Hieroglyphs in Meluhha:

1. bicha, 'scorpion'

2. mẽḍhā ʻcrook, hook',

3. dāṭu 'cross'

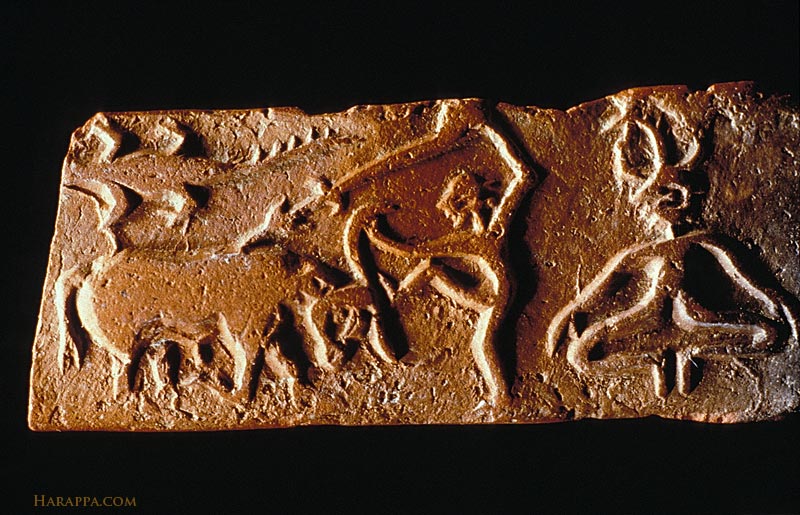

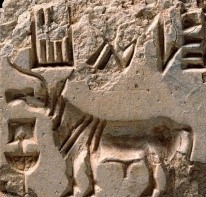

4. kanka, karNaka, 'rim of jar'![]() The hypertext inscription composed of four hieroglyph multiplexes PLUS young-bull PLUS standard device (lathe+portable brazier) on Mohenjo-daro seal m-857 signifies: 1. meṛed-bica = 'iron (hematite) stone ore' 2. dhatu khanda karNI 'supercargo of mineral ore, equipment', scribed. (The one-horned young bull PLUS standard device is deciphered as: kondh 'young bull' Rebus: kondh 'turner'; koD 'horn' Rebus: koD 'workshop'; sangaDa 'lathe' Rebus: sangAta 'collection of materials, i.e. consignment or boat load. Rebus: samgraha, samgaha 'arranger, manager'.

The hypertext inscription composed of four hieroglyph multiplexes PLUS young-bull PLUS standard device (lathe+portable brazier) on Mohenjo-daro seal m-857 signifies: 1. meṛed-bica = 'iron (hematite) stone ore' 2. dhatu khanda karNI 'supercargo of mineral ore, equipment', scribed. (The one-horned young bull PLUS standard device is deciphered as: kondh 'young bull' Rebus: kondh 'turner'; koD 'horn' Rebus: koD 'workshop'; sangaDa 'lathe' Rebus: sangAta 'collection of materials, i.e. consignment or boat load. Rebus: samgraha, samgaha 'arranger, manager'.

Rebus readings in Meluhha: haematite iron ore supercargo

1. bica 'haematite, ferrite ore'

2. mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Santali.Mu.Ho.) PLUS bica; that is, the compound phrase meṛed-bica = 'iron (hematite) stone ore' (Santali)

3. dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773).

4. kaṇḍa kanka 'smelting furnace account (scribe), karṇīka, 'account, scribe', karṇī 'supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.'

The four hieroglyph multiplex on Mohenjo-daro seal m-857 signifies: 1. meṛed-bica = 'iron (hematite).

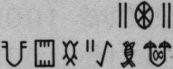

Text 1087 Mohenjo-daro seal m0038

Meluhha rebus readings from l. to r.

Segment 1: As on m857 seal.

![]() Rebus readings in Meluhha: haematite iron ore supercargo

Rebus readings in Meluhha: haematite iron ore supercargo

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'

dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

ayo ‘fish’ rebus: aya ‘iron', ayas, 'alloy metal’ khambhaṛā ‘fish fin’ rebus: kammaTa ‘mint, coiner, coinage’

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS aḍaren, ḍaren 'lid, cover'

rebus: aduru 'native, unsmelted metal'

sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

kamāṭhiyo 'archer' rebus: kammaṭa 'coiner, mint, coinage'

Reading 1: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' Reading 2: kuThAru 'treasury' rebus: kuThAru'armourer'

dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'.

Pictorial motifs (Field symbols) on m857:

1.koDiya ‘rings on neck’, ‘young bull’ koD ‘horn’ rebus 1: koṭiya 'dhow, seafaring vessel' khōṇḍī 'pannier sack' खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) koD 'workshop' khOnda ‘young bull’ rebus 2: kOnda ‘lapidary, engraver’ rebus 3: kundAr ‘turner’ कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. खोट [khōṭa] Alloyed--a metal kunda 'finegold' singhin 'horned' rebus: singi 'ornament gold'.

2. sangaDa ‘lathe, portable brazier’ sanghaṭṭana ‘bracelet’ rebus 1: sanghāṭa ‘raft’ sAngaDa ‘catamaran, double-canoe’rebus čaṇṇāḍam (Tu. ജംഗാല, Port. Jangada). Ferryboat, junction of 2 boats, also rafts. 2 jangaḍia 'military guard accompanying treasure into the treasury' ചങ്ങാതം čaṇṇāδam (Tdbh.; സംഘാതം) 1. Convoy, guard; responsible Nāyar guide through foreign territories. rebus 3: जाकड़ ja:kaṛ जांगड़ jāngāḍ ‘entrustment note’ जखडणें tying up (as a beast to a stake) rebus 4: sanghāṭa ‘accumulation, collection’ rebus 5. sangaDa ‘portable furnace, brazier’ rebus 6: sanghAta ‘adamantine glue‘ rebus 7: sangara ‘fortification’ rebus 8: sangara ‘proclamation’ 9. samgraha, samgaha 'arranger, manager'.

Thus, the inscription reads: (from) Fortification manager workshop

haematite iron ore supercargo

Metal castings (alloy metal)

(Products) of mint, coiner, coinage

Unsmelted metal

Smithy, forge workshop (products) of mint, coiner, coinage

Metal castings (from armoury)

Indus tablet M-1475 with barely legible inscription (from right to left): Mohenjodaro tablet. m-1475 The second segment (l. to r.) is the message: haematite iron ore supercargo

Obverse

Hieroglyph: tiger:kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron,blacksmith' PLUS pattar 'trough' rebus: pattar'goldsmith, guild'

The first segment (l. to r.):

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS gaNDa 'four' rebus: kaNDa 'implements, fire-altar'

kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

kuṭi 'curve; rebus: कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl (8 parts copper, 2 parts tin), thus, bronze PLUS खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or ʻswordʼ (Prakritam) rebus: khāṇḍa, khaṇḍa'implements, pots & pans, weapons'.

Together, the message in two components is: smithy,forge implements, bronze implements haematite iron ore supercargo (of) kol pattar, 'ironsmith guild'.

