This is an addendum to:

Discovery of a Rosetta stone for अवि 'golden fleece', a Rgveda Potr̥, 'purifier priest' pōtadāra, পোদ্দার pōddāra 'assayer of metals' https://tinyurl.com/rcurjut

Bactrian silver cup narrative

खरडा kharaḍā 'A leopard' Rebus: karaḍā 'hard metal alloy'

miṇḍāl 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram (G.) rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron'

pōladu 'black drongo bird' rebus: पोलाद [ pōlāda] n (or P) Steel.

āhan gar, 'blacksmith', maker of asaṇi, vajrāśani 'Indra's thunderbolt' signified by श्येन 'm. a hawk , falcon , eagle , any bird of prey (esp. the eagle that brings down सोम to man)' RV. &c. It is veneration of the thunderbolt maker, blacksmith, āhan gar -- an expression derived from श्येन 'hawk' 1) attested in R̥gveda. .श्येन is name of a ऋषि (having the patr. आग्नेय and author of RV. x , 188; and 2) double eagles celebrated in Rāmāyaṇa: सम्-पाति m. N. of a fabulous bird (the eldest son of अरुण or गरुड and brother of जटायु) MBh. R. &c and जटायु m. N. of the king of vultures (son of अरुण and श्येनी MBh. ; son of गरुड R. ; younger brother of सम्पाति ; promising his aid to राम , out of regard for his father दश-रथ , but defeated and mortally wounded by रावण on attempting to rescue सीता) MBh. i , 2634 ; iii , 16043ff. and 16242ff R. i , iii f.

kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter'

baḍhia 'a castrated boar, a hog'(Santali) বরাহ barāha 'boar' Rebus: baḍhi 'worker in wood and iron' (Santali) bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) vāḍhī, 'one who helps a merchant (Hemacandra Desinamamamala).

vaḍraṅgi, vaḍlaṅgi, vaḍlavāḍu or వడ్లబత్తుడు vaḍrangi. [Tel.] n. A carpenter. వడ్రంగము, వడ్లపని, వడ్రము or వడ్లంగితనము vaḍrangamu. n. The trade of a carpenter. వడ్లవానివృత్తి. వడ్రంగిపని . వడ్రంగిపిట్ట or వడ్లంగిపిట్ట vaḍrangi-piṭṭa. n. A woodpecker. దార్వాఘాటము . వడ్లకంకణము vaḍla-kankaṇamu. n. A curlew. ఉల్లంకులలో భేదము . వడ్లత or వడ్లది vaḍlata. n. A woman of the carpenter caste.

See:

Eagle, श्येन sēṇa, کار کنده kār-kunda, آهن ګر āhan gar, 'blacksmith' are Indus Script metalwork wealth मेधा 'yajña, धन' hypertexts https://tinyurl.com/y8qnj9gu

Hammer decorated with heads of two birds and feathers

- Marteau orné de deux têtes et d'un plumage d'oiseau

- BronzeH. 12. 3 cm; L. 11 cm

- Fouilles R. de Mecquenem, tell de l'AcropoleInscription du roi Shulgi "héros puissant, roi d'Ur, roi de Sumer et d'Akkad"Sb 5634

- This votive bronze weapon is characteristic of Iranian metalwork, of which many examples have been found at the Susa site. Decorated with birds' heads and feathers, this hammer carries an inscription in Sumerian referring to King Shulgi: "Powerful hero, king of Ur, king of Sumer and Akkad."

A work inscribed with the name of a Mesopotamian king

Shulgi, second king of the 3rd Ur Dynasty, is one of the sovereigns who marked the Neo-Sumerian period, half of which was covered by his long forty-eight-year reign.

During this period, Susa and Elam were returned to Mesopotamia. Shulgi took control of Mesopotamia and conquered Susa, thus putting an end to the attempts of the Elamite sovereign Puzur-Inshushinak to achieve autonomy.

Epigraphic figurines and foundation tablets in the name of Shulgi (Louvre Museum, Sb 2879 and Sb 2880) record the king's building of the temples of Ninhursag and Inshushinak on the acropolis at Susa.

