and reports available of the web to be poorly researched, highly speculative and sensationalistic. (Note: All citations from KE Eduljee http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/merv/gonur.htm)

Gonur excavation

![Temple building walls uncovered in Gonur-Depe]()

![Plan of Togolok 21]()

![Reconstructed model of Togolok 21]()

"The next and last shrine excavated is located in the settlement of Togolok 21, which dates to the late 2nd millennium. Taking into account its large overall size (larger than the fortress of South Gonur), it is possible that the shrine of Togolok 21 served the inhabitants of the whole country of Margiana in the late Bronze Age. Similar to the above-described shrines, there is a domestic area near Togolok 21 associated with the shrine. At Gonur depe and Togolok 1 the settlements are many times larger than the shrines, while in Togolok 21 the settlement is a great deal smaller than the shrine itself. "The shrine of Togolok 21 was built at the top of a small natural hill. Along the outer face of the exterior wall are circular and semicircular hollow towers. In the northern part of the wall are two pylons between which a central gateway, supposed to be the entrance to the shrine, is located. The second entrance was built in the middle of the southern wall. The whole inner area was not built up except at the western side where some extremely narrow rooms are located which appear to have had arched ceilings. Their purpose is unclear. Two altar sites located opposite each other in the northern part of the shrine were perhaps used for carrying out ritual ceremonies associated with libations and fire rituals." [unquote] http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/merv/gonur3.htm#sarianidi

Claims of Viktor Sarianidi about Soma-Haoma processing in Margiana refuted

[Click here for the article by Viktor Sarianidi titled Margiana and Soma-Haomapublished in the electronic Journal of Vedic Studies (EJVS) Vol. 9 (2003) Issue 1d (May 5) and with Jan E.M. Houben of Leiden University as Guest Editor. We note that Sarianidi's references do not include a single authentic Zoroastrian source even though he claims to associate certain findings with Zoroastrianism.]

According to James P. Mallory 1989 & 1997 "... remains of ephedras have also been reported from the temple-fortress complex of Togolok 21 in the Merv oasis (ancient Margiana – Parpola 1988; Meier-Melikyan 1990) along with the remains of poppies. ... In 1990 I received some samples from the site [forwarded by Dr. Fred Hiebert of Harvard University], which were subjected to pollen analysis at the Department of Botany, University of Helsinki. .... The largest amount of pollen was found in the bone tube (used for imbibing liquid?) from Gonur 1, but even in this sample, which had been preserved in a comparatively sheltered position when compared with the other investigated samples, only pollen of the family Caryophyllaceae was present. No pollen from ephedras or poppies was found and even the pollen left in the samples showed clear traces of deterioration (typical in ancient pollen having been preserved in a dry environment in contact with oxygen). Our pollen analysis was carefully checked for any methodological errors, but no inaccuracies were found."

Yet another refutation of Sarianidi's wild and unsubstantiated claims of 1. having found narcotics and 2. associating what he found is found with haoma and thereby a Zoroastrian cult (sic) ritual is found in a journal article of which Jan E.M. Houben of Leiden University, Netherlands [E. Journal of Vedic Studies Vol. 9 (2003) Issue 1c (May 5)]. [Click here for an excerpt of the article by Professor C.C. Bakels titled Report concerning the contents of a ceramic vessel found in the "white room" of the Gonur Temenos, Merv Oasis, Turkmenistan.] Bakels concludes, "The material we examined contained broomcorn millet. This cereal is known from the Merv oasis, at least from the Bronze Age onwards (Nesbitt 1997). The crop plant most probably has its origin in Central Asia, perhaps even in the Aralo-Caspian basin."

Professor Houben states, "After a few months I received messages indicating that no proof could be found of any of the substances indicated by Sarianidi. Rather than hastily sticking to this conclusion, Prof. Bakels made efforts to show the specimens to other paleobotanists whom she met at international professional meetings. At the end of this lengthy procedure, no confirmation could be given of the presence of the mentioned plants in the material that was investigated. The traces of plant-substances rather pointed in the direction of a kind of millet."

Metalwork and artifacts from Gonur

Raphael Pumpelly (1837-1923)

![]()

![Related image]()

![]() Bactria Margiana. Silver ceremonial axes.

Bactria Margiana. Silver ceremonial axes.![Image result for bactrian ax]() Bactria. Ceremonial axe. British Museum

Bactria. Ceremonial axe. British Museum![Image result for bactrian ax lion iron]()

![Image result for bactrian ax lion iron]() Iran, Luristan bronze Bridle ring with two crouching lions, ca 1200-800 BCE

Iran, Luristan bronze Bridle ring with two crouching lions, ca 1200-800 BCE![]()

![08-02-14/21 Lessing, Erich, photographer. Ceremonial axe of ki...]() Ceremonial axe (inscribed with name) of king Untash-Napirisha, from his capital Tchoga Zambil. Back of the axe adorned with an electrum boar; the blade issues from a lion's mouth. Silver and electrum, H: 5,9 cm Sb 3973 Louvre, Departement des Antiquites Orientales, Paris, France

Ceremonial axe (inscribed with name) of king Untash-Napirisha, from his capital Tchoga Zambil. Back of the axe adorned with an electrum boar; the blade issues from a lion's mouth. Silver and electrum, H: 5,9 cm Sb 3973 Louvre, Departement des Antiquites Orientales, Paris, France

Originally, this would have been fitted to a short haft, or given the large size of it, it may well have been fitted to a long shaft to make a pole arm. A decorative piece, possibly used for feng shui in a building, possibly used as a prop in Chinese opera. Made of carved hardwood with a thick red-brown lacquer finish." http://tigers-den-swords.blogspot.in/2011/09/chinese-wooden-axe-head.html![Picture]()

![Picture]()

![]()

![]() Tablet Sb04823: receipt of 5 workers(?) and their monthly(?) rations, with subscript and seal depicting animal in boat; excavated at Susa in the early 20th century; Louvre Museum, Paris (Image courtesy of Dr Jacob L. Dahl, University of Oxford) Cited in an article on Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) System. The animal in boat may be a boar and may signify supercargo of wood and iron products. baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi ‘a caste who work both in iron and wood’.

