Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/hbvzn4t

This is my humble tribute to Radha Gupta, Suman Agarwal & Vipin Kumar who have created a remarkable database of ancient texts with lucid explanations. This is an outstanding contribution to ancient civilization studies of Bhāratam Janam

Thanks to Vipin Kumar ji for the following comment and the link to a noteworthy Puranic indexing system with links to an extensive body of ancient texts:

This is my humble tribute to Radha Gupta, Suman Agarwal & Vipin Kumar who have created a remarkable database of ancient texts with lucid explanations. This is an outstanding contribution to ancient civilization studies of Bhāratam Janam

Thanks to Vipin Kumar ji for the following comment and the link to a noteworthy Puranic indexing system with links to an extensive body of ancient texts:

"Vrisha stambha referred in Vastusutropanishada and explained through vrishotsarga can be understood on the basis of ghora and aghora. Ghora (bull in vernacular) means ferocious and aghora means non-ferocious. So, for vrisha stambha, it can be said that to make life forces non ferocious is the aim of vrisha stambha."

Note: उत्-सर्ग a [p= 182,1] granting , gift , donation MBh. oblation , libation; presentation (of anything promised to a god or Brahman with suitable ceremonies); a particular ceremony on suspending repetition of the वेद Mn. iv , 97 ; 119 Ya1jn5. &c; causation , causing Jaim. iii , 7 , 19 (Monier-Williams) See: वृषोत्सर्ग विधि पर टिप्पणी (appended).

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/12/kalibangan-binjor-evidence-for-vajapeya.html Kalibangan & Binjor evidence for Vājapeya सोमः संस्था यज्ञ, yajña yūpa, related Indus Script inscriptions, linga, skambha Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/z8vmh23 The significance of yūpa and the extensive presence of mleccha in ancient Bhāratam get corroborated by textual evidence of Vedic tradition. This is an indicator that the Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization archaeo-metallurgical heritage is a continuum of Vedic culture and reinforces the essential unity of Indian sprachbund. This concusion calls for a revisit to the linguistic heritage of Prākritam, as the parole of Chandas. Sangam literature, Sangam Age coins, Ancient coins of Taxila, Eran, Vidisha also attest to the Vedic culture continuum exemplified by the Rajasthan Yupa inscriptions and East Borneo Mulavarman Yupa inscriptions of historical periods of Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/12/sangam-texts-and-ancient-coins-of-india.html

Kalibangan & Binjor evidence for Vājapeya सोमः संस्था यज्ञ, yajña yūpa, related Indus Script inscriptions, linga, skambha Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/z8vmh23

The significance of yupa and the extensive presence of mleccha in ancient Bharatam get corroborated by textual evidence of Vedic tradition. This is an indicator that the Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization archaeometallurgical heritage is a continuum of Vedic culture and reinforces the essential unity of Indian sprachbund calling for a revisit to the received wisdom of the linguistic heritage of Prakritam, the parole of Chandas.

म्लेच्छ पद्म १.४७.६७ (विभिन्न दिशाओं में म्लेच्छों के लक्षण, गरुड द्वारा म्लेच्छों का भक्षण व उद्वमन), ब्रह्माण्ड १.२.१८.४३(बिन्दुसरोवर से प्रसूत ७ नदियों द्वारा म्लेच्छप्राय देशों को प्लावित करने का उल्लेख), भविष्य ३.१.३.९६(म्लेच्छों द्वारा क्षेमक का वध होने पर क्षेमक - पुत्र प्रद्योत द्वारा नारद के उपदेश से म्लेच्छ यज्ञ करके म्लेच्छों का हनन), ३.१.४.५(प्रद्योत - कृत म्लेच्छ यज्ञ का वर्णन), ३.१.४.४१(आचार, विवेक आदि से युक्त मनुष्य के म्लेच्छ होने? का कथन ; म्लेच्छ वंश का कथन), ३.३.२.२०(शालिवाहन नृप द्वारा आर्यों व म्लेच्छों की मर्यादा की स्थापना, सिन्धु स्थान की आर्यों के लिए और सिन्धु से परे म्लेच्छों के लिए स्थापना, म्लेच्छ देश में ईशामसीह की स्थापना), ३.३.३.१७(वाहीक देशस्थ महामद की म्लेच्छ धर्म में मति), भागवत ९.१६.३३(विश्वामित्र द्वारा पुत्र मधुच्छन्दा के अग्रजों को म्लेच्छ होने का शाप), ९.२०.३०(दुष्यन्त - पुत्र भरत द्वारा म्लेच्छों के हनन का उल्लेख), ९.२३.१६(द्रुह्यु के वंशज १०० प्राचेतसों के म्लेच्छाधिपति होने का उल्लेख),मत्स्य १०.७(वेन के शरीर के माता के अंश से म्लेच्छ जातियों की उत्पत्ति का कथन), १६.१६(श्राद्ध में म्लेच्छ देश के निवासियों के वर्जन का निर्देश), ३३.१४(ययाति द्वारा पुत्र तुर्वसु को पापी म्लेच्छों में जन्म? लेने का शाप), ११४.११(भारतवर्ष के अन्तों में म्लेच्छों के निवास का उल्लेख), १२१.४३(बिन्दु सरोवर से प्रसूत ७ नदियों द्वारा म्लेच्छप्राय देशों को प्लावित करने का कथन, म्लेच्छ देशों के नाम), १४४.५१(प्रमति/कल्कि अवतार द्वारा म्लेच्छों के वध का उल्लेख), १८१.१९(अविमुक्त क्षेत्र में मृत्यु पर म्लेच्छ आदियों की मुक्ति का उल्लेख), २७३.२५(आर्य व म्लेच्छ जनपदों के धार्मिक यवनों से मिश्रित होने तथा कल्कि अवतार द्वारा अधार्मिक आर्यों व म्लेच्छों को नष्ट करने का कथन), महाभारत कर्ण ४५.३६(म्लेच्छों की स्वसंज्ञानियत विशेषता का उल्लेख), लक्ष्मीनारायण २.३७.६८(डफ्फर/दिक्फर जातीय म्लेच्छों का सौराष्ट} में उपद्रव, श्रीहरि द्वारा सुदर्शन चक्र से म्लेच्छों का निग्रह), २.५०-५४(अबि|क्त देश के म्लेच्छों द्वारा दिव्य विमान और उसमें आसीन दिव्य कन्याओं को प्राप्त करने का यत्न, विमानवासी देवों व म्लेच्छों का युद्ध, म्लेच्छों का नाश आदि ) mlechchha

Yupa is also linked with a particular form called Vrisha Stambha. Hence, also the link with the ekamukha sivalinga evidenced in Bhutesvar -- and Indus Script hieroglyph for kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'.

It was noted in this monograph that

1) the dotted-circle and trefoil hieroglyphs on the uttariyam (shawl) of the statue of the priest signified respectively, single strand of rope and three strands of rope; and

element of words i.e. grammatical or verbal root or stem Nir. Pra1t. MBh. &c

(with the southern Buddhists धातु means either the 6 elements [see above] Dharmas. xxv ; or the 18 elementary spheres [धातु-लोक] ib. lviii ; or the ashes of the body , relics L. [cf. -गर्भ]).

Orthographically, the single strand and three strands are signified as follows:

The fillet worn on the forehead and on the right-shoulder signifies one strand; while the trefoil on the shawl signifies three strands. A hieroglyph for two strands is also signified.

