Is there any Dravidian connection with the Rigveda or with the Harappan civilization in the northwest of India? This is an extremely contentious and controversial issue which arouses passion and rhetoric on all sides. It has been a central political claim of the Dravidianist movement in India that the Harappan Civilization was a Dravidian speaking civilization. This claim was not however initiated by them. It was initiated by western academic scholars and Indologists as a natural corollary of the Aryan Invasion Theory (AIT) which had "Aryans" (Indo-European speakers) invading or migrating into India around 1500 BCE. Anything found in India before that date could only be "non-Aryan", and when the Harappan sites were discovered at the beginning of the 20th century and found to be datable to as far back as the fourth millennium BCE with roots going much further back in the area, it automatically became "non-Aryan"; and for many reasons, the Dravidian language family seemed the most logical "non-Aryan" candidate.

The AIT itself was based on what the linguists and Indologists claimed or believed to be a logical interpretation of the linguistic data: that the Indo-European languages had originated in the Steppes. It was not however a genuine interpretation of the actual linguistic data, but an extremely myopic and predetermined analysis and interpretation which selected convenient pieces of data and ignored inconvenient ones, and then force-fitted conclusions which actually went directly opposite to what was shown by even that conveniently selected data! That is an issue which will have to be handled in a separate article to bring together in one place all the linguistic evidence, most of which is scattered over my various books and articles and will require to be brought together (with some new inputs) to show the true linguistic position.

The AIT is now as dead as a dodo, regardless of whether its proponents accept it or not - in time (except for the most die-hard cranks among them) they will be left with no option but to accept it. There are basically only three scientific disciplines which can help in analyzing and solving the problem of the Original Homeland of the Indo-European language family: Linguistics, Archeology (and related disciplines) and Textual Analysis. The data and evidence in all these three disciplines now irrefutably establishes that the Indo-European Homeland was in North India, and that the migrations of the speakers of the eleven other Indo-European dialects from India took those dialects, which became the eleven known branches, to their historical habitats. All this evidence is given in my books and other articles. Recent desperate attempts to abandon these three scientific disciplines and claim evidence for the AIT on the basis of "genetic" data and evidence has been blown to bits in my recent book "Genetics and the Aryan debate" and my recent blog article "Rakhigarhi and After". So I will not go into or repeat all that again here in this article.

I have proved in full detail in my books and articles that the Mature Harappan civilization is identical with the New Rigvedic civilization, roughly datable from 2600-1700 BCE. Here in this article I will only go into the question of whether or not there is any connection between the Dravidian languages on the one hand and the Harappan Civilization and the Rigveda on the other.

There are allegations of a Dravidian "substrate" in the Rigveda, indicating that the Harappan people of the area originally spoke Dravidian languages until they were supplanted by "Aryan" invaders (who borrowed some words from the Dravidian languages) or were themselves converted to Indo-European speech (retaining some Dravidian words in their adopted language). Here we will only investigate whether there are indeed any Dravidian words in the Rigveda, and if so exactly what they actually indicate.

Three points to keep in mind:

1. When there are two similar-sounding words, with the same or a closely related meaning, in two languages which are not related to each other (and therefore the two words cannot be cognate or related words from a common ancestral source) and which have not borrowed from a common third source or related third sources (e.g. from English or Sanskrit or Arabic, or one from Spanish and the other from Italian), it can mean that the word was originally found in one of the two languages and the other language has received that word from the first language. In such cases, the word is usually an adstrate word (an extraneously borrowed word).

It can be called a substrate word only in a special circumstance: when the speaker of the second language is known to have come from some other place, and either all the local people who were originally speakers of the first language have completely switched over to the second language and this word is a carryover from the original (i.e. the first) language. When Indians intersperse some English words in speaking their mother-tongues, or some words from their living mother-tongue in speaking English, these cannot be called substrate words.

2. Sometimes, the similarity in sound and meaning can be deceptive. Take the three following words in Tamil and English as examples:

eṭṭu = eight.

maṇ = mud.

veṭṭri = victory.