The inscription on this bronze hammer dedicated to him is in Sumerian, once more the official language in the Neo-Sumerian period, and uses the official title adopted by Shulgi's predecessor: "King of Sumer and Akkad."A ceremonial weapon in the Iranian tradition

This ceremonial bronze hammer is decorated with the heads of two birds on either side of the hammer collar and curled plumage on the heel. This model has not been found in Mesopotamia, but is well documented in Luristan. A similar example (Louvre Museum, AO 24794) from this region dates from the early years of the 2nd millennium BC. Though animal motifs are a very ancient form of decoration in Iran, it was in the late 3rd and the 2nd millenniums BC that Iranian metalworkers excelled in this type of weapon, often decorated with animals.

These bronze hammers and axes featuring animal motifs were often ceremonial weapons presented by Elamite sovereigns to their dignitaries. An illustration of this custom can be seen on the seal of Kuk-Simut, an official under Idadu II, an Elamite prince in the early years of the 2nd millennium BC (Louvre Museum, Sb 2294). This votive weapon was thus preserved for eternity in its owner's grave.Bibliography

Amiet Pierre, Élam, Auvers-sur-Oise, Archée, 1966, p. 243, n 176.

La Cité royale de Suse, Exposition, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17 novembre 1992-7 mars 1993, Paris, Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994, p. 92, n 56.

A Magnificent and Highly Important Gold and Silver Bactrian Ceremonial Axe

Gold sheet and silver, Late 3rd/early 2nd millennium B.C.E.L. 12.68 cm.

A Magnificent and Highly Important Gold and Silver Bactrian Ceremonial Axe

Gold sheet and silver, Late 3rd/early 2nd millennium B.C.E.L. 12.68 cm.

The whole cast by the lost wax process. The boar covered with a sheet of gold annealed and hammered on, some 3/10-6/10 mm in thickness, almost all the joins covered up with silver. At the base of the mane between the shoulders an oval motif with irregular indents. The lion and the boar hammered, elaborately chased and polished. A shaft opening - 22 holes around its edge laced with gold wire some 7/10-8/10 mm in diameter - centred under the lion's shoulder; between these a hole (diam: some 6.5 mm) front and back for insertion of a dowel to hold the shaft in place, both now missing.

Condition: a flattening blow to the boar's backside where the tail curled out and another to the hair between the front of his ears, his spine worn with traces of slight hatching still visible, a slight flattening and wear to his left tusk and lower left hind leg. A flattening and wear to the left side of the lion's face, ear, cheek, eye, nose and jaw and a flattening blow to the whole right forepaw and paw. Nicks to the lion's tail. The surface with traces of silver chloride under the lion's stomach and around the shaft opening.

The closest parallel stylistically is the famous silver axe in New York [1] with an almost identical shaft opening, but laced with silver wire, and hole for the dowel. The boar is less realistic, a hanging posture somewhat unnatural with a distortion to the front section of the upper part of its spine, to fit the function of the axe head and blend in with the rest. On our example the posture is naturalistic as would befit a dead boar. The eyes of both bear a similarity and their tails end in two separate tufts [2].

The New York axe is ritualistic and clearly thematic as it illustrates some myth, saga or religious belief which may explain a certain stiffness. For another wild boar, but with a tiger, his stripes inlaid in silver, and a goat, there is the bronze axe in London [3], very different for the shaft opening and mode of attachment with its multiple rivet holes and rivets. The eyes are shaped as round holes and were possibly once inlaid.

There is a fourth axe [4] with a boar in similar posture, in bronze - attacked from below by two lions, their hindquarters attached to a cylindrical shaft with a projection on its other side.

Shaft hole axes were made throughout the Near East over a long period. P. Amiet fully describes the considerable exchange of metalwork that took place towards the end of the 3rd millennium B.C. throughout vast expanses of Greater Iran. T. Potts tells us that the Sumerian examples are consistently plain whereas the more elaborate types are from the Luristan, Kerman/Lut and Bactrian regions. Luristan examples and others further east have animals in high relief along the butt, whereas Bactrian hammers and axes have an animal protome projecting from it. He further adds that there is very little evidence of exchange between Mesopotamia and the highland regions; however, if influence there was, it would have been with Susa and Luristan as they were close neighbours. However, there is "clear indication of an active and widespread exchange network stretching the entire breadth of the Iranian plateau from Bactria through south-east and south-central Iran as far as Susa" [5].

