ANE – Ancient Near East

dhāī˜ 'wisp of fibre in a twisted rope' (Lahnda); rebus: 'one in role of dice'.The circumference of a circle is slightly more than three times as long as its diameter.

a dotted circle + string which signifies dhā̆vaḍ ''iron-smelter' who performs the act of purification to win the wealth, the metal from mere earth and stone -- replicating the immeasurability of cosmic phenomena. This symbol is worn on the fillets of the Mohenjo-daro priest (on his forehead and on his right shoulder).

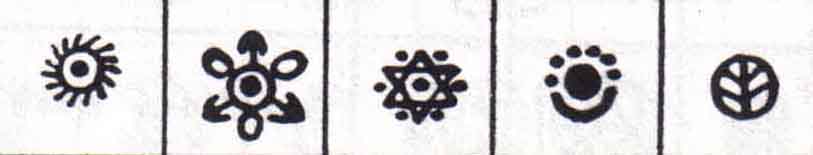

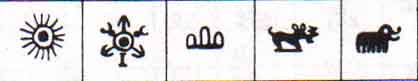

These signs (ASI 1977 Mahadevan corpus) may be semantic variants of the ‘dotted circle+ string’ orthography of Sign 397.

Field Symbol 118 is ‘dotted circle’.![]() Field Symbol figure 123

Field Symbol figure 123![]() These hypertexts are also likely to be related to the orthography (and semantics) of ‘dotted circle + string’. Field Symbol figure 123 is associated with a ‘portable furnace’ indicating the possibility of production of ‘crucible steel’..

These hypertexts are also likely to be related to the orthography (and semantics) of ‘dotted circle + string’. Field Symbol figure 123 is associated with a ‘portable furnace’ indicating the possibility of production of ‘crucible steel’..

Field Symbol figure 123

Field Symbol figure 123 Cross-section view of a strand (say, through a bead), ‘dotted circle’: धातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

Cross-section view of a strand (say, through a bead), ‘dotted circle’: धातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)dula‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’PLUS kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolilmi ‘smithy, forge’. Thus, metal casting forge.

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe' कर्णिक 'steersman, helmsman'

m2089A m2089BC

dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal'PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus bronze/bell-metal workshop.

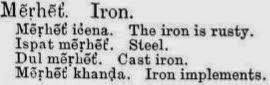

meḍ ‘body’ rebus: mẽṛhẽt ‘metal’,meḍ ‘iron, copper (red ores)’ (Mu. Ho. Slavic) < mr̥du‘iron’ mr̥id‘earth, clay, loam’ (Samskrtam)

m2090dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

m2090dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus bronze/bell-metal workshop.

meḍ ‘body’ rebus: mẽṛhẽt ‘metal’,meḍ ‘iron, copper (red ores)’ (Mu. Ho. Slavic) < mr̥du‘iron’ mr̥id‘earth, clay, loam’ (Samskrtam)

(Deśīnāmamālā)

(Deśīnāmamālā)

(lozenge) Split parenthesis: mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

meḍ ‘body’ rebus: mẽṛhẽt ‘metal’,meḍ ‘iron, copper (red ores)’ (Mu. Ho. Slavic) < mr̥du‘iron’ mr̥id‘earth, clay, loam’ (Samskrtam)

kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal'

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe' कर्णिक 'steersman, helmsman'

PLUS mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'

khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) PLUS kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa'bronze' (Telugu) kharaḍa ‘account day-book’

dāṭu 'cross' rebus: dhatu = mineral (Santali) Hindi. dhāṭnā 'to send out, pour out, cast (metal)' (CDIAL 6771).

m2093kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolilmi ‘smithy, forge’. Thus, metal casting forge.

dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

धातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

m2094m2094A See m2093

m0352Am0352Cm0352Dm0352Em0352F dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

gaṇḍa 'four' rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements' rebus: kaṇḍa 'fire-altar'

m2112adula‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’ PLUS muh’ingot’ PLUS धातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop' PLUS meḍ ‘body’ rebus: mẽṛhẽt ‘metal’,meḍ ‘iron, copper (red ores)’ (Mu. Ho. Slavic) < mr̥du‘iron’ mr̥id‘earth, clay, loam’ (Samskrtam)

