This monograph is an account of Yupa inscriptions, most of which were found on sites on the

banks of Vedic River Sarasvati mostly in Rajasthan. Yupa inscriptions were also found in

Indonesia ascribed to the reign of King Mulavarman in Kutai kingdom.

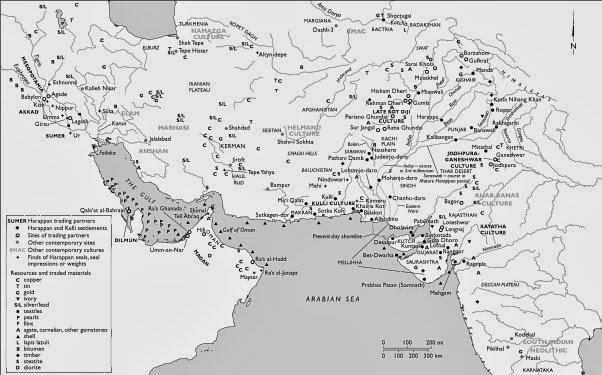

Yupa inscriptions are a continuum of the Indus Script tradition of documenting metalwork catalogues with documentation of wealth distributed to the participants and performers of specific Yajna-s such as as'vamedha, agniSToma. This continuum lends credence to the possibility that Soma yajna did not involve a herbal but a mineral consistent with the synony of Soma, ams'u which has a Tocharian cognate, ancu, 'iron'.

![]()

Knot in a Brahmi inscription, Gujarat with the same hieroglyph as shown on Indus Script Corpora metalwork catalogues. This hieroglyph of 'knot' signifies:

dhāu 'rope' rebus: dhāu 'metal' PLUS मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’. Thus, metallic ore. mēdhḥमेधः 1 A sacrifice, as in नरमेध, अश्वमेध, एकविंशति- मेधान्ते Mb.14.29.18. (com. मेधो युद्धयज्ञः । 'यज्ञो वै मेधः' इति श्रुतेः ।).An offering, oblation

![]() Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph. Mohejodaro, tablet in bas relief (M-478) The first hieroglyph-multiplex on the left (twisted rope): dhāu 'rope' rebus: dhāu 'metal' PLUS मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’. Thus, metallic ore.

Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph. Mohejodaro, tablet in bas relief (M-478) The first hieroglyph-multiplex on the left (twisted rope): dhāu 'rope' rebus: dhāu 'metal' PLUS मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’. Thus, metallic ore.

Hieroglyph: मेढा [mēḍhā] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ 'iron, copper' (Munda. Slavic) mẽṛhẽt, meD 'iron' (Mu.Ho.Santali)

meď 'copper' (Slovak)

Santali glosses:

Wilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like

"Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of

Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien".

(DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic

handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities

have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer,

some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages.

One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.).

The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper'

in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.)

of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:

Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.

Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'.

~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).

Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.

Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.

KW <i>mENhEd</i>

@(V168,M080)

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

The remrkable feature of the Yupa inscriptions are that they are in Samskritam. Patanjali comments on the nature of mleccha mispronunciations in the context of evaluation of such inscriptions in Samskritam.

Seals have also been found on the fire-altars associated with the Yupa inscriptions.

A hieroglyph hypertext on Kalibangan terracotta cake in a yajna kuNDA is a person holding a tiger tied to a rope. This hieroglyph-multiplex has been deciphered as related to metalwork.

bhaTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

koD 'horn' rebus: koD 'workshop'

kola 'tiger' rebus: kolle 'blacksmith', kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'

Thus, the terracotta cake inscription signifies a iron workshop smelter/furnace and smithy.

This Indus Script tradition of inscribed records as metalwork catalogues on seals and terracotta cakes continues in the historical periods as Yupa inscriptions of Rajasthan and Indonesia detailing the types of yajna-s performed commemorated by the Yupa inscriptions.

The Yupa inscriptions are recorded on large-sized yaSTi of the type found in Binjor, Kalibangan, Lothal.

Indus Script Corpora are catalogues of metalwork recorded in mleccha, the spoken version of later-day languages of Indian Sprachbund. Yupa Inscriptions are records of yajna-s performed in Samskritam, the litearary version of later-day languages of Indian Sprachbund.

This continuum of fire-worship tradition evidenced by metalwork catalogues and fire-worship in Yajna-s points to the possibility that some of the yajna-s were metalwork processes involving fire-altars and producing varieties of metals such as soma (electrum) or gold (suvarNam); inscriptions indicate that wealth was distributed by yajamAna or rulers such as GajAyana SarvatAta or Pushyamitra, to the priests and participants of the yajna-s.

One Yupa inscription of Mulavarman, Kutai kingdom, Indonesia refers to suvarNam, gold. Candi-Sukuh inscribed Sivalinga (6 ft. tall Yupa) may also be evaluated in this tradition of metalwork since the Candi-Sukuh linga has an inscription which refers to Gangga sudhi 'purification by portable furnace, kanga'.

According to the Allahabad Yupainscription, in 2nd century CE, a village was assigned by the king to a

minister who donated it to a priest. (Epigraphia Indica, (EI), XXVII, no. 43, lines 8-9, also

see cf. EI, XXIV, no. 34, p. 252).

“Patanjali deplores the barbarisms of his time, for example, the 'wrong' words for 'cow' (gAvI, goNI, gotA, gopotalikA), which he includes among the 'many debased' (apabhrams'a) forms of the 'few' correct words. Based on the evidence of the inscriptions, this describes the linguistic situation perfectly. Or, he complains about the wrong pronunciation of the three s-sounds of Sanskrit that had collapsed nearly everywhere in north India into one phoneme – a factor that, incidentally, again points to MathurA, where it is seen in inscriptions of brahmins. His advice therefore is not to talk like the barbarians (mleccha). The Sanskrit of his time is exemplified by the first known Sanskrit inscription, the Ayodhya stone inscription (Sircar 1965: 94 no. 9), which is a ittleFrom the beginning of our era (S'o(m)DAsa, circa 1 to 25 CE, Sircar 1965: 114 sqq, Luders, 1961), the Mathura stone inscription (Sircar no 26) or the Kushana time Isapur Yupa inscription (Sircar 1965: 149 no. 47A).”(Austin Patrick Olivelle, 2006, Between the empires: society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE, OUP, USA).