Here the concerned Tamil and English words are not related to each other, nor is one borrowed from the other.

Similarity situations of this kind give much scope for manipulation and fake claims, and for extremely selective and convenient acceptance and rejection of the linguistic-cognate principle: thus, for example, Mallory and Adams tell us that one of the four words which prove Semitic influence on Proto-Indo-European in the formative period is the word for the number "seven": "Proto-Indo-European *septṁ 'seven': Proto-Semitic *sab'atum", and that this shows geographical proximity between the two proto-languages in or near West Asia. However, the linguists firmly refuse to even consider the evidence of the similarity of the first four numbers in Proto-Indo-European (*sem, *dwōu/*dwai, *tri and *qwetwor) and Proto-Austronesian (*esa, *dewha, *telu and *pati/*epati) in locating the PIE Homeland in the east: the first four numbers in Malay are sa/satu 'one', dua 'two', tiga 'three', epat 'four'. The dua and tiga need no explanation for an Indo-European speaker; for the other two, we have Tocharian sas/se 'one', Romanian patru 'four', Welsh pedwar 'four'.

3. But the manipulation goes much further. Finding "non-Aryan" names in the Rigveda is vital for perpetuating the narrative of "non-Aryan" natives vs. "Aryan invaders", and therefore hunting out "non-Aryan names" and words in the Rigveda has become a massive cottage industry in the field of Indo-European studies.

In my first two books, in 1993 (pp.266-291) and 2000 (pp.345-362), I have shown the extremely and unbelievably absurd extent to which various AIT-promoting writers can go to in discovering "non-Aryans" (i.e. non-Indo-Europeans) in the Rigveda:

To begin with, the most popular candidates for the "non-Aryan" identity are dāsas, dasyus, asuras, paṇis, yakṣas, piśācas and gandharvas, and the individual demons of the air (Vṛtra, Śuṣṇa, Śambara, Vala, Pipru, Namūci, Cumuri, Dhuni, Varcin, Aurṇavābha, Ahīśuva, Arbuda, Ilībiśa, Kuyava, Mṛgaya, Uraṇa, Paḍgṛbhi, Sṛbinda, Dṛbhīka, Rauhiṇa, Rudhikrās, Śvaśna, etc.).

But Malati Shendge practically goes berserk in identifying "non-Aryans" in the Rigveda. According to her, they include almost all the Vedic Gods except Indra and Viṣṇu (i.e. including Varuṇa, Mitra, Rudra, Sūrya, Savitṛ, Pūṣan, Bhaga, Aṁśa, etc.), all tribes whose names end in -u (including Ikṣvākus, Anus, Druhyus, Yadus, and Pūrus!!), most of the Vedic rishis themselves (including Gṛtsamada, the Saptaṛṣi, Mātariśvan, Aṅgiras, Atharvan, Atri, Kaṇva, Bhṛgu, Tanū Napāt, Apām Napāt, etc.!!). If this sounds incredible, note that three different "scholars", D. D. Kosambi and F.E. Pargiter besides Malati Shendge, classify all the Vedic rishis except the Viśvāmitras as "non-Aryans"! In all this, clearly linguistics has no role to play!

But it is not just half-baked Indian AIT scholars who go berserk in identifying "non-Aryans" in the Rigveda. Anyone who is able to wade through the muck in Michael Witzel's article "Aryan and non-Aryan names in Vedic India", which claims to be based on linguistic studies, will see how western academic scholars can run amok in a like manner. Suffice it to say, the "non-Aryan" names given by Witzel include, among countless others, Kuśika, Turvaśa, Anu, Yadu, Ikṣvāku and Pūru!

Witzel gets away with recklessly postulating not only Dravidian and Austric (Munda) linguistic identities for most of the words and names, but even confidently ascribes many of them to some mysterious hypothetical Language X and Language Y, of unknown (though of course non-Indo-European) linguistic affiliation, which he claims must have existed in India in the "pre-Aryan" past!