(Deśīnāmamālā)

(Deśīnāmamālā)

kāru pincers, tongs. Rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith'

kolom‘three’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’

kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus bronze/bell-metal workshop.

m2113ABDधातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

m2113ABDधातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)dāṭu 'cross' rebus: dhatu = mineral (Santali) Hindi. dhāṭnā 'to send out, pour out, cast (metal)' (CDIAL 6771).

dula ‘duplicated’ rebus; dul ‘metal casting’ PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe' कर्णिक 'steersman, helmsman'

bhaṭā 'warrior' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'

kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) cf. āra-kūṭa, 'brass' Old English ār 'brass, copper, bronze' Old Norse eir 'brass, copper', German ehern 'brassy, bronzen'. kastīra n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. 2. *kastilla -- .1. H. kathīr m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; G. kathīr n. ʻ pewter ʼ.2. H. (Bhoj.?) kathīl, °lā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; M. kathīl n. ʻ tin ʼ, kathlẽ n. ʻ large tin vessel ʼ(CDIAL 2984) कौटिलिकः kauṭilikḥकौटिलिकः 1 A hunter.-2 A blacksmith PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’. Thus, bronze castings.

m1654A ivory cubem1654B ivory cube m1654D ivory cube dhāˊtu'strand' Rebus: mineral: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773).

m1654A ivory cubem1654B ivory cube m1654D ivory cube dhāˊtu'strand' Rebus: mineral: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773). Ivory counters. Mohenjo-daro. The hypertexts signify creation of hard alloys from mineral ores. Hieroglyphs: karaṇḍa'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा[karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

Ivory counters. Mohenjo-daro. The hypertexts signify creation of hard alloys from mineral ores. Hieroglyphs: karaṇḍa'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा[karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) dhāˊtu'strand' Rebus: mineral: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773).

Ivory rod, ivory plaque with dotted circles. Mohenjodaro. [Musee National De Arts Asiatiques Guimet, 1988-1989, Les cites oubliees de l’Indus Archeologie du Pakistan.]

m1951a Hieroglyph: dhāˊtu'strand' Rebus: mineral: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773).

m1951a Hieroglyph: dhāˊtu'strand' Rebus: mineral: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773).Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrowʼ(CDIAL 3023) rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'.

a

a 'one' rebus: ko

'workshop'

kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) cf. āra-kūṭa, 'brass' Old English ār 'brass, copper, bronze' Old Norse eir 'brass, copper', German ehern 'brassy, bronzen'. kastīra n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. 2. *kastilla -- .1. H. kathīr m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; G. kathīr n. ʻ pewter ʼ.2. H. (Bhoj.?) kathīl, °lā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; M. kathīl n. ʻ tin ʼ, kathlẽ n. ʻ large tin vessel ʼ(CDIAL 2984) कौटिलिकः kauṭilikḥ

कौटिलिकः 1 A hunter.-2 A blacksmith PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’. Thus, bronze castings.

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe' कर्णिक 'steersman, helmsman' PLUS sal‘splinter’ rebus: sal‘workshop’

khaṇḍa 'division'. rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'

dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) cf. āra-kūṭa, 'brass' Old English ār 'brass, copper, bronze' Old Norse eir 'brass, copper', German ehern 'brassy, bronzen'. kastīra n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. 2. *kastilla -- .1. H. kathīr m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; G. kathīr n. ʻ pewter ʼ.2. H. (Bhoj.?) kathīl, °lā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; M. kathīl n. ʻ tin ʼ, kathlẽ n. ʻ large tin vessel ʼ(CDIAL 2984) कौटिलिकः kauṭilikḥ

कौटिलिकः 1 A hunter.-2 A blacksmith PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’. Thus, bronze castings.

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe' कर्णिक 'steersman, helmsman' PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon) rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'.

