Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/h24ueao

चषालः caṣāla on Yupa, made of wheat straw, an Indus Script hieroglyph, signifies pyrolysis/carburization in smelting ores into steel/hard alloys

Yupa is a kunda, a pillar of bricks. This kunda signifies a fire-alter or agnikunda in Vedic tradition. A signifier of the pillar is a चषालः caṣāla as its top piece. This चषालः caṣāla (Rigveda) is made of wheat straw for pyrolysis to convert firewood into coke to react with ore to create hard alloys, e.g. iron reacting with coke to create crucible steel or carburization of wrought iron in a crucible to produce steel. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crucible_steel

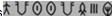

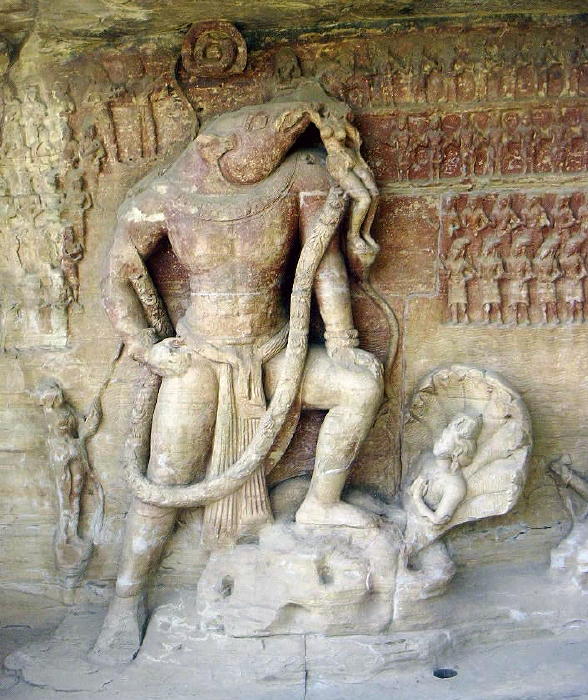

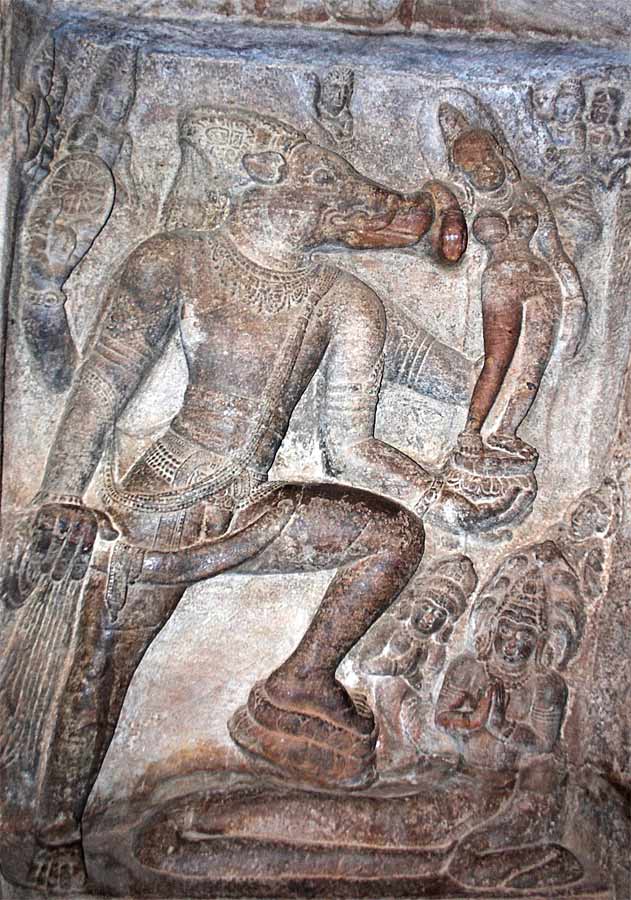

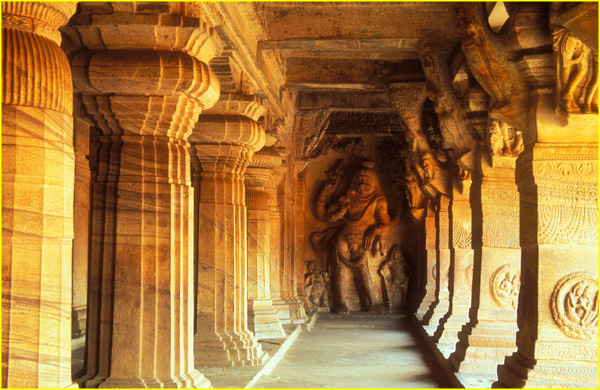

The sacredness associated with चषालः caṣāla is demonstrated by the architectural splendour of ancient varaha sculptures in the Hindu tradition. On the varaha monolith in Khajuraho, the चषालः caṣāla is signified by Devi Sarasvati. On many other sculptures of varaha, the चषालः caṣāla is associated with Mother Earth भूदेवी bhudevi. A gallery of varaha sculptural splendour is embedded together with explanatory notes on the dcipherment of metal work catalogue in a Rakhigarhi seal with a rhinoceros decorated with a scarf (dhatu 'scarf' rebus: dhatu 'ore').

The Indus Script hieroglyphic hypertexts get expanded into metaphors during the historical periods narrating Varaha as the third Avatara of Vishnu. In archaeometallurgical parlance, the चषालः caṣāla is the core pyrolysis process to create crucible steel and/or hard alloys in smelting processes.

See the yupa as a signifier on Kuwait gold disc with Indus Script hieroglyphs:

![]()

Hieroglyph: kunda = a pillar of bricks (Ka.); pillar, post (Tu.Te.); block, log (Malt.); kantu = pillar, post (Ta.)(DEDR 1723).

Rebus: kun.d. = a pit (Santali) kun.d.amu = a pit for receiving and preserving consecrated fire; a hole in the ground (Te.) kun.d.am, kun.d.a sacrificial fire

pit (Skt.) kun.d.a an altar on which sacrifices are made (G.)[i] gun.d.amu fire-pit; (Inscr.)

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/01/octagonal-yupo-bhavati-satapatha.html चषालः caṣāla is made of wheat straw according to Satapatha Brāhmana.

http://www.sanskritdictionary.com/agnir/961/6#sthash.aDu8onbZ.dpuf

"Pyrolysis has been used since ancient times for turning wood into charcoal on an industrial scale...Pyrolysis is used on a massive scale to turn coal into

coke for metallurgy, especially steelmaking."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrolysis In archaeometallurgical terms, the use of wheat straw to prepare the चषालः caṣāla fixed atop a Yupa may relate to such pyrolysis process to convert charcoal used in the fire-altar (furnace) into charcoal/coke to react with the dhAtu in the earth subjected to smelting/melting process (e.g. iron reacting with coke in a crucible to be transmuted as steel).

చషాలము [ caṣālamu ] chashālamu. [Skt.] n. A chalice, or cup used in sacrifice. A ring attached to the sacrificial post in a horse sacrifice.రాజ మాయము నందు యూపస్తంభమునకు అడుగున తగిలించే కడియము .څليَ ṯs̱alaey, s.m. (1st) A ring for the finger. 2. A pillar of mud or stones as a mark for land. 3. A butt or mark for arrows. 4. A mound or platform for watching a field. 5. A temporary building or shed. Pl. يِ ī. See منا (Pashto)

चषाल [p= 391,2]mn. (g. अर्धर्चा*दि) a wooden ring on the top of a sacrificial post RV. i , 162 , 6 TS. vi Ka1t2h.xxvi , 4 (चशाल) S3Br. &c चषालः caṣālḥचषालः 1 A wooden ring on the top of a sacrificial post; चषालं ये अश्वयूपाय तक्षति Rv.1.162.6; चषालयूपत- च्छन्नो हिरण्यरशनं विभुः Bhāg.4.19.19.-2 An iron ring at the base of the post.-3 A hive.

In lokokti, the yupa is associated with potaraju. The word pota signifies casting or smelting of metal.

పోతురాజు or పోతరాజు pōtu-rāḍsu. n. The name of a rustic god, like Pan, worshipped throughout the Telugu, Canarese and Mahratta countries. He represents the male principle associated with the village goddesses Gangamma, Peddamma, &c. A proverb says పాడుఊరికి మంచపుకోడుపోతురాజు in a ruined village the leg of a cot is a god. cf., 'a Triton of the minnows' (Shakespeare.) పోత [ pōta ] pōta. [Tel. from పోయు .] n. Pouring, పోయుట . Casting, as of melted metal. Bathing, washing. Eruption of the small pox. ఆకుపోత putting plants into the ground. పెట్టుపోతలు శాశ్వతములుకావు meat and drink (literally, feeding and bathing) are not matters of eternal consequence. పోత pōta. adj. Molten, cast in metal. పోతచెంబు a metal bottle or jug, which has been cast not hammered.

పోతము [ pōtamu ] pōtamu. [Skt.] n. A vessel, boat, ship.ఓడ . The young of any animal. పిల్ల. శిశువు . An elephant ten years old, పదేండ్ల యేనుగు . A cloth,వస్త్రము. శుకపోతము a young parrot. వాతపోతము a young breeze, i.e., a light wind. పోతపాత్రిక pōta-pātrika. n. A vessel, a ship, ఓడ . "సంసార సాగరమతుల ధైర్యపోత పాత్రికనిస్తరింపుముకు మార ." M. XII. vi. 222. పోతవణిక్కు or పోతవణిజుడు pōta-vaṇikku. n. A sea-faring merchant. ఓడను కేవుకు పుచ్చుకొన్నవాడు, ఓడ బేరగాడు . పోతవహుడు or పోతనాహుడు pōta-vahuḍu. n. A rower, a boatman, a steersman. ఓడనడుపువాడు, తండేలు .