Indus seal M-626 with inscription:

Indus seal H-61 with inscription: ![]() Text 4118

Text 4118

Pictorial motifs (Field symbols) on h61:

1.koDiya ‘rings on neck’, ‘young bull’ koD ‘horn’ rebus 1: koṭiya 'dhow, seafaring vessel' khōṇḍī 'pannier sack' खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) koD 'workshop' khOnda ‘young bull’ rebus 2: kOnda ‘lapidary, engraver’ rebus 3: kundAr ‘turner’ कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. खोट [khōṭa] Alloyed--a metal

2. sangaDa ‘lathe, portable brazier’ sanghaṭṭana ‘bracelet’ rebus 1: sanghāṭa ‘raft’ sAngaDa ‘catamaran, double-canoe’rebus čaṇṇāḍam (Tu. ജംഗാല, Port. Jangada). Ferryboat, junction of 2 boats, also rafts. 2 jangaḍia 'military guard accompanying treasure into the treasury' ചങ്ങാതം čaṇṇāδam (Tdbh.; സംഘാതം) 1. Convoy, guard; responsible Nāyar guide through foreign territories. rebus 3: जाकड़ ja:kaṛ जांगड़ jāngāḍ ‘entrustment note’ जखडणें tying up (as a beast to a stake) rebus 4: sanghāṭa ‘accumulation, collection’ rebus 5. sangaDa ‘portable furnace, brazier’ rebus 6: sanghAta ‘adamantine glue‘ rebus 7: sangara ‘fortification’ rebus 8: sangara ‘proclamation’ 9. samgraha, samgaha 'arranger, manager'.

Meluhha rebus readings from l. to r.

Segment 1: As on m857 seal.

![]() Rebus readings in Meluhha: haematite iron ore supercargo

Rebus readings in Meluhha: haematite iron ore supercargo

Segment 2: खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or ʻswordʼ (Prakritam) rebus: khāṇḍa, khaṇḍa 'implements, pots & pans, weapons'

Segment 3:

kuṭi 'curve; rebus: कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl (8 parts copper, 2 parts tin), thus, bronze PLUS खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or ʻswordʼ (Prakritam) rebus: khāṇḍa, khaṇḍa 'implements, pots & pans, weapons'.

Segment 4: చీమ [ cīma ] cīma. [Tel.] n. An ant rebus: ċiməkára ʻblacksmith, coppersmith'

PLUS hieroglyph śrētrī 'ladder' rebus: śrēṣṭhin 'distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ![]()

Sign 186 *śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ. [Cf. śrētr̥ -- ʻ one who has recourse to ʼ MBh. -- See śrití -- . -- √śri]Ash. ċeitr ʻ ladder ʼ (< *ċaitr -- dissim. from ċraitr -- ?).(CDIAL 12720)*śrēṣṭrī2 ʻ line, ladder ʼ. [For mng. ʻ line ʼ conn. with √śriṣ2 cf. śrḗṇi -- ~ √śri. -- See śrití -- . -- √śriṣ2]Pk. sēḍhĭ̄ -- f. ʻ line, row ʼ (cf. pasēḍhi -- f. ʻ id. ʼ. -- < EMIA. *sēṭhī -- sanskritized as śrēḍhī -- , śrēṭī -- , śrēḍī<-> (Col.), śrēdhī -- (W.) f. ʻ a partic. progression of arithmetical figures ʼ); K. hēr, dat. °ri f. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 12724) Rebus: śrḗṣṭha ʻ most splendid, best ʼ RV. [śrīˊ -- ]Pa. seṭṭha -- ʻ best ʼ, Aś.shah. man. sreṭha -- , gir. sesṭa -- , kāl. seṭha -- , Dhp. śeṭha -- , Pk. seṭṭha -- , siṭṭha -- ; N. seṭh ʻ great, noble, superior ʼ; Or. seṭha ʻ chief, principal ʼ; Si. seṭa, °ṭu ʻ noble, excellent ʼ. śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ]Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ, seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M. śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2?)(CDIAL 12725, 12726)

The inscription is the metalwork catalogue message:

(from) Fortification manager workshop

haematite iron ore supercargo

implements, pots & pans

bronze implements, pots & pans

foreman of coppersmith guild.

Detail from seal H-12 showing inscription over unicorn: Meluhha rebus readings from l. to r.

Pictorial motifs (Field symbols) on h12:

1.koDiya ‘rings on neck’, ‘young bull’ koD ‘horn’ rebus 1: koṭiya 'dhow, seafaring vessel' khōṇḍī 'pannier sack' खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) koD 'workshop' khOnda ‘young bull’ rebus 2: kOnda ‘lapidary, engraver’ rebus 3: kundAr ‘turner’ कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. खोट [khōṭa] Alloyed--a metal

2. sangaDa ‘lathe, portable brazier’ sanghaṭṭana ‘bracelet’ rebus 1: sanghāṭa ‘raft’ sAngaDa ‘catamaran, double-canoe’rebus čaṇṇāḍam (Tu. ജംഗാല, Port. Jangada). Ferryboat, junction of 2 boats, also rafts. 2 jangaḍia 'military guard accompanying treasure into the treasury' ചങ്ങാതം čaṇṇāδam (Tdbh.; സംഘാതം) 1. Convoy, guard; responsible Nāyar guide through foreign territories. rebus 3: जाकड़ ja:kaṛ जांगड़ jāngāḍ ‘entrustment note’ जखडणें tying up (as a beast to a stake) rebus 4: sanghāṭa ‘accumulation, collection’ rebus 5. sangaDa ‘portable furnace, brazier’ rebus 6: sanghAta ‘adamantine glue‘ rebus 7: sangara ‘fortification’ rebus 8: sangara ‘proclamation’ 9. samgraha, samgaha 'arranger, manager'.

Segment 1: As on m857 seal.

![]() Rebus readings in Meluhha: haematite iron ore supercargo

Rebus readings in Meluhha: haematite iron ore supercargo

Segment 2:

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS circumscript of oval: dhALko 'ingot'. Thus ingot for smithy/forge work.

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'

ayo ‘fish’ rebus: aya ‘iron', ayas, 'alloy metal’ khambhaṛā ‘fish fin’ rebus: kammaTa ‘mint, coiner, coinage’

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS aḍaren, ḍaren 'lid, cover'

rebus: aduru 'native, unsmelted metal'

sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' PLUS kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze'

The inscription on Harappa seal h12 is the metalwork catalogue message:

(from) Fortification manager workshop

ingots for smithy/forge work

alloy metal

alloy metal (of, from) mint, coiner, coinage

unsmelted metal (perhaps aduru, meteoric iron or unsmelted ferrite ore)

bronze implements, pots & pans

From bronze workshop.

![]()

Detail from Indus seal M-38 with inscription over unicorn:

http://indusscriptmore.blogspot.com/?fbclid=IwAR2K_ZVecKNc4rbywszMF-LCzujnlOqmAVNo5nmRK1X8hzCqA6r7kvRqdo0

![]()

![]() Text 1012 Mohenjodaro seal. m-626

Text 1012 Mohenjodaro seal. m-626

Line 1 (Top line): (from r. to l.)

Segment 1:

kuṭi 'curve; rebus: कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl (8 parts copper, 2 parts tin), thus, bronze PLUS खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or ʻswordʼ (Prakritam) rebus: khāṇḍa, khaṇḍa 'implements, pots & pans, weapons'.

Segment 2: As on m857 seal.

![]() Rebus readings in Meluhha: haematite iron ore supercargo

Rebus readings in Meluhha: haematite iron ore supercargo

Segment 3:

kuṭi 'curve; rebus: कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl (8 parts copper, 2 parts tin), thus, bronze PLUS खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or ʻswordʼ (Prakritam) rebus: khāṇḍa, khaṇḍa 'implements, pots & pans, weapons'.

Segment 4:

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS circumscript of oval: dhALko 'ingot'. Thus ingot for smithy/forge work.

kanka, karNaka, 'rim of jar' rebus: kaṇḍa kanka 'smelting furnace account (scribe), karṇīka, 'account, scribe', karṇī 'supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.'

