Eight mostly cire perdue bronze artifacts dated to ca. 4th m.BCE are presented.

pasara 'animals' rebus: pasra 'smithy, forge'

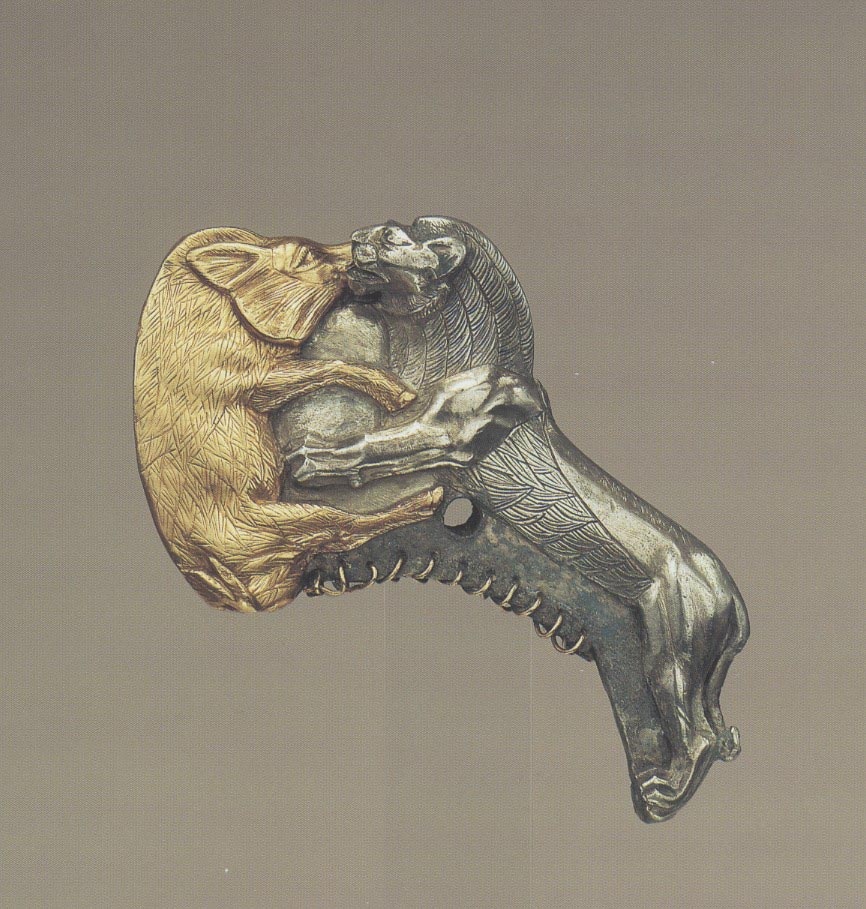

Boar

baḍhia = a castrated boar, a hog; rebus: baḍhi 'a caste who work both in iron and wood' badiga 'artificer' (Kannada)

Jackal

Winged Tiger

krōṣṭŕ̊ ʻ crying ʼ BhP., m. ʻ jackal ʼ RV. = krṓṣṭu -- m. Pāṇ. [√

Double-headed Eagle Anthropomorph

(Powerful hero, Shulgi) Two birds and feathers

Śyena, śen, śenī 'thunderbolt, falcon' [vájra -- , aśáni -- ]Aw. bajāsani m. ʻ thunderbolt ʼ prob. ← Sk.(CDIAL 11207) asani signifies 'thunderbolt,lightning' (Pali); aśáni 'thunderbolt' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: duul 'metal casting'; thus, together rebusآهن ګر āhan gar, '

Lion (Signifies goldsmith working with superior gold

Goat, markhor

melh,mr̤eka 'goat or antelope' rebus: milakkhu, mleccha 'copper'.

miṇḍāl 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) koṭe meṛed = forged iron

