Indus Script decipherment results in a Meluhha lexis; a select, short vocabulary list is indicated in this monograph; a comprehensive vocabulary list will relate to ca. 7000 inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora all of which relate to only one category: metalwork catalogues. Such a comprehensive lexis of ancient Indian lingua franca, will span Meluhha (Mleccha), Chandas and all languages of Indian sprachbund.

The lexis relates to semantics of metalwork 1. words and expressions of Bronze Age; and 2. words which signify hieroglyph-multiplexes which are homonyms, rebus catalogues of such metalwork.

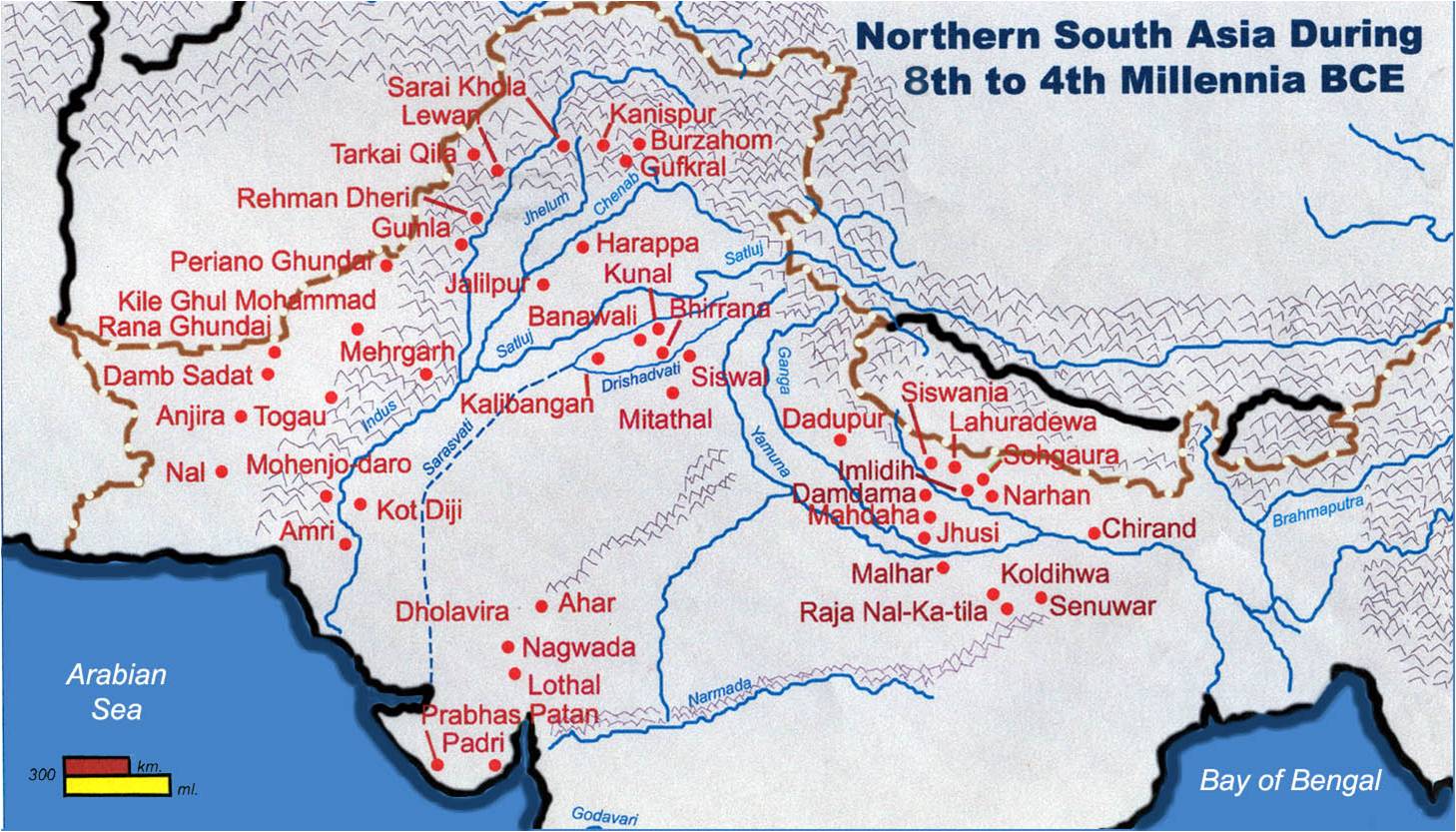

The authors of these catalogues were Bhāratam Janam, 'metalcaster folk' of Bronze Age, Sarasvati's children who toiled on the banks of Sapta Sindhu 'seven rivers' and laid the foundations of the Hindu civilization, dateable from ca. 8th millennium BCE.

The earliest evidence of writing is on a Harappa potsherd with Indus Script dated to ca. 3300 BCE.

![Image result for potsherd harp]() Harappa. Potsherd. Indus writing (HARP) dated to ca. 3500 BCE. tagaraka 'tabernae montana' rebus: tagara 'tin'. kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

Harappa. Potsherd. Indus writing (HARP) dated to ca. 3500 BCE. tagaraka 'tabernae montana' rebus: tagara 'tin'. kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

Introduction: Adapted from Sri Ramakrishna's ferryman and scholar story

This is an adaptation of an encounter which Sri Ramakrishna used to narrate which was called 'The story of a ferryman and a scholar’. This narrative is extended by a reference to Indus Script hieroglyphs signifying metalwork catalogues on a boat showing the ferryman as a seafaring merchant carrying supercargo of metalwork ingots and hard metal alloy implements.

A scholar of grammar undertook a journey to cross a river. He hired a boat which ferried passengers across the river.

The scholar asked the ferryman, if he knew grammar and language rules.

The ferryman said, "No, I don't."

The scholar expressed his anguish in Chandas, ‘prosody’: “Ferryman, dear mleccha, you have wasted your life.”

Suddenly the boat started tossing as water levels rose in the river. The ferryman asked the scholar, “Pandita, can you swim?"

"No!" panicked the scholar, lost for words since he did not know the river and hydrology rules.

“Arya, noble atman, you have wasted half of your life," the ferryman felt sorry as he said these words in Mleccha, ’parole’ perfectly intelligible to the scholar, and continued a refrain from the ferryman’s song "Elo! Elelo! He’lava, he’lavo !! You have wasted your whole life, the boat will capsize soon."

While the scholar got the message, he was baffled by the words used in the refrain and wondered about the appropriateness of Indo-European linguistics to deal with survival issues, etymology of and characteristic mispronunciations in the ungrammatical expression, 'elo, elelo, he'lava, he'lavo'. The scholar lapsed into a meditative mood in kamaDha 'penance' with the confidence that the ferryman would somehow save him from drowning, after the boat capsized.

This narrative of the scholar and ferryman is in nuce, in a nutshell, the Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam, the narrative of Hindu civilization which dates back to ca. 8th millennium BCE.

The expression, Bhāratam Janam occurs in Rigveda (RV 3.53.12). The expression is traceable to the following etyma: भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c.भरतखंड (p. 603) [ bharatakhaṇḍa ] n (S) भरतवर्ष n S A division of the globe,--that from the Himálaya range to the ocean, India.भरतशास्त्र (p. 603) [ bharataśāstra ] n S The shástra of the drama, the authoritative treatise upon dramatic composition and representation. 2 Used freely in the sense of The laws of the drama and of scenic exhibition.भरताचें भांडें (p. 603) [ bharatācē mbhāṇḍēṃ ] n A vessel made of the metal भरत. 2 See भरिताचें भांडें.भरती (p. 603) [ bharatī ] a Composed of the metal भरत. A hieroglyph to signify भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] is: barad, balad 'ox'.

One side of a molded tablet m 492 Mohenjo-daro (DK 8120, NMI 151. National Museum, Delhi. A person places his foot on the horns of a buffalo while spearing it in front of a cobra hood.

Hieroglyph: kolsa = to kick the foot forward, the foot to come into contact with anything when walking or running; kolsa pasirkedan = I kicked it over (Santali.lex.)mēṛsa = v.a. toss, kick with the foot, hit with the tail (Santali)

kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pancaloha’ (Ta.) •kolhe (iron-smelter; kolhuyo, jackal) kol, kollan-, kollar = blacksmith (Ta.lex.)•kol‘to kill’ (Ta.)•sal ‘bos gaurus’, bison; rebus: sal ‘workshop’ (Santali)me~ṛhe~t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron; kolhe m. iron manufactured by the Kolhes (Santali); meṛed (Mun.d.ari); meḍ (Ho.)(Santali.Bodding)

nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

Hieroglyph: rã̄go ʻ buffalo bull ʼ

Rebus: Pk. raṅga 'tin' P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼOr. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼraṅgaada -- m. ʻ borax ʼ lex.Kho. (Lor.) ruṅ ʻ saline ground with white efflorescence, salt in earth ʼ *raṅgapattra ʻ tinfoil ʼ. [raṅga -- 3, páttra -- ]B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.

paTa 'hood of serpent' Rebus: padanu 'sharpness of weapon' (Telugu)

Hieroglyph: kunta1 ʻ spear ʼ. 2. *kōnta -- . [Perh. ← Gk. konto/s ʻ spear ʼ EWA i 229]1. Pk. kuṁta -- m. ʻ spear ʼ; S. kundu m. ʻ spike of a top ʼ, °dī f. ʻ spike at the bottom of a stick ʼ, °diṛī, °dirī f. ʻ spike of a spear or stick ʼ; Si. kutu ʻ lance ʼ.

2. Pa. konta -- m. ʻ standard ʼ; Pk. koṁta -- m. ʻ spear ʼ; H. kõt m. (f.?) ʻ spear, dart ʼ; -- Si. kota ʻ spear, spire, standard ʼ perh. ← Pa.(CDIAL 3289)

Rebus: kuṇṭha munda (loha) 'hard iron (native metal)'

Allograph: कुंठणें [ kuṇṭhaṇēṃ ] v i (कुंठ S) To be stopped, detained, obstructed, arrested in progress (Marathi)

![]() Tablet. Crocodile above. Peson kicking and spearing a bison, near a seated,horned (with twig) person.Harappa. Harappa Museum, H95-2486 Meadow and Kenoyer 1997

Tablet. Crocodile above. Peson kicking and spearing a bison, near a seated,horned (with twig) person.Harappa. Harappa Museum, H95-2486 Meadow and Kenoyer 1997karA 'crocodile' Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

kamaDha 'penance' (Prakritam) Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'

kUtI 'twigs' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

muh 'face' Rebus: muhe 'ingot' (Santali)

See:

Meluhha is the spoken form of language and glosses are present in almost all languages of Indian sprachbund "A sprachbund (/ˈsprɑːkbʊnd/; German: [ˈʃpʁaːxbʊnt], "federation of languages") – also known as a linguistic area, area of linguistic convergence, diffusion area or language crossroads – is a group of languages that have common features resulting from geographical proximity and language contact." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sprachbund

Ferdinand de Saussure, presents Langue (French word meaning 'language') and Parole (French word meaning 'speech'). (de Saussure, F. (1986). Course in general linguistics (3rd ed.). (R. Harris, Trans.). Chicago: Open Court Publishing Company. (Original work published 1972). p. 9-10, 15.)

Langue is abstract, a system of rules and conventions of a signifying system; independent of, and pre-exists, individual users. Parole is an individual phenomenon, a series of speech acts or utterances by a speaker.

In such a framework, chandas is langue, while mleccha is parole.

√म्लेछ् | mlech | speaking indistinctly, pronouncing incorrectly / avyakta śabda | | |

| | speaking confusedly, barbarously / avyaktāvāc | | |

| | cutting, smearing, anointing, accumulating / chedana. A phonetic variant and semantic expansion of the utterance mleccha is milakkha 'mleccha speaker'(Pali). The word mleccha also refers to 'copper' as in mleccha mukha'copper ingot' (Samskritam). An expression milakkhu rajanam signifies 'copper red' (Pali). |

The word Meluhha is a variant pronunciation of Pali milakkha. The word Meluhha is attested in an Akkadian cuneiform inscription on a cylinder seal of Shu-Ilishu.

Shu-Ilishu cylinder seal authenticates Meluhha merchant dealing in copper and tin

![]()

The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris. Akkadian. Cylinder seal Impression. Inscription records that it belongs to ‘S’u-ilis’u, Meluhha interpreter’, i.e., translator of the Meluhhan language (EME.BAL.ME.LUH.HA.KI) The Meluhhan being introduced carries an goat on his arm. Musee du Louvre. Ao 22 310, Collection De Clercq 3rd millennium BCE. The Meluhhan is accompanied by a lady carrying a kamaṇḍalu. Since he needed an interpreter, it is reasonably inferred that Meluhhan did not speak Akkadian.Antelope carried by the Meluhhan is a hieroglyph: mlekh ‘goat’ (Br.); mr̤eka (Te.); mēṭam (Ta.); meṣam (Skt.) rebus: milakkhu 'copper'. Thus, the goat conveys the message that the carrier is a Meluhha speaker/copper merchant. A phonetic determinant. mrr̤eka, mlekh ‘goat’; Rebus: melukkha Br. mēḻẖ ‘goat’. Te. mr̤eka (DEDR 5087) meluh.h.a. The kamaṇḍalu carrie by the lady is ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin'. Thus, the message on the cylinder seal is a metalwork catalogue signifying an Akkadian trader's transaction with a Meluhhan engaged in copper and tin metalwork.

![]() The crucible is the center-piece hieroglyph on the cylinder seal. Hieroglyph: kuThari 'crucible' Rebus: kuThari'storekeeper

The crucible is the center-piece hieroglyph on the cylinder seal. Hieroglyph: kuThari 'crucible' Rebus: kuThari'storekeeper

Inscription: Sharkalishshari, King of Akkad. Ibnisharrum, the scribe (is) your servant. After Collon 1987: 134 No. 329. Musee du Louvre AO 22303.

lokANDa 'overflowing pot' Rebus: lokhaNDa 'metal implements, excellent implements'

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati) ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' PLUS meDh 'curl' Rebus: meD 'iron'

Hieroglyph: rã̄go ʻ buffalo bull ʼ

Rebus: Pk. raṅga 'tin' P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼOr. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼraṅgaada -- m. ʻ borax ʼ lex.Kho. (Lor.) ruṅ ʻ saline ground with white efflorescence, salt in earth ʼ *raṅgapattra ʻ tinfoil ʼ. [raṅga -- 3, páttra -- ]B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.

![http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_WSQsPuiQ9Nc/Sw0x5C8A4vI/AAAAAAAAB5A/Ka_YX6nrv5c/s400/Pashupati-sacrifice.jpg]() balivárda (balīv° ŚBr.) m. ʻ ox, bull ʼ TBr., balivanda- m. Kāṭh., barivarda -- m. lex. [Poss. a cmpd. of balín -- (cf. *balilla -- ) and a non -- Aryan word for ʻ ox ʼ (cf. esp. Nahālī baddī and poss. IA. forms like Sik. pāḍō ʻ bull < *pāḍḍa -- : EWA ii 419 with lit.)]Pa. balivadda -- m. ʻ ox ʼ, Pk. balĭ̄vadda -- , balidda -- , baladda -- m. (cf. balaya -- m. < *balaka -- ?); L. baledā, mult. baled m. ʻ herd of bullocks ʼ (→ S. ḇaledo m.); P. bald, baldh, balhd m. ʻ ox ʼ, baled, baledā m. ʻ herd of oxen ʼ, ludh. bahld, balēd m. ʻ ox ʼ; Ku. balad m. ʻ ox ʼ, gng. bald, N. (Tarai) barad, A. balad(h), B. balad, Or. baḷada, Bi. barad(h), Mth. barad (hyper -- hindiismbaṛad), Bhoj. baradh, Aw.lakh. bardhu, H. balad, barad(h), bardhā m. (whence baladnā ʻ to bull a cow ʼ), G. baḷad m.

balivárda (balīv° ŚBr.) m. ʻ ox, bull ʼ TBr., balivanda- m. Kāṭh., barivarda -- m. lex. [Poss. a cmpd. of balín -- (cf. *balilla -- ) and a non -- Aryan word for ʻ ox ʼ (cf. esp. Nahālī baddī and poss. IA. forms like Sik. pāḍō ʻ bull < *pāḍḍa -- : EWA ii 419 with lit.)]Pa. balivadda -- m. ʻ ox ʼ, Pk. balĭ̄vadda -- , balidda -- , baladda -- m. (cf. balaya -- m. < *balaka -- ?); L. baledā, mult. baled m. ʻ herd of bullocks ʼ (→ S. ḇaledo m.); P. bald, baldh, balhd m. ʻ ox ʼ, baled, baledā m. ʻ herd of oxen ʼ, ludh. bahld, balēd m. ʻ ox ʼ; Ku. balad m. ʻ ox ʼ, gng. bald, N. (Tarai) barad, A. balad(h), B. balad, Or. baḷada, Bi. barad(h), Mth. barad (hyper -- hindiismbaṛad), Bhoj. baradh, Aw.lakh. bardhu, H. balad, barad(h), bardhā m. (whence baladnā ʻ to bull a cow ʼ), G. baḷad m.

balivardin -- .Addenda: balivárda -- [Cf. Ap. valivaṇḍa -- ʻ mighty ʼ, OP. balavaṇḍā]: WPah.kc. bɔḷəd m., kṭg. bɔḷd m. (LNH 30 bŏḷd), J. baldm., Garh. baḷda ʻ bullock ʼ.(CDIAL 9176)

Bhāratam Janam, ‘metalcaster folk’ who were also seafaring merchants, lived on the banks of Sapta Sindhu, ‘seven rivers’. Many of them were also dhokra kamar, artisans with expertise in 1. cire perdue(lost-wax) techniques of casting and 2. creation of metal alloys during the Bronze Age.

What then are the semantics of 'elo, elelo' and ‘helava, helavo’? They are a celebration of the splendour of the sun and sung in tune with the tossing of the boat in the waves of the river or ocean:

Ta. el lustre, splendour, light, sun, daytime; elli, ellai sun, daytime; ilaku (ilaki-), ilaṅku (ilaṅki-) to shine, glisten, glitter. Ma.ilakuka to shine, twinkle; ilaṅkuka to shine; el lustre, splendour,light; ella light. Te. (K.) elamu to be shiny, splendid. Cf. 861 Ta.eṟi and 869 Ta. eṉṟu. / ? Cf. Pkt. (DNM) alla- day.(DEDR 829)

Kol. (Kin.) elava a wave. Go. (A.) helva id., flood (DEDR 830) *ullōḍa ʻ commotion ʼ. [ullōla -- m. ʻ large wave ʼ Kād.: √luḍ] Pa. ullōla -- m. ʻ commotion, wave ʼ; Pk. ullōla -- m. ʻ uproar ʼ; Si. ulela ʻ wave, whirling in water, festival ʼ. (CDIAL 2381)

Mleccha speech was a spoken form of eastern Bharatam.

Patanjali explains (Pat. I: 2,3-9: mlecchA mA bhUma. Iti adhyeyam vyAkaraNam. His paraphrase of S’atapatha Brahmana (3.2.1.24) has: te asurA helayo yelaya it kurvantah parA bahuUvuh. tasmAt brAhmaNo na mlecchitavai na apAbhASitvai. Mleccho ha vA eSo yad apazabdah. mlecchA mA bhUma. iti adhyeyam vyAkaraNam. The original text as quoted by Patanjali has: tAm devAh asurebhyo ‘ntarAyams tAm svIkRtyAgnAv eva parigRhya, sarvahutam ajuhavur, Ahutir hi devAnAm say Am evAmUm anuSTubhAjuhavus, tas evainAm tad devAh svyakurvata, te ‘surA Attavacaso; he ‘lavo h ‘lava iti vadantah parAbabhUvuh tatraitAm api vAcam Ucuh upajijnAsyAm sa mlecchas, tasmAn na brAhmaNo mleched, asuryA haiSA vA, natevaiSa dviSatAm sapatnAnAm Adatte, vAcam te ‘syAt, tavacasah parAbhavanti, ya evam etad veda.

Sayana explains that he’lavo stands for he’rayo, that is, ho, the spiteful (enemies)’ which the Asura were unable to pronounce correctly. The Kanva text, however, reads: te hattavAko ‘surA hailo haila iti etAm vAcam vadantah parAbabhUvuh (that is, He ilA, ‘ho, speech’. Mahabhashya provides the third version.

*mrēcchati ~ mlḗcchati ʻ speaks indistinctly ʼ ŚBr. [MIA. mr -- < ml -- ? See Add. -- √mlēch]K. briċhun, pp. bryuċhu ʻ to weep and lament, cry as a child for something wanted or as motherless child ʼ.(CDIAL 10384)

A. mleccha-; verbal mlecchati, mliṣṭa-, mlecchita-

1.1. Earliest reference is in the later Veda, śatapathabrāhmaṇa, 3.2.1.24: the noun mleccha-, used of Asura celestial beings who speak imprecise language whether ill-pronounced or foreign. The word helayo, variant hailo, is quoted. No vocalization is given for this mythic allusion.

2. Epic usage. Mahābhārata contrasts mleccha- with the ārya- and has the mleccha-bhāṣā, 'Mleccha language', andmleccha-vāk 'using Mleccha speech'. The Dharmasūtra text Manu-smṛti, 2.23, has the mleccha-deśa- 'Mleccha country' as unfit for Brahmanical sacrifices.

2. 1. The Mahābhārata places Mleccha loosely in east, north, and west. The Rāmāyaṇa has Mleccha for the Matsya people of Rajputana (see S. Levi, Journal Asiatique, XIe Ser., XI, 1, 1918, 123).

2. Varāhamihira, c. 550 CE, placed the Mleccha in the upara- region, the western. His upara- region refers to the peoples beyond the Sindhu, Indus, for whom Mahābhārata had the epithet pāre-sindhavah 'beyond the Sindhu'. Varāhamihira has peoples reaching from Vokkāṇa- 'Wakhān', through Pancanada- 'Panjab', to the Pārata-, Pārada-, which is the Greek.

Linguistic evidence

1. (a) Later Veda, mleccha- and verbal mlecchati, with participle in the Scholiast to Pāṇini mliṣṭa-; mlecchita- is also cited. Patanjali has the infinitive mlecchitavai.

(b) Pali, in the oldest texts, Dīgha-nikāya and Vinaya, milakkhu-, milakkhuka-, milakkha-, milakkha-bhāsā, and latermilāca-.

(c) Jaina older Ardha-māgadhī, milakkha- (with Vokkāṇa- and yavana- (Wakhān' and 'Greek'), milakkhu-, milikkhu-, mileccha-, and Māhārāṣṭrī miliṭṭha- 'speaking indistinctly'.

(d) Buddhist Sanskrit mlecha-, whence Saka Khotan mīlaicha-.

(e) New Indo-Aryan in R.L. Turner, Comparative dictionary, no. 10398, Kāśmīrī mīch (with -ch from older -cch-, not -kṣ-); Bengali mech of a Tibeto-Burmese tribe, Sinhalese milidu, milindu 'savage', milis, maladu, Panjābī milech, malech.

The Pali -kkh- was explained as secondary to -cch- by J. Wackernage, Altindische Grammatik, 1, 154; but was unexplained according to Turner, loc. cit.

2. The starting-point of the interpretation should be a form *mlekṣa-, mlikṣ-. Within the Veda there is a variation between -cch- (-ch-) and -kṣ- as in Atharva-veda ṛccharā- besides śukla-yajur-veda, Vājasneyi-samhitā ṛkśalā-'fetter',and within the Atharva-veda in parikṣit- and variant paricchit- 'surrounding'. Hence śatapathabrāhmaṇamleccha- may be traced to older *mlekṣa-. The kṣ was replaced by -kkh- or by retroflex -ch- or by palatalized -cch- in different dialects. Within the Veda there was also variation kśā-, kṣā-, and khyā- from kaś-, corresponding to Avestanxsā- from kas- 'to look at'.

If the oldest form had then *mlekṣa-, this -kṣ- could be accepted as a substitute for a foreign velar fricative

![]()

(the sound expressed in Arabic script by خ kh).

If the word *mlekṣ- was a foreign name, it was adapted to the usual Vedic verbal system, giving participle mliṣṭa- in the grammarians, supported by the Jaina Māhārāṣṭrī miliṭṭha-.

The vowel -e- of mleccha- was thus adapted into the ablaut system -e-: -i-.

For recent comments on mleccha, see Wackernage, Altindische Grammatik. Introduction generale. Nouvelle edition...par Louis Renou, 1957, 73; M. Mayrhofer, Kurzgefasstes etymologisches Worterbuch des Altindischen, 699, mleccha.

மிழலை¹ miḻalai, n. < மிழற்று-. cf. mlīṣṭa. Prattle, lisp;மழலைச்சொல். (சூடா.)மிழலை² miḻalai, n.See மிழலைக்கூற்றம். புனலம் புதவின் மிழலையொடு (புறநா. 24).மிழலைக்கூற்றம் miḻalai-k-kūṟṟam, n. < மிழலை² + கூற்றம். A division of Cōḻa-nāṭu; சோணாட்டின் ஒரு பகுதி. (புறநா. 24, உரை.)மிழலைச்சதகம் miḻalai-c-catakam, n. < id. + சதகம்¹. A catakammiḻalai, by Carkkarai-p-pulavar, 16 c.; 16-ஆம் நூற்றாண்டில் சர்க்கரைப்புலவர் மிழலைநாட்டின் பெருமையைப்பற்றிப் பாடிய சதகம்.மிழற்றல் miḻaṟṟal, n. < மிழற்று-. 1. Speaking; சொல்லுகை. (சூடா.) 2. See மிழலை¹. (யாழ். அக.) 3. Noise of speaking; பேசலானெழு மொலி. (யாழ். அக.)மிழற்று-தல் miḻaṟṟu-, 5 v. tr. 1. To prattle, as a child; மழலைச்சொற் பேசுதல். பண் கள் வாய் மிழற்றும் (கம்பரா. நாட்டு. 10). 2. To speak softly; மெல்லக் கூறுதல். யான்பலவும் பேசிற் றானொன்று மிழற்றும் (சீவக. 1626). Ta. miṇumiṇu (-pp-, -tt-) to mumble, speak with a low reiterated sound, murmur as a secret, utter incantations; muṇamuṇa (-pp-, -tt-), muṇumuṇu (-pp-, -tt-) to mutter, murmur; muṇaṅku (muṇaṅki-) to speak in a suppressed tone, mutter in a low tone, murmur; muṉaṅku (muṉaṅki-), muṉaku (muṉaki-) to mutter, murmur, grumble, moan; muṉakkam muttering, murmuring, grumbling, moan; mir̤aṟṟu (mir̤aṟṟi-) to prattle as a child, speak softly; mir̤alai prattle, lisp; mar̤aṟu (mar̤aṟi-) to be indistinct as speech; mar̤alai prattling, babbling. Ma. miṇumiṇukka to mumble, mutter; miṇṭuka to utter, speak low, attempt to speak;miṇṭāṭṭam opening the mouth to speak; miṇṭāte without utterance; muṇemuṇēna mumbling sound. Ka. minuku to speak in an indistinct, faint or low tone, murmur. Tu. muṇumuṇu muttering, mumbling; muṇkuni to say hūṃ expressive of disapproval or unwillingness, cry as a ghost; muṇkele grumbler. Te. minnaka (neg. gerund), (inscr.) miṇṇaka silently, quietly, coolly; (K.)minuku to murmur within oneself; (K.) mun(u)ku to mutter, grumble. / Cf. Skt. miṇmiṇa-, minmina- speaking indistinctly through the nose, Mar. miṇmiṇā speaking low, faintly, indistinctly, H. minminā id.; Pkt. muṇamuṇaï mutters, mumbles. MBE 1969, p. 295, no. 36, for areal etymology (no entry in Turner, CDIAL). (DEDR 4856) मुरमुर (p. 659) [ muramura ] f (Imit.) Muttering, indistinct grumbling.मुरमुरणें (p. 659) [ muramuraṇēṃ ] v i (मुरमुर) To mutter or grumble. 2 unc To whimper. (Marathi)

![Image result for m1429 boat]() m1429 Mohenjo-dar tablet showing a boat carrying a pair of metal ingots. bagalo = an Arabian merchant vessel

m1429 Mohenjo-dar tablet showing a boat carrying a pair of metal ingots. bagalo = an Arabian merchant vessel

(Gujarati) bagala = an Arab boat of a particular description (Ka.); bagalā (M.); bagarige, bagarage = a kind of vessel (Ka.) bagalo = an Arabian merchant vessel (Gujarati) cf. m1429 seal. karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) tamar ‘palm’ (Hebrew) Rebus: tam(b)ra ‘copper’ (Santali) dula ‘pair’ Rebus: dul ‘cast metal’ (Santali) ḍhālako ‘large ingot’. खोट [khōṭa] ‘ingot, wedge’; A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down)(Marathi) khoṭ f ʻalloy (Lahnda) Thus the pair of ligatured oval glyphs read: khoṭ ḍhālako ‘alloy ingots’ PLUS dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'.

At the outset, a disclaimer. I do not have adhikāra to delineate Chandas, the Vedic diction.

So, I started compiling resources to understand Chandas in the context of Indian linguistic area, sprachbund which included Meluhha/Mleccha.

Vedic speech or verse or chandas as Pāṇini calls it is an inflectional language like the ancient Avestan. Bhāṣā is a literary Prākṛt which included Deśī, Mleccha of Indian sprachbund. Pāṇini recognizes that Prākṛt was the parole, spoken tongue with agglutinative features.

The use of the gloss Bhāṣā is significant. In many vernaculars, cognate words use the term to refer to speech as in Thai bisi ‘to say’, Malay basa ‘to read’.

Chandas is sacred speech. So was Meluhha rendered in mlecchita vikalpa as visible language evolved with intimations of sacredness associated with symbols of the type shown on kudurru or sculptural freizes.

Meluhha venerated the smithy as a temple and used the same gloss to denote both a temple and a smithy: kole.l

Clearly, chandas and mleccha were in vogue simultaneously. I do not have the linguistic competence to isolate the similarities, variations, exchanges between chandas and mleccha.

Kuiper has demonstrated the presence of Munda words in Sanskrit. The exercise can also be extended to demonstrate Munda (mleccha) words in chandas.

Manansala makes a claim that the compounding of words in bhāṣā showed the highly-agglutinative nature of the language, a process which seemed only to be borrowed in Chandas. ‘The use of the absolutive or past participle in the proposition becomes firmly established in the Bhasa and related languages…the prevalence of SOV word order and the frequent occurrence of the subject occurring after the verb, as in the Austronesian languages, also mark tendencies which can safely be classified as non-IE…The morphological similarities between Bhasa and the derived languages, with the Dravidian cannot be easily put aside. The evidence shows that morphology is not as easily borrowed as modern philologists assert.’ http://asiapacificuniverse.com/pkm/lang.htm See: http://asiapacificuniverse.com/pkm/vedicindia.html

Here is what GP Singh has to say about mleccha: “Kirātas pre-eminently figure among the tribes described in ancient Indian and classical (Greek and Latin) literature. The ancient Indian writers as well as classical geographers and historians, while dealing with the primitive races of India, have accorded prominence to the Kirātas. They constitute one of the major segments of the tribal communities living in the Himalayan and sub-Himalayan regions, forest tracts, mountainous areas and the Gangetic plains, valleys and delta of India. The Kirātas were widely diffused tribe. Broadly speaking, the areas inhabited by them covered some parts of eastern, north-eastern, central, western, northern, southern and so-called Greater or Farther India. Their habitation even beyond the confines of India can also be proved…The lalita-Vistara proves the Kirātas’ knowledge of writing…The Vasāti tribe of Pāṇini (IV.2.53) and Patanjali (IV.2.52) can be identified with the Basatai of Periplus which include the Kirātas too…He also refers to the Barbaras (IV.3.93) who are generally associated with the Kirātas…The Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharata Muni (200 BCE-200 CE), one of the rare sources, specifically deals with the Prakrt language of the Kirāta…This text also used the Barbara-Kirāta together. This source provides some clues about the languages spoken by the Barbara-Kirātas inhabiting north-western region…In the Kumārasambhava, the Kirātas have been described as wild tribe living in the hills, mountains and forests. They have been classed as the mlecchas… In one of the old Cham inscriptions of Champa in Indo-China the Kirātas have been associated with Vṛlah race of Champa (Vṛlah-Kirāta-Vita)… The speakers of the mleccha language were called Milakkhas. The term mlekha was used for the first time by the Brahmanas in the sense of a barbarous language spoken by all those (including degraded Aryans and non-Aryan tribes) who wre outside the pale of Aryan culture. From the Buddhist and Jaina texts it is evident that the Kirātas, Pulindas, Andhrakas, Yonakas, Barbaras, Śabaras and others were speakers of this language (Milakkhānāmbhāṣā) which was by and large unintelligible to the Aryans. This language had some thirteen to eighteen forms.” (GP Singh, 2008, Researches into the history and civilization of the Kirātas, New Delhi, Gyan Publishing House, pp. 3, 26, 28, 36, 82).

Varahamihira says: Mleccha yavana honored like ṛṣi-s since they have interest in sciences.....mleccha hi yavanah teṣu samyak śāstram idam sthitam/ ṛṣivat te 'pi pūjyante kim punar daivavid dvijah (Brihat-Samhita 2.14)].पैजवन Mn. vii , 41 is a yavana. (fr. पिजवन) patr. of सु-दास् and of several men RV.

Mlecchas are yavana ( communities). The yavana communities have a well established < pratishtitam> understanding of this excellent discipline < samyak- shaastram> , which is vedanga jyotisha and related ( practices). ( Internally, with in the community. in the yavana communities) , the yavana / mleccha people , learned ( in this discipline) are well honored (poojyante) . The model of honoring is on the same lines ( te api : notice the proper construction of the upasarga api) as Shistas ( = vedic community people) honor their own community learned people who specialize and practice this excellent discipline ( VEDANGA JYOTISHA). What is the reference scale to compare the honor? - < daivavad = similar to the respect shown to God= daiva). VEDANGA JYOTISHA scaled down practices did exist across the pluralistic beyond- brahmana comunities in India. The learned traditional elders were honored intra community and inside community. The standard was set by the Daivajna Brahmana. Varahamihira documents the highest standard; and not the historic social tribal practices.

A reason for the disciplinary rigour in pronunciation insisted for chandas and chastised in meluhha speech is provided in an episode narrated in Bhagavata Purana. It should be underscored that both chandas and meluhha are integral parts of Indian sprachbund, the language of the Bhāratam Janam, 'metalcaster folk'.

Bhagavat Purana,SB 6.9.11

After Viśvarūpa was killed, his father, Tvaṣṭā, performed ritualistic ceremonies to kill Indra. He offered oblations in the sacrificial fire, saying, “O enemy of Indra, flourish to kill your enemy without delay.”

“Tvaṣṭā intended to chant the word indra-śatro, meaning, “O enemy of Indra.” In this mantra, the word indra is in the possessive case (ṣaṣṭhī), and the word indra-śatro is called a tat-puruṣa compound (tatpuruṣa-samāsa). Unfortunately, instead of chanting the mantra short, Tvaṣṭā chanted it long, and its meaning changed from “the enemy of Indra” to “Indra, who is an enemy.” Consequently instead of an enemy of Indra’s, there emerged the body of Vṛtrāsura, of whomIndra was the enemy.”

From r. to l.

ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin' (One is inlaid with a pair of three short strokes: kolmo 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'; the other is inlaid with three horizontal strokes. One may indicate cast tin and the other may indicate a tin smithy). kolmo 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy'. Thus, tin smithy.

![]() A hieroglyph-multiplex signifying 1. 'selvage' and 2. 'three strands'.

A hieroglyph-multiplex signifying 1. 'selvage' and 2. 'three strands'.1. Hieroglyph: Ta. aṉsu selvage, edge of a cloth (< Te.). To. oc edge, bank of river, border of thicket. Ka. añcu edge, brim, boundary, bank, shore, selvage, border, skirt. Te. ancu skirt, border or selvage of cloth, edge (of sword, etc.), shore, brim. /Cf. Skt. añcala- edge or border of a garment. (DEDR 57) Rebus: ancu'iron' (Tocharian); ams'u 'Soma' (Rigveda)

2. Hieroglyph: धातु [p= 513,3] m. layer , stratum Ka1tyS3r. Kaus3. constituent part , ingredient (esp. [ and in RV. only] ifc. , where often = " fold " e.g. त्रि-ध्/आतु , threefold &c ; cf.त्रिविष्टि- , सप्त- , सु-) RV. TS. S3Br. &c (Monier-Williams) dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.).; S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773) tántu m. ʻ thread, warp ʼ RV. [√tan] Pa. tantu -- m. ʻ thread, cord ʼ, Pk. taṁtu -- m.; Kho. (Lor.) ton ʻ warp ʼ < *tand (whence tandeni ʻ thread between wings of spinning wheel ʼ); S. tandu f. ʻ gold or silver thread ʼ; L. tand (pl. °dũ) f. ʻ yarn, thread being spun, string of the tongue ʼ; P. tand m. ʻ thread ʼ, tanduā, °dūā m. ʻ string of the tongue, frenum of glans penis ʼ; A. tã̄t ʻ warp in the loom, cloth being woven ʼ; B. tã̄t ʻ cord ʼ; M. tã̄tū m. ʻ thread ʼ; Si. tatu, °ta ʻ string of a lute ʼ; -- with -- o, -- ā to retain orig. gender: S. tando m. ʻ cord, twine, strand of rope ʼ; N. tã̄do ʻ bowstring ʼ; H. tã̄tā m. ʻ series, line ʼ; G. tã̄tɔ m. ʻ thread ʼ; -- OG. tāṁtaṇaü m. ʻ thread ʼ < *tāṁtaḍaü, G.tã̄tṇɔ m.(CDIAL 5661)

Rebus: M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; (CDIAL 6773) धातु primary element of the earth i.e. metal , mineral, ore (esp. a mineral of a red colour) Mn. MBh. &c element of words i.e. grammatical or verbal root or stem Nir. Pra1t. MBh. &c (with the southern Buddhists धातु means either the 6 elements [see above] Dharmas. xxv ; or the 18 elementary spheres [धातु-लोक] ib. lviii ; or the ashes of the body , relics L. [cf. -गर्भ]) (Monier-Williams. Samskritam).

Thus, the hieroglyph-multiplex signifies soma as electrum with three minerals, tri-dhAtu, 'iron, gold, silver' compound ore.

eraka 'knave of wheel' rebus: erako 'moltencast'; arka 'copper'.Ara 'spoke of wheel' rebus: Ara 'brass' as in ArakUTa id. (Samskritam) आर--कूट [p= 149,2] 'a kind of brass' (Monier-Williams)

meḍ signifies 'iron' in Munda while a cognate gloss signifies 'copper' in Slavic languages

The gloss 'med' is an adaptation of the Meluhhan gloss vividly identified in Munda languages. meḍ ‘body’ Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.)

Wilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:

Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.

Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'.

~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).

Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.

Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.

KW <i>mENhEd</i>

@(V168,M080)

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

Hieroglyph of a worshipper kneeling: Konḍa (BB) meḍa, meṇḍa id. Pe. menḍa id.

Manḍ. menḍe id. Kui menḍa id. Kuwi (F.) menda, (S. Su. P.) menḍa, (Isr.) meṇḍa id.

Ta. maṇṭi kneeling, kneeling on one knee as an archer. Ma.maṇṭuka to be seated on the heels. Ka. maṇḍi what is bent, the knee. Tu. maṇḍi knee. Te. maṇḍĭ̄ kneeling on one knee. Pa.maḍtel knee; maḍi kuḍtel kneeling position. Go. (L.) meṇḍā, (G. Mu. Ma.) Cf. 4645 Ta.maṭaṅku (maṇi-forms). / ? Cf. Skt. maṇḍūkī- (DEDR 4677)

Hieroglyph: Pa. vēdha -- m. ʻ prick, wound ʼ; Pk. vēha -- m. ʻ boring, hole ʼ, P. veh, beh m., H. beh m., G.veh m.(CDIAL 12108) vēdha m. ʻ hitting the mark ʼ MBh., ʻ penetration, hole ʼ VarBr̥S. [√vyadh]

Hieroglyph: Ta. vēr̤am bamboo; European bamboo reed; kaus; sugar-cane; vēy bamboo; vēyal short-sized bamboo. Ma. vēr̤am a reed, esp. Arundo tibialis and Bambusa baccifera.(DEDR 5541) vētasá m. ʻ ratan, reed ʼ RV. [See vēta -- , vētrá -- . - Paš. Gmb. indicate *vētaśa -- Pa. vētasa -- m. ʻ Calamus rotang ʼ, Pk. vēdasa -- , vēasa -- m.; Ash. wiẽs ʻ willow ʼ, Paš.shut. wēš, Gmb. wyãdotdot;š; K. bisa m. ʻ Salix babylonica ʼ, L.haz. bīs, N. baĩs ʻ Salix tetrasperma ʼ. -- Dm. bigyē˜ˊs ʻ willow ʼ (big<-> scarcely < vr̥kṣá -- , but cf. Ḍ. bīk s.v. vēta-- ). -- Pk. vēḍasa -- , °ḍisa -- m. ʻ ratan cane ʼ (CDIAL 12099)

Hieroglyph: mēthí m. ʻ pillar in threshing floor to which oxen are fastened, prop for supporting carriage shafts ʼ AV., °thī -- f. KātyŚr.com., mēdhī -- f. Divyāv. 2. mēṭhī -- f. PañcavBr.com., mēḍhī -- , mēṭī -- f. BhP.1. Pa. mēdhi -- f. ʻ post to tie cattle to, pillar, part of a stūpa ʼ; Pk. mēhi -- m. ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ, N. meh(e), miho, miyo, B. mei, Or. maï -- dāṇḍi, Bi. mẽh, mẽhā ʻ the post ʼ, (SMunger) mehā ʻ the bullock next the post ʼ, Mth. meh, mehā ʻ the post ʼ, (SBhagalpur)mīhã̄ ʻ the bullock next the post ʼ, (SETirhut) mẽhi bāṭi ʻ vessel with a projecting base ʼ.2. Pk. mēḍhi -- m. ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ, mēḍhaka<-> ʻ small stick ʼ; K. mīr, mīrü f. ʻ larger hole in ground which serves as a mark in pitching walnuts ʼ (for semantic relation of ʻ post -- hole ʼ see kūpa -- 2); L. meṛh f. ʻ rope tying oxen to each other and to post on threshing floor ʼ; P. mehṛ f., mehaṛ m. ʻ oxen on threshing floor, crowd ʼ; OA meṛha, mehra ʻ a circular construction, mound ʼ; Or. meṛhī, meri ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ; Bi. mẽṛ ʻ raised bank between irrigated beds ʼ, (Camparam) mẽṛhā ʻ bullock next the post ʼ, Mth. (SETirhut)mẽṛhā ʻ id. ʼ; M. meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻ post, forked stake ʼ.(CDIAL 10317)

Hieroglyph: *mēṇḍhī ʻ lock of hair, curl ʼ. [Cf. *mēṇḍha -- 1 s.v. *miḍḍa -- ]S. mī˜ḍhī f., °ḍho m. ʻ braid in a woman's hair ʼ, L. mē̃ḍhī f.; G. mĩḍlɔ, miḍ° m. ʻ braid of hair on a girl's forehead ʼ; M. meḍhā m. ʻ curl, snarl, twist or tangle in cord or thread ʼ.(CDIAL 10312)

Hieroglyph: Ka. mēḍi glomerous fig tree, Ficus racemosa; opposite-leaved fig tree, F. oppositifolia. Te. mēḍi F. glomerata. Kol. (Kin.) mēṛi id. [F. glomerata Roxb. = F. racemosa Wall.](DEDR 5090)udumbára -- , udú° m. ʻ the tree Ficus glomerata ʼ TS., n. ʻ its fruit ʼ ŚBr. 2.uḍumbára -- m. AV. 3. *dumbara. 4. *ḍumbara -- . [Prob. ← Austro -- as. EWA i 104 with lit.]1. Pa. udumbara -- m. ʻ Ficus glomerata ʼ, Dhp. udumara, Pk. uduṁbara -- , uuṁ°, uṁ° m.; Ku. umar ʻ a partic. kind of tree used for burnt offerings ʼ; H. ūmar m., °rī f. ʻ F. glomerata ʼ; OG. ūṁbara m., G. umrɔ, ū̃brɔ, umarṛɔ m. ʻ wild fig tree ʼ, umarṛũ n. ʻ its fruit ʼ; M. ũbar m. ʻ F. glomerata ʼ, n. ʻ its fruit ʼ, Ko. umbar.2. Or. uṛumara ʻ F. glomerata ʼ.3. H. dũbur m., Si. dim̆bul, dum̆°.4. N. ḍumri, A. ḍimaru, B. ḍumur, Or. ḍumara, ḍambura, ḍimbiri, Mth. ḍūmri, Bhoj. ḍūmari, H.ḍūmar m.(CDIAL 1942)

With curved horns, the ’anthropomorph’ is a ligature of a mountain goat or markhor (makara) and a fish incised between the horns. Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. At Sheorajpur, three anthropomorphs in metal were found. (Sheorajpur, Dt. Kanpur. Three anthropomorphic figures of copper. AI, 7, 1951, pp. 20, 29).

One anthropomorph had fish hieroglyph incised on the chest of the copper object, Sheorajpur, upper Ganges valley, ca. 2nd millennium BCE, 4 kg; 47.7 X 39 X 2.1 cm. State Museum, Lucknow (O.37) Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayo, ayas ‘metal. Thus, together read rebus: ayo meḍh ‘iron stone ore, metal merchant.’

![]()

A remarkable legacy of the civilization occurs in the use of ‘fish‘ sign on a copper anthropomorph found in a copper hoard. This is an apparent link of the ‘fish’ broadly with the profession of ‘metal-work’. The ‘fish’ sign is apparently related to the copper object which seems to depict a ‘fighting ram’ symbolized by its in-curving horns. The ‘fish’ sign may relate to a copper furnace. The underlying imagery defined by the style of the copper casting is the pair of curving horns of a fighting ram ligatured into the outspread legs (of a warrior).

The center-piece of the makara symbolism is that it is a big jhasa, big fish, but with ligatured components (alligator snout, elephant trunk, elephant legs and antelope face). Each of these components can be explained (alligator: manger; elephant trunk: sunda; elephant: ibha; antelope: ranku; rebus: mangar ‘smith’; sunda ‘furnace’; ib ‘iron’; ranku ‘tin’); thus the makara jhasa or the big composite fish is a complex of metallurgical repertoire.)

One nidhi was makara (syn. Kohl, antimony); the second was makara (or, jhasa, fish) [bed.a hako (ayo)(syn. bhed.a ‘furnace’; med. ‘iron’; ayas ‘metal’)]; the third was kharva (syn. karba, iron).

bhaTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayo, ayas ‘metal. Thus, together read rebus: bhaTa ayo meḍh ‘smelter, iron stone ore, metal merchant.’

![]()

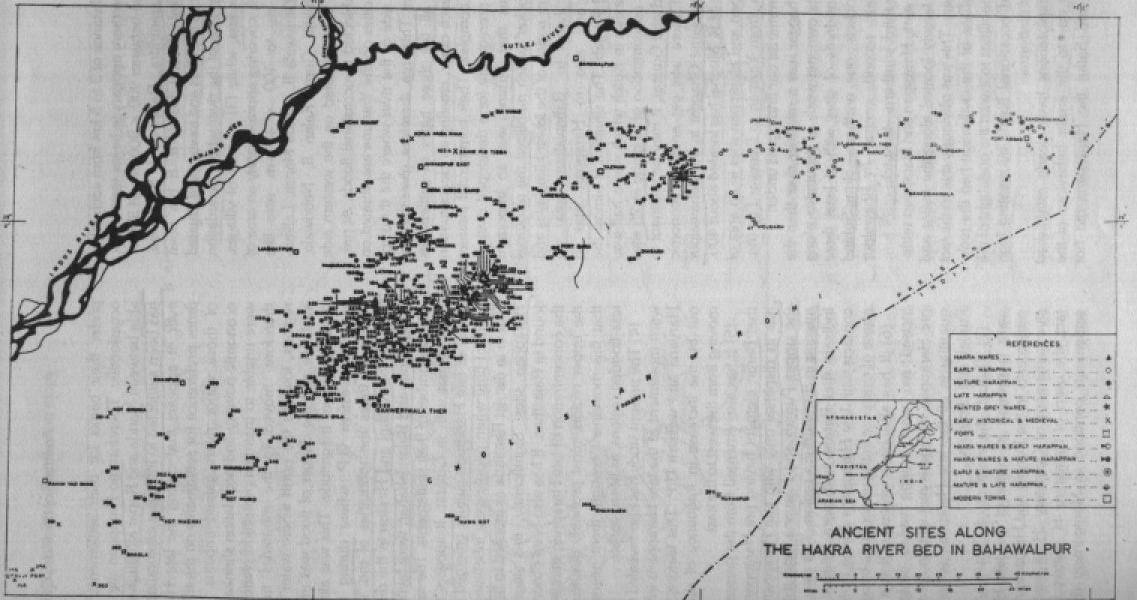

Ganweriwala tablet. Ganeriwala or Ganweriwala (Urdu: گنےریوالا Punjabi: گنیریوالا) is a Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization site in Cholistan, Punjab, Pakistan.

Glyphs on a broken molded tablet, Ganweriwala. The reverse includes the 'rim-of-jar' glyph in a 3-glyph text. Observe shows a person seated on a stool and a kneeling adorant below.

Hieroglyph: kamadha 'penance' Rebus: kammata 'coiner, mint'.Reading rebus three glyphs of text on Ganweriwala tablet: brass-worker, scribe, turner:

1. kuṭila ‘bent’; rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) [cf. āra-kūṭa, ‘brass’ (Skt.) (CDIAL 3230)

2. Glyph of ‘rim of jar’: kárṇaka m. ʻ projection on the side of a vessel, handle ʼ ŚBr. [kárṇa -- ]Pa. kaṇṇaka -- ʻ having ears or corners ʼ; (CDIAL 2831) kaṇḍa kanka; Rebus: furnace account (scribe). kaṇḍ = fire-altar (Santali); kan = copper (Tamil) khanaka m. one who digs , digger , excavator Rebus: karanikamu. Clerkship: the office of a Karanam or clerk. (Telugu) káraṇa n. ʻ act, deed ʼ RV. [√kr̥1] Pa. karaṇa -- n. ʻdoingʼ; NiDoc. karana, kaṁraṁna ʻworkʼ; Pk. karaṇa -- n. ʻinstrumentʼ(CDIAL 2790)

3. khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ‘ turner’ (G.)

h182A, h182B

The drummer hieroglyph is associated with svastika glyph on this tablet (har609) and also on h182A tablet of Harappa with an identical text.

dhollu ‘drummer’ (Western Pahari) Rebus: dul ‘cast metal’. The 'drummer' hieroglyph thus announces a cast metal. The technical specifications of the cast metal are further described by other hieroglyphs on side B and on the text of inscription (the text is repeated on both sides of Harappa tablet 182).

kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'alloy of five metals, pancaloha' (Tamil). ḍhol ‘drum’ (Gujarati.Marathi)(CDIAL 5608) Rebus: large stone; dul ‘to cast in a mould’. Kanac ‘corner’ Rebus: kancu ‘bronze’. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. kanka ‘Rim of jar’ (Santali); karṇaka rim of jar’(Skt.) Rebus:karṇaka ‘scribe’ (Telugu); gaṇaka id. (Skt.) (Santali) Thus, the tablets denote blacksmith's alloy cast metal accounting including the use of alloying mineral zinc -- satthiya 'svastika' glyph.

sattu (Tamil), satta, sattva (Kannada) jasth जसथ् ।रपु m. (sg. dat. jastas ज्तस), zinc, spelter; pewter; zasath ् ज़स््थ् ्or zasuth ज़सुथ ्। रप m. (sg. dat. zastas ु ज़्तस),् zinc, spelter, pewter (cf. Hindī jast). jastuvu; । रपू्भवः adj. (f. jastüvü), made of zinc or pewter.(Kashmiri).

The hieroglyph: svastika repeated five times.

Five svastika are thus read: taṭṭal sattva Rebus: zinc (for) brass (or pewter). *ṭhaṭṭha1 ʻbrassʼ. [Onom. from noise of hammering brass?]N. ṭhaṭṭar ʻ an alloy of copper and bell metal ʼ. *ṭhaṭṭhakāra ʻ brass worker ʼ. 1.Pk. ṭhaṭṭhāra -- m., K. ṭhö̃ṭhur m., S. ṭhã̄ṭhāro m., P. ṭhaṭhiār, °rā m.2. P. ludh. ṭhaṭherā m., Ku. ṭhaṭhero m., N. ṭhaṭero, Bi. ṭhaṭherā, Mth. ṭhaṭheri, H.ṭhaṭherā m.(CDIAL 5491, 5493).

Rebus: ṭhaṭṭar ʻan alloy of copper and bell metalʼ (Nepalese)

The drummer hieroglyph is associated with svastika glyph on this tablet (har609) and also on h182A tablet of Harappa with an identical text.

dhollu ‘drummer’ (Western Pahari) Rebus: dul ‘cast metal’. The 'drummer' hieroglyph thus announces a cast metal. The technical specifications of the cast metal are further described by other hieroglyphs on side B and on the text of inscription (the text is repeated on both sides of Harappa tablet 182).

kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'alloy of five metals, pancaloha' (Tamil). ḍhol ‘drum’ (Gujarati.Marathi)(CDIAL 5608) Rebus: large stone; dul ‘to cast in a mould’. Kanac ‘corner’ Rebus: kancu ‘bronze’. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. kanka ‘Rim of jar’ (Santali); karṇaka rim of jar’(Skt.) Rebus:karṇaka ‘scribe’ (Telugu); gaṇaka id. (Skt.) (Santali) Thus, the tablets denote blacksmith's alloy cast metal accounting including the use of alloying mineral zinc -- satthiya 'svastika' glyph.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

December 13, 2015

Narendra Modi

Narendra Modi

balivárda

balivárda

Reconstruction of Vedic River Sarasvati drainage (After KS Valdiya, 2012)

Reconstruction of Vedic River Sarasvati drainage (After KS Valdiya, 2012)

Sudhir Chaudhary

Sudhir Chaudhary

Jagdish Shetty

Jagdish Shetty

![[prasati%2520mulawarman%255B3%255D.jpg]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-L7CZvk8_Iys/ToIb1RXc2QI/AAAAAAAAAR0/aPzxQNQq0Tg/s1600/prasati%252520mulawarman%25255B3%25255D.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Delhi Chief Minister

Delhi Chief Minister

.jpg)

.jpg)

The property of Associated Journals Ltd in Panchkula.

The property of Associated Journals Ltd in Panchkula.