Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/z3doftt

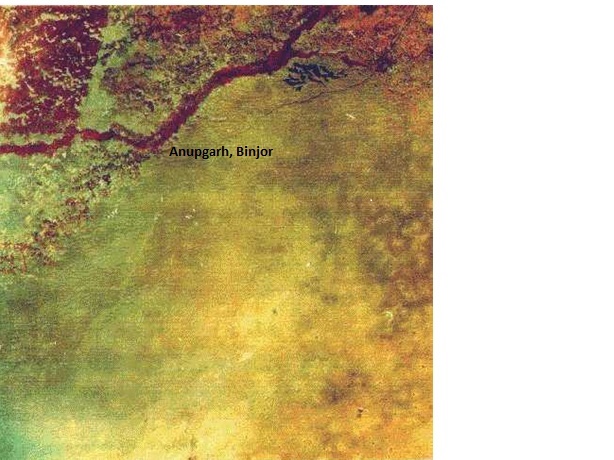

A suggestion for re-exploration of the River Sarasvati Basin in Gujarat-Rajasthan south of Anupgarh (Binjor).

The River Sarasvati split into two channels close to Binjor, one channel flowes south towards Jaisalmer.

The key is to identify mineral resources available in the localities south of Ganweriwala. The cluster in Ganweriwala excavated by Rafique Mughal can be explained by the proximity to Khetri mines of the Marusthali. I have not seen any geological studies of the nature of the terrain for the flows of River Sarasvati south of Ganweriwala, south of Jaisalmer. Of course, there is the Little Sarasvati reaching to Siddhapura, a site (close to Rani-ki-wav Patan) possibly visited by Sri Balarama and from there to Nagobheda (Anupgarh? Binjor?), Sivodbheda (Pokharan? Siv?) Further researches on the locally available material resources south of Ganweriwala is CRUCIAL. Did Little Sarasvati of Gujarat link up with ancient Drishadvati? What are the hydrological studies of the diversion of Drishadvati/Yamuna close to Rakhigarhi (Drishadvati which was earlier flowing westwards into Sarasvati through Banawali, Kalibangan etc.). A geological history of the Drishadvati is also IMPORTANT. This is the cradle of Vedic civiliation, Brahmavarta. I wish Min. of Culture orders a systematic study of the entire Sarasvati River system and basin with over 2000 sites (80% of the so-called Harappan or Indus Valley civilization). We have touched only the fringe of the investigation. Rakhigarhi is a good start. NOT enough.All sites include Bhatinda should be taken up for excavation and coordinated study to document the dynamics of life activities of our pitr-s, our Vedic Rishis and artisans, karmAra.

All these are speculations can be postulated as hypotheses by young researches who should get research facilities from a Sarasvati Museum to be set up in Kurukshetra. Another could also be in Kashi or Kolkata to study the Maritime Tin Route which linked up with Hanoi, Vietnam and Mekong delta, which has the largest tin belt of the globe.

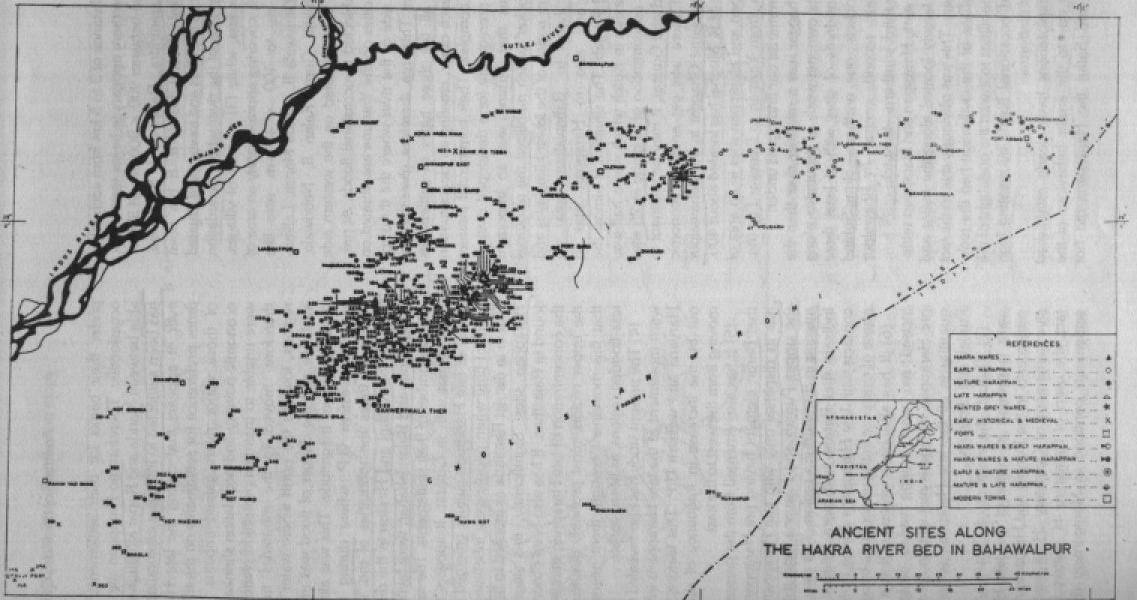

Cluster of sites in Bahawalpur Province, Cholistan (North of Rann of Kutch)![]()

Published: July 18, 2015 00:00 IST | Updated: July 18, 2015 05:48 IST Thiruvananthapuram, July 18, 2015

KU team digs up history at Rann of Kutch

Unearths 19 sites, somearound 2,000 years old

A team of researchers and students from the Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala, has discovered an ‘early historic site’ at Moti Cher in the Rann of Kutch, Gujarat.

Explorations (in April-May, 2015) by the team in the larger Kutch area unearthed 19 new archaeological sites of which two were new Harappan sites. The rest are datable to the Early Historic and Medieval periods.

According to team leader and assistant professor S.V. Rajesh, the excavations were done to “understand the distribution of Harappan culture in Kutch and inter-relationships between the Harappan and related contemporary cultures in the Kutch region.” Early Historic sites in the context of Kutch date back to around 2,000 years and beyond while Medieval sites date back to around the 9{+t}{+h}century AD, Dr. Rajesh said.

Moti Cher yielded evidence for large scale production of ceramics, iron working, and shell working. Major finds from the site include shell bangles, carved bones, stone beads, iron objects, grinding stones, red polished ware and gray ware ceramics.

“This is interesting as it borders the Great Rann of Kutch, now almost barren, and the evidence yielded from the site indicates the area was a thickly habitated flourishing township during historic to medieval period and probably played a vital role in the trade between Gujarat and the Sind region,” Dr. Rajesh said.

Another site of Nani Rayan which was resurveyed extensively also yielded a large number of artefacts attesting to its early historic to medieval antecedence. The finds from this spot are ceramics including shards of torpedo jars, red polished ware, turquoise glazed ware, other local ceramic, stone and glass beads, shell bangles and a Ganesa figurine.

The team also conducted excavations at the site of Navinal which was explored thoroughly in 2014. This year’s excavation yielded mud brick and stone structures and artefacts (stone beads, amulet, animal figurines, shell bangles, shell comb, copper objects and ceramics), establishing Harappan antecedents. Many indicators of large scale craft production (pottery production, stone tool production, copper working and shell working) were visible at the site.

Other sites

Apart from the exploration and excavation activities the students also visited Harappan sites including Dholavira, Lothal, Desalpur, Surkotada, Kanmer, Narapa, Shikarpur and Juni Kuran and monuments and forts of Champaner, a world heritage site. The team explored the medieval glaze production site at Lashkarshah in Khambhat in Anand district and also interacted with artisans at Khambhat and Gunthiali.

Two are new Harappan sites

Excavations yield many artefacts

Archaeology delegation unearths 19 sites, some of which dates back to 2,000 years.

Printable version | May 31, 2016 6:55:10 AM | http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Thiruvananthapuram/ku-team-digs-up-history-at-rann-of-kutch/article7437022.ece

Published: April 19, 2014 16:16 IST | Updated: April 19, 2014 16:16 IST April 19, 2014

Call of the white desert

![A child poses with her doll in the White Rann. A child poses with her doll in the White Rann.]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarA child poses with her doll in the White Rann.

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarA child poses with her doll in the White Rann.![On Mandvi Beach. On Mandvi Beach.]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarOn Mandvi Beach.

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarOn Mandvi Beach.![A young embroiderer at work. A young embroiderer at work.]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarA young embroiderer at work.

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarA young embroiderer at work.![Inside a bhunga in Banni. Inside a bhunga in Banni.]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarInside a bhunga in Banni.

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarInside a bhunga in Banni.![A Khatri family member demonstrates the art of Rogan painting. A Khatri family member demonstrates the art of Rogan painting.]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarA Khatri family member demonstrates the art of Rogan painting.

