Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/hemysju

See: Rakhigarhi cylinder seal:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/perforated-plaques-of-tello-lagash.html

![]() Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral' śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ.rebus: seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master (Pali) sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'.

Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral' śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ.rebus: seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master (Pali) sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'.

The Tale of Sea Goddess of Lothal

![]()

![]()

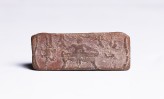

Triangular prism seal EAMd 13 kana, kanac = corner (Santali); Rebus: kañcu ..'bronze' kamaDha 'bow and arrow' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage' bhaTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron, copper' karNika 'legs spread' rebus: karNI 'Supercargo' kamaDha 'penance' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage/' ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' kharA 'crocodile' rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' khuṭo ʻleg, footʼ, °ṭī ʻgoat's legʼ; Nepalese. khuṭo ʻleg, footʼ(CDIAL 3894).Rebus: khoTa 'ingot' (See the bovine hoofed legs of platform of the seated person).

![]()

![Photograph courtesy of Toshiki Osada]()

![]()

![]()

See: Rakhigarhi cylinder seal:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/perforated-plaques-of-tello-lagash.html

Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral' śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ.rebus: seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master (Pali) sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'.

Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral' śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ.rebus: seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master (Pali) sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'.Sign 186 *śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ. [Cf. śrētr̥ -- ʻ one who has recourse to ʼ MBh. -- See śrití -- . -- √śri]Ash. ċeitr ʻ ladder ʼ (< *ċaitr -- dissim. from ċraitr -- ?).(CDIAL 12720)*śrēṣṭrī2 ʻ line, ladder ʼ. [For mng. ʻ line ʼ conn. with √śriṣ2 cf. śrḗṇi -- ~ √śri. -- See śrití -- . -- √śriṣ2]Pk. sēḍhĭ̄ -- f. ʻ line, row ʼ (cf. pasēḍhi -- f. ʻ id. ʼ. -- < EMIA. *sēṭhī -- sanskritized as śrēḍhī -- , śrēṭī -- , śrēḍī<-> (Col.), śrēdhī -- (W.) f. ʻ a partic. progression of arithmetical figures ʼ); K. hēr, dat. °ri f. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 12724) Rebus: śrḗṣṭha ʻ most splendid, best ʼ RV. [śrīˊ -- ]Pa. seṭṭha -- ʻ best ʼ, Aś.shah. man. sreṭha -- , gir. sesṭa -- , kāl. seṭha -- , Dhp. śeṭha -- , Pk. seṭṭha -- , siṭṭha -- ; N. seṭh ʻ great, noble, superior ʼ; Or. seṭha ʻ chief, principal ʼ; Si. seṭa, °ṭu ʻ noble, excellent ʼ. śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ]Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ, seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M. śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2?)(CDIAL 12725, 12726)

The Tale of Sea Goddess of Lothal

March 30th, 2016 From the air Lothal may seem like a scratch in the fields, but for the people around it, the original excavator S.K. Rao of the site had this to say: "Ravages of nature and man have been responsible for the destruction of brick structures built at the foot of the mound. What little remains is hidden under a thick deposit of silt. It is relevant to record here a local tradition regarding Lothal, which is considered a sacred place for Vanuvatimata, the sea-goddess who is represented by stones placed in a small enclosure of bricks built in the south-east corner of the mound. It is here that a warehouse stood in Harappan times. . . . Before extending the operations to this sector the stones in worship representing the sea-goddess had to be removed against the wishes of the labourers. A few days later there was an accident resulting in injury to some labourers and the death of one of them. Immediately the workers attributed the accident to the sacrilege committed by us in removing the goddess from her original place or worship, and refused to work on the site. They were later satisfied when the goddess was re-installed elsewhere with some ceremony. This incident is particularly mentioned here to show how strong is the tradition of worshipping the sea-goddess of Lothal. It is necessary to note here that the original seat of the goddess was the warehouse-mound over-looking the dock. She is invoked even now to protext the saiors from the dangers of the sea." (S.K. Rao, Lothal, 1979, p. 21)The image on the top left is of the Harsidhhi Mataji Idol at Rajpipla, Gujarat, where the original Parmara rulers of Rajpipla, Gujarat (about 200 km from Lothal), who migrated from Ujjain and brought her as Kuladevi. another name for Vanuvatimata, the Happy Mother, also known as the Sindhoi Mata or Goddess of Sands, more at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harsidhhihttps://www.harappa.com/blog/tale-sea-goddess-lothal

March 30th, 2016

From the air Lothal may seem like a scratch in the fields, but for the people around it, the original excavator S.K. Rao of the site had this to say: "Ravages of nature and man have been responsible for the destruction of brick structures built at the foot of the mound. What little remains is hidden under a thick deposit of silt. It is relevant to record here a local tradition regarding Lothal, which is considered a sacred place for Vanuvatimata, the sea-goddess who is represented by stones placed in a small enclosure of bricks built in the south-east corner of the mound. It is here that a warehouse stood in Harappan times. . . . Before extending the operations to this sector the stones in worship representing the sea-goddess had to be removed against the wishes of the labourers. A few days later there was an accident resulting in injury to some labourers and the death of one of them. Immediately the workers attributed the accident to the sacrilege committed by us in removing the goddess from her original place or worship, and refused to work on the site. They were later satisfied when the goddess was re-installed elsewhere with some ceremony. This incident is particularly mentioned here to show how strong is the tradition of worshipping the sea-goddess of Lothal. It is necessary to note here that the original seat of the goddess was the warehouse-mound over-looking the dock. She is invoked even now to protext the saiors from the dangers of the sea." (S.K. Rao, Lothal, 1979, p. 21)

The image on the top left is of the Harsidhhi Mataji Idol at Rajpipla, Gujarat, where the original Parmara rulers of Rajpipla, Gujarat (about 200 km from Lothal), who migrated from Ujjain and brought her as Kuladevi. another name for Vanuvatimata, the Happy Mother, also known as the Sindhoi Mata or Goddess of Sands, more at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harsidhhi

https://www.harappa.com/blog/tale-sea-goddess-lothalKalibangan

March 28th, 2016

March 28th, 2016

"The site Kalibangan - literally 'black bangles' - derives its name for the dense distribution of the fragments of black bangles which were found at the surface of its mounds. . ." writes Madhu Bala. "Evidence of this period consists of a citadel area over the 1.6 metre-thick early Harappan deposit in KLB-1 (the western mound of the site [Image 1]), a chessboard pattern 'lower city' in KLB-2 (the lower and larger eastern mound), and a mound full of fire altars in a much smaller mound further east (KLB-3).

The citadel complex of KLB-1 is roughly a parallelogram (240 by 120 metres) divided into two equal parts with a partition wall and surrounded by a rampart with bastions and salients. The basil width of the fortification wall is 3-7 metres. The wall is made of mud bricks in a ration of 4:2:1, with mud plaster on both the inner and outer faces. The southern half of the citadel had ceremonial platforms and fire altars.

Fire altars were also built in residences where a room was apparently earmarked for them [Image 2]. The altars were renewed from time to time as the general level of the site became higher.

There were two entrances to the Kalibangan citadel complex, one to the north and the other to the south. The southern entrance has a brick structure about 2.6 metres wide with oblong salients on both sides of the step of the entrance. The northern structure has a mud brick staircase. The northern half of the citadel area complex had a street, and housed the elite. In the southern half fire altars were arranged in a row on top of platforms constructed for this purpose. Stairs provided access to the top, and the ground around the platforms was paved with bricks.

The lower city (KLB-2) was also fortified and laid out in a chessboard pattern, and built of mud bricks of the standard 4:2:1 proportion. The basis shape is that of a parallelogram measuring 235 x 360 metres. The basal width of the fortification wall is 3.5-9 metres. The streets run north - south and east -–west, dividing the area into blocks, and are connected to lanes. There were mud brick rectangular platforms by the side of the roads. Wooden fender posts were intended to ward off damage to street corners. House drains of mud brick and wood discharged into jars in the streets, above the ground. In some areas the streets were paved with terracotta nodules.

The lower city had entrances on the northern and western sides. Each house consisted of six or seven rooms, with a courtyard or a corridor between the rooms. Some rooms were paved with tiles bearing designs.

