Sunil Menon: Prof Shinde, what does Rakhigarhi tell us?

V.S. Shinde: We had very little idea about the regional diversity during Harappan times. We always think the Harappan civilisation was homogeneous. In some respects, that’s true. But there were different ecological zones, and you find diversity flowing from that. Like, Gujarat has a slightly different variety compared to the Saraswati region. But overall there is a concept of one nation. This concept was introduced by the Harappans.

Menon: From archaeological findings, how do you arrive at something as abstract as a nation?

Shinde: See, the Harappan culture occupied about 2 million sq km. Over this vast area, they established some kind of uniform culture. This shows they had united different regions. Not by force, but by mutual consent.

Siddhartha Mishra: Because they never had an army…

Shinde: Yes, they never had one. So we wanted to understand the specific variation of culture in this part. What are its features, how that came into being. We use two terms: one is Harappan culture, the other is Harappan civilisation. The Harappan culture’s time-span is from 5500 BC to 1500 BC. But there’s one phase within that where we find tremendous development and prosperity, where they started developing cities and towns. That’s the Harappan civilisation phase: from 2600 BC to about 1900 BC. We haven’t really understood how the transformation occurred. We wanted to demonstrate that in the structures, in the pottery, other elements of material culture. And this site is ideal for that as we have the early Harappan phase and then the mature phase too.

Menon: Rakhigarhi also unsettles the idea that the Indus was the centre of gravity of Harappan culture, with a few radiating elements. The centre of gravity itself seems to be shifting here…given its size and time-scale.

Shinde: This whole area, the ancient Saraswati region, is so important. Two-thirds of the Harappan sites are in this region. And maybe not many sites in the Indus region.

Menon: But the Indus as a coherent centre also sits well with the idea of a site like Mehrgarh in Balochistan, evolving from the Neolithic to eventually give us the big cities.

Shinde: So now we have a site like Bhirrana. As old as Mehrgarh. That is, 6500-7000 BC.

Mishra: All of them coexisting….

Shinde: Exactly, and they were in touch with each other, all material developments were simultaneous. So we cannot pinpoint the Sindh region as the nucleus, from where it begins to disperse. It’s not like that. The whole map was occupied by the early communities, evolving simultaneously; ideas flowed from one region to another because of constant contact right from the beginning.

Mishra: Are there cultural differences between the sites?

Shinde: You mostly find the same culture, with a little variation, maybe because of different food habits, or different traditions. Otherwise it was a more or less uniform culture. The same 1.73 gram weight, maybe a slight variation in the shape of pottery…that’s all.

“We cannot pinpoint the Sindhu region as the nucleus from where the Harappan culture begins to disperse. It’s not like that.”

Menon: Harappan cities were even internally heterogeneous...we can talk about shared culture, not ethnicity....

Shinde: We don’t have enough data—very little from Sindh, a bit from Punjab. We have DNA data from Rakhigarhi; we are in the final phase of studying it, but we cannot generalise from that. I believe there were different types of ethnic groups across the Harappan map.

We now have an idea about the cultural evolution in Rakhigarhi. It’s not like the concept of the city came suddenly. The early farmers around 5500 BC were rural; they lived in small circular huts. In the next stage, we get rectangular structures. In the third stage, there’s better planning, bigger rectangular structures. Then they transform it into a city. Elaborate planning, the concept of drainage, bathrooms.

Mishra: And what brings on the decline?

Shinde: Aridity. The Saraswati slowly dries out…probably they had to leave the site itself. The Harappans had flourishing trade with the west, particularly with Egypt. We have archaeological data as well as literary data: the Mesopotamian texts mention it. Of the goods coming from Meluhha, they talk about ‘the red metal’ (copper), articles made of red stones, the semi-precious carnelian, various spices, ivory.

Menon: Was Yamuna the outer limit?

Shinde: Actually, the Gangetic plain is the main boundary, beyond that are zones of Harappan influence. Harappans may have supplied Bihar and its neighbours with technology. There’s influence up to Jammu and the entire Makran coast and Iran. You find different categories of settlements, all in a symbiotic relationship. Out of 2,000 settlements, we have identified five proper cities. Then maybe half-a-dozen towns like Kalibangan or Lothal, and a network of agricultural settlements, villages, and manufacturing centres like Chanhudaro. Also, a large number of ports and small settlements for exploitation of local resources. There’s a pattern of interaction between the cities and the rest.

Menon: Do you find any influence on the Harappans from the outside?

Shinde: We don’t really see that. Some marginal influence perhaps, like the Mesopotamian figure of Gilgamesh shows up in a Harappan form, that’s all. What sets them apart from contemporary civilisations is this: the Harappans did not have Giza, they did not build pyramids or monumental structures like those. They were very capable of building those, having acquired a lot of wealth from the western trade. Instead, the Harappans used that wealth to create healthy, hygienic living cities for the welfare of the common people. That was the difference in philosophy. So, right from the beginning, we were practical people. Only if you emphasise these aspects will people realise the importance of this civilisation.

Mishra: How were they governed?

Shinde: They had a two-tier administrative system, such as today’s. Kautilya had these ideas because the system was already there before his time. We talk of Kautilya’s Arthashastra, but the ideas were very much there from before. Our system is, in fact, derived from theirs. We still have the panchayat system…that continues from Harappan times.

The Pakistani archaeologist Rafiq Mughal observed that there were two kinds of capitals during those times. In each ecological zone, you find one big settlement. That acted like some kind of a regional capital. Probably, some decisions were taken at the capital. Such as, ‘What should be the brick size?’, ‘What should be the denominations of the seals?’. Then the regional capital enforced those. This is how they maintained uniformity over such a large area.

“Harappans were quite capable of building monumental structures like the pyramids, but used their wealth to create happy, living cities.’

Mishra: And religion?

Shinde: We don’t have much evidence. But one thing is clear: they were not practising religion as a community, like today. Maybe it was an individual thing. You find a few figurines—probably they were worshipped. The proto-Shiva, a few linga types, but most probably they were in households. We don’t know. But you do not find temples as such.

Menon: So potentially different peoples, perhaps even speaking different languages, sharing only a kind of unified system….

Shinde: Exactly. They must have had some kind of uniform writing system. Right from Afghanistan or the Iranian border, we find the same sort of letters. Not much difference. Maybe parallel languages were spoken. Maybe there were dialects. But the writing system was the same. Like today’s Devnagari is used by both Marathi and Hindi.

After Meluhha, The Melange

India was never isolated. It’s seen a number of migrations, including the Vedic ‘Aryans’—and the Veda was no continuation of Harappan religion.

