The narrative is set of hieroglyphs read rebus. Rebus readings connote that the cylinder seal impressions on the proto-cuneiform tablet relate to the smelting furnace for metalware:

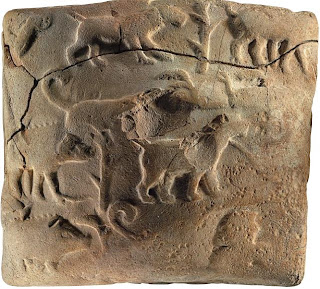

pasara 'quadrupeds' Rebus: pasra 'smithy' (Santali)

1. a tiger, a fox on leashes held by a man kol 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron, alloys' lo ‘fox’ (WPah.) Rebus: lōha ʻmetalʼ (Pali)

2. a procession of boars (rhinoceros?) and tiger in two rows kāṇṭā 'rhinoceros. Rebus: āṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’ (Gujarati)3. a stalk/twig, sprout (or tree branch) kūdī, kūṭī bunch of twigs (Sanskrit) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace‘ (Santali)

Thanks to Abdallah Kahil for the line drawing which clearly demonstrates that the narrative is NOT 'a hunting with dogs or herding boars in a marsh environment.' Traces of hieroglyphs are found on both sides of the tablet which also contains a proto-cuneiform inscription. It is noteworthy that cuneiform evolved TOGETHER WITH the use of Indus writing hieroglyphs on tablets, cylinder seals and other artifacts. I wish every success for efforts at decoding proto-elamite script using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) System (see below).