“In the Mahabhashya, Patanjali refers to sacrifices performed for...iha Pushyamitram YajayAmah: 'here we perform the sacrifices for Pushyamitra'. This is supported by the Ayodhya inscription of Dhanadeva (JBORS, X, p. 203 I,2), which records the performance of two As'vamedha sacrifices by Pushyamitra and the MalavikAgnimitra of Kalidasa. The Mahabhashya also refers to different types of sacrifices – AgnishToma, RajasUya, Vajapeya, and the domestic ones – Pakayajna or Panchayajna, accessories needed in such sacrifices, their duration, the benefits that accrued from their performances, and lastly, the priests required for them, who received handsome dakshiNAs. Patanjali also mensions the Yupas, which were associated with Vedic sacrifices. The S'unga-SAtavAhana-S'aka Period. During this period, sacrifices were performed, and the yupas (sacrificial posts) were erected at important places...In the second or first century BCE, GajAyana SarvatAta performed an As'vamedha sacrifice at MadhyamikA (EI, XVI, p.27; EI, XXIII, p.198). From the NandsA yupa inscription of VS 282 (226 CE)(EI, XXVII, pp.252 ff; IHQ, XXIX, p.80), it is known that the Malava leader Nandisoma of the Sogin clan, performed the EkashashTirAtra sacrifice to proclaim the independence of his republic. From the BarNAla inscription f 228 CE, it is known that a king, whose name ended in Varddhana, erected seven yupas (EI, XXVI, pp. 118ff.) The reference to the group of seven yupas may show that the king had performed seven sacrifices. Another yupa inscription foud here, commemorates a sacrifice performed fifty-one years later. This inscription, of 279 CE, commemorates the performance of five TrirAtra, or perhaps GargatrirAtra, sacrifices by a BrAhmaNa. The Maukharis of BaDvA also championed the Vedic religion. In 293 CE, MahAsenApati Bala and his three sons performed a TrirAtra sacrifice (EI, XXIII, pp. 42-52). From the inscription of VakATaka copper plates, it is known that the BhAras'ivas under BhavanAga performed as many as ten as'vamedhas and won the Ganges water by their prowess. KP Jayaswal rightly concluded that they must have flourished from about the beginning of the third century CE, and celebrated their As'vamedhas to commemorate their conquest of the Gangetic valley, after the expulsion of the KushANas. (History of India, 150-350 CE). At Vidis'A, the remains of some olf YajnakuNDas or sacrificial pits of the second or third century CE have been discovered, and they prove that Vidis'a was a great centre of the Vedic religion. (ASI, 1914-15, p.75). These are of exceptional interest because nowhere else have such remains been found. Near them, two drains were found, connected with the sacrificial pits. On the levels of the KuNDas and the brick pavement, the walls of two structures were discovered, which were intended to be spacious halls constructed for accommodating a large number of people gathered for sacrifice. These sacrifices instituted by kings or wealthy YajamAnas of the ancient times lasted for months, and some for years, and for their adequate performance, halls of permanent structure were as much a necessity as the kuNDas themselves. A sacrificial site was always a meeting place for Rishis, Yajnikas and distinguished guests of the sacrificer. The hall excavated in the south of the KuNDas served the purpose of a dining hall or for feasting, and the other huge and extensive hall was meant for the carrying on of philosophical debates. Some seals connected with the sacrificial site have been discovered. On some of them, the words hotA, potA and mantra, which are technical to sacrificial literature, have been carved. The sealings have been classified under four heads, viz., – 1) rulers, 2) officials, 3) private individuals, and 4) passport. Only two seals of the first class were found. One of these gives the name of Vis'vAmitra as the name of a ruler not so far known from any epigraphic or literary source. Of the three sealings of the second class, two belong to two different daNDanAyakas or police officers, and one to an officer haya-hasty-adhikArI (in charge of elephants and horses). There are also seals of private individuals. All these persons were followers of the Vedic religion. The seals of passport were meant for admitting persons to the sacrificial hall.”(Kailash chand Jain, 1972, Malwa through the ages, from the earliest times to 1305 AD', Dehi, Motilal Banarsidass, pp 192-194).

Barnala yupa inscription, hybrid Samskritam. Vidarbha Yupa coin 100 BCE with Indus Script hieroglyph mēḍhā ‘stake’ rebus: meḍ ‘iron’

Association of yupa hieroglyph on coins from mints of Vidarbha or Ujjain is an indicator of the correlation which can be traced between a smelter/furnace in a smithy/forge and a sacred fire-altar of a yajna.

Badva yupa inscription

EI, v.XXIV, No. 34.-FOURTH MAUKHARI YUPA INSCRIPTION FROM BADVA.

A. S. ALTEKAR.

TEXT.

Mîkharår=Hastè-puttrasya Dhanuttràtasya dhèmataõ [|*]

Aptî[r]yy[a]mía[õ] kratîõ yópaõ sahasrî gava-dakshiíà [|*]

__________________________

From an ink impression.

L. 1. Read Hasti-; owing to the carelessness of the mason, the three letters in dhanuttrà have been all joined together.

L. 2. Read -tîr=yópaõ; read sahasra-gava-dakøiíaõ.

That the Barnala Yupa inscription is hybrid Samskritam is demonstrated attesting to the continuity of Prakritam (spoken Meluhha) in the ancient writing traditions associated with yajna or metalwork.