Tablet Sb04823: receipt of 5 workers(?) and their monthly(?) rations, with subscript and seal depicting animal in boat; excavated at Susa in the early 20th century; Louvre Museum, Paris (Image courtesy of Dr Jacob L. Dahl, University of Oxford) Cited in an article on Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) System. The animal in boat may be a boar and may signify supercargo of wood and iron products. baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi ‘a caste who work both in iron and wood’.

![]()

baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar'Rebus: bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [ bārakaśa or bārakasa ] n (![]()

![This idol in the form of a lock or handbag was likely carried to indicate that the bearer was of high office. This extraordinary example was found originally in several pieces. The idol is carved from grey chlorite and measures approximately 27 cm in width. One side (Top) bears two pairs of birds of prey, and the other side (Bottom) bears two tethered bulls facing each other.]()

![Bactriane - Begram - déesse fluviale en ivoire - 1er siècle avant JXC - Musée Guimet - Paris]()

![Image result for ganga makara begram bharatkalyan97]()

![Hache à talon décoré d'une tête de cheval - Bactriane fin du IIIe millénaire, début du IIe millénaire avant J.-C. | Site officiel du musée du Louvre]()

![AFGHAN ARMS AND ARMOUR 2ND-1ST MILL.BCE Ceremonial adze,from Baktria,Northern Afghanistan; end 3rd,beginning 2nd Mill.BCE. Silver and gold,maximum length 12,68 cm Collection George Ortiz, Geneva, Switzerland]()

![BACTRIAN BRONZE AXE HEAD | The narrow blade decorated with incised chevrons, cut-away socket with banded edges, the shaft decorated with two squatting figures each wearing short tunic, one wrestling a seated feline the other with arms around the feline and a standing quadruped. 2nd Millennium BC]()

![Vase tronconique à col éversé - Bactriane | Site officiel du musée du Louvre]()

![Flacon à parfum ou à cosmétique à fond mobile. Décor gravé : femme ailée sur une barque, encadrée de tulipes - Bactriane fin du IIIe millénaire, début du IIe millénaire avant J.-C. | Site officiel du musée du Louvre]()

![Bactrian Bronze Monkey Seal New York | Animals Date: 2500 BC - 1900 BC Culture: Bactrian Category: Animals, Seals & Gems Medium: Bronze]()

![A BACTRIAN COPPER ALLOY COMPARTMENTED STAMP SEAL circa late 3rd-early 2nd millennium b.c. Circular in form, the openwork figural device in the form of a caprid with curving horns standing on a groundline, a small bird on its back, a monkey in front with its hands on the caprid's neck, the back of the seal with incision detailing the figural scene, a tongue-shaped suspension loop in the center]()

![Openwork stamp seal: figure holding snakes Period: Bronze Age Date: ca. late 3rd–early 2nd millennium B.C. Geography: Bactria-Margiana Culture: Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex Medium: Copper alloy Dimensions: H. 9.1 cm]()

![Openwork stamp seal: figure holding snakes Period: Bronze Age Date: ca. late 3rd–early 2nd millennium B.C. Geography: Bactria-Margiana Culture: Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex Medium: Copper alloy]()

![]() Inscription. Altyn Depe seal.

Inscription. Altyn Depe seal.

![Image result for altyn depe seals]() Altyn-depe. Silver seal. Pictograph of ligatured animal with three heads.

Altyn-depe. Silver seal. Pictograph of ligatured animal with three heads.

![Two seals found at Altyn-depe (Excavation 9 and 7) found in the shrine and in the 'elite quarter':]() Two seals found at Altyn-depe (Excavation 9 and 7) found in the shrine and in the 'elite quarter'

Two seals found at Altyn-depe (Excavation 9 and 7) found in the shrine and in the 'elite quarter'

![Image result for bactria archaeology sword]()

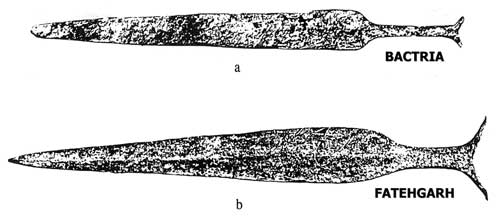

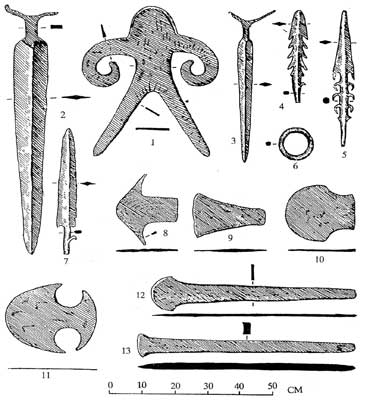

![copper]() Copper hoard including anthropomorphic figures, harpoons, shouldered axes,from Ganga valley, India. The Bactrian find of a hilted sword which compares with the sworf of Fathehgarh may thus be seen as produced by artisans from Ganga valley who migrated to Bactria.

Copper hoard including anthropomorphic figures, harpoons, shouldered axes,from Ganga valley, India. The Bactrian find of a hilted sword which compares with the sworf of Fathehgarh may thus be seen as produced by artisans from Ganga valley who migrated to Bactria.![Selected hoard artefacts from 1-2 South Haryana, 3-4 Uttar Pradesh, 5 Madhya Pradesh, 6-8 South Bihar-North Orissa-Bengalen.]() Selected hoard artefacts from 1-2 South Haryana, 3-4 Uttar Pradesh, 5 Madhya Pradesh, 6-8 South Bihar-North Orissa-Bengal. Haryana hoard artefacts are deposited in the Kanya Gurukul Museum of Narela, Haryana.(Paul Yule, The Bronze Age Metalwork of India, Prähistorische Bronzefunde XX,8 (München 1985), http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/savifadok/volltexte/2011/1895/ ).