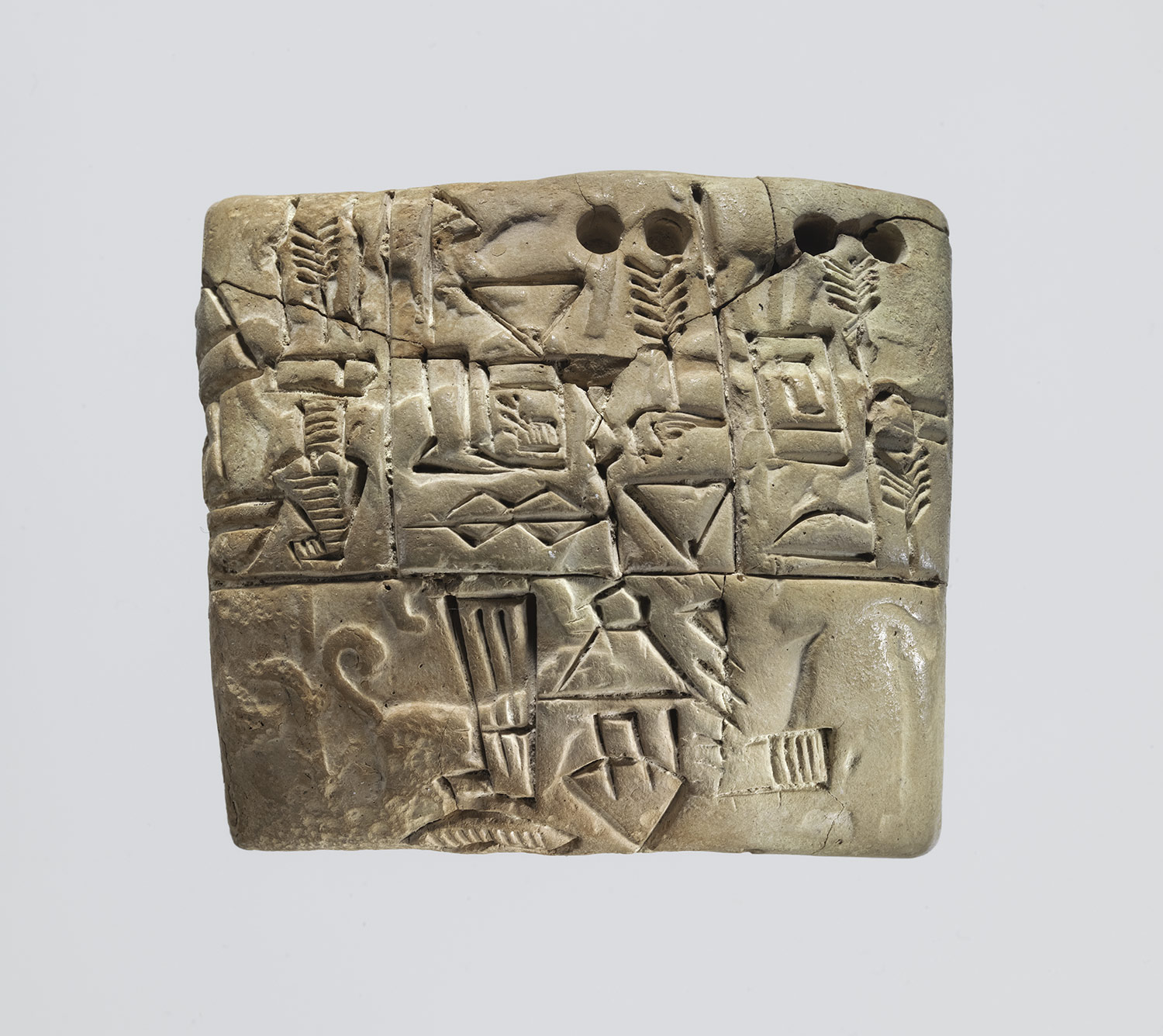

Fig. 24 Line drawing showing the seal impression on this tablet. Illustration by Abdallah Kahil. Proto-Cuneiform tablet with seal impressions. Jemdet Nasr period, ca. 3100-2900 BCE. Mesopotamia. Clay H. 5.5 cm; W.7 cm. The blurb of Metropolitan Museum of Art says "The seal impression depicts a male figure guiding two dogs on a leash and hunting or herding boars in a marsh environment."

Comparable are hieoroglyphs of jackals appear where tigers are normally shown on a tablet h1971B Harappa. Three tablets with identical glyphic compositions on both sides: h1970, h1971 and h1972. Seated figure or deity with reed house or shrine at one side. Left: H95-2524; Right: H95-2487. Planoconvex molded tablet found on Mound ET. Reverse. a female deity battling two tigers and standing above an elephant and below a six-spoked wheel.

Boar or rhinoceros in procession. Cylinder seal impression: Rhinoceros, elephant, lizard (gharial?).Tell Asmar (Eshnunna), Iraq. IM 14674; glazed steatite. Frankfort, 1955, No. 642; Collon, 1987, Fig. 610. ![]()

A group of animal hieroglyphs (including tiger/jackal, rhinoceros/boar) are show on many tablets with Indus writing : m2015Am2015Bm2016Am1393tm1394tm 1395Atm1395Bt

A group of animal hieroglyphs (including tiger/jackal, rhinoceros/boar) are show on many tablets with Indus writing : m2015Am2015Bm2016Am1393tm1394tm 1395Atm1395BtMeluhha (mleccha) lexemes and rebus readings:

