Mistranslation of यज्ञः as 'sacrifice' leads to many distortions in understanding the true significance of the process of worship. The worship is a celebration of wealth created or accumulated through the यज्ञः process. नैघण्टुक clarifies the semantics unambiguously.

मेधा= धन Naigh. ii , 10. This explanation in नैघण्टुक, commented on by यास्क is central to understanding the semantics of यज् . In English translations of this word as 'sacrifice' is likely to be misleading. The correct rendering of yaj is to worship. Thus, यजनम् yajanam or यज्ञः yajñḥ should be correctly rendered as 'worship'. When मेधा mēdhā is used as a synonym of यज्ञः yajñḥ, the rebus rendering of मेधा= धन is inferred. धन n. the prize of a contest or the contest itself (lit. a running match , race , or the thing raced for ; हित्/अं धा*नम् , a proposed prize or contest ; धनं- √जि , to win the prize or the fight) RV.any valued object , (esp.) wealth , riches , (movable) property , money , treasure , gift RV. &c; = गो-धन Hariv. 3886

यज् cl.1 P. A1. ( Dha1tup. xxiii , 33) य्/अजति °ते (1. sg. यजसे RV. viii , 25 , 1 ; Ved. Impv. य्/अक्षि or °ष्व ; pf. इयाज MBh. ; ईज्/ए RV. ; येज्/ए [?] AV. cf. Ka1s3. on Pa1n2. 6-4 ,120 ; Ved. aor. अयाक्षीत् or अयाट् ; अयष्ट ;

Subj. यक्षत् , यक्षति , °ते ; 3. sg. अयक्षत A1s3vGr2. ; Prec. इज्यात् Pa1n2. 3-4 , 104 ; यक्षीय MaitrS. ; fut. यष्टा Br. ; यक्ष्यति,°य्/अते RV. &c ; inf. य्/अष्टुम् , ईजितुम् MBh. ; Ved. °टवे ; य्/अजध्यै or यज्/अध्यै ; p.p. इष्ट ind.p. इष्ट्व्/आ AV. ; इष्ट्वीनम् Pa1n2. 7-1 , 48 ; -इज्य Gr. ; य्/आजम् AV. ) , to worship , adore , honour (esp. with sacrifice or oblations) ;

to consecrate , hallow , offer (with acc. , rarely dat. loc. or प्रति , of the deity or person to whom ; dat. of the person for whom , or the thing for which ; and instr. of the means by which the sacrifice is performed ; in older language generally P. of अग्नि or any other mediator , and A1. of one who makes an offering on his own account cf. य्/अज-मान ; later properly P. when used with reference to the officiating priest , and A1. when referring to the institutor of the sacrifice) RV. &c ;

(A1.) to sacrifice with a view to (acc.) RV. ;

to invite to sacrifice by the याज्या verses S3Br. S3a1n3khS3r. : Pass. इज्यते (p. Ved. इज्यमान or यज्यमान Pat. on Pa1n2. 6-1 , 108 ; ep. also pr. p. इज्यत्) , to be sacrificed or worshipped MBh. Ka1v. &c : Caus. याज्/अयति (ep. also °ते ; aor. अयीयजत्) , to assist any one (acc.) as a priest at a sacrifice (instr.) TS. Br. ;

to cause any one (acc.) to sacrifice anything (acc.) or by means of any one (instr.) MBh. R. : Desid. य्/इयक्षति , °ते (cf. /इयक्षति) , to desire to sacrifice or worship MBh. R. : Intens. यायज्यते , यायजीति , यायष्टि Pa1n2. 7-4 , 83 Sch. [cf. Zd. yaz ]

मेधः mēdhḥ मेधः 1 A sacrifice, as in नरमेध, अश्वमेध, एकविंशतिमेधान्ते Mb.14.29.18. (com. मेधो युद्धयज्ञः । 'यज्ञो वै मेधः'इति श्रुतेः ।). -2 A sacrificial animal or victim. -3 An offering, oblation. -4 Ved. The juice of meat, broth. -5 Ved. Sap, pith, essence. -Comp. -जः an epithet of Viṣṇu.