Selected hoard artefacts from 1-2 South Haryana, 3-4 Uttar Pradesh, 5 Madhya Pradesh, 6-8 South Bihar-North Orissa-Bengal. Haryana hoard artefacts are deposited in the Kanya Gurukul Museum of Narela, Haryana.(Paul Yule, The Bronze Age Metalwork of India, Prähistorische Bronzefunde XX,8 (München 1985), http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/savifadok/volltexte/2011/1895/ ).

"The merchants of Gonur and Central Asia could even have been the possible originators of the Silk Roads." -- K.E. Eduljee

I suggest that the settlement of Gonur Tepe was by people from Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. Parallels between Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization settlements and Gonur settlements are vivid and emphatic, apart from the commonly shared writing system of Indus Script cipher.

The fortified settlements of Gonur Tepe with citadel compare with the layout of Dholavira fortified settlement and citadel with gateway suggesting that the Dholavira artisans migrated to Gonur in search of minerals and settled there for metalwork. The evidence for metalwork of Gonur Tepe is provided by a seal with Indus Script inscription including pictorial motif of an elephant and text message of 8 hieroglyphs/hypertexts deciphered in this monograph.

Dholavira. gateway. A designer's impressions (reconstruction) of the world's first signboard on the gateway of fortification or citadel.

Gonur south complex.

Reconstruction of the Gonur south fortifications at National Museum of Turkmenistan. Photo credit: Kerri-Jo Stewart at Flickr

Decipherment of Gonur Tepe Indus Script inscription on seal

Gonur Tepe.Indus Script. Seal, Seal impression. t:

Pictorial motif: karabha, ibha 'elephant, trunk of elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron', ibbo 'merchant'

sal 'splinter'rebus: sal 'workshop'

aḍaren 'lid' rebus: aduru 'native metal' PLUS aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'.

खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). Rebus:khaṇḍa 'implements' PLUS aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'. Thus, aya khaṇḍa 'excellent iron (metal) implements'.

Hieroglyph: kāmṭhiyɔ m. ʻ archer ʼ.rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coin, coiner'

ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin'

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

कर्णक karṇaka, kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'Supercargo' karṇaka 'engraver, scribe' कर्णिक, 'helmsman, steersman'; name of a people.

Votive figure from Altyn-Depe (the Golden Hill), Turkmenistan. Altyn-Depe is an ancient settlement of the Bronze Age (3,000 - 2,000 B.C.E.) on the territory of ancient Abiver. It's known locally as the "Turkmen Stonehenge". União Soviética.

I suggest that this figure has inscribed Indus Script hypertexts read rebus related to metal smelting of elements, aduru 'native metal' and metal implements work.

Hieroglyph: kola 'woman' (Nahali) rebus: kol 'working in iron'

Hieroglyph: Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native metal. Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron. (DEDR 192) Alternative 'twig': कूदी [p= 300,1] f. a bunch of twigs , bunch (v.l. कूट्/ई) AV. v , 19 , 12 Kaus3.accord. to Kaus3. , Sch. = बदरी, "Christ's thorn".Rebus: kuṭhi'smelter'.

Two hair strands signify: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS Hieroglyph strand (of hair): dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV.,ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā ]S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

Rebus: dhāvḍī 'iron smelting': Shgh. ċīw, ċōw, ċū ʻ single hair ʼ ; Ash. dro ʻ woman's hair ʼ, Kt. drū, Wg.drū, drū̃; Pr. ḍui ʻ a hair ʼ; Kho. dro(h) ʻ hair ʼ, (Lor.) ʻ hair (of animal), body hair (human) ʼ: → Orm. dra , drī IIFL i 392 (semant. cf. Psht. pal ʻ fringe of hair over forehead ʼ < *pata -- (CDIAL 6623) drava द्रव [p= 500,3] flowing , fluid , dropping , dripping , trickling or overflowing with (comp.) Ka1t2h. Mn.MBh. Ka1v. fused , liquefied , melted W. m. distilling , trickling , fluidity Bha1sha1p. dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ)(CDIAL 6773)

Hieroglyph: *mēṇḍhī ʻ lock of hair, curl ʼ. [Cf. *mēṇḍha -- 1 s.v. *miḍḍa -- ]

S. mī˜ḍhī f., °ḍho m. ʻ braid in a woman's hair ʼ, L. mē̃ḍhī f.; G. mĩḍlɔ, miḍ° m. ʻ braid of hair on a girl's forehead ʼ; M. meḍhā m. ʻ curl, snarl, twist or tangle in cord or thread ʼ.(CDIAL 10312) Ta. miṭai (-v-, -nt-) to weave as a mat, etc. Ma. miṭayuka to plait, braid, twist, wattle; miṭaccal plaiting, etc.; miṭappu tuft of hair; miṭalascreen or wicket, ōlas plaited together. Ka. meḍaṟu to plait as screens, etc. (Hav.) maḍe to knit, weave (as a basket); (Gowda) mEḍi plait. Ga.(S.3 ) miṭṭe a female hair-style. Go. (Mu.) mihc- to plait (hair) (Voc. 2850).(DEDR 4853) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Santali.Mu.Ho.)