Stalk: காண்டம் kāṇṭam , n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர். துருத்திவா யதுக்கிய குங்குமக் காண் டமும் (கல்லா. 49, 16). 2. Staff, rod; கோல். (சூடா.) 3. Stem, stalk; அடித்தண்டு. (யாழ். அக.) 4. Arrow; அம்பு. (சூடா.) 5. Weapon; ஆயுதம். (சூடா.) Collection, multitude, assemblage; திரள். (அக. நி.) கண்டானுமுண்டானும் kaṇṭāṉumuṇṭ- āṉum, n. Redupl. of கண்டானும். Household utensils, great and small, useful and useless; வீட்டுத் தட்டுமுட்டுகள். கண்டானு முண்டானும் இத் தனை எதற்கு? Loc. Alternative 1: aḍaru twig; aḍiri small and thin branch of a tree; aḍari small branches (Ka.); aḍaru twig (Tu.)(DEDR 67). Rebus: aduru‘native, unsmelted metal’ (Kannada) aduru‘gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru’, that is, ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) Alternative 2: kūdī, kūṭī bunch of twigs (Skt.lex.) kūdī (also written as kūṭī in manuscripts) occurs in the Atharvaveda (AV 5.19.12) and Kauśika Sūtra (Bloomsfield’s ed.n, xliv. Cf. Bloomsfield, American Journal of Philology, 11, 355; 12,416; Roth, Festgruss an Bohtlingk, 98) denotes it as a twig. This is identified as that of Badarī, the jujube tied to the body of the dead to efface their traces. (See Vedic Index, I, p. 177). Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace‘ (Santali)Boar. Allograph: ‘rhinoceros’: gaṇḍá4 m. ʻ rhinoceros ʼ lex., °aka -- m. lex. 2. *ga- yaṇḍa -- . [Prob. of same non -- Aryan origin as khaḍgá --1: cf. gaṇōtsāha -- m. lex. as a Sanskritized form ← Mu. PMWS 138]1. Pa. gaṇḍaka -- m., Pk. gaṁḍaya -- m., A. gãr, Or. gaṇḍā. 2. K. gö̃ḍ m., S. geṇḍo m. (lw. with g -- ), P. gaĩḍā m., °ḍī f., N. gaĩṛo, H. gaĩṛā m., G. gẽḍɔ m., °ḍī f., M. gẽḍā m.Addenda: gaṇḍa -- 4. 2. *gayaṇḍa -- : WPah.kṭg. geṇḍɔ mirg m. ʻ rhinoceros ʼ, Md. genḍā ← H. (CDIAL 4000). காண்டாமிருகம் kāṇṭā-mirukam , n. [M. kāṇṭāmṛgam.] Rhinoceros; கல்யானை. (Tamil) Rebus: kāṇḍa‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’ (Gujarati)

kol ‘tiger, jackal’ (Kon.) Rebus: kol ‘iron’ (Ta.)

kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Te.) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.)Pk. Kolhuya -- , kulha — m. ʻ jackal ʼ < *kōḍhu -- ; H.kolhā, °lā m. ʻ jackal ʼ, adj. ʻ crafty ʼ; G. kohlũ, °lũ n. ʻ jackal ʼ, M. kolhā, °lā m. krōṣṭŕ̊ ʻ crying ʼ BhP., m. ʻ jackal ʼ RV. = krṓṣṭu — m. Pāṇ. [√kruś] Pa. koṭṭhu -- , °uka — and kotthu -- , °uka — m. ʻ jackal ʼ, Pk. Koṭṭhu — m.; Si. Koṭa ʻ jackal ʼ, koṭiya ʻ leopard ʼ GS 42 (CDIAL 3615). कोल्हा [ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [ kōlhēṃ ] A jackal (Marathi) Rebus: kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pañcaloha’ (Ta.) Allograph: kōla = woman (Nahali)

Rebus: kol , n. < கொல்-. Working in iron; கொற்றொழில். 4. Blacksmith; கொல்லன். கொல்லன் kollaṉ , n. < கொல்². [M. kollan.] Blacksmith; கருமான். மென்றோன்மிதியுலைக்கொல்லன் (பெரும்பாண். 207). கொற்றுறை koṟṟuṟai , n. < கொல்² + துறை. Blacksmith's workshop, smithy; கொல்லன் பட் டடை. கொற்றுறைக் குற்றில (புறநா. 95). கொற்று¹ koṟṟu , n. prob. கொல்-. 1. Masonry, brickwork; கொற்றுவேலை. கொற்றுள விவரில் (திரு வாலவா. 30, 23). 2. Mason, bricklayer; கொத் தன். Colloq. 3. The measure of work turned out by a mason; ஒரு கொத்தன் செய்யும் வேலை யளவு. இந்தச் சுவர் கட்ட எத்தனை கொற்றுச் செல்லும்?