(lozenge) Split parenthesis: mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus, ingot forge.

adar‘harrow’ rebus: aduru‘native metal’

ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' (R̥gveda)

dhāi 'strand' (R̥gveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a guild of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolilmi ‘smithy, forge’

dhāi 'strand' (R̥gveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

sal ‘splinter’ rebus: sal ‘workshop’

kāru pincers, tongs. Rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith'

dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul‘metal casting’ PLUS dhāḷ 'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'ingot' PLUS kolom ‘three’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’

m1648shell dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

m1648shell dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)m1684a Field symbol: kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. sãgaḍa (double-canoe, catamaran) Hence, smith guild.

Meaning, artha of inscription: Trade (and metalwork wealth production) of kōnda sangara 'metalwork engraver'... PLUS (wealth categories cited.)

koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'

dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'; dhāvḍā 'smelter'

kolmo‘rice plant’ rebus: kolilmi ‘smithy, forge’.

m1744 Field symbol: kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. sãgaḍa (double-canoe, catamaran) Hence, smith guild.

m1744 Field symbol: kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. sãgaḍa (double-canoe, catamaran) Hence, smith guild.Meaning, artha of inscription: Trade (and metalwork wealth production) of kōnda sangara 'metalwork engraver'... PLUS (wealth categories cited.)

aya, ayo'fish' rebus: aya'iron'ayas'metal' PLUS adaren 'lid' rebus: aduru'unsmelted metal'

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’

aDaren,'lid' Rebus: aduru 'native unsmelted metal'.PLUS dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'; dhāvḍā 'smelter'

dāṭu 'cross' rebus: dhatu = mineral (Santali) Hindi. dhāṭnā 'to send out, pour out, cast (metal)' (CDIAL 6771) PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon) rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'.

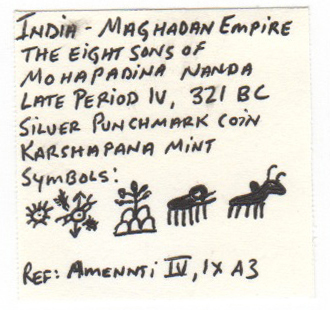

kamaḍha 'archer, bow' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'

khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) PLUS kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa 'bronze' (Telugu) kharaḍa ‘account day-book’

m1744 Field symbol: kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. sãgaḍa (double-canoe, catamaran) Hence, smith guild.

m1744 Field symbol: kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. sãgaḍa (double-canoe, catamaran) Hence, smith guild.Meaning, artha of inscription: Trade (and metalwork wealth production) of kōnda sangara 'metalwork engraver'... PLUS (wealth categories cited.)

aya, ayo'fish' rebus: aya'iron'ayas'metal' PLUS adaren 'lid' rebus: aduru'unsmelted metal'

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’

a

aren,'lid' Rebus: aduru 'native unsmelted metal'.PLUS dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'; dhāvḍā 'smelter'

dāṭu 'cross' rebus: dhatu = mineral (Santali) Hindi. dhāṭnā 'to send out, pour out, cast (metal)' (CDIAL 6771) PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon) rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'.

kamaḍha 'archer, bow' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'

khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati) PLUS kāmsako, kāmsiyo = a large sized comb (G.) Rebus: kaṁsa 'bronze' (Telugu) kharaḍa ‘account day-book’

m1916a Field symbol: kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Telugu) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Telugu) कोल्हा[ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [kōlhēṃ] A jackal (Marathi) Rebus: kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, iron smelters speaking a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali) kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil)

m1916a Field symbol: kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Telugu) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Telugu) कोल्हा[ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [kōlhēṃ] A jackal (Marathi) Rebus: kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, iron smelters speaking a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali) kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil)adaren 'lid' rebus: aduru'unsmelted metal' PLUS dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'; dhāvḍā 'smelter' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus sal 'workshop'

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ PLUS meḍ ‘body’ rebus: mẽṛhẽt ‘metal’,meḍ ‘iron, copper (red ores)’ (Mu. Ho. Slavic) < mr̥du‘iron’ mr̥id‘earth, clay, loam’ (Samskrtam)

(Deśīnāmamālā)

(Deśīnāmamālā)

śrētrī ʻladderʼ rebus: seṭṭha 'guild-master'

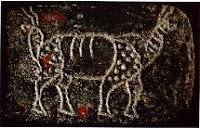

m1120 2362

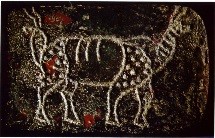

m1120 2362  Field symbol: पोळ [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. पोळी [ pōḷī ] dewlap. पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'zebu, bos indicus taurus' rebus: पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'magnetite, ferrite ore: Fe3O4'

Field symbol: पोळ [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. पोळी [ pōḷī ] dewlap. पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'zebu, bos indicus taurus' rebus: पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'magnetite, ferrite ore: Fe3O4' aren,'lid' Rebus: aduru 'native unsmelted metal' PLUS dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a guild of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

kāru pincers, tongs. Rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith' PLUS dula ‘duplicated’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’

kanka, karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, scribe' कर्णिक 'steersman, helmsman'

m1688a Field symbol: kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. sãgaḍa (double-canoe, catamaran) Hence, smith guild.

m1688a Field symbol: kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. sãgaḍa (double-canoe, catamaran) Hence, smith guild.Meaning, artha of inscription: Trade (and metalwork wealth production) of kōnda sangara 'metalwork engraver'... PLUS (wealth categories cited.)

ranku‘liquid measure’ rebus: ranku‘tin’

kolom'three' rebus: kolimi'smithy, forge'.

mēṭu 'height, eminence, hillock' rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) PLUS kolom ‘thricee’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’

Circumscript dula‘two’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’ PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon) rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'

ayo, aya'fish' rebus: aya'iron'ayas'metal alloy' (R̥gveda)

dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773) PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'

bicha 'scorpion' Rebus: bica 'hematite, sandstone ferrite ore' PLUS PLUS मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick) Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Semantic determinant)

kamaḍha 'archer, bow' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage’

m1688a Field symbol: kõda ‘young bull-calf’. Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. sangaḍa ‘lathe, furnace’. Rebus: samgara ‘living in the same house, guild’. sãgaḍa (double-canoe, catamaran) Hence, smith guild.

Meaning, artha of inscription: Trade (and metalwork wealth production) of kōnda sangara 'metalwork engraver'... PLUS (wealth categories cited.)

ranku‘liquid measure’ rebus: ranku‘tin’

kolom'three' rebus: kolimi'smithy, forge'.

mēṭu 'height, eminence, hillock' rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) PLUS kolom ‘thricee’ rebus: kolimi‘smithy, forge’

Circumscript dula‘two’ rebus: dul ‘metal casting’ PLUS खांडा khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon) rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'

ayo, aya'fish' rebus: aya'iron'ayas'metal alloy' (R̥gveda)

dhāi 'strand' (Rigveda) tri- dhāu 'three strands' rebus: dhāu 'red ore'. त्रिधातुः (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- ferrite ores PLUS copper ore M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron-- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(CDIAL 6773) PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'

bicha 'scorpion' Rebus: bica 'hematite, sandstone ferrite ore' PLUS PLUS मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick) Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Semantic determinant)

kamaḍha 'archer, bow' Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage’

Read on...https://tinyurl.com/y8se5as6

"

"

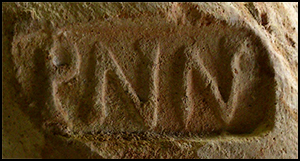

One more of these very early Taxila "śatamāna bent bar" coins, seen from all angles (length 11.3mm / 0.44 inches; weight 11.25 gm (100 ratti)

One more of these very early Taxila "śatamāna bent bar" coins, seen from all angles (length 11.3mm / 0.44 inches; weight 11.25 gm (100 ratti) A "bent bar"śatamāna from the Kuru and Panchala janapada, c.500-350 BCE

A "bent bar"śatamāna from the Kuru and Panchala janapada, c.500-350 BCE A silver 1/8 Kārshāpaṇa coin from Taxila, in the Gandhara janapada, 400's BCE

A silver 1/8 Kārshāpaṇa coin from Taxila, in the Gandhara janapada, 400's BCE

5.70 gms.

5.70 gms.  6.82 gms.

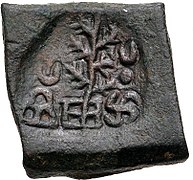

6.82 gms.  3.35 gms. Punch Marked Silver Karshapana Coin of Maghada Janapada. "Punch Marked Coins, Maghada Janapada, Silver Karshapana, Obv: sun, armed wheel, elephant, cow, three arched hill tree railing of different style, Rev: several punch marks, 3.35g, 19.51x15.96mm"

3.35 gms. Punch Marked Silver Karshapana Coin of Maghada Janapada. "Punch Marked Coins, Maghada Janapada, Silver Karshapana, Obv: sun, armed wheel, elephant, cow, three arched hill tree railing of different style, Rev: several punch marks, 3.35g, 19.51x15.96mm" A silver karshapana from Magadha, c.300's BCE

A silver karshapana from Magadha, c.300's BCE Vidarbha Janapada, 400-350 BCE, Half Kārshāpaṇa, 1.60g, ABCC type Obv:

Vidarbha Janapada, 400-350 BCE, Half Kārshāpaṇa, 1.60g, ABCC type Obv:

15.52 gms. 1/2 Kārshāpaṇa

15.52 gms. 1/2 Kārshāpaṇa  3.41 gms.

3.41 gms. A very early silver Kārshāpaṇa coin, with many punchmarks, from the Magadha janapada (c.500's-400's BCE)

A very early silver Kārshāpaṇa coin, with many punchmarks, from the Magadha janapada (c.500's-400's BCE) Magadha. Kārshāpaṇa. ca. 350 BCE.

Magadha. Kārshāpaṇa. ca. 350 BCE.

2.83 gms.

2.83 gms. Taxila. 2nd cent.BCE. 2.08 gms. MAC ---, MIG 583 1/4

Taxila. 2nd cent.BCE. 2.08 gms. MAC ---, MIG 583 1/4  8.9 gms. Kārshāpaṇa "

8.9 gms. Kārshāpaṇa "

1/2

1/2  Taxila. ca. 185 to 168 BCE

Taxila. ca. 185 to 168 BCE 1/2 Kārshāpaṇa. Surasena Janapada.

1/2 Kārshāpaṇa. Surasena Janapada. 1/4 Kārshāpaṇa

1/4 Kārshāpaṇa

Triratna

Triratna

ISLANDS off ATTICA, Aegina. Circa 550-530/25 BC. AR Stater (20mm, 12.31 g). Sea turtle, head in profile, with thick collar and row of dots down its back / Deep incuse square of proto-“Union Jack” pattern with eight incuse segments. Meadows, Aegina, Group Ib; Milbank Period I; HGC 6, 425; SNG Copenhagen –; Dewing 1654; Gillet –; Jameson 1198; Pozzi 1618. Near EF, lightly toned. Well centered and struck on a broad flan. Exceptional for issue.

ISLANDS off ATTICA, Aegina. Circa 550-530/25 BC. AR Stater (20mm, 12.31 g). Sea turtle, head in profile, with thick collar and row of dots down its back / Deep incuse square of proto-“Union Jack” pattern with eight incuse segments. Meadows, Aegina, Group Ib; Milbank Period I; HGC 6, 425; SNG Copenhagen –; Dewing 1654; Gillet –; Jameson 1198; Pozzi 1618. Near EF, lightly toned. Well centered and struck on a broad flan. Exceptional for issue.

m1529

m1529 m1534

m1534 m1534

m1534

The meaning of the expression colossochelys atlas is:

The meaning of the expression colossochelys atlas is:

m1491A copper tablet Harappa Script Corpora

m1491A copper tablet Harappa Script Corpora Mohenjo-daro Seals m1118 and Kalibangan 032 (with fish and arrow hieroglyph)

Mohenjo-daro Seals m1118 and Kalibangan 032 (with fish and arrow hieroglyph)

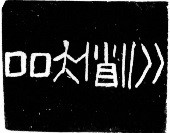

m1406 Mohenjo-daro seal. Hieroglyphs: thread of three stands

m1406 Mohenjo-daro seal. Hieroglyphs: thread of three stands  m1521A copper tablet. Harappa Script Corpora

m1521A copper tablet. Harappa Script Corpora

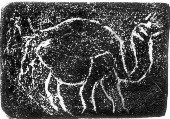

Sunga 185-75 BCE karabha'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

Sunga 185-75 BCE karabha'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

Kausambi 200 BCE

Kausambi 200 BCE kola 'tiger' rebus: kol'blacksmith' karabha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

kola 'tiger' rebus: kol'blacksmith' karabha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

Taxila. Pushkalavati 185-160 BCE Karshapana

Taxila. Pushkalavati 185-160 BCE Karshapana Kalinga. Copper punch-marked 3rd cent. BCEarka 'sun' rebus: arka 'copper gold'

Kalinga. Copper punch-marked 3rd cent. BCEarka 'sun' rebus: arka 'copper gold'

Silver punch-marked

Silver punch-marked Asmaka

Asmaka

Vidarbha janapada

Vidarbha janapada

Roman steelyard balance from Pompeii

Roman steelyard balance from Pompeii

Carved in the prayer hall of Bhaja caves. Four 'fish-fin' hypertexts PLUS two

Carved in the prayer hall of Bhaja caves. Four 'fish-fin' hypertexts PLUS two

"

" VIETNAM, anonymous, late 19-early 20th c.,

VIETNAM, anonymous, late 19-early 20th c.,  Annam (Burma).

Annam (Burma).

Silver bowl. Burma. H

Silver bowl. Burma. H

Arakan state also used the 'srivatsa' hypertext on ancient coins.

Arakan state also used the 'srivatsa' hypertext on ancient coins.

The Golden Chersonese - details from the eleventh map of Asia (southeast Asia). Details from Nicolaus Germanus's 1467 copy of a map from Ptolemy's Geography, showing the Golden Chersonese, i.e. the Malay Peninsula. The horizontal line represents the Equator, which is misplaced too far north due to its being calculated from the Tropic of Cancer using the Ptolemaic degree, which is only five-sixths of a true degree.

The Golden Chersonese - details from the eleventh map of Asia (southeast Asia). Details from Nicolaus Germanus's 1467 copy of a map from Ptolemy's Geography, showing the Golden Chersonese, i.e. the Malay Peninsula. The horizontal line represents the Equator, which is misplaced too far north due to its being calculated from the Tropic of Cancer using the Ptolemaic degree, which is only five-sixths of a true degree. Jambu fruit or Syzygium cumini

Jambu fruit or Syzygium cumini

Malacca plant and fruit. Malacca gets its name from

Malacca plant and fruit. Malacca gets its name from

Crucible steel button.

Crucible steel button.

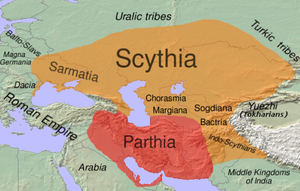

Map showing the main sites of Middle Asia in the third millennium BC (whorls indicate the presence of Indus and Indus-likeseals bearing multiple heads of different animals arranged in whirl-like motif). "

Map showing the main sites of Middle Asia in the third millennium BC (whorls indicate the presence of Indus and Indus-likeseals bearing multiple heads of different animals arranged in whirl-like motif). " Jiroft. Vase. Basket-shaped wallet.

Jiroft. Vase. Basket-shaped wallet.

Stairs of Konar Sandal Ziggurat The main part of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat of the Jiroft ancient site, located in the southern Iranian province of Kerman, has recently been excavated, the Persian service of CHN reported on Friday.

Stairs of Konar Sandal Ziggurat The main part of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat of the Jiroft ancient site, located in the southern Iranian province of Kerman, has recently been excavated, the Persian service of CHN reported on Friday.

Drawing of the animals carved on the cylinder seal found at Konar Sandal South.

Drawing of the animals carved on the cylinder seal found at Konar Sandal South. Figurine of zebu, humped bull discovered in Binjor 4MSR

Figurine of zebu, humped bull discovered in Binjor 4MSR