The fillet worn on the forehead and on the right-shoulder signifies one strand; while the trefoil on the shawl signifies three strands. A hieroglyph for two strands is also signified.These orthographic variants provide semantic elucidations for a single: dhātu, dhāū, dhāv 'red stone mineral' or two minerals: dul PLUS dhātu, dhāū, dhāv 'cast minerals' or tri- dhātu, -dhāū, -dhāv 'three minerals' to create metal alloys'. The artisans producing alloys are dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron -- smeltersʼ, dhāvḍī ʻcomposed of or relating to ironʼ)(CDIAL 6773)..

dām 'rope, string' rebus: dhāu 'ore' rebus: मेढा [mēḍhā] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ 'iron, copper' (Munda. Slavic) mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda).

mũh 'a face' in Indus Script Cipher signifies mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/10/indus-script-corpora-face-hieroglyph-is.html

An aniconic Sivalinga ligatured with a 'face' is thus a signifier associating Sivalinga with the smelting process in a smelter which results in an ingot or mmuhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.'

This Indus Script evidence is the explanation for ekamukha linga and linga with multiple faces which are orthographic variants of the singe-strand, double-strand, three strands denoted on the priest statue of Mohenjodaro respectively as dotted circle, pair of dotted circles and three dotted circles joined together as a trefoil. Evidences for such sivalingas abound in Bharat that is India and many parts of South Asia. Bharat is a name of the nation mentioned by Rishi Visvamitra in Rigveda (RV 3.53.12) referring to Bharatam Janam, an expression derived from the gloss: bharata 'factitious alloy of copper, pewter and tin'. Thus, Bharatam Janam means 'metalcaster folk'. The association of these folk as worshippers of Siva in aniconic form of linga for millennia and a worship which continues even today is standing testimony to the Indus Script Cipher which documents smelting processes with one ore, two metallic ores, three metallic ores and processes of metal casting.

It is significant that the trefoil hieroglyph is also signified on the base which held a sivalinga.

Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218.

Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218. Two decorated bases and a lingam, Mohenjodaro.

Two decorated bases and a lingam, Mohenjodaro.Lingam, grey sandstone in situ, Harappa, Trench Ai, Mound F, Pl. X (c) (After Vats). "In an earthenware jar, No. 12414, recovered from Mound F, Trench IV, Square I... in this jar, six lingams were found along with some tiny pieces of shell, a unicorn seal, an oblong grey sandstone block with polished surface, five stone pestles, a stone palette, and a block of chalcedony..." (Vats, MS, 1940, Excavations at Harappa, Vol. II, Calcutta, p. 370) "In the adjoining Trench Ai, 5 ft. 6 in. below the surface, was found a stone lingam [Since then I have found two stone lingams of a larger size from Trenches III and IV in this mound. Both of them are smoothed all over]. It measures 11 in. high and 7 3/8 in. diameter at the base and is rough all over.’ (Vol. I, pp. 51-52)." Shiva Lingas at Harappa, dating more than 5,000 years old. Worship of Sivalingam has continued for millennia, uninterrupted. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/04/sivalinga-in-dholavira-depicted-as.htmlSee: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/10/skambha-sukta-in-atharva-veda-and.html

![]() Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE (Fig. 6.2). This is the most emphatic representation of linga as a pillar of fire. The pillar is embedded within a brick-kiln with an angular roof and is ligatured to a tree. Hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. In this composition, the artists is depicting the smelter used for smelting to create mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) of mēḍha 'stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda). मेड (p. 662) [ mēḍa ] f (Usually

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE (Fig. 6.2). This is the most emphatic representation of linga as a pillar of fire. The pillar is embedded within a brick-kiln with an angular roof and is ligatured to a tree. Hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. In this composition, the artists is depicting the smelter used for smelting to create mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) of mēḍha 'stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda). मेड (p. 662) [ mēḍa ] f (Usually मेढ q. v.) मेडका m A stake, esp. as bifurcated. मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] f A forked stake. Used as a post. Hence a short post generally whether forked or not. मेढा (p. 665) [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. 2 A dense arrangement of stakes, a palisade, a paling. मेढी (p. 665) [ mēḍhī ] f (Dim. of मेढ ) A small bifurcated stake: also a small stake, with or without furcation, used as a post to support a cross piece. मेढ्या (p. 665) [ mēḍhyā ] a (मेढ Stake or post.) A term for a person considered as the pillar, prop, or support (of a household, army, or other body), the staff or stay. मेढेजोशी (p. 665) [ mēḍhējōśī ] m A stake-जोशी ; a जोशी who keeps account of the तिथि &c., by driving stakes into the ground: also a class, or an individual of it, of fortune-tellers, diviners, presagers, seasonannouncers, almanack-makers &c. They are Shúdras and followers of the मेढेमत q. v. 2 Jocosely. The hereditary or settled (quasi fixed as a stake) जोशी of a village.मेंधला (p. 665) [ mēndhalā ] m In architecture. A common term for the two upper arms of a double चौकठ (door-frame) connecting the two. Called also मेंढरी & घोडा . It answers to छिली the name of the two lower arms or connections. (Marathi)

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda)

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/a-critique-of-general-theory-of-images.html for the sculpture of three stakes on Sit Shamshi bronze.Atharva Veda (X.8.2) declares that Heaven and Earth stand fast being pillared apart by the pillar. Like the pillar, twilight of the dawn and dusk split apart the originally fused Heaven and Earth.Light of dawn ‘divorces the coterminous regions – Sky and Earth – and makes manifest the several worlds. (RV VII.80; cf. VI.32.2, SBr. IV 6.7.9).‘Sun is spac, for it is only when it rises that the world is seen’ (Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana I.25.1-2). When the sun sets, space returns into the void (JUB III.1.1-2).Indra supports heavn and earth by ‘opening the shadows with the dawn and the sun’. (RV I.62.5). He ‘extends heaven by the sun; and the sun is the prp whereby he struts it.’ (RV X.111.5).‘He who knows the Brahman in man knows the Supreme Being and he who knows the Supreme Brahman knows the Stambha’. (AV X. 7.17).Linga-Purana (I.17.5-52; 19.8 ff.) provides a narrative. Siva appeared before Brahma and Vishnu as a fiery linga with thousands of flames. As a Goose, Brahma attempted to fly to the apex of the column; Vishnu as a Boar plunged through the earth to find the foot of the blazing column. Even after a thousand years, they couldn’t reach the destination, bow in homage to the Pillar of the Universe as the Paramaatman.

He is the ‘Pillar supporting the kindreds, that is, gods and men’. (RV I.59.1-2). He is the standard (ketu) of the yajna (equivalent of the dawn), the standard which supports heaven in the East at daybreak. (RV I.113.19; III.8.8).![]() Worship of linga by Gandharva, Shunga period (ca. 2nd cent. BCE), ACCN 3625, Mathura Museum. Worship signified by dwarfs, Gaṇa (hence Gaṇeśa = Gaṇa + īśa).

Worship of linga by Gandharva, Shunga period (ca. 2nd cent. BCE), ACCN 3625, Mathura Museum. Worship signified by dwarfs, Gaṇa (hence Gaṇeśa = Gaṇa + īśa).

![]() Architectural fragment with relief showing winged dwarfs (or gaNa) worshipping with flower garlands, Siva Linga. Bhuteshwar, ca. 2nd cent BCE. Lingam is on a platform with wall under a pipal tree encircled by railing. (Srivastava, AK, 1999, Catalogue of Saiva sculptures in Government Museum, Mathura: 47, GMM 52.3625) The tree is a phonetic determinant of the smelter indicated by the railing around the linga: kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ lex., °ṭaka -- m. ʻ a kind of tree ʼ Kauś.Pk. kuḍa -- m. ʻ tree ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. kuṛāˊ ʻ tree ʼ, dar. kaṛék ʻ tree, oak ʼ ~ Par. kōṛ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL iii 3, 98. (CDIAL 3228).