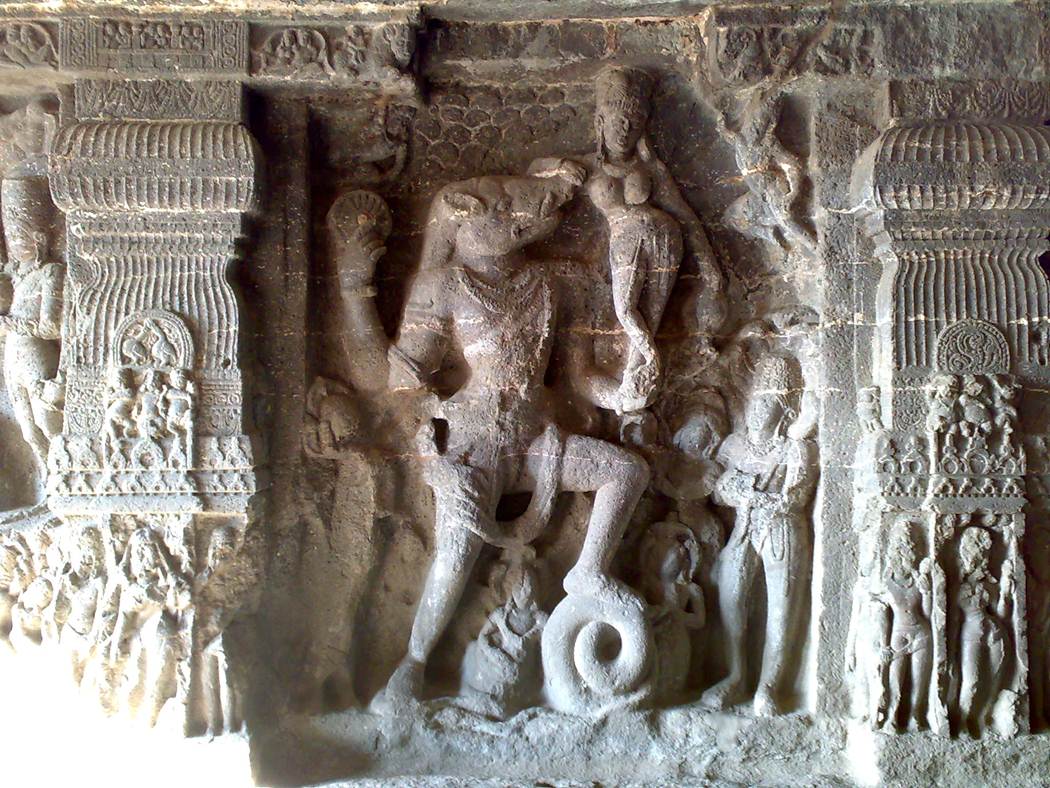

"Lord Vishnu appeared in the form of a Boar in order to defeat Hiranyaksha, a demon who had taken the Earth (Prithvi) and carried it to the bottom of what is described as the cosmic ocean in the story. The battle between Varaha and Hiranyaksha is believed to have lasted for a thousand years, which the former finally won. Varaha carried the Earth out of the ocean between his tusks and restored it to its place in the universe. Vishnu married Prithvi (Bhudevi) in this avatar.The Varaha Purana is a Purana in which the form of narration is a recitation by Varaha."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Varaha_Temple,_Khajuraho

वराह [p= 923,2]m. (derivation doubtful) a boar , hog , pig , wild boar RV. &c (ifc. it denotes , " superiority , pre-eminence " ; » g.व्याघ्रा*दि)N. of विष्णु in his third or boar-incarnation (cf. वराहा*वतार) TA1r. MBh. &c

वराह an array of troops in the form of a boar Mn. vii , 187 வராகம்² varākam

கட்டிவராகன் kaṭṭi-varākaṉ, n. < கெட்டி +. A gold coin, the varākaṉ. கட்டிலோ மெத் தையோ கட்டிவராகனோ. (குற்றா. குற.).கருக்குவராகன் karukku-varākaṉ, n. < id. +. New pagoda coin on which the figures are well defined; புதுநாணயம். (W .)தங்கவராகன் taṅka-varākaṉ, n. < தங்கம் +. Pagoda, a gold coin = 3½ rupees; 3½ ரூபாய் பெறுமான வராகன் என்னும் நாணயம்.வராகன்¹ varākaṉ, n. < Varāha. 1. Viṣṇu, in His boar-incarnation; வராகரூபியான திருமால். (பிங்.) 2. Pagoda, a gold coin = 3½ rupees, as bearing the image of a boar; மூன்றரை ரூபாய் மதிப்ள்ளதும் பன்றிமுத்திரை கொண்டதுமான ஒரு வகைப் பொன்நாணயம். (அரு. நி.)

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/07/devi-sarasvati-in-hindu-civilization.html

The Varaha shrine, built on a lofty plinth, is essentially similar in design to the Lalguan Mahadeva Temple, but is simpler and more modest. It is an oblong pavilion with a pyramidal roof of receding tiers, resting on fourteen plain pillars and enshrines a colossal monolithic (2.6 m long and 1.7 high) image of Yajna Varaha (incarnation of Vishnu) which is exquisitely finished to a glossy luster and is carved all over with multiple figures of gods and goddesses. The flat ceiling of the shrine is carved with a lotus flower of exquisite design in relief. The shrine built entirely of sandstone is assignable to circa 900-925. http://asibhopal.nic.in/monument/chhatarpur_khajuraho_varahatemple.html#

Sarasvati with veena in her hands is shown on the चषाल 'snout (of boar).'

चषालः caṣāla on Yupa, made of wheat straw, an Indus Script hieroglyph, signifies pyrolysis/carburization in smelting ores into steel/hard alloys

Yupa is a kunda, a pillar of bricks. This kunda signifies a fire-alter or agnikunda in Vedic tradition. A signifier of the pillar is a चषालः caṣāla as its top piece. This चषालः caṣāla (Rigveda) is made of wheat straw for pyrolysis to convert firewood into coke to react with ore to create hard alloys, e.g. iron reacting with coke to create crucible steel or carburization of wrought iron in a crucible to produce steel. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crucible_steel

The sacredness associated with चषालः caṣāla is demonstrated by the architectural splendour of ancient varaha sculptures in the Hindu tradition. On the varaha monolith in Khajuraho, the चषालः caṣāla is signified by Devi Sarasvati. On many other sculptures of varaha, the चषालः caṣāla is associated with Mother Earth भूदेवी bhudevi. A gallery of varaha sculptural splendour is embedded together with explanatory notes on the dcipherment of metal work catalogue in a Rakhigarhi seal with a rhinoceros decorated with a scarf (dhatu 'scarf' rebus: dhatu 'ore').

The Indus Script hieroglyphic hypertexts get expanded into metaphors during the historical periods narrating Varaha as the third Avatara of Vishnu. In archaeometallurgical parlance, the चषालः caṣāla is the core pyrolysis process to create crucible steel and/or hard alloys in smelting processes.

See the yupa as a signifier on Kuwait gold disc with Indus Script hieroglyphs:

Hieroglyph: kunda = a pillar of bricks (Ka.); pillar, post (Tu.Te.); block, log (Malt.); kantu = pillar, post (Ta.)(DEDR 1723).

Rebus: kun.d. = a pit (Santali) kun.d.amu = a pit for receiving and preserving consecrated fire; a hole in the ground (Te.) kun.d.am, kun.d.a sacrificial fire

pit (Skt.) kun.d.a an altar on which sacrifices are made (G.)[i] gun.d.amu fire-pit; (Inscr.)

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/01/octagonal-yupo-bhavati-satapatha.html चषालः caṣāla is made of wheat straw according to Satapatha Brāhmana.

| caṣāla चषाल This is a Rigveda word which signifies the top-piece of the Yūpa. 1.162.01 Let neither Mitra nor Varun.a, Aryaman, A_yu, Indra, R.bhuks.in,nor the Maruts, censure us; when we proclaim in the sacrifice the virtus of the swift horse sprung from the gods. [a_yu = va_yu (a_yuh satataganta_ va_yuh, vaka_ralopo va_); r.bhuks.in = Indra; but,here Praja_pati, he in whom the r.bhus,or the devas, abide (ks.iyanti); sprung from the gods: devaja-tasya = born as the type of various divinities, who are identified with different parts (e.g. us.a_ va_ as'vasya medhyasya s'irah: Br.hada_ran.yaka Upanis.ad 1.1.1); legend: the horse's origin from the sun, either direct, or through the agency of the Vasus: sura_d as'vam vasavo niratas.t.a]. 1.162.02 When they, (the priests), bring the prepared offering to the presence (of the horse), who has been bathed and decorated with rich (trappings), the various-coloured goat going before him, bleating, becomes an acceptable offering to Indra and Pu_s.an. [The prepared offering: ra_tim-gr.bhi_ta_m = lit. the seized wealth; the offering to be made for the horse; pu_s.an = Agni; the goat is to be tied to the front of the horse at the sacrificial post, such a goat, black-necked, kr.s.nagri_va (a_gneyah kr.s.n.agri_vah: Taittiri_ya Sam.hita_ 5.5.22), being always regarded as an a_gneya pas'u, or victim sacred to Agni, and to be offered to him (Ka_tya_yana Su_tra 98). A black goat is also dedicated to pu_s.an, along with soma (Yajus. xxix.58; but, he is also to be attached to the na_bhi or middle of the horse (Yajus. xxiv.1)]. 1.162.03 This goat, the portion of Pu+s.an fit for all the gods, is brought first with the fleet courser, to that Tvas.t.a_ may prepare him along with the horse, as an acceptable preliminary offering for the (sacrificial) food. [The portion of Pu_s.an: he is to be offered in sacrifice to Pu_s.an or Agni; Tvas.t.a_ = sarvasyotpa_daka, the producer of all forms; tvas.t.a_ ru_pa_n.i vikaroti (Taittiri_ya Sam.hita_ 1.5.92); or, identified wiith Agni;preliminary offering purod.a_s'am = offering of cakes and butter; purasta_d-da_tavyam, that which is to be first offered]. 1.162.04 When the priests at the season (of the ceremony), lead forth the horse, the offering devoted to the gods, thrice round (the sacrificial fire); then the goat, the portion of Pu_s.an, goes first, announcing the sacrificer to the gods. [The goat is to be first immolated]. 1.162.05 The invoker of the gods, the minister of the rite, the offerer of the oblation, the kindler of the fire, the bruiser of the Soma, the director of the ceremony, the saage (superintendent of the whole); do you replenish the rivers by this well-ordered, well-conducted, sacrifice. [The invoker of the gods: designations applied to eight of the sixteen priests employed at a solemn rite: the two first are: hota_ and adhvaryu; avaya_j = pratiprastha_ta_, who brings and places the offering; agnimindha = agni_dh, the kindler of the fire; gra_vagra_bha = the praiser of the stones that bruise the Soma,or he who applies the stones to that purpose; s'am.sta_ = pras'a_sta_; suvipra = Brahma_ (brahmaiko ja_te ja_te vidya_m vadatibrahma_ sarvavidyah sarva veditumarhati: Nirukta 1.8); replenish the rivers: vaks.an.a_ apr.n.adhvam, nadi_h pu_rayata, fill the rivers; the consequence of sacrifice being rain and fertility; or, it may mean, offer rivers of butter, milk, curds, and the like]. 1.162.06 Whether they be those who cut the (sacrificial) post, or those who bear the post, or those who fasten the rings on the top of the post, to which the horse (is bound); or those who prepare the vessels in which the food of the horse is dressed; let the exertions of them all fulfil our expectation. [The post: twenty-one posts, of different kinds of wood, each twenty-one cubits long, are to be set up, to which the different animals are to be fastened, amounting to three hundred and forty-nine, besides two hundred and sixty wild animals, making a total of six hundred and nine (Ka_tya_yana); the text seems to refer to a single post: cas.a_lam ye as'vayu_pa_ya taks.ati: cas.a_la = a wooden ring, or bracelet, on the top of the sacrificial post; or, it was perhaps a metal ring at the foot of the post]. Satapatha Brāhmana describes this as made of wheaten dough (gaudhūma). गौधूम [p= 369,3] mf(ई g. बिल्वा*दि)n. made of wheat MaitrS. i Hcat. i , 7 (f(आ).) made of wheat straw S3Br. v , 2 , 1 , 6 Ka1tyS3r. xiv , 1 , 22 and 5 , 7. |

"Pyrolysis has been used since ancient times for turning wood into charcoal on an industrial scale...Pyrolysis is used on a massive scale to turn coal into

coke for metallurgy, especially steelmaking."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrolysis In archaeometallurgical terms, the use of wheat straw to prepare the चषालः caṣāla fixed atop a Yupa may relate to such pyrolysis process to convert charcoal used in the fire-altar (furnace) into charcoal/coke to react with the dhAtu in the earth subjected to smelting/melting process (e.g. iron reacting with coke in a crucible to be transmuted as steel).

