https://tinyurl.com/y3mhbuzx

Annex details the splendid metal- and lapidary-work repertoire of the artisans at the sites of Gola Dhoro (Bagasra), Shikarpur, Khirsara and Kanmer.

Shikarpur

I suggest that this Shikarpur seal with six dotted cicles signifies a smelter: baTa 'six' rebus: baTa 'iron' bhaTa 'furnace' PLUS dhA 'strand' dAyam 'one in dice' rebus: धाऊ dhāū m f A certain soft and red stone. See धाव. धाव dhāva m f A certain soft, red stone. Baboons are said to draw it from the bottom of brooks, and to besmear their faces with it.PLUS vRtta, vaTTa 'circle'; thus together dhAvAd 'smelter'.धावड dhāvaḍa m A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावडी dhāvaḍī a Relating to the class धावड. Hence 2 Composed of or relating to iron.(Marathi)

Kanmer

For a small-sized settlement of less than 2 hectares, stunning arrays of copper artefacts were found: A copper vessel containing eight bangles, an axe probably used for recycling precious metal, copper knives with bone handles have been found. A unique copper battle-axe (parashu) is also an interesting find from this area and the small size of the battle-axe suggests it as presumably used for ritualistic purpose. Heavily tampered clay crucibles with copper adhering in them have been found, suggesting that they might have been used for copper smelting.

Annex details the splendid metal- and lapidary-work repertoire of the artisans at the sites of Gola Dhoro (Bagasra), Shikarpur, Khirsara and Kanmer.

Shikarpur

I suggest that this Shikarpur seal with six dotted cicles signifies a smelter: baTa 'six' rebus: baTa 'iron' bhaTa 'furnace' PLUS dhA 'strand' dAyam 'one in dice' rebus: धाऊ dhāū m f A certain soft and red stone. See धाव. धाव dhāva m f A certain soft, red stone. Baboons are said to draw it from the bottom of brooks, and to besmear their faces with it.PLUS vRtta, vaTTa 'circle'; thus together dhAvAd 'smelter'.धावड dhāvaḍa m A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावडी dhāvaḍī a Relating to the class धावड. Hence 2 Composed of or relating to iron.(Marathi)

Kanmer

For a small-sized settlement of less than 2 hectares, stunning arrays of copper artefacts were found: A copper vessel containing eight bangles, an axe probably used for recycling precious metal, copper knives with bone handles have been found. A unique copper battle-axe (parashu) is also an interesting find from this area and the small size of the battle-axe suggests it as presumably used for ritualistic purpose. Heavily tampered clay crucibles with copper adhering in them have been found, suggesting that they might have been used for copper smelting.

The pictorial glyphs and the sign glyphs together constitute the listing of smithy/forge/metalguild workshop repertoire.

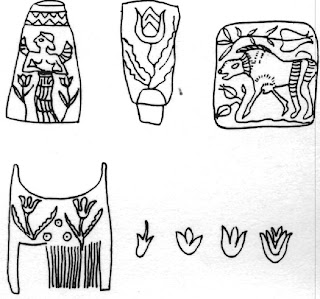

Three identical seal impressions of Kanmer are used on a string to constitute a set. The seal impressions are composed of the inscription:

khara 'equus hemionus' rebus:khār 'blacksmith

śrēṣṭrī 'ladder' Rebus: seṭh ʻ head of a guild, Members of the guild (working with a furnace). Thus, guild-master of the guild of blacksmiths.

Source:Kharakwal, JS, YS Rawat and Toshiki Osada, Excavations at Kanmer: A Harappan site in Kachchh, Gujarat, Puratattva, Number 39, 2009

Obverse and reverse of Kanmer tokens. Reverse has three different inscriptions. Courtesy: Toshiki Osada

An evidence comes from Kanmer, for the use of tablets created with duplicate seal impressions. These tablets may have been used as category tallies of lapidary workshops.

(Source: http://www.antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/agrawal323/Antiquity, D.P. Agrawal et al, Redefining the Harappan hinterland, Anquity, Vol. 84, Issue 323, March 2010). It is a category mistake to call these as ‘seals’. These are three duplicate tablets created with seal impressions (glyphs: one-horned heifer, standard device, PLUS two text inscription glyphs (or ‘signs’ as written characters): one long linear stroke, ligatured glyph of body + ‘harrow’ glyph. There are perforations in the center of these duplicate seal impressions which are tablets and which contained identical inscriptions. It appears that three duplicates of seal impressions -- as tablets -- were created using the same seal.

(Source: http://www.antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/agrawal323/Antiquity, D.P. Agrawal et al, Redefining the Harappan hinterland, Anquity, Vol. 84, Issue 323, March 2010). It is a category mistake to call these as ‘seals’. These are three duplicate tablets created with seal impressions (glyphs: one-horned heifer, standard device, PLUS two text inscription glyphs (or ‘signs’ as written characters): one long linear stroke, ligatured glyph of body + ‘harrow’ glyph. There are perforations in the center of these duplicate seal impressions which are tablets and which contained identical inscriptions. It appears that three duplicates of seal impressions -- as tablets -- were created using the same seal.

Obverse of these tiny 2 cm. dia. tablets show some incised markings. It is unclear from the markings if they can be compared with any glyphs of the Indus script corpora. They may be ‘personal’ markings like ‘potter’s marks’ – designating a particular artisan’s workshop (working platform) or considering the short numerical strokes used, the glyphs may be counters (numbers or liquid or weight measures). More precise determination may be made if more evidences of such glyphs are discovered. Excavators surmise that the three tablets with different motifs on the obverse of the three tablets suggest different users/uses. They may be from different workshops of the same guild but as the other side of the tables showed, the product taken from three workshops is the same.

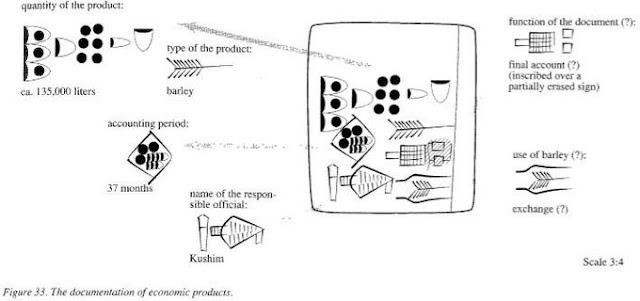

m1162. Mohenjo-daro seal with the same hieroglyph which appears on Kanmer circular tablets.

m1162. Mohenjo-daro seal with the same hieroglyph which appears on Kanmer circular tablets.  Glyph 33. Text 2068 kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa bronze'; kã̄sāri ʻpewterer’ (Bengali) kāḍ 2 काड् a man's length, the stature of a man (as a measure of length) Rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’. Ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ibbo 'merchant'.

Glyph 33. Text 2068 kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa bronze'; kã̄sāri ʻpewterer’ (Bengali) kāḍ 2 काड् a man's length, the stature of a man (as a measure of length) Rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’. Ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ibbo 'merchant'.khareḍo 'a currycomb' rebus kharada खरडें daybook PLUS karṇaka कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus kanahār 'helmsman'. Pictorial motif: karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron'. Thus, daybook of irnoworker, turner helmsman

m1162 Text 2058 Ligatured glyph of three sememes: 1. meḍ ‘body’(Mu.); rebus: ‘iron’ (Ho.); kāḍ 2 काड् a man's length, the stature of a man (as a measure of length); rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’; Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ , (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone; 2. aḍar ‘harrow’; rebus: aduru ‘native metal’. ibha ‘elephant’; rebus: ibbo ‘merchant’ (Gujarati)

kã̄ḍ reed Rebus: kāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’ Ku. lokhaṛ ʻiron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ(CDIAL 11171).

kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa= bronze (Te.) kã̄sāri ʻpewterer’ (Bengali) kãsārī; H. kasārī m. ʻ maker of brass pots’ (Or.) Rebus: kaṁsá1 m. ʻ metal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metal ʼ Pat. as in S., but would in Pa. Pk. and most NIA. lggs. collide with kāˊṁsya -- to which L. P. testify and under which the remaining forms for the metal are listed. 2. *kaṁsikā -- .1. Pa. kaṁsa -- m. ʻ bronze dish ʼ; S. kañjho m. ʻ bellmetal ʼ; A. kã̄h ʻ gong ʼ; Or. kãsā ʻ big pot of bell -- metal ʼ; OMarw. kāso(= kã̄ -- ?) m. ʻ bell -- metal tray for food, food ʼ; G. kã̄sā m. pl. ʻ cymbals ʼ; -- perh. Woṭ. kasṓṭ m. ʻ metal pot ʼ Buddruss Woṭ 109. 2. Pk. kaṁsiā -- f. ʻ a kind of musical instrument ʼ; A. kã̄hi ʻ bell -- metal dish ʼ; G. kã̄śī f. ʻ bell -- metal cymbal ʼ,kã̄śiyɔ m. ʻopen bellmetal panʼ kāˊṁsya -- ; -- *kaṁsāvatī -- ? Addenda: kaṁsá -- 1: A. kã̄h also ʻ gong ʼ or < kāˊṁsya – (CDIAL 2576). kāṁsya ʻ made of bell -- metal ʼ KātyŚr., n. ʻ bell -- metal ʼ Yājñ., ʻ cup of bell -- metal ʼ MBh., aka -- n. ʻ bell -- metal ʼ. 2. *kāṁsiya -- .[kaṁsá -- 1] 1. Pa. kaṁsa -- m. (?) ʻ bronze ʼ, Pk. kaṁsa -- , kāsa -- n. ʻ bell -- metal, drinking vessel, cymbal ʼ; L. (Jukes) kã̄jāadj. ʻ of metal ʼ, awāṇ. kāsā ʻ jar ʼ (← E with -- s-- , not ñj); N. kã̄so ʻ bronze, pewter, white metal ʼ, kas -- kuṭ ʻ metal alloy ʼ; A. kã̄hʻ bell -- metal ʼ, B. kã̄sā, Or. kãsā, Bi. kã̄sā; Bhoj. kã̄s ʻ bell -- metal ʼ,kã̄sā ʻ base metal ʼ; H. kās, kã̄sā m. ʻ bell -- metal ʼ, G.kã̄sũ n., M. kã̄sẽ n.; Ko. kã̄śẽ n. ʻ bronze ʼ; Si. kasa ʻ bell -- metal ʼ. 2. L. kã̄ihã̄ m. ʻ bell -- metal ʼ, P. kã̄ssī, kã̄sī f., H. kã̄sīf.*kāṁsyakara -- , kāṁsyakāra -- , *kāṁsyakuṇḍikā -- , kāṁsyatāla -- , *kāṁsyabhāṇḍa -- .Addenda: kāṁsya -- : A. kã̄h also ʻ gong ʼ, or < kaṁsá -- . (CDIAL 2987).*kāṁsyakara ʻ worker in bell -- metal ʼ. [See next: kāṁsya -- , kará -- 1] L. awāṇ. kasērā ʻ metal worker ʼ, P. kaserā m. ʻ worker in pewter ʼ (both ← E with -- s -- ); N. kasero ʻ maker of brass pots ʼ; Bi. H. kaserā m. ʻ worker in pewter ʼ. (CDIAL 2988). kāṁsyakāra m. ʻ worker in bell -- metal or brass ʼ Yājñ. com., kaṁsakāra -- m. BrahmavP. [kāˊṁsya -- , kāra -- 1] N. kasār ʻ maker of brass pots ʼ; A. kãhār ʻ worker in bell -- metal ʼ; B. kã̄sāri ʻ pewterer, brazier, coppersmith ʼ, Or. kãsārī; H. kasārī m. ʻ maker of brass pots ʼ; G.kãsārɔ, kas m. ʻ coppersmith ʼ; M. kã̄sār, kās m. ʻ worker in white metal ʼ, kāsārḍā m. ʻ contemptuous term for the same ʼ. (CDIAL 2989).