Bull + mudhif

पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' as hieroglyph is read rebus: pōḷa, 'ferrite ore,magnetite ore' PLUS munda, 'temple' (Toda) Rebus: munda 'iron'

Three worshippers

kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS bhaṭa 'adorant' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'

Portable gold furnace Stand bearer

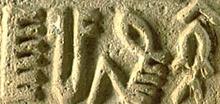

Stamp seal of the Elamites (who lived in the region now known as Khuzistan, Iran) represented a hunting scene old 5,500 years, preceding the Sumerians by 300/500 years.

https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=10220314176956360&set=gm.897980764036057 (Note: could be jackals and boar)

Shaft-hole Axe Head with a Bird-Headed Demon, a Boar, and a Dragon in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Silver, gold foil

Central Asia (Bactria- Margiana)

Late 3rd- early 2nd millennium BC

Accession # 1982.5

The bird-headed demon depicted on both sides of the axe (rather than being double-headed) holds a winged dragon in one claw and a boar, which forms the cutting edge of the axe, in the other. The image possibly represents the bird-demon as a hero mastering chaos in the form of the boar and the dragon.

Ceremonial axe. Sumer. Silver, part with gold sheet

Ceremonial axe. Sumer. Silver, part with gold sheetMax. L: 12.68 cm

Allegedly from North Afghanistan

Bactrian

Late 3rd/early 2nd millennium B.C.

The whole cast by the lost wax process. The boar covered with a sheet of gold annealed and hammered on, some 3/10-6/10 mm in thickness, almost all the joins covered up with silver. At the base of the mane between the shoulders an oval motif with irregular indents. The lion and the boar hammered, elaborately chased and polished. A shaft opening - 22 holes around its edge laced with gold wire some 7/10-8/10 mm in diameter - centred under the lion's shoulder; between these a hole (diam: some 6.5 mm) front and back for insertion of a dowel to hold the shaft in place, both now missing.

Condition: a flattening blow to the boar's backside where the tail curled out and another to the hair between the front of his ears, his spine worn with traces of slight hatching still visible, a slight flattening and wear to his left tusk and lower left hind leg. A flattening and wear to the left side of the lion's face, ear, cheek, eye, nose and jaw and a flattening blow to the whole right forepaw and paw. Nicks to the lion's tail. The surface with traces of silver chloride under the lion's stomach and around the shaft opening.

The closest parallel stylistically is the famous silver axe in New York [1] with an almost identical shaft opening, but laced with silver wire, and hole for the dowel. The boar is less realistic, a hanging posture somewhat unnatural with a distortion to the front section of the upper part of its spine, to fit the function of the axe head and blend in with the rest. On our example the posture is naturalistic as would befit a dead boar. The eyes of both bear a similarity and their tails end in two separate tufts [2].

The New York axe is ritualistic and clearly thematic as it illustrates some myth, saga or religious belief which may explain a certain stiffness. For another wild boar, but with a tiger, his stripes inlaid in silver, and a goat, there is the bronze axe in London [3], very different for the shaft opening and mode of attachment with its multiple rivet holes and rivets. The eyes are shaped as round holes and were possibly once inlaid.

There is a fourth axe [4] with a boar in similar posture, in bronze - attacked from below by two lions, their hindquarters attached to a cylindrical shaft with a projection on its other side.

Shaft hole axes were made throughout the Near East over a long period. P. Amiet fully describes the considerable exchange of metalwork that took place towards the end of the 3rd millennium B.C. throughout vast expanses of Greater Iran. T. Potts tells us that the Sumerian examples are consistently plain whereas the more elaborate types are from the Luristan, Kerman/Lut and Bactrian regions. Luristan examples and others further east have animals in high relief along the butt, whereas Bactrian hammers and axes have an animal protome projecting from it. He further adds that there is very little evidence of exchange between Mesopotamia and the highland regions; however, if influence there was, it would have been with Susa and Luristan as they were close neighbours. However, there is "clear indication of an active and widespread exchange network stretching the entire breadth of the Iranian plateau from Bactria through south-east and south-central Iran as far as Susa" [5].