చషాలము [ caṣālamu ] chashālamu. [Skt.] n. A chalice, or cup used in sacrifice. A ring attached to the sacrificial post in a horse sacrifice.

चषाल [p= 391,2]mn. (g. अर्धर्चा*दि) a wooden ring on the top of a sacrificial post RV. i , 162 , 6 TS. vi Ka1t2h.xxvi , 4 (चशाल) S3Br. &c चषालः caṣālḥचषालः 1 A wooden ring on the top of a sacrificial post; चषालं ये अश्वयूपाय तक्षति Rv.1.162.6; चषालयूपत- च्छन्नो हिरण्यरशनं विभुः Bhāg.4.19.19.-2 An iron ring at the base of the post.-3 A hive.

In lokokti, the yupa is associated with potaraju. The word pota signifies casting or smelting of metal.

పోతము [ pōtamu ] pōtamu. [Skt.] n. A vessel, boat, ship.

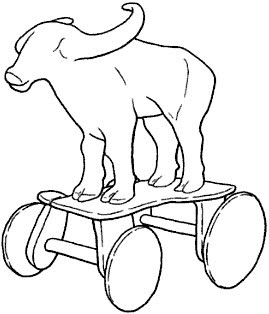

Shapes of Yupa: A. Commemorative stone yupa, Isapur – from Vogel, 1910-11, plate 23; drawing based on Vedic texts – from Madeleine Biardeau, 1988, 108, fig. 1; cf. 1989, fig. 2); C. Miniature wooden yupa and caSAla from Vaidika Samsodana Mandala Museum of Vedic sacrificial utensils – from Dharmadhikari 1989, 70) (After Fig. 5 in Alf Hiltebeitel, 1988, The Cult of Draupadi, Vol. 2, Univ. of Chicago Press, p.22)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Varaha_Temple,_Khajuraho

वराह [p= 923,2]m. (derivation doubtful) a boar , hog , pig , wild boar RV. &c (ifc. it denotes , " superiority , pre-eminence " ; » g.व्याघ्रा*दि)N. of विष्णु in his third or boar-incarnation (cf. वराहा*वतार) TA1r. MBh. &c

वराह an array of troops in the form of a boar Mn. vii , 187 வராகம்² varākam

, n. < varāka. Battle; போர். (யாழ். அக.)

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/07/devi-sarasvati-in-hindu-civilization.html

The Varaha shrine, built on a lofty plinth, is essentially similar in design to the Lalguan Mahadeva Temple, but is simpler and more modest. It is an oblong pavilion with a pyramidal roof of receding tiers, resting on fourteen plain pillars and enshrines a colossal monolithic (2.6 m long and 1.7 high) image of Yajna Varaha (incarnation of Vishnu) which is exquisitely finished to a glossy luster and is carved all over with multiple figures of gods and goddesses. The flat ceiling of the shrine is carved with a lotus flower of exquisite design in relief. The shrine built entirely of sandstone is assignable to circa 900-925. http://asibhopal.nic.in/monument/chhatarpur_khajuraho_varahatemple.html#

Sarasvati with veena in her hands is shown on the चषाल 'snout (of boar).'

Devi Sarasvati: in Hindu civilization. Sarasvati on the lip (snout) of a Varaha monolithic sculpture.

Devi Sarasvati

Why is Sarasvati shown on the upper lip (snout) of Varaha? Varaha is the 3rd avatar of Vishnu, rescuing the earth and the Vedas from the pralayam. Sarasvati on the lip of Varaha is a metaphor for Vaak and Vedas (Knowledge).

Varaha is Veda purusha, the avatar who ensured the continued prevalence of the Knowledge embodied in the Vedas.

Shaft-hole axe head with bird-headed demon, boar, and dragon.Bronze Age, ca. late 3rd–early 2nd millennium B.C.,Bactria-Margiana metmuseum.org

Shaft-hole axe head with bird-headed demon, boar, and dragon.Bronze Age, ca. late 3rd–early 2nd millennium B.C.,Bactria-Margiana metmuseum.orgSee: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/09/central-asian-seals-seal-impressions.html

The pattern of double-heading in artistic representation and duplication of signs or glyphs (e.g. two bulls facing each other) in an inscription have been explained in decoded Indus script as connoting dula 'pair'; rebus: dul 'casting (metal)'. If the eagle is read rebus using a lexems of Indian linguistic area to connote pajhar 'eagle' (rebus: pasra 'smithy'), the double-headed eagle can be read as: dul pajhar = metal casting smithy. The body of a person ligatured to the double-headed eagle can denote the smith whose metalworking trade is related to casting of metals.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/09/central-asian-seals-seal-impressions.html

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/tvastr-is-is-taksa-engrave-cire-perdue.html

Gold sheet and silver, Late 3rd/early 2nd millennium B.C.E.

L. 12.68 cm. Ceremonial Axe Baktria,Northern Afghanistan http://www.lessingimages.com/search.asp?a=L&lc=202020207EE6&ln=Collection+George+Ortiz%2C+Geneva%2C+Switzerland&p=1 "The whole cast by the lost wax process. The boar covered with a sheet of gold annealed and hammered on, some 3/10-6/10 mm in thickness, almost all the joins covered up with silver. At the base of the mane between the shoulders an oval motif with irregular indents. The lion and the boar hammered, elaborately chased and polished. A shaft opening - 22 holes around its edge laced with gold wire some 7/10-8/10 mm in diameter - centred under the lion's shoulder; between these a hole (diam: some 6.5 mm) front and back for insertion of a dowel to hold the shaft in place, both now missing.Condition: a flattening blow to the boar's backside where the tail curled out and another to the hair between the front of his ears, his spine worn with traces of slight hatching still visible, a slight flattening and wear to his left tusk and lower left hind leg. A flattening and wear to the left side of the lion's face, ear, cheek, eye, nose and jaw and a flattening blow to the whole right forepaw and paw. Nicks to the lion's tail. The surface with traces of silver chloride under the lion's stomach and around the shaft opening." https://www.flickr.com/photos/antiquitiesproject/4616778973

Cast axe-head; tin bronze inlaid with silver; shows a boar attacking a tiger which is attacking an ibex.ca. 2500 -2000 BCE Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. Length: 17.8 cm (7 in). Weight: 675.5 g (23.82 oz). British Museum.ME 123268 (1913,0314.11913,0314.1) R. Maxwell-Hyslop, 'British Museum “axe” no. 123628: a Bactrian bronze', Bulletin of the Asia Institute, NS I (1987), pp. 17-26

Curator's comments: See RL file 6616 (29/6/1995); also Research Lab file 4992 of 12/09/1983 where XRF analysis of surface indicates composition as tin bronze with approx 10% tin and traces of arsenic, nickel, silver and lead. Dalton's inclusion in the 'Catalogue of the Oxus Treasure' among a small group of comparative items has unfortunately led to recurrent confusion over the date and provenance of this piece. It was first believed to be Achaemenid in date (Dalton, 'Catalogue of the Oxus Treasure', p. 48), labelled as such in 1975 in the former Iranian Room and thus suggested to be an Achaemenid scabbard chape (P R S Moorey CORRES 1975, based on an example said to have been excavated by P. Bernard at Ai Khanoum or seen by him in Kabul Bazaar, cf. P. Bernard CORRES 1976). It has also been assigned a 4th-5th century AD Sasanian date (P. Amiet, 1967, in 'Revue du Louvre' 17, pp. 281-82). However, its considerably earlier - late 3rd mill. BC Bronze Age - date has now been clearly demonstrated following the discovery of large numbers of objects of related form in south-east Iran and Bactria, and it has since been recognised and/or cited as such, for instance by H. Pittmann (hence archaeometallurgical analysis in 1983; R. Maxwell-Hyslop, 1988a, "British Museum axe no. 123628: a Bactrian bronze", 'Bulletin of the Asia Institute' 1 (NS), pp. 17-26; F. Hiebert & C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky 1992a, "Central Asia and the Indo-Iranian Borderlands",' Iran' 30, p. 5; B. Brentjes, 1991a, "Ein tierkampfszene in bronze", 'Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran' 24 (NS), p. 1, taf. 1).

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=367862&partId=1

Eagle incised on a ceremonial axe made of chlorite. Tepe Yahya. (After Fig. 9.6 in Philip H. Kohl, 2001, opcit.)

Zoom: Sarasvati depicted on the upper lip (snout) of Varaha.

Site Name: Khajuraho

Site Name: KhajurahoMonument: Varaha Mandir

Subject of Photo: Varaha

Locator Info. of Photo: SE of Laksmana temple courtyard

Photo Orientation: overview from SW looking NE

Iconography: Varaha

Dynasty/Period: Candella

Date: ca. latter half of the tenth century CE, 950 CE - 1000 CE

Material: stone

Architecture: structural

Zoom into Sarasvati image on the upper lip (snout) of Varaha

Along with various divinities, shown on the body of Viṣṇu's Varāhāvatara, third among incarnations, Sarasvatī figures appropriately on the mouth of Varāha Boar's monolithic image at Khajurāho (10th cent.)

Contemplating on pan-Indian tendencies of making images of Sarasvatī in the Hindu, Buddhist and Jaina pantheons, Catherine Ludvik, with her extensive researches on the theme[*], suggests two possibilities of Sarasvatī's feminine form : 1. the Mahābhārata narrative details, 2. Or, the other way around 'the female figure of Sarasvatī in the epic (Mahābhārata) might conceivably have been inspired from already existing, but no longer extant or known to be extant, representations of her' [Ludvik 107]. Thus the origin of Sarasvatī's iconographic conceptualization goes back to the third century bce. From then on gradually her human-like representations developed in the three different religions of the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain.

Vedābnāṁ mātaraṁ paśya matsthāṁ.

'Behold goddess Sarasvatī, the mother of Vedas enshrined in me' says Nārāyaṇa to Nārada [Vyasa's Mahābhārata, 12 : 326 : 5.]

Sarasvatīha vāgbhūtā śarīram te pravekṣyati

Sarasvatī enters the body as speech - [supra 12 : 306 : 6.]

jihvāyām vāk Sarasvatī

Sarasvatī dwells in the tongue [- ibid 12 : 231 : 8.].

devī jihvā sarasvatī

'goddess Sarasvatī is (your) tongue' says Bhīṣma, in veneration of Viṣṇu - [supra 6 : 61 : 56.].

parama jinendra-vāṇiye Sarasvatī

the supreme Lord Jina's preaching is Sarasvatī - [Pampa, Ādipurāṇa, 1-16.].

The Mahābhārata has referred to Sarasvatī as vāc [12 : 306 : 6] and vaṇī [3 : 132 : 2].

Besides, her beautiful form and lovely celestial body is lauded [3 : 184 : 18].

rūpaṁ ca te divyam atyanta kāntam

http://www.herenow4u.net/index.php?id=68838

Srimad Bhagavatam Canto 3 Chapter 18

Canto 3: The Status Quo Chapter 18: The Battle Between Lord Boar and the Demon Hiranyaksha

Bhaktivedanta VedaBase: Srimad Bhagavatam

SB 3.18.1: Maitreya continued: The proud and falsely glorious Daitya paid little heed to the words of Varuna. O dear Vidura, he learned from Narada the whereabouts of the Supreme Personality of Godhead and hurriedly betook himself to the depths of the ocean.

SB 3.18.2: He saw there the all-powerful Personality of Godhead in His boar incarnation, bearing the earth upward on the ends of His tusks and robbing him of his splendor with His reddish eyes. The demon laughed: Oh, an amphibious beast!

SB 3.18.3: The demon addressed the Lord: O best of the demigods, dressed in the form of a boar, just hear me. This earth is entrusted to us, the inhabitants of the lower regions, and You cannot take it from my presence and not be hurt by me.

SB 3.18.4: You rascal, You have been nourished by our enemies to kill us, and You have killed some demons by remaining invisible. O fool, Your power is only mystic, so today I shall enliven my kinsmen by killing You.

SB 3.18.5: The demon continued: When You fall dead with Your skull smashed by the mace hurled by my arms, the demigods and sages who offer You oblations and sacrifice in devotional service will also automatically cease to exist, like trees without roots.

SB 3.18.6: Although the Lord was pained by the shaftlike abusive words of the demon, He bore the pain. But seeing that the earth on the ends of His tusks was frightened, He rose out of the water just as an elephant emerges with its female companion when assailed by an alligator.

SB 3.18.7: The demon, who had golden hair on his head and fearful tusks, gave chase to the Lord while He was rising from the water, even as an alligator would chase an elephant. Roaring like thunder, he said: Are You not ashamed of running away before a challenging adversary? There is nothing reproachable for shameless creatures!

SB 3.18.8: The Lord placed the earth within His sight on the surface of the water and transferred to her His own energy in the form of the ability to float on the water. While the enemy stood looking on, Brahma, the creator of the universe, extolled the Lord, and the other demigods rained flowers on Him.

SB 3.18.9: The demon, who had a wealth of ornaments, bangles and beautiful golden armor on his body, chased the Lord from behind with a great mace. The Lord tolerated his piercing ill words, but in order to reply to him, He expressed His terrible anger.

SB 3.18.10: The Personality of Godhead said: Indeed, We are creatures of the jungle, and We are searching after hunting dogs like you. One who is freed from the entanglement of death has no fear from the loose talk in which you are indulging, for you are bound up by the laws of death.

SB 3.18.11: Certainly We have stolen the charge of the inhabitants of Rasatala and have lost all shame. Although bitten by your powerful mace, I shall stay here in the water for some time because, having created enmity with a powerful enemy, I now have no place to go.

SB 3.18.12: You are supposed to be the commander of many foot soldiers, and now you may take prompt steps to overthrow Us. Give up all your foolish talk and wipe out the cares of your kith and kin by slaying Us. One may be proud, yet he does not deserve a seat in an assembly if he fails to fulfill his promised word.

SB 3.18.13: Sri Maitreya said: The demon, being thus challenged by the Personality of Godhead, became angry and agitated, and he trembled in anger like a challenged cobra.

SB 3.18.14: Hissing indignantly, all his senses shaken by wrath, the demon quickly sprang upon the Lord and dealt Him a blow with his powerful mace.

SB 3.18.15: The Lord, however, by moving slightly aside, dodged the violent mace-blow aimed at His breast by the enemy, just as an accomplished yogi would elude death.

SB 3.18.16: The Personality of Godhead now exhibited His anger and rushed to meet the demon, who bit his lip in rage, took up his mace again and began to repeatedly brandish it about.

SB 3.18.17: Then with His mace the Lord struck the enemy on the right of his brow, but since the demon was expert in fighting, O gentle Vidura, he protected himself by a maneuver of his own mace.

SB 3.18.18: In this way, the demon Haryaksha and the Lord, the Personality of Godhead, struck each other with their huge maces, each enraged and seeking his own victory.

SB 3.18.19: There was keen rivalry between the two combatants; both had sustained injuries on their bodies from the blows of each other's pointed maces, and each grew more and more enraged at the smell of blood on his person. In their eagerness to win, they performed maneuvers of various kinds, and their contest looked like an encounter between two forceful bulls for the sake of a cow.

SB 3.18.20: O descendant of Kuru, Brahma, the most independent demigod of the universe, accompanied by his followers, came to see the terrible fight for the sake of the world between the demon and the Personality of Godhead, who appeared in the form of a boar.

SB 3.18.21: After arriving at the place of combat, Brahma, the leader of thousands of sages and transcendentalists, saw the demon, who had attained such unprecedented power that no one could fight with him. Brahma then addressed Narayana, who was assuming the form of a boar for the first time.

SB 3.18.22-23: Lord Brahma said: My dear Lord, this demon has proved to be a constant pinprick to the demigods, the brahmanas, the cows and innocent persons who are spotless and always dependent upon worshiping Your lotus feet. He has become a source of fear by unnecessarily harassing them. Since he has attained a boon from me, he has become a demon, always searching for a proper combatant, wandering all over the universe for this infamous purpose.

SB 3.18.24: Lord Brahma continued: My dear Lord, there is no need to play with this serpentine demon, who is always very skilled in conjuring tricks and is arrogant, self-sufficient and most wicked.

SB 3.18.25: Brahma continued: My dear Lord, You are infallible. Please kill this sinful demon before the demoniac hour arrives and he presents another formidable approach favorable to him. You can kill him by Your internal potency without doubt.

SB 3.18.26: My Lord, the darkest evening, which covers the world, is fast approaching. Since You are the Soul of all souls, kindly kill him and win victory for the demigods.

SB 3.18.27: The auspicious period known as abhijit, which is most opportune for victory, commenced at midday and has all but passed; therefore, in the interest of Your friends, please dispose of this formidable foe quickly.

SB 3.18.28: This demon, luckily for us, has come of his own accord to You, his death ordained by You; therefore, exhibiting Your ways, kill him in the duel and establish the worlds in peace.

Varaha, rock carving from the early 5th century, in Udayagiri, Orissa, India. (Encyclopaedia Britannica).

Canto 3: The Status Quo Chapter 18: The Battle Between Lord Boar and the Demon Hiranyaksha

Bhaktivedanta VedaBase: Srimad Bhagavatam

SB 3.18.1: Maitreya continued: The proud and falsely glorious Daitya paid little heed to the words of Varuna. O dear Vidura, he learned from Narada the whereabouts of the Supreme Personality of Godhead and hurriedly betook himself to the depths of the ocean.

SB 3.18.2: He saw there the all-powerful Personality of Godhead in His boar incarnation, bearing the earth upward on the ends of His tusks and robbing him of his splendor with His reddish eyes. The demon laughed: Oh, an amphibious beast!

SB 3.18.3: The demon addressed the Lord: O best of the demigods, dressed in the form of a boar, just hear me. This earth is entrusted to us, the inhabitants of the lower regions, and You cannot take it from my presence and not be hurt by me.

SB 3.18.4: You rascal, You have been nourished by our enemies to kill us, and You have killed some demons by remaining invisible. O fool, Your power is only mystic, so today I shall enliven my kinsmen by killing You.

SB 3.18.5: The demon continued: When You fall dead with Your skull smashed by the mace hurled by my arms, the demigods and sages who offer You oblations and sacrifice in devotional service will also automatically cease to exist, like trees without roots.

SB 3.18.6: Although the Lord was pained by the shaftlike abusive words of the demon, He bore the pain. But seeing that the earth on the ends of His tusks was frightened, He rose out of the water just as an elephant emerges with its female companion when assailed by an alligator.

SB 3.18.7: The demon, who had golden hair on his head and fearful tusks, gave chase to the Lord while He was rising from the water, even as an alligator would chase an elephant. Roaring like thunder, he said: Are You not ashamed of running away before a challenging adversary? There is nothing reproachable for shameless creatures!

SB 3.18.8: The Lord placed the earth within His sight on the surface of the water and transferred to her His own energy in the form of the ability to float on the water. While the enemy stood looking on, Brahma, the creator of the universe, extolled the Lord, and the other demigods rained flowers on Him.

SB 3.18.9: The demon, who had a wealth of ornaments, bangles and beautiful golden armor on his body, chased the Lord from behind with a great mace. The Lord tolerated his piercing ill words, but in order to reply to him, He expressed His terrible anger.

SB 3.18.10: The Personality of Godhead said: Indeed, We are creatures of the jungle, and We are searching after hunting dogs like you. One who is freed from the entanglement of death has no fear from the loose talk in which you are indulging, for you are bound up by the laws of death.

SB 3.18.11: Certainly We have stolen the charge of the inhabitants of Rasatala and have lost all shame. Although bitten by your powerful mace, I shall stay here in the water for some time because, having created enmity with a powerful enemy, I now have no place to go.

SB 3.18.12: You are supposed to be the commander of many foot soldiers, and now you may take prompt steps to overthrow Us. Give up all your foolish talk and wipe out the cares of your kith and kin by slaying Us. One may be proud, yet he does not deserve a seat in an assembly if he fails to fulfill his promised word.

SB 3.18.13: Sri Maitreya said: The demon, being thus challenged by the Personality of Godhead, became angry and agitated, and he trembled in anger like a challenged cobra.

SB 3.18.14: Hissing indignantly, all his senses shaken by wrath, the demon quickly sprang upon the Lord and dealt Him a blow with his powerful mace.

SB 3.18.15: The Lord, however, by moving slightly aside, dodged the violent mace-blow aimed at His breast by the enemy, just as an accomplished yogi would elude death.

SB 3.18.16: The Personality of Godhead now exhibited His anger and rushed to meet the demon, who bit his lip in rage, took up his mace again and began to repeatedly brandish it about.

SB 3.18.17: Then with His mace the Lord struck the enemy on the right of his brow, but since the demon was expert in fighting, O gentle Vidura, he protected himself by a maneuver of his own mace.

SB 3.18.18: In this way, the demon Haryaksha and the Lord, the Personality of Godhead, struck each other with their huge maces, each enraged and seeking his own victory.

SB 3.18.19: There was keen rivalry between the two combatants; both had sustained injuries on their bodies from the blows of each other's pointed maces, and each grew more and more enraged at the smell of blood on his person. In their eagerness to win, they performed maneuvers of various kinds, and their contest looked like an encounter between two forceful bulls for the sake of a cow.

SB 3.18.20: O descendant of Kuru, Brahma, the most independent demigod of the universe, accompanied by his followers, came to see the terrible fight for the sake of the world between the demon and the Personality of Godhead, who appeared in the form of a boar.

SB 3.18.21: After arriving at the place of combat, Brahma, the leader of thousands of sages and transcendentalists, saw the demon, who had attained such unprecedented power that no one could fight with him. Brahma then addressed Narayana, who was assuming the form of a boar for the first time.

SB 3.18.22-23: Lord Brahma said: My dear Lord, this demon has proved to be a constant pinprick to the demigods, the brahmanas, the cows and innocent persons who are spotless and always dependent upon worshiping Your lotus feet. He has become a source of fear by unnecessarily harassing them. Since he has attained a boon from me, he has become a demon, always searching for a proper combatant, wandering all over the universe for this infamous purpose.

SB 3.18.24: Lord Brahma continued: My dear Lord, there is no need to play with this serpentine demon, who is always very skilled in conjuring tricks and is arrogant, self-sufficient and most wicked.

SB 3.18.25: Brahma continued: My dear Lord, You are infallible. Please kill this sinful demon before the demoniac hour arrives and he presents another formidable approach favorable to him. You can kill him by Your internal potency without doubt.

SB 3.18.26: My Lord, the darkest evening, which covers the world, is fast approaching. Since You are the Soul of all souls, kindly kill him and win victory for the demigods.

SB 3.18.27: The auspicious period known as abhijit, which is most opportune for victory, commenced at midday and has all but passed; therefore, in the interest of Your friends, please dispose of this formidable foe quickly.

SB 3.18.28: This demon, luckily for us, has come of his own accord to You, his death ordained by You; therefore, exhibiting Your ways, kill him in the duel and establish the worlds in peace.

Varaha, rock carving from the early 5th century, in Udayagiri, Orissa, India. (Encyclopaedia Britannica).

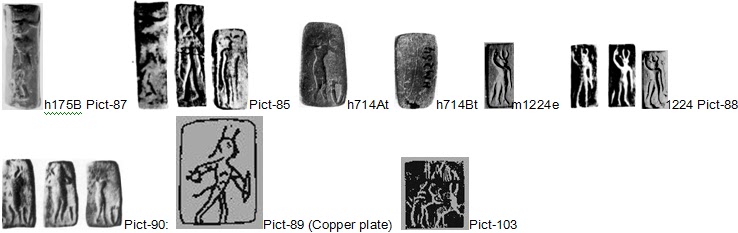

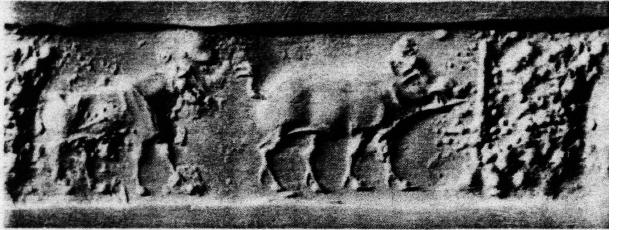

On the Rakhigarhi seal, a fine distinction is made between two orthographic options for signifying an arrow with fine pronunciation variants, to distinguish between an arrowhead and an arrow: kaNDa, kANDa. The word kANDa is used by Panini in an expression ayaskANDa to denote a quantity of iron, excellent iron (Pāṇ.gaṇ) i.e., metal (iron/copper alloy). This expression ayas+ kāṇḍa अयस्--काण्ड is signified by hieroglyphs: aya 'fish' PLUS kāṇḍa, 'arrow' as shown on Kalibangan Seal 032. An allograph for this hieroglyph 'arrowhead' is gaNDa 'four' (short strokes) as seen on Mohenjo-daro seal M1118.

Rebus: ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.)

Thus, the arrowhead is signified by the hieroglyph which distinguishes the arrowhead as a triangle attached to a reedpost or handle of tool/weapon.

As distinct from this orthographic representation of 'arrowhead' with a triangle PLUS attached linear stroke, an arrow is signified by an angle ^ (Caret; Circumflex accent; Up arrow) with a linear stroke ligatured, as in the Rakhigarhi seal. To reinforce the distinction between 'arrow' and 'arrowhead' in Indus Script orthography, a notch is added atop the tip of the circumflex accent. Both the hieroglyph-components are attested in Indian sprachbund with a variant pronunciation: khANDA. खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon) (Marathi)

It is thus clear that the morpheme kANDa denotes an arrowhead, while the ^ circumflex accent hieroglyph is intended to signify rebus: kāṇḍā 'edge of tool or weapon' or a sharp edged implement, like a sword. In Indian sprachbund, the word which denotes a sword is khaṁḍa -- m. ʻswordʼ(Prakritam).

In the hieroglyph-multiplex of Rakhigarhi seal inscription, the left and right parentheses are used as circumscript to provide phonetic determination of the gloss: khaṁḍa -- m. ʻswordʼ (Prakritam), while the ligaturing element of 'notch' is intended to signify खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] 'A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon)' Rebus: kaNDa 'implements' (Santali). Thus, the hieroglyph-multiplex is read rebus as kaNDa 'implements' PLUS khaṁḍa ʻswordʼ. The supercargo is thus catalogued on the seal as: 1. arrowheads; 2. metal implements and ingots; 3. swords.

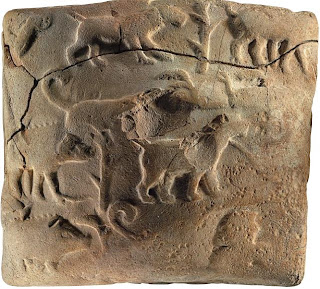

The hieroglyph 'rhinoceros is: kANDA rebus: kaNDa 'implements/weapons'.The entire inscription or metalwork catalogue message on Rakhigarhi seal can be deciphered:kaNDa 'implements/weapons' (Rhinoceros) PLUS खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] 'weapons' PLUS mūhā 'cast ingots'(Left and Right parentheses as split rhombus or ellipse).

Thus, the supercargo consignment documented by this metalwork catalogue on Rakhigarhi seal is: metal (alloy) swords, metal (alloy) implements, metal cast ingots.

M1118

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/supercaro-ingots-1-of-cast-metal-2-for.html

This monograph deciphers m1429 Prism tablet with Indus inscriptions on 3 sides. Three Sided Moulded Tablet with a boat and crocodile+fish Indus inscription Fired clay L.4.6 cm W. 1.2 cm Indus valley, Mohenjo-daro,MD 602, Harappan,ca 2600 -1900 BCE Islamabad Museum, Islamabad NMP 1384, Pakistan.![Image result for mohenjodaro boat seal]() One side of a Mohenjo-daro tablet.

One side of a Mohenjo-daro tablet.

What was the cargo carried on the boat? I suggest that the cargo was Meluhha metalwork.

The shape of the pair of ingots on the boat (shown on the tablet) is comparable to following figures: 1. the ingot on which stands the Ingot-god (Enkomi); 2. Copper ingot from Zakros, Crete, displayed at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum But the script used on the tablet is NOT Cypro-Minoan or Cretan or Minoan but Meluhha:

![]() The shape of the pair of ingots on the boat (shown on the tablet) is comparable to following figures: 1. the ingot on which stands the Ingot-god (Enkomi); 2. Copper ingot from Zakros, Crete, displayed at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum But the script used on the tablet is NOT Cypro-Minoan or Cretan or Minoan but Meluhha: One side of a Mohenjo-daro prism tablet (Full decipherment of the three sided inscription is embedded). What was the cargo carried on the boat? I suggest that the cargo was Meluhha metalwork -- castings and hard copper alloy ingots. Together with the pair of aquatic birds, the metalwork is with hard alloys (of copper).

The shape of the pair of ingots on the boat (shown on the tablet) is comparable to following figures: 1. the ingot on which stands the Ingot-god (Enkomi); 2. Copper ingot from Zakros, Crete, displayed at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum But the script used on the tablet is NOT Cypro-Minoan or Cretan or Minoan but Meluhha: One side of a Mohenjo-daro prism tablet (Full decipherment of the three sided inscription is embedded). What was the cargo carried on the boat? I suggest that the cargo was Meluhha metalwork -- castings and hard copper alloy ingots. Together with the pair of aquatic birds, the metalwork is with hard alloys (of copper).

bagalo = an Arabian merchant vessel (Gujarati) bagala = an Arab boat of a particular description (Ka.); bagalā (M.); bagarige, bagarage = a kind of vessel (Kannada) Rebus: bangala = kumpaṭi = angāra śakaṭī = a chafing dish a portable stove a goldsmith’s portable furnace (Telugu) cf. bangaru bangaramu = gold (Telugu)![]() karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

Side A: kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Telugu) ghariyal id. (Hindi)kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) கராம் karām, n. prob. grāha. 1. A species of alligator; முதலைவகை. முதலையு மிடங்கருங் கராமும் (குறிஞ்சிப். 257). 2. Male alligator; ஆண் முதலை. (திவா.) కారుమొసలి a wild crocodile or alligator. (Telugu) Rebus: kāru ‘artisan’ (Marathi) kāruvu 'artisan' (Telugu) khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)[fish = aya (G.); crocodile = kāru (Telugu)] Rebus: ayakāra ‘ironsmith’ (Pali)

khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन्, which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.)

![]() Text 3246 (l., to r.)

Text 3246 (l., to r.)

![]()

![]() mēd ‘body’ (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercaro'

mēd ‘body’ (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercaro'

![]() dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' Thus the the pair of ellipses with an inscripted 'notch' hieroglyph component: dul mūhā 'cast ingot.

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' Thus the the pair of ellipses with an inscripted 'notch' hieroglyph component: dul mūhā 'cast ingot.

![]() karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo'kárṇa— m. ‘ear, handle of a vessel’ RV., ‘end, tip (?)’ RV. ii 34, 3. [Cf. *kāra—6] Pa. kaṇṇa— m. ‘ear, angle, tip’; Pk. kaṇṇa—, °aḍaya- m. ‘ear’, Gy. as. pal. eur. kan m., Ash. (Trumpp) karna NTS ii 261, Niṅg. kõmacr;, Woṭ. kanƏ, Tir. kana; Paš. kan, kaṇ(ḍ)— ‘orifice of ear’ IIFL iii 3, 93; Shum. kõmacr;ṛ ‘ear’, Woṭ. kan m., Kal. (LSI) kuṛõmacr;, rumb. kuŕũ, urt. kŕä̃ (< *kaṇ), Bshk. kan, Tor. k *l ṇ, Kand. kōṇi, Mai. kaṇa, ky. kān, Phal. kāṇ, Sh. gil. ko̯n pl. ko̯ṇí m. (→ Ḍ kon pl. k *l ṇa), koh. kuṇ, pales. kuāṇƏ, K. kan m., kash. pog. ḍoḍ. kann, S. kanu m., L. kann m., awāṇ. khet. kan, P. WPah. bhad. bhal. cam. kann m., Ku. gng. N. kān; A. kāṇ ‘ear, rim of vessel, edge of river’; B. kāṇ ‘ear’, Or. kāna, Mth. Bhoj. Aw. lakh. H. kān m., OMarw. kāna m., G. M. kān m., Ko. kānu m., Si. kaṇa, kana. — As adverb and postposition (ápi kárṇē ‘from behind’ RV., karṇē ‘aside’ Kālid.): Pa. kaṇṇē ‘at one's ear, in a whisper’; Wg. ken ‘to’ NTS ii 279; Tir. kõ; ‘on’ AO xii 181 with (?); Paš. kan ‘to’; K. kȧni with abl. ‘at, near, through’, kani with abl. or dat. ‘on’, kun with dat. ‘toward’; S. kani ‘near’, kanā̃ ‘from’; L. kan ‘toward’, kannũ ‘from’, kanne ‘with’, khet. kan, P. ḍog. kanē ‘with, near’; WPah. bhal. k *l ṇ, °ṇi, k e ṇ, °ṇi with obl. ‘with, near’, kiṇ, °ṇiā̃, k *l ṇiā̃, k e ṇ° with obl. ‘from’; Ku. kan ‘to, for’; N. kana ‘for, to, with’; H. kane, °ni, kan with ke ‘near’; OMarw. kanai ‘near’, kanā̃ sā ‘from near’, kā̃nı̄̃ ‘towards’; G. kan e ‘beside’. Addenda: kárṇa—: S.kcch. kann m. ‘ear’, WPah.kṭg. (kc.) kān, poet. kanṛu m. ‘ear’, kṭg. kanni f. ‘pounding—hole in barn floor’; J. kā'n m. ‘ear’, Garh. kān; Md. kan— in kan—fat ‘ear’ (CDIAL 2830)

karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo'kárṇa— m. ‘ear, handle of a vessel’ RV., ‘end, tip (?)’ RV. ii 34, 3. [Cf. *kāra—6] Pa. kaṇṇa— m. ‘ear, angle, tip’; Pk. kaṇṇa—, °aḍaya- m. ‘ear’, Gy. as. pal. eur. kan m., Ash. (Trumpp) karna NTS ii 261, Niṅg. kõmacr;, Woṭ. kanƏ, Tir. kana; Paš. kan, kaṇ(ḍ)— ‘orifice of ear’ IIFL iii 3, 93; Shum. kõmacr;ṛ ‘ear’, Woṭ. kan m., Kal. (LSI) kuṛõmacr;, rumb. kuŕũ, urt. kŕä̃ (< *kaṇ), Bshk. kan, Tor. k *l ṇ, Kand. kōṇi, Mai. kaṇa, ky. kān, Phal. kāṇ, Sh. gil. ko̯n pl. ko̯ṇí m. (→ Ḍ kon pl. k *l ṇa), koh. kuṇ, pales. kuāṇƏ, K. kan m., kash. pog. ḍoḍ. kann, S. kanu m., L. kann m., awāṇ. khet. kan, P. WPah. bhad. bhal. cam. kann m., Ku. gng. N. kān; A. kāṇ ‘ear, rim of vessel, edge of river’; B. kāṇ ‘ear’, Or. kāna, Mth. Bhoj. Aw. lakh. H. kān m., OMarw. kāna m., G. M. kān m., Ko. kānu m., Si. kaṇa, kana. — As adverb and postposition (ápi kárṇē ‘from behind’ RV., karṇē ‘aside’ Kālid.): Pa. kaṇṇē ‘at one's ear, in a whisper’; Wg. ken ‘to’ NTS ii 279; Tir. kõ; ‘on’ AO xii 181 with (?); Paš. kan ‘to’; K. kȧni with abl. ‘at, near, through’, kani with abl. or dat. ‘on’, kun with dat. ‘toward’; S. kani ‘near’, kanā̃ ‘from’; L. kan ‘toward’, kannũ ‘from’, kanne ‘with’, khet. kan, P. ḍog. kanē ‘with, near’; WPah. bhal. k *l ṇ, °ṇi, k e ṇ, °ṇi with obl. ‘with, near’, kiṇ, °ṇiā̃, k *l ṇiā̃, k e ṇ° with obl. ‘from’; Ku. kan ‘to, for’; N. kana ‘for, to, with’; H. kane, °ni, kan with ke ‘near’; OMarw. kanai ‘near’, kanā̃ sā ‘from near’, kā̃nı̄̃ ‘towards’; G. kan e ‘beside’. Addenda: kárṇa—: S.kcch. kann m. ‘ear’, WPah.kṭg. (kc.) kān, poet. kanṛu m. ‘ear’, kṭg. kanni f. ‘pounding—hole in barn floor’; J. kā'n m. ‘ear’, Garh. kān; Md. kan— in kan—fat ‘ear’ (CDIAL 2830)

![]() aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

![]() kolom 'thre' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'

kolom 'thre' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'

![]() kolami mūhā 'ingot (for)smithy,forge ingot'

kolami mūhā 'ingot (for)smithy,forge ingot'

Thus, the message of the text on the Mohenjo-daro prism tablet of a boat + crocodile + fish is: supercargo of kolami mūhā 'smithy,forge ingots' dul mūhā 'cast metal ingots'. The metal is sinified as ayas.

mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends (Santali)Maysar c.2200 BCE Packed copper ingots. The shape of the ingots is an 'equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends' -- like an ellipse or rhombus. See:

See: http://nautarch.tamu.edu/pdf-files/JonesM-MA2007.pdf Michael Rice Jones' thesis of 2007 on the importance of Maysar for copper production.

An ingot may be signified by an ellipse or parenthesis of a rhombus. It may also be signified by an allograph: human face.

Hieroglyph: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; kolhe tehen me~ṛhe~t mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron(Santali) Rebus: mūhā 'ingot'; Compound formation: mleccha-mukha (Skt.) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali)

![]() Santali glossesWilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:

Santali glossesWilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:

Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

A lexicon suggests the semantics of Panini's compound अयस्--काण्ड [p= 85,1] m. n. " a quantity of iron " or " excellent iron " , (g. कस्का*दि q.v.)( Pa1n2. 8-3 , 48)(Monier-Williams).

From the example of a compound gloss in Santali, I suggest that the suffix -kANDa in Samskritam should have referred to 'implements'. Indus Script hieroglyphs as hypertext components to signify kANDa 'implements' are: kANTa, 'overflowing water' kANDa, 'arrow' gaNDa, 'four short circumscript strokes''rhonoceros'.

On the Rakhigarhi seal, a fine distinction is made between two orthographic options for signifying an arrow with fine pronunciation variants, to distinguish between an arrowhead and an arrow: kaNDa, kANDa. The word kANDa is used by Panini in an expression ayaskANDa to denote a quantity of iron, excellent iron (Pāṇ.gaṇ) i.e., metal (iron/copper alloy). This expression ayas+ kāṇḍa अयस्--काण्ड is signified by hieroglyphs: aya 'fish' PLUS kāṇḍa, 'arrow' as shown on Kalibangan Seal 032. An allograph for this hieroglyph 'arrowhead' is gaNDa 'four' (short strokes) as seen on Mohenjo-daro seal M1118.

Rebus: ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.)

Thus, the arrowhead is signified by the hieroglyph which distinguishes the arrowhead as a triangle attached to a reedpost or handle of tool/weapon.

As distinct from this orthographic representation of 'arrowhead' with a triangle PLUS attached linear stroke, an arrow is signified by an angle ^ (Caret; Circumflex accent; Up arrow) with a linear stroke ligatured, as in the Rakhigarhi seal. To reinforce the distinction between 'arrow' and 'arrowhead' in Indus Script orthography, a notch is added atop the tip of the circumflex accent. Both the hieroglyph-components are attested in Indian sprachbund with a variant pronunciation: khANDA. खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon) (Marathi)

It is thus clear that the morpheme kANDa denotes an arrowhead, while the ^ circumflex accent hieroglyph is intended to signify rebus: kāṇḍā 'edge of tool or weapon' or a sharp edged implement, like a sword. In Indian sprachbund, the word which denotes a sword is khaṁḍa -- m. ʻswordʼ(Prakritam).

In the hieroglyph-multiplex of Rakhigarhi seal inscription, the left and right parentheses are used as circumscript to provide phonetic determination of the gloss: khaṁḍa -- m. ʻswordʼ (Prakritam), while the ligaturing element of 'notch' is intended to signify खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] 'A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon)' Rebus: kaNDa 'implements' (Santali).

Thus, the hieroglyph-multiplex is read rebus as kaNDa 'implements' PLUS khaṁḍa ʻswordʼ. The supercargo is thus catalogued on the seal as: 1. arrowheads; 2. metal implements and ingots; 3. swords.

The hieroglyph 'rhinoceros is: kANDA rebus: kaNDa 'implements/weapons'.

The entire inscription or metalwork catalogue message on Rakhigarhi seal can be deciphered:

kaNDa 'implements/weapons' (Rhinoceros) PLUS खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] 'weapons' PLUS mūhā 'cast ingots'(Left and Right parentheses as split rhombus or ellipse).

Thus, the supercargo consignment documented by this metalwork catalogue on Rakhigarhi seal is: metal (alloy) swords, metal (alloy) implements, metal cast ingots.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/supercaro-ingots-1-of-cast-metal-2-for.html

This monograph deciphers m1429 Prism tablet with Indus inscriptions on 3 sides. Three Sided Moulded Tablet with a boat and crocodile+fish Indus inscription Fired clay L.4.6 cm W. 1.2 cm Indus valley, Mohenjo-daro,MD 602, Harappan,ca 2600 -1900 BCE Islamabad Museum, Islamabad NMP 1384, Pakistan.

What was the cargo carried on the boat? I suggest that the cargo was Meluhha metalwork.

The shape of the pair of ingots on the boat (shown on the tablet) is comparable to following figures: 1. the ingot on which stands the Ingot-god (Enkomi); 2. Copper ingot from Zakros, Crete, displayed at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum But the script used on the tablet is NOT Cypro-Minoan or Cretan or Minoan but Meluhha:

The shape of the pair of ingots on the boat (shown on the tablet) is comparable to following figures: 1. the ingot on which stands the Ingot-god (Enkomi); 2. Copper ingot from Zakros, Crete, displayed at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum But the script used on the tablet is NOT Cypro-Minoan or Cretan or Minoan but Meluhha: One side of a Mohenjo-daro prism tablet (Full decipherment of the three sided inscription is embedded). What was the cargo carried on the boat? I suggest that the cargo was Meluhha metalwork -- castings and hard copper alloy ingots. Together with the pair of aquatic birds, the metalwork is with hard alloys (of copper).

bagalo = an Arabian merchant vessel (Gujarati) bagala = an Arab boat of a particular description (Ka.); bagalā (M.); bagarige, bagarage = a kind of vessel (Kannada) Rebus: bangala = kumpaṭi = angāra śakaṭī = a chafing dish a portable stove a goldsmith’s portable furnace (Telugu) cf. bangaru bangaramu = gold (Telugu)![]()

karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

Side A: kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Telugu) ghariyal id. (Hindi)

kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) கராம் karām, n. prob. grāha. 1. A species of alligator; முதலைவகை. முதலையு மிடங்கருங் கராமும் (குறிஞ்சிப். 257). 2. Male alligator; ஆண் முதலை. (திவா.) కారుమొసలి a wild crocodile or alligator. (Telugu) Rebus: kāru ‘artisan’ (Marathi) kāruvu 'artisan' (Telugu) khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

[fish = aya (G.); crocodile = kāru (Telugu)] Rebus: ayakāra ‘ironsmith’ (Pali)

khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन्, which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.)

Text 3246 (l., to r.)

Text 3246 (l., to r.)

mēd ‘body’ (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercaro'

mēd ‘body’ (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercaro' dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' Thus the the pair of ellipses with an inscripted 'notch' hieroglyph component: dul mūhā 'cast ingot.

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' Thus the the pair of ellipses with an inscripted 'notch' hieroglyph component: dul mūhā 'cast ingot.  karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo'

karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo'kárṇa— m. ‘ear, handle of a vessel’ RV., ‘end, tip (?)’ RV. ii 34, 3. [Cf. *kāra—6] Pa. kaṇṇa— m. ‘ear, angle, tip’; Pk. kaṇṇa—, °aḍaya- m. ‘ear’, Gy. as. pal. eur. kan m., Ash. (Trumpp) karna NTS ii 261, Niṅg. kõmacr;, Woṭ. kanƏ, Tir. kana; Paš. kan, kaṇ(ḍ)— ‘orifice of ear’ IIFL iii 3, 93; Shum. kõmacr;ṛ ‘ear’, Woṭ. kan m., Kal. (LSI) kuṛõmacr;, rumb. kuŕũ, urt. kŕä̃ (< *kaṇ), Bshk. kan, Tor. k *l ṇ, Kand. kōṇi, Mai. kaṇa, ky. kān, Phal. kāṇ, Sh. gil. ko̯n pl. ko̯ṇí m. (→ Ḍ kon pl. k *l ṇa), koh. kuṇ, pales. kuāṇƏ, K. kan m., kash. pog. ḍoḍ. kann, S. kanu m., L. kann m., awāṇ. khet. kan, P. WPah. bhad. bhal. cam. kann m., Ku. gng. N. kān; A. kāṇ ‘ear, rim of vessel, edge of river’; B. kāṇ ‘ear’, Or. kāna, Mth. Bhoj. Aw. lakh. H. kān m., OMarw. kāna m., G. M. kān m., Ko. kānu m., Si. kaṇa, kana. — As adverb and postposition (ápi kárṇē ‘from behind’ RV., karṇē ‘aside’ Kālid.): Pa. kaṇṇē ‘at one's ear, in a whisper’; Wg. ken ‘to’ NTS ii 279; Tir. kõ; ‘on’ AO xii 181 with (?); Paš. kan ‘to’; K. kȧni with abl. ‘at, near, through’, kani with abl. or dat. ‘on’, kun with dat. ‘toward’; S. kani ‘near’, kanā̃ ‘from’; L. kan ‘toward’, kannũ ‘from’, kanne ‘with’, khet. kan, P. ḍog. kanē ‘with, near’; WPah. bhal. k *l ṇ, °ṇi, k e ṇ, °ṇi with obl. ‘with, near’, kiṇ, °ṇiā̃, k *l ṇiā̃, k e ṇ° with obl. ‘from’; Ku. kan ‘to, for’; N. kana ‘for, to, with’; H. kane, °ni, kan with ke ‘near’; OMarw. kanai ‘near’, kanā̃ sā ‘from near’, kā̃nı̄̃ ‘towards’; G. kan e ‘beside’. Addenda: kárṇa—: S.kcch. kann m. ‘ear’, WPah.kṭg. (kc.) kān, poet. kanṛu m. ‘ear’, kṭg. kanni f. ‘pounding—hole in barn floor’; J. kā'n m. ‘ear’, Garh. kān; Md. kan— in kan—fat ‘ear’ (CDIAL 2830)

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Rigveda) kolom 'thre' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'

kolom 'thre' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge' kolami mūhā 'ingot (for)smithy,forge ingot'

kolami mūhā 'ingot (for)smithy,forge ingot'Thus, the message of the text on the Mohenjo-daro prism tablet of a boat + crocodile + fish is: supercargo of kolami mūhā 'smithy,forge ingots' dul mūhā 'cast metal ingots'. The metal is sinified as ayas.

mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)

mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends (Santali)

Maysar c.2200 BCE Packed copper ingots. The shape of the ingots is an 'equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends' -- like an ellipse or rhombus. See:

See: http://nautarch.tamu.edu/pdf-files/JonesM-MA2007.pdf Michael Rice Jones' thesis of 2007 on the importance of Maysar for copper production.

An ingot may be signified by an ellipse or parenthesis of a rhombus. It may also be signified by an allograph: human face.

Hieroglyph: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; kolhe tehen me~ṛhe~t mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron(Santali) Rebus: mūhā 'ingot'; Compound formation: mleccha-mukha (Skt.) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali)

Santali glosses

Santali glossesWilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:

Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.

Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'.

~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).

Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.

Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.

KW <i>mENhEd</i>

@(V168,M080)

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

A lexicon suggests the semantics of Panini's compound अयस्--काण्ड [p= 85,1] m. n. " a quantity of iron " or " excellent iron " , (g. कस्का*दि q.v.)( Pa1n2. 8-3 , 48)(Monier-Williams).

From the example of a compound gloss in Santali, I suggest that the suffix -kANDa in Samskritam should have referred to 'implements'. Indus Script hieroglyphs as hypertext components to signify kANDa 'implements' are: kANTa, 'overflowing water' kANDa, 'arrow' gaNDa, 'four short circumscript strokes''rhonoceros'.

Hieroglyph: gaṇḍá4 m. ʻ rhinoceros ʼ lex., °aka -- m. lex. 2. *ga- yaṇḍa -- . [Prob. of same non -- Aryan origin as khaḍgá -- 1 : cf. gaṇōtsāha -- m. lex. as a Sanskritized form ← Mu. PMWS 138]1. Pa. gaṇḍaka -- m., Pk. gaṁḍaya -- m., A. gãr, Or. gaṇḍā.2. K. gö̃ḍ m.,S. geṇḍo m. (lw. with g -- ), P. gaĩḍā m., °ḍī f., N. gaĩṛo, H. gaĩṛā m., G. gẽḍɔ m., °ḍī f., M. gẽḍā m.Addenda: gaṇḍa -- 4 . 2. *gayaṇḍa -- : WPah.kṭg. ge ṇḍɔ mi rg m. ʻ rhinoceros ʼ, Md. genḍā ← (CDIAL 4000) காண்டாமிருகம் kāṇṭā-mirukam , n. [M. kāṇṭāmṛgam.] Rhinoceros;

கல்யானை. খাঁড়া (p. 0277) [ khān̐ḍ়ā ] n a large falchion used in immolat ing beasts; a large falchion; a scimitar; the horny appendage on the nose of the rhinoceros.গণ্ডক (p. 0293) [ gaṇḍaka ] n the rhinoceros; an obstacle; a unit of counting in fours; a river of that name.গন্ডার (p. 0296) [ ganḍāra ] n the rhinoceros.(Bengali. Samsad-Bengali-English Dictionary) गेंडा [ gēṇḍā ] m (

Rebus: *gaṇḍāsi ʻ sugarcane knife ʼ. [gaṇḍa -- 2 , así -- ]Bi. gãṛās, °sā ʻ fodder cutter ʼ, °sī ʻ its blade ʼ; Bhoj. gãṛās ʻ a partic. iron instrument ʼ; H. gãṛāsī f., °sā m. ʻ knife for cutting fodder or sugarcane ʼ (→ P. gãḍāsā m. ʻ chopper for cutting fodder &c. ʼ).(CDIAL 4004) gaṇḍa2 m. ʻ joint of plant ʼ lex., gaṇḍi -- m. ʻ trunk of tree from root to branches ʼ lex. 2. *gēṇḍa -- . 3. *gēḍḍa -- 2 . 4. *gēḍa -- 1 . [Cf. kāˊṇḍa -- : prob. ← Drav. DED 1619]

1. Pa. gaṇḍa -- m. ʻ stalk ʼ, °ḍī -- f. ʻ sugarcane joint, shaft or stalk used as a bar ʼ, Pk. gaṁḍa -- m., °ḍiyā -- f.; Kt. gäṇa ʻ stem ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. gaṇḍīˊ ʻ stem, stump of a tree, large roof beam ʼ (→ Par. gaṇḍāˊ ʻ stem ʼ, Orm. goṇ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL i 253, 395), gul. geṇḍū, nir. gaṇīˊ, kuṛ. gã̄ṛo; Kal. urt. gəṇ ʻ log (in a wall) ʼ, rumb. goṇ (st.gōṇḍ -- ) ʻ handle ʼ, guṇḍík ʻ stick ʼ; Kho. (Lor.) gon, gonu, (Morgenstierne) gɔ̄ˋn ʻ haft of axe, spade or knife ʼ (or <ghaná -- 2 ?); K. gonḍu , grọ̆nḍu m. ʻ great untrimmed log ʼ; S. ganu m.ʻ oar, haft of a tool ʼ, °no m. ʻ sweet stalks of millet ʼ; P. gannā m. ʻ sugarcane ʼ (→ H. gannā m.), Bi. gaṇḍā, H. gã̄ṛā m., M. gã̄ḍā m. -- Deriv. Pk. gaṁḍīrī -- f. ʻ sugarcane joint ʼ; Bhoj. gãṛērī ʻ small pieces of sugarcane ʼ; H. gãḍerī f. ʻ knot of sugarcane ʼ; G. gãḍerī f. ʻ piece of peeled sugarcane ʼ; -- Pk. gaṁḍalī -- ʻ sugarcane joint ʼ; Kal. rumb. gaṇḍau (st. °ḍāl -- ) ʻ ancestor image ʼ; S. g̠anaru m. ʻ stock of a vegetable run to seed ʼ.2. Ku. gino ʻ block, log ʼ; N. gĩṛ ʻ log ʼ, gĩṛo ʻ piece of sugarcane ʼ (whence gẽṛnu, gĩṛ° ʻ to cut in pieces ʼ); B. gẽṛ ʻ tuber ʼ; Mth. gẽṛī ʻ piece of sugarcane chopped ready for the mill ʼ.3. Pk. geḍḍī -- , giḍḍiā -- f. ʻ stick ʼ; P. geḍī f. ʻ stick used in a game ʼ, H. geṛī f. (or < 4).4. N. gir, girrā ʻ stick, esp. one used in a game ʼ, H. gerī f., geṛī f. (or < 3), G. geṛī f.*gaṇḍāsi -- ; *agragaṇḍa -- , *prāgragaṇḍa -- .Addenda: gaṇḍa -- 2 : S.kcch. gann m. ʻ handle ʼ; -- WPah.kṭg. gannɔ m. ʻ sugar -- cane ʼ; Md. gan̆ḍu ʻ piece, page, playing -- card ʼ.(CDIAL 3998)

1. Pa. gaṇḍa -- m. ʻ stalk ʼ, °ḍī -- f. ʻ sugarcane joint, shaft or stalk used as a bar ʼ, Pk. gaṁḍa -- m., °ḍiyā -- f.; Kt. gäṇa ʻ stem ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. gaṇḍīˊ ʻ stem, stump of a tree, large roof beam ʼ (→ Par. gaṇḍāˊ ʻ stem ʼ, Orm. goṇ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL i 253, 395), gul. geṇḍū, nir. gaṇīˊ, kuṛ. gã̄ṛo; Kal. urt. gəṇ ʻ log (in a wall) ʼ, rumb. goṇ (st.gōṇḍ -- ) ʻ handle ʼ, guṇḍík ʻ stick ʼ; Kho. (Lor.) gon, gonu, (Morgenstierne) gɔ̄ˋn ʻ haft of axe, spade or knife ʼ (or <

