The scintillating insights provided by J. Kharakwal and L Gurjar (2006) in an archaeometallurgical excursus are gratefully acknowledged. (See their monograph on zinc and brass -- excerpts attached in Annex for ready reference).

Thanks to Asko Parpola for the brilliant identification of 'squirrel' hieroglyph in Indus Script Corpora. (www.harappa.com/script/indus-writing.pdf page 128)

Parpola's decipherment of the hieroglyph as aNIl or aNilpiLLai [from caṇilů (Tulu) or variant] (http://www.harappa.com/script/script-indus-parpola.pdf) is, however, refuted. The orthographic identification is accepted but the faith-based decipherment in Tamil language is NOT accepted because there is a gloss in Indian sprachbund (Proto-Prakritam or Meluhha) which -- in mlecchita vikalpa or Meluhha cipher -- signifies a squirrel and also 'pewter or zinc alloy' which is consistent with the semantic and archaeometallurgical context in which hieroglyhs are used in epigraphs of Indus Script as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork, metalcastings.

The Indian sprachbund Proto-Prakritam gloss is: tuttūḍ"squirrel' (Sora) Rebus:

tuth 'blue vitriol or sulphate of copper'(Bengali) A reconstruction of Proto-Prakritam morpheme is NOT attempted as the build-up of the Proto-Prakritam or Meluhha lexis progresses. There are many phonemic variants in Indian languages,

anyone of which could lead to the *Proto-Prakritam etymon. On Nindowari seal, the 'squirrel' hieroglyph is shown together with the hieroglyph-multiplex of 'one-horned young bull' which signifies a 'turner'. It is possible that the tuttha signified rebus by the 'squirrel' hieroglyph is a 'turned' or 'furnaced' copper sulphate which could have yielded 'pewter-zinc alloy' in a distillation resort of the type deployed in Zawar, Rajasthan.

తుత్తినాగము [ tuttināgamu ] tutti-nāgamu. [Chinese.] n. Pewter. Zinc. లోహవిశేషము (Telugu)

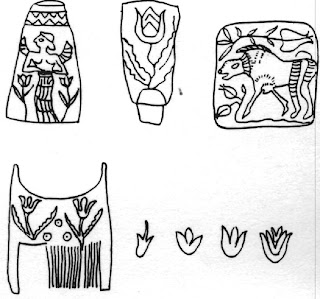

The focus is on the hierolyph: squirrel with variant orthographic representations on three Indus Script inscriptions.

Squirrel hieroglyph of Indus Script: Nindowari seal Nd-1; Mohenjo-daro seal m-1202; Harappa tablet h-771; Harappa tablet h-419

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Nindowari seal Nd-1

Nindowari seal Nd-1

m1202

![]() h771

h771![]() h419

h419

Decipherment of Nd-1 epigraph:

tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy'; dhAL 'slanted stroke' Rebus: dhALako 'large ingot' khANDa 'notch' Rebus: khANDa 'metal implements'; kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'; dula 'two, pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe'; maṇḍā 'warehouse, workshop' (Konkani); koDa 'one' Rebus: koD 'workshop'; aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'. konda 'young bull' Rebus: kondar 'turner' koD 'horn' Rebus: koD 'workshop' sangaDa 'lathe, portable furnace' Rebus: sangar 'fortification' sanghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)

Decipherment of m1202 epigraph:

barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: bharat 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' (Marathi) pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'goldsmith guild'

muhA 'ingot'; dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' muhA 'ingot' (Together, dul muhA 'cast iron ingot'); tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy'; kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe'; aduru 'harrow' Rebus: aduru 'native unsmelted metal';bhaTa 'warrior' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'; kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe'; muhA 'ingot, quantity of iron ore smelted out of the smelter'.

Decipherment of h771:

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' muhA 'ingot' (Together, dul muhA 'cast iron ingot'); tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy'; dula 'two' Rebus: dul 'cast metal or casting'. Thus, the epigraph with three hieroglyph-multiplexes read rebus: metal castings, cast metal ingot, pewter-zinc alloy.

Decipherment of h-419:

tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy'; maṇḍā 'warehouse, workshop' (Konkani)

![]() h723 moulded tablet Harappa dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' muhA 'ingot' (Together, dul muhA 'cast iron ingot'); dula 'two' Rebus: dul 'cast metal, metalcasting'; kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe'

h723 moulded tablet Harappa dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' muhA 'ingot' (Together, dul muhA 'cast iron ingot'); dula 'two' Rebus: dul 'cast metal, metalcasting'; kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe'h669 seal Harappa dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' dhALako 'ingot' (Togethr, dul dhALako 'cast metal ingot'); aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' (Rigveda); kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe'

![]()

Mahadevan concordance Sign 130 variants. This hieroglyph may signify: tutta 'goad' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter-zinc alloy'

Allograph: tutta (goad) (Pali) tṓttra n. ʻ goad for cattle or elephants ʼ ŚBr. [√tud]

Pa. tutta -- n. (with u from tudáti?), Pk. totta -- , tutta<-> n.; Si. tutta ʻ elephant goad ʼ.(CDIAL 5966) It is possible that one of the 500+ 'signs' or hieroglyph-multiplexes of Indus Script Corpora signifies this etymon cluster: tutta 'goad' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter-zinc alloy'. A crook maybe signified by: मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Mu.)

The contribution made in this note is to advance Indus Script decipherment, to relate the excellence in metalwork achieved by metalcasters, Sarasvati's children, Bhāratam janam'metalcaster folk' documented in the Indus Script Corpora, to identify the language they spoke and the technical specifications of metalcastings, metalwork provided in catalogus catalogorum, the Corpora.

The metalcasters of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization were experimenting with many alloys and had also evidenced cire perdue lost-wax casting of exquisite art pieces such as the Mohenjo-daro dancing girl whose gait also becomes a hieroglyph in the Indus Script: meṭṭu 'dance step' Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Ho. Mu.)

meḍ ‘dance’ (Santali) మెట్ట [ meṭṭa ] or మిట్ట meṭṭa. மெட்டு¹-தல் meṭṭu-, v. tr. cf. நெட்டு-. [K. meṭṭu.] To spurn or push with the foot; காலால்தாக்குதல்.நிகளத்தைமெட்டிமெட்டிப்பொடிபடுத்தி (பழனிப்பிள்ளைத். 12). (Tamil)

meṭṭu ‘to put or place down the foot or feet; to step, to pace, to walk (Ka.)

![Image result for bhirrana potsherd]() meḍ ‘dance’ (Santali)

meḍ ‘dance’ (Santali)

Bhirrana potsherd 'dance step' hieroglyph.Glosses of Pashto and Kashmiri signifying sulphate of copper or iron are: توتیا sabz totī-yā, s.f. (6th) Green vitriol, or sulphate of iron.(Pashto) thŏth blue vitriol, sulphate of copper (Kashmiri) Cognate glosses are used in almost all languages of Indian sprachbund.

![]() Indian palm squirrel, Bengaluru, India Funambulus palmarum

Indian palm squirrel, Bengaluru, India Funambulus palmarum

Hieroglyph: tuttūḍ"squirrel' (Sora):So. tuttUD(R) ~ tuttum(R) `squirrel'. Sa. toR `a squirrel (%Sciurus_tristiatus, %Sciurus_palmarum)'.Mu. tuRu `a squirrel (%Sciurus_tristiatus, %Sciurus_palmarum)'.Ho tu `a squirrel (%Sciurus_tristiatus, %Sciurus_palmarum)'.Bh. tuR `a squirrel (%Sciurus_tristiatus, %Sciurus_palmarum)'.KW tu`Ru`Ku. tur `a squirrel (%Sciurus_tristiatus, %Sciurus_palmarum)'.@(V243,M072)(Munda etyma) tarukuTi 'squirrel' (Kannada)

Note: -ūḍ suffix in Sora glosstuttūḍ finds expression in the following etyma:Ta. uṟukku (uṟukki-) to jump, leap over; uṟuttai squirrel. Te. uṟu to retreat, retire, withdraw; uṟuku to jump, run away; uṟuta squirrel. Konḍa uRk- to run away. Kuwi (Isr.) urk- (-it-) to dance.(DEDR 713) Ka. uḍute squirrel. Te. uḍuta id.(DEDR 590) The gloss uruku finds a parallel in Proto-Mon-khmerSee: Thai kra-rook:

412 *prɔɔk squirrel.A: (Bahnaric, Khmuic, Palaungic, Viet-Mương, North & Central Aslian). Sre pro (→ Stieng prɔh?), Chrauprɔːʔ, Biat, Bahnar prɔːk, Jeh proːk (GRADIN & GRADIN 1979), Kammu-Yuan prɔːk, Palaung [ə]prɔʔ(MILNE 1931), Vietnamese [con] sóc, Sakai prōkn (i.e. Semai; SKEAT & BLAGDEN 1906 M 136 (c)); →Lao, Ahom *rook (BENEDICT 1975 226, bat…); Cham, Jarai prɔːʔ, Röglai proʔ, North Röglai proːʔ.Cf. Khmer kɔmprok, apparently < *koːn prɔːk, for which cf. Vietnamese; → Thai krarɔ̂ɔk (with kr- by hypercorrection) at early stage.

http://sealang.net/monkhmer/sidwell2007proto.pdf Sidwell, Paul, Proto-Mon-khmer vocalism: moving on from short's 'alternances'.

Rebus: तुत्थ tuttha [p= 450,2] n. (m. L. ) blue vitriol (used as an eye-ointment) Sus3r.; fire;n. a rock Un2. k. (Monier-Williams) upadhātuḥ उपधातुः An inferior metal, semi-metal. They are seven; सप्तोपधातवः स्वर्णं माक्षिकं तारमाक्षिकम् । तुत्थं कांस्यं च रातिश्च सुन्दूरं च शिलाजतु ॥ (Apte. Samskritam) Ta. turu rust, verdigris, flaw; turucu, turuci blue vitriol, spot, dirt, blemish, stain, defect, rust; turicu fault, crime, sorrow, affliction, perversity, blue vitriol; tukku, tuppu rust. Ma. turiśu blue vitriol; turumpu, turuvu rust. Ka. tukku rust of iron; tutta, tuttu, tutte blue vitriol. Tu. tukků rust; mair(ů)suttu, (Eng.-Tu. Dict.) mairůtuttu blue vitriol. Te. t(r)uppu rust; (SAN) trukku id., verdigris. / Cf. Skt.tuttha- blue vitriol; Turner, CDIAL, no. 5855 (DEDR 3343). tutthá n. (m. lex.), tutthaka -- n. ʻ blue vitriol (used as an eye ointment) ʼ Suśr., tūtaka -- lex. 2. *thōttha -- 4. 3. *tūtta -- . 4. *tōtta -- 2. [Prob. ← Drav. T. Burrow BSOAS xii 381; cf. dhūrta -- 2 n. ʻ iron filings ʼ lex.]1. N. tutho ʻ blue vitriol or sulphate of copper ʼ, B. tuth.2. K. thŏth, dat. °thas m., P. thothā m.3. S. tūtio m., A. tutiyā, B. tũte, Or. tutiā, H. tūtā, tūtiyā m., M. tutiyā m.4. M. totā m.(CDIAL 5855) तुतिया [ tutiyā ] m ( H) Blue vitriol, sulphate of copper.तुत्या [ tutyā ] m An implement of the goldsmith.तोता [ tōtā ] m ( H) (Properly तुतिया) Blue vitriol.(Marathi) <taTia>(M),,<tatia>(P) {N} ``metal ^cup, ^frying_^pan''. *Ho<cele>, H.<kARahi>, Sa.<tutiA> `blue vitriol, bluestone, sulphate of copper',H.<tutIya>. %31451. #31231. Ju<taTia>(M),,<tatia>(P) {N} ``metal ^cup, ^frying_^pan''. *Ho<cele>, H.<kARahi>,Sa.<tutiA> `blue vitriol, bluestone, sulphate of copper', (Munda etyma) S توتیا totī-yā, s.f. (6th) Tutty, protoxyd of zinc. (E.) Sing. and Pl.); (W.) Pl. توتیاوي totīʿāwī. نیل توتیا nīl totī-yā, s.f. (6th) Blue vitriol, sulphate of copper. سبز توتیا sabz totī-yā, s.f. (6th) Green vitriol, or sulphate of iron.(Pashto) thŏth 1 थ्वथ् । कण्टकः, अन्तरायः, निरोध, शिरोवेष्टनवस्त्रम् m. (sg. dat. thŏthas थ्वथस्), blue vitriol, sulphate of copper (cf. nīla-tho, p. 634a, l. 26)(Kashmiri) sattu, satavu, satuvu 'pewter' (Kannada)

Tutanage is the Chinese name for spelter, which we erroneously apply to the metal of which canisters are made, that are brought over with the tea from China. It being a coarse pewter made with the lead carried from England and tin got in the kingdom of Quintang. (John Woodward.)

http://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/?p=5362

tutenaga nickel silver containing about 45 percent copper, with varying proportions of nickel and zinc and often smalleramounts of other metals.(< Marathi tuttināg, allegedly derived from Sanskrit tuttha- sulfate of copper + nāga tin, lead)http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/tutenag

In archaeometallurgical investigations, a copper-nickel-zinc alloy called paktong was traded from China from ca. 4th century. Alfred Bonnin's book Tutenag & Paktong (1924) led to researches which pointd to smelting process used in Southwest China. Another contribution is Keith Pinn, 1999, Paktong: the Chinese alloy in Europe, 1680-1820, Suffolk. Antique Collectors' Club. (See Mei Jianjun's review at http://www.eastm.org/index.php/journal/article/download/305/239) Paktong was used for products such as buckles, salvers, buttons, snuffer stands.Bonnin, Alfred, 1924, Tutenag and Paktong. With notes on other alloys in domestic use during the eighteenth century, Oxford University Press, Humphrey Milford. Bonnin notes that tutenag or paktong referred to a brittle white metal or alloy which was used in place of silver in the 18th century for fireplaces, fenders and candlesticks.

"...doubtful is the etymology of the Turkish birinj (brass and bronze!) from the Sanskrit vrIhi and the Greek oryza, bryza, because brass has the gloss of polished rice! The general Persian term for zinc ores and zinc oxide is tutiya, which occurs frequently in medieval literature as tutia or totia! Laufer has suggested that the Chinese t'ou shi (a metallic product from Sassanian Persia) was brass, but this is not sure, neither is its connection with tutiya! The Sanskrit tuttha is derived from tutiya..." (Forbes, Robert James, 1964, Metallurgy in antiquity: a notebook for archaeologists and technologists, Brill Archive, p.288).

"Pewter is an alloy of tin with small additions of lead and other metals. Although it was in use for many centuries, and was displaced finally by pottery and porcelain, little remains that is earlier than the seventeenth century. It is a soft metal and subject to corrosion from the atmosphere, and it is perhaps remarkable that so much that is old has survived...Pewter was used for the making of domestic articles for everyday use: candlesticks, jugs, plates and dishes, tankards, spoons, and so forth...Paktong. This is an alloy of coper, nickel and zinc, which resembles silver...Paktong was imported into England from China, whence came also a pure zinc known as Tutenag. Writers often confused the two..." (Husain, R., The history of Pewter and Paktong at http://www.streetdirectory.com/travel_guide/34038/hobbies/the_history_of_pewter_and_paktong.html)

Celebration of tutthanAga in Zawar and Ahed temples, Rajasthan

Ancient zinc, sphalerite retorts in Zawar

Sphalerite

A beautiful cluster of green sphalerites mined 1980 - 85 from the Mogila Orebody, Deveti Septemvri Complex, Madan District, Southern Rhodope Mtns, Plovdiv Region, Bulgaria.

![]()

Zinc is a bluish-white, lustrous, diamagnetic metal. In nonscientific contexts zinc is known as ‘spelter’. Zinc is recovered from a number of different zinc ores. The types of zinc ores include sulfide, carbonate, silicate and oxide. Most significant of these ores are zinc sulphide or sphalerite i.e. (Zn,Fe)S, zinc carbonate or smithsonite (ZnCO3), zinc silicate or willemite (Zn2SiO4) and zinc oxide or zincite (ZnO). Ores of lead, zinc, cadmium and silver often occur together. Sphalerite or zinc blende is the most important zinc ore as it contains 64.06% zinc. It occurs mostly as veins.

The ancient assemblage of retorts for sublimation of sphalerite is stunning. The assembly of retorts shows an industrial-scale smelting operation to produce zinc mineral, a key additive to copper alloys such as pewter and brass. "Centuries before zinc was recognized as a distinct element, zinc ores were used for making brass. A prehistoric statuette containing 87.5% zinc was found in a Dacian archaeological site in Transylvania (modern Romania). Palestinian brass from the 14th to 10th centuries BC contains 23% zinc. The primitive alloys with less than 28 per cent zinc were prevalent in many parts of the world before India. Brass in Taxashila has been dated from third century BC to fifth century AD. A vase from Takshashila is of particular interest because of its 34.34 percent zinc content and has been dated to the third century BC. Recently two brass bangles belonging to the Kushana period are discovered from Senuwar (U.P.), which also shows 35 percent zinc.The Indians were the first to know about metal zinc, the bluish-white, lustrous metal and smelt on a large scale. The testimony to it is the presence of huge numbers of retorts and ruins spread over a large area in old Zawar village in southeastern Rajasthan. References to medicinal uses of zinc are in the Charaka Samhita, which is believed to have been written as early as 300 BCE in India."

![]()

Statue of Nag - Nagini: Zawar Mata temple

At Ahed excavation site statues of the Gods of both Hindu and Jain religion are found. Of particular importance is the statue of Parvati a deity of importance to Dravidians. Also the Nag- Nagini statue indicates the presence of Naga people around Ahed those days.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/meluhha-metallurgy-and-hieroglyphs_8.html?q=nagini

Glosses signifying 'squirrel' in Indian spachbund

``^squirrel'':Kh. ciRRa ~ ciDRa `squirrel'.Sa. ciDri'j.ciDri'j ~ cuDru'j.cuDru'j `the call of the striped squirrel'.@(V325)(Munda etyma)

2518 (a) Kol. siḍḍe squirrel. Nk. śiḍḍe id. Go. (W. Ph.) ciḍrāl, (Mu.) ciḍral (pl. ciḍrahk) id. (Voc. 1314). Kur. ciṛrā, ciḍrā id. / For similar words in Munda languages, see Pinnow, p. 157, Emeneau, JAOS 82.109, and Pfeiffer, p. 170.(b) Konḍa sirkuli squirrel. Pe. hirkoli id. Kui siruni, siruṛi, (K.) heruṛi id. Kuwi (Mah.) her'uṛi, (Ḍ.) hir'uni id. / Cf. Skt. cikroḍa- id. (Vaijayantī; > Te. cikrōḍamu id.), H. cīkhur id. DED(S, N) 2077.

2959 Manḍ. ṭilka squirrel. Kuwi (Su.) ṭilli, (F.) tilli, (Mah.) ṭili orli id.

4189 Pa. piṛca squirrel.? Go. (Tr.) warcē small striped squirrel; (A. Y.) verce squirrel (Voc. 3290)Ta. turu rust, verdigris, flaw; turucu, turuci blue vitriol, spot, dirt, blemish, stain, defect, rust; turicu fault, crime, sorrow, affliction, perversity, blue vitriol; tukku, tuppu rust. Ma. turiśu blue vitriol; turumpu, turuvu rust.

śrḗṣṭha ʻ most splendid, best ʼ RV. [śrīˊ -- ]Pa. seṭṭha -- ʻ best ʼ, Aś.shah. man. sreṭha -- , gir. sesṭa -- , kāl. seṭha -- , Dhp. śeṭha -- , Pk. seṭṭha -- , siṭṭha -- ; N. seṭh ʻ great, noble, superior ʼ; Or. seṭha ʻ chief, principal ʼ; Si. seṭa, °ṭu ʻ noble, excellent ʼ. śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ]Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ, seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M. śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2?)(CDIAL 12725, 12726)

*śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ. [Cf. śrētr̥ -- ʻ one who has recourse to ʼ MBh. -- See śrití -- . -- √śri]Ash. ċeitr ʻ ladder ʼ (< *ċaitr -- dissim. from ċraitr -- ?).(CDIAL 12720)*śrēṣṭrī2 ʻ line, ladder ʼ. [For mng. ʻ line ʼ conn. with √śriṣ2 cf. śrḗṇi -- ~ √śri. -- See śrití -- . -- √śriṣ2]Pk. sēḍhĭ̄ -- f. ʻ line, row ʼ (cf. pasēḍhi -- f. ʻ id. ʼ. -- < EMIA. *sēṭhī -- sanskritized as śrēḍhī -- , śrēṭī -- , śrēḍī<-> (Col.), śrēdhī -- (W.) f. ʻ a partic. progression of arithmetical figures ʼ); K. hēr, dat. °ri f. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 12724)

*śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ1]Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ?(CDIAL 12723)

Pk. daddara -- m. ʻ ladder, staircase ʼ; Ku. dādar ʻ slats on roof to which slates or tiles are fastened ʼ; M. dādar n. ʻ ladderlike and movable staircase, shutter over a staircase, bridge ʼ, dādrī f. ʻ bridge ʼ, dādrā m. ʻ shutter over staircase, hole in roof for smoke -- vent, cloth tied over a vessel ʼ dardara -- : G. dādar, dādrɔ m. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 6196)

6199 dardru m. ʻ a kind of bird ʼ Car., dadru -- 2 m. ʻ tortoise ʼ Uṇ.vr̥. [Cf. dardurá -- ? duḍi -- ?]Wg. də̃ŕəlīk, Phal. dādu ʻ hare (?) ʼ Morgenstierne; Kal. dadrṓk ʻ squirrel ʼ; Kho. dodór ʻ small lizard, chameleon ʼ BelvalkarVol 89 (or poss. < dardurá -- 1): -- doubtful bec. of uncertainty of meanings.

kalandaka -- , °anta°, °aṇḍa°, °añja° m. ʻ squirrel ʼ BHSk ii 171.Pa. kalanda -- , °aka -- m., Si. kalan̆dayā. (CDIAL 2917)

खार (p. 205) [ khāra ] m (क्षार S) Salt, mineral or vegetable, natural or factitious. 2 Impure alkaline salt obtained by burning plants (esp.अघाडा or Achyranthes aspera and माठ or पोकळा), boiling the ashes, straining the lixivium, and evaporating the water.

بلونګړيَ bilūngaṟṟaey, s.m. (1st) A squirrel. See also ګیدړي Pl. يِ ī. (Pashto)

खार (p. 205) [ khāra ] A squirrel, Sciurus palmarum. खारी (p. 205) [ khārī ] f (Usually खार) A squirrel.

खडी (p. 193) [ khaḍī ] f खटी S) A squirrel खडू (p. 193) [ khaḍū ] f खडूळ f A squirrel.

gilahȧri गिल््ह&above;रि&below; or gilahȧri गिलह&above;रि&below; f. a squirrel (Gr.M.). (Kashmiri)

खडी (p. 193) [ khaḍī ] f खटी S) A species of steatites used to rub over the writing-board, or to whitewash walls: also an unctuous and whitish stone, a sort of pipeclay. 2 A composition (of talc, gum &c.) for raising figures on cloth: also the figures raised.

2315 Ta. aṇil, aṇilam, (Ag., p. 175) aṇiyal, (Koll.) aṇṇattān squirrel. Ma. aṇil, aṇṇal, aṇṇān id.; eṇuṅku a variety of mountain squirrel.Ko. e·ṇḍḷ squirrel. (DEDR 2315) To. aṇil id. Ka. aṇal, aṇil, aḷale, aḷil, aḷul, aḷḷūma, āḷindaki, iṇaci, (Bark.) caṇila id. Koḍ. aṇekoṭṭï id. Tu. caṇilů, canilů, taṇilů, (B-K. also) aṇilů id

चानी (p. 278) [ cānī ] f R W A squirrel.P سنجاب sanjāb or سنجاپ sanjāp, s.m. (2nd) Ermine, the grey squirrel. Pl. سنجابونه sanjābūnah or سنجاپونه sanjāpūnah. (Pashto)

शेकरा (p. 797) [ śēkarā ] m शेकरी f शेकरू m f An animal of the Squirrel kind, Sciurus Elphinstonii.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

August 29, 2015

Annex:

Zinc and Brass in Archaeological Perspective

Authors: J. Kharakwal, L. Gurjar

Abstract

Brass has a much longer history than zinc. There has been a bit of confusion about the early beginning of zinc as several claims are made out side of India. Both literary as well as archaeological records reveal that production of pure zinc had begun in the second half of the first millennium BC, though production on commercial scale begun in the early Medieval times. This paper attempts to examine the archaeological record and literary evidence to understand the actual beginning of brass and zinc in India.

Published on 01 Dec 2006

Introduction

Zinc (Zn) is a non ferrous base metal, which is generally found in bluish-white, yellow, brown or in black colour. Its chief and important minerals are sphalerite or zinc blende, smithsonite, calamine, zincite, willemite and franklinite. As it boils at around 900° C, which is lower than the temperature it can be smelted at, therefore it is difficult to smelt this metal. Hence zinc technology was mastered later than that of copper and iron. For pure zinc production, therefore distillation technology was developed, in which India has the distinction of being the first. Zinc is used for galvanising iron and steel, brass making, alloying, manufacture of white pigment in chemicals and medicines. But in ancient times it was mainly used for brass making. In fact brass has a much longer history than zinc. Brass can be produced either by smelting copper ores containing zinc or copper and zinc ore in reduced condition or by mixing copper and zinc metals.

Early evidence of zinc has been claimed from several parts of Europe and Middle East e.g., Switzerland, Greece, Cyprus and Palestine. But all these claims, except for the evidence of the sheet of zinc from the Athenian Agora (300 BC) are doubtful (Craddock et al. , 1998: IS). Recent studies have shown that such small percentages of zinc may occur due to accidental use of copper ore associated with zinc or its ore.

Brasses containing up to 25 percent zinc have been reported from the fifth and third millennium BC contexts from China, but it seems that they did not play any role in the development of zinc production technology in the Far East. It is generally held that the Chinese started using zinc and brass from the last quarter of the third century BC when the Han Dynasty flourished in China. Craddock and Zhou have suggested that zinc was introduced in China through Buddhism around 2000 years ago. However, Weirong and Xiangxi (1994: 16-17) inform that the earliest literary record about brass mentioned as tutty is known from the Buddhist literature belonging to the Tan dynasty (619-917 AD). Brass ( thou-shih ) was not a common commodity in the early centuries of the Christian Era at least prior to 3 rdcentury AD in China. Bowman et al. (1989) have analysed 550 coins ranging from 3rd century BC (Zhao dynasty) to the late 19 th century (Ch'ing dynasty). They have found that the percentage of zinc suddenly increased by 20% or even up to 28% in brasses of the early 17 th century AD. It is also supported by the well known textual evidence of T'ien Kung K'ai Wu , written in 1637 (Sung and Sun 1966). It is the first definite evidence of metallic zinc in China, which also mentions details of alloys used for coins. Weirong (1993) has examined ancient Chinese literature and archaeological record and claims that metallic zinc was not used in China prior to the 16 th century AD.

As far as India is concerned the firm evidence of zinc smelting is known only from Rajasthan. The antiquity of mining various types of ores in Rajasthan goes back to Bronze Age (mid-fourth millennium BC) as the evidence of Ganeshwar-Jodhpura cultural complex in north Rajasthan and Ahar culture in southern Rajasthan would indicate (Agrawal and Kharakwal, 2003; Misra et al. 1995; Shinde et al. 2001-02). Both these cultural complexes have yielded over 5000 copper-bronze objects (Hooja and Kumar, 1995) ranging from 4 th to 1 st millennium BC. Apart from these, the Mesolithic site of Bagor in Bhilwara district also yielded a few copper arrowheads (Misra, 1973). There are large number of ancient copper, iron, lead working and smelting sites across Rajasthan in the Aravallis, indicating a long tradition of metallurgy. Besides metal tools, a variety of pottery, beads of semi precious stones, terracotta, paste and other antiquarian material is known from such early settlements. These early farmers were practicing diverse crafts using pyrotechnologies. It appears that large scale production of different metals e.g., copper at Singhana, Toda Dariba, Banera, Suras, Bhagal, Kotri, lead-silver at Ajmer, Agucha and Dariba, zinc at Zawar and iron at Dokan, Iswal, Karanpur, Loharia, Parsola, Bigod, Jhikari-Amargarh, belonging to the medieval times (Kharakwal, 2005) was the result of such long experience of metal technology involving pyrotechniques. In fact the Aravallis are a polymetallic zone like Anatolia.

This paper is an attempt to present an overview of the archaeometallurgical researches on zinc and the position of zinc and brass in archaeological perspective in India.

Zawar: The Oldest Production Center of Zinc

Zawar (24°21'N; 73°43'E) is located on the bank of the River Tiri, about 38 km south of Udaipur town in the Aravalli hills in Rajasthan (Fig. 1). It is the only known ancient zinc smelting site in India (Craddock et al. , 1985). The entire valley of Tiri at Zawar is marked by immense heaps of slag and retorts, which indicate a long tradition of zinc smelting at Zawar. On some slag-mounds are found remains of houses made of used retorts (Fig. 2) and stones, perhaps belonging to the smelters/smiths.

Fig. 1: Map showing location of Zawar (after Craddock et al 1985)

Fig. 2: Residential structures made of discarded retorts

Though archaeometallurgical activity at Zawar was casually recorded by several Indian and British scholars between 17 th and 20 th century, the credit of highlighting the importance of the ancient remains however goes to Crookshank (1947), Carsus (1960), Morgan (1976), Strackzeck et al. (1967) and Werner (1976 see in Gurjar et al. , 2001). Perhaps these reports encouraged P.T. Craddock of British Museum and K.T.M. Hegde of M.S. University of Baroda to initiate archaeometallurgical study at Zawar jointly with Hindustan Zinc Limited, Udaipur in 1983 (Craddock et al. , 1983, 1985; Gurjar et al. , 2001; Hegde, 1989; Paliwal et al. , 1986; Willies, 1984). This team carried out extensive investigations both for ancient mining as well as smelting of zinc at Zawar. They discovered incredible evidence for mining and furnaces used for zinc smelting, besides primitive smelting retorts from the dam fill at Zawar.

Besides Zawar, the evidence of early zinc mining and smelting has also been found 2 km south east of village Kaya in form of a small retort heap and ancient mine workings in the adjacent hills. It is the northwestern continuation of Zawar mineralization. These remains have not been studied in detail but considering the shape of retorts it can be safely concluded that they are of the same period. Kaya is located 6 km north of Zawar, and about 15 km south of Udaipur town.

Mining

Zinc ores are widely distributed in the country, but major deposits are found in the Aravallis. In recent years one of the largest lead-zinc deposits have been discovered at Agucha in Bhilwara district (Tewari and Kavadia 1984), though the well known ancient lead-zinc workings are located in the Zawar area of Udaipur district. Zinc (Zn) is generally found in veins in association with galena, chalcopyrite, ironpyrite, silver and cadmium and other sulphide ores (Raghunandan et al. , 1981). The Aravalli range in southern Rajasthan is composed of rugged and gorgeous hills of pre-Cambrian metamorphic rocks with narrow valleys. These rocks are rich in zinc ore in the form of sphalerite veins in association with galena and copper bearing deposits. This mineralized belt of Zawar extends for about 25 km. The major mineralization of sphalerite and galena with varying quantities of pyrite have been found in the form of sheeted zones, veins, stringers and lenticular bodies (Raghunandan et al. , 1981). Since these minerals are quite distinct from each other it was possible to separate them manually and this explains why zinc mining and smelting developed only at Zawar.

There are extensive remains of old workings in Zawarmala, Mochia Magra, Balaria, and at Hiran Magra in Zawar area in the form of deep trenches, shafts, open stopes, long serpentine galleries and inclines. These mines are narrow and vary from 10 to 300 m in length. There is extensive evidence of underground mining too (Fig. 3). It appears that this mining continued for several hundred years as indicated by the enormous mound of slag and smelting debris.

Fig. 3: The ancient mine in Zawar

Once the ore was located on ground, based on the presence of gossan or mineralized veins, the miners followed the down ward extension along dip and pitch of the ore-shoot and developed huge inclined stopes and chambers underground. These stopes and branched chambers were supported by finger like inclines further down. Arch shaped pillars (about 4XSm) were left to support the roof while developing such stopes and chambers (Gurjar et al. , 2001). Mining was carried out by fire setting as evidenced by the rounded profile of galleries and stope chambers, the supporting pillars, smooth surface of rock faces with sooty deposits and the floors are buried deep in charcoal, ashes and calcined rocks (HindZinc Tech 1989). After dousing the fire the rocks were broken with chisels, pick axe, hoes and other iron implements. A few such objects have been discovered from Mochia mines (Craddock et al. , 1989: 62, p13). Extensive use of wood in the form of ladders, roof support, haulage scaffold ( 14 C date: 2350±120 BP) have been found in the mines.

Extensive open pit mining followed by underground method was carried out at Rajpura Dariba. An opencast mine of lead-zinc (300 m long and 100 m wide) developed over east lode at Dariba, (Raghunandan et al. 1981 :86-87) is a remarkable evidence of ancient mining technology practiced in southern Rajasthan. Excavation carried out by Hindustan Zinc Limited in 1986 has brought out the presence of massive timber revetment in the hanging wall of the open pit. This consists of three or probably four benches each 4m high with closely placed vertical posts, held back by three pairs of horizontal timbers and are pinned by long timbers to provide support to weak hanging wall.

Here, in one of the underground mines of the East Load the miners reached up to a depth of 263 m, in the 3 rd 4 th century BC (Craddock et al. 1989:59; Willies et al.1984). Such mines are rarely known in the ancient world. A 14 C date from Dariba indicates that deep underground mining had begun in the second half of the second millennium BC. At Agucha also extensive evidence of mining of rich galena pockets datable to the Mauryan times has been discovered (Tiwari and Kavdia, 1984: 84-85). The smelting debris and mining clearly indicates that it was carried out for lead and silver.

For dewatering mines launders of hollowed timber (3 m long and 20 cm wide) were used, which have been dated back to 2 nd century BC (Bhatnagar and Gurjar, 1989: 6). It is likely that some kind of buckets may have also been used for pulling out water from such deep mines. The possibility of shallow depressions at certain interval in the slanting wall of the mines for collection of water can not be ruled out.

A few shallow conical and U shaped pits have been reported in hard rocks at Baroi and Dariba. They may have been used for crushing/ breaking rock fragments in order to separate and beneficiate the ore before smelting. At Dariba such pits having a diameter of 27-30 cm and 60-70 cm deep were found close to a large opencast in calc-silicate rock. While at Baroi in Zawar these were 8-12 cm in diameter and 10-18 cm deep and found on the surface next to ancient mine workings.

It is interesting to note that mining of such non-ferrous metals was also recorded in the contemporary literature like Kautilya's Arthasastra (2.12.23, 2.17.14 & 4.1.35), which mentions that there was a superintendent of mines in the Mauryan Empire (Kangle, 1972). His duty was to identify metals and establish factories. While describing silver ores the text clearly mentions that it occurs with nag (lead) andanjan (zinc). Since there is extensive evidence of mining and smelting of lead, zinc and silver at Zawar, Dariba and Aguchha in Rajasthan, it is quite likely that Kautilya was aware of this activity. Harry (1991) points out that the imperial Maurya series of coins, particularly silver ones, containing one fourth of copper, strongly indicates the mining of silver and zinc from southern Rajasthan. Mining of such ores had surely begun in Rajasthan by the middle of the first millennium BC, if not earlier.

Some scholars have argued that Zawar should be identified as Aranyakupgiri of the Samoli inscription (Halder, 1929-30) belonging to seventh century AD. The word Aranyakupgiri of the inscription perhaps stands for deep well like mines. Of course such mines were there in Zawar during this time, but the inscription may refer to the mines of Basantgarh located near Samoli in Sirohi district rather than Zawar.

The underground mining of ores at Agucha, Dariba and at Zawar may have been the result of a gradual development of mining technology in Southern Rajasthan going way back to the middle of the fourth millennium BC when Bronze Age cultures had just appeared on the scene in the region.

What is interesting is the fact that no evidence of smelting of zinc has been found so far prior to 9 th century BC. Craddock et al. have pointed out that mining of zinc ore was surely done in Zawarmala in 3 rd -4 th century BC. Perhaps the evidence of smelting ranging from 4 th century BC to 9 th century is buried under the massive dumping of retorts and smelting debris and temple complexes. The evidence of a large stone structure and Early Historic pottery shapes exposed near the Jain temple in old Zawar also confirms the same.

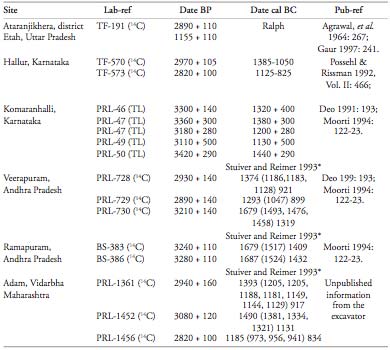

Table 1. Radio Carbon Dates for Zawar Mines (After Gurjar et al. , 2001)

| BM No. | Context | Material | Date BP | Calibrated dates |

| BM-2017R | Retort | charcoal | modern | 1550 to 1635 AD

Modern |

| BM-2065R | Retort | charcoal | modern | 760 to 360 BP |

LW/1982/2

BM-2148R | | wood | 2350±120 | 285 to 255 BC |

| BM-2149R | LW/1982/1,

Launder in escape route | wood | 2140±110 | 365 BC to 90 AD |

| BM-2222R | Trench layer 3 | charcoal | 240±110 | 1510 to 1690 AD or

1730 to 1810 AD or

1925 AD to modern |

| BM-2223R | Site 30, N side of furnace | charcoal | 530±50 | 1320 to 1345 AD or

1390 to 1435 AD |

| BM-2243R | sample 33, site 34 | charcoal | 350±130 | 1420 to 1670 AD |

| BM-2484 | site 5, layer 3, slag heap | charcoal | 100±45 | 1695 to 1730 AD or

1815 to 1920 AD |

| BM-2485 | site 14, layer 3 | charcoal | 1950±60 | 25 BC to 115 AD |

| BM-2486 | site 29, layer 2, small pit or hearth | charcoal | 200±35 | 1660 to 1675 AD or

1745 to 1800 or

1940 AD to modern |

| BM-2487 | site 2, trench 2, slag heap | charcoal | 1930±80 | 40 BC to 145 AD;

170 to 180 AD |

| BM-2488 | site 7, trench 2, slag heap | charcoal | 1370±80 | 595 to 720 AD or

740 to 765 AD |

| BM-2638 | furnace block | charcoal | modern | |

| BM-2639 | ZWLW/22, Pratap khan | charcoal | 2040±70 | 160 to 135 BC or

125 BC to 25 AD |

| BM-2481 | ZM/LW/85/13 small chamber off main galleries | charcoal | modern | modern |

| BM-2482 | ZM/LW/85/14 short ladder way | wood | 2150±110 | 365 to 100 BC |

| BM-2483 | ZM/LW/85/8, burned layer | wood | 2180±35 | 355 to 290 BC or

250 to 195 BC |

| BM-2634 | ZWLW/87/26, top chamber | charcoal | 1340±100 | 600 to 790 AD |

| Balaria | | | | |

| BM-2338 | support timber western slope | wood

(outer ring) | 170±50 | 1660 to 1695 AD or

1725 to 1820 AD or

1860 to 1865 AD,

1920 to modern |

| BM-2381 | Gallery | wood

(outer ring) | 2360±60 | 750 to 720 BC or

525 to 385 BC |

| BM-2666 | ZW/LW/87/32 | charcoal | 390±50 | 1440 to 1520 AD or

1590 to 1629 AD |

The consistency of these radiocarbon dates clearly suggest that mining activity was carried out during the Early Historic period and medieval times (Craddock et al. , 1989:48).

Traditionally Maharana Lakha or Laksha Singh (14 th century), who was ruling in the last quarter of the 14 th century, is believed to have re-opened these mines. He might have opened several new mines rather than reopening the old ones. Besides, Maharana Pratap (16 th century) is also credited for opening new mines at Zawar. One of the major mines at Zawarmala is known after him. It seems that large scale production of zinc continued despite political instability in southern Rajasthan during the late medieval times.

It was Abul Fazl who for the first time in 1596 in his well known Ain-i-Akbarirecorded the zinc mines of Zawar (Blochmann, 1989: 41-43). The mining and smelting activity was not only registered in the contemporary local records and literature (e.g., Nainsi ri Khyat in 1657; Bakshikhana Bahi 91, Rajasthan State Archives records of Udaipur and Bikaner and others) but also in the writings of several scholars of the 19 th and 20 th century, mostly British (Anon, 1872; Brooke, 1850; Carsus, 1960; Erskine, 1908; Shyamal Das, 1986 I (originally published in 1886): 305; Tod, 1950: 221-222).

Mining of several ores for example iron, copper, lead was being done as late as the 19 th century in several parts of Rajasthan. Unfortunately the Zawar zinc operation came to a halt around 1812 AD, unlike the Chinese traditional zinc smelting. A few British officers attempted to restart these mines in the middle and late nineteenth century with the financial support of Maharana Sarup Singh (1842-61), Shambhu Singh (1861-1874 AD) and Sajjan Singh (1874-1884 AD), but failed. It is believed that due to political instability in Mewar, frequent attacks of the Mughals, Pindaris and the Marathas and recurrent famines in the 18 th century these mines were abandoned.

Smelting and Production

The entire valley of the Tiri in Zawar is dotted by massive dumpings of slag and earthen retorts indicating a long tradition and commercial production of zinc. Several radiocarbon dates (see table 1) bracketed between 12 th and 18 th century also conform this activity. Gurjar et al. (2001: 633) write, "the earliest evidence of zinc smelting on industrial scale is the carbon date of 840±110 AD for one of the heaps of white ash removed from zinc smelting furnace. The fragment of relatively small, primitive retorts and perforated plates found in the earth fill of dam across the Tidi (Tiri) river may belong to the period or they must at least predate the dam itself. It appears that the main expansion of the industrial phase of zinc production began at Zawar sometime from 11 thor 12 th century" .

At Zawarmala a bank of seven distillation furnaces (Fig. 4), roughly squarish on plan (66x69 cm), were discovered by Craddock et al. Each furnace had two chambers, upper and lower, separated by a thick perforated plate of clay. It is presumed by the excavators that the furnaces may have looked like truncated pyramids and their height may have been about 60 cm. Brinjal shaped earthen retorts, filled with charge, were placed on the perforated plate in inverted position in the upper chamber. As many as 36 retorts were placed in each furnace for smelting and they were heated for three to five hours. The retorts were made in two parts and luted together after filling the charge. To prepare the charge the ore was subjected to crushing and grinding and mixed with some organic material and cow dung! rolled into tiny balls and left in the sun for drying. These balls then were placed in retorts after drying. A thin wooden stick was placed in the narrow opening of retort, which perhaps prevented falling of charge in the lower chamber before heating when they are initially inverted in the furnace, and at the same time would facilitate the escape of zinc vapour formed during heating. Such special retorts, ranging from 20 to 35 cm in length and 8 to 12cm in diameter, were developed by the metallurgists at Zawar for zinc distillation. Identification of different size of retorts is sure indication of different shape and size of furnaces at Zawar, as the evidence of a bigger furnace (base 110 cm square) from old Zawar would also indicate. After heating, zinc vapor was collected and condensed in the lower chamber in small earthen pots. It was surely an ingenious method that was devised for downward distillation of zinc vapour by the Zawar metallurgists. Thus, it was for the first time anywhere in the world that pure zinc was produced by distillation process on a commercial scale at Zawar. Gangopadhyay et al. (1984) and Freestone et al. (1985) have carried out technical studies of ore and retorts. Craddock (1995 :309- 321) compares these furnaces with koshthi type furnaces illustrated in Rasaratnasamuchchaya, an alchemical text datable to 13 th century, and other earlier texts on the same subject. Thanks to the joint efforts of the Hindustan Zinc, British Museum and M.S. University Baroda for such wonderful discovery that is possibly the ancestor of all high temperature pyrotechnical industries of the world.

![site photo]()

Fig. 4: Zinc smelting furnaces at Zawar

It has been estimated that each retort may have been filled with one kilogram of charge out of which 400 gram of zinc may have been produced. Thus each furnace produced around 25 to 30 kg of zinc in one activity of smelting. It has been estimated that 600,000 tons of smelting debris at Zawar, produced about 32,000 tones of metallic zinc in four hundred years (between 1400 and 1800 AD). If we estimate this production from 12 th century to 18 th century the quantity of metal would certainly be more than 50,000 tonnes. Colonel Tod in his well known work, Ann als and Antiquities of Rajasthan, has reported that the mines of Mewar were very productive during the eighteenth century, and in the year of 1759 alone the mines earned Rs. 2,22,000 (Tod, 1950: 222, 399). Tod writes that about haifa century ago these mines were earning Rs. three lakhs annually. Dariba mines yielded Rs. 80,000. He has recorded these mines as Tin mines of Zawar. Since we do not have any evidence of ancient tin working in Mewar region his tin mines must be nothing but zinc mines of Zawar. Moreover the Imperial Gazetteer of India Provincial Series Rajputana (1908: 52) clearly mention that these mines were famous for silver and zinc and were worked on a large scale until 1812-13 when the worst famine took place (Kachhawaha, 1992: 26-27; Malu, 1987; Singh, 1947).

The production of zinc was perhaps very high under the rule of Maharana Jagat Singh and Maharana Raj Singh during 17 th century as the local records of AD 1634-35 and 1657 reveal that annual revenue of Zawar was rupees 2,50,000 and 1,75,002 respectively. It is also clearly indicated in the record that per day income of these mines was Rs. 700; this estimate was confirmed by Muhnot Nainsi in his famous work Nainsi ri Khyat (1657) (Ranawat, 1987). Another record belonging to the reign of Maharana Raj Singh, reads that the revenue earned in a year from Zawar was Rs. 17,96,944 (Bhati, 1995: 1, 2, 11, 12, 14). Gurjar et al. (2001: 634) have examined a record of the same king dated to 1655 AD, preserved in the State Archives, Udaipur which mentions an income of Rs. 1,70,967 in a single month from Zawar! We are however, not sure whether this income was obtained only from mining and smelting. As the entire area of Zawar is gorgeous and agriculture may not have been enough to generate revenue, therefore it is likely that the entire revenue was earned from mining and production of zinc. Erskine (1908) also informs that these mines were certainly an important source of income right from fourteenth to early nineteenth century as they yielded more than two lakh rupees annual revenue for Maharana's treasury at least until 1766. Thus the annual income from Zawar was quite handsome and it is likely that due to large scale production of zinc Zawar may have become one of the main sources of state revenue and an important trade centre between the 12 th and early 19 th century AD. The discovery of an earthen pot containing a coin hoard datable to 16 thcentury by L.K. Gurjar in 1984 (Gurjar et al. 2001) at old Zawar also suggests that this area was an important commercial center. There are remains of few structures on top of a hillock at Zawar, which, according to knowledgeable villagers, belong to Vela Vania (a trader known as Vela). Perhaps Vela Vania was involved in zinc trade.

It is worth mentioning here that most of the existing forts, huge water reservoirs, temple complexes, water structures, and other monuments in Mewar were built between 10 th and 18 th centuries AD. It is likely that the revenue earned due to brisk trade of zinc at Zawar was utilized for construction of these large monuments.

Zinc and Brass in Archaeological Perspective

Only a few Harappan bronzes have yielded a small percentage of zinc. For example Lothal, a Harappan sites in Gujarat (2200-1500 BC) (Rao, 1985), has yielded around haifa dozen copper based objects containing zinc, which varies from 0.15 to 6.04 % (Nautiyal, et al. 1981). One of the objects (antiquity No. 4189), though not identified, contains 70.7% of copper, 6.04 % of zinc and 0.9% Fe, which could be termed as the earliest evidence of brass in India. From Kalibangan, another Harappan site in north Rajasthan, a long spear head of copper was found containing 3.4% of zinc (Lal et al. 2003: 266). There is some evidence of brass from the early Iron Age when we come across two examples from Atranjikhera (1200- 600 BC), a Painted Grey Ware culture site in the Ganga doab. One of the objects leaded bronze contains 1.68% tin, 9.0% lead and 6.28% of zinc whereas the other one assayed 20.72% of tin and 16.20% of zinc (Gaur 1983: 483-90). Unless we have more examples of bronzes containing appreciable percentage of zinc replacing tin, arsenic or other elements we can not infer that the Bronze or Early Iron Age cultures were aware of the nature and property of zinc. Nevertheless these examples perhaps represent the early or experimental stage of zinc in India. The archaeological record indicates that in the second half of the first millennium BC the percentage of zinc started increasing and intentional use of brass appears on the scene. Such evidence has been found from Taxila, Timargarh and Senuwar.

Taxila, located about 30 km north of Rawalpindi in Pakistan, has yielded a large variety of metal objects including those of copper, bronze, brass and iron (Marshall, 1951 :567 -69). Several brass objects datable from the 4 th century BC to 1 st century AD have been discovered. One of them was a vase from Bhir mound, which predates the arrival of the Greeks at Taxila (Biswas, 1993) and has assayed 34.34 % of zinc, 4.25% of tin and small quantity of lead (3.0%), iron (1.77%) and nickel (0.4%). Another evidence of real brass was discovered recently at Senuwar in the Ganga Valley from the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBP) levels (Singh, 2004: 594). It has 64.324% of copper and 35.52% of zinc.

Brasses made by cementation method generally contain less than 28% of zinc and rarely could go up to 33% (Werner, 1970). Since the examples of Taxila and Senuwar have yielded more than 33 % of zinc, therefore these are the earliest definite examples of real brasses. They must have been made by mixing metallic zinc with copper. Zinc is a volatile metal and due to its low boiling point (907° C), which is lower than the temperature it could be smelted, it is difficult to smelt. Unlike other metals, it comes out in the vapour form from the furnace and gets reoxidised, if it is not condensed. Craddock et al. have pointed out that zinc ore was mined way back from 5 th century BC (PRL 932 430±100 BC; BM 2381 380±5O BC) at Zawar and metallic or pure zinc was produced here by distillation process for the first time in the world. The production of metallic zinc has been traced back to 9 thcentury AD at Zawar, but there is a strong possibility that the older evidence is buried under the immense heaps. Though Taxila folks were aware of the distillation process (Habib, 2000), yet in the absence of definitive evidence we cannot claim that they employed this process for obtaining zinc. It is possible, though not proven that metallic zinc was produced at Zawar way back from the 6th century BC, from here it reached at Taxila and Senuwar. The other possibility is that zinc was scrapped from the cooler parts of the furnaces at both sites!

Besides these, Prakash (Athavale and Thapar, 1967: 132 table IV) and Mahurjhari in Mahararashtra (Deo, 1973; Joshi 1973:77), Asura sites in Chhotanagpur region (Caldwell, 1920: 409-411; Roy, 1920: 404- 405) have yielded brasses, which have been dated to the second half of the first millennium BC. Most of these brasses have more than 15% of zinc and some of them contain between 22 to 28 percent of zinc. This kind of evidence clearly points out they were made by cementation process.

Several circular or rectangular punch-marked and other coins of brass, . bracketed between the 2 nd century BC and 4 th century AD (Smith, 1906) (see Table 2), are known mostly from northern India. Since none of them is analysed we do not know if they are real brasses (objects containing more 28% zinc are called real brasses) or made by cementation process. What is interesting is that most of these coins belong to the regional kings, indicating popularity of brass in India. This kind of evidence goes against the assumption that the Greeks introduced brass in India. The archaeological record clearly points out that the Indians knew brass prior to the arrival of the Greeks.

| No. | Period | King/Site | No. | Shape | Reference |

| 1 | 200 BC | Gomitra | 1 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 205 |

| 2 | 200 BC | Mitasa (Gomitra?) or Satasa | 1 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 205 |

| 3 | 2 nd cent. BC | Unidentified | 1 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 194 |

| 4 | 2 nd cent. BC | Gomitra (Mathura) | 1 | Circular | Smith, 1906: 193 |

| 5 | 2 nd cent. BC | Uttama Datta (Mathura) | 1 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 193 |

| 6 | 2 nd cent. BC | Bhavadatta (Mathura) | 1 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 193 |

| 7 | 2 nd cent. BC | Purushadatta (Mathura) | 1 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 192 |

| 8 | 2 nd cent. BC | Amoghbhuti (Kuninda king) | 6 | Circular | Smith, 1906: 168-169 |

| 9 | 2 nd cent. BC | Rajanya (Naga or Narwar) | 4 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 179-180 |

| 10 | 2 nd cent. BC | Asvaghosa (Kosam) | 1 | Circular | Smith, 1906: 155 |

| 11 | 150 BC - 100 AD | Dhana Deva (Ayodhya) | 1 | Rectangular | Smith, 1906: 148 |

| 12 | 150 BC - 100 AD | Siva Datta (Ayodhya) | 3 | Rectangular | Smith, 1906: 149 |

| 13 | 150 BC - 100 AD | Ajaverma (Ayodhya) | 1 | Circular | Smith, 1906: 150 |

| 14 | 125 - 80 AD | Hagamasha (Satrap of Mathura) | 1 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 196 |

| 15 | 100 BC | Audumbara king | 1 | Circular | Smith, 1906: 166 |

| 16 | 1 st cent. BC - AD | Yaudheya kings | 3 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 181 |

| 17 | 1 st cent. BC - AD | Agnimitra (Panchala and Kaushala) | 2 | Circular | Smith, 1906: 186-187 |

| 18 | 1 st cent. BC - AD | Bhumitra (Panchala and Kaushala) | 1 | Circular | Smith, 1906: 187 |

| 19 | 1 st -1 nd cent. AD? | Devasa (Kosam) | 8 | Circular | Smith, 1906: 207 |

| 20 | 1 st -1 nd cent. AD | Unidentified | 1 | Rectangular | Smith, 1906: 201 |

| 21 | 2 nd cent. AD | Unidentified | 2 | Circular | Smith, 1906: 203-204 |

| 22 | 3 rd -4 th cent. AD | Pasaka (Kushana type) | 1 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 89 |

| 23 | Medieval | Unknown (Jajjapura/i) Sri Siva type | 1 | Not stated | Smith, 1906: 333 |

| 24 | 3 rd -4 th cent. AD | Basata (later Kushana) | 5 | Not stated | Chatterjee, 1957: 103 |

Table 2: Early brass coins of lndia (After Smith 1906)

Beside coins, several other brass antiquities have also been reported from the Early Historic sites in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, which include lids, caskets, bangles, finger rings, utensils, icons, chariot and religious object and utensil (Biswas, 1993, .1994: 360; Biswas and Biswas, 1996: 132).

Since zinc could change the colour of copper and impart it a golden glitter, it was preferred for making Hindu, Buddhist and Jain icons throughout the historical period. For example among the brass icons of the Himalayan region (from Tibet to Gandhar) lead is present in appreciable amount and the percentage of zinc varies from 4 to 35 (Chakrabarti, and Lahiri, 1996: 108-109; Reedy, 1988). Obviously these brasses were made by selection of ore, cementation process and mixing metallic zinc with copper. In the absence of a source of zinc in the Himalayan region it may be suggested that metallic zinc may have been supplied from Zawar. The higher percentage of lead in these brasses clearly suggests that it was deliberately added to increase the casting ability of the metal. Such leaded brasses were calledkakatundi in ancient India.

Craddock (1981 :20-31) has reported analysis of 121 Tibetan and Himalayan icons/metal works by atomic absorption spectrophotometer for 13 elements in each sample down to 10ppm level. He has shown that as many as 45 artifacts have more than 28% of zinc, which might have been made by mixing copper and zinc. The percentage of zinc in such artifacts ranges from 28 to 54. It seems that most of the brasses of his list belong to Medieval and later Medieval times.

From Phopnarkala and East Nimar, in Madhya Pradesh, several standing brass images of Buddha have been discovered (Sharma and Sharma, 2000) assigned to the Gupta-Vakataka period (5 th -6 th centuries AD). These brasses contain high percentage of zinc ranging from 21 to 30%, which means that they were made by cementation process (Tondan, 1983).

In the first half of the seventh century AD (AD 629-645) Hiuen Tsiang, a Chinese scholar of Buddhism, extensively traveled in India. He saw a magnificent vihara(residential complex of Buddhist monks) of brass near Nalanda under construction during the reign of Raja Siladitya (Harshavardhan AD 606-647). It would have been more than 100 feet long when completed (Beal, 2000 vol. ii: 174). He also noticed brass images ( teou-shih ) of Buddhist and Brahmanic deities at several places in northern India (Beal, 2000 vol. i: 51, 89, 166, 177,197, 198, vol. ii: 45, 46,174).

The metal art of Eastern Indian complex, mainly coming from Bihar, West Bengal and Bangladesh, is also fairly well known. A large number of ancient bronzes, belonging to Pala and Sena School of art datable between 8 th to 12 th centuries AD contain considerable amount of zinc (Leoshko and Reedy, 1994; Pal, 1988; Reedy, 1991a, b).

A large number of bronzes and brasses mostly icons of Jain and Hindu deities, containing appreciable amount of zinc, have been reported from various parts of Gujarat, and are datable to 6 th to 14 th centuries AD (Swarnakamal, 1978). Most of the late medieval brasses were made by mixing metallic zinc with copper as the percentage of zinc has been found to exceed more than 28%. In some cases lead is present up to 9.5%, which must have been useful rending fluidity to the metal. It is likely that all these brasses were made of using metallic zinc from Zawar. Biswas (1993) writes that the icon of seated Tirthankara dated AD 1752 from Gujarat is one the finest example of the late medieval brasses in India, which was made a few years before the Maratha invasion of Mewar.

Table 3: Elemental percentage of brasses datable to 14 th to 18 th centuries AD

(after Biswas, 1993 and Swarnakamal, 1978)

| No. | Object | Provena. | Period | Cu% | Zn% | Sn% | Pb% | Fe% | Impurities |

| 1 | Ambika | Gujarat | 1350 | 68.4 | 18.5 | 1.6 | 9.5 | - | Fe, Ag, Bi |

| 2 | Model of temple with 4 doors | " | 1480 | 68.6 | 28.9 | 0.2 | 1.6 | - | Fe, Mg, Bi |

| 3 | Vishnu-Narayan | " | 1485 | 58.9 | 36.8 | 0.5 | 2.1 | - | Fe, Al, Ag, Si, Mg, Bi |

| 4 | Rajput Prince | Rajasthan | 15 th -16th | 72.9 | 21.8 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 1.0 | Al 0.3, Mg, Ag |

| 5 | Kal Bhairava | Gujarat | 1554 | 76.7 | 13.8 | 1.2 | 6.3 | 1.5 | Al, Mg |

| 6 | Chauri Bearer | Gujarat | 17 th | 58.3 | 35.5 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 0.8 | Fe, Ni, Al, Ag, Cd, Si, Mg |

| 7 | Dipalakshami | Rajasthan | 17 th | 58.8 | 33.2 | 0.9 | 4.5 | - | Al 1.6, Mg |

| 8 | " | Gujarat | 18 th | 52.8 | 39.9 | 1.1 | 2.9 | - | Fe, Al |

| 9 | Tirthankara (seated) | Gujarat | 1752 | 62.3 | 36.0 | - | 0.5 | - | Fe, Ag, Bi |

| 10 | Sadakasari Lokesvara form of Avlokitesvara | Nepal | | 60.5 | 35.3 | 2.75 | 2.37 | - | Fe, Ni, As, Au |

Table 3 contains a few brasses from medieval and late medieval period of India, most of which have a high percentage of zinc. All those examples containing more than 33% were certainly made of metallic zinc. In some cases lead is present up to 9.5%, which must have been useful rending fluidity to the metal. The metallurgists were obviously skilful to produce high quality of brass. It is quite likely that all these brasses were made by using metallic zinc from Zawar. The Mughals, who ruled over India between 12 th and 16 th centuries, had metalkarkhanas (factories), in which a large number of brasses for example utensil, decorative pieces, guns, mortars and so on were produced perhaps employing zinc from Zawar (Neogi, 1979: 40-42).

It is held that the artillery made of iron, bronze and brass was introduced in India during the Mughal period. Large cannons and guns made of brass have been reported from Agra, Bengal and other places (Neogi, 1979). There are a few brass cannons at Udaipur too, which might have been made by zinc obtained from Zawar.

Bidri Ware

The Bidri Ware of Bidar in South India, belonging to medieval period, is well known for its glossy black surface decorated with exquisite silver inlay art (Gairola, 1956). It is a zinc alloy decorated with silver or gold inlay. La Niece and Martin (1987) have done detailed technical study of27 vessels of this ware from the Victoria and Albert Museum's collection. Their results show that the content of zinc varies from 76 to 98%, copper 2 to 10% and lead 0.4 to 19%. Lead isotope studies have indicated that the zinc was not obtained from Zawar for Bidri ware (Craddock et al. 1989: 52-53). This kind of result has brought about a challenge to look for other zinc production sites in India, if this metal was not imported from outside!

Literary Evidence

Ayurvedic treatises such as Susrut Samhita (5 th century BC) and Charak Samhita (2nd century BC) record the use of essence of various minerals and metals e.g., gold, silver, copper, tin, bronze and brass for preparation of medicine. These texts also mention that the instruments used for curing delicate parts of the body were made of gold, silver, copper, iron, brass, tooth, horn, jewels and of special variety of wood (Datt Ram, 1900: 12; Sharma, 2001 II: 444). Both these texts record brass as riti or ritika. It is interesting that both Charak Samhita and Susruta Samhita refer topushpanjan, which was prepared by heating a metal in air and was used for curing eyes and wounds ( Chikitsasthanam 26.250) (Shukla and Tripathai, 2002: 661; Ray, 1956: 60). This could be identified as zinc oxide as Craddock (1989: 27) points out that "no other metal would react in the air to produce an oxide suitable for medicinal purpose". Therefore, these Ayurvedic texts are perhaps the earliest literary evidence of zinc in India.

Kautilya's Arthasastra is one of the earliest firm datable (4 th century BC) textual evidence for mining and smelting of metals, which reveals that the director of metals was responsible for establishing factories of various metals such as copper ( tamra ), lead ( sisa ), tin ( trapu ), brass ( arakuta ), bronze ( kamsa or kamsya ), talaand iron (Kangle, 1960 vol I: 59 and vol II: 124; Kangle, 1972 vol II: 108). Brass has also been frequently mentioned in ancient Sanskrit and Buddhist literature and was popularly known as harita, riti, ritika, arkuta or arkutah, pitala and so on (Chakrabarti and Lahiri, 1996: 149; Neogi, 1979: 41; Sastri, 1997:208). The termkamsakuta of Digha-nikaya and Dhammapada Atthakatha has been interpreted as brass coins by Chatterjee (1957: 104-111). He strongly argues that brass currency was in vogue between 6 th and 4 th century BC in India, though we don't have chemical analysis of known coins of this period. Darius I, a Persian king, had a few Indian cups, which were indistinguishable in appearance from gold except for their smell (Hett, 1993: 257). This may only be the Indian brass.

Strabo quotes the explanation of Nearchus about India, who traveled the north-western part of this country with the Macedonian army in 4 th century BC, and writes that "they use brass that is cast, and not the kind that is forged; and he does not state the reason, although he mentions the strange result that follows the use of the vessels made of cast brass. that when they fall to the ground they break into pieces like pottery"(Jones, 1954: 117). This kind of evidence indicates that Indians were making brass way back in 4 th century BC. But we do not know whether it happened due to absence of lead or high percentage of zinc?

The alchemist Nagarjuna is well known for his treatise on alchemy titledRasaratnakara, which was perhaps originally written, as Biswas (1993: 317, 1994: 361-362; Ray, 1956: 116-118) argues, between 2 nd and 4 th century AD and compiled around 7 th or 8 th centuries AD. Nagatjuna was certainly a great scientist, who, for the first time, not only described cementation process but also zinc production by distillation technique (Biswas, 1993: 317; 1994: 361-362; Ray 1956: 129). This is therefore the earliest literary evidence, which records that brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. Rasarnavam Rastantram, an alchemical text datable to 12 th century AD, is an important alchemical text, in which both brass and zinc have been recorded. This text clearly records zinc making process (Craddock et al,1989: 31; Ray, 1956: 118), besides different kinds of zinc ores e.g., mratica rasak, gud rasak and pashan rasak. Apart from these there are a few other alchemical texts such as Rasakalpa, Rasarnavatantra, Rasprakash Sudhakar of Yasodhara,Rasendrachudamani of Somadeva and Rasachintamani of Madanantadeva (all datable from 10 th to 12 th centuries AD), also explain different kind of brasses and zinc- making by distillation process (Ray, 1956: 171-191). The description by Yasodhara for extraction of zinc appears to be the best one as Craddock et al. 's (1989) work has shown that it fits well with the process used at Zawar. These texts reveal that koshthi type furnaces were used for smelting and had an arrangement of two chambers separated by a perforated plate. For distillation tiryakpatana yantra were used. The Rasaratnasamuchchaya, a late 13 th or early 14 th century work of iatro chemistry, is the best available literary evidence of zinc production process. In fact the zinc smelting process described by Yasodhara earlier has more or less been repeated in this text besides the illustrations of apparatus by Somadeva. Bhavamisra in the 16 th century in his well known work,Bhavaprakasanighantu, recorded as many as seven different kinds of alloys (upadhatus ) including bronze and brass (Chunekar and Pandey, 2002: 609). He has recorded two different kinds of brasses such as Rajariti and Brahmariti. Besides, two other types of brasses ( pittala ) i.e., ritika and kaktundi have also been recorded (Neogi, 1979: 41).

Besides these, Allan (1979: 43-45) cites the work of Abu Dulaf, Al-risalat al-thqniya,datable to 9 th -10 th centuries AD, who described production of a variety of tutiyain Iran. He recorded that the Indian tutiya was preferred in Persia (Allan, 1979: 43-45), which obviously might have been better than the Persian one. It is likely that the Persians imported Indian tutiya. The Persians also recorded Indian tutiya as the vapour of tin (Allan, 1979: 44), which might be zinc (Craddock et al. 1989: 74) from Zawar. Thus the Persian literary source also supports production of zinc in India in 9 th -10 th centuries AD. And brass has surely longer history than zinc.

All the aforesaid literary references clearly suggest that metallic zinc was known in India several centuries before the actual dated evidence of commercial production at Zawar.

Thus the aforesaid archaeological and literary evidence indicates that Indians had started using zinc rich ores from second millennium BC, though we can not claim that it was intentional. Of course stray discoveries of brasses have been made from Bronze and Early Iron Age sites, but we can not conclude that it was a common metal. The discovery of coins and other objects indicates that it became popular only in the second half of the first millennium BC.

Zinc in Europe

William Champion established a zinc-smelting furnace in 1738 AD at Bristol in England and started commercial production in 1743. His furnace was quite similar to the Zawar example with downward distillation (Day, 1973:75-76). What is interesting is that Champion used exactly the same technique of distillation per descensum that was used at Zawar and even used 1.5% (weight) common salt in the zinc smelting charge (Biswas, 1993: 327). Thus his arrangement of retorts and technique was identical to Zawar. Dr. Lane is believed to have smelted zinc ore at his copper work in Swansea in 1720 (Porter, 1991: 60) around 20 years before Champion started zinc production in England. Was it Lane who came to Zawar and learnt zinc smelting technique and attempted it at Swansea, from where Champion, Henkel and 'others copied the Indian process!

Craddock gives credit to the Portuguese ships for transporting zinc from India to China and eventually introduction of zinc technology. He emphatically states that the Zawar process is the ancestor of all known zinc smelting techniques in the world.

Conclusion

Though, early evidence of metallic zinc is known from Athenian Agora and Taxila (datable 4 th to 2 nd centuries BC), there is no evidence of regular production of metallic zinc at these sites. However, recent discovery of brasses from Senuwar has now strongly indicated that metallic zinc was surely being produced during the Early Historic phase in India. It can be suggested that zinc was no more a rare metal. To date the oldest evidence of pure zinc comes from Zawar as early as 9 thcentury AD, when distilration process was employed to make pure zinc. The Bhils of Southern Rajasthan are held to be the aborigines of this region (Hooja 1994) and prepare alcohol by traditional down-word distillation method. Interestingly zinc was also produced Zawar by using same principle of distillation. Moreover, Brooke (1850) has recorded that until 1840 the Bhils of Zawar knew distillation process of pure zinc. Therefore the credit of innovating special retorts and furnaces for distillation of zinc surely goes to the Bhil tribe of Southern Rajasthan. It was surely this local knowledge which they could successfully employ for distillation of zinc. Thus the Zawar metallurgists brought about a break through in non-ferrous metal extraction around 12 th century, if not earlier, by producing it on commercial scale. On the other hand in China commercial production of zinc started almost three hundred years later than India. It appears that brass was introduced in China in the early centuries of the Christian Era through Buddhism, though the idea of zinc distillation process may have traveled in 16 th century via international trade to China. From China it was exported to Europe in the middle of the 17 th century AD under the name totamu or tutenag, which was derived from Tutthanaga - a name of zinc in South Indian languages (Bonnin, 1924; Deshpande, 1996). However, Indian zinc had already reached Europe prior to this and had created great curiosity about this metal. Thus the commercial production of zinc at Zawar had begun almost three hundred years earlier than China, if not earlier. Therefore, Zawar has globally stolen the march by becoming the oldest commercial center of zinc in the world. William Champion's furnace in the 18 th century at Bristol was based on Indian downward distillation process, the idea of which may have reached there through the Portuguese or East India Company or by some European traveler. Hence Zawar, in the words of Craddock, is the· ancestor of all zinc production techniques of the world. It was an industrial activity, which laid the basis of various modern chemical and extractive industries.

Acknowledgements

We would like to record our sincere thanks to Prof. D. P. Agrawal and Rajiv Malhotra for constant encouragement to work on archaeometallurgy in Rajasthan. We are grateful to Profs. P. T. Craddock, V. H. Sonawane, K. K. Bhan, Toshiki Osada, G. L Possehl, V. S. Shinde, K. S. Gupta, S. Balasubramaniam, Michael Witzel, Meena Gaur and Drs Piyush Bhatt, S. Aruni, Shahida Ansari, P. Dobal, J. Meena, R. Barhat, B. M. Jawalia, S. K. Sharma, Vishnu Mali, H. Chaudhary and Mr. P. Goyal, L. C. Patel and Miss Noriko Hase for helping us at various stages while collecting data for this paper.

References

Agrawal, D. P. and J. S. Kharakwal 2003. Bronze and Iron Ages in South Asia, Delhi: Aryan Books International.

Allan. J. W. 1979, Persian Metal Technology 700-1300 AD. London: Ithaca Press.

Anon. 1872. The Mines of Mewar, The Journal of Indian Antiquary (see under Miscellany section) (Ed. J. A. S. Burgess) 1: 63-4.

Athavale, V. T. 1967. Chemical Analysis and Metallographic Examination of Metal Objects, in B. K. Thapar ed. Prakash 1955: A Chalcolithic site in the Tapti Valley,Ancient India 20-21: 135-39 (see table IV)

Beal, S. 2000 (1884). Buddhist Records o!the Western World vol 2. Trans, From the Chinese of Hiuen Tsiang, Trubner, London.

Bhati, H. S. 1995 (Ed.). Maharana Rajsingh Patta Bahi Pattedaran ri Vigat (in Hindi), Himanshu Publication, Udaipur.

Bhatnagar, S. N. & L. K. Gurjar 1989. Zinc - A Heritage, Hind Zinc Tech, Jan. 1989 Vol. 1.

Biswas, Arun Kumar 1993. The primacy of India in ancient brass and zinc metallurgy, Indian Journal of History of Science 28(4): 309-330.

Biswas, Arun Kumar 1994. Minerals and Metals in Ancient India Vol. 1 Archaeological Evidence, D. K. Printworld (P) Ltd., New Delhi.

Biswas, A. K. and S. Biswas 1996. Minerals and Metals in Ancient India vol II, D.K. Printworld, Delhi.

Blochmann, H. (trans and ed.) 1989. The A-in-IAkbari of Abul Fazl Allami, Low Price Pub, New Delhi (originally pub in 1927).

Bonnin, A. 1924. Tutenag and Paktong, Oxford University Press, Milford.

Bowman, S. G. E, M. R. Cowell and J. Cribb 1989. Two thousand years of coinage in China: an analytical survey, Journal of Historical Metallurgy Society 23 (1):25-30.

Brooke, J. C. 1850. Notes on the zinc mines of Jawar, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal XIX (1-7): 212-215.

Caldwell. K. S. 1920. The result of analyses of certain ornaments found in Asura sites, Journal of Bihar and Orissa Research Society 6: 390-423.

Carsus, H. D. 1960. Historical background, In C. H. Mathewson (Ed.). Zinc, New York: American Chemical Society. Pp 1-8.

Chakrabarti, D. K. & Nayanjyot Lahiri. 1996. Copper and Its Alloys in Ancient India,Munshiram Manoharlal, Delhi.

Chatterjee, C. D. 1957. Gold and Brass coins of the Imperial Guptas, Journal of the UP Historical Society (New Series) 5 (2): 100-116.

Craddock, P. T. 1981. The Copper alloys of Tibet and their background, In Eds. W. A. Oddy and W. Zwalf. Aspect of Tibetan Metallurgy, British Museum Occasional Paper no 15, London Pp. 1-31, 125-137.

Craddock, P. T. 1995. Early Mining and Metal Production, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

Craddock, P. T., I. C. Freestone, L. K. Gurjar A. Middleton & L. Willies 1989. The Production of Lead, Silver and Zinc in Early India, In A. Hauptmann, E. Pernicka and G. Wagner (Eds.) Old World Archaeometallurgy, Selbstverlag des Deutschen Bergbau-Museums, Bochum Pp. 51-69.

Crookshank, H. 1947. Zawar silver-lead-zinc mines, Indian Minerals 1 :22-27.

Datt, Ram (commentary) 1900. Charak Samhita, Pt. Ram Datt Narayan Chaube Anath Chikitsalaya aur Pustakalaya Manik Chauk, Mathura.

Day, Joan 1973. Bristol Brass A History of the Industry, David and Charles: Newton Abbot, England.

Deo, S. B. 1973. Mahurjhari Excavation 1970-72, Nagpur University, Nagpur.

Deshpande, Vijay 1996. A note on Ancient zinc smelting on India and China, Indian Journal of History of Science 31 (3): 275-279

Erskine, K. D. 1908. Rajputana Gazetteers Vol II The Mewar Residency, Ajmer. pp.53

Freestone, I. C., P. T. Craddock, K. T. M. Hegde, M. J. Hughes and H. V. Paliwal. 1985. Zinc production at Zawar, Rajasthan. In P. T. Craddock and M. J. Hughes (Eds.). Furnaces and Smelting Technology in Antiquity, British Museum, London. Pp. 229-41.

Gairola, T. R. 1956. Bidri Ware, Ancient India 12: 16-18.

Gangopadhyay, A., T. R. Ramchandran and A. K. Biswas 1984. Phase studies on zinc residues of Ancient Indian origin, Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals 37 (3): 234-241.

Gaur, R. C. 1983. Excavations at Atranjikhera: Early Civilizations of the Upper Ganga Basin, Aligarh Muslim University/Motilal Banarasidas, New Delhi.

Gurjar, L. K., P. T. Craddock, L. Willies and H. V. Paliwal. 2001. Zinc in In K. V. Mittal (Ed.) History of Technology in India vol III, Indian National Science Academy, Delhi. Pp. 621-38.

Habib, Irfan 2000. Joseph Needham and the history of Indian technology, Indian Journal of History of Science 35 (2): 245-274.

Halder, R. R. 1929-30. Samoli Inscription of the time of Siladitya (Vikram Sllmvat 703), Epigraphia Indica 20: 97-99.

Hary Falk 1991. Silver, Lead and Zinc in Early Indian Literature, South Asian Studies7: 111-120.

Hegde, K. T. M. 1989. Zinc and Brass Production in Ancient India, Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 14(1): 86-96.

Hett, W. S. 1993 (Trans.). Aristotle on Marvellous Things Heard, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Hooja, R. 1994. Contacts, conflicts and coexistence: Bhils and non-Bhils in Southeastern Rajasthan, In B. Allchin (Ed.) Living Traditions, Oxford & IBH Pub., New Delhi, pp 125-140.

Hooja, R. and Vijay Kumar 1995. Aspects of the Early Copper Age in Rajasthan. In Raymond and Bridget Allchin (Eds.) South Asian Archaeology (pub. in 1997). Oxford and IBH, New Delhi. Pp. 323-339.

Jones, H. L. 1954 (translation). The Geography of Strabo (books XV and XVI) vol. VII, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Joshi, A. P. 1973. Analysis of copper and iron objects. In S. B. Deo Ed. Mahurjhari Excavation 1970-72, Nagpur University, Napur:. Pp 77.

Kachhawaha, O. P. 1992. History of Famines in Rajasthan (1900-1990 AD), Research Publishers, Jodhpur.

Kangle, R. P. 1960. The Kautilya Arthasastra vol I, Motilal Banarasidas, Delhi.

Kangle, R. P. 1972. The Kautilya Arthasastra vol II , Motilal Banarasidas, Delhi.

Kharakwal, J. S. 2005. Indus Civilization: an overview, In Toshiki Osada (Ed.)Occasional Paper 1 Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto, Japan, Pp 41-86.

La Niece, S. and G. Martin 1987. The technical examination of Bidri Ware, Studies in Conservation 32: 97-101.

Lal, B. B., J. P. Joshi, B. K. Thapar and Madhubala 2003. Excavations at Kalibangan the Early Harappans, Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi.

Leoshko, Janice and Chandra L. Reedy 1994. Interdisciplinary Research on the Provenance of Eastern Indian Bronzes: Preliminary Findings, South Asian Studies10: 25-35.

Malu, Kamala 1987. The History of Famines in Rajputana (1858-1900 AD), Himanshu Publication, Udaipur.

Marshall, Sir John 1951. Taxila An Illustrate Account of Archaeological Excavations (Vol. II. Minor Antiquities), University Press, Cambridge. pp 564- 571 .

Misra, V. N., V. S. Shinde, R. K. Mohanty, Lalit Pandey and Jeewan S. Kharakwal. 1997. Excavations at Balathal, District Udaipur, Rajasthan (1995-97), with special reference to Chalcolithic architecture, Man and Environment 22(2): 35-59.

Morgan, S. W. K. 1976. Zinc. Ellis Horwood, Chichester.

Nautiyal, V., D. P. Agrawal and R. V. Krishnamurthy 1981. Some new analysis on the protohistorical copper artifacts, Man and Environment 5: 48-51.

Neogi, P. 1979. Copper in Ancient India , Jananki Prakashan, Patna.

Ojha, G. S. H 1996-97. Udaipur Rajya ka Itihas, Rajasthani Granthagar vol. I (first published 1928 VS 1985) from Government Press Ajmer, Jodhpur, Rajasthan.

Pal, P. 1988 (Ed.). A Pot-Pourri of Indian Art, Marg Publications, Bombay.

Paliwal, H. V., L. K. Gurjar, and P. T. Craddock 1986. Zinc and brass in ancient India. Bulletin of Canadian Institute of Metals 885: 75-79.

Porter, Frank 1991. Zinc Hand Book Properties, Processing, and Use in Design, Marcel Dekker, Inc New York.