https://tinyurl.com/y9m323w8

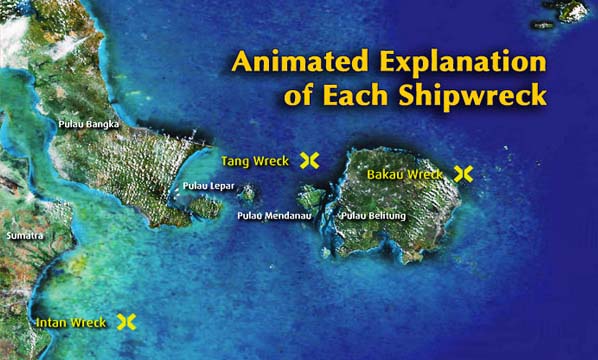

What is the Meluhha word to signify the Amaravati pillar, an Indus Script hypertext?

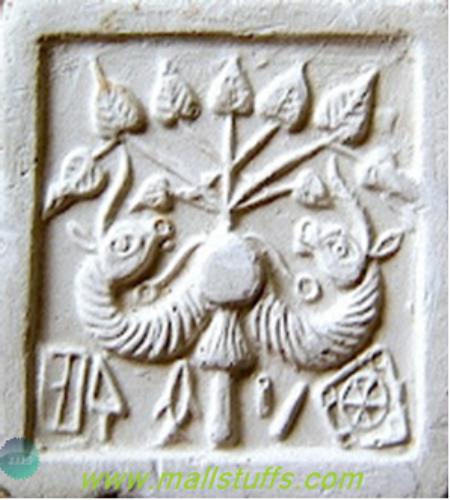

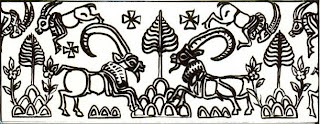

Śrīvatsa khambhaṛā, paṭṭaḍi, phaḍā 'smithy, forge, mint, metals manufactory for wealth'.![Related image]() Worshippers of a fiery pillar, Amaravati stupa.

Worshippers of a fiery pillar, Amaravati stupa.

श्री--वत्स [p= 1100,1] m. " favourite of श्री " N. of विष्णु L.a partic. mark or curl of hair on the breast of विष्णु or कृष्ण (and of other divine beings ; said to be white and represented in pictures by a symbol resembling a cruciform flower) MBh. Ka1v. &c; the emblem of the tenth जिन (or विष्णु's mark so used) L.

श्री śrī:-वत्सः 1 an epithet of Viṣṇu.-2 a mark or curl of hair on the breast of Viṣṇu; प्रभानुलिप्त- श्रीवत्सं लक्ष्मीविभ्रमदर्पणम् R.1.1.-

Atharva Veda (X.8.2) declares that Heaven and Earth stand fast being pillared apart by the pillar. Like the pillar, twilight of the dawn and dusk split apart the originally fused Heaven and Earth.

Light of dawn ‘divorces the coterminous regions – Sky and Earth – and makes manifest the several worlds. (RV VII.80; cf. VI.32.2, SBr. IV 6.7.9).

‘Sun is spac, for it is only when it rises that the world is seen’ (Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana I.25.1-2). When the sun sets, space returns into the void (JUB III.1.1-2).

Indra supports heavn and earth by ‘opening the shadows with the dawn and the sun’. (RV I.62.5). He ‘extends heaven by the sun; and the sun is the prp whereby he struts it.’ (RV X.111.5).

‘He who knows the Brahman in man knows the Supreme Being and he who knows the Supreme Brahman knows the Stambha’. (AV X. 7.17).

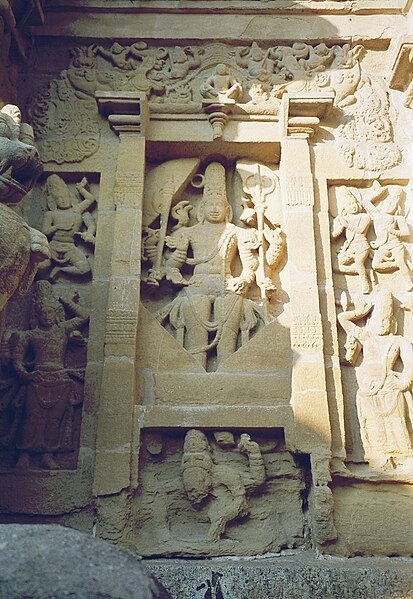

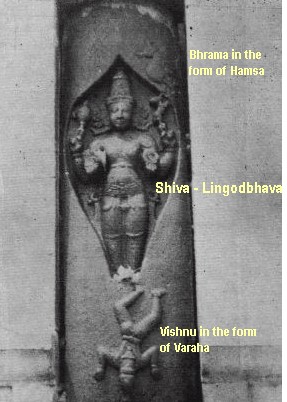

Linga-Purana (I.17.5-52; 19.8 ff.) provides a narrative. Siva appeared before Brahma and Vishnu as a fiery linga with thousands of flames. As a Goose, Brahma attempted to fly to the apex of the column; Vishnu as a Boar plunged through the earth to find the foot of the blazing column. Even after a thousand years, they couldn’t reach the destination, bow in homage to the Pillar of the Universe as the Paramaatman.

He is the ‘Pillar supporting the kindreds, that is, gods and men’. (RV I.59.1-2). He is the standard (ketu) of the yajna (equivalent of the dawn), the standard which supports heaven in the East at daybreak. (RV I.113.19; III.8.8).

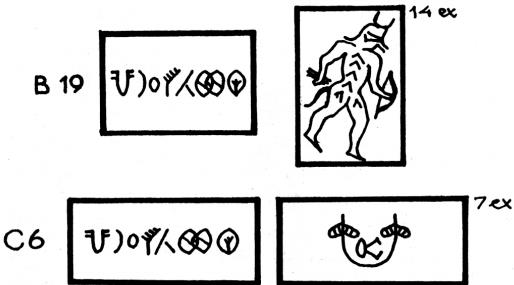

The same spectra of meanings abound in Bauddham, as a symbolic continuum. So it is, the Buddha is a fiery pillar, comprising adorants at the feet marked with the Wheel of Dharma and the apex marked by a Śrīvatsa (pair of fishes tied together by a thread, read as hieroglyph composition: ayira (metath. ariya) dhama, mandating norms of social, interpersonal conduct). Just as Agni awakens at dawn, the Buddha is the awakened.

Male devotees around a throne with a turban(note feet below the throne). paṭa 'throne, turban' PLUS aḍi 'feet' rebus: paṭṭaḍi 'mint workshop'.

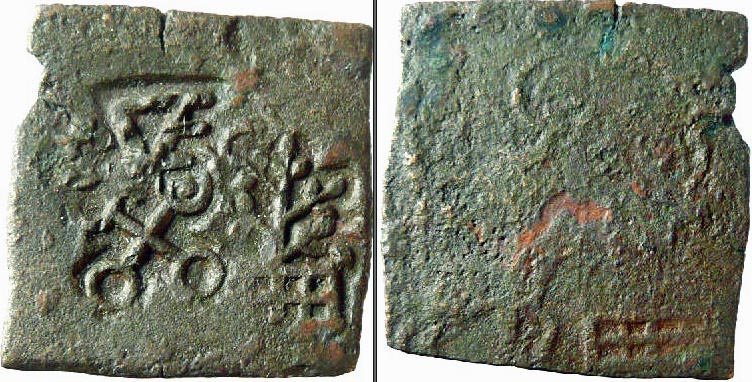

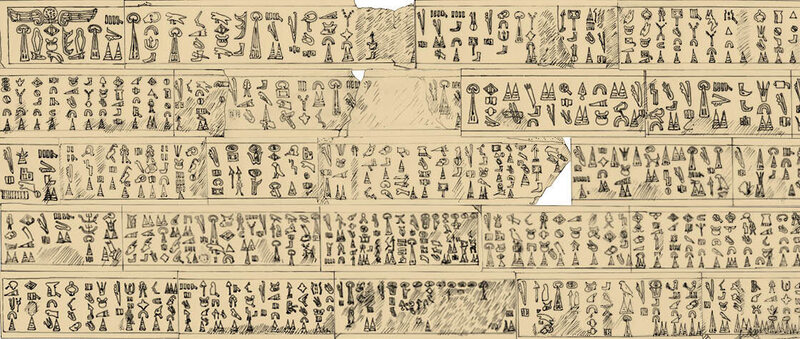

Drawing of two medallions (perhaps the inner and outer face of the same piece). [WD1061, folio 45]

Copyright © The British Library Board

Inscribed:3ft. by 3ft.2in. Outer circle 2nd. H.H. March 8th 1817.

Copyright © The British Library Board

Inscribed:3ft. by 3ft.2in. Outer circle 2nd. H.H. March 8th 1817.

Location of Sculpture: Unknown.

The hypertexts are: kambha 'pillar' PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' pair atop rebus: aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' PLUS kammaṭa 'mint,l coiner, coinage' PLUS feet PLUS throne, turban: ayo kammaṭa 'metal mint' PLUS paṭa aḍi 'throne, turban, slab' PLUS 'anvil' = hypertext, paṭṭaḍi 'metal anvil workshop'.

ayo kammaṭa dvāra 'entrance to metal mint' is an expression used in Mahāvamsa. XXV, 28,

The expression has been wrongly translated as iron-studded gate. It is indeed a reference to the entrance to metal mjint workshop, as signified by the 'Śrīvatsa' ayo kammaṭa hypertext adorning the torana of the gateways of Bharhut and Sanchi.

khambhā, thãbharā, khambhaṛā 'pillar, fish-fin' rebus tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper' rebus kammaṭa 'mint' kambāra 'blacksmith'. These are Bronze Age Indus Script hypertexts.

Four streams of Indus Script cipher on hieroglyphs/hypertexts are seen in the following rebus readings; the streams are:

tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper'

kambāra 'blacksmith'

kammaṭa 'mint'

Itihāsa of Bhārata bronze-age, ayo kammaṭa dvāra, 'metals mint workshop entrance' (Mahāvamsa. XXV, 28); paṭṭaḍi 'metal anvil workshop' based on Amaravati, Bharhut, Begram, Sanchi, Bodh Gaya ancient sculptural friezes (ca. 3rd cent. BCE), Indus Script (4th millennium BCE) & Atharva Veda Skambha Sukta(AV X.7)(undated, Bronze_Age).

The monograph demonstrates the signifiers of two Indus Script hypertexts on iconographs of Amaravati, Bharhut, Sanchi sculptural friezes.

The hypertexts are:

ayo kammaṭa dvāra, 'entrance mint workshop'

The monograph demonstrates the signifiers of two Indus Script hypertexts on iconographs of Amaravati, Bharhut, Sanchi sculptural friezes.

The hypertexts are:

ayo kammaṭa dvāra, 'entrance mint workshop'

paṭṭaḍi 'metal anvil workshop'.

See:

paṭṭaḍi cognate phaḍā 'smithy, metals manufactory' is cognate phaḍā 'metals manufactory'

Hieroglyph: फडा (p. 313) phaḍā f (फटा S) The hood of Coluber Nága &c. Ta. patam cobra's hood. Ma. paṭam id. Ka. peḍe id. Te. paḍaga id. Go. (S.) paṛge, (Mu.) baṛak, (Ma.) baṛki, (F-H.) biṛki hood of serpent (Voc. 2154). / Turner, CDIAL, no. 9040, Skt. (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā- id. For IE etymology, see Burrow, The Problem of Shwa in Sanskrit, p. 45.(DEDR 47) Rebus: phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office’, keeper of all accounts, registers.

फडपूस (p. 313) phaḍapūsa f (फड & पुसणें) Public or open inquiry. फडफरमाश or स (p. 313) phaḍapharamāśa or sa f ( H & P) Fruit, vegetables &c. furnished on occasions to Rajas and public officers, on the authority of their order upon the villages; any petty article or trifling work exacted from the Ryots by Government or a public officer.