Architectural fragment with relief showing winged dwarfs (or gaNa) worshipping with flower garlands, Siva Linga. Bhuteshwar, ca. 2nd cent BCE. Lingam is on a platform with wall under a pipal tree encircled by railing. (Srivastava, AK, 1999, Catalogue of Saiva sculptures in Government Museum, Mathura: 47, GMM 52.3625) The tree is a phonetic determinant of the smelter indicated by the railing around the linga: kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ lex., °ṭaka -- m. ʻ a kind of tree ʼ Kauś.Pk. kuḍa -- m. ʻ tree ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. kuṛāˊ ʻ tree ʼ, dar. kaṛék ʻ tree, oak ʼ ~ Par. kōṛ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL iii 3, 98. (CDIAL 3228).

In Atharva Veda stambha is a celestial scaffold, supporting the cosmos and material creation.See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/12/skambha-sukta-atharva-veda-x-7-pair-of.html Full text of Atharva Veda ( X - 7,8) --- Stambha Suktam with translation (with variant pronunciation as skambha). See Annex A List of occurrences of gloss in Atharva Veda. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/smithy-is-temple-of-bronze-age-stambha_14.html In this text, linga is elaborated as a fiery pillar of light.

Atharva Veda (X.8.2) declares that Heaven and Earth stand fast being pillared apart by the pillar. Like the pillar, twilight of the dawn and dusk split apart the originally fused Heaven and Earth.

Light of dawn ‘divorces the coterminous regions – Sky and Earth – and makes manifest the several worlds. (RV VII.80; cf. VI.32.2, SBr. IV 6.7.9).

‘Sun is spac, for it is only when it rises that the world is seen’ (Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana I.25.1-2). When the sun sets, space returns into the void (JUB III.1.1-2).

Indra supports heavn and earth by ‘opening the shadows with the dawn and the sun’. (RV I.62.5). He ‘extends heaven by the sun; and the sun is the prp whereby he struts it.’ (RV X.111.5).

‘He who knows the Brahman in man knows the Supreme Being and he who knows the Supreme Brahman knows the Stambha’. (AV X. 7.17).

Linga-Purana (I.17.5-52; 19.8 ff.) provides a narrative. Siva appeared before Brahma and Vishnu as a fiery linga with thousands of flames. As a Goose, Brahma attempted to fly to the apex of the column; Vishnu as a Boar plunged through the earth to find the foot of the blazing column. Even after a thousand years, they couldn’t reach the destination, bow in homage to the Pillar of the Universe as the Paramaatman.

He is the ‘Pillar supporting the kindreds, that is, gods and men’. (RV I.59.1-2). He is the standard (ketu) of the yajna (equivalent of the dawn), the standard which supports heaven in the East at daybreak. (RV I.113.19; III.8.8).

Architectural fragment with relief showing winged dwarfs (or gaNa) worshipping with flower garlands, Siva Linga. Bhuteshwar, ca. 2nd cent BCE. Lingam is on a platform with wall under a pipal tree encircled by railing. (Srivastava, AK, 1999, Catalogue of Saiva sculptures in Government Museum, Mathura: 47, GMM 52.3625) The tree is a phonetic determinant of the smelter indicated by the railing around the linga: kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ lex., °ṭaka -- m. ʻ a kind of tree ʼ Kauś.Pk. kuḍa -- m. ʻ tree ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. kuṛāˊ ʻ tree ʼ, dar. kaṛék ʻ tree, oak ʼ ~ Par. kōṛ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL iii 3, 98. (CDIAL 3228).

In Atharva Veda stambha is a celestial scaffold, supporting the cosmos and material creation.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/12/skambha-sukta-atharva-veda-x-7-pair-of.html Full text of Atharva Veda ( X - 7,8) --- Stambha Suktam with translation (with variant pronunciation as skambha). See Annex A List of occurrences of gloss in Atharva Veda. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/smithy-is-temple-of-bronze-age-stambha_14.html In this text, linga is elaborated as a fiery pillar of light.

Worship of Shiva Linga by Gandharvas - Shunga Period - Bhuteshwar - ACCN 3625

वृषोत्सर्ग विधि पर टिप्पणी

वृषभ से तात्पर्य उस जीवात्मा से है जिसके सारे प्राण अशान्त अवस्था में हैं। इन प्राणों को शान्त करना है, इन्द्र बनाना है। कर्मकाण्ड में ब्राह्मणाच्छंसी ऋत्विज को वृषभ दक्षिणास्वरूप दिया जाता है। ब्राह्मणाच्छंसी ऋत्विज की प्रतिष्ठा तब होती है जब वह ब्रह्म का रस प्राप्त कर लेता है, इन्द्र बन जाता है, वैसे ही जैसे गौ अपने वत्स के लिए दुग्ध देती है।

वृषभ के मुख पर न्यास –

अहमस्मि प्रथमजा ऋतस्य पूर्वं देवेभ्यो अमृतस्य नाम। यो मा ददाति स इदेवमावदहमन्नमन्नमदन्तमद्मि॥ - सामवेद ५९४/६.२.१.९

तैत्तिरीय ब्राह्मण २.८.८.१ में इस साम का रूप इस प्रकार है –

अ॒हम॑स्मि प्रथम॒जा ऋ॒तस्य॑। पूर्वं॑ दे॒वेभ्यो॑ अ॒मृत॑स्य॒ नाभिः॑। यो मा॒ ददा॑ति॒ स इदे॒व माऽऽवाः॑। अ॒हमन्न॒मन्न॑म॒दन्त॑मद्मि॥

इस यजु का विनियोग सान्नाय्य में वेहत पशु के आलभन में पशुसूक्त में वपा की पुरोनुवाक्या हेतु किया गया है। तैत्तिरीय आरण्यक ९.१०.६/तैत्तिरीय उपनिषद(भृगुवल्ली) ३.१०.६ में इस साम की व्याख्या इस प्रकार की गई है –

अस्माल्लो॑कात्प्रे॒त्य। एतमन्नमयमात्मानमुप॑संक्र॒म्य। एतं प्राणमयमात्मानमुप॑संक्र॒म्य। एतं मनोमयमात्मानमुप॑संक्र॒म्य। एतं विज्ञानमयमात्मानमुप॑संक्र॒म्य। एतमानन्दमयमात्मानमुप॑संक्र॒म्य। इमाँल्लोकान्कामान्नीकामरूप्य॑नुसं॒चरन्। एतत्साम गायन्ना॒स्ते। हा्३वु॒ हा३वु॒ हा३वु॑। अ॒हमन्नम॒हमन्नम॒हमन्नम्। अ॒हमन्ना॒दोऽ३॒हमन्ना॒दोऽ३॒हमन्नादः। अ॒हँ श्लोक॒कृद॒हँ श्लोक॒कृद॒हँ श्लोक॒कृत्। अहमस्मि प्रथमजा ऋता३स्य॒। पूर्वं देवेभ्यो अमृतस्य ना३भा॒यि॒। यो मा ददाति स इदेव मा३ऽऽवाः॒। अ॒हमन्न॒मन्न॒॑मदन्त॒मा३द्मि॒। अ॒हं विश्वं॒ भुव॑न॒मभ्य॑भ॒वा३म्। सुव॒र्न ज्योतीः॑ ॥

सेतुसाममुखे॥ सेतुसाम्नो विशोक ऋषिस्त्रिष्टुप्छन्दः परमात्मा देवता मुखे न्यासे विनियोगः। हाउ३। सेतूँस्तर।३। दुस्त। रान्।३। दानेनादानम्।३। हाउ।३। अह मस्मिप्रथमजाऋता२३स्या३४५। हाउ।३। सेतूँस्तर।३। दुस्त। रान्। ३। अक्रोधेन क्रोधम्। २। अक्रोधेन क्रोधम्। हाउ। ३ ।पूर्वं देवेभ्यो अमृतस्य ना२३मा३४५। हाउ। ३। सेतूँस्तर। ३।दुस्त। रान् ।३। श्रद्धयाश्रद्धाम्। ३। हाउ। ३। योमाददाति सइदेवमा२३वा३४५त्। हाउ३। सेतूँस्तर। ३। दुस्त। रान्। ३। सत्येनानृतम्। ३। हाउ।३। अहमन्नमन्नमदन्तमाऽ२३द्मी३४५। आउ२हाउवा। एषागतिः।३। एतदमृतम्।३। स्वर्गछ।३। ज्योतिर्गछ।३। सेतूँस्तीर्त्त्वाचतुराऽ२३४५ः। इति मुखे॥ - अन्त्येष्टिदीपिका

वृषभ की ऊरुओं पर न्यास – ऊरुओं पर न्यास का साम यह है –

श्यावाश्वान्धीगवे इति ऊर्वोः। श्यावाश्वान्धीगवयोः श्यावाश्वान्धीगवावृषी अऩुष्टुप्छन्द ऊर्वोर्न्यासे विनियोगः। पुरो३१। जी३ती। वोअ। धा३सः। एहिया। सू। तायामादा। यि। त्नवा२यि। एहिया२। अपश्वानाँश्ना३थी३। ष्टा२३४ना। ऐहा२यि। एहिया२। सखायोदायिर्घा३जी३। ह्वा३४५यो६हायि। पुरोजितीवो४धासाः। सुताय। मादा२३या। हुम्मा२१ऽ२। त्नवे अपश्वानँ श्नथिष्टन। साखा३उवा। यो२दीघा२३जी। ह्वियाम्। औ२३होवा। हो५ई। डा। इत्यूर्व्वोः॥९॥

इस साम में एक दीर्घजिह्वा वाले श्वान का उल्लेख है जिसका हनन करना अपेक्षित है। श्वान का साधारण अर्थ कुत्ता होता है, लेकिन वैदिक भाषा में इसका अर्थ भविष्य का कल होता है। कोई भी घटना वर्तमान में घटित होनी चाहिए, भविष्य में नहीं। यह श्वान को मारने का तात्पर्य है। ऊरुओं का अधिपति मैत्रावरुण देवता-द्वय को कहा जाता है। और मैत्रावरुण धिष्ण्य के लिए कहा गया है– श्वात्रोऽसि प्रचेता। अर्थात् तुम श्वा का हनन करने वाले प्रचेता हो। यह संकेत करता है कि देह में ऊरुओं में किसी प्रकार श्वा का गुण भरा है जिसको निकाल कर ऊरु गुण को भरना है। पुरुष सूक्त में पुरुष की ऊरु से वैश्य की उत्पत्ति कही गई है। वैश्य वह है जिसके परितः धन का अस्तित्व हो, समाधि वैश्य है और धन उसकी कलाएं हैं। दूसरे शब्दों में, अब पुरुष और प्रकृति में अधिक अन्तर नहीं रह गया है। पुरुष ने प्रकृति को अपना धन बना लिया है, अब प्रकृति पुरुष को हानि नहीं, अपितु लाभ पहुंचाती है।

वृषभ के हृदय पर न्यास – हृदय पर न्यास का साम यह है –

मनोजयिदिति हृदये मनोजयीति दिश ऋषयोऽनुष्टुब् ब्रह्मा हृदये न्यासे विनियोगः। हाउ। ३।मनोजयित्। ३ । हृदयमजयित्। ३ । इन्द्रोजयित्। ३ । अहमजैषम् । ३। हाउ। ३। यद्वर्च्चोहिरण्य। स्या। यद्वा व

र्च्चोगवामु। ता। सत्यस्य ब्रह्मणोव। चाः। तेनमासँसृजाम। सायि। हाउ। ३। मनोजयित्। ३। हृदयमजयित्। ३। इन्द्रोजयित्। ३। अहमजैषम्। ३। हाउ। ३। वा। ए। मनोजयिद्धृदयमजयिदिन्द्रोजयिदहमजैषम्। ३। ए। अहँसुवर्ज्योती२३४५ः ॥ ६॥ इति हृदये।

इस साम में मन, हृदय, इन्द्र और अहम् की जय का उल्लेख है। इस संदर्भ में भागवत पुराण ८.३.१ की इस पंक्ति को उद्धृत किया जा सकता है –

एवं व्यवसितो बुद्ध्या समाधाय मनो हृदि। जजाप परमं जाप्यं प्राग्जन्मन्यनुशिक्षितम्।।

भागवत पुराण की इस पंक्ति से संकेत मिलता है कि मन का हृदय में सम्-आधान करने की आवश्यकता है। मन के विषय में महाभारत शान्तिपर्व ३११.१९ में कहा गया है कि मन इन्द्रियों से उनके अर्थों का ग्रहण करता है--

न चेन्द्रियाणि पश्यन्ति मन एवात्र पश्यति। मनस्युपरते राजन्निन्द्रियोपरमो भवेत्।। न चेन्द्रियव्युपरमे मनस्युपरमो भवेत्।

महाभारत शान्तिपर्व २५२.११ में मन को व्याकरणात्मक बनाने का निर्देश है। इस मन का आधान हृदय में स्थित अङ्गुष्ठ पुरुष में कर देना अपेक्षित है। फिर इस अङ्गुष्ठ पुरुष का आधान परम पुरुष में कर देना है। तभी सत्य दर्शन हो सकता है --

हृदयं सर्वभूतानां पर्वणाङ्गुष्ठमात्रकः। अथ ग्रसत्यनन्तो हि महात्मा विश्वमीश्वरः।। - शान्तिपर्व ३१२.१५

अथर्ववेद ६.४२.१ के मन्यु सूक्त का प्रथम मन्त्र है –

अव ज्यामिव धन्वनो मन्युं तनोमि ते हृदः ।

यथा संमनसो भूत्वा सखायाविव सचावहै ।।

अर्थात् मैं तेरे हृदय से मन्यु का अवतनन इस प्रकार करता हूं जैसे धनुष पर से ज्या का अवरोपण किया जाता है । ऐसा करने से हम दोनों एक मन हो सकेंगे और सखाओं की भांति व्यवहार कर सकेंगे । इस मन्त्र से संकेत मिलता है कि हृदय में स्थित प्राण उन प्राणों में से हैं जिन पर मन का आरोपण करके, उन्हें मन द्वारा सममिति प्रदान करके मन्यु बनाया जा सकता है । लेकिन इस मन्यु को भी हटाना है

वृषभ की गुदा पर न्यास –

आ तू न॑ इन्द्र क्षु॒मन्तं॑ चि॒त्रं ग्रा॒भं सं गृ॑भाय। म॒हा॒ह॒स्ती दक्षि॑णेन।। - ऋ. ८.८१.१

इस ऋचा का ऋषि कुसीदी काण्व है। कुसीद ब्याज को कहते हैं। कुसीदी से संकेत मिलता है कि यह ऋणात्मक स्थिति से धनात्मक स्थिति को जाने की अवस्था है। ऋचा का अर्थ सायण भाष्य के अनुसार यह है कि हे इन्द्र, शब्दायमान(क्षुमन्तं) हमारे लिए तू चित्र धन(ग्राभ) लेकर आ। तू दक्षिण द्वारा महाहस्ती है। क्षु का वास्तविक अर्थ समझने की आवश्यकता है। ह तथा क्ष का न्यास मूर्द्धा में किया जाता है। क्षुधा की स्थिति भी क्षुमन्त हो सकती है। अथवा यह अनुमान लगाया जा सकता है कि चूंकि मूलाधार पर ऊष्माण वर्णों श-ष-स का अस्तित्व होता है, अतः ऊष्णाण वर्णों की कोई विकसित अवस्था क्ष है। अग्नि पुराण ३४८ में क्ष वर्ण को क्षत्र, अक्षर, क्षेत्र, क्षेत्रपाल आदि से सम्बद्ध किया गया है।

गुदा पर न्यास का साम यह है –

आतूनआ इति गुदे। आतूनइति वर्गस्य गौरीवित्यपालवैणवावृषी गायत्री छन्दो गुदे न्यासे विनियोगः। आतूनआ। द्रक्षुमाऽ२३न्ताम्। चायित्रंग्राभा२३ँहाइ। संगृ२भाया। महाहस्ती२३४हाइ। दक्षा२यिणायिना। महा२३। हा२स्ता२३४औहोवा। दक्षिणे३नाऽ२३४५॥१६॥ आतूनइन्द्रक्षुमाताम्। चित्राऽ२ग्रा२३४भाम्। संगृभा२३४या। मा२३हा३। हा२स्ता२३४औहोवा। दक्षिणेनाऽ२३३५॥१७॥ आतूनईं। द्रक्षुमा६न्ताम्।

चित्रङ्ग्राभँसङ्गृभा२याचित्रङ्ग्राभँसम्। गृ। औ३होयि। भा२३४या। ऐहोई। महाहस्तीदक्षाऽ२३होइ। औहो। वाहो२३४वा। णाऽ५यिनो६हाइ॥१८॥ आतूनइन्द्रक्षुमा६न्ताम्। चित्रं ग्राभँसङ्गृभाया। चित्रंग्राभँसम्।गृऽ२३।ई२३४हा। भा२३४या। ऐहोइ। महाहस्तीदक्षाऽ२३होइ। औहो। वाहो२३४वा। णा५यिनो६हाइ॥१९॥ इदि गुदे।

आर्षेय ब्राह्मण २.६.४ में उपरोक्त सामों का विवेचन किया गया है। आ तू न इन्द्र क्षुमन्तम्(साम संख्या १६७ अथवा पूर्वार्चिक २.२.३.३) से चार साम प्रकट हुए हैं जिनमें प्रथम दो की संज्ञा गौरीवित है और अन्तिम दो की अपाला-वैणव या आकूपार या पारवव है। इन चारों ही सामों का विनियोग वृषभ की गुदा हेतु किया गया है। जैमिनीय ब्राह्मण १.२२० में इस साम के वेणु तथा अपाला, इन दो ऋषियों का उल्लेख मिलता है और इन दो ऋषियों के संदर्भ में इस साम के महत्त्व का वर्णन किया गया है। वेणु ने ब्रह्मवर्चस की प्राप्ति की और अपाला ने उर्वरता तथा सूर्यत्वचा प्राप्त की। ताण्ड्य ब्राह्मण ९.२.१३ में अकूपार अङ्गिरस के संदर्भ में इस साम का कथन है जो अपाला के समान ही है। ऊहागानम् में आ तू न इन्द्र क्षुमन्तम् ऋचा का जो साम उपलब्ध है, वह भी आकूपारम् नाम से ख्यात है। लेकिन इस साम का विस्तार वर्तमान साम से भिन्न है।

प्रश्न यह उठता है कि उपरोक्त साम के ऋषि के रूप में अपाला का आख्यान करने से कौन सा उद्देश्य सिद्ध किया गया है। ऋग्वेद ८.९१ सूक्त अपाला आत्रेयी ऋषिका का है तथा इस सूक्त की अन्तिम ऋचा इस प्रकार है –

खे रथ॑स्य॒ खेऽन॑सः॒ खे यु॒गस्य॑ शतक्रतो। अ॒पा॒लामि॑न्द्र त्रिष्पू॒त्व्यकृ॑णोः॒ सूर्य॑त्वचम्।।

इस ऋचा से जुडे आख्यान के अनुसार इन्द्र ने अपाला को रथ के छिद्र से निकाल कर शुद्ध किया। जो मल निकला, वह गोधा बना। फिर अनः के छिद्र से बाहर निकाला। वह कृकलासी बना। फिर युग के छिद्र से बाहर निकाला। वह संश्लिष्टिका बना। तब जाकर अपाला ने कल्याणतम रूप प्राप्त किया। इन छिद्रों का उल्लेख करने की आवश्यकता क्यों पडी? हो सकता है कि गुदा अङ्ग में वृक्कों(kidney) का समावेश भी कर लिया गया हो। वृक्कों के माध्यम से ही रक्त के छनने का कार्य सम्पन्न होता है। और जिस प्रकार सूक्त में तीन प्रकार के छिद्रों का उल्लेख है, उससे मिलता-जुलता उल्लेख शतपथ ब्राह्मण ३.८.४.३ में भी मिलता है जहां पशु के प्राण की शिवता स्थापित करने के लिए गुदा को त्रेधा विभक्त किया गया है। गुदा के एक भाग को उपयाम(उपयड्)? में, एक भाग को जुहू में और एक भाग को उपभृत पात्र में ग्रहण करके आहुति दी जाती है।

साम के वेणु ऋषि होने के उल्लेख के संदर्भ में यह कल्पना की जा सकती है कि गुदा की कोई स्थिति ऐसी भी है जहां यह वेणु बन कर शब्द करती है।

गुदा को मृत्यु, विसर्ग, राहु का स्थान कहा गया है। यह हमारी देह में गुदा की प्राकृतिक स्थिति है जिसके द्वारा मल का विसर्जन होता है। जैमिनीय ब्राह्मण २.२६७ में गुदा से अहियों व अजगरों की उत्पत्ति का उल्लेख है। यह स्वाभाविक है कि गुदा से विसर्जित मल का विष अहि-अजगर पीते रहते हैं। लेकिन एक उस स्थिति की कल्पना की जा सकती है जिसमें शरीर इतना पुष्ट हो गया है कि उसको अब बाहर से भोजन की आवश्यकता नहीं पडती। उस स्थिति में हमारे वर्तमान अंग किस प्रकार काम करेंगे? काशकृत्स्न धातुव्याख्यानम् में गुर्द धातु क्रीडने, नर्तने अर्थों में दी गई है। जैमिनीय ब्राह्मण ३.१६८ व ३.१७१ में एक गूर्द साम(त्वं नो अग्ने अन्तम उत त्राता शिवो भवा वरूथ्यः इति) का उल्लेख मिलता है जिसे अन्नाद्य की प्राप्ति कराने वाला साम कहा गया है। यह अन्नाद्य कोई आनन्द की स्थिति हो सकती है। इस साम का उपयोग प्राणों को एकत्रित करने में भी कहा गया है। लेकिन वर्तमान संदर्भ में तो इस साम का उल्लेख है नहीं। ऊपरिलिखित साम में तो किसी महाहस्ती का उल्लेख है। यह अन्वेषणीय है कि क्या इस साम में हस्ती के शुण्डाग्र की उपमा गुदा से दी गई है। हस्ती अपनी शुण्डाग्र का प्रयोग अपने मुख तक भोजन पहुंचाने के लिए करता है। उसकी कर्मेन्द्रिय शुण्ड का उदय मस्तिष्क से होता है, जबकि हमारी देह में मस्तिष्क और हृदय के मध्य से होता है। शतपथ ब्राह्मण १०.६.४.१ में मेध्य अश्व की गुदा को सिन्धवः कहा गया है। तैत्तिरीय ब्राह्मण २.६.४.३ में कौकिल सौत्रामणी याग के संदर्भ में गुदा की तुलना सुदुघा धेनु जैसे पात्रों से की गई है। पुराणों में गौ के गोमय में लक्ष्मी का स्थान कहा गया है।

स्वाहा। इदं सोमाय न मम। शुक्रं ते अन्यद्यजतं ते अन्यद्विषुरूपे अहनी द्यौरिवासि। विश्वाहि माया अवसि स्वधावन् भद्रा ते पूषन्निह रातिरस्तु स्वाहा। इदं पूष्णे न मम॥ इन्द्रा पर्वता बृहता रथेन वामी ऋषआवहतँ सुवीराः। वीतँ हव्यान्यध्वरेषु देवा वर्द्धेथां गीर्भिरिडया मदन्ता स्वाहा। इदं इन्द्राय न नम॥ आवो राजानमध्वरस्य रुद्रँ होतारँ सत्ययजँ रोदस्योः। अग्निं पुरातनयित्नोरचित्ताद्धिरण्यरूपमवसे कृणुध्वं स्वाहा। इदं रुद्राय न मम। ततश्चरुणा स्विष्टकृद्धोमः व्याहृतित्रयहोमः। तूष्णीं समिदाधानम् अनुपर्य्युक्षणमुदकाञ्चलिसेचनं यज्ञवास्तुकरणं वस्वाहुतिः। ततश्चतसृभिर्वत्सतरीभिः सहितं वृषभमग्निसमीपमानीय प्राङ्मुखं संस्थाप्य न्यासं कुर्यात्। यथा वृषस्य मस्तके गायत्रीं न्यसेत्। गायत्र्या विश्वामित्रो गायत्री सविता वृषस्य मस्तके न्यासे विनियोगः। ॐ तत्सवितुर्वरेणियोम्। भार्गोदेवस्य धीमाही२। धियोयोनः प्रचो१२१२। हुम्। आ२। दायो। आ२३४५। नमस्तौ इति ललाटे। नमस्तौ इति अग्निर्गायत्र्यग्निर्ललाटे न्यासे विनियोगः नमस्तौ। होग्नायि। ओजसा३यि।/

गृणा२न्ता२३४यिदे। वा कृष्टया२ः। अमाये३ः। आ२मा२३४औहोवा। त्रमर्द्दया२३४५॥१॥ रौरवयौधाजये चक्षुषोः॥ रैरलयौधाजययोः साम्नोरग्नींद्रावृषी बृहतीछन्दः सोमो देवता चक्षुषोर्न्यासे विनियोगः। रौरवम्॥ पुनानस्सोमा३धाराऽ२३४या। आपोवसानो अर्षस्यारत्नधायोनिमृतस्य सा२यिदसायि। ओहा३उवा। उत्सोदेवोहिराऽ२३हायि। ओहा३उवा। ण्यया। औ३होवा॥१॥ ऊत्सोदेवोहा३यिरण्याऽ२३४याः। ऊत्सोदेवोहिरण्ययोदुहान ऊधर्द्दिविययम्मधूऽ२प्रियाम्। ओहा३उवा। प्रत्नं सधस्थमाऽ२३हायि। ओहा३उवा। सदात्। औ२३होवा॥२॥ प्रत्नंसधस्था३मासाऽ२३४दात्। प्रात्नंसधस्थमासददापृछ्यन्धरुणम्वाजिया२र्षसायि। ओहा३उवा। नृभिर्द्धौतोविचाऽ२३हायि। ओहा३उवा। क्षणा। औ३होवा। होऽ५यि। डा॥३॥ इति रौरवम्। दक्षिणनेत्रे यौधाजयम्। पुना३१। ना३स्सो। म । धारा२३४या। आपो३। वसा२। न आ३४५। षा२३४शी। आरात्नधाः। यो। निमृताऽ२।/

स्या३४५यि। दा३४२सी। उत्सा२ः। दायिवो२। हिरा३४५। ण्या२३४याः॥१॥ उत्सो३१। दे३वो। हि। रण्या२३४याः। ऊत्सो३। दायिवो२।हिरा३४५। ण्या२३४याः। दुहान ऊ। धः। दिविया२म्। मधू३४५। प्री२३४याम्। प्रत्ना२म्। साधा२। स्थमा३४५। सा२३४दात्॥२॥प्रत्ना३१म्। सा३ध। स्थम्। आसा२३४दात्। प्रात्ना३म्। सधा२। स्थमा३४५। सा२३४दात्। आपार्छियाम्। ध। रुणम्वा२। जिया३४५। षा२३४सी। नृभा२यिः। धौतो२। विचा३४५। क्षा२३४णाः॥३॥ इति यौधाजयं वामनेत्रे। बृहद्रथन्तरे कर्णयोः। बृहद्रथन्तरयोर्भरद्वाजवसिष्ठावृषी बृहतीछन्द इन्द्रो देवता कर्णयोर्न्यासे विनियोगः॥ आभित्वाशूरनोनुमोवा। आदुग्धाइवधेनव ईशानमस्य जगतः। सुवा२३र्दृशाम्। आइशानमा२३यिन्द्रा३। तास्थू२३४षा। ओवा६। हाउवा। अस्॥ रथन्तरम्॥ वामकर्णे बृहत्साम्। औहोयित्वामिद्धिहवामहा३ए। सातौवाजा। स्याकारा२३४वाः। तुवा३४। औहोवा। वृत्रायिषुवायि।/

द्रासा३१त्। पतिन्ना२३४राः त्वां काष्ठा३४। औहोवा। सू२अर्वा२३४। ताः। उहुवा६हाउ। वा हस्। बृहत्साम दक्षिणकर्णे॥३॥ इति कर्णयोः॥ सेतुसाममुखे॥ सेतुसाम्नो विशोक ऋषिस्त्रिष्टुप्छन्दः परमात्मा देवता मुखे न्यासे विनियोगः। हाउ३। सेतूँस्तर।३। दुस्त। रान्।३। दानेनादानम्।३। हाउ।३। अह मस्मिप्रथमजाऋता२३स्या३४५। हाउ।३। सेतूँस्तर।३। दुस्त।रान्। ३। अक्रोधेन क्रोधम्। २। अक्रोधेन क्रोधम्। हाउ। ३ ।पूर्वं देवेभ्यो अमृतस्य ना२३मा३४५। हाउ। ३। सेतूँस्तर। ३।दुस्त। रान् ।३। श्रद्धयाश्रद्धाम्। ३। हाउ। ३। योमाददाति सइदेवमा२३वा३४५त्। हाउ३। सेतूँस्तर। ३। दुस्त। रान्। ३। सत्येनानृतम्। ३। हाउ।३। अहमन्नमन्नमदन्तमाऽ२३द्मी३४५। आउ२हाउवा। एषागतिः।३। एतदमृतम्।३। स्वर्गछ।३। ज्योतिर्गछ।३। सेतूँस्तीर्त्त्वाचतुराऽ२३४५ः। इति मुखे॥ देवव्रतानि त्रीणि कण्ठे। देवव्रतानां देवाउत्कृती रुद्रः कण्ठे न्यासे/