The evidence from Kanmer, shows the use of tablets created with duplicate seal impressions. These tablets may have been used as category tallies of lapidary, turners' workshops.

(Source: http://www.antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/agrawal323/Antiquity, D.P. Agrawal et al, Redefining the Harappan hinterland, Anquity, Vol. 84, Issue 323, March 2010). It is a category mistake to call these as ‘seals’. These are three duplicate tablets created with seal impressions (glyphs: one-horned heifer, standard device, PLUS two text inscription glyphs (or ‘signs’ as written characters): one long linear stroke, ligatured glyph of body + ‘harrow’ glyph. There are perforations in the center of these duplicate seal impressions which are tablets and which contained identical inscriptions. It appears that three duplicates of seal impressions -- as tablets -- were created using the same seal.

(Source: http://www.antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/agrawal323/Antiquity, D.P. Agrawal et al, Redefining the Harappan hinterland, Anquity, Vol. 84, Issue 323, March 2010). It is a category mistake to call these as ‘seals’. These are three duplicate tablets created with seal impressions (glyphs: one-horned heifer, standard device, PLUS two text inscription glyphs (or ‘signs’ as written characters): one long linear stroke, ligatured glyph of body + ‘harrow’ glyph. There are perforations in the center of these duplicate seal impressions which are tablets and which contained identical inscriptions. It appears that three duplicates of seal impressions -- as tablets -- were created using the same seal.

Obverse of these tiny 2 cm. dia. tablets show some incised markings. It is unclear from the markings if they can be compared with any glyphs of the Indus script corpora. They may be ‘personal’ markings like ‘potter’s marks’ – designating a particular artisan’s workshop (working platform) or considering the short numerical strokes used, the glyphs may be counters (numbers or liquid or weight measures). More precise determination may be made if more evidences of such glyphs are discovered. Excavators surmise that the three tablets with different motifs on the obverse of the three tablets suggest different users/uses. They may be from different workshops of the same guild but as the other side of the tables showed, the product taken from three workshops is the same.

'The perforations may have been used for inserting some kind of thread perhaps to hang it on the neck.' Three terracotta seal impressions all with perfoations (dia 4.15 mm) off center. Stamped by a squarish seal with a unicorn motif and two Indus hieroglyphs on top. All the three seal impressions have the same motif and hieroglyphs.

'The perforations may have been used for inserting some kind of thread perhaps to hang it on the neck.' Three terracotta seal impressions all with perfoations (dia 4.15 mm) off center. Stamped by a squarish seal with a unicorn motif and two Indus hieroglyphs on top. All the three seal impressions have the same motif and hieroglyphs. On the reverse, each one has a different picture or symbol (Kharakwal et al 2009: 147-163). These are comparable to the following Meluhha hieroglyphs:

Broken clay circular sealing. 2.05cmX2.03cmX0.90cm Wt. 2.7 g. Unicorn motif with three hieroglyphs. Comparable to Seal H156A, impression H156a (Harappa)

Kanmer. A large number of bead-making goods — 150 stone beads and roughouts, 160 drill bits, 433 faience beads and 20,000 steaite beads — were found here, indicating the site's importance as an industrial unit. Agatequarries were also located at a distance of 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the site. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanmer

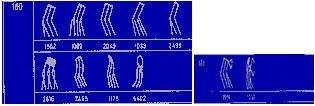

At the outset, this is a tribute to Asko Parpola and Juha Janhunen who hve identified some signs of the Indus Script Corpora as equus hemionus. I had read some of these signs as ranku 'antelope'; a correction is warranted in view of the identification of equus hemionus. Some of these signs have to read as khara, equus hemionus on rebus: khār 'blacksmith'The reading of this unique animal is read in this monograph as an Indus Script hypertext:

khara, equus hemionus on Indus Script rebus: khār 'blacksmith'

After Figure 15 in (Asko Parpola and Juha Janhunen, 2011, opcit., p.70) An Indus seal stamp (a) and its impression (b), with the wild ass as its heraldic motif, excavated at Kanmer, Kutch,Gujarat, in 2009 (photos by (a)Indus Project of RIHN, (b)Jeewan Singh Kharakwal) Decipherment of Kanmer seal:

खांडा [ khāṇḍā

Pictorial motif:khara 'onager or equus heminonus' rebus: khār 'blacksmith'. Thus the inscription conveys the message: metal equipment (made by) blacksmith.

Hieroglyph: joint of stalk, arrow: kāˊṇḍa (kāṇḍá -- TS.) m.n. ʻ single joint of a plant ʼ AV., ʻ arrow ʼ MBh., ʻ cluster, heap ʼ (in tr̥ṇa -- kāṇḍa -- Pāṇ. Kāś.). [Poss. connexion with gaṇḍa -- 2 makes prob. non -- Aryan origin (not with P. Tedesco Language 22, 190 < kr̥ntáti). Prob. ← Drav., cf. Tam. kaṇ ʻ joint of bamboo or sugarcane ʼ EWA i 197] Pa. kaṇḍa -- m.n. ʻ joint of stalk, stalk, arrow, lump ʼ; Pk. kaṁḍa -- , °aya -- m.n. ʻ knot of bough, bough, stick ʼ; Ash. kaṇ ʻ arrow ʼ, Kt. kåṇ, Wg. kāṇ, kŕãdotdot;, Pr. kə̃, Dm. kā̆n; Paš. lauṛ. kāṇḍ, kāṇ, ar. kōṇ, kuṛ. kō̃, dar. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ torch ʼ; Shum. kō̃ṛ, kō̃ ʻ arrow ʼ, Gaw. kāṇḍ, kāṇ; Kho. kan ʻ tree, large bush ʼ; Bshk. kāˋ'n ʻ arrow ʼ, Tor. kan m., Sv. kã̄ṛa, Phal. kōṇ, Sh. gil. kōn f. (→ Ḍ. kōn, pl. kāna f.), pales. kōṇ; K. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ stalk of a reed, straw ʼ (kān m. ʻ arrow ʼ ← Sh.?); S. kānu m. ʻ arrow ʼ, °no m. ʻ reed ʼ, °nī f. ʻ topmost joint of the reed Sara, reed pen, stalk, straw, porcupine's quill ʼ; L. kānã̄ m. ʻ stalk of the reed Sara ʼ, °nī˜ f. ʻ pen, small spear ʼ; P. kānnā m. ʻ the reed Saccharum munja, reed in a weaver's warp ʼ, kānī f. ʻ arrow ʼ; WPah. bhal. kān n. ʻ arrow ʼ, jaun. kã̄ḍ; N. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, °ṛo ʻ rafter ʼ; A. kã̄r ʻ arrow ʼ; B. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, °ṛā ʻ oil vessel made of bamboo joint, needle of bamboo for netting ʼ, kẽṛiyā ʻ wooden or earthen vessel for oil &c. ʼ; Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻ stalk, arrow ʼ; Bi. kã̄ṛā ʻ stem of muñja grass (used for thatching) ʼ; Mth. kã̄ṛ ʻ stack of stalks of large millet ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ wooden milkpail ʼ; Bhoj. kaṇḍā ʻ reeds ʼ; H. kã̄ṛī f. ʻ rafter, yoke ʼ, kaṇḍā m. ʻ reed, bush ʼ (← EP.?); G. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ joint, bough, arrow ʼ, °ḍũ n. ʻ wrist ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint, bough, arrow, lucifer match ʼ; M. kã̄ḍ n. ʻ trunk, stem ʼ, °ḍẽ n. ʻ joint, knot, stem, straw ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint of sugarcane, shoot of root (of ginger, &c.) ʼ; Si. kaḍaya ʻ arrow ʼ. -- Deriv. A. kāriyāiba ʻ to shoot with an arrow ʼ.(CDIAL 3023) Rebus: kaṇḍa 'equipment, metalware'.

After Figure 12 in (Asko Parpola and Juha Janhunen, 2011, opcit., p.68) Naturalistic variants of the Indus script sign 46 (in the sign list of Parpola 1994: 70-78) (from CISI 1-3/1). This is comparable to Signs 182 to 184 (including variants) of Mahadevan ASI 1977 Signlist Concordance.

The tail of the animal (Fig. 12 a to n) signifies: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy' PLUS xoli 'tail' rebus:kol 'working in iron'.Thus, iron smithy, forge.

The ears of the animal:karṇī 'ears' rebus: karaṇī 'supercargo, representative of the merchant responsible for the cargo'.

The stripes on body and neck on these images may be a scribe's style of identifying these body parts are semantic signifiers; for e.g.the rings on neck are read: kotiyum 'rings on neck' rebus: kod 'workshop'; G. koṭhɔ m., belly M. koṭhā m.(CDIAL 3545) rebus: kṓṣṭha2 n. ʻ pot ʼ Kauś., ʻ granary, storeroom ʼ MBh., ʻ inner apartment ʼ lex., ˚aka -- n. ʻ treasury ʼ, ˚ikā f. ʻ pan ʼ Bhpr. [Cf. *kōttha -- , *kōtthala -- : same as prec.?]

Pa. koṭṭha -- n. ʻ monk's cell, storeroom ʼ, ˚aka<-> n. ʻ storeroom ʼ; Pk. koṭṭha -- , kuṭ˚, koṭṭhaya -- m. ʻ granary, storeroom ʼ;WPah.kṭg. kóṭṭhi f. ʻ house, quarters, temple treasury, name of a partic. temple ʼ, J. koṭhā m. ʻ granary ʼ, koṭhī f. ʻ granary, bungalow ʼ; Garh. koṭhu ʻ house surrounded by a wall ʼ; Md. koḍi ʻ frame ʼ, <-> koři ʻ cage ʼ (X kōṭṭa -- ). -- with ext.: OP. koṭhārī f. ʻ crucible ʼ, P. kuṭhālī f., H. kuṭhārī f.; -- Md. koṭari ʻ room ʼ.(CDIAL 3546).

After Figure 13 (Asko Parpola and Juha Janhunen, 2011, opcit., p.69) Schematic variants of the Indus script sign 46 (in the sign list of Parpola 1994: 70-78) (from CISI 1-2)."...the ass and the rhinoceros. These two animals are associated with each other also in the copper tablets of Mohenjodaro. Identical inscription on the obverse links the Indus sign depicting the wild ass on the reverse of the tablets M-516 (see Figure 13 c-d) and M-517 with the rhinoceros illustrated on the reverse of the tablet M-1481." (ibid.)