KLB-3, the isolated easternmost mound, has brought to the surface a row of fire altars, and this find, along with the remains of fire altars in KLB-1 mentioned above is clear evidence that fire altars played a major role in the religious life of the people."

"Interesting evidence regarding cooking practices is revealed by the presence of both underground and overground varieties of mud ovens inside the houses [Image 4]. These ovens closely resemble the present-day tandoors in the region of Rajasthan and Panjab. The underground variety was made with a slight overhang near the mouth, while the overground ovens were given a bridged side opening for feeding fuel and were plastered periodically. The ovens were perhaps used for baking bread, as the Kalibangan residents were mainly wheat eaters. The wheat grains were most likely stored in cylindrical pits lined with lime plaster, which have been discovered at the site."(Kalibangan: Its Period and Antiquities, p. 34, 39, 40-41 in Indus Civilization Sites in India New Discoveriesedited by Dilip Chakrabarti, Marg Publications, Mumbai, 2004).1. Kalibangan reconstructed image of the citadel and lower town. Computer illustration: Sushi Misal.

2. Kalibangan: Harappan fire altars.

3. Kalibangan gold objects, early Harappan period.

4. Kalibangan KLB-1: two ovens.All photographs courtesy The Archaeological Survey of India.

https://www.harappa.com/blog/kalibangan

"The site Kalibangan - literally 'black bangles' - derives its name for the dense distribution of the fragments of black bangles which were found at the surface of its mounds. . ." writes Madhu Bala. "Evidence of this period consists of a citadel area over the 1.6 metre-thick early Harappan deposit in KLB-1 (the western mound of the site [Image 1]), a chessboard pattern 'lower city' in KLB-2 (the lower and larger eastern mound), and a mound full of fire altars in a much smaller mound further east (KLB-3).

The citadel complex of KLB-1 is roughly a parallelogram (240 by 120 metres) divided into two equal parts with a partition wall and surrounded by a rampart with bastions and salients. The basil width of the fortification wall is 3-7 metres. The wall is made of mud bricks in a ration of 4:2:1, with mud plaster on both the inner and outer faces. The southern half of the citadel had ceremonial platforms and fire altars.

Fire altars were also built in residences where a room was apparently earmarked for them [Image 2]. The altars were renewed from time to time as the general level of the site became higher.

There were two entrances to the Kalibangan citadel complex, one to the north and the other to the south. The southern entrance has a brick structure about 2.6 metres wide with oblong salients on both sides of the step of the entrance. The northern structure has a mud brick staircase. The northern half of the citadel area complex had a street, and housed the elite. In the southern half fire altars were arranged in a row on top of platforms constructed for this purpose. Stairs provided access to the top, and the ground around the platforms was paved with bricks.

The lower city (KLB-2) was also fortified and laid out in a chessboard pattern, and built of mud bricks of the standard 4:2:1 proportion. The basis shape is that of a parallelogram measuring 235 x 360 metres. The basal width of the fortification wall is 3.5-9 metres. The streets run north - south and east -–west, dividing the area into blocks, and are connected to lanes. There were mud brick rectangular platforms by the side of the roads. Wooden fender posts were intended to ward off damage to street corners. House drains of mud brick and wood discharged into jars in the streets, above the ground. In some areas the streets were paved with terracotta nodules.

The lower city had entrances on the northern and western sides. Each house consisted of six or seven rooms, with a courtyard or a corridor between the rooms. Some rooms were paved with tiles bearing designs.

KLB-3, the isolated easternmost mound, has brought to the surface a row of fire altars, and this find, along with the remains of fire altars in KLB-1 mentioned above is clear evidence that fire altars played a major role in the religious life of the people."

"Interesting evidence regarding cooking practices is revealed by the presence of both underground and overground varieties of mud ovens inside the houses [Image 4]. These ovens closely resemble the present-day tandoors in the region of Rajasthan and Panjab. The underground variety was made with a slight overhang near the mouth, while the overground ovens were given a bridged side opening for feeding fuel and were plastered periodically. The ovens were perhaps used for baking bread, as the Kalibangan residents were mainly wheat eaters. The wheat grains were most likely stored in cylindrical pits lined with lime plaster, which have been discovered at the site."

The citadel complex of KLB-1 is roughly a parallelogram (240 by 120 metres) divided into two equal parts with a partition wall and surrounded by a rampart with bastions and salients. The basil width of the fortification wall is 3-7 metres. The wall is made of mud bricks in a ration of 4:2:1, with mud plaster on both the inner and outer faces. The southern half of the citadel had ceremonial platforms and fire altars.

Fire altars were also built in residences where a room was apparently earmarked for them [Image 2]. The altars were renewed from time to time as the general level of the site became higher.

There were two entrances to the Kalibangan citadel complex, one to the north and the other to the south. The southern entrance has a brick structure about 2.6 metres wide with oblong salients on both sides of the step of the entrance. The northern structure has a mud brick staircase. The northern half of the citadel area complex had a street, and housed the elite. In the southern half fire altars were arranged in a row on top of platforms constructed for this purpose. Stairs provided access to the top, and the ground around the platforms was paved with bricks.

The lower city (KLB-2) was also fortified and laid out in a chessboard pattern, and built of mud bricks of the standard 4:2:1 proportion. The basis shape is that of a parallelogram measuring 235 x 360 metres. The basal width of the fortification wall is 3.5-9 metres. The streets run north - south and east -–west, dividing the area into blocks, and are connected to lanes. There were mud brick rectangular platforms by the side of the roads. Wooden fender posts were intended to ward off damage to street corners. House drains of mud brick and wood discharged into jars in the streets, above the ground. In some areas the streets were paved with terracotta nodules.

The lower city had entrances on the northern and western sides. Each house consisted of six or seven rooms, with a courtyard or a corridor between the rooms. Some rooms were paved with tiles bearing designs.

KLB-3, the isolated easternmost mound, has brought to the surface a row of fire altars, and this find, along with the remains of fire altars in KLB-1 mentioned above is clear evidence that fire altars played a major role in the religious life of the people."

"Interesting evidence regarding cooking practices is revealed by the presence of both underground and overground varieties of mud ovens inside the houses [Image 4]. These ovens closely resemble the present-day tandoors in the region of Rajasthan and Panjab. The underground variety was made with a slight overhang near the mouth, while the overground ovens were given a bridged side opening for feeding fuel and were plastered periodically. The ovens were perhaps used for baking bread, as the Kalibangan residents were mainly wheat eaters. The wheat grains were most likely stored in cylindrical pits lined with lime plaster, which have been discovered at the site."

(Kalibangan: Its Period and Antiquities, p. 34, 39, 40-41 in Indus Civilization Sites in India New Discoveriesedited by Dilip Chakrabarti, Marg Publications, Mumbai, 2004).

1. Kalibangan reconstructed image of the citadel and lower town. Computer illustration: Sushi Misal.

2. Kalibangan: Harappan fire altars.

3. Kalibangan gold objects, early Harappan period.

4. Kalibangan KLB-1: two ovens.

2. Kalibangan: Harappan fire altars.

3. Kalibangan gold objects, early Harappan period.

4. Kalibangan KLB-1: two ovens.

All photographs courtesy The Archaeological Survey of India.

The 3 L Area Mohenjodaro Statues

February 22nd, 2016![]()

February 22nd, 2016

Surkotada: reconstructed citadel

March 8th, 2016

March 8th, 2016

The Chimaera: Revisited

Growing in a Foreign World: For a History of the "Meluha Villages" in Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millenium BCE

Reconstructing the History of Harappan Civilization

https://www.harappa.com/content/reconstructing-history-harappan-civilization

Perspectives from the Indus: Contents of Interaction in the Late Harappan/Post-Urban Period

An examination of region variability, interactions and trade of the Harappan peoples.

Regional Diversity in the Harappan World: The Evidence of the Seals

August 28th, 2014

August 28th, 2014

Corner of Southern steps of Bath, showing recesses of wooden trades.

From the southern steps of the Great Bath showing recesses for wooden treads and stairways to platforms of some among the 700 wells in Mohenjo-daro, glimpses of where the ancient Indus people trod every day."A curious feature of the two stairways leading down into the bath is the presence of a channel 9.25 inches wide and 3.25 inches deep, running parallel with and at the based of the lowest step of each. This channel penetrates into the two sides of each stairway for a distance of 3.5 inches.At either end of each tread there is a recess of the same width as the tread and 3.25 inches high and deep (Plate XXVI, a [image 1]). Traces of bitumen were found in most of these holes, and wise of the stairways with a bituminous cement. ... That the covering of wood for the steps was conemplation from the first is evidenced by the holes at either end and the channel for timber at the base being part of the original design and not cut later."