मेधा mēdhā मेधा [मेध्-अञ्] (changed to मेधस् in Bah. comp. when preceded by सु, दुस् and the negative particle अ) 1 Retentive faculty, retentiveness (of memory); धी- र्धारणावती मेधा Ak. -2 Intellect, intelligence in general; यत् सप्तान्नानि मेधया तपसाजनयत् पिता Bṛi. Up.1.5.1; Bg. 1.34; आयुष्मन्तं सुतं सूते यशोमेधासमन्वितम् Ms.3.263; Y. 3.173. -3 A form of Sarasvathī. -4 A sacrifice. -5 Strength, power (Ved.). -Comp. -अतिथिः N. of a learned commentator on Manusmṛiti. -जननम् N. of a rite for producing mental and bodily strength. -जित् m. an epithet of Kātyāyana. -रुद्रः an epithet of Kālidāsa.

यजनम् yajanam यजनम् [यज्-ल्युट्] 1 The act of sacrificing. -2 A sacrifice; देवयजनसंभवे देवि सीते U.4. -3 A place of sacri- fice; उत्पत्तिर्देवयजनाद् ब्रह्मवादी नृपः पिता ।.

यजमान yajamāna यजमान a. [यज्-शानच्] Sacrificing, worshipping. -नः 1 A person who performs a regular sacrifice and pays its expenses; जगाम यज्वा यजमानलोकम् R.18.12; ततः प्रविशति कुशानादाय यजमानशिष्यः Ś. -2 A person who employs a priest or priests to sacrifice for him. -3 (Hence) A host, patron, rich man. -4 The head of a family. -5 The head of a tribe. -Comp. -शिष्यः the pupil of a sacrificing Brāhmaṇa (of one who himself per- forms a sacrifice); Ś.4.

यजमानकः yajamānakḥ यजमानकः = यजमान.

यजस् yajas यजस् n. Ved. 1 Worship; इन्द्राग्नी यजसा गिरा Rv. 8.4.4. -2 A sacrifice.

यजाक yajāka यजाक a. 1 Liberal. -2 Worshipping.

यजिः yajiḥ यजिः [यज्-इन्] 1 A sacrificer. -2 The act of sacrificing. -3 A sacrifice; दानमध्ययनं यजिः Ms.1.79.

यजिन् yajin यजिन् a. 1 A worshipper, sacrificer. -2 Honouring, adoring.

यजुस् yajus यजुस् n. [यज्-उसि] 1 A sacrificial prayer or formula; तां कामयानां भगवानुवाह यजुषां पतिः Bhāg.4.1.6. -2 A text of the Yajurveda, or the body of sacred mantras in prose muttered at sacrifices; वृत्तगीतिवर्जितत्वेन प्रश्लिष्टपठिता मन्त्रा यजूंषि Sāyaṇa; cf. मन्त्र. -3 N. of the Yajurveda. -4 Ved. Worship, oblation. -Comp. -उदरः Ved. an epithet of Brahman. -पतिः N. of Viṣṇu. -विद् a. knowing the sacrificial formulæ. -वेदः the second of the three (or four, including the Atharvaveda) principal Vedas, which is a collection of sacred texts in prose relating to sacrifices; it has two chief branches or recensions :-the तैत्तिरीय or कृष्ण- यजुर्वेद and बाजसनेयी or शुक्लयजुर्वेद.