Thus, the inscription on seal m 626 is the message:

bronze implements

haematite iron ore supercargo

bonze implements

ingots for smithy,forge

supercargo (from) Fortification manager workshop

1.koDiya ‘rings on neck’, ‘young bull’ koD ‘horn’ rebus 1: koṭiya 'dhow, seafaring vessel' khōṇḍī 'pannier sack' खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) koD 'workshop' khOnda ‘young bull’ rebus 2: kOnda ‘lapidary, engraver’ rebus 3: kundAr ‘turner’ कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. खोट [khōṭa] Alloyed--a metal

2. sangaDa ‘lathe, portable brazier’ sanghaṭṭana ‘bracelet’ rebus 1: sanghāṭa ‘raft’ sAngaDa ‘catamaran, double-canoe’rebus čaṇṇāḍam (Tu. ജംഗാല, Port. Jangada). Ferryboat, junction of 2 boats, also rafts. 2 jangaḍia 'military guard accompanying treasure into the treasury' ചങ്ങാതം čaṇṇāδam (Tdbh.; സംഘാതം) 1. Convoy, guard; responsible Nāyar guide through foreign territories. rebus 3: जाकड़ ja:kaṛ जांगड़ jāngāḍ ‘entrustment note’ जखडणें tying up (as a beast to a stake) rebus 4: sanghāṭa ‘accumulation, collection’ rebus 5. sangaDa ‘portable furnace, brazier’ rebus 6: sanghAta ‘adamantine glue‘ rebus 7: sangara ‘fortification’ rebus 8: sangara ‘proclamation’ 9. samgraha, samgaha'arranger, manager'.

saṁghāṭa m. ʻ fitting and joining of timber ʼ R. [√ghaṭ]Pa. nāvā -- saṅghāṭa -- , dāru -- s° ʻ raft ʼ; Pk. saṁghāḍa -- , °ḍaga -- m., °ḍī -- f. ʻ pair ʼ; M. sãgaḍ f. ʻ a body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together, part of a turner's apparatus ʼ, m.f. ʻ float made of two canoes joined together ʼ (LM 417 compares saggarai at Limurike in the Periplus, Tam. śaṅgaḍam, Tu. jaṅgala ʻ double -- canoe ʼ), sã̄gāḍā m. ʻ frame of a building ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ lathe ʼ; Si. san̆gaḷa ʻ pair ʼ, han̆guḷa, an̆g° ʻ double canoe, raft ʼ.(CDIAL 12859)

Sign 51 Variants. It is seen from all these variants, that the semantic focus signified by the orthography is on the 'scorpion's pointed stinger'![]()

Hieroglyph as it occurs on Mohenjo-daro Seal m-1 Hunter identified the orthographic components of the sign as: 'the tail, back, two ears and hind legs of an animal'. [Hunter, GR, The script of Harappa and Mohenjodaro and its connection with other script, 1934 (2003), New Delhi]

It is assumed that locks of hair are superscripted on the scorpion hieroglyhph. Hieroglyph: *mēṇḍhī ʻ lock of hair, curl ʼ. [Cf. *mēṇḍha -- 1 s.v. *miḍḍa -- ]S. mī˜ḍhī f., °ḍho m. ʻ braid in a woman's hair ʼ, L. mē̃ḍhī f.; G. mĩḍlɔ, miḍ° m. ʻ braid of hair on a girl's forehead ʼ; M. meḍhā m. ʻ curl, snarl, twist or tangle in cord or thread ʼ.(CDIAL 10312). Thus, the message is : meṛed-bica = 'iron (hematite) stone ore'. Hieroglyph: Superscript of a curl to the scorpion hieroglyph: मेढा (p. 665) [ mēḍhā ] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl.(Marathi) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)Modern impression of Harappa Seal h-598 ![]()

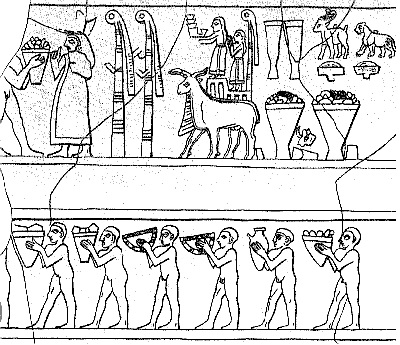

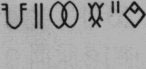

Seals with identical texts from (a) Kish (IM 1822); cf. Mackay 1925 and (b) Mohenjodaro (M-228); cf. Parpola, 1994, p. 132.

The seal impression of a seal from Mohenjo-daro mint found at Kish (an island in the Persian Gulf) had the text message together with lathe+one-horned young bull:ayo ‘fish’ rebus: aya ‘metal’ khambhaṛā ‘fish fin’ rebus:kammaTa ‘mint, coiner, coinage’ bhaTa ‘six’ rebus: baTa‘iron’ kole.l ‘temple’ rebus: kole.l ‘smithy’ kanka ‘rim of jar’ rebus: karNI ‘supercargo’. sangaḍa, 'lathe-brazier' rebus: konda 'young bull' Rebus: kondar 'turner'sangar ‘fortification’, sangaḍa, 'catamaran' koḍiya 'young bull' rebus: koTiya ‘dhow, seafaring vessel’.

![]() A seal inscribed with Harappa Scrpt found in Kish by Oxford Field Museum, (Chicago) Expedition. This is evidence of use of Harappa Script to authenticate long-distance trade by seafaring merchants of Meluhha. Text message from L.to R.

A seal inscribed with Harappa Scrpt found in Kish by Oxford Field Museum, (Chicago) Expedition. This is evidence of use of Harappa Script to authenticate long-distance trade by seafaring merchants of Meluhha. Text message from L.to R.

kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' Reading 2: kuThAru 'treasury' rebus: kuThAru 'armourer'

bicha, 'scorpion' rebus: bica 'haematite, stone ferrite ore'

mẽḍhā ʻcrook, hook', rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Santali.Mu.Ho.)

dāntā 'tooth, tusk' rebus: dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (ferrite ores, copper ores).

![]() The 'hook' hieroglyph is associated with the 'scorpion' hieroglyph. Modern impression of seal L-11 Lothal

The 'hook' hieroglyph is associated with the 'scorpion' hieroglyph. Modern impression of seal L-11 Lothal

Hook hieroglyph:

M. mẽḍhā m. ʻ crook or curved end (of a horn, stick, &c.) ʼ.Thus, the 'crook' hieroglyph is a semantic determinant of the hieroglyph-multiplex composed of the 'curl PLUS crook PLUS scorpion'. Hence, Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) PLUS bicha; that is, the compound phrase meṛed-bica = 'iron (hematite) stone ore' (Santali)

Orthographic variants of the 'scorpion' hieroglyph point to the pointed end of the scorpion's stinger:

![]()

See the 'scorpion' hieroglyph on modern impression of seal M-414 from Mohenjo-daro. After CISI 1:100.