We Are All Harappans

The Rakhigarhi project shines light on an old enigma: the Harappans were genetically ‘Ancestral South Indian’ stock. Which is to say, all of us in South Asia are their children.

The Pashupati seal

Slice Of Pie

- Proto-Indo-European was spoken in the Pontic-Caspian steppe around 4000 BC.

- Spread through Eurasia. One line went west, into Europe. One, Indo-Iranian, came south.

- The Indo-Aryan family branched off from that.

***

Michael Witzel is the Wales Professor of Sanskrit at Harvard University. At a conference earlier this year, he gave a talk titled Beyond the Flight of the Falcon: Early ‘Aryans’ within and outside India, to be published in Kumkum Roy et al. Excerpts from a version edited and extended for Outlook:

A major problem was, and to an extent still is, dating the early arya texts, especially the timeframe of the Rigvedic period. Archaeology alone cannot yet deliver relevant dates for northwest India (Greater Punjab), that is, for the end of the Harappan civilisation at 1900/1300 BC and the beginning of the Vedic civilisation. Rather, it is a combination of textual and linguistic data that indicates the Vedic period’s beginning. Increasingly, fine-grained genetic data, especially ancient DNA, may substantiate these results.

Archaeology

For a potential beginning of the (Rig) Vedic period, only a small area of Harappa has been stratigraphically (the study of rock layers) studied, providing data for around 1300 BC. Importantly, while the general Harappan pottery design is maintained, the vessels reveal some new designs and a shift to cremation with subsequent urn burial; more recently, additional data have emerged, like the extensive Harappan graveyard at Farmana, and the recently found burials at Sinauli, allegedly dating to 1800-2000 BC—well before the immigration of the Indo-Aryans (IAs) to Greater Punjab. Thus, any overlap between Harappan and Vedic civilisations is as yet unclear, though it can be expected for the Haryana/Delhi area.

Importantly, the people of the Vedic civilisation were semi-nomadic and did not dwell in the post-Harappan agricultural villages of Haryana; instead, they were constantly on the move with their cattle. We still need to find clear pastoral remains of the period. Still, pottery remains and linguistic data indicate extensive communication between the two populations: there are many non-IA loanwords from before, during, and after the Rigvedic period.

As for clear repercussions of the Harappan civilisation on the Vedic populations, we must study: 1. the few clear archaeological indications (continuing pottery style [always the norm in successive cultures], depictions on vases, the red parting line in married women’s hair on some figures, etc.), 2. apparent remnants, merely in low-level strata of religion and 3. the impact of the (northern) Indus language on Rigvedic and later Vedic. All these indicate only minor continuation of Harappan elements, compared to the major rupture in civilisation beginning with the immigration of IA speaking populations around 1200 BC.

Linguistics

There was a northern and a southern (“Meluhha”) Indus substrate (a language that influences a more prestigious one) that influenced the IA language. Research, including evidence from Sindhi place names, points to a (later?) Dravidian settlement in that area (and Maharashtra), before IA speakers introduced the ancestor of modern Sindhi. It remains unclear when the Dravidians moved into the Indus area.

In this connection, the question of the Indus inscriptions on seals and small tablets is relevant. Some, like Parpola, assume the underlying language is Dravidian. However, no “decipherment” has been accepted by serious scholars. Farmer, Sproat and Witzel have indicated that these signs must not indicate a script that can depict spoken language, but can be symbols.

The arrival of IA speakers in Greater Punjab is heralded by many loanwords derived from the substrate language of this area, the Northern Indus language. I have called this northern Indus language “Para-Munda” as it shares only partof typical Munda traits. There are about 300 loanwords in the Rigveda, even discounting loans that occurred earlier during the IA migration. Importantly, the oldest Rigvedic loans are not from Proto-Dravidian.

There are no loans reflecting the Harappans’ international trade, seals, staple cereal (wheat, which appears only from the Atharvaveda onwards), towns, mythology (e.g., involving a tree goddess and a tiger, etc.). Clearly, the loans come from the post-Harappan rural population. They increase in post-Rigvedic times and involve other language families, including Dravidian.

Genetics

A revolution has occurred, in the past 10 years or so, with the possibility of sequencing ancient DNA (aDNA), allowing us to specify population history in finer detail. We had no Indian aDNA until very recently, and recent excavations at Indus sites (Farmana cemetery, etc.) have yielded no genetic results so far. But we now (May 2018) have aDNA from the Swat Valley. Further, reports of aDNA from the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi have finally (June 2018) been announced in newspaper reports. Both are preliminary reports that await publication.

The Rakhigarhi data, published in the Economic Times on June 13, 2018, purports to show, in the words of the excavator, V. Shinde, that “the Rakhigarhi human DNA clearly shows a predominant local element… There is some minor foreign element which shows some mixing up with a foreign [Iranian] population… This indicates quite clearly, through archaeological data, that the Vedic era that followed was a fully indigenous period with some external contact.”

Niraj Rai, the genetic specialist of the Rakhigarhi report, echoes this: “skeletons at Rakhigarhi point to a predominantly indigenous culture that voluntarily spread across other areas, not displaced or overrun by an Aryan invasion…It will show that there is no Steppe contribution to the Indus Valley DNA… The Indus Valley people were indigenous, but in the sense that their DNA had contributions from Near-Eastern Iranian farmers mixed with the Indian hunter-gatherer DNA”.

Yet, conversely, he sustains Vagheesh Narasimhan’s May 2018 paper: “A migration into [ancient] India did happen… It is clear now, more than ever before, that people from Central Asia came here and mingled with [local residents]. Most of us, in varying degrees, are all descendants of those people.” Importantly, the R1a genetic marker, typical of the Western Central Asian Steppes, is missing in the Rakhigarhi sample. Rai adds: that “the analysis of the DNA sample will be of a period before [my italics] the Steppe people supposedly arrived in India. If R1a is absent in the Indus Valley sample, it suggests it was brought into South Asia, perhaps by a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) speaking group.” (Obviously, PIE is too early).

Later newspaper reports add more materials and are more balanced. The initial conclusions about “no Aryan invasion” echo the cultural politics of the past 30-odd years and are blatantly weird, as one cannot expect the genetic materials of IA speakers in the Harappan Civilisation: they entered the subcontinent only after its dissolution, or at best, during its final phase around 1300 BC—not at time of the excavated materials, said to be around 2600 BC. We need confirmed dates for the one or two skeletons with recovered aDNA before we can make definite statements about the contemporaneous Indus population, keeping in mind that people moved around during the Harappan period as isotopes indicate. Archaeological data had already revealed that the population was not homogeneous and individuals had moved into Harappa from distant parts of the Greater Indus area (as seen in teeth enamel, etc.).