Three lines below the belly of the figure: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

Hieroglyph: kuṭhi ‘vagina’ Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṛī f. ‘fireplace’ (H.); krvṛi f. ‘granary (WPah.); kuṛī, kuṛo house, building’(Ku.)(CDIAL 3232) kuṭi ‘hut made of boughs’ (Skt.) guḍi temple (Telugu) kuṭhi ‘a furnace for smelting iron ore to smelt iron’; kolheko kuṭhieda koles smelt iron (Santali) kuṭhi, kuṭi (Or.; Sad. koṭhi) (1) the smelting furnace of the blacksmith; kuṭire bica duljad.ko talkena, they were feeding the furnace with ore; (2) the name of ēkuṭi has been given to the fire which, in lac factories, warms the water bath for softening the lac so that it can be spread into sheets; to make a smelting furnace; kuṭhi-o of a smelting furnace, to be made; the smelting furnace of the blacksmith is made of mud, cone-shaped, 2’ 6” dia. At the base and 1’ 6” at the top. The hole in the centre, into which the mixture of charcoal and iron ore is poured, is about 6” to 7” in dia. At the base it has two holes, a smaller one into which the nozzle of the bellow is inserted, as seen in fig. 1, and a larger one on the opposite side through which the molten iron flows out into a cavity (Mundari) kuṭhi = a factory; lil kuṭhi = an indigo factory (koṭhi - Hindi) (Santali.Bodding) kuṭhi = an earthen furnace for smelting iron; make do., smelt iron; kolheko do kuṭhi benaokate baliko dhukana, the Kolhes build an earthen furnace and smelt iron-ore, blowing the bellows; tehen:ko kuṭhi yet kana, they are working (or building) the furnace to-day (H. koṭhī ) (Santali. Bodding) kuṭṭhita = hot, sweltering; molten (of tamba, cp. uttatta)(Pali.lex.) uttatta (ut + tapta) = heated, of metals: molten, refined; shining, splendid, pure (Pali.lex.) kuṭṭakam, kuṭṭukam = cauldron (Ma.); kuṭṭuva = big copper pot for heating water (Kod.)(DEDR 1668). gudgā to blaze; gud.va flame (Man.d); gudva, gūdūvwa, guduwa id. (Kuwi)(DEDR 1715). dāntar-kuṭha = fireplace (Sv.); kōti wooden vessel for mixing yeast (Sh.); kōlhā house with mud roof and walls, granary (P.); kuṭhī factory (A.); koṭhābrick-built house (B.); kuṭhī bank, granary (B.); koṭho jar in which indigo is stored, warehouse (G.); koṭhīlare earthen jar, factory (G.); kuṭhī granary, factory (M.)(CDIAL 3546). koṭho = a warehouse; a revenue office, in which dues are paid and collected; koṭhī a store-room; a factory (Gujarat) koḍ = the place where artisans work (Gujarati)

Hieroglyph: sprig: ḍāla 5546 ḍāla1 m. ʻ branch ʼ Śīl. 2. *ṭhāla -- . 3. *ḍāḍha -- . [Poss. same as *dāla -- 1 and dāra -- 1 : √dal, √d&rcirclemacr; . But variation of form supports PMWS 64 ← Mu.]1. Pk. ḍāla -- n. ʻ branch ʼ; S. ḍ̠āru m. ʻ large branch ʼ, ḍ̠ārī f. ʻ branch ʼ; P. ḍāl m. ʻ branch ʼ, °lā m. ʻ large do. ʼ, °lī f. ʻ twig ʼ; WPah. bhal. ḍām. ʻ branch ʼ; Ku. ḍālo m. ʻ tree ʼ; N. ḍālo ʻ branch ʼ, A. B. ḍāl, Or. ḍāḷa; Mth. ḍār ʻ branch ʼ, °ri ʻ twig ʼ; Aw. lakh. ḍār ʻ branch ʼ, H. ḍāl, °lām., G. ḍāḷi , °ḷī f., °ḷũ n.2. A. ṭhāl ʻ branch ʼ, °li ʻ twig ʼ; H. ṭhāl, °lā m. ʻ leafy branch (esp. one lopped off) ʼ.3. Bhoj. ḍāṛhī ʻ branch ʼ; M. ḍāhaḷ m. ʻ loppings of trees ʼ, ḍāhḷā m. ʻ leafy branch ʼ, °ḷī f. ʻ twig ʼ, ḍhāḷā m. ʻ sprig ʼ, °ḷī f. ʻ branch ʼ.*ḍāla -- 2 ʻ basket ʼ see *ḍalla -- 2 .ḍālima -- see dāḍima -- .*ḍāva -- 1 ʻ box ʼ see *ḍabba -- .*ḍāva -- 2 ʻ left ʼ see *ḍavva -- .Addenda: ḍāla -- 1 . 1. S.kcch. ḍār f. ʻ branch of a tree ʼ; WPah.kṭg. ḍāḷ m. ʻ tree ʼ, J. ḍā'l m.; kṭg. ḍaḷi f. ʻ branch, stalk ʼ, ḍaḷṭi f. ʻ shoot ʼ; A. ḍāl(phonet. d -- ) ʻ branch ʼ AFD 207.टाळा (p. 196) ṭāḷā ...2 Averting or preventing (of a trouble or an evil). 3 The roof of the mouth. 4 R (Usually टाहळा) A small leafy branch; a spray or sprig. टाळी (p. 196) ṭāḷī f R (Usually टाहळी) A small leafy branch, a sprig.ढगळा (p. 204) ḍhagaḷā m R A small leafy branch; a sprig or spray. डगळा or डघळा (p. 201) ḍagaḷā or ḍaghaḷā m A tender and leafy branch: also a sprig or spray. डांगशी (p. 202) ḍāṅgaśī f C A small branch, a sprig, a spray. डांगळी (p. 202) ḍāṅgaḷī f A small branch, a sprig or spray. डाहळा (p. 202) ḍāhaḷā लांख esp. the first. 2 (dim. डाहळी f A sprig or twig.) A leafy branch. Pr. धरायाला डाहळी न बसायाला सावली Used.