Where did our particular type of axe originate? This author feels that it was in Bactria. There is an interesting bronze hammer in Paris [6] with an inscription of Shulgi, from Susa, T. Potts [7] says it is typologically Bactrian with lock-like curls on the butt and birds' heads rising from the top, and is surely an exotic item. A very similar hammer [8] of purer stylization, finer workmanship, and in silver with the tail plumage partially gilt is also said to be from North Afghanistan.

The understanding of the nature of a wild boar would be in keeping with a Western-Central Asian provenance where the beast thrived in the lands around the Oxus. The distinctive mark of oval shape between the shoulders is neither a solar emblem nor a tuft of hair; may we suggest that it could be a clan identification [9]? The boar's juxtaposition with a lion - the latter possibly expressing the victory of the ruler over the dark forces of nature - would be well suited to ceremony and prestige.

Unpublished.

1 Metropolitan Museum, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, James N. Spear and Schimmel Foundation, Inc. Gifts, 1982.5 (L: 15 cm): Pittman, H.: Art of the Bronze Age, Southeastern Iran, Western Central Asia and the Indus Valley. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 1984), p. 66 ff., fig. 36. Amiet, P.: L'âge des échanges inter-iraniens 3500-1700 avant J.-C. (Paris, 1986),

pp. 195 ff., 317 fig. 173. Potts, T.: Mesopotamia and the East. An Archaeological and Historical Study of Foreign Relations 3400-2000 BC. Oxford Committee for Archaeology Monograph 37 (Oxford, 1994), p. 170 ff., fig 27.

2 Misdescribed in the above example as a split tail: Pittman, H.: op. cit., p. 67.

3 British Museum 123268 (L: 17.8 cm, misdated 5th-4th century B.C.): Dalton, O.M.: The Treasure of the Oxus with other examples of early Oriental Metal-work (London, 1964), no. 193, pp. 47-49, pl. XXIV. Amiet, P.: op. cit., pp. 195, 317 fig. 172.

4 Christie's, New York, 15 December, 1994, lot 68 ill. (L: 15.2 cm): its condition after extensive cleaning from what must have been a lump of chloride renders comparison of details difficult; however the shape of the eye seems to be as with the New York and present example.

5 Potts, T.: op. cit., p. 172.

6 Louvre Museum Sb 5634 (N 883; L: 11 cm; H: 9.3 cm), the inscription reads "Shulgi, powerful hero, king of Ur, king of Sumer and Akkad". Shulgi was a king of the Third Dynasty of Ur, he reigned in Mesopotamia in the last century of the 3rd millennium B.C.: Amiet, P.: Elam (Auvers-sur-Oise, 1966), no. 176, p. 243.

7 Potts, T.: op. cit., p. 176.

8 In the author's collection and said to be from the same region as this ceremonial axe, a very strong new indication of their provenance and manufacture.

9 In China, jades from Hongshan (Shanghai region) carried clan marks from c. 3500-1800 B.C. and bronzes from Erligang (name of site and period) at Zhengzhou, Honan, from 1800 B.C. onwards. This does not necessarily suggest a connection.

https://www.georgeortiz.com/objects/near-east/014-bis-ceremonial-axe-sumer/

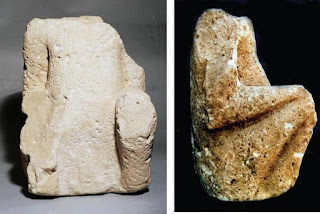

Ritual vase. Sumer.

Limestone

H: 6.2 cm. Diam: 6 cm

Allegedly from Ur

Proto-Sumerian

Djemdet Nasr period. c. 3000 B.C.

Condition: complete but with several cracks and three small pieces glued back in place on the chipped rim, and a hole behind the reclining heifer. A few stains on the surface.