So, after decades of denial of any migration into India by archaeologists, the pendulum is swinging back to constant contact, migration and population mixture—which would at least allow for the migration of IA speakers into the subcontinent.

Precisely this is maintained in the recent pre-publication of a massive genetic paper by Vagheesh M. Narasimhan et al. According to this study, in the late second millennium BC, a large-scale middle/late Bronze Age Steppe migration entered the Indus periphery, apparently at least in part via the Inner Asian mountain corridor, where up to 30 per cent Steppe DNA is found with the Kalasha in Chitral, in westernmost Pakistan. This movement includes, from 1250 BC onwards, one to the Swat Valley where, for the first time, Indian aDNA has been retrieved. This precisely fits, both in time and space, the migration of the IA speakers of the Rigveda, visible in archaeology and linguistics. These migrants have also left a clear imprint on the genetic setup of the modern Brahmin and Bhumihar population of North India, where Central Asian traits are up to 57 per cent, while with other populations this amounts only to 11 per cent, and it is hardly seen in South India.

Religion, Mythology, Ritual

When comparing the texts on Vedic religion, mythology and ritual with those of the Indus civilisation and of those of the Indo-Iranian and Indo-European ancestors of Vedic culture, it is clear that the Veda is not a continuant of the Indus Civilisation (or even an overlap)—with the possible exception of some low level deities, spirits and demons (kimidin, mura-/shishna-deva) that frequently are isolated linguistically and belong to the Greater Punjab (“Para-Munda”) substrate.

The evidence for Indus mythology (visible on small tablets and some seals) is not reflected at all in the Vedas, and any link with later Hinduism, thousands of years later (championed by Parpola), is a phantasy: for example, the famous “Pashupati” seal reflects a widespread Northern Eurasian deity, the Stone Age Lord of the Animals; likewise, the killing of the buffalo demon Mahisha by a deity, etc., is separated from supposed Hindu continuants by chasms in time and space. Other supposed continuities belong to “low-level” cultural features: the red parting line in married women’s hair, and the Namastegesture, which is found in the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex around 2000 BC, and…in Jomon time Japan, 1900 BC: certainly not the spread of an Indus feature.

In Conclusion

In sum, neither was India ever isolated, nor did all facets of its archaeological, linguistic, textual, genetic/somatic data arise “on their own” locally; instead, they look back to some 60,000 years of Out-of-Africa history. The subcontinent presents a fascinating array of internal developments and external influences that only patient and unbiased study can reveal.

AUG 11, 2018 10:59 AMSRINI KALYANARAMAN

Just three-and-a-half hours due northwest of Delhi, the GPS takes you unerringly to ancient India. Not a mythic world, but one made of bricks dried in an age-old sun. It’s a part of Haryana that can pass, at one glance, for Assam: the wet green of paddy stretches to the flat, misty horizons. Some spans of time are as endless—it boggles the mind, for instance, to think that the duration between the early onset of civilisation and its decline in these parts is longer than what separates us now from Harappa.

Or shall we say, Rakhigarhi.

“The Rakhigarhi samples have a significant amount of ‘Iranian farmer’ ancestry. You won’t find this DNA in the north Indian population today, but only in south Indians,” says Niraj Rai.

Yes, the shift in centre of gravity is as fundamental as that. The Harappan site at Rakhigarhi, in Hisar district, is the biggest one known yet—at up to 550 hectares, it’s more than twice the size of Mohenjodaro. It’s also the one with the deepest time-scale, taking shape at 5500 BC and running for four continuous millennia. The nearby satellite site of Bhirrana, part of this Bronze Age metropolitan network, is even older: it offers the classic arc of evolution, beginning from early Neolithic farming around 7500 BC. Almost 10 millennia ago. Even with India’s endless capacity for imagining deep time, that’s serious depth. On the edge of modern Rakhigarhi village, buffaloes amble out of a pond placidly, unmindful of passing archaeologists or of the runic mysteries glimmering under the undulating mounds.

Decades ago, Wazir Chand would come to these mounds as a dreamy little boy tending to his buffaloes. He started picking up pieces of terracotta bangles, shards of pottery, little bric-a-brac…

UNEARTHING A FARAWAY TIME

Ongoing excavation at a mound in Rakhigarhi

COURTESY: RAKHIGARHI PROJECT

The Rakhigarhi kaleidoscope has been throwing up very interesting patterns of late. Prof Vasant Shivram Shinde, senior archaeologist and vice-chancellor of Deccan College, Pune, is at the centre of action. In February, his years of studying the Rakhigarhi people’s burial practices became the basis of a definitive article published in a Public Library of Science journal. For that, altogether 37 burials from the necropolis area of Rakhigarhi—one of the few Harappan sites where a well-defined cemetery area has been discovered—were subjected to an examination along standard anthropological lines. And now, he is the vital node for two forthcoming papers that may become dramatic, if contentious, landmarks in Harappan studies. The first steps ever by genetic science into the Harappan space, both studies are based on DNA samples taken from those same burials at Rakhigarhi.

- In one, South Korean genetic scientists are trying to reconstruct, for the first time ever, what the Harappans looked like. Expect a Harappan face, or a DNA artist’s impression of it, to be hitting the internet soon.

- The other paper, authored by Niraj Rai, head of the Ancient DNA lab at Lucknow’s Birbal Sahni Institute for Palaeosciences, and co-authored by Harvard geneticist Vagheesh Narasimhan et al, maps the genetic ancestry of the Harappans for the first time ever.

The latter report is due out within a month. Its findings, core elements of which were revealed to Outlook, have all the potential to start a feeding frenzy. The Indus Valley Civilisation, even as an inscrutable self-image, taps deep into the modern Indian imagination. In recent years, it's become a hypersensitive field, riven with claims and counter-claims flying at each other like arrows in a mythological serial. Expect garden variety ideologues and enthusiasts to be going at each other and at bonafide historians, archaeologists and geneticists on Twitter till the much-in-vogue cows come home. (Home? Whose home?)

So Who Were the Harappans?

The answers are now clear. “The sample we are getting is very local,” says Rai, who did the basic work. “We aren’t getting any Central Asian gene flow in Rakhigarhi. Comparing Rakhigarhi with data from modern Indian populations, we have concluded that they have more of an affinity with the Ancestral South Indian tribal population compared to the north Indian population.”

This March, one of the biggest studies on the Central and South Asian population’s genetic ancestry confirmed what is known in politicised terms as the “Aryan migration”.