Source: Theo Damsteegt, 1978, Epigraphical Hybrid Sanskrit, Brill Archive, pp. 145-146

Vidarbha, Sebaka, 100 BC, Copper, 1.70g, 12mm, Bull with Yupa (sacrificial post)

Obv: Standing bull to right facing yupa-in-railing; swastika below

Rev: Double-orbed Ujjain symbol with swastika and nandi-pad above

Ujjain, anonymous AE 3/8 karshapana, elephant type

Weight: 3.75 gm., Diameter: 16x14 mm.

Obv.: Elephant with raised trunk to right with chakra on top left;

(railed) tree on right.

Rev.: Ujjain symbol with a taurine in each angle.

Reference: Pieper 362 (plate specimen)

Ujjain, 200 BC, Copper, 0.9g, 10mm, Horse (Bull?) type

mēḍhā ‘stake’ rebus: meD 'iron' poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite ore' jasta 'svastika' rebus: sattva 'zinc, spelter' dhAv 'strand of rope' (dotted circle) rebus: dhA 'red ore, dhAtu 'ore' meDh 'twist' rebus: meD 'iron', med 'copper' (Slavic) gaNDa 'four' rebus: kanda 'fire-altar'

kariba 'elephant trunk' ibha 'elephant' rebus: karb 'iron' ib 'iron'

kuThi 'twig' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

Samudragupta, Gold Dinar, 7.70g, Ashvamedha type![]() Obv: Sacrificial horse facing left tied to a Yupa or post, decorated with ribbons and banners fluttering above; letter ’Si’ (short for 'siddham' or success) in Brahmi between the horse’s leg and double pedestal stand;Rev: Queen standing left on a lotus holding chauri (fly whisk) and vastra (towel); a suchi (ceremonial spear with ribbons) in left field; Brahmi legend to right: Asvamedha Parakramah (one who is capable of performing the horse-sacrifice)Ref: BMC pl.V,-1, Altekar pl. IV-1; P. Kulkarni, Asvamedha the Yajna and the Coins, 1.

Obv: Sacrificial horse facing left tied to a Yupa or post, decorated with ribbons and banners fluttering above; letter ’Si’ (short for 'siddham' or success) in Brahmi between the horse’s leg and double pedestal stand;Rev: Queen standing left on a lotus holding chauri (fly whisk) and vastra (towel); a suchi (ceremonial spear with ribbons) in left field; Brahmi legend to right: Asvamedha Parakramah (one who is capable of performing the horse-sacrifice)Ref: BMC pl.V,-1, Altekar pl. IV-1; P. Kulkarni, Asvamedha the Yajna and the Coins, 1.

kulya 'fly whisk' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' mēḍhā ‘stake, pillar’ rebus: meD 'iron'

Malt. kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) Rebus: kāṇḍa 'metalware' kaṇḍa 'fire-altar'.

si (brahmi syllable) = siddha. siddhi f. ʻ accomplishment, success ʼ MBh., ʻ supernatural powers ʼ Sāṁkhyak. [√sidh2] Pa. siddhi -- f. ʻ accomplishment ʼ, KharI. sidhi; Pk. siddhi -- f. ʻ completion, magic power ʼ; K. sĕd f. ʻ success, superhuman power ʼ; S. sidhī f. ʻ miracle ʼ; P. siddh f. ʻ straight course ʼ; Ku.gng. śidi ʻ success ʼ, Mth. sidhi; H. sīdh, sīdhī f. ʻ straightness, direct line, aim ʼ; Si. idi ʻ completion, work, superhuman power ʼ. (CDIAL 13405)

Isapur Yupa inscription (102 CE, dated in year 24 in Kushana king Vasishka's reign) indicates performance of a sattra (yajna) of dvadasarAtra, 'twelve nights'. (Vogel, JP, The sacrificial posts of Isapur, Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, 1910-11: 40-8).

Vajapeya is one of 7 samstha (profession) for processing/smelting soma (a mineral, NOT a herbal): सोमः [सू-मन् Uṇ.1.139]-संस्था a form of the Soma-sacrifice; (these are seven:- अग्निष्टोम, अत्यग्निष्टोम, उक्थ, षोढशी, अतिरात्र, आप्तोर्याम and वाजपेय). The Vajapeya performed in Binjor and Balibangan should have been related to the Soma-samstha: सोमः संस्था specified as वाजपेय with the shape of the yupa with eight- or four-angles.

सं-√ स्था a [p=1121,2]A1. -तिष्ठते ( Pa1n2. 1-3 , 22 ; ep. and mc. also P. -तिष्ठति ; Ved. inf. -स्थातोस् A1pS3r. ) , to stand together , hold together (pf. p. du. -तस्थान्/ए , said of heaven and earth) RV. ; to build (a town) Hariv. ; to heap , store up (goods) VarBr2S. occupation , business , profession

W. At the Vājapeya, the yūpa is eight-angled (as in Binjor), corresponding to the eight quarers (Sat.Br. V.2.1.5

aSTās'rir yūpo bhavati) अश्रि [p=

114,2]

f. the sharp side of anything , corner , angle (of a room or house) , edge (of a sword)

S3Br. Ka1tyS3r.often ifc. e.g. अष्टा*श्रि , त्रिर्-/अश्रि , च्/अतुर्-श्रि , शता*श्रि q.v. (cf. अश्र) ;([cf. Lat. acies , acer ; Lith. assmu3]).

The shape seen commonly in all the shapes of yupa of Isapur is that they are octagonal (eight angles). The shape matches with the drawing based on Vedic texts by Madeleine Biardeau.