Hieroglyph Ka. koṇḍi the sting of a scorpion. Tu. koṇḍi a sting. Te. koṇḍi the sting of a scorpion.(DEDR 2080). Rebus: kuṇḍī = chief of village. kuṇḍi-a = village headman; leader of a village (Pkt.lex.) i.e. śreṇi jeṭṭha chief of metal-worker guild. khŏḍ m. ‘pit’, khö̆ḍü f. ‘small pit’ (Kashmiri. CDIAL 3947), kuṭhi‘smelter furnace’ (Mu.) kuṇḍamu ‘a pit for receiving and preserving consecrated fire’ (Te.) kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali)

![]()

bicha 'scorpion' (Assamese) Rebus: bica 'stone ore' as in: meṛed-bica = 'iron stone ore', in contrast to bali-bica, 'iron sand ore' (Munda). bichi , ‘hematite’(Asuri)

byucu scorpion (Kashmiri): vŕ̊ścika m. (vr̥ścana -- m. lex.) ʻ scorpion ʼ RV., ʻ cater- pillar covered with bristles ʼ lex. [Variety of form for ʻ scorpion ʼ in MIA. and NIA. due to taboo? <-> √vraśc?]Pa. vicchika -- m. ʻ scorpion ʼ, Pk. vicchia -- , viṁchia -- m., Sh.koh. bičh m. (< *vr̥ści -- ?), Ku. bichī, A. bisā (also ʻ hairy caterpillar ʼ: -- ī replaced by m. ending -- ā), B. Or. bichā, Mth. bīch, Bhoj. Aw.lakh. bīchī, H. poet. bīchī f., bīchā m., G. vīchī, vĩchī m.; -- *vicchuma -- : Paš.lauṛ. uċúm, dar. učum, S. vichū̃ m., (with greater deformation) L.mult. vaṭhũhã, khet. vaṭṭhũha; -- Pk. vicchua -- ,viṁchua -- m., L. vichū m., awāṇ. vicchū, P. bicchū m., Or. (Sambhalpur) bichu, Mth. bīchu, H. bicchū, bīchū m., G. vīchu m.; -- Pk.viccu -- , °ua -- , viṁcua -- m., K. byucu m. (← Ind.), P.bhaṭ. biccū, WPah.bhal. biċċū m., cur. biccū, bhiḍ. biċċoṭū n. ʻ young scorpion ʼ, M. vīċũ, vĩċū m. (vĩċḍā m. ʻ large scorpion ʼ), vĩċvī, °ċvīṇ, °ċīṇ f., Ko. viccu, viṁcu, iṁcu. -- N. bacchiũ ʻ large hornet ʼ? (Scarcely < *vapsi -- ~ *vaspi -- ).Addenda: vŕ̊ścika -- : Garh. bicchū, °chī ʻ scorpion ʼ, A. also bichā (phonet. -- s -- )(CDIAL 12081).

mer.ed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Mundari) samr.obica, stones containing gold (Mundari.lex.)bicamer.ed iron extracted from stone ore; balimer.ed iron extracted from sand ore (Mu.lex.) kut.ire bica duljad.ko talkena, they were feeding the furnace with ore (Mundari)

A Meluhha gloss for hard stone ore or iron stone is mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) which is denoted by the hieroglyph, 'markhor'. miṇḍāl ‘markhor’ (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) Meluhha glosses are annexed which indicate association with cire perdue (or lost wax) method of casting metals using beeswax, particularly in the glosses for miedź, med' 'copper' in Northern Slavic and Altaic languages.

![]()

Wilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:

Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.

Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'.

~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).

Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.

Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.

KW <i>mENhEd</i>

@(V168,M080)

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

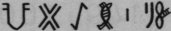

Hieroglyph: X signifies crossing or passing over (Note: the hieroglyph also occurs on Haifa pure tin ingots to signify a mineral element: dhatu).

Te. dã̄ṭu to leap, jump, cross over, pass over, go beyond, transgress; n. a leap, jump, crossing or passing over. Kol. da·ṭ- (da·ṭt-) to cross; da·ṭip- (da·ṭipt-) to make to cross; Ka. dāṭu, dāṇṭu to jump, pass or step over, cross, ford, go beyond, exceed, transgress, pass away, expire; n. passing over, jump across, etc.; dāṭisu, dāṇṭisu to cause to pass over. Koḍ. (Kar.) da·ṭ- (-i-) to cross. Tu.dāṇṭuni to cross, ford, pass by. (DEDR 3158)

Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element' Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ (CDIAL 6773).

Harappa seal h598 (Modern seal impression)

![]() Text 5073[The ligature in-fixed on the last sign of the second line may be Sign 54

Text 5073[The ligature in-fixed on the last sign of the second line may be Sign 54![]() as on Harappa tablet h260]

as on Harappa tablet h260]

Pictorial motifs (Field symbols) on h 598:

1.koDiya ‘rings on neck’, ‘young bull’ koD ‘horn’ rebus 1: koṭiya 'dhow, seafaring vessel' khōṇḍī 'pannier sack' खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) koD 'workshop' khOnda ‘young bull’ rebus 2: kOnda ‘lapidary, engraver’ rebus 3: kundAr ‘turner’ कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. खोट [khōṭa] Alloyed--a metal

2. sangaDa ‘lathe, portable brazier’ sanghaṭṭana ‘bracelet’ rebus 1: sanghāṭa ‘raft’ sAngaDa ‘catamaran, double-canoe’rebus čaṇṇāḍam (Tu. ജംഗാല, Port. Jangada). Ferryboat, junction of 2 boats, also rafts. 2 jangaḍia 'military guard accompanying treasure into the treasury' ചങ്ങാതം čaṇṇāδam (Tdbh.; സംഘാതം) 1. Convoy, guard; responsible Nāyar guide through foreign territories. rebus 3: जाकड़ ja:kaṛ जांगड़ jāngāḍ ‘entrustment note’ जखडणें tying up (as a beast to a stake) rebus 4: sanghāṭa ‘accumulation, collection’ rebus 5. sangaDa ‘portable furnace, brazier’ rebus 6: sanghAta ‘adamantine glue‘ rebus 7: sangara ‘fortification’ rebus 8: sangara ‘proclamation’ 9. samgraha, samgaha 'arranger, manager'.

Line 1

dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting

eraka 'knav of wheel' rebus: erako 'moltencast, metal infusion' eraka, arka 'copper, gold' arA 'spokes of wheel' rebus: Ara 'brass'; kund opening in the nave or hub of a wheel to admit the axle (Santali) Rebus:kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner's lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295).

dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' (Duplication of the hieroglyph || with the spoked wheel hieroglyph in the centre is a phonetic determinant).

Line 1 is thus the messsage: cire perdue metal caster, turner (in smithy/forge)

Line 2 (From r. to l.) 1. dul loa 'copper casting' cīmara 'copper' PLUS

kāru coppersmith metal caster (cire perdue metalcaster, because the ficus leaf is duplicated in mirror image) with furnace for smelting copper, red ore.

![]() Thus, the hypertext on Harappa seal h598 may be read in cypher text as: A pair of ficus leaves PLUS pincer PLUS blackant: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' loa 'ficus religiosa' rebus: loh 'copper, red ore' PLUS baṭa 'rimless, widemouthed pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'.PLUS PLUS cīma ant. rebus: cīmara 'copper' PLUS kāru'pincer' rebus: khār ‘smith’. The hypertext is thus a signifier of a coppersmith metal caster (cire perdue metalcaster, because the ficus leaf is duplicated in mirror image) with furnace for smelting copper, red ore.

Thus, the hypertext on Harappa seal h598 may be read in cypher text as: A pair of ficus leaves PLUS pincer PLUS blackant: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' loa 'ficus religiosa' rebus: loh 'copper, red ore' PLUS baṭa 'rimless, widemouthed pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'.PLUS PLUS cīma ant. rebus: cīmara 'copper' PLUS kāru'pincer' rebus: khār ‘smith’. The hypertext is thus a signifier of a coppersmith metal caster (cire perdue metalcaster, because the ficus leaf is duplicated in mirror image) with furnace for smelting copper, red ore.