(Ernest Mackay, SD Area, in Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, p. 133).https://www.harappa.com/blog/stairways-mohenjo-daro

From the southern steps of the Great Bath showing recesses for wooden treads and stairways to platforms of some among the 700 wells in Mohenjo-daro, glimpses of where the ancient Indus people trod every day.

"A curious feature of the two stairways leading down into the bath is the presence of a channel 9.25 inches wide and 3.25 inches deep, running parallel with and at the based of the lowest step of each. This channel penetrates into the two sides of each stairway for a distance of 3.5 inches.

At either end of each tread there is a recess of the same width as the tread and 3.25 inches high and deep (Plate XXVI, a [image 1]). Traces of bitumen were found in most of these holes, and wise of the stairways with a bituminous cement. ... That the covering of wood for the steps was conemplation from the first is evidenced by the holes at either end and the channel for timber at the base being part of the original design and not cut later."

(Ernest Mackay, SD Area, in Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, p. 133).

https://www.harappa.com/blog/stairways-mohenjo-daro(Ernest Mackay, SD Area, in Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, p. 133).

The Buffalo Sacrifice

March 21st, 2016

Asko Parpola writes: "Early Harappan cultures started moving toward the east and south in about 3000 BCE, and later waves of influence in these same directions came from the Indus civilization. That the Harappan water-buffalo cult [Fig. 2, 3] had reached penninsular India by the late Harappan on Chalcolithic times is suggested by the large bronze sculpture of water buffalo [Fig. 4] discovered in 1974 in a hoard at Daimabad, the southernmost Indus site in Maharashtra. Throughout south India, until relatively recently, village goddesses have been worshipped through water-buffalo sacrifices. The goddesses have been associated with a male deity call the "buffalo king," represented by a wooden post or a pillar made of stone, or by the pipal tree (Biardeau 2000).

In the form of worship at Kannapuram, a south India village in Tamil Nadu studied by Brenda Beck (1981), the tree-truck (known as kampam in Tamil, from Sanskrit skambha ("pillar") in front of which the sacrificial buffaloes are decapitated, is said to be the husband of the goddess. At the end of the annual marriage rite, after the last victim has been slaughtered, this trunk is uprooted and the goddess divested of her ornaments like a widow. The pillar and its uprooting correspond to Siva's phallus and its castration. The sacrificial post used to be burned after the divine marriage festival."

Later Parpola continues: "If the buffalo sacrifice is common in south Indian village religion, it is absent from north Indian village religion. The reason is probably the conscious efforts of Vedic Brahmans to eradicate it. Extravagant buffalo sacrifices were at first adopted by the Rigvedic Aryans in the Indus Valley (RV 5,29,7-8 etc.), but thereafter this mode of worship is not heard of. In the later Vedic literature (to Varuna) is mentioned in only a single context, in a list of hundreds of different animals offered as subsidiary victims in the horse sacrifice. It appears that generally speaking , the Brahmins have been fighting against bloody sacrifices from Rigvedic times onwards. In the Rigveda, the cow is called aghnya, "not to be slain," and while the Grhyasutra rules (apparently reflecting the behavioral code of the Atharavavedic India-Aryans) include the slaughter of a cow when a guest of honor is received, a later rule leaves it to the guest to decide whether this is done or the cow is set free. The Brahamana and Srautasutra texts record, even mentioning the names of the Brahmins concerned, how in the Vedic sacrifices human, horse, and other animal victims were successively discontinued, and a final rule says the proscribed victims should be made out of rice and barley paste."

Asko Parpola, The Roots of Hinduism, pp. 175-176, p. 178.

1. Plano convex molded tablet showing an individual spearing a water buffalo with one foot pressing the head down and one arm holding the tip of a horn. A gharial is depicted above the sacrifice scene and a figure seated in yogic position, wearing a horned headdress, looks on. The horned headdress has a branch with three prongs or leaves emerging from the center.

2. A water buffalo, 31cm high and 25 cm long, standing on a platform attached to four solid wheels. One of four bronze scultprues weighing together over 60 kg, found in a hoard at Daimabad, Maharashtra, the southernmost Indus site, and ascribed to the Late Harappan or Chalcolithic period. Photo Asko Parpola.

3. The four-faced "Proto-Shiva" seated on a throne and surrounded by four animals on the seal M-304 (DK 5175, NMI 143) from Mohenjo-daro in the collection of the National Museum of India, New Delhi. Image Courtesy Columbia University

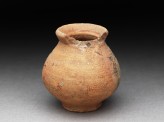

4. Water buffalo on painted pots of the Early Harappan Kot DIji culture. (a) A pot excavated at Kot Diji. After Khan 1965:68, fig. 16. Courtesy DAMGP. (b) A pot imported to the Northern Neolithic site of Burzahom in Kashmir, period II. After Kaw 1989:88, fig. 7. Courtesy ASI.

March 21st, 2016

Asko Parpola writes: "Early Harappan cultures started moving toward the east and south in about 3000 BCE, and later waves of influence in these same directions came from the Indus civilization. That the Harappan water-buffalo cult [Fig. 2, 3] had reached penninsular India by the late Harappan on Chalcolithic times is suggested by the large bronze sculpture of water buffalo [Fig. 4] discovered in 1974 in a hoard at Daimabad, the southernmost Indus site in Maharashtra. Throughout south India, until relatively recently, village goddesses have been worshipped through water-buffalo sacrifices. The goddesses have been associated with a male deity call the "buffalo king," represented by a wooden post or a pillar made of stone, or by the pipal tree (Biardeau 2000).

In the form of worship at Kannapuram, a south India village in Tamil Nadu studied by Brenda Beck (1981), the tree-truck (known as kampam in Tamil, from Sanskrit skambha ("pillar") in front of which the sacrificial buffaloes are decapitated, is said to be the husband of the goddess. At the end of the annual marriage rite, after the last victim has been slaughtered, this trunk is uprooted and the goddess divested of her ornaments like a widow. The pillar and its uprooting correspond to Siva's phallus and its castration. The sacrificial post used to be burned after the divine marriage festival."

Later Parpola continues: "If the buffalo sacrifice is common in south Indian village religion, it is absent from north Indian village religion. The reason is probably the conscious efforts of Vedic Brahmans to eradicate it. Extravagant buffalo sacrifices were at first adopted by the Rigvedic Aryans in the Indus Valley (RV 5,29,7-8 etc.), but thereafter this mode of worship is not heard of. In the later Vedic literature (to Varuna) is mentioned in only a single context, in a list of hundreds of different animals offered as subsidiary victims in the horse sacrifice. It appears that generally speaking , the Brahmins have been fighting against bloody sacrifices from Rigvedic times onwards. In the Rigveda, the cow is called aghnya, "not to be slain," and while the Grhyasutra rules (apparently reflecting the behavioral code of the Atharavavedic India-Aryans) include the slaughter of a cow when a guest of honor is received, a later rule leaves it to the guest to decide whether this is done or the cow is set free. The Brahamana and Srautasutra texts record, even mentioning the names of the Brahmins concerned, how in the Vedic sacrifices human, horse, and other animal victims were successively discontinued, and a final rule says the proscribed victims should be made out of rice and barley paste."

Asko Parpola, The Roots of Hinduism, pp. 175-176, p. 178.

1. Plano convex molded tablet showing an individual spearing a water buffalo with one foot pressing the head down and one arm holding the tip of a horn. A gharial is depicted above the sacrifice scene and a figure seated in yogic position, wearing a horned headdress, looks on. The horned headdress has a branch with three prongs or leaves emerging from the center.

2. A water buffalo, 31cm high and 25 cm long, standing on a platform attached to four solid wheels. One of four bronze scultprues weighing together over 60 kg, found in a hoard at Daimabad, Maharashtra, the southernmost Indus site, and ascribed to the Late Harappan or Chalcolithic period. Photo Asko Parpola.