The vedic text which specifies the octagonal shape of the yupa is Satapatha Brahmana.

Sbr. V.2.1.9: While setting up the ladder, the yajñika says to his wife, 'Come, let us go up to Heaven'. She answers, 'Let us go up'. (Sbr V.2.1.9) and they begin to mount the ladder. At the top, while touching the head of the post, the yajñika says: 'We have reached Heaven' (Taittiriya Samhita, SBr. Etc.) 'I have attained to heaven, to the gods, I have become immortal' (Taittiriya samhita 1.7.9) 'In truth, the yajñika makes himself a ladder and a bridge to reach the celestial world' (Taittiriya Samhita VI.6.4.2)

Eggeling' translation of Sbr. Pt III, Vol. XLI, Oxford, 1894, p.31 says:

“The post is either wrapped up or bound up in 17 cloths for Prajapati is 17-fold.' The top of the Yupa carries a wheel called cas'Ala in a horizontal position. The indrakila too is adorned with a wheel-ike object made of white cloth, but it is placed in a vertical position.

Notes taken from 'The symbolism of the Indrakila' Senarat Paranavitana, Leelananda Prematilleka, Johanna Engelberta van Lohulzen-De Leeuw, 1978, Senarat Paranavitana Commemoration Volume, BRILL 1978, p.247)

Vedic, Indus Script traditions: अष्टाश्रि 'having eight corners' Satapatha Brahmana about yupa as 'course of action, support' in Soma Yaga agni kunda

Indus Script hieroglyphs read rebus relate to yajna of Vedic tradition celebrated on hundreds of examples signified on punch-marked and early cast coins of ancient Bharatam. I suggest that the eight-spoked wheel and yupa signify the Vedic tradition of yupa skambha with अष्टाश्रि 'having eight corners' to signify Soma Yaga. Often, together with yupa in a railing, a tree is also signified on a railing on early coins from mints from all over Bharatam from Taxila to Karur. The tree as hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. This is also shown on Sohgaura copper plate inscription of pre-Mauryan times. (Note embedded with reference to JF Fleet's article in JRAS, 1907).

अष्टा* श्रि [p= 117,1] mfn. having eight corners SBr.(Monier-Williams) áśri f. ʻ sharp side, corner, angle, edge ʼ ŚBr. 2. -- aśra- in cmpds.1. Pa. Pk. aṁsi -- f., Pk. assi -- f.; P. assī f. ʻ sharp edge of anything ʼ; Or. ã̄siā ʻ having angles ʼ; Si. äs, ähä ʻ corner, angle ʼ; -- Pr. čū ʻ corner ʼ? 2. Pa. assa -- m. corner; Si. asa ʻ side ʼ, ahak ʻ aside ʼ; -- in apposition with descendants of pārśva -- : S. āsi -- pāsi ʻ on all sides ʼ, L. āsse -- pāsse, P. āsī˜ -- pāsī˜ (ā frompās -- ); -- N. Ku. B. ās -- pās, Or. āsa -- pāsa, H. ās -- pās, M. āśī˜ -- pāśī˜.

aṣṭāśri -- , cáturaśri -- . (CDIAL 918) अस्रिः asriḥअस्रिः 1 An angle; अष्टास्रयः सर्व एव श्लक्ष्णरूपसमन्विताः Rām.1.14.26.-2 Ten million; see अश्रि. āśri अस्रिः asriḥअस्रिः 1 An angle; अष्टास्रयः सर्व एव श्लक्ष्णरूपसमन्विताः Rām.1.14.26.-2 Ten million; see अश्रि. āśri आश्रि 1 U. 1 (a.) To resort or betake oneself to; to have recourse to (a place, way, course of action &c.); विचरितमृगयूथान्याश्रयिष्ये वनानि V.5.17; निम्नगां आश्रयन्ते Rs.1.27; दक्षिणां मूर्तिमाश्रित्य K.128,132; न वयं कुमारमाश्रयामहे Mu.4; आशिश्राय च भूतलम् Bk.14.111 fell on the ground; 17.92; वृत्तिमाश्रित्य वैतसीम् R.4.35 resorting to or following; so धैर्यम्, शोकम्, बलम्, मित्रभावम्, संस्कृतमाश्रित्य &c.; आश्रित्य having recourse or reference; तामाश्रित्य M.4.1, कतमत्प्रकरणमाश्रित्य गीयताम् Ś.1. (b) To seek refuge with, dwell with or in, inhabit (as a place &c.); शरण्यमेनमाश्रयन्ते R.13.7; Pt.1.51; तथा गृहस्थमाश्रित्य वर्तन्ते सर्व आश्रमाः Ms.3.77; सर्वे गुणाः काञ्चन- माश्रयन्ते. -2 To go through, experience; एको रसः ... पृथक् पृथगिवाश्रयते विवर्तान् U.3.47. -3 To rest or depend upon. -4 To adhere or stick to, fall to the lot of, happen, occur; पापमेवाश्रयेदस्मान् Bg.1.36 we shall incur sin. -5 To choose, prefer. -6 To assist, help.