lōpāka m. ʻa kind of jackalʼ Suśr., lōpākikā -- f. lex. 1. H. lowā m. ʻfoxʼ.2. Ash. ẓōki, žōkī ʻfoxʼ, Kt. ŕwēki, Bashg. wrikī, Kal.rumb. lawák: < *raupākya -- NTS ii 228; -- Dm. rɔ̈̄pak ← Ir.? lōpāśá m. ʻfox, jackalʼ RV., lōpāśikā -- f. lex. [Cf. lōpāka -- . -- *lōpi -- ] Wg. liwášä, laúša ʻfoxʼ, Paš.kch. lowóċ, ar. lṓeč ʻjackalʼ (→ Shum. lṓeč NTS xiii 269), kuṛ. lwāinč; K. lośu, lōh, lohu, lôhu ʻporcupine, foxʼ.1. Kho. lōw ʻfoxʼ, Sh.gil. lótilde;i f., pales. lṓi f., lṓo m., WPah.bhal. lōī f., lo m.2. Pr. ẓūwī ʻfoxʼ.(CDIAL 11140-2).Rebus: lōhá ʻred, copper -- colouredʼ ŚrS., ʻmade of copperʼ ŚBr., m.n. ʻcopperʼ VS., ʻironʼ MBh. [*rudh -- ] Pa. lōha -- m. ʻmetal, esp. copper or bronzeʼ; Pk. lōha -- m. ʻironʼ, Gy. pal. li°, lihi, obl. elhás, as. loa JGLS new ser. ii 258; Wg. (Lumsden) "loa" ʻsteelʼ; Kho. loh ʻcopperʼ; S. lohu m. ʻironʼ, L. lohā m., awāṇ. lōˋā, P. lohā m. (→ K.rām. ḍoḍ. lohā), WPah.bhad. lɔ̃u n., bhal. lòtilde; n., pāḍ. jaun. lōh, paṅ. luhā, cur. cam. lohā, Ku. luwā, N. lohu, °hā, A. lo, B. lo, no, Or. lohā, luhā, Mth. loh, Bhoj. lohā, Aw.lakh. lōh, H. loh, lohā m., G. M. loh n.; Si. loho, lō ʻ metal, ore, iron ʼ; Md. ratu -- lō ʻ copper lōhá -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) lóɔ ʻironʼ, J. lohā m., Garh. loho; Md. lō ʻmetalʼ. (CDIAL 11158).

Read on a write-up on the proto-cuneiform tablet... [quote] Administrative tablet with cylinder seal impression of a male figure, hunting dogs, and boars, 3100–2900 B.C.; Jemdet Nasr period (Uruk III script)

Mesopotamia ClayH. 2 in. (5.3 cm) Purchase, Raymond and Beverly Sackler Gift, 1988 (1988.433.1) ON VIEW: GALLERY 402 Last Updated April 26, 2013 In about 3300 B.C., writing was invented in Mesopotamia, perhaps in the city of Uruk, where the earliest inscribed clay tablets have been found in abundance. This was not an isolated development but occurred during a period of profound transformation in politics, the economy, and representational art. During the Uruk period of the fourth millennium B.C., the first Mesopotamian cities were settled, the first kings were crowned, and a range of goods—from ceramic vessels to textiles—were mass-produced in state workshops. Early writing was used primarily as a means of recording and storing economic information, but from the beginning a significant component of the written tradition consisted of lists of words and names that scribes needed to know in order to keep their accounts. Signs were drawn with a reed stylus on pillow-shaped tablets, most of which were only a few inches wide. The stylus left small marks in the clay which we call cuneiform, or wedge-shaped, writing.