यज्ञः yajñḥ यज्ञः [यज्-भावे न] 1 A sacrifice, sacrificial rite; any offering or oblation; यज्ञेन यज्ञमयजन्त देवाः; तस्माद्यज्ञात् सर्वहुतः &c.; यज्ञाद् भवति पर्जन्यो यज्ञः कर्मसमुद्भवः Bg.3.14. -2 An act of worship, any pious or devotional act. (Every householder, but particularly a Brāhmaṇa, has to perform five such devotional acts every day; their names are :-भूतयज्ञ, मनुष्ययज्ञ, पितृयज्ञ, देवयज्ञ, and ब्रह्मयज्ञ, which are collectively called the five 'great sacrifices'; see महायज्ञ, and the five words separately.) -3 N. of Agni. -4 Of Viṣṇu; ऋषयो यैः पराभाव्य यज्ञघ्नान् यज्ञमीजिरे Bhāg.3.22.3. -Comp. -अंशः a share of sacrifice ˚भुज् m. a deity, god; निबोध यज्ञांशभुजामिदानीम् Ku.3.14. -अ(आ)गारः, -रम् a sacrificial hall. -अङ्गम् 1 a part of a sacrifice. -2 any sacrificial requisite, a means of a sacrifice; यज्ञाङ्गयोनित्वमवेक्ष्य यस्य Ku.1.17. (-गः) 1 the glomerous figtree (उदुम्बर). -2 the Khadira tree. -3 N. of Viṣṇu. -4 the black-spotted antelope. -अन्तः 1 the completion of a sacrifice. -2 an ablution at the end of a sacrifice for purification. -3 a supplementary sacri- fice. ˚कृत् m. N. of Viṣṇu. -अरिः an epithet of Śiva. -अर्ह a. 1 deserving sacrifice. -2 fit for a sacrifice. (-m. dual) an epithet of the Aśvins. -अवयवः N. of Viṣṇu. -अशनः a god. -आत्मन् m. -ईश्वरः N. of Viṣṇu. -आयुधम् an implement of a sacrifice. These are said to be ten in number; स्पयश्च कपालानि च अग्निहोत्रहवणी च शूर्पं च कृष्णाजिनं च शम्या चोलूखलं च मुसलं च दृषच्चोपला एतानि वै दश यज्ञायुधानीति (quoted in ŚB. on MS.4.7.) -ईशः 1 N. of Viṣṇu. -2 of the sun. -इष्टम् a kind of grass (दीर्घरोहिततृण). -उपकरणम् any utensil or implement necessary for a sacrifice. -उपवीतम् the sacred thread worn by members of the first three classes (and now even of other lower castes) over the left shoulder and under the right arm; see Ms.2.63; वामांसावलम्बिना यज्ञोपवीतेनोद्भासमानः K.; कौशं सूत्रं त्रिस्त्रिवृतं यज्ञोपवीतम् ...... Baudhāyana; (originally यज्ञोपवीत was the ceremony of investiture with the sacred thread). -उपासक a. performing sacrifices. -कर्मन् a. engaged in a sacrifice. (-n.) a sacrificial rite. -कल्प a. of the nature of a sacrifice or sacrificial offering. -कालः the last lunar day of every fortnight (full-moon and new- moon). -कीलकः a post to which the sacrificial victim is fastened. -कुण्डम् a hole in the ground made for receiving the sacrificial fire. -कृत् a. performing a sacrifice. (-m.) 1 N. of Viṣṇu. -2 a priest conducting a sacrifice. -क्रतुः 1 a sacrificial rite; Ait. Br.7.15. -2 a complete rite or chief ceremony. -3 an