Note: The similarity of some symbols between Rongorongo and Indus Script has fascinated many enquirers including the Sherlock Holmes of Neuroscience, Prof. Viliyanur Ramachandran.

See: https://www.academia.edu/36427324/Corpus_of_Rongorongo_texts_and_a_compendium_of_views_on_links_with_Indus_Script

Excerpts: Corpus of Rongorongo texts and a compendium of views on links with Indus Script

Prologue

At the outset, the possibility of survival of Indus Script Cipher in the Rongorongo script cannot be ruled out, considering the following:

1. Indus Script hypertexts continue to be used on tens of thousands of punch-marked and cast coins of mints (dated from ca. 6th cent. BCE) from Taxila to Anurdhapura.

2. The position analyses of 'sign clusters', 'pictorial motif clusters', the use of 'numeral signs' as words, the close connection between 'pictorial motifs' and 'signs' as seen on over 200 copper plate inscriptions of Indus Script point the writing system as rebus renderings of metalwork catalogues detailing resources such as minerals, metals, alloys, cire perdue casting, ingot casting, casting of metalware in moulds, work with smelters, furnaces, smithy/forge.

3. The Kabul mss. with a string of over 200 signs seems to be consistent with the 'sign' strings on Indus Script inscriptions, pointing to the mss as a catalogue of catalogues.

The possibility of Rongorongo writing system with a similar structure comparable to the Kabul mss, form, and function cannot be ruled out given the apparent orthographic parallels between 'rongorongo' hieroglyphs and 'Indus Script Hypertexts'. As suggested by Mayank Vahia, a good start will be to analyze the Rongorongo Script Corpus to identify 'hieroglyph' clusters and draw a venn diagram of relationships, if any, with preceding and succeeding 'hieroglyph' clusters. Such a cluster analysis may yield some semantic pointers, assuming that there is underlying language words may be rebus signifiers of 'hypertexts' and 'meanings' as was shown for Indus Script Corpora of now over 8000 inscriptions.

The toughest part of the research effort will be to authenticate the orthography of each 'hieroglyph' of Rongorongo script, in comparison with the Indus Script hypertexts to indicate possible identical deployment of comparable 'hieroglyphs/hypertexts'. (Note: An example of a hypertext is a 'fish' hieroglyph superscripted with an inverted V or ^ glyph. This ^ glyph signifies in Indus Script a lid of a pot read as ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article' PLUS aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda).

I agree with Dr.V. Ramachandran. The Rongorongo script should be investigated by researchers of civilization studies.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Centre

The Rongorongo of Easter Island

The Indus Valley Hypothesis

________________________________________

"This hypothesis is due to Guillaume de Hevesy, a Hungarian living in Paris, who dabbled in comparative linguistics, and who noticed some resemblance between the Indus Valley seal inscriptions and the rongorongo. Hevesy jumped to the conclusion: the rongorongo originated in the Indus Valley civilization. The hypothesis, first published in 1932, was generally well received, and caused such a flurry of interest that as late as 1939 the Journal of the Polynesian Society would publish, under the title "The Panis of the Rig Veda and Script of Mohenjo Daro and Easter Island," a piece against which A. Carroll's decipherments are a model of sober, restrained scholarship."

http://kohaumotu.org/rongorongo_org/theories/indus/intro.html

I have no clue as to the origin of Thodas of Nilgiris. But, I have found dramatic links with Sumerian mudhif-s and the Toda huts.So, we can posit that Toda are the descendants of children of Sarasvati Civilization who had contacts with Sumeria. The comparison between Toda hut and Sumerian mudhif is simply astonishing.