‘Ancestral South Indian’. The phrase brims with potent cultural overtones, while claiming the startling force of a ‘scientific truth’. Even if, used in this context, it only confirms commonsense notions about the Harappan and Rigvedic cultures being two distinct lines, one replacing or overlaying the other, with elements of both rupture and continuity—and gradual mixing.

The Harappan people didn’t vanish into thin air. Over centuries of being unable to sustain their cities due to growing aridity, as Shinde explains, they “went rural” (see interview). Went back to living a more primary economy. And migrated. And mixed. Their knowledge systems too went into hibernation, Shinde believes, only to resurface in the Indian cultural gene whenever the circumstances became more conducive.

“We still build the same way. Even our bricks are in the ratio they invented—1:2:4 in depth, width and length—even if the size is smaller,” says Dinesh Sheoran, Shinde’s pointsman in Rakhigarhi. He picks up a stray Harappan brick lying atop a kuchha village wall: it's bigger and in good health. No wonder even the British used them, in the 19th century, for railway lines!

SKELETAL HISTORY

Researchers at a burial site in Rakhigarhi

COURTESY: RAKHIGARHI PROJECT

But before asking whether the Harappans indeed live on among us—or which interpretive filter to use while trying to read (and write) history—there are two more stark facts in the genetic data. One comes from the forthcoming paper. “The Rakhigarhi samples have a significant amount of ‘Iranian farmer’ ancestry,” says Rai. “In India’s present-day population, only the south Indians have Iranian farmer ancestry. You won’t find Iranian farmer DNA in the north Indian population.”

Iranian farmer? Yes, this nomenclature owes to studies of early Neolithic farming in the Zagros mountains of Iran—one of the sites in the Fertile Crescent where humanity is said to have first farmed and domesticated animals. At least that’s what the scholarly consensus seems to be. An eastward expansion is then cited as having brought farming and animal domestication to the Indian subcontinent. Along with the people who brought them—a ‘demic’ flow, as they call it—and then proceeded to interbreed with local hunter-gatherer populations to produce the ‘Ancestral South Indian’ type. Of which the Harappans are an instance.

But couldn’t farming have evolved in India—or elsewhere outside the Fertile Crescent—independently? Perhaps. And goats domesticated? Again, yes…even the last big study on Indian goats suggests a story more complex than it happening at Zagros and then spiralling out. But the present study accepts that model: essentially, that the story of ‘civilisation’ began in the Fertile Crescent and spread east. “The first mixing happened around 6000-5000 BC. As the Neolithic (period) started, the Northwest Indian mixed significantly with Iranian farmers,” says Rai.

Harappan terracotta bangles

PHOTOGRAPH BY JITENDER GUPTA

And then: “Central Asian mixing happened only when the Indus Valley collapsed.”

Central Asian mixing? That’s the ‘Aryan’ stuff, and genetic data clearly shows it happened—around or after the cusp offered by the decline of Harappan cultures. In a sense, for all the flux offered in between by highly politicised readings, and all the apprehensions about what modern DNA analysis would show, genetic studies are confirming the basic elements of an ‘Aryan’ migration theory. The key takeaway is that earlier mixing seems to have given us the ‘Ancestral South Indian’ (ASI)—with an ‘Iranian farmer’ component as part of it. And ‘ASI’ later mixed with incoming pastoral people from the Central Asian Steppe, giving us the ‘Ancestral North Indian’ (ANI). ANI is simply ASI + Steppe DNA.

PAST FORWARD

Children at a covered mound in Rakhigarhi

PHOTOGRAPH BY JITENDER GUPTA

The ‘Indo-Aryan’ Debate

By now, the racist overtones sloshing around everywhere simply have to be acknowledged and managed. ‘Aryan’ is a word and concept that played a central role in modern political history. It’s not just Nazi Germany. In 1935, responding to the new cachet the word had acquired, Persia offered itself as ‘Iran’ to the world, as a nod to their 'Aryan' ancestry. In India, the word already had prestige: the 19th century revivalist/reform stream already saw us an 'Arya Samaj' (Aryan Society). And politics in the last three decades has gone along a path that insists Vedic culture came out of a local, native, autochthonous strand—that is, born out of India’s womb—when everything in historical linguistics and archaeology has always strongly suggested the opposite. And now, genetics adds its ballast to what linguistics always knew and archaeology had corroborated.

One of the major advances here came in the spring of 2018. This March, 92 top scientists and researchers from around the world (Shinde and Rai among them) had put their names on one of the biggest studies on the genetic ancestry of the Central and South Asian population. That paper had sampled 612 individuals from diverse groups—carefully chosen ancient samples correlated with modern ones. It confirmed what is known, in loaded and now-politicised terms, as the 'Aryan migration' (the older 'Aryan Invasion Theory' having been refined in scholarship by the 1970s). In technical words, this study called it “large-scale genetic pressure from Steppe groups in the second millennium BC”, showing the “chain of transmission to South Asia”. They found this to be “consistent with archaeological evidence of connections between material culture in the Kazakh middle-to-late Bronze Age Steppe and early Vedic culture in India”. The genetic marker that clinched this connection was the Y chromosome haplogroup R1a (subtype Z93)—“common” in South Asia and “of high frequency” in Bronze Age Steppe DNA. “It’s inherently racist,” says historian Irfan Habib. Adds archaeologist Shereen Ratnagar: “You cannot use genetic data to settle questions of historical linguistics.” Nayanjot Lahiri, another Harappa domain specialist, shares the disdain.

A Harappan toy bull figurine

PHOTOGRAPH BY JITENDER GUPTA

The authors of the March paper say “much of the formation of both the Ancestral South Indians and Ancestral North Indians occurred in the 2nd millennium BC. Thus, the events that formed both the ASI and ANI overlapped (with) the decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation.” The researchers suggest the first admixture between the Iranian agriculturalists and South Asian hunter-gatherers created the ASI, Harappan people among them. Further, around the second millennium BC, the Steppe pastoralists (the ‘Aryans’) intermingled with the Harappan people and others in the northern Indian plains to create the ANI. This is a visualisation that confirms what have by now become popular 'cultural’ notions, so one needs to move carefully—especially if ‘science’ uses apparently technical terms to denote genepools. It needs to be stated that ASI, or the ‘Ancestral South Indian’, is better read as everyone’s ancestor in South Asia—whether Punjabi, Bengali or ‘Madrasi’.

Pointing out that Indo-European is a linguistic, not genetic concept, Habib says, “What they’ve found is not related to the language problem. Language doesn’t necessarily spread through genes.” He mentions the Greek and Turkish populations: genetically inclined to each other, linguistically separated. Ratnagar, who has worked extensively on Harappan sites, too says: “Indo-Iranian languages have no relation to genetics. This kind of claim is an old-fashioned, racial one.”