This tablet most likely documents grain distributed by a large temple, although the absence of verbs in early texts makes them difficult to interpret with certainty. [unquote] http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1988.433.1

Pre-cuneiform tablet with seal impressions

The imagery of the cylinder seal records information. A male figure is guiding dogs (?Tigers) and herding boars in a reed marsh. Both tiger and boar are Indus writing hieroglyphs, together with the imagery of a grain stalk. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha),of Indian sprachbund in the context of metalware catalogs of bronze age. kola 'tiger'; rebus: kol 'iron'; kāṇḍa 'rhino'; rebus: kāṇḍa 'metalware tools, pots and pans'. Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330) Alternative rebus: If the imagery of stalk connoted a palm-frond, the rebus readings could have been:

The imagery of the cylinder seal records information. A male figure is guiding dogs (?Tigers) and herding boars in a reed marsh. Both tiger and boar are Indus writing hieroglyphs, together with the imagery of a grain stalk. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha),of Indian sprachbund in the context of metalware catalogs of bronze age. kola 'tiger'; rebus: kol 'iron'; kāṇḍa 'rhino'; rebus: kāṇḍa 'metalware tools, pots and pans'. Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330) Alternative rebus: If the imagery of stalk connoted a palm-frond, the rebus readings could have been: Ku. N. tāmo (pl. ʻ young bamboo shoots ʼ), A. tām, B. tã̄bā, tāmā, Or. tambā, Bi tã̄bā, Mth. tām, tāmā, Bhoj. tāmā, H. tām in cmpds., tã̄bā, tāmā m. (CDIAL 5779) Rebus: tāmrá ʻ dark red, copper -- coloured ʼ VS., n. ʻ copper ʼ Kauś., tāmraka -- n. Yājñ. [Cf. tamrá -- . -- √tam?] Pa. tamba -- ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻ copper ʼ, Pk. taṁba -- adj. and n.; Dm. trāmba -- ʻ red ʼ (in trāmba -- lac̣uk ʻ raspberry ʼ NTS xii 192); Bshk. lām ʻ copper, piece of bad pine -- wood (< ʻ *red wood ʼ?); Phal. tāmba ʻ copper ʼ (→ Sh.koh. tāmbā), K. trām m. (→ Sh.gil. gur. trām m.), S. ṭrāmo m., L. trāmā, (Ju.) tarāmã̄ m., P. tāmbā m., WPah. bhad. ṭḷām n., kiũth. cāmbā, sod. cambo, jaun. tã̄bō (CDIAL 5779) tabāshīr तबाशीर् । त्वक््क्षीरी f. the sugar of the bamboo, bamboo-manna (a siliceous deposit on the joints of the bamboo) (Kashmiri)

Source: Kim Benzel, Sarah B. Graff, Yelena Rakic and Edith W. Watts, 2010, Art of the Ancient Near East, a resource for educators, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

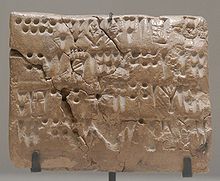

http://www.metmuseum.org/~/media/Files/Learn/For%20Educators/Publications%20for%20Educators/Art%20of%20the%20Ancient%20Near%20East.pdfAn example of a proto-Elamite accounting tablet. The direction of reading is right-to-left, then downward when the end of line is reached.

Economic tablet with numeric signs. Proto-Elamite script in clay, Susa, Uruk period (3200 BC to 2700 BC). Department of Oriental Antiquities, Louvre.

Economic tablet with numeric signs. Proto-Elamite script in clay, Susa, Uruk period (3200 BC to 2700 BC). Department of Oriental Antiquities, Louvre. Tablet with numeric signs and script. From Teppe Sialk, Susa, Uruk period (3200 BC to 2700 BC). Department of Oriental Antiquities, Louvre.

Tablet with numeric signs and script. From Teppe Sialk, Susa, Uruk period (3200 BC to 2700 BC). Department of Oriental Antiquities, Louvre. Clay tokens, from Susa, Uruk period, circa 3500 BC. Department of Oriental Antiquities, Louvre.