Rebus: ḍhāla 'large ingot' (Gujarati)

"This review of recent archaeological work in Central Asia and Eurasia attempts to trace and date the movements of the Indo-Iranians—speakers of languages of the eastern branch of Proto-Indo-European that later split into the Iranian and Vedic families. Russian and Central Asian scholars working on the contemporary but very different Andronovo and Bactrian Margiana archaeological complexes of the 2d millennium BCE have identified both as Indo-Iranian, and particular sites so identified are being used for nationalist purposes. There is, however, no compelling archaeological evidence that they had a common ancestor or that either is Indo-Iranian. Ethnicity and language are not easily linked with an archaeological signature, and the identity of the Indo-Iranians remains elusive." (C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky,2002, 'Archaeology and Language, The Indoiranians', in Current Anthropology, Vol. 43, No. 1, Feb. 2002 http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/324130)

Bronze Age Indo-Iranian Archaeological Complexes, west of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization

Image credit: Wikipedia "In 1976, Viktor Sarianidi proposed that the Bronze Age archaeological sites dating from c. 2200 to 1700 BCE and located in present day Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, were the remains of a connected Bronze Age civilization centered on the upper Amu Darya (Oxus). He named the complex the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) and the inhabitants of that period and region, the Oxus civilization. The name Andronovo complex comes from the village of Andronovo in Siberia where in 1914, several graves were discovered, with skeletons in crouched positions, buried with richly decorated pottery. The name has been used to refer to a set of contemporaneous Bronze Age cultures that flourished c. 2300–1000 BCE in western Siberia and the west Asiatic steppes of Kazakhstan. This culture is thought to have been a pastoral people who reared horses, cattle, sheep and goats."

Murgab delta and oasis (circled) in the south of Turkmenistan

The Murgab river spreads out and disappears into the Kara Kum desert to the north

Distribution of archaeological sites (in red)

Distribution of archaeological sites (in red)in the Murgab Delta. "The northern delta settlements include those now known as the ruins at Kelleli, Adji Kui, Taip, Gonur, and Togolok (Togoluk)...It is presumed that as the northern delta area became more dry, large metropolises like Gonur were abandoned. Further to the south, the ancient city of Mervbecame an Achaemenid era (519-331 BCE) administrative centre and perhaps even the capital of the satrapy that included Mouru. Mouru was then known to the Achaemenians as Margu(sh) and to the Greeks as Μαργιανή. Margiana is the derived English-Latin name of Margu. The Sassanian name for the region was Marv. "

Photo credit: University of BolognaSource: http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/merv/gonur.htm "The environs of Mouru, the third nation listed in the Zoroastrian scriptures, the Avesta's book of Vendidad, are generally thought to have included the Murgab river delta, that is, the region around Merv which today is a city in southern Turkmenistan. Ruins of over 150 ancient settlements dating back to the early Bronze Age (2500-1700 BCE) have been found in the Murgab delta region which covers an area of more than 3000 sq. km. and contains about 78 oases."

Aerial photo of Gonur showing two complexes of Gonur (looking almost directly north). Photo credit: Kenneth Garrett

Gonur south complex.

Reconstruction of the Gonur south fortifications at National Museum of Turkmenistan. Photo credit: Kerri-Jo Stewart at Flickr

Excavated Gonur north complex. Photo credit: Black Sands Film

Artist's reconstruction of the Gonur north complex. Note the successive protective walls with the outer-most surrounding what appear to be dwellings.

Artist's reconstruction of the Gonur north complex. Note the successive protective walls with the outer-most surrounding what appear to be dwellings.

Reconstruction of the Gonur north citadel complex at National Museum of Turkmenistan. Photo credit: Kerri-Jo Stewart at Flickr

Another reconstruction of the Gonur north complex. "A large necropolis lies to the west of the site. In the centre of the northern complex is a fortified citadel-like structure. Both complexes have fortification walls. The fortification walls of the southern complex are wide, 8 to 10 metres tall and interspaced with round towers along its sides and corners. There are residential quarters walls within the fortifications."

Reference:Excavations at Southern Gonur, by V. Sarianidi, 1993, British Institute of Persian Studies.

» Brief History of Researches in Margiana by Museo-on

Other web articles include Discover Magazine, Anahita Gallery, Kar Po's Travel Blog, Dan & Mary's Monastery, Archaeology Online, Turkmenistan June 2006 and Stantours. Generally, we find the quality of research and reports available of the web to be poorly researched, highly speculative and sensationalistic. (Note: All citations from KE Eduljee http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/merv/gonur.htm)

Gonur excavation

So-called Temple(?) building walls with three narrow rooms to the left

being uncovered in Gonur-Depe "In the photograph of the excavated rooms of the "temple" shown above right, the larger room has a circular foundation which the Turkmenistan new agency article describes as a "furnace" with an inner and outer chamber. The inner chamber contained burnt material presumably residue of the fuel used but which the article does not identify. The article further notes that pots found in the vicinity of the building had an internal lining that made them waterproof, thereby making them capable of holding liquids."