![]() meṛed-bica 'hook + scorpion'

meṛed-bica 'hook + scorpion'

1. mẽḍhā ʻcrook, hook', mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Santali.Mu.Ho.) PLUS bica; that is, the compound phrase meṛed-bica = 'iron (hematite) stone ore' (Santali)

2. bicha, 'scorpion' bica 'haematite, ferrite ore' sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' PLUS ayo ‘fish’ rebus: aya ‘metal’ khambhaṛā ‘fish fin’ rebus: kammaTa ‘mint, coiner, coinage’

![]() Temple, warehouse (armoury)

Temple, warehouse (armoury)

kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' Reading 2: kuThAru 'treasury' rebus: kuThAru 'armourer'

kaṇḍa kanka 'smelting furnace account (scribe), karṇīka, 'account, scribe', karṇī 'supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.'

NOTE: On the hypertext shown on h 598, the hieroglyph ‘pincers” is ligatured to a ‘black ant’ hieroglyph and the hypertext compoment is embedded in a hieroglyph composition of two ficus religiosa leaves..

Te. cīma ant. Kol. si·ma, (SR.) sime id. Nk. śīma id. Konḍa sīma id. Kuwi (F. Su.) sīma, (P.) hīma id. (DEDR 2623) This hypertext signifies a particular type of metalworker, one who is a coppersmith working in: cīmara -- ʻcopper. The pincers signify: kāru rebus: khār ‘smith’. hence, cīmara kāra ʻcoppersmithʼ -- an expression cited in Saṁghāṭa sutra.

The hypertext on h598 is dul bhatti cīmarakāra ʻmetal casting furnace coppersmith; the hypertexts on l-14, m-1555, m-1566, m-604, m-600, are dul bhatti lohakara ‘metal casting furnace metalsmith’; and the hypertext on m-1563 in dul bhatti loha-khāṇḍa-kara ‘metal casting furnace metal implements artisan’. Evidence is presented and analysed in Annex H Black ant hieroglyph and cīmara kāra ʻcoppersmithʼ. Many such hypertext signs may be seen in List of Harappa Script ‘signs’ in the Corpora in Harappa Script & Language (S. Kalyanaraman, 2016).

Explaining hieroglyph 'blackant' in hypertexts of Harappa Script

Harappa tablet 206 signifies a blackant as a hieroglyph.చీమ [ cīma ] chīma. [Tel.] n. An ant. కొండచీమ. the forest ant. రెక్కలచీమ a winged ant. పారేచీమను వింటాడు he can hear an ant crawl, i.e., he is all alive.చీమదూరని అడవి a forest impervious even to an ant. చలిచీమ a black ant; పై పారేపక్షి కిందపారే చీమ (proverb) The bird above, the ant below, i.e., I had no chance with him. చీమంత of the size of an ant. చీమపులి chīma-puli. n. The ant lion, an ant-eater.

చీముంత [ cīmunta ] chīmunta.. [Tel.] n. A metal vessel. చెంబు.

†cīmara -- ʻ copper ʼ in cīmara -- kāra -- ʻ coppersmith ʼ in Saṁghāṭa -- sūtra Gilgit MS. 37 folio 85 verso, 3 (= zaṅs -- mkhan in Tibetan Pekin text Vol. 28 Japanese facsimile 285 a 3 which in Mahāvyutpatti 3790 renders śaulbika -- BHS ii 533. But the Chinese version (Taishō issaikyō ed. text no. 423 p. 971 col. 3, line 2) has t'ie ʻ iron ʼ: H. W. Bailey 21.2.65). [The Kaf. and Dard. word for ʻ iron ʼ appears also in Bur. čhomār, čhumər. Turk. timur (NTS ii 250) may come from the same unknown source. Semant. cf. lōhá -- ]Ash. ċímä, ċimə ʻ iron ʼ (ċiməkára ʻ blacksmith ʼ), Kt. čimé;, Wg. čümāˊr, Pr. zíme, Dm. čimár(r), Paš.lauṛ. čimāˊr, Shum. čímar, Woṭ. Gaw. ċimár,Kal. čīmbar, Kho. čúmur, Bshk. čimer, Tor. čimu, Mai. sē̃war, Phal. čímar, Sh.gil. čimĕr (adj. čĭmārí), gur. čimăr m., jij. čimer, K. ċamuru m. (adj.ċamaruwu).(CDIAL 14496)

![]()

See examples of inscriptions which signify 'coppersmith' cīmara 'copper' PLUSkāru'pincer' rebus: khār ‘smith’ at

![]() This hypertext of 'fish ligatured with fins' is signified on h598 seal text message.

This hypertext of 'fish ligatured with fins' is signified on h598 seal text message.

Explaining 'fish' and 'zebu hieroglyphs (alloy metal, magnetite ferrite ore)

Many scholars (e.g., Knorozov, Parpola, Mahadevan) see this sign as a fish. The accent is on ‘fin’ hieroglyph ligature. ayo, aya ‘fish’ rebus: aya ‘iron’ ayas ‘metal’ PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish fin’ rebus:kammaṭa ‘mint, coiner, coinage’. Thus, iron metal mint.

![]() Mohenjo-daro Seals m1118 and Kalibangan 032, glyphs used are: Zebu (bos taurus indicus), fish, four-strokes (allograph: arrow). ayo, aya ‘fish’ (Mu.) + kāṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.)gaṇḍa, ‘four’ (Santali); Rebus: kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar’, ‘furnace’), kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ read rebus in mleccha (Meluhha) as a reference to a guild of artisans working with ayaskāṇḍa ‘excellent quantity of iron’ (Pāṇini) is consistent with the primacy of economic activities which resulted in the invention of a writing system, now referred to as Harappa Script Writing.

Mohenjo-daro Seals m1118 and Kalibangan 032, glyphs used are: Zebu (bos taurus indicus), fish, four-strokes (allograph: arrow). ayo, aya ‘fish’ (Mu.) + kāṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.)gaṇḍa, ‘four’ (Santali); Rebus: kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar’, ‘furnace’), kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ read rebus in mleccha (Meluhha) as a reference to a guild of artisans working with ayaskāṇḍa ‘excellent quantity of iron’ (Pāṇini) is consistent with the primacy of economic activities which resulted in the invention of a writing system, now referred to as Harappa Script Writing.

![]() पोळ pōḷa 'zebu’ See: bolad 'steel' (Russian) folad 'steel' (Old Persian). It is possible that the word bolad (Russian) was cognate with पोळ (p. 305) pōḷa m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. पोळा (p. 305) pōḷā m (पोळ) A festive day for cattle, the day of new moon of श्रावण or of भाद्रपद. Bullocks are exempted from labor; variously daubed and decorated; and paraded about in worship rebus: पोळ pōḷa 'magnetite (a ferrite ore)'. dāntā 'tooth, tusk' rebus: dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (ferrite ores, copper ores).

पोळ pōḷa 'zebu’ See: bolad 'steel' (Russian) folad 'steel' (Old Persian). It is possible that the word bolad (Russian) was cognate with पोळ (p. 305) pōḷa m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. पोळा (p. 305) pōḷā m (पोळ) A festive day for cattle, the day of new moon of श्रावण or of भाद्रपद. Bullocks are exempted from labor; variously daubed and decorated; and paraded about in worship rebus: पोळ pōḷa 'magnetite (a ferrite ore)'. dāntā 'tooth, tusk' rebus: dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (ferrite ores, copper ores).

Vivid hieroglyph hypertexts on Indus Script Corpora include animals tied to a long rope. Such signifiers occur, for example on a Kalibangan terracotta cake which signifies a tiger tied to a rope and dragged; and on Nausharo storage pots which signify a zebu tied with a rope to a pillar/port/tree trunk.

In one hypertext (as on the Kulli plate), three distinct ropes are signified: tri-dhAu ‘three strands’ rebus: tri-dhAtu ‘three minerals’.