Clay tokens, from Susa, Uruk period, circa 3500 BC. Department of Oriental Antiquities, Louvre. Seal excavated at Susa, now in modern-day Iran, showing an account of five fields and their yields, with total on the reverse. Faculty of Oriental Studies, Oxford,

Seal excavated at Susa, now in modern-day Iran, showing an account of five fields and their yields, with total on the reverse. Faculty of Oriental Studies, Oxford,  Syllabograms of Elamite script. "The discovery of a bilingual text, with one version in Linear Elamite and the other in Old Akkadian, in 1905 at the Elamite capital of Susa made it possible to partially decipher Linear Elamite. The system is discovered to frequently make use of syllabograms, with logograms sprinkled in. The following is the Elamite portion of the bilingual tablet, which is attributed to the Elamite king Puzur-Inshushinak around the 22th century BCE."eal excavated at Susa, now in modern-day Iran, showing an account of five fields and their yields, with total on the reverse. Faculty of Oriental Studies,

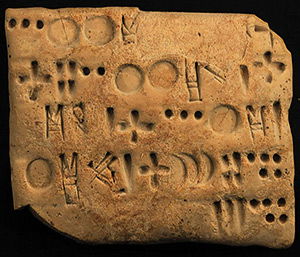

Syllabograms of Elamite script. "The discovery of a bilingual text, with one version in Linear Elamite and the other in Old Akkadian, in 1905 at the Elamite capital of Susa made it possible to partially decipher Linear Elamite. The system is discovered to frequently make use of syllabograms, with logograms sprinkled in. The following is the Elamite portion of the bilingual tablet, which is attributed to the Elamite king Puzur-Inshushinak around the 22th century BCE."eal excavated at Susa, now in modern-day Iran, showing an account of five fields and their yields, with total on the reverse. Faculty of Oriental Studies,  Tablet Sb04823: receipt of 5 workers(?) and their monthly(?) rations, with subscript and seal depicting animal in boat; excavated at Susa in the early 20th century; Louvre Museum, Paris (Image courtesy of Dr Jacob L. Dahl, University of Oxford) Cited in an article on Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) System.

Tablet Sb04823: receipt of 5 workers(?) and their monthly(?) rations, with subscript and seal depicting animal in boat; excavated at Susa in the early 20th century; Louvre Museum, Paris (Image courtesy of Dr Jacob L. Dahl, University of Oxford) Cited in an article on Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) System. The tablet illustrated here is a business document with a seal impression. Seal impressions are somewhat like signatures, in that they identify the person involved in the business transaction recorded on the tablet. While most of the tablets that have been found are such things as contracts, sales receipts, and tax records, a number of very important literary texts have been found as well, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Code of Hammurabi. Photograph by Kai Quinlan West Semitic Research Courtesy University of Southern California Archaeological Research Collection http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/educational_site/ancient_texts/Cuneiform.shtml

The tablet illustrated here is a business document with a seal impression. Seal impressions are somewhat like signatures, in that they identify the person involved in the business transaction recorded on the tablet. While most of the tablets that have been found are such things as contracts, sales receipts, and tax records, a number of very important literary texts have been found as well, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Code of Hammurabi. Photograph by Kai Quinlan West Semitic Research Courtesy University of Southern California Archaeological Research Collection http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/educational_site/ancient_texts/Cuneiform.shtmlSee:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/tokens-and-bullae-evolve-into-indus.html Tokens and bullae evolve into Indus writing, underlying language-sounds read rebus

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/see-httpbharatkalyan97.html Indus writing in ancient Near East (Dilmun seal readings)

Note on the copulation scenes on Dilmun seals:

kamḍa, khamḍa 'copulation' (Santali) Rebus:kaṇḍa ‘furnace, fire-altar, consecrated fire’.

Allograph: kamaḍha ‘penance’ (Pkt.) Rebus 1: kampaṭṭa ‘mint’ (Ma.) Rebus 2: kaṇḍa‘fire-altar' (Santali); kan‘copper’ (Ta.)

Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

June 3, 2013