பட்டரை¹ paṭṭarai , n. See பட்டறை¹. (C. G . 95.) பட்டறை¹ paṭṭaṟai , n. < பட்டடை¹. 1. See பட்டடை, 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 12, 14. 2. Machine; யந்திரம். 3. Rice-hulling machine; நெல்லுக் குத்தும் யந்திரம். Mod. 4. Factory; தொழிற்சாலை. Mod. 5. Beam of a house; வீட்டின் உத்திரம். 6. Wall of the required height from the flooring of a house; வீட்டின் தளத்திலிருந்து எழுப்ப வேண்டும் அளவில் எழுப்பிய சுவர். வீடுகளுக்குப் பட்டறை மட்டம் ஒன்பதடி உயரத்துக்குக் குறை யாமல் (சர்வா. சிற். 48). பட்டறை² paṭṭaṟai , n. < K. paṭṭale. 1. Community; சனக்கூட்டம். 2. Guild, as of workmen; தொழிலாளர் சமுதாயம். (Tamil)

Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236)

skabha 13638 *skabha ʻ post, peg ʼ. [√skambh]Kal. Kho. iskow ʻ peg ʼ BelvalkarVol 86 with (?).

SKAMBH ʻ make firm ʼ: *skabdha -- , skambhá -- 1, skámbhana -- ; -- √*chambh.

skambhá 13639 skambhá1 m. ʻ prop, pillar ʼ RV. 2. ʻ *pit ʼ (semant. cf. kūˊpa -- 1). [√skambh]1. Pa. khambha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ; Pk. khaṁbha -- m. ʻ post, pillar ʼ; Pr. iškyöp, üšköb ʻ bridge ʼ NTS xv 251; L. (Ju.) khabbā m., mult. khambbā m. ʻ stake forming fulcrum for oar ʼ; P. khambh, khambhā, khammhā m. ʻ wooden prop, post ʼ; WPah.bhal. kham m. ʻ a part of the yoke of a plough ʼ, (Joshi)khāmbā m. ʻ beam, pier ʼ; Ku. khāmo ʻ a support ʼ, gng. khām ʻ pillar (of wood or bricks) ʼ; N. khã̄bo ʻ pillar, post ʼ, B. khām, khāmbā; Or. khamba ʻ post, stake ʼ; Bi. khāmā ʻ post of brick -- crushing machine ʼ, khāmhī ʻ support of betel -- cage roof ʼ, khamhiyā ʻ wooden pillar supporting roof ʼ; Mth. khāmh,khāmhī ʻ pillar, post ʼ, khamhā ʻ rudder -- post ʼ; Bhoj. khambhā ʻ pillar ʼ, khambhiyā ʻ prop ʼ; OAw. khāṁbhe m. pl. ʻ pillars ʼ, lakh. khambhā; H. khāmm. ʻ post, pillar, mast ʼ, khambh f. ʻ pillar, pole ʼ; G. khām m. ʻ pillar ʼ, khã̄bhi, °bi f. ʻ post ʼ, M. khã̄b m., Ko. khāmbho, °bo, Si. kap (< *kab); -- Xgambhīra -- , sthāṇú -- , sthūˊṇā -- qq.v.2. K. khambürü f. ʻ hollow left in a heap of grain when some is removed ʼ; Or. khamā ʻ long pit, hole in the earth ʼ, khamiā ʻ small hole ʼ; Marw. khã̄baṛoʻ hole ʼ; G. khã̄bhũ n. ʻ pit for sweepings and manure ʼ. Garh. khambu ʻ pillar ʼ.

skambha 13640 *skambha2 ʻ shoulder -- blade, wing, plumage ʼ. [Cf. *skapa -- s.v. *khavaka -- ]S. khambhu, °bho m. ʻ plumage ʼ, khambhuṛi f. ʻ wing ʼ; L. khabbh m., mult. khambh m. ʻ shoulder -- blade, wing, feather ʼ, khet. khamb ʻ wing ʼ, mult. khambhaṛā m. ʻ fin ʼ; P. khambh m. ʻ wing, feather ʼ; G. khā̆m f., khabhɔ m. ʻ shoulder ʼ.

skambhaghara 13641 *skambhaghara ʻ house of posts ʼ. [skambhá -- 1, ghara -- ]B. khāmār ʻ barn ʼ; Or. khamāra ʻ barn, granary ʼ: or < *skambhākara -- ?13641a †skámbhatē Dhātup. ʻ props ʼ, skambháthuḥ RV. [√skambh]

Pa. khambhēti ʻ props, obstructs ʼ; -- Md. ken̆bum ʻ punting ʼ, kan̆banī ʻ punts ʼ?skambhadaṇḍa 13642 *skambhadaṇḍa ʻ pillar pole ʼ. [skambhá -- 1, daṇḍá -- ]

Bi. kamhãṛ, kamhaṛ, kamhaṇḍā ʻ wooden frame suspended from roof which drives home the thread in a loom ʼ.

skambhākara 13643 *skambhākara ʻ heap of sheaves ʼ. [skambhá -- 1, ākara -- ]Mth. khamhār ʻ pile of sheaves ʼ; -- altern. < *skambhaghara -- : B. khāmār ʻ barn ʼ; Or. khamāra ʻ barn, granary ʼ.Addenda: skámbhana -- : S.kcch. khāmṇo m. ʻ bed for plants ʼ.skámbhana 13644 skámbhana n. ʻ prop, pillar ʼ RV., skambhanīˊ -- f. VS. [√skambh]M. khã̄bṇī f. ʻ small post ʼ; -- G. khāmṇiyũ n. ʻ one of the ropes with which bucket is let down a well ʼ (i.e. from the post?); -- Or. khamaṇa ʻ pit, hole, waterchannel, lowland at foot of mountain ʼ; G. khāmṇũ n. ʻ small depression to stand round -- bottomed vessel in, basin at root of a tree for water ʼ: semant. cf. kūˊpa -- 1 and skambhá -- *kūpakastambha ʻ stem of a mast ʼ. [kūpa -- 2, stambha -- ] G. kuvātham m. ʻ mast of a ship ʼ.(CDIAL 3403) *ṭhōmba -- . 1. G. ṭhobrũ ʻ ugly, clumsy ʼ.2. M. ṭhõb m. ʻ bare trunk, boor, childless man ʼ, thõbā m. ʻ boor, short stout stick ʼ (LM 340 < stambha -- ).(CDIAL 5514) *ut -- stambha ʻ support ʼ. [Cf. údastambhīt RV., Pk. uṭṭhaṁbhaï ʻ supports ʼ: √stambh]

OG. uṭhaṁbha m.(CDIAL 1897) upastambha m. ʻ support ʼ Car., ʻ stay, prop ʼ Hit. 2. upaṣṭambha -- . [√stambh] 1. Pa. upatthambha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ, °aka -- ʻ supporting ʼ; Paš. ustūˊm, obl. ustumbāˊ ʻ tree, mulberry tree ʼ (IIFL iii 3, 18 < stambha -- ); M. othãbā m. ʻ stake planted as a support ʼ; Si. uvatam̆ba ʻ aid, support ʼ. 2. Pk. uvaṭṭhaṁbha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ; Dm. uṣṭúm ʻ yoke ʼ, Kal. urt. hūṣṭhum, Phal. uṣṭúm f.; OG. oṭhaṁbha m. ʻ support ʼ. upastambhayati ʻ supports, stiffens ʼ Suśr. [úpa- stabhnāti ŚBr., upastámbhana -- n. ʻ prop ʼ TS.: √stambh] Pa. upatthambhēti ʻ supports ʼ, °bhana -- n.; M. othãbṇẽ ʻ to lean upon or from, climb upon, press down ʼ.(CDIAL 2266, *kastambha ʻ small stem ʼ. [kastambhīˊ -- f. ʻ prop for supporting carriage -- pole ʼ ŚBr.: ka -- 3, stambha -- ] M. kāthãbā m. ʻ plantain offshoot, sucker, stole ʼ.(CDIAL 2983)stambha m. ʻ pillar, post ʼ Kāṭh., °aka -- m. Mahāvy. [√stambh]Pa. thambha -- m. ʻ pillar ʼ, Aś.rum. thabhe loc., top. thaṁbhe, ru. ṭha(ṁ)bhasi, Pk. thaṁbha -- , °aya -- , taṁbha -- , ṭhaṁbha -- m.; Wg. štɔ̈̄ma ʻ stem, tree ʼ, Kt. štom, Pr. üštyobu; Bshk. "ṭam"ʻ tree ʼ NTS xviii 124, Tor. thām; K. tham m. ʻ pillar, post ʼ, S. thambhu m.; L. thamm, thammā m. ʻ prop ʼ, (Ju.)tham, °mā, awāṇ. tham, khet. thambā; P. thamb(h), thamm(h) ʻ pillar, post ʼ, Ku. N. B. thām, Or. thamba; Bi. mar -- thamh ʻ upright post of oil -- mill ʼ; H. thã̄bh, thām, thambā ʻ prop, pillar, stem of plantain tree ʼ; OMarw. thāma m. ʻ pillar ʼ, Si. ṭäm̆ba; Md. tambu, tabu ʻ pillar, post ʼ; -- ext. -- ḍ -- : S.thambhiṛī f. ʻ inside peg of yoke ʼ; N. thāṅro ʻ prop ʼ; Aw.lakh. thãbharā ʻ post ʼ; H. thamṛā ʻ thick, corpulent ʼ; -- -- ll -- ; G. thã̄bhlɔ, thã̄blɔ m. ʻ post, pillar ʼ. -- X sthūˊṇā -- q.v. S.kcch. thambhlo m. ʻ pillar ʼ, A. thām, Md. tan̆bu.

stámbhatē ʻ supports, arrests ʼ Dhātup., stambhant<-> ʻ supporting ʼ Hariv., stambhayati ʻ supports ʼ MBh. [Cf. ástabhnāt imperf., tastámbha perf. RV.; -- úpa stabhāyati RV., pratistabdha -- MBh., Pa. upatthambhēti ʻ makes firm ʼ, paṭitthambhati ʻ stands firm against ʼ. <-> √stambh]Pk. thaṁbhaï, ṭhaṁbhaï tr. ʻ stops ʼ, intr. ʻ is stopped ʼ; K. thamun, thāmun ʻ to be stopped, be at rest ʼ; S. thambhaṇu ʻ to support ʼ, thamaṇu ʻ to stop, subside ʼ, ṭhambhaṇu ʻ to numb, make torpid ʼ; L. (Ju.) thannaṇ ʻ to make firm by pressing in ʼ (X tunnaṇ < *tundati), awāṇ. thammuṇ ʻ to hold ʼ; P.thambhṇā, thambṇā, thammhṇā ʻ to support, restrain ʼ; WPah.jaun. thã̄bhṇō̃ ʻ to catch, hold, conceive ʼ, (Joshi) thāmbhṇu ʻ to hold ʼ; Ku. thã̄bhṇo, thāmṇoʻ to prop, hold, stop ʼ (whence intr. thamṇo ʻ to stop) ʼ; N. thāmnu ʻ to support, hold, stop, wait ʼ; A. thamā -- dai ʻ solid curd ʼ; B. thāmā ʻ to stop, be silent ʼ; Or. thāmibā ʻ to stop ʼ (whence intr. thambibā, thamibā ʻ to come to a stop ʼ); Bhoj. thām(h)ab tr. ʻ to hold up ʼ, intr. ʻ to stop ʼ; H. thã̄bhnā,thã̄bnā, thām(h)nā ʻ to prop, stop, resist ʼ (whence intr. thambhnā ʻ to stand still ʼ); G. thãbhvũ ʻ to stand firm ʼ; M. thã̄bṇẽ, thāmṇẽ, thamṇẽ intr. ʻ to stop ʼ; Si. tabanavā ʻ to fix, place, preserve ʼ, tibanavā (X tiyanavā< sthitá -- ). -- Ext. -- kk -- : A. thamakiba ʻ to come to a sudden stop ʼ; B. thamkāna ʻ to stand still from surprise ʼ.WPah.kṭg. ṭhɔ́mbhṛu m. ʻ jostling, a partic. game ʼ (Him.I 82), thámbhṇõ ʻ to hold, support ʼ, J. thāmbhṇu ʻ to hold, catch ʼ; Md.tibenī ʻ waits ʼ, tibbanī ʻ places, clips ʼ (absol. tibbā ʻ while being ʼ), bētibbanī ʻ sets, detains ʼ (bē -- ?).(CDIAL 13682, 13683)stambhana ʻ stopping ʼ MBh., n. ʻ stiffening ʼ Suśr., ʻ means of making stiff ʼ Hcat. [√stambh]

Pa. thambhanā -- f. ʻ firmness ʼ; Pk. thaṁbhaṇa -- n., °ṇayā -- f. ʻ act of stopping ʼ; S. thambhaṇu m. ʻ glue ʼ, L. thambhaṇ m.(CDIAL 13684)

தாம்பிரம் tāmpiram , n. < tāmra. 1. Copper. See தாமிரம். (சூடா.) 2. Red; சிவப்பு. (இலக். அக.)தாம்பிரகாரன் tāmpira-kāraṉ , n. < id. + kāra. Coppersmith; செம்புகொட்டி. (யாழ். அக.) தாம்பிரசபை tāmpira-capai , n. < id. +. Dancing hall of Naṭarāja at Tinnevelly, as roofed with copper; [தாம்பிரத்தால் வேய்ந்த சபை] திருநெல்வேலியில் நடராசமூர்த்தி எழுந்தருளி யிருக்கும் சபை.தாம்பிரகம் tāmpirakam , n. < tāmraka. See தாமிரம். (யாழ். அக.) தாம்பரம் tāmparam , n. < tāmra. See தாமிரம். (பதார்த்த. 1170.)