epithet of Viṣṇu; ईजे च भगवन्तं यज्ञक्रतुरूपम् Bhāg.5.7.5. -क्रिया a sacrificial rite. -गम्य a. accessible by sacrifice (Viṣṇu). -गुह्यः N. of Kṛiṣṇa. -घ्नः a demon who interrupts a sacrifice. -त्रातृ m. N. of Viṣṇu. -दक्षिणा a sacrificial gift, the fee given to the priests who per- form a sacrifice. -दीक्षा 1 admission or initiation to a sacrificial rite. -2 performance of a sacrifice; (जननम्) तृतीयं यज्ञदीक्षायां द्विजस्य श्रुतिचोदनात् Ms.2.169. -द्रव्यम् anything (e. g. a vessel) used for a sacrifice. -द्रुह् m. an evil spirit, a demon. -धीर a. conversant with wor- ship or sacrifice. -पतिः 1 one who institutes a sacrifice. See यजमान. -2 N. of Viṣṇu. -पत्नी the wife of the institutor of a sacrifice. -पशुः 1 an animal for sacrifice, a sacrificial victim. -2 a horse. -पात्रम्, -भाण्डम् a sacrificial vessel. -पुंस्, -पुमान् m. N. of Viṣṇu. -पुरुषः, -फलदः epithets of Viṣṇu. -बाहुः N. of Agni. -भागः 1 a portion of a sacrifice, a share in the sacrificial offerings. -2 a god, deity. ˚ईश्वरः N. of Indra. ˚भुज् m. a god, deity. -भावनः N. of Viṣṇu. -भावित a. honoured with sacrifice; इष्टान् भोगान् हि वो देवा दास्यन्ते यज्ञभाविताः Bg.3.12. -भुज् m. a god. -भूमिः f. a place for sacri- fice, a sacrificial ground. -भूषणः white darbha grass. -भृत् m. an epithet of Viṣṇu. -भोक्तृ m. an epithet of Viṣṇu or Kṛiṣṇa. -महीत्सवः a great sacrificial care- mony. -योगः the Udumbara tree. -रसः, -रेतस् n. Soma. -वराहः Viṣṇu in his boar incarnation. -वल्लिः, -ल्ली f. the Soma plant. -वाटः a place prepared and enclosed for a sacrifice. -वाह a. conducting a sacrifice. -वाहनः 1 an epithet of Viṣṇu. -2 a Brahmaṇa. -3 N. of Śiva. -वीर्यः N. of Viṣṇu. -वृक्षः the fig-tree. -वेदिः, -दी f. the sacrificial altar. -शरणम् a sacrificial shed or hall, a temporary structure under which a sacri- fice is performed ; M.5. -शाला a sacrificial hall. -शिष्टम्, -शेषः -षम् the remains of a sacrifice; यज्ञशिष्टाशिनः सन्तो मुच्यन्ते सर्वकिल्बिषैः Bg.3.13; यज्ञशेषं तथामृतम् Ms.3.285. -शील a. zealously performing sacrifice; यद् धनं यज्ञशीलानां देवस्वं तद् विदुर्बुधाः Ms.11.2. -श्रेष्ठा the Soma plant. -संस्तरः the act of setting up the sacrificial bricks; यज्ञ- संस्तरविद्भिश्च Mb.1.7.42. -सदस् n. a number of people at a sarifice. -संभारः materials necessary for a sacri- fice. -सारः an epithet of Viṣṇu. -सिद्धिः f. the comple- tion of a sacrifice. -सूत्रम् see यज्ञोपवीत; अन्यः कृष्णाजिन- मदाद् यज्ञसूत्रं तथापरः Rām.1.4.21. -सेनः an epithet of king Drupada. -स्थाणुः a sacrificial post. -हन् m., -हनः epithets of Śiva. -हुत् m. a sacrificial priest.