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarA Khatri family member demonstrates the art of Rogan painting.![Shaam-e-Sarhad, Hodka. Shaam-e-Sarhad, Hodka.]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarShaam-e-Sarhad, Hodka.

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarShaam-e-Sarhad, Hodka.![A villager serves as security guard in Hodka. A villager serves as security guard in Hodka.]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarA villager serves as security guard in Hodka.

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarA villager serves as security guard in Hodka.![Rosy Starlings in the Little Rann Rosy Starlings in the Little Rann]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarRosy Starlings in the Little Rann

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarRosy Starlings in the Little Rann![Wild asses in the Little Rann Sanctuary Wild asses in the Little Rann Sanctuary]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarWild asses in the Little Rann Sanctuary

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarWild asses in the Little Rann Sanctuary![Posing Bollywood-style in the White Rann Posing Bollywood-style in the White Rann]() Photo: Janhavi AcharekarPosing Bollywood-style in the White Rann

Photo: Janhavi AcharekarPosing Bollywood-style in the White Rann

The writer describes the lure of the Rann, a cross between a photoshopped work of art and a fun fair.

As we drove through the arid landscape of the Rann of Kutch, our driver narrated an incident from the night before. A young man from Tamil Nadu entered the drivers’ tent. He had arrived by train that morning and had hitchhiked his way from Bhuj Railway Station. Having spent all his money on the train ticket, he was seeking a place for the night. His wallet was empty; he wasn’t worried about his living arrangements, he said — a cot under the stars would do just fine — and he could do without food for a day or two. It was his burning desire to see the White Desert once in his lifetime, so here he was. Could anyone give him a lift to the Great Rann the next day?

“Someone offered him a ride to the check post,” said Bawaji, our driver. “And all the drivers contributed Rs. 50 each so the man could see the Salt Desert and eventually make his way back home.”

Such is the draw (and the spirit) of the Rann. On a good day, it looks like a madly photoshopped work of art — like a white background sans subject. On a bad day, it is reminiscent of a fun fair. The Rann surprises you with its remoteness and solitude in a shrinking world but remains within easy reach for those who wish to explore it. In peak season (November to March), you will find accommodation if you’re lucky. There are few places where you can stay near the desert. Of these, Hodka is a small oasis-refuge of sorts. Its Shaam-e-Sarhad resort is a community initiative and a successful experiment in endogenous tourism supported by the Ministry of Tourism and the United Nations. The bhungas or traditional mud huts of the region, and tents, lend to the authenticity of the place and are comfortable enough, looked after by its staff of local villagers trained in hospitality.

A region of artisans, Hodka and its neighbouring villages are a textile lover’s Mecca. The Meghwal community is known for its ‘pakko’ embroidery, a 500-year-old tradition among the families in the Banni region. Meanwhile, in nearby Nirona, a single village path houses an illustrious family of Rogan artists alongside bell metal craftsmen and lacquer work artists. Rogan art is created with a metal pin dipped in a mixture of castor oil residue and mineral dyes. Its fine motifs are drawn by dropping this mixture onto one side of a cloth that is then folded to form a perfect mirror image. The Khatris of Nirona are the only surviving Rogan artists today. Meanwhile, there’s appliqué work in Dordo, and further away in Bhujodi, camel wool shawls are woven on pit-looms. Everywhere, mirror-work embroidery abounds. Some of the arts here date back centuries if not to the time of the Harappan civilisation.

In Hodka, the nights are magical; stars are suspended like diamond teardrops in a vast midnight blue sky and the silence broken only by the call of a jackal in the dead of the night. Only 30-odd kilometres from Pakistan, it has the feel of a border village. In fact, Shaam-e-Sarhad means exactly that — an evening by the border.

The border stretches across other towns, including the deserted ruins of Lakhpat, where you can look into the vast grey sea from the BSF viewpoint and imagine Karachi on the other side. The port of Mandvi, meanwhile, surprises visitors with its clear blue waters and clean beaches. Wherever you go, cattle herders, camel owners, guides and drivers will point somewhere in the direction of the setting sun— across the ocean or over mountains like the Kala Dungar, saying, “That’s Pakistan.” Stories abound too, of relatives on the other side who may never be able to visit their country of origin — of doomed marriages and siblings who traversed the India Bridge during friendlier times but who now find it impossible to meet their families in India.

The Rann of Kutch has seen a surge in tourism since its successful advertising and yet its feathered winter visitors far outnumber the two-legged variety. It is a haven for birders (particularly flamingo-seekers), with its migratory painted storks, cranes and pelicans, Egyptian vultures, native wheatears and rosy starlings, among hundreds of other species. A few hours away from the Great Rann, past the nomadic dwellings of the dairy-selling Jat tribe, past the wires with their dancing green bee-eaters and black-shouldered kites, and past the capital, Bhuj, is the Little Rann Sanctuary that is visited, apart from its wealth of birdlife, for the Khur or the Wild Ass. And not too far from here lie the spectacular heritage sites of Modhera and Patan.

Printable version | May 31, 2016 6:57:44 AM | http://www.thehindu.com/features/magazine/call-of-the-white-desert/article5928726.ece

Published: January 8, 2016 15:56 IST | Updated: January 8, 2016 19:30 IST Chennai, January 8, 2016

Sun, salt and the Great White Rann

![]() AP

AP![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

What draws tourists from across the world to the Rann Utsav? AKILA KANNADASAN finds out

Eight hours of a backbreaking bus journey. A highway with few decent restrooms. And, weather that doesn’t hesitate to remind you that you’re in camel territory. The Rann of Kutch sounds like an oasis, as I trundle along a dusty road with nothing but roadside dabeli to appease a grumbling stomach. Is it worth it? The endless stretch of salt, life in a ‘tent city’ that mushrooms on the desert just for three months to host the Rann Utsav, craft villages that bring to mind terracotta walls with limestone drawings — I wring my hands and peek outside the window — this better be good.

We arrive at Dhordo, the tent city, on a freezing December night, too tired to take in the atmosphere. Winds blow from afar, sending us deep inside our warm-wear. The fully-furnished tents await us — we bury ourselves in for the night.

At the Rann, meaning ‘desert’ in Hindi, the setting sun takes with it every last speck of warmth. And so we feel grateful when it rises every day. No one dares take it for granted in Kutch, especially during winter. It’s best to rise with the sun when you’re here and retire when it sets.

There are two things that define the Rann of Kutch — the flat snow-white salt marsh and the Kutchi people, who are among the most artistic in the world. They spend their days sharing a landscape with sandstorms, and nights amid the eerie chill. The lack of colours in their environment, dominated by dull browns and dirty greens, has drawn them to the reds, blues, and yellows that embellish their clothes.

Hodka is an example of how these people have incorporated colour into their lives. The village is jewelled with bhungas, circular mud huts with conical thatch roofs, some of which serve as home-stays. Peek into one, and you may catch Sonia engrossed in mirror embroidery, a Kutch trademark. She sells exquisite bags, quilts and patches that are studded with mirrors. Dressed in an ornate kanjari (a backless top), a long cotton skirt and a dupatta that flows from head to toe, she represents the typical Kutchi woman — one who’s on her toes through the day. When she’s not cooking for the family, she’s working on a fabric that she hopes to sell to visiting tourists.

Here is a community that depends on handicrafts for a living. Where men double as cattle rearers and artisans; where people like Umra can turn a piece of leather into artistic footwear. Behind the handicrafts village is the private living quarters of the people — although they are hospitable, it’s best to let them be. We stop at yet another crafts village where string cots gleam with beadwork necklaces and jhumkas.

The Rann of Kutch is a handicraft haven where you can buy from the artisans themselves; the money goes directly into their pockets, so it’s best not to bargain. Craft stalls come alive on the outskirts of the tent city towards evening. With food and plenty of chai to sip on as you shop, these stalls showcase glittering mirror-worked clothes, handmade footwear and bead jewellery, most of which will not be available elsewhere in Gujarat. (The evening market at Law Garden in Ahmedabad boasts imitation versions, where plastic mirrors replace the real ones).

Our Rann of Kutch experience ends on a windy evening, when the sun threatens to set by an endless ocean of white — the White Rann. On first sight, it looks like snow. Step on it and you can feel it crunch under your feet. The realm of salt lays bare as a chill sets in. The moon looks like something out of a dream — it’s the night before the full moon. Camels jingle by, drawing cartfuls of people, and cameras flash as the skies darken.

The best way to experience the White Rann is to sit by yourself and take it all in. It’s an eerie feeling; with the moon bobbing overhead and a spotless whitescape extending before you…you can travel across the world for just a few minutes of this.

I don’t complain much on my eight-hour return journey by bus to Ahmedabad — there are certain things that you endure to witness something as magnificent as the Great Rann of Kutch.