विनियोगः। अधिप। तायि। मित्रप तायि। क्षत्रप। तायि। स्वप्पतायि धनपता२यि। ना२माः। मन्न्युना वृत्रहा सूर्य्येण स्वराड्यज्ञेन मघवा दक्षिणास्य प्रियातनू राज्ञा विशं दाधार। वृषभस्त्वष्टा वृत्रेण शचीपतिरन्नेन गयःपृथिव्यासृणिकोग्निना विश्वं भूतम। भ्य भवो वायुना विश्वाः प्रजाअभ्यपवथा वषट्कारेणार्द्धभाक्सोमेन सोमपास्समित्या परमेष्ठी। ये देवा देवाः। दिवि षदः। स्थ तेभ्यो वो देवा देवेभ्यो नमः। ये देवादेवाः। अन्तरिक्षसदः। स्थ तेभ्यो वो देवा देवेभ्यो नमः। ये देवा देवाः। पृथिवीषदः। स्थ तेभ्यो वो देवा देवेभ्यो नमः। ये देवादेवाः। अप्सुषदः। स्थ तेभ्यो वो देवा देवेभ्यो नमः। ये देवादेवाः। दिक्षुसदः। स्थ तेभ्यो वो देवा देवेभ्यो नमः। ये देवादेवाः। आशासदः। स्थ तेभ्यो वो देवा देवेभ्यो नमः। अव ज्यामिव धन्वनो वि ते मन्न्युन्नयामसि मृड तान्न इह अस्मभ्यम्। इडाऽ२३भा। य इदं विश्वं भूतम्। युयो३।/

आऊ। वाऽ२३। ना२३४माः॥६॥ अधिप। तायि। मित्रप। तायि। क्षत्रप। तायि। स्वप्प तायि। धनपता२यि। ना२माः। नम उततिभ्यश्चोत्तन्वानेभ्यश्च नमो निषङ्गिभ्यश्चोपवीतिभ्यश्च नमोस्यद्भ्यश्चप्र। तिदधानेभ्यश्च नमः प्रविध्यद्भ्यश्च प्रव्याधिभ्यश्च नमः त्सरद्भ्यश्च त्सारिभ्यश्च नमः श्रि। तेभ्यश्च श्रायिभ्यश्च नमस्तिष्ठद्भ्यश्चोपतिष्ठद्भ्यश्च नमो यते च वियते च नमः पथे च विपथाय च। अव ज्यामिव धन्वनो विते मन्न्युन्नयामसि मृडतान्न इह अस्मभ्यम्। इडा२३भा। य इदं विश्वं भूतम्। युयो३। आउ। वाऽ२३। ना२३४माः॥७॥ अधिप। तायि। मित्रप। तायि। क्षत्रप. तायि। स्वः पतायि। धनपता२यि। ना२माः। नमोन्नाय नमोन्नपतयएकाक्षाय चावपन्नादाय च नमोनमः। रुद्राय तीरसदे नमः स्थिराय स्थिरधन्वने नमः प्रतिपदाय च पटरिणे च नमस्त्रियम्बकाय च क। पर्दिने च नम आश्रायेभ्यश्च प्रत्याश्रायेभ्यश्च नमः/

क्रव्येभ्यश्च विरिंफेभ्यश्च नमस्संवृते च विवृते च। अव ज्यामिव धन्वनो विते मन्न्युन्नयामसि मृडतान्न इह अस्मभ्यम्। इडाऽ२३भा। य इदं विश्वम्भूतं। युयो३। आउ। वाऽ२३। ना२३४माः॥३॥ इति कण्ठे। वामदेव्यं लाङ्गले। वामदेव्यस्य वामदेवो गायत्रीन्द्रो लाङ्गूले न्यासे विनियोगः।काऽ५या। नश्चाऽ३यित्रा३आभुवात्। ऊ। तीसदावृधस्स। खा। औ३होहायि। कयाऽ२३शचायि। ष्ठयौहो३। हुम्मा२। वाऽ२र्त्तो३ऽ५हायि॥१॥ का५स्त्वा। सत्योऽ३मा३दानाम्। मा। हिष्ठोमात्सादन्ध। सा। औ३होहायि। दृढाऽ२३चिदा। रुजौहो३। हुम्मा२। वाऽ२सो३ऽ५हायि॥२॥ आऽ५भी। षुणा३स्सा३खीनाम्। आ। विताजरायितृ। णाम्। औऽ२३होहायि। शताऽ२३म्भवा। सियौहो३। हुम्मा२। ताऽ२यो३ऽ५हायि॥३॥ इति लाङ्गूले। व्रतपक्षौ स्कन्धयोः। व्रतपक्षसाम्नोः प्रजापतिस्त्रिष्टुबिन्द्रः स्कन्धयोन्यासे विनियोगः॥ हाउ३। हँ हँ हँ हँ।३।हाउ३। इन्द्रन्नरो। ने३मधि। ताहव/

न्तायि। यत्पारियाः। युनज। तायिधियस्ताः। शूरोनृषा ता३श्रव। सश्चकामायि। आगोमतायि। व्रजेभ। जातुवन्नाः। हाउ३। हँहँहँहँ। ३। हाउ३। वा। ई२३४५॥ हाउ३ । इहा। हँहँहँ। ३। हाउ३। इन्द्रन्नरो। ने३मधि। ताहवन्तायि। यत्पारियाः। युनज। तायिधियस्ताः। शूरोनृषा। ता३श्रव। सश्चकामायि। आगोमतायि। व्रजेभ। जातुवन्नाः। हाउ३। इहा। हँहँहँ। ३। हाउ३। वा३। ई२३४५॥ इति स्कन्धयोः॥ ओग्नायीति उरुमध्ये. ओग्नायीति गौतमो गायत्र्यग्निः ऊरुमध्ये न्यासे विनियोगः। ओग्नाई। आयाहि३वियितोया२यि। तोया२यि गृणानोह। व्यदातोया२यि। तोया२यि। नायिहोतासा२३। तस्२यिवा२३४औहोवा। ही२३४षी॥ इति ऊरुमध्ये॥ मनोजयिदिति हृदये मनोजयीति दिश ऋषयोऽनुष्टुब् ब्रह्मा हृदये न्यासे विनियोगः। हाउ। ३।मनोजयित्। ३ । हृदयमजयित्। ३ । इन्द्रोजयित्। ३ । अहमजैषम् । ३। हाउ। ३। यद्वर्च्चोहिरण्य। स्या। यद्वा व/

र्च्चोगवामु। ता। सत्यस्य ब्रह्मणोव। चाः। तेनमासँसृजाम। सायि। हाउ। ३। मनोजयित्। ३। हृदयमजयित्। ३। इन्द्रोजयित्। ३। अहमजैषम्। ३। हाउ। ३। वा। ए। मनोजयतिद्धृदयमजयिदिन्द्रोजयिदहमजैषम्। ३। ए। अहँसुवर्ज्योती२३४५ः ॥ ६॥ इति हृदये। आजुहोता इति नाभौ। आजुहोतेति श्यावाश्वस्त्रिष्टुबग्निर्नाभौ न्यासे विनियोगः। आजुहोता। हविषामर्ज्जया२ध्वा उवाऽ२।निहोतारं गृहपति दधा२यिध्वा उवा२३४। इडा३४स्पदाइ। नमसारातहाव्या२म्। सापर्य्यता। याजतम्पाऽ२३। स्तियोवा। आ५नो६हाइ॥ ३४॥ इति नाभौ। तद्वौहोवा इत्यादि चत्वारि जान्वोः॥ तद्वोगा इति वर्गस्य रुद्रो गयत्रो जान्वोर्न्यासे विनियोगः। तद्वौहोवा। गाया२। सुतायिसा२३४चा। पुरुहूता। यसात्वा१ना२यि। संयत्। हा। औ३होइ। गा२३४वाइ। ना२शा२३४औहोवा। ए३। किनेऽ२३४५॥१॥ तद्वोगाया। सुताइसचा३। पुरूऽ२३हूता३४। हाहो३। यासत्वा२३४/