The compound glyph on the 3 tablets refers to stone and bronze workshop. kāḍ kaṁsa koḍ 'stone, bronze workshop'. This reading is consistent with the archaeological finds at Kanmer. That a glyph similar to the one used on Kanmer tablets occur at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa is significant to help identify the Indian sprachbund with Meluhha (Mleccha) speech area.

It would appear that the three tablets (seal impressions) originated in three distinct phases of the lapidary/smithy processes, based on the following rebus readings of three distinct sets of incised glyphs on the obverse of the tablets. The three phases are: mineral workshop, furnce workshop (smithy), metal workshop (forge).

It would appear that the three tablets (seal impressions) originated in three distinct phases of the lapidary/smithy processes, based on the following rebus readings of three distinct sets of incised glyphs on the obverse of the tablets. The three phases are: mineral workshop, furnce workshop (smithy), metal workshop (forge).

maĩd ʻrude 'harrow or clod breakerʼ (Marathi) rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron'.

khareḍo 'a currycomb' (G.) Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) Rebus: kharada

खरडें daybook

Hieroglyph: kangha (IL 1333) 'comb' Rebus 1: ka~ghera_ comb-maker (H.) Rebus 2: kangar 1 कंगर् m. a large portable brazier; or kã̄gürü काँग&above;रू&below; or kã̄gar काँग््र्् । हसब्तिका f. (sg. dat. kã̄grĕ काँग्र्य or kã̄garĕ काँगर्य, abl. kã̄gri काँग्रि), the portable brazier, orkāngrī, much used in Kashmīr (K.Pr. kángár, 129, 131, 178; káṅgrí, 5, 128, 129). For particulars see El. s.v. kángri; L. 7, 25, kangar; and K.Pr. 129. The word is a fem. dim. of kang, q.v. (Gr.Gr. 37). kã̄gri-khŏphürü kangar ‘portable furnace’ (Kashmiri) kan:g portable brazier (B.); kā~guru, ka~gar (Ka.); kan:gar = large brazier (K.) kan:g = brazier, fireplace (K.)(IL 1332)खरडें daybook PLUS kanahār 'helmsman'. Thus, helmsman's daybook.![]() Sign 176 khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-

Sign 176 khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-

koḍa ‘one’(Santali) Rebus: koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’. kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. Hence, smith guild.

mēd ‘body’ (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) kāḍ 2 काड् a man's length, the stature of a man (as a measure of length); rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’; Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ , (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) id.

Pictorial motif: khoṇḍ, kõda 'young bull-calf' खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) ‘Pannier’ glyph: खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’. कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) The pictorial motif is read rebus as: - کار کنده kār-kunda 'adroit, clever, experienced, director, manager' (Pashto) konda 'furnace,kiln' kō̃da कोँद । कुलालादिकन्दुः f. a kiln; a potter's kiln (Rām. 1446; H. xi, 11); a brick-kiln (Śiv. 1033); a lime-kiln. -bal -बल् । कुलालादिकन्दुस्थानम् m. the place where a kiln is erected, a brick or potter's kiln (Gr.Gr. 165). --khasüñü --खस॑ञू॒ । कुलालादिकन्दुयथावद्भावः f.inf. a kiln to arise; met. to become like such a kiln (which contains no imperfectly baked articles, but only well-made perfectly baked ones), hence, a collection of good ('pucka') articles or qualities to exist. Cf. Śiv. 1033, where the causal form of the verb is used.(Kashmiri)

खरडें daybook

mēd ‘body’ (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) kāḍ 2 काड् a man's length, the stature of a man (as a measure of length); rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’; Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ , (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) id.

Pictorial motif: khoṇḍ, kõda 'young bull-calf' खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) ‘Pannier’ glyph: खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’. कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) The pictorial motif is read rebus as: - کار کنده kār-kunda 'adroit, clever, experienced, director, manager' (Pashto) konda 'furnace,kiln' kō̃da

Obverse side Indus Script hypertext: maĩdʻrude 'harrow or clod breakerʼ (Marathi) rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' PLUS Hieroglyph: कर्णक m. du. the two legs spread out AV. xx , 133 , 3 Rebus: कर्णिक having a helm; a steersman PLUS khonda singhi 'spiny-horned young bull' rebus: kunda singi 'fine gold, ornament gold'; konda singi, kUNDA singi 'fire-altar, ornament gold'. The obverse seal is made in three copies which are endorsed in three stages of metallurgical processing: alloying (furnace stage), smithy/forge, final approval by the guild-master. Rebus: kanahār'helmsman', karNI 'scribe, account''supercargo'. कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: 'helmsman', karNi 'supercargo'; meṛed 'iron' rebus: meḍh 'merchant' ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; 2. कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: 'helmsman', karṇi 'supercargo' Indicative that the merchant is seafaring metalsmith. karṇadhāra m. ʻ helmsman ʼ Suśr. [kárṇa -- , dhāra -- 1 ]Pa. kaṇṇadhāra -- m. ʻ helmsman ʼ; Pk. kaṇṇahāra -- m. ʻ helmsman, sailor ʼ; H. kanahār m. ʻ helmsman, fisherman ʼ.(CDIAL 2836) Decipherment: कर्णक 'helmsman' PLUS mē̃d, mēd 'body' rebus: mē̃d, mēd 'iron', med 'copper' (Slavic). Thus the body hieroglyph signifies mē̃d कर्णक karṇi 'an iron helmsman seafaring, supercargo merchant.'

Ligature hieroglyph: notch between the spread legs: खांडा [ khāṇḍā

It is surmised that the three tokens with three distinct inscriptions signify stages of metalwork processes: 1. furnace work; 2. alloying work; 2. blacksmith workshop (smithy, forge). The three tokens strung together would have been consolidated as cargo with an inscription on a seal handed over to the supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo, its transport by seafaring merchant and its sale.

Alternatively, Token 1 with an incised marking by śrēṣṭrī 'ladder' Rebus: seṭh ʻ head of a guild, Members of the guild (working with a furnace) and may signify the final approval process for the cargo shipment.

Token 3 of Kanmer

Hieroglyph: a pair of splinters: sal'splinter' rebus: sal'workshop' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' OR ganda'four' rebus: kanda'equipment'

baṭa = a kind of iron (G .) baṭa = rimless pot (Kannada)

S. baṭhu m. ‘large pot in which grain is parched, large cooking fire’, baṭhī f. ‘distilling furnace’; L. bhaṭṭh m. ‘grain—parcher's oven’, bhaṭṭhī f. ‘kiln, distillery’, awāṇ. bhaṭh; P. bhaṭṭh m., °ṭhī f. ‘furnace’, bhaṭṭhā m. ‘kiln’; S. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ‘distil (spirits)’. (CDIAL 9656)

Thus, one of the three tokens signifies with an inscription on the reverse of the token, that the cargo of equipment has been subjected to furnace processes..

Token 2 of Kanmer

ayo, hako 'fish'; a~s = scales of fish (Santali); rebus: aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.)

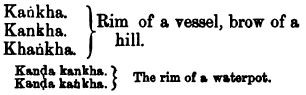

Sign 343 kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman' PLUS खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'. Thus, khāṇḍā karṇī 'metalware supercargo'.

Thus, this token has the message that the cargo alloy metal product has been endorsed by the supercargo at the fire trench account stage of processing.

Token 1 of Kanmer

![]() Enlarged view of the reverse side of one of the three Kanmer tokens. The inscription on the reverse side of this token is comparable to the two-sign sequence seen on a tablet from Khirsara1a. The incised signs depict (from right to left) 'wild ass' and 'ladder' (photo by Indus Project of RIHN).

Enlarged view of the reverse side of one of the three Kanmer tokens. The inscription on the reverse side of this token is comparable to the two-sign sequence seen on a tablet from Khirsara1a. The incised signs depict (from right to left) 'wild ass' and 'ladder' (photo by Indus Project of RIHN).

This is an addendum to:

https://tinyurl.com/y4bmewg6

![]() Sign 177 Herring bone? Ladder?On Kanmer seal impressions and on Khirsara tablet, this Sign 177 has been read as 'ladder'. An alternative reading is that the glyph signifies a herring bone or a ladder.

Sign 177 Herring bone? Ladder?On Kanmer seal impressions and on Khirsara tablet, this Sign 177 has been read as 'ladder'. An alternative reading is that the glyph signifies a herring bone or a ladder.

Herring bone (or, ladder?) Indus Script kuttu rebus kōḍa 'workshop' of khara 'equus hemionus' rebus: khār 'blacksmith' Alternatively, rebus reading is: Manḍ. gudgā- to blaze; gudva 'flame'; thus,

gudva khar'blacksmith (working with) bubbling hot, blazing flame'.

Another alternative is that the Sign 177 signifies NOT a herring bone but a ladder:

śrēṣṭrī 'ladder' Rebus: seṭh ʻ head of a guild, Members of the guild (working with a furnace). Thus, guild-master of the guild of blacksmiths.

Gola Dhoro is also called Bagasra.

![Image result for herring bone fish]()

![Image result for herring bone fish]() Herringbone pattern.

Herringbone pattern.

Design principles of pictographic Indus Script, gleaned from 'unicorn', 'rim-of-jar' https://tinyurl.com/yya6g9gf

Kanmer seal impression as a token has two signs on the obverse which are repeated as a two-sign sequence on Khirsara tablet.

Khirsara tablet two-sign sequence including the 'herring bone' hieroglyph.

The Khirsara tablet sequence is read rebus:

khara 'equus hemionus' rebus:khār 'blacksmith' PLUS kuttuvā 'herring bone' rebus: kōḍa 'workshop'. Thus, together, blacksmith workshop. The same reading may relate to the obverse of Kanmer seal impression 'token'. (Many dialectical variant phonetic forms of kuttuvā 'herring bone' include: kuṭṭa, kuṭṭai 'knotty log, handcuffs', khoḍ ʻ trunk or stump of a tree ʼ, ˚ḍā m. ʻ stocks for criminals ʼ. Hence, the rebus reading kōḍa 'workshop, place of work of artisans' is realised.