Gold f

Gold f

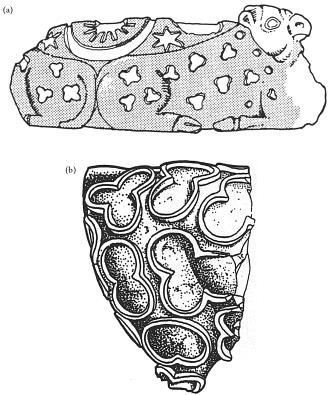

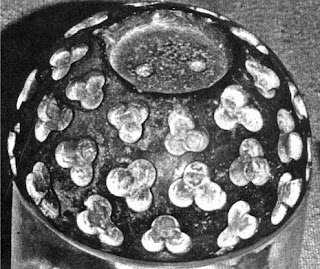

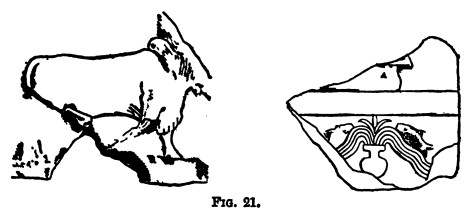

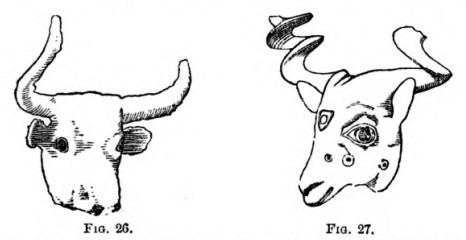

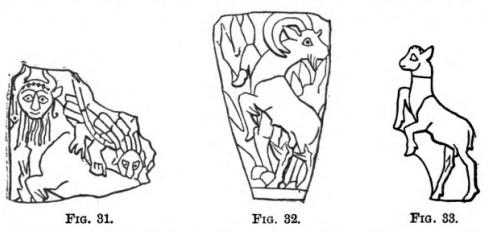

Crete. Cow-head rhython with trefoil decor.