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

December 31, 2015

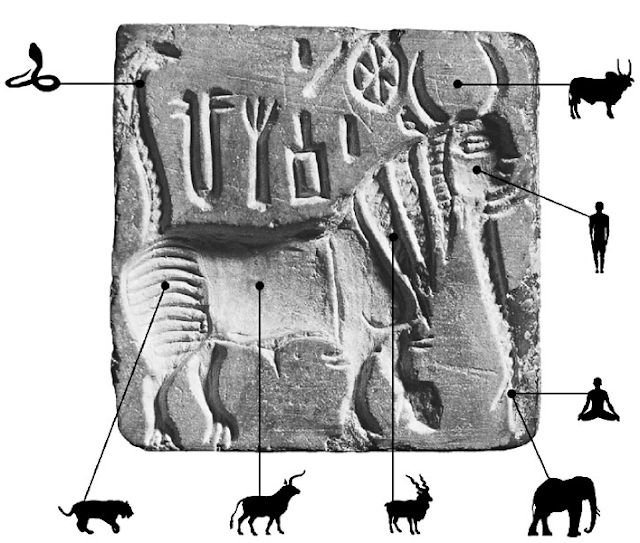

Seal m0304

Seal m0304 the new station at Bhalukpong awaits the only train from Dekargaon, the rail head for Tezpur. (Express Photo by: Dasarath Deka)

the new station at Bhalukpong awaits the only train from Dekargaon, the rail head for Tezpur. (Express Photo by: Dasarath Deka) Station master B C Goswami at work. (Express Photo by: Dasarath Deka)

Station master B C Goswami at work. (Express Photo by: Dasarath Deka) Nilima Basumatary sets up her stall at the station. (Express Photo by: Dasarath Deka)

Nilima Basumatary sets up her stall at the station. (Express Photo by: Dasarath Deka)

Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph.

Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph.

![[prasati%2520mulawarman%255B3%255D.jpg]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-L7CZvk8_Iys/ToIb1RXc2QI/AAAAAAAAAR0/aPzxQNQq0Tg/s1600/prasati%252520mulawarman%25255B3%25255D.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

PMO India

PMO India  Rajnath Singh

Rajnath Singh

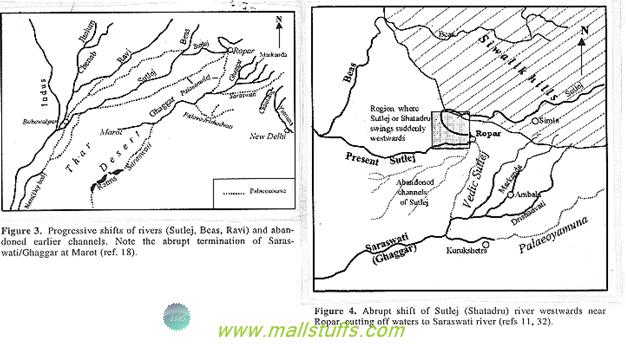

Map showing sites Kalibangan, Ganweriwala (not far from Binjor)

Map showing sites Kalibangan, Ganweriwala (not far from Binjor)

Clustering of the sites towards Ganga-Yamuna doab 3000 BP.

Clustering of the sites towards Ganga-Yamuna doab 3000 BP.

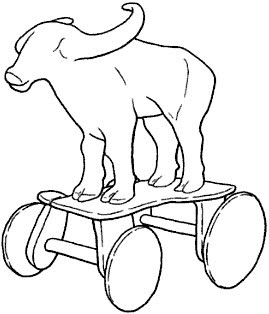

Toy animals made for the Pola festival especially celebrated by the Dhanoje Kunbis. (Bemrose, Colo. Derby - Russell, Robert Vane (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: volume IV. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. London: Macmillan and Co., limited. p. 40).

Toy animals made for the Pola festival especially celebrated by the Dhanoje Kunbis. (Bemrose, Colo. Derby - Russell, Robert Vane (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: volume IV. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. London: Macmillan and Co., limited. p. 40).

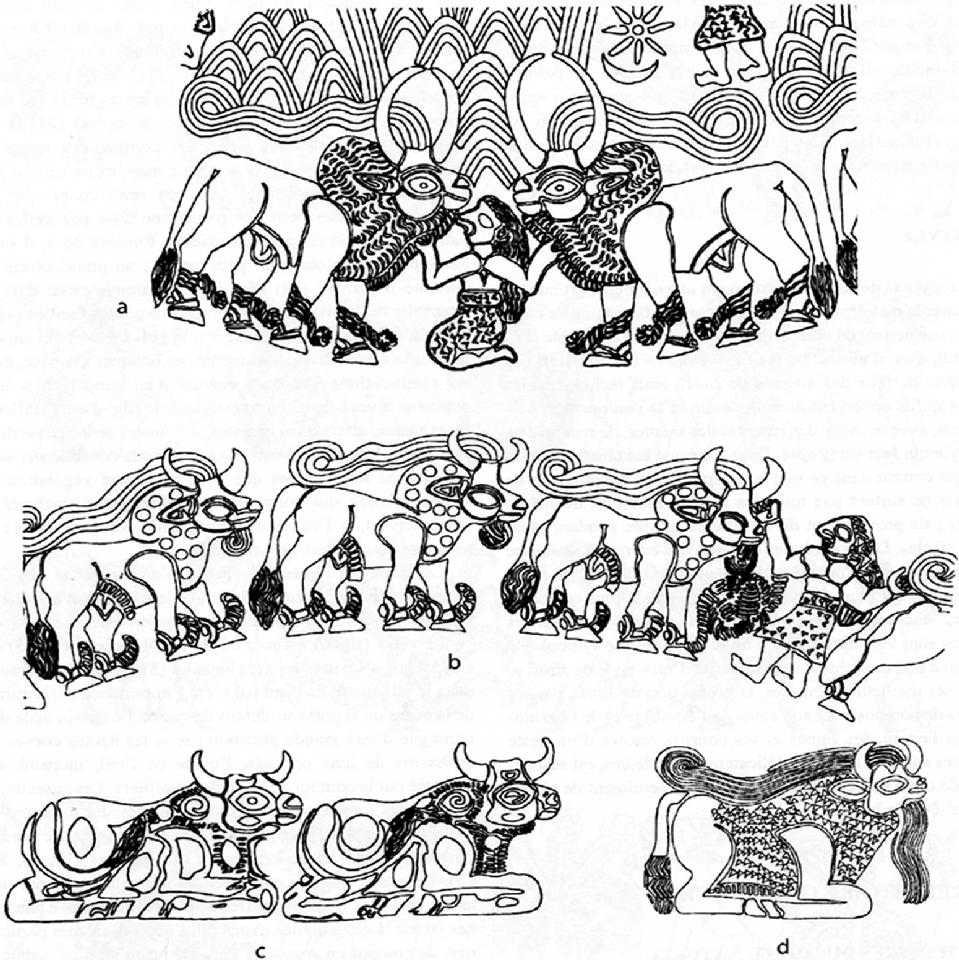

Slippainted cylindrical jar. Kulli.

Slippainted cylindrical jar. Kulli.  Indus Valley Terracotta Vessel - LO.1329

Indus Valley Terracotta Vessel - LO.1329

S Gurumurthy

S Gurumurthy

inShare