Mirror:

https://tinyurl.com/y85n5drm

Mudhif and three reed banners

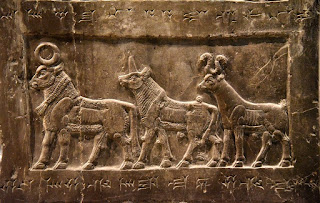

Figure 15.1. Sealing with representations of reed structures with cows, calves, lambs, and ringed

bundle “standards” of Inana (drawing by Diane Gurney. After Hamilton 1967, fig. 1)

Three rings on reed posts are three dotted circles: dāya 'dotted circle' on dhā̆vaḍ priest of 'iron-smelters', signifies tadbhava from Rigveda dhāī ''a strand (Sindhi) (hence, dotted circle shoring cross section of a thread through a perorated bead);rebus: dhāū, dhāv ʻa partic. soft red ores'. dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā]Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)

![]() Cylinder seal impression, Uruk period, Uruk?, 3500-2900 BCE. Note a load of livestock (upper), overlapping greatly (weird representation), and standard 'mudhif' reed house form common to S. Iraq (lower).

Cylinder seal impression, Uruk period, Uruk?, 3500-2900 BCE. Note a load of livestock (upper), overlapping greatly (weird representation), and standard 'mudhif' reed house form common to S. Iraq (lower).

![Image result for bharatkalyan97 mudhif]() A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

Figure 15.1. Sealing with representations of reed structures with cows, calves, lambs, and ringed

bundle “standards” of Inana (drawing by Diane Gurney. After Hamilton 1967, fig. 1)

Three rings on reed posts are three dotted circles: dāya 'dotted circle' on dhā̆vaḍ priest of 'iron-smelters', signifies tadbhava from Rigveda dhāī ''a strand (Sindhi) (hence, dotted circle shoring cross section of a thread through a perorated bead);rebus: dhāū, dhāv ʻa partic. soft red ores'. dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā]Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)

Cylinder seal impression, Uruk period, Uruk?, 3500-2900 BCE. Note a load of livestock (upper), overlapping greatly (weird representation), and standard 'mudhif' reed house form common to S. Iraq (lower).

Cylinder seal impression, Uruk period, Uruk?, 3500-2900 BCE. Note a load of livestock (upper), overlapping greatly (weird representation), and standard 'mudhif' reed house form common to S. Iraq (lower).Cattle Byres c.3200-3000 B.C. Late Uruk-Jemdet Nasr period. Magnesite. Cylinder seal. In the lower field of this seal appear three reed cattle byres. Each byre is surmounted by three reed pillars topped by rings, a motif that has been suggested as symbolizing a male god, perhaps Dumuzi. Within the huts calves or vessels appear alternately; from the sides come calves that drink out of a vessel between them. Above each pair of animals another small calf appears. A herd of enormous cattle moves in the upper field. Cattle and cattle byres in Southern Mesopotamia, c. 3500 BCE. Drawing of an impression from a Uruk period cylinder seal. (After Moorey, PRS, 1999, Ancient mesopotamian materials and industries: the archaeological evidence, Eisenbrauns.)

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia....

Mudhif is a cattle pen.

![Image result for bharatkalyan97 mudhif]() 284 x 190 mm. Close up view of a Toda hut, with figures seated on the stone wall in front of the building. Photograph taken circa 1875-1880, numbered 37 elsewhere. Royal Commonwealth Society Library. Cambridge University Library. University of Cambridge.

284 x 190 mm. Close up view of a Toda hut, with figures seated on the stone wall in front of the building. Photograph taken circa 1875-1880, numbered 37 elsewhere. Royal Commonwealth Society Library. Cambridge University Library. University of Cambridge.

![]() The Toda mund, from, Richard Barron, 1837, "View in India, chiefly among the Nilgiri Hills'. Oil on canvas. The architecture of Iraqi mudhif and Toda mund -- of Indian linguistic area -- is comparable.

The Toda mund, from, Richard Barron, 1837, "View in India, chiefly among the Nilgiri Hills'. Oil on canvas. The architecture of Iraqi mudhif and Toda mund -- of Indian linguistic area -- is comparable.

![]()

![]() Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.

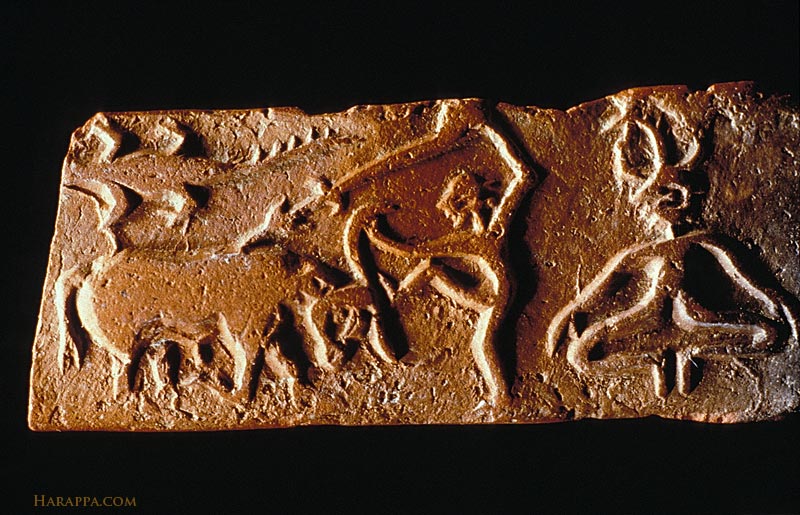

![]() Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.

Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.

कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa, 'cattlepen', Mesopotamia Rebus: kundaṇa 'fine gold'

One-horned young bulls and calves are shown emerging out of कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa cattlepens heralded by Inana standards atop the mudhifs. The Inana standards are reeds with three rings. The reed standard is the same which is signified on Warka vase c. 3200–3000 BCE.

Sumerian mudhif (reedhouse) http://www.laputanlogic.com/articles/2004/01/24-0001.html

and modern mudhif structure (Iraq) compare with the Toda mund (sacred hut)

गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A roundish stone or pebble. गोदा [ gōdā ] m A circular brand or mark made by actual cautery (Marathi)गोटा [ gōṭā ] m A roundish stone or pebble. 2 A marble (of stone, lac, wood &c.) 2 A marble. 3 A large lifting stone. Used in trials of strength among the Athletæ. 4 A stone in temples described at length underउचला 5 fig. A term for a round, fleshy, well-filled body. 6 A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe. गोटुळा or गोटोळा [ gōṭuḷā or gōṭōḷā ] a (गोटा) Spherical or spheroidal, pebble-form. (Marathi)

Rebus: krvṛi f. ‘granary (WPah.); kuṛī, kuṛo house, building’(Ku.)(CDIAL 3232) कोठी [ kōṭhī ] f (कोष्ट S) A granary, garner, storehouse, warehouse, treasury, factory, bank. (Marathi)

कोठी The grain and provisions (as of an army); the commissariatsupplies. Ex. लशकराची कोठी चालली-उतरली- आली-लुटली. कोठ्या [ kōṭhyā ] कोठा [ kōṭhā ] m (कोष्ट S) A large granary, store-room, warehouse, water-reservoir &c. 2 The stomach. 3 The chamber of a gun, of water-pipes &c. 4 A bird's nest. 5 A cattle-shed. 6 The chamber or cell of a hunḍí in which is set down in figures the amount. कोठारें [ kōṭhārēṃ ] n A storehouse gen (Marathi)

The Uruk trough. From Uruk (Warka), southern Iraq. Late Prehistoric period, about 3300-3000 BC

A cult object in the Temple of Inanna?

This trough was found at Uruk, the largest city so far known in southern Mesopotamia in the late prehistoric period (3300-3000 BC). The carving on the side shows a procession of sheep approaching a reed hut (of a type still found in southern Iraq) and two lambs emerging. The decoration is only visible if the trough is raised above the level at which it could be conveniently used, suggesting that it was probably a cult object, rather than of practical use. It may have been a cult object in the Temple of Inana (Ishtar), the Sumerian goddess of love and fertility; a bundle of reeds (Inanna's symbol) can be seen projecting from the hut and at the edges of the scene. Later documents make it clear that Inanna was the supreme goddess of Uruk. Many finely-modelled representations of animals and humans made of clay and stone have been found in what were once enormous buildings in the centre of Uruk, which were probably temples. Cylinder seals of the period also depict sheep, cattle, processions of people and possibly rituals. Part of the right-hand scene is cast from the original fragment now in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

J. Black and A. Green, Gods, demons and symbols of -1 (London, The British Museum Press, 1992)

H.W.F. Saggs, Babylonians (London, The British Museum Press, 1995)