Is this seen as an extension of fish-fins which are read rebus: khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'? Or, maybe, this has an alternative reading: குத்தா kuttā, குத்துவா kuttuvā, n. A herring, golden, glossed with purple, Pellona brachysoma; கடல்மீன்வகை Rebus 1: Manḍ. gudgā- to blaze; gudva flame Rebus 2: kōḍa 'workshop'. gudva 'flame' is semantic cognate of: Ta. koti (-pp-, -tt-) to boil, bubble up from heat, effervesce, be heated (as the body, ground, etc.), be enraged, be offended, burn with desire; n. bubbling up (as of boiling water or oil), heat (as of fire, weather, etc.), fever, rage, grief, desire; koti-koti- to bubble up (as boiling rice); kotippu, kotiyal boiling, bubbling up, heat, fever, rage, grief; kotiyaṉ one who hankers after food; kutampu (kutampi-) to boil up, bubble up (as boiling water), get angry; kutukutu (-pp-, -tt-) to desire eagerly; kutukutuppu eagerness, desire. Ma. koti eagerness, greediness; kotikka to be greedy, envious, covet; kotiyan glutton. Ko. kodc- (kodc-) to quiver (of water about to boil, flesh of animal just killed, eyelid). To. kwïQ y- (. . .) (water) approaches boilingpoint; kwïQ yeṯ-, kwïQ kyeṯ- to make (water) boil; ? kwïy- (kwïc-) to bubble, boil. Ka. kudi to boil, bubble up, boil up, suffer pain or vexation in the mind; n. boiling, etc., grief; kudisu, kudiyisu, kudasu to boil (tr.); kudige, kudiha boiling, etc.; kutakuta, kotakota the noise of boiling water; kudakal, kudapal state of being (partially) boiled; (K.2 ) kuduguḷi glutton, greedy person; (Hav.) kodi to boil; desire to eat; n. boiling; kodippāṭu greedy. Koḍ. kodi- (kodip-, kodic-) to boil (intr.) with bubbling noise, feel love for, kiss, feel concerned for; kodi love, desire. Tu. kodipuni, kodiyuni to boil (intr.), seethe; kodipāvuni to cause to boil; kodipelů, kodupelů act of boiling; kodi greediness, eagerness; kudipuni, kudyuni to repent, regret; kudipēvuni to be desiring, wishing, be anxious. Te. goda hunger; goda-goda anger; goda-konu to be excited, be in haste, be hungry; kutakuta bubbling, simmering, the sound produced in boiling; kutakutalã̄ḍu to bubble, simmer, boil. Kur. xodᵒxnā (xudxyā) to be reduced to pulp by unskilful cooking; to get discouraged, despair; (xodxas) to reduce (by excessive cooking) to a soft uniform mass, cook until they fall to pieces; to worry, deprive of self-confidence, dishearten; (Hahn) xodxnā to burn (tr.) by overheating; (Pfeiffer). Malt. qothg̣e to excite, incline. / Cf. Skt. kutuka- curiosity, eagerness, desire for; kutūhala- id., impetuosity.(DEDR 2084) kutūhala कुतूहल a. 1 Wonderful. -2 Excellent, best. -3 Praised, celebrated. -लम् 1 Desire, curiosity; उज्झित- शब्देन जनितं नः कुतूहलम् Ś.1; यदि विलासकुलासु कुतूहलम् Gīt.1. (पपौ) कुतूहलेनेव मनुष्यशोणितम् R.3.54;13.21;15.65.

-2 Eagerness. -3 What excites curiosity, anything pleasing or interesting, a curiosity. -4 Delight, pleasure अकृत मधुरैरम्बानां मे कुतूहलमङ्गकैः U.1.2. कुतूहलिन् kutūhalin कुतूहलिन् a. 1 Desirous, struck with curiosity; Māl. 1. -2 Eager, impatient; न जातु स्यात्कुतूहली Ms.4.63.(Apte) कुतूहल mfn. excellent , celebrated W. (cf. कौतूहल.)a festival MBh. i , 7918 DivyA7v. i. (Monier-Williams)

meḍ 'iron'+ tagaram'tin'+ dul aduru 'cast native metal'.+ ayah, ayas 'metal' + aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace+ dhātu 'mineral'+ kolimi kanka 'smithy/forge account (scribe)'.

Thus, the smithy forge account is for iron, tin, cast native metal, unsmelted native metal, metal (alloy), mineral.

A bar seal with writing in Harappan script. Only one other bar seal figures in the total of 11 seals found so far in Khirsara.

Rebus readings of Indus writing (from r.): मेंढरी [ mēṇḍharī ] f A piece in architecture. मेंधला [mēndhalā] m In architecture. A common term for the two upper arms of a double चौकठ (door-frame) connecting the two. Called also मेंढरी & घोडा. It answers to छिली the name of the two lower arms or connections. (Marathi) meḍhi ‘pillar’. Rebus: meḍ 'iron'.

tagaraka 'tabernae montana' Rebus: tagaram'tin' (Malayalam)

sangaḍa ‘bangles’ (Pali). Rebus: sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. saghaḍī = furnace (G.) Rebus: jaṅgaḍ ‘entrustment articles’ sangaḍa ‘association, guild’. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul ‘casting’.

Ku. koṭho ʻlarge square houseʼ Rebus: Md. kořāru ʻstorehouseʼ

maĩd ʻrude harrow or clod breakerʼ (Marathi) rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron'

Alternative: aḍar ‘harrow’ Rebus: aduru = gaṇiyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul ‘casting’. Thus the composite glyph reds dul aduru 'cast native metal'.

ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.) Rebus: aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.)

ḍato = claws of crab (Santali); dhātu = mineral (Skt.), dhatu id. (Santali)

kanka 'rim-of-jar' Rebus: furnace account (scribe); khanaka 'miner' (Skt.). kolom 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge' (Telugu) The ligature of three strokes with rim-of-jar hieroglyph thus reads: kolimi kanka 'smithy/forge account (scribe)'.Bar seal. Khirsara. The fourth sign from r. also appears on early coins of mints. This sign signifies division with infixed notches; these signify: khaNDA 'division' PLUS khANDa 'notch' rebus: khaNDA 'equipment'

Five hieroglyphs read rebus:

Second sign from r.signifies pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus:pasra 'smithy, forge' (Santali)

ad.ar 'harrow' (Santali) Rebus: adaru 'native metal' (Kannada)

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' + as above: Thus, dul adaru 'cast native metal' ligatured to meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.Munda)

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' + as above: Thus, dul adaru 'cast native metal' ligatured to meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.Munda)ayo 'fish' (Munda)Rebus: ayas 'metal, alloy' (Samskritam)

kanka 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNi 'supercargo'; kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge' Thus, supercargo (from) forge

“Seals found in this site belong from the early stage to the late stage of the mature Harappan phase. There are rectangular seals depicting the unicorn and the bison and the Harappan characters. There are rectangular bar-type seals with the Harappan script alone and circular seals, all of which show that Khirsara is a mature Harappan site,” said Jitendra Nath, the excavator of the ongoing digs in Khirsara which commenced in 2009. Khirsara is a Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization site situated about 85 km from Bhuj town in Gujarat’s Kutch district. "There are a variety of beads made of shell and steatite and of semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli, agate, carnelian, chert, chalcedony and jasper. About 25,000 steatite beads were found in one trench alone. Shell bangles, shell inlays, copper bangles and rings were also found in plenty. Among copper implements were chisels, knives, needles, points, fish hooks, arrow-heads and weights. There were also bone tools, bone points and beads made out of bones...The ASI team found 11 seals, including circular seals. Some of them are carved with unicorn and bison images, and have the Harappan script engraved on them. While the unicorn seal is made of soapstone, the bison seal is made out of steatite. A rare discovery was that of two bar seals, both engraved with the Harappan script only and remarkably intact. “The kind of antiquities we are getting from this site indicates that Khirsara was a major industrial hub in western Kutch. It was located on a trade route from other parts of Gujarat to Sind in Pakistan, which is about 100 km away. Of course, the Harappans who lived here were basically traders, manufacturing industrial goods for export to distant lands and to other Harappan sites in the vicinity and farther away.” Khirsara is unique among Indus Valley settlements in having a general fortification wall around the settlement and also separate fortification walls around every complex inside the settlement. The citadel complex, the warehouse, the factory-cum-residential complex, and even the potters’ kiln have their own protective walls." http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/heritage/discovering-khirsaras-harappan-glory/article4794614.ece

Elephant glyph: ibha 'elephant' (Skt.) Rebus: ib 'iron' (Santali) ibbo 'merchant' (Gujarati)

Metal

ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.); kaṇḍa ‘arrow’; kaṇḍa, kāṇḍa, kāḍe = an arrow (Ka.) kāṇḍ kāṇ kōṇ, ko~_, ka~_ṛ arrow (Pas'.); ka~_ḍī arrow (G.) Cf. kaṇṭam ‘arrow’ (Ta.) Rebus: ayaskāṇḍa “a quantity of iron, excellent iron” (Pāṇ gaṇ)

Workshop

sal “stake, spike, splinter, thorn, difficulty” (H.);

Rebus: sal ‘workshop’ (Santali); śāla id. (Skt.)

Turner

kundau, kundhi corner (Santali) kuṇḍa corner (S.): khoṇḍ square (Santali) *khuṇṭa2 ʻ corner ʼ. 2. *kuṇṭa -- 2 . [Cf. *khōñca -- ] 1. Phal. khun ʻ corner ʼ; H. khū̃ṭ m. ʻ corner, direction ʼ (→ P. khũṭ f. ʻ corner, side ʼ); G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻ angle ʼ. <-> X kōṇa -- : G. khuṇ f., khū˘ṇɔ m. ʻ corner ʼ. 2. S. kuṇḍa f. ʻ corner ʼ; P. kū̃ṭ f. ʻ corner, side ʼ (← H.).(CDIAL 3898).

Allograph: kunta 'lance, spear' (Kannada)

Rebus: kunda1 m. ʻ a turner's lathe ʼ lex. [Cf. *cunda -- 1 ] N. kũdnu ʻ to shape smoothly, smoothe, carve, hew ʼ, kũduwā ʻ smoothly shaped ʼ; A. kund ʻ lathe ʼ, kundiba ʻ to turn and smooth in a lathe ʼ, kundowā ʻ smoothed and rounded ʼ; B. kũd ʻ lathe ʼ, kũdā, kõdā ʻ to turn in a lathe ʼ; Or. kū˘nda ʻ lathe ʼ, kũdibā, kū̃d° ʻ to turn ʼ (→ Drav. Kur. kū̃d ʻ lathe ʼ); Bi.kund ʻ brassfounder's lathe ʼ; H. kunnā ʻ to shape on a lathe ʼ, kuniyā m. ʻ turner ʼ, kunwā m. (CDIAL 3295). kundakara m. ʻ turner ʼ W. [Cf. *cundakāra -- : kunda -- 1 , kará -- 1 ] A. kundār, B. kũdār, °ri, Or. kundāru; H. kũderā m. ʻ one who works a lathe, one who scrapes ʼ, °rī f., kũdernā ʻ to scrape, plane, round on a lathe ʼ.(CDIAL 3297). Ta. kuntaṉam interspace for setting gems in a jewel; fine gold (< Te.). Ka. kundaṇa setting a precious stone in fine gold; fine gold; kundana fine gold.Tu. kundaṇa pure gold. Te. kundanamu fine gold used in very thin foils in setting precious stones; setting precious stones with fine gold. (DEDR 1725).

Ka. kunda a pillar of bricks, etc. Tu. kunda pillar, post. Te. kunda id. Malt. kunda block, log. ? Cf. Ta. kantu pillar, post.(DEDR 1723). கற்கந்து kaṟ-kantu , n. < கல் +. Stone pillar; கற்றூண். கற்கந்தும் எய்ப்போத்தும் . . . அனை யார் (இறை. 2, உரை, 27).