Rebus: kāˊṇḍa (kāṇḍá -- TS.) m.n. ʻ single joint of a plant ʼ AV., ʻ arrow ʼ MBh., ʻ cluster, heap ʼ (in tr̥ṇa -- kāṇḍa -- Pāṇ. Kāś.). Pa. kaṇḍa -- m.n. ʻ joint of stalk, stalk, arrow, lump ʼ; Pk. kaṁḍa -- , °aya -- m.n. ʻ knot of bough, bough, stick ʼ; Ash. kaṇ ʻ arrow ʼ, Kt. kåṇ, Wg. kāṇ,, Pr.kə̃, Dm. kā̆n; Paš. lauṛ. kāṇḍ, kāṇ, ar. kōṇ, kuṛ. kō̃, dar. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ torch ʼ; Shum. kō̃ṛ, kō̃ ʻ arrow ʼ, Gaw. kāṇḍ, kāṇ; Bshk. kāˋ'nʻ arrow ʼ, Tor. kan m., Sv. kã̄ṛa, Phal. kōṇ, Sh. gil. kōn f. (→ Ḍ. kōn, pl. kāna f.), pales. kōṇ; K. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ stalk of a reed, straw ʼ (kān m. ʻ arrow ʼ ← Sh.?); S. kānu m. ʻ arrow ʼ, °no m. ʻ reed ʼ, °nī f. ʻ topmost joint of the reed Sara, reed pen, stalk, straw, porcupine's quill ʼ; L. kānã̄ m. ʻ stalk of the reed Sara ʼ, °nī˜ f. ʻ pen, small spear ʼ; P. kānnā m. ʻ the reed Saccharum munja, reed in a weaver's warp ʼ, kānī f. ʻ arrow ʼ; WPah. bhal. kān n. ʻ arrow ʼ, jaun. kã̄ḍ; N. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, °ṛo ʻ rafter ʼ; A. kã̄r ʻ arrow ʼ; B. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, °ṛā ʻ oil vessel made of bamboo joint, needle of bamboo for netting ʼ, kẽṛiyā ʻ wooden or earthen vessel for oil &c. ʼ; Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻ stalk, arrow ʼ; Bi. kã̄ṛā ʻ stem of muñja grass (used for thatching) ʼ; Mth. kã̄ṛ ʻ stack of stalks of large millet ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ wooden milkpail ʼ; Bhoj. kaṇḍā ʻ reeds ʼ; H. kã̄ṛī f. ʻ rafter, yoke ʼ, kaṇḍā m. ʻ reed, bush ʼ (← EP.?); G. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ joint, bough, arrow ʼ, °ḍũ n. ʻ wrist ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint, bough, arrow, lucifer match ʼ; M. kã̄ḍ n. ʻ trunk, stem ʼ, °ḍẽ n. ʻ joint, knot, stem, straw ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint of sugarcane, shoot of root (of ginger, &c.) ʼ; Si. kaḍaya ʻ arrow ʼ. -- Deriv. A. kāriyāiba ʻ to shoot with an arrow ʼ.kāˊṇḍīra -- ; *kāṇḍakara -- , *kāṇḍārā -- ; *dēhīkāṇḍa -- Add.Addenda: kāˊṇḍa -- [< IE. *kondo -- , Gk. kondu/los ʻ knuckle ʼ, ko/ndos ʻ ankle ʼ T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 55]S.kcch. kāṇḍī f. ʻ lucifer match ʼ?kāṇḍakara 3024 *kāṇḍakara ʻ worker with reeds or arrows ʼ. [kāˊṇḍa -- , kará -- 1]L. kanērā m. ʻ mat -- maker ʼ; H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers ʼ.*kāṇḍārā ʻ bamboo -- goad ʼ. [kāˊṇḍa -- , āˊrā -- ]Mth. (ETirhut) kanār ʻ bamboo -- goad for young elephants ʼ kāˊṇḍīra ʻ armed with arrows ʼ Pāṇ., m. ʻ archer ʼ lex. [kāˊṇḍa -]H. kanīrā m. ʻ a caste (usu. of arrow -- makers) ʼ.(CDIAL 3024-3026)

An insight in the orthography of Indus Script hieroglyphs is the matching of orthographic components with the semantics of the message in Meluhha (Prakritam).

A unique example is the deployment of an ellipse (also as a rhombus or parenthesis) to signify the semantics of mūhā '(metal) ingot'. An allograph also signifies the semantics: mũhe ‘face’.

Semantics: mūhā mẽṛhẽt 'iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends.' Matching orthography of a rhombus or ellipse:

A Rakhigarhi seal presents an alternative orthographic representation of the 'split ellipse':

((

That this innovation signifies rebus kaNDa 'arrow' is reinforced by the phonetic determinant of 'arrow' used in the hieroglyph-multiplex, resulting in the new 'sign' shown below:

On this hieroglyph-multiplex, one parenthesis is FLIPPED to create a new circumgraph of two orthographic components:

( Left parenthesis

Note: The splitting of the ellipse 'ingot' into Right and Left parethesis and flipping the left parenthesis (as a mirror image) may be an intention to denote cire perdue casting method used to produce the metal swords and implements.

An alternative hieroglyph is a rhombus or ellipse (created by merging the two forms: parnthesis PLUS fipped parenthesis) to signify an 'ingot': mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end (Munda).

This circumgraph of right-curving and left-curving parentheses encloses an 'arrow' hieroglyph PLUS a 'notch'.

Hieroglyph: kANDa 'arrow' Rebus: kaṇḍ '

This gloss is consistent with the Santali glosses including the word khanDa:

Hieroglyph: खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon) (Marathi) Rebus: kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (

What the hieroglyph-multiplex seeks to convey is that the seal as a metalwork catalogue documents the process of making kāṇḍa 'metal implements' from the fire-altar kaND signified by the arrow AND circumfix of split parentheses with one parenthesis presented as a unique flipped configuration. Thus the hieroglyph-multiplex is an orthographic reinforcement of the two other hieroglyphs signified on the Rakhigarhi seal; the two other hieroglyphs are: kANDa 'rhinoceros'; kANDa 'arrow'. Thus, all the three signifiers on the Indus Script inscription of Rakhigarhi seal are a proclamation of the production of metal implements (from ingots). There is also a Meluhha (Prakritam) gloss khaṁḍa which means 'a sword'. It is possible that the concluding sign on the inscription read from left to right signifies 'sword'.

Thus, the Rakhigarhi seal inscription can be read in Prkritam: khaṁḍa 'sword' PLUS खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] 'metal implements', more specifically, recorded as a Santali compound expression:

*khaṇḍaka3 ʻ sword ʼ. [Perh. of same non -- Aryan origin as khaḍgá -- 2 ]

Pk. khaṁḍa -- m. ʻ sword ʼ (→ Tam. kaṇṭam), Gy. SEeur. xai̦o, eur. xanro, xarno, xanlo, wel. xenlī f., S. khano m., P. khaṇḍā m., Ku. gng. khã̄ṛ, N. khã̄ṛo, khũṛo (Xchuri <kṣurá -- ); A. khāṇḍā ʻ heavy knife ʼ; B. khã̄rā ʻ large sacrificial knife ʼ; Or. khaṇḍā ʻ sword ʼ, H. khã̄ṛā, G. khã̄ḍũ n., M. khã̄ḍā m., Si. kaḍuva.(CDIAL 3793).

Pk. khaṁḍa -- m. ʻ sword ʼ (→ Tam. kaṇṭam), Gy. SEeur. xai̦o, eur. xanro, xarno, xanlo, wel. xenlī f., S. khano m., P. khaṇḍā m., Ku. gng. khã̄ṛ, N. khã̄ṛo, khũṛo (Xchuri <

Figure 4: (A) Seal RGR 7230 from Rakhigarhi. (B) The side of the seal where surface has partially worn away revealing the black steatite beneath. (C) A swan black steatite debris fragment from Harappa.

An ingot may be signified by an ellipse or parenthesis of a rhombus. It may also be signified by an allograph: human face.

Hieroglyph: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; kolhe tehen me~ṛhe~t mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) Rebus: mūhā 'ingot'; Compound formation: mleccha-mukha (Skt.) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali)

See:Previous report http://asi.nic.in/pdf_data/rakhigarhi_excavation_report_new.pdf Excavations at Rakhigarhi 1997 to 2000 (Dr. Amarendranath)

Rebus: kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, iron smelters speaking a language akin to that

of Santals’ (Santali) kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil)

I suggest that the language spoken by the Sarasvati's children was Meluhha

(Mleccha), a spoken, vernacular version of Vedic chandas. This may also be

called Proto-Prakritam, not unlike Ardhamaadhi identified by Jules Bloch in

his work: Formation of Marathi Language.

A three-centimetre seal with the Harappan script. It has no engraving of any animal motif.Source: http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/heritage/harappan-surprises/article6032206.ece

See:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/what-did-harappans-eat-how-did-they.html

http://asi.nic.in/pdf_data/rakhigarhi_excavation_report_new.pdf

kuṭire bica duljad.ko talkena, they were feeding the furnace with ore. In this Santali sentence bica denotes the hematite ore. For example, samṛobica, 'stones containing gold' (Mundari) meṛed-bica 'iron stone-ore' ; bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda). mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’(Munda. Ho.)

Meluhha rebus representations are: bica ‘scorpion’ bica ‘stone ore’ (hematite).

pola (magnetite), gota (laterite), bichi (hematite). kuṇṭha munda (loha) a type of hard native metal, ferrous oxide.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/asur-metallurgists.html

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/09/catalogs-of-pola-kuntha-gota-bichi.html#! Hieroglyph: pōḷī, ‘dewlap' पोळ [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large (Marathi) Rebus: pola (magnetite)

ḍaṅgra 'bull' Rebus: ḍāṅgar, ḍhaṅgar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi).

. See:http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2013/06/asur-metallurgists.html Magnetite a type of iron ore is called POLA by the Asur (Meluhha).

Reading the Indus writing inscriptions on both sides of bun-shaped lead ingots of Rakhigarhi

The Indus writing inscriptions relate to cataloging of metalwork as elaborated by the following rebus-metonymy cipher and readings in Meluhha (Indian sprachbund):

meD 'body' kATi 'body stature' Rebus: meD 'iron' kATi 'fireplace trench'. Thus, iron smelter.

koDa 'one' Rebus: koD 'workshop'

kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'

baTa 'rimless pot' Rebus: baTa 'furance'

kanka, karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNi 'supercargo'; karNika 'account'.

A spoked wheel is ligatured within a rhombus: kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'; eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'copper, moltencast'

See many variants of 'body' hieroglyph and ligatures at

https://www.academia.edu/8408578/Stature_of_body_Meluhha_hieroglyphs_48_in_Indus_writing_catalogs_of_metalwork_processes

Figure 14: Side (A) and top (B) views of a lead ingot inscribed with Harappan characters. Detailed images of the top (C) and bottom (D) inscriptions.

Figure 1: Steatite sources of the Greater Indus region and Harappan steatite trade networks.

Figure 6: (A) Unicorn seal fragment #6304. (B) Detail of the grayish-green steatite of the seal's interior

Figure 9: Agate-carnelian nodule fragments and flakes from Rakhigarhi

Figure 18: Lead and silver artifacts from Rakhigarhi compared to South Asian lead and lead-silver sources.

Figure 29: Saddle quern (left) and fragment (right) composed of a deep red sandstone of unknown origin.

Figure 30: Hematite cobbles/nodules of unknown origin. Geologic provenience studies of Rakhigarh's stone and metal artifact assemblage are ongoing or in the planning stages.

Figure 31: Rakhigarhi grindingstone acquisition networks

Figure 32: Rakhigarhi stone and metal sources and acquisition networks identified in this study. Potential, but as of yet unconfirmed, copper, gold and chert source areas are also indicated.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/11/indus-script-dhatu-scarf-on-rhinoceros.html

L. mirhõ, °hũ, pl. °hẽ m. ʻ boar ʼ (mirhõ ʻ ravine deer ʼ for *mirũ < *mr̥garūpa -- ?).mr̥gá -- usu. is ʻ markhor ʼ in Dard. AO viii 306.Wg. mre č ʻ ibex ʼ

مته matœh, s.m. (6th) A wild boar. Sing. and Pl.See سډر and سرکوزي(Pashto)