தாம்பாளம் tāmpāḷam, n. [T. tāmbāḷamu, K. tāmbāḷa.] Salver of a large size; ஒருவகைத் தட்டு. தளிகை காளாஞ்சி தாம்பாளம் (பிர போத. 11, 31).

<tamba>(ZA) {N} ``^copper''. *Or. #33740.<ta~ba> {N} ``^copper''. *De.<tama>(M),,<tamba>(G). @N0527. #23581.tāmrá ʻ dark red, copper -- coloured ʼ VS., n. ʻ copper ʼ Kauś., tāmraka -- n. Yājñ. [Cf. tamrá -- . -- √tam?] Pa. tamba -- ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻ copper ʼ, Pk. taṁba -- adj. and n.; Dm. trāmba -- ʻ red ʼ (in trāmba -- lac̣uk ʻ raspberry ʼ NTS xii 192); Bshk. lām ʻ copper, piece of bad pine -- wood (< ʻ *red wood ʼ?); Phal. tāmba ʻ copper ʼ (→ Sh.koh. tāmbā), K. trām m. (→ Sh.gil. gur. trām m.), S. ṭrāmo m., L. trāmā, (Ju.)tarāmã̄ m., P. tāmbā m., WPah. bhad. ṭḷām n., kiũth. cāmbā, sod. cambo, jaun. tã̄bō, Ku. N. tāmo (pl. ʻ young bamboo shoots ʼ), A. tām, B. tã̄bā, tāmā, Or.tambā, Bi tã̄bā, Mth. tām, tāmā, Bhoj. tāmā, H. tām in cmpds., tã̄bā, tāmā m., G. trã̄bũ, tã̄bũ n.;M. tã̄bẽ n. ʻ copper ʼ, tã̄b f. ʻ rust, redness of sky ʼ; Ko.tāmbe n. ʻ copper ʼ; Si. tam̆ba adj. ʻ reddish ʼ, sb. ʻ copper ʼ, (SigGr) tam, tama. -- Ext. -- ira -- : Pk. taṁbira -- ʻ coppercoloured, red ʼ, L. tāmrā ʻ copper -- coloured (of pigeons) ʼ; -- with -- ḍa -- : S. ṭrāmiṛo m. ʻ a kind of cooking pot ʼ, ṭrāmiṛī ʻ sunburnt, red with anger ʼ, f. ʻ copper pot ʼ; Bhoj. tāmrā ʻ copper vessel ʼ; H. tã̄bṛā, tāmṛā ʻ coppercoloured, dark red ʼ, m. ʻ stone resembling a ruby ʼ; G. tã̄baṛ n., trã̄bṛī, tã̄bṛī f. ʻ copper pot ʼ; OM. tāṁbaḍā ʻ red ʼ. -- X trápu -- q.v. tāmrá -- [< IE. *tomró -- T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 65] S.kcch. trāmo, tām(b)o m. ʻ copper ʼ, trāmbhyo m. ʻ an old copper coin ʼ; WPah.kc. cambo m. ʻ copper ʼ, J. cāmbā m., kṭg. (kc.) tambɔ m. (← P. or H. Him.I 89), Garh. tāmu, tã̄bu. (CDIAL 5779)

tāmrakāra m. ʻ coppersmith ʼ lex. [tāmrá -- , kāra -- 1]Or. tāmbarā ʻ id. ʼ.(CDIAL 5780)

tāmrakuṭṭa m. ʻ coppersmith ʼ R. [tāmrá -- , kuṭṭa -- ] N. tamauṭe, tamoṭe ʻ id. ʼ.Garh. ṭamoṭu ʻ coppersmith ʼ; Ko. tāmṭi. (CDIAL 5781)

*tāmraghaṭa ʻ copper pot ʼ. [tāmrá -- , ghaṭa -- 1] Bi. tamheṛī ʻ round copper vessel ʼ; -- tamheṛā ʻ brassfounder ʼ der. *tamheṛ ʻ copper pot ʼ or < next?(CDIAL 5782)

*tāmraghaṭaka ʻ copper -- worker ʼ. [tāmrá -- , ghaṭa -- 2] Bi. tamheṛā ʻ brass -- founder ʼ or der. fr. *tamheṛ see prec.(CDIAL 5783)

tāmracūḍa ʻ red -- crested ʼ MBh., m. ʻ cock ʼ Suśr. [tāmrá -- , cūˊḍa -- 1]Pa. tambacūḷa -- m. ʻ cock ʼ, Pk. taṁbacūla -- m.; -- Si. tam̆basiluvā ʻ cock ʼ (EGS 61) either a later cmpd. (as in Pk.) or ← Pa.(CDIAL 5784)

*tāmradhāka ʻ copper receptacle ʼ. [tāmrá -- , dhāká -- ] Bi. tamahā ʻ drinking vessel made of a red alloy ʼ.(CDIAL 5785)

tāmrapaṭṭa m. ʻ copper plate (for inscribing) ʼ Yājñ. [Cf. tāmrapattra -- . -- tāmrá -- , paṭṭa -- 1] M. tã̄boṭī f. ʻ piece of copper of shape and size of a brick ʼ.(CDIAL 5786)

tāmrapattra n. ʻ copper plate (for inscribing) ʼ lex. [Cf. tāmrapaṭṭa -- . -- tāmrá -- , páttra -- ] Ku.gng. tamoti ʻ copper plate ʼ.(CDIAL 5787)

tāmrapātra n. ʻ copper vessel ʼ MBh. [tāmrá -- , pāˊtra -- ] Ku.gng. tamoi ʻ copper vessel for water ʼ.(CDIAL 5788)

*tāmrabhāṇḍa ʻ copper vessel ʼ. [tāmrá -- , bhāṇḍa -- 1] Bhoj. tāmaṛā, tāmṛā ʻ copper vessel ʼ; G. tarbhāṇũ n. ʻ copper dish used in religious ceremonies ʼ (< *taramhã̄ḍũ).(CDIAL 5789)

tāmravarṇa ʻ copper -- coloured ʼ TĀr. [tāmrá -- , várṇa -- 1] Si. tam̆bavan ʻ copper -- coloured, dark red ʼ (EGS 61) prob. a Si. cmpd.(CDIAL 5790)

tāmrākṣa ʻ red -- eyed ʼ MBh. [tāmrá -- , ákṣi -- ]Pa. tambakkhin -- ; P. tamak f. ʻ anger ʼ; Bhoj. tamakhal ʻ to be angry ʼ; H. tamaknā ʻ to become red in the face, be angry ʼ.(CDIAL 5791)

tāmrika ʻ coppery ʼ Mn. [tāmrá -- ] Pk. taṁbiya -- n. ʻ an article of an ascetic's equipment (a copper vessel?) ʼ; L. trāmī f. ʻ large open vessel for kneading bread ʼ, poṭh. trāmbī f. ʻ brass plate for kneading on ʼ; Ku.gng. tāmi ʻ copper plate ʼ; A. tāmi ʻ copper vessel used in worship ʼ; B. tāmī, tamiyā ʻ large brass vessel for cooking pulses at marriages and other ceremonies ʼ; H. tambiyā m. ʻ copper or brass vessel ʼ.(CDIAL 5792)

Smithy is the temple of Bronze Age: stambha, thãbharā fiery pillar of light, Sivalinga. Rebus-metonymy layered Indus script cipher signifies: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper' The semantics of stambha, thãbharā as hieroglyphs and of tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira as 'copper' using phonetic variants of Vedic chandas and Meluhha speech are evidenced by Meluhha glosses (Indian sprachbund) provided in the Annex.Dholavira excavation report has provided evidence for the locations of a pair of pillars fronting a 8-shaped temple signifying a kole.l 'smithy, temple' (Kota)(See: DEDR 2133). A smithy-forge was the temple.Smithy as temple signifies the gestalt (structure, configuration, or pattern of physical, biological, or metaphysical phenomena) of Sarasvati's children, the artisans, Bhāratam Janam, 'lit. metalcaster folk' (expression used in Rigveda) of the civilization. Ta. kol working in iron, lacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy. Ka. kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go. (SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133) golī f., gollɔ m. ʻ devotee of a goddess ʼ(Gujarati)(CDIAL 4325) Pk. kōla -- m.; B. kol ʻ name of a Muṇḍā tribe ʼ.(CDIAL 3532). kolhe 'kol, smelters' (Santali) kaula -- m. ʻ worshipper of Śakti according to left -- hand ritual ʼ(Samskritam)The evidence from Indian sprachbund, Meluhha speech and archaeological artifacts of the civilization, is that the pillars of the Bronze Age were worshipped as s'ivalinga while signifying the location as a smithy, forge. Annex provides evidence from Rigveda associating Rudra (often linked with S'iva in ancient texts) with weapons (e.g. RV 6.74.4).The association of a smithy-forge with a temple is consistent with the celebration of khaṇḍōbā Rudra-s'iva and the semantics of लोखंड [lōkhaṇḍa] 'metalware' discussed in the context of hieroglyphs of Indus Script Corpra: Temple: खंडेराव [ khaṇḍērāva ] m (खंड Sword, and राव) An incarnation of Shiva. Popularly खंडेराव is but dimly distinguished from भैरव. खंडोबा [ khaṇḍōbā ] m A familiar appellation of the god खंडेराव. खंडोबाचा कुत्रा [ khaṇḍōbācā kutrā ] m (Dog of खंडोबा. From his being devoted to the temple.) A term for the वाघ्या or male devotee of खंडोबा.

Hieroglyph: खंडोबाची काठी [ khaṇḍōbācī kāṭhī ] f The pole of खंडोबा. It belongs to the temples of this god, is taken and presented, in pilgrimages, at the visited shrines, is carried about in processions &c. It is covered with cloth (red and blue), and has a plume (generally from the peacock's tail) waving from its top.The cultural link of metalwork with Rudra-Siva iconically denoted by 1) orthographic variants of linga, 2) ekamukhalinga evidences of Ancient Far East and 3) the presence of linga in the context of a metal smelter in a Bhuteshwar artifact of 2nd cent. BCE is thus an area for further detailed investigation in archaeometallurgy and historical linguistics of Indian Sprachbund.Architectural fragment with relief showing winged dwarfs (or gaNa) worshipping with flower garlands, Siva Linga. Bhuteshwar, ca. 2nd cent BCE. Lingam is on a platform with wall under a pipal tree encircled by railing. (Srivastava, AK, 1999, Catalogue of Saiva sculptures in Government Museum, Mathura: 47, GMM 52.3625) The tree is a phonetic determinant of the smelter indicated by the railing around the linga: kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ lex., °ṭaka -- m. ʻ a kind of tree ʼ Kauś.Pk. kuḍa -- m. ʻ tree ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. kuṛāˊ ʻ tree ʼ, dar. kaṛék ʻ tree, oak ʼ ~ Par. kōṛ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL iii 3, 98. (CDIAL 3228). In Atharva Veda stambha is a celestial scaffold, supporting the cosmos and material creation.See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/12/skambha-sukta-atharva-veda-x-7-pair-of.html Full text of Atharva Veda ( X - 7,8) --- Stambha Suktam with translation (with variant pronunciation as skambha). See Annex A List of occurrences of gloss in Atharva Veda.avs.8.6 [0800605] The black and hairy Asura, and Stambaja and Tundika, Arayas from this girl we drive, from bosom, waist, and parts below.

Archaeological finds: cylindrical stele in Kalibangan, a pair of polished stone pillars in Dholavira, s'ivalinga in Harappa, KalibanganEvidence for Sivalinga is provided in other sites (Mohenjodaro and Harappa) of the civilization:![]()

Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218.