Plan of Togolok 21. Photo credit: various. Kispesti Kozert

Reconstructed model of Togolok 21

Photo credit:Aula Didactica [quote]According to Viktor Sarianidi:

"The next and last shrine excavated is located in the settlement of Togolok 21, which dates to the late 2nd millennium. Taking into account its large overall size (larger than the fortress of South Gonur), it is possible that the shrine of Togolok 21 served the inhabitants of the whole country of Margiana in the late Bronze Age. Similar to the above-described shrines, there is a domestic area near Togolok 21 associated with the shrine. At Gonur depe and Togolok 1 the settlements are many times larger than the shrines, while in Togolok 21 the settlement is a great deal smaller than the shrine itself. "The shrine of Togolok 21 was built at the top of a small natural hill. Along the outer face of the exterior wall are circular and semicircular hollow towers. In the northern part of the wall are two pylons between which a central gateway, supposed to be the entrance to the shrine, is located. The second entrance was built in the middle of the southern wall. The whole inner area was not built up except at the western side where some extremely narrow rooms are located which appear to have had arched ceilings. Their purpose is unclear. Two altar sites located opposite each other in the northern part of the shrine were perhaps used for carrying out ritual ceremonies associated with libations and fire rituals." [unquote] http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/merv/gonur3.htm#sarianidi

Claims of Viktor Sarianidi about Soma-Haoma processing in Margiana refuted

[Click here for the article by Viktor Sarianidi titled Margiana and Soma-Haomapublished in the electronic Journal of Vedic Studies (EJVS) Vol. 9 (2003) Issue 1d (May 5) and with Jan E.M. Houben of Leiden University as Guest Editor. We note that Sarianidi's references do not include a single authentic Zoroastrian source even though he claims to associate certain findings with Zoroastrianism.]

According to James P. Mallory 1989 & 1997 "... remains of ephedras have also been reported from the temple-fortress complex of Togolok 21 in the Merv oasis (ancient Margiana – Parpola 1988; Meier-Melikyan 1990) along with the remains of poppies. ... In 1990 I received some samples from the site [forwarded by Dr. Fred Hiebert of Harvard University], which were subjected to pollen analysis at the Department of Botany, University of Helsinki. .... The largest amount of pollen was found in the bone tube (used for imbibing liquid?) from Gonur 1, but even in this sample, which had been preserved in a comparatively sheltered position when compared with the other investigated samples, only pollen of the family Caryophyllaceae was present. No pollen from ephedras or poppies was found and even the pollen left in the samples showed clear traces of deterioration (typical in ancient pollen having been preserved in a dry environment in contact with oxygen). Our pollen analysis was carefully checked for any methodological errors, but no inaccuracies were found."

Yet another refutation of Sarianidi's wild and unsubstantiated claims of 1. having found narcotics and 2. associating what he found is found with haoma and thereby a Zoroastrian cult (sic) ritual is found in a journal article of which Jan E.M. Houben of Leiden University, Netherlands [E. Journal of Vedic Studies Vol. 9 (2003) Issue 1c (May 5)]. [Click here for an excerpt of the article by Professor C.C. Bakels titled Report concerning the contents of a ceramic vessel found in the "white room" of the Gonur Temenos, Merv Oasis, Turkmenistan.] Bakels concludes, "The material we examined contained broomcorn millet. This cereal is known from the Merv oasis, at least from the Bronze Age onwards (Nesbitt 1997). The crop plant most probably has its origin in Central Asia, perhaps even in the Aralo-Caspian basin."

Professor Houben states, "After a few months I received messages indicating that no proof could be found of any of the substances indicated by Sarianidi. Rather than hastily sticking to this conclusion, Prof. Bakels made efforts to show the specimens to other paleobotanists whom she met at international professional meetings. At the end of this lengthy procedure, no confirmation could be given of the presence of the mentioned plants in the material that was investigated. The traces of plant-substances rather pointed in the direction of a kind of millet."

Metalwork and artifacts from Gonur

Gonur's Exquisite Artefacts

[quote] The quality, artistry and workmanship of the artefacts unearthed at Gonur has surprised observers. They include intricate jewellery and metalwork incorporating gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and carnelian.

|

| Necklace with carnelian obsidian beads found in the necropolis at Gonur. Carnelian is a hard reddish translucent semiprecious gemstone that is a variety of chalcedony, a form of banded quartz. Obsidian is a jet-black volcanic glass, chemically similar to granite and formed by the rapid cooling of molten lava. Photo credit: Anna Garner at Flickr. The beads are now part of Anna Garner's collection. |

|

| Pin with camel ornament. Photo credit: Katy Tzaralunga at Flickr |

|

| Fine containers. Photo credit: Katy Tzaralunga at Flickr |

|

| Artistic wall decorations(?). Photo credit: Katy Tzaralunga at Flickr |

The prowess of the Gonur metalworkers - who used tin alloys and delicate combinations of gold and silver - were on par with the skills of their more famous contemporaries in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley. Their creations display a rich repertoire of geometric designs, mythic monsters, and other creatures. Among them are striking humanoid statues with small heads and wide skirts, as well as horses, lions, snakes, and scorpions.

|

|

| A rich find of pottery at Gonur. Photo credit: josephescu at Flickr |

|

| Seal of the type found and used in the Indus Valley |

Gold and other metals are not found in the region. The lapis lazuli likely came from the Badakshan mountains that are now in the northwest of Afghanistan.

Wares in this distinctive style had long been found in regions far and near. As close as Gonur's southern neighbour Balkh in today's Afghanistan, and as far as Mesopotamia to the west, the shores of the Persian Gulf to the south, the Russian steppes to the north, and to the southeast across the Hindu Kush - the great cities of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, which once flourished on the banks of the Indus River in today's Pakistan.

Archaeologists had long puzzled over the origin of the fine artefacts found in the Indus Valley and in the distant lands - artefacts made from materials not native to those areas. The Gonur excavations provide one possible answer: that the items originated in the region around Gonur. For the artefacts to have spread to lands thousands of kilometres apart indicate the presence of an active trade network consisting of artisans, traders, merchants, an extensive road network and possibly even bazaars. It is conceivable that the hub of the network was Central Asia and that Gonur lay at its heart. The merchants of Gonur and Central Asia could even have been the possible originators of the Silk Roads.

That all of this together in an advanced urban setting supported by an irrigated agricultural system was already developed and functioning in the Bronze Age (2500-1700 BCE) is astounding.