D. Collon, Ancient Near Eastern art (London, The British Museum Press, 1995)

H. Frankfort, The art and architecture of th (London, Pelican, 1970)

P.P. Delougaz, 'Animals emerging from a hut', Journal of Near Eastern Stud-1, 27 (1968), pp. 186-7 http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/t/the_uruk_trough.aspx

Life on the edge of the marshes (Edward Ochsenschlaer, 1998)Sumerian mudhif facade, with uncut reed fonds and sheep entering, carved into a gypsum trough from Uruk, c. 3200 BCE (British Museum WA 12000). Photo source.

Fig. 5B. Carved gypsum trough from Uruk. Two lambs exit a reed structure identifical to the present-day mudhif on this ceremonial trough from the site of Uruk in northern Iraq. Neither the leaves or plumes have been removed from the reds which are tied together to form the arch. As a result, the crossed-over, feathered reeds create a decorative pattern along the length of the roof, a style more often seen in modern animal shelters built by the Mi'dan. Dating to ca. 3000 BCE, the trough documents the extraordinry length of time, such arched reed buildings have been in use. (The British Museum BCA 120000, acg. 2F2077)

End of the Uruk trough. Length: 96.520 cm Width: 35.560 cm Height: 15.240 cm

284 x 190 mm. Close up view of a Toda hut, with figures seated on the stone wall in front of the building. Photograph taken circa 1875-1880, numbered 37 elsewhere. Royal Commonwealth Society Library. Cambridge University Library. University of Cambridge.

284 x 190 mm. Close up view of a Toda hut, with figures seated on the stone wall in front of the building. Photograph taken circa 1875-1880, numbered 37 elsewhere. Royal Commonwealth Society Library. Cambridge University Library. University of Cambridge. The Toda mund, from, Richard Barron, 1837, "View in India, chiefly among the Nilgiri Hills'. Oil on canvas. The architecture of Iraqi mudhif and Toda mund -- of Indian linguistic area -- is comparable.

The Toda mund, from, Richard Barron, 1837, "View in India, chiefly among the Nilgiri Hills'. Oil on canvas. The architecture of Iraqi mudhif and Toda mund -- of Indian linguistic area -- is comparable.A Toda temple in Muthunadu Mund near Ooty, India.Toda people

|

The hut of a Toda Tribe of Nilgiris, India. Note the decoration of the front wall, and the very small door.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.m0702 Text 2206 showing Sign 39, a glyph which compares with the Sumerian mudhif structure.

- ढालकाठी [ ḍhālakāṭhī ] f ढालखांब m A flagstaff; esp.the pole for a grand flag or standard.

ढाल [ ḍhāla ] 'flagstaff' rebus: dhalako 'a large metal ingot (Gujarati) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati). The mudhif flag on the inscription is read rebus: xolā 'tail' Rebus: kole.l 'smithy, temple'. The structure is goṭ 'catttle-pen' (Santali) rebus: koṭṭhaka 'warehouse'. [kōṣṭhāgāra n. ʻ storeroom, store ʼ Mn. [kṓṣṭha -- 2, agāra -- ]Pa. koṭṭhāgāra -- n. ʻ storehouse, granary ʼ; Pk. koṭṭhāgāra -- , koṭṭhāra -- n. ʻ storehouse ʼ; K. kuṭhār m. ʻ wooden granary ʼ, WPah. bhal. kóṭhār m.; A. B. kuṭharī ʻ apartment ʼ, Or. koṭhari; Aw. lakh. koṭhārʻ zemindar's residence ʼ; H. kuṭhiyār ʻ granary ʼ; G. koṭhār m. ʻ granary, storehouse ʼ, koṭhāriyũ n. ʻ small do. ʼ; M. koṭhār n., koṭhārẽ n. ʻ large granary ʼ, -- °rī f. ʻ small one ʼ; Si. koṭāra ʻ granary, store ʼ.WPah.kṭg. kəṭhāˊr, kc. kuṭhār m. ʻ granary, storeroom ʼ, J. kuṭhār, kṭhār m.; -- Md. kořāru ʻ storehouse ʼ ← Ind.(CDIAL 3550)] Rebus: kuṭhāru 'armourer,

Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.

Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.Text 1330 (appears with Zebu glyph) showing Sign 39. Pictorial motif: Zebu (Bos indicus) This sign is comparable to the cattle byre of Southern Mesopotamia dated to c. 3000 BCE. Rebus Meluhha readings of gthe inscription are from r. to l.: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS goṭ 'cattle-pen' rebus: koṭṭhāra 'warehouse' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' PLUS aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS kuṭika— 'bent' MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) PLUS kanka, karṇika कर्णिक 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale'. Read together with the fieldsymbol of the zebu,the message is: magnetite ore smithy, forge, warehouse, iron alloy metal, bronze merchandise (ready for loading as cargo).

goṭ = the place where cattle are collected at mid-day (Santali); goṭh (Brj.)(CDIAL 4336). goṣṭha (Skt.); cattle-shed (Or.) koḍ = a cow-pen; a cattlepen; a byre (G.) कोठी cattle-shed (Marathi) कोंडी [ kōṇḍī ] A pen or fold for cattle. गोठी [ gōṭhī ] f C (Dim. of गोठा) A pen or fold for calves. (Marathi)

koṭṭhaka1 (nt.) "a kind of koṭṭha," the stronghold over a gateway, used as a store -- room for various things, a chamber, treasury, granary Vin ii.153, 210; for the purpose of keeping water in it Vin ii.121=142; 220; treasury J i.230; ii.168; -- store -- room J ii.246; koṭthake pāturahosi appeared at the gateway, i. e. arrived at the mansion Vin i.291.; -- udaka -- k a bath -- room, bath cabinet Vin i.205 (cp. Bdhgh's expln at Vin. Texts ii.57); so also nahāna -- k˚ and piṭṭhi -- k˚, bath -- room behind a hermitage J iii.71; DhA ii.19; a gateway, Vin ii.77; usually in cpd. dvāra -- k˚ "door cavity," i. e. room over the gate: gharaŋ satta -- dvāra -- koṭṭhakapaṭimaṇḍitaŋ "a mansion adorned with seven gateways" J i.227=230, 290; VvA 322. dvāra -- koṭṭhakesu āsanāni paṭṭhapenti "they spread mats in the gateways" VvA 6; esp. with bahi: bahi -- dvārakoṭṭhakā nikkhāmetvā "leading him out in front of the gateway" A iv.206; ˚e thiṭa or nisinna standing or sitting in front of the gateway S i.77; M i.161, 382; A iii.30. -- bala -- k. a line of infantry J i.179. -- koṭṭhaka -- kamma or the occupation connected with a storehouse (or bathroom?) is mentioned as an example of a low occupation at Vin iv.6; Kern, Toev. s. v. "someone who sweeps away dirt." (Pali)

कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa, 'cattlepen', Mesopotamia Rebus: kundaṇa 'fine gold'

One-horned young bulls and calves are shown emerging out of कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa cattlepens heralded by Inana standards atop the mudhifs. The Inana standards are reeds with three rings. The reed standard is the same which is signified on Warka vase c. 3200–3000 BCE.

The Rongorongo of Easter Island

By Anonymous

| Awards | Last updated 2005/02/27 | your questions answered |

| Resources Site Index Hieroglyphs Concordance Traditions Dictionary Tablets Tablet A Tablet B Tablet C Tablet D Tablet E Tablet F Tablet G Tablet H Object I Object J Tablet K Object L Tablet M Tablet N Tablet O Tablet P Tablet Q Tablet R Tablet S Tablet T Tablet U Tablet V Tablet W Object X Object Y Tablet Z |

| The Tablets: Text, Decipherment, Historical Background | ||

Overview

The Main Tablets

| Deciphering the rongorongo

Decipherments

| Early Visitors' Reports Recommended Links (Each link opens a new window)

Miscellanea

|

| Your questions and comments answered | Why www.rongorongo.org? |

Links to some portals/websites:

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 22 | 25 | 27AB | 28 | 34 | 38 | 41 | 44 | 46 | 47 | 50 | 52 | 53 |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 66 | 67 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 74 | 76 | 91 |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 95 | 99 | 200 | 240 | 280 | 380 | 400 | 530 | 660 | 700 | 720 | 730 | 901 |

| This basic inventory of rongorongo, proposed by Pozdniakov & Pozdniakov (2007), accounts for 99.7% of the intact texts, except for the idiosyncratic Staff. Glyph 901  was first proposed by Pozdniakov.[69] The inverted variant 27b in Barthel's glyph 27 ( was first proposed by Pozdniakov.[69] The inverted variant 27b in Barthel's glyph 27 ( ) appears to be a distinct glyph. Although 99 ) appears to be a distinct glyph. Although 99  looks like a ligature of 95 looks like a ligature of 95  and 14 and 14  , statistically it behaves like a separate glyph, similar to how Latin Q and R do not behave as ligatures of O and P with an extra stroke, but as separate letters.[70] ... , statistically it behaves like a separate glyph, similar to how Latin Q and R do not behave as ligatures of O and P with an extra stroke, but as separate letters.[70] ...The shared repetitive nature of the phrasing of the texts, apart from Gv and I, suggests to Pozdniakov that they are not integral texts, and cannot contain the varied contents which would be expected for history or mythology.[71] In the following table of characters in the Pozdniakov & Pozdniakov inventory, ordered by descending frequency, the first two rows of 26 characters account for 86% of the entire corpus.[72] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decipherment_of_rongorongo | ||||||||||||

JOURNAL ARTICLE

THE EASTER ISLAND SCRIPT AND THE MIDDLE-INDUS SEALS

J. Imbelloni

The Journal of the Polynesian Society

Vol. 48, No. 1(189) (March, 1939), pp. 60-69 (10 pages)

Published by: The Polynesian Society

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2070275

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Illustration by Glenn Harvey

Illustration by Glenn Harvey Review of The Curse of Gandhari by Aditi Banerjee

Review of The Curse of Gandhari by Aditi Banerjee

h95 tablet.

h95 tablet.

Ś

Ś

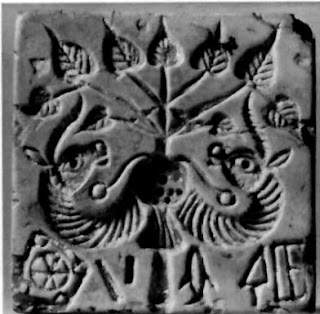

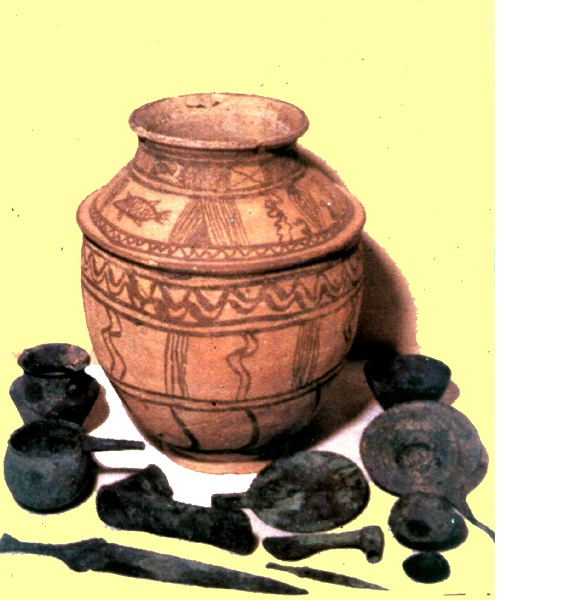

Combined animal heads on a bovine body. Mohenjo-daro seal.

Combined animal heads on a bovine body. Mohenjo-daro seal.

Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate.

Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate. Unicorn read rebus in Meluhha as खोंड khōṇḍa singin 'young bull, horned'.

Unicorn read rebus in Meluhha as खोंड khōṇḍa singin 'young bull, horned'. Wicker-basket-shaped crown with Indus Script hieroglyphs of

Wicker-basket-shaped crown with Indus Script hieroglyphs of

Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150)

Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150)  Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.

Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.