Lingam, grey sandstone in situ, Harappa, Trench Ai, Mound F, Pl. X (c) (After Vats). "In an earthenware jar, No. 12414, recovered from Mound F, Trench IV, Square I... in this jar, six lingams were found along with some tiny pieces of shell, a unicorn seal, an oblong grey sandstone block with polished surface, five stone pestles, a stone palette, and a block of chalcedony..." (Vats,MS, Excavations at Harappa, p. 370)Cylindrical clay steles of 10 to 15 cms height occur in ancient fire-altars (See report by BB Lal on Kalibangan excavations).A number of polished stone pillars were found in Dholavira. (See April 2015 published Dholavira excavation report: http://asi.nic.in/pdf_data/dholavira_excavation_report_new.pdfThese evidences of sivalinga and pillars evoke the imageries of a festival which is celebrated even today by Lingavantas, particularly in Karnataka. The festival is a continuum of the tradition which started in Sarasvati-Sindhu (Hindu) Civilization during the Bronze Age, given the evidences of the worship states in which the pillars and sivalingas are found in Dholavira and Harappa and the presence of cylindrical steles as hieroglyphs in fire-altars of Kalibangan and other archaeological sites of the civilization.It is, thus, possible to hypothesise that the religious practices of the people of the civilization at Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Kalibangan (where a terracotta Sivalinga has been found) and Dholavira are represented by the continuum of koṇḍahabba festivals celebrated by Lingavantas.![]()

![]()

![]()

”Within the group of religious buildings that remain in Hampi , highlighting the numerous temples , in front of which are these Shiva lingam . It is very common for Shiva lingam rock be excavated outside if there is a nearby temple , given its ritual , but here are carved on the granite rock of the hill. Its religious significance is emphasized by the appearance of small channels on which water is poured to perform rituals and offerings to Shiva . They were carved in succession during the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries , and are pieces of variable size and composition more or less complex. Centerpiece normally appears a larger lingam environment that provides a small bowl , around it a mesh peqrfecta organized lingams appear smaller and leave room for a small channel which runs central to the bowl surrounds the lingam greater. The pieces usually have a diameter of about 25cm and a height of 10 to 15cm . In some cases are screened lingam simpler or smaller, or their component parts are smaller .” (Translated from French). http://tectonicablog.com/?p=34419

Galaganatha is a village south of Varada-Tungabhadra Sangama in Haveri district. In ancient inscriptions Galaganatha is referred to as Palluni.Galagesvaragudi is a unique experiment of Kalyani Chalukyan temple architecture. The temple is east facing and situated on the bank of river Tungabhadra. The temple tapers right from its base to the top of the Shikhara. This temple is under the care of Archaeological Survey of India.![]()

![]()

The temple can be entered from 3 sides.![]()

paṭṭaḍi cognate phaḍā 'smithy, metals manufactory' is cognate phaḍā 'metals manufactory'

Hieroglyph: फडा (p. 313) phaḍā f (फटा S) The hood of Coluber Nága &c. Ta. patam cobra's hood. Ma. paṭam id. Ka. peḍe id. Te. paḍaga id. Go. (S.) paṛge, (Mu.) baṛak, (Ma.) baṛki, (F-H.) biṛki hood of serpent (Voc. 2154). / Turner, CDIAL, no. 9040, Skt. (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā- id. For IE etymology, see Burrow, The Problem of Shwa in Sanskrit, p. 45.(DEDR 47) Rebus: phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office’, keeper of all accounts, registers.

फडपूस (p. 313) phaḍapūsa f (फड & पुसणें) Public or open inquiry. फडफरमाश or स (p. 313) phaḍapharamāśa or sa f ( H & P) Fruit, vegetables &c. furnished on occasions to Rajas and public officers, on the authority of their order upon the villages; any petty article or trifling work exacted from the Ryots by Government or a public officer.

फडनिविशी or सी (p. 313) phaḍaniviśī or sī & फडनिवीस Commonly फड- निशी & फडनीस. फडनीस (p. 313) phaḍanīsa m ( H) A public officer,--the keeper of the registers &c. By him were issued all grants, commissions, and orders; and to him were rendered all accounts from the other departments. He answers to Deputy auditor and accountant. Formerly the head Kárkún of a district-cutcherry who had charge of the accounts &c. was called फडनीस.

फडकरी (p. 313) phaḍakarī m A man belonging to a company or band (of players, showmen &c.) 2 A superintendent or master of a फड or public place. See under फड. 3 A retail-dealer (esp. in grain).

फडझडती (p. 313) phaḍajhaḍatī f sometimes फडझाडणी f A clearing off of public business (of any business comprehended under the word फड q. v.): also clearing examination of any फड or place of public business.

फड (p. 313) phaḍa m ( H) A place of public business or public resort; as a court of justice, an exchange, a mart, a counting-house, a custom-house, an auction-room: also, in an ill-sense, as खेळण्या- चा फड A gambling-house, नाचण्याचा फड A nach house, गाण्याचा or ख्यालीखुशालीचा फड A singing shop or merriment shop. The word expresses freely Gymnasium or arena, circus, club-room, debating-room, house or room or stand for idlers, newsmongers, gossips, scamps &c. 2 The spot to which field-produce is brought, that the crop may be ascertained and the tax fixed; the depot at which the Government-revenue in kind is delivered; a place in general where goods in quantity are exposed for inspection or sale. 3 Any office or place of extensive business or work, as a factory, manufactory, arsenal, dock-yard, printing-office &c. 4 A plantation or field (as of ऊस, वांग्या, मिरच्या, खरबुजे &c.): also a standing crop of such produce. 5 fig. Full and vigorous operation or proceeding, the going on with high animation and bustle (of business in general). v चाल, पड, घाल, मांड. 6 A company, a troop, a band or set (as of actors, showmen, dancers &c.) 7 The stand of a great gun. फड पडणें g. of s. To be in full and active operation. 2 To come under brisk discussion. फड मारणें- राखणें-संभाळणें To save appearances, फड मारणें or संपादणें To cut a dash; to make a display (upon an occasion). फडाच्या मापानें With full tale; in flowing measure. फडास येणें To come before the public; to come under general discussion.

பட்டரை¹ paṭṭarai , n. See பட்டறை¹. (C. G . 95.) பட்டறை¹ paṭṭaṟai , n. < பட்டடை¹. 1. See பட்டடை, 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 12, 14. 2. Machine; யந்திரம். 3. Rice-hulling machine; நெல்லுக் குத்தும் யந்திரம். Mod. 4. Factory; தொழிற்சாலை. Mod. 5. Beam of a house; வீட்டின் உத்திரம். 6. Wall of the required height from the flooring of a house; வீட்டின் தளத்திலிருந்து எழுப்ப வேண்டும் அளவில் எழுப்பிய சுவர். வீடுகளுக்குப் பட்டறை மட்டம் ஒன்பதடி உயரத்துக்குக் குறை யாமல் (சர்வா. சிற். 48). பட்டறை² paṭṭaṟai , n. < K. paṭṭale. 1. Community; சனக்கூட்டம். 2. Guild, as of workmen; தொழிலாளர் சமுதாயம். (Tamil)

Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236)

skabha 13638 *skabha ʻ post, peg ʼ. [√skambh]Kal. Kho. iskow ʻ peg ʼ BelvalkarVol 86 with (?).

SKAMBH ʻ make firm ʼ: *skabdha -- , skambhá -- 1, skámbhana -- ; -- √*chambh.

skambhá 13639 skambhá1 m. ʻ prop, pillar ʼ RV. 2. ʻ *pit ʼ (semant. cf. kūˊpa -- 1). [√skambh]1. Pa. khambha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ; Pk. khaṁbha -- m. ʻ post, pillar ʼ; Pr. iškyöp, üšköb ʻ bridge ʼ NTS xv 251; L. (Ju.) khabbā m., mult. khambbā m. ʻ stake forming fulcrum for oar ʼ; P. khambh, khambhā, khammhā m. ʻ wooden prop, post ʼ; WPah.bhal. kham m. ʻ a part of the yoke of a plough ʼ, (Joshi)khāmbā m. ʻ beam, pier ʼ; Ku. khāmo ʻ a support ʼ, gng. khām ʻ pillar (of wood or bricks) ʼ; N. khã̄bo ʻ pillar, post ʼ, B. khām, khāmbā; Or. khamba ʻ post, stake ʼ; Bi. khāmā ʻ post of brick -- crushing machine ʼ, khāmhī ʻ support of betel -- cage roof ʼ, khamhiyā ʻ wooden pillar supporting roof ʼ; Mth. khāmh,khāmhī ʻ pillar, post ʼ, khamhā ʻ rudder -- post ʼ; Bhoj. khambhā ʻ pillar ʼ, khambhiyā ʻ prop ʼ; OAw. khāṁbhe m. pl. ʻ pillars ʼ, lakh. khambhā; H. khāmm. ʻ post, pillar, mast ʼ, khambh f. ʻ pillar, pole ʼ; G. khām m. ʻ pillar ʼ, khã̄bhi, °bi f. ʻ post ʼ, M. khã̄b m., Ko. khāmbho, °bo, Si. kap (< *kab); -- Xgambhīra -- , sthāṇú -- , sthūˊṇā -- qq.v.2. K. khambürü f. ʻ hollow left in a heap of grain when some is removed ʼ; Or. khamā ʻ long pit, hole in the earth ʼ, khamiā ʻ small hole ʼ; Marw. khã̄baṛoʻ hole ʼ; G. khã̄bhũ n. ʻ pit for sweepings and manure ʼ. Garh. khambu ʻ pillar ʼ.

skambha 13640 *skambha2 ʻ shoulder -- blade, wing, plumage ʼ. [Cf. *skapa -- s.v. *khavaka -- ]S. khambhu, °bho m. ʻ plumage ʼ, khambhuṛi f. ʻ wing ʼ; L. khabbh m., mult. khambh m. ʻ shoulder -- blade, wing, feather ʼ, khet. khamb ʻ wing ʼ, mult. khambhaṛā m. ʻ fin ʼ; P. khambh m. ʻ wing, feather ʼ; G. khā̆m f., khabhɔ m. ʻ shoulder ʼ.

skambhaghara 13641 *skambhaghara ʻ house of posts ʼ. [skambhá -- 1, ghara -- ]B. khāmār ʻ barn ʼ; Or. khamāra ʻ barn, granary ʼ: or < *skambhākara -- ?13641a †skámbhatē Dhātup. ʻ props ʼ, skambháthuḥ RV. [√skambh]

Bi. kamhãṛ, kamhaṛ, kamhaṇḍā ʻ wooden frame suspended from roof which drives home the thread in a loom ʼ.

SKAMBH ʻ make firm ʼ: *skabdha -- , skambhá -- 1, skámbhana -- ; -- √*chambh.

Pa. khambhēti ʻ props, obstructs ʼ; -- Md. ken̆bum ʻ punting ʼ, kan̆banī ʻ punts ʼ?

skambhadaṇḍa 13642 *skambhadaṇḍa ʻ pillar pole ʼ. [skambhá -- 1, daṇḍá -- ]Bi. kamhãṛ, kamhaṛ, kamhaṇḍā ʻ wooden frame suspended from roof which drives home the thread in a loom ʼ.

skambhākara 13643 *skambhākara ʻ heap of sheaves ʼ. [skambhá -- 1, ākara -- ]Mth. khamhār ʻ pile of sheaves ʼ; -- altern. < *skambhaghara -- : B. khāmār ʻ barn ʼ; Or. khamāra ʻ barn, granary ʼ.Addenda: skámbhana -- : S.kcch. khāmṇo m. ʻ bed for plants ʼ.skámbhana 13644 skámbhana n. ʻ prop, pillar ʼ RV., skambhanīˊ -- f. VS. [√skambh]M. khã̄bṇī f. ʻ small post ʼ; -- G. khāmṇiyũ n. ʻ one of the ropes with which bucket is let down a well ʼ (i.e. from the post?); -- Or. khamaṇa ʻ pit, hole, waterchannel, lowland at foot of mountain ʼ; G. khāmṇũ n. ʻ small depression to stand round -- bottomed vessel in, basin at root of a tree for water ʼ: semant. cf. kūˊpa -- 1 and skambhá --

*kūpakastambha ʻ stem of a mast ʼ. [kūpa -- 2, stambha -- ] G. kuvātham m. ʻ mast of a ship ʼ.(CDIAL 3403) *ṭhōmba -- . 1. G. ṭhobrũ ʻ ugly, clumsy ʼ.2. M. ṭhõb m. ʻ bare trunk, boor, childless man ʼ, thõbā m. ʻ boor, short stout stick ʼ (LM 340 < stambha -- ).(CDIAL 5514)

*ut -- stambha ʻ support ʼ. [Cf. údastambhīt RV., Pk. uṭṭhaṁbhaï ʻ supports ʼ: √stambh]

OG. uṭhaṁbha m.(CDIAL 1897) upastambha m. ʻ support ʼ Car., ʻ stay, prop ʼ Hit. 2. upaṣṭambha -- . [√stambh] 1. Pa. upatthambha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ, °aka -- ʻ supporting ʼ; Paš. ustūˊm, obl. ustumbāˊ ʻ tree, mulberry tree ʼ (IIFL iii 3, 18 < stambha -- ); M. othãbā m. ʻ stake planted as a support ʼ; Si. uvatam̆ba ʻ aid, support ʼ. 2. Pk. uvaṭṭhaṁbha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ; Dm. uṣṭúm ʻ yoke ʼ, Kal. urt. hūṣṭhum, Phal. uṣṭúm f.; OG. oṭhaṁbha m. ʻ support ʼ. upastambhayati ʻ supports, stiffens ʼ Suśr. [úpa- stabhnāti ŚBr., upastámbhana -- n. ʻ prop ʼ TS.: √stambh] Pa. upatthambhēti ʻ supports ʼ, °bhana -- n.; M. othãbṇẽ ʻ to lean upon or from, climb upon, press down ʼ.(CDIAL 2266, *kastambha ʻ small stem ʼ. [kastambhīˊ -- f. ʻ prop for supporting carriage -- pole ʼ ŚBr.: ka -- 3, stambha -- ] M. kāthãbā m. ʻ plantain offshoot, sucker, stole ʼ.(CDIAL 2983)

OG. uṭhaṁbha m.(CDIAL 1897) upastambha m. ʻ support ʼ Car., ʻ stay, prop ʼ Hit. 2. upaṣṭambha -- . [√stambh] 1. Pa. upatthambha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ, °aka -- ʻ supporting ʼ; Paš. ustūˊm, obl. ustumbāˊ ʻ tree, mulberry tree ʼ (IIFL iii 3, 18 < stambha -- ); M. othãbā m. ʻ stake planted as a support ʼ; Si. uvatam̆ba ʻ aid, support ʼ. 2. Pk. uvaṭṭhaṁbha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ; Dm. uṣṭúm ʻ yoke ʼ, Kal. urt. hūṣṭhum, Phal. uṣṭúm f.; OG. oṭhaṁbha m. ʻ support ʼ. upastambhayati ʻ supports, stiffens ʼ Suśr. [úpa- stabhnāti ŚBr., upastámbhana -- n. ʻ prop ʼ TS.: √stambh] Pa. upatthambhēti ʻ supports ʼ, °bhana -- n.; M. othãbṇẽ ʻ to lean upon or from, climb upon, press down ʼ.(CDIAL 2266, *kastambha ʻ small stem ʼ. [kastambhīˊ -- f. ʻ prop for supporting carriage -- pole ʼ ŚBr.: ka -- 3, stambha -- ] M. kāthãbā m. ʻ plantain offshoot, sucker, stole ʼ.(CDIAL 2983)

stambha m. ʻ pillar, post ʼ Kāṭh., °aka -- m. Mahāvy. [√stambh]Pa. thambha -- m. ʻ pillar ʼ, Aś.rum. thabhe loc., top. thaṁbhe, ru. ṭha(ṁ)bhasi, Pk. thaṁbha -- , °aya -- , taṁbha -- , ṭhaṁbha -- m.; Wg. štɔ̈̄ma ʻ stem, tree ʼ, Kt. štom, Pr. üštyobu; Bshk. "ṭam"ʻ tree ʼ NTS xviii 124, Tor. thām; K. tham m. ʻ pillar, post ʼ, S. thambhu m.; L. thamm, thammā m. ʻ prop ʼ, (Ju.)tham, °mā, awāṇ. tham, khet. thambā; P. thamb(h), thamm(h) ʻ pillar, post ʼ, Ku. N. B. thām, Or. thamba; Bi. mar -- thamh ʻ upright post of oil -- mill ʼ; H. thã̄bh, thām, thambā ʻ prop, pillar, stem of plantain tree ʼ; OMarw. thāma m. ʻ pillar ʼ, Si. ṭäm̆ba; Md. tambu, tabu ʻ pillar, post ʼ; -- ext. -- ḍ -- : S.thambhiṛī f. ʻ inside peg of yoke ʼ; N. thāṅro ʻ prop ʼ; Aw.lakh. thãbharā ʻ post ʼ; H. thamṛā ʻ thick, corpulent ʼ; -- -- ll -- ; G. thã̄bhlɔ, thã̄blɔ m. ʻ post, pillar ʼ. -- X sthūˊṇā -- q.v. S.kcch.

thambhlo m. ʻ pillar ʼ, A. thām, Md. tan̆bu.

Pa. thambhanā -- f. ʻ firmness ʼ; Pk. thaṁbhaṇa -- n., °ṇayā -- f. ʻ act of stopping ʼ; S. thambhaṇu m. ʻ glue ʼ, L. thambhaṇ m.(CDIAL 13684)

stámbhatē ʻ supports, arrests ʼ Dhātup., stambhant<-> ʻ supporting ʼ Hariv., stambhayati ʻ supports ʼ MBh. [Cf. ástabhnāt imperf., tastámbha perf. RV.; -- úpa stabhāyati RV., pratistabdha -- MBh., Pa. upatthambhēti ʻ makes firm ʼ, paṭitthambhati ʻ stands firm against ʼ. <-> √stambh]Pk. thaṁbhaï, ṭhaṁbhaï tr. ʻ stops ʼ, intr. ʻ is stopped ʼ; K. thamun, thāmun ʻ to be stopped, be at rest ʼ; S. thambhaṇu ʻ to support ʼ, thamaṇu ʻ to stop, subside ʼ, ṭhambhaṇu ʻ to numb, make torpid ʼ; L. (Ju.) thannaṇ ʻ to make firm by pressing in ʼ (X tunnaṇ < *tundati), awāṇ. thammuṇ ʻ to hold ʼ; P.thambhṇā, thambṇā, thammhṇā ʻ to support, restrain ʼ; WPah.jaun. thã̄bhṇō̃ ʻ to catch, hold, conceive ʼ, (Joshi) thāmbhṇu ʻ to hold ʼ; Ku. thã̄bhṇo, thāmṇoʻ to prop, hold, stop ʼ (whence intr. thamṇo ʻ to stop) ʼ; N. thāmnu ʻ to support, hold, stop, wait ʼ; A. thamā -- dai ʻ solid curd ʼ; B. thāmā ʻ to stop, be silent ʼ; Or. thāmibā ʻ to stop ʼ (whence intr. thambibā, thamibā ʻ to come to a stop ʼ); Bhoj. thām(h)ab tr. ʻ to hold up ʼ, intr. ʻ to stop ʼ; H. thã̄bhnā,thã̄bnā, thām(h)nā ʻ to prop, stop, resist ʼ (whence intr. thambhnā ʻ to stand still ʼ); G. thãbhvũ ʻ to stand firm ʼ; M. thã̄bṇẽ,

thāmṇẽ, thamṇẽ intr. ʻ to stop ʼ; Si. tabanavā ʻ to fix, place, preserve ʼ, tibanavā (X tiyanavā< sthitá -- ). -- Ext. -- kk -- : A. thamakiba ʻ to come to a sudden stop ʼ; B. thamkāna ʻ to stand still from surprise ʼ.WPah.kṭg. ṭhɔ́mbhṛu m. ʻ jostling, a partic. game ʼ (Him.I 82), thámbhṇõ ʻ to hold, support ʼ, J. thāmbhṇu ʻ to hold, catch ʼ; Md.tibenī ʻ waits ʼ, tibbanī ʻ places, clips ʼ (absol. tibbā ʻ while being ʼ), bētibbanī ʻ sets, detains ʼ (bē -- ?).(CDIAL 13682, 13683)

stambhana ʻ stopping ʼ MBh., n. ʻ stiffening ʼ Suśr., ʻ means of making stiff ʼ Hcat. [√stambh]Pa. thambhanā -- f. ʻ firmness ʼ; Pk. thaṁbhaṇa -- n., °ṇayā -- f. ʻ act of stopping ʼ; S. thambhaṇu m. ʻ glue ʼ, L. thambhaṇ m.(CDIAL 13684)

தாம்பிரம் tāmpiram , n. < tāmra. 1. Copper. See தாமிரம். (சூடா.) 2. Red; சிவப்பு. (இலக். அக.)தாம்பிரகாரன் tāmpira-kāraṉ , n. < id. + kāra. Coppersmith; செம்புகொட்டி. (யாழ். அக.) தாம்பிரசபை tāmpira-capai , n. < id. +. Dancing hall of Naṭarāja at Tinnevelly, as roofed with copper; [தாம்பிரத்தால் வேய்ந்த சபை] திருநெல்வேலியில் நடராசமூர்த்தி எழுந்தருளி யிருக்கும் சபை.தாம்பிரகம் tāmpirakam , n. < tāmraka. See தாமிரம். (யாழ். அக.) தாம்பரம் tāmparam , n. < tāmra. See தாமிரம். (பதார்த்த. 1170.)

தாம்பாளம் tāmpāḷam, n. [T. tāmbāḷamu, K. tāmbāḷa.] Salver of a large size; ஒருவகைத் தட்டு. தளிகை காளாஞ்சி தாம்பாளம் (பிர போத. 11, 31).

<tamba>(ZA) {N} ``^copper''. *Or. #33740.<ta~ba> {N} ``^copper''. *De.<tama>(M),,<tamba>(G). @N0527. #23581.tāmrá ʻ dark red, copper -- coloured ʼ VS., n. ʻ copper ʼ Kauś., tāmraka -- n. Yājñ. [Cf. tamrá -- . -- √tam?] Pa. tamba -- ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻ copper ʼ, Pk. taṁba -- adj. and n.; Dm. trāmba -- ʻ red ʼ (in trāmba -- lac̣uk ʻ raspberry ʼ NTS xii 192); Bshk. lām ʻ copper, piece of bad pine -- wood (< ʻ *red wood ʼ?); Phal. tāmba ʻ copper ʼ (→ Sh.koh. tāmbā), K. trām m. (→ Sh.gil. gur. trām m.), S. ṭrāmo m., L. trāmā, (Ju.)tarāmã̄ m., P. tāmbā m., WPah. bhad. ṭḷām n., kiũth. cāmbā, sod. cambo, jaun. tã̄bō, Ku. N. tāmo (pl. ʻ young bamboo shoots ʼ), A. tām, B. tã̄bā, tāmā, Or.tambā, Bi tã̄bā, Mth. tām, tāmā, Bhoj. tāmā, H. tām in cmpds., tã̄bā, tāmā m., G. trã̄bũ, tã̄bũ n.;M. tã̄bẽ n. ʻ copper ʼ, tã̄b f. ʻ rust, redness of sky ʼ; Ko.tāmbe n. ʻ copper ʼ; Si. tam̆ba adj. ʻ reddish ʼ, sb. ʻ copper ʼ, (SigGr) tam, tama. -- Ext. -- ira -- : Pk. taṁbira -- ʻ coppercoloured, red ʼ, L. tāmrā ʻ copper -- coloured (of pigeons) ʼ; -- with -- ḍa -- : S. ṭrāmiṛo m. ʻ a kind of cooking pot ʼ, ṭrāmiṛī ʻ sunburnt, red with anger ʼ, f. ʻ copper pot ʼ; Bhoj. tāmrā ʻ copper vessel ʼ; H. tã̄bṛā, tāmṛā ʻ coppercoloured, dark red ʼ, m. ʻ stone resembling a ruby ʼ; G. tã̄baṛ n., trã̄bṛī, tã̄bṛī f. ʻ copper pot ʼ; OM. tāṁbaḍā ʻ red ʼ. -- X trápu -- q.v. tāmrá -- [< IE. *tomró -- T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 65] S.kcch. trāmo,

tām(b)o m. ʻ copper ʼ, trāmbhyo m. ʻ an old copper coin ʼ; WPah.kc. cambo m. ʻ copper ʼ, J. cāmbā m., kṭg. (kc.) tambɔ m. (← P. or H. Him.I 89), Garh. tāmu, tã̄bu. (CDIAL 5779)

tāmrakāra m. ʻ coppersmith ʼ lex. [tāmrá -- , kāra -- 1]Or. tāmbarā ʻ id. ʼ.(CDIAL 5780)

tāmrakuṭṭa m. ʻ coppersmith ʼ R. [tāmrá -- , kuṭṭa -- ] N. tamauṭe, tamoṭe ʻ id. ʼ.Garh. ṭamoṭu ʻ coppersmith ʼ; Ko. tāmṭi. (CDIAL 5781)

Smithy is the temple of Bronze Age: stambha, thãbharā fiery pillar of light, Sivalinga. Rebus-metonymy layered Indus script cipher signifies: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper'

The semantics of stambha, thãbharā as hieroglyphs and of tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira as 'copper' using phonetic variants of Vedic chandas and Meluhha speech are evidenced by Meluhha glosses (Indian sprachbund) provided in the Annex.

Dholavira excavation report has provided evidence for the locations of a pair of pillars fronting a 8-shaped temple signifying a kole.l 'smithy, temple' (Kota)(See: DEDR 2133).

A smithy-forge was the temple.

Smithy as temple signifies the gestalt (structure, configuration, or pattern of physical, biological, or metaphysical phenomena) of Sarasvati's children, the artisans, Bhāratam Janam, 'lit. metalcaster folk' (expression used in Rigveda) of the civilization.

Ta. kol working in iron, lacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy. Ka. kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë

blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go. (SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133) golī f., gollɔ m. ʻ devotee of a goddess ʼ(Gujarati)(CDIAL 4325) Pk. kōla -- m.; B. kol ʻ name of a Muṇḍā tribe ʼ.(CDIAL 3532). kolhe 'kol, smelters' (Santali) kaula -- m. ʻ worshipper of Śakti according to left -- hand ritual ʼ(Samskritam)

The evidence from Indian sprachbund, Meluhha speech and archaeological artifacts of the civilization, is that the pillars of the Bronze Age were worshipped as s'ivalinga while signifying the location as a smithy, forge.

Annex provides evidence from Rigveda associating Rudra (often linked with S'iva in ancient texts) with weapons (e.g. RV 6.74.4).

The association of a smithy-forge with a temple is consistent with the celebration of khaṇḍōbā Rudra-s'iva and the semantics of लोखंड [lōkhaṇḍa] 'metalware' discussed in the context of hieroglyphs of Indus Script Corpra:

Temple: खंडेराव [ khaṇḍērāva ] m (खंड Sword, and राव) An incarnation of Shiva. Popularly खंडेराव is but dimly distinguished from भैरव. खंडोबा [ khaṇḍōbā ] m A familiar appellation of the god खंडेराव. खंडोबाचा कुत्रा [ khaṇḍōbācā kutrā ] m (Dog of खंडोबा. From his being devoted to the temple.) A term for the वाघ्या or male devotee of खंडोबा.

Hieroglyph: खंडोबाची काठी [ khaṇḍōbācī kāṭhī ] f The pole of खंडोबा. It belongs to the temples of this god, is taken and presented, in pilgrimages, at the visited shrines, is carried about in processions &c. It is covered with cloth (red and blue), and has a plume (generally from the peacock's tail) waving from its top.

The cultural link of metalwork with Rudra-Siva iconically denoted by 1) orthographic variants of linga, 2) ekamukhalinga evidences of Ancient Far East and 3) the presence of linga in the context of a metal smelter in a Bhuteshwar artifact of 2nd cent. BCE is thus an area for further detailed investigation in archaeometallurgy and historical linguistics of Indian Sprachbund.

Architectural fragment with relief showing winged dwarfs (or gaNa) worshipping with flower garlands, Siva Linga. Bhuteshwar, ca. 2nd cent BCE. Lingam is on a platform with wall under a pipal tree encircled by railing. (Srivastava, AK, 1999, Catalogue of Saiva sculptures in Government Museum, Mathura: 47, GMM 52.3625) The tree is a phonetic determinant of the smelter indicated by the railing around the linga: kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ lex., °ṭaka -- m. ʻ a kind of tree ʼ Kauś.Pk. kuḍa -- m. ʻ tree ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. kuṛāˊ ʻ tree ʼ, dar. kaṛék ʻ tree, oak ʼ ~ Par. kōṛ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL iii 3, 98. (CDIAL 3228).

In Atharva Veda stambha is a celestial scaffold, supporting the cosmos and material creation.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/12/skambha-sukta-atharva-veda-x-7-pair-of.html Full text of Atharva Veda ( X - 7,8) --- Stambha Suktam with translation (with variant pronunciation as skambha). See Annex A List of occurrences of gloss in Atharva Veda.

| avs.8.6 | [0800605] The black and hairy Asura, and Stambaja and Tundika, Arayas from this girl we drive, from bosom, waist, and parts below. |

Archaeological finds: cylindrical stele in Kalibangan, a pair of polished stone pillars in Dholavira, s'ivalinga in Harappa, Kalibangan

Evidence for Sivalinga is provided in other sites (Mohenjodaro and Harappa) of the civilization:

Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218.

Lingam, grey sandstone in situ, Harappa, Trench Ai, Mound F, Pl. X (c) (After Vats). "In an earthenware jar, No. 12414, recovered from Mound F, Trench IV, Square I... in this jar, six lingams were found along with some tiny pieces of shell, a unicorn seal, an oblong grey sandstone block with polished surface, five stone pestles, a stone palette, and a block of chalcedony..." (Vats,MS, Excavations at Harappa, p. 370)

Cylindrical clay steles of 10 to 15 cms height occur in ancient fire-altars (See report by BB Lal on Kalibangan excavations).

A number of polished stone pillars were found in Dholavira. (See April 2015 published Dholavira excavation report: http://asi.nic.in/pdf_data/dholavira_excavation_report_new.pdf

These evidences of sivalinga and pillars evoke the imageries of a festival which is celebrated even today by Lingavantas, particularly in Karnataka. The festival is a continuum of the tradition which started in Sarasvati-Sindhu (Hindu) Civilization during the Bronze Age, given the evidences of the worship states in which the pillars and sivalingas are found in Dholavira and Harappa and the presence of cylindrical steles as hieroglyphs in fire-altars of Kalibangan and other archaeological sites of the civilization.

It is, thus, possible to hypothesise that the religious practices of the people of the civilization at Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Kalibangan (where a terracotta Sivalinga has been found) and Dholavira are represented by the continuum of koṇḍahabba festivals celebrated by Lingavantas.

”Within the group of religious buildings that remain in Hampi , highlighting the numerous temples , in front of which are these Shiva lingam . It is very common for Shiva lingam rock be excavated outside if there is a nearby temple , given its ritual , but here are carved on the granite rock of the hill. Its religious significance is emphasized by the appearance of small channels on which water is poured to perform rituals and offerings to Shiva . They were carved in succession during the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries , and are pieces of variable size and composition more or less complex. Centerpiece normally appears a larger lingam environment that provides a small bowl , around it a mesh peqrfecta organized lingams appear smaller and leave room for a small channel which runs central to the bowl surrounds the lingam greater. The pieces usually have a diameter of about 25cm and a height of 10 to 15cm . In some cases are screened lingam simpler or smaller, or their component parts are smaller .” (Translated from French). http://tectonicablog.com/?p=34419

Galaganatha is a village south of Varada-Tungabhadra Sangama in Haveri district. In ancient inscriptions Galaganatha is referred to as Palluni.

Galagesvaragudi is a unique experiment of Kalyani Chalukyan temple architecture. The temple is east facing and situated on the bank of river Tungabhadra. The temple tapers right from its base to the top of the Shikhara. This temple is under the care of Archaeological Survey of India.

The temple can be entered from 3 sides.

Galagesvara temple of Galaganatha.

A pillar close to temple's southern entrance. If this pattern of temple design situating skambha lingas close to the temples can be extrapolated to Dholavira times, it is possible to explain the presence of two skambhas on the Dholavira 'theatre' as memorials close to the circules of stones which may have constituted menhir-stones in memory of the departed ancestors; and hence, the two pillars might have constituted two memorial pillars venerating the departed ātman, the pitṛ-s.![]()

A pillar close to temple's southern entrance. If this pattern of temple design situating skambha lingas close to the temples can be extrapolated to Dholavira times, it is possible to explain the presence of two skambhas on the Dholavira 'theatre' as memorials close to the circules of stones which may have constituted menhir-stones in memory of the departed ancestors; and hence, the two pillars might have constituted two memorial pillars venerating the departed ātman, the pitṛ-s.

A hero-stone leaning on a Shivalinga.![]()

![]()

A collection of Shivalinga. In the back ground is river Tungabhadra river in Bellary district.I suggest that these are hieroglyphs signifying pillars of light: tã̄bṛā, tambira (Prakritam) Rebus: tamba, 'copper' (Meluhha. Indian sprachbund)See: three stumps on Sit Shamshi bronze. [kūpa -- 2, stambha -- ] G. kuvātham m. ʻ mast of a ship ʼ.(CDIAL 3403) *ṭhōmba -- . 1. G. ṭhobrũ ʻ ugly, clumsy ʼ.2. M. ṭhõb m. ʻ bare trunk, boor, childless man ʼ, thõbā m. ʻ boor, short stout stick ʼ (LM 340 < stambha -- ).(CDIAL 5514) Rebus: tamba, 'copper' (Meluhha. Indian sprachbund) Numeral three: kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.The entire message of Sit Shamshi is bronze is worship of the sun. The message signifies copper metalwork. It is significant that one of the meanings to the Meluhha gloss sūrya is: copper: சூரியன் cūriyaṉ , n. < sūrya. Mountain containing copper; செம்புமலை. (W.)Sit-Shamshi (Musée du Louvre, París). Tabla de bronce que parece resumir sabiamente el ritual del antiguo Elam. Los zigurats recuerdan el arte mesopotámico, el bosque sagrado alude a la devoción semita por el árbol verde, la tinaja trae a la mente el “mar de bronce”. Los dos hombres en cuclillas hacen su ablución para celebrar la salida del Sol. Una inscripción, que lleva el nombre del rey Silhak-in-Shushinak, permite fijar su datación en el siglo XII a.C."The texts mention the "temples of the grove," cave sanctuaries where ceremonies related to the daily renewal of nature were accompanied by deposition of offerings, sacrifice and libations. The Sit Shamshi is perhaps a representation. It is also possible that this object is a commemoration of the funeral ceremonies after the disappearance of the sovereign. Indeed, this model was found near a cave, and bears an inscription in Elamite where Shilhak-Inshushinak remember his loyalty to the lord of Susa, Inshushinak. The text gives the name of the monument, the Sit Shamshi, Sunrise, which refers to the time of day during which the ceremony takes place." Source: http://www.3dsrc.com/antiquiteslouvre/index.php?rub=img&img=236&cat=10![]() Kalibangan fire-altars. In one pit, a cylindrical clay stele was found. Could such steles located in many ancient archaeological sites, denote skambha of Atharvaveda? Such stele were 30-40 cms. in height and 10-15 cms. in diameter, and formed the centrepoint of the hearths (Lal, BB 1984, Some reflections on the structural remains at Kalibangan in inIndus civilization: New perspectives, AH Dani ed.: 57).

Kalibangan fire-altars. In one pit, a cylindrical clay stele was found. Could such steles located in many ancient archaeological sites, denote skambha of Atharvaveda? Such stele were 30-40 cms. in height and 10-15 cms. in diameter, and formed the centrepoint of the hearths (Lal, BB 1984, Some reflections on the structural remains at Kalibangan in inIndus civilization: New perspectives, AH Dani ed.: 57).