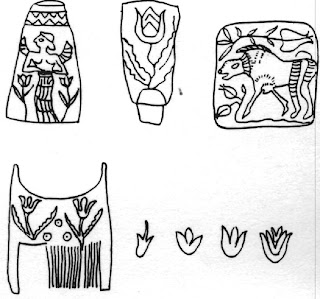

Crete. Cow-head rhython with trefoil decor. Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit

Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit

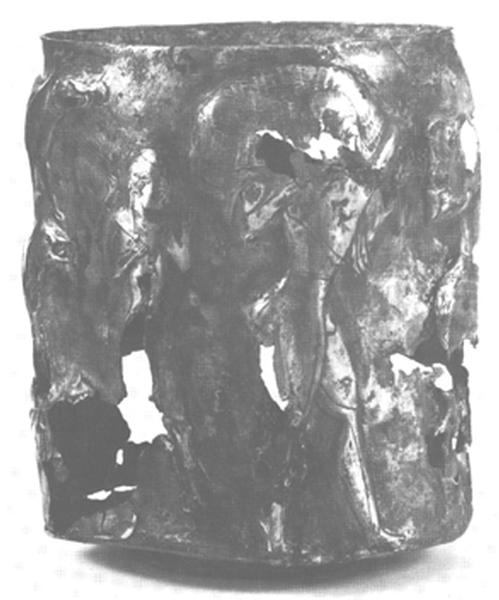

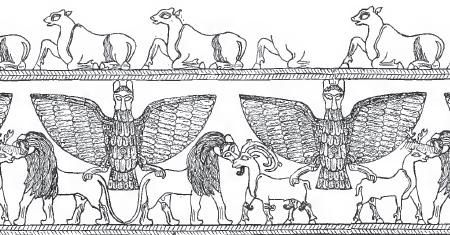

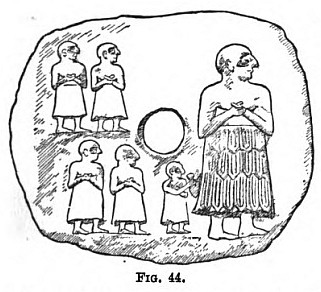

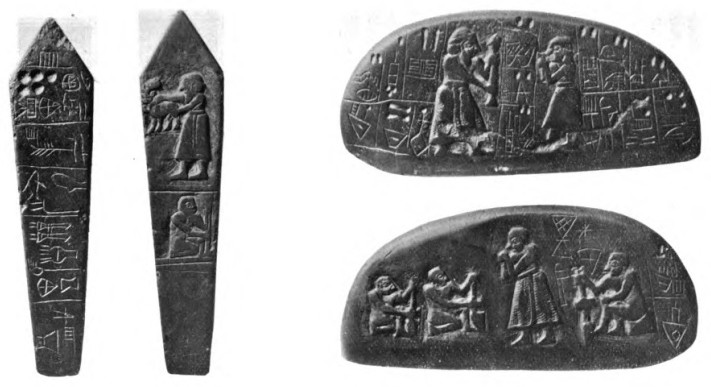

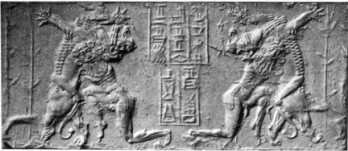

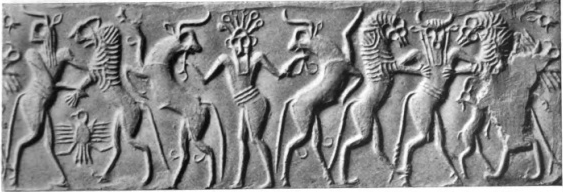

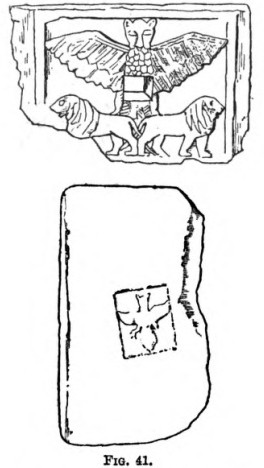

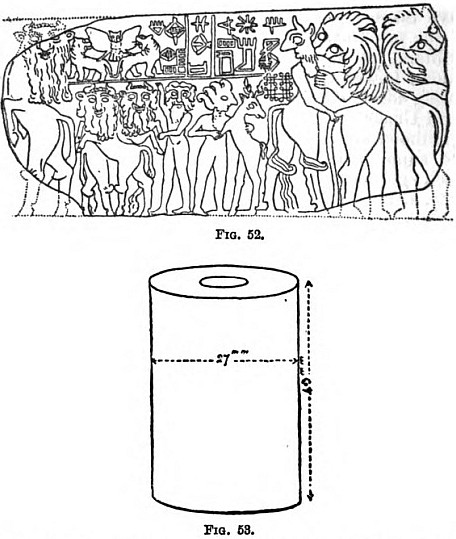

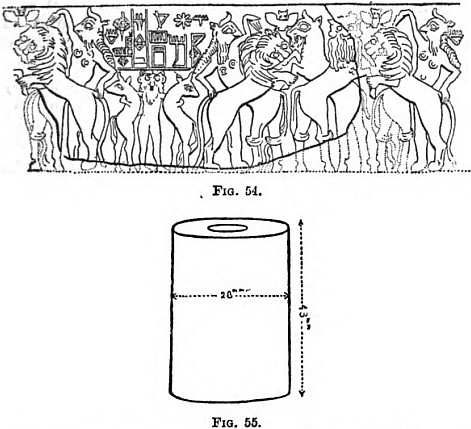

Hieroglyphs of Indus Script on Entemena silver vase. pota 'youngbull' rebus: pota 'molten metal casting'; mlekh, mreka 'goat' rebus:milakkhu 'copper'; arye 'lion' rebus: ara 'brass'; śyēná (anzu) >

Hieroglyphs of Indus Script on Entemena silver vase. pota 'youngbull' rebus: pota 'molten metal casting'; mlekh, mreka 'goat' rebus:milakkhu 'copper'; arye 'lion' rebus: ara 'brass'; śyēná (anzu) >

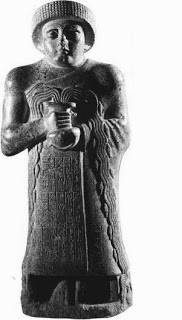

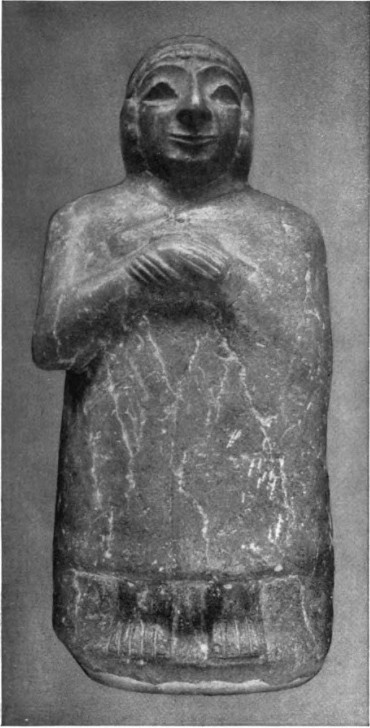

A diorite statue of Gudea holding an vase with overflowing water.

A diorite statue of Gudea holding an vase with overflowing water.