Details of the splendid metal- and lapidary-work repertoire of the artisans at the sites of Gola Dhoro (Bagasra), Shikarpur, Khirsara and Kanmer

The excerpts are from reports of Kuldeep Bhan, Massimo idale, JM Kenoyer, VH Sonawane, Ajit Prasad and Baroda University archaeological teams.

Dr. Kuldeep Bhan is Professor of Archaeology at MSU University Baroda and has been leading Indus excavations in Gujarat for the past 20 years.

Slides by Kuldeep Bhan(Professor of Archaeology at MSU University Baroda) which focus on the excavation and study of Gola Dhoro- the ancient Indus Valley archaeological site.

Gola Dhoro, Bagasra excavation map 1998. Plan of trench Eq 2, storage bins and fireplace.

Gola Dhoro excavated gateway on eastern side of the mound.

Gola Dhoro, Bagasra, gateway looking northwest over surrounding salt plains from the top of the mound.

Ancient Indus shell and stone beads from Gola Dhoro.

Unfinished shell bangles in the shell workshop, Gola Dhoro.

Complete raw shell Turbinella pyrum (right and left) and a pile of unfinished shell bangles (center).

Unfinished shell circlets with grinding stone in the front.

Some Important Aspects of Technology and Craft Production in the Indus Civilization with Specific Reference to Gujarat

It is really nice in a paper to be able to speak both of what is happening now, at the cutting-edge of bead and shell-making Indus craftsmanship and continuing discoveries, and be able to relate each tradition back to its earliest appearance in the subcontinent and elsewhere.

Excavations at Shikarpur 2007-2008: A Costal Port and Craft Production Center of the Indus Civilization in Kutch, India

Results from the exciting and continuing excavations on the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat.

Carnelian Bead Production in Khambat, India: An Ethnoarchaeological Study

An overview of the important technological and organization aspects of the carnelian bead industry that will be useful in developing interpretive models regarding the role of agate bead production in early urban societies.

Above: This carnelian bead has been artificially colored with white lines and circles using a special ancient bleaching technique.

This article presents an overview of the important technological and organization aspects of the carnelian bead industry that will be useful in developing interpretive models regarding the role of agate bead production in early urban societies.. The production and trade of various types of agate or Carnelian beads has an important role in local and regional economics of the prehistoric and historic periods in South Asia. At present the city of Khambhat (Cambay) is one of the largest stone bead working centres of the world, and it has been an important centre for over 3000 years of documented history. With the aid of archaeological research, the stone bead industry in Pakistan and western India can be traced back even earlier to the cities and villages of the Harappan phase of the Indus tradition, dated to around 2500 BC.

This article presents an overview of the important technological and organization aspects of the carnelian bead industry that will be useful in developing interpretive models regarding the role of agate bead production in early urban societies.. The production and trade of various types of agate or Carnelian beads has an important role in local and regional economics of the prehistoric and historic periods in South Asia. At present the city of Khambhat (Cambay) is one of the largest stone bead working centres of the world, and it has been an important centre for over 3000 years of documented history. With the aid of archaeological research, the stone bead industry in Pakistan and western India can be traced back even earlier to the cities and villages of the Harappan phase of the Indus tradition, dated to around 2500 BC.

Kenoyer1994_Carnelian%20Bead%20Production%20in%20Khambhat%20India%20An%20E.pdf

Contemporary Stone Beadmaking in Khambhat, India: Patterns of Craft Specialization and Organization of Production as Reflected in the Archaeological Record

Khambhat in Gujarat province provides a unique opportunity to study the organization of a specialized craft and understand how different aspects of social, economic and political organization relating to such crafts might be reflected in the archaeological record because of the long continuity of bead-making in this region,

At present, the city of Khambhat in western India is one of the largest stone beadworking centers of the world, and it has been an important center for over two thousand years of documented history (Arkell 1936;Trivedi 1964). Using archaeologicalevidence, the stone bead industry in this region of India can be traced back even earlier to the cities and villages of the Harappan Phase of the Indus Tradition, dated to around 2500 BC. Because of the long continuity of stone beadmaking in this region, Khambhat provides a unique opportunity to study the organization of a specialized craft and understand how different aspects of social, economic and political organization relating to such crafts might be reflected in the archaeological record. In archaeological studies of urbanism and so-called 'complex societies', craft specialization has come to be used as a major indicator of socio-economic complexity, stratification and centralized control. However, the many different definitions of specialized crafts and the contrasting interpretations of their role in prehistoric societies have led scholars to emphasize the need for more reliable interpretive models that correlate the socio-economic aspects of specialized crafts with the patterning of artifacts in the archaeological record.

Contemporary Stone Beadmaking in Khambhat, India: Patterns of Craft Specialization and Organization of Production as Reflected in the Archaeological Record Author(s): Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Massimo Vidale, Kuldeep Kumar Bhan Reviewed work(s): Source: World Archaeology, Vol. 23, No. 1, Craft Production and Specialization (Jun., 1991), pp. 44-63 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/124728

Ethnoarchaeological Excavations of the Bead Making Workshops of Khambat

Archaeologists interested in ancient craft production, both those aided by ancient historical sources and those bound to the interpretation of material residues, are currently involved in major critical efforts to improve the quality of their interpretation of the archaeological record.

An important step in this direction ís ethnoarchaeology. This approach enables us to observe, within living cultural systems, the cycles of formation and destruction of material evidence that are ultimately responsible for the creation of the archaeological record. At the same time, ethnoarchaeology permits to observe how the action of structured social relationships affects the nature of these cycles. Ethnoarchaeology, in this perspective, allows archaeologists to study dynamic and complex relationships of cause-effect among different orders of factors, and, as a result, to build with the data more meaningful tools of interpretation. South Asia, where traditional societies are organized in complex formalized hierarchies, with many different levels of interaction with contemporary state structures, is an ideal ñeld of ethnoarchaeological observation, relevant to the study of the so-called ‘complex societies’ of protohistory, dating to the bronze and iron age of the eurasian continent.

Chaîne Opératoire in the Study of Stratified Societies

This paper discusses some theoretical questions and present some observations on the role of ethnoarchaeological studies of craft production in contemporary stratified social contexts, in the study of protohistoric societies.

This paper discusses some theoretical questions and present some observations on the role of ethnoarchaeological studies of craft production in contemporary stratified social contexts, in the study of protohistoric societies. Ethnoarchaeological approaches to craft production include both the observation of site formation processes and archaeological patterning, as well as the the study of technology. We discuss the descriptive tools used by archaeologists and ethnologists to represent the continuum of stratigraphy and that of technology, as well as some theoretical implications of the comparison between these two approaches. We then examine the concept of "chaîne opératoire" or operational sequence, and propose that a non-linear approach to the study of production flow might be particularly useful for understanding highly segmented, hierarchical contexts of production.

Nageswara: a Mature Harappan Shell Working Site on the Gulf of Kutch, Gujarat

Recent explorations in the peripheral regions east of the Indus valley have established the spread of Harappan culture to settlements in Kutch, Saurashtra, Rajasthan and Harayana, but there has been much speculation on the reasons behind this cultural expansion.

In order to manufacture shell bangles from T. pyrum, the shell was first hollowed out by perforating the apex and breaking the internal septa using a long copper pick or chisel. The shell was then sawn at a diagonal to remove rough circlets, which were ground and polished to produce beautiful bangles

Recent explorations in the peripheral regions east of the Indus valley have established the spread of Harappan culture to settlements in Kutch, Saurashtra, Rajasthan and Harayana, but there has been much speculation on the reasons behind this cultural expansion. The discovery of Nageswara on the southern shore of the Gulf of Kutch, Gujarat, has provided important new information regarding the Harappan expansion in this region. The site is located on the edge of a fresh water reservoir called Bhimgaja Talao, (22 20' North Lat., 69 6' East Long.) which is associated with an ancient Saivite temple of Nageswara, Mahadeva. This temple is about 17 km northeast along the Dwarka-Gopi, Talao bus route. Since the excavators were interested in removing only the soft organic soil for construction of a dam, leaving large accumulations of potsherds, shel fragments, grinding stones and stone foundations in situ. This unique situation has made it possible to observe important architectural features and distribution of shell manufacturing waste in their original contexts.

Recent explorations in the peripheral regions east of the Indus valley have established the spread of Harappan culture to settlements in Kutch, Saurashtra, Rajasthan and Harayana, but there has been much speculation on the reasons behind this cultural expansion. The discovery of Nageswara on the southern shore of the Gulf of Kutch, Gujarat, has provided important new information regarding the Harappan expansion in this region. The site is located on the edge of a fresh water reservoir called Bhimgaja Talao, (22 20' North Lat., 69 6' East Long.) which is associated with an ancient Saivite temple of Nageswara, Mahadeva. This temple is about 17 km northeast along the Dwarka-Gopi, Talao bus route. Since the excavators were interested in removing only the soft organic soil for construction of a dam, leaving large accumulations of potsherds, shel fragments, grinding stones and stone foundations in situ. This unique situation has made it possible to observe important architectural features and distribution of shell manufacturing waste in their original contexts.

Excavations at Shikarpur, Gujarat 2008-2009

Sidis in the Agate Bead Industry of Western India

In this paper, historical records about the Sidis and their own oral traditions will be critically examined to gain new perspectives on their complex history, beginning with their origins in Africa and with a special focus on their role in the agate bead industry.

During drilling, the tips of agate drills become hot and often spall off. Fine screens allow the collection of the spalled drill tips, the finding of which confirms that drilling as well as shaping of beads was done in this area of the site during the Ravi phase.

Who are the Sidis and where did they come from?

These two questions can only be answered conclusively through care ful archaeological and DNA studies, but it is possible to make some sense out of the situation based on written documents and oral traditions. Some early anthropological studies of different racial groups in South Asia have shown that there are some Negrito groups among indigenous populations of hunter-gatherers living in parts of the West ern Ghats (Kadar and Irular of the Kerala Hills), and in the Raj Mahal Hills of Bihar and Bengal.

Who are the Sidis and where did they come from?

These two questions can only be answered conclusively through care ful archaeological and DNA studies, but it is possible to make some sense out of the situation based on written documents and oral traditions. Some early anthropological studies of different racial groups in South Asia have shown that there are some Negrito groups among indigenous populations of hunter-gatherers living in parts of the West ern Ghats (Kadar and Irular of the Kerala Hills), and in the Raj Mahal Hills of Bihar and Bengal.

"At present Sidi communities aree spread throughout the regions of Gujarat, Sindh and Makran, but only those lilving in the Gori Pit and Khambhat areas are involved in the agate trade."(p.69)

Copper knives with bone handles

Indus Valley copper artifacts found at Gola Dhoro.

Unique Unicorn Seal as part of some sort of container found at Gola Dhoro.![]()

Ancient Indus seal found at Gola Dhoro, frontal view.

Ancient Indus seals and sealings found at Gola Dhoro, Begasra.