3. The four-faced "Proto-Shiva" seated on a throne and surrounded by four animals on the seal M-304 (DK 5175, NMI 143) from Mohenjo-daro in the collection of the National Museum of India, New Delhi. Image Courtesy Columbia University

4. Water buffalo on painted pots of the Early Harappan Kot DIji culture. (a) A pot excavated at Kot Diji. After Khan 1965:68, fig. 16. Courtesy DAMGP. (b) A pot imported to the Northern Neolithic site of Burzahom in Kashmir, period II. After Kaw 1989:88, fig. 7. Courtesy ASI.

In the form of worship at Kannapuram, a south India village in Tamil Nadu studied by Brenda Beck (1981), the tree-truck (known as kampam in Tamil, from Sanskrit skambha ("pillar") in front of which the sacrificial buffaloes are decapitated, is said to be the husband of the goddess. At the end of the annual marriage rite, after the last victim has been slaughtered, this trunk is uprooted and the goddess divested of her ornaments like a widow. The pillar and its uprooting correspond to Siva's phallus and its castration. The sacrificial post used to be burned after the divine marriage festival."

Later Parpola continues: "If the buffalo sacrifice is common in south Indian village religion, it is absent from north Indian village religion. The reason is probably the conscious efforts of Vedic Brahmans to eradicate it. Extravagant buffalo sacrifices were at first adopted by the Rigvedic Aryans in the Indus Valley (RV 5,29,7-8 etc.), but thereafter this mode of worship is not heard of. In the later Vedic literature (to Varuna) is mentioned in only a single context, in a list of hundreds of different animals offered as subsidiary victims in the horse sacrifice. It appears that generally speaking , the Brahmins have been fighting against bloody sacrifices from Rigvedic times onwards. In the Rigveda, the cow is called aghnya, "not to be slain," and while the Grhyasutra rules (apparently reflecting the behavioral code of the Atharavavedic India-Aryans) include the slaughter of a cow when a guest of honor is received, a later rule leaves it to the guest to decide whether this is done or the cow is set free. The Brahamana and Srautasutra texts record, even mentioning the names of the Brahmins concerned, how in the Vedic sacrifices human, horse, and other animal victims were successively discontinued, and a final rule says the proscribed victims should be made out of rice and barley paste."

Asko Parpola, The Roots of Hinduism, pp. 175-176, p. 178.

1. Plano convex molded tablet showing an individual spearing a water buffalo with one foot pressing the head down and one arm holding the tip of a horn. A gharial is depicted above the sacrifice scene and a figure seated in yogic position, wearing a horned headdress, looks on. The horned headdress has a branch with three prongs or leaves emerging from the center.

2. A water buffalo, 31cm high and 25 cm long, standing on a platform attached to four solid wheels. One of four bronze scultprues weighing together over 60 kg, found in a hoard at Daimabad, Maharashtra, the southernmost Indus site, and ascribed to the Late Harappan or Chalcolithic period. Photo Asko Parpola.

3. The four-faced "Proto-Shiva" seated on a throne and surrounded by four animals on the seal M-304 (DK 5175, NMI 143) from Mohenjo-daro in the collection of the National Museum of India, New Delhi. Image Courtesy Columbia University

4. Water buffalo on painted pots of the Early Harappan Kot DIji culture. (a) A pot excavated at Kot Diji. After Khan 1965:68, fig. 16. Courtesy DAMGP. (b) A pot imported to the Northern Neolithic site of Burzahom in Kashmir, period II. After Kaw 1989:88, fig. 7. Courtesy ASI.

New Harappan site found in Botad village

- Vadodara: Archaeologists from MS University have come across another Harappan site in Gujarat in Vejalka village in Ranpur taluka of Botad district of Saurashtra, about 50km from the famous site at Lothal near Ahmedabad.Recently, a team of students and teachers from university's Department of Archaeology and Ancient History carried out excavations at the village which revealed that the rural hinterland of Saurashtra had a settlement belonging to Indus Vally civilization period around 4,300 years ago. There are over 190 Harappan sites, mainly in Saurahstra and Kutch region."This is primarily a rural site of the Harappan civilization (urban center). It is important to study the civilization's rural economy without which the urban economy could have never existed and hence we had carried out excavations at Vejalka," said head of the department professor K Krishnan, who led the excavation team."The artifacts obtained from various places in the village date back to 2,300 BC to 2,000 BC.

During the excavation, we explored various materials. We found a large number of pottery, animal bones, mud walls, beads and antiquities from this village," said Krishnan adding that it will take two more years to complete the ongoing project.He further said that the list of antiquities comprising of beads and stone blades suggest that apart from human settlement, there was also a small scale industry. "Researches say that in those days, houses were made of mud.

http://www.nyoooz.com/vadodara/424641/new-harappan-site-found-in-botad-village

The Mandi Hoard

April 4th, 2016

"The discovery of a rich hoard of Harappan jewelry from the village of Mandi (29-26 degrees 10' North, 77 degrees 34-35'E) in Muzzaffarnagar district, western Uttar Pradesh, has surprised the archaeological world for several reasons. First, Mandi is located to the east of the Yamuna river, and this area has been considered peripheral to the main distribution area of the Harappan civilization. Second, the sheer quantity of the jewellery recovered from the site makes it the largest hoard of ancient jewellry ever found in India, if not the entire subcontinent. About 10 kilograms of this jewellery has so far reached the government," writes Rakesh Tiwari."The discovery was made in a village field belonging to Anil, son of Satpat Jat in the last week of May 2000 in the course of a levelling operation (5). When the villagers learnt of the discovery, they began a hunt for more jewellery, which continued for four or five days and led to fights. Meanwhile, news of this discovery reached the Circle Officer (CO) of Police, Sadar, on June 1 through an informer. He directed a team from the Titavi police station to make inquiries of Mandi. The police found the villagers still fighting among themselves for jewellery at the site. One villager was arrested; the others ran away. Thereafter, the police collected pieces of jewellery mixed with soil from the site, and kept the cache sealed for the night. The CO and the Sub-divisional Magistrate reached the spot on June 2 to verify the facts and found a large crowd gathered there, a few still searching through the soil. On their arrival the crowd gradually dispersed . . .. Subsequently, the DM, Muzzaffarnagar gave ninety percent of the material kept at the treasury to the ASI [Archaeological Survey of India] and to the State Museum, Lucknow."

"The material kept in the treasury consists of two copper containers, and a large number of beads made of gold, banded agate, onyx and copper (1). One of the containers is a large bowl with convex sides and flat base. Its radius is about 21 centimetres and its internal and external depths are 14.8 and 15.3 centimetres respectively. The second container is rectangular in shape, 47.5, 9.5, and 4.5 centimetres in length, width, and inner depth respectively.

The gold beads are of four types - spacer beads, hollow terminal beads, single and double bell-shaped beads, and paper thin circular beads.

Space beads with either straight or segmented sides are of different sizes: 3 x 1, 3 x 0.5, 2.5 x 0.5, and 1.8 x 0.4 centimetres (2). On the basis of the number of holes they possess, these beads may be further divided into four sub-groups. Seventeen beads have been found with two holes, four with three holes, fifteen with four holes, and one with six holes.

Hollow terminal beads are presented by eighteen specimens (4). Their measurements vary between 3 x 2 and 2.2 x 1.9 centimetres. Two beads of a particular size were possibly meant to be used in one necklace, so these eighteen hollow terminal beads indicate nine necklaces. . ..

Beads from the Mandi hoard are comparable to those from various sites of the Harappan civilization."

1. Part of the Mandi hoard, kept in the Treasury, Government of UP.

2. Spacer Beads

3. Beads, Agate

4. Hollow terminal beads, gold.

5. General View of the findspot of the Mandi hoard.

(Rakesh Tilwari, A Recently Discovered Hoard of Harappan Jewelry from Western Uttar Pradesh in Indus Civilization Site in India New Discoveries (2004), Ed. Dilip K. Chakrabarti, pp. 57-63. Photographs courtesy UP State Archaeology Department.

"The material kept in the treasury consists of two copper containers, and a large number of beads made of gold, banded agate, onyx and copper (1). One of the containers is a large bowl with convex sides and flat base. Its radius is about 21 centimetres and its internal and external depths are 14.8 and 15.3 centimetres respectively. The second container is rectangular in shape, 47.5, 9.5, and 4.5 centimetres in length, width, and inner depth respectively.

The gold beads are of four types - spacer beads, hollow terminal beads, single and double bell-shaped beads, and paper thin circular beads.