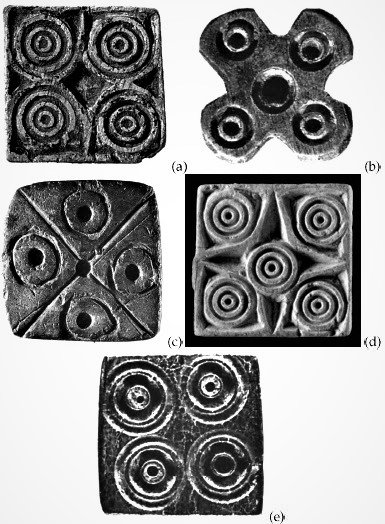

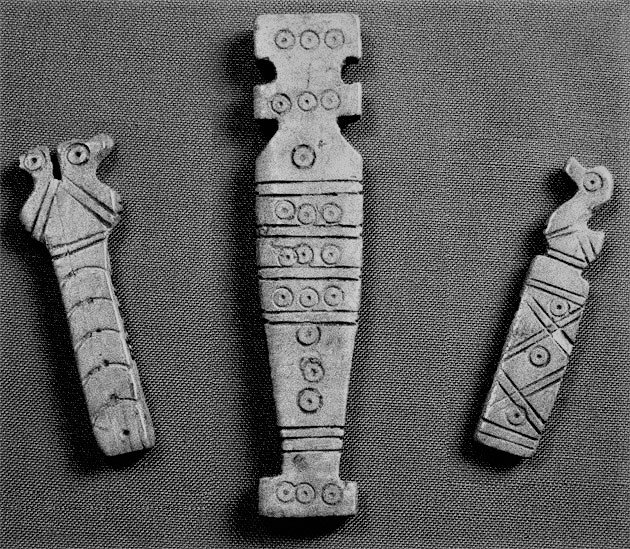

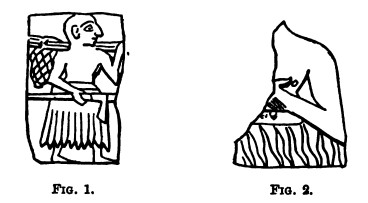

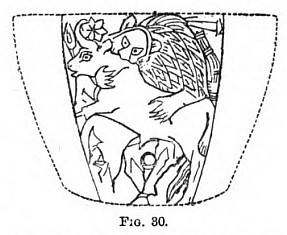

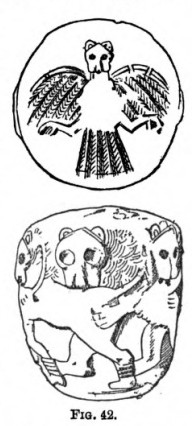

karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron' PLUS ujjain symbol (see decipherment of Indus Script hypertext)

karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron' PLUS ujjain symbol (see decipherment of Indus Script hypertext)

A coin of

A coin of

One of a pair of royal earrings in gold (front and back view).

One of a pair of royal earrings in gold (front and back view). Srivatsa atop Sanchi torana. The hypertext is a pair of fish-fins in orthographic style. The Meluhha rebus reading of the plaint text is: dul aya

Srivatsa atop Sanchi torana. The hypertext is a pair of fish-fins in orthographic style. The Meluhha rebus reading of the plaint text is: dul aya