It requires only a genuinely honest disposition and genuine viveka-buddhi to examine this whole issue of "Aryan" vs. "non-Aryan" linguistic identity in the Rigveda dispassionately. As this article is only a preliminary step in this examination, I will try to keep it as brief as possible.

We will examine this issue from two points of view:

1. Dravidian words as an old substrate in the Rigveda.

2. Dravidian words as a new adstrate in the Rigveda.

I. Dravidian words as an old substrate in the Rigveda.

If the scenario postulated by the proponents is right, and the Rigveda was composed after the replacement of an earlier Dravidian population in the Harappan area with speakers of newly arrived Indo-European language speaking "Aryans", then we should find a prominent Dravidian substratum in the oldest parts of the Rigveda. However, as I have shown in detail in my books and blogs, there is absolutely no Dravidian "substratum" in the Old Rigveda (books 6,3,7,4 and 2, minus the Redacted Hymns). And the geographical names (names of Indian rivers, lakes, mountains, places and animals) in the text are all purely Indo-Aryan (= Indo-European). Even scholars like Witzel, who claim that a few geographical names and names of people in the Rigveda are "non-Aryan" cannot locate specifically Dravidian names in the Old Rigveda - which is the only thing we are concerned with in this article - we are not concerned here with the names and words alleged to be Munda or Language X or Language Y.

II. Dravidian words as a new adstrate in the Rigveda.

Are there any Dravidian words at all in the Rigveda? Seeing the geographical location of the Harappan civilization and the known geographical location of the Dravidian languages in the South, it would be rather difficult to see how such interaction could take place in those remote times. The presence of the Brahui language in Baluchistan was originally the most prominent factor cited in claiming that the Harappan area was originally inhabited by Dravidian speaking people, but now it has been accepted that the Brahui language actually migrated to Baluchistan from the South comparatively recently: as Witzel points out, “its presence has now been explained by a late migration that took place within this millennium (Elfenbeim 1987)” (WITZEL 2000a:§1). Likewise, Southworth, even while urging a Dravidian presence in the Harappan areas, admits that: “Hock (1975:87-8), among others, has noted that the current locations of Brahui, Kurux and Malto may be recent” (SOUTHWORTH 1995:272, fn22).

But there are two words in the Rigveda which, however unpalatable it may be to Sanskrit-centric opponents of the AIT, are very definitely linguistically Dravidian words:

1. The verbal root pūj- "to revere, worship, respect, honour (usually an idol, with flowers)", derived from the Dravidian, e.g. Tamil pū-, "flower", representing a form of worship totally unknown to the Vedic culture, and representing the religion of the South.

2. The word kāṇa, "one-eyed" or "cross-eyed", very clearly derived from the Dravidian, e.g. Tamil kaṇ, "eye".

Secondly, while the culture of the Old Rigveda was a very localized one centered around Haryana, the New Rigveda, which represents the Mature Harappan period, was not an isolated one, isolated from the rest of the world. It represented a technologically highly evolved civilization and had trade contacts with other civilizations to the west. The main known links of the Mature Harappans with western civilizations are those with the Mesopotamians or Babylonians. It is known that the Harappans traded with Mesopotamia: two words identified as Babylonian words are found in the Rigveda, both in book 8 which is the heart of the New Rigveda, and both have connections with traders. They are:

1. bekanāṭa (money-lender to traders, the Paṇi, who are referred to in the same verse) in VIII.66.10, and

2. manā (a unit of measure which is still used to this day) in VIII.78.2.

Harappan ships travelled not only to the ports of the Gulf, but probably into the Mediterranean Sea as well (see my blog article "The Elephant and the Proto-Indo-European Homeland"). Can it be possible that the areas of the south and east within India itself remained unknown to them, or remained out of the sphere of their contacts?

As we saw, Indian tradition squarely places the Harappan civilization in the areas of the Anus, the western and central Pūrus, and the (north-)western Yadus. But it recognizes the relationship of these people with the people and cultures of the other parts of India: the eastern Indo-European speaking people (the Ikṣvākus) as well as the Dravidian speaking people of the South and the Austric speaking people of the East, all of whom are classified as descendants of a mythical common ancestor, whom the Puranas call Manu.