(The writer was in Gujarat on invitation by the Tourism Corporation of Gujarat)

Printable version | May 31, 2016 6:59:09 AM | http://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/explore-the-beauty-of-the-rann-of-kutch/article8082019.ece

Published: June 12, 2013 13:25 IST | Updated: June 15, 2013 11:19 IST

Discovering Khirsara’s Harappan glory

- PHOTOGRAPHS BY D. KRISHNAN

- PHOTO EDITORTHE HINDU

Show Caption

Excavations in Khirsara village in western Kutch reveal a "major industrial hub" and trading centre of the mature Harappan phase. By T.S. SUBRAMANIAN in Khirsara. Photographs by D. KRISHNAN, Photo Editor, The Hindu.

AS I stood on the edge of the trench and looked in, my eyes widened with amazement. In one corner stood a tall, slender jar with four perforations, two on either side, just below the rim. There were three beautifully crafted pots, wedged in the soil and, a few feet away, a big, upturned lid. Also on the trench floor lay a massive conch shell that looked like a bird with outstretched wings, as if it had been shot in flight and had fallen to the ground.

Outside the trench that April morning, on the baulk, stood Jitendra Nath, who was the director of the excavation. “Will you measure the height and the width of the jar?” he asked Kalyani Vaghela, the young research assistant in archaeology from the Maharaja Sayajirao University, Vadodara, Gujarat. She unfurled the tape and rolled it down the height of the jar and announced that it measured 85 centimetres in height. It was 33 cm in diameter.

“This is an important find. We have got so much of pottery in a small area within the trench. When we extend our excavation more, we will get an idea of why we are getting so many pots and jars in a small area,” said Jitendra Nath. He is the Superintending Archaeologist, Archaeological Survey of India’s (ASI) excavation branch in Vadodara.

The excavation, a massive one, is under way at Khirsara, a Harappan site situated about 85 km from Bhuj town in Gujarat’s Kutch district. Thirty-nine trenches, each 10 metres by 10 metres in area, have been laid since December 6, 2012. They have yielded a cornucopia of globular pots, sturdy storage jars, painted ware, perforated parts of broken jars, incense burners, dish-on-stand, goblets, beakers, basins, bowls, ladles, and so on. “There is pottery everywhere. We have to dig carefully. We can use only small pickaxes,” said Jitendra Nath. The excavation team has also unearthed terracotta figurines of bulls, peacocks, ducks, and also an anthropomorphic figurine. A lot of toy-cart frames made of terracotta were found. The excavation, which is into its fourth year, reveals that Khirsara, which lies on the trade route to Sind (now in Pakistan), was once “a major industrial hub” in western Kutch. The 12-acre site, situated on the outer edge of Khirsara village, sits saucer-like, with mounds on all sides and a depression in the middle and is known locally as “Gadh Wali Wadi”. The Khari river flows nearby and in the distance are the hills of Kutch. A Harappan settlement, belonging to the mature Harappan phase, flourished here for 400 years from circa 2600 BCE to circa 2200 BCE.

“Mature” evidence

The Harappan civilisation can be divided into three phases, early, mature and late. If the early Harappan phase lasted from circa 2800 BCE to circa 2600 BCE, the mature phase was between circa 2600 BCE and circa 1900 BCE. The late phase, including its collapse, lasted from circa 1900 BCE to circa 1500 BCE. Juni Kuran in northern Kutch and Khirsara belong to the mature Harappan phase. And Dholavira, located on the island of Khadir in the Great Rann of Kutch, is an example of a Harappan site that typifies all three phases.

The Harappan civilisation can be divided into three phases, early, mature and late. If the early Harappan phase lasted from circa 2800 BCE to circa 2600 BCE, the mature phase was between circa 2600 BCE and circa 1900 BCE. The late phase, including its collapse, lasted from circa 1900 BCE to circa 1500 BCE. Juni Kuran in northern Kutch and Khirsara belong to the mature Harappan phase. And Dholavira, located on the island of Khadir in the Great Rann of Kutch, is an example of a Harappan site that typifies all three phases.

Jitendra Nath pointed to the important features that make Khirsara a mature Harappan site. “Pre-Harappan pottery and post-Harappan pottery are absent here. The settlements belonging to the early Harappan and late Harappan phases are also not found here,” he said. Besides, Khirsara has thrown up artefacts and structures that make it a mature Harappan settlement. There are massive structures, fortifications, seals with script and carvings of animals, bricks with the standardised ratio of 1:2:4, and a variety of pottery, including reserved slip ware, which is called so because a slip, that is, a coloured coating is applied over the pot after it is finished and dried. Specialists in the study of pottery say that such pottery was reserved for the elite, and hence the name. After the first slip (a coloured coating involving a solution of red ochre, white kaolin or purple or yellow colour) has dried, a second slip is applied over the first coating. When the second slip is wet, an instrument, say, a comb, is run over it to form different patterns. This removes the second coating that comes under the comb’s teeth, making a pattern on the pot, in the form of wavy or straight lines or even checks.

Northern polished black ware (NPBW) is reserved slip ware because it has a silvery or golden coating over it. The NPBW was mostly tableware and the elite used it. The quarry from which the stones were brought to the habitational-cum-industrial site has not been identified yet.

“Seals found in this site belong from the early stage to the late stage of the mature Harappan phase. There are rectangular seals depicting the unicorn and the bison and the Harappan characters. There are rectangular bar-type seals with the Harappan script alone and circular seals, all of which show that Khirsara is a mature Harappan site,” said Jitendra Nath. He argued that seals were the “main characteristic” by which Khirsara could be classified as a mature Harappan site. “We are getting seals from the lowermost level to the uppermost. Pottery, seals and structures are the major hallmarks by which this site could be said to belong to the mature Harappan phase,” he reasoned.

The team encountered five structural phases in the mature Harappan stage itself at Khirsara, said R.N. Kumaran, Assistant Archaeologist, ASI. Floods led to the termination of each phase and evidence of flood deposits was available in the citadel area. “We are getting sand and silt in a continuous band. ‘Kankar’ stones were also available,” said Kumaran.

The structural remains of a fortified settlement revealed a citadel with residential quarters, a warehouse, an industrial-cum-residential complex, habitation annexes and a potters’ kiln, all pointing to systematic town planning. The citadel complex was where the ruling elite lived. It had square and rectangular rooms, verandahs in front, a beautiful staircase leading upstairs and a rock-cut well. The warehouse, 28 metres long and 12 metres wide, has a series of 14 massive parallel walls, which are more than 10 metres long and about 1.5 metres wide. All the structures are built of dressed sandstone blocks, set in mud mortar.

Magnificent artefacts

The artefacts that have been discovered here reinforced the “industrial” nature of the settlement. Among them is a gold hoard, in a small pot, of disc-shaped gold beads, micro gold beads and their tubular counterparts. As Jitendra Nath and this reporter stood on a trench that had been filled up, he pointed to the levelled earth below and said, “It was in this trench that your friend S. Nandakumar [a site supervisor] found the gold hoard.” It was a trench allotted to Nandakumar, and one of the labourers digging the trench came up with a pot that had 26 gold beads inside. “Gold beads are not found in big quantities in the Harappan sites,” Jitendra Nath said. Some disc-shaped gold beads were found at Lothal, a Harappan site in Gujarat.

The artefacts that have been discovered here reinforced the “industrial” nature of the settlement. Among them is a gold hoard, in a small pot, of disc-shaped gold beads, micro gold beads and their tubular counterparts. As Jitendra Nath and this reporter stood on a trench that had been filled up, he pointed to the levelled earth below and said, “It was in this trench that your friend S. Nandakumar [a site supervisor] found the gold hoard.” It was a trench allotted to Nandakumar, and one of the labourers digging the trench came up with a pot that had 26 gold beads inside. “Gold beads are not found in big quantities in the Harappan sites,” Jitendra Nath said. Some disc-shaped gold beads were found at Lothal, a Harappan site in Gujarat.

There are a variety of beads made of shell and steatite and of semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli, agate, carnelian, chert, chalcedony and jasper. About 25,000 steatite beads were found in one trench alone. Shell bangles, shell inlays, copper bangles and rings were also found in plenty. Among copper implements were chisels, knives, needles, points, fish hooks, arrow-heads and weights. There were also bone tools, bone points and beads made out of bones.

“We have found good evidence of bead-making here,” said Jitendra Nath. “We found a lot of drill-bits used for drilling holes in the beads…. We also found stone weights of various denominations. While the smallest weighs five grams, the heaviest is about five kilograms.”

The ASI team found 11 seals, including circular seals. Some of them are carved with unicorn and bison images, and have the Harappan script engraved on them. While the unicorn seal is made of soapstone, the bison seal is made out of steatite. A rare discovery was that of two bar seals, both engraved with the Harappan script only and remarkably intact.

The trenches have yielded a vast amount of reserved slip ware, painted with exquisite designs; a variety of red ware; buff ware, or polished ware; chocolate-coloured slip ware; and grey ware.

Jitendra Nath said: “The kind of antiquities we are getting from this site indicates that Khirsara was a major industrial hub in western Kutch. It was located on a trade route from other parts of Gujarat to Sind in Pakistan, which is about 100 km away. Of course, the Harappans who lived here were basically traders, manufacturing industrial goods for export to distant lands and to other Harappan sites in the vicinity and farther away.”

Fortification

Khirsara is unique among Indus Valley settlements in having a general fortification wall around the settlement and also separate fortification walls around every complex inside the settlement. The citadel complex, the warehouse, the factory-cum-residential complex, and even the potters’ kiln have their own protective walls.

Khirsara is unique among Indus Valley settlements in having a general fortification wall around the settlement and also separate fortification walls around every complex inside the settlement. The citadel complex, the warehouse, the factory-cum-residential complex, and even the potters’ kiln have their own protective walls.

The massive, outer fortification wall still stands in many places, 4,600 years after it was built. It measures 310 metres by 210 metres and is built of partly dressed sandstone blocks set in mud mortar. The wall’s width is 3.4 metres but additional reinforcements in later phases have increased its width considerably. The bedrock below the wall was levelled with clay, sand, grit, lime and thoroughly rammed in to bear the load of the superstructure. Like fortification walls in other Harappan sites, this one also slopes upwards to give it strength and life.

Said Jitendra Nath: “We found three salients on the northern fortification wall of the warehouse. The outer fortification too has salients at regular intervals for giving strength to the wall and for mounting watch.” A protection wall, with a width of 2.34 metres, running parallel to the outer fortification wall, was built on the northern and eastern sides to protect the site when the overflowing Khari river caused flooding.

As the booklet Indus Civilisation brought out in 2010 by the Indus Research Centre, Roja Muthiah Research Library, Chennai, says, the Harappan (or Indus Valley) civilisation “has fascinated not just historians and archaeologists and anthropologists but also experts from such diverse fields such as urban planning, architecture, linguistics, computer science, mathematics, statistics, geology, astrophysics etc.” What fascinated them was “the greatness of this ancient civilisation, its vast extent, its trade links to other regions and its great achievements in the fields of architecture, commerce, fine arts, manufacturing, etc. These are being better understood with every new archaeological find.”

Indus enigma

However, as the booklet says, “The Indus civilisation remains an enigma in some ways. The cause of the sudden fall of the civilisation—renowned for its urban planning, high-quality construction, water management and carefully designed drainage systems—is still not fully understood.” Besides, the Indus script continues to remain undeciphered despite attempts by scholars and researchers.

However, as the booklet says, “The Indus civilisation remains an enigma in some ways. The cause of the sudden fall of the civilisation—renowned for its urban planning, high-quality construction, water management and carefully designed drainage systems—is still not fully understood.” Besides, the Indus script continues to remain undeciphered despite attempts by scholars and researchers.

At its peak, the Harappan civilisation covered an area of 1.5 million square kilometres, across India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran. It extended from Sutkagendor in the Makran coast of Balochistan to Alamgirpur in the east in Uttar Pradesh and from Mandu in Jammu to Daimabad in Ahmednagar district in Maharashtra. Since the 1920s, several hundred Harappan sites have been discovered. After Partition in 1947, when Mohenjardo and Harappa fell in Pakistan, the ASI has discovered many sites in Gujarat, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jammu and Kashmir, and Maharashtra. These sites include Dholavira, Lothal, Juni Kuran, Desalpur, Narappa, Kanmer, Surkotada and Shikarpur in Gujarat; Rakhigarhi, Bhirrana, Banawali and Farmana in Haryana; Alamgirpur, Sanauli and Hulas in Uttar Pradesh; and Kalibangan in Rajasthan.

Discovery of Khirsara

How did the ASI’s excavation branch at Vadodara discover Khirsara? Since most Harappan sites were situated in northern or eastern Kutch, not much was known about the Indus civilisation in western Kutch. Desalpur was the only site excavated there, a minor excavation in the early 1960s. “So we were searching for a Harappan site in western Kutch,” said Jitendra Nath. The Gujarat State Archaeology Department had explored Khirsara in the 1970s, but only a brief report was available on it.

How did the ASI’s excavation branch at Vadodara discover Khirsara? Since most Harappan sites were situated in northern or eastern Kutch, not much was known about the Indus civilisation in western Kutch. Desalpur was the only site excavated there, a minor excavation in the early 1960s. “So we were searching for a Harappan site in western Kutch,” said Jitendra Nath. The Gujarat State Archaeology Department had explored Khirsara in the 1970s, but only a brief report was available on it.

Jitendra Nath’s keen eye, backed by his years of excavation at Taradih in Bodh Gaya, Athirampakkam near Chennai, Ummichipoyil in Kerala, and in other places, came into play. “When we came here, we saw so much of Harappan pottery, along with artefacts such as shell bangles and stone-beads scattered over the surface,” he said. “Then we looked at the site and found it almost intact. We did not have such a big site in western Kutch before. Desalpur was the only other Harappan site in western Kutch.” But Desalpur was excavated for only one season and not much was known about it.

So Jitendra Nath and his team did a survey of Khirsara in 2009 and began excavation in December that year. The ASI team exposed the inner and outer sides of the fortification and found residential structures along the inner side of the fortification.

In the second year (season) of excavation, the team unearthed the citadel and went on to locate the factory area where it found evidence of a lot of industrial activity, including shell-working. There was tell-tale evidence of bead-making. A variety of beads made of copper, shell and terracotta, and semi-precious stones were found in abundance. Copper objects, including needles, knives, fish hooks, arrowheads and weights were found. What is puzzling is that no copper figurines of animals, as found in other sites, were found here.

When the ASI team dug up a mound, it encountered evidence of a five-metre-deep structure, going back to 2600 BCE. This earliest structure was made of stones with mud bricks used in between.

In the third year, the team excavated the residential complex in the citadel. The citadel was strategically located adjacent to the warehouse and the factory site in such a manner that the elite class might exercise full control over the manufacturing and trading activities. A five-metre-broad pathway led from the citadel to the industrial complex. The citadel complex was 90 metres by 90 metres and about a hundred people could have lived there. There were interconnected rooms, door sills, hearths, and so on. The houses had bathrooms with an outlet for water to flow. Streets inside the citadel were rammed with clay and household waste such as potsherds, bones, shell debitage and grits. A pot burial, containing charred bones and ash kept inside a circular hearth, was found inside a room. The ASI is yet to excavate a large area of the residential complex, but it may do so in the next season.

Bipin Negi, Assistant Archaeologist, ASI, pointed to the perfect manner in which the fortification wall around the citadel was built and how it had withstood the ravages of time. It is a tall, sloping wall, several metres in height. “This citadel wall is much broader than the general fortification wall. It is set in mud mortar, which is sticky clay. The wall has been standing for 4,600 years,” said Negi.

As we went around the trenches that had exposed the industrial-cum-residential complex, Kumaran explained how it had been identified as a factory site. “We have found furnaces and a tandoor. There is evidence of copper-working and ash. We have found huge quantities of steatite beads and some seals made of steatite. From all this evidence, we have identified it as a fortified factory site.” He led us to the entrance of the fortification wall of the industrial-cum-residential complex. The entrance was in the south. Akin to other Harappan sites, there were large limestone slabs at the entrance; the slabs obviously served as doormats. There were a couple of small guard rooms adjacent to the entrance. Residences inside the industrial complex, too, had stone slabs at the entrance. There were bathrooms, with sloping slabs used on the floor for water to flow into covered outlets. The outlets led into the drains in the street.

To the sheer delight of the ASI team, the warehouse came into view when they excavated the north-east corner of the site last year. Excavation of the warehouse, which has continued this year, has revealed it to be a massive structure with 14 parallel walls. Jitendra Nath said, “It must have been a multipurpose warehouse for storing goods meant for export and grains. A warehouse is a rare type of structure found in a few Harappan sites. It indicates a state of surplus economy and is a sign of prosperity. You build such structures for storing goods for export or goods that have been imported.” The parallel walls supported a superstructure made of wood and daub and goods were stored in the superstructure. The pathways between the parallel walls were air ducts to keep the goods fresh. The entrance had a series of guard rooms adjacent to it. The ASI found grains in the warehouse and samples of these grains have been sent to Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany, Lucknow, for investigation and identification.

Potters’ kiln

Situated on the outer side of the general fortification wall, the potters’ kiln is a bit of an engineering marvel. Negi pointed out that its fire chamber had been cut out of both bedrock and earth, and a dome sat on the fire chamber. The freshly made pots were arranged inside the dome and a passage led to the fire chamber. It was through the passage that the burning logs were pushed inside the fire chamber. The circular wall of the fire chamber had holes for air circulation and oxygenation. The burning logs generated heat of about 500 Celsius and the pots were baked.