![]() PLUS

PLUS ![]() These two hieroglyphs read from r. to l.: koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop' PLUS khareḍo 'a currycomb' rebus kharada खरडें daybook PLUS karṇaka कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus kanahār 'helmsman'. Thus, the message is: khareḍo koḍ karṇaka rebus: khareḍo 'daybook' (of) koḍ 'workshop' (of) kanahār 'helmsman'. Together, the inscription message is: daybook of workshop of helmsman. Three such seal impressions on three tokens of Kanmer constitute the consolidated cargo to be compiled on a seal message.

These two hieroglyphs read from r. to l.: koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop' PLUS khareḍo 'a currycomb' rebus kharada खरडें daybook PLUS karṇaka कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus kanahār 'helmsman'. Thus, the message is: khareḍo koḍ karṇaka rebus: khareḍo 'daybook' (of) koḍ 'workshop' (of) kanahār 'helmsman'. Together, the inscription message is: daybook of workshop of helmsman. Three such seal impressions on three tokens of Kanmer constitute the consolidated cargo to be compiled on a seal message.

khareḍo 'a currycomb' (G.) Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) Rebus: kharada

खरडें daybook

खरडें daybook PLUS kanahār 'helmsman'. Thus, helmsman's daybook.

![]() Sign 176 khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-

Sign 176 khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-

कर्णक m. du. the two legs spread out AV. xx , 133 'spread legs'; (semantic determinant) Rebus: kanahār'helmsman', karNI 'scribe, account''supercargo'. कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: 'helmsman', karNi 'supercargo'; meṛed 'iron' rebus: meḍh 'merchant' ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; 2. कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: 'helmsman', karṇi 'supercargo' Indicative that the merchant is seafaring metalsmith. karṇadhāra m. ʻ helmsman ʼ Suśr. [kárṇa -- , dhāra -- 1 ]Pa. kaṇṇadhāra -- m. ʻ helmsman ʼ; Pk. kaṇṇahāra -- m. ʻ helmsman, sailor ʼ; H. kanahār m. ʻ helmsman, fisherman ʼ.(CDIAL 2836) Decipherment: कर्णक 'helmsman' PLUS mē̃d, mēd 'body' rebus: mē̃d, mēd 'iron', med 'copper' (Slavic). Thus the body hieroglyph signifies mē̃d कर्णक karṇi 'an iron helmsman seafaring, supercargo merchant.'khoṇḍ, kõda 'young bull-calf' खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) ‘Pannier’ glyph: खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’. कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi)

ko_d.iya, ko_d.e = young bull; ko_d.elu = plump young bull; ko_d.e = a. male as in: ko_d.e du_d.a = bull calf; young, youthful (Te.lex.)

khareḍo 'a currycomb' (G.) Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) Rebus: kharada

खरडें daybook

खरडें daybook PLUS kanahār 'helmsman'. Thus, helmsman's daybook.

कर्णक m. du. the two legs spread out AV. xx , 133 'spread legs'; (semantic determinant) Rebus: kanahār'helmsman', karNI 'scribe, account''supercargo'. कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: 'helmsman', karNi 'supercargo'; meṛed 'iron' rebus: meḍh 'merchant' ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; 2. कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: 'helmsman', karṇi 'supercargo' Indicative that the merchant is seafaring metalsmith. karṇadhāra m. ʻ helmsman ʼ Suśr. [

ko_d.iya, ko_d.e = young bull; ko_d.elu = plump young bull; ko_d.e = a. male as in: ko_d.e du_d.a = bull calf; young, youthful (Te.lex.)

kot.iyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; kot. = neck (G.lex.) [cf. the orthography of rings on the neck of one-horned young bull].खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ]A variety of जोंधळा .खोंडरूं (p. 216) [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा -cowl.खोंडा (p. 216) [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. 2 fig. A hollow amidst hills; a deep or a dark and retiring spot; a dell. 3 (also खोंडी & खोंडें ) A variety of जोंधळा .खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा , to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.)

Rebus signifier of the rings on neck: A ghanjah or ganja (Arabic: غنجه ), also known as kotiya in India, is a large wooden trading dhow, a traditional Arabic sailing vessel. Thus, the rebus reading could be: kotiya 'a ghanjah dhow seafaring vessel'.

Kanmer epigraphs with Meluhha hieroglyphs used in trade

This is a tribute to the meticulous care with which JS Kharakwal and the team of archaeologists and epigraphists have documented the Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization site of Kanmer in Gujarat (Rann of Kutch). Even though the epigraphs are few, the archaeological work has provenienced the finds of seals/seal impressions/tablets with Meluhha hieroglyphs providing a unique opportunity to provide rebus readings of the hieroglyphs in the archaeological context of minerals and stones worked at the site to create trade-able artifacts such as beads, etched beads, perforated beads.

Location map of Kanmer (After Fig. 1 in:

Kanmer. A large number of bead-making goods — 150 stone beads and roughouts, 160 drill bits, 433 faience beads and 20,000 steaite beads — were found here, indicating the site's importance as an industrial unit. Agatequarries were also located at a distance of 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the site. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanmerhttp://www.scribd.com/doc/212393968/Kanmer-seals-sealing-and-other-script-material-Chapter-8

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/bronze-age-kanmer-bagasra.html

https://www.academia.edu/4891402/Harappan_Script_Material_from_Kanmer

Kanmer: seals, sealing and other script material (Chapter 8) Hansmukh Seth & JS Kharakwal, R. Menaria and H. Bunker (2014)

Three hieroglyphs painted in black pigment on a red slipped surface of a dish on stand (No. 09-2047) loa ‘ficus religiosa’

Rebus: lo 'copper'. ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'. Alternative: kamaṛkom,kamaḍha ‘ficus’ (Santali) Rebus: kammaṭa ‘mint, coiner’.

Five examples of hieroglyph in black pigment on the inner and outer surface of a pot of Red ware and redware with buffs slipped type oron dishes, mostly in pre-firing stage. arā 'spokes' Rebus: āra 'brass' eraka 'knave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'moltencast copper'.

(No. 09-2048; Tr. Z28, Layer 10; No. 09-2049; Tr. Z28, Layer 10; No. 09-2050; Tr. Z28, Qua SE, Layer 10; No. 09-2050, Tr. Z28, Qua SE, Layer 10); No. 09-2053; Tr. Z28, Layer 11).

(After Figure 9 in: Kharakwal et al, p. 364)"Furnace. A bulb shaped furnace with a central cylindrical hollow column (dia. 31 cm, depth 35 cm)(Fig.9) was exposed in trench Z17...The clay walls of the furnace were barely 4 cm thick and the area between the column and outer clay wall was found completely filled with ash. The burnt red colour of the cylindrical column, the outer clay wall and the earth around the furnace indicate that the temperature raised in the furnace may have been more than 700 degrees C...Several tubular faience beads and bangles were recovered from the furnace area and near the square platform. We do not know if it could be a faience bead making furnace?..."The beads of semi precious stone have been identified as carnelian, agate, lapis lazuli/sodalite, chalcedony, serpentine and bloodstone. The site yielded raw material of agate besides, chipped, roughouts, grinded, unpolished bead blanks...Except for lapis lazuli/sodalite, sources of raw material for all these bead types could have been the Little Rnn and its adjacent areas...A few examples of shell, bone and metal ones have been found from the KMR II and KMR III levels...The discovery of seals, seal impressions suggested that they were involved in trade." ( in: Kharakwal, JS, YS Rawat, T. Osada, LC Patel, Hanmukh Seth, Rajesh Meena, S. Meena, KP Singh, & A. Hussain, 2010, Kanmer: a multicultural site in Kachchh, Gujarat, India, p.371, 373)"

http://www.scribd.com/doc/212400235/Kharakwal-JS-YS-Rawat-T-Osada-LC-Patel-Hanmukh-Seth-Rajesh-Meena-S-Meena-KP-Singh-A-Hussain-Kanmer-a-multicultural-site-in-Kachchh-Gu (Embedded)

Etched carnelian bead from Kanmer (After Figure 11 in Kharakwal et al)

Khirsara1a tablet

Decipherment:Hypertext of ![]() Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS

Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS![]() Sign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace'

Sign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace'

khara 'equus hemionus' rebus:khār 'blacksmith [Alternative: ranku ‘antelope’; rebus: ranku ‘tin’ (Santali)]

śrēṣṭrī 'ladder' Rebus: seṭh ʻ head of a guild, Members of the guild (working with a furnace). [Alternative: panǰā́r ‘ladder, stairs’ (Bshk.)(CDIAL 7760) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)]

Thus, guild-master of the guild of blacksmiths.

badhi ‘to ligature, to bandage, to splice, to join by successive rolls of a ligature’ (Santali) batā bamboo slips (Kur.); bate = thin slips of bamboo (Malt.)(DEDR 3917). Rebus: baḍhi = worker in wood and metal (Santali) baṛae = blacksmith (Ash.)

kolmo ‘three’ (Mu.); rebus: kolimi ‘smithy’ (Te.)

khaṇḍ ‘division’; rebus: kaṇḍ ‘furnace’ (Santali) khaḍā ‘circumscribe’ (M.); Rebs: khaḍā ‘nodule (ore), stone’ (M.)

bharna = the name given to the woof by weavers; otor bharna = warp and weft (Santali.lex.) bharna = the woof, cross-thread in weaving (Santali); bharni_ (H.) (Santali.Boding.lex.) Rebus: bhoron = a mixture of brass and bell metal (Santali.lex.) bharan = to spread or bring out from a kiln (P.lex.) bha_ran. = to bring out from a kiln (G.) ba_ran.iyo = one whose profession it is to sift ashes or dust in a goldsmith’s workshop (G.lex.) bharant (lit. bearing) is used in the plural in Pan~cavim.s’a Bra_hman.a (18.10.8). Sa_yan.a interprets this as ‘the warrior caste’ (bharata_m – bharan.am kurvata_m ks.atriya_n.a_m). *Weber notes this as a reference to the Bharata-s. (Indische Studien, 10.28.n.2)

kuṭi = a slice, a bit, a small piece (Santali.lex.Bodding) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘iron smelter furnace’ (Santali)

Hieroglyph ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article'