So why is there no reference to these other people to the South or East?

As we saw, the only evidence in the New Rigveda of the rich trade relationship with Mesopotamia is in the shape of just two words, bekanāṭa and manā. So we cannot expect detailed accounts of the South and East in the hymns of the Rigveda in that early period. But surely there must have been some relationship, and this must have left some evidence in the text?

In reaction to the invasionist tendency to hunt for linguistic evidence of "pre-Aryan natives", there is usually a tendency on the part of Indians, as a reflex reaction, to reject the presence of non-Indo-Aryan, especially Dravidian, elements in the Rigveda. This is also correct in the sense that civilization and culture developed differently in different parts of the country, and the Rigvedic culture of the northwest in its initial stages (i.e. in the Old Rigveda, restricted to Haryana and its immediate environs) need not necessarily show elements from other parts of India. But what about in the period of the Mature Harappan = New Rigvedic civilization with its far-reaching trade contacts and relations?

Eleven years ago, in my 2008 book "The Rigveda and the Avesta - The Final Evidence", I noted the situation as follows: "Witzel’s first linguistic arguments, in section 11.5 (WITZEL 2005:344-346) have to do with what he calls 'Linguistic substrates'. This issue has been discussed in great detail in TALAGERI 2000:293-308 (and earlier in TALAGERI 1993:197-215). We will not repeat all the arguments and counter-arguments here, except for stressing the difference between 'substrate' words and 'adstrate' words (see section 6B of chapter 6 earlier in this book). In fact, let us accept that there may be some adstrate words of Dravidian or Austric origin in 'Indo-Aryan'― perhaps we protested a bit too much in our earlier books, due to the implications sought to be drawn from such alleged 'non-Indo-Aryan' words in Classical or even Vedic Sanskrit. The word kāṇa 'one-eyed', in the RV, for example, is obviously derived from the Dravidian word kaṇ 'eye'. Other, not implausible suggestions include the words daṇḍa and kuṭa". (p.292).

As a matter of fact, an examination of the actual Rigvedic data shows us that the Rigvedic culture did include some Dravidian elements. These elements were not residual elements of an original Dravidian Harappan civilization invaded and taken over by invading "Aryans", as often suggested, they are new elements imported from the Dravidian South. This is proved by the fact that:

1. They are not found in the Old Rigveda, and the geographical names in the Old Rigveda show that Dravidian speaking people never lived in the Harappan area before or during that period.

2. They are found as incidental elements in the New Rigveda, in a period which shows massive oversea trade contacts even with foreign places like Mesopotamia, and which is the period preceding the Avestan and Mitanni eras: the common elements with the Avesta and the Mitanni are abundantly found in the same texts and hymns which show these incidental Dravidian elements.

3. The Indian traditions and linguistics unambiguously and very clearly connect the people associated with these elements - actually Rigvedic rishis of Dravidian identity - with the South. And these people are not inimical to the Rigvedic culture but a part of it.

There seem to be at least two distinct streams of originally Dravidian speaking rishis:

1. As we saw, the Rigveda contains two important words - very important and common in later Sanskrit as well as in modern Indo-Aryan, but found only once each in the Rigveda - of undoubtedly Dravidian origin. These are:

a) The verbal root pūj-.

b) The word kāṇa.

These two words are found (both in the New Rigveda) as follows:

a) pūj- in VIII.17.12, attributed to Irimbiṭhi Kāṇva,

b) kāṇa in X.155.1, attributed to Śirimbiṭha Bhāradvāja.

It cannot be a coincidence that both the words are composed by two different rishis with such strikingly similar, unusual and non-Indo-Aryan names. The rishi-ascriptions in book 10 are very often garbled - in my 2000 book "The Rigveda - A historical Analysis", pp.25-26, I had written "Maṇḍala X is a very late Maṇḍala and stands out from the other nine Maṇḍalas in many respects. One of these is the general ambiguity in the ascriptions of the hymns to their composers. In respect of 44 hymns, and 2 other verses, it is virtually impossible to even identify the family of the composer" - and it is perfectly possible the composer of X.155 is also the same as the composer of VIII.17, i.e. Irimbiṭhi Kāṇva.