These hypertexts signify:

1. पोळ [pōḷa] tāvaṇi, dāmanī मेढ [ mēḍha ] 'zebu PLUS rope PLUS stake'

2. kola, tāvaṇi, dāmanī मेढ [ mēḍha ] 'tiger PLUS rope PLUS stake'

Rebus signifiers are: 1. पोळ [pōḷa] 'magnetite, ferrite ore' and 2. kol 'working in iron' PLUS meD 'iron' PLUS

dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron-- smeltersʼ. Thus, the message is: smelter of iron, magnetite.

The Prakritam gloss पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' as hieroglyph is read rebus: pōḷa, 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide'; poliya 'citizen, gatekeeper of town quarter'.

kola 'tiger' rebus: kolle 'blacksmith', kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'

tāvaṇi, dāmanī 'long rope' rebus: dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ

The stake to which the animal is tied with rope is a semantic determinant reinforcing that the smelted metal is 'iron'.

मेढ [ mēḍha ] f A forked stake rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.); med 'copper' ![]()

मेढ [ mēḍha ] f A forked stake. Used as a post. Hence a short post generally whether forked or not. Pr. हातीं लागली चेड आणि धर मांडवाची मेढ.Hieriglyph: meṛh rope tying to post, pillar: mēthí m. ʻ pillar in threshing floor to which oxen are fastened, prop for supporting carriage shafts ʼ AV., °thī -- f. KātyŚr.com., mēdhī -- f. Divyāv. 2. mēṭhī -- f. PañcavBr.com., mēḍhī -- , mēṭī -- f. BhP.1. Pa. mēdhi -- f. ʻ post to tie cattle to, pillar, part of a stūpa ʼ; Pk. mēhi -- m. ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ, N. meh(e), miho, miyo, B. mei, Or. maï -- dāṇḍi, Bi. mẽh, mẽhā ʻ the post ʼ, (SMunger) mehā ʻ the bullock next the post ʼ, Mth. meh, mehā ʻ the post ʼ, (SBhagalpur)mīhã̄ ʻ the bullock next the post ʼ, (SETirhut) mẽhi bāṭi ʻ vessel with a projecting base ʼ.2. Pk. mēḍhi -- m. ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ, mēḍhaka<-> ʻ small stick ʼ; K. mīr, mīrü f. ʻ larger hole in ground which serves as a mark in pitching walnuts ʼ (for semantic relation of ʻ post -- hole ʼ see kūpa -- 2); L. meṛh f. ʻ rope tying oxen to each other and to post on threshing floor ʼ; P. mehṛ f., mehaṛ m. ʻ oxen on threshing floor, crowd ʼ; OA meṛha, mehra ʻ a circular construction, mound ʼ; Or. meṛhī,meri ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ; Bi. mẽṛ ʻ raised bank between irrigated beds ʼ, (Camparam) mẽṛhā ʻ bullock next the post ʼ, Mth. (SETirhut) mẽṛhā ʻ id. ʼ; M. meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻ post, forked stake ʼ.mēthika -- ; mēthiṣṭhá -- . mēthika m. ʻ 17th or lowest cubit from top of sacrificial post ʼ lex. [mēthí -- ]Bi. mẽhiyā ʻ the bullock next the post on threshing floor ʼ.mēthiṣṭhá ʻ standing at the post ʼ TS. [mēthí -- , stha -- ] Bi. (Patna) mĕhṭhā ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ, (Gaya) mehṭā, mẽhṭā ʻ the bullock next the post ʼ.(CDIAL 10317 to, 10319) Rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.); med 'copper' (Slavic)

![]()

Large storage pot. Nausharo? Smith working in magnetite, ferrite ore

poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite' ayo 'fish' rebus: aya'iron' ayas 'metal; ḍhaṁkhara — m.n. ʻbranch without leaves or fruitʼ (Prakrit) (CDIAL 5524) Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' (Maithili) kUdI 'twig', kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi'smelter' meDh 'polar star', meRh 'tied rope' rebus: meD'iron' med 'copper' khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus:kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) kharadaखरडें daybook

Just as ‘text signs’ are ligatured with modifiers, a unique orthographic device is used on Harappa Scrip inscriptions. This orthographic device may be called ‘hypertexting’. Such hypertexting is a principal reason for the number of ‘text signs’ to total over 400.

On the stamp seal h598, this orthographic device can be seen as hieroglyphs of ‘rings on neck’, ‘one horn’ (on the young bull), ‘rings on neck’, pannier on shoulder. All these hieroglyphs constitute a hypertext. Similarly, the standard device shown in front of the hypertext ‘one-horned young bull’ is a combination of two major components: top register signifying a lathe with gimlet and the bottom register held on a flagpost signifying a bowl or portable furnace with smoke emanating from the surface and with the hieroglyphs of dotted circles on the bottom bowl.

![]() Lothal 11 seal. Pictorial motifs (Field symbols) on Lothal 11 seal:

Lothal 11 seal. Pictorial motifs (Field symbols) on Lothal 11 seal:

1.koDiya ‘rings on neck’, ‘young bull’ koD ‘horn’ rebus 1: koṭiya 'dhow, seafaring vessel' khōṇḍī 'pannier sack' खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) koD 'workshop' khOnda ‘young bull’ rebus 2: kOnda ‘lapidary, engraver’ rebus 3: kundAr ‘turner’ कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. खोट [khōṭa] Alloyed--a metal

2. sangaDa ‘lathe, portable brazier’ sanghaṭṭana ‘bracelet’ rebus 1: sanghāṭa ‘raft’ sAngaDa ‘catamaran, double-canoe’rebus čaṇṇāḍam (Tu. ജംഗാല, Port. Jangada). Ferryboat, junction of 2 boats, also rafts. 2 jangaḍia 'military guard accompanying treasure into the treasury' ചങ്ങാതം čaṇṇāδam (Tdbh.; സംഘാതം) 1. Convoy, guard; responsible Nāyar guide through foreign territories. rebus 3: जाकड़ ja:kaṛ जांगड़ jāngāḍ ‘entrustment note’ जखडणें tying up (as a beast to a stake) rebus 4: sanghāṭa ‘accumulation, collection’ rebus 5. sangaDa ‘portable furnace, brazier’ rebus 6: sanghAta ‘adamantine glue‘ rebus 7: sangara ‘fortification’ rebus 8: sangara ‘proclamation’ 9. samgraha, samgaha 'arranger, manager'. Text message from r. to l.: kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze' sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS loa ficus religiosa' rebus: loh 'copper' PLUS kAru 'pincer' rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Thus, coppersmith cire perdue metalcaster).

bicha, 'scorpion' rebus: bica 'haematite, stone ferrite ore'

mẽḍhā ʻcrook, hook', rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Santali.Mu.Ho.)

baṭa = rimless pot (Kannada) Rebus: baṭa = a kind of iron (Gujarati) bhaTa 'furnace' PLUS muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced from a furnace (Santali)

kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge'.

Hook hieroglyph:

M. mẽḍhā m. ʻ crook or curved end (of a horn, stick, &c.) ʼ.Thus, the 'crook' hieroglyph is a semantic determinant of the hieroglyph-multiplex composed of the 'curl PLUS crook PLUS scorpion'. Hence, Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) PLUS bicha; that is, the compound phrase meṛed-bica = 'iron (hematite) stone ore' (Santali)

Orthographic variants of the 'scorpion' hieroglyph point to the pointed end of the scorpion's stinger: The text message: bica 'scorpion' rebus: bica 'haematite,ferrite ore' baTa 'wide mouthed pot' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'worskhop' karṇaka 'rim of jar' (Samskritam) Rebus: kharva 'wealth, nidhi'; karba 'iron' karNI 'supercargo' karNIka 'scribe'. ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal alloy' Sign 342 variants

![Image result for scorpion indus script hieroglyph]() Daimabad seal. Rim of narrow-necked jar. Pottery Kalibangan 105

Daimabad seal. Rim of narrow-necked jar. Pottery Kalibangan 105 karṇaka 'rim of jar' (Samskritam) Rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNIka 'scribe'.