A Kushan era seal found in Rakhigarhi

PHOTOGRAPH BY JITENDER GUPTA

“The Rakhigarhi people are six feet tall and sharp-featured, just like the modern Haryanvis,” says Shinde, of the ancient Rakhigarhi people. You scan Wazir Chand’s face for…what…traces of R1a/Z93? He’s a Sirohi, a Jat. “Do you know when Jats settled in these parts? They are medieval immigrants…the first mention of the ethnonym pops up no earlier than 7th century AD,” says Prof Ratnagar.

The March paper only confirmed on another axis what had always been held to be indisputably true in linguistics and other sciences. It’s a curious time: the bald tools of genetic science, often feared by historians because of the racist uses they can be put to, are actually confirming the ideas about human movements in history that all of us grew up internalising—till politics caught up. But even the March paper, with all its scale across India, Central and West Asia, did not have access to Harappan data. That’s what the present Rakhigarhi samples give us: a clear binocular view of our genetic past from a very specific time, a cusp period just before the Rigvedic influx.

The present Rakhigarhi samples give us a clear binocular view of our genetic past from a very specific time, a cusp period just before the Rigvedic influx.

So you get a zero-Steppe DNA population in the biggest Harappan site, against which to contrast the picture afterwards. “On the basis of modern-day populations, we analysed about 1,800 samples and we concluded that groups in north India still have significant amounts of Central Asian affinity,” says Rai, of the March paper. That’s just the basic facts. To elaborate lightly, “We did some analysis to figure out the exact date of the admixture. We have prepared a model in which all these stats fit together very tightly and that model suggests the Central Asian admixture happened about 1500-1000 BC…. Significant mixing happened around 1000 BC, also at 800 BC and 600 BC.”

Dravidian Harappa?

So now, Rakhigarhi comes in as a corroborative element to help settle the ‘Aryan’ debate. Not a conclusive one. But a strongly indicative one. Why not conclusive? Because language remains an open question. We don’t know what the Harappan people spoke—whether it was at all even one language! Vast distances are involved, and even today that supports multiple languages—there’s no reason to suppose that wasn’t the case 6,000 years ago. Moreover, Harappan cities were often even internally heterogeneous, just like any modern city. Not to speak of heterogeneity being a reasonable assumption for a network of well-connected cities situated as far apart as modern Afghanistan, northern Punjab, Gujarat and Haryana, with a vast suburban and rural hinterland.

But could they have been speaking 'Dravidian'...one or many, or one among many? That would, prima facie, seem consistent with the genetic data: the data would, in fact, seem to boost even the old claim of Elamo-Dravidian—the idea that Dravidian languages are linked to the ancient Iranian language Elamite. But the fact is, we simply have no idea. Scholars like Asko Parpola and Iravatham Mahadevan have spent their lives trying to decode the Indus script and linking it to the Dravidian thought world. But it has always remained speculative, requiring a leap of faith in the end. This is exactly the issue with mapping genes on to language: it’s a slippery connection.

TREASURE TROVE

Maths teacher Ramesh Chandra with artefacts he found in his field in Rakhigarhi

PHOTOGRAPH BY JITENDER GUPTA

Racism and Other Isms

Our contemporary minds, coloured by modern political events, are almost primed to misread data such as what Rakhigarhi represents. Beyond the Aryan/Dravidian debates, there’s the competitive nationalism we have between India and Pakistan. It’s not a factor in history beyond one century, when we are dealing with a century of centuries, but we are inevitably and constantly in danger of mapping and projecting our current concerns backwards in time. A sighting of Harappa or Mohenjodaro are anyway out of the common Indian’s reach. It’s the easiest situation in which to breed resentment/envy/defiance. (“Our Harappan city is bigger than yours.”)

Even the genetic studies freely use the “Iranian farmer” and “South Asian hunter-gatherer” tropes, almost unmindful of the fact that they are dealing with rich, primitive, pre-scientific categories that will almost inevitably be filled out with cultural/racial notions. Imagining that Neolithic farming at Mehrgarh or Bhirrana emerged from an influx of “Iranian farmers” bringing in 'superior knowledge' seems consistent with current data, but it relies on and shores up ideas that carry a strong cultural freight from times that have nothing to do with the period being studied. We inevitably think of modern nations—and of contemporary Iranians or those from a strongly salient part of Iranian history. But an “Iranian” 10 millennia ago would simply not be the same thing as an Achaemenid: s/he would be part of a different kind of human flux, still to put down roots, still in the process of forging the first links to a specific land. The famous Zagros woman known as GD13a would not be culturally distinguishable from someone in ancient Mehrgarh, in Balochistan, a few days away even in the ancient world. Indeed, they would be a cultural continuum: late Neolithic minds.

Shinde, cognisant of the patterns of evolution of agriculture in pre-Indus sites, agrees with the fallacy of crediting this great civilisation directly to the flow of genes and knowledge from what can be thought of as ‘non-Indian types’ in West Asia. Nations of the Near East and Europe (or China) all have aggressive claims on antiquity, which complicates historical research—being aware of that should ideally free Indian minds from that trap.

Modern Rakhigarhi is in a hesitant dialogue with its remote past. The twin villages Rakhi Khas and Rakhi Shahpur have literally been sitting on history.

Narasimhan, though, seeks to defend genetics against all the racist antecedents: “Ethically, there is nothing inherently different about the work we do when compared with historians or archaeologists,” he says. “I believe human history is the common heritage of all humans, and it’s amazing to be able to study this directly, in a way, for the first time. This technology has not just been employed to understand the peopling of South Asia, but also of the Americas, Europe and Africa. We are also able to understand interaction not just between groups of modern humans, but also the interaction between modern humans and other archaic hominids, such as the Neanderthals.” He obviously has a point there, and the future lies perhaps in greater coordination—and ensuring genetic research is passed through the filters of commonly accepted protocols—not avoidance. That would enable the strong caveats already known from other sciences to be employed—such that genes, race and language cannot be mapped on to each other unless corroborated by other sciences. Just like the slippery link between script and language, populations too have always been known to shift language.

Rakhigarhi: A Cultural Gene

Once the caveats are accounted for, we are left with the complex and fascinating map of a Harappan civilisation—an empire seemingly without kings and armies, a political federation forged across a vast territory of 2 million sq km that achieved a rare unity in terms of planning and coordinated activity for the general weal. A thought world where social stratification did not entail poverty, whose urban systems negated the very ground of caste—and whose gender relations would be a fascinating area of study, judging by the way female bones were buried differently.