Mulawarman Yupa inscriptions

“The first yupa inscription of Mulavarman was erected to commemorate a bahu-suvarnaka sacrifice,'that on which gold is spent in profusion'. If the inscription can be taken literally, it points up the value of gold in the Southeast Aian world fo the fifth century. Another records that Mulavarman 'had given a gift (dAnam) of a thousand kine and a score the twice-born (i.e. the brAhmaNas)....(consequently) for that deed of merit (puNyasya) thi sacrificial post (yupo) has been made...A third inscription is similar: 'Let the foremost amongst the priests and whatsoever other pious men (there be) hear of the meritorious deed (puNyam) of Mulavarman the king of illustrious and resplendent fame – (let them hear) of his great gift (bahudAna), his gift of cattle (?)(jivadAna), his gift of a wonder-tree (kalpavRkSam), hs gift of land (bhUmidAna). For these multitudes of pious deeds (puNyaganam) this sacrificial post has been set up by the priests.' It is the duty of men of prowess to give liberally of their substance so as to acquire greater wealth and status, thereby initiating an endless cycle of giving at all levels of society. It is also imperative that these meritorious deeds be properly recorded. In the second and third inscriptions, there is an expressed linkage between the giving of gifts (dAna) and the acquisition of merit (puNya). To record these pious acts a sacrificial post (yupa) was erected. What we have, then, is action on the temporal plane that was meant to have eternal impact in the sense that Mulavarman was building his field of merit.” (Robert S. Wicks, 1992, Money, markets and trade in early Southeast Asia: the development of indigenous monetary systems to AD 1400, SEAP Publications, Cornell, Ithaca, NY, p.245; loc. Cit. Mulavarman's First Yupa Inscription; FH van Naerssen, and RC longh, The economic and administrative history of early Indonesia, Leiden: Brill, 1977), p. 20; J. Ph. Vogel, 'The Yupa inscription of Mulavarman from Koelei (East Borneo)', Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde 79, 1918: 213; Mulavarman's Second Yupa Inscription, Vogel, 'Yupa Inscriptions', p. 214; Mulavarman's Third Yupa Inscription; Vogel, 'Yupa Inscriptions', p. 215.)

“Kutai Kingdom was the oldest Hindu Kingdom in Indonesia placed in Muara Karman, East Borneo. This inscription formed Yupa, a stone pillar that is used to bind the victim in the form of animals or humans to be sacrificed to the gods. There are seven Yupa which contains the inscription, but only 4 were successfully read and translated. This inscription use Pallawa Pre-Nagari letters and in Sanskrit, which is estimated from the shape and type dating from around 400 AD.

... Contents of Mulawarman Inscription

Fill Yupa first inscription mentions that the first king of the kingdom of Kutai is Kudungga. Kudungga which is the original name of Indonesia at that time showed that he was not the founder of the royal family. Additionally, Yupa mention also that during the reign of Asmawarman in Kutai Kingdom Aswamedha ceremony held. This ceremony is a ceremony of release of the horse to determine the boundaries of the empire Kutai.

Mulwarman Inscription I

The Maharaja Kundunga, very noble, has a son of the renowned, namely the Aswawarman, which like the Amshuman (sun god) grow very noble family. The Aswawarman have three sons, such as fire (holy) three. Leading off the third son is the Mulawarman, civilized king good, strong and powerful. The Mulawarman has held receptions (salvation called) gold very much. Create a memorial feast (salvation) that stone monument was established by the brahmins.

A Yupa with inscription in the National Museum of Indonesia in Jakarta

Overall, contents of Mulawarman Inscription tell about Mulawarman that contribute to the Brahmans form the many cows. Mulawarman mentioned as the grandson of Kudungga, and children from Aswawarman. This inscription is evidence of the oldest of the Hindu kingdoms in Indonesia. Kutai name is commonly used as the name of this kingdom though not mentioned in the inscription, because the inscriptions found in Kutai, precisely in the upper Mahakam River.

Mulawarman Inscription IV

The Mulawarman, the noble king and foremost, giving alms 20,000 cows to the the brahmins

who such as fire, (located) in the holy land (named) Waprakeswara. Create (warning)

will favor the king's goodness, this monument was created by the Brahmins

who came to this place.

http://www.ocfinid.com/2015/04/the-oldest-inscription-in-indonesia.html

Four of seven yupa inscriptions of Mulavarman (Title: Maharaja Kundunga Anumerta Dewawarman,

kingdom of Kutai Martadipura) in Samskrtam have been translated.

Three yupa inscriptions are not legible.

![]()

"Kutai Martadipura Kingdom is the first Hindu kingdom in Indonesia ( Nusantara ) which has the oldest historical evidence. It was established at around the 4th century. The kingdom is located in Muara Kaman, East Kalimantan, precisely in the Mahakam river. "

Kutai Martadipura Kingdom Area

![Another Kutai Yupa Inscription]()

Another Kutai Yupa inscriptionhttp://hubpages.com/education/Kutai-Kingdom

Sources: From the third century CE, Samskritam inscriptions on Yupa have been found from Badva (SI I.91-2) and Barnala (EI 26, 118-23) in Rajasthan. The dating formula is in kRtehi, that is, kRta = Vikrama years.

Fourth Maukhari Yupa inscription from Badva, AS Altekar, EI 23, 1935-36, 42-52; Epigraphica Indica, Vol. 24, no. 34, 1937-38, pp. 251-53; SI I.91-2, 90, 182

Barnala (Jaipur Dist. Rajasthan) yupa inss., kRta (=Vikrama) 284 and 335 = CE 223 and 229; AS Altekar, EI 26, 1941-42, 118-23. 90.

Dange, Sadashiv A. "The yUpa - its nature and evolution." BhAratI.

Vol.16(1985-1987) pp.1-10

Sahoo, P. C. "On the yUpa in the BrAhmaNa texts." Bulletin of the

Deccan College Research Institute. Vol. 54/55(1994/1995) pp.175-183.

Upadhyaya, Vibha. "Yupa Inscription" in R.K. Sharma & Devendra Handa

(eds). Revealing India's Past: Recent Trends in Art and Archaeology

(Prof. Ajay Mitra Shastri Commemoration Volume - 2 vols.) Aryan Books

International [2005] pp.233-247 ISBN 81-7305-289-1

EI XXIII: #7: 42-52: A.S.Atlekar, Three Mukhari Inscriptions on Yupas,kRta year 295. (Stone yuupas begin ca. 2nd CE, innovation over the wooden ones, from Buddhist pillars: Garga-triraatra ritual, an amalgam of agniSToma, ukhthya, and atiraatra.)