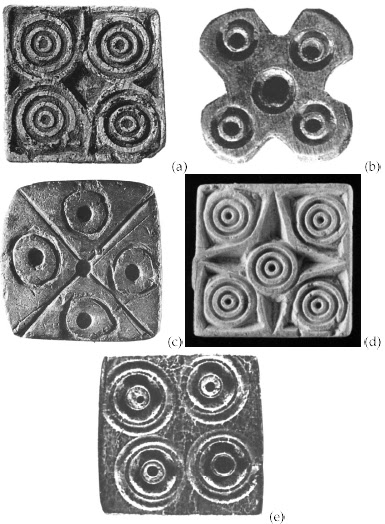

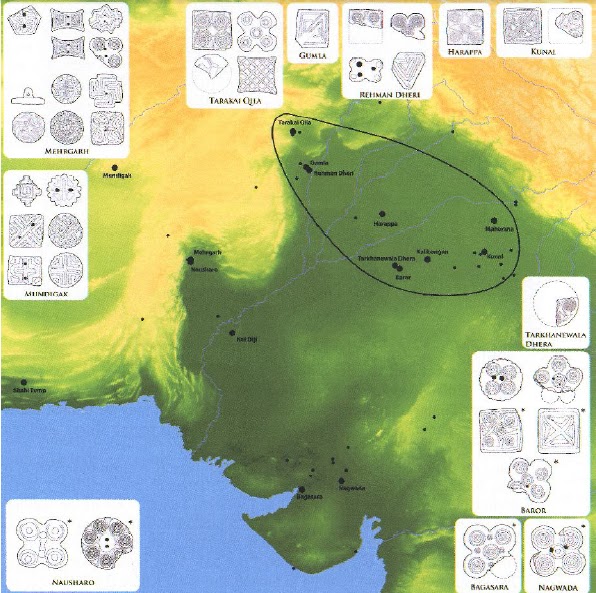

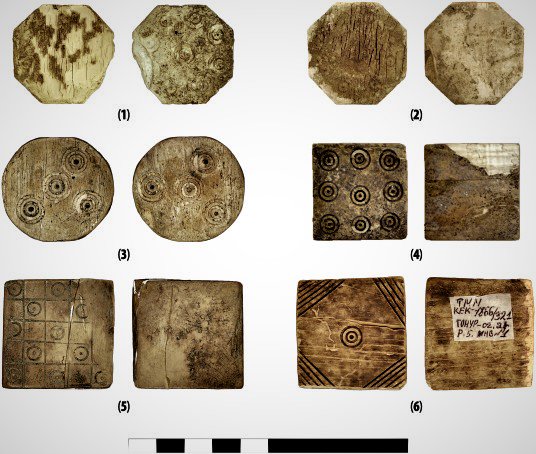

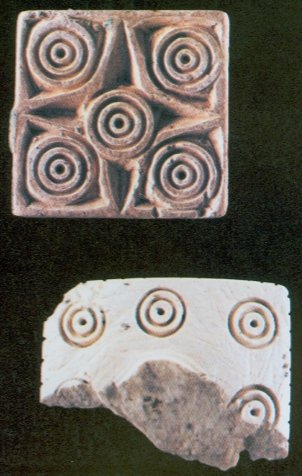

Indian and Persian turners at work.

Indian and Persian turners at work.

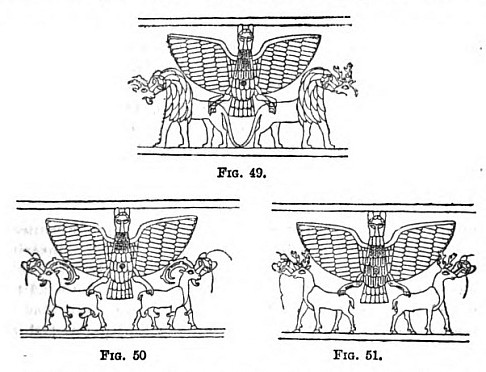

Winged aurochs, 'unicorn'.

Winged aurochs, 'unicorn'.

The degree of disorder in different sequences. Indus inscriptions fall near writing systems, between DNA (top) and computer code (bottom) (Credit: Rao, Probabilistic Analysis of an Ancient Undeciphered Script, Computer, April 2010)...Other methods using

The degree of disorder in different sequences. Indus inscriptions fall near writing systems, between DNA (top) and computer code (bottom) (Credit: Rao, Probabilistic Analysis of an Ancient Undeciphered Script, Computer, April 2010)...Other methods using

Third Court.

Third Court. Second Court.

Second Court.

Bull capital. Apadana palace. Susa.

Bull capital. Apadana palace. Susa.

Relief of Winged unicorn, Apadana, Susa.

Relief of Winged unicorn, Apadana, Susa.  Lion-shaped weight.

Lion-shaped weight. Bracelet ornated with lion-heads.

Bracelet ornated with lion-heads.

Reading of the inscription text as recorded in ASI 1977 Concordance List (Mahadevan)

Reading of the inscription text as recorded in ASI 1977 Concordance List (Mahadevan)

Hampi

Hampi  सुभाष काक. Author, scientist. Quantum information, AI, history of science. https://subhask.okstate.edu/sites/default/files/HistoryVedaArt_SubhashKak.pdf

सुभाष काक. Author, scientist. Quantum information, AI, history of science. https://subhask.okstate.edu/sites/default/files/HistoryVedaArt_SubhashKak.pdf