Modern Rakhigarhi is in a hesitant dialogue with its remote past. The twin modern villages have literally been sitting on history—Rakhi Khas and Rakhi Shahpur. They are home to between 12,000 and 13,000 people, 65 per cent of them Jats, a few Brahmins, and there’s a Dalit mohalla along the access to two of the mounds, marked by a high frequency of Ambedkar portraits hung up on walls. Babasaheb would have probably loved to intervene in some of these debates.

To those of its residents who have grasped the span and scale of history, it’s not only a matter of pride. They also live off the Harappan site on which they live. It offers them infinite resources to wonder at and harness. Wazir Chand has over the years, of collecting, adoring, possessing, himself become a Rakhigarhi artefact. He was sitting on one of the mounds back in the 1970s when R.S. Bisht, the then Archaeological Survey of India chief, tapped him on the shoulder and changed his life.

Talking to Outlook, the archaeologist reminisces: “I visited Rakhigarhi several times in the 1970s. It had only two known parts until then, but I saw five conspicuous mounds of varying sizes. I said it was one of the five largest cities in the subcontinent.” Bisht later called for a survey of the mounds. “I also found two other mounds just four metres away, clearly pre-Harappan,” he says. “Never before had we found so many mounds except in Harappa. I got it surveyed and protected as a national monument under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act.”

Four decades later, there are not only the thematic disputes in history—over its readings, approaches and conclusions—but also the hum of petty disputes, ownership claims and scams. One day, a non-politicised understanding may become possible. Such a day may have already existed. The Jats of Rakhigarhi have been interacting with Muslims who left these parts for Pakistan over the internet: they are overjoyed to learn they still speak Haryanvi and marry among themselves. They’ve been watching videos of old compatriots lamenting having to leave their home. On the edge of RGR2, the second mound outside the village, Sheoran does a quick ‘mathha teko’ at a mazaar. There are scarcely four or five Muslim families in the village, but everyone reveres the pir. An outer layer of history that, elsewhere, has complicated readings of the deeper layers...it lies untroubled, freshly painted by Hindu devouts, out here in Rakhigarhi.

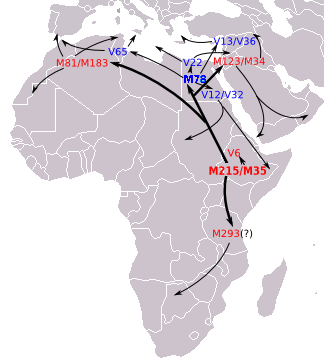

Mapping Ancestry

Migrations affecting ancient Central and South Asian populations (courtesy the March 2018 genome study)

- AASI: South Asian hunter-gatherers, the earliest known inhabitants, are referred to as ‘Ancient Ancestral South Indians’

- ASI: ‘Ancestral South Indians’ emerged from the admixture of AASI with ‘Iranian farmers’

- ANI: ‘Ancestral North Indians’ are the result of admixture of ASI and the Steppe population

- Why Rakhigarhi Upcoming studies from DNA samples of burials from Rakhigarhi will be the first genetic research on the Harappan population. The researches are expected to reveal who the Harappan people were and even how they looked.

Our past is not their charity

Vindicating the Outlook cover story, ‘We are all Harappans’, Harvard philologist Michael Witzel observed that India has seen a number of migrations, including the Aryans - and the Veda was no continuation of Harappan religion (After Meluhha, The Melange, Outlook, August 2, 2018). The Outlook story claimed that the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi in Haryana has roots in the Fertile Crescent of West Asia and exhibits more affinity with Ancestral South Indian Tribal Population.

Rakhigarhi sparked a global controversy in early 2014 when eminent South Asian archaeologists criticised the intervention of foreign lobbies on this crucial archaeological site and funding by an opulent NGO, Global Heritage Fund. Its founder, Jeff Morgan, is a former Silicon Valley entrepreneur. Many eminent Indian archaeologists were taken aback at the NGO intervention and funding at Rakhigarhi.

The Archaeological Survey of India has no dearth of funds and this foreign NGO funding was the first in the history of an Indian archaeological site. Veteran archaeologist, Prof. Dilip Chakrabarti, in Nation First: Essays in the Politics of Ancient Indian Studies (2014), cautioned that, “from now on, there will be increasingly successful attempts to take over Indian archaeology from the Indians, by miscellaneous groups of racially arrogant people masquerading as archaeologists under the umbrella of various foreign NGOs.”

Michael Witzel is jubilant that his Aryan Migration Theory got contextualized at Rakhigarhi under Global Heritage Fund. He claims that the arrival of Indo Aryan speakers in Greater Punjab is heralded by many loanwords derived from the substrate language of this area, the Northern Indus language, which is designated by him as “Para-Munda” (Outlook, August 2, 2018).

In his 1999 paper, Early Sources for South Asian Substrate Languages, Witzel contended that the language of the pre-Rigvedic Indus civilisation, at least in the Punjab, was of a (Para-) Austro-Asiatic nature which shows that Haryana and Uttar Pradesh once had a Para-Munda population acculturated by the Indo-Aryans. Witzel stressed that Vedic, Dravidian and Munda belong to three different language families, Indo-European, Dravidian and Austro-Asiatic. He claims the presence of Dravidian, Mua, and apparently also of Tibeto-Burmese speakers in northern India, up to the borders of Bengal, at the time of the infiltration and spread of Indo-Aryan speakers. Witzel explores Para-Munda loan words in the Rg Veda, Para-Munda and the Indus language of the Punjab, and Munda and Para-Munda names in his assignments for establishing the routes of Aryan migration into India.

Witzel earlier argued vigorously that in Indology, the imperialistic enemy is the “colonial-missionary creation known as the Aryan invasion model” (Frontline, Vol. 17, Issue 20, Sept. 30-Oct. 13, 2000). In 2009, he and his team contended that Hindutva groups propagate that Aryans were the original or indigenous inhabitants of India. It needs to be examined whether the consanguinity between colonial missionaries and Aryan Invasion has been the creation of nationalist historians as alleged by Witzel. This is important as Witzel currently contextualizes Aryan Migration Theory with the Munda population in India. This anthropological survey was launched by the colonial regime in India.

Edwin G. Smith of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain wrote in 1924 that anthropology should be recognized as an essential discipline in the training of missionaries. “Good missionaries have always been good anthropologists,” is the opening line of Eugene Nida’s classic, Customs and Cultures: Anthropology for Christian Missions (1954). Lewis Henry Morgan sent his kinship questionnaire all over the world to missionaries, asking them to fill in the data and send it back to him.