![]() meḍhi 'plait' meḍ 'iron'; daürā 'rope' Rebus dhāvḍā 'smelter'

meḍhi 'plait' meḍ 'iron'; daürā 'rope' Rebus dhāvḍā 'smelter'

kṣōḍa m. ʻ post to which an elephant is fastened ʼ lex. [Poss. conn. with *khuṭṭa -- 1 with kh -- sanskritized as kṣ -- ]Pk. khōḍa -- m. ʻ boundary post ʼ, ˚ḍī -- f. ʻ big piece of wood, wooden bolt ʼ, taṁtukkhōḍī -- f. ʻ peg in a loom ʼ; N. khoriyo ʻ land on which trees have been cut and burnt and crops sown ʼ (< ʻ *having stumps ʼ?); H. khoṛ m. ʻ piece of wood ʼ, ˚ṛā m. ʻ stocks, handcuffs ʼ, khoṛkā m. ʻ stump of a tree ʼ; G. khoṛ n. ʻ large block of wood ʼ; M. khoḍ n. ʻ trunk or stump of a tree ʼ, ˚ḍā m. ʻ stocks for criminals ʼ.(CDIAL 3748) *khuṭṭa1 ʻ peg, post ʼ. 2. *khuṇṭa -- 1 . [Same as *khuṭṭa -- 2 ? -- See also kṣōḍa -- .]1. Ku. khuṭī ʻ peg ʼ; N. khuṭnu ʻ to stitch ʼ (der. *khuṭ ʻ pin ʼ as khilnu from khil s.v. khīˊla -- ); Mth. khuṭā ʻ peg, post ʼ; H. khūṭā m. ʻ peg, stump ʼ; Marw. khuṭī f. ʻ peg ʼ; M. khuṭā m. ʻ post ʼ.2. Pk. khuṁṭa -- , khoṁṭaya -- m. ʻ peg, post ʼ; Dm. kuṇḍa ʻ peg for fastening yoke to plough -- pole ʼ; L. khū̃ḍī f. ʻ drum -- stick ʼ; P. khuṇḍ, ˚ḍā m. ʻ peg, stump ʼ; WPah. rudh. khuṇḍ ʻ tethering peg or post ʼ; A. khũṭā ʻ post ʼ, ˚ṭi ʻ peg ʼ; B. khũṭā, ˚ṭi ʻ wooden post, stake, pin, wedge ʼ; Or. khuṇṭa, ˚ṭā ʻ pillar, post ʼ; Bi. (with -- ḍa -- ) khũṭrā, ˚rī ʻ posts about one foot high rising from body of cart ʼ; H. khū̃ṭā m. ʻ stump, log ʼ, ˚ṭī f. ʻ small peg ʼ (→ P. khū̃ṭā m., ˚ṭī f. ʻ stake, peg ʼ); G. khū̃ṭ f. ʻ landmark ʼ, khũṭɔ m., ˚ṭī f. ʻ peg ʼ, ˚ṭũ n. ʻ stump ʼ, ˚ṭiyũ n. ʻ upright support in frame of wagon ʼ, khū̃ṭṛũ n. ʻ half -- burnt piece of fuel ʼ; M. khũṭ m. ʻ stump of tree, pile in river, grume on teat ʼ (semant. cf. kīla -- 1 s.v. *khila -- 2 ), khũṭā m. ʻ stake ʼ, ˚ṭī f. ʻ wooden pin ʼ, khũṭaḷṇẽ ʻ to dibble ʼ.Addenda: *khuṭṭa -- 1 . 2. *khuṇṭa -- 1 : WPah.kṭg. khv́ndɔ ʻ pole for fencing or piling grass round ʼ (Him.I 35 nd poss. wrong for ṇḍ); J. khuṇḍā m. ʻ peg to fasten cattle to ʼ.(CDIAL 3893)

Ta. kuṭṭai, kuṭṭai-maram stocks; kaikkuṭṭai handcuffs. To. kuṭy, koy-kuṭy id.(DEDRF 1674) Ma. kuṭṭa a knotty log. Ko. guṭḷ stake to which animal is tied, any large wooden peg. To. kuṭy a stump. Ka. (Coorg) kuṭṭustem of a tree which remains after cutting it. Koḍ. kuṭṭe log. Tu. kuṭṭi stake, peg, stump. Go. (Mu.) kuṭṭa, guṭṭa, (G. Ma.) guṭṭa, (Ko.) guṭa stump of tree; (S.) kuṭṭa id., stubble; (FH.) kuta jowari stubble (Voc. 731). Pe. kuṭa stump of tree. Kui gūṭa, (K.) guṭa id. Kuwi (Su.) guṭṭu (pl. guṭka) id., stubble of paddy; (Isr.) kuḍuli log. / The items here, those in DBIA 104 (add: Go. [SR.] guṭṭam, [M.] guṭṭa, [L.] guṭā peg [Voc. 1112]), and those in Turner, CDIAL, no. 3893 *khuṭṭa-, *khuṇṭa- and no. 3748 kṣōḍa-, exhibit considerable convergence and present many problems of immediate relationship. (DEDR 1676) Ka. (Hav.) kutta straight up. Tu. (B-K.) kutta vertical, steep, straight.(DEDR 1716) குத்தா kuttā , n. A herring. See குத்துவா .குத்தாங்கல் kuttāṅ-kal , n. < குத்து- + ஆம் +. Stone or brick laid upright on edge; செங் குத்தாக வைக்குங் கல் அல்லது செங்கல்.குத்துக்கல் kuttu-k-kal , n. < id. +. 1. Stone standing on edge; செங்குத்தான கல் . 2. Bricks placed on edge, as in arching, terracing; செங்குத்தாகவைத்துக்கட்டுஞ் செங்கல் . 3. Stone marking the depth of water in a tank; ஏரிநீரின் ஆழத்தைக்காட்டும் அளவுகல் .குத்துவா kuttuvā , n. A herring, golden, glossed with purple, Pellona brachysoma; கடல்மீன்வகை . குத்துவாமீன் kuttuvā-mīṉ , n. < குத்துவா +. See குத்துவா .

Khirsara1a tablet

Decipherment:Hypertext of ![]() Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS

Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS![]() Sign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace'

Sign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace'

khara 'equus hemionus' rebus:khār 'blacksmith [Alternative: ranku ‘antelope’; rebus: ranku ‘tin’ (Santali)]

śrēṣṭrī 'ladder' Rebus: seṭh ʻ head of a guild, Members of the guild (working with a furnace). [Alternative: panǰā́r ‘ladder, stairs’ (Bshk.)(CDIAL 7760) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)]

Thus, guild-master of the guild of blacksmiths.

badhi ‘to ligature, to bandage, to splice, to join by successive rolls of a ligature’ (Santali) batā bamboo slips (Kur.); bate = thin slips of bamboo (Malt.)(DEDR 3917). Rebus: baḍhi = worker in wood and metal (Santali) baṛae = blacksmith (Ash.)

kolmo ‘three’ (Mu.); rebus: kolimi ‘smithy’ (Te.)

khaṇḍ ‘division’; rebus: kaṇḍ ‘furnace’ (Santali) khaḍā ‘circumscribe’ (M.); Rebs: khaḍā ‘nodule (ore), stone’ (M.)

bharna = the name given to the woof by weavers; otor bharna = warp and weft (Santali.lex.) bharna = the woof, cross-thread in weaving (Santali); bharni_ (H.) (Santali.Boding.lex.) Rebus: bhoron = a mixture of brass and bell metal (Santali.lex.) bharan = to spread or bring out from a kiln (P.lex.) bha_ran. = to bring out from a kiln (G.) ba_ran.iyo = one whose profession it is to sift ashes or dust in a goldsmith’s workshop (G.lex.) bharant (lit. bearing) is used in the plural in Pan~cavim.s’a Bra_hman.a (18.10.8). Sa_yan.a interprets this as ‘the warrior caste’ (bharata_m – bharan.am kurvata_m ks.atriya_n.a_m). *Weber notes this as a reference to the Bharata-s. (Indische Studien, 10.28.n.2)

kuṭi = a slice, a bit, a small piece (Santali.lex.Bodding) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘iron smelter furnace’ (Santali)

Hieroglyph ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article'

meḍhi 'plait' meḍ 'iron'; daürā 'rope' Rebus dhāvḍā 'smelter'

kṣōḍa m. ʻ post to which an elephant is fastened ʼ lex. [Poss. conn. with *

Ta. kuṭṭai, kuṭṭai-maram stocks; kaikkuṭṭai handcuffs. To. kuṭy, koy-kuṭy id.(DEDRF 1674) Ma. kuṭṭa a knotty log. Ko. guṭḷ stake to which animal is tied, any large wooden peg. To. kuṭy a stump. Ka. (Coorg) kuṭṭustem of a tree which remains after cutting it. Koḍ. kuṭṭe log. Tu. kuṭṭi stake, peg, stump. Go. (Mu.) kuṭṭa, guṭṭa, (G. Ma.) guṭṭa, (Ko.) guṭa stump of tree; (S.) kuṭṭa id., stubble; (FH.) kuta jowari stubble (Voc. 731). Pe. kuṭa stump of tree. Kui gūṭa, (K.) guṭa id. Kuwi (Su.) guṭṭu (pl. guṭka) id., stubble of paddy; (Isr.) kuḍuli log. / The items here, those in DBIA 104 (add: Go. [SR.] guṭṭam, [M.] guṭṭa, [L.] guṭā peg [Voc. 1112]), and those in Turner, CDIAL, no. 3893 *khuṭṭa-, *khuṇṭa- and no. 3748 kṣōḍa-, exhibit considerable convergence and present many problems of immediate relationship. (DEDR 1676) Ka. (Hav.) kutta straight up. Tu. (B-K.) kutta vertical, steep, straight.(DEDR 1716)

Three tokens were discovered in Kanmer with Indus Script inscriptions on both sides of the tokens. This monograph deciphers the inscriptionsand finds documentation of metalwork processes in furnace, alloying and smithy-forge. It is surmised that the three token set strung together may have resulted in the preparation on a seal of a bill of lading authenticating the products entrusted to the supercargo.

Location of Kanmer. Rann of Kuttch

![]() Khirsara1a tablet

Khirsara1a tablet

Decipherment:Hypertext of ![]() Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS

Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS![]() Sign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace'

Sign 328 baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace'

khara 'equus hemionus' rebus:khār 'blacksmith [Alternative: ranku ‘antelope’; rebus: ranku ‘tin’ (Santali)]

śrēṣṭrī 'ladder' Rebus: seṭh ʻ head of a guild, Members of the guild (working with a furnace). [Alternative: panǰā́r ‘ladder, stairs’ (Bshk.)(CDIAL 7760) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)]

Thus, guild-master of the guild of blacksmiths.

badhi ‘to ligature, to bandage, to splice, to join by successive rolls of a ligature’ (Santali) batā bamboo slips (Kur.); bate = thin slips of bamboo (Malt.)(DEDR 3917). Rebus: baḍhi = worker in wood and metal (Santali) baṛae = blacksmith (Ash.)

kolmo ‘three’ (Mu.); rebus: kolimi ‘smithy’ (Te.)

khaṇḍ ‘division’; rebus: kaṇḍ ‘furnace’ (Santali) khaḍā ‘circumscribe’ (M.); Rebs: khaḍā ‘nodule (ore), stone’ (M.)

bharna = the name given to the woof by weavers; otor bharna = warp and weft (Santali.lex.) bharna = the woof, cross-thread in weaving (Santali); bharni_ (H.) (Santali.Boding.lex.) Rebus: bhoron = a mixture of brass and bell metal (Santali.lex.) bharan = to spread or bring out from a kiln (P.lex.) bha_ran. = to bring out from a kiln (G.) ba_ran.iyo = one whose profession it is to sift ashes or dust in a goldsmith’s workshop (G.lex.) bharant (lit. bearing) is used in the plural in Pan~cavim.s’a Bra_hman.a (18.10.8). Sa_yan.a interprets this as ‘the warrior caste’ (bharata_m – bharan.am kurvata_m ks.atriya_n.a_m). *Weber notes this as a reference to the Bharata-s. (Indische Studien, 10.28.n.2)

kuṭi = a slice, a bit, a small piece (Santali.lex.Bodding) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘iron smelter furnace’ (Santali)

Hieroglyph ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article'

meḍhi 'plait' meḍ 'iron'; daürā 'rope' Rebus dhāvḍā 'smelter'

See A11 and B5 in figure.