Where did our particular type of axe originate? This author feels that it was in Bactria. There is an interesting bronze hammer in Paris [6] with an inscription of Shulgi, from Susa, T. Potts [7] says it is typologically Bactrian with lock-like curls on the butt and birds' heads rising from the top, and is surely an exotic item. A very similar hammer [8] of purer stylization, finer workmanship, and in silver with the tail plumage partially gilt is also said to be from North Afghanistan.

The understanding of the nature of a wild boar would be in keeping with a Western-Central Asian provenance where the beast thrived in the lands around the Oxus. The distinctive mark of oval shape between the shoulders is neither a solar emblem nor a tuft of hair; may we suggest that it could be a clan identification [9]? The boar's juxtaposition with a lion - the latter possibly expressing the victory of the ruler over the dark forces of nature - would be well suited to ceremony and prestige.

1 Metropolitan Museum, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, James N. Spear and Schimmel Foundation, Inc. Gifts, 1982.5 (L: 15 cm): Pittman, H.: Art of the Bronze Age, Southeastern Iran, Western Central Asia and the Indus Valley. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 1984), p. 66 ff., fig. 36. Amiet, P.: L'âge des échanges inter-iraniens 3500-1700 avant J.-C. (Paris, 1986),pp. 195 ff., 317 fig. 173. Potts, T.: Mesopotamia and the East. An Archaeological and Historical Study of Foreign Relations 3400-2000 BC. Oxford Committee for Archaeology Monograph 37 (Oxford, 1994), p. 170 ff., fig 27.

2 Misdescribed in the above example as a split tail: Pittman, H.: op. cit., p. 67.

3 British Museum 123268 (L: 17.8 cm, misdated 5th-4th century B.C.): Dalton, O.M.: The Treasure of the Oxus with other examples of early Oriental Metal-work (London, 1964), no. 193, pp. 47-49, pl. XXIV. Amiet, P.: op. cit., pp. 195, 317 fig. 172.

4 Christie's, New York, 15 December, 1994, lot 68 ill. (L: 15.2 cm): its condition after extensive cleaning from what must have been a lump of chloride renders comparison of details difficult; however the shape of the eye seems to be as with the New York and present example.

5 Potts, T.: op. cit., p. 172.

6 Louvre Museum Sb 5634 (N 883; L: 11 cm; H: 9.3 cm), the inscription reads "Shulgi, powerful hero, king of Ur, king of Sumer and Akkad". Shulgi was a king of the Third Dynasty of Ur, he reigned in Mesopotamia in the last century of the 3rd millennium B.C.: Amiet, P.: Elam (Auvers-sur-Oise, 1966), no. 176, p. 243.

7 Potts, T.: op. cit., p. 176.

8 In the author's collection and said to be from the same region as this ceremonial axe, a very strong new indication of their provenance and manufacture.

9 In China, jades from Hongshan (Shanghai region) carried clan marks from c. 3500-1800 B.C. and bronzes from Erligang (name of site and period) at Zhengzhou, Honan, from 1800 B.C. onwards. This does not necessarily suggest a connection.

A Magnificent and Highly Important Bactrian Silver and Gold Foil Shaft-hole Axhead with a Bird-headed Demon, Boar, and Dragon

Silver and gold foil; Late 3rd-early 2nd Millennium B.C.E.; From Central Asia (Bactria-Margiana)

1982.5

Compare with: www.flickr.com/photos/antiquitiesproject/4616778973/#/

Western Central Asia, now known as Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and northern Afghanistan, has yielded objects attesting to a highly developed civilization in the late third and early second millennium B.C. Artifacts from the region indicate that there were contacts with Iran to the southwest. Tools and weapons, especially axes, comprise a large portion of the metal objects from this region.

This shaft-hole axhead is a masterpiece of three-dimensional and relief sculpture. Expertly cast in silver and gilded with gold foil, it depicts a bird-headed hero grappling with a wild boar and a winged dragon. The idea of the heroic bird-headed creature probably came from western Iran, where it is first documented on a cylinder seal impression. The hero's muscular body is human except for the bird talons that replace the hands and feet. He is represented twice, once on each side of the ax, and consequently appears to have two heads. On one side, he grasps the boar by the belly and on the other, by the tusks. The posture of the boar is contorted so that its bristly back forms the shape of the blade. With his other talon, the bird-headed hero grasps the winged dragon by the neck. The dragon, probably originating in Mesopotamia or Iran, is represented with folded wings, a feline body, and the talons of a bird of prey.