Space beads with either straight or segmented sides are of different sizes: 3 x 1, 3 x 0.5, 2.5 x 0.5, and 1.8 x 0.4 centimetres (2). On the basis of the number of holes they possess, these beads may be further divided into four sub-groups. Seventeen beads have been found with two holes, four with three holes, fifteen with four holes, and one with six holes.

Hollow terminal beads are presented by eighteen specimens (4). Their measurements vary between 3 x 2 and 2.2 x 1.9 centimetres. Two beads of a particular size were possibly meant to be used in one necklace, so these eighteen hollow terminal beads indicate nine necklaces. . ..

Beads from the Mandi hoard are comparable to those from various sites of the Harappan civilization."

1. Part of the Mandi hoard, kept in the Treasury, Government of UP.

2. Spacer Beads

3. Beads, Agate

4. Hollow terminal beads, gold.

5. General View of the findspot of the Mandi hoard.

(Rakesh Tilwari, A Recently Discovered Hoard of Harappan Jewelry from Western Uttar Pradesh in Indus Civilization Site in India New Discoveries (2004), Ed. Dilip K. Chakrabarti, pp. 57-63. Photographs courtesy UP State Archaeology Department.

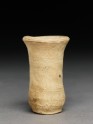

Ivory Counters from Mohenjo-daro

April 8th, 2016

"Bone and ivory counters with circles and lines, carved in ways that do not correspond to dice, may have been used for predicting the future," writes Mark Kenoyer about these objects in Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization (p. 120). The counter on the right has a duck ornament at one end, the counter on the left has a double duck ornament on the end. The larger one may be a stylized figurine with triple circle motifs incised on both faces.

What do you think these objects were used for?

What do you think these objects were used for?

A Unicorn Seal from Mesopotamia

March 17th, 2015

A perfectly cut unicorn seal with a sign right above the horn. The seal was found in ancient Kish, Iraq, during excavations between 1922 and 1933 by the Oxford-Field Museum (Chicago) Expedition. The year is given at approximately 2000 BCE, when craftsmanship in seal manufacture could have been at its height.

This artifact is one of many unicorn seals from the Indus Valley people.

This artifact is one of many unicorn seals from the Indus Valley people.

Is the Indus script indeed not a writing system?

Broken steatite mold carved into a unique fan-shape discovered in Harappa in 2001.

In 2008, Dr. Parpola published an updated second paper addressing the controversial Dr. Steve Farmer et. al thesis that the Indus script is actually not a writing system. It originally appeared as part of a felicitations volume in honor of Iravatham Mahadevan published in Chennai, India.

In 2008, Dr. Parpola published an updated second paper addressing the controversial Dr. Steve Farmer et. al thesis that the Indus script is actually not a writing system. It originally appeared as part of a felicitations volume in honor of Iravatham Mahadevan published in Chennai, India.

'Hind Leg' + 'Fish': Towards Further Understanding of the Indus Script

An inscribed and baked steatite tablet in the shape of a fish found at Harappa in 2000.

Methods and results of a systematic attempt to decipher the Indus script as a logo-syllabic writing system with Proto-Dravidian as the underlying language are first outlined. Then one so far undeciphered sign is interpreted as depicting an ungulate’s ‘hind leg.’ A phonetic reading is proposed on the basis of its onetime occurrence in front of the plain ‘fish’ sign. (Besides the plain ‘fish’ sign, there are ‘fish’ signs modified by the addition of various ‘diacritics,’ such as a ‘roof’ placed over the fish, a horizontal or diagonal line crossing the fish in the middle, etc.) The sequence ‘hind leg’ + ‘fish’ is likely to represent a compound name of a heavenly body like several other already deciphered sequences, where the latter member of the compound is Proto-Dravidian *miin ‘star,’ homophonous with *miin ‘fish.’ A probable solution (to be tested by a study of other occurrences of the ‘hind leg’ sign) is offered by Old Tamil taaL ‘leg,’ which is once attested as denoting an asterism. Finally, some inconclusive in-depth attempts to decipher other undeciphered signs are recorded. Their purpose is to highlight difficulties due to the scantiness of early Dravidian lexical and textual material.

'Hind Leg' + 'Fish': Towards Further Understanding of the Indus Script was first published in Scripta, Volume I (Sept. 2009) by the Hunmin jeongeum Society.

Methods and results of a systematic attempt to decipher the Indus script as a logo-syllabic writing system with Proto-Dravidian as the underlying language are first outlined. Then one so far undeciphered sign is interpreted as depicting an ungulate’s ‘hind leg.’ A phonetic reading is proposed on the basis of its onetime occurrence in front of the plain ‘fish’ sign. (Besides the plain ‘fish’ sign, there are ‘fish’ signs modified by the addition of various ‘diacritics,’ such as a ‘roof’ placed over the fish, a horizontal or diagonal line crossing the fish in the middle, etc.) The sequence ‘hind leg’ + ‘fish’ is likely to represent a compound name of a heavenly body like several other already deciphered sequences, where the latter member of the compound is Proto-Dravidian *miin ‘star,’ homophonous with *miin ‘fish.’ A probable solution (to be tested by a study of other occurrences of the ‘hind leg’ sign) is offered by Old Tamil taaL ‘leg,’ which is once attested as denoting an asterism. Finally, some inconclusive in-depth attempts to decipher other undeciphered signs are recorded. Their purpose is to highlight difficulties due to the scantiness of early Dravidian lexical and textual material.

'Hind Leg' + 'Fish': Towards Further Understanding of the Indus Script was first published in Scripta, Volume I (Sept. 2009) by the Hunmin jeongeum Society.

Introduction to Study of the Indus Script

Terra cotta sealing from Mohenjo-daro

In 2004 Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat (University of Illinois) and Michael Witzel (Harvard University) stunned the world of ancient Indus scholarship with the claim that the Indus sign system was not writing (their joint paper, The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization can be found on Dr. Farmer's website). Their work received widespread publicity, even in popular science magazines. They based their reasoning on computer analysis of Indus sign properties apparently not in common with other ancient written languages. The lack of lengthy inscriptions common to other early written languages is another major factor in their argument.

A target of their critique was the work of Dr. Asko Parpola (University of Helsinki, website) who - like a number of other ancient Indus "decipherments" in the past century - had concluded that the Indus sign system represented an ancient Dravidian language. Like the Jesuit priest Father Heras in the 1930s, he proposed (to the layman, rather convincingly) that the fish sign represented the word min, (pronounced meen) which designates both fish and star in most Dravidian languages. Dr. Parpola and his team's further "decipherments" based on the fish sign and old Tamil words for heavenly bodies seem to fit (to the layman, again) very nicely with words designating Venus, Saturn, the Pleaides, and other astral entities. The stars and heavenly signs were important to ancient peoples everywhere, especially ones who built economies on maritime navigation. Although it is not possible to test his interpretations, it would not be surprising if some of them are close to the truth. Still, important scholars like Gregory Possehl (University of Pennsylvania) do not accept Dr. Parpola's interpretations, while others like Indian and early Tamil expert Iravatham Mahadevan add to them. Something as clear as a definitive Rosetta stone for the ancient Indus language still eludes archaeologists. Nonetheless the discovery in the spring of 2006 of Indus signs on a hand-axe in the southern India state of Tamil Nadu could increase the probability that the ancient Indus signs are related to the Dravidian language family. Until this apparent discovery, there was no clear physical evidence for such a link.

Dr. Parpola's work also stems from a deep knowledge of Bronze Age ancient Mesopotamian civilizations. Some of the largest world trade ever must have taken place between Indus and Mesopotamian merchants during the heyday of these urban civilizations around 2350 BCE. (Discussion of this trade by Massimo Vidale (Centro Scavi IsIAO) and Dennys Frenez (University of Bologna) will be featured on on this website in the coming years.) Then there are the further discoveries in recent years of adjacent cultures between the Euphrates and Indus, like the Bactria Margiana Architectural Complex (BMAC) civilization of central Asia and Afghanistan and the city of Jiroft in southwestern Iran at the edge of the Indus plateau. Ancient human history from Turkey to India was international long before the global economy.

All these entitites traded with each other. The birth of signs or writing on stamp seals to designate ownership of goods is intertwined with the rise of early cities. To assume that other cultures with whom the Indus people traded were writing on stamp seals but the ancient Indus people were not seems slightly improbable. The objective of the seals and the symbols on them was to facilitate efficient communication across cultures.