Wares in this distinctive style had long been found in regions far and near. As close as Gonur's southern neighbour Balkh in today's Afghanistan, and as far as Mesopotamia to the west, the shores of the Persian Gulf to the south, the Russian steppes to the north, and to the southeast across the Hindu Kush - the great cities of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, which once flourished on the banks of the Indus River in today's Pakistan.

Archaeologists had long puzzled over the origin of the fine artefacts found in the Indus Valley and in the distant lands - artefacts made from materials not native to those areas. The Gonur excavations provide one possible answer: that the items originated in the region around Gonur. For the artefacts to have spread to lands thousands of kilometres apart indicate the presence of an active trade network consisting of artisans, traders, merchants, an extensive road network and possibly even bazaars. It is conceivable that the hub of the network was Central Asia and that Gonur lay at its heart. The merchants of Gonur and Central Asia could even have been the possible originators of the Silk Roads.

That all of this together in an advanced urban setting supported by an irrigated agricultural system was already developed and functioning in the Bronze Age (2500-1700 BCE) is astounding.

...

Age, People & Culture

Prof. Fredrik Hiebert of the Univ. of Pennsylvania (who during the 1988-89 field season, excavated part of Gonur in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture of Turkmenistan and the Institute of Archaeology in Moscow), in his book Origins of the Bronze Age Oasis Civilization in Central Asia (Harvard University Press, 2004) writes on page 2:

"The archaeology of Margiana is fundamentally tied into the Kopet Dag foothill chronological framework of the Namazga culture (see note 1). Of prime importance has been the association of the monumental architecture in Margiana with numerous miniature stone columns, steatite bowls, bronze seals, and stone amulets. None of the materials of these objects is locally available (see note 2), yet they have a style distinctive to the desert oases of Margiana and Bactria. The oasis sites have provided the first known cultural context for the Bactrian-Margiana Archaeological Complex."

After earlier independent work by Soviet archaeologists that would have included Viktor Sarianidi, Hiebert worked with Sarianidi, an effort that resulted in a change of previous conclusions. Hiebert writes, "This study is based on collaborative excavations conducted by V. Sarianidi and myself (our note: misplaced reflective pronoun "myself" here – should be the object pronoun "me") at the Bronze Age site of Gonur Depe in Margiana. It is proposed that the rapid occupation of sites in the Murgab delta oasis was contemporary with the Namazga V settlement in the foothill region, which was the period of largest urban settlement at the site of Altyn Depe (see note 3). The present study proposes that the Bactrian-Margiana Archaeological Complex developed from local traditions at the beginning of the second millennium (our note: say 2,000 – 1,600 BCE see note 4). In contrast to previously suggested reconstructions of the origins of the Bactrian-Margiana Archaeological Complex, I show that this development does not result from migrations from Iran, South Asia, or Mesopotamia, nor from the sedentarization of nomads (see note 5).

"The diverse geography and natural resources of Central Asia form a framework for the pattern of human settlement. The differential development of culture in the areas of oasis and foothill plain is largely due to this diversity of environments.

"The archaeological context of the Bronze Age sites of Margiana is special, in that very little post-Bronze Age architectural remains are preserved just below the surface. The area is highly deflated, leaving little more than the ground plan and a small amount of deposit just above the floors. These have been cleared over wide areas, exposing entire building complexes."

"the oasis regions of ancient Bactria and Margiana developed their own artistic tradition on stone and metal artefacts despite the lack of natural resources on which they were made."

Note (general): It seems the Margians imported the raw material of the artefacts in main part from their southern Arian neighbours, the Bactrians and others, and then fashioned the artefacts for domestic use and export for the artefacts are reported to have been found in the Indus Valley. This activity points to a shared understanding between the Arian nations, a network of roads that connected them and policed to assure safe passage of the travellers, knowledge of tools suitable to work with the properties of different materials, and craft shops if not small factories. Aryan society would have had to be fairly complex, with agriculture supported by a network of canals, cities supported by a water and sewage distribution network, architects, builders of buildings and infrastructure, traders, administrators, a military and laws to govern society and keep the peace.

Note 1: Namazga or Namazgah (meaning prayer-place, "ga" is a contraction of "gah" meaning place) is a Bronze Age archaeological site in Turkmenistan, some 100 km from Ashgabat, near the Iranian border. Numbers in Roman numerals beside the name indicate the age of an excavation layer (at times settlements were rebuilt on top of previous ones). Namazgah IV is dated around 2,500 BCE, V to around 2,000-1,600 BCE, and VI to around 1,600-1,000 BCE.

Note 2: This phenomenon of the discovery of materials not native to an area is a common denominator of the various nations of Ancient Aryana who actively traded amongst themselves.

Note 3: Namazga(h) V is dated to around 2,500 BCE. An article (1989 updated 2011) by V. M. Mason at Iranica states, "The excavations (at Altyn Depe) show continuous development of an early agricultural culture from the 5th to the early 2nd millennium BCE Though a settlement of the Neolithic Jaitun culture (6th millennium BCE) is situated nearby… in the 4th millennium B.C. the inhabited area of Altyn Tepe increased to 12 hectares… at the end of the 4th to the early 3rd millennium B.C., Altyn Tepe covered 25 hectares, acquiring the character of a large inhabited center… Altyn Tepe reached its most flourishing stage at the end of the 3rd-early 2nd millennium B.C. (complex of the Namazga V type), when it was a settlement of the early urban type."

Note 4. Hiebert notes on page 2, "The previous radiocarbon dates from Margiana and from other areas of Central Asia have provided unsatisfactory results for archaeologists." (Hiebert's) "chronology is based primarily on a new series of radiocarbon dates, which came from the Margiana excavations, both from my own excavations and from previous excavations."

The residents of Gonur did not, however, materialize from nowhere. They were residents of the area who built Gonur. We do not know if any lower excavation layers have been found.