A vessel decorated with a standing bull in low relief, his turned head in high relief; also in low relief a reclining young heifer and a sacred stable surmounted by emblematic poles [1]. The stable built of reeds with reinforced tubular uprights and horizontals. An Early Sumerian bowl in stone from Khafaje has a similar type of representation [2].

These form part of the same iconographic group as a magnificent gypsum trough from Warka decorated in low relief with a sacred stable and sheep, probably used for the temple flock [3]; their purpose is ritual, to invoke divine providence for the herd or to manifest gratitude to the god for past bounty [4] possibly dedicated to the god of vegetation Dumuzi, the "Real Son" legendary king of Uruk, called the Shepherd, who is later known as Tammuz [5].

1 A parallel for the stable and poles is a fragment of a large ritual alabaster vase of the Djemdet Nasr period in Paris, Louvre Museum AO 8842: Amiet, P.: L'Art Antique du Proche-Orient (Paris, 1977), no. 231, pp. 354, 442; for greater resemblance, see a cylinder seal in limestone from Khafaje, likewise of the Djemdet Nasr period, in the Baghdad Museum: Orthmann, W.: Der Alte Orient, PKG 14 (Berlin, 1975), no. 127b, p. 226 - here the surrounding herds are ascribed to Tammuz (?).

2 Baghdad, Iraq Museum: Orthmann, W.: op. cit., p. 183 pl. 71b.

3 London, British Museum WA 120 000: Frankfort, H.: The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient (Harmondsworth, 1970), p. 27 fig. 12.

4 Porada, E.: Problems of Style and Iconography in Early Sculptures of Mesopotamia and Iran, in: In Memoriam Otto J. Brendel (Mainz, 1976), p. 4.

5 Amiet, P.: op. cit., p. 566.

https://www.georgeortiz.com/objects/near-east/003-ritual-vase-sumer/

Three worshippers. Sumer.

Copper

H: 11.3 cm. Diam: 19.9 cm

Allegedly from Afghanistan

Bactrian?

Late 3rd-early 2nd millennium B.C.

Solid-cast upside down by the lost wax process, the molten metal being poured in from the underside.

Condition: reassembled from four large pieces and five small fragments. The whole very slightly bent out of shape, particularly noticeable for the right forearm of the central figure.

Missing: two branches from the tree and the four elements that are either branches or the arms of a support of which only stumps remain at the top, and a small, flat section of one of the crossbars of the ring.

The surface is rough, in appearance granular and with longitudinal parallel ridges, a thick crust of light bluish green to dark green, flaked in places to reveal a Burgundy-coloured reddish copper.

This cult group has no direct parallel. It represents three figures at worship, a stylized tree behind them. The central figure with long hair, two braids framing the face and beard, is dressed in a skirt, his waist girt by a wide belt with a large central knob; he may be a priest. The two attendants are smaller, naked and beardless, perhaps an indication of their lower rank.

The stylized tree - maybe a "tree of life" - shows three complete branches still in place with curious double knobs on two of them, possibly phallic in connotation. The four protuberances on the top may be remains of support elements for a bowl, a lamp,

or some offering.

The whole group is mounted on a metal ring with flat crossbars.

The ensemble may have had a comparable function to that of the stand bearer (cat. no. 16) and to the goat vessel support (cat. no. 30).

For the projections at the top of the stylized tree a comparison with those surmounting the head of the nude male figure from the Temple Oval at Khafaje [1] seems appropriate. For the crossbars of the ring, there is a rapport with our stand bearer (cat. no. 16), with what was in all likelihood the base of the bull stand in Washington [2], and the rectangular grating of the ibex in Baltimore [3].