Dholavira Excavation Report (April 2015) provides details of the finds of six polished stone pillars with two illustrations and a write-up:

Fig. 8.304. Freestanding columns in situ

"8.9.2.2 Free standing columns. At least six examples of freestanding columns were discovered from the excavations. Three freestanding columns are tall and slender pillars with circular cross-section and with a top resembling a phallus or they are phallic in nature. That is why most of them were found in an intentionally damaged and smashed condition. The phallus is depicted realistically with even the drawing of foreskin shown clearly. Two of these freestanding columns are found near eastern end of high street of Castle. These columns measure nearly 1.5m in height and are found at the strategic location of entering into the high street from the east gate of Castle. These two columns are placed in such a manner at the beginning of high street that they divide the street into three equal parts. The other freestanding columns of the same variety and typology, numbering four were found in a completely smashed and broken condition. Two of such columns were found in a secondary condition, fitted as a masonry of Tank A while the other one was found in a masonry in a later period structure near the western fortification of Castle. Two more examles, completely smashed and destroyed ones were also found, one near the western end of Ceremonial Ground and the second near the north gate of Castle. The destruction and desecration of these columns can be equated with that of the damage caused to the stone statue, which clearly indicates a change in ideology and traditions, customs after the Harappan phase."(pp. 589-591) http://asi.nic.in/pdf_data/dholavira_excavation_report_new.pdf

![]()

![]()

![]() A pair of Skambha in Dholavira close to kole.l'smithy, temple' ( (8-shaped stone structure): Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy.(DEDR 2133).Hieroglyph: tamba 'pillar'; tambu id. (Sindhi) Rebus: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper' (Prakritam)

A pair of Skambha in Dholavira close to kole.l'smithy, temple' ( (8-shaped stone structure): Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy.(DEDR 2133).Hieroglyph: tamba 'pillar'; tambu id. (Sindhi) Rebus: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper' (Prakritam)![]() One side of a Mohenjo-daro prism tablet (Full decipherment of the three sided inscription is embedded). What was the cargo carried on the boat? I suggest that the cargo was Meluhha metalwork -- castings and hard copper alloy ingots. Together with the pair of aquatic birds, the metalwork is with hard alloys (of copper).karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) Alternative:

One side of a Mohenjo-daro prism tablet (Full decipherment of the three sided inscription is embedded). What was the cargo carried on the boat? I suggest that the cargo was Meluhha metalwork -- castings and hard copper alloy ingots. Together with the pair of aquatic birds, the metalwork is with hard alloys (of copper).karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) Alternative:

Hieroglyph: tamar ‘palm’ (Hebrew) Rebus: tam(b)ra ‘copper’ (Santali)

dula ‘pair’ Rebus: dul ‘cast metal’ (Santali) Thus, together, dul tam(b)ra 'copper casting'.

A hero-stone leaning on a Shivalinga.

A collection of Shivalinga. In the back ground is river Tungabhadra river in Bellary district.

I suggest that these are hieroglyphs signifying pillars of light: tã̄bṛā, tambira (Prakritam) Rebus: tamba, 'copper' (Meluhha. Indian sprachbund)

See: three stumps on Sit Shamshi bronze. [kūpa -- 2, stambha -- ] G. kuvātham m. ʻ mast of a ship ʼ.(CDIAL 3403) *ṭhōmba -- . 1. G. ṭhobrũ ʻ ugly, clumsy ʼ.2. M. ṭhõb m. ʻ bare trunk, boor, childless man ʼ, thõbā m. ʻ boor, short stout stick ʼ (LM 340 < stambha -- ).(CDIAL 5514) Rebus: tamba, 'copper' (Meluhha. Indian sprachbund) Numeral three: kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

The entire message of Sit Shamshi is bronze is worship of the sun. The message signifies copper metalwork. It is significant that one of the meanings to the Meluhha gloss sūrya is: copper: சூரியன் cūriyaṉ , n. < sūrya. Mountain containing copper; செம்புமலை. (W.)

Sit-Shamshi (Musée du Louvre, París). Tabla de bronce que parece resumir sabiamente el ritual del antiguo Elam. Los zigurats recuerdan el arte mesopotámico, el bosque sagrado alude a la devoción semita por el árbol verde, la tinaja trae a la mente el “mar de bronce”. Los dos hombres en cuclillas hacen su ablución para celebrar la salida del Sol. Una inscripción, que lleva el nombre del rey Silhak-in-Shushinak, permite fijar su datación en el siglo XII a.C.

"The texts mention the "temples of the grove," cave sanctuaries where ceremonies related to the daily renewal of nature were accompanied by deposition of offerings, sacrifice and libations. The Sit Shamshi is perhaps a representation. It is also possible that this object is a commemoration of the funeral ceremonies after the disappearance of the sovereign. Indeed, this model was found near a cave, and bears an inscription in Elamite where Shilhak-Inshushinak remember his loyalty to the lord of Susa, Inshushinak. The text gives the name of the monument, the Sit Shamshi, Sunrise, which refers to the time of day during which the ceremony takes place." Source: http://www.3dsrc.com/antiquiteslouvre/index.php?rub=img&img=236&cat=10

Kalibangan fire-altars. In one pit, a cylindrical clay stele was found. Could such steles located in many ancient archaeological sites, denote skambha of Atharvaveda? Such stele were 30-40 cms. in height and 10-15 cms. in diameter, and formed the centrepoint of the hearths (Lal, BB 1984, Some reflections on the structural remains at Kalibangan in inIndus civilization: New perspectives, AH Dani ed.: 57).

Kalibangan fire-altars. In one pit, a cylindrical clay stele was found. Could such steles located in many ancient archaeological sites, denote skambha of Atharvaveda? Such stele were 30-40 cms. in height and 10-15 cms. in diameter, and formed the centrepoint of the hearths (Lal, BB 1984, Some reflections on the structural remains at Kalibangan in inIndus civilization: New perspectives, AH Dani ed.: 57).Dholavira Excavation Report (April 2015) provides details of the finds of six polished stone pillars with two illustrations and a write-up:

Fig. 8.304. Freestanding columns in situ

"8.9.2.2 Free standing columns. At least six examples of freestanding columns were discovered from the excavations. Three freestanding columns are tall and slender pillars with circular cross-section and with a top resembling a phallus or they are phallic in nature. That is why most of them were found in an intentionally damaged and smashed condition. The phallus is depicted realistically with even the drawing of foreskin shown clearly. Two of these freestanding columns are found near eastern end of high street of Castle. These columns measure nearly 1.5m in height and are found at the strategic location of entering into the high street from the east gate of Castle. These two columns are placed in such a manner at the beginning of high street that they divide the street into three equal parts. The other freestanding columns of the same variety and typology, numbering four were found in a completely smashed and broken condition. Two of such columns were found in a secondary condition, fitted as a masonry of Tank A while the other one was found in a masonry in a later period structure near the western fortification of Castle. Two more examles, completely smashed and destroyed ones were also found, one near the western end of Ceremonial Ground and the second near the north gate of Castle. The destruction and desecration of these columns can be equated with that of the damage caused to the stone statue, which clearly indicates a change in ideology and traditions, customs after the Harappan phase."(pp. 589-591) http://asi.nic.in/pdf_data/dholavira_excavation_report_new.pdf

A pair of Skambha in Dholavira close to kole.l'smithy, temple' ( (8-shaped stone structure): Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy.(DEDR 2133).

A pair of Skambha in Dholavira close to kole.l'smithy, temple' ( (8-shaped stone structure): Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy.(DEDR 2133).Hieroglyph: tamba 'pillar'; tambu id. (Sindhi) Rebus: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper' (Prakritam)

One side of a Mohenjo-daro prism tablet (Full decipherment of the three sided inscription is embedded). What was the cargo carried on the boat? I suggest that the cargo was Meluhha metalwork -- castings and hard copper alloy ingots. Together with the pair of aquatic birds, the metalwork is with hard alloys (of copper).

One side of a Mohenjo-daro prism tablet (Full decipherment of the three sided inscription is embedded). What was the cargo carried on the boat? I suggest that the cargo was Meluhha metalwork -- castings and hard copper alloy ingots. Together with the pair of aquatic birds, the metalwork is with hard alloys (of copper).karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) Alternative:

Hieroglyph: tamar ‘palm’ (Hebrew) Rebus: tam(b)ra ‘copper’ (Santali)

dula ‘pair’ Rebus: dul ‘cast metal’ (Santali) Thus, together, dul tam(b)ra 'copper casting'.

Śrīvatsa, an abiding cultural, metallurgical wealth continuum![]() ŚrīvatsaSilver coin of the Kuninda Kingdom, c. 1st century BCE. Obv: Deer standing right, crowned by two cobras, attended byLakshmi holding a lotus flower. Legend in Prakrit (Brahmi script, from left to right): Rajnah Kunindasya Amoghabhutisya maharajasya ("Great King Amoghabhuti, of the Kunindas"). Rev: Stupa surmounted by the Buddhist symbol triratna, and surrounded by a swastika, a "Y" symbol, and a tree in railing. Legend in Kharoshti script, from righ to left: Rana Kunidasa Amoghabhutisa Maharajasa, ("Great King Amoghabhuti, of the Kunindas").

ŚrīvatsaSilver coin of the Kuninda Kingdom, c. 1st century BCE. Obv: Deer standing right, crowned by two cobras, attended byLakshmi holding a lotus flower. Legend in Prakrit (Brahmi script, from left to right): Rajnah Kunindasya Amoghabhutisya maharajasya ("Great King Amoghabhuti, of the Kunindas"). Rev: Stupa surmounted by the Buddhist symbol triratna, and surrounded by a swastika, a "Y" symbol, and a tree in railing. Legend in Kharoshti script, from righ to left: Rana Kunidasa Amoghabhutisa Maharajasa, ("Great King Amoghabhuti, of the Kunindas").

Kuninda (or Kulinda in ancient literature) was an ancient centralHimalayan kingdom from around the 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century, located in the modern state of Uttarakhand and southern areas of Himachal in northern India.

![Triratna symbol on the reverse (left field) of a coin of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (r.c. 35-12 BCE):]() Triratna (Srivatsa) symbol on the reverse (left field) of a coin of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (r.c. 35-12 BCE

Triratna (Srivatsa) symbol on the reverse (left field) of a coin of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (r.c. 35-12 BCE

![]() Coin of Zeionises (c. 10 BCE – 10 CE). Obv: King on horseback holding whip, with bow behind. Corrupted Greek legend MANNOLOU UIOU SATRAPY ZEIONISOU "Satrap Zeionises, son of Manigul". Buddhist Triratna symbol. Rev:King on the left, receiving a crown from a city goddess holding a cornucopia. Kharoshthi legend MANIGULASA CHATRAPASA PUTRASA CHATRAPASA JIHUNIASA "Satrap Zeionises, son of Satrap Manigul". South Chach mint.

Coin of Zeionises (c. 10 BCE – 10 CE). Obv: King on horseback holding whip, with bow behind. Corrupted Greek legend MANNOLOU UIOU SATRAPY ZEIONISOU "Satrap Zeionises, son of Manigul". Buddhist Triratna symbol. Rev:King on the left, receiving a crown from a city goddess holding a cornucopia. Kharoshthi legend MANIGULASA CHATRAPASA PUTRASA CHATRAPASA JIHUNIASA "Satrap Zeionises, son of Satrap Manigul". South Chach mint.