EI XXIV: #33: 245-251: A.S.Atlekar, Allahabad Museum YupaInscription:Sivadatta's saptasomasaMstha

EI XXIV: #34: 251-253: A.S.Atlekar, Fourth Yupa Inscription from Badva,3rd CE: aaptoryaama ritual

EI XXVII: #43: 252-267: A.S.Atlekar, Nanda Yupa Inscriptions, kRtayear 282: a 61-day sattra (!) ekazaSTiraatra

B. Ch. Chhabra, "Yuupa Inscriptions", in India Antiqua (Fel. Vol. J. Ph. Vogel, Leiden 1947).

Note: I realise that some images of docs are illegible. The URL links are given for improved readability. Hopefuly, in due course, the ancient docs related to EI, CII etc. will be keyed in afresh in Unicode. Sorry for the inconvenience caused. Kalyan

Evidence of yupa in Kalibangan (quadrangular yupa) and Binjor (octagonal yupa) for वाजपेय, Indus Script Corpora as metalwork catalogues, Yupa inscriptions in India and East Borneo“Vedic literature such as the Apastamba Srautasutra (VII. 2. 13–15), mentions that a sacrificial post called yupa, which should be as high as the person who is sacrificing, standing with or without raised hands or standing on a chariot has to be erected at the eastern side of the altar and the animal to be sacrificed was tied to this yupa. The text also says that the yupa has to be eight cornered and tapering at the top. “(Sen, C., 1976, A dictionary of the Vedic rituals based on the Sraut and Grihya Sutras , New Delhi: Comcept Publishing Company, p. 101) http://www.ancient-asia-journal.com/articles/10.5334/aa.78/ loc.cit. S. Krishnamurthy and Sachin Kr. Tiwary, 2016, Origin, development and decline of monolithic pillars and the continuity of the tradition in polylithic, non-lithic and structural forms, Ancient Asia, 7

Kalibangan and Binjor archaeological sites have provided evidence of yupa in fire-altars, together with Indus Script inscriptions which are relatable to the significance of yupa in metalwork.

Kalibangan yupa is quadrangle shaped, with 4 angles. Binjor yupa is octagonal shaped, with 8 angles. Both shapes are consistent with the Vedic tradition of the shape of the yupas related to Vajapeya soma yajña.

Since Soma is not a herbal but a metal [relatable as synonym ams'u to cognate ancu 'iron' (Tocharian)], th Vajapeya soma yajña can also be evaluated, in an archaeometallurgical framework, as a smelting process in fire-altars.

Yupa inscriptions of early centuries of the Common Era are divided into two categories, both related to vedic yajña-s: 1. Huna (Kushana) & Rajasthan yupa inscriptions from ca. 100 CE; 2. Pallava and Mulavarman yupa inscriptions found in Kutei, East Borneo ca. 400 CE.

In the context of evidence of yupa in Kalibangan and Binjor fire-altars, these yupa inscriptions of the historical periods can be seen as a continuum of Indus Script documentation tradition. Indus Script documented metalwork catalogues. Yupa inscriptions of the historical periods specify types of yajñas performed which can be related to metalwork (smeting soma) as in the case of vajapaye yajña performed in Kalibangan and Binjor with 4-angled and 8-angled yupa. The expression bahusuvarNaka used in a Mulavarman yupa inscription indicates the possibility that soma as electrum (gold-silver compound) was smelted resulting in the production of gold coins (in mints). Candi Sukuh evidence of sivalinga as a signifier of lokhaNDa 'metal implements' also reinforces the link of some yajña-s with metalwork.

![]() Isapur yupa 102 CE. Mathura Museum.(Courtesy: Pataru Maurya); discovered by Rai Bahadur Pt. Radha Krishna in 1910 from the bed of river Yamuna near village of Ishapur, opposite Vishrant Ghat, Uttar Pradesh . It commemorates Dwadasa-sattra sacrifice (a Vedic ritual lasting for 12 days symbolising the yearly course of the Sun) (Agrawal, V S ,1939, Handbook of the sculpture in the Curzon museum of Archaeology Muttra In: Allahabad: Department of Printing and Stationary, pp. 25-16. )

Isapur yupa 102 CE. Mathura Museum.(Courtesy: Pataru Maurya); discovered by Rai Bahadur Pt. Radha Krishna in 1910 from the bed of river Yamuna near village of Ishapur, opposite Vishrant Ghat, Uttar Pradesh . It commemorates Dwadasa-sattra sacrifice (a Vedic ritual lasting for 12 days symbolising the yearly course of the Sun) (Agrawal, V S ,1939, Handbook of the sculpture in the Curzon museum of Archaeology Muttra In: Allahabad: Department of Printing and Stationary, pp. 25-16. )

Of the 19 yupa inscriptions, nine are from Rajasthan, five are from East Borneo (Indonesia) and the rest from regions such as Mathura and Allahabad. The list of 19 yupa inscriptions is as follows:

1 Isapur Mathura, 102 CE

2 Kosam-Allahabad 125 CE

3-4 Nandasa Udaipur 225 CE

5 Barnala Jaipur 227 CE

6-8 Badva Kotah 238 CE

9 Badva Kotah 238 CE

10 Nagar Jaipur 264 CE

11 Barnala Jaipur 278 CE

12 Bijayagarh Bharatpur 371 CE

13-16 Koetei Borneo 400 CE

17-19 Koetei Borneo 400 CE

![*]() "The inscribed stone is a sacrificial pillar, commemorating revival of the rituals during third century A.D. by the Malava Republic. The inscription records the erection of the pillar by Ahisarman, son of Dharaka who was Agnihotri. Ahisarman seems to be a Malava chief."