Dr. Parpola's work is also rigorously informed by the early Vedic Hindu tradition that followed the ancient Indus civilization after around 1700-1500 BCE. Some of his interpretations, like the link between the gods Rudra and Shiva, continue the linkages to later Hindu traditions.

Nonetheless, to simply equate the Vedic and Indus cultures is wrong. The debate around the myth of an Aryan invasion of India is remarkable for its two-dimensionality. Largely south Indian Dravidian and largely North Indian or Indo-European languages have different origins. While there is no evidence for a single physical invasion of India by Indo-European language speakers, the steady growth of Indo-European language speakers through migration at the fringes and even into the heartland of Indus civilization is possible and needs archaeological and bioanthropological research. Proto-Dravidian languages are thought by some scholars to have originated on the Iranian plateau in 3500 B.C., almost two thousand miles from where Tamil is spoken in modern South India. Other scholars suggest that they emerged indigenously in peninsular India. Analogously, Indians speak English today without being considered "European." People who attach race, political and religous agendas to ancient Indus studies miss the point.

Study of the Indus Script was first delivered as a lecture in Japan by Dr. Parpola in the summer of 2005 and has been updated since. It contains a response to the Farmer et. al paper. For someone new to the subject, it summarizes key issues and facts about the ancient Indus interpretations. It presents the cornerstones of Parpola's interpretation. It is a milestone in a lifetime of research from someone who has studied this puzzle in ancient communication longer and more deeply than anyone else.

As an essay, as the literary critic George Lukacs might say, it casts an ultraviolet light on its subject.

In 2004 Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat (University of Illinois) and Michael Witzel (Harvard University) stunned the world of ancient Indus scholarship with the claim that the Indus sign system was not writing (their joint paper, The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization can be found on Dr. Farmer's website). Their work received widespread publicity, even in popular science magazines. They based their reasoning on computer analysis of Indus sign properties apparently not in common with other ancient written languages. The lack of lengthy inscriptions common to other early written languages is another major factor in their argument.

A target of their critique was the work of Dr. Asko Parpola (University of Helsinki, website) who - like a number of other ancient Indus "decipherments" in the past century - had concluded that the Indus sign system represented an ancient Dravidian language. Like the Jesuit priest Father Heras in the 1930s, he proposed (to the layman, rather convincingly) that the fish sign represented the word min, (pronounced meen) which designates both fish and star in most Dravidian languages. Dr. Parpola and his team's further "decipherments" based on the fish sign and old Tamil words for heavenly bodies seem to fit (to the layman, again) very nicely with words designating Venus, Saturn, the Pleaides, and other astral entities. The stars and heavenly signs were important to ancient peoples everywhere, especially ones who built economies on maritime navigation. Although it is not possible to test his interpretations, it would not be surprising if some of them are close to the truth. Still, important scholars like Gregory Possehl (University of Pennsylvania) do not accept Dr. Parpola's interpretations, while others like Indian and early Tamil expert Iravatham Mahadevan add to them. Something as clear as a definitive Rosetta stone for the ancient Indus language still eludes archaeologists. Nonetheless the discovery in the spring of 2006 of Indus signs on a hand-axe in the southern India state of Tamil Nadu could increase the probability that the ancient Indus signs are related to the Dravidian language family. Until this apparent discovery, there was no clear physical evidence for such a link.

Dr. Parpola's work also stems from a deep knowledge of Bronze Age ancient Mesopotamian civilizations. Some of the largest world trade ever must have taken place between Indus and Mesopotamian merchants during the heyday of these urban civilizations around 2350 BCE. (Discussion of this trade by Massimo Vidale (Centro Scavi IsIAO) and Dennys Frenez (University of Bologna) will be featured on on this website in the coming years.) Then there are the further discoveries in recent years of adjacent cultures between the Euphrates and Indus, like the Bactria Margiana Architectural Complex (BMAC) civilization of central Asia and Afghanistan and the city of Jiroft in southwestern Iran at the edge of the Indus plateau. Ancient human history from Turkey to India was international long before the global economy.

All these entitites traded with each other. The birth of signs or writing on stamp seals to designate ownership of goods is intertwined with the rise of early cities. To assume that other cultures with whom the Indus people traded were writing on stamp seals but the ancient Indus people were not seems slightly improbable. The objective of the seals and the symbols on them was to facilitate efficient communication across cultures.

Dr. Parpola's work is also rigorously informed by the early Vedic Hindu tradition that followed the ancient Indus civilization after around 1700-1500 BCE. Some of his interpretations, like the link between the gods Rudra and Shiva, continue the linkages to later Hindu traditions.

Nonetheless, to simply equate the Vedic and Indus cultures is wrong. The debate around the myth of an Aryan invasion of India is remarkable for its two-dimensionality. Largely south Indian Dravidian and largely North Indian or Indo-European languages have different origins. While there is no evidence for a single physical invasion of India by Indo-European language speakers, the steady growth of Indo-European language speakers through migration at the fringes and even into the heartland of Indus civilization is possible and needs archaeological and bioanthropological research. Proto-Dravidian languages are thought by some scholars to have originated on the Iranian plateau in 3500 B.C., almost two thousand miles from where Tamil is spoken in modern South India. Other scholars suggest that they emerged indigenously in peninsular India. Analogously, Indians speak English today without being considered "European." People who attach race, political and religous agendas to ancient Indus studies miss the point.

Study of the Indus Script was first delivered as a lecture in Japan by Dr. Parpola in the summer of 2005 and has been updated since. It contains a response to the Farmer et. al paper. For someone new to the subject, it summarizes key issues and facts about the ancient Indus interpretations. It presents the cornerstones of Parpola's interpretation. It is a milestone in a lifetime of research from someone who has studied this puzzle in ancient communication longer and more deeply than anyone else.

As an essay, as the literary critic George Lukacs might say, it casts an ultraviolet light on its subject.

Button Seal

February 26th, 2016

Fired steatite button seal with four concentric circle designs from the Trench 54 area found at Harappa in 2000 (H2000-4432/2174-3). Although seals have a very specific function that involves the stamping of a design or motif on another material, they also represent a unique aspect of graphic design in the Indus civilization. Many of the designs and motifs seen on seals have links to earlier pottery motifs and petroglyphic carvings that date to earlier periods. The Indus Seals: An Overview of Iconography and Style, an article by Mark Kenoyer explores the many types of seals.

https://www.harappa.com/blog/button-seal dhāu 'strand of rope' Rebus: dhāv 'red ore' (ferrite) ti-dhāu 'three strands' ...

https://www.scribd.com/doc/314260388/Indus-Seals-an-overview-of-iconography-and-style-Kenoyer-JM-2009 Ancient Sindh Annual Journal of Research Vol. 9 2006-7, 2009

https://www.scribd.com/doc/314260388/Indus-Seals-an-overview-of-iconography-and-style-Kenoyer-JM-2009 Ancient Sindh Annual Journal of Research Vol. 9 2006-7, 2009

https://www.scribd.com/doc/314263878/Indus-Components-in-the-Iconography-of-a-White-Marble-Cylinder-Seal-from-Konar-Sandal-South-Kerman-Iran-Massimo-Vidale-and-Dennys-Frenez-2015 South Asian Studies, 31:1, 2015, pp 144-154,

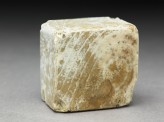

Rare White Marble Cylinder Seal from Jiroft

April 13th, 2015

The first part of the article summarizes what we know about the Jiroft civilization so far, its apparent origins in the late 5th millennium BCE, how it flourished at the height of the Indus civilization, and the tantalizing facts about connections between the two. Could it have been the ancient nation and state of Marhashi/Parahshum about which so little is known but which would have been at the cross-roads of so many cultures? What could have been the function of these so-called whorl seals, only found so far here, at Mohenjo-daro, Allahdino and Kalibangan?

Cylinder seal photograph courtesy of Halil Rud Archaeological Project. Paper first published in April 2015 in South Asian Studies.