Field symbol: short-tailed caprid kid: ranku ‘antelope’ rebus: khara 'equus hemionus' rebus:khār 'blacksmith' or ranku ‘tin’ + xolā 'fish tail' rebus: kolhe 'smelter',

kol 'working in iron'

Text A11: Glyph ‘mountain’: మెట్ట [ meṭṭa ] or మిట్ట meṭṭa. [Tel.] n. Rising ground, high lying land, uplands. A hill, a rock. ఉన్నతభూమి, మెరక, పర్వతము, దిబ్బ. மேடு mēṭu , n. [T. meṭṭa, M. K. mēḍu.] 1. Height; உயரம். (பிங்.) 2. Eminence, little hill, hillock, ridge, rising ground; சிறுதிடர். (பிங்.) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic)

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

gaṇḍá4 m. ʻ rhinoceros ʼ lex., ˚aka -- m. lex. 2. *ga- yaṇḍa -- . [Prob. of same non -- Aryan origin as khaḍgá -- 1 : cf. gaṇōtsāha-- m. lex. as a Sanskritized form ← Mu. PMWS 138]1. Pa. gaṇḍaka -- m., Pk. gaṁḍaya -- m., A. gãr, Or. gaṇḍā. 2. K. gö̃ḍ m., S. geṇḍo m. (lw. with g -- ), P. gaĩḍā m., ˚ḍī f., N. gaĩṛo, H. gaĩṛā m., G. gẽḍɔ m., ˚ḍī f., M. gẽḍā m. Addenda: gaṇḍa -- 4 . 2. *gayaṇḍa -- : WPah.kṭg. ge ṇḍɔ mi rg m. ʻ rhinoceros ʼ, Md. genḍā ← H.(CDIAL 4000) rebus: kaṇḍa .'fire-altar','equpment'

Field symbol: feeding trough + rhinoceros:pattar 'trough' rebus: pattar 'goldsmiths' guild' PLUS : kāṇṭā'rhinoceros. Rebus: kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Gujarati)

Text B5: మెట్ట [ meṭṭa ] or మిట్ట meṭṭa. [Tel.] n. Rising ground, high lying land, uplands. A hill, a rock. ఉన్నతభూమి, మెరక, పర్వతము, దిబ్బ. மேடு mēṭu , n. [T. meṭṭa, M. K. mēḍu.] 1. Height; உயரம். (பிங்.) 2. Eminence, little hill, hillock, ridge, rising ground; சிறுதிடர்.

(பிங்.) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic)

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī

'supercargo, scribe, helmsman'

m0517

m0517The person with upraised arm and bovine legs and tail is a blacksmith: eraka 'upraised arm' rebus: 'moltencast' + dhangar 'bull' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'. Some details at http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2018/04/orthographic-hypertext-devices-eg-tiger.html

Equus hemionus khur or Baluchi wild-ass. called ghudkhur (Gujarati) or ghor-khur a semantic expression combing ghōṭa 'horse' PLUS khara 'ass'. An example of such an expression in a dialect is: Persian, 'wild ass, onager' is called also gōr-

χar. "Middle and New Persian χar has cognates in Younger Avestan χara-, Khotanese Saka khara,

Sogdian (Buddhist) γr-, (Manichean, Christian) χr-, and practically all Neo-Iranian languages.."

(cf. Parpola, Asko, and Juha Janhunen, 2011, opcit., p.79)

Ossetic χarag, χarag, Munji χara-, Tajik, Baluchi, Pashto, Yaghnobi χar, Parachi khȫr, Sanglichi χor, χōr, Yigdha χoro, Ishkashmi, Yazghulami χůr, Wakhi χur, Kurdish ker, (Gurānī) har, Sariqoli čer, šer, Bartangi šor, Roshani šur, Rushani, Khufi šōr, (fem.) šār (cf. Horn 1893: 104 no. 473; Steblin-Kamenskij 1999: 409). Gypsy (Palestinian) ḳar m. ḳari f., (Armenian) χari, (Greek) kher, (Rumanian) χeru, Kati kur, Prasun korū, Ashkun kɘrɘṭek, Shumashti χareṭa, Khowar khairanu 'donkey's foal'), Bashkarik kur, Dameli khar m., khari f., Tirahi khar, Pashai (Laurowani) khar m., khar f., Kalasha (Urtsun) khār, Phalura khār m., khari, Kashmiri khar m.,khuru f., Sindhi kharu m., Lahnda kharkā m., kharkī f., Panjabi, Gujarati, Marathi, Hindi khar m. Old Marathi khari f. (Turner 1966 and 1985: no. 3818; McGregor 1993: 230a; a detailed analysis of the Nuristani and Dardic data in Fussman 1972 I: 60-62).

khara1 m. ʻ donkey ʼ KātyŚr., ˚rī -- f. Pāṇ.NiDoc. Pk. khara -- m., Gy. pal. ḳăr m., kắri f., arm. xari, eur. gr. kher, kfer, rum. xerú, Kt. kur, Pr. korūˊ, Dm. khar m., ˚ri f., Tir. kh*l r, Paš. lauṛ. khar m., khär f., Kal. urt. khār, Phal. khār m., khári f., K. khar m., khürü f., pog. kash. ḍoḍ. khar, S. kharu m., P. G. M. khar m., OM. khari f.; -- ext. Ash. kərəṭék, Shum. xareṭá; <-> L. kharkā m., ˚kī f. -- Kho. khairánu ʻ donkey's foal ʼ (+?).*kharapāla -- ; -- *kharabhaka -- .Addenda: khara -- 1 : Bshk. Kt. kur ʻ donkey ʼ (CDIAL 3818) Ta. kar̤utai ass. Ma. kar̤uta id.

Ko. kaṛt id.; kaḷd a term of abuse. To. katy ass. Ka. kar̤te,katte. Koḍ. katte. Tu. katte. Te. gāḍida.

Kol. ga·ḍdi. Nk. gāṛdi.Pa. gade, (S.) garad. Go. (G. Ko.) gāṛdi (Voc. 1073). Kuwi (Su.) gāṛde. / Cf. Skt. gardabha-; Turner, CDIAL, no. 4054.(DEDR 1364) gardabhá m. ʻ ass ʼ RV., ˚bhīˊ -- f. AV., ˚bhaka -- m. ʻ any- one resembling an ass ʼ Kāś. [√gard ]Pa. gaddabha -- , gadrabha -- m., ˚bhī -- f., Pk. gaddaha -- , ˚aya -- , gaḍḍaha -- m., gaddabhī -- f., Gy. as. ghádar JGLS new ser. ii 255 (< gadrabha -- ?), Wg. gadāˊ, Niṅg. gadə́, Woṭ. gadāˊ m., ˚daī f., Gaw. gadāˊ m., ˚deṛi f., Kho. gordóg (< gardabhaka -- ; → Kal. gardɔkh as the Kalashas have no donkeys, G. Morgenstierne FestskrBroch 150), Bshk. g*l dāˊ m., ˚dḗī f., Tor. godhṓ m., gedhḗi f., Mai. ghadā, Sv. gadaṛṓ, S. gaḍahu m., L. gaḍḍãh m., ˚ḍẽh f., (Ju.) gaḍ̠ -- hã̄ m., ˚hī f. ʻ ass, blockhead ʼ; P. gadhā m., ˚dhī f., WPah. pāḍ. cur. cam. Ku. gadhā, N. gadoho m., ˚dahi f., A. gādh m., ˚dhī f., B. gādhā m., ˚dhīf., Or. gadha m., ˚dhuṇī f. ʻ ass ʼ, gadhā ʻ blockhead ʼ; Bi. Mth. Bhoj. H. gadahā m., ˚hī f., OG. ghaddaü m., G. gaddhɔ m., ˚dhī f., M. gāḍhav m., ˚ḍhvī f. (lw. gadhḍā m.), Ko. gāḍhū, Si. gäḍum̆buvā (gadubuvā ← Pa.).Addenda: gardabhá -- : S.kcch. gaḍoṛī f. ʻ she -- ass ʼ; WPah.kṭg. (kc.) gáddhɔ m. ʻ donkey ʼ, Garh. gardhā, gadṛu, A. gādha (CDIAL 4054) ghōṭa m. ʻ horse ʼ ĀpŚr., ˚ṭī -- f. Aśvad., ˚ṭaka -- m. Pañ- cat., ˚ṭikā -- f. lex. [Non -- Aryan, prob. Drav., origin EWA i 361 with lit.]Pa. ghōṭaka -- m. ʻ poor horse ʼ; Pk. ghōḍa -- , ˚ḍaya -- m., ˚ḍī -- f. ʻ horse ʼ, Gy. as (Baluči) gura, pers. gôrá, pal. gṓri f., arm. khori ʻ horse ʼ, eur. khuro m., ˚rī f. ʻ foal ʼ, boh. pol. khuro ʻ stallion ʼ; Ash. gọ̄́ṛu m. ʻ horse ʼ, gọ̈̄räˊ f., Wg. gọ̄́ṛa, Pr. irí, Dm. gọŕɔ m., guŕi f., Paš. gōṛāˊ, Niṅg. guṛə́, Shum. gṓṛo, Woṭ. gōṛm., gēṛ f., Gaw. guṛɔ́ m., guṛīˊ f., Kal. urt. ghɔ́̄ŕ*l , Bshk. gór m., gēr f., Tor. ghō m., ghəē f. (aspirate maintained to distinguish from gō ʻ bull ʼ J. Bloch BSL xxx 82), Mai. ghå m., ghwī f., Chil. Gau. gho, Sv. ghuṛo m., g'uṛia f., Phal. ghūṛu m., ˚ṛi f., Sh. *gōu (→ Ḍ. gōwá), K. guru m., ˚rü f., (Islamābād) guḍü , rām. pog. ghōṛŭ, kash. ghuṛŭ, ḍoḍ. ghōṛō, S. ghoṛo m., ˚ṛī f., L. P. ghoṛā m., ˚ṛī f., in cmpds. ghoṛ -- , WPah. ghoṛo m., ˚ṛī f., ˚ṛu n. ʻ foal ʼ, Ku. ghoṛo, A. ghõrā, in cmpds. ghõr -- , B. ghõṛā m., ghũṛi f. (whence Chittagong ghunni ODBL 695), Or. ghoṛā, ˚ṛī, Bi. ghor, ˚rā, OAw. ghora, H. ghoṛ, ghoṛā m., ṛī f. (→ N. Bhoj. ghoṛā, N. ˚ṛi, Bhoj. ˚ṛī), Marw. ghoṛo m., G. ghoṛɔ m., ˚ṛī f., ˚ṛũ n. ʻ poor horse ʼ, M. ghoḍā m., ˚ḍī f., Ko. ghoḍo.