"The inscribed stone is a sacrificial pillar, commemorating revival of the rituals during third century A.D. by the Malava Republic. The inscription records the erection of the pillar by Ahisarman, son of Dharaka who was Agnihotri. Ahisarman seems to be a Malava chief."![*]()

![*]() Bichpuria.

Bichpuria.

Source: http://asijaipurcircle.nic.in/Yupa%20Pillars%20in%20Bichpuria%20temple,%20NAGAR.html

“…Malavas, Yaudheyas, Arjunayanas, Rajanyas etc...seem to have been patrons of Vedic sacrifices and rituals. Rajasthan witnessed the revival of Vedic religion under these people in the early centuries of the Common era and thus it was natural to get the largest number of inscribed yupa pillars (sacrificial posts) in various parts of Rajasthan. Dr. Satya Prakash discovered as early as in 1952, a yupa pillar inscribed in Brahmi script and dated Krita (Vikram) Samvat 321 (CD 264) from the village Bichpuria near Nagar (district Tonk) which records the performance of some sacrifice (name not specified) by Dharaka, who is styled as agnihotri. He brought to light this important epigraph and edited the same (Maru Bharti, Pilani, Vol. I, No. 2, February 1953). Rajasthan has provided the largest number of yupa pillars in the country of SaSthi-rAtra sacrifice, two pillars (now in Amber Museum) from Barnala (Jaipur) dated v.s. 284 (CE 227) recording the installation of seven yupa pillars by Vardhana and the second dated v.s. 335 (CE 278) referring to the TrirAtra sacrifice, four yupa pillars from Badva (now in Kotah Museum) three of them of the Maukhari dynasty ruling the area. The three inscribed yupa pillars record the performance of TrirAtr yajñas by Balavardhana, Somadeva and Bala Singh, the three sons of the commander-in-chief of the Maukhari kings. Each of them gave one hundred cows in gift on the occasion and installed sacrificial posts. The undated pillar belongs to DhanutrAta of the same dynasty who is credited with the performance of the AstoyAma yajna and putting up a yupa pillar in commemoration thereof. Sri ViSNuvardhana, son of the celebrated Yas'ovarman, performed puNdarIka yajña in the Malava era 428 (CE 371) and installed a yupa pillar at Vijaigarh (Bayana in Bharatpur region). Dr. Prakash studied in detail these incontrovertible evidences in his interesting paper 'Yupa pillars of Rajasthan' (JRIHR, Vol. IV, No. 2, April-June 1968) and evaluated their contribution in Rajasthan Through the Ages (Vol. 1, Chapter IV, 1966).” (Sharma, RG, 'History and Culture' in: Vijai Shankar Srivastava, ed., Abhinav Publications, 1981, Cultural Contours of India: Dr Satya Prakash Felicitation Volume, pp.81-82).

![]()

![]()

The erection of the sacrificial post by a brahmana of Bharadvaja gotra and recording of the performance of a sattra of twelve nights. (Heinrich Luders, 1912, A list of Brahmi inscriptions, no. 149a in: Epigraphia Indica, Appendix to Epigraphia Indica and Record of the Archaeological Survey of India, A List of Brahmi Inscriptions from the earliest times to about A.D. 400 with the exception of those of Asoka, Calcutta.)

Read on...

Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/zdqqnds

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

July 6, 2016

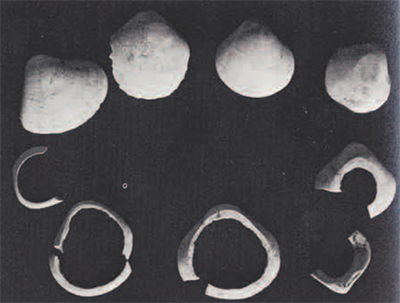

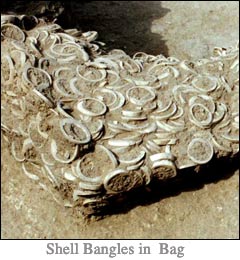

Balakot ceramic stoneware bangle blkt-6

Balakot ceramic stoneware bangle blkt-6

h419

h419

The zonal museum of archaeology in Hisar, Haryana. (Express photo by Jaipal Singh)

The zonal museum of archaeology in Hisar, Haryana. (Express photo by Jaipal Singh) Objects from the dig. (Express photo by Jaipal Singh)

Objects from the dig. (Express photo by Jaipal Singh) Mound 1 at Rakhigarhi. (Express photo by Jaipal Singh)

Mound 1 at Rakhigarhi. (Express photo by Jaipal Singh) The sarpanch of village Rakhi Khas, with his uncle and father.

The sarpanch of village Rakhi Khas, with his uncle and father.

.jpg)

Dwaraka. Turbinella pyrum, s'ankha seal with

Dwaraka. Turbinella pyrum, s'ankha seal with

Fortification surrounding the Great Bath, Mohenjo-daro.

Fortification surrounding the Great Bath, Mohenjo-daro.