Prof. Peter Pels of Leiden University has discussed the controversial link of missionaries with colonial anthropology. Prof. Thomas R. Trautmann highlights the role of missionaries in fitting India into the tree of nations of the Bible, which he terms mosaic ethnology of the Book of Genesis. Frits Staal argues that there is no evidence for “free Aryans and subjugated indigenous people”. He criticizes the linguists for the ‘unfortunate but continuous’ use of the term Aryan.

Dilip Chakrabarti, one of the foremost authorities in South Asian Archaeology, observes in Nation First that apart from a historical and racial issue, the Aryan invasion has been given socio-political dimensions primarily by Christian missionaries. The role of missionaries in propagating Aryan theory has also been discussed by Prof. Rosalind O’ Hanlon.

The central Indian region extending eastwards up to Bengal and Assam was settled by hunting-gathering and agricultural communities. Mundas, inhabiting a broad belt in central and eastern India, are largely agricultural and hunting-gathering communities. The widest spectrum of Aryan Invasion Theory and the largest collection of anthropological data by the colonial regime began in Central India. The colonial regime entrusted local administration of the region to faithful zamindars after the 1857 rebellion.

The Central Indian region was seen as fertile land by missionaries for helping the colonial regime suppress anti-imperial agitations and for gathering linguistic and ethnological data for conversions. Stephen Hislop, Missionary of the Free Church of Scotland at Nagpur, assisted R.V. Russell in his preparation of castes and tribes of central India. Russel made use of ethnological accounts by Bishop Westcott, Rev. T.P. Hugh, Rev. E.M. Gordon, and Rev. P. Dehon; and juxtaposed Aryan Invasion and the Old Testament.

American Baptist missionary Jeremiah Philips made linguistic studies of the region. Norwegian missionary Lars Olsen Skrefsrud also worked on the linguistics of the region. John Baptist Hoffman, a German Jesuit missionary who worked in Chotanagpur from 1893 to 1915, collected extensive linguistic and ethnological material on the Mundas. He also prepared the Munda Grammar and later the Encyclopaedia Mundarica.

Fr. Peter Tete S.J who did research in 1993 on J.B. Hoffmann for his dissertation at the Gregorian University in Rome, states that before the arrival of the Aryans, there were traces of Munda dialect in the Gangetic plains. Hence it is not surprising that currently Michael Witzel has chosen the same track of research on Mundas, contextualizing them with Aryan migration. In 2016, another missionary Paul B. Steffen, quotes Hoffman that, Mundas are the remains of the original inhabitants of India, who were once driven out by the Aryans into the mountains and had defended themselves for thousands of years from the invaders they hated so much.

More studies were conducted on Mundas by colonial missionaries. Rev. F.A. Grignard S.J. wrote ‘The Oraons and the Mundas - From Time of their Settlement in India’ (1909). Fr. Augustus Stockman did surveys in 1868 from Midnapur to Chaibasa. He discovered that, side by side with the Munda people, there were Oraons who differed considerably from their Munda neighbours in terms of language and character. Anthropologist S.C. Roy, who was considerably influenced by the missionary Verrier Elvin, has written about migrations of the Mundas into the jungles of Chotanagpur, from the attacks of invading Aryans.

‘Dharti Abba’ (Earth Father), the legendary Birsa Munda, stressed the need for Vanvasis to study their own tradition and not forget their cultural roots. He started the faith of ‘Birsait’ which was a threat to Christian missionaries who were converting the tribals (India Today, June 9, 2016). The Anglican Mission at Murhu and the Roman Catholic Mission at Sarwada were the main targets of Munda agitation against colonialism. Michael Witzel currently works on the Mundas, where the colonialists and missionaries conducted an abrupt job.

In the erstwhile Chotanagpur and Central Provinces, Rev. O. Flex (1874), Rev. F. Batseh (1886), Rev. F. Hahn (1898), Rev. A. Grignard (1924) and Rev. C. Bleses (1956) focussed on linguistic and ethnological surveys and studies. Since 1885, survey of Chotanagpur region was also carried out by Jesuit missionaries. Father Van der Schuerin presented a paper (Oct. 1928) on the work of Belgian Jesuit missionaries among the aboriginal tribes of Chotanagpur. Bishop J.W. Picket and Rev. G.H. Singh conducted ethnological studies in Central India and concluded that they were suppressed by Aryans. J.T. Taylor of the Canadian Presbyterian Mission did studies on aborigines in Central India and propagated the Aryan invasion.

In 1883, Richard Temple, once Chief Commissioner of Central Provinces, delivered a speech to the Baptist Missionary Society, London, wherein he exhorted that the tribals (in India) ought to be made the special focus of the exertions of missionaries. In his work ‘Men and events of my time in India’ (1882), Temple mentions missionaries and Bishops in India who were an inspiration to him - Alexander Duff, William Smith, Stephen Hislop, John A Wilson, Bishop Sargent, Bishop Cotton, Daniel Wilson, and Charles Benjamin Leupolt.

Edgar Thurston in Castes and Tribes of Southern India (1909) invites our attention to Sir Alfred Lyall who refers to the gradual brahminisation of the aboriginal non-Aryan or casteless tribes. Data for Thurston was provided by Bishop Whitehead, Rev. A.C. Clayton, Rev. Metz and Bishop Robert Caldwell.

The report to the Foreign Missions Committee of the Free Church of Scotland (1888-89) was made by Rev. Prof. Lindsay, D.D and Rev, J. Fairley Daly B.D. It divides the population of India into Hindus, aboriginal tribes, Muslims, and various miscellaneous sects.

Sir Herbert H. Risley was Director of Ethnography and Census Commissioner. Risley was thrice President of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The anthropometric classification of the Indian people was first attempted in 1901 by Risley in Census of India. It was due to Risley’s initiative that Rev. P. Dehon S.J. compiled his ethnological work on Oraons in Central India. Prof. Sayce, whom Risley cites as having authorized him to address the invaders from northwest India as ‘Aryans’, is Rev. Archibald Henry Sayce, a scholar in Assyriology and Biblical studies.

As biologists V. Tripathy, A. Nirmala, and B.M. Reddy pointed out in 2008, many genetic studies betray “a lack of anthropological insights into Indian population structure as many of the papers have been written by people of non-Anthropology (especially Indian Anthropology) background.”

Eminent physical anthropologists Kenneth A.R. Kennedy, John Lukacs and Brian Hemphill have observed that there is no evidence of “demographic disruption” in North-West India between 4500 and 800 BCE. American biological anthropologist Todd R. Disotell found that migrations into India “did occur, but rarely from western Eurasian populations”. Estonian biologist Toomas Kivisild, with fourteen co-authors from various nationalities, opted for a very remote separation of the two branches, rather than a population movement towards India.