Source: Shaft-hole axhead with a bird-headed demon, boar, and dragon [Central Asia (Bactria-Margiana)] (1982.5) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Silver, late 3rd-early 2nd millennium B.C.E.

H. ? Image from the website of the Miho Museum.

Cylindrical cup with animals

![]() Western Central Asia

Western Central Asia

Silver

H. 11.0 cm, Dia. 9.5 cm

The torso surface of this silver cup is decorated with a leopard with legs spread as if running and a seated ibex. Plant forms are shown between these animals and designs which look like stars. Circles can be seen carved in the midst of the tree forms. At first glance this looks like a scene of a leopard hunting the ibex, and yet the seated ibex and leopard with mellow expression do not seem to construe a death attack scene. Ancient west Asia astronomy included both a leopard constellation and an ibex constellation, and around 4th millennium BC, these two constellations could be seen clearly in the spring equinoctial sky just before dawn. Thus it is thought that a combination of leopard and ibex probably symbolized the arrival of the new year. Further, in the Iranian highlands designs of the god spirit of the ibex grasping a snake have appeared since antiquity on seals, and this is thought to symbolize the god of the ibex ruling over the source of life, water. The combination of ibex, tree, and star design frequently can be seen on seals from Elam in southern Iran ca. 3,000 BC, and thus may have existed as an artistic expression in eastern Iran and western Central Asia under the influence of Elamite culture. In Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC, the ibex constellation was divided into the Aquarius constellation and the Capricorn constellation, while in ancient western Asia, the Taurus and Leo constellations could be seen right after the sun set at the spring equinox and came to symbolize the new year. A cylindrical seal from ca. 3,000 BC excavated at the Tell Agrab site on the Diyala River region of Iraq has this same motif combining a tree with a circular form, there combined with other plant motifs and a battle scene between a lion and a bull. Thus we can imagine that these symbolic designs had some important role in the culture of that period.

http://www.miho.or.jp/booth/html/artcon/00002110e.htm

Western Central Asia

Western Central Asia

Two views of Dupljaja Chariot 1.

Two views of Dupljaja Chariot 1.

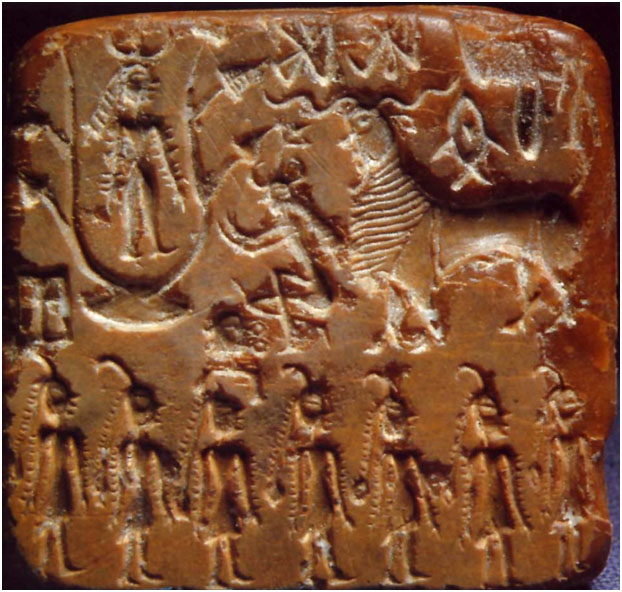

m478a tablet

m478a tablet m1186

m1186

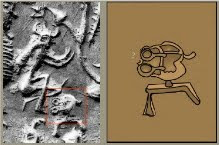

![clip_image062[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0624-thumb.jpg?w=99&h=45)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-961478688-5c5c5460c9e77c000159c260.jpg)

Rafflesia arnoldii

Rafflesia arnoldii

Trefoils painted on steatite beads, Harappa (After Vats, Pl. CXXXIII, Fig.2)

Trefoils painted on steatite beads, Harappa (After Vats, Pl. CXXXIII, Fig.2)

karā 'ear' rebus: khār 'blacksmith'.

karā 'ear' rebus: khār 'blacksmith'.

Sounds of language are organized with reference to place of articulation of the sounds in the vocal chord. (Picture courtesy Frits Staal)

Sounds of language are organized with reference to place of articulation of the sounds in the vocal chord. (Picture courtesy Frits Staal)