Situated on the outer side of the general fortification wall, the potters’ kiln is a bit of an engineering marvel. Negi pointed out that its fire chamber had been cut out of both bedrock and earth, and a dome sat on the fire chamber. The freshly made pots were arranged inside the dome and a passage led to the fire chamber. It was through the passage that the burning logs were pushed inside the fire chamber. The circular wall of the fire chamber had holes for air circulation and oxygenation. The burning logs generated heat of about 500 Celsius and the pots were baked.

The ASI has not located the reservoirs which would have supplied water to the Harappan settlement at Khirsara. Jitendra Nath said, “Maybe, when we excavate more, we will find water bodies. The western half of the site has not been excavated yet. We have been concentrating mostly on the eastern half. We may dig the western half next year.” Kumaran was hopeful about the “possibility” of the existence of a reservoir because “we have found drains at a depth of 1.5 metres and paved stone flooring. It was not for carrying sullage.” There was also a rock-cut well in the residential quarters within the citadel. There were chances of encountering a reservoir if the excavation continued for two or three years. Jitendra Nath was confident that “a complete picture of the site will emerge only when we excavate more and more”.

Printable version | May 31, 2016 7:00:58 AM | http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/heritage/discovering-khirsaras-harappan-glory/article4794614.ece

Published: August 6, 2013 08:57 IST | Updated: August 6, 2013 09:01 IST August 6, 2013

Excavations reveal Khirsara a major industrial hub of Harappan era

![A cluster of pottery, including a tall slender jar, and a big conch shell found in one of the trenches. Photo: D. Krishnan A cluster of pottery, including a tall slender jar, and a big conch shell found in one of the trenches. Photo: D. Krishnan]() The HinduA cluster of pottery, including a tall slender jar, and a big conch shell found in one of the trenches. Photo: D. Krishnan

The HinduA cluster of pottery, including a tall slender jar, and a big conch shell found in one of the trenches. Photo: D. Krishnan![The bar seal with the Harappan script excavated at Khirsara. The bar seal with the Harappan script excavated at Khirsara.]() ASIThe bar seal with the Harappan script excavated at Khirsara.

ASIThe bar seal with the Harappan script excavated at Khirsara.![The disc-shaped gold beads found at Khirsara. The disc-shaped gold beads found at Khirsara.]() The disc-shaped gold beads found at Khirsara.

The disc-shaped gold beads found at Khirsara.

January 2, 2011 was a golden day in the second season of excavation at Khirsara village, 85 km from Bhuj town, Gujarat. Nearly 30 trenches had been dug that season, each 10 metres by 10 metres. One of them yielded two miniature pots, which a labourer rushed to S. Nandakumar, a site supervisor in his 20s. He took them to Jitendra Nath, Superintending Archaeologist, Excavation Branch, Vadodara, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). “They are gold beads,” announced Mr. Jitendra Nath after examining them. One of the pots contained 26 disc-shaped beads, micro beads and a ring, all made in gold, and steatite beads.

“Gold beads are not found in big quantities in the Harappan sites. Some disc-shaped gold beads had been found at Lothal, another famous Harappan site in Gujarat,” said Mr. Jitendra Nath on April 19, 2013 as he showed us the closed trench where the gold beads had been found.

“Exciting results” from four seasons of excavation with 120 trenches dug at Khirsara from December 2009 have established Khirsara as “a major industrial hub” that belonged to the mature Harappan period. It overlooks the Khari river and flourished for 400 years from circa 2600 to 2200 BCE.

Carbon dating at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleobotany, Lucknow, for the botanical remains collected from Khirsara’s trenches falls in the range of 2565 to 2235 BCE.

Khirsara has everything to be called a mature Harappan site: systematic town planning, a citadel complex where the ruling elite lived, a factory complex, habitation annexes, a warehouse, drainage system, and massive fortification walls. All the structures were built of sandstone blocks set in mud mortar. Excavations have yielded 11 bar, circular and square seals, standardised bricks in the ratio of 1:2:4 and a staggering variety of pottery including reserve slip ware. While the bar seals have only the Harappan script, others have carvings of unicorn and hump-less bulls with the Harappan signs.

Mr. Jitendra Nath asserted: “The seals, especially the circular seals, are the main characteristic by which Khirsara can be categorised as a mature Harappan site. Pottery and structures such as the citadel, the factory and the warehouse are the hallmarks by which this site could be said to belong to mature Harappan phase.”

More than 4,200 years ago, Khirsara was an important trading outpost in western Kutch in Gujarat on the way to Sind in present-day Pakistan. Its “factory” manufactured enormous quantities of beads from cornelian, agate, jasper, lapis lazuli, steatite and chalcedony; bangles and inlays from conch shells; copper artefacts such as bangles, rings, beads, knives, needles, fish-hooks, arrowheads and weights; and terracotta rattles, toy-carts and gamesmen. One trench alone threw up 25,000 exquisite beads made of steatite.

Trench after trench laid in Khirsara’s factory have yielded a bonanza of Harappan ceramics — painted pottery, the reserve slip ware used by the elite in society, sturdy storage jars, globular pots, perforated jars, basins, dishes, bowls, beakers, dish-on-stand and incense burners. The painted pottery with occasional animal motifs, have geometric designs of broad bands, crosses, spirals, loops, arches and zigzags. The profusion of miniature pots that the site has revealed is puzzling.

R.N. Kumaran, Assistant Archaeologist, ASI, said: “We have found furnaces and a tandoor. There is evidence of copper-working and ash. We have found huge quantities of steatite beads and some seals made of steatite. From all this, we have identified it as a factory site.”

An extraordinary feature about Khirsara’s Harappan settlement is that it not only had an outer fortification wall around it but every complex inside had its own fortification wall, be it the citadel, the warehouse, and the factory with its habitation annexe. The fortification walls for the warehouse and the factory had guard rooms and salients for mounting watch.

Even the potters’ kiln, which lay outside the outer fortification walls, had its own fortification wall. The outer fortification wall, 310 metres by 230 metres and more than 4,400 years old, still stands in several places.

“This is the first time in the Harappan context that we have found separation fortification walls for each complex on the site, and their purpose is to ensure the safety of its residents and the goods manufactured,” said Mr. Jitendra Nath, now Superintending Archaeologist, Mumbai Circle, ASI.

A massive warehouse, measuring 28 metres by 12 metres, excavated had 14 parallel walls, with an average length of 10.8 metres and 1.55 metres breadth. Its superstructure was made of wood and daub. The space between the parallel walls enabled circulation of fresh air to protect the stored goods. Mr. Jitendra Nath said: “It must have been multipurpose warehouse for storing goods for export or those that have been imported. Its proximity with river Khari is to support the maritime trading activities of the Khirsarans. A warehouse is a rare type of structure found in a few Harappan sites. It indicates a state of surplus economy.”

The houses in the citadel, where the elite lived, had verandas, interconnected rooms, floors paved with multicoloured bricks and a rock-cut well. A five-metre paved lane separated the citadel from the factory. The citadel was deliberately built adjacent to the warehouse so that the rulers could keep a watch on the manufacturing and trading activities, said Mr. Kumaran.

Printable version | May 31, 2016 7:20:52 AM | http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/excavations-reveal-khirsara-a-major-industrial-hub-of-harappan-era/article4994878.ece

Published: June 12, 2013 13:25 IST | Updated: June 15, 2013 11:19 IST

Discovering Khirsara’s Harappan glory

- PHOTOGRAPHS BY D. KRISHNAN

- PHOTO EDITORTHE HINDU

Show Caption

Excavations in Khirsara village in western Kutch reveal a "major industrial hub" and trading centre of the mature Harappan phase. By T.S. SUBRAMANIAN in Khirsara. Photographs by D. KRISHNAN, Photo Editor, The Hindu.

AS I stood on the edge of the trench and looked in, my eyes widened with amazement. In one corner stood a tall, slender jar with four perforations, two on either side, just below the rim. There were three beautifully crafted pots, wedged in the soil and, a few feet away, a big, upturned lid. Also on the trench floor lay a massive conch shell that looked like a bird with outstretched wings, as if it had been shot in flight and had fallen to the ground.

Outside the trench that April morning, on the baulk, stood Jitendra Nath, who was the director of the excavation. “Will you measure the height and the width of the jar?” he asked Kalyani Vaghela, the young research assistant in archaeology from the Maharaja Sayajirao University, Vadodara, Gujarat. She unfurled the tape and rolled it down the height of the jar and announced that it measured 85 centimetres in height. It was 33 cm in diameter.

“This is an important find. We have got so much of pottery in a small area within the trench. When we extend our excavation more, we will get an idea of why we are getting so many pots and jars in a small area,” said Jitendra Nath. He is the Superintending Archaeologist, Archaeological Survey of India’s (ASI) excavation branch in Vadodara.

The excavation, a massive one, is under way at Khirsara, a Harappan site situated about 85 km from Bhuj town in Gujarat’s Kutch district. Thirty-nine trenches, each 10 metres by 10 metres in area, have been laid since December 6, 2012. They have yielded a cornucopia of globular pots, sturdy storage jars, painted ware, perforated parts of broken jars, incense burners, dish-on-stand, goblets, beakers, basins, bowls, ladles, and so on. “There is pottery everywhere. We have to dig carefully. We can use only small pickaxes,” said Jitendra Nath. The excavation team has also unearthed terracotta figurines of bulls, peacocks, ducks, and also an anthropomorphic figurine. A lot of toy-cart frames made of terracotta were found. The excavation, which is into its fourth year, reveals that Khirsara, which lies on the trade route to Sind (now in Pakistan), was once “a major industrial hub” in western Kutch. The 12-acre site, situated on the outer edge of Khirsara village, sits saucer-like, with mounds on all sides and a depression in the middle and is known locally as “Gadh Wali Wadi”. The Khari river flows nearby and in the distance are the hills of Kutch. A Harappan settlement, belonging to the mature Harappan phase, flourished here for 400 years from circa 2600 BCE to circa 2200 BCE.

“Mature” evidence

The Harappan civilisation can be divided into three phases, early, mature and late. If the early Harappan phase lasted from circa 2800 BCE to circa 2600 BCE, the mature phase was between circa 2600 BCE and circa 1900 BCE. The late phase, including its collapse, lasted from circa 1900 BCE to circa 1500 BCE. Juni Kuran in northern Kutch and Khirsara belong to the mature Harappan phase. And Dholavira, located on the island of Khadir in the Great Rann of Kutch, is an example of a Harappan site that typifies all three phases.

The Harappan civilisation can be divided into three phases, early, mature and late. If the early Harappan phase lasted from circa 2800 BCE to circa 2600 BCE, the mature phase was between circa 2600 BCE and circa 1900 BCE. The late phase, including its collapse, lasted from circa 1900 BCE to circa 1500 BCE. Juni Kuran in northern Kutch and Khirsara belong to the mature Harappan phase. And Dholavira, located on the island of Khadir in the Great Rann of Kutch, is an example of a Harappan site that typifies all three phases.

Jitendra Nath pointed to the important features that make Khirsara a mature Harappan site. “Pre-Harappan pottery and post-Harappan pottery are absent here. The settlements belonging to the early Harappan and late Harappan phases are also not found here,” he said. Besides, Khirsara has thrown up artefacts and structures that make it a mature Harappan settlement. There are massive structures, fortifications, seals with script and carvings of animals, bricks with the standardised ratio of 1:2:4, and a variety of pottery, including reserved slip ware, which is called so because a slip, that is, a coloured coating is applied over the pot after it is finished and dried. Specialists in the study of pottery say that such pottery was reserved for the elite, and hence the name. After the first slip (a coloured coating involving a solution of red ochre, white kaolin or purple or yellow colour) has dried, a second slip is applied over the first coating. When the second slip is wet, an instrument, say, a comb, is run over it to form different patterns. This removes the second coating that comes under the comb’s teeth, making a pattern on the pot, in the form of wavy or straight lines or even checks.

Northern polished black ware (NPBW) is reserved slip ware because it has a silvery or golden coating over it. The NPBW was mostly tableware and the elite used it. The quarry from which the stones were brought to the habitational-cum-industrial site has not been identified yet.

“Seals found in this site belong from the early stage to the late stage of the mature Harappan phase. There are rectangular seals depicting the unicorn and the bison and the Harappan characters. There are rectangular bar-type seals with the Harappan script alone and circular seals, all of which show that Khirsara is a mature Harappan site,” said Jitendra Nath. He argued that seals were the “main characteristic” by which Khirsara could be classified as a mature Harappan site. “We are getting seals from the lowermost level to the uppermost. Pottery, seals and structures are the major hallmarks by which this site could be said to belong to the mature Harappan phase,” he reasoned.

The team encountered five structural phases in the mature Harappan stage itself at Khirsara, said R.N. Kumaran, Assistant Archaeologist, ASI. Floods led to the termination of each phase and evidence of flood deposits was available in the citadel area. “We are getting sand and silt in a continuous band. ‘Kankar’ stones were also available,” said Kumaran.

The structural remains of a fortified settlement revealed a citadel with residential quarters, a warehouse, an industrial-cum-residential complex, habitation annexes and a potters’ kiln, all pointing to systematic town planning. The citadel complex was where the ruling elite lived. It had square and rectangular rooms, verandahs in front, a beautiful staircase leading upstairs and a rock-cut well. The warehouse, 28 metres long and 12 metres wide, has a series of 14 massive parallel walls, which are more than 10 metres long and about 1.5 metres wide. All the structures are built of dressed sandstone blocks, set in mud mortar.

Magnificent artefacts

The artefacts that have been discovered here reinforced the “industrial” nature of the settlement. Among them is a gold hoard, in a small pot, of disc-shaped gold beads, micro gold beads and their tubular counterparts. As Jitendra Nath and this reporter stood on a trench that had been filled up, he pointed to the levelled earth below and said, “It was in this trench that your friend S. Nandakumar [a site supervisor] found the gold hoard.” It was a trench allotted to Nandakumar, and one of the labourers digging the trench came up with a pot that had 26 gold beads inside. “Gold beads are not found in big quantities in the Harappan sites,” Jitendra Nath said. Some disc-shaped gold beads were found at Lothal, a Harappan site in Gujarat.

The artefacts that have been discovered here reinforced the “industrial” nature of the settlement. Among them is a gold hoard, in a small pot, of disc-shaped gold beads, micro gold beads and their tubular counterparts. As Jitendra Nath and this reporter stood on a trench that had been filled up, he pointed to the levelled earth below and said, “It was in this trench that your friend S. Nandakumar [a site supervisor] found the gold hoard.” It was a trench allotted to Nandakumar, and one of the labourers digging the trench came up with a pot that had 26 gold beads inside. “Gold beads are not found in big quantities in the Harappan sites,” Jitendra Nath said. Some disc-shaped gold beads were found at Lothal, a Harappan site in Gujarat.

There are a variety of beads made of shell and steatite and of semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli, agate, carnelian, chert, chalcedony and jasper. About 25,000 steatite beads were found in one trench alone. Shell bangles, shell inlays, copper bangles and rings were also found in plenty. Among copper implements were chisels, knives, needles, points, fish hooks, arrow-heads and weights. There were also bone tools, bone points and beads made out of bones.

“We have found good evidence of bead-making here,” said Jitendra Nath. “We found a lot of drill-bits used for drilling holes in the beads…. We also found stone weights of various denominations. While the smallest weighs five grams, the heaviest is about five kilograms.”

The ASI team found 11 seals, including circular seals. Some of them are carved with unicorn and bison images, and have the Harappan script engraved on them. While the unicorn seal is made of soapstone, the bison seal is made out of steatite. A rare discovery was that of two bar seals, both engraved with the Harappan script only and remarkably intact.

The trenches have yielded a vast amount of reserved slip ware, painted with exquisite designs; a variety of red ware; buff ware, or polished ware; chocolate-coloured slip ware; and grey ware.

Jitendra Nath said: “The kind of antiquities we are getting from this site indicates that Khirsara was a major industrial hub in western Kutch. It was located on a trade route from other parts of Gujarat to Sind in Pakistan, which is about 100 km away. Of course, the Harappans who lived here were basically traders, manufacturing industrial goods for export to distant lands and to other Harappan sites in the vicinity and farther away.”

Fortification

Khirsara is unique among Indus Valley settlements in having a general fortification wall around the settlement and also separate fortification walls around every complex inside the settlement. The citadel complex, the warehouse, the factory-cum-residential complex, and even the potters’ kiln have their own protective walls.

Khirsara is unique among Indus Valley settlements in having a general fortification wall around the settlement and also separate fortification walls around every complex inside the settlement. The citadel complex, the warehouse, the factory-cum-residential complex, and even the potters’ kiln have their own protective walls.

The massive, outer fortification wall still stands in many places, 4,600 years after it was built. It measures 310 metres by 210 metres and is built of partly dressed sandstone blocks set in mud mortar. The wall’s width is 3.4 metres but additional reinforcements in later phases have increased its width considerably. The bedrock below the wall was levelled with clay, sand, grit, lime and thoroughly rammed in to bear the load of the superstructure. Like fortification walls in other Harappan sites, this one also slopes upwards to give it strength and life.

Said Jitendra Nath: “We found three salients on the northern fortification wall of the warehouse. The outer fortification too has salients at regular intervals for giving strength to the wall and for mounting watch.” A protection wall, with a width of 2.34 metres, running parallel to the outer fortification wall, was built on the northern and eastern sides to protect the site when the overflowing Khari river caused flooding.

As the booklet Indus Civilisation brought out in 2010 by the Indus Research Centre, Roja Muthiah Research Library, Chennai, says, the Harappan (or Indus Valley) civilisation “has fascinated not just historians and archaeologists and anthropologists but also experts from such diverse fields such as urban planning, architecture, linguistics, computer science, mathematics, statistics, geology, astrophysics etc.” What fascinated them was “the greatness of this ancient civilisation, its vast extent, its trade links to other regions and its great achievements in the fields of architecture, commerce, fine arts, manufacturing, etc. These are being better understood with every new archaeological find.”

Indus enigma

However, as the booklet says, “The Indus civilisation remains an enigma in some ways. The cause of the sudden fall of the civilisation—renowned for its urban planning, high-quality construction, water management and carefully designed drainage systems—is still not fully understood.” Besides, the Indus script continues to remain undeciphered despite attempts by scholars and researchers.

However, as the booklet says, “The Indus civilisation remains an enigma in some ways. The cause of the sudden fall of the civilisation—renowned for its urban planning, high-quality construction, water management and carefully designed drainage systems—is still not fully understood.” Besides, the Indus script continues to remain undeciphered despite attempts by scholars and researchers.

At its peak, the Harappan civilisation covered an area of 1.5 million square kilometres, across India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran. It extended from Sutkagendor in the Makran coast of Balochistan to Alamgirpur in the east in Uttar Pradesh and from Mandu in Jammu to Daimabad in Ahmednagar district in Maharashtra. Since the 1920s, several hundred Harappan sites have been discovered. After Partition in 1947, when Mohenjardo and Harappa fell in Pakistan, the ASI has discovered many sites in Gujarat, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jammu and Kashmir, and Maharashtra. These sites include Dholavira, Lothal, Juni Kuran, Desalpur, Narappa, Kanmer, Surkotada and Shikarpur in Gujarat; Rakhigarhi, Bhirrana, Banawali and Farmana in Haryana; Alamgirpur, Sanauli and Hulas in Uttar Pradesh; and Kalibangan in Rajasthan.

Discovery of Khirsara

How did the ASI’s excavation branch at Vadodara discover Khirsara? Since most Harappan sites were situated in northern or eastern Kutch, not much was known about the Indus civilisation in western Kutch. Desalpur was the only site excavated there, a minor excavation in the early 1960s. “So we were searching for a Harappan site in western Kutch,” said Jitendra Nath. The Gujarat State Archaeology Department had explored Khirsara in the 1970s, but only a brief report was available on it.

How did the ASI’s excavation branch at Vadodara discover Khirsara? Since most Harappan sites were situated in northern or eastern Kutch, not much was known about the Indus civilisation in western Kutch. Desalpur was the only site excavated there, a minor excavation in the early 1960s. “So we were searching for a Harappan site in western Kutch,” said Jitendra Nath. The Gujarat State Archaeology Department had explored Khirsara in the 1970s, but only a brief report was available on it.

Jitendra Nath’s keen eye, backed by his years of excavation at Taradih in Bodh Gaya, Athirampakkam near Chennai, Ummichipoyil in Kerala, and in other places, came into play. “When we came here, we saw so much of Harappan pottery, along with artefacts such as shell bangles and stone-beads scattered over the surface,” he said. “Then we looked at the site and found it almost intact. We did not have such a big site in western Kutch before. Desalpur was the only other Harappan site in western Kutch.” But Desalpur was excavated for only one season and not much was known about it.

So Jitendra Nath and his team did a survey of Khirsara in 2009 and began excavation in December that year. The ASI team exposed the inner and outer sides of the fortification and found residential structures along the inner side of the fortification.

In the second year (season) of excavation, the team unearthed the citadel and went on to locate the factory area where it found evidence of a lot of industrial activity, including shell-working. There was tell-tale evidence of bead-making. A variety of beads made of copper, shell and terracotta, and semi-precious stones were found in abundance. Copper objects, including needles, knives, fish hooks, arrowheads and weights were found. What is puzzling is that no copper figurines of animals, as found in other sites, were found here.

When the ASI team dug up a mound, it encountered evidence of a five-metre-deep structure, going back to 2600 BCE. This earliest structure was made of stones with mud bricks used in between.

In the third year, the team excavated the residential complex in the citadel. The citadel was strategically located adjacent to the warehouse and the factory site in such a manner that the elite class might exercise full control over the manufacturing and trading activities. A five-metre-broad pathway led from the citadel to the industrial complex. The citadel complex was 90 metres by 90 metres and about a hundred people could have lived there. There were interconnected rooms, door sills, hearths, and so on. The houses had bathrooms with an outlet for water to flow. Streets inside the citadel were rammed with clay and household waste such as potsherds, bones, shell debitage and grits. A pot burial, containing charred bones and ash kept inside a circular hearth, was found inside a room. The ASI is yet to excavate a large area of the residential complex, but it may do so in the next season.

Bipin Negi, Assistant Archaeologist, ASI, pointed to the perfect manner in which the fortification wall around the citadel was built and how it had withstood the ravages of time. It is a tall, sloping wall, several metres in height. “This citadel wall is much broader than the general fortification wall. It is set in mud mortar, which is sticky clay. The wall has been standing for 4,600 years,” said Negi.

As we went around the trenches that had exposed the industrial-cum-residential complex, Kumaran explained how it had been identified as a factory site. “We have found furnaces and a tandoor. There is evidence of copper-working and ash. We have found huge quantities of steatite beads and some seals made of steatite. From all this evidence, we have identified it as a fortified factory site.” He led us to the entrance of the fortification wall of the industrial-cum-residential complex. The entrance was in the south. Akin to other Harappan sites, there were large limestone slabs at the entrance; the slabs obviously served as doormats. There were a couple of small guard rooms adjacent to the entrance. Residences inside the industrial complex, too, had stone slabs at the entrance. There were bathrooms, with sloping slabs used on the floor for water to flow into covered outlets. The outlets led into the drains in the street.

To the sheer delight of the ASI team, the warehouse came into view when they excavated the north-east corner of the site last year. Excavation of the warehouse, which has continued this year, has revealed it to be a massive structure with 14 parallel walls. Jitendra Nath said, “It must have been a multipurpose warehouse for storing goods meant for export and grains. A warehouse is a rare type of structure found in a few Harappan sites. It indicates a state of surplus economy and is a sign of prosperity. You build such structures for storing goods for export or goods that have been imported.” The parallel walls supported a superstructure made of wood and daub and goods were stored in the superstructure. The pathways between the parallel walls were air ducts to keep the goods fresh. The entrance had a series of guard rooms adjacent to it. The ASI found grains in the warehouse and samples of these grains have been sent to Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany, Lucknow, for investigation and identification.

Potters’ kiln

Situated on the outer side of the general fortification wall, the potters’ kiln is a bit of an engineering marvel. Negi pointed out that its fire chamber had been cut out of both bedrock and earth, and a dome sat on the fire chamber. The freshly made pots were arranged inside the dome and a passage led to the fire chamber. It was through the passage that the burning logs were pushed inside the fire chamber. The circular wall of the fire chamber had holes for air circulation and oxygenation. The burning logs generated heat of about 500 Celsius and the pots were baked.

Situated on the outer side of the general fortification wall, the potters’ kiln is a bit of an engineering marvel. Negi pointed out that its fire chamber had been cut out of both bedrock and earth, and a dome sat on the fire chamber. The freshly made pots were arranged inside the dome and a passage led to the fire chamber. It was through the passage that the burning logs were pushed inside the fire chamber. The circular wall of the fire chamber had holes for air circulation and oxygenation. The burning logs generated heat of about 500 Celsius and the pots were baked.

The ASI has not located the reservoirs which would have supplied water to the Harappan settlement at Khirsara. Jitendra Nath said, “Maybe, when we excavate more, we will find water bodies. The western half of the site has not been excavated yet. We have been concentrating mostly on the eastern half. We may dig the western half next year.” Kumaran was hopeful about the “possibility” of the existence of a reservoir because “we have found drains at a depth of 1.5 metres and paved stone flooring. It was not for carrying sullage.” There was also a rock-cut well in the residential quarters within the citadel. There were chances of encountering a reservoir if the excavation continued for two or three years. Jitendra Nath was confident that “a complete picture of the site will emerge only when we excavate more and more”.

Printable version | May 31, 2016 7:21:58 AM | http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/heritage/discovering-khirsaras-harappan-glory/article4794614.ece

River Saraswati Myth or Reality ?