Note 5: Saka and Turkic migrations occurred later – after Alexander’s invasion and subsequent occupation weakened the infrastructure. Nomadic raids from the north were constant – thus the fortifications. The raids were for plunder and not for settlement (the nomads had no interest in settling and working for a living).

According to Discover Magazine, "Fredrik Hiebert, a young American graduate student, learned Russian, visited Gonur in 1988, and then a few years later returned with his Harvard adviser, Lamberg-Karlovksy. A team of Italians followed to dig at nearby sites and to examine Gonur's extensive cemetery." [unquote]

"The archaeology of Margiana is fundamentally tied into the Kopet Dag foothill chronological framework of the Namazga culture (see note 1). Of prime importance has been the association of the monumental architecture in Margiana with numerous miniature stone columns, steatite bowls, bronze seals, and stone amulets. None of the materials of these objects is locally available (see note 2), yet they have a style distinctive to the desert oases of Margiana and Bactria. The oasis sites have provided the first known cultural context for the Bactrian-Margiana Archaeological Complex."

After earlier independent work by Soviet archaeologists that would have included Viktor Sarianidi, Hiebert worked with Sarianidi, an effort that resulted in a change of previous conclusions. Hiebert writes, "This study is based on collaborative excavations conducted by V. Sarianidi and myself (our note: misplaced reflective pronoun "myself" here – should be the object pronoun "me") at the Bronze Age site of Gonur Depe in Margiana. It is proposed that the rapid occupation of sites in the Murgab delta oasis was contemporary with the Namazga V settlement in the foothill region, which was the period of largest urban settlement at the site of Altyn Depe (see note 3). The present study proposes that the Bactrian-Margiana Archaeological Complex developed from local traditions at the beginning of the second millennium (our note: say 2,000 – 1,600 BCE see note 4). In contrast to previously suggested reconstructions of the origins of the Bactrian-Margiana Archaeological Complex, I show that this development does not result from migrations from Iran, South Asia, or Mesopotamia, nor from the sedentarization of nomads (see note 5).

"The diverse geography and natural resources of Central Asia form a framework for the pattern of human settlement. The differential development of culture in the areas of oasis and foothill plain is largely due to this diversity of environments.

"The archaeological context of the Bronze Age sites of Margiana is special, in that very little post-Bronze Age architectural remains are preserved just below the surface. The area is highly deflated, leaving little more than the ground plan and a small amount of deposit just above the floors. These have been cleared over wide areas, exposing entire building complexes."

"the oasis regions of ancient Bactria and Margiana developed their own artistic tradition on stone and metal artefacts despite the lack of natural resources on which they were made."

Note (general): It seems the Margians imported the raw material of the artefacts in main part from their southern Arian neighbours, the Bactrians and others, and then fashioned the artefacts for domestic use and export for the artefacts are reported to have been found in the Indus Valley. This activity points to a shared understanding between the Arian nations, a network of roads that connected them and policed to assure safe passage of the travellers, knowledge of tools suitable to work with the properties of different materials, and craft shops if not small factories. Aryan society would have had to be fairly complex, with agriculture supported by a network of canals, cities supported by a water and sewage distribution network, architects, builders of buildings and infrastructure, traders, administrators, a military and laws to govern society and keep the peace.

Note 1: Namazga or Namazgah (meaning prayer-place, "ga" is a contraction of "gah" meaning place) is a Bronze Age archaeological site in Turkmenistan, some 100 km from Ashgabat, near the Iranian border. Numbers in Roman numerals beside the name indicate the age of an excavation layer (at times settlements were rebuilt on top of previous ones). Namazgah IV is dated around 2,500 BCE, V to around 2,000-1,600 BCE, and VI to around 1,600-1,000 BCE.

Note 2: This phenomenon of the discovery of materials not native to an area is a common denominator of the various nations of Ancient Aryana who actively traded amongst themselves.

Note 3: Namazga(h) V is dated to around 2,500 BCE. An article (1989 updated 2011) by V. M. Mason at Iranica states, "The excavations (at Altyn Depe) show continuous development of an early agricultural culture from the 5th to the early 2nd millennium BCE Though a settlement of the Neolithic Jaitun culture (6th millennium BCE) is situated nearby… in the 4th millennium B.C. the inhabited area of Altyn Tepe increased to 12 hectares… at the end of the 4th to the early 3rd millennium B.C., Altyn Tepe covered 25 hectares, acquiring the character of a large inhabited center… Altyn Tepe reached its most flourishing stage at the end of the 3rd-early 2nd millennium B.C. (complex of the Namazga V type), when it was a settlement of the early urban type."

Note 4. Hiebert notes on page 2, "The previous radiocarbon dates from Margiana and from other areas of Central Asia have provided unsatisfactory results for archaeologists." (Hiebert's) "chronology is based primarily on a new series of radiocarbon dates, which came from the Margiana excavations, both from my own excavations and from previous excavations."

The residents of Gonur did not, however, materialize from nowhere. They were residents of the area who built Gonur. We do not know if any lower excavation layers have been found.

Note 5: Saka and Turkic migrations occurred later – after Alexander’s invasion and subsequent occupation weakened the infrastructure. Nomadic raids from the north were constant – thus the fortifications. The raids were for plunder and not for settlement (the nomads had no interest in settling and working for a living).

According to Discover Magazine, "Fredrik Hiebert, a young American graduate student, learned Russian, visited Gonur in 1988, and then a few years later returned with his Harvard adviser, Lamberg-Karlovksy. A team of Italians followed to dig at nearby sites and to examine Gonur's extensive cemetery." [unquote]

Raphael Pumpelly (1837-1923)

Champion of a Central Asian Cradle of Civilization

|

| Raphael Pumpelly |

More than a century ago an unlikely geologist from New York put forth a proposition that "the fundamentals of civilization - organized village life, agriculture, the domestication of animals, weaving," (including mining and metal work) "originated in the oases of Central Asia long before the time of Babylon."