Indian scientists led by Susanta Roychoudhury studied 644 samples of mtDNA and identified a fundamental unity of mtDNA lineages in India, in spite of the extensive cultural and linguistic diversity. Studies by Indian biologist Sanghamitra Sengupta revealed a minor genetic influence of central Asian pastoralists in India. This study also indirectly rejected a Dravidian authorship of the Indus-Sarasvati civilization, since it observed that the data are more consistent with a peninsular origin of Dravidian speakers than a source with proximity to the Indus-Sarasvati Valleys. Prof. Lalji Singh, molecular biologist and former chief of Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, said studies effectively denounce the argument that Dravidians were driven to the peninsula by Aryans who invaded North India.

Witzel neither discusses nor acknowledges any of these genetic or physical anthropological studies, which exhibits a great dichotomy between his Aryan Migration propaganda and historical realities. It clearly exhibits the contempt of western scholars towards versatile Indian scholarship and prestigious institutions. Joan Gero observed (1999) that knowledge about the most splendid sites situated in the poorest countries of the world is controlled by the agendas, funding agencies and cultural institutions of hegemonic regions such as United States and Western Europe. Claire Smith and H. Martin Wobst (2005) highlighted that colonial archaeology is an endeavour which perpetrates values of western cultures and is hence solidly grounded in western ways of knowing the world. Patricia Uberoi and others (2010) caution that Euro-American studies colonize the non-western mind through western categories of thought.

Let’s look at another instance. The archaeological site of Lahurdewa near Gorakhpur in the Ganga Valley provided evidence of domesticated rice belonging to sixth millennia BC. Two American archaeobotanists, S. Weber and D. Duller, questioned its status of domestication in 2006 at a conference in Uttar Pradesh. Their opinion was cited in a website associated Michael Witzel and Steve Farmer. They even cast doubt on the integrity of radiocarbon dating conducted at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany, Lucknow.

Witzel argues that not one clear example of horse bones exists in the Harappan sites and elsewhere in North India before c. 1800 BCE and such ‘horse’ skeletons have not been properly reported from distinct and secure archaeological layers (The Hindu, Mar 05, 2002). Witzel’s central claim was that the horse was unknown in early India prior to the coming of the Aryans and any data that suggested otherwise must be a fabrication. He refuses to analyse the observations on horse remains from major Indus Sarasvati sites by veteran Indian archaeologists such as Professors B.B. Lal, A. Ghosh, S.R. Rao, V.N. Misra, Dilip Chakrabarti, R.S. Bisht and also Sandor Bokonyi from Budapest, and denounces them outright. He claims that these renowned archaeologists are not trained zoologists and palaeontologists to comment on horse bones. But Witzel, who is only a philologist, claims exclusive scholarship to be accepted as the ‘last word’ on archaeology, anthropology, archaeozoology, and all interdisciplinary studies on India.

The controversy on Indus script deserves attention. In the foreword to Bryan K. Wells’ Epigraphic Approaches to Indus Writing, C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky comments how Bryan’s doctoral dissertation was blocked by lobbying in Harvard University. The dissertation committee consisted of Lamberg-Karlovsky, Michael Witzel and Richard Meadow. Witzel, influenced by Steve Farmer, a comparative historian, contended that the Indus script was neither writing nor representative of language. Bryan Wells asserted that Indus script represents writing and its decipherment will help understanding its texts and language. Along with Meadow, Witzel rejected the final draft of Bryan’s dissertation.

Kamala Visweswaran, Michael Witzel, and others accused Hindutva lobbies of propagating the theory that “Aryans” were the original or indigenous inhabitants of India, and that the core essence of Hinduism can be found in the Vedic religion of the Aryans (2009: The Hindutva View of History: Rewriting Textbooks in India and the United States). Yvette Rosser, a scholar who has studied representations of India in American textbooks, called Witzel anti-Hindu. Rosser said the caste system is often one of the main aspects of Hinduism taught in American schools, which distorts true values (The Caravan, April 12, 2016).

At a panel discussion at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion in Denver (November 17, 2001), Edwin Bryant of Columbia University warned against scholars in American Universities who play identity politics with early Indian history. He cautioned against “falling into a kind of uncritical Indological McCarthyism towards those open to reconsidering the established contours of ancient Indian history, irrespective of their motives and backgrounds, and of lumping all challenges into a simplistic, convenient and easily demonized ‘Hindu Nationalist’ category”.

Witzel claims the Dravidians supplanted the Harappan people in Sindh just as Aryans supplanted them in Punjab. He claims the Dravidians migrated south, while the Aryans went east. He proposes a later Dravidian settlement in that area and Maharashtra, before Indo-Aryan speakers introduced the ancestor of modern Sindhi. But Witzel remains unclear as to when the Dravidians moved into the Indus area. Analogous to Witzel, Robert Eric Frykenberg, scholar in south Asian evangelical studies, in Christianity in India - From Beginnings to the Present (2008, Oxford) depicts the migration of Indo Aryans from Central Asia into India. Frykenberg contends that Dravidians who refused to get suppressed by Aryans migrated southwards. Despite difference in areas of study, Witzel and Frykenberg nourish similar methodology and objectives.

In his paper, Early Indian history: Linguistic and textual parameters, Witzel argues that Vedic texts are almost exclusively ritual, like the Psalms of David, accompanied by a priestly explanation of the great Easter sacrifice at the temple of Jerusalem, and by a ritual manual for its priests. This shows Witzel’s lack of understanding of Vedic literature and how he attempts to align it with Abrahamic texts, to trace the routes of Aryan migrations into India. Prof. Stefan Arvidsson has recently discussed various ideological interests that shaped ‘Aryan’, such as the Indo European perceived “creative center” of the Judaeo-Christian dominant strain of Western culture and the Hebrew claim to stand at the “origins of history,” as described in the Bible.

Michael Witzel’s Aryan Migration is deep rooted in Biblical studies. Migration is an intrinsic part of the Abrahamic faith. The migration story is key to Biblical ancestry: the history of the movements of the uprooted ‘People of God’ seeking safety, sanctuary and refuge. It narrates the migration of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, the movement of Abraham out of the Ur of the Chaldeans and continuation to other places, the exile of the Jews to Babylon, the movement of Elimelech and Naomi to Moab. Peter and Paul wrote letters to churches of migrants. Witzel currently endeavours to draft and weave this West Asian migration history into the foundation of ancient Indian studies contextualizing the Aryans.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61662489/511px_David___Napoleon_crossing_the_Alps___Malmaison1.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13220581/9780262038577_cover.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13220591/Rosenberg__Credit__Alex_Rosenberg__2018.jpg)