Cylinder seal photograph courtesy of Halil Rud Archaeological Project. Paper first published in April 2015 in South Asian Studies.

https://www.harappa.com/blog/rare-white-marble-cylinder-seal-jiroft

poLa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: poLa 'magnetite ferrite ore'

![]()

poLa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: poLa 'magnetite ferrite ore'

Kot Diji Phase Button Seal

April 4th, 2015

This seal plays an illustrative role in Asko Parpola's essay Beginnings of Indian Astronomy with Reference to a Parallel Development in China. He writes "The Yangshao culture burials discovered at Puyang in 1987 suggest that the beginnings of Chinese astronomy go back to the late fourth millennium. The instructive similarities between the Chinese and Indian luni-solar calendrical astronomy and cosmology therefore with great likelihood result from convergent parallel development and not from diffusion."

Above: Kot Diji phase steatite button seal from Harappa

Abstract

Hypotheses of a Mesopotamian origin for the Vedic and Chinese star calendars are unfounded. The Yangshao culture burials discovered at Puyang in 1987 suggest that the beginnings of Chinese astronomy go back to the late fourth millennium. The instructive similarities between the Chinese and Indian luni-solar calendrical astronomy and cosmology therefore with great likelihood result from convergent parallel development and not from diffusion.

Introduction

In what follows, I propose that the first Indian stellar calendar, perhaps restricted to the quadrant stars, was created by Early Harappans around 3000 BCE, and that the heliacal rise of Aldebaran at vernal equinox marked the new year. The grid-pattern town of Rahman Dheri was oriented to the cardinal directions, defined by observing the place of the sunrise at the horizon throughout the year, and by geometrical means, as evidenced by the motif of intersecting circles. Early Harappan seals and painted pottery suggest that the sun and the centre of the four directions symbolized royal power.

Note: The early steatite seal above plays an illustrative role in the author's thesis.

Abstract

Hypotheses of a Mesopotamian origin for the Vedic and Chinese star calendars are unfounded. The Yangshao culture burials discovered at Puyang in 1987 suggest that the beginnings of Chinese astronomy go back to the late fourth millennium. The instructive similarities between the Chinese and Indian luni-solar calendrical astronomy and cosmology therefore with great likelihood result from convergent parallel development and not from diffusion.

Introduction

In what follows, I propose that the first Indian stellar calendar, perhaps restricted to the quadrant stars, was created by Early Harappans around 3000 BCE, and that the heliacal rise of Aldebaran at vernal equinox marked the new year. The grid-pattern town of Rahman Dheri was oriented to the cardinal directions, defined by observing the place of the sunrise at the horizon throughout the year, and by geometrical means, as evidenced by the motif of intersecting circles. Early Harappan seals and painted pottery suggest that the sun and the centre of the four directions symbolized royal power.

Note: The early steatite seal above plays an illustrative role in the author's thesis.

Deity Seal

June 2nd, 2015

Deity seal from Mohenjo-daro. E.J.H. Mackay writes of what he calls a "deity, seated in what may be a yogi attitude" where, in this case, "the stool is omitted, however, and the figure is apparently seated upon the ground. The headdress consists of two horn-like objects between which there appears to be a spike of flowers. A pigtail hangs down one side of the head which has one face only, in profile, facing to the right. Unfortunately this seal is badly broken, but enough remains to show that the figure was surrounded by pictographs arranged in a somewhat haphazard fashion." (Further Excavations at Mohenjo-daro, 1938, p. 334).

https://www.harappa.com/blog/deity-seal kamaDha 'penance' rebus: kammaTa 'mint' dhatu 'scarf' rebus: dhAtu 'mineral, ore' karA 'bracelets, wristlets' rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' meDh 'polarstar' rebus: meD 'iron, copper' ayo, aya 'fish' rebu: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' khambhaṛā''fish fin' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage'

Indus Valley civilization 2500-1750 BCE: Ashmolean

Museum, Oxford U.

Widespread finds of stone artefacts suggest that humans have occupied the Indian subcontinent for at least a million years, first as hunter-gatherers and later as farmers. India’s first great urban civilization, contemporary with those of Mesopotamia and Egypt, flourished for several centuries around the Indus Valley region. This ancient civilization was first systematically explored by archaeologists in the 1920s. Its best known excavated sites are Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, extensive and well-planned cities built of brick. Many aspects of the Indus culture remain mysterious. Its written documents, often in the form of small stone seals, are few and brief. The Indus script still remains undeciphered today.

EA 2009.6 Square seal

Triangular prism seal EAMd 13 kana, kanac = corner (Santali); Rebus: kañcu ..'bronze' kamaDha 'bow and arrow' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage' bhaTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron, copper' karNika 'legs spread' rebus: karNI 'Supercargo' kamaDha 'penance' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage/' ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' kharA 'crocodile' rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' khuṭo ʻleg, footʼ, °ṭī ʻgoat's legʼ; Nepalese. khuṭo ʻleg, footʼ(CDIAL 3894).Rebus: khoTa 'ingot' (See the bovine hoofed legs of platform of the seated person).

Indian archaeological finds of later periods

The Chanhu-daro Seal: Gaur Ravaging a Female

March 14th, 2016

Gregory Possehl, whose drawing is shown of seal, writes "Mackay found an extraordinary seal in his excavations at Chanhu-daro. It shows a short-horned bull, Bos gaurus, above a prostrate human figure. He thought that the scene depicted an attack by the bull, and the human on the ground was attempting a defense against the trampling animal. In an essay on the seal, F.R. Allchin explains that the gaur is standing on its hind legs, slightly elevated above a human figure; its front legs are shown in excited motion. The bull's erect penis is shown in correct anatomical position. The figure below the gaur is less clearly shown and consequently more difficult to interpret. Allchin and Mackay see a headdress to the far right bottom of the seal impression.

Seen from Allchin's perspective, the scene is very dynamic and excited; the bull is about to take a female goddess in an act that might be seen as sexual violence, and yet the clear appearrance of her open, exposed genitals tells that she is a willing partner in the deed."

Later, Possehl quotes Mackay's reading of the seal: "We are led to wonder whether the omnipresent 'bull,' whether unicorn, bison or zebu, may not be the symbolic representation of the Heaven Father, and just as the deity with the plant sprout emerging from head or genitals may not be Mother Earth."

Seen from Allchin's perspective, the scene is very dynamic and excited; the bull is about to take a female goddess in an act that might be seen as sexual violence, and yet the clear appearrance of her open, exposed genitals tells that she is a willing partner in the deed."

Later, Possehl quotes Mackay's reading of the seal: "We are led to wonder whether the omnipresent 'bull,' whether unicorn, bison or zebu, may not be the symbolic representation of the Heaven Father, and just as the deity with the plant sprout emerging from head or genitals may not be Mother Earth."

https://www.harappa.com/blog/chanhu-daro-seal-gaur-ravaging-female

saṅghā, saṅgā copulation (of animals) (Or.); rebus: sangaDa ‘turner’s

lathe’.barad, balad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'

d.han:ga = tall, long shanked rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'

Seals and Sodalities

April 10th, 2016

"Thus the main motifs of the seal tablets emphasize two cultural phenomena. The first is that there was a rich mythopetic basis for the use of these motifs. The second is that the main motifs emphasize pan-settlement relationships, i.e. something held in common by the society at large, namely, the sodality to which the individual belonged. In contrast, we can assume that the Harappan writing identifies the indivudual who bears the seal tablet since the sign order is rarely duplicated. Here then is a clue to the meaning of the writing as it appears on seal tablets. With high probability it describes the individual who bears the tablet by name, title, occupation, social status, family, etc., in the conventional manner of time. In toto the large seal tablet motifs represent the sodality to which the bearer of the seal tablet belongs. The writing identifies the individual within the sodality." (William Fairservis, The Harappan Civilization and its Writing, E.J. Brill, 1992, p. 6).

Although William Fairservis later reading of Indus signs within this framework is not widely accepted, this is still an acceptable train of thought. Animals could well represent distinct ethnic, tribal, or what Fairservis calls "sodalities," a word which usually refers to task-oriented Christian religious groups and fraternities. An unusual word, but it may not be far off to see Indus groups as probably having a spiritual bond. Massimo Vidale suggests that the animal on the seal may represent a particular tribe with a specialty, like merchants. It is notable that most seals represent real animals, like the bull or water buffalo or elephant or tiger, but there is a healthy mixture of imaginary creature seals, and it is not impossible to think of the unicorn seal as taking the parts of other seals and representing them together in some sort of unified structure or ideology. This unifying force spread most widely across cities and towns around 2500-2300 BCE.