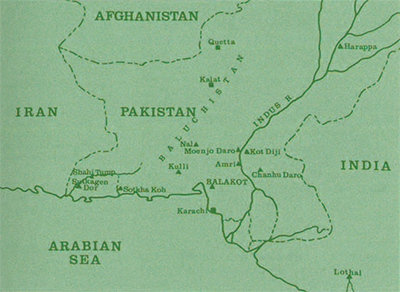

Makran coast (Balakot site) is an extension of the Persian Gulf in the Indian Ocean, jutting into the Rann of Kutch, Gujarat.See:

Makran coast (Balakot site) is an extension of the Persian Gulf in the Indian Ocean, jutting into the Rann of Kutch, Gujarat.See:

A cluster of Sarasvati civilization sites are west and east of the Makran Coast (Balakot): Shahi-Tump, SatkagenDor, Sokta Koh, Kulli, Chanhu Daro, Allah Dino, Dholavira, Pabumath, Zekda, Khirsara, Desalpur, Narapa, Konda Bhadli, Bhuj, Surkotada, Kanmer, Shikarpur, Bagasra (Gola Dhoro), Nagwada, Kuntsi, Nageshwar

A cluster of Sarasvati civilization sites are west and east of the Makran Coast (Balakot): Shahi-Tump, SatkagenDor, Sokta Koh, Kulli, Chanhu Daro, Allah Dino, Dholavira, Pabumath, Zekda, Khirsara, Desalpur, Narapa, Konda Bhadli, Bhuj, Surkotada, Kanmer, Shikarpur, Bagasra (Gola Dhoro), Nagwada, Kuntsi, Nageshwar

Kanmer

Kanmer

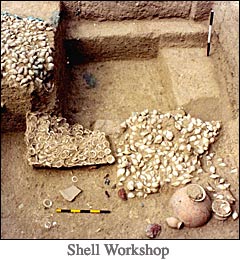

Series of excavated Meretrix shells showing successive stages of bangle manufacture (clockwise from upper left hand corner). Figure after Dales and Kenoyer, 1977

Series of excavated Meretrix shells showing successive stages of bangle manufacture (clockwise from upper left hand corner). Figure after Dales and Kenoyer, 1977

Kanmer sealings.

Kanmer sealings.

m1162. Mohenjo-daro seal with the same hieroglyph which appears on Kanmer circular tablets.

m1162. Mohenjo-daro seal with the same hieroglyph which appears on Kanmer circular tablets.

"

"

Seals and sealings, Gola Dhoro (Bagasra)

Seals and sealings, Gola Dhoro (Bagasra)

![[IMG]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fa/Indo-GreekMapColor.jpg)

![[IMG]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/08/Indo-Greek-territory_revision1.jpg)

Flying birds on Dong Son Bronze Drums

Flying birds on Dong Son Bronze Drums kanka 'heron'on Dong Son Bronze Drum tympanum.

kanka 'heron'on Dong Son Bronze Drum tympanum.

Santali glosses

Santali glosses

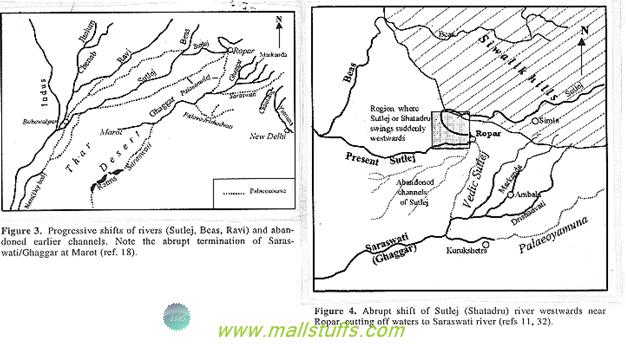

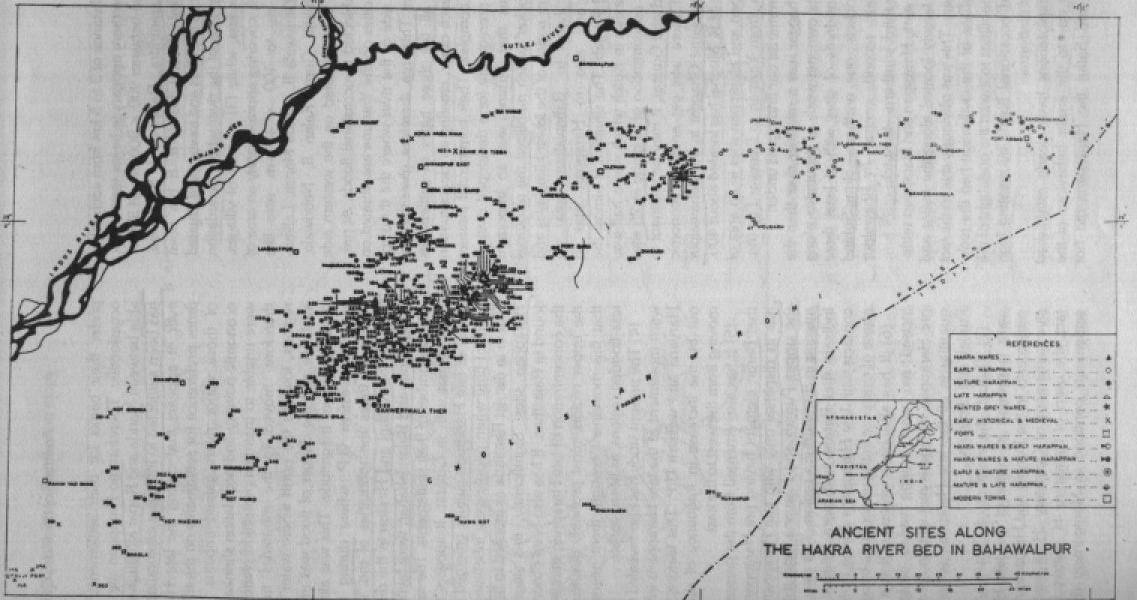

Reconstruction of Vedic River Sarasvati drainage (After KS Valdiya, 2012)

Reconstruction of Vedic River Sarasvati drainage (After KS Valdiya, 2012)

Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph.

Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph.

Isapur yupa 102 CE. Mathura Museum.

Isapur yupa 102 CE. Mathura Museum. "

".jpg)

%20(3).jpg)

%20(4).jpg) Bichpuria.

Bichpuria.

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' PLUS Hieroglyph:

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' PLUS Hieroglyph: