'Twisted rope' which is identified as an Indus Script hieroglyph is signified on the following 14 artifacts of Ancient Near East, dated from ca. 2400 to 1650 BCE:

Bogazkoy seal impression with 'twisted rope' hieroglyph (Fig. 13) eruvai'kite'dula'pair'eraka'wing' Rebus: eruvai dul'copper cast metal'eraka'moltencast' PLUS dhāu 'strand of rope' Rebus: dhāv 'red ore' (ferrite) ti-dhāu 'three strands' Rebus: ti-dhāv'three ferrite ores: magnetite, hematite, laterite'.

Bogazkoy seal impression with 'twisted rope' hieroglyph (Fig. 13) eruvai'kite'dula'pair'eraka'wing' Rebus: eruvai dul'copper cast metal'eraka'moltencast' PLUS dhāu 'strand of rope' Rebus: dhāv 'red ore' (ferrite) ti-dhāu 'three strands' Rebus: ti-dhāv'three ferrite ores: magnetite, hematite, laterite'.Fig. 1 First cylinder seal-impressed jar from Taip 1, Turkmenistan

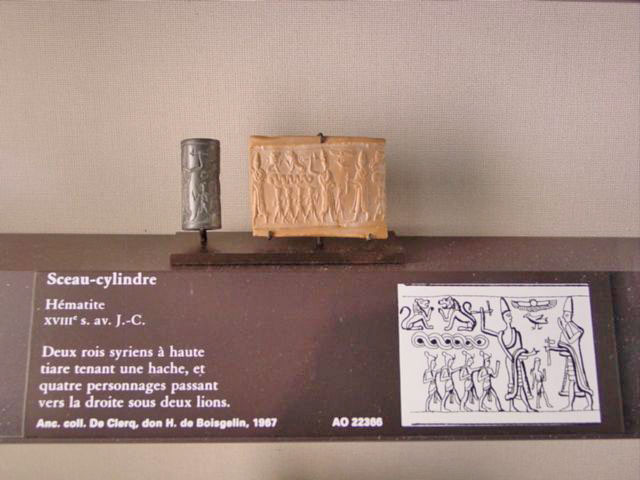

Fig. 2 Hematite cylinder seal of Old Syria ca. 1820-1730 BCE

Fig. 3 Hematite seal. Old Syria. ca. 1720-1650 BCE

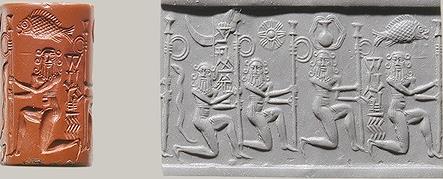

Fig. 4 Cylinder seal modern impression. Mitanni. 2nd millennium BCE

Fig. 5 Cylinder seal modern impression. Old Syria. ca. 1720-1650 BCE

Fig. 6 Cylinder seal. Mitanni. 2nd millennium BCE

Fig. 7 Stone cylinder seal. Old Syria ca. 1720-1650 BCE

Fig. 8 Hematite cylinder seal. Old Syria. ca. early 2nd millennium BCE

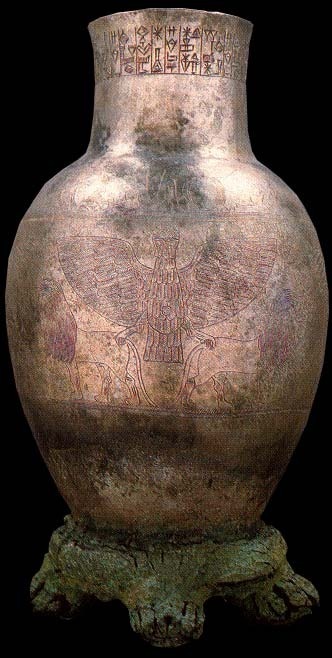

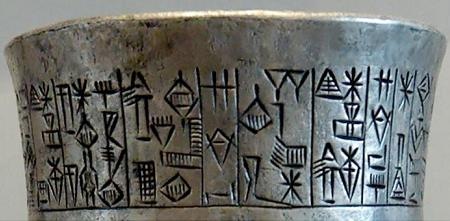

Fig. 9 Fragment of an Iranian Chlorite Vase. 2500-2400 BCE

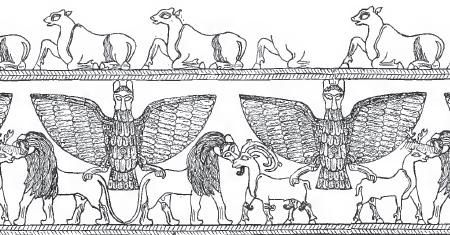

Fig.10 Shahdad standard. ca. 2400 BCE Line drawing

Fig.11 Cylinder seal. 2 seated lions. Twisted rope. Louvre AO7296

Fig.12 Cylinder seal. Sumerian. 18th cent. BCE. Louvre AO 22366

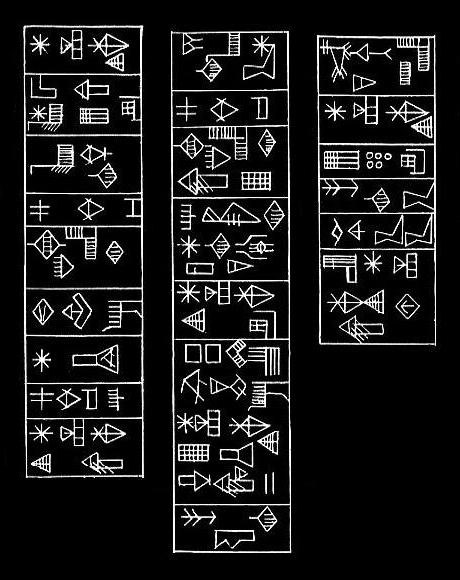

Fig.13 Bogazkoy Seal impression ca. 18th cent. BCE

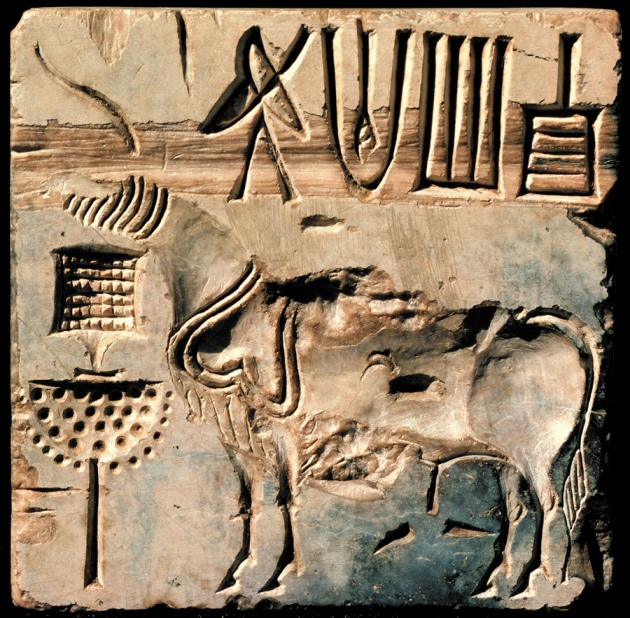

Fig.14 Dudu plaque.Votive bas-relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu in the time of Entemena, prince of Lagash, ca. 2400 BCE Tello (ancient Girsu)

The orthography of the 'twisted rope' is characterised by an endless twist, sometimes signified with three strands of the rope.

Meluhha rebus-metonymy Indus Script cipher on all the 14 seals/artifacts is:

Hieroglyph: ti-dhAtu 'three strands' Rebus: ti-dhAtu'three red stone ores: magnetite, hematite, laterite'.

The three ores are: poLa 'magnetite', bica 'hematite', goTa 'laterite'. The hieroglyphs signifying these mineral ores are: poLa 'zebu', bica 'scorpion' goTa 'round object or seed'.

Some associated hieroglyphs on the 14 seals/artifacts are:

Hieroglyph: poLa'zebu' Rebus: poLa'magnetite' (Fig.1)

Hieroglyph: bica'scorpion' Rebus: bica'hematite'(Fig.4)

Hieroglyph: karaNDava 'aquatic bird' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy'. (Fig.7)

Hieroglyph: kuThAru 'monkey' Rebus: kuThAru 'armourer'. (Fig.2)

Hieroglyph: arye 'lion' (Akkadian) Rebus: arA 'brass'. (Fig.2)

Hieroglyph: eruvai 'kite' Rebus: eruvai 'copper'. (Fig.13)

Hieroglyph: eraka 'wing' Rebus: eraka 'moltencast copper'. (Fig.14)

Hieroglyph: dhangar 'bull' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' (Fig.2)

Hieroglyph: ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'. (Fig.4)

Hieroglyph: kolmo'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi'smithy/forge' (Fig.1)

Hieroglyph: dula'pair' Rebus: dul'cast metal'. (Fig.3)

The semantic elaboration of dhāv 'a red stone ore' is identified in the gloss: dhā̆vaḍ'iron-smelters'. There is a place-name in Karnataka called dhā̆rvā̆ḍ

The suffix -vā̆ḍ in the place-name is also explained in the context of ‘rope’ hieroglyph: vaṭa2 ʻ string ʼ lex. [Prob. ← Drav. Tam. vaṭam, Kan. vaṭi, vaṭara, &c. DED 4268] N. bariyo ʻ cord, rope ʼ; Bi. barah ʻ rope working irrigation lever ʼ, barhā ʻ thick well -- rope ʼ, Mth. barahā ʻ rope ʼ.(CDIAL 11212) Ta. vaṭam cable, large rope, cord, bowstring, strands of a garland, chains of a necklace; vaṭi rope; vaṭṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to tie. Ma. vaṭam rope, a rope of cowhide (in plough), dancing rope, thick rope for dragging timber. Ka. vaṭa, vaṭara, vaṭi string, rope, tie. Te. vaṭi rope, cord. Go. (Mu.) vaṭiya strong rope made of paddy straw (Voc. 3150). Cf. 3184 Ta. tār̤vaṭam. / Cf. Skt. vaṭa- string, rope, tie; vaṭāraka-, vaṭākara-, varāṭaka- cord, string(DEDR 5220).

Dhā̆rvā̆ḍ is an ancient major trading down dealing -- even today -- with iron ore and mineral-belt of Sahyadri mountain ranges in western Karnataka. The word dhāv is derived from dhātu which has two meanings: 'strand of rope' (Rigveda)(hieroglyph) and 'mineral' (metalwork ciphertext of Indian sprachbund.)

I suggest that Shahdad which has a standard of ca. 2400 BCE with the 'twisted rope' hieroglyph -- and hence dealing with ferrote ores (magnetite, hematite, laterite) -- should be recognized as a twin iron-ore town of Dhā̆rvā̆ḍ It is hypothesised that further archaeometallurgical researchers into ancient iron ore mines of Dhā̆rvā̆ḍ region are likely to show possible with an archaeological settlement of Sarasvati_Sindhu civilization: Daimabad from where a seal was discovered showing the most-frequently used Indus Script hieroglyph: rim of jar.

dhāī wisp of fibers added to a rope (Sindhi) Rebus: dhātu 'mineral ore' (Samskritam) dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻa partic. soft red stoneʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(Marathi)

Fig. 1 First cylinder seal-impressed jar from Taip 1, Turkmenistan

(Photo: Kohl 1984: Pl. 15c; drawings after Collon 1987: nos. 600, 599. (After Fig. 5 Eric Olijdam, 2008, A possible central Asian origin for seal-impressed jar from the 'Temple Tower' at Failaka, in: Eric Olijdam and Richard H. Spoor, eds., 2008, Intercultural relations between south and southwest Asia, Studies in commemoration of ECL During Caspers (1934-1996), Society for Arabian Studies Monographs No. 7 [eds. D. Kennet & St J. Simpson], BAR International Series 1826 pp. 268-287). https://www.academia.edu/403945/A_Possible_Central_Asian_Origin_for_the_Seal-Impressed_Jar_from_the_Temple_Tower_at_Failaka

(Photo: Kohl 1984: Pl. 15c; drawings after Collon 1987: nos. 600, 599. (After Fig. 5 Eric Olijdam, 2008, A possible central Asian origin for seal-impressed jar from the 'Temple Tower' at Failaka, in: Eric Olijdam and Richard H. Spoor, eds., 2008, Intercultural relations between south and southwest Asia, Studies in commemoration of ECL During Caspers (1934-1996), Society for Arabian Studies Monographs No. 7 [eds. D. Kennet & St J. Simpson], BAR International Series 1826 pp. 268-287). https://www.academia.edu/403945/A_Possible_Central_Asian_Origin_for_the_Seal-Impressed_Jar_from_the_Temple_Tower_at_Failaka

Decipherment of Indus Script hieroglyphs:

Hieroglyphs on the cylinder impression of the jar are: zebu, stalk (tree?), one-horned young bull (?), twisted rope, birds in flight, mountain-range

dhāī wisp of fibers added to a rope (Sindhi) Rebus: dhātu'mineral ore' (Samskritam) dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻa partic. soft red stoneʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ(Marathi)

poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite ore'

kōḍe, kōḍiya. [Tel.] n. A bullcalf. Rebus: koḍ artisan’s workshop (Kuwi) kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (Assamese)

kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

eruvai 'eagle' Rebus: eruvai 'copper (red)'

dAng 'mountain-range' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'

Thus, the storage jar contents are the message conveyed by the hieroglyph-multiplex: copper smithy workshop magnetite ore, iron castings.

![Cylinder seal]()

Fig. 2 Hematite cylinder seal of Old Syria ca. 1820-1730 BCE

![Cylinder seal]()

Fig. 3 Hematite seal. Old Syria. ca. 1720-1650 BCE

![Cylinder seal and modern impression: male and griffin demon slaying animal; terminal: animal attack scenes, guilloche]()

![Cylinder seal and modern impression: royal figures approaching weather god; divinities]()

![Cylinder seal]()

![Cylinder seal]()

Fig. 7 Stone cylinder seal. Old Syria ca. 1720-1650 BCE

![Cylinder seal]()

![]()

![]()

The Sumerian/Akkadian word sanga, is a loan from Proto-Prakritam or Meluhha of Indian sprachbund. saṁghapati m. ʻ chief of a brotherhood ʼ Śatr. [saṁghá -- , páti -- ]G. saṅghvī m. ʻ leader of a body of pilgrims, a partic. surname ʼ.(CDIAL 12857) saṁghá m. ʻ association, a community ʼ Mn. [√han 1 ]

Pa. saṅgha -- m. ʻ assembly, the priesthood ʼ; Aś. saṁgha -- m. ʻ the Buddhist community ʼ; Pk. saṁgha -- m. ʻ assembly, collection ʼ; OSi. (Brāhmī inscr.) saga, Si. san̆ga ʻ crowd, collection ʼ. -- Rather <saṅga -- : S. saṅgu m. ʻ body of pilgrims ʼ (whence sã̄go m. ʻ caravan ʼ), L. P. saṅg m. (CDIAL 12854).

kōla = woman (Nahali) Rebus: kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five

![]() Santali glosses

Santali glosses

![]() Twisted rope as hieroglyph on a plaque.

Twisted rope as hieroglyph on a plaque.

![Displaying ScreenShot1762.bmp]() This hieroglyph-multiplex seen on a cylinder seal is deciphered: Hieroglyph: ti-dhātu 'three-strands of rope' Rebus: ti-dhāū, ti-dhāv; dula 'pair' Rebus: dul ''cast metal' PLUS arye 'lion' Rebus: Ara 'brass' (which may be an alloy of copper, zinc and tin minerals and/or arsenopyrites including ferrous ore elements). Thus, the hieoglyph-multiplex composition signifies dul Ara 'cast brass alloy' of ti-dhātu 'three minerals'.

This hieroglyph-multiplex seen on a cylinder seal is deciphered: Hieroglyph: ti-dhātu 'three-strands of rope' Rebus: ti-dhāū, ti-dhāv; dula 'pair' Rebus: dul ''cast metal' PLUS arye 'lion' Rebus: Ara 'brass' (which may be an alloy of copper, zinc and tin minerals and/or arsenopyrites including ferrous ore elements). Thus, the hieoglyph-multiplex composition signifies dul Ara 'cast brass alloy' of ti-dhātu 'three minerals'.

![]()

![]()

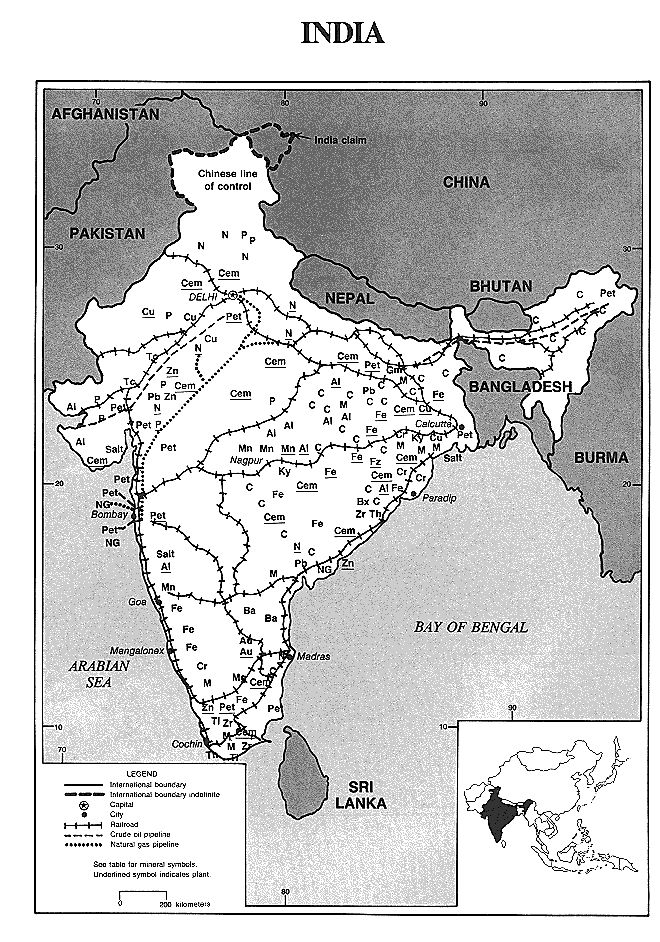

Located on the Map of India are regions with Fe (Iron ore) mines: the locations include Dharwad and Ib.

![]()

![]()

The station derives its name from Ib River flowing nearby. Ib railway station came up with the opening of the Nagpur-Asansol main line of Bengal Nagpur Railway in 1891. It became a station on the crosscountry Howrah-Nagpur-Mumbai line in 1900 In 1900, when Bengal Nagpur Railway was building a bridge across the Ib River, coal was accidentally discovered in what later became Ib Valley Coalfield. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ib_railway_station

![]()

![]() This etymon indicates the possible reading of the tall flagpost carried by kneeling persons with six locks of hair: baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'. Associated with nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

This etymon indicates the possible reading of the tall flagpost carried by kneeling persons with six locks of hair: baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'. Associated with nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

![]()

![]() Situated at the end of a small delta on a dry plain, Shahdad was excavated by an Iranian team in the 1970s. (Courtesy Maurizio Tosi)

Situated at the end of a small delta on a dry plain, Shahdad was excavated by an Iranian team in the 1970s. (Courtesy Maurizio Tosi) ![]() An Iranian-Italian team, including archaeologist Massimo Vidale (right), surveyed the site in 2009. (Courtesy Massimo Vidale) The peripatetic English explorer Sir Aurel Stein, famous for his archaeological work surveying large swaths of Central Asia and the Middle East, slipped into Persia at the end of 1915 and found the first hints of eastern Iran's lost cities. Stein traversed what he described as "a big stretch of gravel and sandy desert" and encountered "the usual...robber bands from across the Afghan border, without any exciting incident." What did excite Stein was the discovery of what he called "the most surprising prehistoric site" on the eastern edge of the Dasht-e Lut. Locals called it Shahr-i-Sokhta ("Burnt City") because of signs of ancient destruction. It wasn't until a half-century later that Tosi and his team hacked their way through the thick salt crust and discovered a metropolis rivaling those of the first great urban centers in Mesopotamia and the Indus. Radiocarbon data showed that the site was founded around 3200 B.C., just as the first substantial cities in Mesopotamia were being built, and flourished for more than a thousand years. During its heyday in the middle of the third millennium B.C., the city covered more than 150 hectares and may have been home to more than 20,000 people, perhaps as populous as the large cities of Umma in Mesopotamia and Mohenjo-Daro on the Indus River. A vast shallow lake and wells likely provided the necessary water, allowing for cultivated fields and grazing for animals. Built of mudbrick, the city boasted a large palace, separate neighborhoods for pottery-making, metalworking, and other industrial activities, and distinct areas for the production of local goods. Most residents lived in modest one-room houses, though some were larger compounds with six to eight rooms. Bags of goods and storerooms were often "locked" with stamp seals, a procedure common in Mesopotamia in the era. Shahr-i-Sokhta boomed as the demand for precious goods among elites in the region and elsewhere grew. Though situated in inhospitable terrain, the city was close to tin, copper, and turquoise mines, and lay on the route bringing lapis lazuli from Afghanistan to the west. Craftsmen worked shells from the Persian Gulf, carnelian from India, and local metals such as tin and copper. Some they made into finished products, and others were exported in unfinished form. Lapis blocks brought from the Hindu Kush mountains, for example, were cut into smaller chunks and sent on to Mesopotamia and as far west as Syria. Unworked blocks of lapis weighing more than 100 pounds in total were unearthed in the ruined palace of Ebla, close to the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeologist Massimo Vidale of the University of Padua says that the elites in eastern Iranian cities like Shahr-i-Sokhta were not simply slaves to Mesopotamian markets. They apparently kept the best-quality lapis for themselves, and sent west what they did not want. Lapis beads found in the royal tombs of Ur, for example, are intricately carved, but of generally low-quality stone compared to those of Shahr-i-Sokhta. Pottery was produced on a massive scale. Nearly 100 kilns were clustered in one part of town and the craftspeople also had a thriving textile industry. Hundreds of wooden spindle whorls and combs were uncovered, as were well-preserved textile fragments made of goat hair and wool that show a wide variation in their weave. According to Irene Good, a specialist in ancient textiles at Oxford University, this group of textile fragments constitutes one of the most important in the world, given their great antiquity and the insight they provide into an early stage of the evolution of wool production. Textiles were big business in the third millennium B.C., according to Mesopotamian texts, but actual textiles from this era had never before been found.

An Iranian-Italian team, including archaeologist Massimo Vidale (right), surveyed the site in 2009. (Courtesy Massimo Vidale) The peripatetic English explorer Sir Aurel Stein, famous for his archaeological work surveying large swaths of Central Asia and the Middle East, slipped into Persia at the end of 1915 and found the first hints of eastern Iran's lost cities. Stein traversed what he described as "a big stretch of gravel and sandy desert" and encountered "the usual...robber bands from across the Afghan border, without any exciting incident." What did excite Stein was the discovery of what he called "the most surprising prehistoric site" on the eastern edge of the Dasht-e Lut. Locals called it Shahr-i-Sokhta ("Burnt City") because of signs of ancient destruction. It wasn't until a half-century later that Tosi and his team hacked their way through the thick salt crust and discovered a metropolis rivaling those of the first great urban centers in Mesopotamia and the Indus. Radiocarbon data showed that the site was founded around 3200 B.C., just as the first substantial cities in Mesopotamia were being built, and flourished for more than a thousand years. During its heyday in the middle of the third millennium B.C., the city covered more than 150 hectares and may have been home to more than 20,000 people, perhaps as populous as the large cities of Umma in Mesopotamia and Mohenjo-Daro on the Indus River. A vast shallow lake and wells likely provided the necessary water, allowing for cultivated fields and grazing for animals. Built of mudbrick, the city boasted a large palace, separate neighborhoods for pottery-making, metalworking, and other industrial activities, and distinct areas for the production of local goods. Most residents lived in modest one-room houses, though some were larger compounds with six to eight rooms. Bags of goods and storerooms were often "locked" with stamp seals, a procedure common in Mesopotamia in the era. Shahr-i-Sokhta boomed as the demand for precious goods among elites in the region and elsewhere grew. Though situated in inhospitable terrain, the city was close to tin, copper, and turquoise mines, and lay on the route bringing lapis lazuli from Afghanistan to the west. Craftsmen worked shells from the Persian Gulf, carnelian from India, and local metals such as tin and copper. Some they made into finished products, and others were exported in unfinished form. Lapis blocks brought from the Hindu Kush mountains, for example, were cut into smaller chunks and sent on to Mesopotamia and as far west as Syria. Unworked blocks of lapis weighing more than 100 pounds in total were unearthed in the ruined palace of Ebla, close to the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeologist Massimo Vidale of the University of Padua says that the elites in eastern Iranian cities like Shahr-i-Sokhta were not simply slaves to Mesopotamian markets. They apparently kept the best-quality lapis for themselves, and sent west what they did not want. Lapis beads found in the royal tombs of Ur, for example, are intricately carved, but of generally low-quality stone compared to those of Shahr-i-Sokhta. Pottery was produced on a massive scale. Nearly 100 kilns were clustered in one part of town and the craftspeople also had a thriving textile industry. Hundreds of wooden spindle whorls and combs were uncovered, as were well-preserved textile fragments made of goat hair and wool that show a wide variation in their weave. According to Irene Good, a specialist in ancient textiles at Oxford University, this group of textile fragments constitutes one of the most important in the world, given their great antiquity and the insight they provide into an early stage of the evolution of wool production. Textiles were big business in the third millennium B.C., according to Mesopotamian texts, but actual textiles from this era had never before been found.![]() A metal flag found at Shahdad, one of eastern Iran's early urban sites, dates to around 2400 B.C. The flag depicts a man and woman facing each other, one of the recurrent themes in the region's art at this time. (Courtesy Maurizio Tosi)

A metal flag found at Shahdad, one of eastern Iran's early urban sites, dates to around 2400 B.C. The flag depicts a man and woman facing each other, one of the recurrent themes in the region's art at this time. (Courtesy Maurizio Tosi) ![]() This plain ceramic jar, found recently at Shahdad, contains residue of a white cosmetic whose complex formula is evidence for an extensive knowledge of chemistry among the city's ancient inhabitants. (Courtesy Massimo Vidale) The artifacts also show the breadth of Shahr-i-Sokhta's connections. Some excavated red-and-black ceramics share traits with those found in the hills and steppes of distant Turkmenistan to the north, while others are similar to pots made in Pakistan to the east, then home to the Indus civilization. Tosi's team found a clay tablet written in a script called Proto-Elamite, which emerged at the end of the fourth millennium B.C., just after the advent of the first known writing system, cuneiform, which evolved in Mesopotamia. Other such tablets and sealings with Proto-Elamite signs have also been found in eastern Iran, such as at Tepe Yahya. This script was used for only a few centuries starting around 3200 B.C. and may have emerged in Susa, just east of Mesopotamia. By the middle of the third millennium B.C., however, it was no longer in use. Most of the eastern Iranian tablets record simple transactions involving sheep, goats, and grain and could have been used to keep track of goods in large households. While Tosi's team was digging at Shahr-i-Sokhta, Iranian archaeologist Ali Hakemi was working at another site, Shahdad, on the western side of the Dasht-e Lut. This settlement emerged as early as the fifth millennium B.C. on a delta at the edge of the desert. By the early third millennium B.C., Shahdad began to grow quickly as international trade with Mesopotamia expanded. Tomb excavations revealed spectacular artifacts amid stone blocks once painted in vibrant colors. These include several extraordinary, nearly life-size clay statues placed with the dead. The city's artisans worked lapis lazuli, silver, lead, turquoise, and other materials imported from as far away as eastern Afghanistan, as well as shells from the distant Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. Evidence shows that ancient Shahdad had a large metalworking industry by this time. During a recent survey, a new generation of archaeologists found a vast hill—nearly 300 feet by 300 feet—covered with slag from smelting copper. Vidale says that analysis of the copper ore suggests that the smiths were savvy enough to add a small amount of arsenic in the later stages of the process to strengthen the final product. Shahdad's metalworkers also created such remarkable artifacts as a metal flag dating to about 2400 B.C. Mounted on a copper pole topped with a bird, perhaps an eagle, the squared flag depicts two figures facing one another on a rich background of animals, plants, and goddesses. The flag has no parallels and its use is unknown. Vidale has also found evidence of a sweet-smelling nature. During a spring 2009 visit to Shahdad, he discovered a small stone container lying on the ground. The vessel, which appears to date to the late fourth millennium B.C., was made of chlorite, a dark soft stone favored by ancient artisans in southeast Iran. Using X-ray diffraction at an Iranian lab, he discovered lead carbonate—used as a white cosmetic—sealed in the bottom of the jar. He identified fatty material that likely was added as a binder, as well as traces of coumarin, a fragrant chemical compound found in plants and used in some perfumes. Further analysis showed small traces of copper, possibly the result of a user dipping a small metal applicator into the container. Other sites in eastern Iran are only now being investigated. For the past two years, Iranian archaeologists Hassan Fazeli Nashli and Hassain Ali Kavosh from the University of Tehran have been digging in a small settlement a few miles east of Shahdad called Tepe Graziani, named for the Italian archaeologist who first surveyed the site. They are trying to understand the role of the city's outer settlements by examining this ancient mound, which is 30 feet high, 525 feet wide, and 720 feet long. Excavators have uncovered a wealth of artifacts including a variety of small sculptures depicting crude human figures, humped bulls, and a Bactrian camel dating to approximately 2900 B.C. A bronze mirror, fishhooks, daggers, and pins are among the metal finds. There are also wooden combs that survived in the arid climate. "The site is small but very rich," says Fazeli, adding that it may have been a prosperous suburban production center for Shahdad. Sites such as Shahdad and Shahr-i-Sokhta and their suburbs were not simply islands of settlements in what otherwise was empty desert. Fazeli adds that some 900 Bronze Age sites have been found on the Sistan plain, which borders Afghanistan and Pakistan. Mortazavi, meanwhile, has been examining the area around the Bampur Valley, in Iran's extreme southeast. This area was a corridor between the Iranian plateau and the Indus Valley, as well as between Shahr-i-Sokhta to the north and the Persian Gulf to the south. A 2006 survey along the Damin River identified 19 Bronze Age sites in an area of less than 20 square miles. That river periodically vanishes, and farmers depend on underground channels called qanats to transport water. Despite the lack of large rivers, ancient eastern Iranians were very savvy in marshaling their few water resources. Using satellite remote sensing data, Vidale has found remains of what might be ancient canals or qanats around Shahdad, but more work is necessary to understand how inhabitants supported themselves in this harsh climate 5,000 years ago, as they still do today.

This plain ceramic jar, found recently at Shahdad, contains residue of a white cosmetic whose complex formula is evidence for an extensive knowledge of chemistry among the city's ancient inhabitants. (Courtesy Massimo Vidale) The artifacts also show the breadth of Shahr-i-Sokhta's connections. Some excavated red-and-black ceramics share traits with those found in the hills and steppes of distant Turkmenistan to the north, while others are similar to pots made in Pakistan to the east, then home to the Indus civilization. Tosi's team found a clay tablet written in a script called Proto-Elamite, which emerged at the end of the fourth millennium B.C., just after the advent of the first known writing system, cuneiform, which evolved in Mesopotamia. Other such tablets and sealings with Proto-Elamite signs have also been found in eastern Iran, such as at Tepe Yahya. This script was used for only a few centuries starting around 3200 B.C. and may have emerged in Susa, just east of Mesopotamia. By the middle of the third millennium B.C., however, it was no longer in use. Most of the eastern Iranian tablets record simple transactions involving sheep, goats, and grain and could have been used to keep track of goods in large households. While Tosi's team was digging at Shahr-i-Sokhta, Iranian archaeologist Ali Hakemi was working at another site, Shahdad, on the western side of the Dasht-e Lut. This settlement emerged as early as the fifth millennium B.C. on a delta at the edge of the desert. By the early third millennium B.C., Shahdad began to grow quickly as international trade with Mesopotamia expanded. Tomb excavations revealed spectacular artifacts amid stone blocks once painted in vibrant colors. These include several extraordinary, nearly life-size clay statues placed with the dead. The city's artisans worked lapis lazuli, silver, lead, turquoise, and other materials imported from as far away as eastern Afghanistan, as well as shells from the distant Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. Evidence shows that ancient Shahdad had a large metalworking industry by this time. During a recent survey, a new generation of archaeologists found a vast hill—nearly 300 feet by 300 feet—covered with slag from smelting copper. Vidale says that analysis of the copper ore suggests that the smiths were savvy enough to add a small amount of arsenic in the later stages of the process to strengthen the final product. Shahdad's metalworkers also created such remarkable artifacts as a metal flag dating to about 2400 B.C. Mounted on a copper pole topped with a bird, perhaps an eagle, the squared flag depicts two figures facing one another on a rich background of animals, plants, and goddesses. The flag has no parallels and its use is unknown. Vidale has also found evidence of a sweet-smelling nature. During a spring 2009 visit to Shahdad, he discovered a small stone container lying on the ground. The vessel, which appears to date to the late fourth millennium B.C., was made of chlorite, a dark soft stone favored by ancient artisans in southeast Iran. Using X-ray diffraction at an Iranian lab, he discovered lead carbonate—used as a white cosmetic—sealed in the bottom of the jar. He identified fatty material that likely was added as a binder, as well as traces of coumarin, a fragrant chemical compound found in plants and used in some perfumes. Further analysis showed small traces of copper, possibly the result of a user dipping a small metal applicator into the container. Other sites in eastern Iran are only now being investigated. For the past two years, Iranian archaeologists Hassan Fazeli Nashli and Hassain Ali Kavosh from the University of Tehran have been digging in a small settlement a few miles east of Shahdad called Tepe Graziani, named for the Italian archaeologist who first surveyed the site. They are trying to understand the role of the city's outer settlements by examining this ancient mound, which is 30 feet high, 525 feet wide, and 720 feet long. Excavators have uncovered a wealth of artifacts including a variety of small sculptures depicting crude human figures, humped bulls, and a Bactrian camel dating to approximately 2900 B.C. A bronze mirror, fishhooks, daggers, and pins are among the metal finds. There are also wooden combs that survived in the arid climate. "The site is small but very rich," says Fazeli, adding that it may have been a prosperous suburban production center for Shahdad. Sites such as Shahdad and Shahr-i-Sokhta and their suburbs were not simply islands of settlements in what otherwise was empty desert. Fazeli adds that some 900 Bronze Age sites have been found on the Sistan plain, which borders Afghanistan and Pakistan. Mortazavi, meanwhile, has been examining the area around the Bampur Valley, in Iran's extreme southeast. This area was a corridor between the Iranian plateau and the Indus Valley, as well as between Shahr-i-Sokhta to the north and the Persian Gulf to the south. A 2006 survey along the Damin River identified 19 Bronze Age sites in an area of less than 20 square miles. That river periodically vanishes, and farmers depend on underground channels called qanats to transport water. Despite the lack of large rivers, ancient eastern Iranians were very savvy in marshaling their few water resources. Using satellite remote sensing data, Vidale has found remains of what might be ancient canals or qanats around Shahdad, but more work is necessary to understand how inhabitants supported themselves in this harsh climate 5,000 years ago, as they still do today.

Fig. 2 Hematite cylinder seal of Old Syria ca. 1820-1730 BCE

Period: Old Syrian

Date: ca. 1820–1730 B.C.E

Geography: Syria

Medium: Hematite

Dimensions: H. 1 1/16 in. (2.7 cm); Diam. 1/2 in. (1.2 cm)

Classification: Stone-Cylinder Seals

Credit Line: Gift of Nanette B. Kelekian, in memory of Charles Dikran and Beatrice Kelekian, 1999

Accession Number: 1999.325.142 Metmuseum

Fig. 3 Hematite seal. Old Syria. ca. 1720-1650 BCE

Period: Old Syrian

Date: ca. 1720–1650 B.C.E

Geography: Syria

Medium: Hematite

Dimensions: H. 15/16 in. (2.4 cm); Diam. 3/8 in. (1 cm)

Classification: Stone-Cylinder Seals

Credit Line: Gift of Nanette B. Kelekian, in memory of Charles Dikran and Beatrice Kelekian, 1999

Accession Number: 1999.325.155 Metmuseum

Fig. 4 Cylinder seal modern impression. Mitanni. 2nd millennium BCE

(male and griffin demon slaying animal; terminal: animal attack scenes, guilloche)

Period: Mitanni

Date: 2nd millennium B.C.E

Geography: Mesopotamia or Syria

Culture: Mitanni

Medium: Hematite

Dimensions: H. 13/16 in. (2 cm); Diam. 7/16 in. (1.1 cm)

Classification: Stone-Cylinder Seals

Credit Line: Gift of Nanette B. Kelekian, in memory of Charles Dikran and Beatrice Kelekian, 1999

Accession Number: 1999.325.165 Metmuseum

Fig. 5 Cylinder seal modern impression. Old Syria. ca. 1720-1650 BCE

(royal figures approaching weather god; divinities)

Period: Old Syrian

Date: ca. 1720–1650 B.C.E

Geography: Syria

Medium: Hematite

Dimensions: H, 1 1/8 in. (2.9 cm); Diam. 7/16 in. (1.1 cm)

Classification: Stone-Cylinder Seals

Credit Line: Gift of Nanette B. Kelekian, in memory of Charles Dikran and Beatrice Kelekian, 1999

Accession Number: 1999.325.147 Metmuseum

Fig. 6 Cylinder seal. Mitanni. 2nd millennium BCE

Period: Mitanni

Date: ca. late 2nd millennium B.C.E

Geography: Mesopotamia or Syria

Culture: Mitanni

Medium: Hematite

Dimensions: H. 1 in. (2.6 cm); Diam. 1/2 in. (1.2 cm)

Classification: Stone-Cylinder Seals

Credit Line: Gift of Nanette B. Kelekian, in memory of Charles Dikran and Beatrice Kelekian, 1999

Accession Number: 1999.325.190 Metmuseum

Fig. 7 Stone cylinder seal. Old Syria ca. 1720-1650 BCE

Period: Old Syrian

Date: ca. 1720–1650 B.C.

Geography: Syria

Medium: Stone

Dimensions: H. 1.9 cm x Diam. 1.1 cm

Classification: Stone-Cylinder Seals

Credit Line: Bequest of W. Gedney Beatty, 1941

Accession Number: 41.160.189 Metmuseum

Fig. 8 Hematite cylinder seal. Old Syria. ca. early 2nd millennium BCE

Period: Old Syrian

Date: ca. early 2nd millennium B.C.E

Geography: Syria

Medium: Hematite

Dimensions: H. 11/16 in. (1.7 cm); Diam. 5/16 in. (0.8 cm)

Classification: Stone-Cylinder Seals

Credit Line: Gift of Nanette B. Kelekian, in memory of Charles Dikran and Beatrice Kelekian, 1999

Accession Number: 1999.325.161 Metmuseum

![]()

- Fig. 9 Fragment of an Iranian Chlorite Vase. 2500-2400 BCE

- Decorated with the lion headed eagle (Imdugud) found in the temple of Ishtar during the 1933 - 1934 fieldwork by Parrot. Dated 2500 - 2400 BCE. Louvre Museum collection AO 17553.

![]()

Fig. 10 Shahdad standard. ca. 2400 BCE Line drawing

Fig.12 Cylinder seal. Sumerian. 18th cent. BCE. Louvre AO 22366

Fig. 13 Bogazkoy Seal impression ca. 18th cent. BCE

(Two-headed eagle, a twisted cord below. From Bogazköy . 18th c. BCE (Museum Ankara).

Fig. 13 Bogazkoy Seal impression Decipherment:

eruvai 'kite' Rebus: eruvai 'copper' dhAtu 'strands of rope' Rebus: dhAtu 'mineral' (Note the three strands of the rope hieroglyph on the seal impression from Bogazkoy; it is read: tridhAtu 'three mineral elements'). It signifies copper compound of three minerals; maybe, arsenic copper? or arsenic bronze, as distinct from tin bronze?

Sulfide deposits frequently are a mix of different metal sulfides, such as copper, zinc, silver, lead, arsenic and other metals. (Sphalerite (ZnS2), for example, is not uncommon in copper sulfide deposits, and the metal smelted would be brass, which is both harder and more durable than bronze.)The metals could theoretically be separated out, but the alloys resulting were typically much stronger than the metals individually.

| Ore name | Chemical formula |

|---|---|

| Arsenopyrite | FeAsS |

| Enargite | Cu3AsS4 |

| Olivenite | Cu2(AsO4)OH |

| Tennantite | Cu12As4S13 |

| Malachite | Cu2(OH)2CO3 |

| Azurite | Cu3(OH)2(CO3)2 |

Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/nuceor7

Dudu plaque ca. 2400 BCE signifies sanga of Ningirsu.

Shahdad standard ca. 2400 BCE signifies dhāvaḍ 'iron-smelters'. (Note: the gloss explains the place name Dharwar close to the iron ore mines in Deccan Plateau of India).

The continuum of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization in an extensive civilizational contact area from 3rd millennium BCE and the metalwork competence of Bhāratam Janam is explained by this link of Dharwar city of Karnataka to the artifacts of over 4000 years Before Present found in Ancient Near East (Sumer/Elam/Mesopotamia). This is a moment for celebration of Dharwar and Shahdad as twin cities from ancient Bronze Age times.

Both artifacts -- Dudu plaque and Shahdad standard -- signify a three-stranded twisted rope hieroglyph, (together with other metalwork signifying hieroglyphs). The hieroglyph-multiplexes on both artifacts signify workers with tridhātu 'three minerals (metals of soft red stones)'.

These inscribed artifacts herald a Bronze Age advance into the Iron Age of Ancient Iran. The language used to render the Indus Script cipher is Proto-Prakritam. No wonder, speakers of Proto-Prakritam were present in Ancient Iran.

sanga 'priest' is a loanword in Sumerian/Akkadian. The presence of such a sanga may also explain Gudea as an Assur, in the tradition of ancient metalworkers speaking Proto-Prakritam of Indian sprachbund.

The Sumerian/Akkadian word sanga, is a loan from Proto-Prakritam or Meluhha of Indian sprachbund. saṁghapati m. ʻ chief of a brotherhood ʼ Śatr. [

Pa. saṅgha -- m. ʻ assembly, the priesthood ʼ; Aś. saṁgha -- m. ʻ the Buddhist community ʼ; Pk. saṁgha -- m. ʻ assembly, collection ʼ; OSi. (Brāhmī inscr.) saga, Si. san̆ga ʻ crowd, collection ʼ. -- Rather <

dhātu (f.) [Sk. dhātu to dadhāti, Idg. *dhē, cp. Gr. ti/qhmi, a)na/ -- qhma , Sk. dhāman, dhāṭr (=Lat. conditor); Goth. gadēds; Ohg. tāt, tuom (in meaning -- ˚=dhātu, cp. E. serf -- dom "condition of . . .") tuon=E. to do; & with k -- suffix Lat. facio, Gr. (e)/ )qhk (a ), Sk. dhāka; see also dhamma] element... -- kusala skilled in the elements M iii. 62; ˚kusalatā proficiency in the (18) elements D iii. 212; Dhs 1333; -- ghara "house for a relic," a dagoba SnA 194. -- cetiya a shrine over a relic DhA iii. 29 (Pali)

Ti˚ [Vedic tris, Av. priś, Gr. tri/s , Lat. ter (fr. ters>*tris, cp. testis>*tristo, trecenti>*tricenti), Icl. prisvar, Ohg. driror] base of numeral three in compn ; consisting of three, threefold; in numerical cpds. also= three (3 times)...-- vidha 3 fold, of sacrifice (yañña) D i. 128, 134, 143; of aggi (fire) J i. 4 & Miln 97; Vism 147 (˚kalyāṇatā). (Pali)

Hieroglyph: 'three strands of rope': tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV (CDIAL 6283) ti-dhātu (Proto-Prakritam, Meluhha) signifies three elements (minerals of 'soft red stones').The Meluhha glosses: dhāū, dhāv connote a soft red stone. (See cognate etyma of Indian sprachbund appended).

I suggest that the 'twist' hieroglyphs on Dudu plaque and on Shahdad standard signify ti-dhātu 'three strands of rope' Rebus: ti-dhātu 'three minerals'. The dhā- suffix signifies 'elements, minerals': dhāvaḍ 'iron-smelters'. dhāvḍī ʻcomposed of or relating to ironʼ. Thus, the hieroglyph 'twist' is signified by the Proto-Prakritam gloss: ti-dhātu semantically 'three metal/mineral elements.' Thus Dudu, sanga of Ningirsu and the sanga 'priest' shown on Shahdad standard can be identified as dhāvaḍ 'iron (metal)-smelters'.

This decipherment is consistent with other hieroglyphs shown the Dudu plaque and on Shahdad standard.

![]() Location of Lagash. At the time of Hammurabi, Lagash was located near the shoreline of the gulf.

Location of Lagash. At the time of Hammurabi, Lagash was located near the shoreline of the gulf.

![]() Location of Shahdad

Location of Shahdad

![]() Oldest standard in the world. Shahdad standard, 2400 BCE (Prof. Mahmoud Rexa Maheri, Prof. Dept. of Civil Engineering, Shiraz University, dates this to ca. 3000 BCE Oct. 15, 2015 "Following an archeological survey of the South-East Iran in 1930's by Sir Auriel Stein, in 1960's and 1970's a number of archeological expeditions spent a few seasons digging at different locations through the

Oldest standard in the world. Shahdad standard, 2400 BCE (Prof. Mahmoud Rexa Maheri, Prof. Dept. of Civil Engineering, Shiraz University, dates this to ca. 3000 BCE Oct. 15, 2015 "Following an archeological survey of the South-East Iran in 1930's by Sir Auriel Stein, in 1960's and 1970's a number of archeological expeditions spent a few seasons digging at different locations through the![]()

![]()

The upper section of the Shahdad Standard, grave No. 114, Object No. 1049 (p.24)

Three pots are shown of three sizes in the context of kneeling adorants seated in front of the person seated on a stool. meṇḍā 'kneeling position' (Gondi) Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Munda)

eruvai 'kite' Rebus:eruvai 'copper'

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'

arya 'lion' (Akkadian) Rebus: Ara 'brass'

kul, kOla 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'

poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'

kōla = woman (Nahali) Rebus: kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five

metals, pañcaloha’ (Tamil) kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil)

kaṇḍō a stool. Malt. Kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) Rebus: kaṇḍ = a furnace,

kaṇḍō a stool. Malt. Kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) Rebus: kaṇḍ = a furnace,

altar (Santali)

If the date palm denotes tamar (Hebrew language), ‘palm tree, date palm’ the rebus reading would be: tam(b)ra, ‘copper’ (Pkt.)

If the date palm denotes tamar (Hebrew language), ‘palm tree, date palm’ the rebus reading would be: tam(b)ra, ‘copper’ (Pkt.)

a rectangle with ten square divisions and a dot in each square. The dot may

denote an ingot in a furnace mould.

Hieroglyph: BHSk. gaṇḍa -- m. ʻ piece, part ʼ(CDIAL 3791)

Hieroglyph: Paš. lauṛ. khaṇḍā ʻ cultivated field ʼ, °ḍī ʻ small do. ʼ (→ Par. kheṇ ʻ field ʼ IIFL i 265); Gaw. khaṇḍa ʻ hill pasture ʼ (see also bel.)(CDIAL 3792)

Rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements'

Santali glosses

Santali glossesGlyph of rectangle with divisions: baṭai = to divide, share (Santali) [Note the

glyphs of nine rectangles divided.] Rebus: bhaṭa = an oven, kiln, furnace

Twisted rope as hieroglyph:

Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn.Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ)(CDIAL 6773).

![File:Relief Dudu Louvre AO2394.jpg]()

- Votive relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu, in the days of King Entemena of Lagash.

- Mésopotamie, room 1a: La Mésopotamie du Néolithique à l'époque des Dynasties archaïques de Sumer. Richelieu, ground floor.

This work is part of the collections of the Louvre (Department of Near Eastern Antiquities).Louvre Museum: excavated by Ernest de Sarzec. Place: Girsu (modern city of Telloh, Iraq). Musée du Louvre, Atlas database: entry 11378 Votive relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu, in the days of King Entemena of Lagash. Oil shale, ca. 2400 BC. Found in Telloh, ancient city of Girsu. |H. 25 cm (9 ¾ in.), W. 23 cm (9 in.), D. 8 cm (3 in.) - Votive bas-relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu in the time of Entemena, prince of Lagash C. 2400 BCE Tello (ancient Girsu) Bituminous stone H. 25 cm; W. 23 cm; Th. 8 cm De Sarzec excavations, 1881 AO 2354

- Hieroglyph: dhA 'rope strand' Rebus: dhAtu 'mineral element' Alternative: मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' (Marathi) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) eruvai 'eagle'

- Rebus: eruvai 'copper'.

- eraka 'wing' Rebus: erako 'moltencast copper'.

- Plaques perforated in the center and decorated with scenes incised or carved in relief were particularly widespread in the 2nd and 3rd Early Dynastic Periods (2800-2340 BC), and have been found at many sites in Mesopotamian and more rarely in Syria or Iran. The perforated plaque of Dudu, high priest of Ningirsu in the reign of Entemena, prince of Lagash (c.2450 BC), belongs to this tradition. It has some distinctive features, however, such as being made of bitumen.

Dudu, priest of Ningirsu

The bas-relief is perforated in the middle and divided into four unequal sections. A figure occupying the height of two registers faces right, leaning on what appears to be a long staff. He is dressed in the kaunakes, a skirt of sheepskin or other material tufted in imitation of it. His name is inscribed alongside: Dudu, rendered by the pictograph for the foot, "du," repeated. Dudu was high priest of the god Ningirsu at the time of Entemena, prince of Lagash (c.2450 BC). Incised to his left is the lion-headed eagle, symbol of the god Ningirsu and emblem of Lagash, as found in other perforated plaques from Telloh, as well as on other objects such as the mace head of Mesilim, king of Kish, and the silver vase of Entemena, king of Lagash. On this plaque, however, the two lions, usually impassive, are reaching up to bite the wings of the lion-headed eagle. Lower down is a calf, lying in the same position as the heifers on Entemena's vase. The lower register is decorated with a plait-like motif, according to some scholars a symbol of running water.Perforated plaques

This plaque belongs to the category of perforated plaques, widespread throughout Phases I and II of the Early Dynastic Period, c.2800-2340 BCE, and found at many sites in Mesopotamia (especially in the Diyala region), and more rarely in Syria (Mari) and Iran (Susa). Some 120 examples are known, of which about 50 come from religious buildings. These plaques are usually rectangular in form, perforated in the middle and decorated with scenes incised or carved in relief. They are most commonly of limestone or gypsum: this plaque, being of bitumen, is an exception to the rule.Bibliography

André B, Naissance de l'écriture : cunéiformes et hiéroglyphes, (notice), Paris, Exposition du Grand Palais, 7 mai au 9 août 1982, Paris, Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1982, p. 85, n 42.Contenau G., Manuel d'archéologie orientale, Paris, Picard, 1927, p. 487, fig. 357.Heuzey L., Les Antiquités chaldéennes, Paris, Librairie des Imprimeries Réunies, 1902, n 12.Orthmann W., Der Alte Orient, Berlin, Propylaën (14), 1975, pl. 88. Sarzec É., Découvertes en Chaldée, Paris, Leroux, 1884-1912, pp. 204-209.Thureau-Dangin, Les inscriptions de Sumer et d'Akkad, Paris, Leroux, 1905, p. 59.

The image may be read as a series of rebuses or ideograms. A priest dedicates an object to his god, represented by his symbol, and flanked perhaps by representations of sacrificial offerings: an animal for slaughter and a libation of running water. The dedicatory inscription, confined to the area left free by the image in the upper part , runs over the body of the calf: "For Ningirsu of the Eninnu, Dudu, priest of Ningirsu ... brought [this material] and fashioned it as a mace stand." See alternative readings provided for the 'twist' hieroglyph. Maybe, the calf is NOT an animal for slaughter but a gloss which sounds similar to the name of the sanga, 'priest': Dudu. The calf is called dUDa (Indian sprachbund). It may also have sounded: dāmuri ʻcalfʼ evoking the rebus of dAv 'strands of rope' rebus: dhAtu 'mineral elements'.

The precise function of such plaques is unknown, and the purpose of the central perforation remains a mystery. The inscription here at first led scholars to consider them as mace stands, which seems unlikely. Some have thought they were to be hung on a wall, the hole in the center taking a large nail or peg. Others have suggested they might be part of a door-closing mechanism. Perforated plaques such as this are most commonly organized in horizontal registers, showing various ceremonies, banquets (particularly in the Diyala), the construction of buildings (as in the perforated plaque of Ur-Nanshe), and scenes of cultic rituals (as in the perforated plaque showing "the Libation to the Goddess of Fertility"). The iconography is often standardized, almost certainly an indication that they represent a common culture covering the whole of Mesopotamia, and that they had a specific significance understood by all." http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/perforated-plaque-dudu- Perforated plaque of Dudu with 'twisted rope' and other Indus Script hieroglyphsI suggest that the hieroglyphs on the Dudu plaque are: eagle, pair of lions, twisted rope, calfHieroglyph: eruvai 'kite' Rebus: eruvai 'copper'Hieroglyph: arye 'lion' (Akkadian) Rebus: Ara 'brass'Hieroglyph: dām m. ʻ young ungelt ox ʼ: damya ʻ tameable ʼ, m. ʻ young bullock to be tamed ʼ Mn. [~ *

dāmiya -- . -- √dam ]Pa. damma -- ʻ to be tamed (esp. of a young bullock) ʼ; Pk. damma -- ʻ to be tamed ʼ; S. ḍ̠amu ʻ tamed ʼ; -- ext. -- ḍa -- : A. damrā ʻ young bull ʼ, dāmuri ʻ calf ʼ; B.dāmṛā ʻ castrated bullock ʼ; Or. dāmaṛī ʻ heifer ʼ, dāmaṛiā ʻ bullcalf, young castrated bullock ʼ, dāmuṛ, °ṛi ʻ young bullock ʼ.Addenda: damya -- : WPah.kṭg. dām m. ʻ young ungelt ox ʼ.(CDIAL 6184). This is a phonetic determinative of the 'twisted rope' hieroglyph: dhāī˜ f.dāˊman1 ʻ rope ʼ (Rigveda)Dudu, sanga priest of Ningirsu, dedicatory plaque with image of Anzud (Imdugud) ![]() Fig. 14 Dudu plaque. Votive bas-relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu in the time of Entemena, prince of Lagash, ca. 2400 BCE Tello (ancient Girsu)

Fig. 14 Dudu plaque. Votive bas-relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu in the time of Entemena, prince of Lagash, ca. 2400 BCE Tello (ancient Girsu) - Bituminous stoneH. 25 cm; W. 23 cm; Th. 8 cm

- De Sarzec excavations, 1881 , 1881AO 2354

![]()

- Anzud with two lions.

- Hieroglyph: endless knot motifAfter Fig. 52, p.85 in Prudence Hopper opcit. Plaque with male figures, serpents and quadruped. Bitumen compound. H. 9 7/8 in (25 cm); w. 8 ½ in. (21.5 cm); d. 3 3/8 in. (8.5 cm). ca. 2600-2500 BCE. Acropole, temple of Ninhursag Sb 2724. The scene is described: “Two beardless, long-haired, nude male figures, their heads in profile and their bodies in three-quarter view, face the center of the composition…upper centre, where two intertwined serpents with their tails in their mouths appear above the upraised hands. At the base of the plaque, between the feet of the two figures, a small calf or lamb strides to the right. An irregular oblong cavity or break was made in the centre of the scene at a later date.”The hieroglyphs on this plaque are: kid and endless-knot motif (or three strands of rope twisted).Hieroglyph: 'kid': करडूं or करडें (p. 137) [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly

करडूं ) A kid. Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c.(Marathi)I suggest that the center of the composition is NOT set of intertwined serpents, but an endless knot motif signifying a coiled rope being twisted from three strands of fibre.

Twisted rope as hieroglyph on a plaque.

Twisted rope as hieroglyph on a plaque. Alternative hieroglyph: मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' (Marathi) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) eruvai 'eagle' Rebus: eruvai 'copper'. kōḍe, kōḍiya. [Tel.] n. A bullcalf. Rebus: koḍ artisan’s workshop (Kuwi) kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (Assamese) मेढा [ mēḍhā ] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl.(Marathi)(CDIAL 10312).L. meṛh f. ʻrope tying oxen to each other and to post on threshing floorʼ(CDIAL 10317) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)

A stranded rope as a hieroglyph signifies dhAtu rebus metal, mineral, ore. This occurs on Ancient Near East objects with hieroglyphs such as votive bas-relief of Dudu, priest of Ningirsu in the time of Entemena, prince of Lagash C. 2400 BCE Tello (ancient Girsu), eagle and stranded rope from Bogazhkoy. Indus Script decipherment of these hieroglyph-multiplexes confirms the underlying Prakritam as an Indo-European language and Indus Script Corpora is emphatically catalogus catalogorum of metalwork of the Bronze Age in Ancient Near East.

Hieroglyph: धातु [p= 513,3] m. layer , stratum Ka1tyS3r. Kaus3. constituent part , ingredient (esp. [ and in RV. only] ifc. , where often = " fold " e.g. त्रि-ध्/आतु , threefold &c ; cf.त्रिविष्टि- , सप्त- , सु-) RV. TS. S3Br. &c (Monier-Williams) dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.).; S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)

Rebus: M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; (CDIAL 6773) धातु primary element of the earth i.e. metal , mineral, ore (esp. a mineral of a red colour) Mn. MBh. &c element of words i.e. grammatical or verbal root or stem Nir. Pra1t. MBh. &c (with the southern Buddhists धातु means either the 6 elements [see above] Dharmas. xxv ; or the 18 elementary spheres [धातु-लोक] ib. lviii ; or the ashes of the body , relics L. [cf. -गर्भ]) (Monier-Williams. Samskritam)

There are two Railway stations in India called Dharwad and Ib. Both are related to Prakritam words with the semantic significance: iron worker, iron ore.

dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ (Marathi)(CDIAL 6773)

ib 'iron' (Santali) karba 'iron'; ajirda karba 'native metal iron' (Tulu) karabha 'trunk of elephant' Rebus: karba 'iron' ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron ore' (Santali) The gloss ajirda (Tulu) is cognate with aduru, ayas. Hence, it is likely that the gloss ayas of Rigveda signifies native, unsmelted metal of iron ore.![]() Glazed steatite . Cylinder seal. 3.4cm high; imported from Indus valley. Rhinoceros, elephant, crocodile (lizard? ).Tell Asmar (Eshnunna), Iraq. Elephant, rhinoceros, crocodile hieroglyphs: ib 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron' kANDa 'rhinoceros' Rebus: kANDa 'iron implements' karA 'crocodile' Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

Glazed steatite . Cylinder seal. 3.4cm high; imported from Indus valley. Rhinoceros, elephant, crocodile (lizard? ).Tell Asmar (Eshnunna), Iraq. Elephant, rhinoceros, crocodile hieroglyphs: ib 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron' kANDa 'rhinoceros' Rebus: kANDa 'iron implements' karA 'crocodile' Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

Located on the Map of India are regions with Fe (Iron ore) mines: the locations include Dharwad and Ib.

Dharwad is the district headquarters of Dharwad district in the state of Karnataka, India. It was merged with the city of Hubli in 1961 to form the twin cities of Hubli-Dharwad. It covers an area of 200.23 km² and is located 425 km northwest of Bengaluru, onNH 4, between Bengaluru and Pune...The word "Dharwad" means a place of rest in a long travel or a small habitation. For centuries, Dharwad acted as a gateway between the Malenaadu (western mountains) and the Bayalu seeme (plains) and it became a resting place for travellers. Inscriptions found near Durga Devi temple in Narendra (a nearby village) and RLS High School date back to the 12th century and have references to Dharwad. This makes Dharwad at least 900 years old. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dharwad The place is located in the region of hematite (iron ore) -- e.g. Sandur taluk

The station derives its name from Ib River flowing nearby. Ib railway station came up with the opening of the Nagpur-Asansol main line of Bengal Nagpur Railway in 1891. It became a station on the crosscountry Howrah-Nagpur-Mumbai line in 1900 In 1900, when Bengal Nagpur Railway was building a bridge across the Ib River, coal was accidentally discovered in what later became Ib Valley Coalfield. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ib_railway_station

dhAtu is a gloss which signifies metal, mineral, ore. It is likely that in early Bronze Age, the mineral specifically referred to is iron ore or meteoric iron as naturally occurring native, unsmelted metal called aduru, ayas. A gloss dhāvaḍ has the meaning: iron smelters. This gloss derived rom dhAtu can be explained in an archaeometallurgical context with evidences from Indus Script Corpora.

This suggestion is premised on a Marathi gloss (Prakritam, Meluhha pronunciation) cognate with dhAtu: dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻa partic. soft red stoneʼ (Marathi)

This note suggests that the place names in India of Dharwad and Ib are related to nearby iron ore regions and lived in by iron workers. The names are derived from two etyma streams: 1 dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ

(whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron -- smeltersʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ 2. ib 'iron' kara +iba, karba 'iron'. For example, the place name Dharwad is relatable to dhāvaḍ 'iron-smelters'. Archaeological explorations near Dharwad and Ib may indicate evidences for iron smelting.

This etymon indicates the possible reading of the tall flagpost carried by kneeling persons with six locks of hair: baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'. Associated with nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

This etymon indicates the possible reading of the tall flagpost carried by kneeling persons with six locks of hair: baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'. Associated with nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'The banner flagpost carried by four flag-bearers includes a banner associated with fish. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati) ayas 'metal' (Rigveda) http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/indus-script-unravels-announcement-of.html presents the picture of a 11-ft tall banner from Girsu (Telloh)

Red jasper H. 1 1/8 in. (2.8 cm), Diam. 5/8 in. (1.6 cm) cylinder Seal with four hieroglyphs and four kneeling persons (with six curls on their hair) holding flagposts, c. 2220-2159 B.C.E., Akkadian (Metropolitan Museum of Art) Cylinder Seal (with modern impression). The four hieroglyphs are: from l. to r. 1. crucible PLUS storage pot of ingots, 2. sun, 3. narrow-necked pot with overflowing water, 4. fish A hooded snake is on the edge of the composition. (The dark red color of jasper reinforces the semantics: eruvai 'dark red, copper' Hieroglyph: eruvai 'reed'; see four reedposts held.

If the hieroglyph on the leftmost is moon, a possible rebus reading: قمر ḳamar

A قمر ḳamar, s.m. (9th) The moon. Sing. and Pl. See سپوږمي or سپوګمي (Pashto) Rebus: kamar 'blacksmith'

Situated at the end of a small delta on a dry plain, Shahdad was excavated by an Iranian team in the 1970s. (Courtesy Maurizio Tosi)

Situated at the end of a small delta on a dry plain, Shahdad was excavated by an Iranian team in the 1970s. (Courtesy Maurizio Tosi)  An Iranian-Italian team, including archaeologist Massimo Vidale (right), surveyed the site in 2009. (Courtesy Massimo Vidale) The peripatetic English explorer Sir Aurel Stein, famous for his archaeological work surveying large swaths of Central Asia and the Middle East, slipped into Persia at the end of 1915 and found the first hints of eastern Iran's lost cities. Stein traversed what he described as "a big stretch of gravel and sandy desert" and encountered "the usual...robber bands from across the Afghan border, without any exciting incident." What did excite Stein was the discovery of what he called "the most surprising prehistoric site" on the eastern edge of the Dasht-e Lut. Locals called it Shahr-i-Sokhta ("Burnt City") because of signs of ancient destruction. It wasn't until a half-century later that Tosi and his team hacked their way through the thick salt crust and discovered a metropolis rivaling those of the first great urban centers in Mesopotamia and the Indus. Radiocarbon data showed that the site was founded around 3200 B.C., just as the first substantial cities in Mesopotamia were being built, and flourished for more than a thousand years. During its heyday in the middle of the third millennium B.C., the city covered more than 150 hectares and may have been home to more than 20,000 people, perhaps as populous as the large cities of Umma in Mesopotamia and Mohenjo-Daro on the Indus River. A vast shallow lake and wells likely provided the necessary water, allowing for cultivated fields and grazing for animals. Built of mudbrick, the city boasted a large palace, separate neighborhoods for pottery-making, metalworking, and other industrial activities, and distinct areas for the production of local goods. Most residents lived in modest one-room houses, though some were larger compounds with six to eight rooms. Bags of goods and storerooms were often "locked" with stamp seals, a procedure common in Mesopotamia in the era. Shahr-i-Sokhta boomed as the demand for precious goods among elites in the region and elsewhere grew. Though situated in inhospitable terrain, the city was close to tin, copper, and turquoise mines, and lay on the route bringing lapis lazuli from Afghanistan to the west. Craftsmen worked shells from the Persian Gulf, carnelian from India, and local metals such as tin and copper. Some they made into finished products, and others were exported in unfinished form. Lapis blocks brought from the Hindu Kush mountains, for example, were cut into smaller chunks and sent on to Mesopotamia and as far west as Syria. Unworked blocks of lapis weighing more than 100 pounds in total were unearthed in the ruined palace of Ebla, close to the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeologist Massimo Vidale of the University of Padua says that the elites in eastern Iranian cities like Shahr-i-Sokhta were not simply slaves to Mesopotamian markets. They apparently kept the best-quality lapis for themselves, and sent west what they did not want. Lapis beads found in the royal tombs of Ur, for example, are intricately carved, but of generally low-quality stone compared to those of Shahr-i-Sokhta. Pottery was produced on a massive scale. Nearly 100 kilns were clustered in one part of town and the craftspeople also had a thriving textile industry. Hundreds of wooden spindle whorls and combs were uncovered, as were well-preserved textile fragments made of goat hair and wool that show a wide variation in their weave. According to Irene Good, a specialist in ancient textiles at Oxford University, this group of textile fragments constitutes one of the most important in the world, given their great antiquity and the insight they provide into an early stage of the evolution of wool production. Textiles were big business in the third millennium B.C., according to Mesopotamian texts, but actual textiles from this era had never before been found.

An Iranian-Italian team, including archaeologist Massimo Vidale (right), surveyed the site in 2009. (Courtesy Massimo Vidale) The peripatetic English explorer Sir Aurel Stein, famous for his archaeological work surveying large swaths of Central Asia and the Middle East, slipped into Persia at the end of 1915 and found the first hints of eastern Iran's lost cities. Stein traversed what he described as "a big stretch of gravel and sandy desert" and encountered "the usual...robber bands from across the Afghan border, without any exciting incident." What did excite Stein was the discovery of what he called "the most surprising prehistoric site" on the eastern edge of the Dasht-e Lut. Locals called it Shahr-i-Sokhta ("Burnt City") because of signs of ancient destruction. It wasn't until a half-century later that Tosi and his team hacked their way through the thick salt crust and discovered a metropolis rivaling those of the first great urban centers in Mesopotamia and the Indus. Radiocarbon data showed that the site was founded around 3200 B.C., just as the first substantial cities in Mesopotamia were being built, and flourished for more than a thousand years. During its heyday in the middle of the third millennium B.C., the city covered more than 150 hectares and may have been home to more than 20,000 people, perhaps as populous as the large cities of Umma in Mesopotamia and Mohenjo-Daro on the Indus River. A vast shallow lake and wells likely provided the necessary water, allowing for cultivated fields and grazing for animals. Built of mudbrick, the city boasted a large palace, separate neighborhoods for pottery-making, metalworking, and other industrial activities, and distinct areas for the production of local goods. Most residents lived in modest one-room houses, though some were larger compounds with six to eight rooms. Bags of goods and storerooms were often "locked" with stamp seals, a procedure common in Mesopotamia in the era. Shahr-i-Sokhta boomed as the demand for precious goods among elites in the region and elsewhere grew. Though situated in inhospitable terrain, the city was close to tin, copper, and turquoise mines, and lay on the route bringing lapis lazuli from Afghanistan to the west. Craftsmen worked shells from the Persian Gulf, carnelian from India, and local metals such as tin and copper. Some they made into finished products, and others were exported in unfinished form. Lapis blocks brought from the Hindu Kush mountains, for example, were cut into smaller chunks and sent on to Mesopotamia and as far west as Syria. Unworked blocks of lapis weighing more than 100 pounds in total were unearthed in the ruined palace of Ebla, close to the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeologist Massimo Vidale of the University of Padua says that the elites in eastern Iranian cities like Shahr-i-Sokhta were not simply slaves to Mesopotamian markets. They apparently kept the best-quality lapis for themselves, and sent west what they did not want. Lapis beads found in the royal tombs of Ur, for example, are intricately carved, but of generally low-quality stone compared to those of Shahr-i-Sokhta. Pottery was produced on a massive scale. Nearly 100 kilns were clustered in one part of town and the craftspeople also had a thriving textile industry. Hundreds of wooden spindle whorls and combs were uncovered, as were well-preserved textile fragments made of goat hair and wool that show a wide variation in their weave. According to Irene Good, a specialist in ancient textiles at Oxford University, this group of textile fragments constitutes one of the most important in the world, given their great antiquity and the insight they provide into an early stage of the evolution of wool production. Textiles were big business in the third millennium B.C., according to Mesopotamian texts, but actual textiles from this era had never before been found. A metal flag found at Shahdad, one of eastern Iran's early urban sites, dates to around 2400 B.C. The flag depicts a man and woman facing each other, one of the recurrent themes in the region's art at this time. (Courtesy Maurizio Tosi)

A metal flag found at Shahdad, one of eastern Iran's early urban sites, dates to around 2400 B.C. The flag depicts a man and woman facing each other, one of the recurrent themes in the region's art at this time. (Courtesy Maurizio Tosi)  This plain ceramic jar, found recently at Shahdad, contains residue of a white cosmetic whose complex formula is evidence for an extensive knowledge of chemistry among the city's ancient inhabitants. (Courtesy Massimo Vidale) The artifacts also show the breadth of Shahr-i-Sokhta's connections. Some excavated red-and-black ceramics share traits with those found in the hills and steppes of distant Turkmenistan to the north, while others are similar to pots made in Pakistan to the east, then home to the Indus civilization. Tosi's team found a clay tablet written in a script called Proto-Elamite, which emerged at the end of the fourth millennium B.C., just after the advent of the first known writing system, cuneiform, which evolved in Mesopotamia. Other such tablets and sealings with Proto-Elamite signs have also been found in eastern Iran, such as at Tepe Yahya. This script was used for only a few centuries starting around 3200 B.C. and may have emerged in Susa, just east of Mesopotamia. By the middle of the third millennium B.C., however, it was no longer in use. Most of the eastern Iranian tablets record simple transactions involving sheep, goats, and grain and could have been used to keep track of goods in large households. While Tosi's team was digging at Shahr-i-Sokhta, Iranian archaeologist Ali Hakemi was working at another site, Shahdad, on the western side of the Dasht-e Lut. This settlement emerged as early as the fifth millennium B.C. on a delta at the edge of the desert. By the early third millennium B.C., Shahdad began to grow quickly as international trade with Mesopotamia expanded. Tomb excavations revealed spectacular artifacts amid stone blocks once painted in vibrant colors. These include several extraordinary, nearly life-size clay statues placed with the dead. The city's artisans worked lapis lazuli, silver, lead, turquoise, and other materials imported from as far away as eastern Afghanistan, as well as shells from the distant Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. Evidence shows that ancient Shahdad had a large metalworking industry by this time. During a recent survey, a new generation of archaeologists found a vast hill—nearly 300 feet by 300 feet—covered with slag from smelting copper. Vidale says that analysis of the copper ore suggests that the smiths were savvy enough to add a small amount of arsenic in the later stages of the process to strengthen the final product. Shahdad's metalworkers also created such remarkable artifacts as a metal flag dating to about 2400 B.C. Mounted on a copper pole topped with a bird, perhaps an eagle, the squared flag depicts two figures facing one another on a rich background of animals, plants, and goddesses. The flag has no parallels and its use is unknown. Vidale has also found evidence of a sweet-smelling nature. During a spring 2009 visit to Shahdad, he discovered a small stone container lying on the ground. The vessel, which appears to date to the late fourth millennium B.C., was made of chlorite, a dark soft stone favored by ancient artisans in southeast Iran. Using X-ray diffraction at an Iranian lab, he discovered lead carbonate—used as a white cosmetic—sealed in the bottom of the jar. He identified fatty material that likely was added as a binder, as well as traces of coumarin, a fragrant chemical compound found in plants and used in some perfumes. Further analysis showed small traces of copper, possibly the result of a user dipping a small metal applicator into the container. Other sites in eastern Iran are only now being investigated. For the past two years, Iranian archaeologists Hassan Fazeli Nashli and Hassain Ali Kavosh from the University of Tehran have been digging in a small settlement a few miles east of Shahdad called Tepe Graziani, named for the Italian archaeologist who first surveyed the site. They are trying to understand the role of the city's outer settlements by examining this ancient mound, which is 30 feet high, 525 feet wide, and 720 feet long. Excavators have uncovered a wealth of artifacts including a variety of small sculptures depicting crude human figures, humped bulls, and a Bactrian camel dating to approximately 2900 B.C. A bronze mirror, fishhooks, daggers, and pins are among the metal finds. There are also wooden combs that survived in the arid climate. "The site is small but very rich," says Fazeli, adding that it may have been a prosperous suburban production center for Shahdad. Sites such as Shahdad and Shahr-i-Sokhta and their suburbs were not simply islands of settlements in what otherwise was empty desert. Fazeli adds that some 900 Bronze Age sites have been found on the Sistan plain, which borders Afghanistan and Pakistan. Mortazavi, meanwhile, has been examining the area around the Bampur Valley, in Iran's extreme southeast. This area was a corridor between the Iranian plateau and the Indus Valley, as well as between Shahr-i-Sokhta to the north and the Persian Gulf to the south. A 2006 survey along the Damin River identified 19 Bronze Age sites in an area of less than 20 square miles. That river periodically vanishes, and farmers depend on underground channels called qanats to transport water. Despite the lack of large rivers, ancient eastern Iranians were very savvy in marshaling their few water resources. Using satellite remote sensing data, Vidale has found remains of what might be ancient canals or qanats around Shahdad, but more work is necessary to understand how inhabitants supported themselves in this harsh climate 5,000 years ago, as they still do today.

This plain ceramic jar, found recently at Shahdad, contains residue of a white cosmetic whose complex formula is evidence for an extensive knowledge of chemistry among the city's ancient inhabitants. (Courtesy Massimo Vidale) The artifacts also show the breadth of Shahr-i-Sokhta's connections. Some excavated red-and-black ceramics share traits with those found in the hills and steppes of distant Turkmenistan to the north, while others are similar to pots made in Pakistan to the east, then home to the Indus civilization. Tosi's team found a clay tablet written in a script called Proto-Elamite, which emerged at the end of the fourth millennium B.C., just after the advent of the first known writing system, cuneiform, which evolved in Mesopotamia. Other such tablets and sealings with Proto-Elamite signs have also been found in eastern Iran, such as at Tepe Yahya. This script was used for only a few centuries starting around 3200 B.C. and may have emerged in Susa, just east of Mesopotamia. By the middle of the third millennium B.C., however, it was no longer in use. Most of the eastern Iranian tablets record simple transactions involving sheep, goats, and grain and could have been used to keep track of goods in large households. While Tosi's team was digging at Shahr-i-Sokhta, Iranian archaeologist Ali Hakemi was working at another site, Shahdad, on the western side of the Dasht-e Lut. This settlement emerged as early as the fifth millennium B.C. on a delta at the edge of the desert. By the early third millennium B.C., Shahdad began to grow quickly as international trade with Mesopotamia expanded. Tomb excavations revealed spectacular artifacts amid stone blocks once painted in vibrant colors. These include several extraordinary, nearly life-size clay statues placed with the dead. The city's artisans worked lapis lazuli, silver, lead, turquoise, and other materials imported from as far away as eastern Afghanistan, as well as shells from the distant Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. Evidence shows that ancient Shahdad had a large metalworking industry by this time. During a recent survey, a new generation of archaeologists found a vast hill—nearly 300 feet by 300 feet—covered with slag from smelting copper. Vidale says that analysis of the copper ore suggests that the smiths were savvy enough to add a small amount of arsenic in the later stages of the process to strengthen the final product. Shahdad's metalworkers also created such remarkable artifacts as a metal flag dating to about 2400 B.C. Mounted on a copper pole topped with a bird, perhaps an eagle, the squared flag depicts two figures facing one another on a rich background of animals, plants, and goddesses. The flag has no parallels and its use is unknown. Vidale has also found evidence of a sweet-smelling nature. During a spring 2009 visit to Shahdad, he discovered a small stone container lying on the ground. The vessel, which appears to date to the late fourth millennium B.C., was made of chlorite, a dark soft stone favored by ancient artisans in southeast Iran. Using X-ray diffraction at an Iranian lab, he discovered lead carbonate—used as a white cosmetic—sealed in the bottom of the jar. He identified fatty material that likely was added as a binder, as well as traces of coumarin, a fragrant chemical compound found in plants and used in some perfumes. Further analysis showed small traces of copper, possibly the result of a user dipping a small metal applicator into the container. Other sites in eastern Iran are only now being investigated. For the past two years, Iranian archaeologists Hassan Fazeli Nashli and Hassain Ali Kavosh from the University of Tehran have been digging in a small settlement a few miles east of Shahdad called Tepe Graziani, named for the Italian archaeologist who first surveyed the site. They are trying to understand the role of the city's outer settlements by examining this ancient mound, which is 30 feet high, 525 feet wide, and 720 feet long. Excavators have uncovered a wealth of artifacts including a variety of small sculptures depicting crude human figures, humped bulls, and a Bactrian camel dating to approximately 2900 B.C. A bronze mirror, fishhooks, daggers, and pins are among the metal finds. There are also wooden combs that survived in the arid climate. "The site is small but very rich," says Fazeli, adding that it may have been a prosperous suburban production center for Shahdad. Sites such as Shahdad and Shahr-i-Sokhta and their suburbs were not simply islands of settlements in what otherwise was empty desert. Fazeli adds that some 900 Bronze Age sites have been found on the Sistan plain, which borders Afghanistan and Pakistan. Mortazavi, meanwhile, has been examining the area around the Bampur Valley, in Iran's extreme southeast. This area was a corridor between the Iranian plateau and the Indus Valley, as well as between Shahr-i-Sokhta to the north and the Persian Gulf to the south. A 2006 survey along the Damin River identified 19 Bronze Age sites in an area of less than 20 square miles. That river periodically vanishes, and farmers depend on underground channels called qanats to transport water. Despite the lack of large rivers, ancient eastern Iranians were very savvy in marshaling their few water resources. Using satellite remote sensing data, Vidale has found remains of what might be ancient canals or qanats around Shahdad, but more work is necessary to understand how inhabitants supported themselves in this harsh climate 5,000 years ago, as they still do today.

A Proto-Dilmun seal? Source: https://www.academia.edu/7837834/From_rags_to_riches_three_crucial_steps_in_Dilmun_s_rise_to_fame_poster_-_HIGH_RESOLUTION_FIGS._1-4

kolmo 'rice-plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' melh 'goat' Rebus: milakkhu

'copper' bica 'scorpion' Rebus: bica 'laterite' kulA 'hooded serpent' Rebus: kolhe

'smelter'.

![]()

![]() The legs are made of copper. The vase features an image of Anzud (also known as Imdugud), the lion-headed eagle, grasping two lions with his talons.

The legs are made of copper. The vase features an image of Anzud (also known as Imdugud), the lion-headed eagle, grasping two lions with his talons.![]() Detail drawing of the Enmetena vase. Lions kisse the antelopes.

Detail drawing of the Enmetena vase. Lions kisse the antelopes.

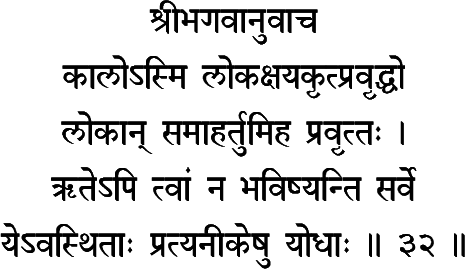

Inscribed vase of silver and copper of Entemena, king of Lagash, with dedication to the god Ningirsu, around 2400 BC, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Found in Telloh, ancient city of Girsu.![]() The dedicatory inscriptions wrap around the neck of the vase:

The dedicatory inscriptions wrap around the neck of the vase:

![]() .

.

Translation of the inscriptions from the CDLI (P222539):

For Ningirsu, the hero of Enlil,

Enmetena, ruler of Lagash,

chosen by the heart of Nanshe,

chief ruler of Ningirsu,

son of Enannatum, ruler of Lagash,

for the king who loved him, Ningirsu,

(this) gurgur-vessel of refined silver,

from which Ningirsu will consume the monthly oil (offering),

he had fashioned for him.

For his life, before Ningirsu of the Eninnu (temple)

he had it set up.

At that time Dudu

was the temple administrator of Ningirsu.