The name is clearly Dravidian: in fact, we still have a place in Kerala named Irimbiḷiyam: it is not impossible that this, or a nearby area, is the home-area of this Rigvedic composer - more than 4000 years old! Note that there are two more words in the same hymn, VIII.17, which have also been identified as Dravidian:

a) -khaṇḍ- in VIII.17.12,

b) kuṇḍa in VIII.17.13,

and, to crown it all, the word muni, found in only 4 hymns in the whole of the Rigveda, and referring to holy men from the non-Vedic areas of the East and South within India, is also found in the next verse: in VIII.17.14. That we should have so many indications in three consecutive verses is incredible but extremely significant.

Very clearly, this rishi Irimbiṭhi is a person from the Dravidian South who, like members of different religious orders in present-day India who are found in parts of India other than their area of origin, migrated to the busy cosmopolitan Mature Harappan = New Rigvedic civilization area from the South and subsequently became a Rigvedic rishi.

2. But Indian tradition has one more, and a very important, rishi who is unanimously and resoundingly associated, in the traditions of both the North and the South, with the South: Agastya. Puranic and Epic tradition tells us that Agastya migrated to the South and settled down there. But here is what Wikipedia has to say:

Agastya appears in numerous itihasas and puranas including the major Ramayana and Mahabharata.[5][6] He is one of the seven or eight most revered rishis in the Vedic texts,[7] and is revered as one of the Tamil Siddhar in the Shaivism tradition, who invented an early grammar of the Tamil language, Agattiyam, playing a pioneering role in the development of Tampraparniyan medicine and spirituality at Saiva centres in proto-era Sri Lanka and South India. He is also revered in the Puranic literature of Shaktism and Vaishnavism.[8] He is one of the Indian sages found in ancient sculpture and reliefs in Hindu temples of South Asia, and Southeast Asia such as in the early medieval era Shaiva temples on Java Indonesia. He is the principal figure and Guru in the ancient Javanese language text Agastyaparva, whose 11th century version survives.[9][10] Agastya is traditionally attributed to be the author of many Sanskrit texts such as the Agastya Gita found in Varaha Purana, Agastya Samhita found embedded in Skanda Purana, and the Dvaidha-Nirnaya Tantra text.[5] He is also referred to as Mana, Kalasaja, Kumbhaja, Kumbhayoni and Maitravaruni after his mythical origins." Even more to the point: "The etymological origin of Agastya has several theories. One theory states that the root […] is derived from a flowering tree called Agati gandiflora, which is endemic to the Indian subcontinent and is called Akatti in Tamil. This theory suggests that Agati evolved into Agastih, and favors Dravidian origins of the Vedic sage".

Therefore, despite later legends taking him from the North to the South, historically he was probably a Dravidian sage from the South who, or rather whose descendants, migrated northwards and became an important part of the Rigvedic priesthood, being recognized as a separate and independent family of Rigvedic rishis:

a) Tradition shows him to be different from the other Vedic rishis, more of a recluse and a forest-dweller, who prefers to stay away from the glamour and lucre of urban settings and royal patronage.

b) He is totally absent from the major part of the Rigveda, and his descendants have hymns only in the New Rigveda (mainly in book 1, where most of the Dravidian words are found) but tradition not only outside the Rigveda but even within the Rigveda (VII.33.10) consistently portrays him as an ancient Rishi contemporaneous to Vasiṣṭha.

c) The only reference to him, outside the New books 1 and 8 (I.117.11; 170.3; 179.6; 180.8; 184.5; VIII.5.26), is an incidental one in a Redacted Hymn, probably redacted by a descendant, in VII.33.10. And this hymn has a Dravidian word daṇḍa in the next verse VII.33.11.

3. The arrival of the Irimbiṭhas and Agastyas into the Rigvedic area in the Mature Harappan period seems to have brought in a small stream of Dravidian words, which stream became a small flood in later post-Vedic Classical Sanskrit.