Although William Fairservis later reading of Indus signs within this framework is not widely accepted, this is still an acceptable train of thought. Animals could well represent distinct ethnic, tribal, or what Fairservis calls "sodalities," a word which usually refers to task-oriented Christian religious groups and fraternities. An unusual word, but it may not be far off to see Indus groups as probably having a spiritual bond. Massimo Vidale suggests that the animal on the seal may represent a particular tribe with a specialty, like merchants. It is notable that most seals represent real animals, like the bull or water buffalo or elephant or tiger, but there is a healthy mixture of imaginary creature seals, and it is not impossible to think of the unicorn seal as taking the parts of other seals and representing them together in some sort of unified structure or ideology. This unifying force spread most widely across cities and towns around 2500-2300 BCE.

Bos Indicus

April 14th, 2016

"The humped bull (Bos indicus) has a long and special association with India. Its association with Siva, its all pervading holiness and its basic usefulness in agriculture and commerce for than four millennia are too well known to need description. Its peculiar importance extends back to prehistoric times. We see it represented on the seals and in the terracotta figurines of the Indus civilization where it is clearly differentiated from other types of bovines. It is also by far the commonest subject of rick paintings and terracottas associated with prehistoric and historic sites outside the Harappan culture area, and from the mid-third millennium forward. Throughout western India wherever animal remains from archaeological sites have been studied bovine bones predominate; and there is general agreement that these nones represent in the main Bos indicus. Cattle bones have also been discovered in Mesolithic rock shelters in cntral India and at stratified open sites in Rajasthan, and these may well be even earlier, but detailed studies have not yet been published. The genesis of Bos indicus in relation to other breeds of cattle, and particularly Bos primigenius, has been the subject of various viewes. Zeuner held that it was derived from an indigenous wild form, perhaps Bos nomadicus, cattle of the Indian Pleistocene [from about 2.5 million to 11 thousand years ago], and this is still a convincing hypothesis, although firm data are still wanting. Although competing with other bovines represented by the Harappans, Bos indicus seems from the beginning to have reigned supreme outside the Harappan empire, and to have become virtually the universal domestic breed of cattle in the Indian sub-continent in historic and modern times. Identified remains of water buffalo (Bos bubalis) are comparatively rare in archeological sites, and although widely used today the buffalo enjoys neither the prestige nor the affection bestowed upon the cow."

R. and B. Allchin, Some New Thoughts on India Cattle, South Asian Archaeology 1973, p. 71.

Seal with Two-Horned Bull and Inscription, c. 2000 BC, Courtesy Cleveland Museum of Arthttp://www.clevelandart.org/art/1973.160

https://www.harappa.com/blog/bos-indicusDecember 19, 2013 12:00 am JST

Japanese researchers help unravel mystery of the Indus civilization

KOJI KAMIYA, Nikkei staff writer

TOKYO -- A five-year study by a Japanese research team could change the accepted view of the ancient Indus Valley civilization.

The study found that thousands of years ago, several cities in the Indus Valley, in what is today Pakistan and India, created a trade network that became a multicultural, multilingual civilization, and not a society founded on centralized authoritarian rule as previously believed. Many characteristics of this ancient civilization can be seen today in societies of southern Asia, and these links between the ancient and the modern are arousing researchers' interest.

The fresh image of the Indus civilization is being painted by a team of researchers led by Professor Emeritus Toshiki Osada of the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, which is based in Kyoto. The results of five years of research, known as the Indus Project, were published in October by the Kyoto University Press as "Indus: Exploring the Fundamental World of South Asia" and "The Riddle of the Indus Civilization," both compiled by Osada.

The Japanese-led research team consisted of around 40 researchers from various countries. Two Indus civilization sites in India were excavated for the first time by a Japanese expedition. The team focused on changes to the ancient environment. Osada's conclusion from the research has been that "different regional communities created a loose network through trade."

Desert came first?

Two of the more well-known ruins of the Indus civilization are Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, both in Pakistan. Currently, most researchers focus on the ruins of five major urban centers: the two famous sites; Pakistan's Ganeriwala, which is in a desert; India's Dholavira, which is on an island in a marsh; and Rakhigarhi, also in India.

The common view is that the desert sites used to have rivers other than the Indus flowing nearby. Researchers, led by Hideaki Maemoku, a physical geography expert and professor at Japan's Hosei University, examined the area around the desert ruins with a dating method based on mineral crystals. They learned that sand dunes in the area were shaped by a great river long before the Indus civilization existed. The conclusion is that the cities were built on these dunes only after the river was long gone.

At Dholavira, artifacts have been found that suggest thriving maritime trade. The most likely candidates for this trade are the ancient societies in Mesopotamia, which could have been reached via the Arabian Sea. The Indus Project used computers to plot changes to the coastline over the centuries to figure out where ancient shorelines would have been. Geological features were also studied and changes in terrain were estimated. All of this found that sea levels were around 2 meters higher and the coastline was much deeper inland. This suggests that many of the ruins in the area were along the ancient shoreline and that this part of the Indus civilization was dependent on the ocean.

Ancient passports

The research has also tried to find out when and why the Indus civilization declined. When changes in the distribution of ruins are traced using what is called a geographic information system, ruins start to concentrate in northern India at the decline of the civilization. Tezukayama University professor Takao Uno, an expert in archaeological geographical information systems, points out: "Perhaps they abandoned cities and migrated in order to avoid changes in the environment. As a result, the role of various elements of the cities that supported their network may have waned, leading to the decline of cities."

Other researchers are taking note of the Indus Project. "These results were produced using the latest technology in the natural sciences," said Yoshihiro Nishiaki, a professor at the University of Tokyo's University Museum and an expert in West Asian archaeology. "It is very interesting that the Indus civilization could have links to present-day South Asian societies. This will shape how we see this civilization."

European and U.S. researchers are also eager to learn more about the Indus civilization. Indus script has yet to be deciphered, which means there is much more to learn.

https://www.harappa.com/blog/ancient-indus-passportsFor a counter to the 'passport' approach, see:

Rebus readings of Meluhha hieroglyphs:

koḍa ‘one’(Santali) Rebus: koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’. kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. Hence, smith guild.

kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa 'bronze' (Te.) [See Meluhha glosses given at the URL cited]

mēd ‘body’ (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) kāḍ 2 काड् a man's length, the stature of a man (as a measure of length); rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’; Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ , (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) id. Hieroglyph: spread legs: karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'Supercargo'. Thus, the Kanmer hieroglyphs signify a Supercargo supervising the bronze cargo.

Indus Cylinder Seals May 4th, 2016

"The cylinder seals of Mesopotamia constitute her most original art," wrote the scholar Henri Frankfort, and much the same has been said about the very different square stamp seals used by the ancient Indus civilization. Cylinder seals are "small, barrel-shaped stone object[s] with a hole down the center, rolled on clay when soft to indicate ownership or to authenticate a document . . . used chiefly in Mesopotamia from the late 4th to the 1st millennium BCE." Many of the handful of cylinder seals found at ancient Indus sites or Mesopotamian ones with Indus themes are collected below.

1. Impression of a Harappan cylinder seal from Kalibangan (K-65). "Two warriors, distinguished by the hair worn in a divided bun at the back of the head, are spearing each other, while they are both being held by the hand by a goddess wearing a head-dress with a long pendant (comparable to the ones decorated with cowry shells and turquoise that are worn by the women of Ladakh and Chitral), bangles on the arms, and a skirt. Next to the combat scene (where space appears to have prevented the depiction of those details), her body merges with that of the tiger (later the Hindu goddess of war) and her head-dress is elaborated with animal horns and a tree branch," writes Asko Parpola in Deciphering the Indus Script, p. 253.

2. "The most reliable evidence of the date of the upper levels of Mohenjo-daro still continues to be Dr. Frankfort's seal. This seal [2] is cylindrical in form and of a totally different shape from the majority of the seals found in the Indus valley; but as three cylindrical specimens have been found at Mohenjo-daro, all of them, it should be noted, in the upper levels of that city, it is probably that they also were sometimes used by the inhabitants . The Tell Asmar seal [3] is, however, certainly of Indian workmanship. Not only are the animals upon it Indian, the elephant, rhinoceros, and gharial, or fish-eating crocodile, none of which ever appears on Sumerian or Akkadian seals, but the style of the carving is undoubtedly Indian." Ernest J. Mackay,The Indus Civilization, 1935, p. 193.