There is a bearded kneeling copper figure of somewhat earlier date, said to have been found near Warka (ancient Ur) [4]. He is seated with his legs tucked up under him and wears a broad belt. He is rounder and less oval than the central figure of our group but related to the alabaster bust of a bearded figure from Uruk of same date in Baghdad [5], as are the two limestone statuettes probably from Uruk in Paris [6]. Also related are the composite figures of chlorite and limestone [7]. All these figures share a similar style of beard with shaven upper lip and oval lower edge.

The present group has affinities with other sculptures from the end of the 4th millennium B.C. down to objects found at Shahdad, dated mid to late 3rd millennium B.C., but also illustrates a particular characteristic which is the position of the three figures seated on their haunches, one knee up and the other leg tucked under. This posture is to be found mainly on seals from Iran, dated to the first half of the 3rd millennium B.C. [8]

This ensemble is reminiscent of material from Mesopotamia (though the gesture of adoration of the three worshippers with palms flat is non-Sumerian) and Southern Iran, but belongs to Central Asia [9].

1 Baghdad, Iraq Museum: Frankfort, H.: Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafajah, OIP 44 (Chicago, 1939), no. 181, pp. 76-77, pl. 98-101.

2 Arthur M. Sackler Gallery S. 87.0135.

3 Walters Art Gallery 54.2328: Vorys Canby, J.: The Ancient Neat East in The Walters Art Gallery (Baltimore, 1974), no. 40.

4 In the collection of Jonathan P. Rosen, New York; ascribed by E. Porada (A Male Figure in the Style of the Uruk Period, in: Mori, M. <ed.>: Near Eastern Studies Dedicated to H.I.H. Prince Takahito Mikasa on the Occasion of His Seventy-Fifth Birthday, Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan, vol. V <Wiesbaden, 1991>, p. 335 ff.) to the style of the Uruk period and probably Mesopotamian (offprint kindly relayed by Mr. Rosen).

5 Iraq Museum: Amiet, P.: L'art antique du Proche-Orient (Paris, 1977) no. 248, pp. 443, 357 ill.

6 Louvre Museum AO 5718/9: Amiet, P.: op. cit., no. 226, pp. 442, 354 ill.

7 E.g., Louvre Museum AO 21104: Amiet, P.: L'âge des échanges inter-iraniens, 3500-1700 av. J.-C. (Paris, 1986) pp. 200, 331 fig. 206. - One in the Fouroughi coll. Teheran: 7000 Jahre Kunst in Iran (Villa Hügel Essen, 1962), cat. no. 4, p. 45 ill.

8 Amiet, P.: L'âge des échanges inter-iraniens, p. 244 fig. 20,1+2, p. 245 fig. 20,6, p. 246 fig. 22,1; all ascribed to Susa II (= Late Uruk period).

9 Discoveries of recent years have shown that Bactria (Northern Afghanistan) was a major centre of ancient metalwork in the late 3rd and early 2nd millennia B.C. An extensive network of exchange connected this Central Asian culture with the various regions of Greater Iran as far west as Susa (this trade network is thoroughly discussed by P. Amiet, see footnote 8).

https://www.georgeortiz.com/objects/near-east/014-three-worshippers-sumer/

Stand bearer. Sumer.

Copper

H: 27.3 cm

Allegedly from South Iran

Mesopotamian?

Mid to late 3rd millennium B.C.?

Solid-cast by the lost wax process with some cold-working.

Condition: the figure bent towards the right and the rectangular grating on its right side greatly distorted upwards.

The patina a thick crust, green, azurite and hard reddish-green with deposits of yellowish to brownish earth, mostly flaked and chipped off to reveal a smooth undersurface, a "blurred" colour, dark brownish-red, aggressively abraded in many parts. The lower part of the sash, hanging from the belt, bent back. The circular ring surmounting the four-armed support slightly distorted.