In March- April 2015, Haryana government announced to start the excavation of the mythical Saraswati river from Adi Badri, the point from where it is said to have originated. The team working on reviving the Saraswati River in Yamunanagar district found strong water current on reaching a depth of seven-feet today. Haryana assembly Speaker Kanwar Pal in April 2015 inaugurated the excavation work on the Rs 50-crore 'Saraswati Revival Project' at Rolaheri village in Yamunanagar district. Scientists got an inkling of the presence of the Saraswati two decades ago, when satellite photographs showed presence of underground water around Jaisalmer and its flow had a definite pattern. When they tallied scientific data with the ancient literature, they were convinced about the existence of Saraswati. There are indications that these channels were formed by the river Saraswati, that is mentioned in the RigVeda and as well as in the Mahabharata.

✹ HOW WAS RIVER SARASWATI RE-DISCOVERED? (Article Taken from Educators' Society for Heritage of India)

The modern quest for the Sarasvati began in the 1970s when American satellite images showed traces of water channels in northern and western India that had disappeared long ago. Thereafter, Dr. Vakankar together with Moropant Pingle established the invisible river’s route through satellite imagery and archaeological sites along its route. The Sarasvati project was vetted and cleared by eminent archaeologists and geologists, and an earnest search for the lost river launched in 1982.

For instance, in 1995, scientists of the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) found that water was available in the Rajasthan desert at depths of merely 50 to 60 metres, as a result of which agriculture was possible even in the extreme summer months. The Central Arid Zone Research Institute (#CAZRI),#Jodhpur, mapped the defunct course of a river through satellite and aerial photographs and field studies. In fact, satellite imagery has given the river scientific teeth. It seems to have originated in Kailash Mansarovar and emerged on the plains from the Shiwalik Hills at the foothills of the Himalayas in Himachal Pradesh, flowed through the Ghaggar valley in#Haryana and the Rajasthan desert, on to Hakra in the Cholistan desert (Sindh, Pakistan), before reaching the Rann of Kutch through the Nara Valley and falling off into the Arabian Sea.

Since the Ghaggar Valley is eight to twelve kilometers wide at many places, it is obvious the#Sarasvati was truly a great river. Earthquakes and floods changed the course of the Ghaggar and its tributaries frequently, and satellite imagery together with ground morphological studies confirm that it too originated in the Siwalik Himalayas before flowing into the Arabian Sea. This was the ‘lost’ Sarasvati. Scientific studies suggest it dried up around 2000 BC, which makes it a contemporary of the Saraswati-Sindhu civilization, and gives the Rig Veda a greater antiquity than previously suspected, as the Sarasvati was a powerful river when the seers composed the Vedic mantra-s.

After Dr. Wakankar’s demise in 1996, the Vedic_Sarasvati_Nadi_Shodh_Pratishthaan, Jodhpur (regd.) continued the project, by roping in the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), whose chairman Dr. Kasturi Rangan and Regional Remote Sensing Services Centre (RRSSC) director Dr. J.R. Sharma displayed a gratifying interest in the project. The Jodhpur RRSSC conducted three major scientific seminars on the subject and analyzed satellite images of IRS 1-century, thus mapping the entire coarse from Kailash Mansarovar To Gujarat.

Meanwhile, after the Pokharan blasts on 11 May 1998, the Isotope Division of the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) led by Dr. S.L. Rao took water samples from 800 deep wells within a radius of 250 kms. of Pokharan. Their findings, published in Current Science, showed there was no nuclear contamination of the ground-waters. Normally, when a neutron or hydrogen bomb implodes (3 bombs were imploded), huge amounts of tritium (an isotope of hydrogen H3) are released. Yet the tests showed very small traces of tritium, which are normally found in any body of water together with H2O, a tribute to the meticulous care with which Indian scientists conducted the tests.

BARC also made some amazing discoveries. First, the waters tested were potable; second, they derived from Himalayanglaciers; third, they were between 8000 to 14000 years old; and finally, the waters were being slowly recharged through aquifers from somewhere in the north despite the fact that records showed only very scanty rainfall in the semi-arid region of Marusthali. BARC thus confirmed ISRO findings about the river, and this was unintended fallout of Pokharan!

Archaeologists from the ShimlaCircle did excellent work in 2003-2004, reporting three sites and a Buddha vihara in Adi Badri alone. Dr. Vijay Mohan Kumar Puri, an expert on Himalayan glaciers, reported finds of metamorphic rocks on the terraces created by Himalayan glacial River Sarasvati and proved that Adi Badri was the site where the river entered the plains from its Himalayan home. Adi_Badriis just 20 kms. from Jagadhri (Yamuna Nagar) and 70 kms. from Dehradun (Paonta Saheb) or Kurukshetra. Further, Dr. Puri proved the origins of Sarasvati from Rupin-Supin glaciers north of Paonta Saheb, where a Yamuna tear occurred on account of plate tectonics and caused a lateral shift of the Shiwalik ranges and consequent eastward migration of the Yamuna, a tributary of Sarasvati, taking the Sarasvati waters to join the Ganga at Prayag and create the Triveni Sangam.

These excavations proved that Adi Badri was the spot where a Himalayan glacial river entered the plains. The Sarasvati originated from the Svargarohini glacier mountain. Already the revived river has reached upto Danan in Barmer, Rajasthan, and will reach the Rann of Kutch in a few years. Plans are already afoot to take it upto the Sabarmati with S'arada (Mahakali-Karnali) river glacial runoffs. Given the magnitude of the findings, scholars like Dr. Karan Singh and Dr. Kasturi Rangan suggested the Ministry for Culture examine the Vedic texts and the work done by ISRO to prove the course of the River Sarasvati.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

✹ REBIRTH OF RIVER SARASVATI AND NATIONAL WATER GRID Projects related to the re-discovery of Vedic River Sarasvati have been transformed as projects to revive the great river to fulfill the water supply needs of 20 crore people in Northwest India and to make the Thar_desert fertile again. These projects have also led to the demand for a National Water Grid to make every river of India a perennial river and provide water for everyone, for generations to come.

Dr. D.K. Chaddha, Chairman, Central Groundwater Authority, Union Ministry of Water Resources, validated BARC findings of potable water 30 to 60 m. below the ground, through ground morphological studies. A Rs. five crore Sarasvati Project was sanctioned to drill test tubewells along the identified course. ISRO locatedthe test sites on the basis of a palaeo-channel (old course) shown in satellite images; the existence of a tectonic fault line; and the proximity to an archaeological site.

Dr. S. Kalyanaraman, director, Sarasvati Nadi Shodh Prakalp, author of a seven-volume encyclopedic study of the river, pointed out that there are over 2,000 archaeological sites along the banks of the Sarasvati as compared to only 600 on the banks of Sindhu. The sites identified by ISRO were drilled in 25 places, with special drilling equipment from Japan, in order to precisely position the drills based on latitude and longitude data provided on toposheets. Barring one drilling due to faulty positioning of the drill, all explorations were successful and yielded sustainable tube wells at a depth of merely 30 to 60 meters, with potable water. Dr. K.R. Srinivasan, Director, Central Groundwater Board, explained in a detailed monograph that it was possible to create one million sustainable tube wells in central Rajasthan alone of the Sarasvati River basin, a project taken up by the state Government.

Sustainability of these tube wells necessitates a recharge through the surface waters of the Rajasthan Canal, which is being extended into Gujarat. In turn, Gujarat will share some Narmada waters with Rajasthan. It is an irony that while Punjab and Haryana dispute over the Sutlej-Yamuna link canal (SYL), Punjab has been forced to release waters into the Sarasvati Mahaanadi Roopaa Nahar in order to save the dams which are located on fault-lines criss-crossing the entire Sutlej-Beas river basin, on account of ongoing plate tectonic activity. Thus, waters are flowing in the 40 feet wide, 12 feet deep Sarasvati nahar, causing the sand dunes to disappear as the banks of the reborn Sarasvati are greened by forests! Nearly 10 lakh acres of land has already been brought under cultivation.

At present, State Governments are showing more interest in the Sarasvati than the Centre. In October 2004, a Sarasvati Sarovar in Haryana was dedicated to the nation, and on Karthik Purnima the following month itself, more than two lakh pilgrims took a sacred dip in the waters of the 83 m. long, 83 m. wide and 11 ft. deep Sarovar. The waters were harvested through eleven check dams, an example of water-shed management and also ecological conservation of forests, apart from the development of a Vedic herbal garden.As of now, it will take about two years for the waters of the Sarasvati to reach Gujarat. The interlinking of rivers as part of the National Water Grid is also presently left mainly to the initiative of State Governments, as witnessed in the moves to start Kali-Parbati Sindh-Chambal and Ken-Betwa link projects. A revivified Sarasvati has the power to magically transform the face of north-western India. The river will flow up to Sabarmati (Ahmedabad) river once the Mahakali-Karnali-Sharada waters are transported across an aqueduct over the Yamuna and linked with the Sarasvati.