![]()

Sign 51 Variants. It is seen from all these variants, that the semantic focus signified by the orthography is on the 'scorpion's pointed stinger'

These are two glyphs of the script with unique superscripted ligatures; this pair of ligatures does not occur on any other ligatured glyph in the entire corpus of Indus script inscriptions. Orthographically, Sign 51 glyph is a ‘scorpion’; Sign 327 glyph is a ‘ficus glomerata leaf’. The glosses for the ‘sound values’ are, respectively: bica ‘scorpion’ (Santali), lo ‘ficus’ (Santali).

aya 'fish' Rebus: ayas 'metal'

The meaning of 'ayas' in Rigveda has been uncertain and conjectures have been made from the texts as exemplified by the succinct presentation by

Arthur Anthony Macdonell, and Arthur Berriedale Keith:

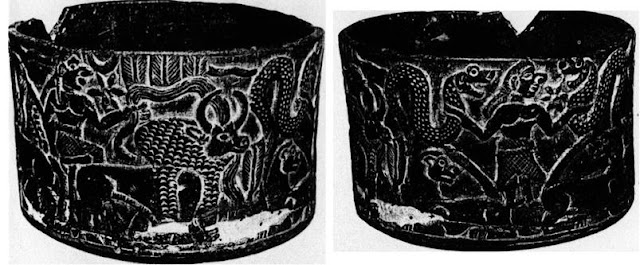

Hieroglyphs of two Samarra bowls

Image 1. Eight fish, four peacocks holding four fish, slanting strokes surround

Image 2. Six women, curl in hair, six scorpions

ayo ‘fish’; rebus: ayas ‘metal’

mora peacock; morā ‘peafowl’ (Hindi); rebus: morakkhaka loha, a kind of copper, grouped with pisācaloha (Pali). moraka "a kind of steel" (Sanskrit)

gaṇḍa set of four (Santali); rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali)

मेढा [mēḍhā] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl (Marathi). S. mī˜ḍhī f., °ḍho m. ʻ braid in a woman's hair ʼ, L. mē̃ḍhī f.; G. mĩḍlɔ, miḍ° m. ʻbraid of hair on a girl's forehead ʼ (CDIAL 10312). मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock.मेढा [ mēḍhā ] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl. Rebus: mē̃ḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.) meṛha M. meṛhi F.’twisted, crumpled, as a horn’; meṛha deren ‘a crumpled horn’ (Santali)

bicha, bichā ‘scorpion’ (Assamese) Rebus: bica ‘stone ore’ (Mu.) sambr.o bica = gold ore (Mundarica) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Mu.lex.)

bhaṭa ‘six ’; rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

satthiya ‘svastika glyph’; rebus: satthiya ‘zinc’, jasta ‘zinc’ (Kashmiri), satva, ‘zinc’ (Pkt.)

kola ‘woman’; rebus: kol ‘iron’. kola ‘blacksmith’ (Ka.); kollë ‘blacksmith’ (Koḍ)

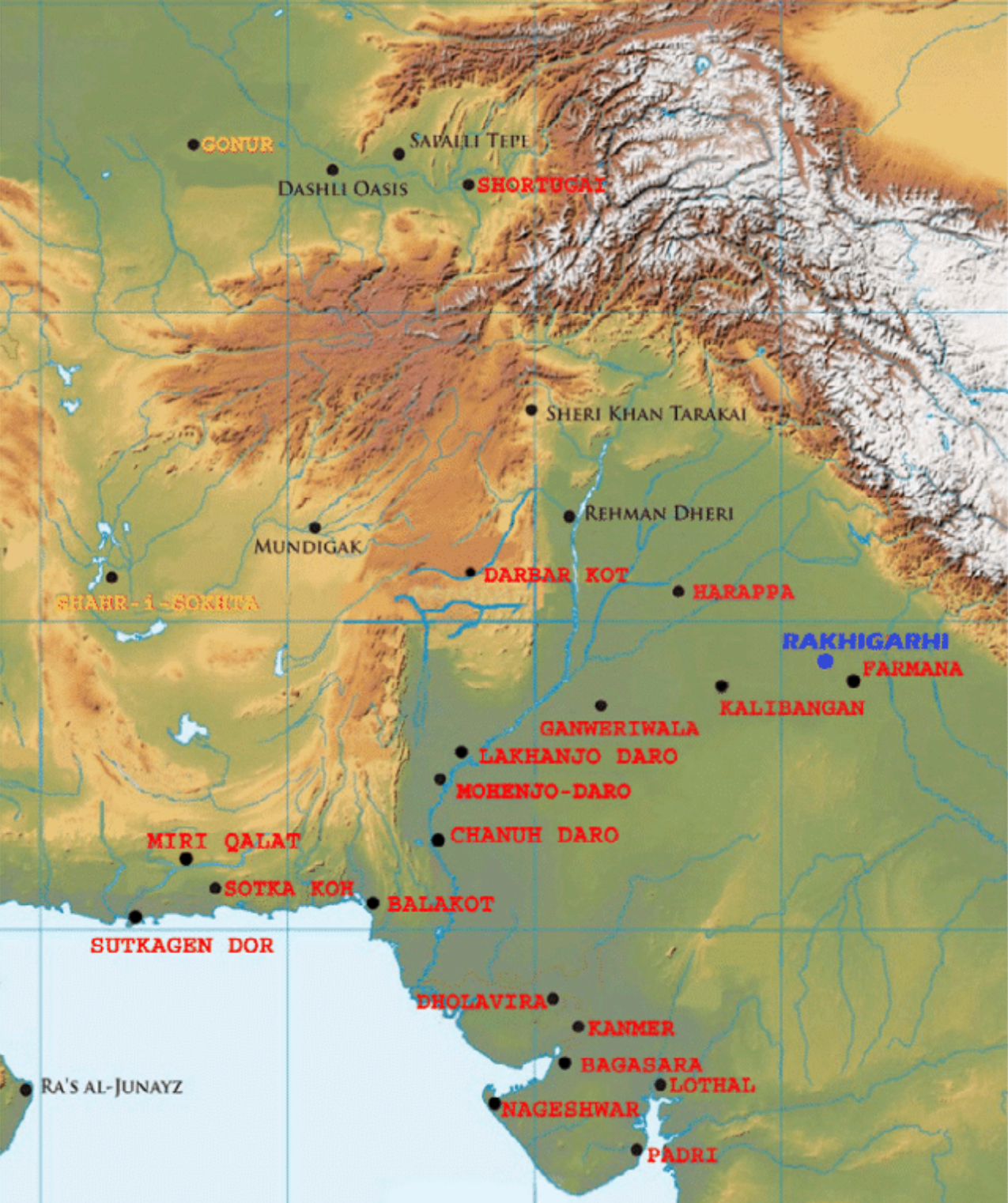

Sources for the images:

Image 1. The Samarra bowl (ca. 4000 BC) at on exhibit at the Pergamon museum, Berlin. The bowl was excavated as Samarra by Ernst Herzfeld in the 1911-1914 campaign, and described in a 1930 publication. The design consists of a rim, a circle of eight fish, and four fish swimming towards the center being caught by four birds. At the center is a swastika symbol. (Ernst Herzfeld, Die vorgeschichtlichen Töpfereien von Samarra, Die Ausgrabungen von Samarra 5, Berlin 1930.)