This statue has affinities with a group of arsenical copper figures [1] (all vessel supports) to which have been related the Bull-man (cat. no. 15) and his pair. It may be compared for details such as its ears and the shape of its nose with the nude male statue in New York [2], and though the general almond shape of the eyes bears resemblance, on the New York figure they are solid with a central slit, whereas here they are hollowed out to receive an inlay. However, they are basically dissimilar. Particularly noticeable on the present figure are the high ridges for the eyebrows and a similarly exaggerated accentuation of the collar-bones. He wears a skirtlet held up by a wide belt, a thick sash hanging down in front, and thus differs greatly from all the other figures that are naked. Because of his dress and cap with raised visor, he is ascribed to a slightly later period, though the dating of the other copper figures and the alabaster bull-men varies among scholars between Early Dynastic I and II [3] .

Its style may derive from Southern Mesopotamia or from Southwestern Iran [4]. All these statues appear to belong to a common tradition and served a somewhat similar purpose.

This figure probably fulfilled the function of a temple attendant holding up a bowl of incense, a lamp or some other offering.

1 Baghdad, Iraq Museum; Chicago, Oriental Institute Museum A 9270, A 9271: Frankfort, H.: Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafajah, OIP 44 (Chicago, 1939), nos. 181, 182, 183, pp. 76-77 pl. 98-103.

2 Metropolitan Museum 55.142: Muscarella, O.W.: Bronze and Iron. Ancient Near Eastern Artifacts in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 1988), no. 464, pp. 323-327.

3 Muscarella, O. W.: op. cit., p. 326, for the different points

of view.

4 O.W. Muscarella replied to our query on 5 June 1995 saying that one cannot go beyond this which is "an 'intelligent' guess, nothing more".

https://www.georgeortiz.com/objects/near-east/016-stand-bearer-sumer/

Goat vessel stand. Ancient Anatolia

Bronze

H: 14.85 cm. L: 16 cm

Provenance: no indication

Eastern Anatolian? (possibly region of Armenia)

Late 3rd-early 2nd millennium B.C.?

Cast by the lost wax process, probably with a central core to economize metal, and cold-worked.

Condition: missing the offering stand of which the shaft emerged from the middle of the back - unfortunately removed in modern times by a previous owner and its emplacement smoothed down to the line of the rest of the back; also missing the lower part of the right hind leg, the hoof of the front left leg and the rectangular openwork grating to which all four hooves would have been affixed - a 2.2 cm fragment of this still attached to the front right hoof. A deep gash across his belly. The eyes once inlaid.

Surface smooth, reddish-brown metal, originally covered with dark green and red patina, mostly cleaned off. Traces of brown earth deposits in the recesses.

The goat's [1] legs were originally affixed to a rectangular grating of the type under the stand bearer (cat. no. 16), somewhat comparable to the one that joins the legs of a long-horned ibex in Baltimore [2]. A bull [3], also on a grating of which only pieces remain attached to the hooves, retains its complete support, a cylindrical, slightly tapering shaft from which project four arms surmounted by a ring.

The lack of any excavation data for these pieces and of any scientifically ascribed comparative material renders their dating and attribution hazardous.

The writer thinks that the zoomorphic vessel support in New York [4] mounted on a foot that bears some affinity with those under figures from the Temple Oval at Khafaje [5] is, as described, probably of an earlier date (second quarter of the 3rd millennium B.C.) and would tend to date this figure end of the 3rd or beginning of the 2nd millennium B.C.

As with the Bull-man (cat. no. 15) and the stand bearer (cat. no. 16), this goat was probably also a stand for cult use in a temple.

1 Mrs. Juliet Clutton-Brock, D.Sc., FSA, of the Mammal Section of the Natural History Museum London kindly informs us, after viewing photographs, which is always difficult, that he "... looks most like a male domestic goat ... evident from the beard, and the dropped ears indicate domestication. .... The 'ruffs' around the legs and the nose could be meant to show that the goat has a long shaggy coat."

2 Walters Art Gallery 54.2328: Vorys Canby, J.: The Ancient Near East in The Walters Art Gallery (Baltimore, 1974), no. 40.