Zeionises was an Indo-Scythian satrap of the area of southern Chach (Kashmir) for king Azes II.Necklaces with a number of pendants

aṣṭamangalaka hāra

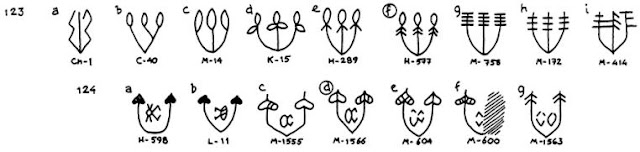

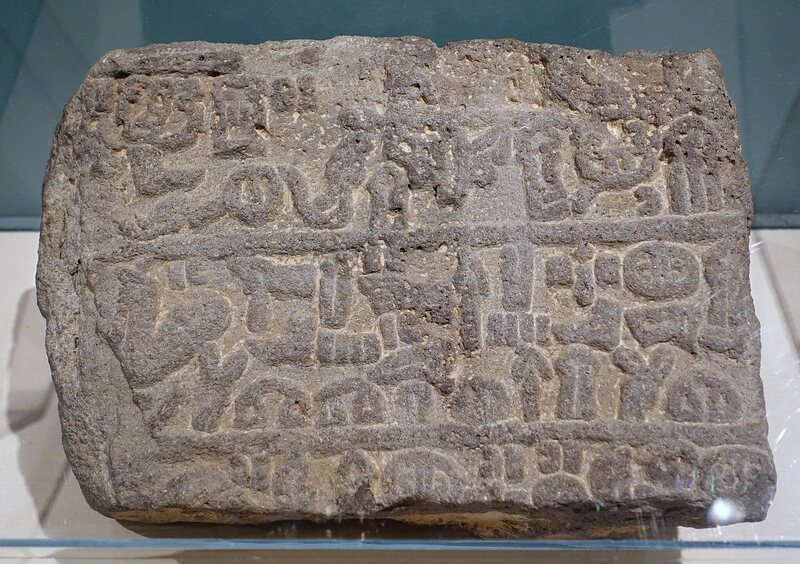

aṣṭamangalaka hāra depicted on a pillar of a gateway(toran.a) at the stupa of Sanchi, Central India, 1st century BCE. [After VS Agrawala, 1969, Thedeeds of Harsha (being a cultural study of Bāṇa’s Harṣacarita, ed. By PK Agrawala, Varanasi:fig. 62] The hāra or necklace shows a pair of fish signs together with a number of motifsindicating weapons (cakra, paraśu,an:kuśa), including a device that parallels the standard device normally shown in many inscribed objects of SSVC in front of the one-horned bull. •

Necklaces with a number of pendants

aṣṭamangalaka hāra

aṣṭamangalaka hāra depicted on a pillar of a gateway(toran.a) at the stupa of Sanchi, Central India, 1st century BCE. [After VS Agrawala, 1969, Thedeeds of Harsha (being a cultural study of Bāṇa’s Harṣacarita, ed. By PK Agrawala, Varanasi:fig. 62] The hāra or necklace shows a pair of fish signs together with a number of motifsindicating weapons (cakra, paraśu,an:kuśa), including a device that parallels the standard device normally shown in many inscribed objects of SSVC in front of the one-horned bull.

•

(cf. Marshall, J. and Foucher,The Monuments of Sanchi, 3 vols., Callcutta, 1936, repr. 1982, pl. 27).The first necklace has eleven and the second one has thirteen pendants (cf. V.S. Agrawala,1977, Bhāratīya Kalā , Varanasi, p. 169); he notes the eleven pendants as:sun,śukra, padmasara,an:kuśa, vaijayanti, pan:kaja,mīna-mithuna,śrīvatsa, paraśu,

darpaṇa and kamala. "The axe (paraśu) and an:kuśa pendants are common at sites of north India and some oftheir finest specimens from Kausambi are in the collection of Dr. MC Dikshit of Nagpur."(Dhavalikar, M.K., 1965, Sanchi: A cultural Study , Poona, p. 44; loc.cit. Dr.Mohini Verma,1989, Dress and Ornaments in Ancient India: The Maurya and S'un:ga Periods,Varanasi, Indological Book House, p. 125).

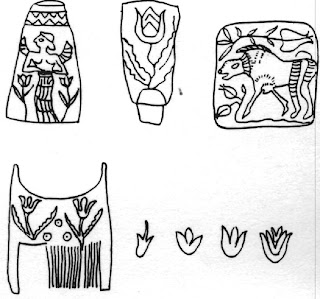

[CBK001] Karshapana of Chutus - Mulananda

, Lead karshapana. Zebu. Brahmi legend: Maharathi putasa sudakana (kanhasa) Krishna Six arched hill with crescent, wavy line below, nandipada,

poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite ferrite ore'meTTu 'mound' rebus: meD 'iron' kuThAru 'crucible' rebus: kuThAru 'armourer'kANDa 'water' rebus: kaNDa 'implements'kammaṭa 'mint'sattva 'svastika' rebus: jasta 'zinc'

Taxila, Uninscribed die-struck Coin (200-150 BC), MIGIS-4 type 578, 3.94g. Obv: Lotus standard flanked by banners in a railing, with two small three-arched hill symbols on either side. Rev: Three-arched hill with crescent above a bold 'open cross' symbol.

![FIG. 20. ANCIENT INDIAN COIN. (Archæological Survey of India, vol. x., pl. ii., fig. 8.)]() Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.

Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.

The Migration of Symbols, by Goblet d'Alviella, [1894

(Archæological Survey of India, vol. x., pl. ii., fig. 8.)

kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.

Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.The Migration of Symbols, by Goblet d'Alviella, [1894

(Archæological Survey of India, vol. x., pl. ii., fig. 8.)

kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

![]() Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.![An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre, from Mathura]() The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum.

The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum.

![An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre and inscription below, from Mathura]() An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre and inscription below, from Mathura. "Photograph taken by Edmund William Smith in 1880s-90s of a Jain homage tablet. The tablet was set up by the wife of Bhadranadi, and it was found in December 1890 near the centre of the mound of the Jain stupa at Kankali Tila. Mathura has extensive archaeological remains as it was a large and important city from the middle of the first millennium onwards. It rose to particular prominence under the Kushans as the town was their southern capital. The Buddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet. The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum." http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/photocoll/a/largeimage58907.html

An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre and inscription below, from Mathura. "Photograph taken by Edmund William Smith in 1880s-90s of a Jain homage tablet. The tablet was set up by the wife of Bhadranadi, and it was found in December 1890 near the centre of the mound of the Jain stupa at Kankali Tila. Mathura has extensive archaeological remains as it was a large and important city from the middle of the first millennium onwards. It rose to particular prominence under the Kushans as the town was their southern capital. The Buddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet. The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum." http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/photocoll/a/largeimage58907.html![]()

![]() View of the Jaina stupa excavated at Kankali Tila, Mathura.

View of the Jaina stupa excavated at Kankali Tila, Mathura.![]() Manoharpura. Svastika. Top of āyāgapaṭa. Red Sandstone. Lucknow State Museum. (Scan no.0053009, 0053011, 0053012 ) See: https://www.academia.edu/11522244/A_temple_at_Sanchi_for_Dhamma_by_a_k%C4%81ra%E1%B9%87ik%C4%81_sanghin_guild_of_scribes_in_Indus_writing_cipher_continuum

Manoharpura. Svastika. Top of āyāgapaṭa. Red Sandstone. Lucknow State Museum. (Scan no.0053009, 0053011, 0053012 ) See: https://www.academia.edu/11522244/A_temple_at_Sanchi_for_Dhamma_by_a_k%C4%81ra%E1%B9%87ik%C4%81_sanghin_guild_of_scribes_in_Indus_writing_cipher_continuum

![]()

Ayagapata (After Huntington)

![]()

Jain votive tablet from Mathurå. From Czuma 1985, catalogue number 3. Fish-tail is the hieroglyph together with svastika hieroglyph, fish-pair hieroglyph, safflower hieroglyph, cord (tying together molluscs and arrow?)hieroglyph multiplex, lathe multiplex (the standard device shown generally in front of a one-horned young bull on Indus Script corpora), flower bud (lotus) ligatured to the fish-tail. All these are venerating hieroglyphs surrounding the Tirthankara in the central medallion.

The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum.

An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre and inscription below, from Mathura. "Photograph taken by Edmund William Smith in 1880s-90s of a Jain homage tablet. The tablet was set up by the wife of Bhadranadi, and it was found in December 1890 near the centre of the mound of the Jain stupa at Kankali Tila. Mathura has extensive archaeological remains as it was a large and important city from the middle of the first millennium onwards. It rose to particular prominence under the Kushans as the town was their southern capital. The Buddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet. The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum." http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/photocoll/a/largeimage58907.html

View of the Jaina stupa excavated at Kankali Tila, Mathura.

View of the Jaina stupa excavated at Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Manoharpura. Svastika. Top of āyāgapaṭa. Red Sandstone. Lucknow State Museum. (Scan no.0053009, 0053011, 0053012 ) See: https://www.academia.edu/11522244/A_temple_at_Sanchi_for_Dhamma_by_a_k%C4%81ra%E1%B9%87ik%C4%81_sanghin_guild_of_scribes_in_Indus_writing_cipher_continuum

Ayagapata (After Huntington)

Jain votive tablet from Mathurå. From Czuma 1985, catalogue number 3. Fish-tail is the hieroglyph together with svastika hieroglyph, fish-pair hieroglyph, safflower hieroglyph, cord (tying together molluscs and arrow?)hieroglyph multiplex, lathe multiplex (the standard device shown generally in front of a one-horned young bull on Indus Script corpora), flower bud (lotus) ligatured to the fish-tail. All these are venerating hieroglyphs surrounding the Tirthankara in the central medallion.

Kushana period, 1st century C.E.From Mathura Red Sandstone 89x92cm

![]()

"Note that both begin with a lucky svastika. The top line reads 卐 vīrasu bhikhuno dānaṃ - i.e. "the donation of Bhikkhu Vīrasu." The lower inscription also ends with dānaṃ, and the name in this case is perhaps pānajāla (I'm unsure about jā). Professor Greg Schopen has noted that these inscriptions recording donations from bhikkhus and bhikkhunis seem to contradict the traditional narratives of monks and nuns not owning property or handling money. The last symbol on line 2 apparently represents the three jewels, and frequently accompanies such inscriptions...Müller [in Schliemann(2), p.346-7] notes that svasti occurs throughout 'the Veda' [sic; presumably he means the Ṛgveda where it appears a few dozen times]. It occurs both as a noun meaning 'happiness', and an adverb meaning 'well' or 'hail'. Müller suggests it would correspond to Greek εὐστική (eustikē) from εὐστώ (eustō), however neither form occurs in my Greek Dictionaries. Though svasti occurs in the Ṛgveda, svastika does not. Müller traces the earliest occurrence of svastika to Pāṇini's grammar, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, in the context of ear markers for cows to show who their owner was. Pāṇini discusses a point of grammar when making a compound using svastika and karṇa, the word for ear. I've seen no earlier reference to the word svastika, though the symbol itself was in use in the Indus Valley civilisation.[unquote]

1. Cunningham, Alexander. (1854) The Bhilsa topes, or, Buddhist monuments of central India : comprising a brief historical sketch of the rise, progress, and decline of Buddhism; with an account of the opening and examination of the various groups of topes around Bhilsa. London : Smith, Elder. [possibly the earliest recorded use of the word swastika in English].

2. Schliemann, Henry. (1880). Ilios : the city and country of the Trojans : the results of researches and discoveries on the site of Troy and through the Troad in the years 1871-72-73-78-79. London : John Murray.

http://jayarava.blogspot.in/2011/05/svastika.html

![]()

"Note that both begin with a lucky svastika. The top line reads 卐 vīrasu bhikhuno dānaṃ - i.e. "the donation of Bhikkhu Vīrasu." The lower inscription also ends with dānaṃ, and the name in this case is perhaps pānajāla (I'm unsure about jā). Professor Greg Schopen has noted that these inscriptions recording donations from bhikkhus and bhikkhunis seem to contradict the traditional narratives of monks and nuns not owning property or handling money. The last symbol on line 2 apparently represents the three jewels, and frequently accompanies such inscriptions...Müller [in Schliemann(2), p.346-7] notes that svasti occurs throughout 'the Veda' [sic; presumably he means the Ṛgveda where it appears a few dozen times]. It occurs both as a noun meaning 'happiness', and an adverb meaning 'well' or 'hail'. Müller suggests it would correspond to Greek εὐστική (eustikē) from εὐστώ (eustō), however neither form occurs in my Greek Dictionaries. Though svasti occurs in the Ṛgveda, svastika does not. Müller traces the earliest occurrence of svastika to Pāṇini's grammar, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, in the context of ear markers for cows to show who their owner was. Pāṇini discusses a point of grammar when making a compound using svastika and karṇa, the word for ear. I've seen no earlier reference to the word svastika, though the symbol itself was in use in the Indus Valley civilisation.[unquote]

1. Cunningham, Alexander. (1854) The Bhilsa topes, or, Buddhist monuments of central India : comprising a brief historical sketch of the rise, progress, and decline of Buddhism; with an account of the opening and examination of the various groups of topes around Bhilsa. London : Smith, Elder. [possibly the earliest recorded use of the word swastika in English].

2. Schliemann, Henry. (1880). Ilios : the city and country of the Trojans : the results of researches and discoveries on the site of Troy and through the Troad in the years 1871-72-73-78-79. London : John Murray.

http://jayarava.blogspot.in/2011/05/svastika.html

Khandagiri caves (2nd cent. BCE) Cave 3 (Jaina Ananta gumpha). Fire-altar?, śrivatsa, svastika(hieroglyphs) (King Kharavela, a Jaina who ruled Kalinga has an inscription dated 161 BCE) contemporaneous with Bharhut and Sanchi and early Bodhgaya.

![Related image]()