The following is a list of other words allegedly of Dravidian origin, found in the Rigveda: vaila, kiyāmbu, vriś, cal-, bila, lip-, kaṭuka, kuṇḍṛṇācī (?), piṇḍa, mukha, kuṭa, kūṭa, khala, ulūkhala, kāṇuka, sīra, naḍa/naḷa, kulpha, ukha, kuṇāru, kulāya, lāṅgala. They are found only in the New Rigveda and in the Redacted Hymns, except for the occurrence of mukha in IV.39.6, kulāya in VII.50.1, and kulpha in VII.50.2. But note that Arnold (whom Hock cites as an expert on these matters) has classified both these hymns IV.39 and VII.50 also as Redacted Hymns on metrical grounds: so we do not find a single one of these Dravidian words in the Old Rigveda! The references (other than those already mentioned) are found as follows:

Redacted Hymns:

VI. 15.10; 47.23; 75.15.

III. 30.8.

IV. 57.4.

New Rigveda:

I. 11.5; 28.1,6; 29.6; 32.11; 33.1,3,3; 46.4; 97.6,7; 144.5; 162.2,13,15,19; 164.8; 174.10; 191.1,3,4.

VIII. 1.33; 43.10; 77.4.

X. 16.13; 48.7; 81.3; 85.34; 90.11; 97.6; 102.4.

Remember, these Dravidian rishis and words are found in the New Rigveda before 2000 BCE, nearly two millenniums before the Tamil Sangam Era! And also long before the first appearance of the Mitanni in Syria-Iraq and the Indo-European Iranians (Persians, Parthians, Medians) in Iran! So the Vedic-Dravidian relationship is an old and friendly one.

[A few other words, often gratuitously and unwarrantedly - and controversially - sought to be branded as Dravidian words, such as mayūra, phala, bala, gardabha, puṣpa, puṣkara, are rejected by most linguists as Dravidian words:

a) Witzel (although he continues to insist it is a "non-Aryan" word borrowed by Sanskrit, inspite of the fact that the name is a purely onomatopoeic name derived from the Sanskrit root mā) rejects mayūra as a Dravidian word in his article "Aryan and non-Aryan names in the Vedic India" (although this is particularly an article in which he goes berserk identifying as non-Aryan even words like Yadu and Pūru!!!).

b) Rendich Franco (in his "comparative Etymological Dictionary of Classical Indo-European languages") gives the PIE roots and cognate forms in Greek and Latin for the word phala, and likewise the PIE root for the words puṣpa and puṣkara.

c) Mallory and Adams (in their "Encyclopaedia of Indo-European culture") point out that bala is derived from PIE *belos, calling it "the strongest etymology containing the very rare PIE *b-", and give cognate forms in Greek, Latin and Old Church Slavic.

d) The word gardabha, though a late word found only in the New Rigveda and Redacted hymns, has a cognate form in Tocharian kercapo, in Central Asia, and in any case, the donkey is native to the northwest and not the south, and cannot be derived from the Tamil kazhutha under any circumstance].

In short, the Vedic-Dravidian relationship goes back to pre-2000 BCE times, and the reverence for Vedic culture in the oldest Dravidian Sangam literature has a long tradition behind it.