3 Washington, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery S.87.0135.

4 Metropolitan Museum 1974.190: Muscarella, O.W.: Bronze and Iron. Ancient Near Eastern Artifacts in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 1988), no. 467, pp. 333-336.

5 Baghdad, Iraq Museum; Chicago, Oriental Institute Museum A 9270, A 9271: Frankfort, H.: Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafajah, OIP 44 (Chicago, 1939), nos. 181-183, pp. 76-77 pl. 98-103

https://www.georgeortiz.com/objects/near-east/030-goat-vessel-stand-ancient-anatolia/

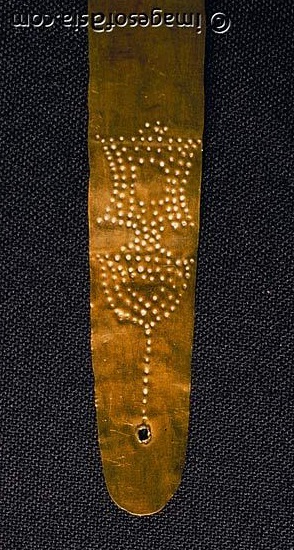

Hammer decorated with heads of two birds and feathers

A work inscribed with the name of a Mesopotamian king

During this period, Susa and Elam were returned to Mesopotamia. Shulgi took control of Mesopotamia and conquered Susa, thus putting an end to the attempts of the Elamite sovereign Puzur-Inshushinak to achieve autonomy.

Epigraphic figurines and foundation tablets in the name of Shulgi (Louvre Museum, Sb 2879 and Sb 2880) record the king's building of the temples of Ninhursag and Inshushinak on the acropolis at Susa.

The inscription on this bronze hammer dedicated to him is in Sumerian, once more the official language in the Neo-Sumerian period, and uses the official title adopted by Shulgi's predecessor: "King of Sumer and Akkad."

A ceremonial weapon in the Iranian tradition

These bronze hammers and axes featuring animal motifs were often ceremonial weapons presented by Elamite sovereigns to their dignitaries. An illustration of this custom can be seen on the seal of Kuk-Simut, an official under Idadu II, an Elamite prince in the early years of the 2nd millennium BC (Louvre Museum, Sb 2294). This votive weapon was thus preserved for eternity in its owner's grave.

- Marteau orné de deux têtes et d'un plumage d'oiseau

- BronzeH. 12. 3 cm; L. 11 cm

- Fouilles R. de Mecquenem, tell de l'AcropoleInscription du roi Shulgi "héros puissant, roi d'Ur, roi de Sumer et d'Akkad"Sb 5634

Bibliography

Amiet Pierre, Élam, Auvers-sur-Oise, Archée, 1966, p. 243, n 176.La Cité royale de Suse, Exposition, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17 novembre 1992-7 mars 1993, Paris, Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994, p. 92, n 56.

https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/hammer-decorated-heads-two-birds-and-feathers

Viral content

Viral content The good doctor

The good doctor

This might hurt

This might hurt  Have I got moos for you

Have I got moos for you

"Even though Zardozi is believed to have its origin in Persia (Zar in Persian means gold and Dozi is embroidery), the use of gold and silver thread work, in fact, goes back to ancient India, finding mention in Vedic literature and visually evident in the figures that adorn the walls of the caves of Ajanta...While arri looks like fine chain stitch, zardozi, on the other hand, has finer designs as while the hand above the cloth works the needle the hand below ties each stitch making zardozi products not only beautiful but also durable."

"Even though Zardozi is believed to have its origin in Persia (Zar in Persian means gold and Dozi is embroidery), the use of gold and silver thread work, in fact, goes back to ancient India, finding mention in Vedic literature and visually evident in the figures that adorn the walls of the caves of Ajanta...While arri looks like fine chain stitch, zardozi, on the other hand, has finer designs as while the hand above the cloth works the needle the hand below ties each stitch making zardozi products not only beautiful but also durable."