Image 2. Women with flowing hair and scorpions, Samarra, Iraq. After Ernst Herzfeld, Die Ausgrabungen von Samarra V: Die vorgeschichtischenTopfereien, Univ. of Texas Press, pl. 30. Courtesy Dietrich Reimer. This image is discussed in Denise Schmandt-Besserat, When writing met art, p.19. “The design features six humans in he center of the bowl and six scorpions around the inner rim. The six identical anthropomorphic figures, shown frontally, are generally interpreted as females because of their wide hips, large thighs, and long, flowing hair…Six identical scorpions, one following after the other in a single line, circle menacingly around the women.”

Scorpion hieroglyph on an Assyrian tablet

![]()

After Figs. 439-440. Tablet with envelope: Marriage contract of an Assyrian merchant with an Anatolian woman. 1950-1835 BCE. Clay. Ankara Museum of Anatolian civilisations. Meluhha hieroglyphs (Bottom register): bull, ram, scorpion, serpent. ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’. meḍh ‘ram’. Rebus:meḍ ‘iron’. bicha ‘scorpion’ Rebus: bica ‘stone ore’. nāga ‘serpent Rebus: nāga ‘lead’. The merchant is perhaps trades: lead, stone ore, iron.

After Fig. 410. Tablet: A notary document. 1830-1700 BCE. Clay. Ankara Museum of Anatolian civilisations. Kt. n/k.032, inv. no. 165-32-64. Top register seal impression.Hieroglyphs: lion, goat looking back, two tigers. kol 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. arye 'lion' Rebus: arā ‘brass’ mlekh 'goat' Rebus: milakkhu 'copper'. krammara 'look back' Rebus: kamar 'smith, artisan'. Thus, milakkhu kamar 'copper smith'.

Hypertext formation in Harappa Script explained by Dennys Frenez & Massimo Vidale

![]()

Harappan chimaera and its hypertextual components. Harappan chimera and its hypertextual components. The 'expression' summarizes the syntax of Harappan chimeras within round brackets, creatures with body parts used in their correct anatomic position (tiger, unicorn, markhor goat, elephant, zebu, and human); within square brackets, creatures with body parts used to symbolize other anatomic elements (cobra snake for tail and human arm for elephant proboscis); the elephant icon as exonent out of the square brackets symbolizes the overall elephantine contour of the chimeras; out of brackes, scorpion indicates the animal automatically perceived joining the lineate horns, the human face, and the arm-like trunk of Harappan chimeras. (After Fig. 6 in: Harappan chimaeras as 'symbolic hypertexts'. Some thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization (Dennys Frenez & Massimo Vidale, 2012).

Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale focus attention on pictorial motifs and on m0300 seal, identify a number of hieroglyph components constituting the hieroglyph-multiplex -- on the pictorial motif of 'composite animal', seen are hieroglyph components (which they call hypertextual components): serpent (tail), scorpion, tiger, one-horned young bull, markhor, elephant, zebu, standing man (human face), man seated in penance (yogi).

The yogi seated in penance and other hieroglyphs are read rebus in archaeometallurgical terms: kamaDha 'penance' (Prakritam) rebus: kampaTTa 'mint'. Hieroglyph: kola 'tiger', xolA 'tail' rebus:kol 'working in iron'; kolle 'blacksmith'; kolhe 'smelter'; kole.l 'smithy'; kolimi 'smithy, forge'. खोड [khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi) rebus: khond 'turner'. dhatu 'scarf' rebus: dhatu 'minerals'.bica 'scorpion' rebus: bica 'stone ore'. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati) Rebus:meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) mẽṛhet iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda) kara'elephant's trunk' Rebus: khar 'blacksmith'; ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron'. Together: karaibā 'maker, builder'.

Use of such glosses in Meluhha speech can be explained by the following examples of vAkyam or speech expressions as hieroglyph signifiers and rebus-metonymy-layered-cipher yielding signified metalwork:

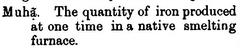

Example 1: mũh opening or hole (in a stove for stoking (Bi.); ingot (Santali) mũh metal ingot (Santali)mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt= iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends;kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) kaula mengro‘blacksmith’ (Gypsy) mleccha-mukha (Samskritam) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali) The Samskritam glossmleccha-mukha should literally mean: copper-ingot absorbing the Santali gloss, mũh, as a suffix.

Example 2: samṛobica, stones containing gold (Mundari) samanom = an obsolete name for gold (Santali) [bica ‘stone ore’ (Munda): meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda)].

In addition to the use of hieroglyph-components to create hieroglyph-multiplexes of pictorial motifs such as 'composite animals', the same principle of multiplexing is used also on the so-called 'signs' of texts of inscriptions.

h95 tablet.

h95 tablet.

L

L

Cloth worn onGaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan. Hieroglyph: படம்¹ paṭam

Cloth worn onGaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan. Hieroglyph: படம்¹ paṭam

![clip_image057[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0574-thumb.jpg?w=80&h=68)

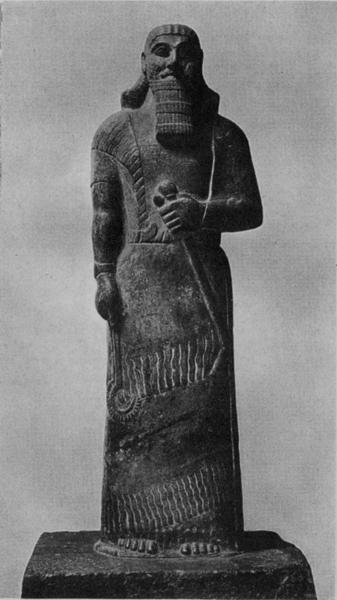

Shalmaneser III

Shalmaneser III  British Museum.

British Museum.  Unprovenienced. Person with a mace.

Unprovenienced. Person with a mace. Bactria Margiana. Bronze macehead with snake hieroglyph

Bactria Margiana. Bronze macehead with snake hieroglyph

Maceheads. Votive?

Maceheads. Votive?

Three-faced person with armlets, bracelets seated on a stool with bovine legs.

Three-faced person with armlets, bracelets seated on a stool with bovine legs.

A person is a standard bearer of a banner holding aloft the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Indus writing. The banner is comparable to the banner shown on two Mohenjo-daro tablets.

A person is a standard bearer of a banner holding aloft the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Indus writing. The banner is comparable to the banner shown on two Mohenjo-daro tablets.

Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150)

Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150) Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.

Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.

Cylinder seal of Shu-ilishu, interpreter for Meluhha. Cuneiform inscription in Old Akkadian. Serpentine. Mesopotamia ca 2220-2159 BCE H. 2.9 cm, Dia 1.8 cm Musee du Louvre, Departement des Antiquites, Orientales, Paris AO 22310

Cylinder seal of Shu-ilishu, interpreter for Meluhha. Cuneiform inscription in Old Akkadian. Serpentine. Mesopotamia ca 2220-2159 BCE H. 2.9 cm, Dia 1.8 cm Musee du Louvre, Departement des Antiquites, Orientales, Paris AO 22310  12th cent. BCE.

12th cent. BCE.

![The expression "Country of Me-lu-ha" (Me-luh-ha Ki) on Akkadian inscriptions.[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a1/Akkadian_cylinder_seal_with_inscription_Shu-ilishu%2C_interpreter_of_the_Meluhhan_language%2C_Meluha_inscription_Me-luh-ha-ki%2C_land_of_Meluhha_Louvre_Museum_AO_22310.jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)