Santali glosses

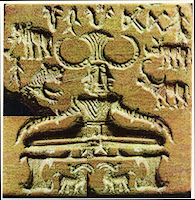

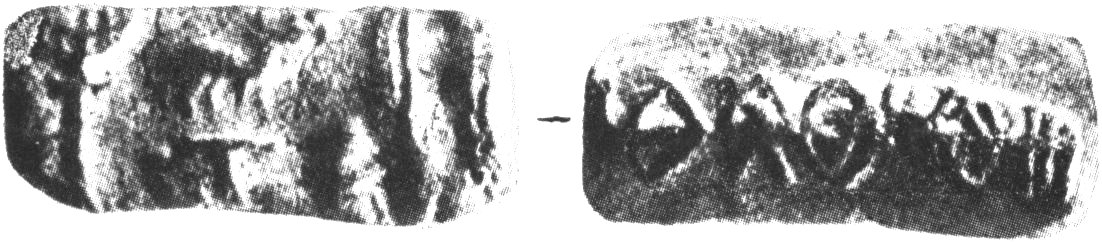

Santali glosses Material: tan steatite; Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050 Islamabad Museum, NMP 50.296 Mackay 1938: 335, pl. LXXXVII, 222 Hypertext: three faces, mũh 'face' Rebus mũhã̄ 'iron furnace output' kolom 'three' (faces) rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' *tiger's mane on face: The face is depicted with bristles of hair, representing a tiger’s mane. cūḍā, cūlā, cūliyā tiger’s mane (Pkt.)(CDIAL 4883) Rebus: cuḷḷai = potter’s kiln, furnace (Ta.); cūḷai furnace, kiln, funeral pile (Ta.); cuḷḷa potter’s furnace; cūḷa brick kiln (Ma.); cullī fireplace (Skt.); cullī, ullī id. (Pkt.)(CDIAL 4879; DEDR 2709). sulgao, salgao to light a fire; sen:gel, sokol fire (Santali.lex.) hollu, holu = fireplace (Kuwi); soḍu fireplace, stones set up as a fireplace (Mand.); ule furnace (Tu.)(DEDR 2857).

Material: tan steatite; Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050 Islamabad Museum, NMP 50.296 Mackay 1938: 335, pl. LXXXVII, 222 Hypertext: three faces, mũh 'face' Rebus mũhã̄ 'iron furnace output' kolom 'three' (faces) rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' *tiger's mane on face: The face is depicted with bristles of hair, representing a tiger’s mane. cūḍā, cūlā, cūliyā tiger’s mane (Pkt.)(CDIAL 4883) Rebus: cuḷḷai = potter’s kiln, furnace (Ta.); cūḷai furnace, kiln, funeral pile (Ta.); cuḷḷa potter’s furnace; cūḷa brick kiln (Ma.); cullī fireplace (Skt.); cullī, ullī id. (Pkt.)(CDIAL 4879; DEDR 2709). sulgao, salgao to light a fire; sen:gel, sokol fire (Santali.lex.) hollu, holu = fireplace (Kuwi); soḍu fireplace, stones set up as a fireplace (Mand.); ule furnace (Tu.)(DEDR 2857).

m0296 seal impression

m0296 seal impression

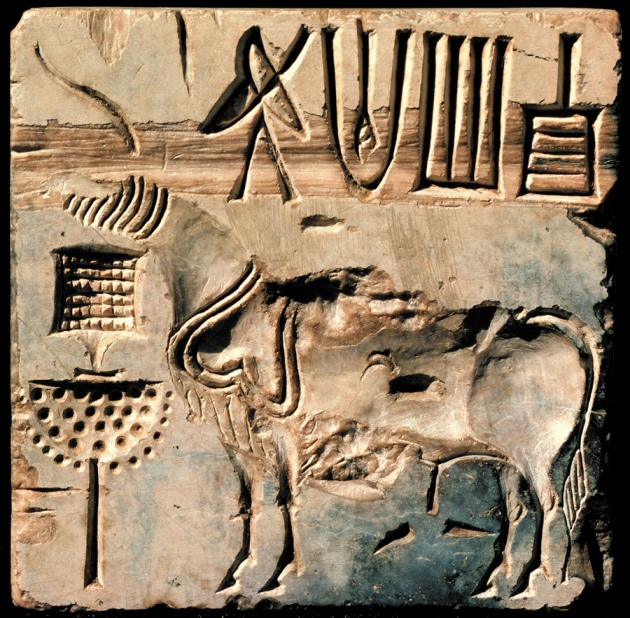

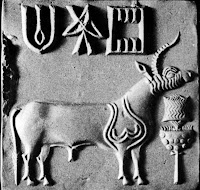

John Marshall wrote about this seal: "The animal most often represented on the seals is the apparently single-horned beast ... There is a possibility, I think, that the artist intended to represent one horn behind the other. In other animals, however, the two horns are shown quite distinctly. In some respects the body of this beast, which is always a male, resembles that of an

John Marshall wrote about this seal: "The animal most often represented on the seals is the apparently single-horned beast ... There is a possibility, I think, that the artist intended to represent one horn behind the other. In other animals, however, the two horns are shown quite distinctly. In some respects the body of this beast, which is always a male, resembles that of an

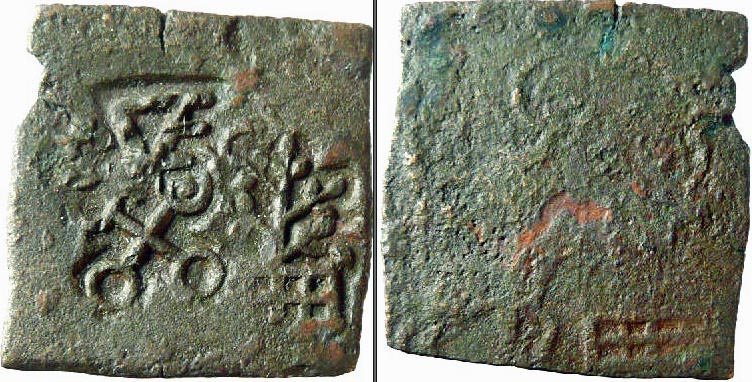

Inscribed Tablets. Pict-91 (Mahadevan)

Inscribed Tablets. Pict-91 (Mahadevan)

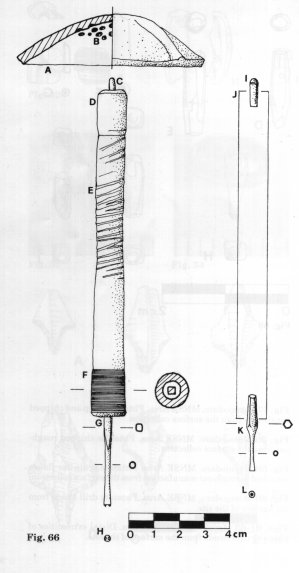

Components: top register: lathe with pointed gimlet in churning motion; bottom register: portable furnace/crucible with smoke emanating from the surface Carved ivory standard in the middle [From Richard H. Meadow and Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Harappa Excavations 1993: the city wall and inscribed materials, in: South Asian Archaeology ; Fig. 40.11, p. 467. Harappa 1990 and 1993: representations of 'standard'; 40.11a: H90-1687/3103-1: faience token; 40.11bH93-2092/5029-1: carved ivory standard fragment (split in half, made on a lathe and was probably cylindrical in shape; note the incisions with a circle motif while a broken spot on the lower portion indicates where the stand shaft would have been (found in the area of the 'Mughal Sarai' located to the south of Mound E across the Old Lahore-Multan Road); 40.11c H93-2051/3808-2:faience token)

Components: top register: lathe with pointed gimlet in churning motion; bottom register: portable furnace/crucible with smoke emanating from the surface Carved ivory standard in the middle [From Richard H. Meadow and Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Harappa Excavations 1993: the city wall and inscribed materials, in: South Asian Archaeology ; Fig. 40.11, p. 467. Harappa 1990 and 1993: representations of 'standard'; 40.11a: H90-1687/3103-1: faience token; 40.11bH93-2092/5029-1: carved ivory standard fragment (split in half, made on a lathe and was probably cylindrical in shape; note the incisions with a circle motif while a broken spot on the lower portion indicates where the stand shaft would have been (found in the area of the 'Mughal Sarai' located to the south of Mound E across the Old Lahore-Multan Road); 40.11c H93-2051/3808-2:faience token)

.png)

The Indian Express tries to Explain that why ‘Urdu’ language is an Indian and not a foreign language. (Illustration by Suvajit Dey)

The Indian Express tries to Explain that why ‘Urdu’ language is an Indian and not a foreign language. (Illustration by Suvajit Dey)